User login

Childhood Bacterial Meningitis Brings Hefty Late Sequelae

VAIL, COLO. – Half of all childhood bacterial meningitis survivors have sequelae 5 years or more afterward, according to a systematic literature review.

Intellectual and/or behavioral deficits accounted for 78% of the long-term sequelae. These are lingering aftereffects that impose academic and behavioral limitations, not the very common minor neurologic deficits that often resolve soon after discharge, Dr. Ann-Christine Nyquist noted at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.

She said she presented highlights of a literature analysis conducted by Dr. Aruna Chandran and coworkers at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, because she considers this to be the first good-quality, comprehensive data on the long-term sequelae of childhood bacterial meningitis.

Most prior studies have focused on sequelae present in the first months following a childhood episode of bacterial meningitis; the Johns Hopkins analysis was restricted to studies featuring a minimum follow-up of 5 years. It provides a far more complete picture of the disease’s underappreciated impact, noted Dr. Nyquist, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at the University of Colorado at Denver.

The analysis included 1,433 children who survived an episode of bacterial meningitis, 49% of whom had one or more long-term sequelae. Seventy-eight percent of the 1,012 recorded long-term sequelae were behavioral and/or intellectual deficits. Specifically, 45% of all long-term sequelae were categorized as low intelligence quotient/cognitive impairment, 7.6% as behavioral deficits, and 2.4% as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Gross neurologic deficits accounted for 14.3% of long-term sequelae. Another 6.7% consisted of hearing deficits (Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2011;30:3-6).

These data underscore the importance of prompt diagnosis and effective treatment of pediatric bacterial meningitis, Dr. Nyquist emphasized.

She pointed out that the most recent Cochrane review of corticosteroids for acute bacterial meningitis came down squarely on the pro side because of the significant benefit in terms of reduced sequelae. The analysis included 24 randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials in 4,041 subjects, both children and adults.

The Cochrane group found that in high-income countries, the use of adjunctive dexamethasone reduced the risk of severe hearing loss by 49%, of any hearing loss by 42%, and of short-term neurologic sequelae by 36%. Adjunctive steroids weren’t associated with significant decreases in overall mortality or long-term neurologic sequelae; however, in the subgroup with Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis, the trend for reduced mortality did achieve statistical significance (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010 Sept. 8;CD004405).

"I think within our infectious disease practice group, most of us would probably go on the side of giving dexamethasone in all cases of suspected bacterial meningitis in infants and children if we have the opportunity to make that recommendation," Dr. Nyquist said.

The dose is 0.4 mg/kg of dexamethasone given every 12 hours for a total of four doses over a period of 2 days, administered starting before or at initiation of parenteral antibiotic therapy.

A couple of caveats: Only limited data exist on the use of adjunctive corticosteroids in neonates with acute bacterial meningitis. And steroid therapy in any age group poses a challenge because its anti-inflammatory action reduces the permeability of the damaged CNS capillary membrane – the blood-brain barrier – at just the time when the physician is trying to get antibiotics into the CNS.

The inhibitory effect of steroids is greatest on large-molecular-weight or hydrophobic antibiotics. Vancomycin is the antibiotic affected most; levels are reduced by 42%-77%. Ampicillin levels are decreased by 57%, gentamicin levels are reduced by 30%, and ceftriaxone levels have been shown in various studies to be either unaffected or decreased by 45%, according to Dr. Nyquist.

She said that that she serves as a consultant to and has received speaking honoraria from Merck, Sanofi Pasteur, and Novartis.

VAIL, COLO. – Half of all childhood bacterial meningitis survivors have sequelae 5 years or more afterward, according to a systematic literature review.

Intellectual and/or behavioral deficits accounted for 78% of the long-term sequelae. These are lingering aftereffects that impose academic and behavioral limitations, not the very common minor neurologic deficits that often resolve soon after discharge, Dr. Ann-Christine Nyquist noted at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.

She said she presented highlights of a literature analysis conducted by Dr. Aruna Chandran and coworkers at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, because she considers this to be the first good-quality, comprehensive data on the long-term sequelae of childhood bacterial meningitis.

Most prior studies have focused on sequelae present in the first months following a childhood episode of bacterial meningitis; the Johns Hopkins analysis was restricted to studies featuring a minimum follow-up of 5 years. It provides a far more complete picture of the disease’s underappreciated impact, noted Dr. Nyquist, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at the University of Colorado at Denver.

The analysis included 1,433 children who survived an episode of bacterial meningitis, 49% of whom had one or more long-term sequelae. Seventy-eight percent of the 1,012 recorded long-term sequelae were behavioral and/or intellectual deficits. Specifically, 45% of all long-term sequelae were categorized as low intelligence quotient/cognitive impairment, 7.6% as behavioral deficits, and 2.4% as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Gross neurologic deficits accounted for 14.3% of long-term sequelae. Another 6.7% consisted of hearing deficits (Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2011;30:3-6).

These data underscore the importance of prompt diagnosis and effective treatment of pediatric bacterial meningitis, Dr. Nyquist emphasized.

She pointed out that the most recent Cochrane review of corticosteroids for acute bacterial meningitis came down squarely on the pro side because of the significant benefit in terms of reduced sequelae. The analysis included 24 randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials in 4,041 subjects, both children and adults.

The Cochrane group found that in high-income countries, the use of adjunctive dexamethasone reduced the risk of severe hearing loss by 49%, of any hearing loss by 42%, and of short-term neurologic sequelae by 36%. Adjunctive steroids weren’t associated with significant decreases in overall mortality or long-term neurologic sequelae; however, in the subgroup with Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis, the trend for reduced mortality did achieve statistical significance (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010 Sept. 8;CD004405).

"I think within our infectious disease practice group, most of us would probably go on the side of giving dexamethasone in all cases of suspected bacterial meningitis in infants and children if we have the opportunity to make that recommendation," Dr. Nyquist said.

The dose is 0.4 mg/kg of dexamethasone given every 12 hours for a total of four doses over a period of 2 days, administered starting before or at initiation of parenteral antibiotic therapy.

A couple of caveats: Only limited data exist on the use of adjunctive corticosteroids in neonates with acute bacterial meningitis. And steroid therapy in any age group poses a challenge because its anti-inflammatory action reduces the permeability of the damaged CNS capillary membrane – the blood-brain barrier – at just the time when the physician is trying to get antibiotics into the CNS.

The inhibitory effect of steroids is greatest on large-molecular-weight or hydrophobic antibiotics. Vancomycin is the antibiotic affected most; levels are reduced by 42%-77%. Ampicillin levels are decreased by 57%, gentamicin levels are reduced by 30%, and ceftriaxone levels have been shown in various studies to be either unaffected or decreased by 45%, according to Dr. Nyquist.

She said that that she serves as a consultant to and has received speaking honoraria from Merck, Sanofi Pasteur, and Novartis.

VAIL, COLO. – Half of all childhood bacterial meningitis survivors have sequelae 5 years or more afterward, according to a systematic literature review.

Intellectual and/or behavioral deficits accounted for 78% of the long-term sequelae. These are lingering aftereffects that impose academic and behavioral limitations, not the very common minor neurologic deficits that often resolve soon after discharge, Dr. Ann-Christine Nyquist noted at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.

She said she presented highlights of a literature analysis conducted by Dr. Aruna Chandran and coworkers at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, because she considers this to be the first good-quality, comprehensive data on the long-term sequelae of childhood bacterial meningitis.

Most prior studies have focused on sequelae present in the first months following a childhood episode of bacterial meningitis; the Johns Hopkins analysis was restricted to studies featuring a minimum follow-up of 5 years. It provides a far more complete picture of the disease’s underappreciated impact, noted Dr. Nyquist, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at the University of Colorado at Denver.

