User login

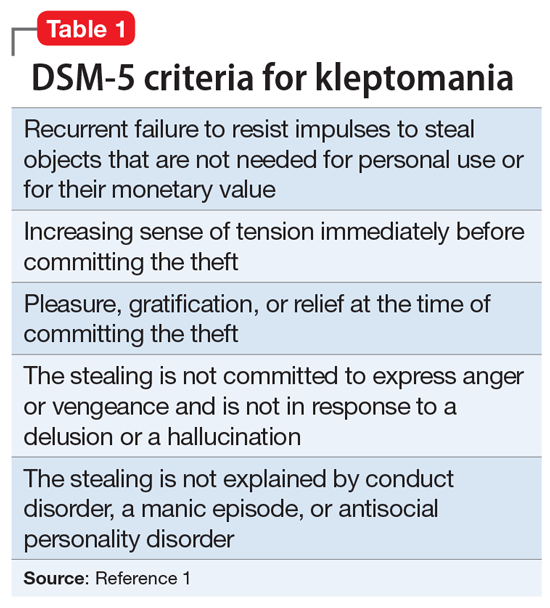

Kleptomania is characterized by a recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects that are not needed for personal use or their monetary value.1 It is a rare disorder; an estimated 0.3% to 0.6% of the general population meet DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania (Table 1).1 Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence and is more common among females than males (3:1).1 Although DSM-5 does not outline how long symptoms need to be present for patients to meet the diagnostic criteria, the disorder may persist for years, even when patients face legal consequences.1

Due to the clinical ambiguities surrounding kleptomania, it remains one of psychiatry’s most poorly understood diagnoses2 and regularly goes undiagnosed and untreated. Here we provide 4 tips for better diagnosis and treatment of this condition.

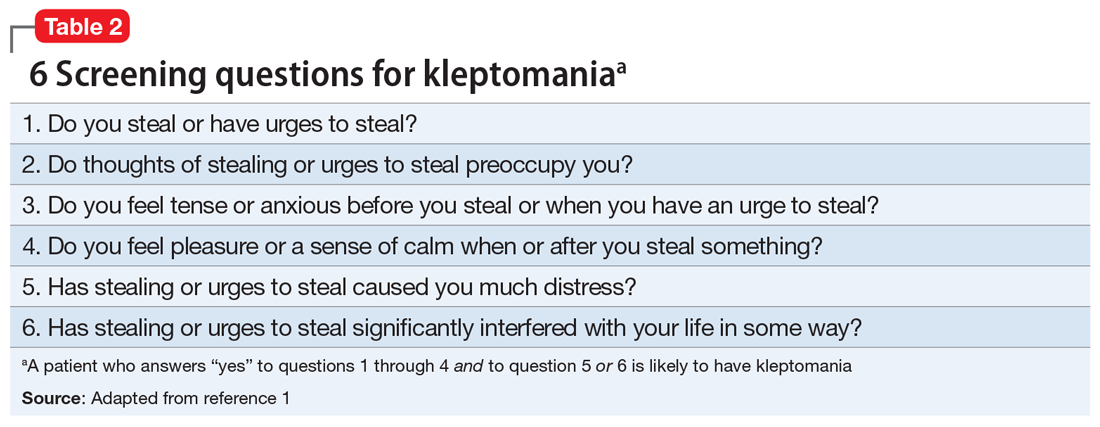

1. Screen for kleptomania in patients with other psychiatric disorders because kleptomania often is comorbid with other mental illnesses. Patients who present for evaluation of a mood disorder, substance use, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, impulse control disorders, conduct disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder should be screened for kleptomania.1,3,4 Patients with kleptomania often are reluctant to discuss their stealing because they may experience humiliation and guilt related to theft.1,4 Undiagnosed kleptomania can be fatal; a study of suicide attempts in 107 individuals with kleptomania found that 92% of the patients attributed their attempt specifically to kleptomania.5 Table 21 offers screening questions based on the DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania.

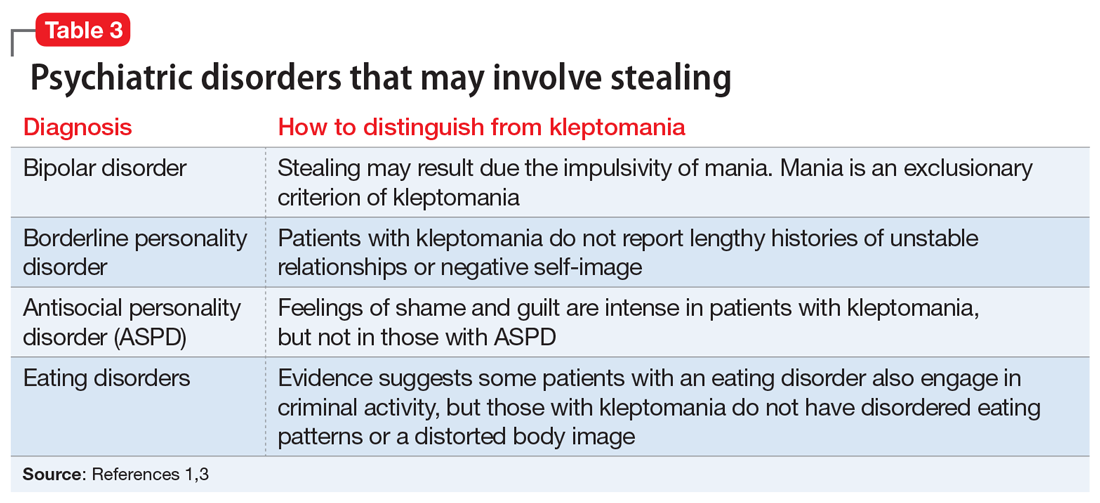

2. Distinguish kleptomania from other diagnoses that can include stealing. Because stealing can be a symptom of several other psychiatric disorders, misdiagnosis is fairly common.1 The differential can include bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and eating disorder. Table 31,3 describes how to differentiate these diagnoses from kleptomania.

3. Select an appropriate treatment. There are no FDA-approved medications for kleptomania, but some agents may help. In an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 25 patients with kleptomania who received naltrexone (50 to 150 mg/d) demonstrated significant reductions in stealing urges and behavior.6 Some evidence suggests a combination of pharmacologic and behavioral therapy (cognitive-behavioral therapy, covert sensitization, and systemic desensitization) may be the optimal treatment strategy for kleptomania.4

4. Monitor progress. After initiating treatment, use the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale7 (K-SAS) to determine treatment efficacy. The K-SAS is an 11-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the severity of kleptomania symptoms during the past week.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Goldman MJ. Kleptomania: making sense of the nonsensical. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:986-996.

3. Yao S, Kuja‐Halkola R, Thornton LM, et al. Risk of being convicted of theft and other crimes in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a prospective cohort study in a Swedish female population. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(9):1095-1103.

4. Grant JE, Kim SW. Clinical characteristics and associated psychopathology of 22 patients of kleptomania. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43(5):378-384.

5. Odlaug BL, Grant JE, Kim SW. Suicide attempts in 107 adolescents and adults with kleptomania. Arch Suicide Res. 2012;16(4):348-359.

6. Grant JE, Kim SW, Odlaug BL. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the opiate antagonist, naltrexone, in the treatment of kleptomania. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(7):600-606.

7. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

Kleptomania is characterized by a recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects that are not needed for personal use or their monetary value.1 It is a rare disorder; an estimated 0.3% to 0.6% of the general population meet DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania (Table 1).1 Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence and is more common among females than males (3:1).1 Although DSM-5 does not outline how long symptoms need to be present for patients to meet the diagnostic criteria, the disorder may persist for years, even when patients face legal consequences.1

Due to the clinical ambiguities surrounding kleptomania, it remains one of psychiatry’s most poorly understood diagnoses2 and regularly goes undiagnosed and untreated. Here we provide 4 tips for better diagnosis and treatment of this condition.

1. Screen for kleptomania in patients with other psychiatric disorders because kleptomania often is comorbid with other mental illnesses. Patients who present for evaluation of a mood disorder, substance use, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, impulse control disorders, conduct disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder should be screened for kleptomania.1,3,4 Patients with kleptomania often are reluctant to discuss their stealing because they may experience humiliation and guilt related to theft.1,4 Undiagnosed kleptomania can be fatal; a study of suicide attempts in 107 individuals with kleptomania found that 92% of the patients attributed their attempt specifically to kleptomania.5 Table 21 offers screening questions based on the DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania.

