User login

Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction is a postsurgical dilatation of the colon that presents with abdominal distension, pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea and may lead to colonic ischemia and bowel perforation.

A cute colonic pseudo-obstruction, or Ogilvie syndrome, is dilatation of the colon without mechanical obstruction. It is often seen postoperatively after cesarean section , pelvic , spinal, or other orthopedic surgery, such as knee arthroplasty. 1 One study demonstrated an incidence of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction of 1.3% following hip replacement surgery. 2

The most common symptoms are abdominal distension, pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea. Bowel sounds are present in the majority of cases.3 It is important to recognize the varied presentations of ileus in the postoperative setting. The most serious complications of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction are colonic ischemia and bowel perforation.

Case Presentation

An 84-year-old man underwent a total left hip arthroplasty revision. The evening after his surgery, his blood pressure (BP) decreased from 93/54 to 71/47 mm Hg, and his heart rate was 73 beats per minute. He was awake, in no acute distress, but reported loose stools. Results of cardiac and pulmonary examinations were normal, showing a regular rate and rhythm with no murmurs and clear lungs. There was normal jugular venous pressure and chronic pitting edema of the lower extremities bilaterally.

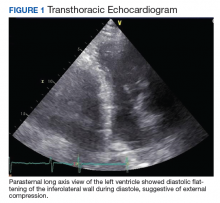

An abdominal examination revealed positive bowel sounds, a large ventral hernia, which was easily reducible, and a distended abdomen. His BP remained unchanged after IV normal saline 4 L, and urine output was 200 cc over 4 hours, which the care team determined represented adequate resuscitation. An infection workup, including chest X-ray, urinalysis, and blood and urine cultures, was unrevealing. Hemoglobin was stable at 8.5 g/dL (normal range 14-18), and creatinine level 0.66 mg/dL (normal range 0.7-1.2) at baseline. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed impaired diastolic filling suggestive of extrinsic compression of the left ventricle by mediastinal contents (Figure 1). An abdominal X-ray revealed diffuse dilatation of large bowel loops up to 10 cm, causing elevation and rightward shift of the heart (Figure 2A). A computed tomography scan of the abdomen showed total colonic dilatation without obstruction (Figure 2B).

The patient was diagnosed with postoperative ileus and acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Nasogastric and rectal tubes were placed for decompression, and the patient was placed on nothing by mouth status. By postoperative day 3, his hypotension had resolved and his BP had improved to 111/58 mm Hg. The patient was able to resume a regular diet.

Discussion

We present an unusual case of left ventricular compression leading to hypotension due to acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Our patient presented with the rare complication of hypotension due to cardiac compression, which we have not previously seen reported in the literature. Analogous instance of cardiac compression may arise from hiatal hernias and diaphragmatic paralysis. 4-6

Management of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction is through nothing by mouth status and abdominal decompression. For more severe cases, neostigmine, colonoscopic decompression, and surgery can be considered.

This surgical complication was diagnosed by internal medicine hospitalist consultants on a surgical comanagement service. In the comanagement model, the surgical specialties of orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery, and podiatry at San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center in California have hospitalists who work with the team as active consultants for the medical care of the patients. Hospitalists develop a unique skill set in which they can anticipate new diagnoses, prevent or identify early complications, and individualize a patient’s postoperative care.7 One study found that a surgical comanagement service was associated with a decrease in the number of patients with at least 1 surgical complication, decrease in length of stay and 30-day readmissions for a medical cause, decreased consultant use, and an average cost savings per patient of about $2,600 to $4,300.8

Conclusions

With the increasing prevalence of hospitalist comanagement services, it is important for surgeons and nonsurgeons alike to recognize acute colonic pseudo-obstruction as a possible surgical complication.