The analysis included 1,433 children who survived an episode of bacterial meningitis, 49% of whom had one or more long-term sequelae. Seventy-eight percent of the 1,012 recorded long-term sequelae were behavioral and/or intellectual deficits. Specifically, 45% of all long-term sequelae were categorized as low intelligence quotient/cognitive impairment, 7.6% as behavioral deficits, and 2.4% as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Gross neurologic deficits accounted for 14.3% of long-term sequelae. Another 6.7% consisted of hearing deficits (Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2011;30:3-6).

These data underscore the importance of prompt diagnosis and effective treatment of pediatric bacterial meningitis, Dr. Nyquist emphasized.

She pointed out that the most recent Cochrane review of corticosteroids for acute bacterial meningitis came down squarely on the pro side because of the significant benefit in terms of reduced sequelae. The analysis included 24 randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials in 4,041 subjects, both children and adults.

The Cochrane group found that in high-income countries, the use of adjunctive dexamethasone reduced the risk of severe hearing loss by 49%, of any hearing loss by 42%, and of short-term neurologic sequelae by 36%. Adjunctive steroids weren’t associated with significant decreases in overall mortality or long-term neurologic sequelae; however, in the subgroup with Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis, the trend for reduced mortality did achieve statistical significance (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010 Sept. 8;CD004405).

"I think within our infectious disease practice group, most of us would probably go on the side of giving dexamethasone in all cases of suspected bacterial meningitis in infants and children if we have the opportunity to make that recommendation," Dr. Nyquist said.

The dose is 0.4 mg/kg of dexamethasone given every 12 hours for a total of four doses over a period of 2 days, administered starting before or at initiation of parenteral antibiotic therapy.

A couple of caveats: Only limited data exist on the use of adjunctive corticosteroids in neonates with acute bacterial meningitis. And steroid therapy in any age group poses a challenge because its anti-inflammatory action reduces the permeability of the damaged CNS capillary membrane – the blood-brain barrier – at just the time when the physician is trying to get antibiotics into the CNS.

The inhibitory effect of steroids is greatest on large-molecular-weight or hydrophobic antibiotics. Vancomycin is the antibiotic affected most; levels are reduced by 42%-77%. Ampicillin levels are decreased by 57%, gentamicin levels are reduced by 30%, and ceftriaxone levels have been shown in various studies to be either unaffected or decreased by 45%, according to Dr. Nyquist.

She said that that she serves as a consultant to and has received speaking honoraria from Merck, Sanofi Pasteur, and Novartis.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A CONFERENCE ON PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Prolonged Fever is Typhoid’s Hallmark

VAIL, COLO. – Two-thirds of all cases of typhoid fever seen in the United States result from travel to India or neighboring Pakistan or Bangladesh.

Add in Mexico, the Philippines, and Guatemala, and travel to just those six countries accounts for 80% of all U.S. cases of typhoid fever, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study.

Some 41% of cases in the United States during 1999-2006 occurred in patients aged 17 years or younger.

"This is a very important disease in children," Dr. Jay S. Keystone noted in highlighting the CDC report at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital, Colorado, Aurora.

The infection has substantial morbidity, as 73% of patients were hospitalized, half for longer than a week. The mortality rate, however, was only 0.2%.

Dr. Keystone stressed that prolonged fever is the key distinguishing feature of typhoid. The fever lasts weeks longer than those of dengue or chikungunya, which persist for about 1 week. So once malaria has been ruled out, weeks of fever have accrued, and the clinical picture isn’t consistent with mononucleosis, cytomegalovirus, or other viral illnesses, it’s time to think about typhoid fever.

Other than prolonged fever, the classic symptoms include headache, cough, diarrhea, and abdominal pain.

Only 5% of patients in the CDC study had been vaccinated against typhoid fever prior to their foreign travel. However, it’s important to recognize that the vaccine is only about 70% effective, so immunization against typhoid – unlike the other standard travel vaccines, which are 95% or more effective – does not rule out the disease, noted Dr. Keystone, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto and a past president of the International Society of Travel Medicine.

A relatively long period of effective antibiotic therapy (average, 3-5 days) is required before patients with typhoid become afebrile. Azithromycin or ceftriaxone are good choices for empiric therapy during the 3-day wait for results of blood, stool, and urine cultures, the physician said.

Azithromycin gets the edge because only 5-7 days of therapy are required, in contrast to 14 days for ceftriaxone, he added.

In the CDC series, 13% of Salmonella ser Typhi isolates were multidrug-resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Some 38% were resistant to nalidixic acid, which is a marker for reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones. The proportion of nalidixic acid-resistant isolates tripled from 1999 to 2006 (JAMA 2009;302:859-65).

Dr. Keystone declared having no relevant financial interests.

VAIL, COLO. – Two-thirds of all cases of typhoid fever seen in the United States result from travel to India or neighboring Pakistan or Bangladesh.

Add in Mexico, the Philippines, and Guatemala, and travel to just those six countries accounts for 80% of all U.S. cases of typhoid fever, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study.

Some 41% of cases in the United States during 1999-2006 occurred in patients aged 17 years or younger.

"This is a very important disease in children," Dr. Jay S. Keystone noted in highlighting the CDC report at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital, Colorado, Aurora.

The infection has substantial morbidity, as 73% of patients were hospitalized, half for longer than a week. The mortality rate, however, was only 0.2%.

Dr. Keystone stressed that prolonged fever is the key distinguishing feature of typhoid. The fever lasts weeks longer than those of dengue or chikungunya, which persist for about 1 week. So once malaria has been ruled out, weeks of fever have accrued, and the clinical picture isn’t consistent with mononucleosis, cytomegalovirus, or other viral illnesses, it’s time to think about typhoid fever.

Other than prolonged fever, the classic symptoms include headache, cough, diarrhea, and abdominal pain.

Only 5% of patients in the CDC study had been vaccinated against typhoid fever prior to their foreign travel. However, it’s important to recognize that the vaccine is only about 70% effective, so immunization against typhoid – unlike the other standard travel vaccines, which are 95% or more effective – does not rule out the disease, noted Dr. Keystone, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto and a past president of the International Society of Travel Medicine.

A relatively long period of effective antibiotic therapy (average, 3-5 days) is required before patients with typhoid become afebrile. Azithromycin or ceftriaxone are good choices for empiric therapy during the 3-day wait for results of blood, stool, and urine cultures, the physician said.

Azithromycin gets the edge because only 5-7 days of therapy are required, in contrast to 14 days for ceftriaxone, he added.

In the CDC series, 13% of Salmonella ser Typhi isolates were multidrug-resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Some 38% were resistant to nalidixic acid, which is a marker for reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones. The proportion of nalidixic acid-resistant isolates tripled from 1999 to 2006 (JAMA 2009;302:859-65).

Dr. Keystone declared having no relevant financial interests.

VAIL, COLO. – Two-thirds of all cases of typhoid fever seen in the United States result from travel to India or neighboring Pakistan or Bangladesh.

Add in Mexico, the Philippines, and Guatemala, and travel to just those six countries accounts for 80% of all U.S. cases of typhoid fever, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study.

Some 41% of cases in the United States during 1999-2006 occurred in patients aged 17 years or younger.

"This is a very important disease in children," Dr. Jay S. Keystone noted in highlighting the CDC report at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital, Colorado, Aurora.

The infection has substantial morbidity, as 73% of patients were hospitalized, half for longer than a week. The mortality rate, however, was only 0.2%.

Dr. Keystone stressed that prolonged fever is the key distinguishing feature of typhoid. The fever lasts weeks longer than those of dengue or chikungunya, which persist for about 1 week. So once malaria has been ruled out, weeks of fever have accrued, and the clinical picture isn’t consistent with mononucleosis, cytomegalovirus, or other viral illnesses, it’s time to think about typhoid fever.

Other than prolonged fever, the classic symptoms include headache, cough, diarrhea, and abdominal pain.

Only 5% of patients in the CDC study had been vaccinated against typhoid fever prior to their foreign travel. However, it’s important to recognize that the vaccine is only about 70% effective, so immunization against typhoid – unlike the other standard travel vaccines, which are 95% or more effective – does not rule out the disease, noted Dr. Keystone, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto and a past president of the International Society of Travel Medicine.

