User login

BOSTON – If donors can’t get to the apheresis center, bring the apheresis center to the donors.

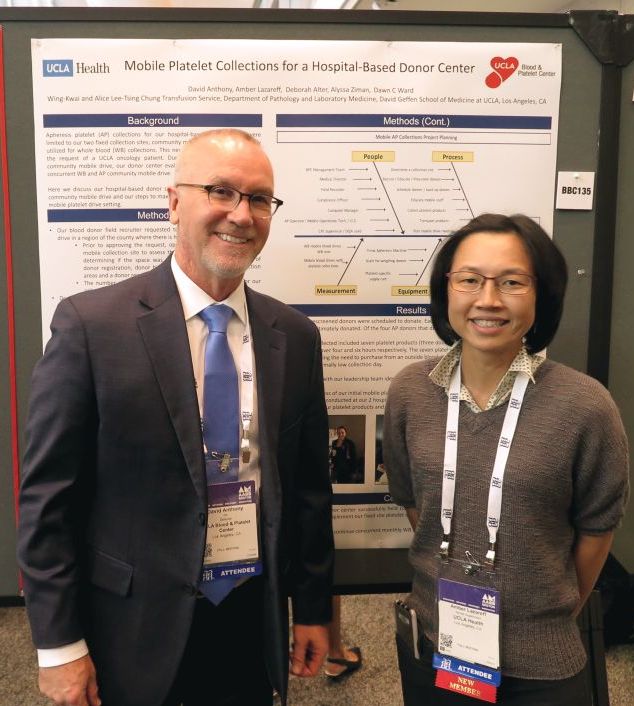

Responding to the request of a patient with cancer, David Anthony, Amber Lazareff, RN, and their colleagues at the University of California at Los Angeles Blood and Platelet Center explored adding mobile apheresis units to their existing community blood drives. They found that, with careful planning and coordination, they could augment their supply of vital blood products and introduce potential new donors to the idea of apheresis donations at the hospital.

“There was a needs drive for an oncology patient at UCLA. She wanted to bring in donors and had her whole community behind her, and we thought well, she’s an oncology patient and she uses platelets, and we had talked about doing platelets out in the field rather than just at fixed sites, and we thought that this would be a good chance to try it,” Mr. Anthony said in an interview at AABB 2018, the annual meeting of the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

Until the mobile unit was established, apheresis platelet collections for the hospital-based donor center were limited to two fixed collection sites, with mobile units used only for collection of whole blood.

To see whether concurrent whole blood and platelet community drives were practical, the center’s blood donor field recruiter requested to schedule a community drive in a region of the county where potential donors had expressed a high level of interest in apheresis platelet donations.

Operations staff visited the site to assess its suitability, including appropriate space for donor registration and history taking, separate areas for whole blood and apheresis donations, and a donor recovery area. The assessment included ensuring that there were suitable electrical outlets, space, and support for apheresis machines.

“Over about 2 weeks we discussed with our medical directors, [infusion technicians], and our mobile people what we would need to do it. The recruiter out in the field was able to go to a high school drive out in that area, recruit donors, and get [platelet] precounts from them so that we could find out who was a good candidate,” Mr. Anthony said.

Once they had platelet counts from potential apheresis donors, 10 donors were prescreened based on their eligibility to donate multiple products, history of donations and red blood cell loss, and, for women who had previously had more than one pregnancy, favorable HLA test results.

Four of the prescreened donors were scheduled to donate platelets, and the time slot also included two backup donors, one of whom ultimately donated platelets. Of the four apheresis donors, three were first-time platelet donors.

The first drive collected seven platelet products, including three double products and one single product.

The donated products resulted in about a $3,000 cost savings by obviating the need for purchasing products from an outside supplier, and bolstered the blood bank’s inventory on a normally low collection day, the authors reported.

“We’ve had two more apheresis drives since then, and we’ll have another one in 3 weeks,” Mr. Anthony said.

He acknowledged that it is more challenging to recruit, educate, and ideally retain donors in the field than in the brick-and-mortar hospital setting.

“We have to make sure that they’re going to show up if we’re going to make the effort to take a machine out there, whereas at our centers, we have regular donors who come in every 2 weeks, it’s easy for them to make an appointment, and they know where we are,” he said.

The center plans to continue concurrent monthly whole blood and platelet collection drives, he added.

The pilot program was internally funded. The authors reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Anthony D et al., AABB 2018, Poster BBC 135.

BOSTON – If donors can’t get to the apheresis center, bring the apheresis center to the donors.

Responding to the request of a patient with cancer, David Anthony, Amber Lazareff, RN, and their colleagues at the University of California at Los Angeles Blood and Platelet Center explored adding mobile apheresis units to their existing community blood drives. They found that, with careful planning and coordination, they could augment their supply of vital blood products and introduce potential new donors to the idea of apheresis donations at the hospital.

“There was a needs drive for an oncology patient at UCLA. She wanted to bring in donors and had her whole community behind her, and we thought well, she’s an oncology patient and she uses platelets, and we had talked about doing platelets out in the field rather than just at fixed sites, and we thought that this would be a good chance to try it,” Mr. Anthony said in an interview at AABB 2018, the annual meeting of the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

Until the mobile unit was established, apheresis platelet collections for the hospital-based donor center were limited to two fixed collection sites, with mobile units used only for collection of whole blood.

To see whether concurrent whole blood and platelet community drives were practical, the center’s blood donor field recruiter requested to schedule a community drive in a region of the county where potential donors had expressed a high level of interest in apheresis platelet donations.

Operations staff visited the site to assess its suitability, including appropriate space for donor registration and history taking, separate areas for whole blood and apheresis donations, and a donor recovery area. The assessment included ensuring that there were suitable electrical outlets, space, and support for apheresis machines.

“Over about 2 weeks we discussed with our medical directors, [infusion technicians], and our mobile people what we would need to do it. The recruiter out in the field was able to go to a high school drive out in that area, recruit donors, and get [platelet] precounts from them so that we could find out who was a good candidate,” Mr. Anthony said.

Once they had platelet counts from potential apheresis donors, 10 donors were prescreened based on their eligibility to donate multiple products, history of donations and red blood cell loss, and, for women who had previously had more than one pregnancy, favorable HLA test results.

Four of the prescreened donors were scheduled to donate platelets, and the time slot also included two backup donors, one of whom ultimately donated platelets. Of the four apheresis donors, three were first-time platelet donors.

The first drive collected seven platelet products, including three double products and one single product.

The donated products resulted in about a $3,000 cost savings by obviating the need for purchasing products from an outside supplier, and bolstered the blood bank’s inventory on a normally low collection day, the authors reported.

“We’ve had two more apheresis drives since then, and we’ll have another one in 3 weeks,” Mr. Anthony said.

He acknowledged that it is more challenging to recruit, educate, and ideally retain donors in the field than in the brick-and-mortar hospital setting.

“We have to make sure that they’re going to show up if we’re going to make the effort to take a machine out there, whereas at our centers, we have regular donors who come in every 2 weeks, it’s easy for them to make an appointment, and they know where we are,” he said.

The center plans to continue concurrent monthly whole blood and platelet collection drives, he added.

The pilot program was internally funded. The authors reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Anthony D et al., AABB 2018, Poster BBC 135.

BOSTON – If donors can’t get to the apheresis center, bring the apheresis center to the donors.

Responding to the request of a patient with cancer, David Anthony, Amber Lazareff, RN, and their colleagues at the University of California at Los Angeles Blood and Platelet Center explored adding mobile apheresis units to their existing community blood drives. They found that, with careful planning and coordination, they could augment their supply of vital blood products and introduce potential new donors to the idea of apheresis donations at the hospital.

“There was a needs drive for an oncology patient at UCLA. She wanted to bring in donors and had her whole community behind her, and we thought well, she’s an oncology patient and she uses platelets, and we had talked about doing platelets out in the field rather than just at fixed sites, and we thought that this would be a good chance to try it,” Mr. Anthony said in an interview at AABB 2018, the annual meeting of the group formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

Until the mobile unit was established, apheresis platelet collections for the hospital-based donor center were limited to two fixed collection sites, with mobile units used only for collection of whole blood.

To see whether concurrent whole blood and platelet community drives were practical, the center’s blood donor field recruiter requested to schedule a community drive in a region of the county where potential donors had expressed a high level of interest in apheresis platelet donations.

Operations staff visited the site to assess its suitability, including appropriate space for donor registration and history taking, separate areas for whole blood and apheresis donations, and a donor recovery area. The assessment included ensuring that there were suitable electrical outlets, space, and support for apheresis machines.

“Over about 2 weeks we discussed with our medical directors, [infusion technicians], and our mobile people what we would need to do it. The recruiter out in the field was able to go to a high school drive out in that area, recruit donors, and get [platelet] precounts from them so that we could find out who was a good candidate,” Mr. Anthony said.

Once they had platelet counts from potential apheresis donors, 10 donors were prescreened based on their eligibility to donate multiple products, history of donations and red blood cell loss, and, for women who had previously had more than one pregnancy, favorable HLA test results.

Four of the prescreened donors were scheduled to donate platelets, and the time slot also included two backup donors, one of whom ultimately donated platelets. Of the four apheresis donors, three were first-time platelet donors.

The first drive collected seven platelet products, including three double products and one single product.

The donated products resulted in about a $3,000 cost savings by obviating the need for purchasing products from an outside supplier, and bolstered the blood bank’s inventory on a normally low collection day, the authors reported.

“We’ve had two more apheresis drives since then, and we’ll have another one in 3 weeks,” Mr. Anthony said.

He acknowledged that it is more challenging to recruit, educate, and ideally retain donors in the field than in the brick-and-mortar hospital setting.

“We have to make sure that they’re going to show up if we’re going to make the effort to take a machine out there, whereas at our centers, we have regular donors who come in every 2 weeks, it’s easy for them to make an appointment, and they know where we are,” he said.

The center plans to continue concurrent monthly whole blood and platelet collection drives, he added.

The pilot program was internally funded. The authors reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Anthony D et al., AABB 2018, Poster BBC 135.

AT AABB 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Field-based collection of platelet products saved costs and augmented the hospital’s supply on a normally low collection day.

Study details: Pilot program testing apheresis platelet donations during community blood drives.

Disclosures: The pilot program was internally funded. The authors reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Anthony D et al. AABB 2018, Poster BBC 135.