User login

Granular Cell Basal Cell Carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common human epithelial malignancy. There are several histologic variants, the rarest being granular cell BCC (GBCC).1 Granular cell BCC is reported most commonly in men with a mean age of 63 years. Sixty-four percent of cases develop on the face, with the remainder arising on the chest or trunk. Granular cell BCC has distinct histologic features but has no specific epidemiologic or clinical features that differentiate it from more common forms of BCC. Treatment of GBCC is identical to BCC and demonstrates similar outcomes. The presence of granular cells can make GBCC difficult to differentiate from other benign and malignant lesions that display similar granular histologic changes.1,2 Rarely, tumors that are histologically similar to human GBCC have been reported in animals.1

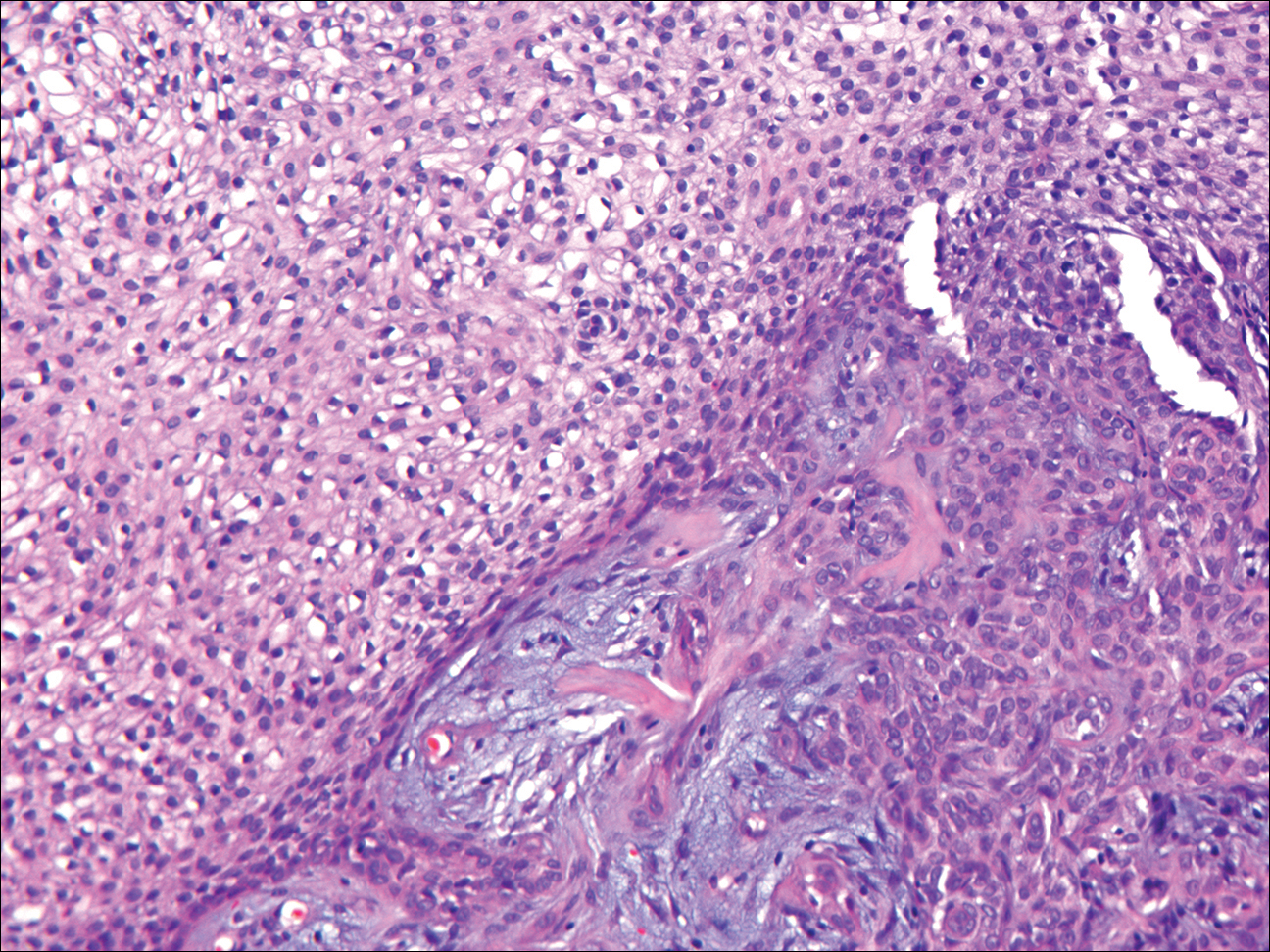

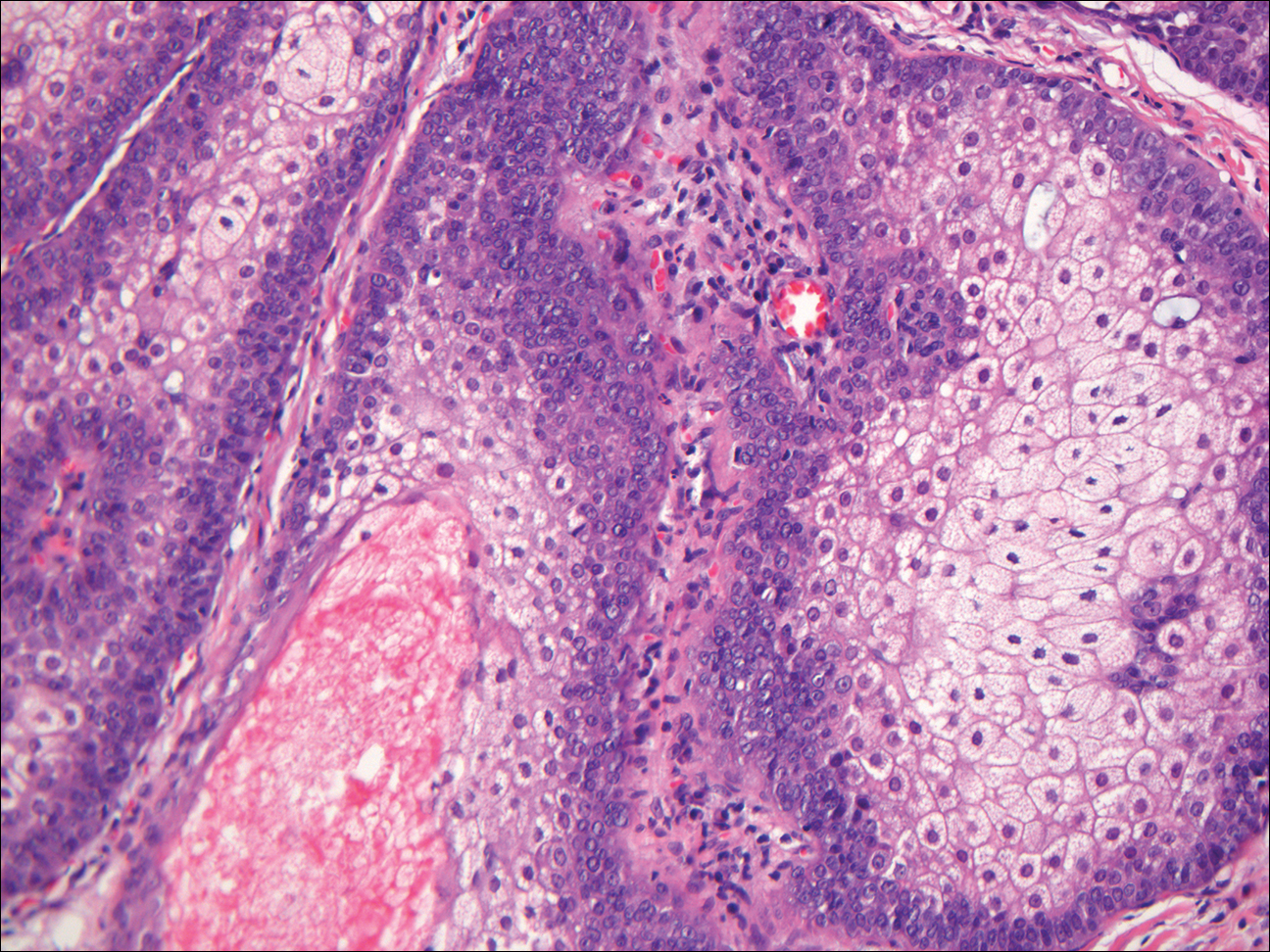

Histologically, GBCC commonly demonstrates the architecture of a nodular BCC or may extend from an existing nodular BCC (quiz images A and B). Granular cell BCC is comprised of large islands of basaloid cells extending from the epidermis with rare mitotic activity. Certain variants showing no epidermal attachments have been described,1,3 as in the current case. Classically, BCC and GBCC both demonstrate a peripheral palisade of blue basal cells; however, GBCC may lack this palisading feature in some cases. Therefore, GBCC may be comprised of granular cells only, which may be more easily confused with other tumors with granular cell differentiation. Even when GBCC retains the traditional peripheral palisade of blue basal cells, the central cells are filled with eosinophilic granules.1,2