A relatively long period of effective antibiotic therapy (average, 3-5 days) is required before patients with typhoid become afebrile. Azithromycin or ceftriaxone are good choices for empiric therapy during the 3-day wait for results of blood, stool, and urine cultures, the physician said.

Azithromycin gets the edge because only 5-7 days of therapy are required, in contrast to 14 days for ceftriaxone, he added.

In the CDC series, 13% of Salmonella ser Typhi isolates were multidrug-resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Some 38% were resistant to nalidixic acid, which is a marker for reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones. The proportion of nalidixic acid-resistant isolates tripled from 1999 to 2006 (JAMA 2009;302:859-65).

Dr. Keystone declared having no relevant financial interests.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A CONFERENCE ON PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Kocher Criteria Still Best Way to ID Septic Arthritis in Kids

VAIL, COLO. – Four simple criteria are useful in distinguishing septic arthritis from transient synovitis in a child with an inflamed hip.

The criteria are known as the Kocher criteria, for Dr. Mininder S. Kocher, associate director of sports medicine at Children’s Hospital Boston, who was first author of the study that introduced the criteria and an associated evidence-based, predictive algorithm.

The criteria are inability to tolerate weight bearing, fever greater than 38.5° C (101.3° F), an ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) in excess of 40 mm/hour, and a peripheral WBC count greater than 12,000 cells/mm3.

Dr. Kocher and his coworkers showed in a retrospective study that a child who meets none of these four criteria has just a 0.2% chance of having septic arthritis. With one criterion present, there’s a 3% chance. With two criteria, it’s 40%. With any three, the probability of septic arthritis jumps to 93%. And when all four criteria are present, the probability of septic arthritis is 99.6% (J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1999;81:1662-70).

"Looking back on our own cases, this has been really helpful," Heather R. Heizer said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.

The Kocher criteria deserve to be more widely known. Septic arthritis is an orthopedic emergency. Delayed treatment can lead to irreversible joint damage. And septic arthritis occurs more often in childhood than at any other period of life, observed Ms. Heizer, a physician assistant in the department of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver.

The most common site for septic arthritis is the hip, followed by the knee, then the ankle. Together these three sites account for 80% of all cases.

In addition to the Kocher criteria, other signs and symptoms of septic arthritis include limb pain, joint effusion, and a strong tendency for the patient to hold the affected joint in the position of maximal intracapsular volume in order to minimize discomfort. Neonates and infants may present with pseudoparalysis in response to the joint pain.

The log-roll technique is an effective way to detect hip effusion on clinical examination. With the patient lying supine on the examination table, the examiner places one hand at the ankle and another on the thigh and rolls the leg back and forth. Hip effusion can also be detected by ultrasound or MRI. However, it’s important to recognize that the presence of hip effusion doesn’t distinguish septic arthritis from transient synovitis.

Diagnosis of septic arthritis is based upon a combination of clinical findings and analysis of synovial fluid obtained via joint aspiration. Septic arthritis is suggested by an opaque, yellow-to-green synovial fluid with an elevated WBC, at least 75% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and a glucose concentration of only about 30% of that in blood.

The initial antibiotic therapy should be selected before synovial fluid culture results are available. The child’s age is an important consideration, as the causative organisms vary. Haemophilus influenzae was the most common pathogen in children younger than 5 years of age until the vaccine entered wide use. Now Staphylococcus aureus is No. 1 in all age groups, and community-acquired MRSA (methicillin-resistant S. aureus) is an important consideration.

In neonates, other organisms include group B streptococcus, Streptococcus viridans, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, gram-negative enteric bacteria including Escherichia coli and group A streptococcus.

An important and underappreciated cause of septic arthritis in non-neonates younger than age 5 years is Kingella kingae. It is typically culture-negative but can be detected by polymerase chain reaction. In addition, Neisseria meningitidis is a consideration in this age group and all the way through adolescence, as well.

Ms. Heizer declared having no financial conflicts.

VAIL, COLO. – Four simple criteria are useful in distinguishing septic arthritis from transient synovitis in a child with an inflamed hip.

The criteria are known as the Kocher criteria, for Dr. Mininder S. Kocher, associate director of sports medicine at Children’s Hospital Boston, who was first author of the study that introduced the criteria and an associated evidence-based, predictive algorithm.

The criteria are inability to tolerate weight bearing, fever greater than 38.5° C (101.3° F), an ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) in excess of 40 mm/hour, and a peripheral WBC count greater than 12,000 cells/mm3.

Dr. Kocher and his coworkers showed in a retrospective study that a child who meets none of these four criteria has just a 0.2% chance of having septic arthritis. With one criterion present, there’s a 3% chance. With two criteria, it’s 40%. With any three, the probability of septic arthritis jumps to 93%. And when all four criteria are present, the probability of septic arthritis is 99.6% (J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1999;81:1662-70).

"Looking back on our own cases, this has been really helpful," Heather R. Heizer said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.

The Kocher criteria deserve to be more widely known. Septic arthritis is an orthopedic emergency. Delayed treatment can lead to irreversible joint damage. And septic arthritis occurs more often in childhood than at any other period of life, observed Ms. Heizer, a physician assistant in the department of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver.

The most common site for septic arthritis is the hip, followed by the knee, then the ankle. Together these three sites account for 80% of all cases.

In addition to the Kocher criteria, other signs and symptoms of septic arthritis include limb pain, joint effusion, and a strong tendency for the patient to hold the affected joint in the position of maximal intracapsular volume in order to minimize discomfort. Neonates and infants may present with pseudoparalysis in response to the joint pain.

The log-roll technique is an effective way to detect hip effusion on clinical examination. With the patient lying supine on the examination table, the examiner places one hand at the ankle and another on the thigh and rolls the leg back and forth. Hip effusion can also be detected by ultrasound or MRI. However, it’s important to recognize that the presence of hip effusion doesn’t distinguish septic arthritis from transient synovitis.

Diagnosis of septic arthritis is based upon a combination of clinical findings and analysis of synovial fluid obtained via joint aspiration. Septic arthritis is suggested by an opaque, yellow-to-green synovial fluid with an elevated WBC, at least 75% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and a glucose concentration of only about 30% of that in blood.

The initial antibiotic therapy should be selected before synovial fluid culture results are available. The child’s age is an important consideration, as the causative organisms vary. Haemophilus influenzae was the most common pathogen in children younger than 5 years of age until the vaccine entered wide use. Now Staphylococcus aureus is No. 1 in all age groups, and community-acquired MRSA (methicillin-resistant S. aureus) is an important consideration.

In neonates, other organisms include group B streptococcus, Streptococcus viridans, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, gram-negative enteric bacteria including Escherichia coli and group A streptococcus.

An important and underappreciated cause of septic arthritis in non-neonates younger than age 5 years is Kingella kingae. It is typically culture-negative but can be detected by polymerase chain reaction. In addition, Neisseria meningitidis is a consideration in this age group and all the way through adolescence, as well.

Ms. Heizer declared having no financial conflicts.

VAIL, COLO. – Four simple criteria are useful in distinguishing septic arthritis from transient synovitis in a child with an inflamed hip.

The criteria are known as the Kocher criteria, for Dr. Mininder S. Kocher, associate director of sports medicine at Children’s Hospital Boston, who was first author of the study that introduced the criteria and an associated evidence-based, predictive algorithm.

The criteria are inability to tolerate weight bearing, fever greater than 38.5° C (101.3° F), an ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) in excess of 40 mm/hour, and a peripheral WBC count greater than 12,000 cells/mm3.

Dr. Kocher and his coworkers showed in a retrospective study that a child who meets none of these four criteria has just a 0.2% chance of having septic arthritis. With one criterion present, there’s a 3% chance. With two criteria, it’s 40%. With any three, the probability of septic arthritis jumps to 93%. And when all four criteria are present, the probability of septic arthritis is 99.6% (J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1999;81:1662-70).

