User login

The pulsed dye laser (PDL) has been widely used in the treatment of port-wine stains, telangiectases, and other cutaneous vascular lesions since the late 1980s.1 This treatment modality generally is considered to have few serious adverse effects. There have been few reports of PDL treatment with subsequent complications,1-3 which may include ulceration developing immediately after treatment as well as scarring with a spotlike pattern caused by laser therapy. Numerous studies within the last 2 decades have documented improvement in the appearance of scars and telangiectases following treatment with PDL.4-6 We report the case of a 42-year-old woman who developed atrophic linear scarring of the nasal ala following cosmetic treatment with a 595-nm PDL.

Case Report

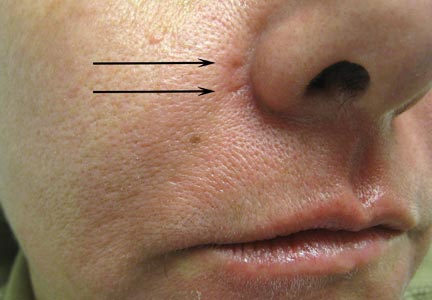

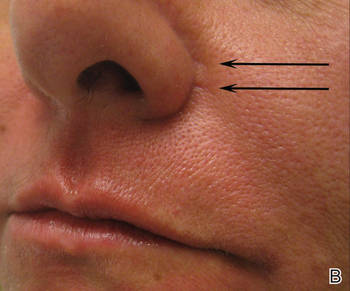

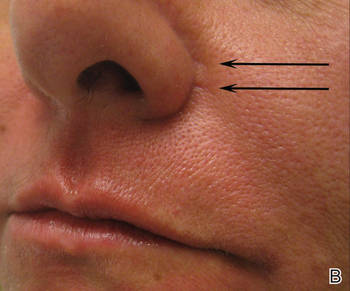

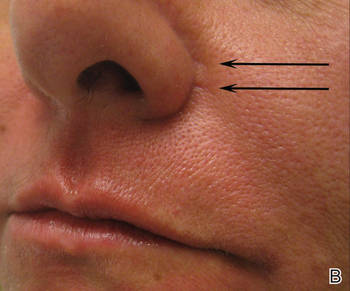

A healthy 42-year-old woman presented with atrophic linear scarring of the bilateral nasal alae following treatment with a 595-nm PDL. The patient had initially presented to an outside clinic 13 months prior for treatment of multiple telangiectases in this area. She received a single, 1-pass treatment with the 595-nm PDL (spot size, 3×10 mm; fluence, 11 J/cm2; pulse duration, 1.5 milliseconds) and returned to the clinic approximately 2 months later for a second treatment with the same settings. Seven months later she returned for a third treatment of the recalcitrant alar telangiectases with the same settings to maximize clinical outcome. Dynamic cooling was used during all treatment sessions with 30/20 setting. After the third treatment, immediate blanching followed by purpura was noted in the treated area. The patient initially was lost to follow-up but returned to the outside clinic 6 months later. On physical examination white atrophic skin with linear scarred depressions were noted on the nasofacial angle of the nasal alae (Figure). The patient denied any postoperative complications such as scabbing, blistering, or pain. At that time she was referred to our office for evaluation, and treatment with a hyaluronic acid filler was initiated. Examination and medical history were otherwise unremarkable at the time of presentation to our office. Resolution of skin atrophy and excellent correction of the depressions was maintained at a follow-up 2 months later. She declined photographs at that time.

|

|

|

| Right (A), left (B), and frontal (C) views of atrophic linear scars (arrows) caused by high-energy purpuric doses of a 595-nm pulsed dye laser. |

Comment

The PDL often is employed in the treatment of vascular lesions such as telangiectases.7 The most common adverse effect is postinflammatory hyperpigmentation; atrophic and hypertrophic scarring rarely are seen.1,8,9 In a study of adverse reactions following pulsed tunable dye laser treatment of port-wine stains in 701 patients, atrophic scarring occurred in 5% of patients and 0.83% of treatments; clinical resolution was noted over the following 6 to 12 months in 30% of patients.8

