User login

VAIL, COLO. – Fever in a traveler back from the tropics is malaria until proven otherwise – and it’s a medical emergency, Dr. Jay S. Keystone said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.

"Death from malaria can occur in 3-4 days. Not always, but it can. That’s all it takes," said Dr. Keystone, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto and a past president of the International Society of Travel Medicine.

If it’s malaria due to Plasmodium falciparum in a nonimmune patient – and children should be assumed to be nonimmune – hospital admission for up to 48 hours is warranted, even if only minimal parasitemia is present. There’s no need to keep the patient in the hospital until the parasitemia is zero; once the parasitemia is falling in response to therapy, monitoring can safely be accomplished on an outpatient basis with daily blood films until the patient has fully recovered.

Why admit a patient with mere low-level P. falciparum parasitemia? Dr. Keystone has seen returned travelers with a several-day history of fever go from 1% to 30% parasitemia in the course of just 9 hours.

"You really don’t know the parasitemia mass when you’re looking at the blood film because most of the falciparum develops in the microcirculation," he explained.

The one exception to his maximum 48-hour hospitalization rule is in patients with a heavy P. falciparum infection as defined by 5% or greater parasitemia. Onset of adult respiratory distress syndrome in such patients often occurs on day 3-4 of treatment, just as they’re starting to look markedly better and their parasitemia is coming down.

The clinical hallmark of malaria is fever. "That’s the only thing you have to know about what malaria looks like. And if there’s no periodicity to the fever, ignore that; malaria is still in the differential diagnosis," Dr. Keystone said. "For falciparum, the fever you’re most worried about, there really is only rarely periodicity, especially in children. If, however, there is an exact periodicity – fever every other day, every third day, et cetera – it can only be malaria."

In a study Dr. Keystone coauthored that provided the first systematic evaluation of illness in returned pediatric travelers, febrile illness was the presenting complaint in 23% of 1,591 ill children seen at 51 tropical medicine clinics in the GeoSentinel Global Surveillance Network maintained by the International Society of Travel Medicine and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In fact, fever was the third most common presenting complaint, after diarrhea in 28% of patients and dermatologic conditions in 25%.

Of 358 ill returned pediatric travelers with fever, malaria was the No. 1 cause, accounting for 35% of cases, followed by upper respiratory tract infections and other viral illnesses in 28% (Pediatrics 2010;125: 1072-80).

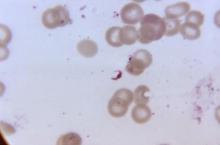

The diagnosis of malaria is made based upon thick blood films; speciation is based upon thin films. If the first blood film is negative, testing should be repeated daily for 2 additional days; otherwise, it’s quite possible to miss parasitemia.

As an alternative to the time-honored thick blood films, Dr. Keystone strongly recommended the use of rapid diagnostic tests, in which malaria is diagnosed based upon detection of malaria antigen in the blood. These tests have been shown to have 99% sensitivity and 94% specificity for P. falciparum infection, and 94% sensitivity and 100% specificity for Plasmodium vivax.

"In Ontario, that’s all we do – we do the rapid diagnostic test, then thin blood films looking for the species and the parasitemia. Rapid diagnostic tests are especially good if your lab doesn’t have a lot of experience with malaria, as you’d expect in a place such as Colorado," he noted.

Parasitemia of 1% or greater is due to P. falciparum more than 90% of the time. In parasitemia, 5% is a critical number; at that level, parenteral therapy is warranted and there is a risk of death.

"At 10% or more, it’s time to change your underwear," Dr. Keystone quipped. "You’ve got a serious problem. At that point, you’re always thinking about exchange transfusion."

Recognizing and Treating Malaria in the United States

Who brings malaria back to the United States from abroad? A recent CDC analysis of cases imported during 2009 concluded that U.S. immigrants who had been visiting friends and relatives abroad accounted for 63% of cases. Missionaries made up another 10%, with the remainder being divided between tourists, business travelers, and students (MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2011 Apr;60:1-15).