"Looking back on our own cases, this has been really helpful," Heather R. Heizer said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.

The Kocher criteria deserve to be more widely known. Septic arthritis is an orthopedic emergency. Delayed treatment can lead to irreversible joint damage. And septic arthritis occurs more often in childhood than at any other period of life, observed Ms. Heizer, a physician assistant in the department of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver.

The most common site for septic arthritis is the hip, followed by the knee, then the ankle. Together these three sites account for 80% of all cases.

In addition to the Kocher criteria, other signs and symptoms of septic arthritis include limb pain, joint effusion, and a strong tendency for the patient to hold the affected joint in the position of maximal intracapsular volume in order to minimize discomfort. Neonates and infants may present with pseudoparalysis in response to the joint pain.

The log-roll technique is an effective way to detect hip effusion on clinical examination. With the patient lying supine on the examination table, the examiner places one hand at the ankle and another on the thigh and rolls the leg back and forth. Hip effusion can also be detected by ultrasound or MRI. However, it’s important to recognize that the presence of hip effusion doesn’t distinguish septic arthritis from transient synovitis.

Diagnosis of septic arthritis is based upon a combination of clinical findings and analysis of synovial fluid obtained via joint aspiration. Septic arthritis is suggested by an opaque, yellow-to-green synovial fluid with an elevated WBC, at least 75% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and a glucose concentration of only about 30% of that in blood.

The initial antibiotic therapy should be selected before synovial fluid culture results are available. The child’s age is an important consideration, as the causative organisms vary. Haemophilus influenzae was the most common pathogen in children younger than 5 years of age until the vaccine entered wide use. Now Staphylococcus aureus is No. 1 in all age groups, and community-acquired MRSA (methicillin-resistant S. aureus) is an important consideration.

In neonates, other organisms include group B streptococcus, Streptococcus viridans, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, gram-negative enteric bacteria including Escherichia coli and group A streptococcus.

An important and underappreciated cause of septic arthritis in non-neonates younger than age 5 years is Kingella kingae. It is typically culture-negative but can be detected by polymerase chain reaction. In addition, Neisseria meningitidis is a consideration in this age group and all the way through adolescence, as well.

Ms. Heizer declared having no financial conflicts.

EXPERT OPINION FROM A CONFERENCE ON PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES SPONSORED BY CHILDREN'S HOSPITAL COLORADO

Differentiating Dengue from Chikungunya in Returned Travelers

VAIL, COLO. – Dengue fever and chikungunya have much in common in terms of symptoms, incubation period, clinical course, vector, and geographical distribution.

There is, however, a good way to distinguish the two tropical fevers based upon presenting symptoms: Dengue plus arthritis equals chikungunya, Dr. Jay S. Keystone said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.

For fever in a traveler returned from Southeast Asia, the Caribbean, or Latin America, think "dengue" after first ruling out malaria. Studies show that dengue is in fact the most common cause of fever in returned travelers from those areas. There is not so much malaria in those parts of the world, in contrast to sub-Saharan Africa, where malaria accounts for nearly two-thirds of febrile illnesses in returned travelers, noted Dr. Keystone, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto and a past president of the International Society of Travel Medicine.

Both dengue and chikungunya are viral diseases whose vector is the Aedes aegypti mosquito. Chikungunya has as an additional vector, the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus). Chikungunya is a problem in Southeast Asia, as is dengue, but also in India and sub-Saharan Africa.

A key feature shared by both diseases is that the fever comes on sharply about a week after exposure and lasts about a week before resolving. Dengue fever classically is accompanied by a headache, retro-orbital pain, prominent muscle aches, and adenopathy. Similarly, chikungunya features prominent headache and adenopathy, but instead of the myalgia that is so characteristic of dengue, chikungunya entails marked joint pain and arthritis.

"Joint pain is the difference between the two. In adults, the arthritis can go on for many months," according to Dr. Keystone.

A maculopapular rash is common beginning on about day 3 in patients with chikungunya, especially so in children.

Diagnosis of dengue fever is made serologically on the basis of the detection of antibodies to dengue virus. Chikungunya, too, is diagnosed serologically.

Treatment of both tropical fevers is symptomatic. However, NSAIDs are to be avoided because of capillary fragility and increased bleeding risk.

Dengue and chikungunya share one more thing: Medical epidemiologists and entomologists are worried that both diseases may be on the march. The North American habitat of A. aegypti extends north as far as Chicago, and last year a first-ever outbreak of 28 cases of dengue fever was reported in the Florida Keys. Similarly, a substantial outbreak of chikungunya occurred several years ago in Italy, probably as a result of the chikungunya virus spreading through the local Asian tiger mosquito population via exposure to an infected returned traveler.

Dr. Keystone declared having no relevant financial disclosures.

VAIL, COLO. – Dengue fever and chikungunya have much in common in terms of symptoms, incubation period, clinical course, vector, and geographical distribution.

There is, however, a good way to distinguish the two tropical fevers based upon presenting symptoms: Dengue plus arthritis equals chikungunya, Dr. Jay S. Keystone said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.

For fever in a traveler returned from Southeast Asia, the Caribbean, or Latin America, think "dengue" after first ruling out malaria. Studies show that dengue is in fact the most common cause of fever in returned travelers from those areas. There is not so much malaria in those parts of the world, in contrast to sub-Saharan Africa, where malaria accounts for nearly two-thirds of febrile illnesses in returned travelers, noted Dr. Keystone, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto and a past president of the International Society of Travel Medicine.

Both dengue and chikungunya are viral diseases whose vector is the Aedes aegypti mosquito. Chikungunya has as an additional vector, the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus). Chikungunya is a problem in Southeast Asia, as is dengue, but also in India and sub-Saharan Africa.

A key feature shared by both diseases is that the fever comes on sharply about a week after exposure and lasts about a week before resolving. Dengue fever classically is accompanied by a headache, retro-orbital pain, prominent muscle aches, and adenopathy. Similarly, chikungunya features prominent headache and adenopathy, but instead of the myalgia that is so characteristic of dengue, chikungunya entails marked joint pain and arthritis.

"Joint pain is the difference between the two. In adults, the arthritis can go on for many months," according to Dr. Keystone.

A maculopapular rash is common beginning on about day 3 in patients with chikungunya, especially so in children.

Diagnosis of dengue fever is made serologically on the basis of the detection of antibodies to dengue virus. Chikungunya, too, is diagnosed serologically.

Treatment of both tropical fevers is symptomatic. However, NSAIDs are to be avoided because of capillary fragility and increased bleeding risk.

Dengue and chikungunya share one more thing: Medical epidemiologists and entomologists are worried that both diseases may be on the march. The North American habitat of A. aegypti extends north as far as Chicago, and last year a first-ever outbreak of 28 cases of dengue fever was reported in the Florida Keys. Similarly, a substantial outbreak of chikungunya occurred several years ago in Italy, probably as a result of the chikungunya virus spreading through the local Asian tiger mosquito population via exposure to an infected returned traveler.

Dr. Keystone declared having no relevant financial disclosures.

VAIL, COLO. – Dengue fever and chikungunya have much in common in terms of symptoms, incubation period, clinical course, vector, and geographical distribution.

There is, however, a good way to distinguish the two tropical fevers based upon presenting symptoms: Dengue plus arthritis equals chikungunya, Dr. Jay S. Keystone said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.

For fever in a traveler returned from Southeast Asia, the Caribbean, or Latin America, think "dengue" after first ruling out malaria. Studies show that dengue is in fact the most common cause of fever in returned travelers from those areas. There is not so much malaria in those parts of the world, in contrast to sub-Saharan Africa, where malaria accounts for nearly two-thirds of febrile illnesses in returned travelers, noted Dr. Keystone, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto and a past president of the International Society of Travel Medicine.

Both dengue and chikungunya are viral diseases whose vector is the Aedes aegypti mosquito. Chikungunya has as an additional vector, the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus). Chikungunya is a problem in Southeast Asia, as is dengue, but also in India and sub-Saharan Africa.

