User login

Subcutaneous, Mucocutaneous, and Mucous Membrane Tumors

The Diagnosis: Granular Cell Tumor

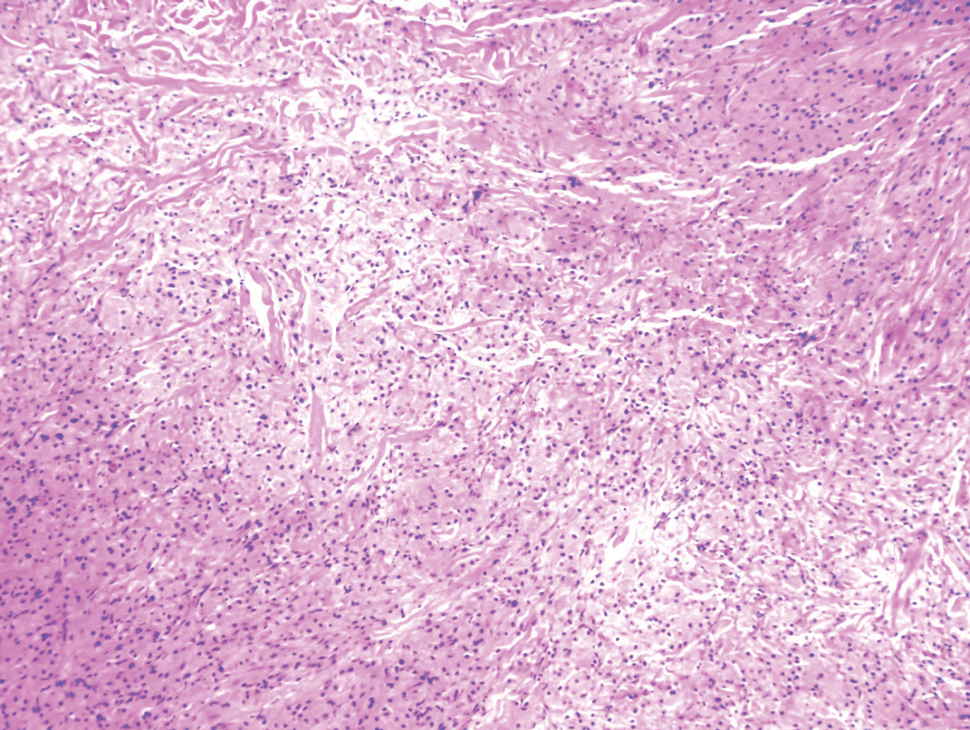

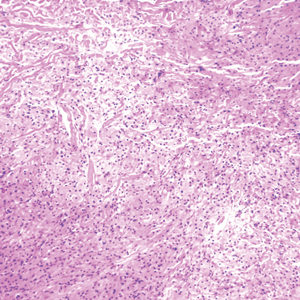

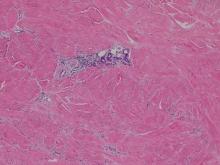

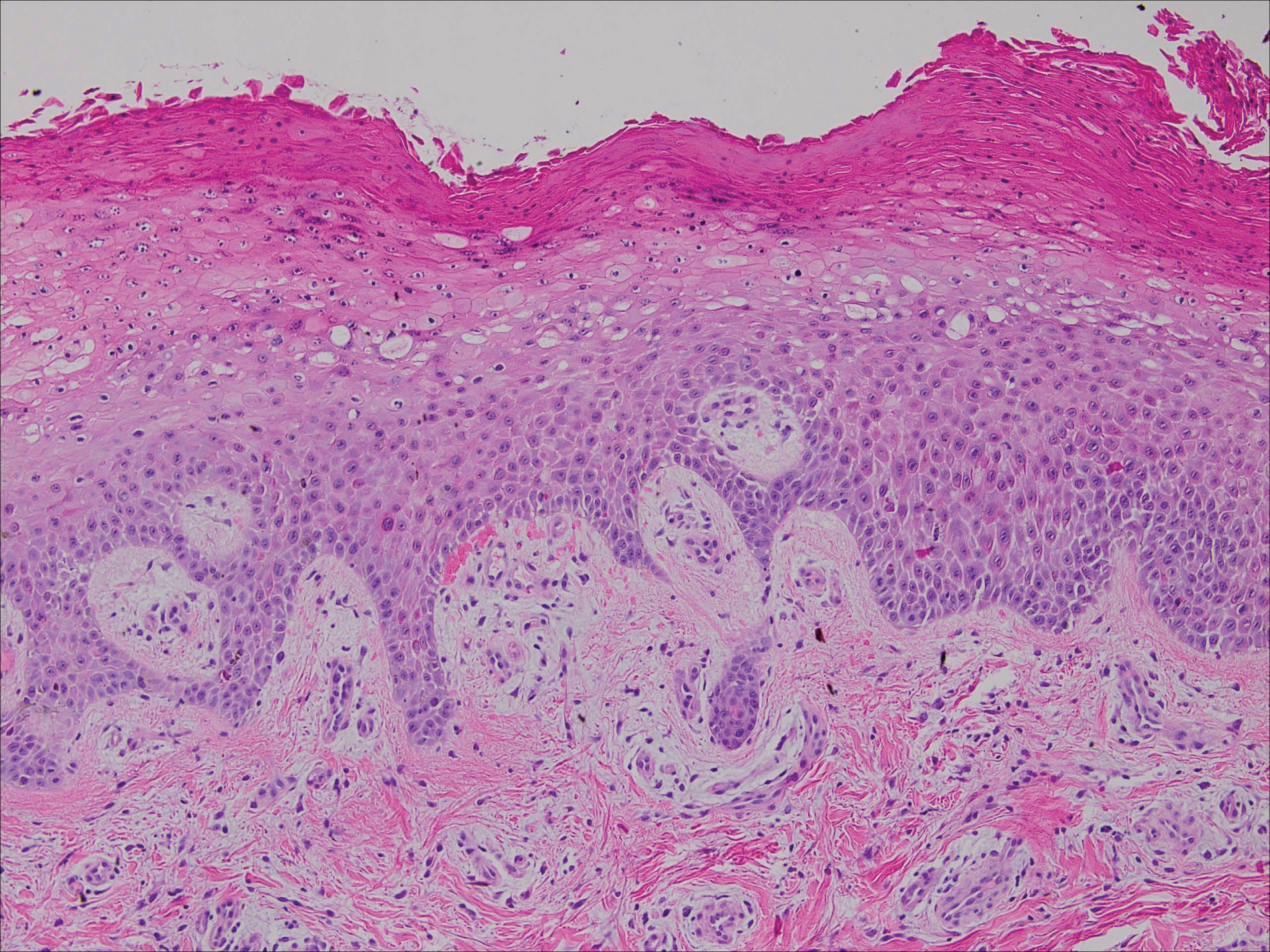

Histopathologic analysis from the axillary excision demonstrated cords and sheets of large polygonal cells in the dermis with uniform, oval, hyperchromatic nuclei and ample pink granular-staining cytoplasm (quiz images). An infiltrative growth pattern was noted; however, there was no evidence of conspicuous mitoses, nuclear pleomorphism, or necrosis. These results in conjunction with the immunohistochemistry findings were consistent with a benign granular cell tumor (GCT), a rare neoplasm considered to have neural/Schwann cell origin.1-3

Our case demonstrates the difficulty in clinically diagnosing cutaneous GCTs. The tumor often presents as a solitary, 0.5- to 3-cm, asymptomatic, firm nodule4,5; however, GCTs also can appear verrucous, eroded, or with other variable morphologies, which can create diagnostic challenges.5,6 Accordingly, a 1980 study of 110 patients with GCTs found that the preoperative clinical diagnosis was incorrect in all but 3 cases,7 emphasizing the need for histologic evaluation. Benign GCTs tend to exhibit sheets of polygonal tumor cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and small central nuclei.3,5 The cytoplasmic granules are periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant.6 Many cases feature pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, which can misleadingly resemble squamous cell carcinoma.3,5,6 Of note, invasive growth patterns on histology can occur with benign GCTs, as in our patient's case, and do not impact prognosis.3,4 On immunohistochemistry, benign, atypical, and malignant GCTs often stain positive for S-100 protein, vimentin, neuron-specific enolase, SOX10, and CD68.1,3

Although our patient's GCTs were benign, an estimated 1% to 2% are malignant.1,4 In 1998, Fanburg-Smith et al1 defined 6 histologic criteria that characterize malignant GCTs: necrosis, tumor cell spindling, vesicular nuclei with large nucleoli, high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, increased mitosis, and pleomorphism. Neoplasms with 3 or more of these features are classified as malignant, those with 1 or 2 are considered atypical, and those with only pleomorphism or no other criteria met are diagnosed as benign.1

Multiple GCTs have been reported in 10% to 25% of cases and, as highlighted in our case, can occur in both a metachronous and synchronous manner.2-4,6 Our patient developed a solitary GCT on the inferior lip 3 years prior to the appearance of 2 additional GCTs within 6 months of each other. The presence of multiple GCTs has been associated with genetic syndromes, such as neurofibromatosis type 1 and Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines3,8; however, as our case demonstrates, multiple GCTs can occur in nonsyndromic patients as well. When multiple GCTs develop at distant sites, they can resemble metastasis.3 To differentiate these clinical scenarios, Machado et al3 proposed utilizing histology and anatomic location. Multiple tumors with benign characteristics on histology likely represent multiple GCTs, whereas tumors arising at sites common to GCT metastasis, such as lymph node, bone, or viscera, are more concerning for metastatic disease. It has been suggested that patients with multiple GCTs should be monitored with physical examination and repeat magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography every 6 to 12 months.2 Given our patient's presentation with new tumors arising within 6 months of one another, we recommended a 6-month follow-up interval rather than 1 year. Due to the rarity of GCTs, clinical trials to define treatment guidelines and recommendations have not been performed.3 However, the most commonly utilized treatment modality is wide local excision, as performed in our patient.2,4

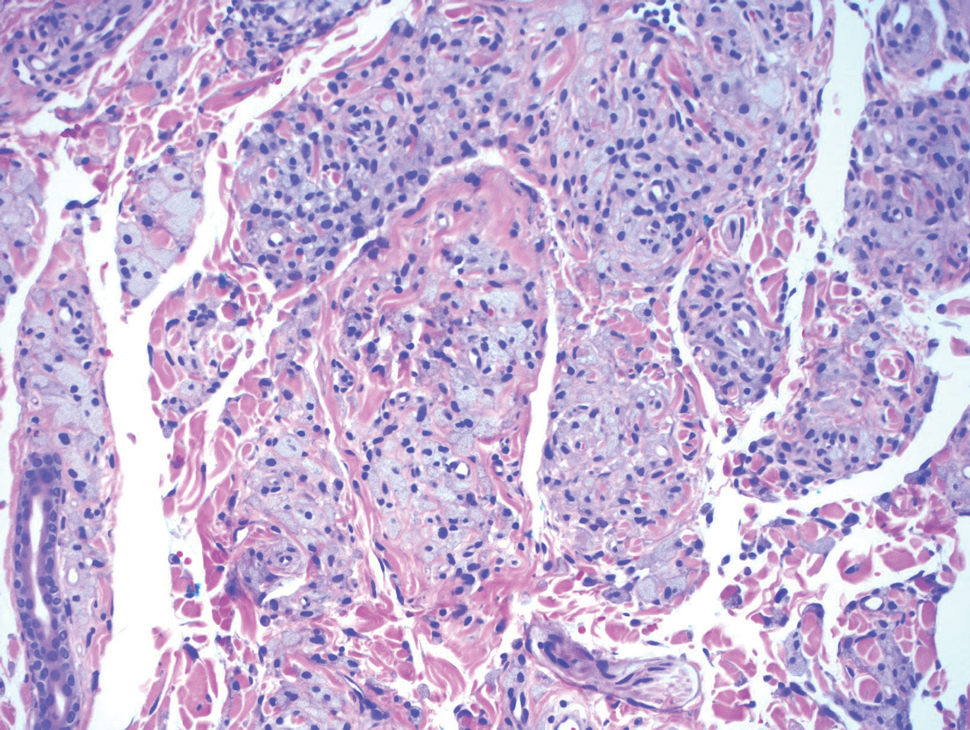

Melanoma, atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), xanthoma, and leiomyosarcoma may be difficult to distinguish from GCT.1,3,4 Melanoma incidence has increased dramatically over the last several decades, with rates in the United States rising from 6.8 cases per 100,000 individuals in the 1970s to 20.1 in the early 2000s. Risk factors for its development include UV radiation exposure and particularly severe sunburns during childhood, along with a number of host risk factors such as total number of melanocytic nevi, family history, and fair complexion.9 Histologically, it often demonstrates irregularly distributed, poorly defined melanocytes with pagetoid spread and dyscohesive nests (Figure 1).10 Melanoma metastasis occasionally can present as a soft-tissue mass and often stains positive for S-100 and vimentin, thus resembling GCT1,4; however, unlike melanoma, GCTs lack melanosomes and stain negative for more specific melanocyte markers, such as melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1).1,3,4

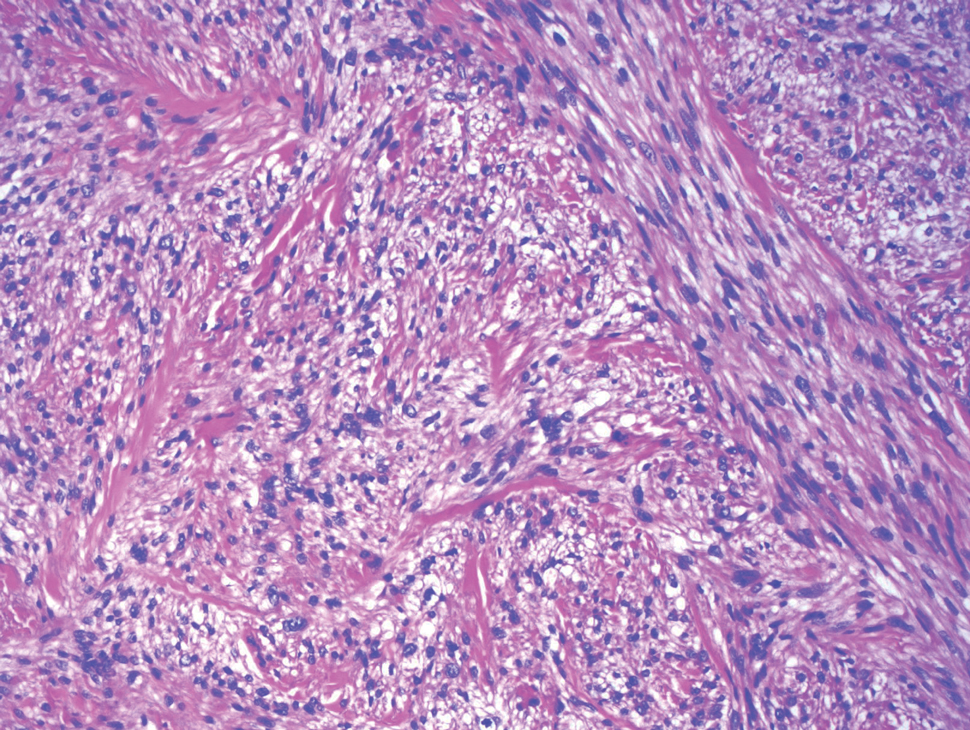

Atypical fibroxanthoma is a cutaneous neoplasm with fibrohistiocytic mesenchymal origin.11 These tumors typically arise on the head and neck in elderly individuals, particularly men with sun-damaged skin. They often present as superficial, rapidly growing nodules with the potential to ulcerate and bleed.11,12 Histologic features include pleomorphic spindle and epithelioid cells, whose nuclei appear hyperchromatic with atypical mitoses (Figure 2).12 Granular cell changes occur infrequently with AFXs, but in such cases immunohistochemistry can readily distinguish AFX from GCT. Although both tend to stain positive for CD68 and vimentin, AFXs lack S-100 protein and SOX10 expression that frequently is observed in GCTs.3,12

Xanthomas are localized lipid deposits in the connective tissue of the skin that often arise in association with dyslipidemia.13 They typically present as soft to semisolid yellow papules, plaques, or nodules. Their clinical appearance can resemble GCTs; however, histologic analysis enables differentiation with ease, as xanthomas demonstrate characteristic foam cells, consisting of lipid-laden macrophages (Figure 3).13

Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma is a rare dermal neoplasm, accounting for 2% to 3% of all sarcomas.14 They typically occur in White males during the fifth to seventh decades of life and often present as asymptomatic lesions on the lower extremities. They frequently arise from pilar smooth muscle. Unlike uterine and soft-tissue leiomyosarcoma, cutaneous leiomyosarcoma tends to follow an indolent course and rarely metastasizes.14 Histologically, these tumors display intersecting, well-defined, spindle-cell fascicles with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and cigar-shaped, blunt-ended nuclei (Figure 4).15 Occasionally, leiomyosarcomas can demonstrate cytoplasmic granularity due to lysosome accumulation4; nevertheless, the diagnosis usually can be elucidated by examining more typical histologic areas and utilizing immunohistochemistry, which often stains positive for α-smooth muscle actin, desmin, and h-caldesmon.4,15

- Fanburg-Smith JC, Meis-Kindblom JM, Fante R, et al. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:779-794.

- Moten AS, Movva S, von Mehren M, et al. Granular cell tumor experience at a comprehensive cancer center. J Surg Res. 2018;226:1-7.

- Machado I, Cruz J, Lavernia J, et al. Solitary, multiple, benign, atypical, or malignant: the "granular cell tumor" puzzle. Virchows Arch. 2016;468:527-538.

- Ordóñez NG. Granular cell tumor: a review and update. Adv Anat Pathol. 1999;6:186-203.

- Vaughan V, Ferringer T. Granular cell tumor. Cutis. 2014;94:275, 279-280.

- Van L, Parker SR. Multiple morphologically distinct cutaneous granular cell tumors occurring in a single patient. Cutis. 2016;97:E26-E29.

- Lack EE, Worsham GF, Callihan MD, et al. Granular cell tumor: a clinicopathologic study of 110 patients. J Surg Oncol. 1980;13:301-316.

- Bamps S, Oyen T, Legius E, et al. Multiple granular cell tumors in a child with Noonan syndrome. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2013;23:257-259.

- Rastrelli M, Tropea S, Rossi CR, et al. Melanoma: epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis and classification. In Vivo. 2014;28:1005-1011.

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneousmalignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(suppl 2):S34-S40.

- Soleymani T, Aasi SZ, Novoa R, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: updates on classification and management. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:253-259.

- Cardis MA, Ni J, Bhawan J. Granular cell differentiation: a review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2017;44:251-258.

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, et al. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations [published online April 29, 2014]. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158:181-188.

- Sandhu N, Sauvageau AP, Groman A, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: a SEER database analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:159-164.

- George S, Serrano C, Hensley ML, et al. Soft tissue and uterine leiomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:144-150.

The Diagnosis: Granular Cell Tumor

Histopathologic analysis from the axillary excision demonstrated cords and sheets of large polygonal cells in the dermis with uniform, oval, hyperchromatic nuclei and ample pink granular-staining cytoplasm (quiz images). An infiltrative growth pattern was noted; however, there was no evidence of conspicuous mitoses, nuclear pleomorphism, or necrosis. These results in conjunction with the immunohistochemistry findings were consistent with a benign granular cell tumor (GCT), a rare neoplasm considered to have neural/Schwann cell origin.1-3

Our case demonstrates the difficulty in clinically diagnosing cutaneous GCTs. The tumor often presents as a solitary, 0.5- to 3-cm, asymptomatic, firm nodule4,5; however, GCTs also can appear verrucous, eroded, or with other variable morphologies, which can create diagnostic challenges.5,6 Accordingly, a 1980 study of 110 patients with GCTs found that the preoperative clinical diagnosis was incorrect in all but 3 cases,7 emphasizing the need for histologic evaluation. Benign GCTs tend to exhibit sheets of polygonal tumor cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and small central nuclei.3,5 The cytoplasmic granules are periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant.6 Many cases feature pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, which can misleadingly resemble squamous cell carcinoma.3,5,6 Of note, invasive growth patterns on histology can occur with benign GCTs, as in our patient's case, and do not impact prognosis.3,4 On immunohistochemistry, benign, atypical, and malignant GCTs often stain positive for S-100 protein, vimentin, neuron-specific enolase, SOX10, and CD68.1,3

Although our patient's GCTs were benign, an estimated 1% to 2% are malignant.1,4 In 1998, Fanburg-Smith et al1 defined 6 histologic criteria that characterize malignant GCTs: necrosis, tumor cell spindling, vesicular nuclei with large nucleoli, high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, increased mitosis, and pleomorphism. Neoplasms with 3 or more of these features are classified as malignant, those with 1 or 2 are considered atypical, and those with only pleomorphism or no other criteria met are diagnosed as benign.1

Multiple GCTs have been reported in 10% to 25% of cases and, as highlighted in our case, can occur in both a metachronous and synchronous manner.2-4,6 Our patient developed a solitary GCT on the inferior lip 3 years prior to the appearance of 2 additional GCTs within 6 months of each other. The presence of multiple GCTs has been associated with genetic syndromes, such as neurofibromatosis type 1 and Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines3,8; however, as our case demonstrates, multiple GCTs can occur in nonsyndromic patients as well. When multiple GCTs develop at distant sites, they can resemble metastasis.3 To differentiate these clinical scenarios, Machado et al3 proposed utilizing histology and anatomic location. Multiple tumors with benign characteristics on histology likely represent multiple GCTs, whereas tumors arising at sites common to GCT metastasis, such as lymph node, bone, or viscera, are more concerning for metastatic disease. It has been suggested that patients with multiple GCTs should be monitored with physical examination and repeat magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography every 6 to 12 months.2 Given our patient's presentation with new tumors arising within 6 months of one another, we recommended a 6-month follow-up interval rather than 1 year. Due to the rarity of GCTs, clinical trials to define treatment guidelines and recommendations have not been performed.3 However, the most commonly utilized treatment modality is wide local excision, as performed in our patient.2,4

Melanoma, atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), xanthoma, and leiomyosarcoma may be difficult to distinguish from GCT.1,3,4 Melanoma incidence has increased dramatically over the last several decades, with rates in the United States rising from 6.8 cases per 100,000 individuals in the 1970s to 20.1 in the early 2000s. Risk factors for its development include UV radiation exposure and particularly severe sunburns during childhood, along with a number of host risk factors such as total number of melanocytic nevi, family history, and fair complexion.9 Histologically, it often demonstrates irregularly distributed, poorly defined melanocytes with pagetoid spread and dyscohesive nests (Figure 1).10 Melanoma metastasis occasionally can present as a soft-tissue mass and often stains positive for S-100 and vimentin, thus resembling GCT1,4; however, unlike melanoma, GCTs lack melanosomes and stain negative for more specific melanocyte markers, such as melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1).1,3,4

Atypical fibroxanthoma is a cutaneous neoplasm with fibrohistiocytic mesenchymal origin.11 These tumors typically arise on the head and neck in elderly individuals, particularly men with sun-damaged skin. They often present as superficial, rapidly growing nodules with the potential to ulcerate and bleed.11,12 Histologic features include pleomorphic spindle and epithelioid cells, whose nuclei appear hyperchromatic with atypical mitoses (Figure 2).12 Granular cell changes occur infrequently with AFXs, but in such cases immunohistochemistry can readily distinguish AFX from GCT. Although both tend to stain positive for CD68 and vimentin, AFXs lack S-100 protein and SOX10 expression that frequently is observed in GCTs.3,12

Xanthomas are localized lipid deposits in the connective tissue of the skin that often arise in association with dyslipidemia.13 They typically present as soft to semisolid yellow papules, plaques, or nodules. Their clinical appearance can resemble GCTs; however, histologic analysis enables differentiation with ease, as xanthomas demonstrate characteristic foam cells, consisting of lipid-laden macrophages (Figure 3).13

Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma is a rare dermal neoplasm, accounting for 2% to 3% of all sarcomas.14 They typically occur in White males during the fifth to seventh decades of life and often present as asymptomatic lesions on the lower extremities. They frequently arise from pilar smooth muscle. Unlike uterine and soft-tissue leiomyosarcoma, cutaneous leiomyosarcoma tends to follow an indolent course and rarely metastasizes.14 Histologically, these tumors display intersecting, well-defined, spindle-cell fascicles with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and cigar-shaped, blunt-ended nuclei (Figure 4).15 Occasionally, leiomyosarcomas can demonstrate cytoplasmic granularity due to lysosome accumulation4; nevertheless, the diagnosis usually can be elucidated by examining more typical histologic areas and utilizing immunohistochemistry, which often stains positive for α-smooth muscle actin, desmin, and h-caldesmon.4,15

The Diagnosis: Granular Cell Tumor

Histopathologic analysis from the axillary excision demonstrated cords and sheets of large polygonal cells in the dermis with uniform, oval, hyperchromatic nuclei and ample pink granular-staining cytoplasm (quiz images). An infiltrative growth pattern was noted; however, there was no evidence of conspicuous mitoses, nuclear pleomorphism, or necrosis. These results in conjunction with the immunohistochemistry findings were consistent with a benign granular cell tumor (GCT), a rare neoplasm considered to have neural/Schwann cell origin.1-3

Our case demonstrates the difficulty in clinically diagnosing cutaneous GCTs. The tumor often presents as a solitary, 0.5- to 3-cm, asymptomatic, firm nodule4,5; however, GCTs also can appear verrucous, eroded, or with other variable morphologies, which can create diagnostic challenges.5,6 Accordingly, a 1980 study of 110 patients with GCTs found that the preoperative clinical diagnosis was incorrect in all but 3 cases,7 emphasizing the need for histologic evaluation. Benign GCTs tend to exhibit sheets of polygonal tumor cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and small central nuclei.3,5 The cytoplasmic granules are periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant.6 Many cases feature pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, which can misleadingly resemble squamous cell carcinoma.3,5,6 Of note, invasive growth patterns on histology can occur with benign GCTs, as in our patient's case, and do not impact prognosis.3,4 On immunohistochemistry, benign, atypical, and malignant GCTs often stain positive for S-100 protein, vimentin, neuron-specific enolase, SOX10, and CD68.1,3

Although our patient's GCTs were benign, an estimated 1% to 2% are malignant.1,4 In 1998, Fanburg-Smith et al1 defined 6 histologic criteria that characterize malignant GCTs: necrosis, tumor cell spindling, vesicular nuclei with large nucleoli, high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, increased mitosis, and pleomorphism. Neoplasms with 3 or more of these features are classified as malignant, those with 1 or 2 are considered atypical, and those with only pleomorphism or no other criteria met are diagnosed as benign.1

Multiple GCTs have been reported in 10% to 25% of cases and, as highlighted in our case, can occur in both a metachronous and synchronous manner.2-4,6 Our patient developed a solitary GCT on the inferior lip 3 years prior to the appearance of 2 additional GCTs within 6 months of each other. The presence of multiple GCTs has been associated with genetic syndromes, such as neurofibromatosis type 1 and Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines3,8; however, as our case demonstrates, multiple GCTs can occur in nonsyndromic patients as well. When multiple GCTs develop at distant sites, they can resemble metastasis.3 To differentiate these clinical scenarios, Machado et al3 proposed utilizing histology and anatomic location. Multiple tumors with benign characteristics on histology likely represent multiple GCTs, whereas tumors arising at sites common to GCT metastasis, such as lymph node, bone, or viscera, are more concerning for metastatic disease. It has been suggested that patients with multiple GCTs should be monitored with physical examination and repeat magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography every 6 to 12 months.2 Given our patient's presentation with new tumors arising within 6 months of one another, we recommended a 6-month follow-up interval rather than 1 year. Due to the rarity of GCTs, clinical trials to define treatment guidelines and recommendations have not been performed.3 However, the most commonly utilized treatment modality is wide local excision, as performed in our patient.2,4

Melanoma, atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), xanthoma, and leiomyosarcoma may be difficult to distinguish from GCT.1,3,4 Melanoma incidence has increased dramatically over the last several decades, with rates in the United States rising from 6.8 cases per 100,000 individuals in the 1970s to 20.1 in the early 2000s. Risk factors for its development include UV radiation exposure and particularly severe sunburns during childhood, along with a number of host risk factors such as total number of melanocytic nevi, family history, and fair complexion.9 Histologically, it often demonstrates irregularly distributed, poorly defined melanocytes with pagetoid spread and dyscohesive nests (Figure 1).10 Melanoma metastasis occasionally can present as a soft-tissue mass and often stains positive for S-100 and vimentin, thus resembling GCT1,4; however, unlike melanoma, GCTs lack melanosomes and stain negative for more specific melanocyte markers, such as melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1).1,3,4

Atypical fibroxanthoma is a cutaneous neoplasm with fibrohistiocytic mesenchymal origin.11 These tumors typically arise on the head and neck in elderly individuals, particularly men with sun-damaged skin. They often present as superficial, rapidly growing nodules with the potential to ulcerate and bleed.11,12 Histologic features include pleomorphic spindle and epithelioid cells, whose nuclei appear hyperchromatic with atypical mitoses (Figure 2).12 Granular cell changes occur infrequently with AFXs, but in such cases immunohistochemistry can readily distinguish AFX from GCT. Although both tend to stain positive for CD68 and vimentin, AFXs lack S-100 protein and SOX10 expression that frequently is observed in GCTs.3,12

Xanthomas are localized lipid deposits in the connective tissue of the skin that often arise in association with dyslipidemia.13 They typically present as soft to semisolid yellow papules, plaques, or nodules. Their clinical appearance can resemble GCTs; however, histologic analysis enables differentiation with ease, as xanthomas demonstrate characteristic foam cells, consisting of lipid-laden macrophages (Figure 3).13

Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma is a rare dermal neoplasm, accounting for 2% to 3% of all sarcomas.14 They typically occur in White males during the fifth to seventh decades of life and often present as asymptomatic lesions on the lower extremities. They frequently arise from pilar smooth muscle. Unlike uterine and soft-tissue leiomyosarcoma, cutaneous leiomyosarcoma tends to follow an indolent course and rarely metastasizes.14 Histologically, these tumors display intersecting, well-defined, spindle-cell fascicles with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and cigar-shaped, blunt-ended nuclei (Figure 4).15 Occasionally, leiomyosarcomas can demonstrate cytoplasmic granularity due to lysosome accumulation4; nevertheless, the diagnosis usually can be elucidated by examining more typical histologic areas and utilizing immunohistochemistry, which often stains positive for α-smooth muscle actin, desmin, and h-caldesmon.4,15

- Fanburg-Smith JC, Meis-Kindblom JM, Fante R, et al. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:779-794.

- Moten AS, Movva S, von Mehren M, et al. Granular cell tumor experience at a comprehensive cancer center. J Surg Res. 2018;226:1-7.

- Machado I, Cruz J, Lavernia J, et al. Solitary, multiple, benign, atypical, or malignant: the "granular cell tumor" puzzle. Virchows Arch. 2016;468:527-538.

- Ordóñez NG. Granular cell tumor: a review and update. Adv Anat Pathol. 1999;6:186-203.

- Vaughan V, Ferringer T. Granular cell tumor. Cutis. 2014;94:275, 279-280.

- Van L, Parker SR. Multiple morphologically distinct cutaneous granular cell tumors occurring in a single patient. Cutis. 2016;97:E26-E29.

- Lack EE, Worsham GF, Callihan MD, et al. Granular cell tumor: a clinicopathologic study of 110 patients. J Surg Oncol. 1980;13:301-316.

- Bamps S, Oyen T, Legius E, et al. Multiple granular cell tumors in a child with Noonan syndrome. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2013;23:257-259.

- Rastrelli M, Tropea S, Rossi CR, et al. Melanoma: epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis and classification. In Vivo. 2014;28:1005-1011.

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneousmalignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(suppl 2):S34-S40.

- Soleymani T, Aasi SZ, Novoa R, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: updates on classification and management. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:253-259.

- Cardis MA, Ni J, Bhawan J. Granular cell differentiation: a review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2017;44:251-258.

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, et al. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations [published online April 29, 2014]. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158:181-188.

- Sandhu N, Sauvageau AP, Groman A, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: a SEER database analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:159-164.

- George S, Serrano C, Hensley ML, et al. Soft tissue and uterine leiomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:144-150.

- Fanburg-Smith JC, Meis-Kindblom JM, Fante R, et al. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:779-794.

- Moten AS, Movva S, von Mehren M, et al. Granular cell tumor experience at a comprehensive cancer center. J Surg Res. 2018;226:1-7.

- Machado I, Cruz J, Lavernia J, et al. Solitary, multiple, benign, atypical, or malignant: the "granular cell tumor" puzzle. Virchows Arch. 2016;468:527-538.

- Ordóñez NG. Granular cell tumor: a review and update. Adv Anat Pathol. 1999;6:186-203.

- Vaughan V, Ferringer T. Granular cell tumor. Cutis. 2014;94:275, 279-280.

- Van L, Parker SR. Multiple morphologically distinct cutaneous granular cell tumors occurring in a single patient. Cutis. 2016;97:E26-E29.

- Lack EE, Worsham GF, Callihan MD, et al. Granular cell tumor: a clinicopathologic study of 110 patients. J Surg Oncol. 1980;13:301-316.

- Bamps S, Oyen T, Legius E, et al. Multiple granular cell tumors in a child with Noonan syndrome. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2013;23:257-259.

- Rastrelli M, Tropea S, Rossi CR, et al. Melanoma: epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis and classification. In Vivo. 2014;28:1005-1011.

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneousmalignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(suppl 2):S34-S40.

- Soleymani T, Aasi SZ, Novoa R, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: updates on classification and management. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:253-259.

- Cardis MA, Ni J, Bhawan J. Granular cell differentiation: a review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2017;44:251-258.

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, et al. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations [published online April 29, 2014]. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158:181-188.

- Sandhu N, Sauvageau AP, Groman A, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: a SEER database analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:159-164.

- George S, Serrano C, Hensley ML, et al. Soft tissue and uterine leiomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:144-150.

A 26-year-old woman with a history of dysplastic nevi with severe atypia presented with a growth on the lower lip of 3 years’ duration. She denied any inciting event, such as prior trauma to the area, and reported that the lesion had been asymptomatic without a notable change in size. Physical examination revealed a translucent, soft, compressible cystic papule on the left inferior vermilion lip. Wide local excision following incisional biopsy was performed. Six months later, the patient returned to our clinic with a lesion on the right lateral tongue of 6 weeks’ duration as well as a 1-cm subcutaneous cyst in the left axilla of 6 months’ duration. Excisional biopsies of both lesions were performed for histopathologic analysis. Pathology results were similar among the lip, tongue, and axillary lesions. Immunohistochemistry revealed strong positive staining with antibodies to S-100 protein, SOX10, and CD68.

Acrodermatitis Enteropathica in a Patient With Short Bowel Syndrome

To the Editor:

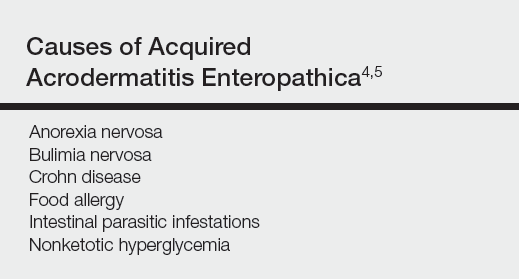

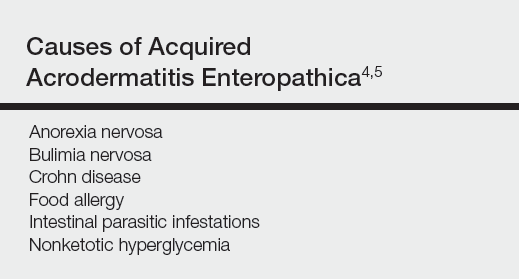

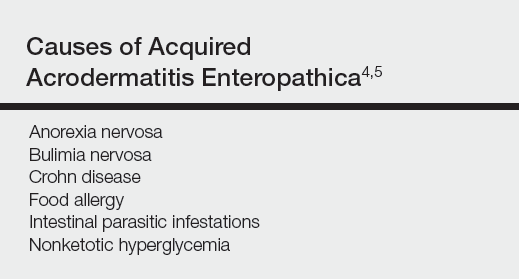

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is an inherited defect in zinc absorption that leads to hypozincemia. Its clinical presentation can vary based on serum zinc level and ranges from periorificial erosive dermatitis to psoriasiform dermatitis.1 Recognition of the cutaneous manifestations of zinc deficiency can lead to early intervention with zinc supplementation and prevention of long-term morbidity and even mortality. In our case, the coexistence of a bullous acral dermatosis with the additional feature of extensor digital dermatitis with fissuring suggests a diagnosis of AE and can alert the astute clinician to the need for testing of serum zinc levels and/or treatment with zinc supplementation. Causes of acquired zinc deficiency that have been reported in the literature include eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, Crohn disease, food allergy, intestinal parasitic infestations, and an inborn error of metabolism known as nonketotic hyperglycemia (Table).2-4

RELATED ARTICLE: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica Secondary to Alcoholism

A 42-year-old woman with a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and short bowel syndrome due to multiple small bowel obstructions with subsequent bowel resections who was on chronic total parenteral nutrition (TPN) presented with bullae on the hands, shins, and feet. The patient initially noticed small erythematous macules on the hands and feet months prior to presentation. Three weeks prior to presentation, bullae started to form on the hands, mostly between the web spaces; dorsal aspects of the feet; and anterior aspects of the shins. The patient denied any oral ulcers. One day prior to presentation the patient was seen at an outside hospital and was started on prednisone 5 mg daily, oral clindamycin, mupirocin ointment, and nystatin-triamcinolone cream. These medications failed to improve her condition. On review of systems, the patient denied any fever, chills, eye pain, or dysuria.

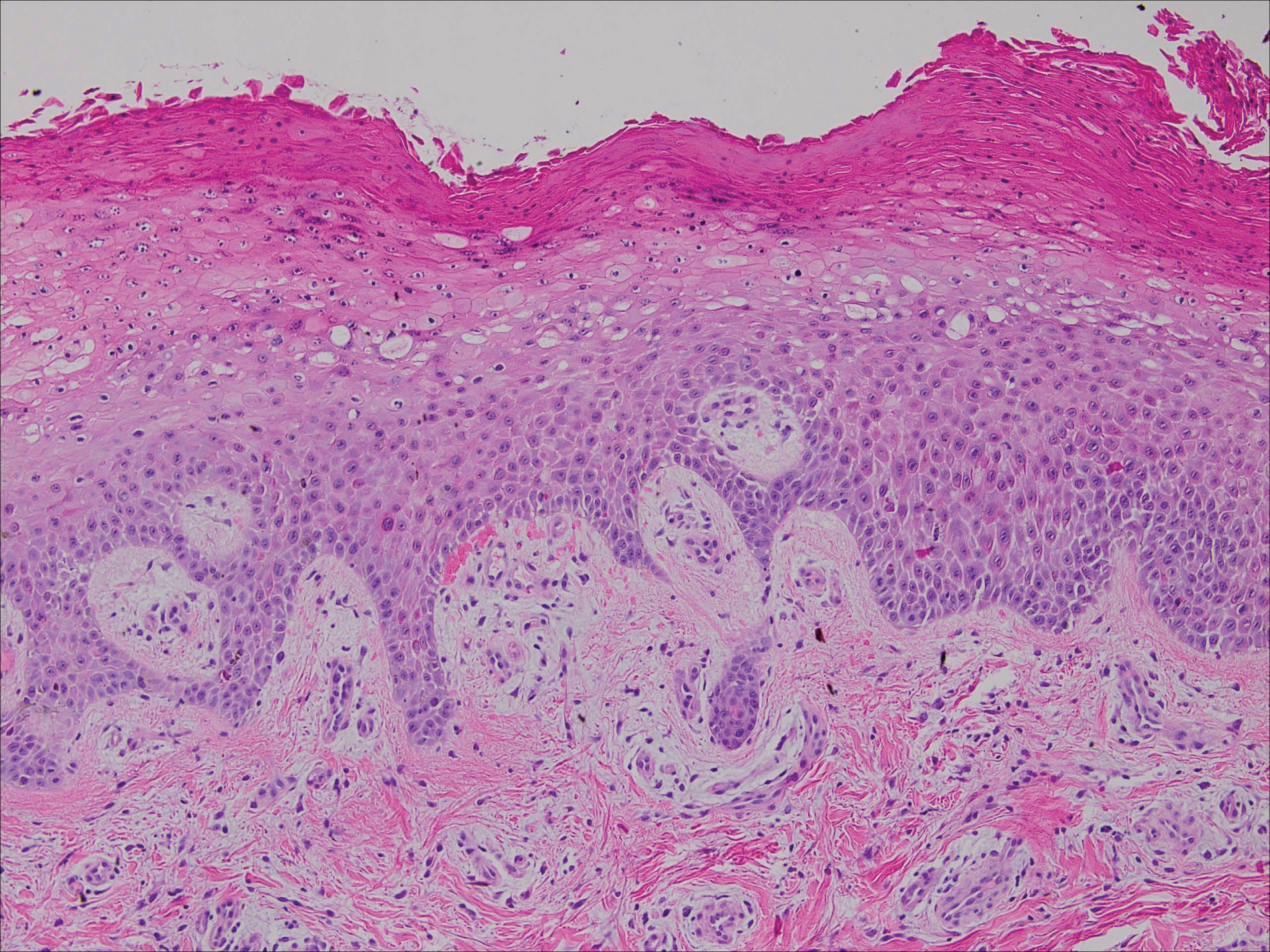

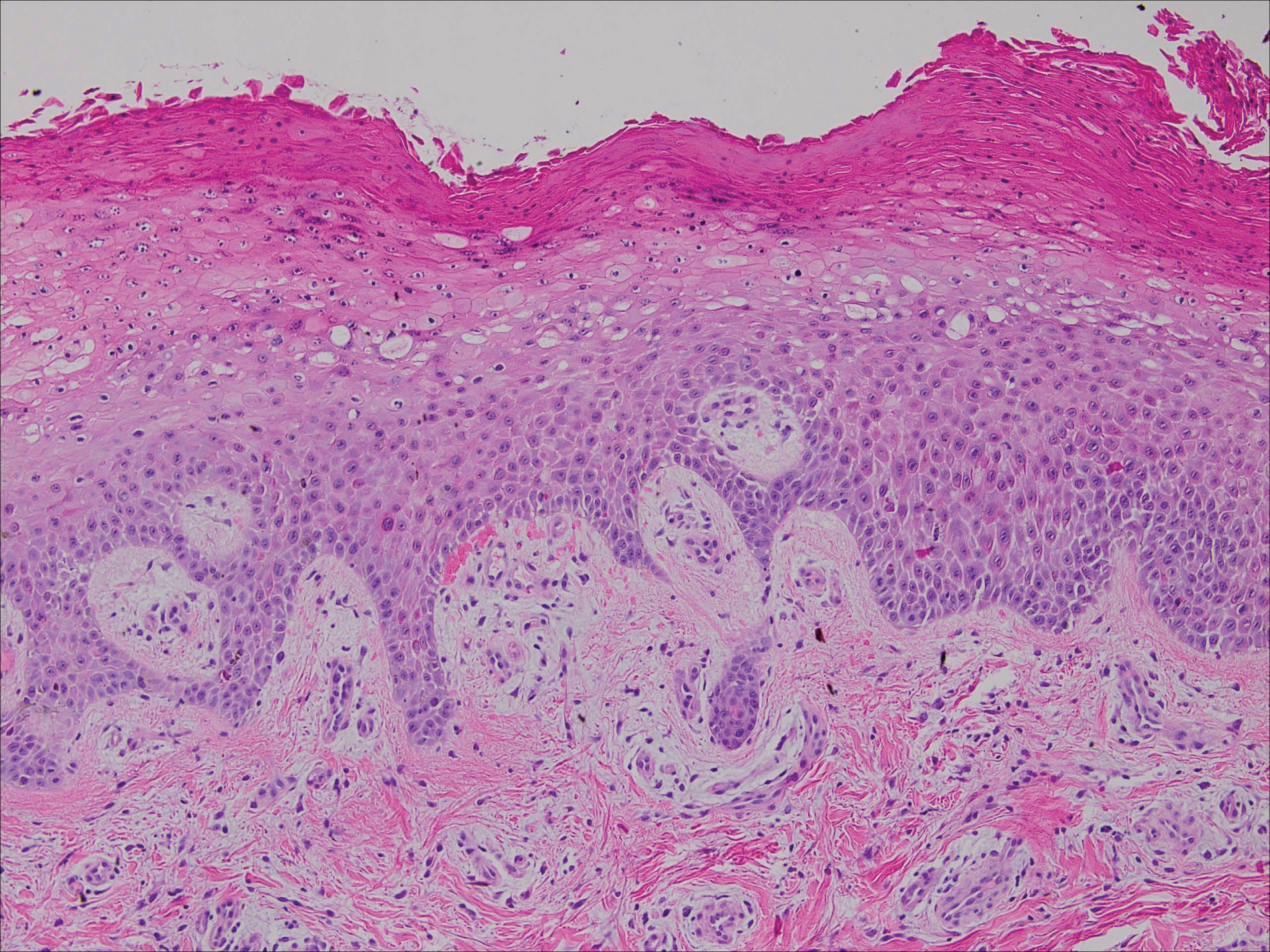

Upon initial presentation the patient appeared weak and fatigued, though vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed multiple flaccid bullae in the web spaces of the hands and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts on the bilateral wrists. She also had violaceous patches in the extensor creases of the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints, which were strikingly symmetric (Figure 1). Prominent flaccid bullae and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts also were present on the bilateral shins and dorsal aspects of the feet (Figure 2). No oral ulcers were present. A punch biopsy from the dorsal aspect of the left foot revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with prominent ballooning degeneration and hyperkeratosis/parakeratosis (Figure 3); a periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms.

Given the biopsy results and clinical presentation, a nutritional deficiency was suspected and serum levels of zinc, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, and vitamin B3 were assessed. Vitamins B1, B2

Zinc is an essential trace element and can be found in high concentration in foods such as shellfish, green vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains.6 The majority of zinc is absorbed in the jejunum; as such, many cases of acquired zinc deficiency leading to AE are dueto disorders that affect the small intestine.2 Conditions that may lead to poor gastrointestinal zinc absorption include alcoholism, eating disorders, TPN, burns, surgery, and malignancies.2,7

Diagnosis typically is made based on characteristic clinical features, biopsy results, and a measurement of the serum zinc concentration. Although a low serum zinc level supports the diagnosis, serum zinc concentration is not a reliable indicator of body zinc stores and a normal serum zinc concentration does not rule out AE. The gold standard for diagnosis is the resolution of lesions after zinc supplementation.1 Notably, because the production of alkaline phosphatase is dependent on zinc, levels of this enzyme also may be low in cases of AE,6 as in our patient.

The clinical manifestations of AE can vary greatly; patients may initially present with eczematous pink scaly plaques, which may subsequently become vesicular, bullous, pustular, or desquamative. The lesions may develop over the arms and legs as well as the anogenital and periorificial areas.5 Other notable manifestations that may present early in the course of AE include angular cheilitis followed by paronychia. In patients who are not promptly treated, long-term zinc deficiency may lead to growth delay, mental slowing, poor wound healing, anemia, and anorexia.5 Of note, deficiencies of branched-chain amino acids and essential fatty acids may appear clinically similar to AE.2

Zinc replacement is the treatment of choice for patients with AE due to dietary deficiency, and replacement therapy should begin with 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily of elemental zinc.5 Response to acquired AE with zinc supplementation often is rapid. Lesions tend to resolve within days to weeks depending on the degree of deficiency.2

Although AE is an uncommon dermatosis in the United States, it is an important diagnosis to make because its clinical features are fairly specific and early zinc supplementation allows for full resolution of the disease without permanent sequelae. The diagnosis of AE should be strongly considered when features of an acral bullous dermatosis are combined with a fissured dermatitis of extensor joints of the hands or elbows. It is particularly important to recognize that alcoholics, burn victims, postsurgical patients, and those with malignancies and eating disorders are at an increased risk for developing this nutritional deficiency.

- Kumar P, Lal NR, Mondal AK, et al. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Suchithra N, Sreejith P, Pappachan JM, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like skin eruption in a case of short bowel syndrome following jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:20.

- Sundaram A, Koutkia P, Apovian CM. Nutritional management of short bowel syndrome in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:207-220.

- Griffin IJ, Kim SC, Hicks PD, et al. Zinc metabolism in adolescents with Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:235-239.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism [published online October 30, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Cheshire H, Stather P, Vorster J. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica due to zinc deficiency in a patient with pre-existing Darier’s disease. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2009;3:41-43.

- Strumia R. Dermatologic signs in patients with eating disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:165-173.

To the Editor:

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is an inherited defect in zinc absorption that leads to hypozincemia. Its clinical presentation can vary based on serum zinc level and ranges from periorificial erosive dermatitis to psoriasiform dermatitis.1 Recognition of the cutaneous manifestations of zinc deficiency can lead to early intervention with zinc supplementation and prevention of long-term morbidity and even mortality. In our case, the coexistence of a bullous acral dermatosis with the additional feature of extensor digital dermatitis with fissuring suggests a diagnosis of AE and can alert the astute clinician to the need for testing of serum zinc levels and/or treatment with zinc supplementation. Causes of acquired zinc deficiency that have been reported in the literature include eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, Crohn disease, food allergy, intestinal parasitic infestations, and an inborn error of metabolism known as nonketotic hyperglycemia (Table).2-4

RELATED ARTICLE: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica Secondary to Alcoholism

A 42-year-old woman with a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and short bowel syndrome due to multiple small bowel obstructions with subsequent bowel resections who was on chronic total parenteral nutrition (TPN) presented with bullae on the hands, shins, and feet. The patient initially noticed small erythematous macules on the hands and feet months prior to presentation. Three weeks prior to presentation, bullae started to form on the hands, mostly between the web spaces; dorsal aspects of the feet; and anterior aspects of the shins. The patient denied any oral ulcers. One day prior to presentation the patient was seen at an outside hospital and was started on prednisone 5 mg daily, oral clindamycin, mupirocin ointment, and nystatin-triamcinolone cream. These medications failed to improve her condition. On review of systems, the patient denied any fever, chills, eye pain, or dysuria.

Upon initial presentation the patient appeared weak and fatigued, though vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed multiple flaccid bullae in the web spaces of the hands and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts on the bilateral wrists. She also had violaceous patches in the extensor creases of the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints, which were strikingly symmetric (Figure 1). Prominent flaccid bullae and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts also were present on the bilateral shins and dorsal aspects of the feet (Figure 2). No oral ulcers were present. A punch biopsy from the dorsal aspect of the left foot revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with prominent ballooning degeneration and hyperkeratosis/parakeratosis (Figure 3); a periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms.

Given the biopsy results and clinical presentation, a nutritional deficiency was suspected and serum levels of zinc, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, and vitamin B3 were assessed. Vitamins B1, B2

Zinc is an essential trace element and can be found in high concentration in foods such as shellfish, green vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains.6 The majority of zinc is absorbed in the jejunum; as such, many cases of acquired zinc deficiency leading to AE are dueto disorders that affect the small intestine.2 Conditions that may lead to poor gastrointestinal zinc absorption include alcoholism, eating disorders, TPN, burns, surgery, and malignancies.2,7

Diagnosis typically is made based on characteristic clinical features, biopsy results, and a measurement of the serum zinc concentration. Although a low serum zinc level supports the diagnosis, serum zinc concentration is not a reliable indicator of body zinc stores and a normal serum zinc concentration does not rule out AE. The gold standard for diagnosis is the resolution of lesions after zinc supplementation.1 Notably, because the production of alkaline phosphatase is dependent on zinc, levels of this enzyme also may be low in cases of AE,6 as in our patient.

The clinical manifestations of AE can vary greatly; patients may initially present with eczematous pink scaly plaques, which may subsequently become vesicular, bullous, pustular, or desquamative. The lesions may develop over the arms and legs as well as the anogenital and periorificial areas.5 Other notable manifestations that may present early in the course of AE include angular cheilitis followed by paronychia. In patients who are not promptly treated, long-term zinc deficiency may lead to growth delay, mental slowing, poor wound healing, anemia, and anorexia.5 Of note, deficiencies of branched-chain amino acids and essential fatty acids may appear clinically similar to AE.2

Zinc replacement is the treatment of choice for patients with AE due to dietary deficiency, and replacement therapy should begin with 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily of elemental zinc.5 Response to acquired AE with zinc supplementation often is rapid. Lesions tend to resolve within days to weeks depending on the degree of deficiency.2

Although AE is an uncommon dermatosis in the United States, it is an important diagnosis to make because its clinical features are fairly specific and early zinc supplementation allows for full resolution of the disease without permanent sequelae. The diagnosis of AE should be strongly considered when features of an acral bullous dermatosis are combined with a fissured dermatitis of extensor joints of the hands or elbows. It is particularly important to recognize that alcoholics, burn victims, postsurgical patients, and those with malignancies and eating disorders are at an increased risk for developing this nutritional deficiency.

To the Editor:

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is an inherited defect in zinc absorption that leads to hypozincemia. Its clinical presentation can vary based on serum zinc level and ranges from periorificial erosive dermatitis to psoriasiform dermatitis.1 Recognition of the cutaneous manifestations of zinc deficiency can lead to early intervention with zinc supplementation and prevention of long-term morbidity and even mortality. In our case, the coexistence of a bullous acral dermatosis with the additional feature of extensor digital dermatitis with fissuring suggests a diagnosis of AE and can alert the astute clinician to the need for testing of serum zinc levels and/or treatment with zinc supplementation. Causes of acquired zinc deficiency that have been reported in the literature include eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, Crohn disease, food allergy, intestinal parasitic infestations, and an inborn error of metabolism known as nonketotic hyperglycemia (Table).2-4

RELATED ARTICLE: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica Secondary to Alcoholism

A 42-year-old woman with a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and short bowel syndrome due to multiple small bowel obstructions with subsequent bowel resections who was on chronic total parenteral nutrition (TPN) presented with bullae on the hands, shins, and feet. The patient initially noticed small erythematous macules on the hands and feet months prior to presentation. Three weeks prior to presentation, bullae started to form on the hands, mostly between the web spaces; dorsal aspects of the feet; and anterior aspects of the shins. The patient denied any oral ulcers. One day prior to presentation the patient was seen at an outside hospital and was started on prednisone 5 mg daily, oral clindamycin, mupirocin ointment, and nystatin-triamcinolone cream. These medications failed to improve her condition. On review of systems, the patient denied any fever, chills, eye pain, or dysuria.

Upon initial presentation the patient appeared weak and fatigued, though vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed multiple flaccid bullae in the web spaces of the hands and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts on the bilateral wrists. She also had violaceous patches in the extensor creases of the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints, which were strikingly symmetric (Figure 1). Prominent flaccid bullae and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts also were present on the bilateral shins and dorsal aspects of the feet (Figure 2). No oral ulcers were present. A punch biopsy from the dorsal aspect of the left foot revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with prominent ballooning degeneration and hyperkeratosis/parakeratosis (Figure 3); a periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms.

Given the biopsy results and clinical presentation, a nutritional deficiency was suspected and serum levels of zinc, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, and vitamin B3 were assessed. Vitamins B1, B2

Zinc is an essential trace element and can be found in high concentration in foods such as shellfish, green vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains.6 The majority of zinc is absorbed in the jejunum; as such, many cases of acquired zinc deficiency leading to AE are dueto disorders that affect the small intestine.2 Conditions that may lead to poor gastrointestinal zinc absorption include alcoholism, eating disorders, TPN, burns, surgery, and malignancies.2,7

Diagnosis typically is made based on characteristic clinical features, biopsy results, and a measurement of the serum zinc concentration. Although a low serum zinc level supports the diagnosis, serum zinc concentration is not a reliable indicator of body zinc stores and a normal serum zinc concentration does not rule out AE. The gold standard for diagnosis is the resolution of lesions after zinc supplementation.1 Notably, because the production of alkaline phosphatase is dependent on zinc, levels of this enzyme also may be low in cases of AE,6 as in our patient.

The clinical manifestations of AE can vary greatly; patients may initially present with eczematous pink scaly plaques, which may subsequently become vesicular, bullous, pustular, or desquamative. The lesions may develop over the arms and legs as well as the anogenital and periorificial areas.5 Other notable manifestations that may present early in the course of AE include angular cheilitis followed by paronychia. In patients who are not promptly treated, long-term zinc deficiency may lead to growth delay, mental slowing, poor wound healing, anemia, and anorexia.5 Of note, deficiencies of branched-chain amino acids and essential fatty acids may appear clinically similar to AE.2

Zinc replacement is the treatment of choice for patients with AE due to dietary deficiency, and replacement therapy should begin with 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily of elemental zinc.5 Response to acquired AE with zinc supplementation often is rapid. Lesions tend to resolve within days to weeks depending on the degree of deficiency.2

Although AE is an uncommon dermatosis in the United States, it is an important diagnosis to make because its clinical features are fairly specific and early zinc supplementation allows for full resolution of the disease without permanent sequelae. The diagnosis of AE should be strongly considered when features of an acral bullous dermatosis are combined with a fissured dermatitis of extensor joints of the hands or elbows. It is particularly important to recognize that alcoholics, burn victims, postsurgical patients, and those with malignancies and eating disorders are at an increased risk for developing this nutritional deficiency.

- Kumar P, Lal NR, Mondal AK, et al. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Suchithra N, Sreejith P, Pappachan JM, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like skin eruption in a case of short bowel syndrome following jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:20.

- Sundaram A, Koutkia P, Apovian CM. Nutritional management of short bowel syndrome in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:207-220.

- Griffin IJ, Kim SC, Hicks PD, et al. Zinc metabolism in adolescents with Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:235-239.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism [published online October 30, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Cheshire H, Stather P, Vorster J. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica due to zinc deficiency in a patient with pre-existing Darier’s disease. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2009;3:41-43.

- Strumia R. Dermatologic signs in patients with eating disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:165-173.

- Kumar P, Lal NR, Mondal AK, et al. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Suchithra N, Sreejith P, Pappachan JM, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like skin eruption in a case of short bowel syndrome following jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:20.

- Sundaram A, Koutkia P, Apovian CM. Nutritional management of short bowel syndrome in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:207-220.

- Griffin IJ, Kim SC, Hicks PD, et al. Zinc metabolism in adolescents with Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:235-239.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism [published online October 30, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Cheshire H, Stather P, Vorster J. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica due to zinc deficiency in a patient with pre-existing Darier’s disease. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2009;3:41-43.

- Strumia R. Dermatologic signs in patients with eating disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:165-173.

Practice Points

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica can be a manifestation of zinc deficiency.

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica should be considered in patients with poor intestinal absorption of nutrients.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Eosinophilic Fasciitis

|

A 43-year-old woman presented with pain and paresthesia of the bilateral legs of 3 months’ duration with skin tightness and discoloration, which she attributed to a car accident that occurred 7 months prior. She also reported abdominal pain, shortness of breath, fever, double vision, dysphagia, voice changes, temperature sensitivity, and hair loss. The patient underwent outpatient steroid injections with limited symptomatic relief. She denied any antecedent exposure to vinyl chloride, rapeseed oil, or L-tryptophan. Physical examination revealed thickened skin on the bilateral legs (top), reddish discoloration of the feet, decreased sensation to light touch, and edema of the ankles and wrists, as well as a peau d’orange appearance of the skin on the arms (bottom), legs, and abdomen.

The Diagnosis: Eosinophilic Fasciitis

Eosinophilic fasciitis is a rare autoimmune disease of uncertain etiology first described by Shulman1 in 1974. It is similar in presentation and is perhaps related to scleroderma. Classic differentiating features include a peculiar peau d’orange appearance, peripheral eosinophilia, and lack of Raynaud phenomenon, thus it is regarded as a unique disease.2 Despite the name of the disease, eosinophilia has been known to be absent in later stages of eosinophilic fasciitis.1

On physical examination, “prayer and groove signs” can sometimes be evident.3 Although it was not initially observed in our case, a groove sign was noted on the left forearm on a second inspection (Figure 1). In contrast with systemic sclerosis, visceral involvement rarely is seen with eosinophilic fasciitis. There are, however, 3 major exceptions to this rule. First, there can be widespread nerve deficits, esophageal dysmotility, and nonspecific electromyography findings (ie, denervation, reinnervation, fasciculations).4 There also can be a concomitant hematologic disorder or Hashimoto thyroiditis.5 Because eosinophilic fasciitis has been associated with monoclonal gammopathy, which our patient also demonstrated, it is important to conduct a workup with serum or urine protein electrophoresis. If the test is negative, it should be followed up with an immunofixation assay or serum light chain assays.

Some proposed risk factors for eosinophilic fasciitis include trauma, extensive exercise, and Borrelia burgdorferi infection, but many cases have none of these associations.8 Although not firmly proven in the literature, there have been reports of eosinophilic fasciitis after isolated trauma.5 A causal link could not be established between our patient’s car accident and eosinophilic fasciitis, but the coincidence was notable.

The treatment of eosinophilic fasciitis is similar to scleroderma. Corticosteroids are effective in most cases and recovery often occurs with monotherapy.5 Case series have demonstrated efficacy in adding methotrexate, azathioprine, colchicine, and hydroxychloroquine in refractory patients.2,9 Our patient demonstrated a good response with a combination of prednisone and methotrexate. Relapses have been known to occur.2

A punch biopsy obtained from the right arm showed thickened acellular collagen bundles throughout the dermis and extending into the underlying subcutis. There also was obliteration of adnexal structures, loss of perieccrine fat, and sparse perivascular and interstitial lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2), consistent with a sclerosing disorder such as scleroderma or eosinophilic fasciitis.

A complete blood cell count revealed eosinophil levels of 12.5% (reference range, 2.7%). Rheumatologic workup was negative for antinuclear antibody, double-stranded DNA, thyroid-stimulating hormone, anticentromere antibodies, and Scl-70 autoantibodies. Computed tomography of the chest and pelvis revealed a thickened patulous esophagus. Endoscopy showed dysmotility of the lower esophagus. At this point the differential diagnosis included scleredema versus eosinophilic fasciitis, and the patient was started on oral prednisone 60 mg daily. She showed rapid improvement in sclerosis, joint mobility, and ability to swallow. Magnetic resonance imaging was then performed and revealed thickening and contrast enhancement of the forearm fascia, particularly along the distal aspect, confirming a diagnosis of eosinophilic fasciitis. Further workup including immunofixation assay and serum light chain assays were performed, revealing IgG λ hypergammaglobulinemia. She was then additionally treated with oral methotrexate 15 mg weekly. Due to the rapid improvement of symptoms on oral prednisone over 2 weeks, the peripheral eosinophilia, the magnetic resonance imaging findings, and the results of skin biopsy, a diagnosis of eosinophilic fasciitis was heavily favored over scleroderma and scleredema.

1. Shulman L. Diffuse fasciitis with hypergammaglobulinemia and eosinophilia in a new syndrome. J. Rheumatol. 1974;1(suppl):46.

2. Lakhanpal S, Ginsburg WW, Michet CJ, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis: clinical spectrum and therapeutic response in 52 cases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1988;17:221-231.

3. Servy A, Clerici T, Malines C, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis: a rare skin sclerosis. Pathol Res Int. 2010;2011:716935.

4. Satsangi J, Donaghy M. Multifocal peripheral neuropathy in eosinophilic fasciitis. J Neurol. 1992;239:91-92.

5. Antic M, Lautenschlager S, Itin PH. Eosinophilic fasciitis 30 years after—what do we really know? Dermatology. 2006;213:93-101.

6. Doyle JA, Ginsburg WW. Eosinophilic fasciitis. Med Clin North Am. 1989;73:1157-1166.

7. Naschitz JE, Yeshurun D, Miselevich I, et al. Colitis and pericarditis in a patient with eosinophilic fasciitis—a contribution to the multisystem nature of eosinophilic fasciitis. J Rheumatol. 1989;16:688-692.

8. Haustein UF. Scleroderma and pseudoscleroderma: uncommon presentations. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:480-490.

9. Lebeaux D, Francès C, Barete S, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis (Shulman disease): new insights into the therapeutic management from a series of 34 patients. Rheumatology. 2012;51:557-561.

|

A 43-year-old woman presented with pain and paresthesia of the bilateral legs of 3 months’ duration with skin tightness and discoloration, which she attributed to a car accident that occurred 7 months prior. She also reported abdominal pain, shortness of breath, fever, double vision, dysphagia, voice changes, temperature sensitivity, and hair loss. The patient underwent outpatient steroid injections with limited symptomatic relief. She denied any antecedent exposure to vinyl chloride, rapeseed oil, or L-tryptophan. Physical examination revealed thickened skin on the bilateral legs (top), reddish discoloration of the feet, decreased sensation to light touch, and edema of the ankles and wrists, as well as a peau d’orange appearance of the skin on the arms (bottom), legs, and abdomen.

The Diagnosis: Eosinophilic Fasciitis

Eosinophilic fasciitis is a rare autoimmune disease of uncertain etiology first described by Shulman1 in 1974. It is similar in presentation and is perhaps related to scleroderma. Classic differentiating features include a peculiar peau d’orange appearance, peripheral eosinophilia, and lack of Raynaud phenomenon, thus it is regarded as a unique disease.2 Despite the name of the disease, eosinophilia has been known to be absent in later stages of eosinophilic fasciitis.1

On physical examination, “prayer and groove signs” can sometimes be evident.3 Although it was not initially observed in our case, a groove sign was noted on the left forearm on a second inspection (Figure 1). In contrast with systemic sclerosis, visceral involvement rarely is seen with eosinophilic fasciitis. There are, however, 3 major exceptions to this rule. First, there can be widespread nerve deficits, esophageal dysmotility, and nonspecific electromyography findings (ie, denervation, reinnervation, fasciculations).4 There also can be a concomitant hematologic disorder or Hashimoto thyroiditis.5 Because eosinophilic fasciitis has been associated with monoclonal gammopathy, which our patient also demonstrated, it is important to conduct a workup with serum or urine protein electrophoresis. If the test is negative, it should be followed up with an immunofixation assay or serum light chain assays.

Some proposed risk factors for eosinophilic fasciitis include trauma, extensive exercise, and Borrelia burgdorferi infection, but many cases have none of these associations.8 Although not firmly proven in the literature, there have been reports of eosinophilic fasciitis after isolated trauma.5 A causal link could not be established between our patient’s car accident and eosinophilic fasciitis, but the coincidence was notable.

The treatment of eosinophilic fasciitis is similar to scleroderma. Corticosteroids are effective in most cases and recovery often occurs with monotherapy.5 Case series have demonstrated efficacy in adding methotrexate, azathioprine, colchicine, and hydroxychloroquine in refractory patients.2,9 Our patient demonstrated a good response with a combination of prednisone and methotrexate. Relapses have been known to occur.2

A punch biopsy obtained from the right arm showed thickened acellular collagen bundles throughout the dermis and extending into the underlying subcutis. There also was obliteration of adnexal structures, loss of perieccrine fat, and sparse perivascular and interstitial lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2), consistent with a sclerosing disorder such as scleroderma or eosinophilic fasciitis.

A complete blood cell count revealed eosinophil levels of 12.5% (reference range, 2.7%). Rheumatologic workup was negative for antinuclear antibody, double-stranded DNA, thyroid-stimulating hormone, anticentromere antibodies, and Scl-70 autoantibodies. Computed tomography of the chest and pelvis revealed a thickened patulous esophagus. Endoscopy showed dysmotility of the lower esophagus. At this point the differential diagnosis included scleredema versus eosinophilic fasciitis, and the patient was started on oral prednisone 60 mg daily. She showed rapid improvement in sclerosis, joint mobility, and ability to swallow. Magnetic resonance imaging was then performed and revealed thickening and contrast enhancement of the forearm fascia, particularly along the distal aspect, confirming a diagnosis of eosinophilic fasciitis. Further workup including immunofixation assay and serum light chain assays were performed, revealing IgG λ hypergammaglobulinemia. She was then additionally treated with oral methotrexate 15 mg weekly. Due to the rapid improvement of symptoms on oral prednisone over 2 weeks, the peripheral eosinophilia, the magnetic resonance imaging findings, and the results of skin biopsy, a diagnosis of eosinophilic fasciitis was heavily favored over scleroderma and scleredema.

|

A 43-year-old woman presented with pain and paresthesia of the bilateral legs of 3 months’ duration with skin tightness and discoloration, which she attributed to a car accident that occurred 7 months prior. She also reported abdominal pain, shortness of breath, fever, double vision, dysphagia, voice changes, temperature sensitivity, and hair loss. The patient underwent outpatient steroid injections with limited symptomatic relief. She denied any antecedent exposure to vinyl chloride, rapeseed oil, or L-tryptophan. Physical examination revealed thickened skin on the bilateral legs (top), reddish discoloration of the feet, decreased sensation to light touch, and edema of the ankles and wrists, as well as a peau d’orange appearance of the skin on the arms (bottom), legs, and abdomen.

The Diagnosis: Eosinophilic Fasciitis

Eosinophilic fasciitis is a rare autoimmune disease of uncertain etiology first described by Shulman1 in 1974. It is similar in presentation and is perhaps related to scleroderma. Classic differentiating features include a peculiar peau d’orange appearance, peripheral eosinophilia, and lack of Raynaud phenomenon, thus it is regarded as a unique disease.2 Despite the name of the disease, eosinophilia has been known to be absent in later stages of eosinophilic fasciitis.1

On physical examination, “prayer and groove signs” can sometimes be evident.3 Although it was not initially observed in our case, a groove sign was noted on the left forearm on a second inspection (Figure 1). In contrast with systemic sclerosis, visceral involvement rarely is seen with eosinophilic fasciitis. There are, however, 3 major exceptions to this rule. First, there can be widespread nerve deficits, esophageal dysmotility, and nonspecific electromyography findings (ie, denervation, reinnervation, fasciculations).4 There also can be a concomitant hematologic disorder or Hashimoto thyroiditis.5 Because eosinophilic fasciitis has been associated with monoclonal gammopathy, which our patient also demonstrated, it is important to conduct a workup with serum or urine protein electrophoresis. If the test is negative, it should be followed up with an immunofixation assay or serum light chain assays.

Some proposed risk factors for eosinophilic fasciitis include trauma, extensive exercise, and Borrelia burgdorferi infection, but many cases have none of these associations.8 Although not firmly proven in the literature, there have been reports of eosinophilic fasciitis after isolated trauma.5 A causal link could not be established between our patient’s car accident and eosinophilic fasciitis, but the coincidence was notable.

The treatment of eosinophilic fasciitis is similar to scleroderma. Corticosteroids are effective in most cases and recovery often occurs with monotherapy.5 Case series have demonstrated efficacy in adding methotrexate, azathioprine, colchicine, and hydroxychloroquine in refractory patients.2,9 Our patient demonstrated a good response with a combination of prednisone and methotrexate. Relapses have been known to occur.2

A punch biopsy obtained from the right arm showed thickened acellular collagen bundles throughout the dermis and extending into the underlying subcutis. There also was obliteration of adnexal structures, loss of perieccrine fat, and sparse perivascular and interstitial lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2), consistent with a sclerosing disorder such as scleroderma or eosinophilic fasciitis.

A complete blood cell count revealed eosinophil levels of 12.5% (reference range, 2.7%). Rheumatologic workup was negative for antinuclear antibody, double-stranded DNA, thyroid-stimulating hormone, anticentromere antibodies, and Scl-70 autoantibodies. Computed tomography of the chest and pelvis revealed a thickened patulous esophagus. Endoscopy showed dysmotility of the lower esophagus. At this point the differential diagnosis included scleredema versus eosinophilic fasciitis, and the patient was started on oral prednisone 60 mg daily. She showed rapid improvement in sclerosis, joint mobility, and ability to swallow. Magnetic resonance imaging was then performed and revealed thickening and contrast enhancement of the forearm fascia, particularly along the distal aspect, confirming a diagnosis of eosinophilic fasciitis. Further workup including immunofixation assay and serum light chain assays were performed, revealing IgG λ hypergammaglobulinemia. She was then additionally treated with oral methotrexate 15 mg weekly. Due to the rapid improvement of symptoms on oral prednisone over 2 weeks, the peripheral eosinophilia, the magnetic resonance imaging findings, and the results of skin biopsy, a diagnosis of eosinophilic fasciitis was heavily favored over scleroderma and scleredema.

1. Shulman L. Diffuse fasciitis with hypergammaglobulinemia and eosinophilia in a new syndrome. J. Rheumatol. 1974;1(suppl):46.

2. Lakhanpal S, Ginsburg WW, Michet CJ, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis: clinical spectrum and therapeutic response in 52 cases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1988;17:221-231.

3. Servy A, Clerici T, Malines C, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis: a rare skin sclerosis. Pathol Res Int. 2010;2011:716935.

4. Satsangi J, Donaghy M. Multifocal peripheral neuropathy in eosinophilic fasciitis. J Neurol. 1992;239:91-92.

5. Antic M, Lautenschlager S, Itin PH. Eosinophilic fasciitis 30 years after—what do we really know? Dermatology. 2006;213:93-101.

6. Doyle JA, Ginsburg WW. Eosinophilic fasciitis. Med Clin North Am. 1989;73:1157-1166.

7. Naschitz JE, Yeshurun D, Miselevich I, et al. Colitis and pericarditis in a patient with eosinophilic fasciitis—a contribution to the multisystem nature of eosinophilic fasciitis. J Rheumatol. 1989;16:688-692.

8. Haustein UF. Scleroderma and pseudoscleroderma: uncommon presentations. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:480-490.

9. Lebeaux D, Francès C, Barete S, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis (Shulman disease): new insights into the therapeutic management from a series of 34 patients. Rheumatology. 2012;51:557-561.

1. Shulman L. Diffuse fasciitis with hypergammaglobulinemia and eosinophilia in a new syndrome. J. Rheumatol. 1974;1(suppl):46.

2. Lakhanpal S, Ginsburg WW, Michet CJ, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis: clinical spectrum and therapeutic response in 52 cases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1988;17:221-231.

3. Servy A, Clerici T, Malines C, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis: a rare skin sclerosis. Pathol Res Int. 2010;2011:716935.

4. Satsangi J, Donaghy M. Multifocal peripheral neuropathy in eosinophilic fasciitis. J Neurol. 1992;239:91-92.

5. Antic M, Lautenschlager S, Itin PH. Eosinophilic fasciitis 30 years after—what do we really know? Dermatology. 2006;213:93-101.

6. Doyle JA, Ginsburg WW. Eosinophilic fasciitis. Med Clin North Am. 1989;73:1157-1166.

7. Naschitz JE, Yeshurun D, Miselevich I, et al. Colitis and pericarditis in a patient with eosinophilic fasciitis—a contribution to the multisystem nature of eosinophilic fasciitis. J Rheumatol. 1989;16:688-692.

8. Haustein UF. Scleroderma and pseudoscleroderma: uncommon presentations. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:480-490.

9. Lebeaux D, Francès C, Barete S, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis (Shulman disease): new insights into the therapeutic management from a series of 34 patients. Rheumatology. 2012;51:557-561.