User login

Rise of a global scourge

The Great Pox, the French Disease, Cupid’s Disease – syphilis has had many names throughout history.

Why should we care about the history of syphilis? Surely syphilis has reached the status of a nonentity disease – in-and-out of the doctor’s office with a course of antibiotics and farewell to the problem. And on the surface, that is certainly true. For now. In the developed world. For those with access to reasonable health care.

But that is all the shiny surface of modern medical triumph. Despite successes in prevention throughout the late 20th and early 21st century, syphilis is making comeback. A growing reservoir of syphilis, often untreated, lies hidden by the invisibility of poorer nations and increasingly in the lower economic strata of the developed world. And the danger is increased by the rise of antibiotic-resistant strains of the disease.

Over the last decade, the European Union and several other high-income countries observed an increasing syphilis trend, according to a recent report by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. And in the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has expressed concern over “the rising tide of syphilis” and a “devastating surge in congenital syphilis.” Many reasons have been suggested for this resurgence of syphilis, including the prevalence of unprotected sex and the overall increase in multiple sexual partners in the sexually active population. This trend has been ascribed to a reduced fear of acquiring HIV from condomless sex because of the rise of antiretroviral therapies, which make HIV infection no longer a death sentence for those who have access to and can afford the drugs.

Men who have sex with men are the most affected population cited, which may in part be related to the trend in unprotected sex that has accompanied the decreasing fear of HIV. But in some countries, syphilis rates among heterosexual populations are on the increase as well. Even more troubling were the increases in syphilis diagnosed among pregnant women that were reported in high-income settings outside of the European Union, which led to increases in congenital syphilis infections.

According to a 2018 update on the global epidemiology of syphilis, each year an estimated 6 million new cases are diagnosed in people aged 15-49 years, with more than 300,000 fetal and neonatal deaths attributed to the disease. An additional 215,000 infants are at increased risk of early death because of prenatal infection.

For syphilis is indeed a nasty disease. But a remarkable one as well. It presents an almost textbook example of disease evolution and adaptation writ large. It is also a disease with equally remarkable properties – acute, systemic, latent, eruptive, and congenital in its various manifestations. As Sir William Osler, one of the brightest lights of medical education of his time, said in 1897: “I often tell my students that it [syphilis] is the only disease which they require to know thoroughly. Know syphilis in all its manifestations and relations, and all other things clinical will be added unto you.”

Syphilis is caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum and is generally acquired by sexual contact. Congenital syphilis infection occurs by transplacental transmission.

In its modern manifestation, the disease evolves through several stages – primary, secondary, and tertiary. Primary, noncongenital infection is characterized by a lesion. This chancre, as it is called, occurs at the original site of infection, typically between 10 days and 3 months after exposure. The chancre usually appears on the genitals, but given the variety of sexual behaviors, chancres can also occur on the rectum, tongue, pharynx, breast, and so on. The myth of only choosing “a clean partner,” one without visible lesions, is misleading because vaginal and rectal lesions may not be easy to spot yet still remain profoundly infectious.

The secondary stage of an untreated infection occurs 2-3 months after the onset of chancre, and results in multisystem involvement as the spirochetes spread through the bloodstream. Symptoms include skin rash (involving the palms and the soles of the feet) and potentially a variety of other dermatologic manifestations. Fever and swollen lymph nodes may also be present before the disease moves into a latent stage, in which no clinical symptoms are evident. Following this, tertiary syphilis can occur 10-30 years after the initial infection in about 30% of the untreated population, resulting in neurosyphilis, cardiovascular syphilis, or late benign syphilis. Disease progression in tertiary syphilis can lead to dementia, disfigurement, and death.

Sounds bad, doesn’t it? But what we’ve just recounted is the relatively benign disease that modern syphilis has become. Syphilis began as a sweeping, lethal epidemic in the late 15th century spreading dread across the world from the Americas to Europe and then to Asia at a speed equal to the fastest sailing ships of the era.