A review of 13 North American and European clinical studies highlighted differences between children and adults in the presenting signs and symptoms of malaria. The majority of children had fever in excess of 40°C, compared with just a quarter of adults. The same was true of hepatosplenomegaly and anemia. Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea were very common in children, whereas the most common nonspecific symptoms in adults were headache and myalgia. Thrombocytopenia was extremely common in both groups (Lancet Infect. Dis. 2007;7:349-57).

Every medical student has to learn the four human malaria parasites: P. falciparum, vivax, malariae, and ovale. Recently a fifth has been identified: Plasmodium knowlesi. And it’s a pip.

"It’s a monkey malaria that’s now in the human population. Knowlesi is found mainly in Southeast Asia, especially in the border areas of Thailand. It is one of the fatal malarias. It looks benign and like [Plasmodium] malariae under the microscope, but it kills like P. falciparum. So if you see someone from Southeast Asia who’s very sick and it looks like malariae, think about knowlesi," Dr. Keystone urged.

Two very good medications are available in the United States for treatment of malaria. For patients with heavy parasitemia or severe malaria as defined by cerebral, respiratory, or renal manifestations or severe anemia, intravenous artemether/lumefantrine (Coartem) is the treatment of choice because it’s faster acting, with an average parasite clearance time of 2 days, compared to 4 days with atovaquone/proguanil (Malarone). However, atovaquone/proguanil is better tolerated and thus a good choice in patients with less than 5% parasitemia who don’t have severe disease, he said.

For more information on travel medicine, Dr. Keystone recommends the following resources:

• Text: "Control of Communicable Diseases Manual," 19th Edition, edited by Dr. David L. Heymann. An official report of the American Public Health Association. Available in paperback at Amazon.com for about $23.

"It’s a brilliant book," Dr. Keystone said. "The beauty of this book is it doesn’t just give you the epidemiology and incubation, it gives you the period of communicability, and it’s all laid out in easy form. I would highly advise you that if you don’t have one of these in the office, it’s definitely worth having."

• Web: Every infectious diseases program should have a subscription to Gideon, Dr. Keystone said. Plug in the pertinent facts regarding a case and Gideon spits out the complete differential diagnosis, with the possibilities rank-ordered and accompanying treatment recommendations. Physicians can obtain a free 15-day trial through the website.

"Gideon is probably the best geographic, computer-based, online program for infectious diseases that I know of. You don’t have to be smart to know everything about tropical medicine. If you’re looking for something to help you diagnose tropical diseases, this would be the one," he said.

• Phone: 770-488-7788 connects you to the CDC’s malaria branch.

Dr. Keystone disclosed that he is a consultant to Gideon.

VAIL, COLO. – Fever in a traveler back from the tropics is malaria until proven otherwise – and it’s a medical emergency, Dr. Jay S. Keystone said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.

"Death from malaria can occur in 3-4 days. Not always, but it can. That’s all it takes," said Dr. Keystone, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto and a past president of the International Society of Travel Medicine.

If it’s malaria due to Plasmodium falciparum in a nonimmune patient – and children should be assumed to be nonimmune – hospital admission for up to 48 hours is warranted, even if only minimal parasitemia is present. There’s no need to keep the patient in the hospital until the parasitemia is zero; once the parasitemia is falling in response to therapy, monitoring can safely be accomplished on an outpatient basis with daily blood films until the patient has fully recovered.

Why admit a patient with mere low-level P. falciparum parasitemia? Dr. Keystone has seen returned travelers with a several-day history of fever go from 1% to 30% parasitemia in the course of just 9 hours.

"You really don’t know the parasitemia mass when you’re looking at the blood film because most of the falciparum develops in the microcirculation," he explained.

The one exception to his maximum 48-hour hospitalization rule is in patients with a heavy P. falciparum infection as defined by 5% or greater parasitemia. Onset of adult respiratory distress syndrome in such patients often occurs on day 3-4 of treatment, just as they’re starting to look markedly better and their parasitemia is coming down.

The clinical hallmark of malaria is fever. "That’s the only thing you have to know about what malaria looks like. And if there’s no periodicity to the fever, ignore that; malaria is still in the differential diagnosis," Dr. Keystone said. "For falciparum, the fever you’re most worried about, there really is only rarely periodicity, especially in children. If, however, there is an exact periodicity – fever every other day, every third day, et cetera – it can only be malaria."

In a study Dr. Keystone coauthored that provided the first systematic evaluation of illness in returned pediatric travelers, febrile illness was the presenting complaint in 23% of 1,591 ill children seen at 51 tropical medicine clinics in the GeoSentinel Global Surveillance Network maintained by the International Society of Travel Medicine and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In fact, fever was the third most common presenting complaint, after diarrhea in 28% of patients and dermatologic conditions in 25%.

Of 358 ill returned pediatric travelers with fever, malaria was the No. 1 cause, accounting for 35% of cases, followed by upper respiratory tract infections and other viral illnesses in 28% (Pediatrics 2010;125: 1072-80).

The diagnosis of malaria is made based upon thick blood films; speciation is based upon thin films. If the first blood film is negative, testing should be repeated daily for 2 additional days; otherwise, it’s quite possible to miss parasitemia.

As an alternative to the time-honored thick blood films, Dr. Keystone strongly recommended the use of rapid diagnostic tests, in which malaria is diagnosed based upon detection of malaria antigen in the blood. These tests have been shown to have 99% sensitivity and 94% specificity for P. falciparum infection, and 94% sensitivity and 100% specificity for Plasmodium vivax.

"In Ontario, that’s all we do – we do the rapid diagnostic test, then thin blood films looking for the species and the parasitemia. Rapid diagnostic tests are especially good if your lab doesn’t have a lot of experience with malaria, as you’d expect in a place such as Colorado," he noted.

Parasitemia of 1% or greater is due to P. falciparum more than 90% of the time. In parasitemia, 5% is a critical number; at that level, parenteral therapy is warranted and there is a risk of death.

"At 10% or more, it’s time to change your underwear," Dr. Keystone quipped. "You’ve got a serious problem. At that point, you’re always thinking about exchange transfusion."

Recognizing and Treating Malaria in the United States

Who brings malaria back to the United States from abroad? A recent CDC analysis of cases imported during 2009 concluded that U.S. immigrants who had been visiting friends and relatives abroad accounted for 63% of cases. Missionaries made up another 10%, with the remainder being divided between tourists, business travelers, and students (MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2011 Apr;60:1-15).

A review of 13 North American and European clinical studies highlighted differences between children and adults in the presenting signs and symptoms of malaria. The majority of children had fever in excess of 40°C, compared with just a quarter of adults. The same was true of hepatosplenomegaly and anemia. Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea were very common in children, whereas the most common nonspecific symptoms in adults were headache and myalgia. Thrombocytopenia was extremely common in both groups (Lancet Infect. Dis. 2007;7:349-57).

Every medical student has to learn the four human malaria parasites: P. falciparum, vivax, malariae, and ovale. Recently a fifth has been identified: Plasmodium knowlesi. And it’s a pip.

"It’s a monkey malaria that’s now in the human population. Knowlesi is found mainly in Southeast Asia, especially in the border areas of Thailand. It is one of the fatal malarias. It looks benign and like [Plasmodium] malariae under the microscope, but it kills like P. falciparum. So if you see someone from Southeast Asia who’s very sick and it looks like malariae, think about knowlesi," Dr. Keystone urged.

Two very good medications are available in the United States for treatment of malaria. For patients with heavy parasitemia or severe malaria as defined by cerebral, respiratory, or renal manifestations or severe anemia, intravenous artemether/lumefantrine (Coartem) is the treatment of choice because it’s faster acting, with an average parasite clearance time of 2 days, compared to 4 days with atovaquone/proguanil (Malarone). However, atovaquone/proguanil is better tolerated and thus a good choice in patients with less than 5% parasitemia who don’t have severe disease, he said.

For more information on travel medicine, Dr. Keystone recommends the following resources:

• Text: "Control of Communicable Diseases Manual," 19th Edition, edited by Dr. David L. Heymann. An official report of the American Public Health Association. Available in paperback at Amazon.com for about $23.

"It’s a brilliant book," Dr. Keystone said. "The beauty of this book is it doesn’t just give you the epidemiology and incubation, it gives you the period of communicability, and it’s all laid out in easy form. I would highly advise you that if you don’t have one of these in the office, it’s definitely worth having."

• Web: Every infectious diseases program should have a subscription to Gideon, Dr. Keystone said. Plug in the pertinent facts regarding a case and Gideon spits out the complete differential diagnosis, with the possibilities rank-ordered and accompanying treatment recommendations. Physicians can obtain a free 15-day trial through the website.

"Gideon is probably the best geographic, computer-based, online program for infectious diseases that I know of. You don’t have to be smart to know everything about tropical medicine. If you’re looking for something to help you diagnose tropical diseases, this would be the one," he said.

• Phone: 770-488-7788 connects you to the CDC’s malaria branch.

Dr. Keystone disclosed that he is a consultant to Gideon.

VAIL, COLO. – Fever in a traveler back from the tropics is malaria until proven otherwise – and it’s a medical emergency, Dr. Jay S. Keystone said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.

"Death from malaria can occur in 3-4 days. Not always, but it can. That’s all it takes," said Dr. Keystone, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto and a past president of the International Society of Travel Medicine.

If it’s malaria due to Plasmodium falciparum in a nonimmune patient – and children should be assumed to be nonimmune – hospital admission for up to 48 hours is warranted, even if only minimal parasitemia is present. There’s no need to keep the patient in the hospital until the parasitemia is zero; once the parasitemia is falling in response to therapy, monitoring can safely be accomplished on an outpatient basis with daily blood films until the patient has fully recovered.

Why admit a patient with mere low-level P. falciparum parasitemia? Dr. Keystone has seen returned travelers with a several-day history of fever go from 1% to 30% parasitemia in the course of just 9 hours.

"You really don’t know the parasitemia mass when you’re looking at the blood film because most of the falciparum develops in the microcirculation," he explained.

The one exception to his maximum 48-hour hospitalization rule is in patients with a heavy P. falciparum infection as defined by 5% or greater parasitemia. Onset of adult respiratory distress syndrome in such patients often occurs on day 3-4 of treatment, just as they’re starting to look markedly better and their parasitemia is coming down.

The clinical hallmark of malaria is fever. "That’s the only thing you have to know about what malaria looks like. And if there’s no periodicity to the fever, ignore that; malaria is still in the differential diagnosis," Dr. Keystone said. "For falciparum, the fever you’re most worried about, there really is only rarely periodicity, especially in children. If, however, there is an exact periodicity – fever every other day, every third day, et cetera – it can only be malaria."

In a study Dr. Keystone coauthored that provided the first systematic evaluation of illness in returned pediatric travelers, febrile illness was the presenting complaint in 23% of 1,591 ill children seen at 51 tropical medicine clinics in the GeoSentinel Global Surveillance Network maintained by the International Society of Travel Medicine and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In fact, fever was the third most common presenting complaint, after diarrhea in 28% of patients and dermatologic conditions in 25%.

Of 358 ill returned pediatric travelers with fever, malaria was the No. 1 cause, accounting for 35% of cases, followed by upper respiratory tract infections and other viral illnesses in 28% (Pediatrics 2010;125: 1072-80).

The diagnosis of malaria is made based upon thick blood films; speciation is based upon thin films. If the first blood film is negative, testing should be repeated daily for 2 additional days; otherwise, it’s quite possible to miss parasitemia.