Electron microscopy of GBCC usually reveals bundles of cytoplasmic tonofilaments and desmosomes in both granular cells and the peripherally palisaded cells. Electron microscopy imaging also demonstrates 0.1- to 0.5-µm membrane-bound lysosomelike structures. In certain reports, these structures show focal positivity for lysozymes.1,2 The etiology of the granules is unclear; however, they are thought to represent degenerative changes related to metabolic alteration and accumulation of lysosomelike structures. These lysosomelike structures have been highlighted with CD68 staining, which was negative in our case.1,2 The lesional cells in GBCC stain positively for cytokeratins, p63, and Ber-EP4, and negatively for S-100 protein, epithelial membrane antigen, and carcinoembryonic antigen. The granules in GBCC generally are positive on periodic acid–Schiff staining.1-4

The histologic differential diagnosis for GBCC includes granular cell tumor as well as other tumors that can present with granular cell changes such as ameloblastoma, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, and granular cell trichoblastoma. Granular cell ameloblastomas have histologic features and staining patterns that are identical to GBCC; however, ameloblastomas are distinguished by their location within the oral cavity. Granular cell tumors and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors stain positive for S-100 protein, and angiosarcomas stain positive for D2-40 and CD31. Leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas can be differentiated by staining with smooth muscle actin or desmin.1 Granular cell trichoblastomas can be differentiated by the follicular stem cell marker protein PHLDA1 positivity.5

Desmoplastic trichilemmoma is difficult to distinguish from BCC. These tumors are comprised of superficial lobules of basaloid cells with a perilobular hyaline mantel surrounding a central desmoplastic stroma (Figure 1). The basaloid cells in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma demonstrate clear cell change; however, granular features are not seen. The cells within the desmoplastic areas are arranged haphazardly in cords and nests and can mimic an invasive carcinoma; however, nuclear atypia and mitotic activity generally are absent in desmoplastic trichilemmoma.6