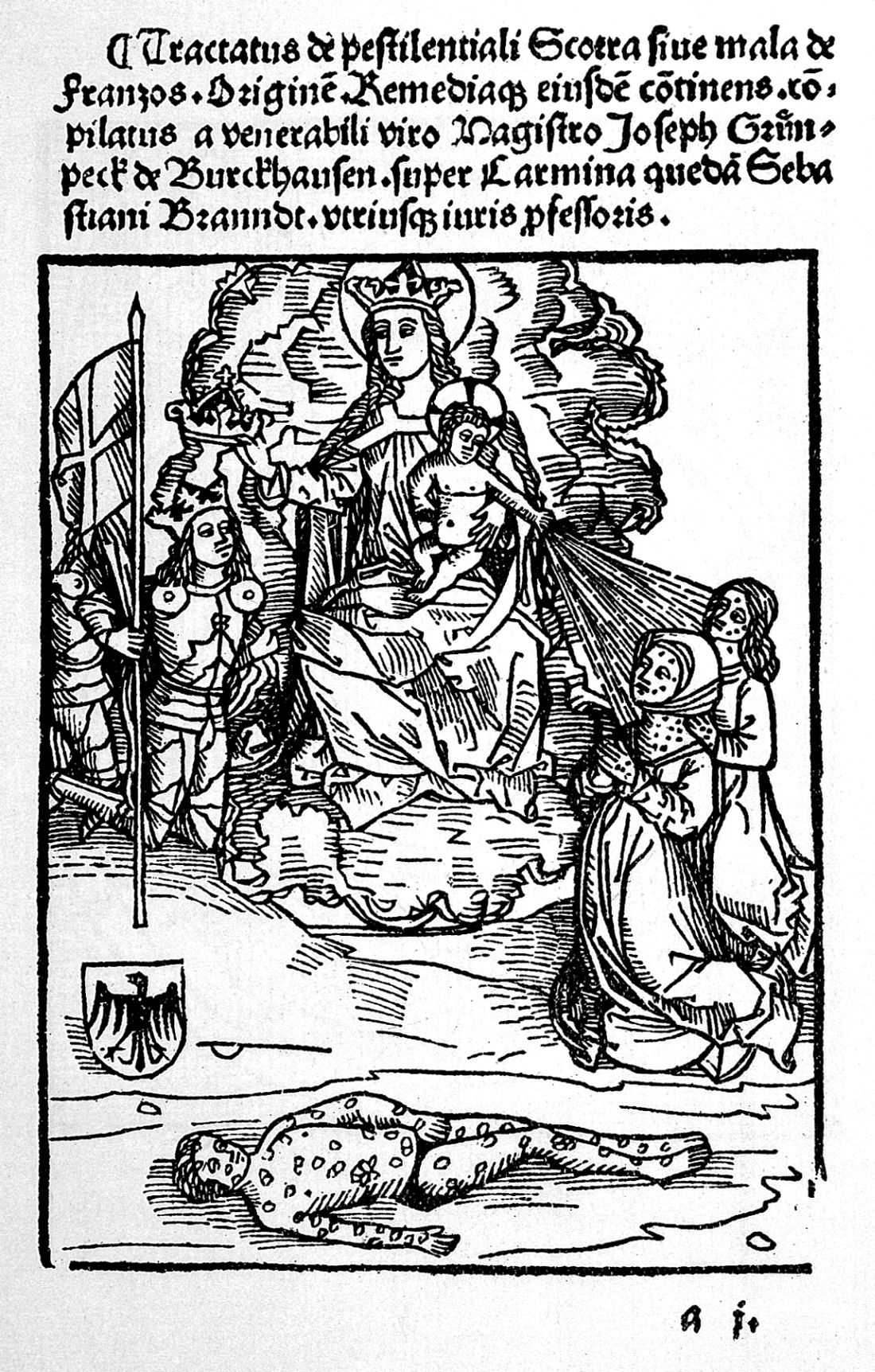

Syphilis first appeared in Naples in its epidemic form in 1495. Recent anthropological and historical consensus has suggested that syphilis, as we know it today, like tobacco, potatoes, and maize is a product of the Americas that was brought to the Old World by the intrepid exploits of one Christopher Columbus in 1493. Just as the Spanish inadvertently brought smallpox to devastate the population of the New World, Christopher Columbus appears to have brought epidemic syphilis to the Old World in an ironic twist of fate.

Ruy Diaz de Isla, one of two Spanish physicians present when Christopher Columbus returned from his first voyage to America, wrote in a manuscript that Pinzon de Palos, the pilot of Columbus, and also other members of the crew already suffered from symptoms of what was likely syphilis on their return from the New World

Although there has been some controversy regarding the origin of the syphilis epidemic, a recent molecular study using a large collection of pathogenic Treponema strains indicated that venereal syphilis arose relatively recently in human history, and that the closest related syphilis-causing strains were found in South America, providing support for the Columbian theory of syphilis’s origin.

Syphilis flamed across Europe like wildfire, lit by a series of small wars that started shortly after Columbus’s return. Soldiers throughout history have indulged themselves in activities well primed for the spread of venereal disease, and the doughty warriors of the late 15th century were no exception. And throughout the next 500-plus years, syphilis and war rode across the world in tandem, like the white and red horsemen of the Apocalypse.

In its initial launch, syphilis had the help of Charles VIII, the King of France, who had invaded Italy in early 1495 with an army of more than 30,000 mercenaries recruited from across Europe. His forces conquered Naples, which was primarily defended by Spanish mercenaries.

When Charles VIII broke up his army, “mercenaries, infected with a mysterious, serious disease, returned to their native lands or moved elsewhere to wage war, spreading the disease across Europe.” The “Great Pox” initially struck Italy, France, Germany, and Switzerland in 1495; then Holland and Greece in the following year, reaching England and Scotland by 1497; and then Hungary, Poland, and the Scandinavian countries by 1500.

As this period was the Age of Exploration, French, Dutch, and English sailors soon carried syphilis across the rest of an unsuspecting world, with the disease reaching India in 1498 before moving also to Africa and then throughout the rest of Asia in the early 16th century.

And yet, one of the most remarkable parts of the story is the rapid transformation of syphilis from a deadly virulent epidemic to a (comparatively) benign endemic status. Which will be the subject of my next posting.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner . He has a PhD in Plant Virology and a PhD in the History of Science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor at the Georgetown University School of Medicine, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular & Cellular Biology, Washington, DC.

Rise of a global scourge

Rise of a global scourge

The Great Pox, the French Disease, Cupid’s Disease – syphilis has had many names throughout history.

Why should we care about the history of syphilis? Surely syphilis has reached the status of a nonentity disease – in-and-out of the doctor’s office with a course of antibiotics and farewell to the problem. And on the surface, that is certainly true. For now. In the developed world. For those with access to reasonable health care.

But that is all the shiny surface of modern medical triumph. Despite successes in prevention throughout the late 20th and early 21st century, syphilis is making comeback. A growing reservoir of syphilis, often untreated, lies hidden by the invisibility of poorer nations and increasingly in the lower economic strata of the developed world. And the danger is increased by the rise of antibiotic-resistant strains of the disease.

Over the last decade, the European Union and several other high-income countries observed an increasing syphilis trend, according to a recent report by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. And in the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has expressed concern over “the rising tide of syphilis” and a “devastating surge in congenital syphilis.” Many reasons have been suggested for this resurgence of syphilis, including the prevalence of unprotected sex and the overall increase in multiple sexual partners in the sexually active population. This trend has been ascribed to a reduced fear of acquiring HIV from condomless sex because of the rise of antiretroviral therapies, which make HIV infection no longer a death sentence for those who have access to and can afford the drugs.

Men who have sex with men are the most affected population cited, which may in part be related to the trend in unprotected sex that has accompanied the decreasing fear of HIV. But in some countries, syphilis rates among heterosexual populations are on the increase as well. Even more troubling were the increases in syphilis diagnosed among pregnant women that were reported in high-income settings outside of the European Union, which led to increases in congenital syphilis infections.

According to a 2018 update on the global epidemiology of syphilis, each year an estimated 6 million new cases are diagnosed in people aged 15-49 years, with more than 300,000 fetal and neonatal deaths attributed to the disease. An additional 215,000 infants are at increased risk of early death because of prenatal infection.

For syphilis is indeed a nasty disease. But a remarkable one as well. It presents an almost textbook example of disease evolution and adaptation writ large. It is also a disease with equally remarkable properties – acute, systemic, latent, eruptive, and congenital in its various manifestations. As Sir William Osler, one of the brightest lights of medical education of his time, said in 1897: “I often tell my students that it [syphilis] is the only disease which they require to know thoroughly. Know syphilis in all its manifestations and relations, and all other things clinical will be added unto you.”

Syphilis is caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum and is generally acquired by sexual contact. Congenital syphilis infection occurs by transplacental transmission.

In its modern manifestation, the disease evolves through several stages – primary, secondary, and tertiary. Primary, noncongenital infection is characterized by a lesion. This chancre, as it is called, occurs at the original site of infection, typically between 10 days and 3 months after exposure. The chancre usually appears on the genitals, but given the variety of sexual behaviors, chancres can also occur on the rectum, tongue, pharynx, breast, and so on. The myth of only choosing “a clean partner,” one without visible lesions, is misleading because vaginal and rectal lesions may not be easy to spot yet still remain profoundly infectious.

The secondary stage of an untreated infection occurs 2-3 months after the onset of chancre, and results in multisystem involvement as the spirochetes spread through the bloodstream. Symptoms include skin rash (involving the palms and the soles of the feet) and potentially a variety of other dermatologic manifestations. Fever and swollen lymph nodes may also be present before the disease moves into a latent stage, in which no clinical symptoms are evident. Following this, tertiary syphilis can occur 10-30 years after the initial infection in about 30% of the untreated population, resulting in neurosyphilis, cardiovascular syphilis, or late benign syphilis. Disease progression in tertiary syphilis can lead to dementia, disfigurement, and death.

Sounds bad, doesn’t it? But what we’ve just recounted is the relatively benign disease that modern syphilis has become. Syphilis began as a sweeping, lethal epidemic in the late 15th century spreading dread across the world from the Americas to Europe and then to Asia at a speed equal to the fastest sailing ships of the era.

Syphilis first appeared in Naples in its epidemic form in 1495. Recent anthropological and historical consensus has suggested that syphilis, as we know it today, like tobacco, potatoes, and maize is a product of the Americas that was brought to the Old World by the intrepid exploits of one Christopher Columbus in 1493. Just as the Spanish inadvertently brought smallpox to devastate the population of the New World, Christopher Columbus appears to have brought epidemic syphilis to the Old World in an ironic twist of fate.

Ruy Diaz de Isla, one of two Spanish physicians present when Christopher Columbus returned from his first voyage to America, wrote in a manuscript that Pinzon de Palos, the pilot of Columbus, and also other members of the crew already suffered from symptoms of what was likely syphilis on their return from the New World

Although there has been some controversy regarding the origin of the syphilis epidemic, a recent molecular study using a large collection of pathogenic Treponema strains indicated that venereal syphilis arose relatively recently in human history, and that the closest related syphilis-causing strains were found in South America, providing support for the Columbian theory of syphilis’s origin.

Syphilis flamed across Europe like wildfire, lit by a series of small wars that started shortly after Columbus’s return. Soldiers throughout history have indulged themselves in activities well primed for the spread of venereal disease, and the doughty warriors of the late 15th century were no exception. And throughout the next 500-plus years, syphilis and war rode across the world in tandem, like the white and red horsemen of the Apocalypse.

