User login

The Diagnosis: Targetoid Hemosiderotic Hemangioma

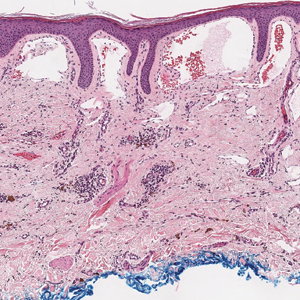

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma (THH), also known as hobnail hemangioma, is a benign vascular tumor that usually occurs in young or middle-aged adults. It most commonly presents on the extremities or trunk as an isolated red-brown plaque or papule.1,2 Histologically, THH is characterized by superficial dilated ectatic vessels with underlying proliferating vascular channels lined by plump hobnail endothelial cells.1 Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma typically involves the dermis and spares the subcutis. The vascular channels may contain erythrocytes as well as pale eosinophilic lymph, as seen in our patient (quiz image). The deeper dermis contains vascular spaces that are more angulated and smaller and appear to be dissecting through the collagen bundles or collapsed.1,3 A variable amount of hemosiderin deposition and extravasated erythrocytes are seen.2,3 Histologic features evolve with the age of the lesion. Increasing amounts of hemosiderin deposition and erythrocyte extravasation may correspond histologically to the recent clinical color change reported by the patient.

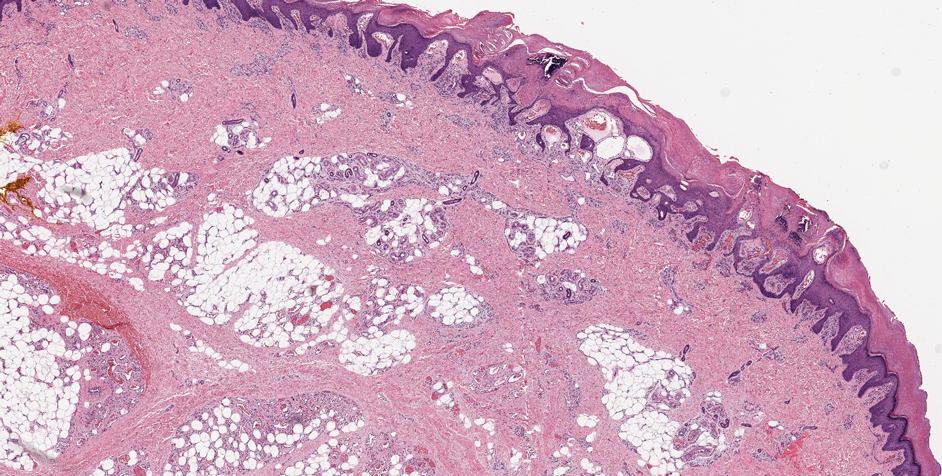

Verrucous hemangioma is a rare congenital vascular abnormality that is characterized by dilated vessels in the papillary dermis along with acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and irregular papillomatosis, as seen in angiokeratoma.4 However, the vascular proliferation composed of variably sized, thin-walled capillaries extends into the deep dermis as well as the subcutis (Figure 1). Verrucous hemangioma most commonly is reported on the legs and generally starts as a violaceous patch that progresses into a hyperkeratotic verrucous plaque or nodule.5,6

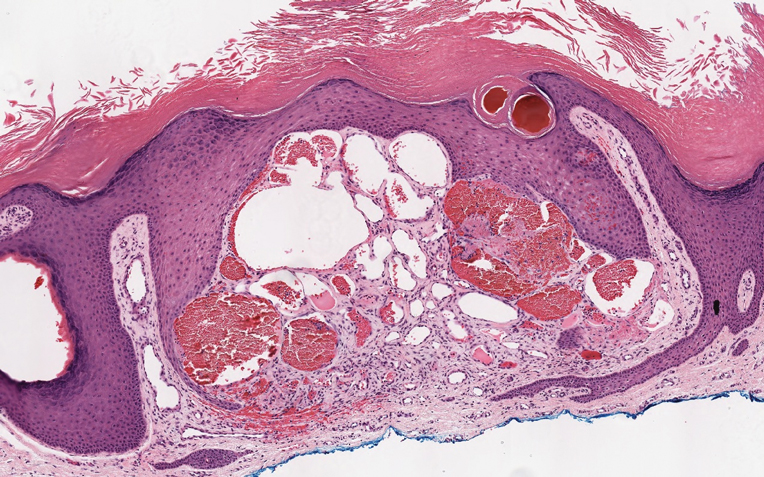

Angiokeratoma is characterized by superficial vascular ectasia of the papillary dermis in association with overlying acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and rete elongation.7 The dilated vascular spaces appear encircled by the epidermis (Figure 2). Intravascular thrombosis can be seen within the ectatic vessels.7 In contrast to verrucous hemangioma, angiokeratoma is limited to the papillary dermis. Therefore, obtaining a biopsy of sufficient depth is necessary for differentiation.8 There are 5 clinical presentations of angiokeratoma: sporadic, angiokeratoma of Mibelli, angiokeratoma of Fordyce, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, and angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (Fabry disease). Angiokeratomas may present on the lower extremities, tongue, trunk, and scrotum as hyperkeratotic, dark red to purple or black papules.7

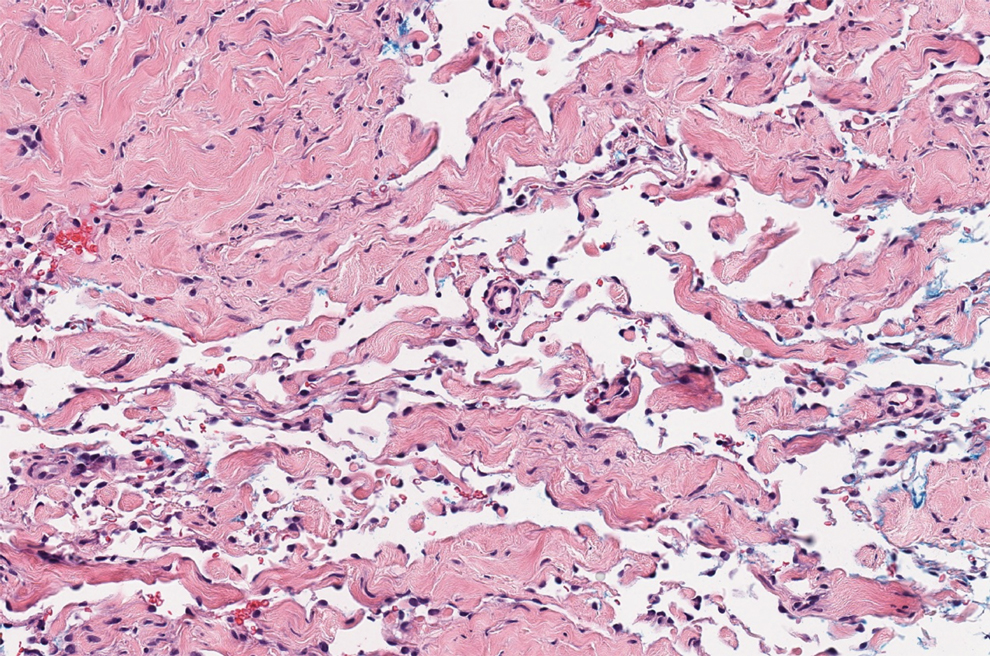

There are 3 clinical stages of Kaposi sarcoma: patch, plaque, and nodular stages. The patch stage is characterized histologically by vascular channels that dissect through the dermis and extend around native vessels (the promontory sign)(Figure 3).9,10 These features can show histologic overlap with THH. The plaque stage shows a more diffuse dermal vascular proliferation, increased cellularity of spindle cells, and possible extension into the subcutis.9,10 Focal plasma cells, hemosiderin, and extravasated red blood cells can be seen. The nodular stage is characterized by a proliferation of spindle cells with red blood cells squeezed between slitlike vascular spaces, hyaline globules, and scattered mitotic figures, but not atypical forms.10 In this stage, plasma cells and hemosiderin are more readily identifiable. A biopsy from the nodular stage is unlikely to enter the histologic differential diagnosis with THH. Clinically, there are 4 variants of Kaposi sarcoma: the classic or sporadic form, an endemic form, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated. Overall, it is more common in males and can occur at any age.10 Human herpesvirus 8 is seen in all forms, and infected cells can be highlighted by the immunohistochemical stain for latent nuclear antigen 1.9,10

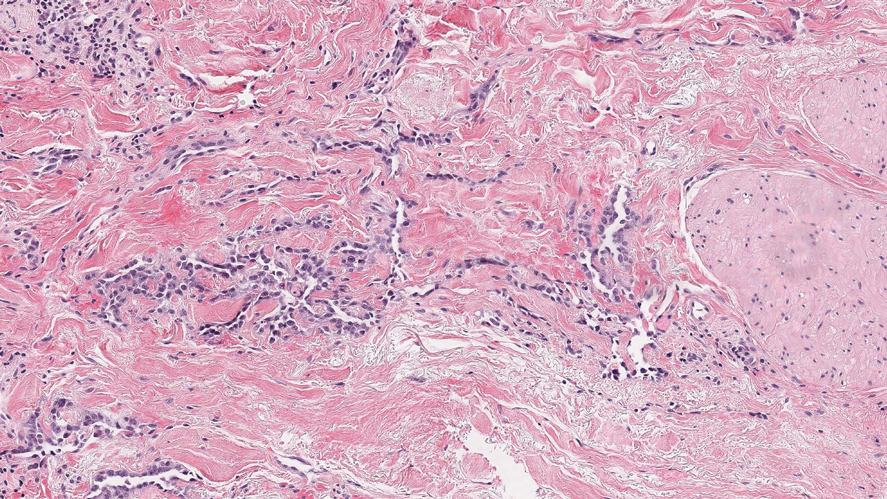

Angiosarcoma is a malignant endothelial tumor of soft tissue, skin, bone, and visceral organs.11,12 Clinically, cutaneous angiosarcoma can present in a variety of ways, including single or multiple bluish red lesions that can ulcerate or bleed; violaceous nodules or plaques; and hematomalike lesions that can mimic epithelial neoplasms including squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma.11,13,14 The cutaneous lesions most commonly occur on sun-exposed skin, particularly on the face and scalp.12 Other clinical variants that are important to recognize are postradiation angiosarcoma, characterized by MYC gene amplification, and lymphedema-associated angiosarcoma (Stewart-Treves syndrome). Angiosarcoma can have a variety of morphologic features, ranging from well to poorly differentiated. Classically, angiosarcoma is characterized by infiltrating vascular spaces lined by atypical endothelial cells (Figure 4). Poorly differentiated angiosarcoma can demonstrate spindle, epithelioid, or polygonal cells with increased mitotic activity, pleomorphism, and irregular vascular spaces.11 Endothelial markers such as ERG (erythroblast transformation specific-related gene)(nuclear) and CD31 (membranous) can be used to aid in the diagnosis of a poorly differentiated lesion. Epithelioid angiosarcoma also occasionally stains with cytokeratins.13,14

- Joyce JC, Keith PJ, Szabo S, et al. Superficial hemosiderotic lymphovascular malformation (hobnail hemangioma): a report of six cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:281-285.

- Sahin MT, Demir MA, Gunduz K, et al. Targetoid haemosiderotic haemangioma: dermoscopic monitoring of three cases and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:672-676.

- Kakizaki P, Valente NY, Paiva DL, et al. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma--case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:956-959.

- Oppermann K, Boff AL, Bonamigo RR. Verrucous hemangioma and histopathological differential diagnosis with angiokeratoma circumscriptum neviforme. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:712-715.

- Boccara, O, Ariche-Maman, S, Hadj-Rabia, S, et al. Verrucous hemangioma (also known as verrucous venous malformation): a vascular anomaly frequently misdiagnosed as a lymphatic malformation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E378-E381.

- Mestre T, Amaro C, Freitas I. Verrucous haemangioma: a diagnosis to consider [published online June 4, 2014]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-204612

- Ivy H, Julian CA. Angiokeratoma circumscriptum. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549769/

- Shetty S, Geetha V, Rao R, et al. Verrucous hemangioma: importance of a deeper biopsy. Indian J Dermatopathol Diagn Dermatol. 2014;1:99-100.

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Cancer, Kaposi sarcoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534839/

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Cao J, Wang J, He C, et al. Angiosarcoma: a review of diagnosis and current treatment. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:2303-2313.

- Papke DJ Jr, Hornick JL. What is new in endothelial neoplasia? Virchows Arch. 2020;476:17-28.

- Ambujam S, Audhya M, Reddy A, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head, neck, and face of the elderly in type 5 skin. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6:45-47.

