User login

How to advise adolescents ISO drugs on the ‘dark web’

There was a time, not so long ago, when in the popular imagination, a drug deal involved an aging hippie in a tie-dyed shirt and love beads, copping a joint at a Dead concert. Today, however, in the age of the Internet and smartphones, a teenager in his bedroom can select, order, and have delivered to his door illicit drugs via the marketplaces on the “dark web.”

As the name implies, the dark web is a subterranean layer of the Internet that is mysterious, ominous, and sometimes lawless. It lies “beneath” the surface web – the layer where grandmothers post on Facebook and purchase on Amazon.

The dark web largely was the brainchild of three mathematicians at the Naval Research Laboratory as a means of encrypting messages exchanged by the intelligence community. They dubbed their project “Tor,” for “The Onion Router,” as the system consists of layer after layer of random relays, permitting anonymity on the Internet with little risk of tracking or surveillance.

This online underworld first came to my attention several years ago. The father of a teen who was being treated for disruptive mood dysregulation, attention-deficit disorder, and alcohol and cannabis use disorder called to inform me that his son had been arrested at Lollapalooza with hundreds of Adderall tablets and Xanax bars. Several weeks later, in session, the young man disclosed to me that he had found simple instructions online about installing Tor, creating a VPN (a virtual private network), accessing the dark web, transacting with bitcoin, and identifying drug marketplaces. He also demonstrated a detailed knowledge of chemical manufacturing in China, pill pressing in Canada, and money laundering in Switzerland.

With the air of an insider sharing “trade secrets,” this young man described how dealers on the dark web avoid detection and ensure secure delivery of the goods: latex gloves, vacuum sealing, and bleach dipping to obviate fingerprints – human and chemical. He said that dealers will send “dummy” packages to throw off the authorities and that buyers often will use the address of a clueless or absent neighbor. In his case, however, the parcels were delivered to his doorstep.

. For one thing, acquiring drugs in this way can seem less risky, as there is no chance of being robbed at gunpoint in a sketchy neighborhood or being busted for possession during a routine traffic stop.

Crossing over to the world of the dark web also can give an adolescent a sense of being clever and rebellious and of pulling a “fast one” on the parents – and on us, the clinicians who are treating them. And a teen who is interested in using illicit substances and plays “Call of Duty” from the comfort of his family’s basement without actual injury or death might assume that he can attain illicit drugs that are safe and inexpensive.

There are counterarguments to misinformation about the dark web. For example, contrary to the notion that buying drugs on the dark web minimizes interdiction or arrest, clinicians should point out that since international law enforcement shut down Silk Road and incarcerated its founder, Ross Ulbricht (also known as “Dread Pirate Roberts”) in 2013, hundreds of other dark web marketplaces such as AlphaBay and Hansa have been silenced and their operators prosecuted.

Moreover, the U.S. Department of Justice recently launched the Joint Criminal Opioid Darknet Enforcement (J-CODE) group, and the U.S. Postal Service Inspection Service reportedly has been hiring cybercrime and dark web specialists to combat drug trafficking. It might come as a surprise to a teen that, in a state where recreational marijuana is legal, transport and delivery of cannabis by the postal service elevates purchase and possession to the level of a violation of federal law. Informing even the most oblivious or oppositional adolescent that a drug felony can disqualify him for college grants and loans, impede his search for gainful employment, or prohibit him from obtaining a professional license, might give him a moment’s pause.

Adolescents seeking to buy drugs on the dark web should brace themselves for another shock. Whether lulled by custom after years of shopping on Amazon or using PayPal, or simply dulled by addiction, they might have a blind trust that bitcoin tumblers and “dark” escrow accounts will secure their payments. It will be rude awakening when they learn that the transfer and holding of currency on the dark web is vulnerable to hackers and to operators of the marketplaces – who are known to simply abscond with funds.

