User login

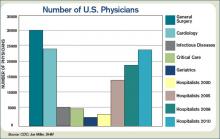

No matter how big a hospital medicine group is, the leader is likely to say “but we need a couple more.” As the fastest-growing medical specialty in the history of American medicine, there never seem to be enough hospitalists (see Figure 1, p. 28).

“The programs are getting larger and larger, ranging anywhere from 20 to 100 physicians in a hospitalist group,” says Jeffrey Hay, MD, senior vice president of medical operations for Lakeside Systems Inc. in Los Angeles.

Because of this rapid growth, two questions become apparent:

1. How is a big hospitalist group defined?

2. What does it take to manage a big group well?

How Big is Big?

Although what constitutes a big hospitalist group is relative, Leslie Flores and her partner, John Nelson, MD, of Nelson/Flores Associates, LLC, La Quinta, Calif., estimate with about 20-30 hospitalists, the role of the medical director becomes a different job than for the typical-sized practice of 10-15 hospitalists.

According to SHM Executive Advisor to the CEO Joseph Miller, this year’s “Society of Hospital Medicine 2007-08 Survey: The Authoritative Source on the State of the Hospitalist Movement” revealed only eight groups with more than 40 hospitalists (excluding the multistate hospitalist management companies). In the approximate 2,200 hospitalist groups in the U.S., Miller estimates there are perhaps 40 groups with 40 or more physicians compared with two in the previous 2005-06 survey.

Medical directors of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) ranging from 22-100 people offer varied insights about how the role of medical director changes as groups grow from big to bigger to biggest.

Big

Jeffery Kin, MD, medical director of the private-practice group Fredericks Hospitalist Group PC, manages 22 hospitalists, and about 130-140 inpatients and 45 admissions a day at Mary Washington Hospital in Fredericksburg, Va. They began as a team of three in 2000 as the outgrowth of a hospital house-doctor program.

“The medical director’s role changes and evolves with the growth of the group,” says Dr. Kin. He and other medical directors of larger groups find it more difficult to retain the informal shift arrival or departure and lunches together that were possible when the HMG was smaller. “Now that we are bigger it is more ‘protocolized,’” Dr. Kin says, “but we try to maintain a family-like atmosphere because I think it makes physicians want to stay with the group long term and not move on with every little problem or challenge that inevitably arises in the changing filed of hospital medicine.”

William Ford, MD, program medical director for Cogent Healthcare and the chief of hospital medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia, considers his group of 28 hospitalists to be a “small” big group. Dr. Ford’s group, which covers three of the four hospitals in the university health systems, grew from five hospitalists in September 2006. He devotes about half his time on personnel issues, including recruitment, retention, and staff development.

As groups grow, so does diversity, requiring more flexibility to manage leaves of absence, scheduling, and day-to-day practice. “In a large group we tend to bring on new measures,” Dr. Ford says. “We change like the wind, so if you aren’t ready for that, you will have a lot of turnover.”

Bigger

Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, MBA, division chief, hospital medicine, University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, grew his HMG from 3.6 FTEs three years ago to the 47.5 FTEs (40 physician FTEs and 7.5 FTEs nurse practitioners) they now employ. The group, which covers four hospitals ranging from a 30-bed community hospital to a 770-bed academic hospital, is the biggest HMG in New England. “Our budget numbers for charges and volume are 2.19 times what we projected in the budget,” he says.

With an average of 185 billable patient encounters per day, Dr. Gundersen attributes his successes to a management style based on a financial business model and a revision of the compensation plan. By increasing effectiveness, they reward their doctors with more free time and subsequently improved physician retention.

As the group, the budget, and the financial impact all expand, formal training becomes more important for leaders. While few HMG leaders have a background in the strategic processes of running a company, Dr. Gundersen earned his MBA and believes his training made it easier to talk to administrators, meet clients, track data, effect change, and better handle the politics inherent to the job. “The role is a lot more political than people are aware of because you are such a big presence to the hospital,” he says. “Everybody wants something from you.”