In its initial launch, syphilis had the help of Charles VIII, the King of France, who had invaded Italy in early 1495 with an army of more than 30,000 mercenaries recruited from across Europe. His forces conquered Naples, which was primarily defended by Spanish mercenaries.

When Charles VIII broke up his army, “mercenaries, infected with a mysterious, serious disease, returned to their native lands or moved elsewhere to wage war, spreading the disease across Europe.” The “Great Pox” initially struck Italy, France, Germany, and Switzerland in 1495; then Holland and Greece in the following year, reaching England and Scotland by 1497; and then Hungary, Poland, and the Scandinavian countries by 1500.

As this period was the Age of Exploration, French, Dutch, and English sailors soon carried syphilis across the rest of an unsuspecting world, with the disease reaching India in 1498 before moving also to Africa and then throughout the rest of Asia in the early 16th century.

And yet, one of the most remarkable parts of the story is the rapid transformation of syphilis from a deadly virulent epidemic to a (comparatively) benign endemic status. Which will be the subject of my next posting.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner . He has a PhD in Plant Virology and a PhD in the History of Science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor at the Georgetown University School of Medicine, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular & Cellular Biology, Washington, DC.

The Great Pox, the French Disease, Cupid’s Disease – syphilis has had many names throughout history.

Why should we care about the history of syphilis? Surely syphilis has reached the status of a nonentity disease – in-and-out of the doctor’s office with a course of antibiotics and farewell to the problem. And on the surface, that is certainly true. For now. In the developed world. For those with access to reasonable health care.

But that is all the shiny surface of modern medical triumph. Despite successes in prevention throughout the late 20th and early 21st century, syphilis is making comeback. A growing reservoir of syphilis, often untreated, lies hidden by the invisibility of poorer nations and increasingly in the lower economic strata of the developed world. And the danger is increased by the rise of antibiotic-resistant strains of the disease.

Over the last decade, the European Union and several other high-income countries observed an increasing syphilis trend, according to a recent report by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. And in the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has expressed concern over “the rising tide of syphilis” and a “devastating surge in congenital syphilis.” Many reasons have been suggested for this resurgence of syphilis, including the prevalence of unprotected sex and the overall increase in multiple sexual partners in the sexually active population. This trend has been ascribed to a reduced fear of acquiring HIV from condomless sex because of the rise of antiretroviral therapies, which make HIV infection no longer a death sentence for those who have access to and can afford the drugs.

Men who have sex with men are the most affected population cited, which may in part be related to the trend in unprotected sex that has accompanied the decreasing fear of HIV. But in some countries, syphilis rates among heterosexual populations are on the increase as well. Even more troubling were the increases in syphilis diagnosed among pregnant women that were reported in high-income settings outside of the European Union, which led to increases in congenital syphilis infections.

According to a 2018 update on the global epidemiology of syphilis, each year an estimated 6 million new cases are diagnosed in people aged 15-49 years, with more than 300,000 fetal and neonatal deaths attributed to the disease. An additional 215,000 infants are at increased risk of early death because of prenatal infection.

For syphilis is indeed a nasty disease. But a remarkable one as well. It presents an almost textbook example of disease evolution and adaptation writ large. It is also a disease with equally remarkable properties – acute, systemic, latent, eruptive, and congenital in its various manifestations. As Sir William Osler, one of the brightest lights of medical education of his time, said in 1897: “I often tell my students that it [syphilis] is the only disease which they require to know thoroughly. Know syphilis in all its manifestations and relations, and all other things clinical will be added unto you.”

Syphilis is caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum and is generally acquired by sexual contact. Congenital syphilis infection occurs by transplacental transmission.

