User login

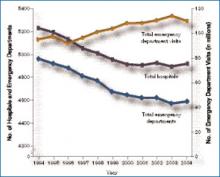

Emergency care in the U.S. has been called a system in crisis, and the data are startling. From 1994 to 2004, the number of hospitals and emergency departments (EDs) decreased, the latter by 9%, but the number of ED visits increased by more than 1 million annually.1 (See Figure 1, p. 17)

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics, between 40% and 50% of U.S. hospitals experience crowded conditions in the ED, with almost two-thirds of metropolitan EDs experiencing crowding at times.2

Hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians asked about their complex relationship—the good, the bad, and the not yet solved—praised their ability to work together.

“In general, our relationship with hospitalists has been fantastic,” says James Hoekstra, MD, president of the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. “To have physicians who are willing to take patients with a lot of different disease states that are not necessarily procedure oriented, don’t necessarily fit into a specific specialty, or are somewhat undifferentiated in their presentation—for us that is an absolute joy.”

The number of hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians might be said to be running in parallel, says Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, FACP, executive director of the hospitalist program and vice chair for clinical affairs and quality in the department of medicine at the University of California, Irvine. He tends to refer to this ratio as 30-30, meaning that, within a few years, there will be roughly 30,000 hospitalists, while there are currently that many emergency medicine physicians.3 In addition, emergency medicine and hospital medicine are site-based specialties, says Dr. Amin, so bridging their separateness is crucial to patient care.

“Aside from a small proportion of direct [patient] admissions,” says Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, chief of hospital medicine at the U. Mass. Medical Center in Worcester, “we are an extension of the ER, and the ER is an extension of us. We need to all be on the same page so that what’s said in the ER matches what happens on the floor, which matches what we send out to the primary [care physician].”

Optimizing patient flow is primarily a function of communication, says Marc Newquist, MD, FACEP, a hospitalist, an emergency medicine physician, and program director of the hospitalist division of The Schumacher Group in Lafayette, La. “The better that these communication systems can be standardized, the better hospitalists and their emergency medicine colleagues can promote a seamless integration between the two specialties as patients journey through their hospital stays,” he says.

“As medicine becomes more fragmented and hospital medicine does, let’s face it, fragment care,” adds Dr. Gundersen. “We also have to make sure that information flows from the primary-care physician who may send the patient to the ER. Everybody is a partner, and everybody needs to communicate back and forth and understand that if the ER wants to get someone admitted, timely communication with the hospitalist and understanding how the flow of the hospital works is really important.”

Interactions and Roles

“Far and away the most common type of interaction between hospitalists and ED docs is admissions,” says David M. Pressel, MD, PhD, director, Inpatient Service, General Pediatrics at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del. The next most common interaction will depend upon the institution and its style, but, primarily, interactions include consults, and—in some institutions—patient discharge.

Dr. Pressel works at a tertiary-care referral center where residents staff the ED and his unit. “But at a community hospital where you generally have ED medicine-trained docs—not pediatricians who have ED

medicine fellowships—they have less experience with pediatrics, so they may be more likely to consult us on a patient,” he says. The development of care pathways to facilitate care is another important interaction between emergency medicine physicians and hospitalists.

An example of a protocol development the hospitalist and the ED should do together, says Dr. Pressel, is when patients come in with certain symptoms that would indicate a possible communicable disease for which the patient might need special isolation on an inpatient unit. That issue may more likely be foremost in hospitalist’s mind, and he or she can perform an evaluation early to determine what isolation may be needed. If the hospitalist suspects a patient has varicella or active pulmonary tuberculosis, for instance, “those kinds of [isolation] rooms are limited,” says Dr. Pressel. “Hospitals don’t have a lot of them, so you have to make sure you’re getting beds assigned well.”

Our interviews say the major roles of the hospitalist in managing relationships with emergency medicine physicians involve professionalism. “The hospitalist needs to understand the needs of the ER physician in terms of the needs of the [overall] ER: timing, flow, and getting patients seen in a prompt manner,” says Dr. Gundersen. “There’s a give and take, and both sides need to understand the other side of the job to maximize that collegiality and to maximize that sense of teamwork.”

Dr. Gundersen, who works full time as a hospitalist and moonlights as an ED physician, says that “what at times the ED doesn’t realize is that the time it takes for them to do something in the ED is not the same as it takes for us to do something on the floor. If they order a CT scan in the ED, it happens right away. If they say, ‘You can just get the CT scan on the floor,’ well, we don’t have as much priority in terms of getting lab draws and diagnostic tests done as fast as they do.”

—Debra L. Burgy, MD, hospitalist, Abbott Northwestern Hospital, Minneapolis, Minn.

Stepping on toes is always a danger.

“One of the key things for the relationship is to realize that you’re not walking in the other person’s shoes,” says Dr. Pressel. “I’ve witnessed [situations] where a hospitalist on the receiving end scoffs at the management in the ED—either because, number one, the patient was perceived to be not sick enough to merit hospitalization according to the hospitalist, or, number two, because of over-workup and overdiagnosis or under-workup and under- or misdiagnosis.”

Both groups need to realize that the patient’s condition evolves over time. “What the ED saw three hours ago may not be what’s being seen now, and that’s true in the reverse,” he says. “If the patient looked great three hours ago, now [their condition may be life-threatening].”

Therefore, feedback between ED doctors and hospitalists should be provided in a “respectful, collegial, follow-up type of manner,” says Dr. Pressel. A beneficial means of communication involves feedback that is “telling it as an evolving story,” he says, as opposed to assuming the ED doctor is wrong. That is, “collaborating and adding to the story and the end diagnosis and recognizing that the ED doc’s job is not necessarily to make the final diagnosis.”

Dr. Pressel thinks it comes down to politeness, plain and simple. “I hope that when I miss something, someone will be kind enough to [be polite] to me, [to phrase it as] ‘I’m sure you were thinking of this but the clues looked this way and we went on to do further evaluation.’ ”

That kind of interaction happens all the time, he says. “And ultimately it’s best for the patient, number one, because everybody learns that way, and, number two, if you make yourself obnoxious with your colleagues, they’re not necessarily going to want to call you.”

The Nature of the Beast

Most interactions with their ED colleagues go smoothly, our hospitalists say, but sometimes there are bumps in the road—most often involving flow and the transfer of care.

Jason R. Orlinick, MD, PhD, chief, Section of Hospital Medicine at Norwalk Hospital, Conn., and clinical instructor of medicine at Yale University (New Haven, Conn.), probably represents the bulk of his hospitalist colleagues when he says he and the emergency medicine physicians with whom he works have a cordial relationship overall. But “there is always some level of tension between the hospitalists and the emergency department—at least at the institutions I’ve been at. To some extent, it depends on the mentality of the ED docs where you’re working.”

Debra L. Burgy, MD, a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis, puts it this way: “The interface between hospitalists and the ED is sometimes tense because the ED physicians are regularly bombarded with patients, which is completely unpredictable, and they do not have adequate support staff, such as social workers and psychiatric assessment workers, to create a safe disposition for patients who could otherwise go home.

“The path of least resistance, and the least time-consuming route, is to admit patients. The chain reaction continues with the hospitalist service being overwhelmed.”

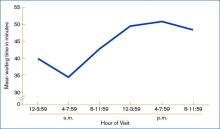

It is common for the ED to get a large volume of patients in the afternoon, our hospitalists remark. (See Figure 2, left) “We sometimes get hit with this huge bolus of patients,” Dr. Gundersen says. The biggest challenges involve “promptly identifying those patients who are identified for admission and maintaining a more open communication because when we get three, four, five admissions at once, we have difficulty working down that backlog.”

In the medical residency program at Dr. Orlinick’s institution, the bolus phenomenon can overwhelm residents’ and attendings’ capacities to see patients in a timely manner. “Unfortunately, we’ve not had a lot of success with that,” he says, and recently, his institution approached the hospitalists to work on a solution.

The timing of handoffs represents a large part of the breakdown in patient flow. “This is because of the ED physician who works until 4 p.m. or 6 p.m. and then tries to get all their patients whom they’re not sending home admitted right away before [the hospitalists] go off service,” Dr. Gundersen says. “It’s not uncommon that I get called or paged every three minutes—if I don’t answer right away—because they are trying to get someone admitted seconds after they call. The ER needs the beds, we haven’t been able to discharge the patients, everything gets bottlenecked.”

Although Dr. Gundersen recognizes that this problem is unavoidable at times, he suggests it would help “if the ED physicians were cognizant that there may be just one or two hospitalists who are admitting for the day, and giving them five admissions all at once, for instance, is going to take time to get through.”

On the other side, “Hospitalists rely on ED physicians to have the patient worked up and know which service they belong to,” explains Dr. Gundersen. “Succinct transfer of care is [paramount] so that critical information is brought to the attention of the accepting physician.” For the most part, he says, his ED colleagues do a good job.

Because the ED is always in a rush to get patients admitted and a disposition made, “there is the tendency to hamstring what’s happening on the floor. I think that big downstream effect from everything that begins in the ER transitions through the patient’s whole length of stay in the hospital,” says Dr. Gundersen.

All the interviewed hospitalists realize that the hospitalists and ED physicians need to have an understanding of what the other group faces. “We have to be understanding of the ER position that there are a lot of patients to be seen, and they’re trying to do the best they can in that period of time,” says Dr. Gundersen. A 2006 study revealed that interruptions within the ED were prevalent and diverse in nature and—on average—there was an interruption every nine and 14 minutes, respectively, for the attending emergency medicine physicians and residents.5

“And ED physicians have to realize that whatever patient they give to us, we then deal with,” says Dr. Gundersen, “and we [continue] to deal with all the issues, moving them through tests and studies [and] getting them discharged, so sometimes there are delays on both ends. It’s just the nature of the beast.”

A Sense of Control

The benefits of maintaining collegiality with ED physicians go beyond the norm, says Jeff Glasheen, MD, director of both the hospital medicine program and inpatient clinical services in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver Health Sciences Center. Dr. Glasheen has conducted some research on burnout—mostly in residents.6-7

“One of the main things that leads to burnout is lack of control and feeling like you don’t have control over your daily job,” he says. “One of the things that comes out of this relationship with the ER is that it’s no longer like someone’s just dumping on us. They’re very reasonable when we say, ‘That sounds like somebody who could go home; let me come down and see the patient, and let’s see if we can get this patient discharged.’ You begin to feel like you have control over your day, control over the patients who are admitted to you, and—quite honestly—it’s more fun. That kind of professional interaction is hard to put a price on, but I think it’s priceless.”TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Kellermann AL. Crisis in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006 Sep 28;355(13):1300-1303.

- Burt CW, McCaig LF. Staffing, capacity, and ambulance diversion in emergency departments: United States, 2003-04. Adv Data. 2006 Sep 27;(376):1-23. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad376.pdf. Last accessed April 10, 2007.

- Freed DH. Hospitalists: evolution, evidence, and eventualities. Health Care Manag. 2004 Jul-Sep;23(3):238-256;1-38.

- McCaig LF, Burt CW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2003 emergency department summary. Adv Data. 2005;(358):1-38. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad358.pdf. Last accessed April 10, 2007.

- Laxmisan A, Hakimzada F, Sayan OR, et al. The multitasking clinician: decision-making and cognitive demand during and after team handoffs in emergency care. Int J Med Inform. 2006 Oct 21. [Epub ahead of print.]

- Gopal RK, Carreira F, Baker WA, et al. Internal medicine residents reject “longer and gentler” training. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Jan;22(1):102-106.

- Gopal R, Glasheen JJ, Miyoshi TJ, et al. Burnout and internal medicine resident work-hour restrictions. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Dec 12-26;165(22):2595-2600. Comment in Arch Intern Med. 2005 Dec 12-26; 165(22):2561-2562. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Jul 10;166(13):1423; author reply 1423-1425.

Emergency care in the U.S. has been called a system in crisis, and the data are startling. From 1994 to 2004, the number of hospitals and emergency departments (EDs) decreased, the latter by 9%, but the number of ED visits increased by more than 1 million annually.1 (See Figure 1, p. 17)

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics, between 40% and 50% of U.S. hospitals experience crowded conditions in the ED, with almost two-thirds of metropolitan EDs experiencing crowding at times.2

Hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians asked about their complex relationship—the good, the bad, and the not yet solved—praised their ability to work together.

“In general, our relationship with hospitalists has been fantastic,” says James Hoekstra, MD, president of the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. “To have physicians who are willing to take patients with a lot of different disease states that are not necessarily procedure oriented, don’t necessarily fit into a specific specialty, or are somewhat undifferentiated in their presentation—for us that is an absolute joy.”

The number of hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians might be said to be running in parallel, says Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, FACP, executive director of the hospitalist program and vice chair for clinical affairs and quality in the department of medicine at the University of California, Irvine. He tends to refer to this ratio as 30-30, meaning that, within a few years, there will be roughly 30,000 hospitalists, while there are currently that many emergency medicine physicians.3 In addition, emergency medicine and hospital medicine are site-based specialties, says Dr. Amin, so bridging their separateness is crucial to patient care.

