User login

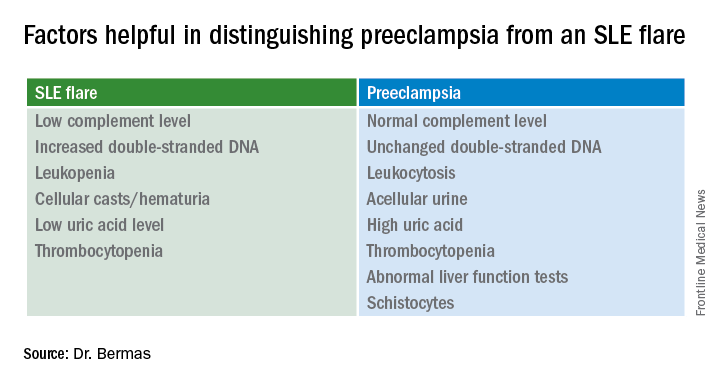

SNOWMASS, COLO. – No hard and fast test exists that would enable a physician to tell a flare of systemic lupus erythematosus from preeclampsia in a pregnant lupus patient who becomes hypertensive and ill, but there are highly useful clues, Bonnie L. Bermas, MD, said at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

“There is no perfect way of distinguishing between a lupus flare and preeclampsia. I’ve never walked away from the labor floor and said, ‘This is great – I know this is a lupus flare,’ or ‘I know this is preeclampsia.’ But you make your best guess as to which one it is, and that will inform your management,” explained Dr. Bermas, a rheumatologist and director of the clinical lupus program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Why do we care? Because if it’s preeclampsia the mother needs to be delivered immediately for her safety, while if it’s an SLE flare sometimes you can treat it and get the fetus to a more viable age. A 23-week-old baby isn’t at all likely to make it, but a 27-week-old could,” Dr. Bermas said.

The fact that the patient has thrombocytopenia isn’t helpful in making the distinction, since that feature is shared in common by SLE flares and preeclampsia. But the uric acid level is a useful clue.

It’s quite possible that much of the current guesswork in predicting preeclampsia and other adverse pregnancy outcomes in lupus patients will give way to reliable risk testing within the next several years. Investigators in the U.S. multicenter prospective PROMISSE (Predictors of Pregnancy Outcome: Biomarkers in APL Syndrome and SLE) study have reported that circulating levels of the angiogenic factors soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 and placental growth factor were abnormal as early as gestational weeks 12-15 in patients who went on to develop preeclampsia or other adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Indeed, monthly testing demonstrated that SLE patients in the top quartile for soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 at weeks 12-15 had an adjusted 17.3-fold greater likelihood of experiencing a severe adverse pregnancy outcome than did those in the lowest quartile. A high level had a positive predictive value of 61% and a negative predictive value of 93% (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jan;214[1]:108.e1-14). These findings are being further explored in ongoing studies.

“Hopefully, in another few years we’re going to be able to say early in pregnancy, ‘This person is set up to get preeclampsia.’ Maybe that will lead to better treatment as well,” Dr. Bermas said.

The risk of preeclampsia has been shown to be threefold higher in women with SLE than in the general population of pregnant women in a study of more than 16.7 million admissions for childbirth in the United States during a 4-year period. The SLE patients were also at 2.4-fold increased risk for preterm labor. Their risks of infection, thrombosis, thrombocytopenia, and transfusion were each three- to seven-fold higher as well (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Aug;199[2]:127.e1-16).

Dr. Bermas reported serving as a consultant to UCB.

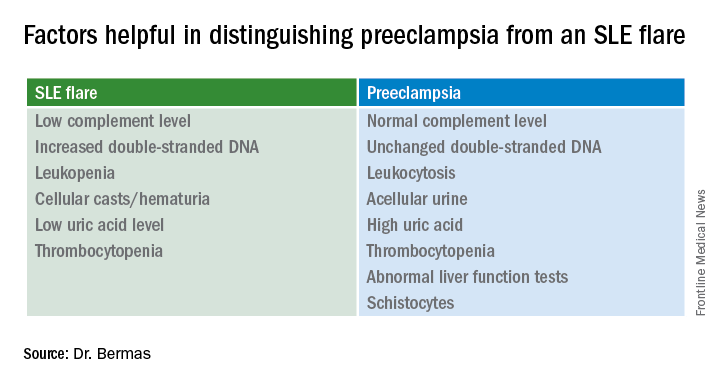

SNOWMASS, COLO. – No hard and fast test exists that would enable a physician to tell a flare of systemic lupus erythematosus from preeclampsia in a pregnant lupus patient who becomes hypertensive and ill, but there are highly useful clues, Bonnie L. Bermas, MD, said at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

“There is no perfect way of distinguishing between a lupus flare and preeclampsia. I’ve never walked away from the labor floor and said, ‘This is great – I know this is a lupus flare,’ or ‘I know this is preeclampsia.’ But you make your best guess as to which one it is, and that will inform your management,” explained Dr. Bermas, a rheumatologist and director of the clinical lupus program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Why do we care? Because if it’s preeclampsia the mother needs to be delivered immediately for her safety, while if it’s an SLE flare sometimes you can treat it and get the fetus to a more viable age. A 23-week-old baby isn’t at all likely to make it, but a 27-week-old could,” Dr. Bermas said.