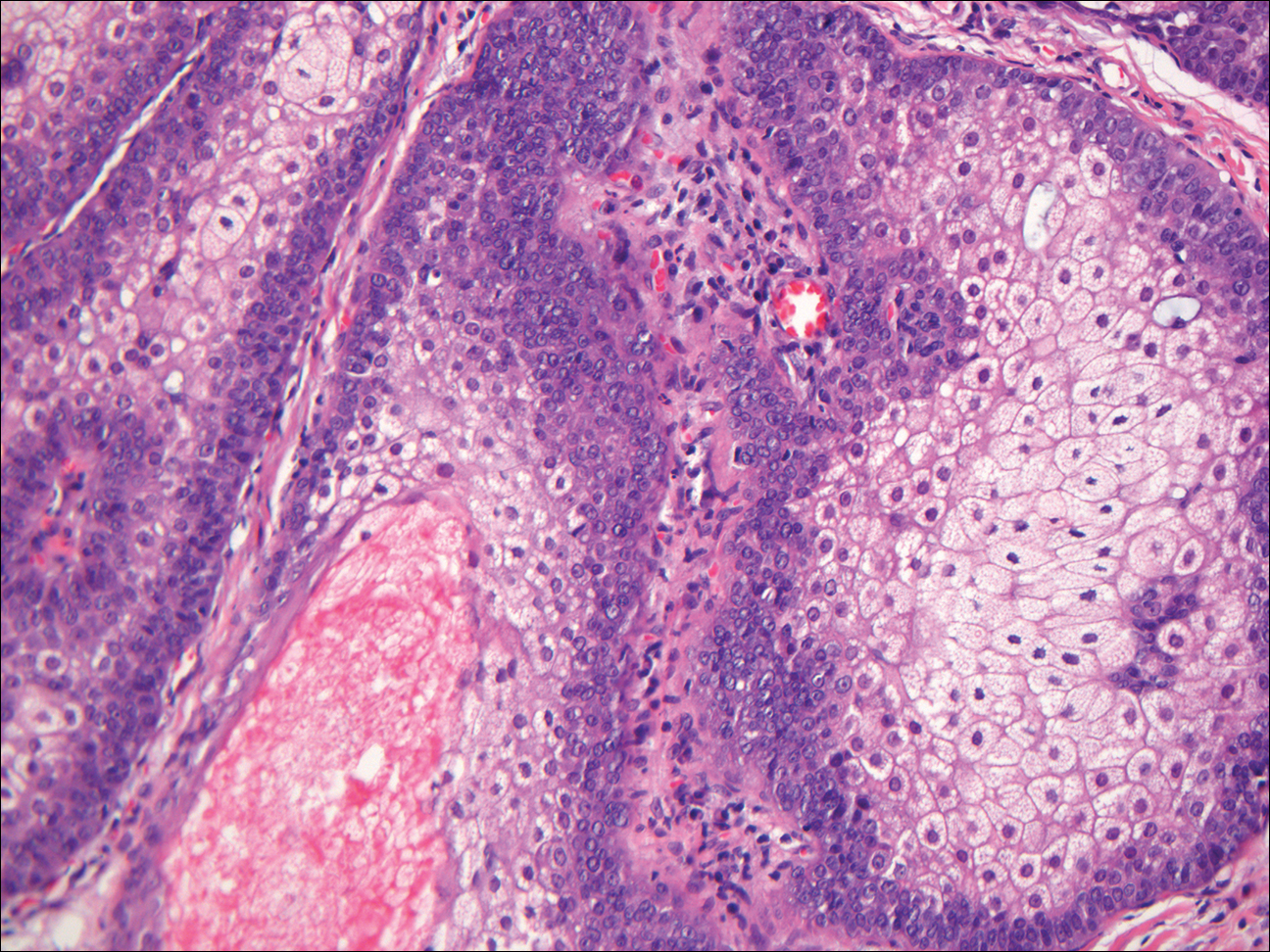

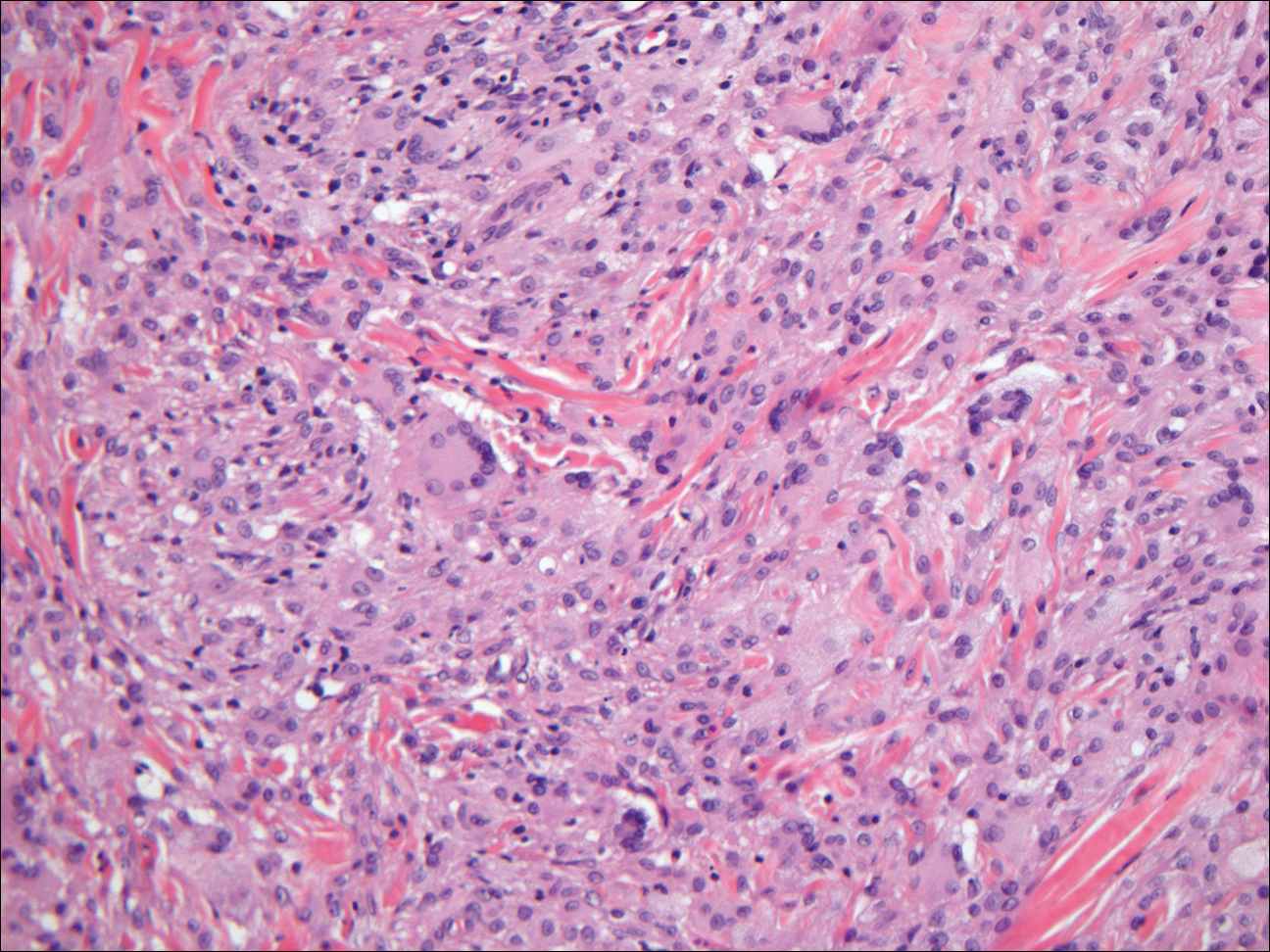

Granular cell tumors generally are poorly circumscribed dermal nodules comprised of large polygonal cells with an eosinophilic granular cytoplasm (Figure 2). The nuclei are generally small and round, and cytological atypia, necrosis, and mitotic activity are uncommon. The cells are positive for S-100 protein and neuron-specific enolase but negative for CD68. The granules are positive for periodic acid–Schiff stain and are diastase resistant. Rarely, these tumors can be malignant.7

Sebaceous adenoma is a well-circumscribed tumor comprised of lobules of characteristic mature sebocytes with bubbly or multivacuolated cytoplasm and crenated nuclei (Figure 3). There is an expansion and increased prominence of the peripherally located basaloid cells; however, in contrast to sebaceous epithelioma, less than 50% of the tumor usually is comprised of these basaloid cells.8

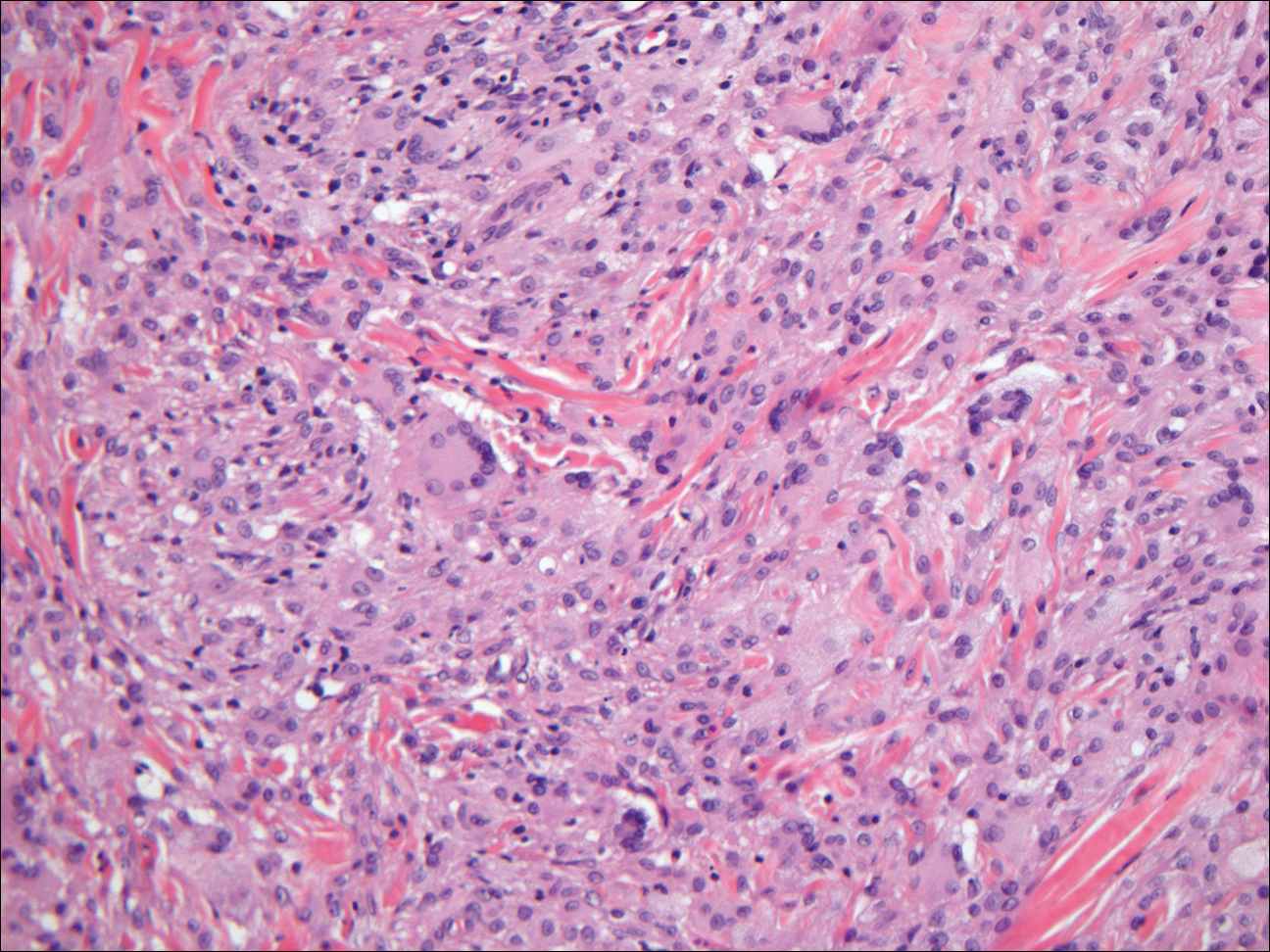

Xanthogranuloma demonstrates a dense collection of histiocytes in the dermis, commonly with Touton giant cell formation (Figure 4). The cells often have a foamy cytoplasm and cytoplasmic vacuoles are observed. The histiocytes are positive for factor XIIIa and CD68, and generally negative for S-100 protein and CD1a, which allows for differentiation from Langerhans cells.9