Currently, the drug marketplaces on the dark web represent a thin slice of the total illicit drug trade. These marketplaces, however, are growing quickly and offer buyers a virtual smorgasbord: the leading prescription drugs bought are Xanax and OxyContin, whereas 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)/ecstasy and cannabis are the most commonly purchased controlled Schedule I substances, according to an article in The Economist. The estimated annual sales for 2016 ranged from $100 million to $200 million, but even more alarming is the percentage of substance abusers who have purchased drugs on the dark web: A recent article in The Independent reported that 13.2% of U.S. respondents self-reported making at least one purchase online, whereas in the United Kingdom, the self-reported percentage was 25.3 %, and in Finland, it was 41.4%.

Evidence abounds that drugs purchased on the dark web often are counterfeit and sometimes “dirty.” There is a report of “Viagra” containing cement dust, of “Ambien” containing haloperidol, and “Xanax” laced with fentanyl, the latter having been linked to several deaths and hospital admissions in the Bay Area in 2016. (Big Pharma, in fact, is engaged in surveillance and investigation of the sale of knockoffs online, The Telegraph reported in article about the proliferation of fake drugs available on the surface web).Unfortunately, attempting to reduce teen substance abuse using law enforcement measures directed at dark web marketplaces might be a game of whack-a-mole: As soon as one supply source is staunched, another surfaces. Indeed, addiction should be viewed not simply in terms of the biopsychosocial model, but also as an economic activity. Thus, it might be more beneficial for clinicians to concentrate our resources and efforts on curtailing the demand through education and treatment.

Dr. Marseille is a psychiatrist who works on the staff at a clinic in Winfield, Ill. His special interests include adolescent and addiction medicine, eating disorders, trauma, bipolar disorder, and the psychiatric manifestations of acute and chronic medical conditions.

There was a time, not so long ago, when in the popular imagination, a drug deal involved an aging hippie in a tie-dyed shirt and love beads, copping a joint at a Dead concert. Today, however, in the age of the Internet and smartphones, a teenager in his bedroom can select, order, and have delivered to his door illicit drugs via the marketplaces on the “dark web.”

As the name implies, the dark web is a subterranean layer of the Internet that is mysterious, ominous, and sometimes lawless. It lies “beneath” the surface web – the layer where grandmothers post on Facebook and purchase on Amazon.

The dark web largely was the brainchild of three mathematicians at the Naval Research Laboratory as a means of encrypting messages exchanged by the intelligence community. They dubbed their project “Tor,” for “The Onion Router,” as the system consists of layer after layer of random relays, permitting anonymity on the Internet with little risk of tracking or surveillance.

This online underworld first came to my attention several years ago. The father of a teen who was being treated for disruptive mood dysregulation, attention-deficit disorder, and alcohol and cannabis use disorder called to inform me that his son had been arrested at Lollapalooza with hundreds of Adderall tablets and Xanax bars. Several weeks later, in session, the young man disclosed to me that he had found simple instructions online about installing Tor, creating a VPN (a virtual private network), accessing the dark web, transacting with bitcoin, and identifying drug marketplaces. He also demonstrated a detailed knowledge of chemical manufacturing in China, pill pressing in Canada, and money laundering in Switzerland.

With the air of an insider sharing “trade secrets,” this young man described how dealers on the dark web avoid detection and ensure secure delivery of the goods: latex gloves, vacuum sealing, and bleach dipping to obviate fingerprints – human and chemical. He said that dealers will send “dummy” packages to throw off the authorities and that buyers often will use the address of a clueless or absent neighbor. In his case, however, the parcels were delivered to his doorstep.

. For one thing, acquiring drugs in this way can seem less risky, as there is no chance of being robbed at gunpoint in a sketchy neighborhood or being busted for possession during a routine traffic stop.

Crossing over to the world of the dark web also can give an adolescent a sense of being clever and rebellious and of pulling a “fast one” on the parents – and on us, the clinicians who are treating them. And a teen who is interested in using illicit substances and plays “Call of Duty” from the comfort of his family’s basement without actual injury or death might assume that he can attain illicit drugs that are safe and inexpensive.

There are counterarguments to misinformation about the dark web. For example, contrary to the notion that buying drugs on the dark web minimizes interdiction or arrest, clinicians should point out that since international law enforcement shut down Silk Road and incarcerated its founder, Ross Ulbricht (also known as “Dread Pirate Roberts”) in 2013, hundreds of other dark web marketplaces such as AlphaBay and Hansa have been silenced and their operators prosecuted.

Moreover, the U.S. Department of Justice recently launched the Joint Criminal Opioid Darknet Enforcement (J-CODE) group, and the U.S. Postal Service Inspection Service reportedly has been hiring cybercrime and dark web specialists to combat drug trafficking. It might come as a surprise to a teen that, in a state where recreational marijuana is legal, transport and delivery of cannabis by the postal service elevates purchase and possession to the level of a violation of federal law. Informing even the most oblivious or oppositional adolescent that a drug felony can disqualify him for college grants and loans, impede his search for gainful employment, or prohibit him from obtaining a professional license, might give him a moment’s pause.

Adolescents seeking to buy drugs on the dark web should brace themselves for another shock. Whether lulled by custom after years of shopping on Amazon or using PayPal, or simply dulled by addiction, they might have a blind trust that bitcoin tumblers and “dark” escrow accounts will secure their payments. It will be rude awakening when they learn that the transfer and holding of currency on the dark web is vulnerable to hackers and to operators of the marketplaces – who are known to simply abscond with funds.

Currently, the drug marketplaces on the dark web represent a thin slice of the total illicit drug trade. These marketplaces, however, are growing quickly and offer buyers a virtual smorgasbord: the leading prescription drugs bought are Xanax and OxyContin, whereas 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)/ecstasy and cannabis are the most commonly purchased controlled Schedule I substances, according to an article in The Economist. The estimated annual sales for 2016 ranged from $100 million to $200 million, but even more alarming is the percentage of substance abusers who have purchased drugs on the dark web: A recent article in The Independent reported that 13.2% of U.S. respondents self-reported making at least one purchase online, whereas in the United Kingdom, the self-reported percentage was 25.3 %, and in Finland, it was 41.4%.

Evidence abounds that drugs purchased on the dark web often are counterfeit and sometimes “dirty.” There is a report of “Viagra” containing cement dust, of “Ambien” containing haloperidol, and “Xanax” laced with fentanyl, the latter having been linked to several deaths and hospital admissions in the Bay Area in 2016. (Big Pharma, in fact, is engaged in surveillance and investigation of the sale of knockoffs online, The Telegraph reported in article about the proliferation of fake drugs available on the surface web).Unfortunately, attempting to reduce teen substance abuse using law enforcement measures directed at dark web marketplaces might be a game of whack-a-mole: As soon as one supply source is staunched, another surfaces. Indeed, addiction should be viewed not simply in terms of the biopsychosocial model, but also as an economic activity. Thus, it might be more beneficial for clinicians to concentrate our resources and efforts on curtailing the demand through education and treatment.

Dr. Marseille is a psychiatrist who works on the staff at a clinic in Winfield, Ill. His special interests include adolescent and addiction medicine, eating disorders, trauma, bipolar disorder, and the psychiatric manifestations of acute and chronic medical conditions.

There was a time, not so long ago, when in the popular imagination, a drug deal involved an aging hippie in a tie-dyed shirt and love beads, copping a joint at a Dead concert. Today, however, in the age of the Internet and smartphones, a teenager in his bedroom can select, order, and have delivered to his door illicit drugs via the marketplaces on the “dark web.”

As the name implies, the dark web is a subterranean layer of the Internet that is mysterious, ominous, and sometimes lawless. It lies “beneath” the surface web – the layer where grandmothers post on Facebook and purchase on Amazon.

The dark web largely was the brainchild of three mathematicians at the Naval Research Laboratory as a means of encrypting messages exchanged by the intelligence community. They dubbed their project “Tor,” for “The Onion Router,” as the system consists of layer after layer of random relays, permitting anonymity on the Internet with little risk of tracking or surveillance.

