User login

Acrodermatitis Enteropathica in a Patient With Short Bowel Syndrome

To the Editor:

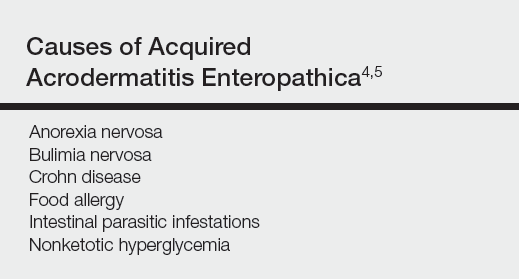

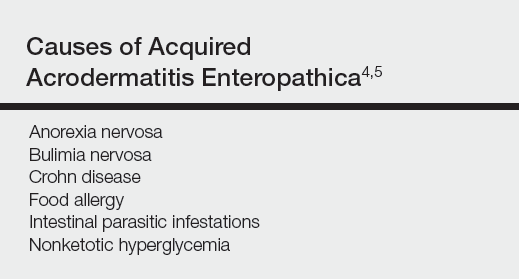

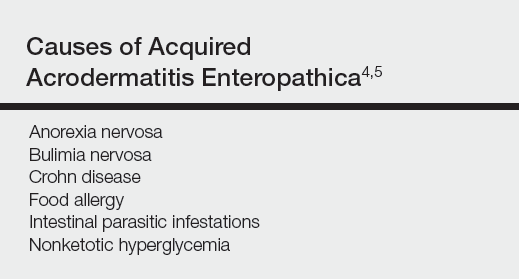

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is an inherited defect in zinc absorption that leads to hypozincemia. Its clinical presentation can vary based on serum zinc level and ranges from periorificial erosive dermatitis to psoriasiform dermatitis.1 Recognition of the cutaneous manifestations of zinc deficiency can lead to early intervention with zinc supplementation and prevention of long-term morbidity and even mortality. In our case, the coexistence of a bullous acral dermatosis with the additional feature of extensor digital dermatitis with fissuring suggests a diagnosis of AE and can alert the astute clinician to the need for testing of serum zinc levels and/or treatment with zinc supplementation. Causes of acquired zinc deficiency that have been reported in the literature include eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, Crohn disease, food allergy, intestinal parasitic infestations, and an inborn error of metabolism known as nonketotic hyperglycemia (Table).2-4

RELATED ARTICLE: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica Secondary to Alcoholism

A 42-year-old woman with a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and short bowel syndrome due to multiple small bowel obstructions with subsequent bowel resections who was on chronic total parenteral nutrition (TPN) presented with bullae on the hands, shins, and feet. The patient initially noticed small erythematous macules on the hands and feet months prior to presentation. Three weeks prior to presentation, bullae started to form on the hands, mostly between the web spaces; dorsal aspects of the feet; and anterior aspects of the shins. The patient denied any oral ulcers. One day prior to presentation the patient was seen at an outside hospital and was started on prednisone 5 mg daily, oral clindamycin, mupirocin ointment, and nystatin-triamcinolone cream. These medications failed to improve her condition. On review of systems, the patient denied any fever, chills, eye pain, or dysuria.