1. Bernardi M, Warrier S, Lynch C, Heriot A. Acute and chronic pseudo-obstruction: a current update. ANZ J Surg. 2015;85(10):709-714. doi:10.1111/ans.13148

2. Norwood MGA, Lykostratis H, Garcea G, Berry DP. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction following major orthopaedic surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7(5):496-499. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00790.x

3. Vanek VW, Al-Salti M. Acute pseudo-obstruction of the colon (Ogilvie’s syndrome). An analysis of 400 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29(3):203-210. doi:10.1007/BF02555027

4. Devabhandari MP, Khan MA, Hooper TL. Cardiac compression following cardiac surgery due to unrecognised hiatus hernia. Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg. 2007;32(5):813-815. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.08.002

5. Asti E, Bonavina L, Lombardi M, Bandera F, Secchi F, Guazzi M. Reversibility of cardiopulmonary impairment after laparoscopic repair of large hiatal hernia. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;14:33-35. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.07.005

6. Tayyareci Y, Bayazit P, Taştan CP, Aksoy H. Right atrial compression due to idiopathic right diaphragm paralysis detected incidentally by transthoracic echocardiography. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2008;36(6):412-414.

7. Rohatgi N, Schulman K, Ahuja N. Comanagement by hospitalists: why it makes clinical and fiscal sense. Am J Med. 2020;133(3):257-258. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.07.053

8. Rohatgi N, Loftus P, Grujic O, Cullen M, Hopkins J, Ahuja N. Surgical comanagement by hospitalists improves patient outcomes: a propensity score analysis. Ann Surg. 2016;264(2):275-282. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001629

Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction is a postsurgical dilatation of the colon that presents with abdominal distension, pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea and may lead to colonic ischemia and bowel perforation.

Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction is a postsurgical dilatation of the colon that presents with abdominal distension, pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea and may lead to colonic ischemia and bowel perforation.

A cute colonic pseudo-obstruction, or Ogilvie syndrome, is dilatation of the colon without mechanical obstruction. It is often seen postoperatively after cesarean section , pelvic , spinal, or other orthopedic surgery, such as knee arthroplasty. 1 One study demonstrated an incidence of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction of 1.3% following hip replacement surgery. 2

The most common symptoms are abdominal distension, pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea. Bowel sounds are present in the majority of cases.3 It is important to recognize the varied presentations of ileus in the postoperative setting. The most serious complications of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction are colonic ischemia and bowel perforation.

Case Presentation

An 84-year-old man underwent a total left hip arthroplasty revision. The evening after his surgery, his blood pressure (BP) decreased from 93/54 to 71/47 mm Hg, and his heart rate was 73 beats per minute. He was awake, in no acute distress, but reported loose stools. Results of cardiac and pulmonary examinations were normal, showing a regular rate and rhythm with no murmurs and clear lungs. There was normal jugular venous pressure and chronic pitting edema of the lower extremities bilaterally.

An abdominal examination revealed positive bowel sounds, a large ventral hernia, which was easily reducible, and a distended abdomen. His BP remained unchanged after IV normal saline 4 L, and urine output was 200 cc over 4 hours, which the care team determined represented adequate resuscitation. An infection workup, including chest X-ray, urinalysis, and blood and urine cultures, was unrevealing. Hemoglobin was stable at 8.5 g/dL (normal range 14-18), and creatinine level 0.66 mg/dL (normal range 0.7-1.2) at baseline. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed impaired diastolic filling suggestive of extrinsic compression of the left ventricle by mediastinal contents (Figure 1). An abdominal X-ray revealed diffuse dilatation of large bowel loops up to 10 cm, causing elevation and rightward shift of the heart (Figure 2A). A computed tomography scan of the abdomen showed total colonic dilatation without obstruction (Figure 2B).

The patient was diagnosed with postoperative ileus and acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Nasogastric and rectal tubes were placed for decompression, and the patient was placed on nothing by mouth status. By postoperative day 3, his hypotension had resolved and his BP had improved to 111/58 mm Hg. The patient was able to resume a regular diet.