A key feature shared by both diseases is that the fever comes on sharply about a week after exposure and lasts about a week before resolving. Dengue fever classically is accompanied by a headache, retro-orbital pain, prominent muscle aches, and adenopathy. Similarly, chikungunya features prominent headache and adenopathy, but instead of the myalgia that is so characteristic of dengue, chikungunya entails marked joint pain and arthritis.

"Joint pain is the difference between the two. In adults, the arthritis can go on for many months," according to Dr. Keystone.

A maculopapular rash is common beginning on about day 3 in patients with chikungunya, especially so in children.

Diagnosis of dengue fever is made serologically on the basis of the detection of antibodies to dengue virus. Chikungunya, too, is diagnosed serologically.

Treatment of both tropical fevers is symptomatic. However, NSAIDs are to be avoided because of capillary fragility and increased bleeding risk.

Dengue and chikungunya share one more thing: Medical epidemiologists and entomologists are worried that both diseases may be on the march. The North American habitat of A. aegypti extends north as far as Chicago, and last year a first-ever outbreak of 28 cases of dengue fever was reported in the Florida Keys. Similarly, a substantial outbreak of chikungunya occurred several years ago in Italy, probably as a result of the chikungunya virus spreading through the local Asian tiger mosquito population via exposure to an infected returned traveler.

Dr. Keystone declared having no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A CONFERENCE ON PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES SPONSORED BY CHILDREN'S HOSPITAL COLORADO

Fever in Returned Traveler: Think Malaria First

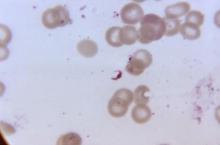

VAIL, COLO. – Fever in a traveler back from the tropics is malaria until proven otherwise – and it’s a medical emergency, Dr. Jay S. Keystone said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.

"Death from malaria can occur in 3-4 days. Not always, but it can. That’s all it takes," said Dr. Keystone, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto and a past president of the International Society of Travel Medicine.

If it’s malaria due to Plasmodium falciparum in a nonimmune patient – and children should be assumed to be nonimmune – hospital admission for up to 48 hours is warranted, even if only minimal parasitemia is present. There’s no need to keep the patient in the hospital until the parasitemia is zero; once the parasitemia is falling in response to therapy, monitoring can safely be accomplished on an outpatient basis with daily blood films until the patient has fully recovered.

Why admit a patient with mere low-level P. falciparum parasitemia? Dr. Keystone has seen returned travelers with a several-day history of fever go from 1% to 30% parasitemia in the course of just 9 hours.

"You really don’t know the parasitemia mass when you’re looking at the blood film because most of the falciparum develops in the microcirculation," he explained.

The one exception to his maximum 48-hour hospitalization rule is in patients with a heavy P. falciparum infection as defined by 5% or greater parasitemia. Onset of adult respiratory distress syndrome in such patients often occurs on day 3-4 of treatment, just as they’re starting to look markedly better and their parasitemia is coming down.

The clinical hallmark of malaria is fever. "That’s the only thing you have to know about what malaria looks like. And if there’s no periodicity to the fever, ignore that; malaria is still in the differential diagnosis," Dr. Keystone said. "For falciparum, the fever you’re most worried about, there really is only rarely periodicity, especially in children. If, however, there is an exact periodicity – fever every other day, every third day, et cetera – it can only be malaria."

In a study Dr. Keystone coauthored that provided the first systematic evaluation of illness in returned pediatric travelers, febrile illness was the presenting complaint in 23% of 1,591 ill children seen at 51 tropical medicine clinics in the GeoSentinel Global Surveillance Network maintained by the International Society of Travel Medicine and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In fact, fever was the third most common presenting complaint, after diarrhea in 28% of patients and dermatologic conditions in 25%.

Of 358 ill returned pediatric travelers with fever, malaria was the No. 1 cause, accounting for 35% of cases, followed by upper respiratory tract infections and other viral illnesses in 28% (Pediatrics 2010;125: 1072-80).

The diagnosis of malaria is made based upon thick blood films; speciation is based upon thin films. If the first blood film is negative, testing should be repeated daily for 2 additional days; otherwise, it’s quite possible to miss parasitemia.

As an alternative to the time-honored thick blood films, Dr. Keystone strongly recommended the use of rapid diagnostic tests, in which malaria is diagnosed based upon detection of malaria antigen in the blood. These tests have been shown to have 99% sensitivity and 94% specificity for P. falciparum infection, and 94% sensitivity and 100% specificity for Plasmodium vivax.

"In Ontario, that’s all we do – we do the rapid diagnostic test, then thin blood films looking for the species and the parasitemia. Rapid diagnostic tests are especially good if your lab doesn’t have a lot of experience with malaria, as you’d expect in a place such as Colorado," he noted.

Parasitemia of 1% or greater is due to P. falciparum more than 90% of the time. In parasitemia, 5% is a critical number; at that level, parenteral therapy is warranted and there is a risk of death.

"At 10% or more, it’s time to change your underwear," Dr. Keystone quipped. "You’ve got a serious problem. At that point, you’re always thinking about exchange transfusion."

Recognizing and Treating Malaria in the United States

Who brings malaria back to the United States from abroad? A recent CDC analysis of cases imported during 2009 concluded that U.S. immigrants who had been visiting friends and relatives abroad accounted for 63% of cases. Missionaries made up another 10%, with the remainder being divided between tourists, business travelers, and students (MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2011 Apr;60:1-15).

A review of 13 North American and European clinical studies highlighted differences between children and adults in the presenting signs and symptoms of malaria. The majority of children had fever in excess of 40°C, compared with just a quarter of adults. The same was true of hepatosplenomegaly and anemia. Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea were very common in children, whereas the most common nonspecific symptoms in adults were headache and myalgia. Thrombocytopenia was extremely common in both groups (Lancet Infect. Dis. 2007;7:349-57).

Every medical student has to learn the four human malaria parasites: P. falciparum, vivax, malariae, and ovale. Recently a fifth has been identified: Plasmodium knowlesi. And it’s a pip.

"It’s a monkey malaria that’s now in the human population. Knowlesi is found mainly in Southeast Asia, especially in the border areas of Thailand. It is one of the fatal malarias. It looks benign and like [Plasmodium] malariae under the microscope, but it kills like P. falciparum. So if you see someone from Southeast Asia who’s very sick and it looks like malariae, think about knowlesi," Dr. Keystone urged.

Two very good medications are available in the United States for treatment of malaria. For patients with heavy parasitemia or severe malaria as defined by cerebral, respiratory, or renal manifestations or severe anemia, intravenous artemether/lumefantrine (Coartem) is the treatment of choice because it’s faster acting, with an average parasite clearance time of 2 days, compared to 4 days with atovaquone/proguanil (Malarone). However, atovaquone/proguanil is better tolerated and thus a good choice in patients with less than 5% parasitemia who don’t have severe disease, he said.

For more information on travel medicine, Dr. Keystone recommends the following resources:

• Text: "Control of Communicable Diseases Manual," 19th Edition, edited by Dr. David L. Heymann. An official report of the American Public Health Association. Available in paperback at Amazon.com for about $23.

"It’s a brilliant book," Dr. Keystone said. "The beauty of this book is it doesn’t just give you the epidemiology and incubation, it gives you the period of communicability, and it’s all laid out in easy form. I would highly advise you that if you don’t have one of these in the office, it’s definitely worth having."

• Web: Every infectious diseases program should have a subscription to Gideon, Dr. Keystone said. Plug in the pertinent facts regarding a case and Gideon spits out the complete differential diagnosis, with the possibilities rank-ordered and accompanying treatment recommendations. Physicians can obtain a free 15-day trial through the website.

"Gideon is probably the best geographic, computer-based, online program for infectious diseases that I know of. You don’t have to be smart to know everything about tropical medicine. If you’re looking for something to help you diagnose tropical diseases, this would be the one," he said.

• Phone: 770-488-7788 connects you to the CDC’s malaria branch.

Dr. Keystone disclosed that he is a consultant to Gideon.

VAIL, COLO. – Fever in a traveler back from the tropics is malaria until proven otherwise – and it’s a medical emergency, Dr. Jay S. Keystone said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.

"Death from malaria can occur in 3-4 days. Not always, but it can. That’s all it takes," said Dr. Keystone, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto and a past president of the International Society of Travel Medicine.

If it’s malaria due to Plasmodium falciparum in a nonimmune patient – and children should be assumed to be nonimmune – hospital admission for up to 48 hours is warranted, even if only minimal parasitemia is present. There’s no need to keep the patient in the hospital until the parasitemia is zero; once the parasitemia is falling in response to therapy, monitoring can safely be accomplished on an outpatient basis with daily blood films until the patient has fully recovered.

Why admit a patient with mere low-level P. falciparum parasitemia? Dr. Keystone has seen returned travelers with a several-day history of fever go from 1% to 30% parasitemia in the course of just 9 hours.

"You really don’t know the parasitemia mass when you’re looking at the blood film because most of the falciparum develops in the microcirculation," he explained.

The one exception to his maximum 48-hour hospitalization rule is in patients with a heavy P. falciparum infection as defined by 5% or greater parasitemia. Onset of adult respiratory distress syndrome in such patients often occurs on day 3-4 of treatment, just as they’re starting to look markedly better and their parasitemia is coming down.

The clinical hallmark of malaria is fever. "That’s the only thing you have to know about what malaria looks like. And if there’s no periodicity to the fever, ignore that; malaria is still in the differential diagnosis," Dr. Keystone said. "For falciparum, the fever you’re most worried about, there really is only rarely periodicity, especially in children. If, however, there is an exact periodicity – fever every other day, every third day, et cetera – it can only be malaria."

In a study Dr. Keystone coauthored that provided the first systematic evaluation of illness in returned pediatric travelers, febrile illness was the presenting complaint in 23% of 1,591 ill children seen at 51 tropical medicine clinics in the GeoSentinel Global Surveillance Network maintained by the International Society of Travel Medicine and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In fact, fever was the third most common presenting complaint, after diarrhea in 28% of patients and dermatologic conditions in 25%.

Of 358 ill returned pediatric travelers with fever, malaria was the No. 1 cause, accounting for 35% of cases, followed by upper respiratory tract infections and other viral illnesses in 28% (Pediatrics 2010;125: 1072-80).

The diagnosis of malaria is made based upon thick blood films; speciation is based upon thin films. If the first blood film is negative, testing should be repeated daily for 2 additional days; otherwise, it’s quite possible to miss parasitemia.

As an alternative to the time-honored thick blood films, Dr. Keystone strongly recommended the use of rapid diagnostic tests, in which malaria is diagnosed based upon detection of malaria antigen in the blood. These tests have been shown to have 99% sensitivity and 94% specificity for P. falciparum infection, and 94% sensitivity and 100% specificity for Plasmodium vivax.

"In Ontario, that’s all we do – we do the rapid diagnostic test, then thin blood films looking for the species and the parasitemia. Rapid diagnostic tests are especially good if your lab doesn’t have a lot of experience with malaria, as you’d expect in a place such as Colorado," he noted.

Parasitemia of 1% or greater is due to P. falciparum more than 90% of the time. In parasitemia, 5% is a critical number; at that level, parenteral therapy is warranted and there is a risk of death.

"At 10% or more, it’s time to change your underwear," Dr. Keystone quipped. "You’ve got a serious problem. At that point, you’re always thinking about exchange transfusion."

Recognizing and Treating Malaria in the United States

Who brings malaria back to the United States from abroad? A recent CDC analysis of cases imported during 2009 concluded that U.S. immigrants who had been visiting friends and relatives abroad accounted for 63% of cases. Missionaries made up another 10%, with the remainder being divided between tourists, business travelers, and students (MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2011 Apr;60:1-15).

A review of 13 North American and European clinical studies highlighted differences between children and adults in the presenting signs and symptoms of malaria. The majority of children had fever in excess of 40°C, compared with just a quarter of adults. The same was true of hepatosplenomegaly and anemia. Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea were very common in children, whereas the most common nonspecific symptoms in adults were headache and myalgia. Thrombocytopenia was extremely common in both groups (Lancet Infect. Dis. 2007;7:349-57).

Every medical student has to learn the four human malaria parasites: P. falciparum, vivax, malariae, and ovale. Recently a fifth has been identified: Plasmodium knowlesi. And it’s a pip.

"It’s a monkey malaria that’s now in the human population. Knowlesi is found mainly in Southeast Asia, especially in the border areas of Thailand. It is one of the fatal malarias. It looks benign and like [Plasmodium] malariae under the microscope, but it kills like P. falciparum. So if you see someone from Southeast Asia who’s very sick and it looks like malariae, think about knowlesi," Dr. Keystone urged.

Two very good medications are available in the United States for treatment of malaria. For patients with heavy parasitemia or severe malaria as defined by cerebral, respiratory, or renal manifestations or severe anemia, intravenous artemether/lumefantrine (Coartem) is the treatment of choice because it’s faster acting, with an average parasite clearance time of 2 days, compared to 4 days with atovaquone/proguanil (Malarone). However, atovaquone/proguanil is better tolerated and thus a good choice in patients with less than 5% parasitemia who don’t have severe disease, he said.

For more information on travel medicine, Dr. Keystone recommends the following resources:

• Text: "Control of Communicable Diseases Manual," 19th Edition, edited by Dr. David L. Heymann. An official report of the American Public Health Association. Available in paperback at Amazon.com for about $23.

"It’s a brilliant book," Dr. Keystone said. "The beauty of this book is it doesn’t just give you the epidemiology and incubation, it gives you the period of communicability, and it’s all laid out in easy form. I would highly advise you that if you don’t have one of these in the office, it’s definitely worth having."

• Web: Every infectious diseases program should have a subscription to Gideon, Dr. Keystone said. Plug in the pertinent facts regarding a case and Gideon spits out the complete differential diagnosis, with the possibilities rank-ordered and accompanying treatment recommendations. Physicians can obtain a free 15-day trial through the website.

"Gideon is probably the best geographic, computer-based, online program for infectious diseases that I know of. You don’t have to be smart to know everything about tropical medicine. If you’re looking for something to help you diagnose tropical diseases, this would be the one," he said.

• Phone: 770-488-7788 connects you to the CDC’s malaria branch.

Dr. Keystone disclosed that he is a consultant to Gideon.

VAIL, COLO. – Fever in a traveler back from the tropics is malaria until proven otherwise – and it’s a medical emergency, Dr. Jay S. Keystone said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.

"Death from malaria can occur in 3-4 days. Not always, but it can. That’s all it takes," said Dr. Keystone, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto and a past president of the International Society of Travel Medicine.

If it’s malaria due to Plasmodium falciparum in a nonimmune patient – and children should be assumed to be nonimmune – hospital admission for up to 48 hours is warranted, even if only minimal parasitemia is present. There’s no need to keep the patient in the hospital until the parasitemia is zero; once the parasitemia is falling in response to therapy, monitoring can safely be accomplished on an outpatient basis with daily blood films until the patient has fully recovered.

Why admit a patient with mere low-level P. falciparum parasitemia? Dr. Keystone has seen returned travelers with a several-day history of fever go from 1% to 30% parasitemia in the course of just 9 hours.

"You really don’t know the parasitemia mass when you’re looking at the blood film because most of the falciparum develops in the microcirculation," he explained.

The one exception to his maximum 48-hour hospitalization rule is in patients with a heavy P. falciparum infection as defined by 5% or greater parasitemia. Onset of adult respiratory distress syndrome in such patients often occurs on day 3-4 of treatment, just as they’re starting to look markedly better and their parasitemia is coming down.

The clinical hallmark of malaria is fever. "That’s the only thing you have to know about what malaria looks like. And if there’s no periodicity to the fever, ignore that; malaria is still in the differential diagnosis," Dr. Keystone said. "For falciparum, the fever you’re most worried about, there really is only rarely periodicity, especially in children. If, however, there is an exact periodicity – fever every other day, every third day, et cetera – it can only be malaria."

In a study Dr. Keystone coauthored that provided the first systematic evaluation of illness in returned pediatric travelers, febrile illness was the presenting complaint in 23% of 1,591 ill children seen at 51 tropical medicine clinics in the GeoSentinel Global Surveillance Network maintained by the International Society of Travel Medicine and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In fact, fever was the third most common presenting complaint, after diarrhea in 28% of patients and dermatologic conditions in 25%.

Of 358 ill returned pediatric travelers with fever, malaria was the No. 1 cause, accounting for 35% of cases, followed by upper respiratory tract infections and other viral illnesses in 28% (Pediatrics 2010;125: 1072-80).

The diagnosis of malaria is made based upon thick blood films; speciation is based upon thin films. If the first blood film is negative, testing should be repeated daily for 2 additional days; otherwise, it’s quite possible to miss parasitemia.

As an alternative to the time-honored thick blood films, Dr. Keystone strongly recommended the use of rapid diagnostic tests, in which malaria is diagnosed based upon detection of malaria antigen in the blood. These tests have been shown to have 99% sensitivity and 94% specificity for P. falciparum infection, and 94% sensitivity and 100% specificity for Plasmodium vivax.

"In Ontario, that’s all we do – we do the rapid diagnostic test, then thin blood films looking for the species and the parasitemia. Rapid diagnostic tests are especially good if your lab doesn’t have a lot of experience with malaria, as you’d expect in a place such as Colorado," he noted.

Parasitemia of 1% or greater is due to P. falciparum more than 90% of the time. In parasitemia, 5% is a critical number; at that level, parenteral therapy is warranted and there is a risk of death.

"At 10% or more, it’s time to change your underwear," Dr. Keystone quipped. "You’ve got a serious problem. At that point, you’re always thinking about exchange transfusion."

Recognizing and Treating Malaria in the United States

Who brings malaria back to the United States from abroad? A recent CDC analysis of cases imported during 2009 concluded that U.S. immigrants who had been visiting friends and relatives abroad accounted for 63% of cases. Missionaries made up another 10%, with the remainder being divided between tourists, business travelers, and students (MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2011 Apr;60:1-15).

A review of 13 North American and European clinical studies highlighted differences between children and adults in the presenting signs and symptoms of malaria. The majority of children had fever in excess of 40°C, compared with just a quarter of adults. The same was true of hepatosplenomegaly and anemia. Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea were very common in children, whereas the most common nonspecific symptoms in adults were headache and myalgia. Thrombocytopenia was extremely common in both groups (Lancet Infect. Dis. 2007;7:349-57).

Every medical student has to learn the four human malaria parasites: P. falciparum, vivax, malariae, and ovale. Recently a fifth has been identified: Plasmodium knowlesi. And it’s a pip.

"It’s a monkey malaria that’s now in the human population. Knowlesi is found mainly in Southeast Asia, especially in the border areas of Thailand. It is one of the fatal malarias. It looks benign and like [Plasmodium] malariae under the microscope, but it kills like P. falciparum. So if you see someone from Southeast Asia who’s very sick and it looks like malariae, think about knowlesi," Dr. Keystone urged.

Two very good medications are available in the United States for treatment of malaria. For patients with heavy parasitemia or severe malaria as defined by cerebral, respiratory, or renal manifestations or severe anemia, intravenous artemether/lumefantrine (Coartem) is the treatment of choice because it’s faster acting, with an average parasite clearance time of 2 days, compared to 4 days with atovaquone/proguanil (Malarone). However, atovaquone/proguanil is better tolerated and thus a good choice in patients with less than 5% parasitemia who don’t have severe disease, he said.

For more information on travel medicine, Dr. Keystone recommends the following resources:

• Text: "Control of Communicable Diseases Manual," 19th Edition, edited by Dr. David L. Heymann. An official report of the American Public Health Association. Available in paperback at Amazon.com for about $23.

"It’s a brilliant book," Dr. Keystone said. "The beauty of this book is it doesn’t just give you the epidemiology and incubation, it gives you the period of communicability, and it’s all laid out in easy form. I would highly advise you that if you don’t have one of these in the office, it’s definitely worth having."

• Web: Every infectious diseases program should have a subscription to Gideon, Dr. Keystone said. Plug in the pertinent facts regarding a case and Gideon spits out the complete differential diagnosis, with the possibilities rank-ordered and accompanying treatment recommendations. Physicians can obtain a free 15-day trial through the website.

"Gideon is probably the best geographic, computer-based, online program for infectious diseases that I know of. You don’t have to be smart to know everything about tropical medicine. If you’re looking for something to help you diagnose tropical diseases, this would be the one," he said.

• Phone: 770-488-7788 connects you to the CDC’s malaria branch.

Dr. Keystone disclosed that he is a consultant to Gideon.

EXPERT OPINION FROM A CONFERENCE ON PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES

IGRAs Are TB Test Alternative After Age 5 Years

VAIL, COLO. – Interferon-gamma release assays offer significant advantages over conventional tuberculin skin testing under certain circumstances, but not in children younger than 5 years old.

The IFN-gamma release assays (IGRAs) have not been well studied in children younger than age 5 years, plus the available data suggest that the test results are less reliable in this age group. Given the high rate of progression from latent to active disease as well as the high rates of severe disease in this younger population, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends using the tuberculin skin test (TST) for these young children, Dr. Donna Curtis said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.

Beyond age 5 years, however, the sensitivity and specificity of IGRAs and the TST are similar, and the tests can be used interchangeably, added Dr. Curtis of the University of Colorado at Denver.

IGRAs are blood tests that measure IFN-gamma production by WBCs in response to stimulation by TB antigens. The two Food and Drug Administration–approved IGRAs on the market are Cellistis’s QuantiFERON–TB Gold In-Tube test and Oxford Immunotec’s T-SPOT.TB test. The test results are reported from the laboratory as positive, negative, or indeterminate.

Among the IGRAs’ advantages are that only a single patient visit is required and results are available 24 hours after laboratory processing. Also, there are no false-positives due to previous BCG (bacille Calmette-Guérin) vaccination, a big problem with TSTs in foreign-born patients. And unlike the TST, there is no boosting phenomenon with repeated IGRA tests.

On the other hand, an IGRA requires fresh blood and plenty of it – 4 tubes’ worth – and it must be transported promptly to the laboratory for processing. The cost, albeit variable, is often more than that of a TST.

An IGRA is clearly the preferred test in patients older than age 5 years who have received a BCG vaccine, and in those with a reduced likelihood of returning for a second visit to have their TST read (such as substance abusers, people with transportation difficulties, and patients in homeless shelters).

As with TSTs, IGRAs should be used only to test patients with a TB exposure or risk factors. Otherwise, the odds of a false-positive test are greatly increased. After all, fewer than 1% of the noninstitutionalized U.S. population with no risk factors has a latent TB infection.

The CDC recommends both the IGRA and TST in patients whose first test is negative but who have a high risk of infection or progression to active disease. The health agency also recommends both tests as useful when the first test is positive and additional evidence is needed to convince the patient or family to undergo treatment.

Dr. Curtis noted that a recent Croatian study involving 142 BCG-vaccinated children younger than age 5 with a known TB exposure – all of whom had both a TST and IGRA – found a high rate of discordant results. The investigators concluded that both tests should routinely be used in this age group, and that a child should be considered infected if either or both results are positive (Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2011 May 12 [Epub ahead of print]).

However, Dr. John W. Ogle commented that the dual-test strategy for younger children is fraught with problems.