This online underworld first came to my attention several years ago. The father of a teen who was being treated for disruptive mood dysregulation, attention-deficit disorder, and alcohol and cannabis use disorder called to inform me that his son had been arrested at Lollapalooza with hundreds of Adderall tablets and Xanax bars. Several weeks later, in session, the young man disclosed to me that he had found simple instructions online about installing Tor, creating a VPN (a virtual private network), accessing the dark web, transacting with bitcoin, and identifying drug marketplaces. He also demonstrated a detailed knowledge of chemical manufacturing in China, pill pressing in Canada, and money laundering in Switzerland.

With the air of an insider sharing “trade secrets,” this young man described how dealers on the dark web avoid detection and ensure secure delivery of the goods: latex gloves, vacuum sealing, and bleach dipping to obviate fingerprints – human and chemical. He said that dealers will send “dummy” packages to throw off the authorities and that buyers often will use the address of a clueless or absent neighbor. In his case, however, the parcels were delivered to his doorstep.

. For one thing, acquiring drugs in this way can seem less risky, as there is no chance of being robbed at gunpoint in a sketchy neighborhood or being busted for possession during a routine traffic stop.

Crossing over to the world of the dark web also can give an adolescent a sense of being clever and rebellious and of pulling a “fast one” on the parents – and on us, the clinicians who are treating them. And a teen who is interested in using illicit substances and plays “Call of Duty” from the comfort of his family’s basement without actual injury or death might assume that he can attain illicit drugs that are safe and inexpensive.

There are counterarguments to misinformation about the dark web. For example, contrary to the notion that buying drugs on the dark web minimizes interdiction or arrest, clinicians should point out that since international law enforcement shut down Silk Road and incarcerated its founder, Ross Ulbricht (also known as “Dread Pirate Roberts”) in 2013, hundreds of other dark web marketplaces such as AlphaBay and Hansa have been silenced and their operators prosecuted.

Moreover, the U.S. Department of Justice recently launched the Joint Criminal Opioid Darknet Enforcement (J-CODE) group, and the U.S. Postal Service Inspection Service reportedly has been hiring cybercrime and dark web specialists to combat drug trafficking. It might come as a surprise to a teen that, in a state where recreational marijuana is legal, transport and delivery of cannabis by the postal service elevates purchase and possession to the level of a violation of federal law. Informing even the most oblivious or oppositional adolescent that a drug felony can disqualify him for college grants and loans, impede his search for gainful employment, or prohibit him from obtaining a professional license, might give him a moment’s pause.

Adolescents seeking to buy drugs on the dark web should brace themselves for another shock. Whether lulled by custom after years of shopping on Amazon or using PayPal, or simply dulled by addiction, they might have a blind trust that bitcoin tumblers and “dark” escrow accounts will secure their payments. It will be rude awakening when they learn that the transfer and holding of currency on the dark web is vulnerable to hackers and to operators of the marketplaces – who are known to simply abscond with funds.

Currently, the drug marketplaces on the dark web represent a thin slice of the total illicit drug trade. These marketplaces, however, are growing quickly and offer buyers a virtual smorgasbord: the leading prescription drugs bought are Xanax and OxyContin, whereas 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)/ecstasy and cannabis are the most commonly purchased controlled Schedule I substances, according to an article in The Economist. The estimated annual sales for 2016 ranged from $100 million to $200 million, but even more alarming is the percentage of substance abusers who have purchased drugs on the dark web: A recent article in The Independent reported that 13.2% of U.S. respondents self-reported making at least one purchase online, whereas in the United Kingdom, the self-reported percentage was 25.3 %, and in Finland, it was 41.4%.

Evidence abounds that drugs purchased on the dark web often are counterfeit and sometimes “dirty.” There is a report of “Viagra” containing cement dust, of “Ambien” containing haloperidol, and “Xanax” laced with fentanyl, the latter having been linked to several deaths and hospital admissions in the Bay Area in 2016. (Big Pharma, in fact, is engaged in surveillance and investigation of the sale of knockoffs online, The Telegraph reported in article about the proliferation of fake drugs available on the surface web).Unfortunately, attempting to reduce teen substance abuse using law enforcement measures directed at dark web marketplaces might be a game of whack-a-mole: As soon as one supply source is staunched, another surfaces. Indeed, addiction should be viewed not simply in terms of the biopsychosocial model, but also as an economic activity. Thus, it might be more beneficial for clinicians to concentrate our resources and efforts on curtailing the demand through education and treatment.

Dr. Marseille is a psychiatrist who works on the staff at a clinic in Winfield, Ill. His special interests include adolescent and addiction medicine, eating disorders, trauma, bipolar disorder, and the psychiatric manifestations of acute and chronic medical conditions.

Helping patients with addictions get, stay clean

Roughly 6 months ago, a primary care physician referred a patient to our clinic for an assessment for opioid use disorder and a recommendation for treatment. The patient estimated, likely underestimated, his daily heroin use to five bags and dropped positive, in addition to heroin, for benzodiazepines, amphetamines, and cannabis. He was in a profession in which public safety was a critical concern, and he refused to notify his employer’s employee assistance program. He also declined to voluntarily admit himself for detox and treatment at the local, fully accredited addiction program, which was affiliated with a major university medical center. Instead, after an Internet search, the patient opted for an opioid treatment center featuring massage therapy, acupuncture, a stable, a sweat lodge – and a magnificent view of the Pacific Ocean.

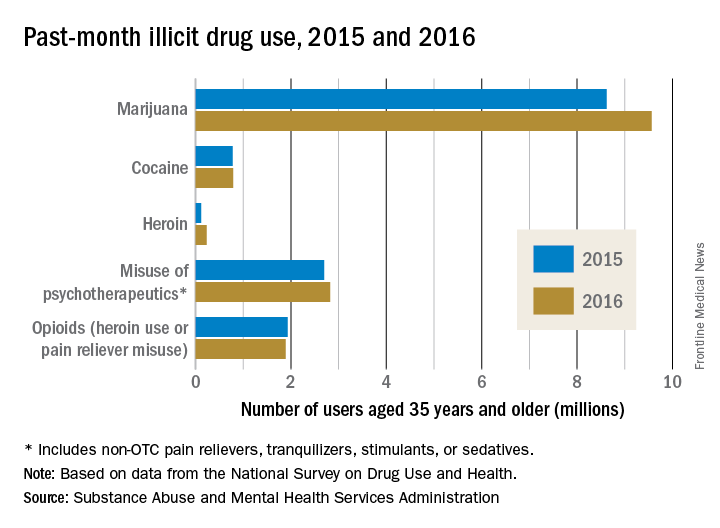

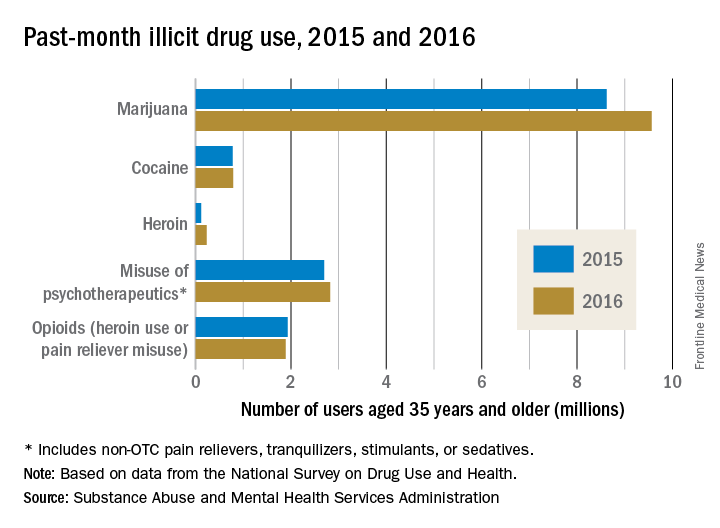

Mental health professionals and lay people alike are aware of the “opioid crisis” – the derailment of lives, the devastation to communities, the death toll. But despite proposals to increase research funding, policies aimed at tightening the prescribing of opioids, and pledges to ramp up interdiction of heroin traffic, there is often an ignorance and confusion regarding the best, evidence-based approaches to getting patients with substance use disorders clean and keeping them clean.