Part of that phenomenon, coined “medical creep” by one hospitalist, can best be defined as the gradual increase in workload shifted to HMGs without a proportional shift in resources to do the work. Work previously done by either surgical specialists or medical subspecialists must be shifted as they more narrowly define their workload; what is left over (more general medical care, phone calls, after-hours work, and paperwork) goes to “co-managing” hospitalists.

Asked about this phenomenon, Tom Lorence, MD, chief of hospitalist medicine for the Northwest Kaiser Permanente region, Portland, Ore., says: “The larger the hospitalist groups become, the bigger a target we are for this shifting. Most try to justify it by saying, ‘It is only a little more work.’ ”

Dr. Lorence and two colleagues began his HMG in 1990; he now manages 55 hospitalists at three facilities. “Administrators have to be convinced that it is worth the money to reshift their priorities and give more resources to the hospital medicine groups,” he says.

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, professor and chief, division of hospital medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, moved to his current post last September. Northwestern Memorial Hospital almost doubled its hospitalists to 42 in one year. The initial challenges at Northwestern primarily include assimilating new faculty and establishing a culture of thriving on change, says Dr. Williams, who is also editor in chief of the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Biggest

The distinction between academic and non-academic programs is an important one says Michael B. Heisler, MD, MPH, who became the interim medical director of Emory Healthcare, Atlanta, in March 2007 when Dr. Williams moved to Northwestern. Generally, the Emory group has increased in size by 20% each of the past five years. Beginning with nine hospitalists in 1999, it now exceeds 80 (see Figure 2, p. 28).

Academic hospitals have additional stakeholders and deliverables expected by those to whom the medical director reports. Whereas community hospital medicine programs are driven by patient encounters/RVUs, quality improvement, and the bottom line, academic groups also must engage in scholarly activities.

Dr. Heisler and his group have just completed a three-year strategic plan that emphasizes medical education and research and a plateau to the group’s growth.

“We can’t be the premier academic program with growth going through the roof,” Dr. Heisler says. “With some limits we are not going to increase services within our institutions and will not entertain requests to grow into any other facilities through 2010. You can’t develop faculty, define protected time, and invest in scholarly work when you are constantly in growth mode.”

Strategic planning has a different tone for Tyler Jung, MD, director of inpatient services of the multi-specialty group HealthCare Partners, who took over that position three years ago when Dr. Hay left. About 100 hospitalists are employed under the HealthCare Partners umbrella; approximately 85 are on the payroll, and 15 work in a strategic alliance. The HMG covers 14 community hospitals in Southern California, about 14 hospitals in Las Vegas, Nevada, and about five hospitals in the Tampa/Orlando area of Florida.

The full-risk California medical model drives a lot of the metrics. “We look at [relative value unit] goals for our hospitalists, but mostly to ensure proper staffing,” Dr. Jung says. “We are satisfied when our docs have 12 to 14 encounters a day. In the service market you’d go broke with that, but I’d rather have our hospitalists see our patients twice a day because it drives quality and it turns out to be more cost effective.”

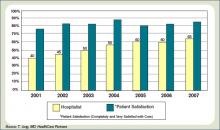

Some of the outcomes Dr. Jung regularly reviews include patient utilization per membership (admit rates, readmit data, and length of stay), and these metrics are largely unchanged as they have grown. “Additionally, maintaining high patient satisfaction can be overlooked, but is critical with the growth of any program,” he says (see Figure 3, p. 28).

Dr. Williams, who began the hospitalist group at Emory Healthcare, says the primary challenges he faced as that program grew were finding capable physicians willing to join a new or expanding program; managing the different cultures at different hospitals and working to ensure they all felt a part of the whole; having sufficient administrative support time to manage recruitment and credentialing; and keeping up constant communications with individuals and leadership at all sites. He found it helpful to occasionally rotate hospitalists, especially the more senior physicians, so they could appreciate the workload and issues at different sites.

Dr. Williams, who trained in internal medicine but later became board certified in emergency medicine, is not surprised Dr. Jung has some background in critical care, as does Dr. Heisler. He surmises they also all have well-honed administrative skills. “The experience I had in running a 65,000-visit-a-year emergency room and a 45,000-visit-a-year urgent-care center gave me the skills to run a large hospital medicine program,” Dr. Williams says. TH

Andrea M. Sattinger is a medical writer based in North Carolina.