- Kanitakis J, Chouvet B. Granular-cell basal cell carcinoma of the skin. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:301-303.

- Dundr P, Stork J, Povysil C, et al. Granular cell basal cell carcinoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:70-72.

- Hayden AA, Shamma HN. Ber-EP4 and MNF-116 in a previously undescribed morphologic pattern of granular basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:530-532.

- Ansai S, Takayama R, Kimura T, et al. Ber-EP4 is a useful marker for follicular germinative cell differentiation of cutaneous epithelial neoplasms. J Dermatol. 2012;39:688-692.

- Battistella M, Peltre B, Cribier B. PHLDA1, a follicular stem cell marker, differentiates clear-cell/granular-cell trichoblastoma and clear-cell/granular cell basal cell carcinoma: a case-control study, with first description of granular-cell trichoblastoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:643-650.

- Tellechea O, Reis JP, Baptista AP. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:107-114.

- Battistella M, Cribier B, Feugeas JP, et al. Vascular invasion and other invasive features in granular cell tumours of the skin: a multicentre study of 119 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:19-25.

- Shalin SC, Lyle S, Calonje E, et al. Sebaceous neoplasia and the Muir-Torre syndrome: important connections with clinical implications. Histopathology. 2010;56:133-147.

- Janssen D, Harms D. Juvenile xanthogranuloma in childhood and adolescence: a clinicopathologic study of 129 patients from the kiel pediatric tumor registry. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:21-28.

Granular Cell Basal Cell Carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common human epithelial malignancy. There are several histologic variants, the rarest being granular cell BCC (GBCC).1 Granular cell BCC is reported most commonly in men with a mean age of 63 years. Sixty-four percent of cases develop on the face, with the remainder arising on the chest or trunk. Granular cell BCC has distinct histologic features but has no specific epidemiologic or clinical features that differentiate it from more common forms of BCC. Treatment of GBCC is identical to BCC and demonstrates similar outcomes. The presence of granular cells can make GBCC difficult to differentiate from other benign and malignant lesions that display similar granular histologic changes.1,2 Rarely, tumors that are histologically similar to human GBCC have been reported in animals.1

Histologically, GBCC commonly demonstrates the architecture of a nodular BCC or may extend from an existing nodular BCC (quiz images A and B). Granular cell BCC is comprised of large islands of basaloid cells extending from the epidermis with rare mitotic activity. Certain variants showing no epidermal attachments have been described,1,3 as in the current case. Classically, BCC and GBCC both demonstrate a peripheral palisade of blue basal cells; however, GBCC may lack this palisading feature in some cases. Therefore, GBCC may be comprised of granular cells only, which may be more easily confused with other tumors with granular cell differentiation. Even when GBCC retains the traditional peripheral palisade of blue basal cells, the central cells are filled with eosinophilic granules.1,2

Electron microscopy of GBCC usually reveals bundles of cytoplasmic tonofilaments and desmosomes in both granular cells and the peripherally palisaded cells. Electron microscopy imaging also demonstrates 0.1- to 0.5-µm membrane-bound lysosomelike structures. In certain reports, these structures show focal positivity for lysozymes.1,2 The etiology of the granules is unclear; however, they are thought to represent degenerative changes related to metabolic alteration and accumulation of lysosomelike structures. These lysosomelike structures have been highlighted with CD68 staining, which was negative in our case.1,2 The lesional cells in GBCC stain positively for cytokeratins, p63, and Ber-EP4, and negatively for S-100 protein, epithelial membrane antigen, and carcinoembryonic antigen. The granules in GBCC generally are positive on periodic acid–Schiff staining.1-4

The histologic differential diagnosis for GBCC includes granular cell tumor as well as other tumors that can present with granular cell changes such as ameloblastoma, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, and granular cell trichoblastoma. Granular cell ameloblastomas have histologic features and staining patterns that are identical to GBCC; however, ameloblastomas are distinguished by their location within the oral cavity. Granular cell tumors and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors stain positive for S-100 protein, and angiosarcomas stain positive for D2-40 and CD31. Leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas can be differentiated by staining with smooth muscle actin or desmin.1 Granular cell trichoblastomas can be differentiated by the follicular stem cell marker protein PHLDA1 positivity.5

Desmoplastic trichilemmoma is difficult to distinguish from BCC. These tumors are comprised of superficial lobules of basaloid cells with a perilobular hyaline mantel surrounding a central desmoplastic stroma (Figure 1). The basaloid cells in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma demonstrate clear cell change; however, granular features are not seen. The cells within the desmoplastic areas are arranged haphazardly in cords and nests and can mimic an invasive carcinoma; however, nuclear atypia and mitotic activity generally are absent in desmoplastic trichilemmoma.6

Granular cell tumors generally are poorly circumscribed dermal nodules comprised of large polygonal cells with an eosinophilic granular cytoplasm (Figure 2). The nuclei are generally small and round, and cytological atypia, necrosis, and mitotic activity are uncommon. The cells are positive for S-100 protein and neuron-specific enolase but negative for CD68. The granules are positive for periodic acid–Schiff stain and are diastase resistant. Rarely, these tumors can be malignant.7

Sebaceous adenoma is a well-circumscribed tumor comprised of lobules of characteristic mature sebocytes with bubbly or multivacuolated cytoplasm and crenated nuclei (Figure 3). There is an expansion and increased prominence of the peripherally located basaloid cells; however, in contrast to sebaceous epithelioma, less than 50% of the tumor usually is comprised of these basaloid cells.8

Xanthogranuloma demonstrates a dense collection of histiocytes in the dermis, commonly with Touton giant cell formation (Figure 4). The cells often have a foamy cytoplasm and cytoplasmic vacuoles are observed. The histiocytes are positive for factor XIIIa and CD68, and generally negative for S-100 protein and CD1a, which allows for differentiation from Langerhans cells.9

Granular Cell Basal Cell Carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common human epithelial malignancy. There are several histologic variants, the rarest being granular cell BCC (GBCC).1 Granular cell BCC is reported most commonly in men with a mean age of 63 years. Sixty-four percent of cases develop on the face, with the remainder arising on the chest or trunk. Granular cell BCC has distinct histologic features but has no specific epidemiologic or clinical features that differentiate it from more common forms of BCC. Treatment of GBCC is identical to BCC and demonstrates similar outcomes. The presence of granular cells can make GBCC difficult to differentiate from other benign and malignant lesions that display similar granular histologic changes.1,2 Rarely, tumors that are histologically similar to human GBCC have been reported in animals.1

Histologically, GBCC commonly demonstrates the architecture of a nodular BCC or may extend from an existing nodular BCC (quiz images A and B). Granular cell BCC is comprised of large islands of basaloid cells extending from the epidermis with rare mitotic activity. Certain variants showing no epidermal attachments have been described,1,3 as in the current case. Classically, BCC and GBCC both demonstrate a peripheral palisade of blue basal cells; however, GBCC may lack this palisading feature in some cases. Therefore, GBCC may be comprised of granular cells only, which may be more easily confused with other tumors with granular cell differentiation. Even when GBCC retains the traditional peripheral palisade of blue basal cells, the central cells are filled with eosinophilic granules.1,2

Electron microscopy of GBCC usually reveals bundles of cytoplasmic tonofilaments and desmosomes in both granular cells and the peripherally palisaded cells. Electron microscopy imaging also demonstrates 0.1- to 0.5-µm membrane-bound lysosomelike structures. In certain reports, these structures show focal positivity for lysozymes.1,2 The etiology of the granules is unclear; however, they are thought to represent degenerative changes related to metabolic alteration and accumulation of lysosomelike structures. These lysosomelike structures have been highlighted with CD68 staining, which was negative in our case.1,2 The lesional cells in GBCC stain positively for cytokeratins, p63, and Ber-EP4, and negatively for S-100 protein, epithelial membrane antigen, and carcinoembryonic antigen. The granules in GBCC generally are positive on periodic acid–Schiff staining.1-4

The histologic differential diagnosis for GBCC includes granular cell tumor as well as other tumors that can present with granular cell changes such as ameloblastoma, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, and granular cell trichoblastoma. Granular cell ameloblastomas have histologic features and staining patterns that are identical to GBCC; however, ameloblastomas are distinguished by their location within the oral cavity. Granular cell tumors and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors stain positive for S-100 protein, and angiosarcomas stain positive for D2-40 and CD31. Leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas can be differentiated by staining with smooth muscle actin or desmin.1 Granular cell trichoblastomas can be differentiated by the follicular stem cell marker protein PHLDA1 positivity.5

Desmoplastic trichilemmoma is difficult to distinguish from BCC. These tumors are comprised of superficial lobules of basaloid cells with a perilobular hyaline mantel surrounding a central desmoplastic stroma (Figure 1). The basaloid cells in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma demonstrate clear cell change; however, granular features are not seen. The cells within the desmoplastic areas are arranged haphazardly in cords and nests and can mimic an invasive carcinoma; however, nuclear atypia and mitotic activity generally are absent in desmoplastic trichilemmoma.6

Granular cell tumors generally are poorly circumscribed dermal nodules comprised of large polygonal cells with an eosinophilic granular cytoplasm (Figure 2). The nuclei are generally small and round, and cytological atypia, necrosis, and mitotic activity are uncommon. The cells are positive for S-100 protein and neuron-specific enolase but negative for CD68. The granules are positive for periodic acid–Schiff stain and are diastase resistant. Rarely, these tumors can be malignant.7

Sebaceous adenoma is a well-circumscribed tumor comprised of lobules of characteristic mature sebocytes with bubbly or multivacuolated cytoplasm and crenated nuclei (Figure 3). There is an expansion and increased prominence of the peripherally located basaloid cells; however, in contrast to sebaceous epithelioma, less than 50% of the tumor usually is comprised of these basaloid cells.8

Xanthogranuloma demonstrates a dense collection of histiocytes in the dermis, commonly with Touton giant cell formation (Figure 4). The cells often have a foamy cytoplasm and cytoplasmic vacuoles are observed. The histiocytes are positive for factor XIIIa and CD68, and generally negative for S-100 protein and CD1a, which allows for differentiation from Langerhans cells.9

- Kanitakis J, Chouvet B. Granular-cell basal cell carcinoma of the skin. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:301-303.

- Dundr P, Stork J, Povysil C, et al. Granular cell basal cell carcinoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:70-72.

- Hayden AA, Shamma HN. Ber-EP4 and MNF-116 in a previously undescribed morphologic pattern of granular basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:530-532.

- Ansai S, Takayama R, Kimura T, et al. Ber-EP4 is a useful marker for follicular germinative cell differentiation of cutaneous epithelial neoplasms. J Dermatol. 2012;39:688-692.

- Battistella M, Peltre B, Cribier B. PHLDA1, a follicular stem cell marker, differentiates clear-cell/granular-cell trichoblastoma and clear-cell/granular cell basal cell carcinoma: a case-control study, with first description of granular-cell trichoblastoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:643-650.

- Tellechea O, Reis JP, Baptista AP. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:107-114.

- Battistella M, Cribier B, Feugeas JP, et al. Vascular invasion and other invasive features in granular cell tumours of the skin: a multicentre study of 119 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:19-25.

- Shalin SC, Lyle S, Calonje E, et al. Sebaceous neoplasia and the Muir-Torre syndrome: important connections with clinical implications. Histopathology. 2010;56:133-147.

- Janssen D, Harms D. Juvenile xanthogranuloma in childhood and adolescence: a clinicopathologic study of 129 patients from the kiel pediatric tumor registry. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:21-28.

- Kanitakis J, Chouvet B. Granular-cell basal cell carcinoma of the skin. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:301-303.

- Dundr P, Stork J, Povysil C, et al. Granular cell basal cell carcinoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:70-72.

- Hayden AA, Shamma HN. Ber-EP4 and MNF-116 in a previously undescribed morphologic pattern of granular basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:530-532.

- Ansai S, Takayama R, Kimura T, et al. Ber-EP4 is a useful marker for follicular germinative cell differentiation of cutaneous epithelial neoplasms. J Dermatol. 2012;39:688-692.

- Battistella M, Peltre B, Cribier B. PHLDA1, a follicular stem cell marker, differentiates clear-cell/granular-cell trichoblastoma and clear-cell/granular cell basal cell carcinoma: a case-control study, with first description of granular-cell trichoblastoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:643-650.

- Tellechea O, Reis JP, Baptista AP. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:107-114.

- Battistella M, Cribier B, Feugeas JP, et al. Vascular invasion and other invasive features in granular cell tumours of the skin: a multicentre study of 119 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:19-25.

- Shalin SC, Lyle S, Calonje E, et al. Sebaceous neoplasia and the Muir-Torre syndrome: important connections with clinical implications. Histopathology. 2010;56:133-147.

- Janssen D, Harms D. Juvenile xanthogranuloma in childhood and adolescence: a clinicopathologic study of 129 patients from the kiel pediatric tumor registry. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:21-28.

The best diagnosis is:

a. desmoplastic trichilemmoma

b. granular cell basal cell carcinoma

c. granular cell tumor

d. sebaceous adenoma

e. xanthogranuloma

Continue to the next page for the diagnosis >>