“Aside from a small proportion of direct [patient] admissions,” says Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, chief of hospital medicine at the U. Mass. Medical Center in Worcester, “we are an extension of the ER, and the ER is an extension of us. We need to all be on the same page so that what’s said in the ER matches what happens on the floor, which matches what we send out to the primary [care physician].”

Optimizing patient flow is primarily a function of communication, says Marc Newquist, MD, FACEP, a hospitalist, an emergency medicine physician, and program director of the hospitalist division of The Schumacher Group in Lafayette, La. “The better that these communication systems can be standardized, the better hospitalists and their emergency medicine colleagues can promote a seamless integration between the two specialties as patients journey through their hospital stays,” he says.

“As medicine becomes more fragmented and hospital medicine does, let’s face it, fragment care,” adds Dr. Gundersen. “We also have to make sure that information flows from the primary-care physician who may send the patient to the ER. Everybody is a partner, and everybody needs to communicate back and forth and understand that if the ER wants to get someone admitted, timely communication with the hospitalist and understanding how the flow of the hospital works is really important.”

Interactions and Roles

“Far and away the most common type of interaction between hospitalists and ED docs is admissions,” says David M. Pressel, MD, PhD, director, Inpatient Service, General Pediatrics at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del. The next most common interaction will depend upon the institution and its style, but, primarily, interactions include consults, and—in some institutions—patient discharge.

Dr. Pressel works at a tertiary-care referral center where residents staff the ED and his unit. “But at a community hospital where you generally have ED medicine-trained docs—not pediatricians who have ED

medicine fellowships—they have less experience with pediatrics, so they may be more likely to consult us on a patient,” he says. The development of care pathways to facilitate care is another important interaction between emergency medicine physicians and hospitalists.

An example of a protocol development the hospitalist and the ED should do together, says Dr. Pressel, is when patients come in with certain symptoms that would indicate a possible communicable disease for which the patient might need special isolation on an inpatient unit. That issue may more likely be foremost in hospitalist’s mind, and he or she can perform an evaluation early to determine what isolation may be needed. If the hospitalist suspects a patient has varicella or active pulmonary tuberculosis, for instance, “those kinds of [isolation] rooms are limited,” says Dr. Pressel. “Hospitals don’t have a lot of them, so you have to make sure you’re getting beds assigned well.”

Our interviews say the major roles of the hospitalist in managing relationships with emergency medicine physicians involve professionalism. “The hospitalist needs to understand the needs of the ER physician in terms of the needs of the [overall] ER: timing, flow, and getting patients seen in a prompt manner,” says Dr. Gundersen. “There’s a give and take, and both sides need to understand the other side of the job to maximize that collegiality and to maximize that sense of teamwork.”

Dr. Gundersen, who works full time as a hospitalist and moonlights as an ED physician, says that “what at times the ED doesn’t realize is that the time it takes for them to do something in the ED is not the same as it takes for us to do something on the floor. If they order a CT scan in the ED, it happens right away. If they say, ‘You can just get the CT scan on the floor,’ well, we don’t have as much priority in terms of getting lab draws and diagnostic tests done as fast as they do.”

—Debra L. Burgy, MD, hospitalist, Abbott Northwestern Hospital, Minneapolis, Minn.

Stepping on toes is always a danger.

“One of the key things for the relationship is to realize that you’re not walking in the other person’s shoes,” says Dr. Pressel. “I’ve witnessed [situations] where a hospitalist on the receiving end scoffs at the management in the ED—either because, number one, the patient was perceived to be not sick enough to merit hospitalization according to the hospitalist, or, number two, because of over-workup and overdiagnosis or under-workup and under- or misdiagnosis.”

Both groups need to realize that the patient’s condition evolves over time. “What the ED saw three hours ago may not be what’s being seen now, and that’s true in the reverse,” he says. “If the patient looked great three hours ago, now [their condition may be life-threatening].”

Therefore, feedback between ED doctors and hospitalists should be provided in a “respectful, collegial, follow-up type of manner,” says Dr. Pressel. A beneficial means of communication involves feedback that is “telling it as an evolving story,” he says, as opposed to assuming the ED doctor is wrong. That is, “collaborating and adding to the story and the end diagnosis and recognizing that the ED doc’s job is not necessarily to make the final diagnosis.”

Dr. Pressel thinks it comes down to politeness, plain and simple. “I hope that when I miss something, someone will be kind enough to [be polite] to me, [to phrase it as] ‘I’m sure you were thinking of this but the clues looked this way and we went on to do further evaluation.’ ”

That kind of interaction happens all the time, he says. “And ultimately it’s best for the patient, number one, because everybody learns that way, and, number two, if you make yourself obnoxious with your colleagues, they’re not necessarily going to want to call you.”

The Nature of the Beast

Most interactions with their ED colleagues go smoothly, our hospitalists say, but sometimes there are bumps in the road—most often involving flow and the transfer of care.

Jason R. Orlinick, MD, PhD, chief, Section of Hospital Medicine at Norwalk Hospital, Conn., and clinical instructor of medicine at Yale University (New Haven, Conn.), probably represents the bulk of his hospitalist colleagues when he says he and the emergency medicine physicians with whom he works have a cordial relationship overall. But “there is always some level of tension between the hospitalists and the emergency department—at least at the institutions I’ve been at. To some extent, it depends on the mentality of the ED docs where you’re working.”

Debra L. Burgy, MD, a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis, puts it this way: “The interface between hospitalists and the ED is sometimes tense because the ED physicians are regularly bombarded with patients, which is completely unpredictable, and they do not have adequate support staff, such as social workers and psychiatric assessment workers, to create a safe disposition for patients who could otherwise go home.

“The path of least resistance, and the least time-consuming route, is to admit patients. The chain reaction continues with the hospitalist service being overwhelmed.”

It is common for the ED to get a large volume of patients in the afternoon, our hospitalists remark. (See Figure 2, left) “We sometimes get hit with this huge bolus of patients,” Dr. Gundersen says. The biggest challenges involve “promptly identifying those patients who are identified for admission and maintaining a more open communication because when we get three, four, five admissions at once, we have difficulty working down that backlog.”

In the medical residency program at Dr. Orlinick’s institution, the bolus phenomenon can overwhelm residents’ and attendings’ capacities to see patients in a timely manner. “Unfortunately, we’ve not had a lot of success with that,” he says, and recently, his institution approached the hospitalists to work on a solution.

The timing of handoffs represents a large part of the breakdown in patient flow. “This is because of the ED physician who works until 4 p.m. or 6 p.m. and then tries to get all their patients whom they’re not sending home admitted right away before [the hospitalists] go off service,” Dr. Gundersen says. “It’s not uncommon that I get called or paged every three minutes—if I don’t answer right away—because they are trying to get someone admitted seconds after they call. The ER needs the beds, we haven’t been able to discharge the patients, everything gets bottlenecked.”

Although Dr. Gundersen recognizes that this problem is unavoidable at times, he suggests it would help “if the ED physicians were cognizant that there may be just one or two hospitalists who are admitting for the day, and giving them five admissions all at once, for instance, is going to take time to get through.”

On the other side, “Hospitalists rely on ED physicians to have the patient worked up and know which service they belong to,” explains Dr. Gundersen. “Succinct transfer of care is [paramount] so that critical information is brought to the attention of the accepting physician.” For the most part, he says, his ED colleagues do a good job.

Because the ED is always in a rush to get patients admitted and a disposition made, “there is the tendency to hamstring what’s happening on the floor. I think that big downstream effect from everything that begins in the ER transitions through the patient’s whole length of stay in the hospital,” says Dr. Gundersen.

All the interviewed hospitalists realize that the hospitalists and ED physicians need to have an understanding of what the other group faces. “We have to be understanding of the ER position that there are a lot of patients to be seen, and they’re trying to do the best they can in that period of time,” says Dr. Gundersen. A 2006 study revealed that interruptions within the ED were prevalent and diverse in nature and—on average—there was an interruption every nine and 14 minutes, respectively, for the attending emergency medicine physicians and residents.5

“And ED physicians have to realize that whatever patient they give to us, we then deal with,” says Dr. Gundersen, “and we [continue] to deal with all the issues, moving them through tests and studies [and] getting them discharged, so sometimes there are delays on both ends. It’s just the nature of the beast.”

A Sense of Control

The benefits of maintaining collegiality with ED physicians go beyond the norm, says Jeff Glasheen, MD, director of both the hospital medicine program and inpatient clinical services in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver Health Sciences Center. Dr. Glasheen has conducted some research on burnout—mostly in residents.6-7

“One of the main things that leads to burnout is lack of control and feeling like you don’t have control over your daily job,” he says. “One of the things that comes out of this relationship with the ER is that it’s no longer like someone’s just dumping on us. They’re very reasonable when we say, ‘That sounds like somebody who could go home; let me come down and see the patient, and let’s see if we can get this patient discharged.’ You begin to feel like you have control over your day, control over the patients who are admitted to you, and—quite honestly—it’s more fun. That kind of professional interaction is hard to put a price on, but I think it’s priceless.”TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Kellermann AL. Crisis in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006 Sep 28;355(13):1300-1303.

- Burt CW, McCaig LF. Staffing, capacity, and ambulance diversion in emergency departments: United States, 2003-04. Adv Data. 2006 Sep 27;(376):1-23. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad376.pdf. Last accessed April 10, 2007.

- Freed DH. Hospitalists: evolution, evidence, and eventualities. Health Care Manag. 2004 Jul-Sep;23(3):238-256;1-38.

- McCaig LF, Burt CW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2003 emergency department summary. Adv Data. 2005;(358):1-38. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad358.pdf. Last accessed April 10, 2007.

- Laxmisan A, Hakimzada F, Sayan OR, et al. The multitasking clinician: decision-making and cognitive demand during and after team handoffs in emergency care. Int J Med Inform. 2006 Oct 21. [Epub ahead of print.]

- Gopal RK, Carreira F, Baker WA, et al. Internal medicine residents reject “longer and gentler” training. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Jan;22(1):102-106.

- Gopal R, Glasheen JJ, Miyoshi TJ, et al. Burnout and internal medicine resident work-hour restrictions. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Dec 12-26;165(22):2595-2600. Comment in Arch Intern Med. 2005 Dec 12-26; 165(22):2561-2562. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Jul 10;166(13):1423; author reply 1423-1425.

Emergency care in the U.S. has been called a system in crisis, and the data are startling. From 1994 to 2004, the number of hospitals and emergency departments (EDs) decreased, the latter by 9%, but the number of ED visits increased by more than 1 million annually.1 (See Figure 1, p. 17)

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics, between 40% and 50% of U.S. hospitals experience crowded conditions in the ED, with almost two-thirds of metropolitan EDs experiencing crowding at times.2

Hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians asked about their complex relationship—the good, the bad, and the not yet solved—praised their ability to work together.

“In general, our relationship with hospitalists has been fantastic,” says James Hoekstra, MD, president of the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. “To have physicians who are willing to take patients with a lot of different disease states that are not necessarily procedure oriented, don’t necessarily fit into a specific specialty, or are somewhat undifferentiated in their presentation—for us that is an absolute joy.”

The number of hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians might be said to be running in parallel, says Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, FACP, executive director of the hospitalist program and vice chair for clinical affairs and quality in the department of medicine at the University of California, Irvine. He tends to refer to this ratio as 30-30, meaning that, within a few years, there will be roughly 30,000 hospitalists, while there are currently that many emergency medicine physicians.3 In addition, emergency medicine and hospital medicine are site-based specialties, says Dr. Amin, so bridging their separateness is crucial to patient care.

“Aside from a small proportion of direct [patient] admissions,” says Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, chief of hospital medicine at the U. Mass. Medical Center in Worcester, “we are an extension of the ER, and the ER is an extension of us. We need to all be on the same page so that what’s said in the ER matches what happens on the floor, which matches what we send out to the primary [care physician].”

Optimizing patient flow is primarily a function of communication, says Marc Newquist, MD, FACEP, a hospitalist, an emergency medicine physician, and program director of the hospitalist division of The Schumacher Group in Lafayette, La. “The better that these communication systems can be standardized, the better hospitalists and their emergency medicine colleagues can promote a seamless integration between the two specialties as patients journey through their hospital stays,” he says.

“As medicine becomes more fragmented and hospital medicine does, let’s face it, fragment care,” adds Dr. Gundersen. “We also have to make sure that information flows from the primary-care physician who may send the patient to the ER. Everybody is a partner, and everybody needs to communicate back and forth and understand that if the ER wants to get someone admitted, timely communication with the hospitalist and understanding how the flow of the hospital works is really important.”

Interactions and Roles

“Far and away the most common type of interaction between hospitalists and ED docs is admissions,” says David M. Pressel, MD, PhD, director, Inpatient Service, General Pediatrics at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del. The next most common interaction will depend upon the institution and its style, but, primarily, interactions include consults, and—in some institutions—patient discharge.

Dr. Pressel works at a tertiary-care referral center where residents staff the ED and his unit. “But at a community hospital where you generally have ED medicine-trained docs—not pediatricians who have ED

medicine fellowships—they have less experience with pediatrics, so they may be more likely to consult us on a patient,” he says. The development of care pathways to facilitate care is another important interaction between emergency medicine physicians and hospitalists.

An example of a protocol development the hospitalist and the ED should do together, says Dr. Pressel, is when patients come in with certain symptoms that would indicate a possible communicable disease for which the patient might need special isolation on an inpatient unit. That issue may more likely be foremost in hospitalist’s mind, and he or she can perform an evaluation early to determine what isolation may be needed. If the hospitalist suspects a patient has varicella or active pulmonary tuberculosis, for instance, “those kinds of [isolation] rooms are limited,” says Dr. Pressel. “Hospitals don’t have a lot of them, so you have to make sure you’re getting beds assigned well.”

Our interviews say the major roles of the hospitalist in managing relationships with emergency medicine physicians involve professionalism. “The hospitalist needs to understand the needs of the ER physician in terms of the needs of the [overall] ER: timing, flow, and getting patients seen in a prompt manner,” says Dr. Gundersen. “There’s a give and take, and both sides need to understand the other side of the job to maximize that collegiality and to maximize that sense of teamwork.”

Dr. Gundersen, who works full time as a hospitalist and moonlights as an ED physician, says that “what at times the ED doesn’t realize is that the time it takes for them to do something in the ED is not the same as it takes for us to do something on the floor. If they order a CT scan in the ED, it happens right away. If they say, ‘You can just get the CT scan on the floor,’ well, we don’t have as much priority in terms of getting lab draws and diagnostic tests done as fast as they do.”

—Debra L. Burgy, MD, hospitalist, Abbott Northwestern Hospital, Minneapolis, Minn.

Stepping on toes is always a danger.

“One of the key things for the relationship is to realize that you’re not walking in the other person’s shoes,” says Dr. Pressel. “I’ve witnessed [situations] where a hospitalist on the receiving end scoffs at the management in the ED—either because, number one, the patient was perceived to be not sick enough to merit hospitalization according to the hospitalist, or, number two, because of over-workup and overdiagnosis or under-workup and under- or misdiagnosis.”

Both groups need to realize that the patient’s condition evolves over time. “What the ED saw three hours ago may not be what’s being seen now, and that’s true in the reverse,” he says. “If the patient looked great three hours ago, now [their condition may be life-threatening].”

Therefore, feedback between ED doctors and hospitalists should be provided in a “respectful, collegial, follow-up type of manner,” says Dr. Pressel. A beneficial means of communication involves feedback that is “telling it as an evolving story,” he says, as opposed to assuming the ED doctor is wrong. That is, “collaborating and adding to the story and the end diagnosis and recognizing that the ED doc’s job is not necessarily to make the final diagnosis.”

Dr. Pressel thinks it comes down to politeness, plain and simple. “I hope that when I miss something, someone will be kind enough to [be polite] to me, [to phrase it as] ‘I’m sure you were thinking of this but the clues looked this way and we went on to do further evaluation.’ ”

That kind of interaction happens all the time, he says. “And ultimately it’s best for the patient, number one, because everybody learns that way, and, number two, if you make yourself obnoxious with your colleagues, they’re not necessarily going to want to call you.”

The Nature of the Beast

Most interactions with their ED colleagues go smoothly, our hospitalists say, but sometimes there are bumps in the road—most often involving flow and the transfer of care.

Jason R. Orlinick, MD, PhD, chief, Section of Hospital Medicine at Norwalk Hospital, Conn., and clinical instructor of medicine at Yale University (New Haven, Conn.), probably represents the bulk of his hospitalist colleagues when he says he and the emergency medicine physicians with whom he works have a cordial relationship overall. But “there is always some level of tension between the hospitalists and the emergency department—at least at the institutions I’ve been at. To some extent, it depends on the mentality of the ED docs where you’re working.”

Debra L. Burgy, MD, a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis, puts it this way: “The interface between hospitalists and the ED is sometimes tense because the ED physicians are regularly bombarded with patients, which is completely unpredictable, and they do not have adequate support staff, such as social workers and psychiatric assessment workers, to create a safe disposition for patients who could otherwise go home.

“The path of least resistance, and the least time-consuming route, is to admit patients. The chain reaction continues with the hospitalist service being overwhelmed.”

It is common for the ED to get a large volume of patients in the afternoon, our hospitalists remark. (See Figure 2, left) “We sometimes get hit with this huge bolus of patients,” Dr. Gundersen says. The biggest challenges involve “promptly identifying those patients who are identified for admission and maintaining a more open communication because when we get three, four, five admissions at once, we have difficulty working down that backlog.”

In the medical residency program at Dr. Orlinick’s institution, the bolus phenomenon can overwhelm residents’ and attendings’ capacities to see patients in a timely manner. “Unfortunately, we’ve not had a lot of success with that,” he says, and recently, his institution approached the hospitalists to work on a solution.

The timing of handoffs represents a large part of the breakdown in patient flow. “This is because of the ED physician who works until 4 p.m. or 6 p.m. and then tries to get all their patients whom they’re not sending home admitted right away before [the hospitalists] go off service,” Dr. Gundersen says. “It’s not uncommon that I get called or paged every three minutes—if I don’t answer right away—because they are trying to get someone admitted seconds after they call. The ER needs the beds, we haven’t been able to discharge the patients, everything gets bottlenecked.”

Although Dr. Gundersen recognizes that this problem is unavoidable at times, he suggests it would help “if the ED physicians were cognizant that there may be just one or two hospitalists who are admitting for the day, and giving them five admissions all at once, for instance, is going to take time to get through.”

On the other side, “Hospitalists rely on ED physicians to have the patient worked up and know which service they belong to,” explains Dr. Gundersen. “Succinct transfer of care is [paramount] so that critical information is brought to the attention of the accepting physician.” For the most part, he says, his ED colleagues do a good job.

Because the ED is always in a rush to get patients admitted and a disposition made, “there is the tendency to hamstring what’s happening on the floor. I think that big downstream effect from everything that begins in the ER transitions through the patient’s whole length of stay in the hospital,” says Dr. Gundersen.

All the interviewed hospitalists realize that the hospitalists and ED physicians need to have an understanding of what the other group faces. “We have to be understanding of the ER position that there are a lot of patients to be seen, and they’re trying to do the best they can in that period of time,” says Dr. Gundersen. A 2006 study revealed that interruptions within the ED were prevalent and diverse in nature and—on average—there was an interruption every nine and 14 minutes, respectively, for the attending emergency medicine physicians and residents.5

“And ED physicians have to realize that whatever patient they give to us, we then deal with,” says Dr. Gundersen, “and we [continue] to deal with all the issues, moving them through tests and studies [and] getting them discharged, so sometimes there are delays on both ends. It’s just the nature of the beast.”

A Sense of Control

The benefits of maintaining collegiality with ED physicians go beyond the norm, says Jeff Glasheen, MD, director of both the hospital medicine program and inpatient clinical services in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver Health Sciences Center. Dr. Glasheen has conducted some research on burnout—mostly in residents.6-7

“One of the main things that leads to burnout is lack of control and feeling like you don’t have control over your daily job,” he says. “One of the things that comes out of this relationship with the ER is that it’s no longer like someone’s just dumping on us. They’re very reasonable when we say, ‘That sounds like somebody who could go home; let me come down and see the patient, and let’s see if we can get this patient discharged.’ You begin to feel like you have control over your day, control over the patients who are admitted to you, and—quite honestly—it’s more fun. That kind of professional interaction is hard to put a price on, but I think it’s priceless.”TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Kellermann AL. Crisis in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006 Sep 28;355(13):1300-1303.

- Burt CW, McCaig LF. Staffing, capacity, and ambulance diversion in emergency departments: United States, 2003-04. Adv Data. 2006 Sep 27;(376):1-23. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad376.pdf. Last accessed April 10, 2007.

- Freed DH. Hospitalists: evolution, evidence, and eventualities. Health Care Manag. 2004 Jul-Sep;23(3):238-256;1-38.

- McCaig LF, Burt CW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2003 emergency department summary. Adv Data. 2005;(358):1-38. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad358.pdf. Last accessed April 10, 2007.

- Laxmisan A, Hakimzada F, Sayan OR, et al. The multitasking clinician: decision-making and cognitive demand during and after team handoffs in emergency care. Int J Med Inform. 2006 Oct 21. [Epub ahead of print.]

- Gopal RK, Carreira F, Baker WA, et al. Internal medicine residents reject “longer and gentler” training. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Jan;22(1):102-106.

- Gopal R, Glasheen JJ, Miyoshi TJ, et al. Burnout and internal medicine resident work-hour restrictions. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Dec 12-26;165(22):2595-2600. Comment in Arch Intern Med. 2005 Dec 12-26; 165(22):2561-2562. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Jul 10;166(13):1423; author reply 1423-1425.