Following treatment with the PDL, thermal damage occurs primarily to vessel walls with little or no damage to surrounding nonvascular structures. The depth of vascular injury after PDL treatment has been shown to be approximately 1.2 mm.10

Although scarring in our patient was a result of PDL treatment, PDL therapy is commonly used as a treatment option for scars. In conjunction with intralesional steroids directed at flattening hypertrophic scars and keloids, the PDL is used to reduce scar redness and enhance pliability.11 Although redness and telangiectases that develop in surgical scars usually spontaneously remit, they often can show prolonged and incomplete healing. Surgical scars have been shown to benefit from PDL treatment as it advances the end point closer to the complete absence of redness.11-14

The off-label use of hyaluronic acid filler in our patient is notable, as the injection of the nasal ala is not an ordinary injection site for this filler material. It can be associated with risk for necrosis and thus must be performed by an experienced injector combined with informed consent from the patient. The nasal ala is particularly sebaceous and consists of fibrofatty tissue, which is not easily amenable to infiltration. Despite this usual characteristic of the nasal area, the scarring in our patient was fortuitously lateral to the nasal ala and easily filled with hyaluronic acid, as a linear tract was created by the high energies and linear spot size used to treat the patient.

We report a 595-nm PDL treatment that resulted in atrophic linear scarring in a distribution mimicking the linear spot size used by the laser operator. No adverse effects were noted following the first 2 treatments, thereby suggesting either a cumulative insult or more likely cutaneous necrosis from excessive fluence and short pulse durations due to operator inexperience. Other possibilities include rapid and overlapping passes with the laser leading to bulk heating and thermal injury to the skin.

Alternative laser treatment protocols have been proposed in the literature. Rohrer et al15 recommended multiple passes at subpurpuric doses for treatment of facial telangiectases with the PDL. It has been suggested that multiple stacked pulses at lower fluences may have similar effects on targets as a single pulse at a higher fluence, thereby minimizing thermal injury and leading to decreased risk for adverse events such as scarring. When treating vascular lesions such as telangiectases, increasing the fluence will increase the risk for purpura due to the constant pulse duration. Stacking pulses of lower fluence may have the advantage of heating vessels to a critical temperature without creating purpura, leading to similar clearance rates with decreased adverse risk profiles.15

It may be better to err on the side of safety by performing a greater number of treatment sessions with increased pulse width and decreased fluence (subpurpuric treatment settings) to minimize the risk for atrophic scarring from treatment with the PDL. Treating superficial facial telangiectases with a pulse-stacking technique may improve clinical results without a remarkable increase in adverse effects. It may be wrongfully intuitive to try to maximize results by using high fluences and purpuric narrow pulse durations; this case report reiterates the danger of using these settings in an attempt to rapidly achieve clearance of telangiectases. Lastly, this case underscores the value of verbal and written postoperative instructions that should be given to every patient prior to undergoing laser therapy. Specifically, with regard to our case, the laser operator must be aware at all times of potential adverse events, which may be foreseen during treatment if persistent or prolonged blanching and/or blistering occurs. The physician operator and patient must be prepared to rapidly respond to adverse reactions such as skin necrosis or blistering. Meticulous wound care is necessary if skin breakdown occurs. We recommend using a hydrating petrolatum ointment or a topical emulsion to minimize the risks for scarring, if possible.

1. Levine VJ, Geronemus RG. Adverse effects associated with the 577- and 585-nanometer pulsed dye laser in the treatment of cutaneous vascular lesions: a study of 500 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:613-617.

2. Witman PM, Wagner AM, Scherer K, et al. Complications following pulsed dye laser treatment of superficial hemangiomas. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:116-123.

3. Sommer S, Sheehan-Dare RA. Atrophie blanche-like scarring after pulsed dye laser treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:100-102.

4. Dover JS, Geronemus R, Stern RS, et al. Dye laser treatment of port-wine stains: comparison of the continuous-wave dye laser with a robotized scanning device and the pulsed dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(2, pt 1):237-240.

5. Dierickx C, Goldman MP, Fitzpatrick RE. Laser treatment of erythematous/hypertrophic and pigmented scars in 26 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95:84-90.

6. Wittenberg GP, Fabian BG, Bogomilsky JL, et al. Prospective, single-blind, randomized, controlled study to assess the efficacy of the 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser and silicone gel sheeting in hypertrophic scar treatment. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1049-1055.

7. Ross EV, Uebelhoer NS, Domankevitz Y. Use of a novel pulse dye laser for rapid single-pass purpura-free treatment of telangiectases. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1466-1469.

8. Seukeran DC, Collins P, Sheehan-Dare RA. Adverse reactions following pulsed tunable dye laser treatment of port wine stains in 701 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:725-729.

9. Wlotzke U, Hohenleutner U, Abd-El-Raheem TA, et al. Side-effects and complications of flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser therapy of port-wine stains. a prospective study. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:475-480.

10. Tan OT, Morrison P, Kurban AK. 585 nm for the treatment of port-wine stains. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:1112-1117.

11. Alam M, Pon K, Van Laborde S, et al. Clinical effect of a single pulsed dye laser treatment of fresh surgical scars: randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:21-25.

12. Bowes LE, Nouri K, Berman B, et al. Treatment of pigmented hypertrophic scars with the 585 nm pulsed dye laser and the 532 nm frequency-doubled Nd:YAG laser in the Q-switched and variable pulse modes: a comparative study. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:714-719.

13. Alster TS, Williams CM. Treatment of keloid sternotomy scars with 585 nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser. Lancet. 1995;345:1198-1200.

14. Manuskiatti W, Fitzpatrick RE. Treatment response of keloidal and hypertrophic sternotomy scars: comparison among intralesional corticosteroid, 5-fluorouracil, and 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser treatments. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1149-1155.

15. Rohrer TE, Chatrath V, Iyengar V. Does pulse stacking improve the results of treatment with variable-pulse pulsed-dye lasers? Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(2, pt 1):163-167.

The pulsed dye laser (PDL) has been widely used in the treatment of port-wine stains, telangiectases, and other cutaneous vascular lesions since the late 1980s.1 This treatment modality generally is considered to have few serious adverse effects. There have been few reports of PDL treatment with subsequent complications,1-3 which may include ulceration developing immediately after treatment as well as scarring with a spotlike pattern caused by laser therapy. Numerous studies within the last 2 decades have documented improvement in the appearance of scars and telangiectases following treatment with PDL.4-6 We report the case of a 42-year-old woman who developed atrophic linear scarring of the nasal ala following cosmetic treatment with a 595-nm PDL.

Case Report

A healthy 42-year-old woman presented with atrophic linear scarring of the bilateral nasal alae following treatment with a 595-nm PDL. The patient had initially presented to an outside clinic 13 months prior for treatment of multiple telangiectases in this area. She received a single, 1-pass treatment with the 595-nm PDL (spot size, 3×10 mm; fluence, 11 J/cm2; pulse duration, 1.5 milliseconds) and returned to the clinic approximately 2 months later for a second treatment with the same settings. Seven months later she returned for a third treatment of the recalcitrant alar telangiectases with the same settings to maximize clinical outcome. Dynamic cooling was used during all treatment sessions with 30/20 setting. After the third treatment, immediate blanching followed by purpura was noted in the treated area. The patient initially was lost to follow-up but returned to the outside clinic 6 months later. On physical examination white atrophic skin with linear scarred depressions were noted on the nasofacial angle of the nasal alae (Figure). The patient denied any postoperative complications such as scabbing, blistering, or pain. At that time she was referred to our office for evaluation, and treatment with a hyaluronic acid filler was initiated. Examination and medical history were otherwise unremarkable at the time of presentation to our office. Resolution of skin atrophy and excellent correction of the depressions was maintained at a follow-up 2 months later. She declined photographs at that time.