- Shustef E, Kazlouskaya V, Prieto VG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a current update. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70:917-925.

The Diagnosis: Targetoid Hemosiderotic Hemangioma

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma (THH), also known as hobnail hemangioma, is a benign vascular tumor that usually occurs in young or middle-aged adults. It most commonly presents on the extremities or trunk as an isolated red-brown plaque or papule.1,2 Histologically, THH is characterized by superficial dilated ectatic vessels with underlying proliferating vascular channels lined by plump hobnail endothelial cells.1 Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma typically involves the dermis and spares the subcutis. The vascular channels may contain erythrocytes as well as pale eosinophilic lymph, as seen in our patient (quiz image). The deeper dermis contains vascular spaces that are more angulated and smaller and appear to be dissecting through the collagen bundles or collapsed.1,3 A variable amount of hemosiderin deposition and extravasated erythrocytes are seen.2,3 Histologic features evolve with the age of the lesion. Increasing amounts of hemosiderin deposition and erythrocyte extravasation may correspond histologically to the recent clinical color change reported by the patient.

Verrucous hemangioma is a rare congenital vascular abnormality that is characterized by dilated vessels in the papillary dermis along with acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and irregular papillomatosis, as seen in angiokeratoma.4 However, the vascular proliferation composed of variably sized, thin-walled capillaries extends into the deep dermis as well as the subcutis (Figure 1). Verrucous hemangioma most commonly is reported on the legs and generally starts as a violaceous patch that progresses into a hyperkeratotic verrucous plaque or nodule.5,6

Angiokeratoma is characterized by superficial vascular ectasia of the papillary dermis in association with overlying acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and rete elongation.7 The dilated vascular spaces appear encircled by the epidermis (Figure 2). Intravascular thrombosis can be seen within the ectatic vessels.7 In contrast to verrucous hemangioma, angiokeratoma is limited to the papillary dermis. Therefore, obtaining a biopsy of sufficient depth is necessary for differentiation.8 There are 5 clinical presentations of angiokeratoma: sporadic, angiokeratoma of Mibelli, angiokeratoma of Fordyce, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, and angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (Fabry disease). Angiokeratomas may present on the lower extremities, tongue, trunk, and scrotum as hyperkeratotic, dark red to purple or black papules.7

There are 3 clinical stages of Kaposi sarcoma: patch, plaque, and nodular stages. The patch stage is characterized histologically by vascular channels that dissect through the dermis and extend around native vessels (the promontory sign)(Figure 3).9,10 These features can show histologic overlap with THH. The plaque stage shows a more diffuse dermal vascular proliferation, increased cellularity of spindle cells, and possible extension into the subcutis.9,10 Focal plasma cells, hemosiderin, and extravasated red blood cells can be seen. The nodular stage is characterized by a proliferation of spindle cells with red blood cells squeezed between slitlike vascular spaces, hyaline globules, and scattered mitotic figures, but not atypical forms.10 In this stage, plasma cells and hemosiderin are more readily identifiable. A biopsy from the nodular stage is unlikely to enter the histologic differential diagnosis with THH. Clinically, there are 4 variants of Kaposi sarcoma: the classic or sporadic form, an endemic form, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated. Overall, it is more common in males and can occur at any age.10 Human herpesvirus 8 is seen in all forms, and infected cells can be highlighted by the immunohistochemical stain for latent nuclear antigen 1.9,10

Angiosarcoma is a malignant endothelial tumor of soft tissue, skin, bone, and visceral organs.11,12 Clinically, cutaneous angiosarcoma can present in a variety of ways, including single or multiple bluish red lesions that can ulcerate or bleed; violaceous nodules or plaques; and hematomalike lesions that can mimic epithelial neoplasms including squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma.11,13,14 The cutaneous lesions most commonly occur on sun-exposed skin, particularly on the face and scalp.12 Other clinical variants that are important to recognize are postradiation angiosarcoma, characterized by MYC gene amplification, and lymphedema-associated angiosarcoma (Stewart-Treves syndrome). Angiosarcoma can have a variety of morphologic features, ranging from well to poorly differentiated. Classically, angiosarcoma is characterized by infiltrating vascular spaces lined by atypical endothelial cells (Figure 4). Poorly differentiated angiosarcoma can demonstrate spindle, epithelioid, or polygonal cells with increased mitotic activity, pleomorphism, and irregular vascular spaces.11 Endothelial markers such as ERG (erythroblast transformation specific-related gene)(nuclear) and CD31 (membranous) can be used to aid in the diagnosis of a poorly differentiated lesion. Epithelioid angiosarcoma also occasionally stains with cytokeratins.13,14

The Diagnosis: Targetoid Hemosiderotic Hemangioma

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma (THH), also known as hobnail hemangioma, is a benign vascular tumor that usually occurs in young or middle-aged adults. It most commonly presents on the extremities or trunk as an isolated red-brown plaque or papule.1,2 Histologically, THH is characterized by superficial dilated ectatic vessels with underlying proliferating vascular channels lined by plump hobnail endothelial cells.1 Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma typically involves the dermis and spares the subcutis. The vascular channels may contain erythrocytes as well as pale eosinophilic lymph, as seen in our patient (quiz image). The deeper dermis contains vascular spaces that are more angulated and smaller and appear to be dissecting through the collagen bundles or collapsed.1,3 A variable amount of hemosiderin deposition and extravasated erythrocytes are seen.2,3 Histologic features evolve with the age of the lesion. Increasing amounts of hemosiderin deposition and erythrocyte extravasation may correspond histologically to the recent clinical color change reported by the patient.

Verrucous hemangioma is a rare congenital vascular abnormality that is characterized by dilated vessels in the papillary dermis along with acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and irregular papillomatosis, as seen in angiokeratoma.4 However, the vascular proliferation composed of variably sized, thin-walled capillaries extends into the deep dermis as well as the subcutis (Figure 1). Verrucous hemangioma most commonly is reported on the legs and generally starts as a violaceous patch that progresses into a hyperkeratotic verrucous plaque or nodule.5,6

Angiokeratoma is characterized by superficial vascular ectasia of the papillary dermis in association with overlying acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and rete elongation.7 The dilated vascular spaces appear encircled by the epidermis (Figure 2). Intravascular thrombosis can be seen within the ectatic vessels.7 In contrast to verrucous hemangioma, angiokeratoma is limited to the papillary dermis. Therefore, obtaining a biopsy of sufficient depth is necessary for differentiation.8 There are 5 clinical presentations of angiokeratoma: sporadic, angiokeratoma of Mibelli, angiokeratoma of Fordyce, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, and angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (Fabry disease). Angiokeratomas may present on the lower extremities, tongue, trunk, and scrotum as hyperkeratotic, dark red to purple or black papules.7

There are 3 clinical stages of Kaposi sarcoma: patch, plaque, and nodular stages. The patch stage is characterized histologically by vascular channels that dissect through the dermis and extend around native vessels (the promontory sign)(Figure 3).9,10 These features can show histologic overlap with THH. The plaque stage shows a more diffuse dermal vascular proliferation, increased cellularity of spindle cells, and possible extension into the subcutis.9,10 Focal plasma cells, hemosiderin, and extravasated red blood cells can be seen. The nodular stage is characterized by a proliferation of spindle cells with red blood cells squeezed between slitlike vascular spaces, hyaline globules, and scattered mitotic figures, but not atypical forms.10 In this stage, plasma cells and hemosiderin are more readily identifiable. A biopsy from the nodular stage is unlikely to enter the histologic differential diagnosis with THH. Clinically, there are 4 variants of Kaposi sarcoma: the classic or sporadic form, an endemic form, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated. Overall, it is more common in males and can occur at any age.10 Human herpesvirus 8 is seen in all forms, and infected cells can be highlighted by the immunohistochemical stain for latent nuclear antigen 1.9,10

Angiosarcoma is a malignant endothelial tumor of soft tissue, skin, bone, and visceral organs.11,12 Clinically, cutaneous angiosarcoma can present in a variety of ways, including single or multiple bluish red lesions that can ulcerate or bleed; violaceous nodules or plaques; and hematomalike lesions that can mimic epithelial neoplasms including squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma.11,13,14 The cutaneous lesions most commonly occur on sun-exposed skin, particularly on the face and scalp.12 Other clinical variants that are important to recognize are postradiation angiosarcoma, characterized by MYC gene amplification, and lymphedema-associated angiosarcoma (Stewart-Treves syndrome). Angiosarcoma can have a variety of morphologic features, ranging from well to poorly differentiated. Classically, angiosarcoma is characterized by infiltrating vascular spaces lined by atypical endothelial cells (Figure 4). Poorly differentiated angiosarcoma can demonstrate spindle, epithelioid, or polygonal cells with increased mitotic activity, pleomorphism, and irregular vascular spaces.11 Endothelial markers such as ERG (erythroblast transformation specific-related gene)(nuclear) and CD31 (membranous) can be used to aid in the diagnosis of a poorly differentiated lesion. Epithelioid angiosarcoma also occasionally stains with cytokeratins.13,14

