User login

Roughly 6 months ago, a primary care physician referred a patient to our clinic for an assessment for opioid use disorder and a recommendation for treatment. The patient estimated, likely underestimated, his daily heroin use to five bags and dropped positive, in addition to heroin, for benzodiazepines, amphetamines, and cannabis. He was in a profession in which public safety was a critical concern, and he refused to notify his employer’s employee assistance program. He also declined to voluntarily admit himself for detox and treatment at the local, fully accredited addiction program, which was affiliated with a major university medical center. Instead, after an Internet search, the patient opted for an opioid treatment center featuring massage therapy, acupuncture, a stable, a sweat lodge – and a magnificent view of the Pacific Ocean.

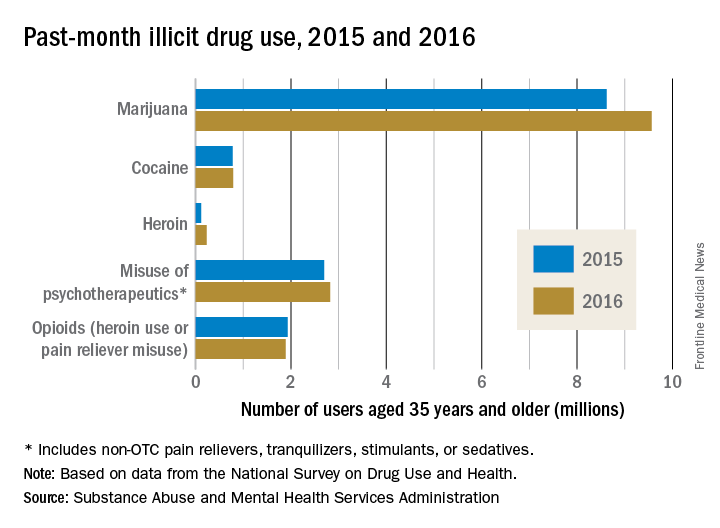

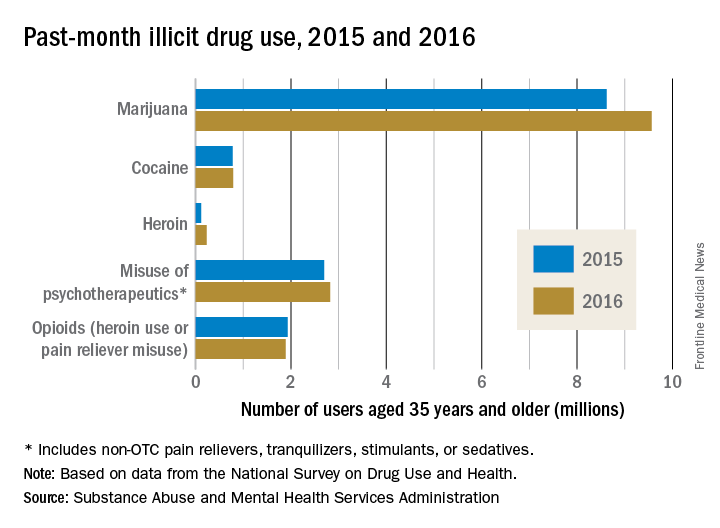

Mental health professionals and lay people alike are aware of the “opioid crisis” – the derailment of lives, the devastation to communities, the death toll. But despite proposals to increase research funding, policies aimed at tightening the prescribing of opioids, and pledges to ramp up interdiction of heroin traffic, there is often an ignorance and confusion regarding the best, evidence-based approaches to getting patients with substance use disorders clean and keeping them clean.

Unfortunately, as with any crisis, there will be opportunists preying on vulnerable patients and their families. And this travesty has reportedly escalated, as outpatient treatment centers take advantage of laws guaranteeing mental health parity and insurance companies paying out tens of thousands of dollars for residential and outpatient opioid treatment. The potential for significant profit is plainly illustrated by the influx of private equity firms, such as Bain Capital, that are investing heavily in treatment centers.

Reports of malfeasance and misconduct, by owners, operators, staff, and others connected with the industry are beginning to get the attention of authorities. There have been reports of outpatient treatment centers that spend lavishly on furnishing, on BMWs and signed art, yet are understaffed, leading to inadequate one-on-one counseling and even sexual transgressions between residents. There are centers that have been investigated for insurance fraud, such as illegally waiving a copay or a deductible or for charging up to $5,000 for a simple urine five drug screen, often multiple times a day. And there is evidence of “junkie hunters” who cruise for people with addictions and brokers who provide such people with fake addresses in order to qualify for insurance plans with excellent benefits for addiction treatment.

Probably the best means to find a suitable outpatient treatment center is by way of a local, experienced, and respected chemical dependency counselor or physician certified in addiction medicine. If people with substance use disorders and their families want to independently conduct a search, as a good rule of thumb, they should be advised to consider programs affiliated with major medical centers and hospitals or outpatient treatment centers that have been established in good standing for years, in contrast to the rash of pop-up, for-profit programs. Of equal, or even greater importance, is that the prospective center ought to be accredited by a national organization, for example, The Joint Commission, and its staff ought to be licensed and credentialed as well.