In its modern manifestation, the disease evolves through several stages – primary, secondary, and tertiary. Primary, noncongenital infection is characterized by a lesion. This chancre, as it is called, occurs at the original site of infection, typically between 10 days and 3 months after exposure. The chancre usually appears on the genitals, but given the variety of sexual behaviors, chancres can also occur on the rectum, tongue, pharynx, breast, and so on. The myth of only choosing “a clean partner,” one without visible lesions, is misleading because vaginal and rectal lesions may not be easy to spot yet still remain profoundly infectious.

The secondary stage of an untreated infection occurs 2-3 months after the onset of chancre, and results in multisystem involvement as the spirochetes spread through the bloodstream. Symptoms include skin rash (involving the palms and the soles of the feet) and potentially a variety of other dermatologic manifestations. Fever and swollen lymph nodes may also be present before the disease moves into a latent stage, in which no clinical symptoms are evident. Following this, tertiary syphilis can occur 10-30 years after the initial infection in about 30% of the untreated population, resulting in neurosyphilis, cardiovascular syphilis, or late benign syphilis. Disease progression in tertiary syphilis can lead to dementia, disfigurement, and death.

Sounds bad, doesn’t it? But what we’ve just recounted is the relatively benign disease that modern syphilis has become. Syphilis began as a sweeping, lethal epidemic in the late 15th century spreading dread across the world from the Americas to Europe and then to Asia at a speed equal to the fastest sailing ships of the era.

Syphilis first appeared in Naples in its epidemic form in 1495. Recent anthropological and historical consensus has suggested that syphilis, as we know it today, like tobacco, potatoes, and maize is a product of the Americas that was brought to the Old World by the intrepid exploits of one Christopher Columbus in 1493. Just as the Spanish inadvertently brought smallpox to devastate the population of the New World, Christopher Columbus appears to have brought epidemic syphilis to the Old World in an ironic twist of fate.

Ruy Diaz de Isla, one of two Spanish physicians present when Christopher Columbus returned from his first voyage to America, wrote in a manuscript that Pinzon de Palos, the pilot of Columbus, and also other members of the crew already suffered from symptoms of what was likely syphilis on their return from the New World

Although there has been some controversy regarding the origin of the syphilis epidemic, a recent molecular study using a large collection of pathogenic Treponema strains indicated that venereal syphilis arose relatively recently in human history, and that the closest related syphilis-causing strains were found in South America, providing support for the Columbian theory of syphilis’s origin.

Syphilis flamed across Europe like wildfire, lit by a series of small wars that started shortly after Columbus’s return. Soldiers throughout history have indulged themselves in activities well primed for the spread of venereal disease, and the doughty warriors of the late 15th century were no exception. And throughout the next 500-plus years, syphilis and war rode across the world in tandem, like the white and red horsemen of the Apocalypse.

In its initial launch, syphilis had the help of Charles VIII, the King of France, who had invaded Italy in early 1495 with an army of more than 30,000 mercenaries recruited from across Europe. His forces conquered Naples, which was primarily defended by Spanish mercenaries.

When Charles VIII broke up his army, “mercenaries, infected with a mysterious, serious disease, returned to their native lands or moved elsewhere to wage war, spreading the disease across Europe.” The “Great Pox” initially struck Italy, France, Germany, and Switzerland in 1495; then Holland and Greece in the following year, reaching England and Scotland by 1497; and then Hungary, Poland, and the Scandinavian countries by 1500.

As this period was the Age of Exploration, French, Dutch, and English sailors soon carried syphilis across the rest of an unsuspecting world, with the disease reaching India in 1498 before moving also to Africa and then throughout the rest of Asia in the early 16th century.

And yet, one of the most remarkable parts of the story is the rapid transformation of syphilis from a deadly virulent epidemic to a (comparatively) benign endemic status. Which will be the subject of my next posting.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner . He has a PhD in Plant Virology and a PhD in the History of Science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor at the Georgetown University School of Medicine, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular & Cellular Biology, Washington, DC.