User login

In part 1 of this two-part series (July 2007, p. 16), hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians expressed their views on the relationship between their two specialties. In part 2, we look at how those relationships intersect—and what issues are at stake when they do.

One area where there is a bit of overlap between hospital medicine and emergency medicine is observational medicine,” says James W. Hoekstra, MD, professor and chairman, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest University Health Sciences Center, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Those patients who require a short stay for observation, he says, are neither in the ED or admitted to the hospital—they are in a zone of their own.

“That’s a gray zone in terms of who takes care of those patients,” he says, “and it depends on the hospital. It will be interesting to see how that works out, or whether that is ever worked out. It may just stay a shared area.”

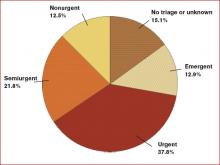

The observation conundrum is complicated by the fact that many people use emergency departments for primary care. (See Figure 1, p. 33) “ True emergencies make up only some of the patient [cases] in the ED,” says Debra L. Burgy, MD, a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis. “We do have a 23-hour observation unit of 10 beds, and, frankly, could use 10 more to [handle unpredictable volumes of patients and insufficient support staff. That unit] has certainly helped to alleviate unnecessary admissions.”

Collaboration between hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians happens a number of ways at the University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center, where Jeff Glasheen, MD, is director of both the hospital medicine program and inpatient clinical services in the department of medicine.

“One way we work closely with the ED—because we think it is the right thing to do—is by building a much more comprehensive observation unit,” Dr. Glasheen says. “In some settings the observation unit lives in the ED and is run by the ED and in others, it is run by hospitalists. The hospitalists [here] will now run the unit, but we want to help solve some of the ED’s throughput issues.”

When Dr. Glasheen arrived at his institution, the observation unit was limited to patients with chest pain. “I didn’t understand why we would get chest pain patients through efficiently and not all patients,” he says.

A team that began operating in July will be available for all patients under the admission status of observation. The team will be hospitalist-led and aim to reduce length of stay and increase quality of care for those patients.

“Right now those patients are very scattered throughout the system and they may be [covered by] six to eight different teams,” Dr. Glasheen explains. One team of caregivers will be more efficient and reduce length of stay, he says.

By nurturing their working relationship with the emergency department, hospitalists will be able to more easily say: “We understand that that workup’s not complete, but we also understand that they’re going to come into the hospital and let us know what things need to be done. We’ll be happy to take that patient a little earlier than we did in the past to get them out of the ED.”

That’s a tricky thing to do, he says, “because the benefit to us isn’t huge, we’re self-sacrificing to help the ED, and that’s what I want hospitalist groups nationally to be thinking: how we can make the whole system better and not just make our own job better.”

Dr. Glasheen believes the professional structure in his institution is representative of what other hospitals will function like in the next 10 years.

“You have a backbone structure of basically four types of physicians: emergency medicine docs, hospitalists, intensivists, and a surgical team,” Dr. Glasheen says. “Everyone else, more and more, is serving in a consultative role.” Having that backbone allows you to tackle the issues, which are primarily complex, systems-based issues, he says. “It is no longer [a matter of just] the ED trying to deal with capacity issues. Now they have an ally on the inpatient side.”

An excess of patients for the number of beds means some patients spend a disproportionate amount of their stay in the ED, and that challenges communication and efficiency. “The challenges may be simple things, such as it being harder for a hospitalist to get to the ED to see a patient than it is upstairs,” Dr. Glasheen says. “[Or] it’s harder to decide who really has ownership of that patient.” In his hospital, as soon as a patient is assigned to a hospitalist, the primary responsibility for that patient is seen as the hospitalist’s.

But there are other issues. “Even if we are able to get down [to the ED] and write orders, that is problematic for the ED and the hospitalist; as a hospitalist we don’t have the nurses with staffing ratios and skills in the ED that they have on floors and in the ICU,” says Dr. Glasheen. “It is not always possible to get things done as efficiently as they probably could if the patients were in a proper unit. Locally and globally in my experience, the biggest issue is: How do you take care of these patients who now spend their inpatient stay in the ED?”

Collaborations, Models, and Solutions

A number of hospitalists raise the issue of managing internal medicine residents doing rotations in the ED.

“We were approached recently by the ED because most of our admissions are called in directly to the medical residents,” says Jason R. Orlinick, MD, PhD, head of the section of Hospital Medicine at Norwalk Hospital, Conn. “I think the ED would like to talk directly with the medical attending assuming care for the patient. One of the things we haven’t done well is meet on a regular basis to discuss communication issues.”

The hospitalists and emergency medicine group at Dr. Orlinick’s institution have entertained the idea of setting up a direct triage system whereby medical residents are taken out of the picture. “The emergency medicine docs would page us directly—at least during the busiest hours of the day. Eventually, the hope is to make it a 24-hour, seven-days-a-week, 365 [days-a-year process],” says Dr. Orlinick. By bringing this to the emergency medicine physicians, the intent was to send the message that hospitalists recognize ED overcrowding as an institutional issue and want to improve communication with their ED colleagues to improve patient care.

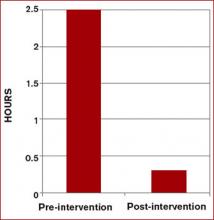

This model, devised at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, enabled communication between ED doctors and hospitalists, and reduced wait times by more than two hours when a bed was available.2 This triage and direct-admission protocol was not associated with increased mortality and resulted in improved patient and physician satisfaction. (See Figure 2 at right). Once the ED attending decides to admit a patient, direct communication is facilitated with a hospitalist. The approach includes monthly meetings between the department of medicine and the ED to continue to discuss improvements in admissions.

At Norwalk Hospital, the administration asked the hospitalist group to intervene in that throughput process. But Dr. Orlinick, also a clinical instructor of medicine at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., says they’ve hesitated out of sensitivity to their ED colleagues.

“We as a group have really struggled with that concept because [although] we feel like that is something we can do well, this is really within the purview of the emergency medicine docs,” says Dr. Orlinick. Adopting the Johns Hopkins model is a win-win solution where each specialty is providing its best skills to solve mutual issues. “What we can do well is look at the patients … on the floor[s], look at flow through the hospital systems in terms of getting testing; make sure that all that—and consults—happen in a timely manner, and that people leave the hospital when they’ve reached their goals of hospitalization,” he says. “It’s afterload as opposed to preload.”

Hospitalists see committee collaboration as important to solving the complex multidisciplinary systemic issues. Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, participates on a pneumonia task force with several hospitalists, a pulmonologist, and one of the heads of the ED. “We address the whole gamut from when patients come in to when they go through the hospital,” says Dr. Gundersen, head of the Hospital Medicine Division, University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester. “We can learn from each other as we go through the process.”

Many of the ways hospitalists and ED physicians tackle systems-related issues are new to Dr. Glasheen’s institution because the hospital medicine program was begun in 2004. It is now common to see higher-level leadership from different specialties and areas all in the same room—talking about issues of capacity, for instance. There are also many more instances of hospitalists and ED physicians sitting on the same committees. Further, “It is relatively common for our ED to call our hospitalists to say, ‘Can you help see this patient? I’m not sure what to do,’ or, ‘I’ve got this situation with this patient, this needs to be done and I need help getting that done,’ ” Dr. Glasheen says. Even though he concedes that is more of a workaround as opposed to a solution for a faulty system, it still represents ED physicians and hospitalists co-managing that workaround.

The Future

Because he “sits on both sides of the fence” between emergency medicine and hospital medicine, Dr. Gundersen thinks it is especially important for hospitalists to train in all the different areas—including emergency medicine—when they are medical students and residents.

Emergency medicine physicians Dr. Hoekstra and Benjamin Honigman, MD, professor of surgery and head of the Division of Emergency Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver, believe hospital medicine will be integral to that training. Dr. Glasheen, also the director of the longest-running internal medicine hospitalist-training program in the U.S., expects greater attention to hospitalist training. “My sense is that many hospitalists groups are in a growth phase and are trying to solve their own problems,” he says. Basically, their primary focus is staffing the hospital with good people and retaining them. He believes that once groups have been around for three to five years, they are more likely to take on bigger issues, such as hospital efficiency and capacity management.

“One of the reasons we started a hospitalist training program is that I didn’t want hospitalists to fall into the same mistakes, barriers, or issues that we’ve had in the past,” Dr. Glasheen says. He fears “this sort of continued balkanization of hospital care, where everyone silos everything out and considers such issues as throughput and ED divert as outside of their [jurisdiction]. I want to get to the place where hospitalists are looking at the whole hospital system and are justly rewarded for that either by financial incentives or time to [work on systemic issues].”

Dr. Glasheen and his team remind themselves of where their commitment resides: “This hospital is where we live—and with everything between the front door to the back door, our primary job is to make this a better place.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Burt CW, McCaig LF. Staffing, capacity, and ambulance diversion in emergency departments: United States, 2003-04. Adv Data; US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Md. Sept. 27, 2006. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad376.pdf. Last accessed June 25, 2007.

- Howell EE, Bessman ES, Rubin HR. Hospitalists and an innovative emergency department admission process. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Mar;19(3):266-268.

In part 1 of this two-part series (July 2007, p. 16), hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians expressed their views on the relationship between their two specialties. In part 2, we look at how those relationships intersect—and what issues are at stake when they do.

One area where there is a bit of overlap between hospital medicine and emergency medicine is observational medicine,” says James W. Hoekstra, MD, professor and chairman, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest University Health Sciences Center, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Those patients who require a short stay for observation, he says, are neither in the ED or admitted to the hospital—they are in a zone of their own.

“That’s a gray zone in terms of who takes care of those patients,” he says, “and it depends on the hospital. It will be interesting to see how that works out, or whether that is ever worked out. It may just stay a shared area.”

The observation conundrum is complicated by the fact that many people use emergency departments for primary care. (See Figure 1, p. 33) “ True emergencies make up only some of the patient [cases] in the ED,” says Debra L. Burgy, MD, a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis. “We do have a 23-hour observation unit of 10 beds, and, frankly, could use 10 more to [handle unpredictable volumes of patients and insufficient support staff. That unit] has certainly helped to alleviate unnecessary admissions.”

Collaboration between hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians happens a number of ways at the University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center, where Jeff Glasheen, MD, is director of both the hospital medicine program and inpatient clinical services in the department of medicine.

“One way we work closely with the ED—because we think it is the right thing to do—is by building a much more comprehensive observation unit,” Dr. Glasheen says. “In some settings the observation unit lives in the ED and is run by the ED and in others, it is run by hospitalists. The hospitalists [here] will now run the unit, but we want to help solve some of the ED’s throughput issues.”

When Dr. Glasheen arrived at his institution, the observation unit was limited to patients with chest pain. “I didn’t understand why we would get chest pain patients through efficiently and not all patients,” he says.

A team that began operating in July will be available for all patients under the admission status of observation. The team will be hospitalist-led and aim to reduce length of stay and increase quality of care for those patients.

“Right now those patients are very scattered throughout the system and they may be [covered by] six to eight different teams,” Dr. Glasheen explains. One team of caregivers will be more efficient and reduce length of stay, he says.

By nurturing their working relationship with the emergency department, hospitalists will be able to more easily say: “We understand that that workup’s not complete, but we also understand that they’re going to come into the hospital and let us know what things need to be done. We’ll be happy to take that patient a little earlier than we did in the past to get them out of the ED.”

That’s a tricky thing to do, he says, “because the benefit to us isn’t huge, we’re self-sacrificing to help the ED, and that’s what I want hospitalist groups nationally to be thinking: how we can make the whole system better and not just make our own job better.”

Dr. Glasheen believes the professional structure in his institution is representative of what other hospitals will function like in the next 10 years.

“You have a backbone structure of basically four types of physicians: emergency medicine docs, hospitalists, intensivists, and a surgical team,” Dr. Glasheen says. “Everyone else, more and more, is serving in a consultative role.” Having that backbone allows you to tackle the issues, which are primarily complex, systems-based issues, he says. “It is no longer [a matter of just] the ED trying to deal with capacity issues. Now they have an ally on the inpatient side.”

An excess of patients for the number of beds means some patients spend a disproportionate amount of their stay in the ED, and that challenges communication and efficiency. “The challenges may be simple things, such as it being harder for a hospitalist to get to the ED to see a patient than it is upstairs,” Dr. Glasheen says. “[Or] it’s harder to decide who really has ownership of that patient.” In his hospital, as soon as a patient is assigned to a hospitalist, the primary responsibility for that patient is seen as the hospitalist’s.

But there are other issues. “Even if we are able to get down [to the ED] and write orders, that is problematic for the ED and the hospitalist; as a hospitalist we don’t have the nurses with staffing ratios and skills in the ED that they have on floors and in the ICU,” says Dr. Glasheen. “It is not always possible to get things done as efficiently as they probably could if the patients were in a proper unit. Locally and globally in my experience, the biggest issue is: How do you take care of these patients who now spend their inpatient stay in the ED?”

Collaborations, Models, and Solutions

A number of hospitalists raise the issue of managing internal medicine residents doing rotations in the ED.

“We were approached recently by the ED because most of our admissions are called in directly to the medical residents,” says Jason R. Orlinick, MD, PhD, head of the section of Hospital Medicine at Norwalk Hospital, Conn. “I think the ED would like to talk directly with the medical attending assuming care for the patient. One of the things we haven’t done well is meet on a regular basis to discuss communication issues.”

The hospitalists and emergency medicine group at Dr. Orlinick’s institution have entertained the idea of setting up a direct triage system whereby medical residents are taken out of the picture. “The emergency medicine docs would page us directly—at least during the busiest hours of the day. Eventually, the hope is to make it a 24-hour, seven-days-a-week, 365 [days-a-year process],” says Dr. Orlinick. By bringing this to the emergency medicine physicians, the intent was to send the message that hospitalists recognize ED overcrowding as an institutional issue and want to improve communication with their ED colleagues to improve patient care.

This model, devised at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, enabled communication between ED doctors and hospitalists, and reduced wait times by more than two hours when a bed was available.2 This triage and direct-admission protocol was not associated with increased mortality and resulted in improved patient and physician satisfaction. (See Figure 2 at right). Once the ED attending decides to admit a patient, direct communication is facilitated with a hospitalist. The approach includes monthly meetings between the department of medicine and the ED to continue to discuss improvements in admissions.

At Norwalk Hospital, the administration asked the hospitalist group to intervene in that throughput process. But Dr. Orlinick, also a clinical instructor of medicine at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., says they’ve hesitated out of sensitivity to their ED colleagues.

“We as a group have really struggled with that concept because [although] we feel like that is something we can do well, this is really within the purview of the emergency medicine docs,” says Dr. Orlinick. Adopting the Johns Hopkins model is a win-win solution where each specialty is providing its best skills to solve mutual issues. “What we can do well is look at the patients … on the floor[s], look at flow through the hospital systems in terms of getting testing; make sure that all that—and consults—happen in a timely manner, and that people leave the hospital when they’ve reached their goals of hospitalization,” he says. “It’s afterload as opposed to preload.”

Hospitalists see committee collaboration as important to solving the complex multidisciplinary systemic issues. Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, participates on a pneumonia task force with several hospitalists, a pulmonologist, and one of the heads of the ED. “We address the whole gamut from when patients come in to when they go through the hospital,” says Dr. Gundersen, head of the Hospital Medicine Division, University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester. “We can learn from each other as we go through the process.”

Many of the ways hospitalists and ED physicians tackle systems-related issues are new to Dr. Glasheen’s institution because the hospital medicine program was begun in 2004. It is now common to see higher-level leadership from different specialties and areas all in the same room—talking about issues of capacity, for instance. There are also many more instances of hospitalists and ED physicians sitting on the same committees. Further, “It is relatively common for our ED to call our hospitalists to say, ‘Can you help see this patient? I’m not sure what to do,’ or, ‘I’ve got this situation with this patient, this needs to be done and I need help getting that done,’ ” Dr. Glasheen says. Even though he concedes that is more of a workaround as opposed to a solution for a faulty system, it still represents ED physicians and hospitalists co-managing that workaround.

The Future

Because he “sits on both sides of the fence” between emergency medicine and hospital medicine, Dr. Gundersen thinks it is especially important for hospitalists to train in all the different areas—including emergency medicine—when they are medical students and residents.

Emergency medicine physicians Dr. Hoekstra and Benjamin Honigman, MD, professor of surgery and head of the Division of Emergency Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver, believe hospital medicine will be integral to that training. Dr. Glasheen, also the director of the longest-running internal medicine hospitalist-training program in the U.S., expects greater attention to hospitalist training. “My sense is that many hospitalists groups are in a growth phase and are trying to solve their own problems,” he says. Basically, their primary focus is staffing the hospital with good people and retaining them. He believes that once groups have been around for three to five years, they are more likely to take on bigger issues, such as hospital efficiency and capacity management.

“One of the reasons we started a hospitalist training program is that I didn’t want hospitalists to fall into the same mistakes, barriers, or issues that we’ve had in the past,” Dr. Glasheen says. He fears “this sort of continued balkanization of hospital care, where everyone silos everything out and considers such issues as throughput and ED divert as outside of their [jurisdiction]. I want to get to the place where hospitalists are looking at the whole hospital system and are justly rewarded for that either by financial incentives or time to [work on systemic issues].”

Dr. Glasheen and his team remind themselves of where their commitment resides: “This hospital is where we live—and with everything between the front door to the back door, our primary job is to make this a better place.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Burt CW, McCaig LF. Staffing, capacity, and ambulance diversion in emergency departments: United States, 2003-04. Adv Data; US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Md. Sept. 27, 2006. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad376.pdf. Last accessed June 25, 2007.

- Howell EE, Bessman ES, Rubin HR. Hospitalists and an innovative emergency department admission process. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Mar;19(3):266-268.

In part 1 of this two-part series (July 2007, p. 16), hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians expressed their views on the relationship between their two specialties. In part 2, we look at how those relationships intersect—and what issues are at stake when they do.

One area where there is a bit of overlap between hospital medicine and emergency medicine is observational medicine,” says James W. Hoekstra, MD, professor and chairman, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest University Health Sciences Center, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Those patients who require a short stay for observation, he says, are neither in the ED or admitted to the hospital—they are in a zone of their own.

“That’s a gray zone in terms of who takes care of those patients,” he says, “and it depends on the hospital. It will be interesting to see how that works out, or whether that is ever worked out. It may just stay a shared area.”

The observation conundrum is complicated by the fact that many people use emergency departments for primary care. (See Figure 1, p. 33) “ True emergencies make up only some of the patient [cases] in the ED,” says Debra L. Burgy, MD, a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis. “We do have a 23-hour observation unit of 10 beds, and, frankly, could use 10 more to [handle unpredictable volumes of patients and insufficient support staff. That unit] has certainly helped to alleviate unnecessary admissions.”

Collaboration between hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians happens a number of ways at the University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center, where Jeff Glasheen, MD, is director of both the hospital medicine program and inpatient clinical services in the department of medicine.

“One way we work closely with the ED—because we think it is the right thing to do—is by building a much more comprehensive observation unit,” Dr. Glasheen says. “In some settings the observation unit lives in the ED and is run by the ED and in others, it is run by hospitalists. The hospitalists [here] will now run the unit, but we want to help solve some of the ED’s throughput issues.”

When Dr. Glasheen arrived at his institution, the observation unit was limited to patients with chest pain. “I didn’t understand why we would get chest pain patients through efficiently and not all patients,” he says.

A team that began operating in July will be available for all patients under the admission status of observation. The team will be hospitalist-led and aim to reduce length of stay and increase quality of care for those patients.

“Right now those patients are very scattered throughout the system and they may be [covered by] six to eight different teams,” Dr. Glasheen explains. One team of caregivers will be more efficient and reduce length of stay, he says.

By nurturing their working relationship with the emergency department, hospitalists will be able to more easily say: “We understand that that workup’s not complete, but we also understand that they’re going to come into the hospital and let us know what things need to be done. We’ll be happy to take that patient a little earlier than we did in the past to get them out of the ED.”

That’s a tricky thing to do, he says, “because the benefit to us isn’t huge, we’re self-sacrificing to help the ED, and that’s what I want hospitalist groups nationally to be thinking: how we can make the whole system better and not just make our own job better.”

Dr. Glasheen believes the professional structure in his institution is representative of what other hospitals will function like in the next 10 years.

“You have a backbone structure of basically four types of physicians: emergency medicine docs, hospitalists, intensivists, and a surgical team,” Dr. Glasheen says. “Everyone else, more and more, is serving in a consultative role.” Having that backbone allows you to tackle the issues, which are primarily complex, systems-based issues, he says. “It is no longer [a matter of just] the ED trying to deal with capacity issues. Now they have an ally on the inpatient side.”

An excess of patients for the number of beds means some patients spend a disproportionate amount of their stay in the ED, and that challenges communication and efficiency. “The challenges may be simple things, such as it being harder for a hospitalist to get to the ED to see a patient than it is upstairs,” Dr. Glasheen says. “[Or] it’s harder to decide who really has ownership of that patient.” In his hospital, as soon as a patient is assigned to a hospitalist, the primary responsibility for that patient is seen as the hospitalist’s.

But there are other issues. “Even if we are able to get down [to the ED] and write orders, that is problematic for the ED and the hospitalist; as a hospitalist we don’t have the nurses with staffing ratios and skills in the ED that they have on floors and in the ICU,” says Dr. Glasheen. “It is not always possible to get things done as efficiently as they probably could if the patients were in a proper unit. Locally and globally in my experience, the biggest issue is: How do you take care of these patients who now spend their inpatient stay in the ED?”

Collaborations, Models, and Solutions

A number of hospitalists raise the issue of managing internal medicine residents doing rotations in the ED.

“We were approached recently by the ED because most of our admissions are called in directly to the medical residents,” says Jason R. Orlinick, MD, PhD, head of the section of Hospital Medicine at Norwalk Hospital, Conn. “I think the ED would like to talk directly with the medical attending assuming care for the patient. One of the things we haven’t done well is meet on a regular basis to discuss communication issues.”

The hospitalists and emergency medicine group at Dr. Orlinick’s institution have entertained the idea of setting up a direct triage system whereby medical residents are taken out of the picture. “The emergency medicine docs would page us directly—at least during the busiest hours of the day. Eventually, the hope is to make it a 24-hour, seven-days-a-week, 365 [days-a-year process],” says Dr. Orlinick. By bringing this to the emergency medicine physicians, the intent was to send the message that hospitalists recognize ED overcrowding as an institutional issue and want to improve communication with their ED colleagues to improve patient care.

This model, devised at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, enabled communication between ED doctors and hospitalists, and reduced wait times by more than two hours when a bed was available.2 This triage and direct-admission protocol was not associated with increased mortality and resulted in improved patient and physician satisfaction. (See Figure 2 at right). Once the ED attending decides to admit a patient, direct communication is facilitated with a hospitalist. The approach includes monthly meetings between the department of medicine and the ED to continue to discuss improvements in admissions.

At Norwalk Hospital, the administration asked the hospitalist group to intervene in that throughput process. But Dr. Orlinick, also a clinical instructor of medicine at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., says they’ve hesitated out of sensitivity to their ED colleagues.

“We as a group have really struggled with that concept because [although] we feel like that is something we can do well, this is really within the purview of the emergency medicine docs,” says Dr. Orlinick. Adopting the Johns Hopkins model is a win-win solution where each specialty is providing its best skills to solve mutual issues. “What we can do well is look at the patients … on the floor[s], look at flow through the hospital systems in terms of getting testing; make sure that all that—and consults—happen in a timely manner, and that people leave the hospital when they’ve reached their goals of hospitalization,” he says. “It’s afterload as opposed to preload.”

Hospitalists see committee collaboration as important to solving the complex multidisciplinary systemic issues. Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, participates on a pneumonia task force with several hospitalists, a pulmonologist, and one of the heads of the ED. “We address the whole gamut from when patients come in to when they go through the hospital,” says Dr. Gundersen, head of the Hospital Medicine Division, University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester. “We can learn from each other as we go through the process.”

Many of the ways hospitalists and ED physicians tackle systems-related issues are new to Dr. Glasheen’s institution because the hospital medicine program was begun in 2004. It is now common to see higher-level leadership from different specialties and areas all in the same room—talking about issues of capacity, for instance. There are also many more instances of hospitalists and ED physicians sitting on the same committees. Further, “It is relatively common for our ED to call our hospitalists to say, ‘Can you help see this patient? I’m not sure what to do,’ or, ‘I’ve got this situation with this patient, this needs to be done and I need help getting that done,’ ” Dr. Glasheen says. Even though he concedes that is more of a workaround as opposed to a solution for a faulty system, it still represents ED physicians and hospitalists co-managing that workaround.

The Future

Because he “sits on both sides of the fence” between emergency medicine and hospital medicine, Dr. Gundersen thinks it is especially important for hospitalists to train in all the different areas—including emergency medicine—when they are medical students and residents.

Emergency medicine physicians Dr. Hoekstra and Benjamin Honigman, MD, professor of surgery and head of the Division of Emergency Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver, believe hospital medicine will be integral to that training. Dr. Glasheen, also the director of the longest-running internal medicine hospitalist-training program in the U.S., expects greater attention to hospitalist training. “My sense is that many hospitalists groups are in a growth phase and are trying to solve their own problems,” he says. Basically, their primary focus is staffing the hospital with good people and retaining them. He believes that once groups have been around for three to five years, they are more likely to take on bigger issues, such as hospital efficiency and capacity management.

“One of the reasons we started a hospitalist training program is that I didn’t want hospitalists to fall into the same mistakes, barriers, or issues that we’ve had in the past,” Dr. Glasheen says. He fears “this sort of continued balkanization of hospital care, where everyone silos everything out and considers such issues as throughput and ED divert as outside of their [jurisdiction]. I want to get to the place where hospitalists are looking at the whole hospital system and are justly rewarded for that either by financial incentives or time to [work on systemic issues].”

Dr. Glasheen and his team remind themselves of where their commitment resides: “This hospital is where we live—and with everything between the front door to the back door, our primary job is to make this a better place.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Burt CW, McCaig LF. Staffing, capacity, and ambulance diversion in emergency departments: United States, 2003-04. Adv Data; US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Md. Sept. 27, 2006. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad376.pdf. Last accessed June 25, 2007.

- Howell EE, Bessman ES, Rubin HR. Hospitalists and an innovative emergency department admission process. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Mar;19(3):266-268.