No matter how big a hospital medicine group is, the leader is likely to say “but we need a couple more.” As the fastest-growing medical specialty in the history of American medicine, there never seem to be enough hospitalists (see Figure 1, p. 28).

“The programs are getting larger and larger, ranging anywhere from 20 to 100 physicians in a hospitalist group,” says Jeffrey Hay, MD, senior vice president of medical operations for Lakeside Systems Inc. in Los Angeles.

Because of this rapid growth, two questions become apparent:

1. How is a big hospitalist group defined?

2. What does it take to manage a big group well?

How Big is Big?

Although what constitutes a big hospitalist group is relative, Leslie Flores and her partner, John Nelson, MD, of Nelson/Flores Associates, LLC, La Quinta, Calif., estimate with about 20-30 hospitalists, the role of the medical director becomes a different job than for the typical-sized practice of 10-15 hospitalists.

According to SHM Executive Advisor to the CEO Joseph Miller, this year’s “Society of Hospital Medicine 2007-08 Survey: The Authoritative Source on the State of the Hospitalist Movement” revealed only eight groups with more than 40 hospitalists (excluding the multistate hospitalist management companies). In the approximate 2,200 hospitalist groups in the U.S., Miller estimates there are perhaps 40 groups with 40 or more physicians compared with two in the previous 2005-06 survey.

Medical directors of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) ranging from 22-100 people offer varied insights about how the role of medical director changes as groups grow from big to bigger to biggest.

Big

Jeffery Kin, MD, medical director of the private-practice group Fredericks Hospitalist Group PC, manages 22 hospitalists, and about 130-140 inpatients and 45 admissions a day at Mary Washington Hospital in Fredericksburg, Va. They began as a team of three in 2000 as the outgrowth of a hospital house-doctor program.

“The medical director’s role changes and evolves with the growth of the group,” says Dr. Kin. He and other medical directors of larger groups find it more difficult to retain the informal shift arrival or departure and lunches together that were possible when the HMG was smaller. “Now that we are bigger it is more ‘protocolized,’” Dr. Kin says, “but we try to maintain a family-like atmosphere because I think it makes physicians want to stay with the group long term and not move on with every little problem or challenge that inevitably arises in the changing filed of hospital medicine.”

William Ford, MD, program medical director for Cogent Healthcare and the chief of hospital medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia, considers his group of 28 hospitalists to be a “small” big group. Dr. Ford’s group, which covers three of the four hospitals in the university health systems, grew from five hospitalists in September 2006. He devotes about half his time on personnel issues, including recruitment, retention, and staff development.

As groups grow, so does diversity, requiring more flexibility to manage leaves of absence, scheduling, and day-to-day practice. “In a large group we tend to bring on new measures,” Dr. Ford says. “We change like the wind, so if you aren’t ready for that, you will have a lot of turnover.”

Bigger

Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, MBA, division chief, hospital medicine, University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, grew his HMG from 3.6 FTEs three years ago to the 47.5 FTEs (40 physician FTEs and 7.5 FTEs nurse practitioners) they now employ. The group, which covers four hospitals ranging from a 30-bed community hospital to a 770-bed academic hospital, is the biggest HMG in New England. “Our budget numbers for charges and volume are 2.19 times what we projected in the budget,” he says.

With an average of 185 billable patient encounters per day, Dr. Gundersen attributes his successes to a management style based on a financial business model and a revision of the compensation plan. By increasing effectiveness, they reward their doctors with more free time and subsequently improved physician retention.

As the group, the budget, and the financial impact all expand, formal training becomes more important for leaders. While few HMG leaders have a background in the strategic processes of running a company, Dr. Gundersen earned his MBA and believes his training made it easier to talk to administrators, meet clients, track data, effect change, and better handle the politics inherent to the job. “The role is a lot more political than people are aware of because you are such a big presence to the hospital,” he says. “Everybody wants something from you.”