|

|

|

| Right (A), left (B), and frontal (C) views of atrophic linear scars (arrows) caused by high-energy purpuric doses of a 595-nm pulsed dye laser. |

Comment

The PDL often is employed in the treatment of vascular lesions such as telangiectases.7 The most common adverse effect is postinflammatory hyperpigmentation; atrophic and hypertrophic scarring rarely are seen.1,8,9 In a study of adverse reactions following pulsed tunable dye laser treatment of port-wine stains in 701 patients, atrophic scarring occurred in 5% of patients and 0.83% of treatments; clinical resolution was noted over the following 6 to 12 months in 30% of patients.8

Following treatment with the PDL, thermal damage occurs primarily to vessel walls with little or no damage to surrounding nonvascular structures. The depth of vascular injury after PDL treatment has been shown to be approximately 1.2 mm.10

Although scarring in our patient was a result of PDL treatment, PDL therapy is commonly used as a treatment option for scars. In conjunction with intralesional steroids directed at flattening hypertrophic scars and keloids, the PDL is used to reduce scar redness and enhance pliability.11 Although redness and telangiectases that develop in surgical scars usually spontaneously remit, they often can show prolonged and incomplete healing. Surgical scars have been shown to benefit from PDL treatment as it advances the end point closer to the complete absence of redness.11-14

The off-label use of hyaluronic acid filler in our patient is notable, as the injection of the nasal ala is not an ordinary injection site for this filler material. It can be associated with risk for necrosis and thus must be performed by an experienced injector combined with informed consent from the patient. The nasal ala is particularly sebaceous and consists of fibrofatty tissue, which is not easily amenable to infiltration. Despite this usual characteristic of the nasal area, the scarring in our patient was fortuitously lateral to the nasal ala and easily filled with hyaluronic acid, as a linear tract was created by the high energies and linear spot size used to treat the patient.

We report a 595-nm PDL treatment that resulted in atrophic linear scarring in a distribution mimicking the linear spot size used by the laser operator. No adverse effects were noted following the first 2 treatments, thereby suggesting either a cumulative insult or more likely cutaneous necrosis from excessive fluence and short pulse durations due to operator inexperience. Other possibilities include rapid and overlapping passes with the laser leading to bulk heating and thermal injury to the skin.

Alternative laser treatment protocols have been proposed in the literature. Rohrer et al15 recommended multiple passes at subpurpuric doses for treatment of facial telangiectases with the PDL. It has been suggested that multiple stacked pulses at lower fluences may have similar effects on targets as a single pulse at a higher fluence, thereby minimizing thermal injury and leading to decreased risk for adverse events such as scarring. When treating vascular lesions such as telangiectases, increasing the fluence will increase the risk for purpura due to the constant pulse duration. Stacking pulses of lower fluence may have the advantage of heating vessels to a critical temperature without creating purpura, leading to similar clearance rates with decreased adverse risk profiles.15

It may be better to err on the side of safety by performing a greater number of treatment sessions with increased pulse width and decreased fluence (subpurpuric treatment settings) to minimize the risk for atrophic scarring from treatment with the PDL. Treating superficial facial telangiectases with a pulse-stacking technique may improve clinical results without a remarkable increase in adverse effects. It may be wrongfully intuitive to try to maximize results by using high fluences and purpuric narrow pulse durations; this case report reiterates the danger of using these settings in an attempt to rapidly achieve clearance of telangiectases. Lastly, this case underscores the value of verbal and written postoperative instructions that should be given to every patient prior to undergoing laser therapy. Specifically, with regard to our case, the laser operator must be aware at all times of potential adverse events, which may be foreseen during treatment if persistent or prolonged blanching and/or blistering occurs. The physician operator and patient must be prepared to rapidly respond to adverse reactions such as skin necrosis or blistering. Meticulous wound care is necessary if skin breakdown occurs. We recommend using a hydrating petrolatum ointment or a topical emulsion to minimize the risks for scarring, if possible.

The pulsed dye laser (PDL) has been widely used in the treatment of port-wine stains, telangiectases, and other cutaneous vascular lesions since the late 1980s.1 This treatment modality generally is considered to have few serious adverse effects. There have been few reports of PDL treatment with subsequent complications,1-3 which may include ulceration developing immediately after treatment as well as scarring with a spotlike pattern caused by laser therapy. Numerous studies within the last 2 decades have documented improvement in the appearance of scars and telangiectases following treatment with PDL.4-6 We report the case of a 42-year-old woman who developed atrophic linear scarring of the nasal ala following cosmetic treatment with a 595-nm PDL.

Case Report

A healthy 42-year-old woman presented with atrophic linear scarring of the bilateral nasal alae following treatment with a 595-nm PDL. The patient had initially presented to an outside clinic 13 months prior for treatment of multiple telangiectases in this area. She received a single, 1-pass treatment with the 595-nm PDL (spot size, 3×10 mm; fluence, 11 J/cm2; pulse duration, 1.5 milliseconds) and returned to the clinic approximately 2 months later for a second treatment with the same settings. Seven months later she returned for a third treatment of the recalcitrant alar telangiectases with the same settings to maximize clinical outcome. Dynamic cooling was used during all treatment sessions with 30/20 setting. After the third treatment, immediate blanching followed by purpura was noted in the treated area. The patient initially was lost to follow-up but returned to the outside clinic 6 months later. On physical examination white atrophic skin with linear scarred depressions were noted on the nasofacial angle of the nasal alae (Figure). The patient denied any postoperative complications such as scabbing, blistering, or pain. At that time she was referred to our office for evaluation, and treatment with a hyaluronic acid filler was initiated. Examination and medical history were otherwise unremarkable at the time of presentation to our office. Resolution of skin atrophy and excellent correction of the depressions was maintained at a follow-up 2 months later. She declined photographs at that time.

|

|

|

| Right (A), left (B), and frontal (C) views of atrophic linear scars (arrows) caused by high-energy purpuric doses of a 595-nm pulsed dye laser. |

Comment

The PDL often is employed in the treatment of vascular lesions such as telangiectases.7 The most common adverse effect is postinflammatory hyperpigmentation; atrophic and hypertrophic scarring rarely are seen.1,8,9 In a study of adverse reactions following pulsed tunable dye laser treatment of port-wine stains in 701 patients, atrophic scarring occurred in 5% of patients and 0.83% of treatments; clinical resolution was noted over the following 6 to 12 months in 30% of patients.8

Following treatment with the PDL, thermal damage occurs primarily to vessel walls with little or no damage to surrounding nonvascular structures. The depth of vascular injury after PDL treatment has been shown to be approximately 1.2 mm.10

Although scarring in our patient was a result of PDL treatment, PDL therapy is commonly used as a treatment option for scars. In conjunction with intralesional steroids directed at flattening hypertrophic scars and keloids, the PDL is used to reduce scar redness and enhance pliability.11 Although redness and telangiectases that develop in surgical scars usually spontaneously remit, they often can show prolonged and incomplete healing. Surgical scars have been shown to benefit from PDL treatment as it advances the end point closer to the complete absence of redness.11-14

The off-label use of hyaluronic acid filler in our patient is notable, as the injection of the nasal ala is not an ordinary injection site for this filler material. It can be associated with risk for necrosis and thus must be performed by an experienced injector combined with informed consent from the patient. The nasal ala is particularly sebaceous and consists of fibrofatty tissue, which is not easily amenable to infiltration. Despite this usual characteristic of the nasal area, the scarring in our patient was fortuitously lateral to the nasal ala and easily filled with hyaluronic acid, as a linear tract was created by the high energies and linear spot size used to treat the patient.

We report a 595-nm PDL treatment that resulted in atrophic linear scarring in a distribution mimicking the linear spot size used by the laser operator. No adverse effects were noted following the first 2 treatments, thereby suggesting either a cumulative insult or more likely cutaneous necrosis from excessive fluence and short pulse durations due to operator inexperience. Other possibilities include rapid and overlapping passes with the laser leading to bulk heating and thermal injury to the skin.

Alternative laser treatment protocols have been proposed in the literature. Rohrer et al15 recommended multiple passes at subpurpuric doses for treatment of facial telangiectases with the PDL. It has been suggested that multiple stacked pulses at lower fluences may have similar effects on targets as a single pulse at a higher fluence, thereby minimizing thermal injury and leading to decreased risk for adverse events such as scarring. When treating vascular lesions such as telangiectases, increasing the fluence will increase the risk for purpura due to the constant pulse duration. Stacking pulses of lower fluence may have the advantage of heating vessels to a critical temperature without creating purpura, leading to similar clearance rates with decreased adverse risk profiles.15

It may be better to err on the side of safety by performing a greater number of treatment sessions with increased pulse width and decreased fluence (subpurpuric treatment settings) to minimize the risk for atrophic scarring from treatment with the PDL. Treating superficial facial telangiectases with a pulse-stacking technique may improve clinical results without a remarkable increase in adverse effects. It may be wrongfully intuitive to try to maximize results by using high fluences and purpuric narrow pulse durations; this case report reiterates the danger of using these settings in an attempt to rapidly achieve clearance of telangiectases. Lastly, this case underscores the value of verbal and written postoperative instructions that should be given to every patient prior to undergoing laser therapy. Specifically, with regard to our case, the laser operator must be aware at all times of potential adverse events, which may be foreseen during treatment if persistent or prolonged blanching and/or blistering occurs. The physician operator and patient must be prepared to rapidly respond to adverse reactions such as skin necrosis or blistering. Meticulous wound care is necessary if skin breakdown occurs. We recommend using a hydrating petrolatum ointment or a topical emulsion to minimize the risks for scarring, if possible.

1. Levine VJ, Geronemus RG. Adverse effects associated with the 577- and 585-nanometer pulsed dye laser in the treatment of cutaneous vascular lesions: a study of 500 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:613-617.

2. Witman PM, Wagner AM, Scherer K, et al. Complications following pulsed dye laser treatment of superficial hemangiomas. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:116-123.

3. Sommer S, Sheehan-Dare RA. Atrophie blanche-like scarring after pulsed dye laser treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:100-102.

4. Dover JS, Geronemus R, Stern RS, et al. Dye laser treatment of port-wine stains: comparison of the continuous-wave dye laser with a robotized scanning device and the pulsed dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(2, pt 1):237-240.

5. Dierickx C, Goldman MP, Fitzpatrick RE. Laser treatment of erythematous/hypertrophic and pigmented scars in 26 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95:84-90.

6. Wittenberg GP, Fabian BG, Bogomilsky JL, et al. Prospective, single-blind, randomized, controlled study to assess the efficacy of the 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser and silicone gel sheeting in hypertrophic scar treatment. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1049-1055.

7. Ross EV, Uebelhoer NS, Domankevitz Y. Use of a novel pulse dye laser for rapid single-pass purpura-free treatment of telangiectases. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1466-1469.

8. Seukeran DC, Collins P, Sheehan-Dare RA. Adverse reactions following pulsed tunable dye laser treatment of port wine stains in 701 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:725-729.

9. Wlotzke U, Hohenleutner U, Abd-El-Raheem TA, et al. Side-effects and complications of flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser therapy of port-wine stains. a prospective study. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:475-480.

10. Tan OT, Morrison P, Kurban AK. 585 nm for the treatment of port-wine stains. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:1112-1117.

11. Alam M, Pon K, Van Laborde S, et al. Clinical effect of a single pulsed dye laser treatment of fresh surgical scars: randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:21-25.