Discussion

We present an unusual case of left ventricular compression leading to hypotension due to acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Our patient presented with the rare complication of hypotension due to cardiac compression, which we have not previously seen reported in the literature. Analogous instance of cardiac compression may arise from hiatal hernias and diaphragmatic paralysis. 4-6

Management of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction is through nothing by mouth status and abdominal decompression. For more severe cases, neostigmine, colonoscopic decompression, and surgery can be considered.

This surgical complication was diagnosed by internal medicine hospitalist consultants on a surgical comanagement service. In the comanagement model, the surgical specialties of orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery, and podiatry at San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center in California have hospitalists who work with the team as active consultants for the medical care of the patients. Hospitalists develop a unique skill set in which they can anticipate new diagnoses, prevent or identify early complications, and individualize a patient’s postoperative care.7 One study found that a surgical comanagement service was associated with a decrease in the number of patients with at least 1 surgical complication, decrease in length of stay and 30-day readmissions for a medical cause, decreased consultant use, and an average cost savings per patient of about $2,600 to $4,300.8

Conclusions

With the increasing prevalence of hospitalist comanagement services, it is important for surgeons and nonsurgeons alike to recognize acute colonic pseudo-obstruction as a possible surgical complication.

A cute colonic pseudo-obstruction, or Ogilvie syndrome, is dilatation of the colon without mechanical obstruction. It is often seen postoperatively after cesarean section , pelvic , spinal, or other orthopedic surgery, such as knee arthroplasty. 1 One study demonstrated an incidence of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction of 1.3% following hip replacement surgery. 2

The most common symptoms are abdominal distension, pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea. Bowel sounds are present in the majority of cases.3 It is important to recognize the varied presentations of ileus in the postoperative setting. The most serious complications of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction are colonic ischemia and bowel perforation.

Case Presentation

An 84-year-old man underwent a total left hip arthroplasty revision. The evening after his surgery, his blood pressure (BP) decreased from 93/54 to 71/47 mm Hg, and his heart rate was 73 beats per minute. He was awake, in no acute distress, but reported loose stools. Results of cardiac and pulmonary examinations were normal, showing a regular rate and rhythm with no murmurs and clear lungs. There was normal jugular venous pressure and chronic pitting edema of the lower extremities bilaterally.

An abdominal examination revealed positive bowel sounds, a large ventral hernia, which was easily reducible, and a distended abdomen. His BP remained unchanged after IV normal saline 4 L, and urine output was 200 cc over 4 hours, which the care team determined represented adequate resuscitation. An infection workup, including chest X-ray, urinalysis, and blood and urine cultures, was unrevealing. Hemoglobin was stable at 8.5 g/dL (normal range 14-18), and creatinine level 0.66 mg/dL (normal range 0.7-1.2) at baseline. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed impaired diastolic filling suggestive of extrinsic compression of the left ventricle by mediastinal contents (Figure 1). An abdominal X-ray revealed diffuse dilatation of large bowel loops up to 10 cm, causing elevation and rightward shift of the heart (Figure 2A). A computed tomography scan of the abdomen showed total colonic dilatation without obstruction (Figure 2B).

The patient was diagnosed with postoperative ileus and acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Nasogastric and rectal tubes were placed for decompression, and the patient was placed on nothing by mouth status. By postoperative day 3, his hypotension had resolved and his BP had improved to 111/58 mm Hg. The patient was able to resume a regular diet.

Discussion

We present an unusual case of left ventricular compression leading to hypotension due to acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Our patient presented with the rare complication of hypotension due to cardiac compression, which we have not previously seen reported in the literature. Analogous instance of cardiac compression may arise from hiatal hernias and diaphragmatic paralysis. 4-6

Management of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction is through nothing by mouth status and abdominal decompression. For more severe cases, neostigmine, colonoscopic decompression, and surgery can be considered.

This surgical complication was diagnosed by internal medicine hospitalist consultants on a surgical comanagement service. In the comanagement model, the surgical specialties of orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery, and podiatry at San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center in California have hospitalists who work with the team as active consultants for the medical care of the patients. Hospitalists develop a unique skill set in which they can anticipate new diagnoses, prevent or identify early complications, and individualize a patient’s postoperative care.7 One study found that a surgical comanagement service was associated with a decrease in the number of patients with at least 1 surgical complication, decrease in length of stay and 30-day readmissions for a medical cause, decreased consultant use, and an average cost savings per patient of about $2,600 to $4,300.8

Conclusions

With the increasing prevalence of hospitalist comanagement services, it is important for surgeons and nonsurgeons alike to recognize acute colonic pseudo-obstruction as a possible surgical complication.

1. Bernardi M, Warrier S, Lynch C, Heriot A. Acute and chronic pseudo-obstruction: a current update. ANZ J Surg. 2015;85(10):709-714. doi:10.1111/ans.13148

2. Norwood MGA, Lykostratis H, Garcea G, Berry DP. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction following major orthopaedic surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7(5):496-499. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00790.x

3. Vanek VW, Al-Salti M. Acute pseudo-obstruction of the colon (Ogilvie’s syndrome). An analysis of 400 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29(3):203-210. doi:10.1007/BF02555027

4. Devabhandari MP, Khan MA, Hooper TL. Cardiac compression following cardiac surgery due to unrecognised hiatus hernia. Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg. 2007;32(5):813-815. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.08.002

5. Asti E, Bonavina L, Lombardi M, Bandera F, Secchi F, Guazzi M. Reversibility of cardiopulmonary impairment after laparoscopic repair of large hiatal hernia. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;14:33-35. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.07.005

6. Tayyareci Y, Bayazit P, Taştan CP, Aksoy H. Right atrial compression due to idiopathic right diaphragm paralysis detected incidentally by transthoracic echocardiography. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2008;36(6):412-414.

7. Rohatgi N, Schulman K, Ahuja N. Comanagement by hospitalists: why it makes clinical and fiscal sense. Am J Med. 2020;133(3):257-258. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.07.053

8. Rohatgi N, Loftus P, Grujic O, Cullen M, Hopkins J, Ahuja N. Surgical comanagement by hospitalists improves patient outcomes: a propensity score analysis. Ann Surg. 2016;264(2):275-282. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001629

1. Bernardi M, Warrier S, Lynch C, Heriot A. Acute and chronic pseudo-obstruction: a current update. ANZ J Surg. 2015;85(10):709-714. doi:10.1111/ans.13148

2. Norwood MGA, Lykostratis H, Garcea G, Berry DP. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction following major orthopaedic surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7(5):496-499. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00790.x

3. Vanek VW, Al-Salti M. Acute pseudo-obstruction of the colon (Ogilvie’s syndrome). An analysis of 400 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29(3):203-210. doi:10.1007/BF02555027

4. Devabhandari MP, Khan MA, Hooper TL. Cardiac compression following cardiac surgery due to unrecognised hiatus hernia. Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg. 2007;32(5):813-815. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.08.002

5. Asti E, Bonavina L, Lombardi M, Bandera F, Secchi F, Guazzi M. Reversibility of cardiopulmonary impairment after laparoscopic repair of large hiatal hernia. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;14:33-35. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.07.005

6. Tayyareci Y, Bayazit P, Taştan CP, Aksoy H. Right atrial compression due to idiopathic right diaphragm paralysis detected incidentally by transthoracic echocardiography. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2008;36(6):412-414.

7. Rohatgi N, Schulman K, Ahuja N. Comanagement by hospitalists: why it makes clinical and fiscal sense. Am J Med. 2020;133(3):257-258. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.07.053

8. Rohatgi N, Loftus P, Grujic O, Cullen M, Hopkins J, Ahuja N. Surgical comanagement by hospitalists improves patient outcomes: a propensity score analysis. Ann Surg. 2016;264(2):275-282. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001629