Part of that phenomenon, coined “medical creep” by one hospitalist, can best be defined as the gradual increase in workload shifted to HMGs without a proportional shift in resources to do the work. Work previously done by either surgical specialists or medical subspecialists must be shifted as they more narrowly define their workload; what is left over (more general medical care, phone calls, after-hours work, and paperwork) goes to “co-managing” hospitalists.

Asked about this phenomenon, Tom Lorence, MD, chief of hospitalist medicine for the Northwest Kaiser Permanente region, Portland, Ore., says: “The larger the hospitalist groups become, the bigger a target we are for this shifting. Most try to justify it by saying, ‘It is only a little more work.’ ”

Dr. Lorence and two colleagues began his HMG in 1990; he now manages 55 hospitalists at three facilities. “Administrators have to be convinced that it is worth the money to reshift their priorities and give more resources to the hospital medicine groups,” he says.

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, professor and chief, division of hospital medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, moved to his current post last September. Northwestern Memorial Hospital almost doubled its hospitalists to 42 in one year. The initial challenges at Northwestern primarily include assimilating new faculty and establishing a culture of thriving on change, says Dr. Williams, who is also editor in chief of the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Biggest

The distinction between academic and non-academic programs is an important one says Michael B. Heisler, MD, MPH, who became the interim medical director of Emory Healthcare, Atlanta, in March 2007 when Dr. Williams moved to Northwestern. Generally, the Emory group has increased in size by 20% each of the past five years. Beginning with nine hospitalists in 1999, it now exceeds 80 (see Figure 2, p. 28).

Academic hospitals have additional stakeholders and deliverables expected by those to whom the medical director reports. Whereas community hospital medicine programs are driven by patient encounters/RVUs, quality improvement, and the bottom line, academic groups also must engage in scholarly activities.

Dr. Heisler and his group have just completed a three-year strategic plan that emphasizes medical education and research and a plateau to the group’s growth.

“We can’t be the premier academic program with growth going through the roof,” Dr. Heisler says. “With some limits we are not going to increase services within our institutions and will not entertain requests to grow into any other facilities through 2010. You can’t develop faculty, define protected time, and invest in scholarly work when you are constantly in growth mode.”

Strategic planning has a different tone for Tyler Jung, MD, director of inpatient services of the multi-specialty group HealthCare Partners, who took over that position three years ago when Dr. Hay left. About 100 hospitalists are employed under the HealthCare Partners umbrella; approximately 85 are on the payroll, and 15 work in a strategic alliance. The HMG covers 14 community hospitals in Southern California, about 14 hospitals in Las Vegas, Nevada, and about five hospitals in the Tampa/Orlando area of Florida.

The full-risk California medical model drives a lot of the metrics. “We look at [relative value unit] goals for our hospitalists, but mostly to ensure proper staffing,” Dr. Jung says. “We are satisfied when our docs have 12 to 14 encounters a day. In the service market you’d go broke with that, but I’d rather have our hospitalists see our patients twice a day because it drives quality and it turns out to be more cost effective.”

Some of the outcomes Dr. Jung regularly reviews include patient utilization per membership (admit rates, readmit data, and length of stay), and these metrics are largely unchanged as they have grown. “Additionally, maintaining high patient satisfaction can be overlooked, but is critical with the growth of any program,” he says (see Figure 3, p. 28).

Dr. Williams, who began the hospitalist group at Emory Healthcare, says the primary challenges he faced as that program grew were finding capable physicians willing to join a new or expanding program; managing the different cultures at different hospitals and working to ensure they all felt a part of the whole; having sufficient administrative support time to manage recruitment and credentialing; and keeping up constant communications with individuals and leadership at all sites. He found it helpful to occasionally rotate hospitalists, especially the more senior physicians, so they could appreciate the workload and issues at different sites.

Dr. Williams, who trained in internal medicine but later became board certified in emergency medicine, is not surprised Dr. Jung has some background in critical care, as does Dr. Heisler. He surmises they also all have well-honed administrative skills. “The experience I had in running a 65,000-visit-a-year emergency room and a 45,000-visit-a-year urgent-care center gave me the skills to run a large hospital medicine program,” Dr. Williams says. TH

Andrea M. Sattinger is a medical writer based in North Carolina.

No matter how big a hospital medicine group is, the leader is likely to say “but we need a couple more.” As the fastest-growing medical specialty in the history of American medicine, there never seem to be enough hospitalists (see Figure 1, p. 28).

“The programs are getting larger and larger, ranging anywhere from 20 to 100 physicians in a hospitalist group,” says Jeffrey Hay, MD, senior vice president of medical operations for Lakeside Systems Inc. in Los Angeles.

Because of this rapid growth, two questions become apparent:

1. How is a big hospitalist group defined?

2. What does it take to manage a big group well?

How Big is Big?

Although what constitutes a big hospitalist group is relative, Leslie Flores and her partner, John Nelson, MD, of Nelson/Flores Associates, LLC, La Quinta, Calif., estimate with about 20-30 hospitalists, the role of the medical director becomes a different job than for the typical-sized practice of 10-15 hospitalists.

According to SHM Executive Advisor to the CEO Joseph Miller, this year’s “Society of Hospital Medicine 2007-08 Survey: The Authoritative Source on the State of the Hospitalist Movement” revealed only eight groups with more than 40 hospitalists (excluding the multistate hospitalist management companies). In the approximate 2,200 hospitalist groups in the U.S., Miller estimates there are perhaps 40 groups with 40 or more physicians compared with two in the previous 2005-06 survey.

Medical directors of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) ranging from 22-100 people offer varied insights about how the role of medical director changes as groups grow from big to bigger to biggest.

Big

Jeffery Kin, MD, medical director of the private-practice group Fredericks Hospitalist Group PC, manages 22 hospitalists, and about 130-140 inpatients and 45 admissions a day at Mary Washington Hospital in Fredericksburg, Va. They began as a team of three in 2000 as the outgrowth of a hospital house-doctor program.

“The medical director’s role changes and evolves with the growth of the group,” says Dr. Kin. He and other medical directors of larger groups find it more difficult to retain the informal shift arrival or departure and lunches together that were possible when the HMG was smaller. “Now that we are bigger it is more ‘protocolized,’” Dr. Kin says, “but we try to maintain a family-like atmosphere because I think it makes physicians want to stay with the group long term and not move on with every little problem or challenge that inevitably arises in the changing filed of hospital medicine.”

William Ford, MD, program medical director for Cogent Healthcare and the chief of hospital medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia, considers his group of 28 hospitalists to be a “small” big group. Dr. Ford’s group, which covers three of the four hospitals in the university health systems, grew from five hospitalists in September 2006. He devotes about half his time on personnel issues, including recruitment, retention, and staff development.

As groups grow, so does diversity, requiring more flexibility to manage leaves of absence, scheduling, and day-to-day practice. “In a large group we tend to bring on new measures,” Dr. Ford says. “We change like the wind, so if you aren’t ready for that, you will have a lot of turnover.”

Bigger

Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, MBA, division chief, hospital medicine, University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, grew his HMG from 3.6 FTEs three years ago to the 47.5 FTEs (40 physician FTEs and 7.5 FTEs nurse practitioners) they now employ. The group, which covers four hospitals ranging from a 30-bed community hospital to a 770-bed academic hospital, is the biggest HMG in New England. “Our budget numbers for charges and volume are 2.19 times what we projected in the budget,” he says.

With an average of 185 billable patient encounters per day, Dr. Gundersen attributes his successes to a management style based on a financial business model and a revision of the compensation plan. By increasing effectiveness, they reward their doctors with more free time and subsequently improved physician retention.

As the group, the budget, and the financial impact all expand, formal training becomes more important for leaders. While few HMG leaders have a background in the strategic processes of running a company, Dr. Gundersen earned his MBA and believes his training made it easier to talk to administrators, meet clients, track data, effect change, and better handle the politics inherent to the job. “The role is a lot more political than people are aware of because you are such a big presence to the hospital,” he says. “Everybody wants something from you.”