- Joyce JC, Keith PJ, Szabo S, et al. Superficial hemosiderotic lymphovascular malformation (hobnail hemangioma): a report of six cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:281-285.

- Sahin MT, Demir MA, Gunduz K, et al. Targetoid haemosiderotic haemangioma: dermoscopic monitoring of three cases and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:672-676.

- Kakizaki P, Valente NY, Paiva DL, et al. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma--case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:956-959.

- Oppermann K, Boff AL, Bonamigo RR. Verrucous hemangioma and histopathological differential diagnosis with angiokeratoma circumscriptum neviforme. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:712-715.

- Boccara, O, Ariche-Maman, S, Hadj-Rabia, S, et al. Verrucous hemangioma (also known as verrucous venous malformation): a vascular anomaly frequently misdiagnosed as a lymphatic malformation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E378-E381.

- Mestre T, Amaro C, Freitas I. Verrucous haemangioma: a diagnosis to consider [published online June 4, 2014]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-204612

- Ivy H, Julian CA. Angiokeratoma circumscriptum. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549769/

- Shetty S, Geetha V, Rao R, et al. Verrucous hemangioma: importance of a deeper biopsy. Indian J Dermatopathol Diagn Dermatol. 2014;1:99-100.

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Cancer, Kaposi sarcoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534839/

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Cao J, Wang J, He C, et al. Angiosarcoma: a review of diagnosis and current treatment. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:2303-2313.

- Papke DJ Jr, Hornick JL. What is new in endothelial neoplasia? Virchows Arch. 2020;476:17-28.

- Ambujam S, Audhya M, Reddy A, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head, neck, and face of the elderly in type 5 skin. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6:45-47.

- Shustef E, Kazlouskaya V, Prieto VG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a current update. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70:917-925.

- Joyce JC, Keith PJ, Szabo S, et al. Superficial hemosiderotic lymphovascular malformation (hobnail hemangioma): a report of six cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:281-285.

- Sahin MT, Demir MA, Gunduz K, et al. Targetoid haemosiderotic haemangioma: dermoscopic monitoring of three cases and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:672-676.

- Kakizaki P, Valente NY, Paiva DL, et al. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma--case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:956-959.

- Oppermann K, Boff AL, Bonamigo RR. Verrucous hemangioma and histopathological differential diagnosis with angiokeratoma circumscriptum neviforme. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:712-715.

- Boccara, O, Ariche-Maman, S, Hadj-Rabia, S, et al. Verrucous hemangioma (also known as verrucous venous malformation): a vascular anomaly frequently misdiagnosed as a lymphatic malformation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E378-E381.

- Mestre T, Amaro C, Freitas I. Verrucous haemangioma: a diagnosis to consider [published online June 4, 2014]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-204612

- Ivy H, Julian CA. Angiokeratoma circumscriptum. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549769/

- Shetty S, Geetha V, Rao R, et al. Verrucous hemangioma: importance of a deeper biopsy. Indian J Dermatopathol Diagn Dermatol. 2014;1:99-100.

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Cancer, Kaposi sarcoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534839/

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Cao J, Wang J, He C, et al. Angiosarcoma: a review of diagnosis and current treatment. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:2303-2313.

- Papke DJ Jr, Hornick JL. What is new in endothelial neoplasia? Virchows Arch. 2020;476:17-28.

- Ambujam S, Audhya M, Reddy A, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head, neck, and face of the elderly in type 5 skin. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6:45-47.

- Shustef E, Kazlouskaya V, Prieto VG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a current update. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70:917-925.

A 35-year-old man presented with a reddish brown papule on the left upper chest of 1 year’s duration that had changed color to reddish purple. Physical examination revealed a 6-mm violaceous papule with an erythematous rim.