As an alternative to the time-honored thick blood films, Dr. Keystone strongly recommended the use of rapid diagnostic tests, in which malaria is diagnosed based upon detection of malaria antigen in the blood. These tests have been shown to have 99% sensitivity and 94% specificity for P. falciparum infection, and 94% sensitivity and 100% specificity for Plasmodium vivax.

"In Ontario, that’s all we do – we do the rapid diagnostic test, then thin blood films looking for the species and the parasitemia. Rapid diagnostic tests are especially good if your lab doesn’t have a lot of experience with malaria, as you’d expect in a place such as Colorado," he noted.

Parasitemia of 1% or greater is due to P. falciparum more than 90% of the time. In parasitemia, 5% is a critical number; at that level, parenteral therapy is warranted and there is a risk of death.

"At 10% or more, it’s time to change your underwear," Dr. Keystone quipped. "You’ve got a serious problem. At that point, you’re always thinking about exchange transfusion."

Recognizing and Treating Malaria in the United States

Who brings malaria back to the United States from abroad? A recent CDC analysis of cases imported during 2009 concluded that U.S. immigrants who had been visiting friends and relatives abroad accounted for 63% of cases. Missionaries made up another 10%, with the remainder being divided between tourists, business travelers, and students (MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2011 Apr;60:1-15).

A review of 13 North American and European clinical studies highlighted differences between children and adults in the presenting signs and symptoms of malaria. The majority of children had fever in excess of 40°C, compared with just a quarter of adults. The same was true of hepatosplenomegaly and anemia. Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea were very common in children, whereas the most common nonspecific symptoms in adults were headache and myalgia. Thrombocytopenia was extremely common in both groups (Lancet Infect. Dis. 2007;7:349-57).

Every medical student has to learn the four human malaria parasites: P. falciparum, vivax, malariae, and ovale. Recently a fifth has been identified: Plasmodium knowlesi. And it’s a pip.

"It’s a monkey malaria that’s now in the human population. Knowlesi is found mainly in Southeast Asia, especially in the border areas of Thailand. It is one of the fatal malarias. It looks benign and like [Plasmodium] malariae under the microscope, but it kills like P. falciparum. So if you see someone from Southeast Asia who’s very sick and it looks like malariae, think about knowlesi," Dr. Keystone urged.

Two very good medications are available in the United States for treatment of malaria. For patients with heavy parasitemia or severe malaria as defined by cerebral, respiratory, or renal manifestations or severe anemia, intravenous artemether/lumefantrine (Coartem) is the treatment of choice because it’s faster acting, with an average parasite clearance time of 2 days, compared to 4 days with atovaquone/proguanil (Malarone). However, atovaquone/proguanil is better tolerated and thus a good choice in patients with less than 5% parasitemia who don’t have severe disease, he said.

For more information on travel medicine, Dr. Keystone recommends the following resources:

• Text: "Control of Communicable Diseases Manual," 19th Edition, edited by Dr. David L. Heymann. An official report of the American Public Health Association. Available in paperback at Amazon.com for about $23.

"It’s a brilliant book," Dr. Keystone said. "The beauty of this book is it doesn’t just give you the epidemiology and incubation, it gives you the period of communicability, and it’s all laid out in easy form. I would highly advise you that if you don’t have one of these in the office, it’s definitely worth having."

• Web: Every infectious diseases program should have a subscription to Gideon, Dr. Keystone said. Plug in the pertinent facts regarding a case and Gideon spits out the complete differential diagnosis, with the possibilities rank-ordered and accompanying treatment recommendations. Physicians can obtain a free 15-day trial through the website.

"Gideon is probably the best geographic, computer-based, online program for infectious diseases that I know of. You don’t have to be smart to know everything about tropical medicine. If you’re looking for something to help you diagnose tropical diseases, this would be the one," he said.

• Phone: 770-488-7788 connects you to the CDC’s malaria branch.

Dr. Keystone disclosed that he is a consultant to Gideon.

EXPERT OPINION FROM A CONFERENCE ON PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES