User login

Our knowledge of how natural catastrophes affect vulnerable populations should have helped us anticipate how coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) would strike the United States. This disaster has followed the well-heeled path of its predecessors, predictably bending to the influence of social determinants of health,1 structural inequality, and limited access to healthcare. Communities of color were hit early, hit hard,2 and yet again, became our nation’s canary in the coal mine. Hospitals across the country have had a front seat to this novel coronavirus’ disproportionate effect across the diverse communities we serve. Several of the cities and neighborhoods adjacent to our hospital are home to the area’s highest density of limited English proficient (LEP), immigrant, Spanish-speaking individuals.3,4 Our neighbors in these areas are more likely to have lower socioeconomic status, live in crowded housing, work in service industries deemed to be essential, and depend on shared and mass transit to get to work.5,6 As became clear, many in these communities could not work from home, get groceries delivered, or adequately social distance; these were pandemic luxuries afforded to other, more affluent areas.7

THE COVID-19 SURGE

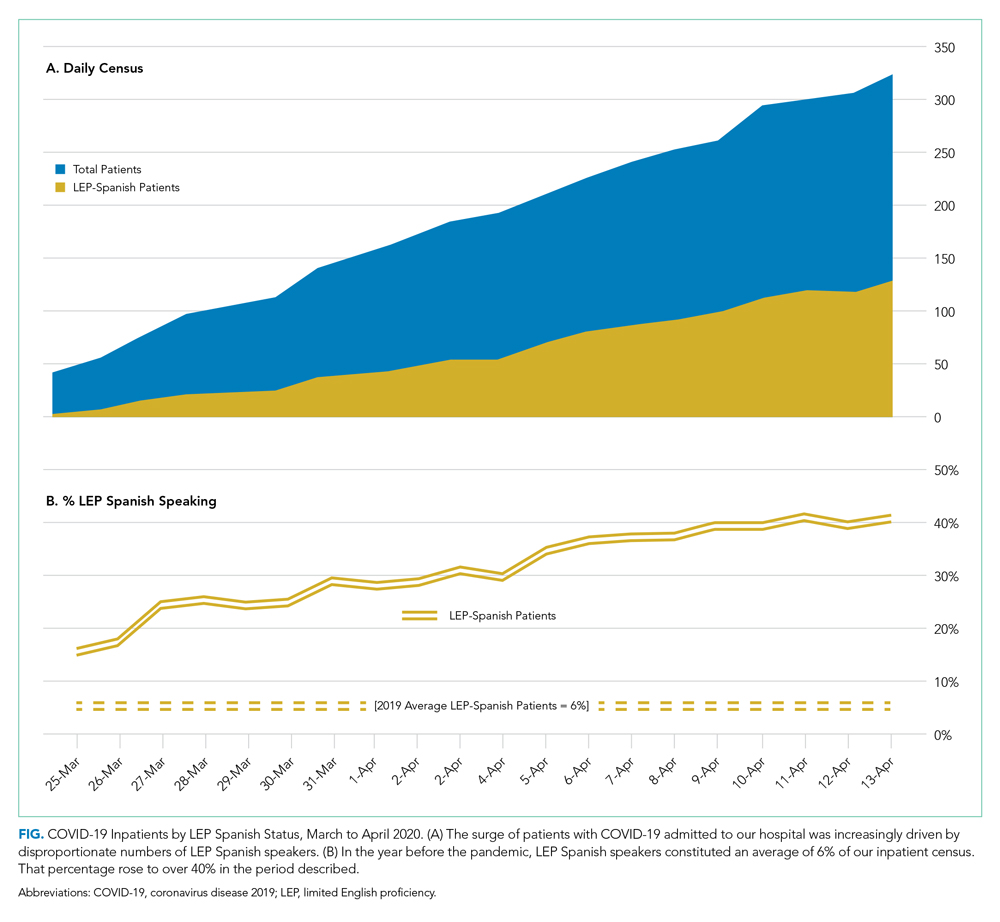

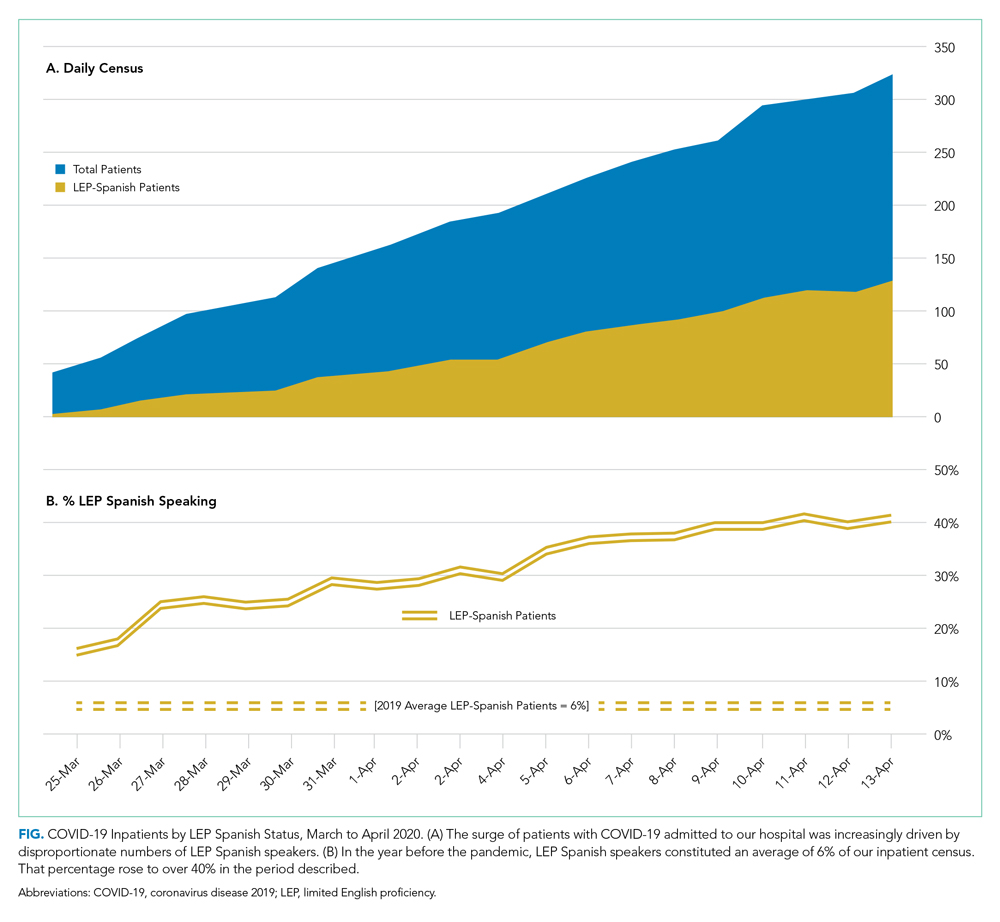

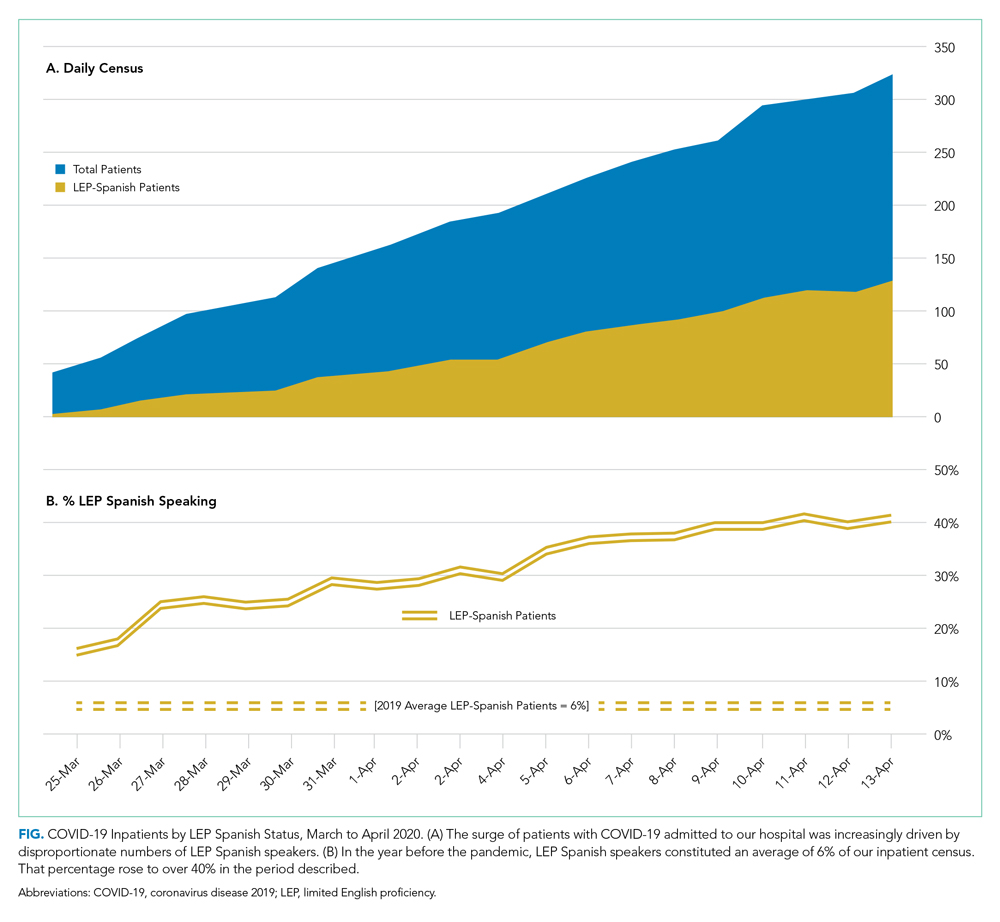

In the weeks between March 25, 2020, and April 13, 2020, the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston entered a COVID-19 surge now familiar to hospitals across the world. Like our peer institutions, we made broad and creative structural changes to inpatient services to meet the surge and we followed the numbers with anticipation. Over that 2-week period, we indeed saw the COVID-19–positive inpatient population swell as we had feared. However, with each page from the Emergency Department a disturbing trend was borne out:

ADMIT: 53-year-old Spanish-speaker with tachypnea.

ADMIT: 57-year-old factory worker, Spanish-speaking, sick for 10 days, intubated in the ED.

ADMIT: 58-year-old bodega employee, Spanish-speaking, febrile and breathless.

It buzzed across the medical floors and intensive care units: “What is going on in our Spanish speaking neighborhoods?” In fact, our shared anecdotal view was soon confirmed by admission statistics. Over the interval that our total COVID-19 census alarmingly rose sevenfold, the LEP Spanish-speaking census traced a striking curve, increasing nearly 20 times, to constitute over 40% of all COVID-19 patients (Figure). These communities were bearing a disproportionate share of the local burden of the pandemic.

There is consensus in the health care community about the impact of LEP on quality of care, and how, if unaddressed, significant disparities emerge.8 In fact, there is a broadly accepted professional,9 ethical,10 and legal11,12 imperative for hospitals to address the language needs of LEP patients using interpreter services. However, clinicians often feel forced to rely on their own limited language skills to bridge the communication divide, especially in time-limited, critical situations.13 And regrettably, the highly problematic strategy of relying upon family members to aid with communication is still commonly used. The ideal approach, however, is to invest in developing care models that recognize language as an asset and leverage the skills of multilingual clinicians who care for patients in their own language, in a culturally and linguistically competent way.14 It is not surprising that, when clinicians and patients communicate in the same language, there is demonstrably improved adherence to treatment plans,15 increased patient insight into health conditions,16 and improved delivery of health education.17

FORMATION OF THE SPANISH LANGUAGE CARE GROUP

COVID-19 created unique challenges to our interpreter services. The overwhelming number of LEP Spanish-speaking patients made it difficult for our existing interpreter staff to provide in-person translation. Virtual interpreter services were always available; however, using telephone interpretation in full personal protective equipment with patients who were already isolated and dealing with a scary diagnosis did not feel adequate to the need. In response to what we were seeing, on April 13, 2020, the idea emerged from the Chief Equity and Inclusion Officer, a native Spanish speaker, to assemble a team of native Spanish-speaking doctors, deploying them to assist in the clinical care of those LEP Spanish-speaking patients admitted with COVID-19. Out of this idea grew a creative and novel care delivery model, fashioned to prioritize culturally and linguistically competent care. It was deployed a few days later as the Spanish Language Care Group (SLCG). The belief was that this group’s members were uniquely equipped to work directly with existing frontline teams on the floors, intensive care units and the emergency department. As doctors, they were able to act as extensions of those teams, independently carrying out patient-facing clinical tasks, in Spanish, on an ad hoc basis. They took on history taking, procedural consents, clinical updates, discharge instructions, serious illness conversations and family meetings. They comforted and educated the frightened, connected with families, and unearthed relevant patient history that would have otherwise gone unnoticed. In many cases the SLCG member was the main figure communicating with patients as their clinical status deteriorated, as they were intubated, as they faced their worst fears about COVID-19.

At the time the group was assembled, each SLCG physician was verified as Qualified Bilingual Staff, already clinically credentialled at the hospital, and ready to volunteer to meet the need on the medicine COVID surge services. They practiced in virtually every division and department, including Anesthesia, Cardiology, Dermatology, Emergency Medicine, Gastroenterology, General Medicine, Neurology, Pediatrics, Psychiatry, and Radiology. With the assistance of leadership in Hospital Medicine, this team was rapidly deployed to inpatient teams to assist with the clinical care of COVID-19 patients. In total, 51 physicians—representing 14 countries of origin—participated in the effort, and their titles ranged from intern to full professor. Fourteen of them were formally deployed in the COVID surge context with approval of their departmental and divisional leadership. With such a robust response and institutional support, the SLCG was able to provide 24-hour coverage in support of the Medicine teams. During the peak of this hospital’s COVID surge, seven SLCG members were deployed daily 7

For those patients in their most vulnerable moments, the impact of the SLCG’s work is hard to overestimate, and it has also been measured by overwhelmingly positive feedback from surge care teams: “The quality of care we provided today would have been impossible without [the SLCG]. I’m so grateful and was nearly moved to tears realizing how stunted our relationships with these patients have been due to language barrier.” Another team said that the SLCG doctor was able to “care for the patient in the same way I would have if I could speak Spanish” and “it is like day and night.”After the spring 2020 surge of COVID-19, procedural work resumed, so the SLCG doctors—many of whose usual clinical activity was suspended by the pandemic—returned to their proper perch on the organization chart. But as they reflect on their experience with the group, they report that it stirred a strong and very personal sense of purpose and vocation. Should a subsequent surge of COVID-19 occur, they are committed to building on the foundation that they have laid.

DEPLOYING A LANGUAGE CARE GROUP TEAM

For hospitals that may consider deploying a team such as the SLCG, we can offer a number of concrete actions and policy recommendations. First, in preparation for the COVID surge we identified hospital clinicians with multilingual skills through the deployment of a multilingual registry. Such a registry is critical to understanding which clinicians among existing staff have these skills and who can be approached to join the team. Second, the inpatient medicine surge leadership team at our hospital, immediately recognizing the importance of this effort, developed a staffing strategy to integrate the SLCG into the institutional surge response. The benefit that the team offers needs to be made clear to those at the highest levels of operations and planning. Third, a strong and well-established Center for Diversity and Inclusion, and its leadership, helped facilitate our group’s staffing and organization. For hospitals looking to embrace the strength that their diversity-oriented recruitment efforts have afforded them, we recommend creating a centralized space in which professional relationships can grow and deepen, diverse perspectives can be explored, and embedded cultural and language skills can be championed.

The US healthcare system has much to learn from this phase of the COVID-19 era. Our experience with the Spanish Language Care Group has highlighted the value of language-concordant care, the power of cultural and linguistic competency, and the resiliency that diversity brings to a hospital’s professional staff. Our urgent response to COVID-19 has unroofed a long-simmering challenge: the detriment to care that arises when language becomes an obstacle. We are bringing a new focus to this issue and learning to view it through an equity lens. This is lending new energy to an ongoing conversation about how this hospital thinks about diversity, equity, and healthcare access in these pandemic times and into the hoped-for beyond.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their profound gratitude to the members of the Spanish Language Care Group who brought such humanity and professionalism to the care of our patients during a uniquely vulnerable time.

- Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization. Accessed November 10, 2020. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

- Buchanan L, Patel JK, Rosenthal BM, Singhvi A. A month of coronavirus in New York City: see the hardest-hit areas. New York Times. April 1, 2020. Accessed November 10, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/01/nyregion/nyc-coronavirus-cases-map.html

- QuickFacts: Chelsea city, Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. Accessed November 10, 2020. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/chelseacitymassachusetts

- Boston by the Numbers 2018. Research Division, Boston Planning & Development Agency. September 2018. Accessed November 10, 2020. http://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/3e8bfacf-27c1-4b55-adee-29c5d79f4a38

- Demographic Profile of Adult Limited English Speakers in Massachusetts. Research Division, Boston Planning & Development Agency. February 2019. Accessed November 10, 2020. http://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/dfe1117a-af16-4257-b0f5-1d95dbd575fe

- Boston in Context: Neighborhoods 2012-2016 American Community Survey. Research Division, Boston Planning & Development Agency. March 2018. Accessed November 10, 2020. http://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/55f2d86f-eccf-4f68-8d8d-c631fefb0161

- Canipe C. The social distancing of America. Reuters Graphics. April 2, 2020. Accessed November 10, 2020. https://graphics.reuters.com/HEALTH-CORONAVIRUS/USA/qmypmkmwpra/

- Betancourt J, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Park ER. Cultural competency and health care disparities: key perspectives and trends. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(2):499-505. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.499

- Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Updated 2010. American College of Physicians; 2010. Accessed November 10, 2020. https://www.acponline.org/system/files/documents/advocacy/current_policy_papers/assets/racial_disparities.pdf

- 1.1.3 Patient rights. In: Chapter 1: Opinions on Patient-Physician Relationships. Code of Medical Ethics. American Medical Association; 2016. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/code-of-medical-ethics-chapter-1.pdf

- Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 USC §2000d et seq. July 2, 1964.

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Pub L No. 111-148, 124 Stat 119 (2010) §1557.

- Regenstein M, Andres E, Wynia MK. Appropriate use of non-English-language skills in clinical care. JAMA. 2013;309(2):145-146. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.116984

- Ngo-Metzger Q, Sorkin DH, Phillips RS, et al. Providing high-quality care for limited English proficient patients: the importance of language concordance and interpreter use. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl) 2:324-330.

- Manson A. Language concordance as a determinant of patient compliance and emergency room use in patients with asthma. Med Care. 1988;26(12):1119-1128. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198812000-00003

- Seijo R, Gomez H, Garcia M, Shelton D. Acculturation, access to care, and use of preventive services by Hispanics: findings from HANES 1982-84. Am J Public Health. 1991;80(suppl):11-19

- Shapiro J, Saltzer EB. Cross-cultural aspects of physician-patient communications patterns. Urban Health. 1981;10(10):10-15.

Our knowledge of how natural catastrophes affect vulnerable populations should have helped us anticipate how coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) would strike the United States. This disaster has followed the well-heeled path of its predecessors, predictably bending to the influence of social determinants of health,1 structural inequality, and limited access to healthcare. Communities of color were hit early, hit hard,2 and yet again, became our nation’s canary in the coal mine. Hospitals across the country have had a front seat to this novel coronavirus’ disproportionate effect across the diverse communities we serve. Several of the cities and neighborhoods adjacent to our hospital are home to the area’s highest density of limited English proficient (LEP), immigrant, Spanish-speaking individuals.3,4 Our neighbors in these areas are more likely to have lower socioeconomic status, live in crowded housing, work in service industries deemed to be essential, and depend on shared and mass transit to get to work.5,6 As became clear, many in these communities could not work from home, get groceries delivered, or adequately social distance; these were pandemic luxuries afforded to other, more affluent areas.7

THE COVID-19 SURGE

In the weeks between March 25, 2020, and April 13, 2020, the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston entered a COVID-19 surge now familiar to hospitals across the world. Like our peer institutions, we made broad and creative structural changes to inpatient services to meet the surge and we followed the numbers with anticipation. Over that 2-week period, we indeed saw the COVID-19–positive inpatient population swell as we had feared. However, with each page from the Emergency Department a disturbing trend was borne out:

ADMIT: 53-year-old Spanish-speaker with tachypnea.

ADMIT: 57-year-old factory worker, Spanish-speaking, sick for 10 days, intubated in the ED.

ADMIT: 58-year-old bodega employee, Spanish-speaking, febrile and breathless.

It buzzed across the medical floors and intensive care units: “What is going on in our Spanish speaking neighborhoods?” In fact, our shared anecdotal view was soon confirmed by admission statistics. Over the interval that our total COVID-19 census alarmingly rose sevenfold, the LEP Spanish-speaking census traced a striking curve, increasing nearly 20 times, to constitute over 40% of all COVID-19 patients (Figure). These communities were bearing a disproportionate share of the local burden of the pandemic.

There is consensus in the health care community about the impact of LEP on quality of care, and how, if unaddressed, significant disparities emerge.8 In fact, there is a broadly accepted professional,9 ethical,10 and legal11,12 imperative for hospitals to address the language needs of LEP patients using interpreter services. However, clinicians often feel forced to rely on their own limited language skills to bridge the communication divide, especially in time-limited, critical situations.13 And regrettably, the highly problematic strategy of relying upon family members to aid with communication is still commonly used. The ideal approach, however, is to invest in developing care models that recognize language as an asset and leverage the skills of multilingual clinicians who care for patients in their own language, in a culturally and linguistically competent way.14 It is not surprising that, when clinicians and patients communicate in the same language, there is demonstrably improved adherence to treatment plans,15 increased patient insight into health conditions,16 and improved delivery of health education.17

FORMATION OF THE SPANISH LANGUAGE CARE GROUP

COVID-19 created unique challenges to our interpreter services. The overwhelming number of LEP Spanish-speaking patients made it difficult for our existing interpreter staff to provide in-person translation. Virtual interpreter services were always available; however, using telephone interpretation in full personal protective equipment with patients who were already isolated and dealing with a scary diagnosis did not feel adequate to the need. In response to what we were seeing, on April 13, 2020, the idea emerged from the Chief Equity and Inclusion Officer, a native Spanish speaker, to assemble a team of native Spanish-speaking doctors, deploying them to assist in the clinical care of those LEP Spanish-speaking patients admitted with COVID-19. Out of this idea grew a creative and novel care delivery model, fashioned to prioritize culturally and linguistically competent care. It was deployed a few days later as the Spanish Language Care Group (SLCG). The belief was that this group’s members were uniquely equipped to work directly with existing frontline teams on the floors, intensive care units and the emergency department. As doctors, they were able to act as extensions of those teams, independently carrying out patient-facing clinical tasks, in Spanish, on an ad hoc basis. They took on history taking, procedural consents, clinical updates, discharge instructions, serious illness conversations and family meetings. They comforted and educated the frightened, connected with families, and unearthed relevant patient history that would have otherwise gone unnoticed. In many cases the SLCG member was the main figure communicating with patients as their clinical status deteriorated, as they were intubated, as they faced their worst fears about COVID-19.

At the time the group was assembled, each SLCG physician was verified as Qualified Bilingual Staff, already clinically credentialled at the hospital, and ready to volunteer to meet the need on the medicine COVID surge services. They practiced in virtually every division and department, including Anesthesia, Cardiology, Dermatology, Emergency Medicine, Gastroenterology, General Medicine, Neurology, Pediatrics, Psychiatry, and Radiology. With the assistance of leadership in Hospital Medicine, this team was rapidly deployed to inpatient teams to assist with the clinical care of COVID-19 patients. In total, 51 physicians—representing 14 countries of origin—participated in the effort, and their titles ranged from intern to full professor. Fourteen of them were formally deployed in the COVID surge context with approval of their departmental and divisional leadership. With such a robust response and institutional support, the SLCG was able to provide 24-hour coverage in support of the Medicine teams. During the peak of this hospital’s COVID surge, seven SLCG members were deployed daily 7

For those patients in their most vulnerable moments, the impact of the SLCG’s work is hard to overestimate, and it has also been measured by overwhelmingly positive feedback from surge care teams: “The quality of care we provided today would have been impossible without [the SLCG]. I’m so grateful and was nearly moved to tears realizing how stunted our relationships with these patients have been due to language barrier.” Another team said that the SLCG doctor was able to “care for the patient in the same way I would have if I could speak Spanish” and “it is like day and night.”After the spring 2020 surge of COVID-19, procedural work resumed, so the SLCG doctors—many of whose usual clinical activity was suspended by the pandemic—returned to their proper perch on the organization chart. But as they reflect on their experience with the group, they report that it stirred a strong and very personal sense of purpose and vocation. Should a subsequent surge of COVID-19 occur, they are committed to building on the foundation that they have laid.

DEPLOYING A LANGUAGE CARE GROUP TEAM

For hospitals that may consider deploying a team such as the SLCG, we can offer a number of concrete actions and policy recommendations. First, in preparation for the COVID surge we identified hospital clinicians with multilingual skills through the deployment of a multilingual registry. Such a registry is critical to understanding which clinicians among existing staff have these skills and who can be approached to join the team. Second, the inpatient medicine surge leadership team at our hospital, immediately recognizing the importance of this effort, developed a staffing strategy to integrate the SLCG into the institutional surge response. The benefit that the team offers needs to be made clear to those at the highest levels of operations and planning. Third, a strong and well-established Center for Diversity and Inclusion, and its leadership, helped facilitate our group’s staffing and organization. For hospitals looking to embrace the strength that their diversity-oriented recruitment efforts have afforded them, we recommend creating a centralized space in which professional relationships can grow and deepen, diverse perspectives can be explored, and embedded cultural and language skills can be championed.

The US healthcare system has much to learn from this phase of the COVID-19 era. Our experience with the Spanish Language Care Group has highlighted the value of language-concordant care, the power of cultural and linguistic competency, and the resiliency that diversity brings to a hospital’s professional staff. Our urgent response to COVID-19 has unroofed a long-simmering challenge: the detriment to care that arises when language becomes an obstacle. We are bringing a new focus to this issue and learning to view it through an equity lens. This is lending new energy to an ongoing conversation about how this hospital thinks about diversity, equity, and healthcare access in these pandemic times and into the hoped-for beyond.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their profound gratitude to the members of the Spanish Language Care Group who brought such humanity and professionalism to the care of our patients during a uniquely vulnerable time.

Our knowledge of how natural catastrophes affect vulnerable populations should have helped us anticipate how coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) would strike the United States. This disaster has followed the well-heeled path of its predecessors, predictably bending to the influence of social determinants of health,1 structural inequality, and limited access to healthcare. Communities of color were hit early, hit hard,2 and yet again, became our nation’s canary in the coal mine. Hospitals across the country have had a front seat to this novel coronavirus’ disproportionate effect across the diverse communities we serve. Several of the cities and neighborhoods adjacent to our hospital are home to the area’s highest density of limited English proficient (LEP), immigrant, Spanish-speaking individuals.3,4 Our neighbors in these areas are more likely to have lower socioeconomic status, live in crowded housing, work in service industries deemed to be essential, and depend on shared and mass transit to get to work.5,6 As became clear, many in these communities could not work from home, get groceries delivered, or adequately social distance; these were pandemic luxuries afforded to other, more affluent areas.7

THE COVID-19 SURGE

In the weeks between March 25, 2020, and April 13, 2020, the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston entered a COVID-19 surge now familiar to hospitals across the world. Like our peer institutions, we made broad and creative structural changes to inpatient services to meet the surge and we followed the numbers with anticipation. Over that 2-week period, we indeed saw the COVID-19–positive inpatient population swell as we had feared. However, with each page from the Emergency Department a disturbing trend was borne out:

ADMIT: 53-year-old Spanish-speaker with tachypnea.

ADMIT: 57-year-old factory worker, Spanish-speaking, sick for 10 days, intubated in the ED.

ADMIT: 58-year-old bodega employee, Spanish-speaking, febrile and breathless.

It buzzed across the medical floors and intensive care units: “What is going on in our Spanish speaking neighborhoods?” In fact, our shared anecdotal view was soon confirmed by admission statistics. Over the interval that our total COVID-19 census alarmingly rose sevenfold, the LEP Spanish-speaking census traced a striking curve, increasing nearly 20 times, to constitute over 40% of all COVID-19 patients (Figure). These communities were bearing a disproportionate share of the local burden of the pandemic.

There is consensus in the health care community about the impact of LEP on quality of care, and how, if unaddressed, significant disparities emerge.8 In fact, there is a broadly accepted professional,9 ethical,10 and legal11,12 imperative for hospitals to address the language needs of LEP patients using interpreter services. However, clinicians often feel forced to rely on their own limited language skills to bridge the communication divide, especially in time-limited, critical situations.13 And regrettably, the highly problematic strategy of relying upon family members to aid with communication is still commonly used. The ideal approach, however, is to invest in developing care models that recognize language as an asset and leverage the skills of multilingual clinicians who care for patients in their own language, in a culturally and linguistically competent way.14 It is not surprising that, when clinicians and patients communicate in the same language, there is demonstrably improved adherence to treatment plans,15 increased patient insight into health conditions,16 and improved delivery of health education.17

FORMATION OF THE SPANISH LANGUAGE CARE GROUP

COVID-19 created unique challenges to our interpreter services. The overwhelming number of LEP Spanish-speaking patients made it difficult for our existing interpreter staff to provide in-person translation. Virtual interpreter services were always available; however, using telephone interpretation in full personal protective equipment with patients who were already isolated and dealing with a scary diagnosis did not feel adequate to the need. In response to what we were seeing, on April 13, 2020, the idea emerged from the Chief Equity and Inclusion Officer, a native Spanish speaker, to assemble a team of native Spanish-speaking doctors, deploying them to assist in the clinical care of those LEP Spanish-speaking patients admitted with COVID-19. Out of this idea grew a creative and novel care delivery model, fashioned to prioritize culturally and linguistically competent care. It was deployed a few days later as the Spanish Language Care Group (SLCG). The belief was that this group’s members were uniquely equipped to work directly with existing frontline teams on the floors, intensive care units and the emergency department. As doctors, they were able to act as extensions of those teams, independently carrying out patient-facing clinical tasks, in Spanish, on an ad hoc basis. They took on history taking, procedural consents, clinical updates, discharge instructions, serious illness conversations and family meetings. They comforted and educated the frightened, connected with families, and unearthed relevant patient history that would have otherwise gone unnoticed. In many cases the SLCG member was the main figure communicating with patients as their clinical status deteriorated, as they were intubated, as they faced their worst fears about COVID-19.

At the time the group was assembled, each SLCG physician was verified as Qualified Bilingual Staff, already clinically credentialled at the hospital, and ready to volunteer to meet the need on the medicine COVID surge services. They practiced in virtually every division and department, including Anesthesia, Cardiology, Dermatology, Emergency Medicine, Gastroenterology, General Medicine, Neurology, Pediatrics, Psychiatry, and Radiology. With the assistance of leadership in Hospital Medicine, this team was rapidly deployed to inpatient teams to assist with the clinical care of COVID-19 patients. In total, 51 physicians—representing 14 countries of origin—participated in the effort, and their titles ranged from intern to full professor. Fourteen of them were formally deployed in the COVID surge context with approval of their departmental and divisional leadership. With such a robust response and institutional support, the SLCG was able to provide 24-hour coverage in support of the Medicine teams. During the peak of this hospital’s COVID surge, seven SLCG members were deployed daily 7

For those patients in their most vulnerable moments, the impact of the SLCG’s work is hard to overestimate, and it has also been measured by overwhelmingly positive feedback from surge care teams: “The quality of care we provided today would have been impossible without [the SLCG]. I’m so grateful and was nearly moved to tears realizing how stunted our relationships with these patients have been due to language barrier.” Another team said that the SLCG doctor was able to “care for the patient in the same way I would have if I could speak Spanish” and “it is like day and night.”After the spring 2020 surge of COVID-19, procedural work resumed, so the SLCG doctors—many of whose usual clinical activity was suspended by the pandemic—returned to their proper perch on the organization chart. But as they reflect on their experience with the group, they report that it stirred a strong and very personal sense of purpose and vocation. Should a subsequent surge of COVID-19 occur, they are committed to building on the foundation that they have laid.

DEPLOYING A LANGUAGE CARE GROUP TEAM

For hospitals that may consider deploying a team such as the SLCG, we can offer a number of concrete actions and policy recommendations. First, in preparation for the COVID surge we identified hospital clinicians with multilingual skills through the deployment of a multilingual registry. Such a registry is critical to understanding which clinicians among existing staff have these skills and who can be approached to join the team. Second, the inpatient medicine surge leadership team at our hospital, immediately recognizing the importance of this effort, developed a staffing strategy to integrate the SLCG into the institutional surge response. The benefit that the team offers needs to be made clear to those at the highest levels of operations and planning. Third, a strong and well-established Center for Diversity and Inclusion, and its leadership, helped facilitate our group’s staffing and organization. For hospitals looking to embrace the strength that their diversity-oriented recruitment efforts have afforded them, we recommend creating a centralized space in which professional relationships can grow and deepen, diverse perspectives can be explored, and embedded cultural and language skills can be championed.

The US healthcare system has much to learn from this phase of the COVID-19 era. Our experience with the Spanish Language Care Group has highlighted the value of language-concordant care, the power of cultural and linguistic competency, and the resiliency that diversity brings to a hospital’s professional staff. Our urgent response to COVID-19 has unroofed a long-simmering challenge: the detriment to care that arises when language becomes an obstacle. We are bringing a new focus to this issue and learning to view it through an equity lens. This is lending new energy to an ongoing conversation about how this hospital thinks about diversity, equity, and healthcare access in these pandemic times and into the hoped-for beyond.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their profound gratitude to the members of the Spanish Language Care Group who brought such humanity and professionalism to the care of our patients during a uniquely vulnerable time.

- Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization. Accessed November 10, 2020. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

- Buchanan L, Patel JK, Rosenthal BM, Singhvi A. A month of coronavirus in New York City: see the hardest-hit areas. New York Times. April 1, 2020. Accessed November 10, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/01/nyregion/nyc-coronavirus-cases-map.html

- QuickFacts: Chelsea city, Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. Accessed November 10, 2020. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/chelseacitymassachusetts

- Boston by the Numbers 2018. Research Division, Boston Planning & Development Agency. September 2018. Accessed November 10, 2020. http://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/3e8bfacf-27c1-4b55-adee-29c5d79f4a38

- Demographic Profile of Adult Limited English Speakers in Massachusetts. Research Division, Boston Planning & Development Agency. February 2019. Accessed November 10, 2020. http://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/dfe1117a-af16-4257-b0f5-1d95dbd575fe

- Boston in Context: Neighborhoods 2012-2016 American Community Survey. Research Division, Boston Planning & Development Agency. March 2018. Accessed November 10, 2020. http://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/55f2d86f-eccf-4f68-8d8d-c631fefb0161

- Canipe C. The social distancing of America. Reuters Graphics. April 2, 2020. Accessed November 10, 2020. https://graphics.reuters.com/HEALTH-CORONAVIRUS/USA/qmypmkmwpra/

- Betancourt J, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Park ER. Cultural competency and health care disparities: key perspectives and trends. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(2):499-505. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.499

- Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Updated 2010. American College of Physicians; 2010. Accessed November 10, 2020. https://www.acponline.org/system/files/documents/advocacy/current_policy_papers/assets/racial_disparities.pdf

- 1.1.3 Patient rights. In: Chapter 1: Opinions on Patient-Physician Relationships. Code of Medical Ethics. American Medical Association; 2016. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/code-of-medical-ethics-chapter-1.pdf

- Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 USC §2000d et seq. July 2, 1964.

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Pub L No. 111-148, 124 Stat 119 (2010) §1557.

- Regenstein M, Andres E, Wynia MK. Appropriate use of non-English-language skills in clinical care. JAMA. 2013;309(2):145-146. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.116984

- Ngo-Metzger Q, Sorkin DH, Phillips RS, et al. Providing high-quality care for limited English proficient patients: the importance of language concordance and interpreter use. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl) 2:324-330.

- Manson A. Language concordance as a determinant of patient compliance and emergency room use in patients with asthma. Med Care. 1988;26(12):1119-1128. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198812000-00003

- Seijo R, Gomez H, Garcia M, Shelton D. Acculturation, access to care, and use of preventive services by Hispanics: findings from HANES 1982-84. Am J Public Health. 1991;80(suppl):11-19

- Shapiro J, Saltzer EB. Cross-cultural aspects of physician-patient communications patterns. Urban Health. 1981;10(10):10-15.

- Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization. Accessed November 10, 2020. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

- Buchanan L, Patel JK, Rosenthal BM, Singhvi A. A month of coronavirus in New York City: see the hardest-hit areas. New York Times. April 1, 2020. Accessed November 10, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/01/nyregion/nyc-coronavirus-cases-map.html

- QuickFacts: Chelsea city, Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. Accessed November 10, 2020. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/chelseacitymassachusetts

- Boston by the Numbers 2018. Research Division, Boston Planning & Development Agency. September 2018. Accessed November 10, 2020. http://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/3e8bfacf-27c1-4b55-adee-29c5d79f4a38

- Demographic Profile of Adult Limited English Speakers in Massachusetts. Research Division, Boston Planning & Development Agency. February 2019. Accessed November 10, 2020. http://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/dfe1117a-af16-4257-b0f5-1d95dbd575fe

- Boston in Context: Neighborhoods 2012-2016 American Community Survey. Research Division, Boston Planning & Development Agency. March 2018. Accessed November 10, 2020. http://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/55f2d86f-eccf-4f68-8d8d-c631fefb0161

- Canipe C. The social distancing of America. Reuters Graphics. April 2, 2020. Accessed November 10, 2020. https://graphics.reuters.com/HEALTH-CORONAVIRUS/USA/qmypmkmwpra/

- Betancourt J, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Park ER. Cultural competency and health care disparities: key perspectives and trends. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(2):499-505. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.499

- Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Updated 2010. American College of Physicians; 2010. Accessed November 10, 2020. https://www.acponline.org/system/files/documents/advocacy/current_policy_papers/assets/racial_disparities.pdf

- 1.1.3 Patient rights. In: Chapter 1: Opinions on Patient-Physician Relationships. Code of Medical Ethics. American Medical Association; 2016. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/code-of-medical-ethics-chapter-1.pdf

- Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 USC §2000d et seq. July 2, 1964.

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Pub L No. 111-148, 124 Stat 119 (2010) §1557.

- Regenstein M, Andres E, Wynia MK. Appropriate use of non-English-language skills in clinical care. JAMA. 2013;309(2):145-146. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.116984

- Ngo-Metzger Q, Sorkin DH, Phillips RS, et al. Providing high-quality care for limited English proficient patients: the importance of language concordance and interpreter use. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl) 2:324-330.

- Manson A. Language concordance as a determinant of patient compliance and emergency room use in patients with asthma. Med Care. 1988;26(12):1119-1128. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198812000-00003

- Seijo R, Gomez H, Garcia M, Shelton D. Acculturation, access to care, and use of preventive services by Hispanics: findings from HANES 1982-84. Am J Public Health. 1991;80(suppl):11-19

- Shapiro J, Saltzer EB. Cross-cultural aspects of physician-patient communications patterns. Urban Health. 1981;10(10):10-15.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Email: sknuesel@mgh.harvard.edu; Telephone: 617-898-7722; Twitter: @StevenKnuesel