In addition, there is merit if the staff has been educated, trained, and supervised under the direction of a respected institution. Needless to add, an outpatient treatment center must use evidence-based practices as the bedrock of treatment; this includes pharmacotherapies such as Suboxone and naltrexone (Vivitrol), and behavioral therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, contingency management, and motivational enhancement. To date, massage and essential oils might be relaxing and pleasurable, but they are not considered accepted standard of care.

It is crucial, too, that an outpatient treatment center have both the resources to reliably handle acute medical detox, which can be a potentially life-threatening emergency, and the medical personnel who can assess and treat such medical conditions as hypertension as well as psychiatric illnesses such as bipolar and generalized anxiety disorders. A prospective patient also should inquire whether any of the staff has been the subject of disciplinary action by a licensing board or whether the center has been investigated by the state or a national accrediting organization.

Because addiction so often has facets rooted in the family system, and recovery so often depends on family support, an outpatient treatment center should provide a structured family program integrated into the patient’s treatment and emphasize the importance of continued family involvement after discharge.

Lastly, the best treatment centers often regularly update a patient’s local therapist and physician, spell out the elements of successful aftercare (12-step programs, and so on), and provide amenities, such as calls to a recently discharged patient and an alumni support network.

Dr. Marseille is a psychiatrist who works on the staff of a clinic in Wheaton, Ill. His special interests include adolescent and addiction medicine, eating disorders, trauma, bipolar disorder, and the psychiatric manifestations of acute and chronic medical conditions.

This article was updated 12/15/17.

Roughly 6 months ago, a primary care physician referred a patient to our clinic for an assessment for opioid use disorder and a recommendation for treatment. The patient estimated, likely underestimated, his daily heroin use to five bags and dropped positive, in addition to heroin, for benzodiazepines, amphetamines, and cannabis. He was in a profession in which public safety was a critical concern, and he refused to notify his employer’s employee assistance program. He also declined to voluntarily admit himself for detox and treatment at the local, fully accredited addiction program, which was affiliated with a major university medical center. Instead, after an Internet search, the patient opted for an opioid treatment center featuring massage therapy, acupuncture, a stable, a sweat lodge – and a magnificent view of the Pacific Ocean.

Mental health professionals and lay people alike are aware of the “opioid crisis” – the derailment of lives, the devastation to communities, the death toll. But despite proposals to increase research funding, policies aimed at tightening the prescribing of opioids, and pledges to ramp up interdiction of heroin traffic, there is often an ignorance and confusion regarding the best, evidence-based approaches to getting patients with substance use disorders clean and keeping them clean.

Unfortunately, as with any crisis, there will be opportunists preying on vulnerable patients and their families. And this travesty has reportedly escalated, as outpatient treatment centers take advantage of laws guaranteeing mental health parity and insurance companies paying out tens of thousands of dollars for residential and outpatient opioid treatment. The potential for significant profit is plainly illustrated by the influx of private equity firms, such as Bain Capital, that are investing heavily in treatment centers.

Reports of malfeasance and misconduct, by owners, operators, staff, and others connected with the industry are beginning to get the attention of authorities. There have been reports of outpatient treatment centers that spend lavishly on furnishing, on BMWs and signed art, yet are understaffed, leading to inadequate one-on-one counseling and even sexual transgressions between residents. There are centers that have been investigated for insurance fraud, such as illegally waiving a copay or a deductible or for charging up to $5,000 for a simple urine five drug screen, often multiple times a day. And there is evidence of “junkie hunters” who cruise for people with addictions and brokers who provide such people with fake addresses in order to qualify for insurance plans with excellent benefits for addiction treatment.

Probably the best means to find a suitable outpatient treatment center is by way of a local, experienced, and respected chemical dependency counselor or physician certified in addiction medicine. If people with substance use disorders and their families want to independently conduct a search, as a good rule of thumb, they should be advised to consider programs affiliated with major medical centers and hospitals or outpatient treatment centers that have been established in good standing for years, in contrast to the rash of pop-up, for-profit programs. Of equal, or even greater importance, is that the prospective center ought to be accredited by a national organization, for example, The Joint Commission, and its staff ought to be licensed and credentialed as well.

In addition, there is merit if the staff has been educated, trained, and supervised under the direction of a respected institution. Needless to add, an outpatient treatment center must use evidence-based practices as the bedrock of treatment; this includes pharmacotherapies such as Suboxone and naltrexone (Vivitrol), and behavioral therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, contingency management, and motivational enhancement. To date, massage and essential oils might be relaxing and pleasurable, but they are not considered accepted standard of care.

It is crucial, too, that an outpatient treatment center have both the resources to reliably handle acute medical detox, which can be a potentially life-threatening emergency, and the medical personnel who can assess and treat such medical conditions as hypertension as well as psychiatric illnesses such as bipolar and generalized anxiety disorders. A prospective patient also should inquire whether any of the staff has been the subject of disciplinary action by a licensing board or whether the center has been investigated by the state or a national accrediting organization.

Because addiction so often has facets rooted in the family system, and recovery so often depends on family support, an outpatient treatment center should provide a structured family program integrated into the patient’s treatment and emphasize the importance of continued family involvement after discharge.

Lastly, the best treatment centers often regularly update a patient’s local therapist and physician, spell out the elements of successful aftercare (12-step programs, and so on), and provide amenities, such as calls to a recently discharged patient and an alumni support network.

Dr. Marseille is a psychiatrist who works on the staff of a clinic in Wheaton, Ill. His special interests include adolescent and addiction medicine, eating disorders, trauma, bipolar disorder, and the psychiatric manifestations of acute and chronic medical conditions.

This article was updated 12/15/17.

Roughly 6 months ago, a primary care physician referred a patient to our clinic for an assessment for opioid use disorder and a recommendation for treatment. The patient estimated, likely underestimated, his daily heroin use to five bags and dropped positive, in addition to heroin, for benzodiazepines, amphetamines, and cannabis. He was in a profession in which public safety was a critical concern, and he refused to notify his employer’s employee assistance program. He also declined to voluntarily admit himself for detox and treatment at the local, fully accredited addiction program, which was affiliated with a major university medical center. Instead, after an Internet search, the patient opted for an opioid treatment center featuring massage therapy, acupuncture, a stable, a sweat lodge – and a magnificent view of the Pacific Ocean.

Mental health professionals and lay people alike are aware of the “opioid crisis” – the derailment of lives, the devastation to communities, the death toll. But despite proposals to increase research funding, policies aimed at tightening the prescribing of opioids, and pledges to ramp up interdiction of heroin traffic, there is often an ignorance and confusion regarding the best, evidence-based approaches to getting patients with substance use disorders clean and keeping them clean.

Unfortunately, as with any crisis, there will be opportunists preying on vulnerable patients and their families. And this travesty has reportedly escalated, as outpatient treatment centers take advantage of laws guaranteeing mental health parity and insurance companies paying out tens of thousands of dollars for residential and outpatient opioid treatment. The potential for significant profit is plainly illustrated by the influx of private equity firms, such as Bain Capital, that are investing heavily in treatment centers.

Reports of malfeasance and misconduct, by owners, operators, staff, and others connected with the industry are beginning to get the attention of authorities. There have been reports of outpatient treatment centers that spend lavishly on furnishing, on BMWs and signed art, yet are understaffed, leading to inadequate one-on-one counseling and even sexual transgressions between residents. There are centers that have been investigated for insurance fraud, such as illegally waiving a copay or a deductible or for charging up to $5,000 for a simple urine five drug screen, often multiple times a day. And there is evidence of “junkie hunters” who cruise for people with addictions and brokers who provide such people with fake addresses in order to qualify for insurance plans with excellent benefits for addiction treatment.

Probably the best means to find a suitable outpatient treatment center is by way of a local, experienced, and respected chemical dependency counselor or physician certified in addiction medicine. If people with substance use disorders and their families want to independently conduct a search, as a good rule of thumb, they should be advised to consider programs affiliated with major medical centers and hospitals or outpatient treatment centers that have been established in good standing for years, in contrast to the rash of pop-up, for-profit programs. Of equal, or even greater importance, is that the prospective center ought to be accredited by a national organization, for example, The Joint Commission, and its staff ought to be licensed and credentialed as well.

In addition, there is merit if the staff has been educated, trained, and supervised under the direction of a respected institution. Needless to add, an outpatient treatment center must use evidence-based practices as the bedrock of treatment; this includes pharmacotherapies such as Suboxone and naltrexone (Vivitrol), and behavioral therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, contingency management, and motivational enhancement. To date, massage and essential oils might be relaxing and pleasurable, but they are not considered accepted standard of care.

It is crucial, too, that an outpatient treatment center have both the resources to reliably handle acute medical detox, which can be a potentially life-threatening emergency, and the medical personnel who can assess and treat such medical conditions as hypertension as well as psychiatric illnesses such as bipolar and generalized anxiety disorders. A prospective patient also should inquire whether any of the staff has been the subject of disciplinary action by a licensing board or whether the center has been investigated by the state or a national accrediting organization.

Because addiction so often has facets rooted in the family system, and recovery so often depends on family support, an outpatient treatment center should provide a structured family program integrated into the patient’s treatment and emphasize the importance of continued family involvement after discharge.

Lastly, the best treatment centers often regularly update a patient’s local therapist and physician, spell out the elements of successful aftercare (12-step programs, and so on), and provide amenities, such as calls to a recently discharged patient and an alumni support network.

Dr. Marseille is a psychiatrist who works on the staff of a clinic in Wheaton, Ill. His special interests include adolescent and addiction medicine, eating disorders, trauma, bipolar disorder, and the psychiatric manifestations of acute and chronic medical conditions.

This article was updated 12/15/17.