The fact that the patient has thrombocytopenia isn’t helpful in making the distinction, since that feature is shared in common by SLE flares and preeclampsia. But the uric acid level is a useful clue.

It’s quite possible that much of the current guesswork in predicting preeclampsia and other adverse pregnancy outcomes in lupus patients will give way to reliable risk testing within the next several years. Investigators in the U.S. multicenter prospective PROMISSE (Predictors of Pregnancy Outcome: Biomarkers in APL Syndrome and SLE) study have reported that circulating levels of the angiogenic factors soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 and placental growth factor were abnormal as early as gestational weeks 12-15 in patients who went on to develop preeclampsia or other adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Indeed, monthly testing demonstrated that SLE patients in the top quartile for soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 at weeks 12-15 had an adjusted 17.3-fold greater likelihood of experiencing a severe adverse pregnancy outcome than did those in the lowest quartile. A high level had a positive predictive value of 61% and a negative predictive value of 93% (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jan;214[1]:108.e1-14). These findings are being further explored in ongoing studies.

“Hopefully, in another few years we’re going to be able to say early in pregnancy, ‘This person is set up to get preeclampsia.’ Maybe that will lead to better treatment as well,” Dr. Bermas said.

The risk of preeclampsia has been shown to be threefold higher in women with SLE than in the general population of pregnant women in a study of more than 16.7 million admissions for childbirth in the United States during a 4-year period. The SLE patients were also at 2.4-fold increased risk for preterm labor. Their risks of infection, thrombosis, thrombocytopenia, and transfusion were each three- to seven-fold higher as well (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Aug;199[2]:127.e1-16).

Dr. Bermas reported serving as a consultant to UCB.

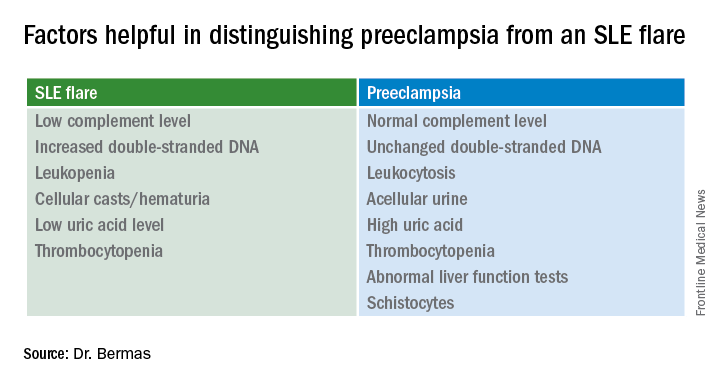

SNOWMASS, COLO. – No hard and fast test exists that would enable a physician to tell a flare of systemic lupus erythematosus from preeclampsia in a pregnant lupus patient who becomes hypertensive and ill, but there are highly useful clues, Bonnie L. Bermas, MD, said at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

“There is no perfect way of distinguishing between a lupus flare and preeclampsia. I’ve never walked away from the labor floor and said, ‘This is great – I know this is a lupus flare,’ or ‘I know this is preeclampsia.’ But you make your best guess as to which one it is, and that will inform your management,” explained Dr. Bermas, a rheumatologist and director of the clinical lupus program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Why do we care? Because if it’s preeclampsia the mother needs to be delivered immediately for her safety, while if it’s an SLE flare sometimes you can treat it and get the fetus to a more viable age. A 23-week-old baby isn’t at all likely to make it, but a 27-week-old could,” Dr. Bermas said.

The fact that the patient has thrombocytopenia isn’t helpful in making the distinction, since that feature is shared in common by SLE flares and preeclampsia. But the uric acid level is a useful clue.

It’s quite possible that much of the current guesswork in predicting preeclampsia and other adverse pregnancy outcomes in lupus patients will give way to reliable risk testing within the next several years. Investigators in the U.S. multicenter prospective PROMISSE (Predictors of Pregnancy Outcome: Biomarkers in APL Syndrome and SLE) study have reported that circulating levels of the angiogenic factors soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 and placental growth factor were abnormal as early as gestational weeks 12-15 in patients who went on to develop preeclampsia or other adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Indeed, monthly testing demonstrated that SLE patients in the top quartile for soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 at weeks 12-15 had an adjusted 17.3-fold greater likelihood of experiencing a severe adverse pregnancy outcome than did those in the lowest quartile. A high level had a positive predictive value of 61% and a negative predictive value of 93% (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jan;214[1]:108.e1-14). These findings are being further explored in ongoing studies.

“Hopefully, in another few years we’re going to be able to say early in pregnancy, ‘This person is set up to get preeclampsia.’ Maybe that will lead to better treatment as well,” Dr. Bermas said.

The risk of preeclampsia has been shown to be threefold higher in women with SLE than in the general population of pregnant women in a study of more than 16.7 million admissions for childbirth in the United States during a 4-year period. The SLE patients were also at 2.4-fold increased risk for preterm labor. Their risks of infection, thrombosis, thrombocytopenia, and transfusion were each three- to seven-fold higher as well (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Aug;199[2]:127.e1-16).

Dr. Bermas reported serving as a consultant to UCB.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE WINTER RHEUMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM