User login

Subcutaneous, Mucocutaneous, and Mucous Membrane Tumors

The Diagnosis: Granular Cell Tumor

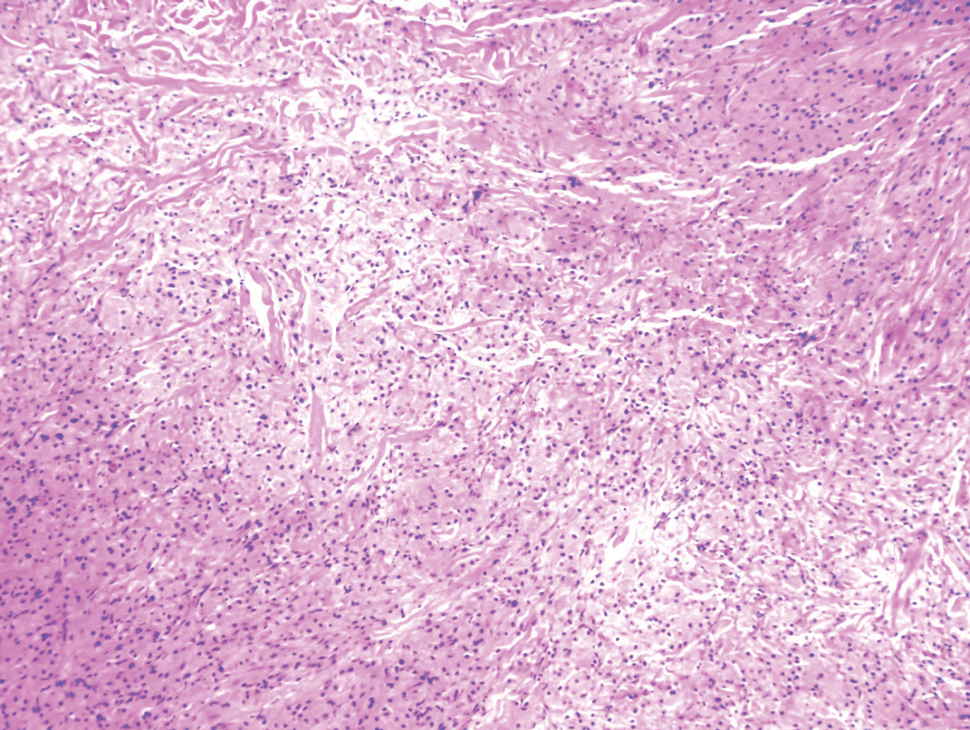

Histopathologic analysis from the axillary excision demonstrated cords and sheets of large polygonal cells in the dermis with uniform, oval, hyperchromatic nuclei and ample pink granular-staining cytoplasm (quiz images). An infiltrative growth pattern was noted; however, there was no evidence of conspicuous mitoses, nuclear pleomorphism, or necrosis. These results in conjunction with the immunohistochemistry findings were consistent with a benign granular cell tumor (GCT), a rare neoplasm considered to have neural/Schwann cell origin.1-3

Our case demonstrates the difficulty in clinically diagnosing cutaneous GCTs. The tumor often presents as a solitary, 0.5- to 3-cm, asymptomatic, firm nodule4,5; however, GCTs also can appear verrucous, eroded, or with other variable morphologies, which can create diagnostic challenges.5,6 Accordingly, a 1980 study of 110 patients with GCTs found that the preoperative clinical diagnosis was incorrect in all but 3 cases,7 emphasizing the need for histologic evaluation. Benign GCTs tend to exhibit sheets of polygonal tumor cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and small central nuclei.3,5 The cytoplasmic granules are periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant.6 Many cases feature pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, which can misleadingly resemble squamous cell carcinoma.3,5,6 Of note, invasive growth patterns on histology can occur with benign GCTs, as in our patient's case, and do not impact prognosis.3,4 On immunohistochemistry, benign, atypical, and malignant GCTs often stain positive for S-100 protein, vimentin, neuron-specific enolase, SOX10, and CD68.1,3

Although our patient's GCTs were benign, an estimated 1% to 2% are malignant.1,4 In 1998, Fanburg-Smith et al1 defined 6 histologic criteria that characterize malignant GCTs: necrosis, tumor cell spindling, vesicular nuclei with large nucleoli, high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, increased mitosis, and pleomorphism. Neoplasms with 3 or more of these features are classified as malignant, those with 1 or 2 are considered atypical, and those with only pleomorphism or no other criteria met are diagnosed as benign.1

Multiple GCTs have been reported in 10% to 25% of cases and, as highlighted in our case, can occur in both a metachronous and synchronous manner.2-4,6 Our patient developed a solitary GCT on the inferior lip 3 years prior to the appearance of 2 additional GCTs within 6 months of each other. The presence of multiple GCTs has been associated with genetic syndromes, such as neurofibromatosis type 1 and Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines3,8; however, as our case demonstrates, multiple GCTs can occur in nonsyndromic patients as well. When multiple GCTs develop at distant sites, they can resemble metastasis.3 To differentiate these clinical scenarios, Machado et al3 proposed utilizing histology and anatomic location. Multiple tumors with benign characteristics on histology likely represent multiple GCTs, whereas tumors arising at sites common to GCT metastasis, such as lymph node, bone, or viscera, are more concerning for metastatic disease. It has been suggested that patients with multiple GCTs should be monitored with physical examination and repeat magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography every 6 to 12 months.2 Given our patient's presentation with new tumors arising within 6 months of one another, we recommended a 6-month follow-up interval rather than 1 year. Due to the rarity of GCTs, clinical trials to define treatment guidelines and recommendations have not been performed.3 However, the most commonly utilized treatment modality is wide local excision, as performed in our patient.2,4

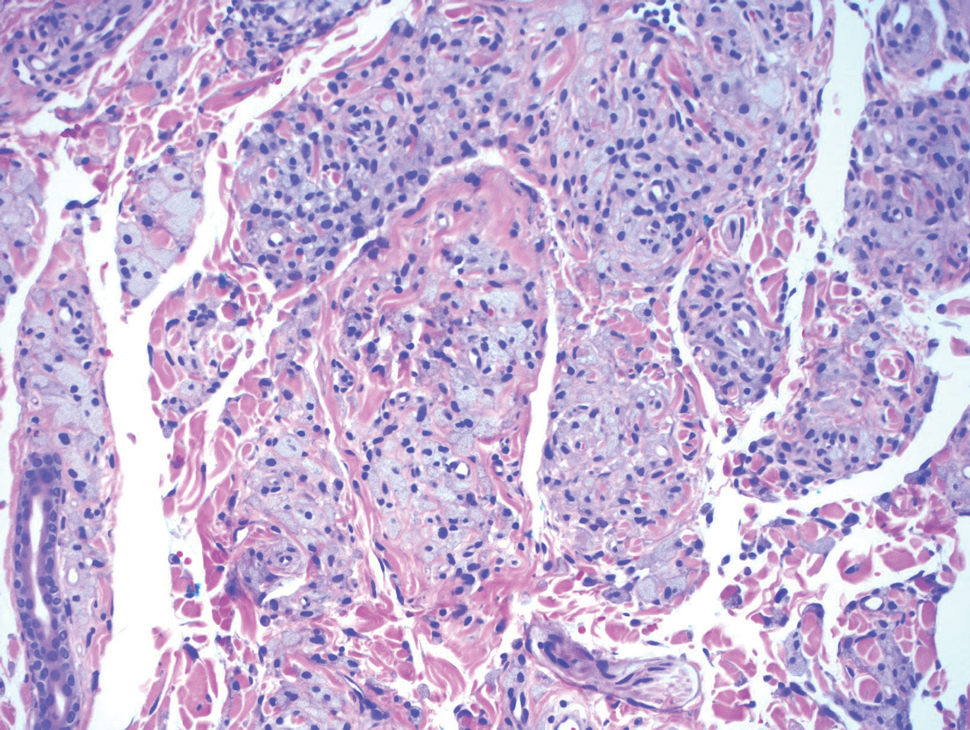

Melanoma, atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), xanthoma, and leiomyosarcoma may be difficult to distinguish from GCT.1,3,4 Melanoma incidence has increased dramatically over the last several decades, with rates in the United States rising from 6.8 cases per 100,000 individuals in the 1970s to 20.1 in the early 2000s. Risk factors for its development include UV radiation exposure and particularly severe sunburns during childhood, along with a number of host risk factors such as total number of melanocytic nevi, family history, and fair complexion.9 Histologically, it often demonstrates irregularly distributed, poorly defined melanocytes with pagetoid spread and dyscohesive nests (Figure 1).10 Melanoma metastasis occasionally can present as a soft-tissue mass and often stains positive for S-100 and vimentin, thus resembling GCT1,4; however, unlike melanoma, GCTs lack melanosomes and stain negative for more specific melanocyte markers, such as melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1).1,3,4

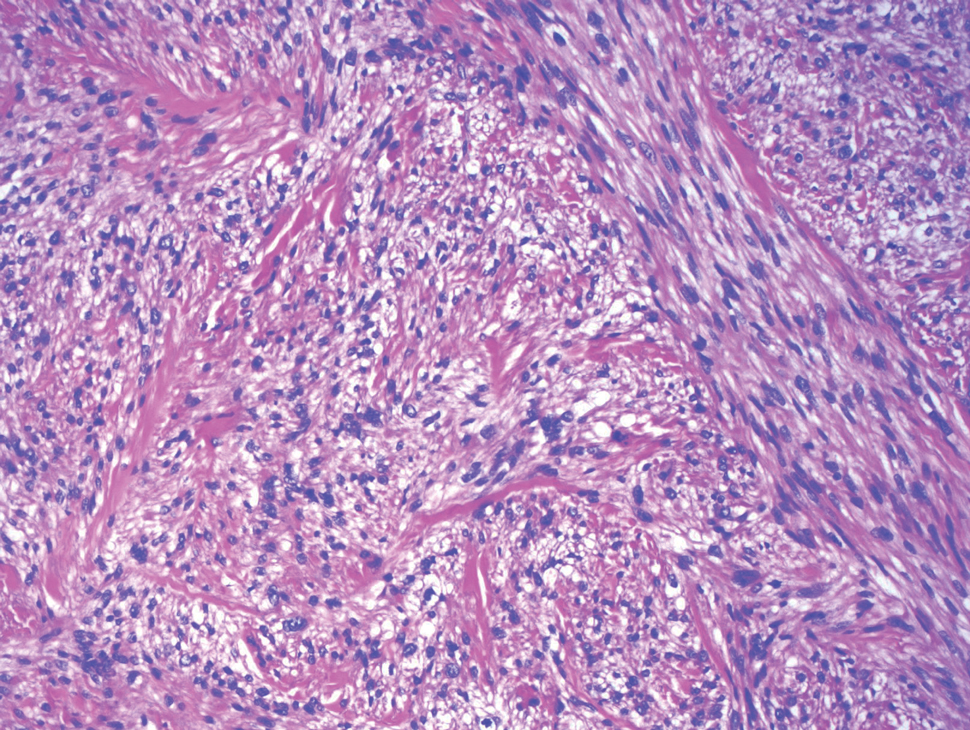

Atypical fibroxanthoma is a cutaneous neoplasm with fibrohistiocytic mesenchymal origin.11 These tumors typically arise on the head and neck in elderly individuals, particularly men with sun-damaged skin. They often present as superficial, rapidly growing nodules with the potential to ulcerate and bleed.11,12 Histologic features include pleomorphic spindle and epithelioid cells, whose nuclei appear hyperchromatic with atypical mitoses (Figure 2).12 Granular cell changes occur infrequently with AFXs, but in such cases immunohistochemistry can readily distinguish AFX from GCT. Although both tend to stain positive for CD68 and vimentin, AFXs lack S-100 protein and SOX10 expression that frequently is observed in GCTs.3,12

Xanthomas are localized lipid deposits in the connective tissue of the skin that often arise in association with dyslipidemia.13 They typically present as soft to semisolid yellow papules, plaques, or nodules. Their clinical appearance can resemble GCTs; however, histologic analysis enables differentiation with ease, as xanthomas demonstrate characteristic foam cells, consisting of lipid-laden macrophages (Figure 3).13

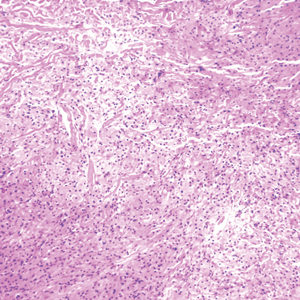

Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma is a rare dermal neoplasm, accounting for 2% to 3% of all sarcomas.14 They typically occur in White males during the fifth to seventh decades of life and often present as asymptomatic lesions on the lower extremities. They frequently arise from pilar smooth muscle. Unlike uterine and soft-tissue leiomyosarcoma, cutaneous leiomyosarcoma tends to follow an indolent course and rarely metastasizes.14 Histologically, these tumors display intersecting, well-defined, spindle-cell fascicles with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and cigar-shaped, blunt-ended nuclei (Figure 4).15 Occasionally, leiomyosarcomas can demonstrate cytoplasmic granularity due to lysosome accumulation4; nevertheless, the diagnosis usually can be elucidated by examining more typical histologic areas and utilizing immunohistochemistry, which often stains positive for α-smooth muscle actin, desmin, and h-caldesmon.4,15

- Fanburg-Smith JC, Meis-Kindblom JM, Fante R, et al. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:779-794.

- Moten AS, Movva S, von Mehren M, et al. Granular cell tumor experience at a comprehensive cancer center. J Surg Res. 2018;226:1-7.

- Machado I, Cruz J, Lavernia J, et al. Solitary, multiple, benign, atypical, or malignant: the "granular cell tumor" puzzle. Virchows Arch. 2016;468:527-538.

- Ordóñez NG. Granular cell tumor: a review and update. Adv Anat Pathol. 1999;6:186-203.

- Vaughan V, Ferringer T. Granular cell tumor. Cutis. 2014;94:275, 279-280.

- Van L, Parker SR. Multiple morphologically distinct cutaneous granular cell tumors occurring in a single patient. Cutis. 2016;97:E26-E29.

- Lack EE, Worsham GF, Callihan MD, et al. Granular cell tumor: a clinicopathologic study of 110 patients. J Surg Oncol. 1980;13:301-316.

- Bamps S, Oyen T, Legius E, et al. Multiple granular cell tumors in a child with Noonan syndrome. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2013;23:257-259.

- Rastrelli M, Tropea S, Rossi CR, et al. Melanoma: epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis and classification. In Vivo. 2014;28:1005-1011.

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneousmalignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(suppl 2):S34-S40.

- Soleymani T, Aasi SZ, Novoa R, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: updates on classification and management. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:253-259.

- Cardis MA, Ni J, Bhawan J. Granular cell differentiation: a review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2017;44:251-258.

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, et al. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations [published online April 29, 2014]. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158:181-188.

- Sandhu N, Sauvageau AP, Groman A, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: a SEER database analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:159-164.

- George S, Serrano C, Hensley ML, et al. Soft tissue and uterine leiomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:144-150.

The Diagnosis: Granular Cell Tumor

Histopathologic analysis from the axillary excision demonstrated cords and sheets of large polygonal cells in the dermis with uniform, oval, hyperchromatic nuclei and ample pink granular-staining cytoplasm (quiz images). An infiltrative growth pattern was noted; however, there was no evidence of conspicuous mitoses, nuclear pleomorphism, or necrosis. These results in conjunction with the immunohistochemistry findings were consistent with a benign granular cell tumor (GCT), a rare neoplasm considered to have neural/Schwann cell origin.1-3

Our case demonstrates the difficulty in clinically diagnosing cutaneous GCTs. The tumor often presents as a solitary, 0.5- to 3-cm, asymptomatic, firm nodule4,5; however, GCTs also can appear verrucous, eroded, or with other variable morphologies, which can create diagnostic challenges.5,6 Accordingly, a 1980 study of 110 patients with GCTs found that the preoperative clinical diagnosis was incorrect in all but 3 cases,7 emphasizing the need for histologic evaluation. Benign GCTs tend to exhibit sheets of polygonal tumor cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and small central nuclei.3,5 The cytoplasmic granules are periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant.6 Many cases feature pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, which can misleadingly resemble squamous cell carcinoma.3,5,6 Of note, invasive growth patterns on histology can occur with benign GCTs, as in our patient's case, and do not impact prognosis.3,4 On immunohistochemistry, benign, atypical, and malignant GCTs often stain positive for S-100 protein, vimentin, neuron-specific enolase, SOX10, and CD68.1,3

Although our patient's GCTs were benign, an estimated 1% to 2% are malignant.1,4 In 1998, Fanburg-Smith et al1 defined 6 histologic criteria that characterize malignant GCTs: necrosis, tumor cell spindling, vesicular nuclei with large nucleoli, high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, increased mitosis, and pleomorphism. Neoplasms with 3 or more of these features are classified as malignant, those with 1 or 2 are considered atypical, and those with only pleomorphism or no other criteria met are diagnosed as benign.1

Multiple GCTs have been reported in 10% to 25% of cases and, as highlighted in our case, can occur in both a metachronous and synchronous manner.2-4,6 Our patient developed a solitary GCT on the inferior lip 3 years prior to the appearance of 2 additional GCTs within 6 months of each other. The presence of multiple GCTs has been associated with genetic syndromes, such as neurofibromatosis type 1 and Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines3,8; however, as our case demonstrates, multiple GCTs can occur in nonsyndromic patients as well. When multiple GCTs develop at distant sites, they can resemble metastasis.3 To differentiate these clinical scenarios, Machado et al3 proposed utilizing histology and anatomic location. Multiple tumors with benign characteristics on histology likely represent multiple GCTs, whereas tumors arising at sites common to GCT metastasis, such as lymph node, bone, or viscera, are more concerning for metastatic disease. It has been suggested that patients with multiple GCTs should be monitored with physical examination and repeat magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography every 6 to 12 months.2 Given our patient's presentation with new tumors arising within 6 months of one another, we recommended a 6-month follow-up interval rather than 1 year. Due to the rarity of GCTs, clinical trials to define treatment guidelines and recommendations have not been performed.3 However, the most commonly utilized treatment modality is wide local excision, as performed in our patient.2,4

Melanoma, atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), xanthoma, and leiomyosarcoma may be difficult to distinguish from GCT.1,3,4 Melanoma incidence has increased dramatically over the last several decades, with rates in the United States rising from 6.8 cases per 100,000 individuals in the 1970s to 20.1 in the early 2000s. Risk factors for its development include UV radiation exposure and particularly severe sunburns during childhood, along with a number of host risk factors such as total number of melanocytic nevi, family history, and fair complexion.9 Histologically, it often demonstrates irregularly distributed, poorly defined melanocytes with pagetoid spread and dyscohesive nests (Figure 1).10 Melanoma metastasis occasionally can present as a soft-tissue mass and often stains positive for S-100 and vimentin, thus resembling GCT1,4; however, unlike melanoma, GCTs lack melanosomes and stain negative for more specific melanocyte markers, such as melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1).1,3,4

Atypical fibroxanthoma is a cutaneous neoplasm with fibrohistiocytic mesenchymal origin.11 These tumors typically arise on the head and neck in elderly individuals, particularly men with sun-damaged skin. They often present as superficial, rapidly growing nodules with the potential to ulcerate and bleed.11,12 Histologic features include pleomorphic spindle and epithelioid cells, whose nuclei appear hyperchromatic with atypical mitoses (Figure 2).12 Granular cell changes occur infrequently with AFXs, but in such cases immunohistochemistry can readily distinguish AFX from GCT. Although both tend to stain positive for CD68 and vimentin, AFXs lack S-100 protein and SOX10 expression that frequently is observed in GCTs.3,12

Xanthomas are localized lipid deposits in the connective tissue of the skin that often arise in association with dyslipidemia.13 They typically present as soft to semisolid yellow papules, plaques, or nodules. Their clinical appearance can resemble GCTs; however, histologic analysis enables differentiation with ease, as xanthomas demonstrate characteristic foam cells, consisting of lipid-laden macrophages (Figure 3).13

Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma is a rare dermal neoplasm, accounting for 2% to 3% of all sarcomas.14 They typically occur in White males during the fifth to seventh decades of life and often present as asymptomatic lesions on the lower extremities. They frequently arise from pilar smooth muscle. Unlike uterine and soft-tissue leiomyosarcoma, cutaneous leiomyosarcoma tends to follow an indolent course and rarely metastasizes.14 Histologically, these tumors display intersecting, well-defined, spindle-cell fascicles with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and cigar-shaped, blunt-ended nuclei (Figure 4).15 Occasionally, leiomyosarcomas can demonstrate cytoplasmic granularity due to lysosome accumulation4; nevertheless, the diagnosis usually can be elucidated by examining more typical histologic areas and utilizing immunohistochemistry, which often stains positive for α-smooth muscle actin, desmin, and h-caldesmon.4,15

The Diagnosis: Granular Cell Tumor

Histopathologic analysis from the axillary excision demonstrated cords and sheets of large polygonal cells in the dermis with uniform, oval, hyperchromatic nuclei and ample pink granular-staining cytoplasm (quiz images). An infiltrative growth pattern was noted; however, there was no evidence of conspicuous mitoses, nuclear pleomorphism, or necrosis. These results in conjunction with the immunohistochemistry findings were consistent with a benign granular cell tumor (GCT), a rare neoplasm considered to have neural/Schwann cell origin.1-3

