User login

Acrodermatitis Enteropathica in a Patient With Short Bowel Syndrome

To the Editor:

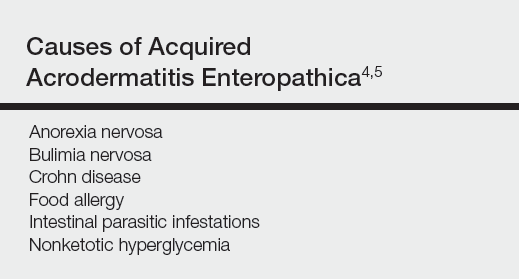

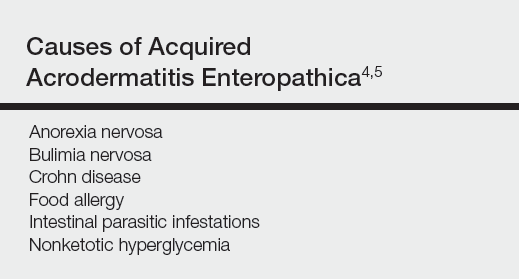

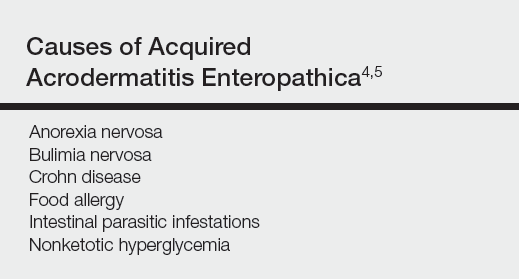

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is an inherited defect in zinc absorption that leads to hypozincemia. Its clinical presentation can vary based on serum zinc level and ranges from periorificial erosive dermatitis to psoriasiform dermatitis.1 Recognition of the cutaneous manifestations of zinc deficiency can lead to early intervention with zinc supplementation and prevention of long-term morbidity and even mortality. In our case, the coexistence of a bullous acral dermatosis with the additional feature of extensor digital dermatitis with fissuring suggests a diagnosis of AE and can alert the astute clinician to the need for testing of serum zinc levels and/or treatment with zinc supplementation. Causes of acquired zinc deficiency that have been reported in the literature include eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, Crohn disease, food allergy, intestinal parasitic infestations, and an inborn error of metabolism known as nonketotic hyperglycemia (Table).2-4

RELATED ARTICLE: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica Secondary to Alcoholism

A 42-year-old woman with a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and short bowel syndrome due to multiple small bowel obstructions with subsequent bowel resections who was on chronic total parenteral nutrition (TPN) presented with bullae on the hands, shins, and feet. The patient initially noticed small erythematous macules on the hands and feet months prior to presentation. Three weeks prior to presentation, bullae started to form on the hands, mostly between the web spaces; dorsal aspects of the feet; and anterior aspects of the shins. The patient denied any oral ulcers. One day prior to presentation the patient was seen at an outside hospital and was started on prednisone 5 mg daily, oral clindamycin, mupirocin ointment, and nystatin-triamcinolone cream. These medications failed to improve her condition. On review of systems, the patient denied any fever, chills, eye pain, or dysuria.

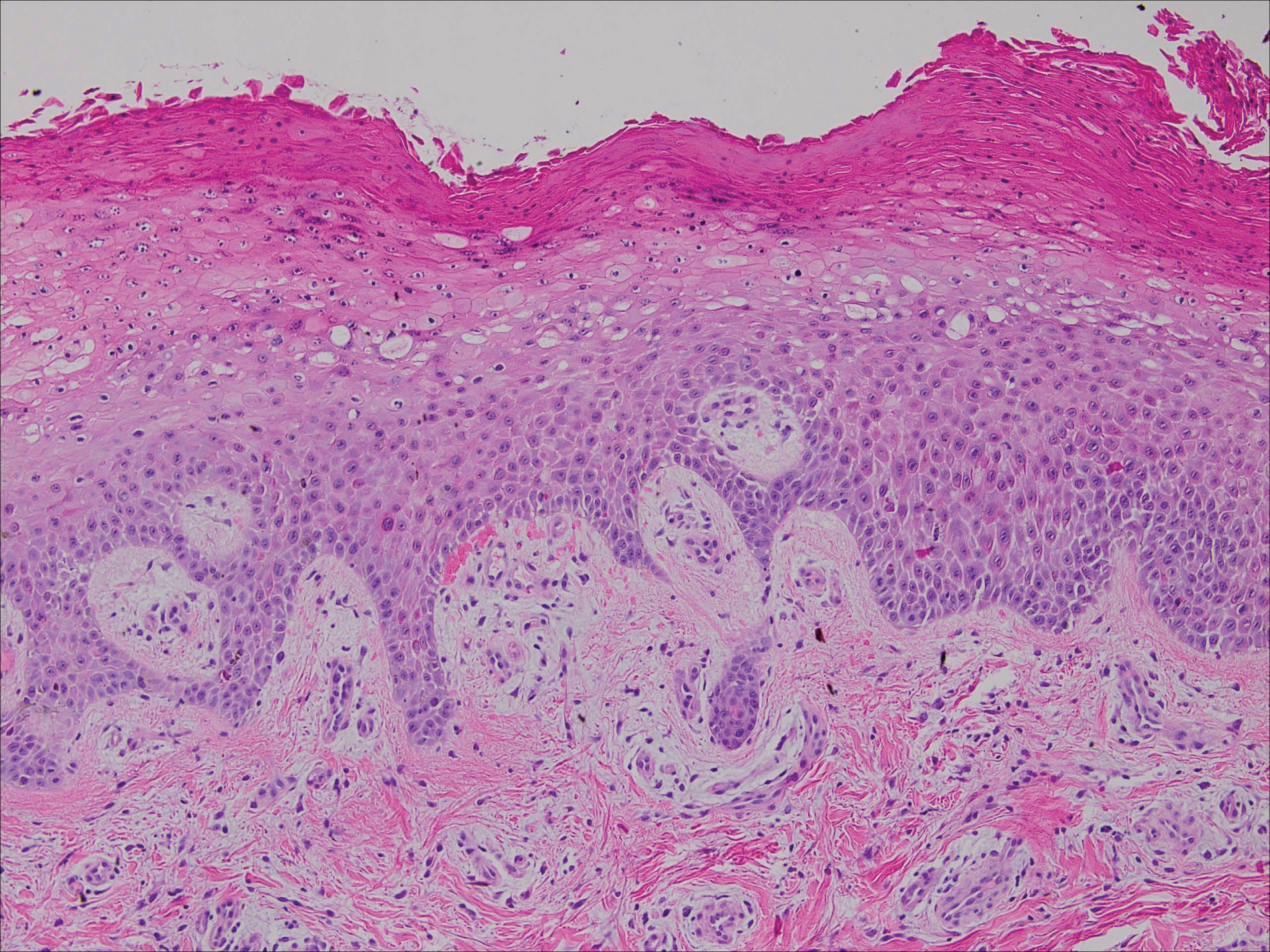

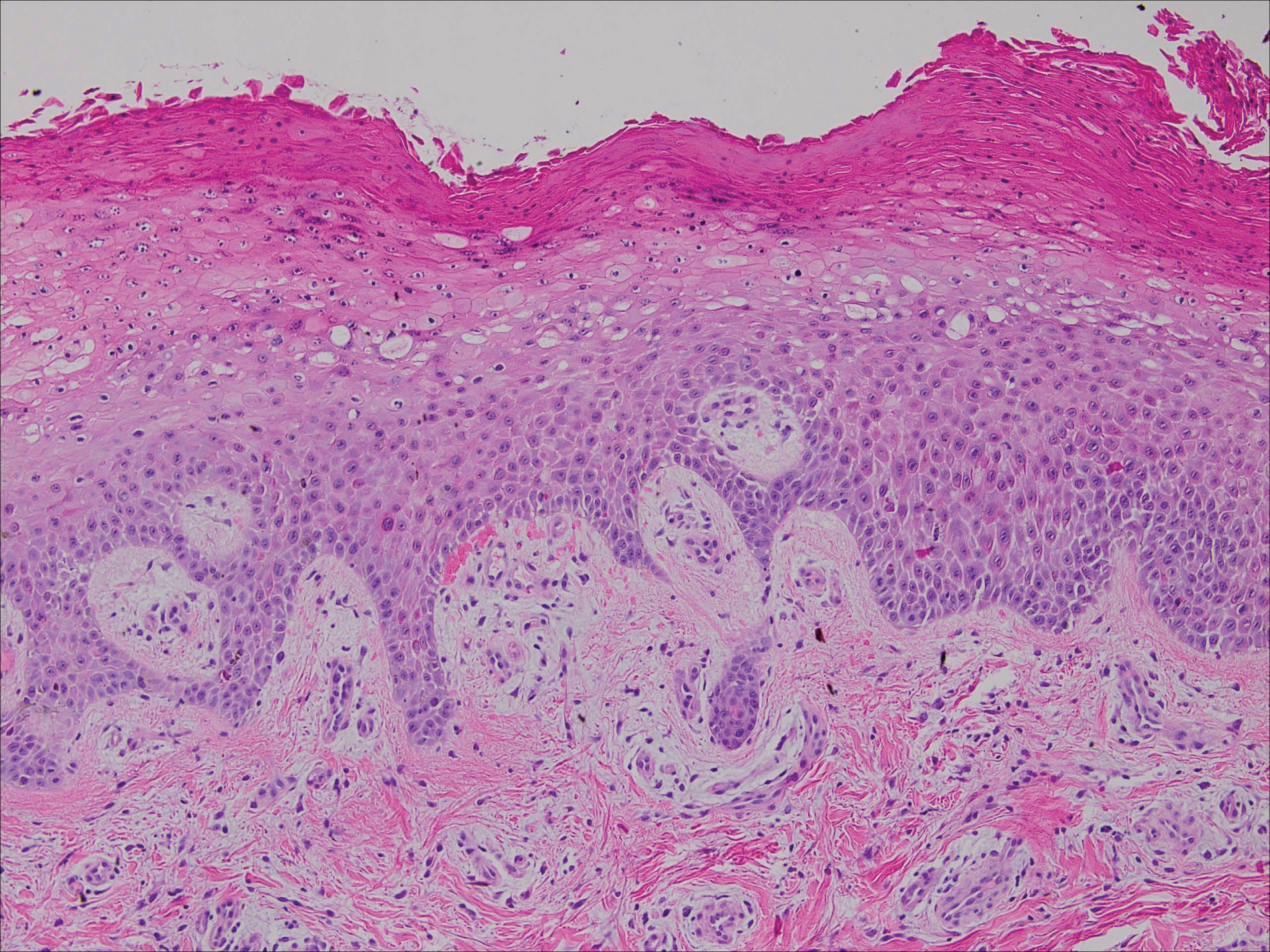

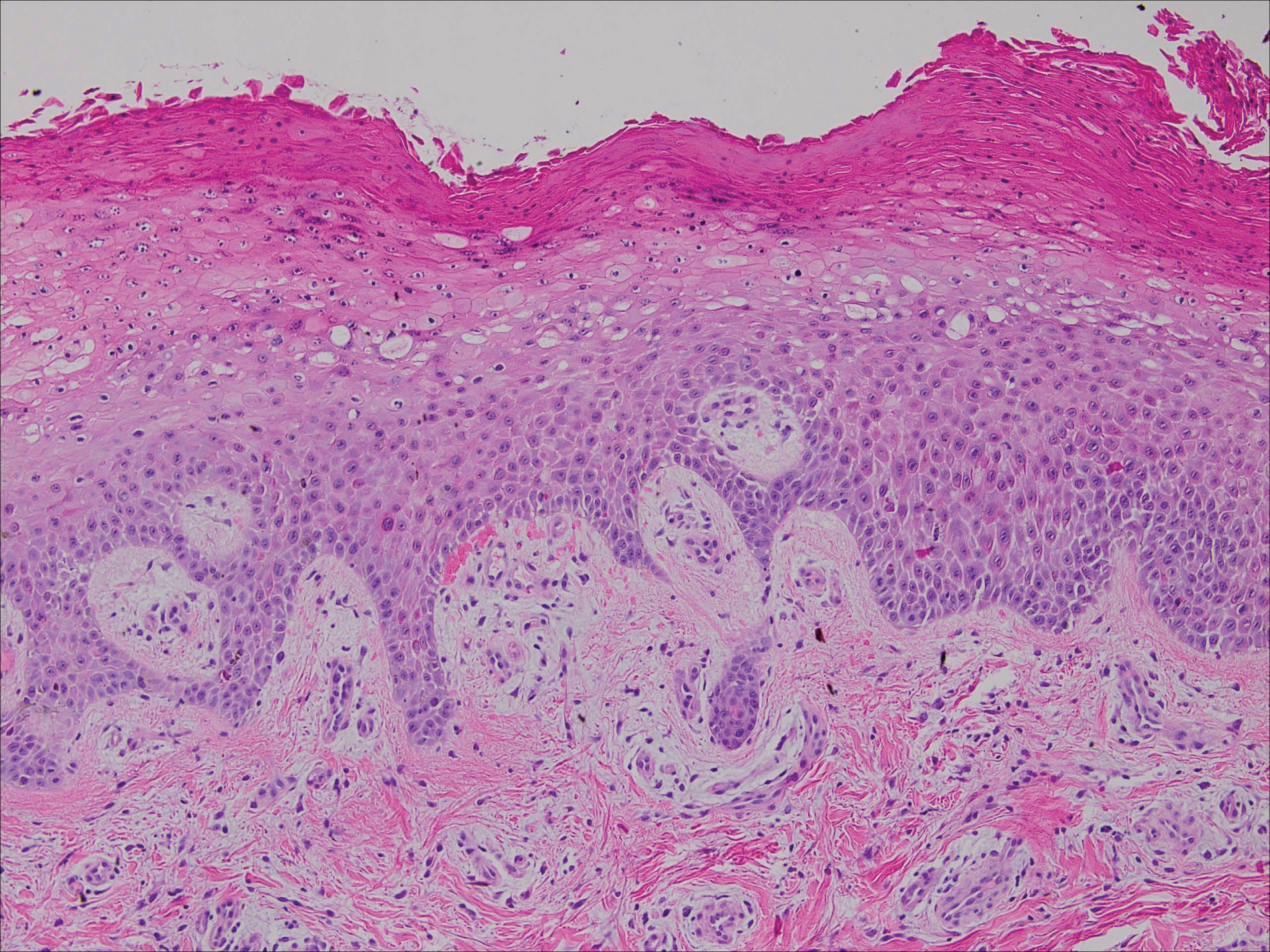

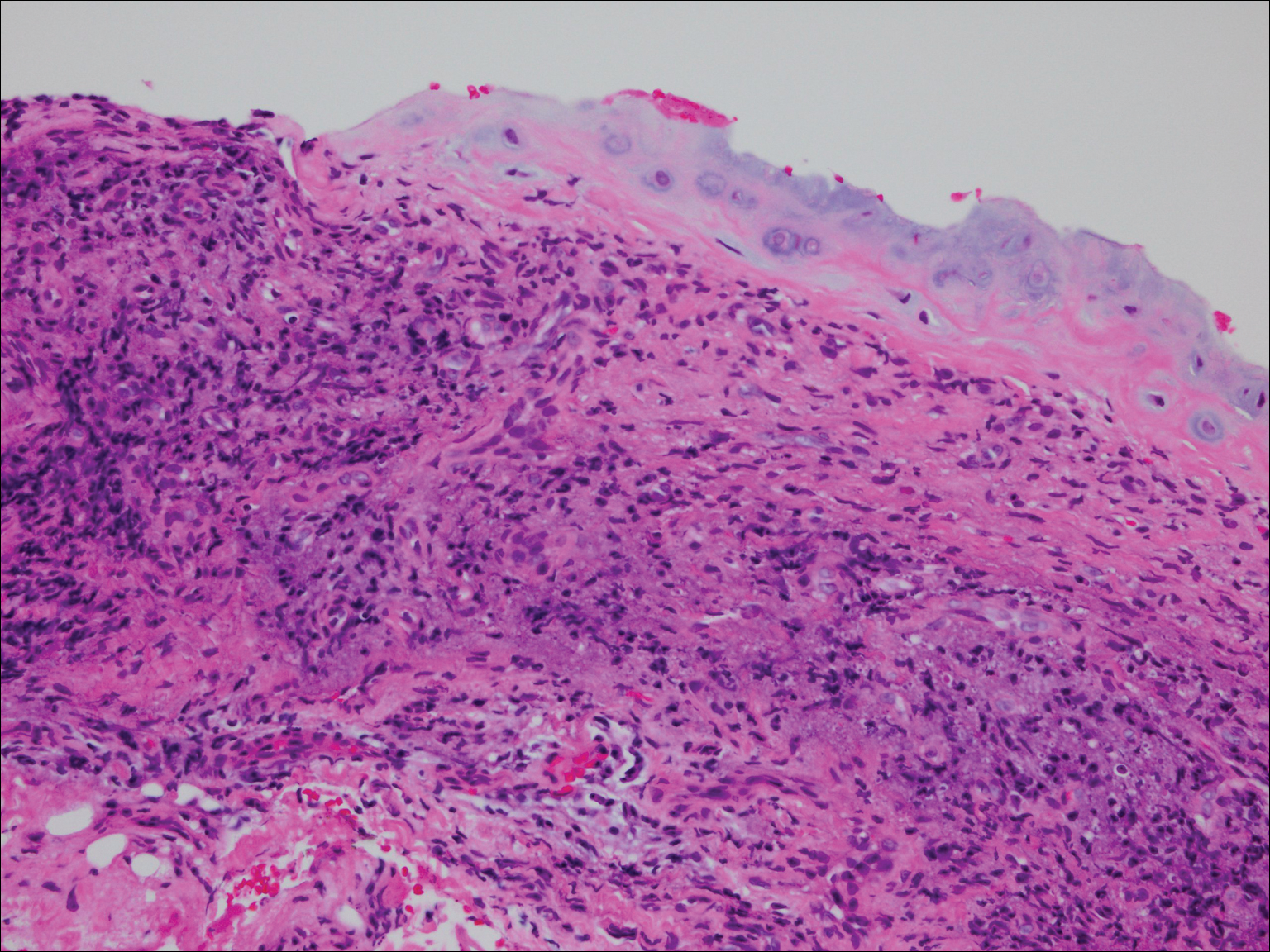

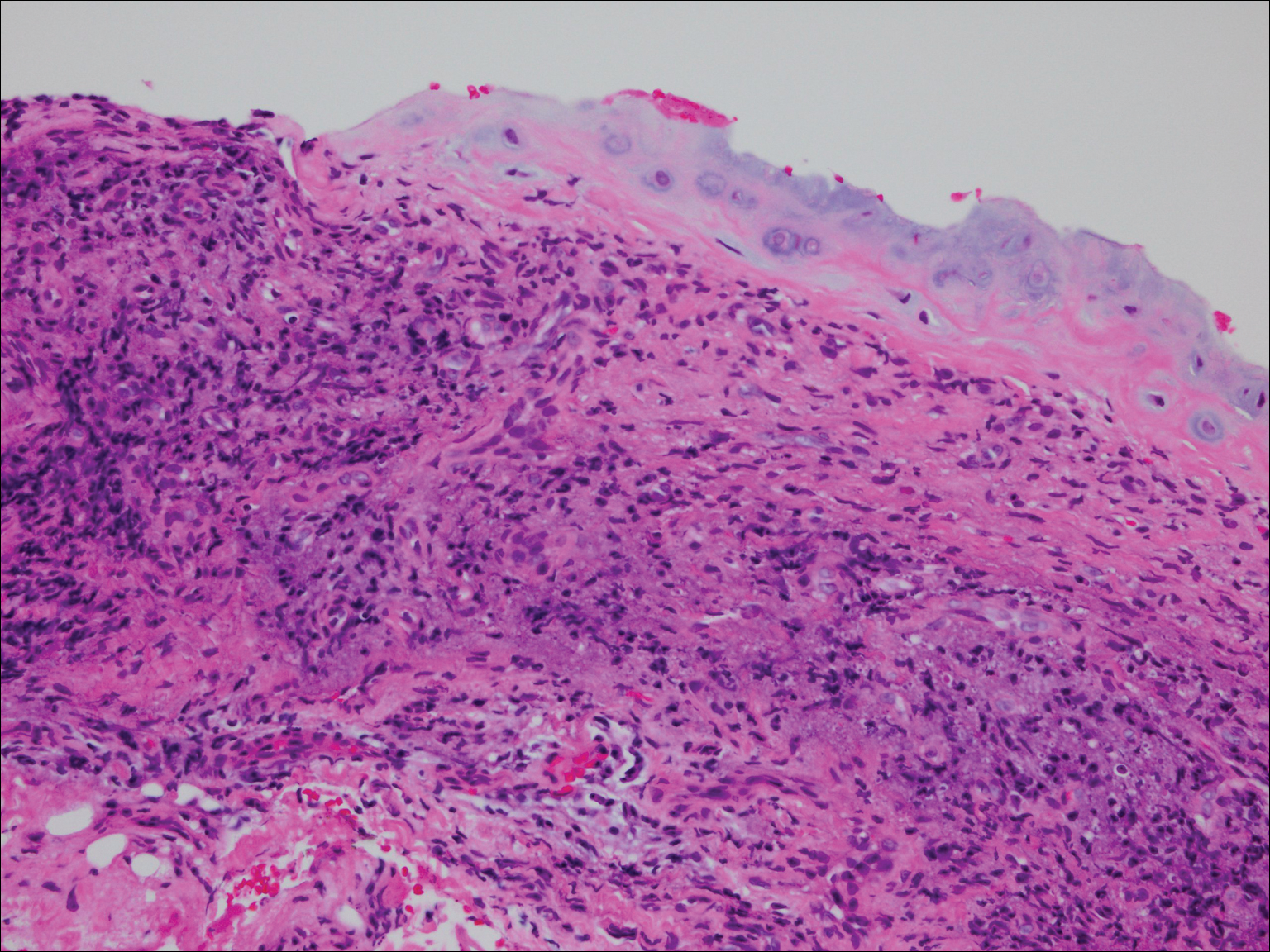

Upon initial presentation the patient appeared weak and fatigued, though vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed multiple flaccid bullae in the web spaces of the hands and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts on the bilateral wrists. She also had violaceous patches in the extensor creases of the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints, which were strikingly symmetric (Figure 1). Prominent flaccid bullae and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts also were present on the bilateral shins and dorsal aspects of the feet (Figure 2). No oral ulcers were present. A punch biopsy from the dorsal aspect of the left foot revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with prominent ballooning degeneration and hyperkeratosis/parakeratosis (Figure 3); a periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms.

Given the biopsy results and clinical presentation, a nutritional deficiency was suspected and serum levels of zinc, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, and vitamin B3 were assessed. Vitamins B1, B2

Zinc is an essential trace element and can be found in high concentration in foods such as shellfish, green vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains.6 The majority of zinc is absorbed in the jejunum; as such, many cases of acquired zinc deficiency leading to AE are dueto disorders that affect the small intestine.2 Conditions that may lead to poor gastrointestinal zinc absorption include alcoholism, eating disorders, TPN, burns, surgery, and malignancies.2,7

Diagnosis typically is made based on characteristic clinical features, biopsy results, and a measurement of the serum zinc concentration. Although a low serum zinc level supports the diagnosis, serum zinc concentration is not a reliable indicator of body zinc stores and a normal serum zinc concentration does not rule out AE. The gold standard for diagnosis is the resolution of lesions after zinc supplementation.1 Notably, because the production of alkaline phosphatase is dependent on zinc, levels of this enzyme also may be low in cases of AE,6 as in our patient.

The clinical manifestations of AE can vary greatly; patients may initially present with eczematous pink scaly plaques, which may subsequently become vesicular, bullous, pustular, or desquamative. The lesions may develop over the arms and legs as well as the anogenital and periorificial areas.5 Other notable manifestations that may present early in the course of AE include angular cheilitis followed by paronychia. In patients who are not promptly treated, long-term zinc deficiency may lead to growth delay, mental slowing, poor wound healing, anemia, and anorexia.5 Of note, deficiencies of branched-chain amino acids and essential fatty acids may appear clinically similar to AE.2

Zinc replacement is the treatment of choice for patients with AE due to dietary deficiency, and replacement therapy should begin with 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily of elemental zinc.5 Response to acquired AE with zinc supplementation often is rapid. Lesions tend to resolve within days to weeks depending on the degree of deficiency.2

Although AE is an uncommon dermatosis in the United States, it is an important diagnosis to make because its clinical features are fairly specific and early zinc supplementation allows for full resolution of the disease without permanent sequelae. The diagnosis of AE should be strongly considered when features of an acral bullous dermatosis are combined with a fissured dermatitis of extensor joints of the hands or elbows. It is particularly important to recognize that alcoholics, burn victims, postsurgical patients, and those with malignancies and eating disorders are at an increased risk for developing this nutritional deficiency.

- Kumar P, Lal NR, Mondal AK, et al. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Suchithra N, Sreejith P, Pappachan JM, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like skin eruption in a case of short bowel syndrome following jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:20.

- Sundaram A, Koutkia P, Apovian CM. Nutritional management of short bowel syndrome in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:207-220.

- Griffin IJ, Kim SC, Hicks PD, et al. Zinc metabolism in adolescents with Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:235-239.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism [published online October 30, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Cheshire H, Stather P, Vorster J. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica due to zinc deficiency in a patient with pre-existing Darier’s disease. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2009;3:41-43.

- Strumia R. Dermatologic signs in patients with eating disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:165-173.

To the Editor:

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is an inherited defect in zinc absorption that leads to hypozincemia. Its clinical presentation can vary based on serum zinc level and ranges from periorificial erosive dermatitis to psoriasiform dermatitis.1 Recognition of the cutaneous manifestations of zinc deficiency can lead to early intervention with zinc supplementation and prevention of long-term morbidity and even mortality. In our case, the coexistence of a bullous acral dermatosis with the additional feature of extensor digital dermatitis with fissuring suggests a diagnosis of AE and can alert the astute clinician to the need for testing of serum zinc levels and/or treatment with zinc supplementation. Causes of acquired zinc deficiency that have been reported in the literature include eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, Crohn disease, food allergy, intestinal parasitic infestations, and an inborn error of metabolism known as nonketotic hyperglycemia (Table).2-4

RELATED ARTICLE: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica Secondary to Alcoholism

A 42-year-old woman with a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and short bowel syndrome due to multiple small bowel obstructions with subsequent bowel resections who was on chronic total parenteral nutrition (TPN) presented with bullae on the hands, shins, and feet. The patient initially noticed small erythematous macules on the hands and feet months prior to presentation. Three weeks prior to presentation, bullae started to form on the hands, mostly between the web spaces; dorsal aspects of the feet; and anterior aspects of the shins. The patient denied any oral ulcers. One day prior to presentation the patient was seen at an outside hospital and was started on prednisone 5 mg daily, oral clindamycin, mupirocin ointment, and nystatin-triamcinolone cream. These medications failed to improve her condition. On review of systems, the patient denied any fever, chills, eye pain, or dysuria.

Upon initial presentation the patient appeared weak and fatigued, though vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed multiple flaccid bullae in the web spaces of the hands and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts on the bilateral wrists. She also had violaceous patches in the extensor creases of the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints, which were strikingly symmetric (Figure 1). Prominent flaccid bullae and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts also were present on the bilateral shins and dorsal aspects of the feet (Figure 2). No oral ulcers were present. A punch biopsy from the dorsal aspect of the left foot revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with prominent ballooning degeneration and hyperkeratosis/parakeratosis (Figure 3); a periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms.

Given the biopsy results and clinical presentation, a nutritional deficiency was suspected and serum levels of zinc, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, and vitamin B3 were assessed. Vitamins B1, B2

Zinc is an essential trace element and can be found in high concentration in foods such as shellfish, green vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains.6 The majority of zinc is absorbed in the jejunum; as such, many cases of acquired zinc deficiency leading to AE are dueto disorders that affect the small intestine.2 Conditions that may lead to poor gastrointestinal zinc absorption include alcoholism, eating disorders, TPN, burns, surgery, and malignancies.2,7

Diagnosis typically is made based on characteristic clinical features, biopsy results, and a measurement of the serum zinc concentration. Although a low serum zinc level supports the diagnosis, serum zinc concentration is not a reliable indicator of body zinc stores and a normal serum zinc concentration does not rule out AE. The gold standard for diagnosis is the resolution of lesions after zinc supplementation.1 Notably, because the production of alkaline phosphatase is dependent on zinc, levels of this enzyme also may be low in cases of AE,6 as in our patient.

The clinical manifestations of AE can vary greatly; patients may initially present with eczematous pink scaly plaques, which may subsequently become vesicular, bullous, pustular, or desquamative. The lesions may develop over the arms and legs as well as the anogenital and periorificial areas.5 Other notable manifestations that may present early in the course of AE include angular cheilitis followed by paronychia. In patients who are not promptly treated, long-term zinc deficiency may lead to growth delay, mental slowing, poor wound healing, anemia, and anorexia.5 Of note, deficiencies of branched-chain amino acids and essential fatty acids may appear clinically similar to AE.2

Zinc replacement is the treatment of choice for patients with AE due to dietary deficiency, and replacement therapy should begin with 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily of elemental zinc.5 Response to acquired AE with zinc supplementation often is rapid. Lesions tend to resolve within days to weeks depending on the degree of deficiency.2

Although AE is an uncommon dermatosis in the United States, it is an important diagnosis to make because its clinical features are fairly specific and early zinc supplementation allows for full resolution of the disease without permanent sequelae. The diagnosis of AE should be strongly considered when features of an acral bullous dermatosis are combined with a fissured dermatitis of extensor joints of the hands or elbows. It is particularly important to recognize that alcoholics, burn victims, postsurgical patients, and those with malignancies and eating disorders are at an increased risk for developing this nutritional deficiency.

To the Editor:

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is an inherited defect in zinc absorption that leads to hypozincemia. Its clinical presentation can vary based on serum zinc level and ranges from periorificial erosive dermatitis to psoriasiform dermatitis.1 Recognition of the cutaneous manifestations of zinc deficiency can lead to early intervention with zinc supplementation and prevention of long-term morbidity and even mortality. In our case, the coexistence of a bullous acral dermatosis with the additional feature of extensor digital dermatitis with fissuring suggests a diagnosis of AE and can alert the astute clinician to the need for testing of serum zinc levels and/or treatment with zinc supplementation. Causes of acquired zinc deficiency that have been reported in the literature include eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, Crohn disease, food allergy, intestinal parasitic infestations, and an inborn error of metabolism known as nonketotic hyperglycemia (Table).2-4

RELATED ARTICLE: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica Secondary to Alcoholism

A 42-year-old woman with a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and short bowel syndrome due to multiple small bowel obstructions with subsequent bowel resections who was on chronic total parenteral nutrition (TPN) presented with bullae on the hands, shins, and feet. The patient initially noticed small erythematous macules on the hands and feet months prior to presentation. Three weeks prior to presentation, bullae started to form on the hands, mostly between the web spaces; dorsal aspects of the feet; and anterior aspects of the shins. The patient denied any oral ulcers. One day prior to presentation the patient was seen at an outside hospital and was started on prednisone 5 mg daily, oral clindamycin, mupirocin ointment, and nystatin-triamcinolone cream. These medications failed to improve her condition. On review of systems, the patient denied any fever, chills, eye pain, or dysuria.

Upon initial presentation the patient appeared weak and fatigued, though vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed multiple flaccid bullae in the web spaces of the hands and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts on the bilateral wrists. She also had violaceous patches in the extensor creases of the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints, which were strikingly symmetric (Figure 1). Prominent flaccid bullae and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts also were present on the bilateral shins and dorsal aspects of the feet (Figure 2). No oral ulcers were present. A punch biopsy from the dorsal aspect of the left foot revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with prominent ballooning degeneration and hyperkeratosis/parakeratosis (Figure 3); a periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms.

Given the biopsy results and clinical presentation, a nutritional deficiency was suspected and serum levels of zinc, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, and vitamin B3 were assessed. Vitamins B1, B2

Zinc is an essential trace element and can be found in high concentration in foods such as shellfish, green vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains.6 The majority of zinc is absorbed in the jejunum; as such, many cases of acquired zinc deficiency leading to AE are dueto disorders that affect the small intestine.2 Conditions that may lead to poor gastrointestinal zinc absorption include alcoholism, eating disorders, TPN, burns, surgery, and malignancies.2,7

Diagnosis typically is made based on characteristic clinical features, biopsy results, and a measurement of the serum zinc concentration. Although a low serum zinc level supports the diagnosis, serum zinc concentration is not a reliable indicator of body zinc stores and a normal serum zinc concentration does not rule out AE. The gold standard for diagnosis is the resolution of lesions after zinc supplementation.1 Notably, because the production of alkaline phosphatase is dependent on zinc, levels of this enzyme also may be low in cases of AE,6 as in our patient.

The clinical manifestations of AE can vary greatly; patients may initially present with eczematous pink scaly plaques, which may subsequently become vesicular, bullous, pustular, or desquamative. The lesions may develop over the arms and legs as well as the anogenital and periorificial areas.5 Other notable manifestations that may present early in the course of AE include angular cheilitis followed by paronychia. In patients who are not promptly treated, long-term zinc deficiency may lead to growth delay, mental slowing, poor wound healing, anemia, and anorexia.5 Of note, deficiencies of branched-chain amino acids and essential fatty acids may appear clinically similar to AE.2

Zinc replacement is the treatment of choice for patients with AE due to dietary deficiency, and replacement therapy should begin with 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily of elemental zinc.5 Response to acquired AE with zinc supplementation often is rapid. Lesions tend to resolve within days to weeks depending on the degree of deficiency.2

Although AE is an uncommon dermatosis in the United States, it is an important diagnosis to make because its clinical features are fairly specific and early zinc supplementation allows for full resolution of the disease without permanent sequelae. The diagnosis of AE should be strongly considered when features of an acral bullous dermatosis are combined with a fissured dermatitis of extensor joints of the hands or elbows. It is particularly important to recognize that alcoholics, burn victims, postsurgical patients, and those with malignancies and eating disorders are at an increased risk for developing this nutritional deficiency.

- Kumar P, Lal NR, Mondal AK, et al. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Suchithra N, Sreejith P, Pappachan JM, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like skin eruption in a case of short bowel syndrome following jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:20.

- Sundaram A, Koutkia P, Apovian CM. Nutritional management of short bowel syndrome in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:207-220.

- Griffin IJ, Kim SC, Hicks PD, et al. Zinc metabolism in adolescents with Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:235-239.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism [published online October 30, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Cheshire H, Stather P, Vorster J. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica due to zinc deficiency in a patient with pre-existing Darier’s disease. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2009;3:41-43.

- Strumia R. Dermatologic signs in patients with eating disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:165-173.

- Kumar P, Lal NR, Mondal AK, et al. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Suchithra N, Sreejith P, Pappachan JM, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like skin eruption in a case of short bowel syndrome following jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:20.

- Sundaram A, Koutkia P, Apovian CM. Nutritional management of short bowel syndrome in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:207-220.

- Griffin IJ, Kim SC, Hicks PD, et al. Zinc metabolism in adolescents with Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:235-239.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism [published online October 30, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Cheshire H, Stather P, Vorster J. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica due to zinc deficiency in a patient with pre-existing Darier’s disease. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2009;3:41-43.

- Strumia R. Dermatologic signs in patients with eating disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:165-173.

Practice Points

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica can be a manifestation of zinc deficiency.

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica should be considered in patients with poor intestinal absorption of nutrients.

Relapsing Polychondritis With Meningoencephalitis

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is an autoimmune disease affecting cartilaginous structures such as the ears, respiratory passages, joints, and cardiovascular system.1,2 In rare cases, the systemic effects of this autoimmune process can cause central nervous system (CNS) involvement such as meningoencephalitis (ME).3 In 2011, Wang et al4 described 4 cases of RP with ME and reviewed 24 cases from the literature. We present a case of a man with RP-associated ME that was responsive to steroid treatment. We also provide an updated review of the literature.

Case Report

A 44-year-old man developed gradually worsening bilateral ear pain, headaches, and seizures. He was briefly hospitalized and discharged with levetiracetam and quetiapine. However, his mental status continued to deteriorate and he was subsequently hospitalized 3 months later with confusion, hallucinations, and seizures.

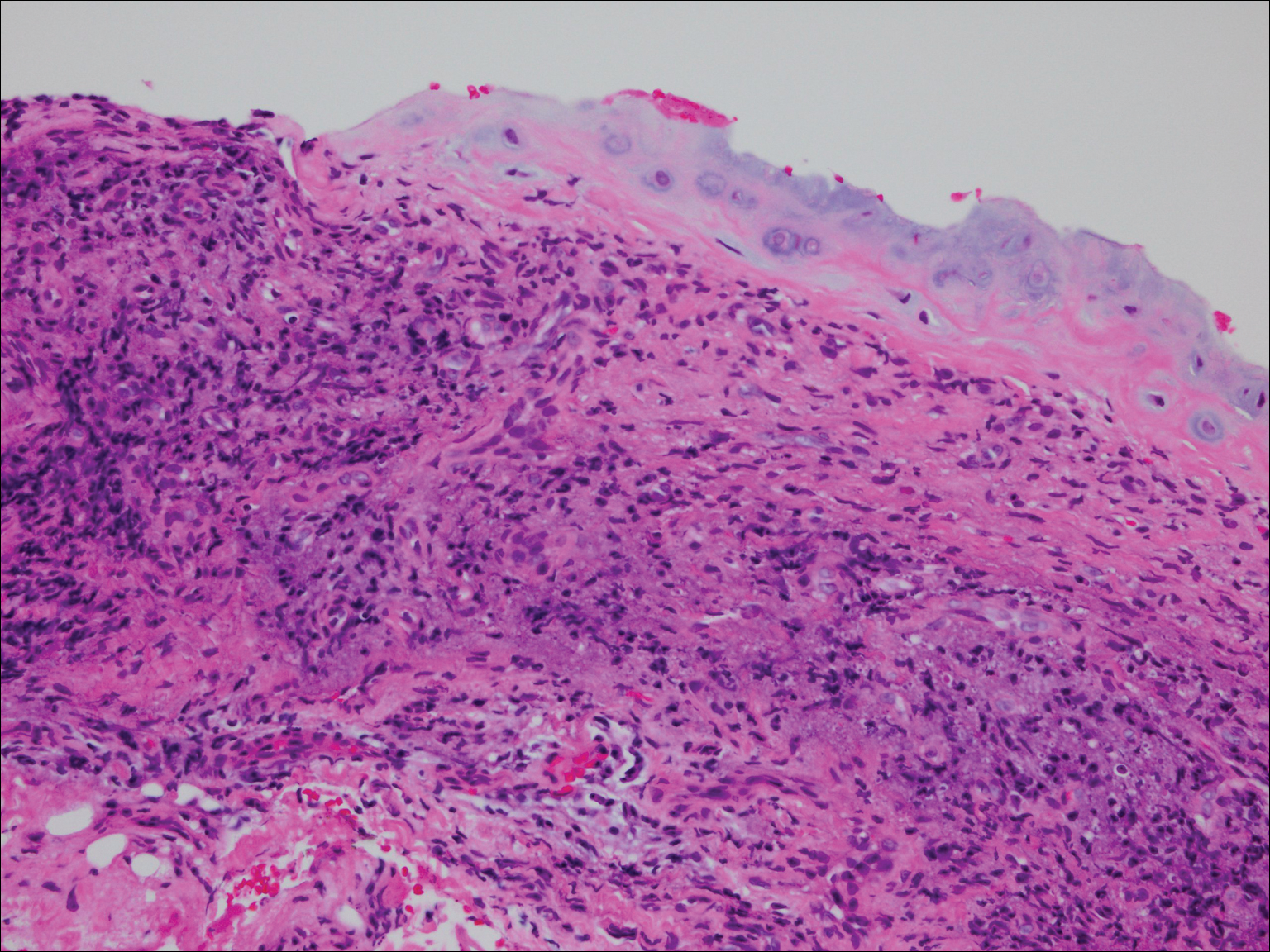

On physical examination the patient was disoriented and unable to form cohesive sentences. He had bilateral tenderness, erythema, and edema of the auricles, which notably spared the lobules (Figure 1). The conjunctivae were injected bilaterally, and joint involvement included bilateral knee tenderness and swelling. Neurologic examination revealed questionable meningeal signs but no motor or sensory deficits. An extensive laboratory workup for the etiology of his altered mental status was unremarkable, except for a mildly elevated white blood cell count in the cerebrospinal fluid with predominantly lymphocytes. No infectious etiologies were identified on laboratory testing, and rheumatologic markers were negative including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, and anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen A/Sjögren syndrome antigen B. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed nonspecific findings of bilateral T2 hyperdensities in the subcortical white matter; however, cerebral angiography revealed no evidence of vasculitis. A biopsy of the right antihelix revealed prominent perichondritis and a neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate with several lymphocytes and histiocytes (Figure 2). There was degeneration of the cartilaginous tissue with evidence of pyknotic nuclei, eosinophilia, and vacuolization of the chondrocytes. He was diagnosed with RP on the basis of clinical and histologic inflammation of the auricular cartilage, polyarthritis, and ocular inflammation.

The patient was treated with high-dose immunosuppression with methylprednisolone (1000 mg intravenous once daily for 5 days) and cyclophosphamide (one dose at 500 mg/m2), which resulted in remarkable improvement in his mental status, auricular inflammation, and knee pain. After 31 days of hospitalization the patient was discharged with a course of oral prednisone (starting at 60 mg/d, then tapered over the following 2 months) and monthly cyclophosphamide infusions (5 months total; starting at 500 mg/m2, then uptitrated to goal of 1000 mg/m2). Maintenance suppression was achieved with azathioprine (starting at 50 mg daily, then uptitrated to 100 mg daily), which was continued without any evidence of relapsed disease through his last outpatient visit 1 year after the diagnosis.

Comment

Auricular inflammation is a hallmark of RP and is present in 83% to 95% of patients.1,3 The affected ears can appear erythematous to violaceous with tender edema of the auricle that spares the lobules where no cartilage is present. The inflammation can extend into the ear canal and cause hearing loss, tinnitus, and vertigo. Histologically, RP can present with a nonspecific leukocytoclastic vasculitis and inflammatory destruction of the cartilage. Therefore, diagnosis of RP is reliant mainly on clinical characteristics rather than pathologic findings. In 1976, McAdam et al5 established diagnostic criteria for RP based on the presence of common clinical manifestations (eg, auricular chondritis, seronegative inflammatory polyarthritis, nasal chondritis, ocular inflammation). Michet et al6 later proposed major and minor criteria to classify and diagnose RP based on clinical manifestations. Diagnosis of our patient was confirmed by the presence of auricular chondritis, polyarthritis, and ocular inflammation. Diagnosing RP can be difficult because it has many systemic manifestations that can evoke a broad differential diagnosis. The time to diagnosis in our patient was 3 months, but the mean delay in diagnosis for patients with RP and ME is 2.9 years.4

The etiology of RP remains unclear, but current evidence supports an immune-mediated process directed toward proteins found in cartilage. Animal studies have suggested that RP may be driven by antibodies to matrillin 1 and type II collagen. There also may be a familial association with HLA-DR4 and genetic predisposition to autoimmune diseases in individuals affected by RP.1,3 The pathogenesis of CNS involvement in RP is thought to be due to a localized small vessel vasculitis.7,8 In our patient, however, cerebral angiography was negative for vasculitis, and thus our case may represent another mechanism for CNS involvement. There have been cases of encephalitis in RP caused by pathways other than CNS vasculitis. Kashihara et al9 reported a case of RP with encephalitis associated with antiglutamate receptor antibodies found in the cerebrospinal fluid and blood.

Treatment of RP has been based on pathophysiological considerations rather than empiric data due to its rarity. Relapsing polychondritis has been responsive to steroid treatment in reported cases as well as in our patient; however, in cases in which RP did not respond to steroids, infliximab may be effective for RP with ME.10 Further research regarding the treatment outcomes of RP with ME may be warranted.

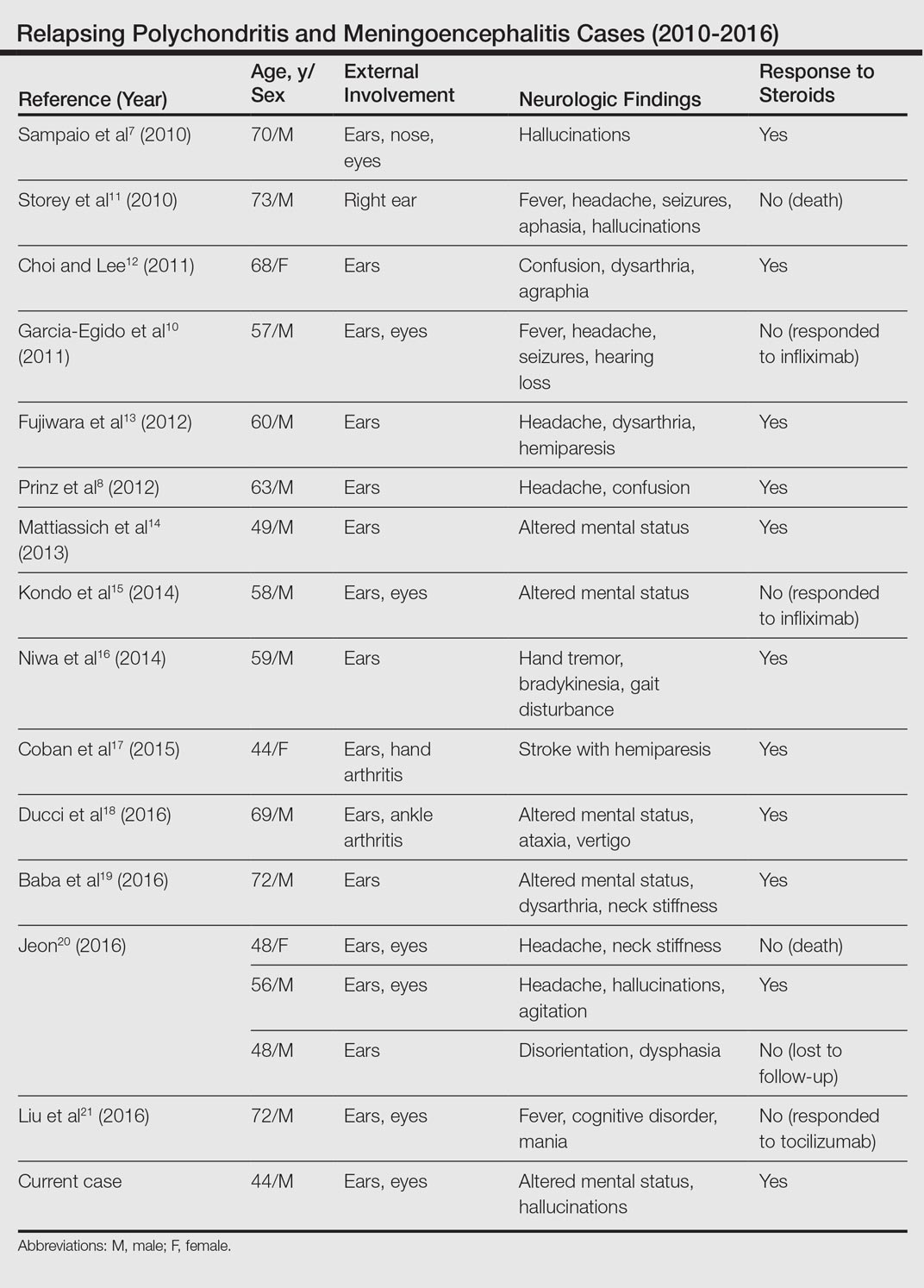

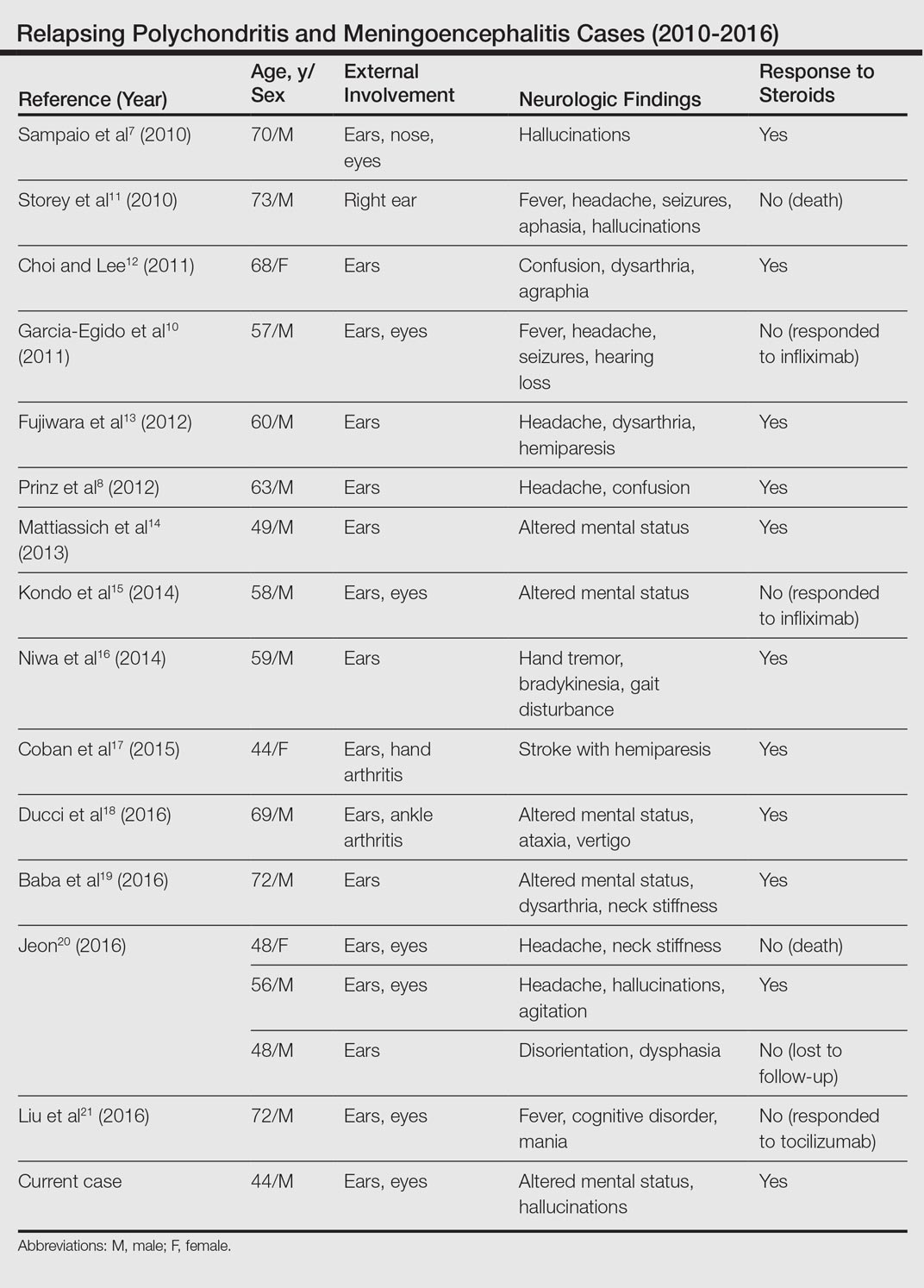

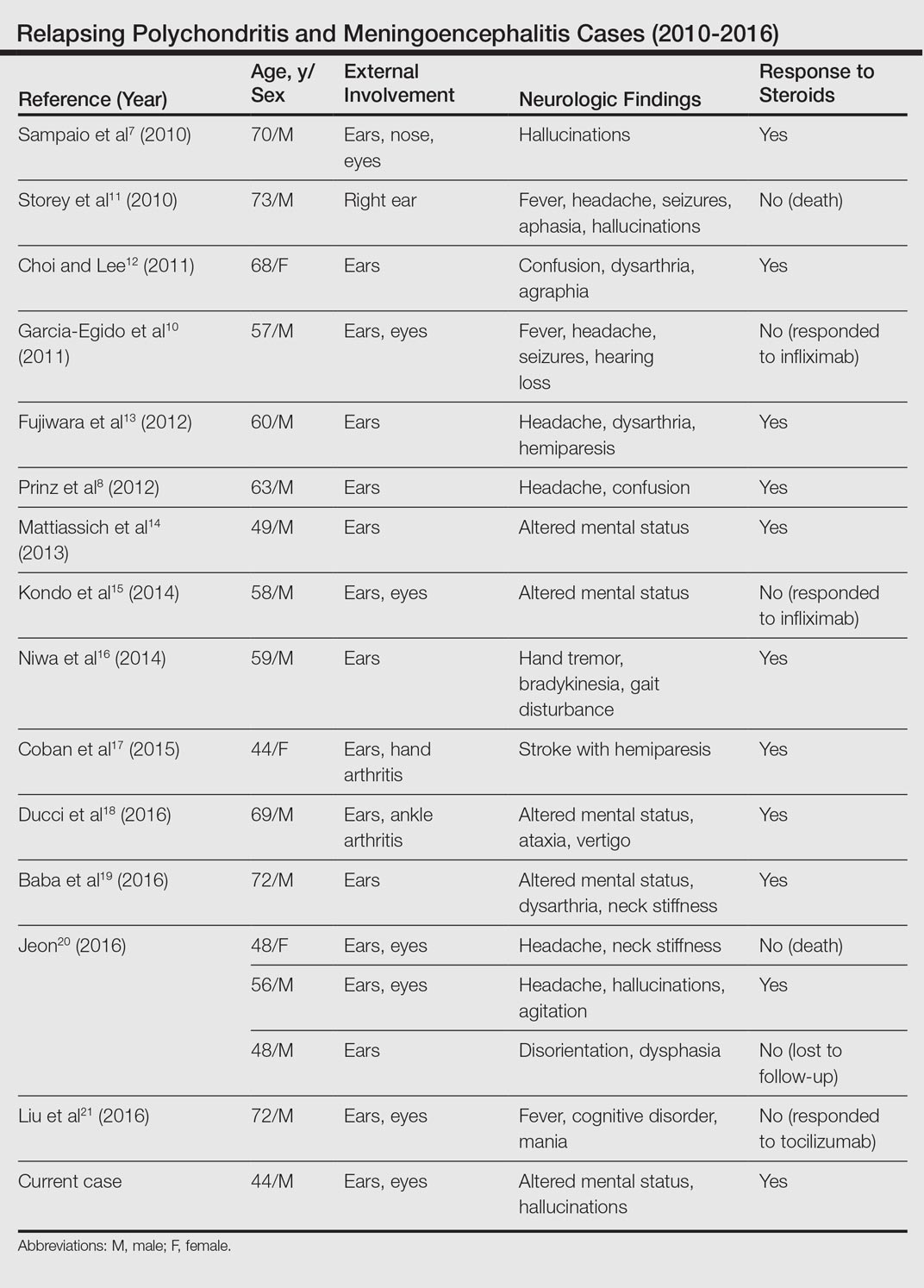

Although rare, additional cases of RP with ME have been reported (Table). Wang et al4 described a series of 28 patients with RP and ME from 1960 to 2010. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE that were published in the English-language literature from 2010 to 2016 was performed using the search terms relapsing polychondritis and nervous system. Including our patient, RP with ME was reported in 17 additional cases since Wang et al4 published their findings. These cases involved adults ranging in age from 44 to 73 years who were mainly men (14/17 [82%]). All of the patients presented with bilateral auricular chondritis, except for a case of unilateral ear involvement reported by Storey et al.11 Common neurologic manifestations included fever, headache, and altered mental status. Motor symptoms ranged from dysarthria and agraphia12 to hemiparesis.13 The mechanism of CNS involvement in RP was not identified in most cases; however, Mattiassich et al14 documented cerebral vasculitis in their patient, and Niwa et al16 found diffuse cerebral vasculitis on autopsy. Eleven of 17 (65%) cases responded to steroid treatment. Of the 6 cases in which RP did not respond to steroids, 2 patients died despite high-dose steroid treatment,11,20 2 responded to infliximab,10,15 1 responded to tocilizumab,21 and 1 was lost to follow-up after initial treatment failure.20

Conclusion

Although rare, RP should not be overlooked in the inpatient setting due to its potential for life-threatening systemic effects. Early diagnosis of this condition may be of benefit to this select population of patients, and further research regarding the prognosis, mechanisms, and treatment of RP may be necessary in the future.

- Arnaud L, Mathian A, Haroche J, et al. Pathogenesis of relapsing polychondritis: a 2013 update. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:90-95.

- Ostrowski RA, Takagishi T, Robinson J. Rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthropathies, and relapsing polychondritis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;119:449-461.

- Lahmer T, Treiber M, von Werder A, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: an autoimmune disease with many faces. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:540-546.

- Wang ZJ, Pu CQ, Wang ZJ, et al. Meningoencephalitis or meningitis in relapsing polychondritis: four case reports and a literature review. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:1608-1615.

- McAdam LP, O’Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1976;55:193-215.

- Michet C, McKenna C, Luthra H, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: survival and predictive role of early disease manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:74-78.

- Sampaio L, Silva L, Mariz E, et al. CNS involvement in relapsing polychondritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:619-620.

- Prinz S, Dafotakis M, Schneider RK, et al. The red puffy ear sign—a clinical sign to diagnose a rare cause of meningoencephalitis. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2012;80:463-467.

- Kashihara K, Kawada S, Takahashi Y. Autoantibodies to glutamate receptor GluR2 in a patient with limic encephalitis associated with relapsing polychondritis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;287:275-277.

- Garcia-Egido A, Gutierrez C, de la Fuente C, et al. Relapsing polychondritis-associated meningitis and encephalitis: response to infliximab. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:1721-1723.

- Storey K, Matej R, Rusina R. Unusual association of seronegative, nonparaneoplastic limbic encephalitis and relapsing polychondritis in a patient with history of thymectomy for myasthemia: a case study. J Neurol. 2010;258:159-161.

- Choi HJ, Lee HJ. Relapsing polychondritis with encephalitis. J Clin Rheum. 2011;6:329-331.

- Fujiwara S, Zenke K, Iwata S, et al. Relapsing polychondritis presenting as encephalitis. No Shinkei Geka. 2012;40:247-253.

- Mattiassich G, Egger M, Semlitsch G, et al. Occurrence of relapsing polychondritis with a rising cANCA titre in a cANCA-positive systemic and cerebral vasculitis patient [published online February 5, 2013]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-008717.

- Kondo T, Fukuta M, Takemoto A, et al. Limbic encephalitis associated with relapsing polychondritis responded to infliximab and maintained its condition without recurrence after discontinuation: a case report and review of the literature. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2014;76:361-368.

- Niwa A, Okamoto Y, Kondo T, et al. Perivasculitic pancencephalitis with relapsing polychondritis: an autopsy case report and review of previous cases. Intern Med. 2014;53:1191-1195.

- Coban EK, Xanmemmedoy E, Colak M, et al. A rare complication of a rare disease; stroke due to relapsing polychondritis. Ideggyogy Sz. 2015;68:429-432.

- Ducci R, Germiniani F, Czecko L, et al. Relapsing polychondritis and lymphocytic meningitis with varied neurological symptoms [published online February 5, 2016]. Rev Bras Reumatol. doi:10.1016/j.rbr.2015.09.005.

- Baba T, Kanno S, Shijo T, et al. Callosal disconnection syndrome associated with relapsing polychondritis. Intern Med. 2016;55:1191-1193.

- Jeon C. Relapsing polychondritis with central nervous system involvement: experience of three different cases in a single center. J Korean Med. 2016;31:1846-1850.

- Liu L, Liu S, Guan W, et al. Efficacy of tocilizumab for psychiatric symptoms associated with relapsing polychondritis: the first case report and review of the literature. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36:1185-1189.

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is an autoimmune disease affecting cartilaginous structures such as the ears, respiratory passages, joints, and cardiovascular system.1,2 In rare cases, the systemic effects of this autoimmune process can cause central nervous system (CNS) involvement such as meningoencephalitis (ME).3 In 2011, Wang et al4 described 4 cases of RP with ME and reviewed 24 cases from the literature. We present a case of a man with RP-associated ME that was responsive to steroid treatment. We also provide an updated review of the literature.

Case Report

A 44-year-old man developed gradually worsening bilateral ear pain, headaches, and seizures. He was briefly hospitalized and discharged with levetiracetam and quetiapine. However, his mental status continued to deteriorate and he was subsequently hospitalized 3 months later with confusion, hallucinations, and seizures.

On physical examination the patient was disoriented and unable to form cohesive sentences. He had bilateral tenderness, erythema, and edema of the auricles, which notably spared the lobules (Figure 1). The conjunctivae were injected bilaterally, and joint involvement included bilateral knee tenderness and swelling. Neurologic examination revealed questionable meningeal signs but no motor or sensory deficits. An extensive laboratory workup for the etiology of his altered mental status was unremarkable, except for a mildly elevated white blood cell count in the cerebrospinal fluid with predominantly lymphocytes. No infectious etiologies were identified on laboratory testing, and rheumatologic markers were negative including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, and anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen A/Sjögren syndrome antigen B. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed nonspecific findings of bilateral T2 hyperdensities in the subcortical white matter; however, cerebral angiography revealed no evidence of vasculitis. A biopsy of the right antihelix revealed prominent perichondritis and a neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate with several lymphocytes and histiocytes (Figure 2). There was degeneration of the cartilaginous tissue with evidence of pyknotic nuclei, eosinophilia, and vacuolization of the chondrocytes. He was diagnosed with RP on the basis of clinical and histologic inflammation of the auricular cartilage, polyarthritis, and ocular inflammation.

The patient was treated with high-dose immunosuppression with methylprednisolone (1000 mg intravenous once daily for 5 days) and cyclophosphamide (one dose at 500 mg/m2), which resulted in remarkable improvement in his mental status, auricular inflammation, and knee pain. After 31 days of hospitalization the patient was discharged with a course of oral prednisone (starting at 60 mg/d, then tapered over the following 2 months) and monthly cyclophosphamide infusions (5 months total; starting at 500 mg/m2, then uptitrated to goal of 1000 mg/m2). Maintenance suppression was achieved with azathioprine (starting at 50 mg daily, then uptitrated to 100 mg daily), which was continued without any evidence of relapsed disease through his last outpatient visit 1 year after the diagnosis.

Comment

Auricular inflammation is a hallmark of RP and is present in 83% to 95% of patients.1,3 The affected ears can appear erythematous to violaceous with tender edema of the auricle that spares the lobules where no cartilage is present. The inflammation can extend into the ear canal and cause hearing loss, tinnitus, and vertigo. Histologically, RP can present with a nonspecific leukocytoclastic vasculitis and inflammatory destruction of the cartilage. Therefore, diagnosis of RP is reliant mainly on clinical characteristics rather than pathologic findings. In 1976, McAdam et al5 established diagnostic criteria for RP based on the presence of common clinical manifestations (eg, auricular chondritis, seronegative inflammatory polyarthritis, nasal chondritis, ocular inflammation). Michet et al6 later proposed major and minor criteria to classify and diagnose RP based on clinical manifestations. Diagnosis of our patient was confirmed by the presence of auricular chondritis, polyarthritis, and ocular inflammation. Diagnosing RP can be difficult because it has many systemic manifestations that can evoke a broad differential diagnosis. The time to diagnosis in our patient was 3 months, but the mean delay in diagnosis for patients with RP and ME is 2.9 years.4

The etiology of RP remains unclear, but current evidence supports an immune-mediated process directed toward proteins found in cartilage. Animal studies have suggested that RP may be driven by antibodies to matrillin 1 and type II collagen. There also may be a familial association with HLA-DR4 and genetic predisposition to autoimmune diseases in individuals affected by RP.1,3 The pathogenesis of CNS involvement in RP is thought to be due to a localized small vessel vasculitis.7,8 In our patient, however, cerebral angiography was negative for vasculitis, and thus our case may represent another mechanism for CNS involvement. There have been cases of encephalitis in RP caused by pathways other than CNS vasculitis. Kashihara et al9 reported a case of RP with encephalitis associated with antiglutamate receptor antibodies found in the cerebrospinal fluid and blood.

Treatment of RP has been based on pathophysiological considerations rather than empiric data due to its rarity. Relapsing polychondritis has been responsive to steroid treatment in reported cases as well as in our patient; however, in cases in which RP did not respond to steroids, infliximab may be effective for RP with ME.10 Further research regarding the treatment outcomes of RP with ME may be warranted.

Although rare, additional cases of RP with ME have been reported (Table). Wang et al4 described a series of 28 patients with RP and ME from 1960 to 2010. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE that were published in the English-language literature from 2010 to 2016 was performed using the search terms relapsing polychondritis and nervous system. Including our patient, RP with ME was reported in 17 additional cases since Wang et al4 published their findings. These cases involved adults ranging in age from 44 to 73 years who were mainly men (14/17 [82%]). All of the patients presented with bilateral auricular chondritis, except for a case of unilateral ear involvement reported by Storey et al.11 Common neurologic manifestations included fever, headache, and altered mental status. Motor symptoms ranged from dysarthria and agraphia12 to hemiparesis.13 The mechanism of CNS involvement in RP was not identified in most cases; however, Mattiassich et al14 documented cerebral vasculitis in their patient, and Niwa et al16 found diffuse cerebral vasculitis on autopsy. Eleven of 17 (65%) cases responded to steroid treatment. Of the 6 cases in which RP did not respond to steroids, 2 patients died despite high-dose steroid treatment,11,20 2 responded to infliximab,10,15 1 responded to tocilizumab,21 and 1 was lost to follow-up after initial treatment failure.20

Conclusion

Although rare, RP should not be overlooked in the inpatient setting due to its potential for life-threatening systemic effects. Early diagnosis of this condition may be of benefit to this select population of patients, and further research regarding the prognosis, mechanisms, and treatment of RP may be necessary in the future.

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is an autoimmune disease affecting cartilaginous structures such as the ears, respiratory passages, joints, and cardiovascular system.1,2 In rare cases, the systemic effects of this autoimmune process can cause central nervous system (CNS) involvement such as meningoencephalitis (ME).3 In 2011, Wang et al4 described 4 cases of RP with ME and reviewed 24 cases from the literature. We present a case of a man with RP-associated ME that was responsive to steroid treatment. We also provide an updated review of the literature.

Case Report

A 44-year-old man developed gradually worsening bilateral ear pain, headaches, and seizures. He was briefly hospitalized and discharged with levetiracetam and quetiapine. However, his mental status continued to deteriorate and he was subsequently hospitalized 3 months later with confusion, hallucinations, and seizures.

On physical examination the patient was disoriented and unable to form cohesive sentences. He had bilateral tenderness, erythema, and edema of the auricles, which notably spared the lobules (Figure 1). The conjunctivae were injected bilaterally, and joint involvement included bilateral knee tenderness and swelling. Neurologic examination revealed questionable meningeal signs but no motor or sensory deficits. An extensive laboratory workup for the etiology of his altered mental status was unremarkable, except for a mildly elevated white blood cell count in the cerebrospinal fluid with predominantly lymphocytes. No infectious etiologies were identified on laboratory testing, and rheumatologic markers were negative including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, and anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen A/Sjögren syndrome antigen B. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed nonspecific findings of bilateral T2 hyperdensities in the subcortical white matter; however, cerebral angiography revealed no evidence of vasculitis. A biopsy of the right antihelix revealed prominent perichondritis and a neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate with several lymphocytes and histiocytes (Figure 2). There was degeneration of the cartilaginous tissue with evidence of pyknotic nuclei, eosinophilia, and vacuolization of the chondrocytes. He was diagnosed with RP on the basis of clinical and histologic inflammation of the auricular cartilage, polyarthritis, and ocular inflammation.

The patient was treated with high-dose immunosuppression with methylprednisolone (1000 mg intravenous once daily for 5 days) and cyclophosphamide (one dose at 500 mg/m2), which resulted in remarkable improvement in his mental status, auricular inflammation, and knee pain. After 31 days of hospitalization the patient was discharged with a course of oral prednisone (starting at 60 mg/d, then tapered over the following 2 months) and monthly cyclophosphamide infusions (5 months total; starting at 500 mg/m2, then uptitrated to goal of 1000 mg/m2). Maintenance suppression was achieved with azathioprine (starting at 50 mg daily, then uptitrated to 100 mg daily), which was continued without any evidence of relapsed disease through his last outpatient visit 1 year after the diagnosis.

Comment

Auricular inflammation is a hallmark of RP and is present in 83% to 95% of patients.1,3 The affected ears can appear erythematous to violaceous with tender edema of the auricle that spares the lobules where no cartilage is present. The inflammation can extend into the ear canal and cause hearing loss, tinnitus, and vertigo. Histologically, RP can present with a nonspecific leukocytoclastic vasculitis and inflammatory destruction of the cartilage. Therefore, diagnosis of RP is reliant mainly on clinical characteristics rather than pathologic findings. In 1976, McAdam et al5 established diagnostic criteria for RP based on the presence of common clinical manifestations (eg, auricular chondritis, seronegative inflammatory polyarthritis, nasal chondritis, ocular inflammation). Michet et al6 later proposed major and minor criteria to classify and diagnose RP based on clinical manifestations. Diagnosis of our patient was confirmed by the presence of auricular chondritis, polyarthritis, and ocular inflammation. Diagnosing RP can be difficult because it has many systemic manifestations that can evoke a broad differential diagnosis. The time to diagnosis in our patient was 3 months, but the mean delay in diagnosis for patients with RP and ME is 2.9 years.4

The etiology of RP remains unclear, but current evidence supports an immune-mediated process directed toward proteins found in cartilage. Animal studies have suggested that RP may be driven by antibodies to matrillin 1 and type II collagen. There also may be a familial association with HLA-DR4 and genetic predisposition to autoimmune diseases in individuals affected by RP.1,3 The pathogenesis of CNS involvement in RP is thought to be due to a localized small vessel vasculitis.7,8 In our patient, however, cerebral angiography was negative for vasculitis, and thus our case may represent another mechanism for CNS involvement. There have been cases of encephalitis in RP caused by pathways other than CNS vasculitis. Kashihara et al9 reported a case of RP with encephalitis associated with antiglutamate receptor antibodies found in the cerebrospinal fluid and blood.

Treatment of RP has been based on pathophysiological considerations rather than empiric data due to its rarity. Relapsing polychondritis has been responsive to steroid treatment in reported cases as well as in our patient; however, in cases in which RP did not respond to steroids, infliximab may be effective for RP with ME.10 Further research regarding the treatment outcomes of RP with ME may be warranted.

Although rare, additional cases of RP with ME have been reported (Table). Wang et al4 described a series of 28 patients with RP and ME from 1960 to 2010. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE that were published in the English-language literature from 2010 to 2016 was performed using the search terms relapsing polychondritis and nervous system. Including our patient, RP with ME was reported in 17 additional cases since Wang et al4 published their findings. These cases involved adults ranging in age from 44 to 73 years who were mainly men (14/17 [82%]). All of the patients presented with bilateral auricular chondritis, except for a case of unilateral ear involvement reported by Storey et al.11 Common neurologic manifestations included fever, headache, and altered mental status. Motor symptoms ranged from dysarthria and agraphia12 to hemiparesis.13 The mechanism of CNS involvement in RP was not identified in most cases; however, Mattiassich et al14 documented cerebral vasculitis in their patient, and Niwa et al16 found diffuse cerebral vasculitis on autopsy. Eleven of 17 (65%) cases responded to steroid treatment. Of the 6 cases in which RP did not respond to steroids, 2 patients died despite high-dose steroid treatment,11,20 2 responded to infliximab,10,15 1 responded to tocilizumab,21 and 1 was lost to follow-up after initial treatment failure.20

Conclusion

Although rare, RP should not be overlooked in the inpatient setting due to its potential for life-threatening systemic effects. Early diagnosis of this condition may be of benefit to this select population of patients, and further research regarding the prognosis, mechanisms, and treatment of RP may be necessary in the future.

- Arnaud L, Mathian A, Haroche J, et al. Pathogenesis of relapsing polychondritis: a 2013 update. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:90-95.

- Ostrowski RA, Takagishi T, Robinson J. Rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthropathies, and relapsing polychondritis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;119:449-461.

- Lahmer T, Treiber M, von Werder A, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: an autoimmune disease with many faces. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:540-546.

- Wang ZJ, Pu CQ, Wang ZJ, et al. Meningoencephalitis or meningitis in relapsing polychondritis: four case reports and a literature review. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:1608-1615.

- McAdam LP, O’Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1976;55:193-215.

- Michet C, McKenna C, Luthra H, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: survival and predictive role of early disease manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:74-78.

- Sampaio L, Silva L, Mariz E, et al. CNS involvement in relapsing polychondritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:619-620.

- Prinz S, Dafotakis M, Schneider RK, et al. The red puffy ear sign—a clinical sign to diagnose a rare cause of meningoencephalitis. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2012;80:463-467.

- Kashihara K, Kawada S, Takahashi Y. Autoantibodies to glutamate receptor GluR2 in a patient with limic encephalitis associated with relapsing polychondritis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;287:275-277.

- Garcia-Egido A, Gutierrez C, de la Fuente C, et al. Relapsing polychondritis-associated meningitis and encephalitis: response to infliximab. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:1721-1723.

- Storey K, Matej R, Rusina R. Unusual association of seronegative, nonparaneoplastic limbic encephalitis and relapsing polychondritis in a patient with history of thymectomy for myasthemia: a case study. J Neurol. 2010;258:159-161.

- Choi HJ, Lee HJ. Relapsing polychondritis with encephalitis. J Clin Rheum. 2011;6:329-331.

- Fujiwara S, Zenke K, Iwata S, et al. Relapsing polychondritis presenting as encephalitis. No Shinkei Geka. 2012;40:247-253.

- Mattiassich G, Egger M, Semlitsch G, et al. Occurrence of relapsing polychondritis with a rising cANCA titre in a cANCA-positive systemic and cerebral vasculitis patient [published online February 5, 2013]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-008717.

- Kondo T, Fukuta M, Takemoto A, et al. Limbic encephalitis associated with relapsing polychondritis responded to infliximab and maintained its condition without recurrence after discontinuation: a case report and review of the literature. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2014;76:361-368.

- Niwa A, Okamoto Y, Kondo T, et al. Perivasculitic pancencephalitis with relapsing polychondritis: an autopsy case report and review of previous cases. Intern Med. 2014;53:1191-1195.

- Coban EK, Xanmemmedoy E, Colak M, et al. A rare complication of a rare disease; stroke due to relapsing polychondritis. Ideggyogy Sz. 2015;68:429-432.

- Ducci R, Germiniani F, Czecko L, et al. Relapsing polychondritis and lymphocytic meningitis with varied neurological symptoms [published online February 5, 2016]. Rev Bras Reumatol. doi:10.1016/j.rbr.2015.09.005.

- Baba T, Kanno S, Shijo T, et al. Callosal disconnection syndrome associated with relapsing polychondritis. Intern Med. 2016;55:1191-1193.

- Jeon C. Relapsing polychondritis with central nervous system involvement: experience of three different cases in a single center. J Korean Med. 2016;31:1846-1850.

- Liu L, Liu S, Guan W, et al. Efficacy of tocilizumab for psychiatric symptoms associated with relapsing polychondritis: the first case report and review of the literature. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36:1185-1189.

- Arnaud L, Mathian A, Haroche J, et al. Pathogenesis of relapsing polychondritis: a 2013 update. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:90-95.

- Ostrowski RA, Takagishi T, Robinson J. Rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthropathies, and relapsing polychondritis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;119:449-461.

- Lahmer T, Treiber M, von Werder A, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: an autoimmune disease with many faces. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:540-546.

- Wang ZJ, Pu CQ, Wang ZJ, et al. Meningoencephalitis or meningitis in relapsing polychondritis: four case reports and a literature review. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:1608-1615.

- McAdam LP, O’Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1976;55:193-215.

- Michet C, McKenna C, Luthra H, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: survival and predictive role of early disease manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:74-78.

- Sampaio L, Silva L, Mariz E, et al. CNS involvement in relapsing polychondritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:619-620.

- Prinz S, Dafotakis M, Schneider RK, et al. The red puffy ear sign—a clinical sign to diagnose a rare cause of meningoencephalitis. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2012;80:463-467.

- Kashihara K, Kawada S, Takahashi Y. Autoantibodies to glutamate receptor GluR2 in a patient with limic encephalitis associated with relapsing polychondritis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;287:275-277.

- Garcia-Egido A, Gutierrez C, de la Fuente C, et al. Relapsing polychondritis-associated meningitis and encephalitis: response to infliximab. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:1721-1723.

- Storey K, Matej R, Rusina R. Unusual association of seronegative, nonparaneoplastic limbic encephalitis and relapsing polychondritis in a patient with history of thymectomy for myasthemia: a case study. J Neurol. 2010;258:159-161.

- Choi HJ, Lee HJ. Relapsing polychondritis with encephalitis. J Clin Rheum. 2011;6:329-331.

- Fujiwara S, Zenke K, Iwata S, et al. Relapsing polychondritis presenting as encephalitis. No Shinkei Geka. 2012;40:247-253.

- Mattiassich G, Egger M, Semlitsch G, et al. Occurrence of relapsing polychondritis with a rising cANCA titre in a cANCA-positive systemic and cerebral vasculitis patient [published online February 5, 2013]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-008717.

- Kondo T, Fukuta M, Takemoto A, et al. Limbic encephalitis associated with relapsing polychondritis responded to infliximab and maintained its condition without recurrence after discontinuation: a case report and review of the literature. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2014;76:361-368.

- Niwa A, Okamoto Y, Kondo T, et al. Perivasculitic pancencephalitis with relapsing polychondritis: an autopsy case report and review of previous cases. Intern Med. 2014;53:1191-1195.

- Coban EK, Xanmemmedoy E, Colak M, et al. A rare complication of a rare disease; stroke due to relapsing polychondritis. Ideggyogy Sz. 2015;68:429-432.

- Ducci R, Germiniani F, Czecko L, et al. Relapsing polychondritis and lymphocytic meningitis with varied neurological symptoms [published online February 5, 2016]. Rev Bras Reumatol. doi:10.1016/j.rbr.2015.09.005.

- Baba T, Kanno S, Shijo T, et al. Callosal disconnection syndrome associated with relapsing polychondritis. Intern Med. 2016;55:1191-1193.

- Jeon C. Relapsing polychondritis with central nervous system involvement: experience of three different cases in a single center. J Korean Med. 2016;31:1846-1850.

- Liu L, Liu S, Guan W, et al. Efficacy of tocilizumab for psychiatric symptoms associated with relapsing polychondritis: the first case report and review of the literature. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36:1185-1189.

Practice Points

- Meningoencephalitis (ME) is a potentially rare complication of relapsing polychondritis (RP).

- Treatment of ME due to RP can include high-dose steroids and biologics.