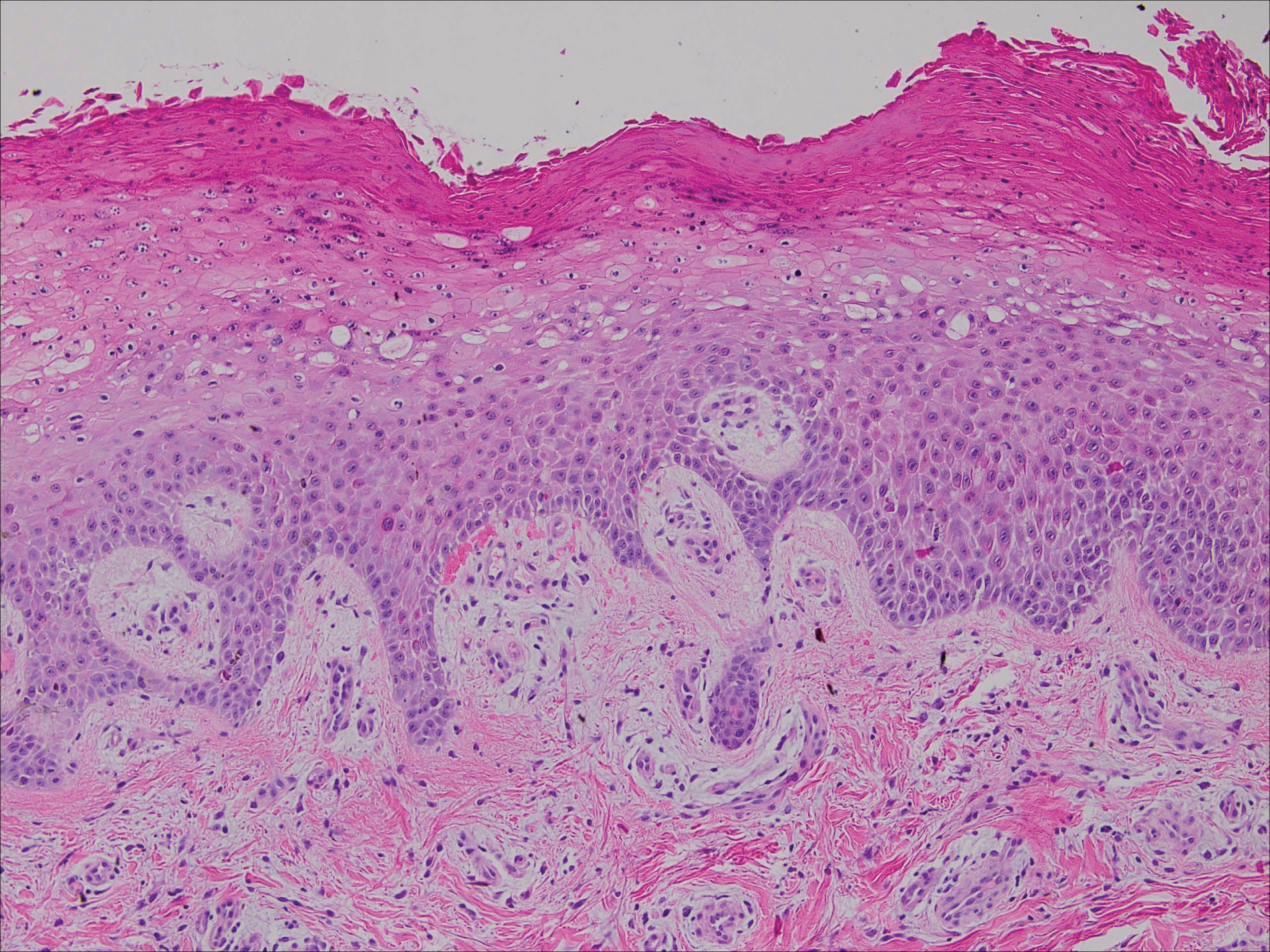

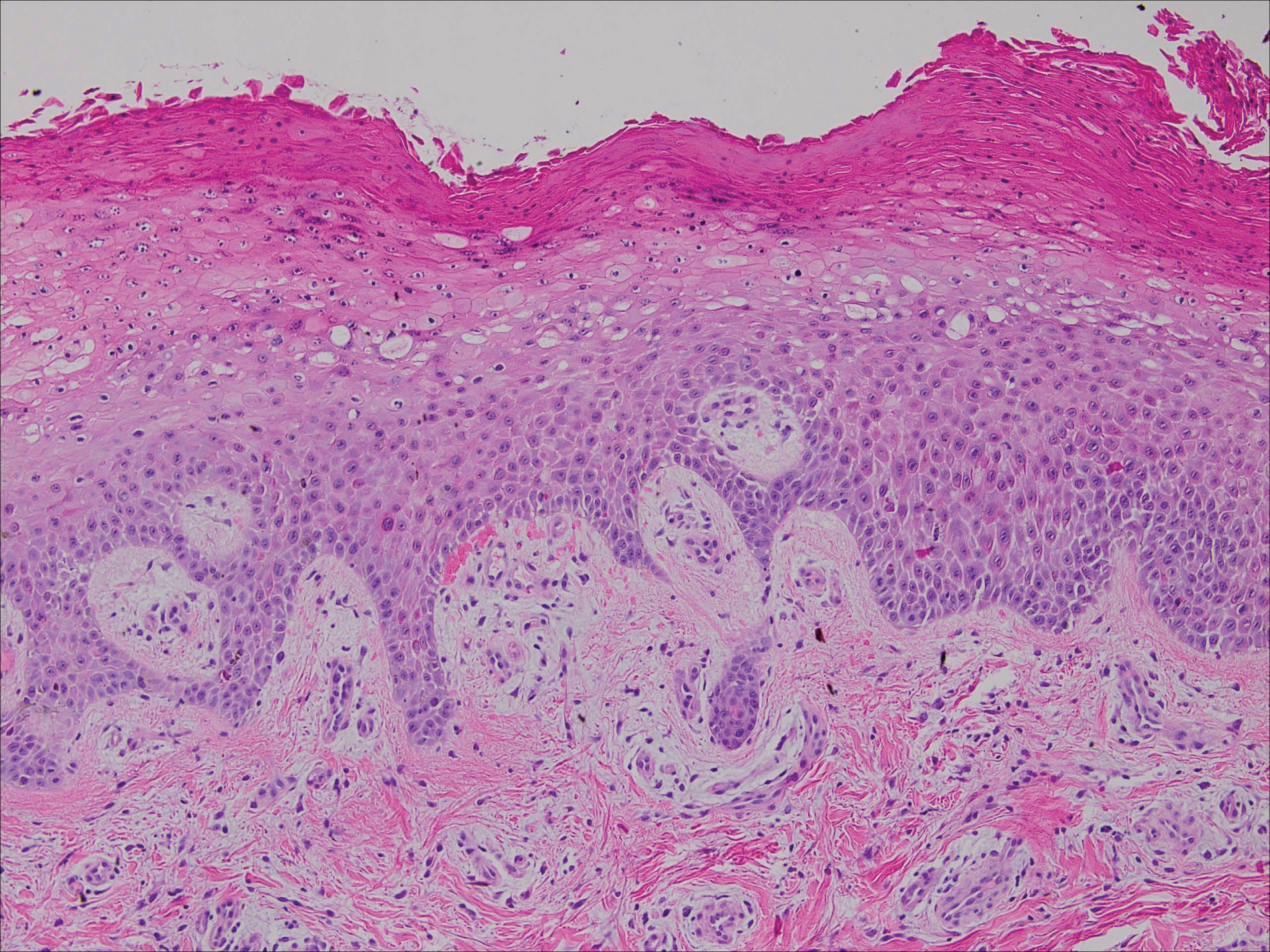

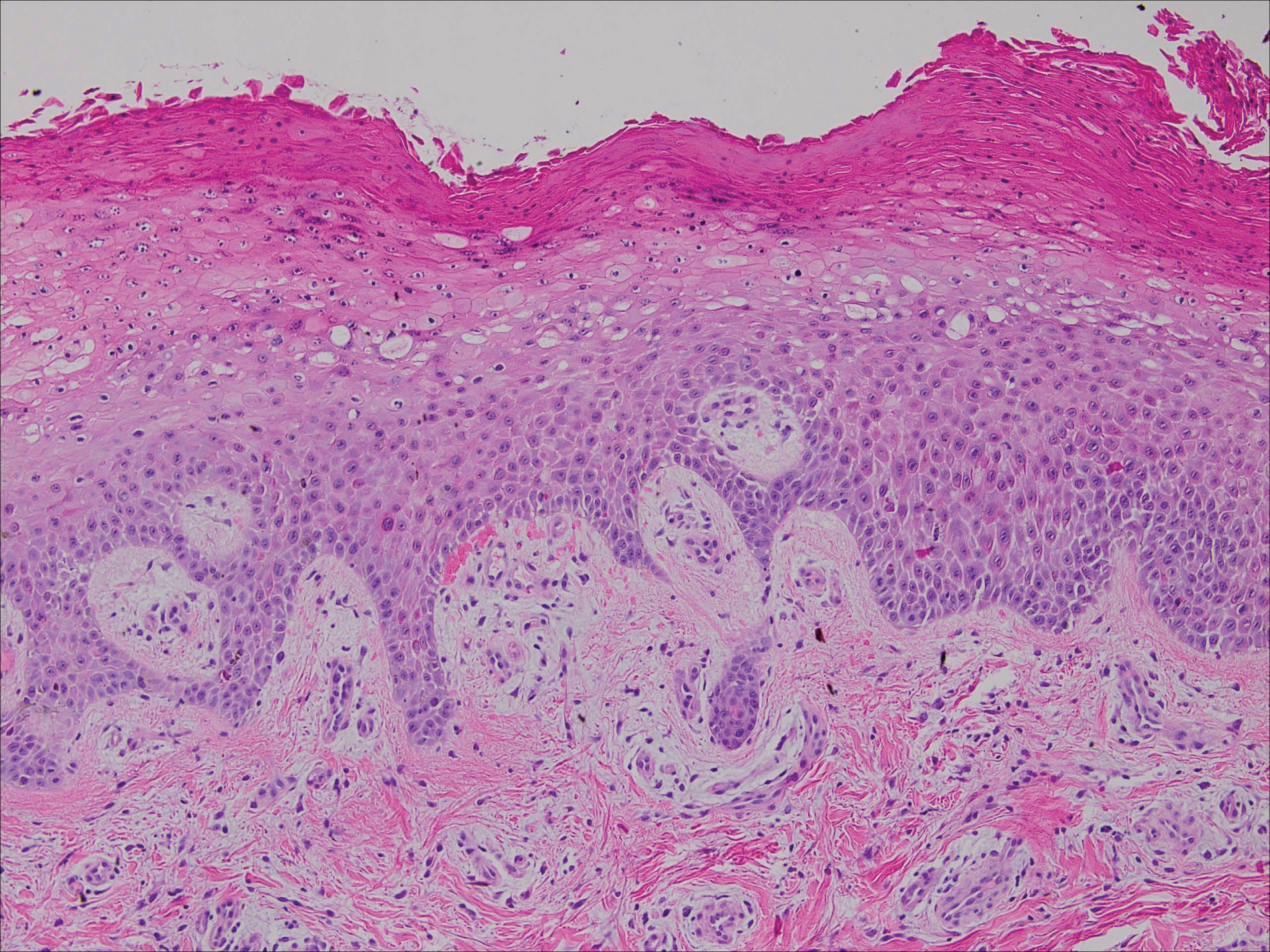

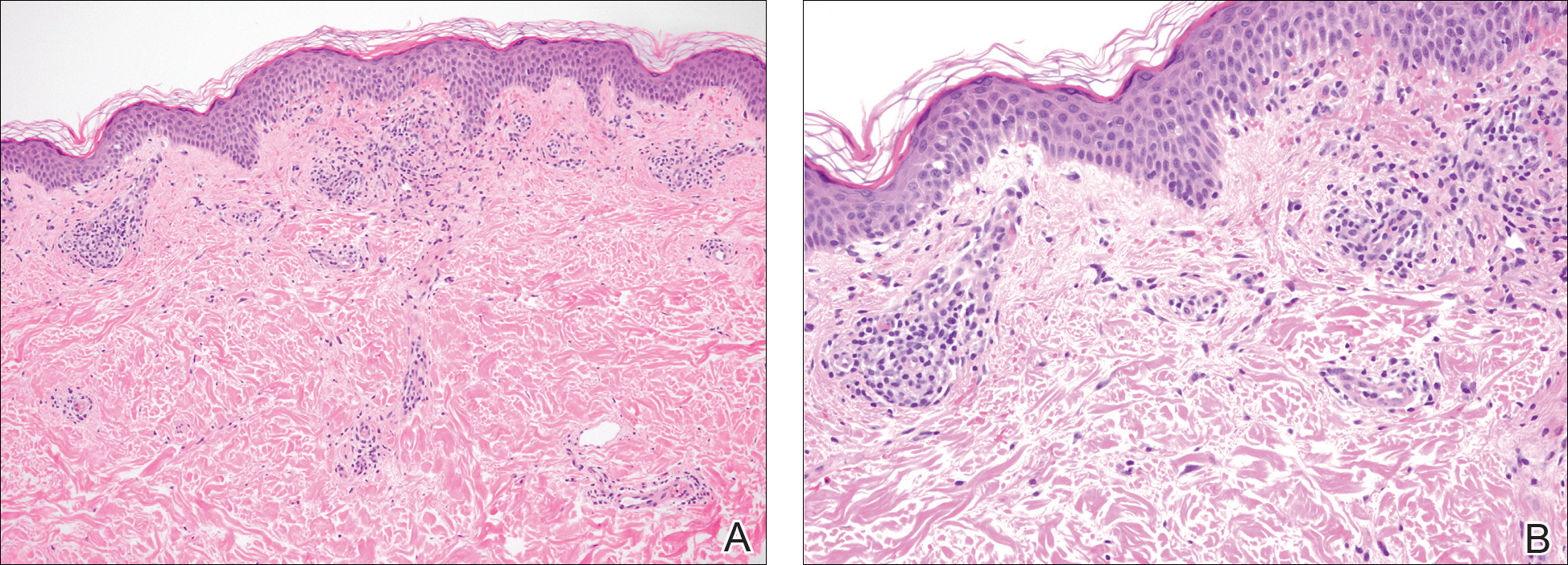

Upon initial presentation the patient appeared weak and fatigued, though vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed multiple flaccid bullae in the web spaces of the hands and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts on the bilateral wrists. She also had violaceous patches in the extensor creases of the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints, which were strikingly symmetric (Figure 1). Prominent flaccid bullae and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts also were present on the bilateral shins and dorsal aspects of the feet (Figure 2). No oral ulcers were present. A punch biopsy from the dorsal aspect of the left foot revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with prominent ballooning degeneration and hyperkeratosis/parakeratosis (Figure 3); a periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms.

Given the biopsy results and clinical presentation, a nutritional deficiency was suspected and serum levels of zinc, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, and vitamin B3 were assessed. Vitamins B1, B2

Zinc is an essential trace element and can be found in high concentration in foods such as shellfish, green vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains.6 The majority of zinc is absorbed in the jejunum; as such, many cases of acquired zinc deficiency leading to AE are dueto disorders that affect the small intestine.2 Conditions that may lead to poor gastrointestinal zinc absorption include alcoholism, eating disorders, TPN, burns, surgery, and malignancies.2,7

Diagnosis typically is made based on characteristic clinical features, biopsy results, and a measurement of the serum zinc concentration. Although a low serum zinc level supports the diagnosis, serum zinc concentration is not a reliable indicator of body zinc stores and a normal serum zinc concentration does not rule out AE. The gold standard for diagnosis is the resolution of lesions after zinc supplementation.1 Notably, because the production of alkaline phosphatase is dependent on zinc, levels of this enzyme also may be low in cases of AE,6 as in our patient.

The clinical manifestations of AE can vary greatly; patients may initially present with eczematous pink scaly plaques, which may subsequently become vesicular, bullous, pustular, or desquamative. The lesions may develop over the arms and legs as well as the anogenital and periorificial areas.5 Other notable manifestations that may present early in the course of AE include angular cheilitis followed by paronychia. In patients who are not promptly treated, long-term zinc deficiency may lead to growth delay, mental slowing, poor wound healing, anemia, and anorexia.5 Of note, deficiencies of branched-chain amino acids and essential fatty acids may appear clinically similar to AE.2

Zinc replacement is the treatment of choice for patients with AE due to dietary deficiency, and replacement therapy should begin with 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily of elemental zinc.5 Response to acquired AE with zinc supplementation often is rapid. Lesions tend to resolve within days to weeks depending on the degree of deficiency.2

Although AE is an uncommon dermatosis in the United States, it is an important diagnosis to make because its clinical features are fairly specific and early zinc supplementation allows for full resolution of the disease without permanent sequelae. The diagnosis of AE should be strongly considered when features of an acral bullous dermatosis are combined with a fissured dermatitis of extensor joints of the hands or elbows. It is particularly important to recognize that alcoholics, burn victims, postsurgical patients, and those with malignancies and eating disorders are at an increased risk for developing this nutritional deficiency.

- Kumar P, Lal NR, Mondal AK, et al. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Suchithra N, Sreejith P, Pappachan JM, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like skin eruption in a case of short bowel syndrome following jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:20.

- Sundaram A, Koutkia P, Apovian CM. Nutritional management of short bowel syndrome in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:207-220.

- Griffin IJ, Kim SC, Hicks PD, et al. Zinc metabolism in adolescents with Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:235-239.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism [published online October 30, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Cheshire H, Stather P, Vorster J. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica due to zinc deficiency in a patient with pre-existing Darier’s disease. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2009;3:41-43.

- Strumia R. Dermatologic signs in patients with eating disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:165-173.

To the Editor:

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is an inherited defect in zinc absorption that leads to hypozincemia. Its clinical presentation can vary based on serum zinc level and ranges from periorificial erosive dermatitis to psoriasiform dermatitis.1 Recognition of the cutaneous manifestations of zinc deficiency can lead to early intervention with zinc supplementation and prevention of long-term morbidity and even mortality. In our case, the coexistence of a bullous acral dermatosis with the additional feature of extensor digital dermatitis with fissuring suggests a diagnosis of AE and can alert the astute clinician to the need for testing of serum zinc levels and/or treatment with zinc supplementation. Causes of acquired zinc deficiency that have been reported in the literature include eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, Crohn disease, food allergy, intestinal parasitic infestations, and an inborn error of metabolism known as nonketotic hyperglycemia (Table).2-4

RELATED ARTICLE: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica Secondary to Alcoholism

A 42-year-old woman with a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and short bowel syndrome due to multiple small bowel obstructions with subsequent bowel resections who was on chronic total parenteral nutrition (TPN) presented with bullae on the hands, shins, and feet. The patient initially noticed small erythematous macules on the hands and feet months prior to presentation. Three weeks prior to presentation, bullae started to form on the hands, mostly between the web spaces; dorsal aspects of the feet; and anterior aspects of the shins. The patient denied any oral ulcers. One day prior to presentation the patient was seen at an outside hospital and was started on prednisone 5 mg daily, oral clindamycin, mupirocin ointment, and nystatin-triamcinolone cream. These medications failed to improve her condition. On review of systems, the patient denied any fever, chills, eye pain, or dysuria.

Upon initial presentation the patient appeared weak and fatigued, though vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed multiple flaccid bullae in the web spaces of the hands and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts on the bilateral wrists. She also had violaceous patches in the extensor creases of the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints, which were strikingly symmetric (Figure 1). Prominent flaccid bullae and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts also were present on the bilateral shins and dorsal aspects of the feet (Figure 2). No oral ulcers were present. A punch biopsy from the dorsal aspect of the left foot revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with prominent ballooning degeneration and hyperkeratosis/parakeratosis (Figure 3); a periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms.

Given the biopsy results and clinical presentation, a nutritional deficiency was suspected and serum levels of zinc, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, and vitamin B3 were assessed. Vitamins B1, B2

Zinc is an essential trace element and can be found in high concentration in foods such as shellfish, green vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains.6 The majority of zinc is absorbed in the jejunum; as such, many cases of acquired zinc deficiency leading to AE are dueto disorders that affect the small intestine.2 Conditions that may lead to poor gastrointestinal zinc absorption include alcoholism, eating disorders, TPN, burns, surgery, and malignancies.2,7

Diagnosis typically is made based on characteristic clinical features, biopsy results, and a measurement of the serum zinc concentration. Although a low serum zinc level supports the diagnosis, serum zinc concentration is not a reliable indicator of body zinc stores and a normal serum zinc concentration does not rule out AE. The gold standard for diagnosis is the resolution of lesions after zinc supplementation.1 Notably, because the production of alkaline phosphatase is dependent on zinc, levels of this enzyme also may be low in cases of AE,6 as in our patient.

The clinical manifestations of AE can vary greatly; patients may initially present with eczematous pink scaly plaques, which may subsequently become vesicular, bullous, pustular, or desquamative. The lesions may develop over the arms and legs as well as the anogenital and periorificial areas.5 Other notable manifestations that may present early in the course of AE include angular cheilitis followed by paronychia. In patients who are not promptly treated, long-term zinc deficiency may lead to growth delay, mental slowing, poor wound healing, anemia, and anorexia.5 Of note, deficiencies of branched-chain amino acids and essential fatty acids may appear clinically similar to AE.2

Zinc replacement is the treatment of choice for patients with AE due to dietary deficiency, and replacement therapy should begin with 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily of elemental zinc.5 Response to acquired AE with zinc supplementation often is rapid. Lesions tend to resolve within days to weeks depending on the degree of deficiency.2

Although AE is an uncommon dermatosis in the United States, it is an important diagnosis to make because its clinical features are fairly specific and early zinc supplementation allows for full resolution of the disease without permanent sequelae. The diagnosis of AE should be strongly considered when features of an acral bullous dermatosis are combined with a fissured dermatitis of extensor joints of the hands or elbows. It is particularly important to recognize that alcoholics, burn victims, postsurgical patients, and those with malignancies and eating disorders are at an increased risk for developing this nutritional deficiency.

To the Editor:

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is an inherited defect in zinc absorption that leads to hypozincemia. Its clinical presentation can vary based on serum zinc level and ranges from periorificial erosive dermatitis to psoriasiform dermatitis.1 Recognition of the cutaneous manifestations of zinc deficiency can lead to early intervention with zinc supplementation and prevention of long-term morbidity and even mortality. In our case, the coexistence of a bullous acral dermatosis with the additional feature of extensor digital dermatitis with fissuring suggests a diagnosis of AE and can alert the astute clinician to the need for testing of serum zinc levels and/or treatment with zinc supplementation. Causes of acquired zinc deficiency that have been reported in the literature include eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, Crohn disease, food allergy, intestinal parasitic infestations, and an inborn error of metabolism known as nonketotic hyperglycemia (Table).2-4

RELATED ARTICLE: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica Secondary to Alcoholism

A 42-year-old woman with a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and short bowel syndrome due to multiple small bowel obstructions with subsequent bowel resections who was on chronic total parenteral nutrition (TPN) presented with bullae on the hands, shins, and feet. The patient initially noticed small erythematous macules on the hands and feet months prior to presentation. Three weeks prior to presentation, bullae started to form on the hands, mostly between the web spaces; dorsal aspects of the feet; and anterior aspects of the shins. The patient denied any oral ulcers. One day prior to presentation the patient was seen at an outside hospital and was started on prednisone 5 mg daily, oral clindamycin, mupirocin ointment, and nystatin-triamcinolone cream. These medications failed to improve her condition. On review of systems, the patient denied any fever, chills, eye pain, or dysuria.

Upon initial presentation the patient appeared weak and fatigued, though vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed multiple flaccid bullae in the web spaces of the hands and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts on the bilateral wrists. She also had violaceous patches in the extensor creases of the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints, which were strikingly symmetric (Figure 1). Prominent flaccid bullae and shallow erosions with hemorrhagic crusts also were present on the bilateral shins and dorsal aspects of the feet (Figure 2). No oral ulcers were present. A punch biopsy from the dorsal aspect of the left foot revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with prominent ballooning degeneration and hyperkeratosis/parakeratosis (Figure 3); a periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms.

Given the biopsy results and clinical presentation, a nutritional deficiency was suspected and serum levels of zinc, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, and vitamin B3 were assessed. Vitamins B1, B2

Zinc is an essential trace element and can be found in high concentration in foods such as shellfish, green vegetables, legumes, nuts, and whole grains.6 The majority of zinc is absorbed in the jejunum; as such, many cases of acquired zinc deficiency leading to AE are dueto disorders that affect the small intestine.2 Conditions that may lead to poor gastrointestinal zinc absorption include alcoholism, eating disorders, TPN, burns, surgery, and malignancies.2,7

Diagnosis typically is made based on characteristic clinical features, biopsy results, and a measurement of the serum zinc concentration. Although a low serum zinc level supports the diagnosis, serum zinc concentration is not a reliable indicator of body zinc stores and a normal serum zinc concentration does not rule out AE. The gold standard for diagnosis is the resolution of lesions after zinc supplementation.1 Notably, because the production of alkaline phosphatase is dependent on zinc, levels of this enzyme also may be low in cases of AE,6 as in our patient.

The clinical manifestations of AE can vary greatly; patients may initially present with eczematous pink scaly plaques, which may subsequently become vesicular, bullous, pustular, or desquamative. The lesions may develop over the arms and legs as well as the anogenital and periorificial areas.5 Other notable manifestations that may present early in the course of AE include angular cheilitis followed by paronychia. In patients who are not promptly treated, long-term zinc deficiency may lead to growth delay, mental slowing, poor wound healing, anemia, and anorexia.5 Of note, deficiencies of branched-chain amino acids and essential fatty acids may appear clinically similar to AE.2

Zinc replacement is the treatment of choice for patients with AE due to dietary deficiency, and replacement therapy should begin with 0.5 to 1 mg/kg daily of elemental zinc.5 Response to acquired AE with zinc supplementation often is rapid. Lesions tend to resolve within days to weeks depending on the degree of deficiency.2

Although AE is an uncommon dermatosis in the United States, it is an important diagnosis to make because its clinical features are fairly specific and early zinc supplementation allows for full resolution of the disease without permanent sequelae. The diagnosis of AE should be strongly considered when features of an acral bullous dermatosis are combined with a fissured dermatitis of extensor joints of the hands or elbows. It is particularly important to recognize that alcoholics, burn victims, postsurgical patients, and those with malignancies and eating disorders are at an increased risk for developing this nutritional deficiency.

- Kumar P, Lal NR, Mondal AK, et al. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Suchithra N, Sreejith P, Pappachan JM, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like skin eruption in a case of short bowel syndrome following jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:20.

- Sundaram A, Koutkia P, Apovian CM. Nutritional management of short bowel syndrome in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:207-220.

- Griffin IJ, Kim SC, Hicks PD, et al. Zinc metabolism in adolescents with Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:235-239.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism [published online October 30, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Cheshire H, Stather P, Vorster J. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica due to zinc deficiency in a patient with pre-existing Darier’s disease. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2009;3:41-43.

- Strumia R. Dermatologic signs in patients with eating disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:165-173.

- Kumar P, Lal NR, Mondal AK, et al. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Suchithra N, Sreejith P, Pappachan JM, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like skin eruption in a case of short bowel syndrome following jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:20.

- Sundaram A, Koutkia P, Apovian CM. Nutritional management of short bowel syndrome in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:207-220.

- Griffin IJ, Kim SC, Hicks PD, et al. Zinc metabolism in adolescents with Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:235-239.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism [published online October 30, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Cheshire H, Stather P, Vorster J. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica due to zinc deficiency in a patient with pre-existing Darier’s disease. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2009;3:41-43.

- Strumia R. Dermatologic signs in patients with eating disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:165-173.

Practice Points

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica can be a manifestation of zinc deficiency.

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica should be considered in patients with poor intestinal absorption of nutrients.

Levofloxacin-Induced Purpura Annularis Telangiectodes of Majocchi

To the Editor:

Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi (PATM) is a type of pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD). Patients present with nonblanchable, annular, symmetric, purpuric, and telangiectatic patches, often on the legs, with histology revealing a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and extravasated erythrocytes.1,2 A variety of medications have been linked to the development of PPD. We describe a case of levofloxacin-induced PATM.

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Changes Associated With Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

A 42-year-old man presented with a rash on the arms, trunk, abdomen, and legs of 1 month’s duration. He reported no associated itching, bleeding, or pain, and no history of a similar rash. He had a history of hypothyroidism and had been taking levothyroxine for years. He had no known allergies and no history of childhood eczema, asthma, or allergic rhinitis. Notably, the rash started shortly after the patient finished a 2-week course of levofloxacin, an antibiotic he had not taken in the past. The patient resided with his wife, 3 children, and a pet dog, and no family members had the rash. Prior to presentation, the patient had tried econazole cream and then triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.5% without any clinical improvement.

A complete review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed scattered, reddish brown, annular, nonscaly patches on the back, abdomen (Figure 1), arms, and legs with nonblanching petechiae within the patches.

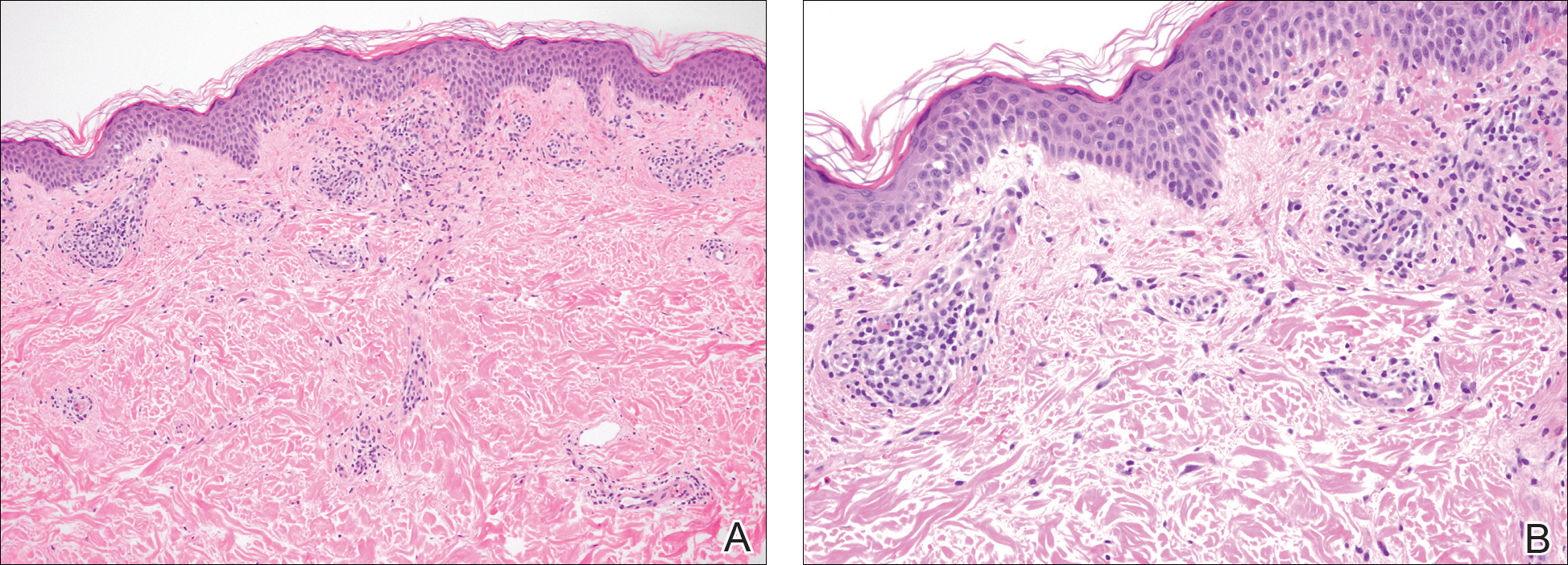

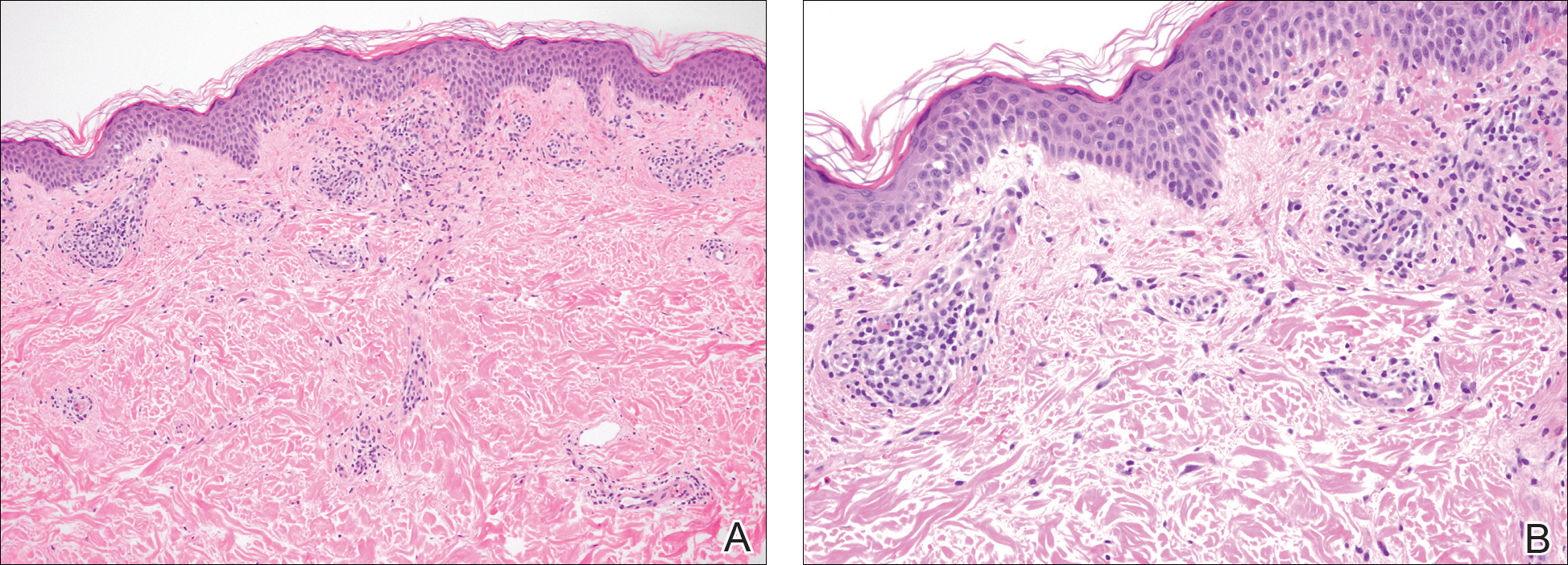

A punch biopsy of the left inner thigh demonstrated patchy interface dermatitis, superficial perivascular inflammation, and numerous extravasated red blood cells in the papillary dermis (Figure 2). The histologic features were compatible with the clinical impression of PATM. The patient presented for a follow-up visit 2 weeks later with no new lesions and the old lesions were rapidly fading (Figure 3).

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses are a group of conditions that have different clinical morphologies but similar histopathologic examinations.2 All PPDs are characterized by nonblanching, nonpalpable, purpuric lesions that often are bilaterally symmetrical and present on the legs.2,3 Although the precise etiology of these conditions is not known, most cases include a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate along with the presence of extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposition in the dermis.2 Of note, PATM often is idiopathic and patients usually present with no associated comorbidities.3 The currently established PPDs include progressive pigmentary dermatosis (Schamberg disease), PATM, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus, and eczematidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis.2,4

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

The lesions of PATM are symmetrically distributed on the bilateral legs and may be symptomatic in most cases, with severe pruritus being reported in several drug-induced PATM cases.3,5 Although the exact etiology of PPDs currently is unknown, some contributing factors that are thought to play a role include exercise, venous stasis, gravitational dependence, capillary fragility, hypertension, drugs, chemical exposure or ingestions, and contact allergy to dyes.3 Some of the drugs known to cause drug-induced PPDs fall into the class of sedatives, stimulants, antibiotics, cardiovascular drugs, vitamins, and nutritional supplements.3,6 Some medications that have been reported to cause PPDs include acetaminophen, aspirin, carbamazepine, diltiazem, furosemide, glipizide, hydralazine, infliximab, isotretinoin, lorazepam, minocycline, nitroglycerine, and sildenafil.3,7-15

Although the mechanism of drug-induced PPD is not completely understood, it is thought that the ingested substance leads to an immunologic response in the capillary endothelium, which results in a cell-mediated immune response causing vascular damage.3 The ingested substance may act as a hapten, stimulating antibody formation and immune-mediated injury, leading to the clinical presentation of nonblanching, symmetric, purpuric, telangiectatic, and atrophic patches at the site of injury.1,3

Levofloxacin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that has activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. It inhibits the enzymes DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, preventing bacteria from undergoing proper DNA synthesis.16 Our patient’s rash began shortly after a 2-week course of levofloxacin and faded within a few weeks of discontinuing the drug; the clinical presentation, time course, and histologic appearance of the lesions were consistent with the diagnosis of drug-induced PPD. Of note, solar capillaritis has been reported following a phototoxic reaction induced by levofloxacin.17 Our case differs in that our patient had annular lesions on both photoprotected and photoexposed skin.

The first-line interventions for the treatment of PPDs are nonpharmacologic, such as discontinuation of an offending drug or allergen or wearing supportive stockings if there are signs of venous stasis. Other interventions include the use of a medium- or high-potency topical corticosteroid once to twice daily to affected areas for 4 to 6 weeks.18 Some case series also have shown improvement with narrowband UVB treatment after 24 to 28 treatment sessions or with psoralen plus UVA phototherapy within 7 to 20 treatments.19,20 If the above measures are unsuccessful in resolving symptoms, other treatment alternatives may include pentoxifylline, griseofulvin, colchicine, cyclosporine, and methotrexate. The potential benefit of treatment must be weighed against the side-effect profile of these medications.2,21-24 Of note, oral rutoside (50 mg twice daily) and ascorbic acid (500 mg twice daily) were administered to 3 patients with chronic progressive pigmented purpura. At the end of the 4-week treatment period, complete clearance of skin lesions was seen in all patients with no adverse reactions noted.25

Despite these treatment options, PATM does not necessitate treatment given its benign course and often self-resolving nature.26 In cases of drug-induced PPD such as in our patient, discontinuation of the offending drug often may lead to resolution.

In summary, PATM is a PPD that has been associated with different etiologic factors. If PATM is suspected to be caused by a drug, discontinuation of the offending agent usually results in resolution of symptoms, as it did in our case with fading of lesions within a few weeks after the patient was no longer taking levofloxacin.

- Hale EK. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:17.

- Hoesly FJ, Huerter CJ, Shehan JM. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1129-1133.

- Kaplan R, Meehan SA, Leger M. A case of isotretinoin-induced purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi and review of substance-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:182-184.

- Newton RC, Raimer SS. Pigmented purpuric eruptions. Dermatol Clin. 1985;3:165-169.

- Ratnam KV, Su WP, Peters MS. Purpura simplex (inflammatory purpura without vasculitis): a clinicopathologic study of 174 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:642-647.

- Pang BK, Su D, Ratnam KV. Drug-induced purpura simplex: clinical and histological characteristics. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1993;22:870-872.

- Abeck D, Gross GE, Kuwert C, et al. Acetaminophen-induced progressive pigmentary purpura (Schamberg’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:123-124.

- Lipsker D, Cribier B, Heid E, et al. Cutaneous lymphoma manifesting as pigmented, purpuric capillaries [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1999;126:321-326.

- Peterson WC Jr, Manick KP. Purpuric eruptions associated with use of carbromal and meprobamate. Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:40-42.

- Nishioka K, Katayama I, Masuzawa M, et al. Drug-induced chronic pigmented purpura. J Dermatol. 1989;16:220-222.

- Voelter WW. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis-like reaction to topical fluorouracil. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:875-876.

- Adams BB, Gadenne AS. Glipizide-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(5, pt 2):827-829.

- Tsao H, Lerner LH. Pigmented purpuric eruption associated with injection medroxyprogesterone acetate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 1):308-310.

- Koçak AY, Akay BN, Heper AO. Sildenafil-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013;32:91-92.

- Nishioka K, Sarashi C, Katayama I. Chronic pigmented purpura induced by chemical substances. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:213-218.

- Drlica K, Zhao X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:377-392.

- Rubegni P, Feci L, Pellegrino M, et al. Photolocalized purpura during levofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:105-107.

- Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:482-488.

- Fathy H, Abdelgaber S. Treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatoses with narrow-band UVB: a report of six cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:603-606.

- Krizsa J, Hunyadi J, Dobozy A. PUVA treatment of pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis (Gougerot-Blum). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(5, pt 1):778-780.

- Panda S, Malakar S, Lahiri K. Oral pentoxifylline vs topical betamethasone in Schamberg disease: a comparative randomized investigator-blinded parallel-group trial. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:491-493.

- Tamaki K, Yasaka N, Osada A, et al. Successful treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatosis with griseofulvin. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:159-160.

- Geller M. Benefit of colchicine in the treatment of Schamberg’s disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:246.

- Okada K, Ishikawa O, Miyachi Y. Purpura pigmentosa chronica successfully treated with oral cyclosporin A. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:180-181.

- Reinhold U, Seiter S, Ugurel S, et al. Treatment of progressive pigmented purpura with oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid: an open pilot study in 3 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 1):207-208.

- Wang A, Shuja F, Chan A, et al. Unilateral purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi in an elderly male: an atypical presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19263.

To the Editor:

Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi (PATM) is a type of pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD). Patients present with nonblanchable, annular, symmetric, purpuric, and telangiectatic patches, often on the legs, with histology revealing a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and extravasated erythrocytes.1,2 A variety of medications have been linked to the development of PPD. We describe a case of levofloxacin-induced PATM.

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Changes Associated With Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

A 42-year-old man presented with a rash on the arms, trunk, abdomen, and legs of 1 month’s duration. He reported no associated itching, bleeding, or pain, and no history of a similar rash. He had a history of hypothyroidism and had been taking levothyroxine for years. He had no known allergies and no history of childhood eczema, asthma, or allergic rhinitis. Notably, the rash started shortly after the patient finished a 2-week course of levofloxacin, an antibiotic he had not taken in the past. The patient resided with his wife, 3 children, and a pet dog, and no family members had the rash. Prior to presentation, the patient had tried econazole cream and then triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.5% without any clinical improvement.

A complete review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed scattered, reddish brown, annular, nonscaly patches on the back, abdomen (Figure 1), arms, and legs with nonblanching petechiae within the patches.

A punch biopsy of the left inner thigh demonstrated patchy interface dermatitis, superficial perivascular inflammation, and numerous extravasated red blood cells in the papillary dermis (Figure 2). The histologic features were compatible with the clinical impression of PATM. The patient presented for a follow-up visit 2 weeks later with no new lesions and the old lesions were rapidly fading (Figure 3).

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses are a group of conditions that have different clinical morphologies but similar histopathologic examinations.2 All PPDs are characterized by nonblanching, nonpalpable, purpuric lesions that often are bilaterally symmetrical and present on the legs.2,3 Although the precise etiology of these conditions is not known, most cases include a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate along with the presence of extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposition in the dermis.2 Of note, PATM often is idiopathic and patients usually present with no associated comorbidities.3 The currently established PPDs include progressive pigmentary dermatosis (Schamberg disease), PATM, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus, and eczematidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis.2,4

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

The lesions of PATM are symmetrically distributed on the bilateral legs and may be symptomatic in most cases, with severe pruritus being reported in several drug-induced PATM cases.3,5 Although the exact etiology of PPDs currently is unknown, some contributing factors that are thought to play a role include exercise, venous stasis, gravitational dependence, capillary fragility, hypertension, drugs, chemical exposure or ingestions, and contact allergy to dyes.3 Some of the drugs known to cause drug-induced PPDs fall into the class of sedatives, stimulants, antibiotics, cardiovascular drugs, vitamins, and nutritional supplements.3,6 Some medications that have been reported to cause PPDs include acetaminophen, aspirin, carbamazepine, diltiazem, furosemide, glipizide, hydralazine, infliximab, isotretinoin, lorazepam, minocycline, nitroglycerine, and sildenafil.3,7-15

Although the mechanism of drug-induced PPD is not completely understood, it is thought that the ingested substance leads to an immunologic response in the capillary endothelium, which results in a cell-mediated immune response causing vascular damage.3 The ingested substance may act as a hapten, stimulating antibody formation and immune-mediated injury, leading to the clinical presentation of nonblanching, symmetric, purpuric, telangiectatic, and atrophic patches at the site of injury.1,3

Levofloxacin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that has activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. It inhibits the enzymes DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, preventing bacteria from undergoing proper DNA synthesis.16 Our patient’s rash began shortly after a 2-week course of levofloxacin and faded within a few weeks of discontinuing the drug; the clinical presentation, time course, and histologic appearance of the lesions were consistent with the diagnosis of drug-induced PPD. Of note, solar capillaritis has been reported following a phototoxic reaction induced by levofloxacin.17 Our case differs in that our patient had annular lesions on both photoprotected and photoexposed skin.

The first-line interventions for the treatment of PPDs are nonpharmacologic, such as discontinuation of an offending drug or allergen or wearing supportive stockings if there are signs of venous stasis. Other interventions include the use of a medium- or high-potency topical corticosteroid once to twice daily to affected areas for 4 to 6 weeks.18 Some case series also have shown improvement with narrowband UVB treatment after 24 to 28 treatment sessions or with psoralen plus UVA phototherapy within 7 to 20 treatments.19,20 If the above measures are unsuccessful in resolving symptoms, other treatment alternatives may include pentoxifylline, griseofulvin, colchicine, cyclosporine, and methotrexate. The potential benefit of treatment must be weighed against the side-effect profile of these medications.2,21-24 Of note, oral rutoside (50 mg twice daily) and ascorbic acid (500 mg twice daily) were administered to 3 patients with chronic progressive pigmented purpura. At the end of the 4-week treatment period, complete clearance of skin lesions was seen in all patients with no adverse reactions noted.25

Despite these treatment options, PATM does not necessitate treatment given its benign course and often self-resolving nature.26 In cases of drug-induced PPD such as in our patient, discontinuation of the offending drug often may lead to resolution.

In summary, PATM is a PPD that has been associated with different etiologic factors. If PATM is suspected to be caused by a drug, discontinuation of the offending agent usually results in resolution of symptoms, as it did in our case with fading of lesions within a few weeks after the patient was no longer taking levofloxacin.

To the Editor:

Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi (PATM) is a type of pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD). Patients present with nonblanchable, annular, symmetric, purpuric, and telangiectatic patches, often on the legs, with histology revealing a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and extravasated erythrocytes.1,2 A variety of medications have been linked to the development of PPD. We describe a case of levofloxacin-induced PATM.

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Changes Associated With Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

A 42-year-old man presented with a rash on the arms, trunk, abdomen, and legs of 1 month’s duration. He reported no associated itching, bleeding, or pain, and no history of a similar rash. He had a history of hypothyroidism and had been taking levothyroxine for years. He had no known allergies and no history of childhood eczema, asthma, or allergic rhinitis. Notably, the rash started shortly after the patient finished a 2-week course of levofloxacin, an antibiotic he had not taken in the past. The patient resided with his wife, 3 children, and a pet dog, and no family members had the rash. Prior to presentation, the patient had tried econazole cream and then triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.5% without any clinical improvement.

A complete review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed scattered, reddish brown, annular, nonscaly patches on the back, abdomen (Figure 1), arms, and legs with nonblanching petechiae within the patches.

A punch biopsy of the left inner thigh demonstrated patchy interface dermatitis, superficial perivascular inflammation, and numerous extravasated red blood cells in the papillary dermis (Figure 2). The histologic features were compatible with the clinical impression of PATM. The patient presented for a follow-up visit 2 weeks later with no new lesions and the old lesions were rapidly fading (Figure 3).

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses are a group of conditions that have different clinical morphologies but similar histopathologic examinations.2 All PPDs are characterized by nonblanching, nonpalpable, purpuric lesions that often are bilaterally symmetrical and present on the legs.2,3 Although the precise etiology of these conditions is not known, most cases include a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate along with the presence of extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposition in the dermis.2 Of note, PATM often is idiopathic and patients usually present with no associated comorbidities.3 The currently established PPDs include progressive pigmentary dermatosis (Schamberg disease), PATM, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus, and eczematidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis.2,4

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

The lesions of PATM are symmetrically distributed on the bilateral legs and may be symptomatic in most cases, with severe pruritus being reported in several drug-induced PATM cases.3,5 Although the exact etiology of PPDs currently is unknown, some contributing factors that are thought to play a role include exercise, venous stasis, gravitational dependence, capillary fragility, hypertension, drugs, chemical exposure or ingestions, and contact allergy to dyes.3 Some of the drugs known to cause drug-induced PPDs fall into the class of sedatives, stimulants, antibiotics, cardiovascular drugs, vitamins, and nutritional supplements.3,6 Some medications that have been reported to cause PPDs include acetaminophen, aspirin, carbamazepine, diltiazem, furosemide, glipizide, hydralazine, infliximab, isotretinoin, lorazepam, minocycline, nitroglycerine, and sildenafil.3,7-15

Although the mechanism of drug-induced PPD is not completely understood, it is thought that the ingested substance leads to an immunologic response in the capillary endothelium, which results in a cell-mediated immune response causing vascular damage.3 The ingested substance may act as a hapten, stimulating antibody formation and immune-mediated injury, leading to the clinical presentation of nonblanching, symmetric, purpuric, telangiectatic, and atrophic patches at the site of injury.1,3

Levofloxacin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that has activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. It inhibits the enzymes DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, preventing bacteria from undergoing proper DNA synthesis.16 Our patient’s rash began shortly after a 2-week course of levofloxacin and faded within a few weeks of discontinuing the drug; the clinical presentation, time course, and histologic appearance of the lesions were consistent with the diagnosis of drug-induced PPD. Of note, solar capillaritis has been reported following a phototoxic reaction induced by levofloxacin.17 Our case differs in that our patient had annular lesions on both photoprotected and photoexposed skin.

The first-line interventions for the treatment of PPDs are nonpharmacologic, such as discontinuation of an offending drug or allergen or wearing supportive stockings if there are signs of venous stasis. Other interventions include the use of a medium- or high-potency topical corticosteroid once to twice daily to affected areas for 4 to 6 weeks.18 Some case series also have shown improvement with narrowband UVB treatment after 24 to 28 treatment sessions or with psoralen plus UVA phototherapy within 7 to 20 treatments.19,20 If the above measures are unsuccessful in resolving symptoms, other treatment alternatives may include pentoxifylline, griseofulvin, colchicine, cyclosporine, and methotrexate. The potential benefit of treatment must be weighed against the side-effect profile of these medications.2,21-24 Of note, oral rutoside (50 mg twice daily) and ascorbic acid (500 mg twice daily) were administered to 3 patients with chronic progressive pigmented purpura. At the end of the 4-week treatment period, complete clearance of skin lesions was seen in all patients with no adverse reactions noted.25

Despite these treatment options, PATM does not necessitate treatment given its benign course and often self-resolving nature.26 In cases of drug-induced PPD such as in our patient, discontinuation of the offending drug often may lead to resolution.

In summary, PATM is a PPD that has been associated with different etiologic factors. If PATM is suspected to be caused by a drug, discontinuation of the offending agent usually results in resolution of symptoms, as it did in our case with fading of lesions within a few weeks after the patient was no longer taking levofloxacin.

- Hale EK. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:17.

- Hoesly FJ, Huerter CJ, Shehan JM. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1129-1133.

- Kaplan R, Meehan SA, Leger M. A case of isotretinoin-induced purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi and review of substance-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:182-184.

- Newton RC, Raimer SS. Pigmented purpuric eruptions. Dermatol Clin. 1985;3:165-169.

- Ratnam KV, Su WP, Peters MS. Purpura simplex (inflammatory purpura without vasculitis): a clinicopathologic study of 174 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:642-647.

- Pang BK, Su D, Ratnam KV. Drug-induced purpura simplex: clinical and histological characteristics. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1993;22:870-872.

- Abeck D, Gross GE, Kuwert C, et al. Acetaminophen-induced progressive pigmentary purpura (Schamberg’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:123-124.

- Lipsker D, Cribier B, Heid E, et al. Cutaneous lymphoma manifesting as pigmented, purpuric capillaries [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1999;126:321-326.

- Peterson WC Jr, Manick KP. Purpuric eruptions associated with use of carbromal and meprobamate. Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:40-42.

- Nishioka K, Katayama I, Masuzawa M, et al. Drug-induced chronic pigmented purpura. J Dermatol. 1989;16:220-222.

- Voelter WW. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis-like reaction to topical fluorouracil. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:875-876.

- Adams BB, Gadenne AS. Glipizide-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(5, pt 2):827-829.

- Tsao H, Lerner LH. Pigmented purpuric eruption associated with injection medroxyprogesterone acetate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 1):308-310.

- Koçak AY, Akay BN, Heper AO. Sildenafil-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013;32:91-92.

- Nishioka K, Sarashi C, Katayama I. Chronic pigmented purpura induced by chemical substances. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:213-218.

- Drlica K, Zhao X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:377-392.

- Rubegni P, Feci L, Pellegrino M, et al. Photolocalized purpura during levofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:105-107.

- Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:482-488.

- Fathy H, Abdelgaber S. Treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatoses with narrow-band UVB: a report of six cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:603-606.

- Krizsa J, Hunyadi J, Dobozy A. PUVA treatment of pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis (Gougerot-Blum). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(5, pt 1):778-780.

- Panda S, Malakar S, Lahiri K. Oral pentoxifylline vs topical betamethasone in Schamberg disease: a comparative randomized investigator-blinded parallel-group trial. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:491-493.

- Tamaki K, Yasaka N, Osada A, et al. Successful treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatosis with griseofulvin. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:159-160.

- Geller M. Benefit of colchicine in the treatment of Schamberg’s disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:246.

- Okada K, Ishikawa O, Miyachi Y. Purpura pigmentosa chronica successfully treated with oral cyclosporin A. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:180-181.

- Reinhold U, Seiter S, Ugurel S, et al. Treatment of progressive pigmented purpura with oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid: an open pilot study in 3 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 1):207-208.

- Wang A, Shuja F, Chan A, et al. Unilateral purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi in an elderly male: an atypical presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19263.

- Hale EK. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:17.

- Hoesly FJ, Huerter CJ, Shehan JM. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1129-1133.

- Kaplan R, Meehan SA, Leger M. A case of isotretinoin-induced purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi and review of substance-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:182-184.

- Newton RC, Raimer SS. Pigmented purpuric eruptions. Dermatol Clin. 1985;3:165-169.

- Ratnam KV, Su WP, Peters MS. Purpura simplex (inflammatory purpura without vasculitis): a clinicopathologic study of 174 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:642-647.

- Pang BK, Su D, Ratnam KV. Drug-induced purpura simplex: clinical and histological characteristics. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1993;22:870-872.

- Abeck D, Gross GE, Kuwert C, et al. Acetaminophen-induced progressive pigmentary purpura (Schamberg’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:123-124.

- Lipsker D, Cribier B, Heid E, et al. Cutaneous lymphoma manifesting as pigmented, purpuric capillaries [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1999;126:321-326.

- Peterson WC Jr, Manick KP. Purpuric eruptions associated with use of carbromal and meprobamate. Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:40-42.

- Nishioka K, Katayama I, Masuzawa M, et al. Drug-induced chronic pigmented purpura. J Dermatol. 1989;16:220-222.

- Voelter WW. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis-like reaction to topical fluorouracil. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:875-876.

- Adams BB, Gadenne AS. Glipizide-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(5, pt 2):827-829.

- Tsao H, Lerner LH. Pigmented purpuric eruption associated with injection medroxyprogesterone acetate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 1):308-310.

- Koçak AY, Akay BN, Heper AO. Sildenafil-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013;32:91-92.

- Nishioka K, Sarashi C, Katayama I. Chronic pigmented purpura induced by chemical substances. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:213-218.

- Drlica K, Zhao X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:377-392.

- Rubegni P, Feci L, Pellegrino M, et al. Photolocalized purpura during levofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:105-107.

- Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:482-488.

- Fathy H, Abdelgaber S. Treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatoses with narrow-band UVB: a report of six cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:603-606.

- Krizsa J, Hunyadi J, Dobozy A. PUVA treatment of pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis (Gougerot-Blum). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(5, pt 1):778-780.

- Panda S, Malakar S, Lahiri K. Oral pentoxifylline vs topical betamethasone in Schamberg disease: a comparative randomized investigator-blinded parallel-group trial. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:491-493.

- Tamaki K, Yasaka N, Osada A, et al. Successful treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatosis with griseofulvin. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:159-160.

- Geller M. Benefit of colchicine in the treatment of Schamberg’s disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:246.

- Okada K, Ishikawa O, Miyachi Y. Purpura pigmentosa chronica successfully treated with oral cyclosporin A. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:180-181.

- Reinhold U, Seiter S, Ugurel S, et al. Treatment of progressive pigmented purpura with oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid: an open pilot study in 3 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 1):207-208.

- Wang A, Shuja F, Chan A, et al. Unilateral purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi in an elderly male: an atypical presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19263.

Practice Point

- Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi, a type of pigmented purpuric dermatosis, may on occasion be triggered by a medication; therefore, a careful medication history may prove to be an important part of the workup for this eruption.