"There are no normative data for IGRAs in kids under age 5 years. The IGRAs are standardized on adult patients. The amount of interferon that you make in response to an antigen is age dependent; kids less than age 5 make much less compared to adults. So if you do an IGRA in a young kid, you’re much more likely to have a false-negative result. Families will beg you to do an IGRA because they’ve learned this on the Internet and they don’t want their child to have to be exposed to the medical treatment," explained Dr. Ogle, professor and vice chair of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver and director of pediatric services at Denver Health Medical Center.

A year ago, the CDC issued updated guidelines for the use of IGRAs (MMWR 2010; 59[RR-5];1-25).Dr. Curtis said physicians with any questions about IGRAs will find this publication quite helpful, even though it includes studies published only through 2008.

She declared having no financial conflicts.

VAIL, COLO. – Interferon-gamma release assays offer significant advantages over conventional tuberculin skin testing under certain circumstances, but not in children younger than 5 years old.

The IFN-gamma release assays (IGRAs) have not been well studied in children younger than age 5 years, plus the available data suggest that the test results are less reliable in this age group. Given the high rate of progression from latent to active disease as well as the high rates of severe disease in this younger population, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends using the tuberculin skin test (TST) for these young children, Dr. Donna Curtis said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.

Beyond age 5 years, however, the sensitivity and specificity of IGRAs and the TST are similar, and the tests can be used interchangeably, added Dr. Curtis of the University of Colorado at Denver.

IGRAs are blood tests that measure IFN-gamma production by WBCs in response to stimulation by TB antigens. The two Food and Drug Administration–approved IGRAs on the market are Cellistis’s QuantiFERON–TB Gold In-Tube test and Oxford Immunotec’s T-SPOT.TB test. The test results are reported from the laboratory as positive, negative, or indeterminate.

Among the IGRAs’ advantages are that only a single patient visit is required and results are available 24 hours after laboratory processing. Also, there are no false-positives due to previous BCG (bacille Calmette-Guérin) vaccination, a big problem with TSTs in foreign-born patients. And unlike the TST, there is no boosting phenomenon with repeated IGRA tests.

On the other hand, an IGRA requires fresh blood and plenty of it – 4 tubes’ worth – and it must be transported promptly to the laboratory for processing. The cost, albeit variable, is often more than that of a TST.

An IGRA is clearly the preferred test in patients older than age 5 years who have received a BCG vaccine, and in those with a reduced likelihood of returning for a second visit to have their TST read (such as substance abusers, people with transportation difficulties, and patients in homeless shelters).

As with TSTs, IGRAs should be used only to test patients with a TB exposure or risk factors. Otherwise, the odds of a false-positive test are greatly increased. After all, fewer than 1% of the noninstitutionalized U.S. population with no risk factors has a latent TB infection.

The CDC recommends both the IGRA and TST in patients whose first test is negative but who have a high risk of infection or progression to active disease. The health agency also recommends both tests as useful when the first test is positive and additional evidence is needed to convince the patient or family to undergo treatment.

Dr. Curtis noted that a recent Croatian study involving 142 BCG-vaccinated children younger than age 5 with a known TB exposure – all of whom had both a TST and IGRA – found a high rate of discordant results. The investigators concluded that both tests should routinely be used in this age group, and that a child should be considered infected if either or both results are positive (Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2011 May 12 [Epub ahead of print]).

However, Dr. John W. Ogle commented that the dual-test strategy for younger children is fraught with problems.

"There are no normative data for IGRAs in kids under age 5 years. The IGRAs are standardized on adult patients. The amount of interferon that you make in response to an antigen is age dependent; kids less than age 5 make much less compared to adults. So if you do an IGRA in a young kid, you’re much more likely to have a false-negative result. Families will beg you to do an IGRA because they’ve learned this on the Internet and they don’t want their child to have to be exposed to the medical treatment," explained Dr. Ogle, professor and vice chair of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver and director of pediatric services at Denver Health Medical Center.

A year ago, the CDC issued updated guidelines for the use of IGRAs (MMWR 2010; 59[RR-5];1-25).Dr. Curtis said physicians with any questions about IGRAs will find this publication quite helpful, even though it includes studies published only through 2008.

She declared having no financial conflicts.

VAIL, COLO. – Interferon-gamma release assays offer significant advantages over conventional tuberculin skin testing under certain circumstances, but not in children younger than 5 years old.

The IFN-gamma release assays (IGRAs) have not been well studied in children younger than age 5 years, plus the available data suggest that the test results are less reliable in this age group. Given the high rate of progression from latent to active disease as well as the high rates of severe disease in this younger population, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends using the tuberculin skin test (TST) for these young children, Dr. Donna Curtis said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.

Beyond age 5 years, however, the sensitivity and specificity of IGRAs and the TST are similar, and the tests can be used interchangeably, added Dr. Curtis of the University of Colorado at Denver.

IGRAs are blood tests that measure IFN-gamma production by WBCs in response to stimulation by TB antigens. The two Food and Drug Administration–approved IGRAs on the market are Cellistis’s QuantiFERON–TB Gold In-Tube test and Oxford Immunotec’s T-SPOT.TB test. The test results are reported from the laboratory as positive, negative, or indeterminate.

Among the IGRAs’ advantages are that only a single patient visit is required and results are available 24 hours after laboratory processing. Also, there are no false-positives due to previous BCG (bacille Calmette-Guérin) vaccination, a big problem with TSTs in foreign-born patients. And unlike the TST, there is no boosting phenomenon with repeated IGRA tests.

On the other hand, an IGRA requires fresh blood and plenty of it – 4 tubes’ worth – and it must be transported promptly to the laboratory for processing. The cost, albeit variable, is often more than that of a TST.

An IGRA is clearly the preferred test in patients older than age 5 years who have received a BCG vaccine, and in those with a reduced likelihood of returning for a second visit to have their TST read (such as substance abusers, people with transportation difficulties, and patients in homeless shelters).

As with TSTs, IGRAs should be used only to test patients with a TB exposure or risk factors. Otherwise, the odds of a false-positive test are greatly increased. After all, fewer than 1% of the noninstitutionalized U.S. population with no risk factors has a latent TB infection.

The CDC recommends both the IGRA and TST in patients whose first test is negative but who have a high risk of infection or progression to active disease. The health agency also recommends both tests as useful when the first test is positive and additional evidence is needed to convince the patient or family to undergo treatment.

Dr. Curtis noted that a recent Croatian study involving 142 BCG-vaccinated children younger than age 5 with a known TB exposure – all of whom had both a TST and IGRA – found a high rate of discordant results. The investigators concluded that both tests should routinely be used in this age group, and that a child should be considered infected if either or both results are positive (Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2011 May 12 [Epub ahead of print]).

However, Dr. John W. Ogle commented that the dual-test strategy for younger children is fraught with problems.

"There are no normative data for IGRAs in kids under age 5 years. The IGRAs are standardized on adult patients. The amount of interferon that you make in response to an antigen is age dependent; kids less than age 5 make much less compared to adults. So if you do an IGRA in a young kid, you’re much more likely to have a false-negative result. Families will beg you to do an IGRA because they’ve learned this on the Internet and they don’t want their child to have to be exposed to the medical treatment," explained Dr. Ogle, professor and vice chair of pediatrics at the University of Colorado at Denver and director of pediatric services at Denver Health Medical Center.

A year ago, the CDC issued updated guidelines for the use of IGRAs (MMWR 2010; 59[RR-5];1-25).Dr. Curtis said physicians with any questions about IGRAs will find this publication quite helpful, even though it includes studies published only through 2008.

She declared having no financial conflicts.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A CONFERENCE ON PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES SPONSORED BY CHILDREN'S HOSPITAL COLORADO

Reasons Behind ACIP's Off-Label Vaccine Recommendations

VAIL, COLO. – Earlier this year, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices took the unusual step of updating recommendations for the use of the meningococcal conjugate vaccines and Tdap vaccine that are at odds with the Food and Drug Administration–approved licensed indications, Dr. Marc Fisher said.

"It’s sort of unusual for ACIP to make off-label indications," Dr. Fischer observed in presenting an update from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s ACIP at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.