Part of that phenomenon, coined “medical creep” by one hospitalist, can best be defined as the gradual increase in workload shifted to HMGs without a proportional shift in resources to do the work. Work previously done by either surgical specialists or medical subspecialists must be shifted as they more narrowly define their workload; what is left over (more general medical care, phone calls, after-hours work, and paperwork) goes to “co-managing” hospitalists.

Asked about this phenomenon, Tom Lorence, MD, chief of hospitalist medicine for the Northwest Kaiser Permanente region, Portland, Ore., says: “The larger the hospitalist groups become, the bigger a target we are for this shifting. Most try to justify it by saying, ‘It is only a little more work.’ ”

Dr. Lorence and two colleagues began his HMG in 1990; he now manages 55 hospitalists at three facilities. “Administrators have to be convinced that it is worth the money to reshift their priorities and give more resources to the hospital medicine groups,” he says.

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, professor and chief, division of hospital medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, moved to his current post last September. Northwestern Memorial Hospital almost doubled its hospitalists to 42 in one year. The initial challenges at Northwestern primarily include assimilating new faculty and establishing a culture of thriving on change, says Dr. Williams, who is also editor in chief of the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Biggest

The distinction between academic and non-academic programs is an important one says Michael B. Heisler, MD, MPH, who became the interim medical director of Emory Healthcare, Atlanta, in March 2007 when Dr. Williams moved to Northwestern. Generally, the Emory group has increased in size by 20% each of the past five years. Beginning with nine hospitalists in 1999, it now exceeds 80 (see Figure 2, p. 28).

Academic hospitals have additional stakeholders and deliverables expected by those to whom the medical director reports. Whereas community hospital medicine programs are driven by patient encounters/RVUs, quality improvement, and the bottom line, academic groups also must engage in scholarly activities.

Dr. Heisler and his group have just completed a three-year strategic plan that emphasizes medical education and research and a plateau to the group’s growth.

“We can’t be the premier academic program with growth going through the roof,” Dr. Heisler says. “With some limits we are not going to increase services within our institutions and will not entertain requests to grow into any other facilities through 2010. You can’t develop faculty, define protected time, and invest in scholarly work when you are constantly in growth mode.”

Strategic planning has a different tone for Tyler Jung, MD, director of inpatient services of the multi-specialty group HealthCare Partners, who took over that position three years ago when Dr. Hay left. About 100 hospitalists are employed under the HealthCare Partners umbrella; approximately 85 are on the payroll, and 15 work in a strategic alliance. The HMG covers 14 community hospitals in Southern California, about 14 hospitals in Las Vegas, Nevada, and about five hospitals in the Tampa/Orlando area of Florida.

The full-risk California medical model drives a lot of the metrics. “We look at [relative value unit] goals for our hospitalists, but mostly to ensure proper staffing,” Dr. Jung says. “We are satisfied when our docs have 12 to 14 encounters a day. In the service market you’d go broke with that, but I’d rather have our hospitalists see our patients twice a day because it drives quality and it turns out to be more cost effective.”

Some of the outcomes Dr. Jung regularly reviews include patient utilization per membership (admit rates, readmit data, and length of stay), and these metrics are largely unchanged as they have grown. “Additionally, maintaining high patient satisfaction can be overlooked, but is critical with the growth of any program,” he says (see Figure 3, p. 28).

Dr. Williams, who began the hospitalist group at Emory Healthcare, says the primary challenges he faced as that program grew were finding capable physicians willing to join a new or expanding program; managing the different cultures at different hospitals and working to ensure they all felt a part of the whole; having sufficient administrative support time to manage recruitment and credentialing; and keeping up constant communications with individuals and leadership at all sites. He found it helpful to occasionally rotate hospitalists, especially the more senior physicians, so they could appreciate the workload and issues at different sites.

Dr. Williams, who trained in internal medicine but later became board certified in emergency medicine, is not surprised Dr. Jung has some background in critical care, as does Dr. Heisler. He surmises they also all have well-honed administrative skills. “The experience I had in running a 65,000-visit-a-year emergency room and a 45,000-visit-a-year urgent-care center gave me the skills to run a large hospital medicine program,” Dr. Williams says. TH

Andrea M. Sattinger is a medical writer based in North Carolina.