Our case demonstrates the difficulty in clinically diagnosing cutaneous GCTs. The tumor often presents as a solitary, 0.5- to 3-cm, asymptomatic, firm nodule4,5; however, GCTs also can appear verrucous, eroded, or with other variable morphologies, which can create diagnostic challenges.5,6 Accordingly, a 1980 study of 110 patients with GCTs found that the preoperative clinical diagnosis was incorrect in all but 3 cases,7 emphasizing the need for histologic evaluation. Benign GCTs tend to exhibit sheets of polygonal tumor cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and small central nuclei.3,5 The cytoplasmic granules are periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant.6 Many cases feature pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, which can misleadingly resemble squamous cell carcinoma.3,5,6 Of note, invasive growth patterns on histology can occur with benign GCTs, as in our patient's case, and do not impact prognosis.3,4 On immunohistochemistry, benign, atypical, and malignant GCTs often stain positive for S-100 protein, vimentin, neuron-specific enolase, SOX10, and CD68.1,3

Although our patient's GCTs were benign, an estimated 1% to 2% are malignant.1,4 In 1998, Fanburg-Smith et al1 defined 6 histologic criteria that characterize malignant GCTs: necrosis, tumor cell spindling, vesicular nuclei with large nucleoli, high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, increased mitosis, and pleomorphism. Neoplasms with 3 or more of these features are classified as malignant, those with 1 or 2 are considered atypical, and those with only pleomorphism or no other criteria met are diagnosed as benign.1

Multiple GCTs have been reported in 10% to 25% of cases and, as highlighted in our case, can occur in both a metachronous and synchronous manner.2-4,6 Our patient developed a solitary GCT on the inferior lip 3 years prior to the appearance of 2 additional GCTs within 6 months of each other. The presence of multiple GCTs has been associated with genetic syndromes, such as neurofibromatosis type 1 and Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines3,8; however, as our case demonstrates, multiple GCTs can occur in nonsyndromic patients as well. When multiple GCTs develop at distant sites, they can resemble metastasis.3 To differentiate these clinical scenarios, Machado et al3 proposed utilizing histology and anatomic location. Multiple tumors with benign characteristics on histology likely represent multiple GCTs, whereas tumors arising at sites common to GCT metastasis, such as lymph node, bone, or viscera, are more concerning for metastatic disease. It has been suggested that patients with multiple GCTs should be monitored with physical examination and repeat magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography every 6 to 12 months.2 Given our patient's presentation with new tumors arising within 6 months of one another, we recommended a 6-month follow-up interval rather than 1 year. Due to the rarity of GCTs, clinical trials to define treatment guidelines and recommendations have not been performed.3 However, the most commonly utilized treatment modality is wide local excision, as performed in our patient.2,4

Melanoma, atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), xanthoma, and leiomyosarcoma may be difficult to distinguish from GCT.1,3,4 Melanoma incidence has increased dramatically over the last several decades, with rates in the United States rising from 6.8 cases per 100,000 individuals in the 1970s to 20.1 in the early 2000s. Risk factors for its development include UV radiation exposure and particularly severe sunburns during childhood, along with a number of host risk factors such as total number of melanocytic nevi, family history, and fair complexion.9 Histologically, it often demonstrates irregularly distributed, poorly defined melanocytes with pagetoid spread and dyscohesive nests (Figure 1).10 Melanoma metastasis occasionally can present as a soft-tissue mass and often stains positive for S-100 and vimentin, thus resembling GCT1,4; however, unlike melanoma, GCTs lack melanosomes and stain negative for more specific melanocyte markers, such as melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1).1,3,4

Atypical fibroxanthoma is a cutaneous neoplasm with fibrohistiocytic mesenchymal origin.11 These tumors typically arise on the head and neck in elderly individuals, particularly men with sun-damaged skin. They often present as superficial, rapidly growing nodules with the potential to ulcerate and bleed.11,12 Histologic features include pleomorphic spindle and epithelioid cells, whose nuclei appear hyperchromatic with atypical mitoses (Figure 2).12 Granular cell changes occur infrequently with AFXs, but in such cases immunohistochemistry can readily distinguish AFX from GCT. Although both tend to stain positive for CD68 and vimentin, AFXs lack S-100 protein and SOX10 expression that frequently is observed in GCTs.3,12

Xanthomas are localized lipid deposits in the connective tissue of the skin that often arise in association with dyslipidemia.13 They typically present as soft to semisolid yellow papules, plaques, or nodules. Their clinical appearance can resemble GCTs; however, histologic analysis enables differentiation with ease, as xanthomas demonstrate characteristic foam cells, consisting of lipid-laden macrophages (Figure 3).13

Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma is a rare dermal neoplasm, accounting for 2% to 3% of all sarcomas.14 They typically occur in White males during the fifth to seventh decades of life and often present as asymptomatic lesions on the lower extremities. They frequently arise from pilar smooth muscle. Unlike uterine and soft-tissue leiomyosarcoma, cutaneous leiomyosarcoma tends to follow an indolent course and rarely metastasizes.14 Histologically, these tumors display intersecting, well-defined, spindle-cell fascicles with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and cigar-shaped, blunt-ended nuclei (Figure 4).15 Occasionally, leiomyosarcomas can demonstrate cytoplasmic granularity due to lysosome accumulation4; nevertheless, the diagnosis usually can be elucidated by examining more typical histologic areas and utilizing immunohistochemistry, which often stains positive for α-smooth muscle actin, desmin, and h-caldesmon.4,15

- Fanburg-Smith JC, Meis-Kindblom JM, Fante R, et al. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:779-794.

- Moten AS, Movva S, von Mehren M, et al. Granular cell tumor experience at a comprehensive cancer center. J Surg Res. 2018;226:1-7.

- Machado I, Cruz J, Lavernia J, et al. Solitary, multiple, benign, atypical, or malignant: the "granular cell tumor" puzzle. Virchows Arch. 2016;468:527-538.

- Ordóñez NG. Granular cell tumor: a review and update. Adv Anat Pathol. 1999;6:186-203.

- Vaughan V, Ferringer T. Granular cell tumor. Cutis. 2014;94:275, 279-280.

- Van L, Parker SR. Multiple morphologically distinct cutaneous granular cell tumors occurring in a single patient. Cutis. 2016;97:E26-E29.

- Lack EE, Worsham GF, Callihan MD, et al. Granular cell tumor: a clinicopathologic study of 110 patients. J Surg Oncol. 1980;13:301-316.

- Bamps S, Oyen T, Legius E, et al. Multiple granular cell tumors in a child with Noonan syndrome. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2013;23:257-259.

- Rastrelli M, Tropea S, Rossi CR, et al. Melanoma: epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis and classification. In Vivo. 2014;28:1005-1011.

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneousmalignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(suppl 2):S34-S40.

- Soleymani T, Aasi SZ, Novoa R, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: updates on classification and management. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:253-259.

- Cardis MA, Ni J, Bhawan J. Granular cell differentiation: a review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2017;44:251-258.

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, et al. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations [published online April 29, 2014]. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158:181-188.

- Sandhu N, Sauvageau AP, Groman A, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: a SEER database analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:159-164.

- George S, Serrano C, Hensley ML, et al. Soft tissue and uterine leiomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:144-150.

- Fanburg-Smith JC, Meis-Kindblom JM, Fante R, et al. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:779-794.

- Moten AS, Movva S, von Mehren M, et al. Granular cell tumor experience at a comprehensive cancer center. J Surg Res. 2018;226:1-7.

- Machado I, Cruz J, Lavernia J, et al. Solitary, multiple, benign, atypical, or malignant: the "granular cell tumor" puzzle. Virchows Arch. 2016;468:527-538.

- Ordóñez NG. Granular cell tumor: a review and update. Adv Anat Pathol. 1999;6:186-203.

- Vaughan V, Ferringer T. Granular cell tumor. Cutis. 2014;94:275, 279-280.

- Van L, Parker SR. Multiple morphologically distinct cutaneous granular cell tumors occurring in a single patient. Cutis. 2016;97:E26-E29.

- Lack EE, Worsham GF, Callihan MD, et al. Granular cell tumor: a clinicopathologic study of 110 patients. J Surg Oncol. 1980;13:301-316.

- Bamps S, Oyen T, Legius E, et al. Multiple granular cell tumors in a child with Noonan syndrome. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2013;23:257-259.

- Rastrelli M, Tropea S, Rossi CR, et al. Melanoma: epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis and classification. In Vivo. 2014;28:1005-1011.

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneousmalignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(suppl 2):S34-S40.

- Soleymani T, Aasi SZ, Novoa R, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: updates on classification and management. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:253-259.

- Cardis MA, Ni J, Bhawan J. Granular cell differentiation: a review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2017;44:251-258.

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, et al. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations [published online April 29, 2014]. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158:181-188.

- Sandhu N, Sauvageau AP, Groman A, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: a SEER database analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:159-164.

- George S, Serrano C, Hensley ML, et al. Soft tissue and uterine leiomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:144-150.

A 26-year-old woman with a history of dysplastic nevi with severe atypia presented with a growth on the lower lip of 3 years’ duration. She denied any inciting event, such as prior trauma to the area, and reported that the lesion had been asymptomatic without a notable change in size. Physical examination revealed a translucent, soft, compressible cystic papule on the left inferior vermilion lip. Wide local excision following incisional biopsy was performed. Six months later, the patient returned to our clinic with a lesion on the right lateral tongue of 6 weeks’ duration as well as a 1-cm subcutaneous cyst in the left axilla of 6 months’ duration. Excisional biopsies of both lesions were performed for histopathologic analysis. Pathology results were similar among the lip, tongue, and axillary lesions. Immunohistochemistry revealed strong positive staining with antibodies to S-100 protein, SOX10, and CD68.

Linear Scarring Following Treatment With a 595-nm Pulsed Dye Laser

The pulsed dye laser (PDL) has been widely used in the treatment of port-wine stains, telangiectases, and other cutaneous vascular lesions since the late 1980s.1 This treatment modality generally is considered to have few serious adverse effects. There have been few reports of PDL treatment with subsequent complications,1-3 which may include ulceration developing immediately after treatment as well as scarring with a spotlike pattern caused by laser therapy. Numerous studies within the last 2 decades have documented improvement in the appearance of scars and telangiectases following treatment with PDL.4-6 We report the case of a 42-year-old woman who developed atrophic linear scarring of the nasal ala following cosmetic treatment with a 595-nm PDL.

Case Report

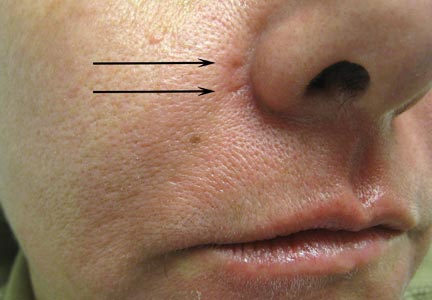

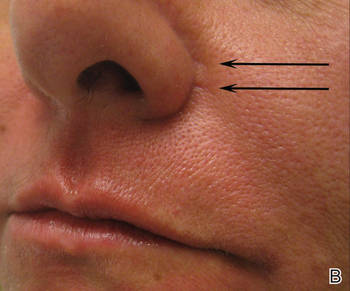

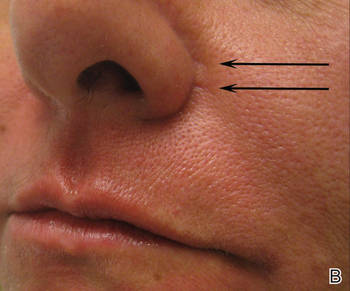

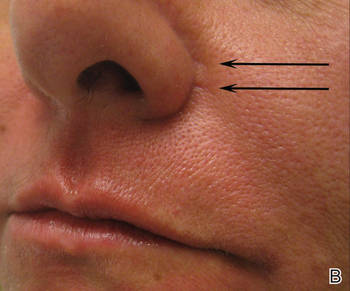

A healthy 42-year-old woman presented with atrophic linear scarring of the bilateral nasal alae following treatment with a 595-nm PDL. The patient had initially presented to an outside clinic 13 months prior for treatment of multiple telangiectases in this area. She received a single, 1-pass treatment with the 595-nm PDL (spot size, 3×10 mm; fluence, 11 J/cm2; pulse duration, 1.5 milliseconds) and returned to the clinic approximately 2 months later for a second treatment with the same settings. Seven months later she returned for a third treatment of the recalcitrant alar telangiectases with the same settings to maximize clinical outcome. Dynamic cooling was used during all treatment sessions with 30/20 setting. After the third treatment, immediate blanching followed by purpura was noted in the treated area. The patient initially was lost to follow-up but returned to the outside clinic 6 months later. On physical examination white atrophic skin with linear scarred depressions were noted on the nasofacial angle of the nasal alae (Figure). The patient denied any postoperative complications such as scabbing, blistering, or pain. At that time she was referred to our office for evaluation, and treatment with a hyaluronic acid filler was initiated. Examination and medical history were otherwise unremarkable at the time of presentation to our office. Resolution of skin atrophy and excellent correction of the depressions was maintained at a follow-up 2 months later. She declined photographs at that time.

|

|

|

| Right (A), left (B), and frontal (C) views of atrophic linear scars (arrows) caused by high-energy purpuric doses of a 595-nm pulsed dye laser. |

Comment

The PDL often is employed in the treatment of vascular lesions such as telangiectases.7 The most common adverse effect is postinflammatory hyperpigmentation; atrophic and hypertrophic scarring rarely are seen.1,8,9 In a study of adverse reactions following pulsed tunable dye laser treatment of port-wine stains in 701 patients, atrophic scarring occurred in 5% of patients and 0.83% of treatments; clinical resolution was noted over the following 6 to 12 months in 30% of patients.8

Following treatment with the PDL, thermal damage occurs primarily to vessel walls with little or no damage to surrounding nonvascular structures. The depth of vascular injury after PDL treatment has been shown to be approximately 1.2 mm.10

Although scarring in our patient was a result of PDL treatment, PDL therapy is commonly used as a treatment option for scars. In conjunction with intralesional steroids directed at flattening hypertrophic scars and keloids, the PDL is used to reduce scar redness and enhance pliability.11 Although redness and telangiectases that develop in surgical scars usually spontaneously remit, they often can show prolonged and incomplete healing. Surgical scars have been shown to benefit from PDL treatment as it advances the end point closer to the complete absence of redness.11-14

The off-label use of hyaluronic acid filler in our patient is notable, as the injection of the nasal ala is not an ordinary injection site for this filler material. It can be associated with risk for necrosis and thus must be performed by an experienced injector combined with informed consent from the patient. The nasal ala is particularly sebaceous and consists of fibrofatty tissue, which is not easily amenable to infiltration. Despite this usual characteristic of the nasal area, the scarring in our patient was fortuitously lateral to the nasal ala and easily filled with hyaluronic acid, as a linear tract was created by the high energies and linear spot size used to treat the patient.

We report a 595-nm PDL treatment that resulted in atrophic linear scarring in a distribution mimicking the linear spot size used by the laser operator. No adverse effects were noted following the first 2 treatments, thereby suggesting either a cumulative insult or more likely cutaneous necrosis from excessive fluence and short pulse durations due to operator inexperience. Other possibilities include rapid and overlapping passes with the laser leading to bulk heating and thermal injury to the skin.

Alternative laser treatment protocols have been proposed in the literature. Rohrer et al15 recommended multiple passes at subpurpuric doses for treatment of facial telangiectases with the PDL. It has been suggested that multiple stacked pulses at lower fluences may have similar effects on targets as a single pulse at a higher fluence, thereby minimizing thermal injury and leading to decreased risk for adverse events such as scarring. When treating vascular lesions such as telangiectases, increasing the fluence will increase the risk for purpura due to the constant pulse duration. Stacking pulses of lower fluence may have the advantage of heating vessels to a critical temperature without creating purpura, leading to similar clearance rates with decreased adverse risk profiles.15

It may be better to err on the side of safety by performing a greater number of treatment sessions with increased pulse width and decreased fluence (subpurpuric treatment settings) to minimize the risk for atrophic scarring from treatment with the PDL. Treating superficial facial telangiectases with a pulse-stacking technique may improve clinical results without a remarkable increase in adverse effects. It may be wrongfully intuitive to try to maximize results by using high fluences and purpuric narrow pulse durations; this case report reiterates the danger of using these settings in an attempt to rapidly achieve clearance of telangiectases. Lastly, this case underscores the value of verbal and written postoperative instructions that should be given to every patient prior to undergoing laser therapy. Specifically, with regard to our case, the laser operator must be aware at all times of potential adverse events, which may be foreseen during treatment if persistent or prolonged blanching and/or blistering occurs. The physician operator and patient must be prepared to rapidly respond to adverse reactions such as skin necrosis or blistering. Meticulous wound care is necessary if skin breakdown occurs. We recommend using a hydrating petrolatum ointment or a topical emulsion to minimize the risks for scarring, if possible.

1. Levine VJ, Geronemus RG. Adverse effects associated with the 577- and 585-nanometer pulsed dye laser in the treatment of cutaneous vascular lesions: a study of 500 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:613-617.

2. Witman PM, Wagner AM, Scherer K, et al. Complications following pulsed dye laser treatment of superficial hemangiomas. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:116-123.

3. Sommer S, Sheehan-Dare RA. Atrophie blanche-like scarring after pulsed dye laser treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:100-102.

4. Dover JS, Geronemus R, Stern RS, et al. Dye laser treatment of port-wine stains: comparison of the continuous-wave dye laser with a robotized scanning device and the pulsed dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(2, pt 1):237-240.

5. Dierickx C, Goldman MP, Fitzpatrick RE. Laser treatment of erythematous/hypertrophic and pigmented scars in 26 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95:84-90.

6. Wittenberg GP, Fabian BG, Bogomilsky JL, et al. Prospective, single-blind, randomized, controlled study to assess the efficacy of the 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser and silicone gel sheeting in hypertrophic scar treatment. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1049-1055.

7. Ross EV, Uebelhoer NS, Domankevitz Y. Use of a novel pulse dye laser for rapid single-pass purpura-free treatment of telangiectases. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1466-1469.

8. Seukeran DC, Collins P, Sheehan-Dare RA. Adverse reactions following pulsed tunable dye laser treatment of port wine stains in 701 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:725-729.

9. Wlotzke U, Hohenleutner U, Abd-El-Raheem TA, et al. Side-effects and complications of flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser therapy of port-wine stains. a prospective study. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:475-480.

10. Tan OT, Morrison P, Kurban AK. 585 nm for the treatment of port-wine stains. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:1112-1117.

11. Alam M, Pon K, Van Laborde S, et al. Clinical effect of a single pulsed dye laser treatment of fresh surgical scars: randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:21-25.

12. Bowes LE, Nouri K, Berman B, et al. Treatment of pigmented hypertrophic scars with the 585 nm pulsed dye laser and the 532 nm frequency-doubled Nd:YAG laser in the Q-switched and variable pulse modes: a comparative study. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:714-719.

13. Alster TS, Williams CM. Treatment of keloid sternotomy scars with 585 nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser. Lancet. 1995;345:1198-1200.

14. Manuskiatti W, Fitzpatrick RE. Treatment response of keloidal and hypertrophic sternotomy scars: comparison among intralesional corticosteroid, 5-fluorouracil, and 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser treatments. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1149-1155.

15. Rohrer TE, Chatrath V, Iyengar V. Does pulse stacking improve the results of treatment with variable-pulse pulsed-dye lasers? Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(2, pt 1):163-167.

The pulsed dye laser (PDL) has been widely used in the treatment of port-wine stains, telangiectases, and other cutaneous vascular lesions since the late 1980s.1 This treatment modality generally is considered to have few serious adverse effects. There have been few reports of PDL treatment with subsequent complications,1-3 which may include ulceration developing immediately after treatment as well as scarring with a spotlike pattern caused by laser therapy. Numerous studies within the last 2 decades have documented improvement in the appearance of scars and telangiectases following treatment with PDL.4-6 We report the case of a 42-year-old woman who developed atrophic linear scarring of the nasal ala following cosmetic treatment with a 595-nm PDL.

Case Report

A healthy 42-year-old woman presented with atrophic linear scarring of the bilateral nasal alae following treatment with a 595-nm PDL. The patient had initially presented to an outside clinic 13 months prior for treatment of multiple telangiectases in this area. She received a single, 1-pass treatment with the 595-nm PDL (spot size, 3×10 mm; fluence, 11 J/cm2; pulse duration, 1.5 milliseconds) and returned to the clinic approximately 2 months later for a second treatment with the same settings. Seven months later she returned for a third treatment of the recalcitrant alar telangiectases with the same settings to maximize clinical outcome. Dynamic cooling was used during all treatment sessions with 30/20 setting. After the third treatment, immediate blanching followed by purpura was noted in the treated area. The patient initially was lost to follow-up but returned to the outside clinic 6 months later. On physical examination white atrophic skin with linear scarred depressions were noted on the nasofacial angle of the nasal alae (Figure). The patient denied any postoperative complications such as scabbing, blistering, or pain. At that time she was referred to our office for evaluation, and treatment with a hyaluronic acid filler was initiated. Examination and medical history were otherwise unremarkable at the time of presentation to our office. Resolution of skin atrophy and excellent correction of the depressions was maintained at a follow-up 2 months later. She declined photographs at that time.

|

|

|

| Right (A), left (B), and frontal (C) views of atrophic linear scars (arrows) caused by high-energy purpuric doses of a 595-nm pulsed dye laser. |

Comment

The PDL often is employed in the treatment of vascular lesions such as telangiectases.7 The most common adverse effect is postinflammatory hyperpigmentation; atrophic and hypertrophic scarring rarely are seen.1,8,9 In a study of adverse reactions following pulsed tunable dye laser treatment of port-wine stains in 701 patients, atrophic scarring occurred in 5% of patients and 0.83% of treatments; clinical resolution was noted over the following 6 to 12 months in 30% of patients.8

Following treatment with the PDL, thermal damage occurs primarily to vessel walls with little or no damage to surrounding nonvascular structures. The depth of vascular injury after PDL treatment has been shown to be approximately 1.2 mm.10

Although scarring in our patient was a result of PDL treatment, PDL therapy is commonly used as a treatment option for scars. In conjunction with intralesional steroids directed at flattening hypertrophic scars and keloids, the PDL is used to reduce scar redness and enhance pliability.11 Although redness and telangiectases that develop in surgical scars usually spontaneously remit, they often can show prolonged and incomplete healing. Surgical scars have been shown to benefit from PDL treatment as it advances the end point closer to the complete absence of redness.11-14

The off-label use of hyaluronic acid filler in our patient is notable, as the injection of the nasal ala is not an ordinary injection site for this filler material. It can be associated with risk for necrosis and thus must be performed by an experienced injector combined with informed consent from the patient. The nasal ala is particularly sebaceous and consists of fibrofatty tissue, which is not easily amenable to infiltration. Despite this usual characteristic of the nasal area, the scarring in our patient was fortuitously lateral to the nasal ala and easily filled with hyaluronic acid, as a linear tract was created by the high energies and linear spot size used to treat the patient.

We report a 595-nm PDL treatment that resulted in atrophic linear scarring in a distribution mimicking the linear spot size used by the laser operator. No adverse effects were noted following the first 2 treatments, thereby suggesting either a cumulative insult or more likely cutaneous necrosis from excessive fluence and short pulse durations due to operator inexperience. Other possibilities include rapid and overlapping passes with the laser leading to bulk heating and thermal injury to the skin.

Alternative laser treatment protocols have been proposed in the literature. Rohrer et al15 recommended multiple passes at subpurpuric doses for treatment of facial telangiectases with the PDL. It has been suggested that multiple stacked pulses at lower fluences may have similar effects on targets as a single pulse at a higher fluence, thereby minimizing thermal injury and leading to decreased risk for adverse events such as scarring. When treating vascular lesions such as telangiectases, increasing the fluence will increase the risk for purpura due to the constant pulse duration. Stacking pulses of lower fluence may have the advantage of heating vessels to a critical temperature without creating purpura, leading to similar clearance rates with decreased adverse risk profiles.15

It may be better to err on the side of safety by performing a greater number of treatment sessions with increased pulse width and decreased fluence (subpurpuric treatment settings) to minimize the risk for atrophic scarring from treatment with the PDL. Treating superficial facial telangiectases with a pulse-stacking technique may improve clinical results without a remarkable increase in adverse effects. It may be wrongfully intuitive to try to maximize results by using high fluences and purpuric narrow pulse durations; this case report reiterates the danger of using these settings in an attempt to rapidly achieve clearance of telangiectases. Lastly, this case underscores the value of verbal and written postoperative instructions that should be given to every patient prior to undergoing laser therapy. Specifically, with regard to our case, the laser operator must be aware at all times of potential adverse events, which may be foreseen during treatment if persistent or prolonged blanching and/or blistering occurs. The physician operator and patient must be prepared to rapidly respond to adverse reactions such as skin necrosis or blistering. Meticulous wound care is necessary if skin breakdown occurs. We recommend using a hydrating petrolatum ointment or a topical emulsion to minimize the risks for scarring, if possible.

The pulsed dye laser (PDL) has been widely used in the treatment of port-wine stains, telangiectases, and other cutaneous vascular lesions since the late 1980s.1 This treatment modality generally is considered to have few serious adverse effects. There have been few reports of PDL treatment with subsequent complications,1-3 which may include ulceration developing immediately after treatment as well as scarring with a spotlike pattern caused by laser therapy. Numerous studies within the last 2 decades have documented improvement in the appearance of scars and telangiectases following treatment with PDL.4-6 We report the case of a 42-year-old woman who developed atrophic linear scarring of the nasal ala following cosmetic treatment with a 595-nm PDL.

Case Report

A healthy 42-year-old woman presented with atrophic linear scarring of the bilateral nasal alae following treatment with a 595-nm PDL. The patient had initially presented to an outside clinic 13 months prior for treatment of multiple telangiectases in this area. She received a single, 1-pass treatment with the 595-nm PDL (spot size, 3×10 mm; fluence, 11 J/cm2; pulse duration, 1.5 milliseconds) and returned to the clinic approximately 2 months later for a second treatment with the same settings. Seven months later she returned for a third treatment of the recalcitrant alar telangiectases with the same settings to maximize clinical outcome. Dynamic cooling was used during all treatment sessions with 30/20 setting. After the third treatment, immediate blanching followed by purpura was noted in the treated area. The patient initially was lost to follow-up but returned to the outside clinic 6 months later. On physical examination white atrophic skin with linear scarred depressions were noted on the nasofacial angle of the nasal alae (Figure). The patient denied any postoperative complications such as scabbing, blistering, or pain. At that time she was referred to our office for evaluation, and treatment with a hyaluronic acid filler was initiated. Examination and medical history were otherwise unremarkable at the time of presentation to our office. Resolution of skin atrophy and excellent correction of the depressions was maintained at a follow-up 2 months later. She declined photographs at that time.

|

|

|

| Right (A), left (B), and frontal (C) views of atrophic linear scars (arrows) caused by high-energy purpuric doses of a 595-nm pulsed dye laser. |

Comment

The PDL often is employed in the treatment of vascular lesions such as telangiectases.7 The most common adverse effect is postinflammatory hyperpigmentation; atrophic and hypertrophic scarring rarely are seen.1,8,9 In a study of adverse reactions following pulsed tunable dye laser treatment of port-wine stains in 701 patients, atrophic scarring occurred in 5% of patients and 0.83% of treatments; clinical resolution was noted over the following 6 to 12 months in 30% of patients.8

Following treatment with the PDL, thermal damage occurs primarily to vessel walls with little or no damage to surrounding nonvascular structures. The depth of vascular injury after PDL treatment has been shown to be approximately 1.2 mm.10

Although scarring in our patient was a result of PDL treatment, PDL therapy is commonly used as a treatment option for scars. In conjunction with intralesional steroids directed at flattening hypertrophic scars and keloids, the PDL is used to reduce scar redness and enhance pliability.11 Although redness and telangiectases that develop in surgical scars usually spontaneously remit, they often can show prolonged and incomplete healing. Surgical scars have been shown to benefit from PDL treatment as it advances the end point closer to the complete absence of redness.11-14

The off-label use of hyaluronic acid filler in our patient is notable, as the injection of the nasal ala is not an ordinary injection site for this filler material. It can be associated with risk for necrosis and thus must be performed by an experienced injector combined with informed consent from the patient. The nasal ala is particularly sebaceous and consists of fibrofatty tissue, which is not easily amenable to infiltration. Despite this usual characteristic of the nasal area, the scarring in our patient was fortuitously lateral to the nasal ala and easily filled with hyaluronic acid, as a linear tract was created by the high energies and linear spot size used to treat the patient.

We report a 595-nm PDL treatment that resulted in atrophic linear scarring in a distribution mimicking the linear spot size used by the laser operator. No adverse effects were noted following the first 2 treatments, thereby suggesting either a cumulative insult or more likely cutaneous necrosis from excessive fluence and short pulse durations due to operator inexperience. Other possibilities include rapid and overlapping passes with the laser leading to bulk heating and thermal injury to the skin.

Alternative laser treatment protocols have been proposed in the literature. Rohrer et al15 recommended multiple passes at subpurpuric doses for treatment of facial telangiectases with the PDL. It has been suggested that multiple stacked pulses at lower fluences may have similar effects on targets as a single pulse at a higher fluence, thereby minimizing thermal injury and leading to decreased risk for adverse events such as scarring. When treating vascular lesions such as telangiectases, increasing the fluence will increase the risk for purpura due to the constant pulse duration. Stacking pulses of lower fluence may have the advantage of heating vessels to a critical temperature without creating purpura, leading to similar clearance rates with decreased adverse risk profiles.15

It may be better to err on the side of safety by performing a greater number of treatment sessions with increased pulse width and decreased fluence (subpurpuric treatment settings) to minimize the risk for atrophic scarring from treatment with the PDL. Treating superficial facial telangiectases with a pulse-stacking technique may improve clinical results without a remarkable increase in adverse effects. It may be wrongfully intuitive to try to maximize results by using high fluences and purpuric narrow pulse durations; this case report reiterates the danger of using these settings in an attempt to rapidly achieve clearance of telangiectases. Lastly, this case underscores the value of verbal and written postoperative instructions that should be given to every patient prior to undergoing laser therapy. Specifically, with regard to our case, the laser operator must be aware at all times of potential adverse events, which may be foreseen during treatment if persistent or prolonged blanching and/or blistering occurs. The physician operator and patient must be prepared to rapidly respond to adverse reactions such as skin necrosis or blistering. Meticulous wound care is necessary if skin breakdown occurs. We recommend using a hydrating petrolatum ointment or a topical emulsion to minimize the risks for scarring, if possible.

1. Levine VJ, Geronemus RG. Adverse effects associated with the 577- and 585-nanometer pulsed dye laser in the treatment of cutaneous vascular lesions: a study of 500 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:613-617.

2. Witman PM, Wagner AM, Scherer K, et al. Complications following pulsed dye laser treatment of superficial hemangiomas. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:116-123.

3. Sommer S, Sheehan-Dare RA. Atrophie blanche-like scarring after pulsed dye laser treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:100-102.

4. Dover JS, Geronemus R, Stern RS, et al. Dye laser treatment of port-wine stains: comparison of the continuous-wave dye laser with a robotized scanning device and the pulsed dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(2, pt 1):237-240.

5. Dierickx C, Goldman MP, Fitzpatrick RE. Laser treatment of erythematous/hypertrophic and pigmented scars in 26 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95:84-90.

6. Wittenberg GP, Fabian BG, Bogomilsky JL, et al. Prospective, single-blind, randomized, controlled study to assess the efficacy of the 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser and silicone gel sheeting in hypertrophic scar treatment. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1049-1055.

7. Ross EV, Uebelhoer NS, Domankevitz Y. Use of a novel pulse dye laser for rapid single-pass purpura-free treatment of telangiectases. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1466-1469.

8. Seukeran DC, Collins P, Sheehan-Dare RA. Adverse reactions following pulsed tunable dye laser treatment of port wine stains in 701 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:725-729.

9. Wlotzke U, Hohenleutner U, Abd-El-Raheem TA, et al. Side-effects and complications of flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser therapy of port-wine stains. a prospective study. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:475-480.

10. Tan OT, Morrison P, Kurban AK. 585 nm for the treatment of port-wine stains. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:1112-1117.

11. Alam M, Pon K, Van Laborde S, et al. Clinical effect of a single pulsed dye laser treatment of fresh surgical scars: randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:21-25.

12. Bowes LE, Nouri K, Berman B, et al. Treatment of pigmented hypertrophic scars with the 585 nm pulsed dye laser and the 532 nm frequency-doubled Nd:YAG laser in the Q-switched and variable pulse modes: a comparative study. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:714-719.

13. Alster TS, Williams CM. Treatment of keloid sternotomy scars with 585 nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser. Lancet. 1995;345:1198-1200.

14. Manuskiatti W, Fitzpatrick RE. Treatment response of keloidal and hypertrophic sternotomy scars: comparison among intralesional corticosteroid, 5-fluorouracil, and 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser treatments. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1149-1155.

15. Rohrer TE, Chatrath V, Iyengar V. Does pulse stacking improve the results of treatment with variable-pulse pulsed-dye lasers? Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(2, pt 1):163-167.

1. Levine VJ, Geronemus RG. Adverse effects associated with the 577- and 585-nanometer pulsed dye laser in the treatment of cutaneous vascular lesions: a study of 500 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:613-617.

2. Witman PM, Wagner AM, Scherer K, et al. Complications following pulsed dye laser treatment of superficial hemangiomas. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:116-123.

3. Sommer S, Sheehan-Dare RA. Atrophie blanche-like scarring after pulsed dye laser treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:100-102.

4. Dover JS, Geronemus R, Stern RS, et al. Dye laser treatment of port-wine stains: comparison of the continuous-wave dye laser with a robotized scanning device and the pulsed dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(2, pt 1):237-240.

5. Dierickx C, Goldman MP, Fitzpatrick RE. Laser treatment of erythematous/hypertrophic and pigmented scars in 26 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95:84-90.

6. Wittenberg GP, Fabian BG, Bogomilsky JL, et al. Prospective, single-blind, randomized, controlled study to assess the efficacy of the 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser and silicone gel sheeting in hypertrophic scar treatment. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1049-1055.

7. Ross EV, Uebelhoer NS, Domankevitz Y. Use of a novel pulse dye laser for rapid single-pass purpura-free treatment of telangiectases. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1466-1469.

8. Seukeran DC, Collins P, Sheehan-Dare RA. Adverse reactions following pulsed tunable dye laser treatment of port wine stains in 701 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:725-729.

9. Wlotzke U, Hohenleutner U, Abd-El-Raheem TA, et al. Side-effects and complications of flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser therapy of port-wine stains. a prospective study. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:475-480.

10. Tan OT, Morrison P, Kurban AK. 585 nm for the treatment of port-wine stains. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:1112-1117.

11. Alam M, Pon K, Van Laborde S, et al. Clinical effect of a single pulsed dye laser treatment of fresh surgical scars: randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:21-25.

12. Bowes LE, Nouri K, Berman B, et al. Treatment of pigmented hypertrophic scars with the 585 nm pulsed dye laser and the 532 nm frequency-doubled Nd:YAG laser in the Q-switched and variable pulse modes: a comparative study. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:714-719.

13. Alster TS, Williams CM. Treatment of keloid sternotomy scars with 585 nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser. Lancet. 1995;345:1198-1200.

14. Manuskiatti W, Fitzpatrick RE. Treatment response of keloidal and hypertrophic sternotomy scars: comparison among intralesional corticosteroid, 5-fluorouracil, and 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser treatments. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1149-1155.

15. Rohrer TE, Chatrath V, Iyengar V. Does pulse stacking improve the results of treatment with variable-pulse pulsed-dye lasers? Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(2, pt 1):163-167.

Practice Points

- Lasers should be used by experienced operators and treatments should be tailored to individual patient needs.

- Multiple passes at subpurpuric settings with the pulsed dye laser may lead to safer results with fewer adverse events and at the same time more tolerable treatments for the patient by minimizing downtime associated with purpura.

- Although scarring is rare, it can occur and should be part of the patient’s informed consent prior to treatment.