12. Bowes LE, Nouri K, Berman B, et al. Treatment of pigmented hypertrophic scars with the 585 nm pulsed dye laser and the 532 nm frequency-doubled Nd:YAG laser in the Q-switched and variable pulse modes: a comparative study. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:714-719.

13. Alster TS, Williams CM. Treatment of keloid sternotomy scars with 585 nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser. Lancet. 1995;345:1198-1200.

14. Manuskiatti W, Fitzpatrick RE. Treatment response of keloidal and hypertrophic sternotomy scars: comparison among intralesional corticosteroid, 5-fluorouracil, and 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser treatments. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1149-1155.

15. Rohrer TE, Chatrath V, Iyengar V. Does pulse stacking improve the results of treatment with variable-pulse pulsed-dye lasers? Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(2, pt 1):163-167.

1. Levine VJ, Geronemus RG. Adverse effects associated with the 577- and 585-nanometer pulsed dye laser in the treatment of cutaneous vascular lesions: a study of 500 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:613-617.

2. Witman PM, Wagner AM, Scherer K, et al. Complications following pulsed dye laser treatment of superficial hemangiomas. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:116-123.

3. Sommer S, Sheehan-Dare RA. Atrophie blanche-like scarring after pulsed dye laser treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:100-102.

4. Dover JS, Geronemus R, Stern RS, et al. Dye laser treatment of port-wine stains: comparison of the continuous-wave dye laser with a robotized scanning device and the pulsed dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(2, pt 1):237-240.

5. Dierickx C, Goldman MP, Fitzpatrick RE. Laser treatment of erythematous/hypertrophic and pigmented scars in 26 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95:84-90.

6. Wittenberg GP, Fabian BG, Bogomilsky JL, et al. Prospective, single-blind, randomized, controlled study to assess the efficacy of the 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser and silicone gel sheeting in hypertrophic scar treatment. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1049-1055.

7. Ross EV, Uebelhoer NS, Domankevitz Y. Use of a novel pulse dye laser for rapid single-pass purpura-free treatment of telangiectases. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1466-1469.

8. Seukeran DC, Collins P, Sheehan-Dare RA. Adverse reactions following pulsed tunable dye laser treatment of port wine stains in 701 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:725-729.

9. Wlotzke U, Hohenleutner U, Abd-El-Raheem TA, et al. Side-effects and complications of flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser therapy of port-wine stains. a prospective study. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:475-480.

10. Tan OT, Morrison P, Kurban AK. 585 nm for the treatment of port-wine stains. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:1112-1117.

11. Alam M, Pon K, Van Laborde S, et al. Clinical effect of a single pulsed dye laser treatment of fresh surgical scars: randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:21-25.

12. Bowes LE, Nouri K, Berman B, et al. Treatment of pigmented hypertrophic scars with the 585 nm pulsed dye laser and the 532 nm frequency-doubled Nd:YAG laser in the Q-switched and variable pulse modes: a comparative study. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:714-719.

13. Alster TS, Williams CM. Treatment of keloid sternotomy scars with 585 nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser. Lancet. 1995;345:1198-1200.

14. Manuskiatti W, Fitzpatrick RE. Treatment response of keloidal and hypertrophic sternotomy scars: comparison among intralesional corticosteroid, 5-fluorouracil, and 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser treatments. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1149-1155.

15. Rohrer TE, Chatrath V, Iyengar V. Does pulse stacking improve the results of treatment with variable-pulse pulsed-dye lasers? Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(2, pt 1):163-167.

Practice Points

- Lasers should be used by experienced operators and treatments should be tailored to individual patient needs.

- Multiple passes at subpurpuric settings with the pulsed dye laser may lead to safer results with fewer adverse events and at the same time more tolerable treatments for the patient by minimizing downtime associated with purpura.

- Although scarring is rare, it can occur and should be part of the patient’s informed consent prior to treatment.