User login

In recent years, hospitals and health systems have engaged in considerable efforts to reduce readmissions, in part due to financial incentives from the Medicare Hospital Readmission Reduction Program.1,2 Though efforts to improve transitions of care for all patients are laudable, risk for readmission is not distributed equally; a small subset of patients accounts for a disproportionate number of hospital readmissions.3 This phenomenon of frequently hospitalized patients is similar to that seen in other populations in which a small proportion of patients account for a majority of healthcare utilization.3,4

Recognizing that the current system of healthcare delivery does not meet the needs of this population, healthcare organizations have begun to implement interventions that supplement or redesign the system of care for frequently hospitalized patients.5-7 Descriptive reviews of ambulatory "high-need, high-cost" patients emphasize complex case management and interdisciplinary, team-based care.8,9 Prior systematic reviews of studies aimed at patients with high use of emergency care demonstrate improvements in social outcomes such as homelessness but mixed results in reducing emergency department (ED) use.10 However, we were unable to identify any prior reviews that evaluated interventions intended specifically for patients with frequent hospital admissions. Our objective in this systematic review was to characterize interventions for frequently admitted patients and determine whether these interventions decrease use of healthcare resources, improve health outcomes, and/or reduce costs.

METHODS

Literature Search

We registered our study protocol in the PROSPERO database. A librarian (L.O.) collaboratively developed the search strategies with other review authors (A.G., B.H., N.N.) and in January 2018 ran searches on "super users," "high utilizers," and similar terms in the following databases: PubMed MEDLINE, Embase (embase.com), and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) on the Wiley platform. The complete search strategies used are available in Appendix A.

We attempted to discover additional studies by searching the reference lists of key publications and contacted authors of relevant abstracts to determine whether studies had been published or were planned for peer-reviewed publication. We also contacted authors of included studies to locate additional studies meeting inclusion criteria.

Data Collection Process

Studies were eligible for inclusion in our review if they were (1) published in a peer-reviewed source, (2) defined a study population of patients frequently admitted to inpatient medical services, (3) evaluated an intervention targeting frequently hospitalized patients, and (4) included patients who were >18 years old and (5) admitted as inpatients on medical services. Of note, studies with patients admitted to psychiatric, obstetric, or surgical wards were not included, as the authors did not define these as "general medicine" units. Studies focused solely on an ambulatory population were similarly excluded. Given the heterogeneity of how studies defined frequently hospitalized patients, we did not establish a prespecified number of admissions for inclusion to ensure that we did not exclude interventions not meeting a strict set of criteria. The goal was not to examine interventions to reduce all readmissions, but rather, to look at patients who were recurrently hospitalized. Thus, patients had to be repeatedly admitted, but we let the studies define that usage explicitly.

Two members of a four-physician team (A.G., B.H., K.O., and N.N.) screened all initial results for eligibility through title and abstract review; potentially relevant articles were retained for full-text review to assess each study's eligibility. If a study's abstract did not clearly indicate whether inclusion criteria were met, we retained the article for full-text review. Two team members (A.G. and B.H.) independently reviewed the full text of each selected article to determine final inclusion in the study. The previously described inclusion criteria were again applied, and a final set of articles was identified for data extraction. Disagreements regarding inclusion in the final review (such as whether a study measured medical or psychiatric hospitalizations) were resolved through discussion among the entire four-physician review team to achieve consensus or, when required, by contacting authors of individual studies.

Data Abstraction and Risk of Bias Assessment

After selecting the final set of articles, we abstracted data using a tool developed by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Group.11 We then compiled study-level data into a single database for reporting. Extracted elements included study design, setting, patient characteristics, inclusion and exclusion criteria, control group identification, outcome measures, results, and length of follow-up. We also extracted individual characteristics of each intervention, including common intervention elements such as intervention setting, use of health information technology resources, and whether programs developed interdisciplinary care plans. We assessed the risk of bias of each study and the quality of studies using the Downs and Black Scale.12,13 Two team members (A.G. and B.H.) independently assessed the risk of bias for all nine studies, and differences were resolved by consensus. Due to the variation in the outcomes used, we were unable to conduct a meta-analysis.

RESULTS

Search Results

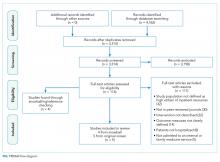

We found a total of 4,762 references in the three databases. After de-duplication using the EndNote software, there were 3,314 references to screen. We identified 116 studies for full-text review. Of those, we selected nine studies that met the criteria for this study (Figure). The most common reason for exclusion of an article for full-text review was that the patients studied were not defined as high utilizers of inpatient resources and were instead high-utilizers of ambulatory or emergency care (32 studies). We identified five of the included studies through the primary search and four through review of the references of the included papers.

Study Designs and Included Studies

Of the nine included studies, three were randomized controlled trials, three were controlled retrospective cohort studies, and three were uncontrolled pre-post studies. The key characteristics of each study are described in Table 1.14-22 The included studies had different definitions for patients who were high utilizers of hospital care. Eight used a "threshold" model that predicted future admissions using past patterns; these studies included patients with at least two admissions over a period of 6 to 12 months, although many had higher thresholds. Zulman et al. used a prediction algorithm to identify patients at risk of future admission. Four studies also included some measure of medical complexity, such as a certain number of chronic medical conditions;14,17,18,22 in contrast, Sledge et al. excluded the most complex and high-cost patients.20

All studies measured hospital admissions as a primary or a secondary outcome (Table 1). Although all studies demonstrated a reduction in hospital admissions following implementation, those with the greatest reductions did not have a control group.14,15,17 All three randomized controlled trials showed equal reductions in admission rates between the intervention and control groups.18,20,22 Among those specifically examining readmissions to the hospital, similar trends emerged, although one study (Plant et al.) found a nonsignificant decrease in hospital readmissions (17% reduction in 24 months, P = .07).18

In the secondary outcome analysis, six of the nine studies found nonsignificant reductions in ED admissions (Table 1). Four studies measured costs to the hospital or the local hospital system, though none examined costs to patients or payors. Studies estimated cost differently, including the use of estimated hospital costs,17,20 "facility patient costs" at the VA,22 and a combination of inpatient and ED costs.19 The latter study (Shah et al., which implemented complex case management services) was the only one to find a statistically significant decrease in mean cost per year pre- and postintervention ($20,298 versus $7,053, P < .001).19

Only one study measured the quality of life, finding no significant change in summary scores after the intervention compared with controls (93.4 versus 92, P = .32).21 Another study conducted at a VA clinic network found no difference in a patient activation scale following the intervention but found significantly increased satisfaction with overall VA care (3.16 versus 2.90, P = .04).22

Intervention Characteristics

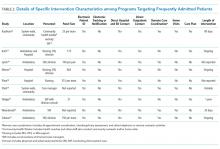

Intervention characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Although there was heterogeneity in study interventions, we identified common themes. Five of the nine interventions14-17,22 consisted of interdisciplinary teams that included community health workers, nurses, social workers, and physicians. Physicians were not included on every team; three interventions used them in direct care roles while two others contained physicians as advisors or in indirect roles. Intervention teams also had a variable level of involvement in a patient's care. Mercer et al. developed care plans for patients without physical interaction,17 whereas Zulman et al. recruited patients to a separate, intensive outpatient clinic outside the usual VA care team structure.22

The majority of interventions added direct services or support - most commonly, a social worker - to usual care processes. Patient panel sizes were relatively small, with most of the teams recruiting fewer than 150 patients per interdisciplinary team (range, 25-251). There was variation in the length of intervention, from 35 days of case management following hospital discharge to one year of intensive social work support to others of an indefinite length.15,17,22

Additional common themes included caring for patients across settings and incorporating information technology (IT) into workflows. Four interventions reported either interacting with patients in multiple settings, such as the hospital, clinic, and day hospital, ED, at home, or in the community.14,19,21,22 Two others16,20 interacted with patients only in the clinic but expanded the scope of a "traditional" primary care practice to include open scheduling, flexible appointment times, interdisciplinary visits, or outreach. In addition, IT resources assisted seven of the nine interventions, most commonly by identifying eligible patients via an electronic data tracking system or by automated alerts when their patients arrived at affiliated care locations.

Risk of Study Bias

We systematically assessed the risk of bias of the nine included studies (Appendix B). Using the scale published by Downs and Black, a point-based scale in which a score of 18 denotes a high-quality study, the studies in this review scored 15.55 on average (range 6-22, standard deviation [SD] 5.0). Four of the nine studies met the benchmark for high quality.12,13,18-22 The risk of bias was highest for measures of internal validity and confounding (range 0-5, mean 2.83, SD 1.94). The risk of bias was lowest for reporting measures (range 0-13, mean 7.40, SD 3.43).

DISCUSSION

Overall, studies reported mixed results related to readmissions and hospital utilization. While low-quality studies found reductions in hospital use over time, higher quality studies found similar reductions in utilization between the intervention and control groups. Johnson et al. showed that frequent hospitalization rates in a cohort of high-utilizer patients declined naturally over the course of 1-2 years; only 10% of individuals in the initial cohort remained "chronically hospitalized."6 Thus, expanding on these findings, the decline in hospitalizations over time as observed in some of the studies included in this review may be due to study patients being identified during a "spike" in utilization, which naturally decreases as the underlying medical or social factors driving rehospitalization resolve. Alternatively, reduction in hospitalizations may represent patients choosing to pursue care at other neighboring hospitals.23 No study included in our review evaluated healthcare use at institutions other than their study hospital or health system.

A striking theme of this review was the heterogeneity in each study's patient population. Thresholds for "high utilizers" varied from two hospital admissions in six months to two to three admissions in 30 days, to a combination of ED and hospital admissions, and to the use of predictive algorithms. A standard "case definition" for this population could guide future research, enabling comparison of outcomes across settings. Thus, we propose that future studies use three or more hospital admissions within six months when evaluating interventions targeting "high utilizer" patients. Although patients with one prior hospitalization in the past year are at elevated risk of rehospitalization,2 we feel that a higher "threshold" for this population will identify those at the highest strata of risk. Although predictive models may be better than "threshold" models, more work in validating these tools needs to be done before these can be put to use across settings.

In contrast to interventions designed to reduce readmissions for heart failure, pneumonia, or other diagnoses, frequently admitted patients do not encompass one disease or pathology pattern. Rinehart et al., in a study characterizing frequently admitted patients across a health system, identified five "subgroups" of patients, including those with (1) unstable housing, (2) comorbid medical and psychiatric illness, (3) severe complex medical illness, (4) dual-diagnosis psychiatric illness and substance abuse, and (5) a combination of medical and psychosocial barriers.25 In light of this population's heterogeneity, interventions may need to be flexible and tailored to the needs of individual patients, while simultaneously accounting for the capabilities and priorities of the health system. More specific and standardized interventions, targeting more homogenous groups, may be appropriate for populations defined according to pathology (such as heart failure or sickle cell disease).27

The components of interventions used for frequently hospitalized patients were diverse. Although most of the studies used interdisciplinary teams, they focused their efforts in a variety of settings, often crossing modern "boundaries of care" by providing direct or indirect input on care across healthcare settings. Care fragmentation probably plays an important role in the risk for readmissions in this population;9 as such, interventions that address factors across the continuum of care may be more likely to succeed.21 Notably, six of nine studies were conducted at academic medical centers and an additional one at a VA facility affiliated with an academic center. Only two were located at community-based clinical networks, indicating a theoretical potential for publication bias as academic centers may be more likely to study and publish their work. There may be successful interventions that have not been formally studied or published in the peer-reviewed literature.

The breadth of the outcome measures in the included studies raises questions about what metrics should define success. Although all the studies looked at hospital utilization and readmission, measure definitions varied. Importantly, a minority of studies investigated quality of life and patient satisfaction, outcomes that may ultimately provide a more fertile ground for inquiry and intervention. Two studies looked at quality of life as an outcome,19,22 but only one found that patients reported increased satisfaction despite showing nonsignificant reductions in hospital use.22 As shown in multiple prior studies, patient engagement is associated with increased satisfaction and can be associated with lower healthcare costs.26,27 Hibbard et al. have demonstrated that patient activation is a specific component of patient engagement and inversely impacts healthcare cost, with lower levels of patient activation showing increased costs in comparison to those patients more engaged in their own care.27 By focusing on changing patients' perceptions about their own health and involvement in their own care team as a partner, programs may be able to make a greater impact.

Our systematic review has several limitations. Although we used a search strategy designed to identify all relevant studies, reviewed the references of included studies, and contacted the authors, we identified only nine studies meeting our inclusion criteria. Four of the nine studies were identified from a manual review of references of the included studies, suggesting the possibility of a suboptimal search strategy. Although the inclusion of articles that appear in a check of reference lists is a valid step in the systematic review article acquisition process, we conducted a post hoc investigation of alternate search strategies. We checked the titles, abstracts, and subject headings of the four articles found by reference review to determine whether the original search could have been improved. An analysis of the articles revealed that the terminology used was not consistent with the super user/utilizer terminology we were operating under, and that the four articles used terms such as "high risk" and "complex patients," which are more generic than our targeted terms. Only on a careful read of the abstracts and full-text did we find that these articles were useful to the study. Adjusting the original search to include these general terms would have resulted in an unwieldy set of results; hence, we felt it best to adhere to our original search strategy.

Additional limitations include that only four of the nine included studies were at low risk of bias. In addition to limitations based on study design and small sample sizes, the interventions were often limited to a short period. In light of the multiple factors that contribute to frequent hospitalizations, some of which cannot be addressed quickly, studies to evaluate interventions for longer durations are warranted.

CONCLUSIONS

We found mixed results for the effect of interventions on outcomes for frequently hospitalized patients. While low-quality studies found reductions in hospital use over time, higher quality studies generally found similar reductions in utilization between the intervention and control groups. The range of definitions, interventions, and outcomes used for frequently hospitalized patients is partly explained by the heterogeneity of the population. More rigorous studies using multifaceted interventions that adapt to patients' unique needs should be conducted to assess the effect on outcomes relevant to both providers and patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like the thank Dr. Luke Hansen, Dr. Margaret Chapman, and McKay Barra for their support and contributions to this paper and to Northwestern Memorial Hospital's CHAMP (Complex High Admission Management Program).

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

The authors received no funding from external or internal sources for the completion of this project.

1. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html. Accessed March 23, 2018.

2. Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520-528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008. PubMed

3. Blumenthal D, Chernof B, Fulmer T, Lumpkin J, Selberg J. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients - an urgent priority. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):909-911. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1608511. PubMed

4. Gawande A. The Hot Spotters. The New Yorker. 2011 Jan: 40-51.

5. Szekendi MK, Williams MV, Carrier D, Hensley L, Thomas S, Cerese J. The characteristics of patients frequently admitted to academic medical centers in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(9):563-568. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2375. PubMed

6. Johnson TL, Rinehart DJ, Durfee J, et al. For many patients who use large amounts of health care services, the need is intense yet temporary. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(8):1312-1319. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1186. PubMed

7. Tinetti ME, Reuben DB. The hospital-dependent patient. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:694-697. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1315568. PubMed

8. Hong CS, Siegel AL, Ferris TG. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients: what makes for a successful care management program? Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2014;19:1-19. PubMed

9. Hochman M, Asch SM. Disruptive models in primary care: caring for high-needs, high-cost populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):392-397. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3945-2. PubMed

10. Althaus F1, Paroz S, Hugli O, et al. Effectiveness of interventions targeting frequent users of emergency departments: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2011 Jul;58(1):41-52.e42. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.007 PubMed

11. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). What study designs should be included in an EPOC review? EPOC resources for review authors. Available at:http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-resources-review-authors. Accessed March 23, 2018.

12. Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377-384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. PubMed

13. Goyal AA, Tur K, Mann J, Townsend W, Flanders SA, Chopra V. Do bedside visual tools improve patient and caregiver satisfaction? A systematic review of the literature. J Hosp Med 2017;12(11):930-936. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2871. PubMed

14. Kaufman S, Ali N, DeFiglio V, Craig K, Brenner J. Early efforts to target and enroll high-risk diabetic patients into urban community-based programs. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(2 Suppl):62S-70S. doi: 10.1177/1524839914535776. PubMed

15. Koch KL, Karafin MS, Simpson P, Field JJ. Intensive management of high-utilizing adults with sickle cell disease lowers admissions. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(3):215-219. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23912. PubMed

16. Lynch CS, Wajnberg A, Jervis R, et al. Implementation science workshop: a novel multidisciplinary primary care program to improve care and outcomes for super-utilizers. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(7):797-802. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3598-1. PubMed

17. Mercer T, Bae J, Kipnes J, Velazquez M, Thomas S, Setji N. The highest utilizers of care: individualized care plans to coordinate care, improve healthcare service utilization, and reduce costs at an academic tertiary care center. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(7):419-424. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2351. PubMed

18. Plant NA, Kelly PJ, Leeder SR, et al. Coordinated care versus standard care in hospital admissions of people with chronic illness: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2015;203(1):33-38. doi: 10.5694/mja14.01049. PubMed

19. Shah R, Chen C, O'Rourke S, Lee M, Mohanty SA, Abraham J. Evaluation of care management for the uninsured. Med Care. 2011;49(2):166-171. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182028e81. PubMed

20. Sledge WH, Brown KE, Levine JM, et al. A randomized trial of primary intensive care to reduce hospital admissions in patients with high utilization of inpatient services. Dis Manag. 2006;9(6):328-338. doi: 10.1089/dis.2006.9.328. PubMed

21. Weerahandi H, Basso Lipani M, Kalman J, et al. Effects of a psychosocial transitional care model on hospitalizations and cost of care for high utilizers. Soc Work Health Care. 2015;54(6):485-498. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2015.1040141. PubMed

22. Zulman DM, Ezeji-Okoye SC, Shaw JG, et al. Partnered research in healthcare delivery redesign for high-need, high-cost patients: development and feasibility of an Intensive Management Patient-Aligned Care Team (ImPACT). J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(4):861-869. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3022-7. PubMed

23. Mautner DB, Pang H, Brenner JC, et al. Generating hypotheses about care needs of high utilizers: lessons from patient interviews. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16 Suppl 1:S26-33. doi: 10.1089/pop.2013.0033. PubMed

24. Bodenheimer T. Strategies to reduce costs and improve care for high-utilizing Medicaid patients: Reflections on pioneering programs. Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc.;2013.

25. Rinehart DJ, Oronce C, Durfee MJ, et al. Identifying subgroups of adult superutilizers in an urban safety-net system using latent class analysis: implications for clinical practice. Med Care. 2018;56(1):e1-e9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000628. PubMed

26. Boutwell A, Kunst E, Sorin J, Shniffer A, Logozzo J, Woodhouse D. DSRIP-Medicaid Accelerated eXchange (MAX) Series Program: Improving Care for Super Utilizers. January 2017. https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/redesign/dsrip/pps_workshops/docs/2017-01_imp_care.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2018.

27. Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 Pt 1):1005-1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x PubMed

In recent years, hospitals and health systems have engaged in considerable efforts to reduce readmissions, in part due to financial incentives from the Medicare Hospital Readmission Reduction Program.1,2 Though efforts to improve transitions of care for all patients are laudable, risk for readmission is not distributed equally; a small subset of patients accounts for a disproportionate number of hospital readmissions.3 This phenomenon of frequently hospitalized patients is similar to that seen in other populations in which a small proportion of patients account for a majority of healthcare utilization.3,4

Recognizing that the current system of healthcare delivery does not meet the needs of this population, healthcare organizations have begun to implement interventions that supplement or redesign the system of care for frequently hospitalized patients.5-7 Descriptive reviews of ambulatory "high-need, high-cost" patients emphasize complex case management and interdisciplinary, team-based care.8,9 Prior systematic reviews of studies aimed at patients with high use of emergency care demonstrate improvements in social outcomes such as homelessness but mixed results in reducing emergency department (ED) use.10 However, we were unable to identify any prior reviews that evaluated interventions intended specifically for patients with frequent hospital admissions. Our objective in this systematic review was to characterize interventions for frequently admitted patients and determine whether these interventions decrease use of healthcare resources, improve health outcomes, and/or reduce costs.

METHODS

Literature Search

We registered our study protocol in the PROSPERO database. A librarian (L.O.) collaboratively developed the search strategies with other review authors (A.G., B.H., N.N.) and in January 2018 ran searches on "super users," "high utilizers," and similar terms in the following databases: PubMed MEDLINE, Embase (embase.com), and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) on the Wiley platform. The complete search strategies used are available in Appendix A.

We attempted to discover additional studies by searching the reference lists of key publications and contacted authors of relevant abstracts to determine whether studies had been published or were planned for peer-reviewed publication. We also contacted authors of included studies to locate additional studies meeting inclusion criteria.

Data Collection Process

Studies were eligible for inclusion in our review if they were (1) published in a peer-reviewed source, (2) defined a study population of patients frequently admitted to inpatient medical services, (3) evaluated an intervention targeting frequently hospitalized patients, and (4) included patients who were >18 years old and (5) admitted as inpatients on medical services. Of note, studies with patients admitted to psychiatric, obstetric, or surgical wards were not included, as the authors did not define these as "general medicine" units. Studies focused solely on an ambulatory population were similarly excluded. Given the heterogeneity of how studies defined frequently hospitalized patients, we did not establish a prespecified number of admissions for inclusion to ensure that we did not exclude interventions not meeting a strict set of criteria. The goal was not to examine interventions to reduce all readmissions, but rather, to look at patients who were recurrently hospitalized. Thus, patients had to be repeatedly admitted, but we let the studies define that usage explicitly.

Two members of a four-physician team (A.G., B.H., K.O., and N.N.) screened all initial results for eligibility through title and abstract review; potentially relevant articles were retained for full-text review to assess each study's eligibility. If a study's abstract did not clearly indicate whether inclusion criteria were met, we retained the article for full-text review. Two team members (A.G. and B.H.) independently reviewed the full text of each selected article to determine final inclusion in the study. The previously described inclusion criteria were again applied, and a final set of articles was identified for data extraction. Disagreements regarding inclusion in the final review (such as whether a study measured medical or psychiatric hospitalizations) were resolved through discussion among the entire four-physician review team to achieve consensus or, when required, by contacting authors of individual studies.

Data Abstraction and Risk of Bias Assessment

After selecting the final set of articles, we abstracted data using a tool developed by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Group.11 We then compiled study-level data into a single database for reporting. Extracted elements included study design, setting, patient characteristics, inclusion and exclusion criteria, control group identification, outcome measures, results, and length of follow-up. We also extracted individual characteristics of each intervention, including common intervention elements such as intervention setting, use of health information technology resources, and whether programs developed interdisciplinary care plans. We assessed the risk of bias of each study and the quality of studies using the Downs and Black Scale.12,13 Two team members (A.G. and B.H.) independently assessed the risk of bias for all nine studies, and differences were resolved by consensus. Due to the variation in the outcomes used, we were unable to conduct a meta-analysis.

RESULTS

Search Results

We found a total of 4,762 references in the three databases. After de-duplication using the EndNote software, there were 3,314 references to screen. We identified 116 studies for full-text review. Of those, we selected nine studies that met the criteria for this study (Figure). The most common reason for exclusion of an article for full-text review was that the patients studied were not defined as high utilizers of inpatient resources and were instead high-utilizers of ambulatory or emergency care (32 studies). We identified five of the included studies through the primary search and four through review of the references of the included papers.

Study Designs and Included Studies

Of the nine included studies, three were randomized controlled trials, three were controlled retrospective cohort studies, and three were uncontrolled pre-post studies. The key characteristics of each study are described in Table 1.14-22 The included studies had different definitions for patients who were high utilizers of hospital care. Eight used a "threshold" model that predicted future admissions using past patterns; these studies included patients with at least two admissions over a period of 6 to 12 months, although many had higher thresholds. Zulman et al. used a prediction algorithm to identify patients at risk of future admission. Four studies also included some measure of medical complexity, such as a certain number of chronic medical conditions;14,17,18,22 in contrast, Sledge et al. excluded the most complex and high-cost patients.20

All studies measured hospital admissions as a primary or a secondary outcome (Table 1). Although all studies demonstrated a reduction in hospital admissions following implementation, those with the greatest reductions did not have a control group.14,15,17 All three randomized controlled trials showed equal reductions in admission rates between the intervention and control groups.18,20,22 Among those specifically examining readmissions to the hospital, similar trends emerged, although one study (Plant et al.) found a nonsignificant decrease in hospital readmissions (17% reduction in 24 months, P = .07).18

In the secondary outcome analysis, six of the nine studies found nonsignificant reductions in ED admissions (Table 1). Four studies measured costs to the hospital or the local hospital system, though none examined costs to patients or payors. Studies estimated cost differently, including the use of estimated hospital costs,17,20 "facility patient costs" at the VA,22 and a combination of inpatient and ED costs.19 The latter study (Shah et al., which implemented complex case management services) was the only one to find a statistically significant decrease in mean cost per year pre- and postintervention ($20,298 versus $7,053, P < .001).19

Only one study measured the quality of life, finding no significant change in summary scores after the intervention compared with controls (93.4 versus 92, P = .32).21 Another study conducted at a VA clinic network found no difference in a patient activation scale following the intervention but found significantly increased satisfaction with overall VA care (3.16 versus 2.90, P = .04).22

Intervention Characteristics

Intervention characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Although there was heterogeneity in study interventions, we identified common themes. Five of the nine interventions14-17,22 consisted of interdisciplinary teams that included community health workers, nurses, social workers, and physicians. Physicians were not included on every team; three interventions used them in direct care roles while two others contained physicians as advisors or in indirect roles. Intervention teams also had a variable level of involvement in a patient's care. Mercer et al. developed care plans for patients without physical interaction,17 whereas Zulman et al. recruited patients to a separate, intensive outpatient clinic outside the usual VA care team structure.22

The majority of interventions added direct services or support - most commonly, a social worker - to usual care processes. Patient panel sizes were relatively small, with most of the teams recruiting fewer than 150 patients per interdisciplinary team (range, 25-251). There was variation in the length of intervention, from 35 days of case management following hospital discharge to one year of intensive social work support to others of an indefinite length.15,17,22

Additional common themes included caring for patients across settings and incorporating information technology (IT) into workflows. Four interventions reported either interacting with patients in multiple settings, such as the hospital, clinic, and day hospital, ED, at home, or in the community.14,19,21,22 Two others16,20 interacted with patients only in the clinic but expanded the scope of a "traditional" primary care practice to include open scheduling, flexible appointment times, interdisciplinary visits, or outreach. In addition, IT resources assisted seven of the nine interventions, most commonly by identifying eligible patients via an electronic data tracking system or by automated alerts when their patients arrived at affiliated care locations.

Risk of Study Bias

We systematically assessed the risk of bias of the nine included studies (Appendix B). Using the scale published by Downs and Black, a point-based scale in which a score of 18 denotes a high-quality study, the studies in this review scored 15.55 on average (range 6-22, standard deviation [SD] 5.0). Four of the nine studies met the benchmark for high quality.12,13,18-22 The risk of bias was highest for measures of internal validity and confounding (range 0-5, mean 2.83, SD 1.94). The risk of bias was lowest for reporting measures (range 0-13, mean 7.40, SD 3.43).

DISCUSSION

Overall, studies reported mixed results related to readmissions and hospital utilization. While low-quality studies found reductions in hospital use over time, higher quality studies found similar reductions in utilization between the intervention and control groups. Johnson et al. showed that frequent hospitalization rates in a cohort of high-utilizer patients declined naturally over the course of 1-2 years; only 10% of individuals in the initial cohort remained "chronically hospitalized."6 Thus, expanding on these findings, the decline in hospitalizations over time as observed in some of the studies included in this review may be due to study patients being identified during a "spike" in utilization, which naturally decreases as the underlying medical or social factors driving rehospitalization resolve. Alternatively, reduction in hospitalizations may represent patients choosing to pursue care at other neighboring hospitals.23 No study included in our review evaluated healthcare use at institutions other than their study hospital or health system.

A striking theme of this review was the heterogeneity in each study's patient population. Thresholds for "high utilizers" varied from two hospital admissions in six months to two to three admissions in 30 days, to a combination of ED and hospital admissions, and to the use of predictive algorithms. A standard "case definition" for this population could guide future research, enabling comparison of outcomes across settings. Thus, we propose that future studies use three or more hospital admissions within six months when evaluating interventions targeting "high utilizer" patients. Although patients with one prior hospitalization in the past year are at elevated risk of rehospitalization,2 we feel that a higher "threshold" for this population will identify those at the highest strata of risk. Although predictive models may be better than "threshold" models, more work in validating these tools needs to be done before these can be put to use across settings.

In contrast to interventions designed to reduce readmissions for heart failure, pneumonia, or other diagnoses, frequently admitted patients do not encompass one disease or pathology pattern. Rinehart et al., in a study characterizing frequently admitted patients across a health system, identified five "subgroups" of patients, including those with (1) unstable housing, (2) comorbid medical and psychiatric illness, (3) severe complex medical illness, (4) dual-diagnosis psychiatric illness and substance abuse, and (5) a combination of medical and psychosocial barriers.25 In light of this population's heterogeneity, interventions may need to be flexible and tailored to the needs of individual patients, while simultaneously accounting for the capabilities and priorities of the health system. More specific and standardized interventions, targeting more homogenous groups, may be appropriate for populations defined according to pathology (such as heart failure or sickle cell disease).27

The components of interventions used for frequently hospitalized patients were diverse. Although most of the studies used interdisciplinary teams, they focused their efforts in a variety of settings, often crossing modern "boundaries of care" by providing direct or indirect input on care across healthcare settings. Care fragmentation probably plays an important role in the risk for readmissions in this population;9 as such, interventions that address factors across the continuum of care may be more likely to succeed.21 Notably, six of nine studies were conducted at academic medical centers and an additional one at a VA facility affiliated with an academic center. Only two were located at community-based clinical networks, indicating a theoretical potential for publication bias as academic centers may be more likely to study and publish their work. There may be successful interventions that have not been formally studied or published in the peer-reviewed literature.

The breadth of the outcome measures in the included studies raises questions about what metrics should define success. Although all the studies looked at hospital utilization and readmission, measure definitions varied. Importantly, a minority of studies investigated quality of life and patient satisfaction, outcomes that may ultimately provide a more fertile ground for inquiry and intervention. Two studies looked at quality of life as an outcome,19,22 but only one found that patients reported increased satisfaction despite showing nonsignificant reductions in hospital use.22 As shown in multiple prior studies, patient engagement is associated with increased satisfaction and can be associated with lower healthcare costs.26,27 Hibbard et al. have demonstrated that patient activation is a specific component of patient engagement and inversely impacts healthcare cost, with lower levels of patient activation showing increased costs in comparison to those patients more engaged in their own care.27 By focusing on changing patients' perceptions about their own health and involvement in their own care team as a partner, programs may be able to make a greater impact.

Our systematic review has several limitations. Although we used a search strategy designed to identify all relevant studies, reviewed the references of included studies, and contacted the authors, we identified only nine studies meeting our inclusion criteria. Four of the nine studies were identified from a manual review of references of the included studies, suggesting the possibility of a suboptimal search strategy. Although the inclusion of articles that appear in a check of reference lists is a valid step in the systematic review article acquisition process, we conducted a post hoc investigation of alternate search strategies. We checked the titles, abstracts, and subject headings of the four articles found by reference review to determine whether the original search could have been improved. An analysis of the articles revealed that the terminology used was not consistent with the super user/utilizer terminology we were operating under, and that the four articles used terms such as "high risk" and "complex patients," which are more generic than our targeted terms. Only on a careful read of the abstracts and full-text did we find that these articles were useful to the study. Adjusting the original search to include these general terms would have resulted in an unwieldy set of results; hence, we felt it best to adhere to our original search strategy.

Additional limitations include that only four of the nine included studies were at low risk of bias. In addition to limitations based on study design and small sample sizes, the interventions were often limited to a short period. In light of the multiple factors that contribute to frequent hospitalizations, some of which cannot be addressed quickly, studies to evaluate interventions for longer durations are warranted.

CONCLUSIONS

We found mixed results for the effect of interventions on outcomes for frequently hospitalized patients. While low-quality studies found reductions in hospital use over time, higher quality studies generally found similar reductions in utilization between the intervention and control groups. The range of definitions, interventions, and outcomes used for frequently hospitalized patients is partly explained by the heterogeneity of the population. More rigorous studies using multifaceted interventions that adapt to patients' unique needs should be conducted to assess the effect on outcomes relevant to both providers and patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like the thank Dr. Luke Hansen, Dr. Margaret Chapman, and McKay Barra for their support and contributions to this paper and to Northwestern Memorial Hospital's CHAMP (Complex High Admission Management Program).

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

The authors received no funding from external or internal sources for the completion of this project.

In recent years, hospitals and health systems have engaged in considerable efforts to reduce readmissions, in part due to financial incentives from the Medicare Hospital Readmission Reduction Program.1,2 Though efforts to improve transitions of care for all patients are laudable, risk for readmission is not distributed equally; a small subset of patients accounts for a disproportionate number of hospital readmissions.3 This phenomenon of frequently hospitalized patients is similar to that seen in other populations in which a small proportion of patients account for a majority of healthcare utilization.3,4

Recognizing that the current system of healthcare delivery does not meet the needs of this population, healthcare organizations have begun to implement interventions that supplement or redesign the system of care for frequently hospitalized patients.5-7 Descriptive reviews of ambulatory "high-need, high-cost" patients emphasize complex case management and interdisciplinary, team-based care.8,9 Prior systematic reviews of studies aimed at patients with high use of emergency care demonstrate improvements in social outcomes such as homelessness but mixed results in reducing emergency department (ED) use.10 However, we were unable to identify any prior reviews that evaluated interventions intended specifically for patients with frequent hospital admissions. Our objective in this systematic review was to characterize interventions for frequently admitted patients and determine whether these interventions decrease use of healthcare resources, improve health outcomes, and/or reduce costs.

METHODS

Literature Search

We registered our study protocol in the PROSPERO database. A librarian (L.O.) collaboratively developed the search strategies with other review authors (A.G., B.H., N.N.) and in January 2018 ran searches on "super users," "high utilizers," and similar terms in the following databases: PubMed MEDLINE, Embase (embase.com), and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) on the Wiley platform. The complete search strategies used are available in Appendix A.

We attempted to discover additional studies by searching the reference lists of key publications and contacted authors of relevant abstracts to determine whether studies had been published or were planned for peer-reviewed publication. We also contacted authors of included studies to locate additional studies meeting inclusion criteria.

Data Collection Process

Studies were eligible for inclusion in our review if they were (1) published in a peer-reviewed source, (2) defined a study population of patients frequently admitted to inpatient medical services, (3) evaluated an intervention targeting frequently hospitalized patients, and (4) included patients who were >18 years old and (5) admitted as inpatients on medical services. Of note, studies with patients admitted to psychiatric, obstetric, or surgical wards were not included, as the authors did not define these as "general medicine" units. Studies focused solely on an ambulatory population were similarly excluded. Given the heterogeneity of how studies defined frequently hospitalized patients, we did not establish a prespecified number of admissions for inclusion to ensure that we did not exclude interventions not meeting a strict set of criteria. The goal was not to examine interventions to reduce all readmissions, but rather, to look at patients who were recurrently hospitalized. Thus, patients had to be repeatedly admitted, but we let the studies define that usage explicitly.