2. Distinguish kleptomania from other diagnoses that can include stealing. Because stealing can be a symptom of several other psychiatric disorders, misdiagnosis is fairly common.1 The differential can include bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and eating disorder. Table 31,3 describes how to differentiate these diagnoses from kleptomania.

3. Select an appropriate treatment. There are no FDA-approved medications for kleptomania, but some agents may help. In an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 25 patients with kleptomania who received naltrexone (50 to 150 mg/d) demonstrated significant reductions in stealing urges and behavior.6 Some evidence suggests a combination of pharmacologic and behavioral therapy (cognitive-behavioral therapy, covert sensitization, and systemic desensitization) may be the optimal treatment strategy for kleptomania.4

4. Monitor progress. After initiating treatment, use the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale7 (K-SAS) to determine treatment efficacy. The K-SAS is an 11-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the severity of kleptomania symptoms during the past week.

Kleptomania is characterized by a recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects that are not needed for personal use or their monetary value.1 It is a rare disorder; an estimated 0.3% to 0.6% of the general population meet DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania (Table 1).1 Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence and is more common among females than males (3:1).1 Although DSM-5 does not outline how long symptoms need to be present for patients to meet the diagnostic criteria, the disorder may persist for years, even when patients face legal consequences.1

Due to the clinical ambiguities surrounding kleptomania, it remains one of psychiatry’s most poorly understood diagnoses2 and regularly goes undiagnosed and untreated. Here we provide 4 tips for better diagnosis and treatment of this condition.

1. Screen for kleptomania in patients with other psychiatric disorders because kleptomania often is comorbid with other mental illnesses. Patients who present for evaluation of a mood disorder, substance use, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, impulse control disorders, conduct disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder should be screened for kleptomania.1,3,4 Patients with kleptomania often are reluctant to discuss their stealing because they may experience humiliation and guilt related to theft.1,4 Undiagnosed kleptomania can be fatal; a study of suicide attempts in 107 individuals with kleptomania found that 92% of the patients attributed their attempt specifically to kleptomania.5 Table 21 offers screening questions based on the DSM-5 criteria for kleptomania.

2. Distinguish kleptomania from other diagnoses that can include stealing. Because stealing can be a symptom of several other psychiatric disorders, misdiagnosis is fairly common.1 The differential can include bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and eating disorder. Table 31,3 describes how to differentiate these diagnoses from kleptomania.

3. Select an appropriate treatment. There are no FDA-approved medications for kleptomania, but some agents may help. In an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 25 patients with kleptomania who received naltrexone (50 to 150 mg/d) demonstrated significant reductions in stealing urges and behavior.6 Some evidence suggests a combination of pharmacologic and behavioral therapy (cognitive-behavioral therapy, covert sensitization, and systemic desensitization) may be the optimal treatment strategy for kleptomania.4

4. Monitor progress. After initiating treatment, use the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale7 (K-SAS) to determine treatment efficacy. The K-SAS is an 11-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the severity of kleptomania symptoms during the past week.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Goldman MJ. Kleptomania: making sense of the nonsensical. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:986-996.

3. Yao S, Kuja‐Halkola R, Thornton LM, et al. Risk of being convicted of theft and other crimes in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a prospective cohort study in a Swedish female population. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(9):1095-1103.

4. Grant JE, Kim SW. Clinical characteristics and associated psychopathology of 22 patients of kleptomania. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43(5):378-384.

5. Odlaug BL, Grant JE, Kim SW. Suicide attempts in 107 adolescents and adults with kleptomania. Arch Suicide Res. 2012;16(4):348-359.

6. Grant JE, Kim SW, Odlaug BL. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the opiate antagonist, naltrexone, in the treatment of kleptomania. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(7):600-606.

7. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Goldman MJ. Kleptomania: making sense of the nonsensical. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:986-996.

3. Yao S, Kuja‐Halkola R, Thornton LM, et al. Risk of being convicted of theft and other crimes in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a prospective cohort study in a Swedish female population. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(9):1095-1103.

4. Grant JE, Kim SW. Clinical characteristics and associated psychopathology of 22 patients of kleptomania. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43(5):378-384.

5. Odlaug BL, Grant JE, Kim SW. Suicide attempts in 107 adolescents and adults with kleptomania. Arch Suicide Res. 2012;16(4):348-359.

6. Grant JE, Kim SW, Odlaug BL. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the opiate antagonist, naltrexone, in the treatment of kleptomania. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(7):600-606.

7. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.