Unfortunately, as with any crisis, there will be opportunists preying on vulnerable patients and their families. And this travesty has reportedly escalated, as outpatient treatment centers take advantage of laws guaranteeing mental health parity and insurance companies paying out tens of thousands of dollars for residential and outpatient opioid treatment. The potential for significant profit is plainly illustrated by the influx of private equity firms, such as Bain Capital, that are investing heavily in treatment centers.

Reports of malfeasance and misconduct, by owners, operators, staff, and others connected with the industry are beginning to get the attention of authorities. There have been reports of outpatient treatment centers that spend lavishly on furnishing, on BMWs and signed art, yet are understaffed, leading to inadequate one-on-one counseling and even sexual transgressions between residents. There are centers that have been investigated for insurance fraud, such as illegally waiving a copay or a deductible or for charging up to $5,000 for a simple urine five drug screen, often multiple times a day. And there is evidence of “junkie hunters” who cruise for people with addictions and brokers who provide such people with fake addresses in order to qualify for insurance plans with excellent benefits for addiction treatment.

Probably the best means to find a suitable outpatient treatment center is by way of a local, experienced, and respected chemical dependency counselor or physician certified in addiction medicine. If people with substance use disorders and their families want to independently conduct a search, as a good rule of thumb, they should be advised to consider programs affiliated with major medical centers and hospitals or outpatient treatment centers that have been established in good standing for years, in contrast to the rash of pop-up, for-profit programs. Of equal, or even greater importance, is that the prospective center ought to be accredited by a national organization, for example, The Joint Commission, and its staff ought to be licensed and credentialed as well.

In addition, there is merit if the staff has been educated, trained, and supervised under the direction of a respected institution. Needless to add, an outpatient treatment center must use evidence-based practices as the bedrock of treatment; this includes pharmacotherapies such as Suboxone and naltrexone (Vivitrol), and behavioral therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, contingency management, and motivational enhancement. To date, massage and essential oils might be relaxing and pleasurable, but they are not considered accepted standard of care.

It is crucial, too, that an outpatient treatment center have both the resources to reliably handle acute medical detox, which can be a potentially life-threatening emergency, and the medical personnel who can assess and treat such medical conditions as hypertension as well as psychiatric illnesses such as bipolar and generalized anxiety disorders. A prospective patient also should inquire whether any of the staff has been the subject of disciplinary action by a licensing board or whether the center has been investigated by the state or a national accrediting organization.

Because addiction so often has facets rooted in the family system, and recovery so often depends on family support, an outpatient treatment center should provide a structured family program integrated into the patient’s treatment and emphasize the importance of continued family involvement after discharge.

Lastly, the best treatment centers often regularly update a patient’s local therapist and physician, spell out the elements of successful aftercare (12-step programs, and so on), and provide amenities, such as calls to a recently discharged patient and an alumni support network.

Dr. Marseille is a psychiatrist who works on the staff of a clinic in Wheaton, Ill. His special interests include adolescent and addiction medicine, eating disorders, trauma, bipolar disorder, and the psychiatric manifestations of acute and chronic medical conditions.

This article was updated 12/15/17.

Roughly 6 months ago, a primary care physician referred a patient to our clinic for an assessment for opioid use disorder and a recommendation for treatment. The patient estimated, likely underestimated, his daily heroin use to five bags and dropped positive, in addition to heroin, for benzodiazepines, amphetamines, and cannabis. He was in a profession in which public safety was a critical concern, and he refused to notify his employer’s employee assistance program. He also declined to voluntarily admit himself for detox and treatment at the local, fully accredited addiction program, which was affiliated with a major university medical center. Instead, after an Internet search, the patient opted for an opioid treatment center featuring massage therapy, acupuncture, a stable, a sweat lodge – and a magnificent view of the Pacific Ocean.

Mental health professionals and lay people alike are aware of the “opioid crisis” – the derailment of lives, the devastation to communities, the death toll. But despite proposals to increase research funding, policies aimed at tightening the prescribing of opioids, and pledges to ramp up interdiction of heroin traffic, there is often an ignorance and confusion regarding the best, evidence-based approaches to getting patients with substance use disorders clean and keeping them clean.

Unfortunately, as with any crisis, there will be opportunists preying on vulnerable patients and their families. And this travesty has reportedly escalated, as outpatient treatment centers take advantage of laws guaranteeing mental health parity and insurance companies paying out tens of thousands of dollars for residential and outpatient opioid treatment. The potential for significant profit is plainly illustrated by the influx of private equity firms, such as Bain Capital, that are investing heavily in treatment centers.

Reports of malfeasance and misconduct, by owners, operators, staff, and others connected with the industry are beginning to get the attention of authorities. There have been reports of outpatient treatment centers that spend lavishly on furnishing, on BMWs and signed art, yet are understaffed, leading to inadequate one-on-one counseling and even sexual transgressions between residents. There are centers that have been investigated for insurance fraud, such as illegally waiving a copay or a deductible or for charging up to $5,000 for a simple urine five drug screen, often multiple times a day. And there is evidence of “junkie hunters” who cruise for people with addictions and brokers who provide such people with fake addresses in order to qualify for insurance plans with excellent benefits for addiction treatment.

Probably the best means to find a suitable outpatient treatment center is by way of a local, experienced, and respected chemical dependency counselor or physician certified in addiction medicine. If people with substance use disorders and their families want to independently conduct a search, as a good rule of thumb, they should be advised to consider programs affiliated with major medical centers and hospitals or outpatient treatment centers that have been established in good standing for years, in contrast to the rash of pop-up, for-profit programs. Of equal, or even greater importance, is that the prospective center ought to be accredited by a national organization, for example, The Joint Commission, and its staff ought to be licensed and credentialed as well.

In addition, there is merit if the staff has been educated, trained, and supervised under the direction of a respected institution. Needless to add, an outpatient treatment center must use evidence-based practices as the bedrock of treatment; this includes pharmacotherapies such as Suboxone and naltrexone (Vivitrol), and behavioral therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, contingency management, and motivational enhancement. To date, massage and essential oils might be relaxing and pleasurable, but they are not considered accepted standard of care.

It is crucial, too, that an outpatient treatment center have both the resources to reliably handle acute medical detox, which can be a potentially life-threatening emergency, and the medical personnel who can assess and treat such medical conditions as hypertension as well as psychiatric illnesses such as bipolar and generalized anxiety disorders. A prospective patient also should inquire whether any of the staff has been the subject of disciplinary action by a licensing board or whether the center has been investigated by the state or a national accrediting organization.

Because addiction so often has facets rooted in the family system, and recovery so often depends on family support, an outpatient treatment center should provide a structured family program integrated into the patient’s treatment and emphasize the importance of continued family involvement after discharge.

Lastly, the best treatment centers often regularly update a patient’s local therapist and physician, spell out the elements of successful aftercare (12-step programs, and so on), and provide amenities, such as calls to a recently discharged patient and an alumni support network.

Dr. Marseille is a psychiatrist who works on the staff of a clinic in Wheaton, Ill. His special interests include adolescent and addiction medicine, eating disorders, trauma, bipolar disorder, and the psychiatric manifestations of acute and chronic medical conditions.

This article was updated 12/15/17.

Roughly 6 months ago, a primary care physician referred a patient to our clinic for an assessment for opioid use disorder and a recommendation for treatment. The patient estimated, likely underestimated, his daily heroin use to five bags and dropped positive, in addition to heroin, for benzodiazepines, amphetamines, and cannabis. He was in a profession in which public safety was a critical concern, and he refused to notify his employer’s employee assistance program. He also declined to voluntarily admit himself for detox and treatment at the local, fully accredited addiction program, which was affiliated with a major university medical center. Instead, after an Internet search, the patient opted for an opioid treatment center featuring massage therapy, acupuncture, a stable, a sweat lodge – and a magnificent view of the Pacific Ocean.

Mental health professionals and lay people alike are aware of the “opioid crisis” – the derailment of lives, the devastation to communities, the death toll. But despite proposals to increase research funding, policies aimed at tightening the prescribing of opioids, and pledges to ramp up interdiction of heroin traffic, there is often an ignorance and confusion regarding the best, evidence-based approaches to getting patients with substance use disorders clean and keeping them clean.

Unfortunately, as with any crisis, there will be opportunists preying on vulnerable patients and their families. And this travesty has reportedly escalated, as outpatient treatment centers take advantage of laws guaranteeing mental health parity and insurance companies paying out tens of thousands of dollars for residential and outpatient opioid treatment. The potential for significant profit is plainly illustrated by the influx of private equity firms, such as Bain Capital, that are investing heavily in treatment centers.

Reports of malfeasance and misconduct, by owners, operators, staff, and others connected with the industry are beginning to get the attention of authorities. There have been reports of outpatient treatment centers that spend lavishly on furnishing, on BMWs and signed art, yet are understaffed, leading to inadequate one-on-one counseling and even sexual transgressions between residents. There are centers that have been investigated for insurance fraud, such as illegally waiving a copay or a deductible or for charging up to $5,000 for a simple urine five drug screen, often multiple times a day. And there is evidence of “junkie hunters” who cruise for people with addictions and brokers who provide such people with fake addresses in order to qualify for insurance plans with excellent benefits for addiction treatment.

Probably the best means to find a suitable outpatient treatment center is by way of a local, experienced, and respected chemical dependency counselor or physician certified in addiction medicine. If people with substance use disorders and their families want to independently conduct a search, as a good rule of thumb, they should be advised to consider programs affiliated with major medical centers and hospitals or outpatient treatment centers that have been established in good standing for years, in contrast to the rash of pop-up, for-profit programs. Of equal, or even greater importance, is that the prospective center ought to be accredited by a national organization, for example, The Joint Commission, and its staff ought to be licensed and credentialed as well.

In addition, there is merit if the staff has been educated, trained, and supervised under the direction of a respected institution. Needless to add, an outpatient treatment center must use evidence-based practices as the bedrock of treatment; this includes pharmacotherapies such as Suboxone and naltrexone (Vivitrol), and behavioral therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, contingency management, and motivational enhancement. To date, massage and essential oils might be relaxing and pleasurable, but they are not considered accepted standard of care.

It is crucial, too, that an outpatient treatment center have both the resources to reliably handle acute medical detox, which can be a potentially life-threatening emergency, and the medical personnel who can assess and treat such medical conditions as hypertension as well as psychiatric illnesses such as bipolar and generalized anxiety disorders. A prospective patient also should inquire whether any of the staff has been the subject of disciplinary action by a licensing board or whether the center has been investigated by the state or a national accrediting organization.

Because addiction so often has facets rooted in the family system, and recovery so often depends on family support, an outpatient treatment center should provide a structured family program integrated into the patient’s treatment and emphasize the importance of continued family involvement after discharge.

Lastly, the best treatment centers often regularly update a patient’s local therapist and physician, spell out the elements of successful aftercare (12-step programs, and so on), and provide amenities, such as calls to a recently discharged patient and an alumni support network.

Dr. Marseille is a psychiatrist who works on the staff of a clinic in Wheaton, Ill. His special interests include adolescent and addiction medicine, eating disorders, trauma, bipolar disorder, and the psychiatric manifestations of acute and chronic medical conditions.

This article was updated 12/15/17.