Two members of a four-physician team (A.G., B.H., K.O., and N.N.) screened all initial results for eligibility through title and abstract review; potentially relevant articles were retained for full-text review to assess each study's eligibility. If a study's abstract did not clearly indicate whether inclusion criteria were met, we retained the article for full-text review. Two team members (A.G. and B.H.) independently reviewed the full text of each selected article to determine final inclusion in the study. The previously described inclusion criteria were again applied, and a final set of articles was identified for data extraction. Disagreements regarding inclusion in the final review (such as whether a study measured medical or psychiatric hospitalizations) were resolved through discussion among the entire four-physician review team to achieve consensus or, when required, by contacting authors of individual studies.

Data Abstraction and Risk of Bias Assessment

After selecting the final set of articles, we abstracted data using a tool developed by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Group.11 We then compiled study-level data into a single database for reporting. Extracted elements included study design, setting, patient characteristics, inclusion and exclusion criteria, control group identification, outcome measures, results, and length of follow-up. We also extracted individual characteristics of each intervention, including common intervention elements such as intervention setting, use of health information technology resources, and whether programs developed interdisciplinary care plans. We assessed the risk of bias of each study and the quality of studies using the Downs and Black Scale.12,13 Two team members (A.G. and B.H.) independently assessed the risk of bias for all nine studies, and differences were resolved by consensus. Due to the variation in the outcomes used, we were unable to conduct a meta-analysis.

RESULTS

Search Results

We found a total of 4,762 references in the three databases. After de-duplication using the EndNote software, there were 3,314 references to screen. We identified 116 studies for full-text review. Of those, we selected nine studies that met the criteria for this study (Figure). The most common reason for exclusion of an article for full-text review was that the patients studied were not defined as high utilizers of inpatient resources and were instead high-utilizers of ambulatory or emergency care (32 studies). We identified five of the included studies through the primary search and four through review of the references of the included papers.

Study Designs and Included Studies

Of the nine included studies, three were randomized controlled trials, three were controlled retrospective cohort studies, and three were uncontrolled pre-post studies. The key characteristics of each study are described in Table 1.14-22 The included studies had different definitions for patients who were high utilizers of hospital care. Eight used a "threshold" model that predicted future admissions using past patterns; these studies included patients with at least two admissions over a period of 6 to 12 months, although many had higher thresholds. Zulman et al. used a prediction algorithm to identify patients at risk of future admission. Four studies also included some measure of medical complexity, such as a certain number of chronic medical conditions;14,17,18,22 in contrast, Sledge et al. excluded the most complex and high-cost patients.20

All studies measured hospital admissions as a primary or a secondary outcome (Table 1). Although all studies demonstrated a reduction in hospital admissions following implementation, those with the greatest reductions did not have a control group.14,15,17 All three randomized controlled trials showed equal reductions in admission rates between the intervention and control groups.18,20,22 Among those specifically examining readmissions to the hospital, similar trends emerged, although one study (Plant et al.) found a nonsignificant decrease in hospital readmissions (17% reduction in 24 months, P = .07).18

In the secondary outcome analysis, six of the nine studies found nonsignificant reductions in ED admissions (Table 1). Four studies measured costs to the hospital or the local hospital system, though none examined costs to patients or payors. Studies estimated cost differently, including the use of estimated hospital costs,17,20 "facility patient costs" at the VA,22 and a combination of inpatient and ED costs.19 The latter study (Shah et al., which implemented complex case management services) was the only one to find a statistically significant decrease in mean cost per year pre- and postintervention ($20,298 versus $7,053, P < .001).19

Only one study measured the quality of life, finding no significant change in summary scores after the intervention compared with controls (93.4 versus 92, P = .32).21 Another study conducted at a VA clinic network found no difference in a patient activation scale following the intervention but found significantly increased satisfaction with overall VA care (3.16 versus 2.90, P = .04).22

Intervention Characteristics

Intervention characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Although there was heterogeneity in study interventions, we identified common themes. Five of the nine interventions14-17,22 consisted of interdisciplinary teams that included community health workers, nurses, social workers, and physicians. Physicians were not included on every team; three interventions used them in direct care roles while two others contained physicians as advisors or in indirect roles. Intervention teams also had a variable level of involvement in a patient's care. Mercer et al. developed care plans for patients without physical interaction,17 whereas Zulman et al. recruited patients to a separate, intensive outpatient clinic outside the usual VA care team structure.22

The majority of interventions added direct services or support - most commonly, a social worker - to usual care processes. Patient panel sizes were relatively small, with most of the teams recruiting fewer than 150 patients per interdisciplinary team (range, 25-251). There was variation in the length of intervention, from 35 days of case management following hospital discharge to one year of intensive social work support to others of an indefinite length.15,17,22

Additional common themes included caring for patients across settings and incorporating information technology (IT) into workflows. Four interventions reported either interacting with patients in multiple settings, such as the hospital, clinic, and day hospital, ED, at home, or in the community.14,19,21,22 Two others16,20 interacted with patients only in the clinic but expanded the scope of a "traditional" primary care practice to include open scheduling, flexible appointment times, interdisciplinary visits, or outreach. In addition, IT resources assisted seven of the nine interventions, most commonly by identifying eligible patients via an electronic data tracking system or by automated alerts when their patients arrived at affiliated care locations.

Risk of Study Bias

We systematically assessed the risk of bias of the nine included studies (Appendix B). Using the scale published by Downs and Black, a point-based scale in which a score of 18 denotes a high-quality study, the studies in this review scored 15.55 on average (range 6-22, standard deviation [SD] 5.0). Four of the nine studies met the benchmark for high quality.12,13,18-22 The risk of bias was highest for measures of internal validity and confounding (range 0-5, mean 2.83, SD 1.94). The risk of bias was lowest for reporting measures (range 0-13, mean 7.40, SD 3.43).

DISCUSSION

Overall, studies reported mixed results related to readmissions and hospital utilization. While low-quality studies found reductions in hospital use over time, higher quality studies found similar reductions in utilization between the intervention and control groups. Johnson et al. showed that frequent hospitalization rates in a cohort of high-utilizer patients declined naturally over the course of 1-2 years; only 10% of individuals in the initial cohort remained "chronically hospitalized."6 Thus, expanding on these findings, the decline in hospitalizations over time as observed in some of the studies included in this review may be due to study patients being identified during a "spike" in utilization, which naturally decreases as the underlying medical or social factors driving rehospitalization resolve. Alternatively, reduction in hospitalizations may represent patients choosing to pursue care at other neighboring hospitals.23 No study included in our review evaluated healthcare use at institutions other than their study hospital or health system.

A striking theme of this review was the heterogeneity in each study's patient population. Thresholds for "high utilizers" varied from two hospital admissions in six months to two to three admissions in 30 days, to a combination of ED and hospital admissions, and to the use of predictive algorithms. A standard "case definition" for this population could guide future research, enabling comparison of outcomes across settings. Thus, we propose that future studies use three or more hospital admissions within six months when evaluating interventions targeting "high utilizer" patients. Although patients with one prior hospitalization in the past year are at elevated risk of rehospitalization,2 we feel that a higher "threshold" for this population will identify those at the highest strata of risk. Although predictive models may be better than "threshold" models, more work in validating these tools needs to be done before these can be put to use across settings.

In contrast to interventions designed to reduce readmissions for heart failure, pneumonia, or other diagnoses, frequently admitted patients do not encompass one disease or pathology pattern. Rinehart et al., in a study characterizing frequently admitted patients across a health system, identified five "subgroups" of patients, including those with (1) unstable housing, (2) comorbid medical and psychiatric illness, (3) severe complex medical illness, (4) dual-diagnosis psychiatric illness and substance abuse, and (5) a combination of medical and psychosocial barriers.25 In light of this population's heterogeneity, interventions may need to be flexible and tailored to the needs of individual patients, while simultaneously accounting for the capabilities and priorities of the health system. More specific and standardized interventions, targeting more homogenous groups, may be appropriate for populations defined according to pathology (such as heart failure or sickle cell disease).27

The components of interventions used for frequently hospitalized patients were diverse. Although most of the studies used interdisciplinary teams, they focused their efforts in a variety of settings, often crossing modern "boundaries of care" by providing direct or indirect input on care across healthcare settings. Care fragmentation probably plays an important role in the risk for readmissions in this population;9 as such, interventions that address factors across the continuum of care may be more likely to succeed.21 Notably, six of nine studies were conducted at academic medical centers and an additional one at a VA facility affiliated with an academic center. Only two were located at community-based clinical networks, indicating a theoretical potential for publication bias as academic centers may be more likely to study and publish their work. There may be successful interventions that have not been formally studied or published in the peer-reviewed literature.

The breadth of the outcome measures in the included studies raises questions about what metrics should define success. Although all the studies looked at hospital utilization and readmission, measure definitions varied. Importantly, a minority of studies investigated quality of life and patient satisfaction, outcomes that may ultimately provide a more fertile ground for inquiry and intervention. Two studies looked at quality of life as an outcome,19,22 but only one found that patients reported increased satisfaction despite showing nonsignificant reductions in hospital use.22 As shown in multiple prior studies, patient engagement is associated with increased satisfaction and can be associated with lower healthcare costs.26,27 Hibbard et al. have demonstrated that patient activation is a specific component of patient engagement and inversely impacts healthcare cost, with lower levels of patient activation showing increased costs in comparison to those patients more engaged in their own care.27 By focusing on changing patients' perceptions about their own health and involvement in their own care team as a partner, programs may be able to make a greater impact.

Our systematic review has several limitations. Although we used a search strategy designed to identify all relevant studies, reviewed the references of included studies, and contacted the authors, we identified only nine studies meeting our inclusion criteria. Four of the nine studies were identified from a manual review of references of the included studies, suggesting the possibility of a suboptimal search strategy. Although the inclusion of articles that appear in a check of reference lists is a valid step in the systematic review article acquisition process, we conducted a post hoc investigation of alternate search strategies. We checked the titles, abstracts, and subject headings of the four articles found by reference review to determine whether the original search could have been improved. An analysis of the articles revealed that the terminology used was not consistent with the super user/utilizer terminology we were operating under, and that the four articles used terms such as "high risk" and "complex patients," which are more generic than our targeted terms. Only on a careful read of the abstracts and full-text did we find that these articles were useful to the study. Adjusting the original search to include these general terms would have resulted in an unwieldy set of results; hence, we felt it best to adhere to our original search strategy.

Additional limitations include that only four of the nine included studies were at low risk of bias. In addition to limitations based on study design and small sample sizes, the interventions were often limited to a short period. In light of the multiple factors that contribute to frequent hospitalizations, some of which cannot be addressed quickly, studies to evaluate interventions for longer durations are warranted.

CONCLUSIONS

We found mixed results for the effect of interventions on outcomes for frequently hospitalized patients. While low-quality studies found reductions in hospital use over time, higher quality studies generally found similar reductions in utilization between the intervention and control groups. The range of definitions, interventions, and outcomes used for frequently hospitalized patients is partly explained by the heterogeneity of the population. More rigorous studies using multifaceted interventions that adapt to patients' unique needs should be conducted to assess the effect on outcomes relevant to both providers and patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like the thank Dr. Luke Hansen, Dr. Margaret Chapman, and McKay Barra for their support and contributions to this paper and to Northwestern Memorial Hospital's CHAMP (Complex High Admission Management Program).

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

The authors received no funding from external or internal sources for the completion of this project.

1. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html. Accessed March 23, 2018.

2. Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520-528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008. PubMed

3. Blumenthal D, Chernof B, Fulmer T, Lumpkin J, Selberg J. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients - an urgent priority. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):909-911. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1608511. PubMed

4. Gawande A. The Hot Spotters. The New Yorker. 2011 Jan: 40-51.

5. Szekendi MK, Williams MV, Carrier D, Hensley L, Thomas S, Cerese J. The characteristics of patients frequently admitted to academic medical centers in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(9):563-568. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2375. PubMed

6. Johnson TL, Rinehart DJ, Durfee J, et al. For many patients who use large amounts of health care services, the need is intense yet temporary. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(8):1312-1319. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1186. PubMed

7. Tinetti ME, Reuben DB. The hospital-dependent patient. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:694-697. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1315568. PubMed

8. Hong CS, Siegel AL, Ferris TG. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients: what makes for a successful care management program? Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2014;19:1-19. PubMed

9. Hochman M, Asch SM. Disruptive models in primary care: caring for high-needs, high-cost populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):392-397. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3945-2. PubMed

10. Althaus F1, Paroz S, Hugli O, et al. Effectiveness of interventions targeting frequent users of emergency departments: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2011 Jul;58(1):41-52.e42. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.007 PubMed

11. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). What study designs should be included in an EPOC review? EPOC resources for review authors. Available at:http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-resources-review-authors. Accessed March 23, 2018.

12. Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377-384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. PubMed

13. Goyal AA, Tur K, Mann J, Townsend W, Flanders SA, Chopra V. Do bedside visual tools improve patient and caregiver satisfaction? A systematic review of the literature. J Hosp Med 2017;12(11):930-936. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2871. PubMed

14. Kaufman S, Ali N, DeFiglio V, Craig K, Brenner J. Early efforts to target and enroll high-risk diabetic patients into urban community-based programs. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(2 Suppl):62S-70S. doi: 10.1177/1524839914535776. PubMed

15. Koch KL, Karafin MS, Simpson P, Field JJ. Intensive management of high-utilizing adults with sickle cell disease lowers admissions. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(3):215-219. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23912. PubMed

16. Lynch CS, Wajnberg A, Jervis R, et al. Implementation science workshop: a novel multidisciplinary primary care program to improve care and outcomes for super-utilizers. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(7):797-802. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3598-1. PubMed

17. Mercer T, Bae J, Kipnes J, Velazquez M, Thomas S, Setji N. The highest utilizers of care: individualized care plans to coordinate care, improve healthcare service utilization, and reduce costs at an academic tertiary care center. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(7):419-424. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2351. PubMed

18. Plant NA, Kelly PJ, Leeder SR, et al. Coordinated care versus standard care in hospital admissions of people with chronic illness: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2015;203(1):33-38. doi: 10.5694/mja14.01049. PubMed

19. Shah R, Chen C, O'Rourke S, Lee M, Mohanty SA, Abraham J. Evaluation of care management for the uninsured. Med Care. 2011;49(2):166-171. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182028e81. PubMed

20. Sledge WH, Brown KE, Levine JM, et al. A randomized trial of primary intensive care to reduce hospital admissions in patients with high utilization of inpatient services. Dis Manag. 2006;9(6):328-338. doi: 10.1089/dis.2006.9.328. PubMed

21. Weerahandi H, Basso Lipani M, Kalman J, et al. Effects of a psychosocial transitional care model on hospitalizations and cost of care for high utilizers. Soc Work Health Care. 2015;54(6):485-498. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2015.1040141. PubMed

22. Zulman DM, Ezeji-Okoye SC, Shaw JG, et al. Partnered research in healthcare delivery redesign for high-need, high-cost patients: development and feasibility of an Intensive Management Patient-Aligned Care Team (ImPACT). J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(4):861-869. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3022-7. PubMed

23. Mautner DB, Pang H, Brenner JC, et al. Generating hypotheses about care needs of high utilizers: lessons from patient interviews. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16 Suppl 1:S26-33. doi: 10.1089/pop.2013.0033. PubMed

24. Bodenheimer T. Strategies to reduce costs and improve care for high-utilizing Medicaid patients: Reflections on pioneering programs. Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc.;2013.

25. Rinehart DJ, Oronce C, Durfee MJ, et al. Identifying subgroups of adult superutilizers in an urban safety-net system using latent class analysis: implications for clinical practice. Med Care. 2018;56(1):e1-e9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000628. PubMed

26. Boutwell A, Kunst E, Sorin J, Shniffer A, Logozzo J, Woodhouse D. DSRIP-Medicaid Accelerated eXchange (MAX) Series Program: Improving Care for Super Utilizers. January 2017. https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/redesign/dsrip/pps_workshops/docs/2017-01_imp_care.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2018.

27. Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 Pt 1):1005-1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x PubMed

1. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html. Accessed March 23, 2018.

2. Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520-528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008. PubMed

3. Blumenthal D, Chernof B, Fulmer T, Lumpkin J, Selberg J. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients - an urgent priority. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):909-911. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1608511. PubMed

4. Gawande A. The Hot Spotters. The New Yorker. 2011 Jan: 40-51.

5. Szekendi MK, Williams MV, Carrier D, Hensley L, Thomas S, Cerese J. The characteristics of patients frequently admitted to academic medical centers in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(9):563-568. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2375. PubMed

6. Johnson TL, Rinehart DJ, Durfee J, et al. For many patients who use large amounts of health care services, the need is intense yet temporary. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(8):1312-1319. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1186. PubMed

7. Tinetti ME, Reuben DB. The hospital-dependent patient. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:694-697. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1315568. PubMed

8. Hong CS, Siegel AL, Ferris TG. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients: what makes for a successful care management program? Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2014;19:1-19. PubMed

9. Hochman M, Asch SM. Disruptive models in primary care: caring for high-needs, high-cost populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):392-397. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3945-2. PubMed

10. Althaus F1, Paroz S, Hugli O, et al. Effectiveness of interventions targeting frequent users of emergency departments: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2011 Jul;58(1):41-52.e42. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.007 PubMed

11. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). What study designs should be included in an EPOC review? EPOC resources for review authors. Available at:http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-resources-review-authors. Accessed March 23, 2018.

12. Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377-384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. PubMed

13. Goyal AA, Tur K, Mann J, Townsend W, Flanders SA, Chopra V. Do bedside visual tools improve patient and caregiver satisfaction? A systematic review of the literature. J Hosp Med 2017;12(11):930-936. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2871. PubMed

14. Kaufman S, Ali N, DeFiglio V, Craig K, Brenner J. Early efforts to target and enroll high-risk diabetic patients into urban community-based programs. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(2 Suppl):62S-70S. doi: 10.1177/1524839914535776. PubMed

15. Koch KL, Karafin MS, Simpson P, Field JJ. Intensive management of high-utilizing adults with sickle cell disease lowers admissions. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(3):215-219. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23912. PubMed

16. Lynch CS, Wajnberg A, Jervis R, et al. Implementation science workshop: a novel multidisciplinary primary care program to improve care and outcomes for super-utilizers. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(7):797-802. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3598-1. PubMed

17. Mercer T, Bae J, Kipnes J, Velazquez M, Thomas S, Setji N. The highest utilizers of care: individualized care plans to coordinate care, improve healthcare service utilization, and reduce costs at an academic tertiary care center. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(7):419-424. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2351. PubMed

18. Plant NA, Kelly PJ, Leeder SR, et al. Coordinated care versus standard care in hospital admissions of people with chronic illness: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2015;203(1):33-38. doi: 10.5694/mja14.01049. PubMed

19. Shah R, Chen C, O'Rourke S, Lee M, Mohanty SA, Abraham J. Evaluation of care management for the uninsured. Med Care. 2011;49(2):166-171. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182028e81. PubMed

20. Sledge WH, Brown KE, Levine JM, et al. A randomized trial of primary intensive care to reduce hospital admissions in patients with high utilization of inpatient services. Dis Manag. 2006;9(6):328-338. doi: 10.1089/dis.2006.9.328. PubMed

21. Weerahandi H, Basso Lipani M, Kalman J, et al. Effects of a psychosocial transitional care model on hospitalizations and cost of care for high utilizers. Soc Work Health Care. 2015;54(6):485-498. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2015.1040141. PubMed

22. Zulman DM, Ezeji-Okoye SC, Shaw JG, et al. Partnered research in healthcare delivery redesign for high-need, high-cost patients: development and feasibility of an Intensive Management Patient-Aligned Care Team (ImPACT). J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(4):861-869. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3022-7. PubMed

23. Mautner DB, Pang H, Brenner JC, et al. Generating hypotheses about care needs of high utilizers: lessons from patient interviews. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16 Suppl 1:S26-33. doi: 10.1089/pop.2013.0033. PubMed

24. Bodenheimer T. Strategies to reduce costs and improve care for high-utilizing Medicaid patients: Reflections on pioneering programs. Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc.;2013.

25. Rinehart DJ, Oronce C, Durfee MJ, et al. Identifying subgroups of adult superutilizers in an urban safety-net system using latent class analysis: implications for clinical practice. Med Care. 2018;56(1):e1-e9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000628. PubMed

26. Boutwell A, Kunst E, Sorin J, Shniffer A, Logozzo J, Woodhouse D. DSRIP-Medicaid Accelerated eXchange (MAX) Series Program: Improving Care for Super Utilizers. January 2017. https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/redesign/dsrip/pps_workshops/docs/2017-01_imp_care.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2018.

27. Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 Pt 1):1005-1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine