User login

Sea Buckthorn

A member of the Elaeagnaceae family, Hippophae rhamnoides, better known as sea buckthorn, is a high-altitude wild shrub endemic to Europe and Asia with edible fruits and a lengthy record of use in traditional Chinese medicine.1-6 Used as a health supplement and consumed in the diet throughout the world,5 sea buckthorn berries, seeds, and leaves have been used in traditional medicine to treat burns/injuries, edema, hypertension, inflammation, skin grafts, ulcers, and wounds.4,7

This hardy plant is associated with a wide range of biologic activities, including anti-atherogenic, anti-atopic dermatitis, antibacterial, anticancer, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-psoriasis, anti-sebum, anti-stress, anti-tumor, cytoprotective, hepatoprotective, immunomodulatory, neuroprotective, radioprotective, and tissue regenerative functions.4,5,8-11

Key Constituents

Functional constituents identified in sea buckthorn include alkaloids, carotenoids, flavonoids, lignans, organic acids, phenolic acids, proanthocyanidins, polyunsaturated acids (including omega-3, -6, -7, and -9), steroids, tannins, terpenoids, and volatile oils, as well as nutritional compounds such as minerals, proteins, and vitamins.4,5,11 Sea buckthorn pericarp oil contains copious amounts of saturated palmitic acid (29%-36%) and omega-7 unsaturated palmitoleic acid (36%-48%), which fosters cutaneous and mucosal epithelialization, as well as linoleic (10%-12%) and oleic (4%-6%) acids.12,6 Significant amounts of carotenoids as well as alpha‐linolenic fatty acid (38%), linoleic (36%), oleic (13%), and palmitic (7%) acids are present in sea buckthorn seed oil.6

Polysaccharides

In an expansive review on the pharmacological activities of sea buckthorn polysaccharides, Teng and colleagues reported in April 2024 that 20 diverse polysaccharides have been culled from sea buckthorn and exhibited various healthy activities, including antioxidant, anti-fatigue, anti-inflammatory, anti-obesity, anti-tumor, hepatoprotective, hypoglycemic, and immunoregulation, and regulation of intestinal flora activities.1

Proanthocyanidins and Anti-Aging

In 2023, Liu and colleagues investigated the anti–skin aging impact of sea buckthorn proanthocyanidins in D-galactose-induced aging in mice given the known free radical scavenging activity of these compounds. They found the proanthocyanidins mitigated D-galactose-induced aging and can augment the total antioxidant capacity of the body. Sea buckthorn proanthocyanidins can further attenuate the effects of skin aging by regulating the TGF-beta1/Smads pathway and MMPs/TIMP system, thus amplifying collagen I and tropoelastin content.13

A year earlier, many of the same investigators assessed the possible protective activity of sea buckthorn proanthocyanidins against cutaneous aging engendered by oxidative stress from hydrogen peroxide. The compounds amplified superoxide dismutase and glutathione antioxidant functions. The extracts also fostered collagen I production in aging human skin fibroblasts via the TGF-beta1/Smads pathway and hindered collagen I degradation by regulating the MMPs/TIMPs system, which maintained extracellular matrix integrity. Senescent cell migration was also promoted with 100 mcg/mL of sea buckthorn proanthocyanidins. The researchers concluded that this sets the stage for investigating how sea buckthorn proanthocyanidins can be incorporated in cosmetic formulations.14 In a separate study, Liu and colleagues demonstrated that sea buckthorn proanthocyanidins can attenuate oxidative damage and protect mitochondrial function.9

Acne and Barrier Functions

The extracts of H rhamnoides and Cassia fistula in a combined formulation were found to be effective in lowering skin sebum content in humans with grade I and grade II acne vulgaris in a 2014 single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, split-face study with two groups of 25 patients each (aged 18-37 years).15 Khan and colleagues have also reported that a sea buckthorn oil-in-water emulsion improved barrier function in human skin as tested by a tewameter and corneometer (noninvasive probes) in 13 healthy males with a mean age of 27 ± 4.8 years.16

Anti-Aging, Antioxidant, Antibacterial, Skin-Whitening Activity

Zaman and colleagues reported in 2011 that results from an in vivo study of the effects of a sea buckthorn fruit extract topical cream on stratum corneum water content and transepidermal water loss indicated that the formulation enhanced cell surface integrin expression thus facilitating collagen contraction.17

In 2012, Khan and colleagues reported amelioration in skin elasticity, thus achieving an anti-aging result, from the use of a water-in-oil–based hydroalcoholic cream loaded with fruit extract of H rhamnoides, as measured with a Cutometer.18 The previous year, some of the same researchers reported that the antioxidants and flavonoids found in a topical sea buckthorn formulation could decrease cutaneous melanin and erythema levels.

More recently, Gęgotek and colleagues found that sea buckthorn seed oil prevented redox balance and lipid metabolism disturbances in skin fibroblasts and keratinocytes caused by UVA or UVB. They suggested that such findings point to the potential of this natural agent to confer anti-inflammatory properties and photoprotection to the skin.19

In 2020, Ivanišová and colleagues investigated the antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of H rhamnoides 100% oil, 100% juice, dry berries, and tea (dry berries, leaves, and twigs). They found that all of the studied sea buckthorn products displayed high antioxidant activity (identified through DPPH radical scavenging and molybdenum reducing antioxidant power tests). Sea buckthorn juice contained the highest total content of polyphenols, flavonoids, and carotenoids. All of the tested products also exhibited substantial antibacterial activity against the tested microbes.20

Burns and Wound Healing

In a preclinical study of the effects of sea buckthorn leaf extracts on wound healing in albino rats using an excision-punch wound model in 2005, Gupta and colleagues found that twice daily topical application of the aqueous leaf extract fostered wound healing. This was indicated by higher hydroxyproline and protein levels, a diminished wound area, and lower lipid peroxide levels. The investigators suggested that sea buckthorn may facilitate wound healing at least in part because of elevated antioxidant activity in the granulation tissue.3

A year later, Wang and colleagues reported on observations of using H rhamnoides oil, a traditional Chinese herbal medicine derived from sea buckthorn fruit, as a burn treatment. In the study, 151 burn patients received an H rhamnoides oil dressing (changed every other day until wound healing) that was covered with a disinfecting dressing. The dressing reduced swelling and effusion, and alleviated pain, with patients receiving the sea buckthorn dressing experiencing greater apparent exudation reduction, pain reduction, and more rapid epithelial cell growth and wound healing than controls (treated only with Vaseline gauze). The difference between the two groups was statistically significant.21

Conclusion

Sea buckthorn has been used for hundreds if not thousands of years in traditional medical applications, including for dermatologic purposes. Emerging data appear to support the use of this dynamic plant for consideration in dermatologic applications. As is often the case, much more work is necessary in the form of randomized controlled trials to determine the effectiveness of sea buckthorn formulations as well as the most appropriate avenues of research or uses for dermatologic application of this traditionally used botanical agent.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur in Miami. She founded the division of cosmetic dermatology at the University of Miami in 1997. The third edition of her bestselling textbook, “Cosmetic Dermatology,” was published in 2022. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Johnson & Johnson, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions, a SaaS company used to generate skin care routines in office and as a e-commerce solution. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Teng H et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024 Apr 24;324:117809. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2024.117809.

2. Wang Z et al. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024 Apr;263(Pt 1):130206. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130206.

3. Gupta A et al. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2005 Jun;4(2):88-92. doi: 10.1177/1534734605277401.

4. Pundir S et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021 Feb 10;266:113434. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113434.

5. Ma QG et al. J Agric Food Chem. 2023 Mar 29;71(12):4769-4788. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c06916.

6. Poljšak N et al. Phytother Res. 2020 Feb;34(2):254-269. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6524. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6524.

7. Upadhyay NK et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:659705. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep189.

8. Suryakumar G, Gupta A. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011 Nov 18;138(2):268-78. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.09.024.

9. Liu K et al. Front Pharmacol. 2022 Jul 8;13:914146. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.914146.

10. Akhtar N et al. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2010 Jan;2(1):13-7. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.62698.

11. Ren R et al. RSC Adv. 2020 Dec 17;10(73):44654-44671. doi: 10.1039/d0ra06488b.

12. Ito H et al. Burns. 2014 May;40(3):511-9. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2013.08.011.

13. Liu X et al. Food Sci Nutr. 2023 Dec 7;12(2):1082-1094. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.3823.

14. Liu X at al. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022 Sep 25;11(10):1900. doi: 10.3390/antiox11101900.

15. Khan BA, Akhtar N. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014 Aug;31(4):229-234. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2014.40934.

16. Khan BA, Akhtar N. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2014 Nov;27(6):1919-22.

17. Khan AB et al. African J Pharm Pharmacol. 2011 Aug;5(8):1092-5.

18. Khan BA, Akhtar N, Braga VA. Trop J Pharm Res. 2012;11(6):955-62.

19. Gęgotek A et al. Antioxidants (Basel). 2018 Aug 23;7(9):110. doi: 10.3390/antiox7090110.

20. Ivanišová E et al. Acta Sci Pol Technol Aliment. 2020 Apr-Jun;19(2):195-205. doi: 10.17306/J.AFS.0809.

21. Wang ZY, Luo XL, He CP. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2006 Jan;26(1):124-5.

A member of the Elaeagnaceae family, Hippophae rhamnoides, better known as sea buckthorn, is a high-altitude wild shrub endemic to Europe and Asia with edible fruits and a lengthy record of use in traditional Chinese medicine.1-6 Used as a health supplement and consumed in the diet throughout the world,5 sea buckthorn berries, seeds, and leaves have been used in traditional medicine to treat burns/injuries, edema, hypertension, inflammation, skin grafts, ulcers, and wounds.4,7

This hardy plant is associated with a wide range of biologic activities, including anti-atherogenic, anti-atopic dermatitis, antibacterial, anticancer, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-psoriasis, anti-sebum, anti-stress, anti-tumor, cytoprotective, hepatoprotective, immunomodulatory, neuroprotective, radioprotective, and tissue regenerative functions.4,5,8-11

Key Constituents

Functional constituents identified in sea buckthorn include alkaloids, carotenoids, flavonoids, lignans, organic acids, phenolic acids, proanthocyanidins, polyunsaturated acids (including omega-3, -6, -7, and -9), steroids, tannins, terpenoids, and volatile oils, as well as nutritional compounds such as minerals, proteins, and vitamins.4,5,11 Sea buckthorn pericarp oil contains copious amounts of saturated palmitic acid (29%-36%) and omega-7 unsaturated palmitoleic acid (36%-48%), which fosters cutaneous and mucosal epithelialization, as well as linoleic (10%-12%) and oleic (4%-6%) acids.12,6 Significant amounts of carotenoids as well as alpha‐linolenic fatty acid (38%), linoleic (36%), oleic (13%), and palmitic (7%) acids are present in sea buckthorn seed oil.6

Polysaccharides

In an expansive review on the pharmacological activities of sea buckthorn polysaccharides, Teng and colleagues reported in April 2024 that 20 diverse polysaccharides have been culled from sea buckthorn and exhibited various healthy activities, including antioxidant, anti-fatigue, anti-inflammatory, anti-obesity, anti-tumor, hepatoprotective, hypoglycemic, and immunoregulation, and regulation of intestinal flora activities.1

Proanthocyanidins and Anti-Aging

In 2023, Liu and colleagues investigated the anti–skin aging impact of sea buckthorn proanthocyanidins in D-galactose-induced aging in mice given the known free radical scavenging activity of these compounds. They found the proanthocyanidins mitigated D-galactose-induced aging and can augment the total antioxidant capacity of the body. Sea buckthorn proanthocyanidins can further attenuate the effects of skin aging by regulating the TGF-beta1/Smads pathway and MMPs/TIMP system, thus amplifying collagen I and tropoelastin content.13

A year earlier, many of the same investigators assessed the possible protective activity of sea buckthorn proanthocyanidins against cutaneous aging engendered by oxidative stress from hydrogen peroxide. The compounds amplified superoxide dismutase and glutathione antioxidant functions. The extracts also fostered collagen I production in aging human skin fibroblasts via the TGF-beta1/Smads pathway and hindered collagen I degradation by regulating the MMPs/TIMPs system, which maintained extracellular matrix integrity. Senescent cell migration was also promoted with 100 mcg/mL of sea buckthorn proanthocyanidins. The researchers concluded that this sets the stage for investigating how sea buckthorn proanthocyanidins can be incorporated in cosmetic formulations.14 In a separate study, Liu and colleagues demonstrated that sea buckthorn proanthocyanidins can attenuate oxidative damage and protect mitochondrial function.9

Acne and Barrier Functions

The extracts of H rhamnoides and Cassia fistula in a combined formulation were found to be effective in lowering skin sebum content in humans with grade I and grade II acne vulgaris in a 2014 single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, split-face study with two groups of 25 patients each (aged 18-37 years).15 Khan and colleagues have also reported that a sea buckthorn oil-in-water emulsion improved barrier function in human skin as tested by a tewameter and corneometer (noninvasive probes) in 13 healthy males with a mean age of 27 ± 4.8 years.16

Anti-Aging, Antioxidant, Antibacterial, Skin-Whitening Activity

Zaman and colleagues reported in 2011 that results from an in vivo study of the effects of a sea buckthorn fruit extract topical cream on stratum corneum water content and transepidermal water loss indicated that the formulation enhanced cell surface integrin expression thus facilitating collagen contraction.17

In 2012, Khan and colleagues reported amelioration in skin elasticity, thus achieving an anti-aging result, from the use of a water-in-oil–based hydroalcoholic cream loaded with fruit extract of H rhamnoides, as measured with a Cutometer.18 The previous year, some of the same researchers reported that the antioxidants and flavonoids found in a topical sea buckthorn formulation could decrease cutaneous melanin and erythema levels.

More recently, Gęgotek and colleagues found that sea buckthorn seed oil prevented redox balance and lipid metabolism disturbances in skin fibroblasts and keratinocytes caused by UVA or UVB. They suggested that such findings point to the potential of this natural agent to confer anti-inflammatory properties and photoprotection to the skin.19

In 2020, Ivanišová and colleagues investigated the antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of H rhamnoides 100% oil, 100% juice, dry berries, and tea (dry berries, leaves, and twigs). They found that all of the studied sea buckthorn products displayed high antioxidant activity (identified through DPPH radical scavenging and molybdenum reducing antioxidant power tests). Sea buckthorn juice contained the highest total content of polyphenols, flavonoids, and carotenoids. All of the tested products also exhibited substantial antibacterial activity against the tested microbes.20

Burns and Wound Healing

In a preclinical study of the effects of sea buckthorn leaf extracts on wound healing in albino rats using an excision-punch wound model in 2005, Gupta and colleagues found that twice daily topical application of the aqueous leaf extract fostered wound healing. This was indicated by higher hydroxyproline and protein levels, a diminished wound area, and lower lipid peroxide levels. The investigators suggested that sea buckthorn may facilitate wound healing at least in part because of elevated antioxidant activity in the granulation tissue.3

A year later, Wang and colleagues reported on observations of using H rhamnoides oil, a traditional Chinese herbal medicine derived from sea buckthorn fruit, as a burn treatment. In the study, 151 burn patients received an H rhamnoides oil dressing (changed every other day until wound healing) that was covered with a disinfecting dressing. The dressing reduced swelling and effusion, and alleviated pain, with patients receiving the sea buckthorn dressing experiencing greater apparent exudation reduction, pain reduction, and more rapid epithelial cell growth and wound healing than controls (treated only with Vaseline gauze). The difference between the two groups was statistically significant.21

Conclusion

Sea buckthorn has been used for hundreds if not thousands of years in traditional medical applications, including for dermatologic purposes. Emerging data appear to support the use of this dynamic plant for consideration in dermatologic applications. As is often the case, much more work is necessary in the form of randomized controlled trials to determine the effectiveness of sea buckthorn formulations as well as the most appropriate avenues of research or uses for dermatologic application of this traditionally used botanical agent.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur in Miami. She founded the division of cosmetic dermatology at the University of Miami in 1997. The third edition of her bestselling textbook, “Cosmetic Dermatology,” was published in 2022. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Johnson & Johnson, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions, a SaaS company used to generate skin care routines in office and as a e-commerce solution. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Teng H et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024 Apr 24;324:117809. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2024.117809.

2. Wang Z et al. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024 Apr;263(Pt 1):130206. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130206.

3. Gupta A et al. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2005 Jun;4(2):88-92. doi: 10.1177/1534734605277401.

4. Pundir S et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021 Feb 10;266:113434. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113434.

5. Ma QG et al. J Agric Food Chem. 2023 Mar 29;71(12):4769-4788. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c06916.

6. Poljšak N et al. Phytother Res. 2020 Feb;34(2):254-269. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6524. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6524.

7. Upadhyay NK et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:659705. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep189.

8. Suryakumar G, Gupta A. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011 Nov 18;138(2):268-78. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.09.024.

9. Liu K et al. Front Pharmacol. 2022 Jul 8;13:914146. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.914146.

10. Akhtar N et al. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2010 Jan;2(1):13-7. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.62698.

11. Ren R et al. RSC Adv. 2020 Dec 17;10(73):44654-44671. doi: 10.1039/d0ra06488b.

12. Ito H et al. Burns. 2014 May;40(3):511-9. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2013.08.011.

13. Liu X et al. Food Sci Nutr. 2023 Dec 7;12(2):1082-1094. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.3823.

14. Liu X at al. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022 Sep 25;11(10):1900. doi: 10.3390/antiox11101900.

15. Khan BA, Akhtar N. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014 Aug;31(4):229-234. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2014.40934.

16. Khan BA, Akhtar N. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2014 Nov;27(6):1919-22.

17. Khan AB et al. African J Pharm Pharmacol. 2011 Aug;5(8):1092-5.

18. Khan BA, Akhtar N, Braga VA. Trop J Pharm Res. 2012;11(6):955-62.

19. Gęgotek A et al. Antioxidants (Basel). 2018 Aug 23;7(9):110. doi: 10.3390/antiox7090110.

20. Ivanišová E et al. Acta Sci Pol Technol Aliment. 2020 Apr-Jun;19(2):195-205. doi: 10.17306/J.AFS.0809.

21. Wang ZY, Luo XL, He CP. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2006 Jan;26(1):124-5.

A member of the Elaeagnaceae family, Hippophae rhamnoides, better known as sea buckthorn, is a high-altitude wild shrub endemic to Europe and Asia with edible fruits and a lengthy record of use in traditional Chinese medicine.1-6 Used as a health supplement and consumed in the diet throughout the world,5 sea buckthorn berries, seeds, and leaves have been used in traditional medicine to treat burns/injuries, edema, hypertension, inflammation, skin grafts, ulcers, and wounds.4,7

This hardy plant is associated with a wide range of biologic activities, including anti-atherogenic, anti-atopic dermatitis, antibacterial, anticancer, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-psoriasis, anti-sebum, anti-stress, anti-tumor, cytoprotective, hepatoprotective, immunomodulatory, neuroprotective, radioprotective, and tissue regenerative functions.4,5,8-11

Key Constituents

Functional constituents identified in sea buckthorn include alkaloids, carotenoids, flavonoids, lignans, organic acids, phenolic acids, proanthocyanidins, polyunsaturated acids (including omega-3, -6, -7, and -9), steroids, tannins, terpenoids, and volatile oils, as well as nutritional compounds such as minerals, proteins, and vitamins.4,5,11 Sea buckthorn pericarp oil contains copious amounts of saturated palmitic acid (29%-36%) and omega-7 unsaturated palmitoleic acid (36%-48%), which fosters cutaneous and mucosal epithelialization, as well as linoleic (10%-12%) and oleic (4%-6%) acids.12,6 Significant amounts of carotenoids as well as alpha‐linolenic fatty acid (38%), linoleic (36%), oleic (13%), and palmitic (7%) acids are present in sea buckthorn seed oil.6

Polysaccharides

In an expansive review on the pharmacological activities of sea buckthorn polysaccharides, Teng and colleagues reported in April 2024 that 20 diverse polysaccharides have been culled from sea buckthorn and exhibited various healthy activities, including antioxidant, anti-fatigue, anti-inflammatory, anti-obesity, anti-tumor, hepatoprotective, hypoglycemic, and immunoregulation, and regulation of intestinal flora activities.1

Proanthocyanidins and Anti-Aging

In 2023, Liu and colleagues investigated the anti–skin aging impact of sea buckthorn proanthocyanidins in D-galactose-induced aging in mice given the known free radical scavenging activity of these compounds. They found the proanthocyanidins mitigated D-galactose-induced aging and can augment the total antioxidant capacity of the body. Sea buckthorn proanthocyanidins can further attenuate the effects of skin aging by regulating the TGF-beta1/Smads pathway and MMPs/TIMP system, thus amplifying collagen I and tropoelastin content.13

A year earlier, many of the same investigators assessed the possible protective activity of sea buckthorn proanthocyanidins against cutaneous aging engendered by oxidative stress from hydrogen peroxide. The compounds amplified superoxide dismutase and glutathione antioxidant functions. The extracts also fostered collagen I production in aging human skin fibroblasts via the TGF-beta1/Smads pathway and hindered collagen I degradation by regulating the MMPs/TIMPs system, which maintained extracellular matrix integrity. Senescent cell migration was also promoted with 100 mcg/mL of sea buckthorn proanthocyanidins. The researchers concluded that this sets the stage for investigating how sea buckthorn proanthocyanidins can be incorporated in cosmetic formulations.14 In a separate study, Liu and colleagues demonstrated that sea buckthorn proanthocyanidins can attenuate oxidative damage and protect mitochondrial function.9

Acne and Barrier Functions

The extracts of H rhamnoides and Cassia fistula in a combined formulation were found to be effective in lowering skin sebum content in humans with grade I and grade II acne vulgaris in a 2014 single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, split-face study with two groups of 25 patients each (aged 18-37 years).15 Khan and colleagues have also reported that a sea buckthorn oil-in-water emulsion improved barrier function in human skin as tested by a tewameter and corneometer (noninvasive probes) in 13 healthy males with a mean age of 27 ± 4.8 years.16

Anti-Aging, Antioxidant, Antibacterial, Skin-Whitening Activity

Zaman and colleagues reported in 2011 that results from an in vivo study of the effects of a sea buckthorn fruit extract topical cream on stratum corneum water content and transepidermal water loss indicated that the formulation enhanced cell surface integrin expression thus facilitating collagen contraction.17

In 2012, Khan and colleagues reported amelioration in skin elasticity, thus achieving an anti-aging result, from the use of a water-in-oil–based hydroalcoholic cream loaded with fruit extract of H rhamnoides, as measured with a Cutometer.18 The previous year, some of the same researchers reported that the antioxidants and flavonoids found in a topical sea buckthorn formulation could decrease cutaneous melanin and erythema levels.

More recently, Gęgotek and colleagues found that sea buckthorn seed oil prevented redox balance and lipid metabolism disturbances in skin fibroblasts and keratinocytes caused by UVA or UVB. They suggested that such findings point to the potential of this natural agent to confer anti-inflammatory properties and photoprotection to the skin.19

In 2020, Ivanišová and colleagues investigated the antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of H rhamnoides 100% oil, 100% juice, dry berries, and tea (dry berries, leaves, and twigs). They found that all of the studied sea buckthorn products displayed high antioxidant activity (identified through DPPH radical scavenging and molybdenum reducing antioxidant power tests). Sea buckthorn juice contained the highest total content of polyphenols, flavonoids, and carotenoids. All of the tested products also exhibited substantial antibacterial activity against the tested microbes.20

Burns and Wound Healing

In a preclinical study of the effects of sea buckthorn leaf extracts on wound healing in albino rats using an excision-punch wound model in 2005, Gupta and colleagues found that twice daily topical application of the aqueous leaf extract fostered wound healing. This was indicated by higher hydroxyproline and protein levels, a diminished wound area, and lower lipid peroxide levels. The investigators suggested that sea buckthorn may facilitate wound healing at least in part because of elevated antioxidant activity in the granulation tissue.3

A year later, Wang and colleagues reported on observations of using H rhamnoides oil, a traditional Chinese herbal medicine derived from sea buckthorn fruit, as a burn treatment. In the study, 151 burn patients received an H rhamnoides oil dressing (changed every other day until wound healing) that was covered with a disinfecting dressing. The dressing reduced swelling and effusion, and alleviated pain, with patients receiving the sea buckthorn dressing experiencing greater apparent exudation reduction, pain reduction, and more rapid epithelial cell growth and wound healing than controls (treated only with Vaseline gauze). The difference between the two groups was statistically significant.21

Conclusion

Sea buckthorn has been used for hundreds if not thousands of years in traditional medical applications, including for dermatologic purposes. Emerging data appear to support the use of this dynamic plant for consideration in dermatologic applications. As is often the case, much more work is necessary in the form of randomized controlled trials to determine the effectiveness of sea buckthorn formulations as well as the most appropriate avenues of research or uses for dermatologic application of this traditionally used botanical agent.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur in Miami. She founded the division of cosmetic dermatology at the University of Miami in 1997. The third edition of her bestselling textbook, “Cosmetic Dermatology,” was published in 2022. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Johnson & Johnson, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions, a SaaS company used to generate skin care routines in office and as a e-commerce solution. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Teng H et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024 Apr 24;324:117809. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2024.117809.

2. Wang Z et al. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024 Apr;263(Pt 1):130206. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130206.

3. Gupta A et al. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2005 Jun;4(2):88-92. doi: 10.1177/1534734605277401.

4. Pundir S et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021 Feb 10;266:113434. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113434.

5. Ma QG et al. J Agric Food Chem. 2023 Mar 29;71(12):4769-4788. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c06916.

6. Poljšak N et al. Phytother Res. 2020 Feb;34(2):254-269. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6524. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6524.

7. Upadhyay NK et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:659705. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep189.

8. Suryakumar G, Gupta A. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011 Nov 18;138(2):268-78. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.09.024.

9. Liu K et al. Front Pharmacol. 2022 Jul 8;13:914146. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.914146.

10. Akhtar N et al. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2010 Jan;2(1):13-7. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.62698.

11. Ren R et al. RSC Adv. 2020 Dec 17;10(73):44654-44671. doi: 10.1039/d0ra06488b.

12. Ito H et al. Burns. 2014 May;40(3):511-9. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2013.08.011.

13. Liu X et al. Food Sci Nutr. 2023 Dec 7;12(2):1082-1094. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.3823.

14. Liu X at al. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022 Sep 25;11(10):1900. doi: 10.3390/antiox11101900.

15. Khan BA, Akhtar N. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014 Aug;31(4):229-234. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2014.40934.

16. Khan BA, Akhtar N. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2014 Nov;27(6):1919-22.

17. Khan AB et al. African J Pharm Pharmacol. 2011 Aug;5(8):1092-5.

18. Khan BA, Akhtar N, Braga VA. Trop J Pharm Res. 2012;11(6):955-62.

19. Gęgotek A et al. Antioxidants (Basel). 2018 Aug 23;7(9):110. doi: 10.3390/antiox7090110.

20. Ivanišová E et al. Acta Sci Pol Technol Aliment. 2020 Apr-Jun;19(2):195-205. doi: 10.17306/J.AFS.0809.

21. Wang ZY, Luo XL, He CP. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2006 Jan;26(1):124-5.

Eruption of Multiple Linear Hyperpigmented Plaques

THE DIAGNOSIS: Chemotherapy-Induced Flagellate Dermatitis

Based on the clinical presentation and temporal relation with chemotherapy, a diagnosis of bleomycininduced flagellate dermatitis (FD) was made, as bleomycin is the only chemotherapeutic agent from this regimen that has been linked with FD.1,2 Laboratory findings revealed eosinophilia, further supporting a druginduced dermatitis. The patient was treated with oral steroids and diphenhydramine to alleviate itching and discomfort. The chemotherapy was temporarily discontinued until symptomatic improvement was observed within 2 to 3 days.

Flagellate dermatitis is characterized by unique erythematous, linear, intermingled streaks of adjoining firm papules—often preceded by a prodrome of global pruritus—that eventually become hyperpigmented as the erythema subsides. The clinical manifestation of FD can be idiopathic; true/mechanical (dermatitis artefacta, abuse, sadomasochism); chemotherapy induced (peplomycin, trastuzumab, cisplatin, docetaxel, bendamustine); toxin induced (shiitake mushroom, cnidarian stings, Paederus insects); related to rheumatologic diseases (dermatomyositis, adult-onset Still disease), dermatographism, phytophotodermatitis, or poison ivy dermatitis; or induced by chikungunya fever.1

The term flagellate originates from the Latin word flagellum, which pertains to the distinctive whiplike pattern. It was first described by Moulin et al3 in 1970 in reference to bleomycin-induced linear hyperpigmentation. Bleomycin, a glycopeptide antibiotic derived from Streptomyces verticillus, is used to treat Hodgkin lymphoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and germ cell tumors. The worldwide incidence of bleomycin-induced FD is 8% to 22% and commonly is associated with a cumulative dose greater than 100 U.2 Clinical presentation is variable in terms of onset, distribution, and morphology of the eruption and could be independent of dose, route of administration, or type of malignancy being treated. The flagellate rash commonly involves the trunk, arms, and legs; can develop within hours to 6 months of starting bleomycin therapy; often is preceded by generalized itching; and eventually heals with hyperpigmentation.

Possible mechanisms of bleomycin-induced FD include localized melanogenesis, inflammatory pigmentary incontinence, alterations to normal pigmentation patterns, cytotoxic effects of the drug itself, minor trauma/ scratching leading to increased blood flow and causing local accumulation of bleomycin, heat recall, and reduced epidermal turnover leading to extended interaction between keratinocytes and melanocytes.2 Heat exposure can act as a trigger for bleomycin-induced skin rash recall even months after the treatment is stopped.

Apart from discontinuing the drug, there is no specific treatment available for bleomycin-induced FD. The primary objective of treatment is to alleviate pruritus, which often involves the use of topical or systemic corticosteroids and oral antihistamines. The duration of treatment depends on the patient’s clinical response. Once treatment is discontinued, FD typically resolves within 6 to 8 months. However, there can be a permanent postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in the affected area.4 Although there is a concern for increased mortality after postponement of chemotherapy,5 the decision to proceed with or discontinue the chemotherapy regimen necessitates a comprehensive interdisciplinary discussion and a meticulous assessment of the risks and benefits that is customized to each individual patient. Flagellate dermatitis can reoccur with bleomycin re-exposure; a combined approach of proactive topical and systemic steroid treatment seems to diminish the likelihood of FD recurrence.5

Our case underscores the importance of recognizing, detecting, and managing FD promptly in individuals undergoing bleomycin-based chemotherapy. Medical professionals should familiarize themselves with this distinct adverse effect linked to bleomycin, enabling prompt discontinuation if necessary, and educate patients about the condition’s typically temporary nature, thereby alleviating their concerns.

- Bhushan P, Manjul P, Baliyan V. Flagellate dermatoses. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:149-152.

- Ziemer M, Goetze S, Juhasz K, et al. Flagellate dermatitis as a bleomycinspecific adverse effect of cytostatic therapy: a clinical-histopathologic correlation. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:68-76. doi:10.2165/11537080-000000000-00000

- Moulin G, Fière B, Beyvin A. Cutaneous pigmentation caused by bleomycin. Article in French. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1970;77:293-296.

- Biswas A, Chaudhari PB, Sharma P, et al. Bleomycin induced flagellate erythema: revisiting a unique complication. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9:500-503. doi:10.4103/0973-1482.119358

- Hanna TP, King WD, Thibodeau S, et al. Mortality due to cancer treatment delay: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;371:m4087. doi:10.1136/bmj.m4087

THE DIAGNOSIS: Chemotherapy-Induced Flagellate Dermatitis

Based on the clinical presentation and temporal relation with chemotherapy, a diagnosis of bleomycininduced flagellate dermatitis (FD) was made, as bleomycin is the only chemotherapeutic agent from this regimen that has been linked with FD.1,2 Laboratory findings revealed eosinophilia, further supporting a druginduced dermatitis. The patient was treated with oral steroids and diphenhydramine to alleviate itching and discomfort. The chemotherapy was temporarily discontinued until symptomatic improvement was observed within 2 to 3 days.

Flagellate dermatitis is characterized by unique erythematous, linear, intermingled streaks of adjoining firm papules—often preceded by a prodrome of global pruritus—that eventually become hyperpigmented as the erythema subsides. The clinical manifestation of FD can be idiopathic; true/mechanical (dermatitis artefacta, abuse, sadomasochism); chemotherapy induced (peplomycin, trastuzumab, cisplatin, docetaxel, bendamustine); toxin induced (shiitake mushroom, cnidarian stings, Paederus insects); related to rheumatologic diseases (dermatomyositis, adult-onset Still disease), dermatographism, phytophotodermatitis, or poison ivy dermatitis; or induced by chikungunya fever.1

The term flagellate originates from the Latin word flagellum, which pertains to the distinctive whiplike pattern. It was first described by Moulin et al3 in 1970 in reference to bleomycin-induced linear hyperpigmentation. Bleomycin, a glycopeptide antibiotic derived from Streptomyces verticillus, is used to treat Hodgkin lymphoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and germ cell tumors. The worldwide incidence of bleomycin-induced FD is 8% to 22% and commonly is associated with a cumulative dose greater than 100 U.2 Clinical presentation is variable in terms of onset, distribution, and morphology of the eruption and could be independent of dose, route of administration, or type of malignancy being treated. The flagellate rash commonly involves the trunk, arms, and legs; can develop within hours to 6 months of starting bleomycin therapy; often is preceded by generalized itching; and eventually heals with hyperpigmentation.

Possible mechanisms of bleomycin-induced FD include localized melanogenesis, inflammatory pigmentary incontinence, alterations to normal pigmentation patterns, cytotoxic effects of the drug itself, minor trauma/ scratching leading to increased blood flow and causing local accumulation of bleomycin, heat recall, and reduced epidermal turnover leading to extended interaction between keratinocytes and melanocytes.2 Heat exposure can act as a trigger for bleomycin-induced skin rash recall even months after the treatment is stopped.

Apart from discontinuing the drug, there is no specific treatment available for bleomycin-induced FD. The primary objective of treatment is to alleviate pruritus, which often involves the use of topical or systemic corticosteroids and oral antihistamines. The duration of treatment depends on the patient’s clinical response. Once treatment is discontinued, FD typically resolves within 6 to 8 months. However, there can be a permanent postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in the affected area.4 Although there is a concern for increased mortality after postponement of chemotherapy,5 the decision to proceed with or discontinue the chemotherapy regimen necessitates a comprehensive interdisciplinary discussion and a meticulous assessment of the risks and benefits that is customized to each individual patient. Flagellate dermatitis can reoccur with bleomycin re-exposure; a combined approach of proactive topical and systemic steroid treatment seems to diminish the likelihood of FD recurrence.5

Our case underscores the importance of recognizing, detecting, and managing FD promptly in individuals undergoing bleomycin-based chemotherapy. Medical professionals should familiarize themselves with this distinct adverse effect linked to bleomycin, enabling prompt discontinuation if necessary, and educate patients about the condition’s typically temporary nature, thereby alleviating their concerns.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Chemotherapy-Induced Flagellate Dermatitis

Based on the clinical presentation and temporal relation with chemotherapy, a diagnosis of bleomycininduced flagellate dermatitis (FD) was made, as bleomycin is the only chemotherapeutic agent from this regimen that has been linked with FD.1,2 Laboratory findings revealed eosinophilia, further supporting a druginduced dermatitis. The patient was treated with oral steroids and diphenhydramine to alleviate itching and discomfort. The chemotherapy was temporarily discontinued until symptomatic improvement was observed within 2 to 3 days.

Flagellate dermatitis is characterized by unique erythematous, linear, intermingled streaks of adjoining firm papules—often preceded by a prodrome of global pruritus—that eventually become hyperpigmented as the erythema subsides. The clinical manifestation of FD can be idiopathic; true/mechanical (dermatitis artefacta, abuse, sadomasochism); chemotherapy induced (peplomycin, trastuzumab, cisplatin, docetaxel, bendamustine); toxin induced (shiitake mushroom, cnidarian stings, Paederus insects); related to rheumatologic diseases (dermatomyositis, adult-onset Still disease), dermatographism, phytophotodermatitis, or poison ivy dermatitis; or induced by chikungunya fever.1

The term flagellate originates from the Latin word flagellum, which pertains to the distinctive whiplike pattern. It was first described by Moulin et al3 in 1970 in reference to bleomycin-induced linear hyperpigmentation. Bleomycin, a glycopeptide antibiotic derived from Streptomyces verticillus, is used to treat Hodgkin lymphoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and germ cell tumors. The worldwide incidence of bleomycin-induced FD is 8% to 22% and commonly is associated with a cumulative dose greater than 100 U.2 Clinical presentation is variable in terms of onset, distribution, and morphology of the eruption and could be independent of dose, route of administration, or type of malignancy being treated. The flagellate rash commonly involves the trunk, arms, and legs; can develop within hours to 6 months of starting bleomycin therapy; often is preceded by generalized itching; and eventually heals with hyperpigmentation.

Possible mechanisms of bleomycin-induced FD include localized melanogenesis, inflammatory pigmentary incontinence, alterations to normal pigmentation patterns, cytotoxic effects of the drug itself, minor trauma/ scratching leading to increased blood flow and causing local accumulation of bleomycin, heat recall, and reduced epidermal turnover leading to extended interaction between keratinocytes and melanocytes.2 Heat exposure can act as a trigger for bleomycin-induced skin rash recall even months after the treatment is stopped.

Apart from discontinuing the drug, there is no specific treatment available for bleomycin-induced FD. The primary objective of treatment is to alleviate pruritus, which often involves the use of topical or systemic corticosteroids and oral antihistamines. The duration of treatment depends on the patient’s clinical response. Once treatment is discontinued, FD typically resolves within 6 to 8 months. However, there can be a permanent postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in the affected area.4 Although there is a concern for increased mortality after postponement of chemotherapy,5 the decision to proceed with or discontinue the chemotherapy regimen necessitates a comprehensive interdisciplinary discussion and a meticulous assessment of the risks and benefits that is customized to each individual patient. Flagellate dermatitis can reoccur with bleomycin re-exposure; a combined approach of proactive topical and systemic steroid treatment seems to diminish the likelihood of FD recurrence.5

Our case underscores the importance of recognizing, detecting, and managing FD promptly in individuals undergoing bleomycin-based chemotherapy. Medical professionals should familiarize themselves with this distinct adverse effect linked to bleomycin, enabling prompt discontinuation if necessary, and educate patients about the condition’s typically temporary nature, thereby alleviating their concerns.

- Bhushan P, Manjul P, Baliyan V. Flagellate dermatoses. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:149-152.

- Ziemer M, Goetze S, Juhasz K, et al. Flagellate dermatitis as a bleomycinspecific adverse effect of cytostatic therapy: a clinical-histopathologic correlation. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:68-76. doi:10.2165/11537080-000000000-00000

- Moulin G, Fière B, Beyvin A. Cutaneous pigmentation caused by bleomycin. Article in French. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1970;77:293-296.

- Biswas A, Chaudhari PB, Sharma P, et al. Bleomycin induced flagellate erythema: revisiting a unique complication. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9:500-503. doi:10.4103/0973-1482.119358

- Hanna TP, King WD, Thibodeau S, et al. Mortality due to cancer treatment delay: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;371:m4087. doi:10.1136/bmj.m4087

- Bhushan P, Manjul P, Baliyan V. Flagellate dermatoses. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:149-152.

- Ziemer M, Goetze S, Juhasz K, et al. Flagellate dermatitis as a bleomycinspecific adverse effect of cytostatic therapy: a clinical-histopathologic correlation. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:68-76. doi:10.2165/11537080-000000000-00000

- Moulin G, Fière B, Beyvin A. Cutaneous pigmentation caused by bleomycin. Article in French. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1970;77:293-296.

- Biswas A, Chaudhari PB, Sharma P, et al. Bleomycin induced flagellate erythema: revisiting a unique complication. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9:500-503. doi:10.4103/0973-1482.119358

- Hanna TP, King WD, Thibodeau S, et al. Mortality due to cancer treatment delay: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;371:m4087. doi:10.1136/bmj.m4087

A 28-year-old man presented for evaluation of an intensely itchy rash of 5 days’ duration involving the face, trunk, arms, and legs. The patient recently had been diagnosed with classical Hodgkin lymphoma and was started on a biweekly chemotherapy regimen of adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine 3 weeks prior. He reported that a red, itchy, papular rash had developed on the hands 1 week after starting chemotherapy and improved with antihistamines. Symptoms of the current rash included night sweats, occasional fever, substantial unintentional weight loss, and fatigue. He had no history of urticaria, angioedema, anaphylaxis, or nail changes.

Physical examination revealed widespread, itchy, linear and curvilinear hyperpigmented plaques on the upper arms, shoulders, back (top), face, and thighs, as well as erythematous grouped papules on the bilateral palms (bottom). There was no mucosal or systemic involvement.

Rare Case of Photodistributed Hyperpigmentation Linked to Kratom Consumption

To the Editor:

Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) is an evergreen tree native to Southeast Asia.1 Its leaves contain psychoactive compounds including mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine, which exert dose-dependent effects on the central nervous system through opioid and monoaminergic receptors.2,3 At low doses (1–5 g), kratom elicits mild stimulant effects such as increased sociability, alertness, and talkativeness. At high doses (5–15 g), kratom has depressant effects that can provide relief from pain and opioid-withdrawal symptoms.3

Traditionally, kratom has been used in Southeast Asia for recreational and ceremonial purposes, to ease opioid-withdrawal symptoms, and to reduce fatigue from manual labor.4 In the 21st century, availability of kratom expanded to Europe, Australia, and the United States, largely facilitated by widespread dissemination of deceitful marketing and unregulated sales on the internet.1 Although large-scale epidemiologic studies evaluating kratom’s prevalence are scarce, available evidence indicates rising worldwide usage, with a notable increase in kratom-related poison center calls between 2011 and 2017 in the United States.5 In July 2023, kratom made headlines due to the death of a woman in Florida following use of the substance.6

A cross-sectional study revealed that in the United States, kratom typically is used by White individuals for self-treatment of anxiety, depression, pain, and opioid withdrawal.7 However, the potential for severe adverse effects and dependence on kratom can outweigh the benefits.6,8 Reported adverse effects of kratom include tachycardia, hypercholesteremia, liver injury, hallucinations, respiratory depression, seizure, coma, and death.9,10 We present a case of kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation.

A 63-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with diffuse tender, pruritic, hyperpigmented skin lesions that developed over the course of 1 year. The lesions were distributed on sun-exposed areas, including the face, neck, and forearms (Figure 1). The patient reported no other major symptoms, and his health was otherwise unremarkable. He had a medical history of psoriasiform and spongiotic dermatitis consistent with eczema, psoriasis, hypercholesteremia, and hyperlipidemia. The patient was not taking any medications at the time of presentation. He had a family history of plaque psoriasis in his father. Five years prior to the current presentation, the patient was treated with adalimumab for steroid-resistant psoriasis; however, despite initial improvement, he experienced recurrence of scaly erythematous plaques and had discontinued adalimumab the year prior to presentation.

When adalimumab was discontinued, the patient sought alternative treatment for the skin symptoms and began self-administering kratom in an attempt to alleviate associated physical discomfort. He ingested approximately 3 bottles of liquid kratom per day, with each bottle containing 180 mg of mitragynine and less than 8 mg of 7-hydroxymitragynine. Although not scientifically proven, kratom has been colloquially advertised to improve psoriasis.11 The patient reported no other medication use or allergies.

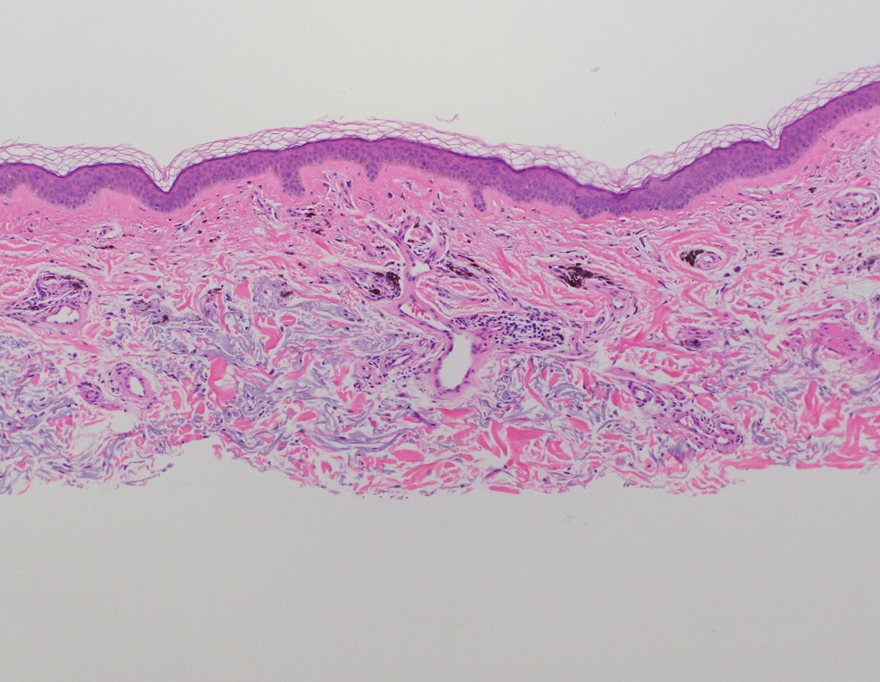

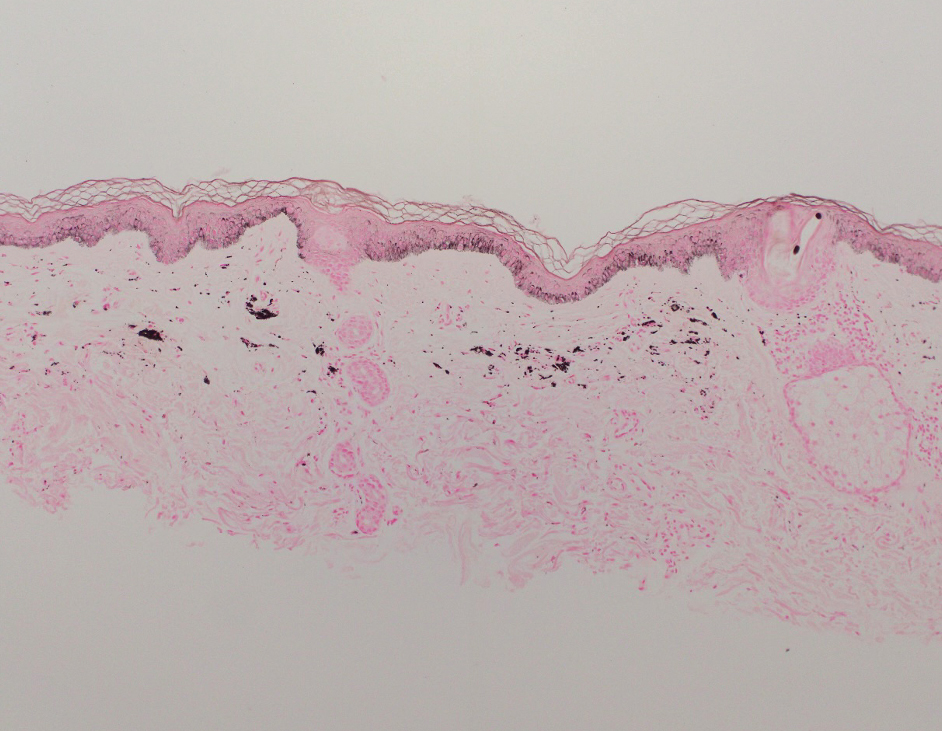

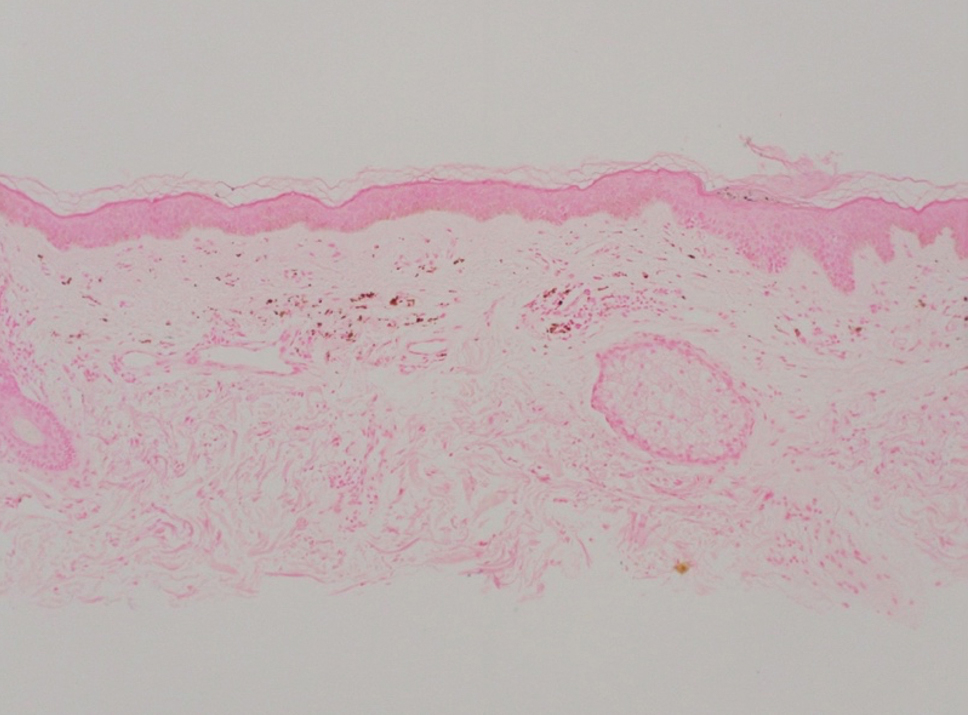

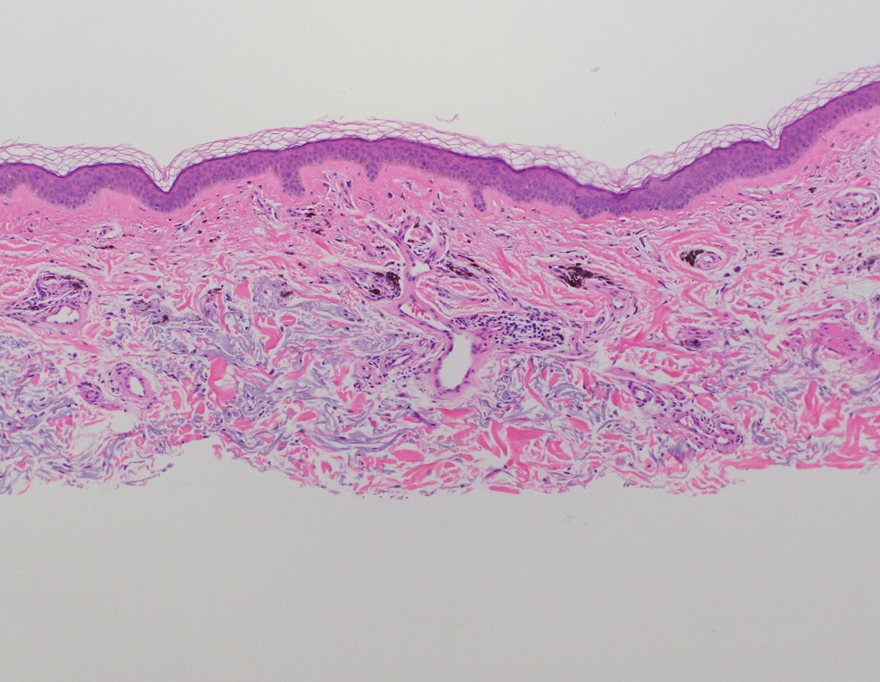

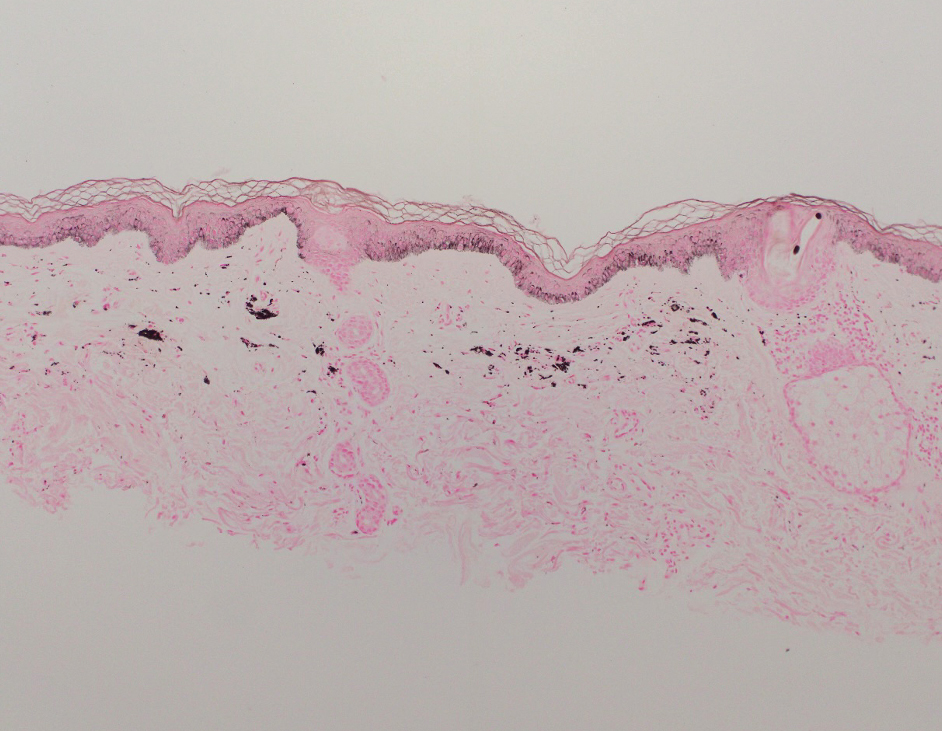

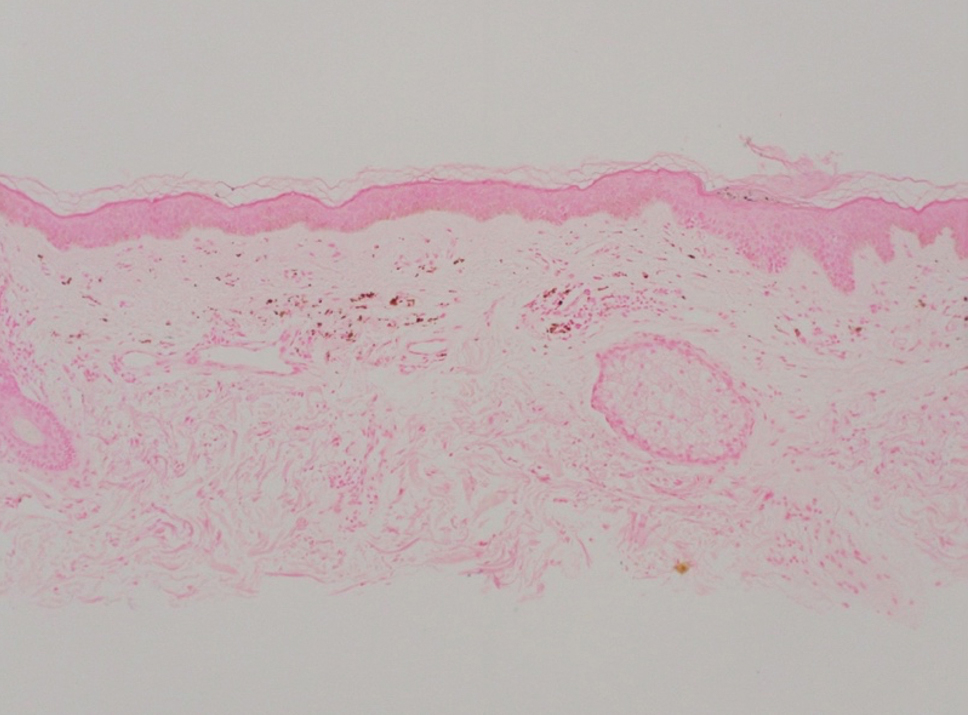

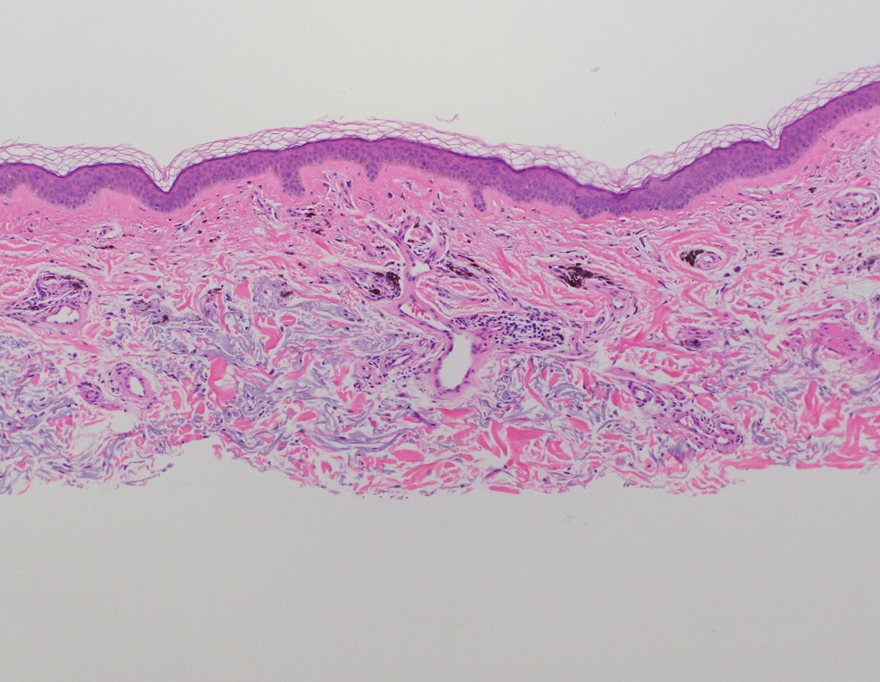

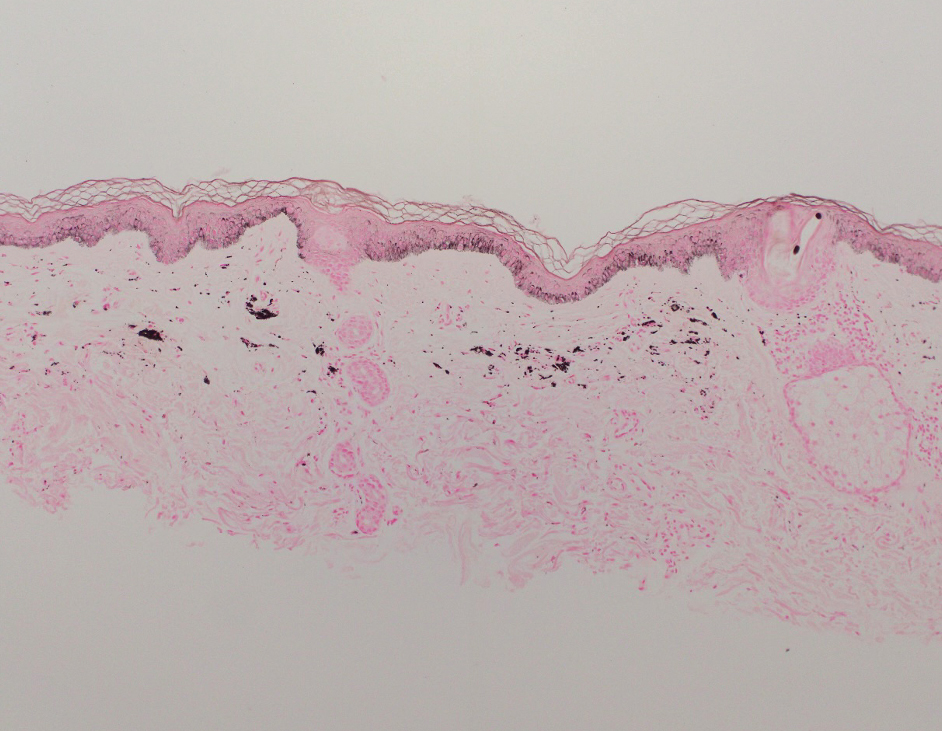

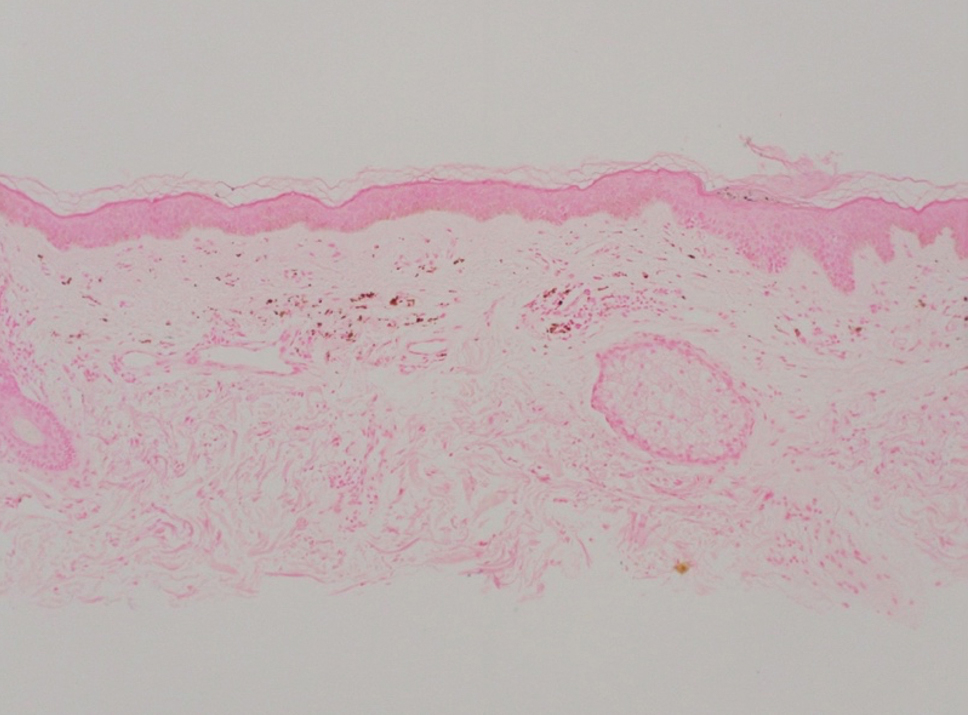

Shave biopsies of hyperpigmented lesions on the right side of the neck, ear, and forearm were performed. Histopathology revealed a sparse superficial, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltrate accompanied by a prominent number of melanophages in the superficial dermis (Figure 2). Special stains further confirmed that the pigment was melanin; the specimens stained positive with Fontana-Masson stain (Figure 3) and negative with an iron stain (Figure 4).

Adalimumab-induced hyperpigmentation was considered. A prior case of adalimumab-induced hyperpigmentation manifested on the face. Histopathology was consistent with a superficial, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltrate with melanophages in the dermis; however, hyperpigmentation was absent in the periorbital area, and affected areas faded 4 months after discontinuation of adalimumab.12 Our patient presented with hyperpigmentation 1 year after adalimumab cessation, and the hyperpigmented areas included the periorbital region. Because of the distinct temporal and clinical features, adalimumab-induced hyperpigmentation was eliminated from the differential diagnosis.

Based on the photodistributed pattern of hyperpigmentation, histopathology, and the temporal relationship between hyperpigmentation onset and kratom usage, a diagnosis of kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation was made. The patient was advised to discontinue kratom use and use sun protection to prevent further photodamage. The patient subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Kratom alkaloids bind all 3 opioid receptors—μOP, δOP, and κOPs—in a G-protein–biased manner with 7-hydroxymitragynine, the most pharmacologically active alkaloid, exhibiting a higher affinity for μ-opioid receptors.13,14 In human epidermal melanocytes, binding between μ-opioid receptors and β-endorphin, an endogenous opioid, is associated with increased melanin production. This melanogenesis has been linked to hyperpigmentation.15 Given the similarity between kratom alkaloids and β-endorphin in opioid-receptor binding, it is possible that kratom-induced hyperpigmentation may occur through a similar mechanism involving μ-opioid receptors and melanogenesis in epidermal melanocytes. Moreover, some researchers have theorized that sun exposure may result in free radical formation of certain drugs or their metabolites. These free radicals then can interact with cellular DNA, triggering the release of pigmentary mediators and resulting in hyperpigmentation.16 This theory may explain the photodistributed pattern of kratom-induced hyperpigmentation. Further studies are needed to understand the mechanism behind this adverse reaction and its implications for patient treatment.

Literature on kratom-induced hyperpigmentation is limited. Powell et al17 reported a similar case of kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation—a White man had taken kratom to reduce opioid use and subsequently developed hyperpigmented patches on the arms and face. Moreover, anonymous Reddit users have shared anecdotal reports of hyperpigmentation following kratom use.18

Physicians should be aware of hyperpigmentation as a potential adverse reaction of kratom use as its prevalence increases globally. Further research is warranted to elucidate the mechanism behind this adverse reaction and identify risk factors.

- Prozialeck WC, Avery BA, Boyer EW, et al. Kratom policy: the challenge of balancing therapeutic potential with public safety. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;70:70-77. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.05.003

- Bergen-Cico D, MacClurg K. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) use, addiction potential, and legal status. In: Preedy VR, ed. Neuropathology of Drug Addictions and Substance Misuse. 2016:903-911. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800634-4.00089-5

- Warner ML, Kaufman NC, Grundmann O. The pharmacology and toxicology of kratom: from traditional herb to drug of abuse. Int J Legal Med. 2016;130:127-138. doi:10.1007/s00414-015-1279-y

- Transnational Institute. Kratom in Thailand: decriminalisation and community control? May 3, 2011. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.tni.org/en/publication/kratom-in-thailand-decriminalisation-and-community-control

- Eastlack SC, Cornett EM, Kaye AD. Kratom—pharmacology, clinical implications, and outlook: a comprehensive review. Pain Ther. 2020;9:55-69. doi:10.1007/s40122-020-00151-x

- Reyes R. Family of Florida mom who died from herbal substance kratom wins $11M suit. New York Post. July 30, 2023. Updated July 31, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://nypost.com/2023/07/30/family-of-florida-mom-who-died-from-herbal-substance-kratom-wins-11m-suit/

- Garcia-Romeu A, Cox DJ, Smith KE, et al. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa): user demographics, use patterns, and implications for the opioid epidemic. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;208:107849. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107849

- Mayo Clinic. Kratom: unsafe and ineffective. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/consumer-health/in-depth/kratom/art-20402171

- Sethi R, Hoang N, Ravishankar DA, et al. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa): friend or foe? Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020;22:19nr02507.

- Eggleston W, Stoppacher R, Suen K, et al. Kratom use and toxicities in the United States. Pharmacother J Hum Pharmacol Drug Ther. 2019;39:775-777. doi:10.1002/phar.2280

- Qrius. 6 benefits of kratom you should know for healthy skin. March 21, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://qrius.com/6-benefits-of-kratom-you-should-know-for-healthy-skin/

- Blomberg M, Zachariae COC, Grønhøj F. Hyperpigmentation of the face following adalimumab treatment. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:546-547. doi:10.2340/00015555-0697

- Matsumoto K, Hatori Y, Murayama T, et al. Involvement of μ-opioid receptors in antinociception and inhibition of gastrointestinal transit induced by 7-hydroxymitragynine, isolated from Thai herbal medicine Mitragyna speciosa. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;549:63-70. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.08.013

- Jentsch MJ, Pippin MM. Kratom. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Bigliardi PL, Tobin DJ, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, et al. Opioids and the skin—where do we stand? Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:424-430.

- Boyer M, Katta R, Markus R. Diltiazem-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:10. doi:10.5070/D33c97j4z5

- Powell LR, Ryser TJ, Morey GE, et al. Kratom as a novel cause of photodistributed hyperpigmentation. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;28:145-148. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.07.033

- Haccoon. Skin discoloring? Reddit. June 30, 2019. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.reddit.com/r/quittingkratom/comments/c7b1cm/skin_discoloring/

To the Editor:

Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) is an evergreen tree native to Southeast Asia.1 Its leaves contain psychoactive compounds including mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine, which exert dose-dependent effects on the central nervous system through opioid and monoaminergic receptors.2,3 At low doses (1–5 g), kratom elicits mild stimulant effects such as increased sociability, alertness, and talkativeness. At high doses (5–15 g), kratom has depressant effects that can provide relief from pain and opioid-withdrawal symptoms.3

Traditionally, kratom has been used in Southeast Asia for recreational and ceremonial purposes, to ease opioid-withdrawal symptoms, and to reduce fatigue from manual labor.4 In the 21st century, availability of kratom expanded to Europe, Australia, and the United States, largely facilitated by widespread dissemination of deceitful marketing and unregulated sales on the internet.1 Although large-scale epidemiologic studies evaluating kratom’s prevalence are scarce, available evidence indicates rising worldwide usage, with a notable increase in kratom-related poison center calls between 2011 and 2017 in the United States.5 In July 2023, kratom made headlines due to the death of a woman in Florida following use of the substance.6

A cross-sectional study revealed that in the United States, kratom typically is used by White individuals for self-treatment of anxiety, depression, pain, and opioid withdrawal.7 However, the potential for severe adverse effects and dependence on kratom can outweigh the benefits.6,8 Reported adverse effects of kratom include tachycardia, hypercholesteremia, liver injury, hallucinations, respiratory depression, seizure, coma, and death.9,10 We present a case of kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation.

A 63-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with diffuse tender, pruritic, hyperpigmented skin lesions that developed over the course of 1 year. The lesions were distributed on sun-exposed areas, including the face, neck, and forearms (Figure 1). The patient reported no other major symptoms, and his health was otherwise unremarkable. He had a medical history of psoriasiform and spongiotic dermatitis consistent with eczema, psoriasis, hypercholesteremia, and hyperlipidemia. The patient was not taking any medications at the time of presentation. He had a family history of plaque psoriasis in his father. Five years prior to the current presentation, the patient was treated with adalimumab for steroid-resistant psoriasis; however, despite initial improvement, he experienced recurrence of scaly erythematous plaques and had discontinued adalimumab the year prior to presentation.

When adalimumab was discontinued, the patient sought alternative treatment for the skin symptoms and began self-administering kratom in an attempt to alleviate associated physical discomfort. He ingested approximately 3 bottles of liquid kratom per day, with each bottle containing 180 mg of mitragynine and less than 8 mg of 7-hydroxymitragynine. Although not scientifically proven, kratom has been colloquially advertised to improve psoriasis.11 The patient reported no other medication use or allergies.

Shave biopsies of hyperpigmented lesions on the right side of the neck, ear, and forearm were performed. Histopathology revealed a sparse superficial, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltrate accompanied by a prominent number of melanophages in the superficial dermis (Figure 2). Special stains further confirmed that the pigment was melanin; the specimens stained positive with Fontana-Masson stain (Figure 3) and negative with an iron stain (Figure 4).

Adalimumab-induced hyperpigmentation was considered. A prior case of adalimumab-induced hyperpigmentation manifested on the face. Histopathology was consistent with a superficial, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltrate with melanophages in the dermis; however, hyperpigmentation was absent in the periorbital area, and affected areas faded 4 months after discontinuation of adalimumab.12 Our patient presented with hyperpigmentation 1 year after adalimumab cessation, and the hyperpigmented areas included the periorbital region. Because of the distinct temporal and clinical features, adalimumab-induced hyperpigmentation was eliminated from the differential diagnosis.

Based on the photodistributed pattern of hyperpigmentation, histopathology, and the temporal relationship between hyperpigmentation onset and kratom usage, a diagnosis of kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation was made. The patient was advised to discontinue kratom use and use sun protection to prevent further photodamage. The patient subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Kratom alkaloids bind all 3 opioid receptors—μOP, δOP, and κOPs—in a G-protein–biased manner with 7-hydroxymitragynine, the most pharmacologically active alkaloid, exhibiting a higher affinity for μ-opioid receptors.13,14 In human epidermal melanocytes, binding between μ-opioid receptors and β-endorphin, an endogenous opioid, is associated with increased melanin production. This melanogenesis has been linked to hyperpigmentation.15 Given the similarity between kratom alkaloids and β-endorphin in opioid-receptor binding, it is possible that kratom-induced hyperpigmentation may occur through a similar mechanism involving μ-opioid receptors and melanogenesis in epidermal melanocytes. Moreover, some researchers have theorized that sun exposure may result in free radical formation of certain drugs or their metabolites. These free radicals then can interact with cellular DNA, triggering the release of pigmentary mediators and resulting in hyperpigmentation.16 This theory may explain the photodistributed pattern of kratom-induced hyperpigmentation. Further studies are needed to understand the mechanism behind this adverse reaction and its implications for patient treatment.

Literature on kratom-induced hyperpigmentation is limited. Powell et al17 reported a similar case of kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation—a White man had taken kratom to reduce opioid use and subsequently developed hyperpigmented patches on the arms and face. Moreover, anonymous Reddit users have shared anecdotal reports of hyperpigmentation following kratom use.18

Physicians should be aware of hyperpigmentation as a potential adverse reaction of kratom use as its prevalence increases globally. Further research is warranted to elucidate the mechanism behind this adverse reaction and identify risk factors.

To the Editor:

Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) is an evergreen tree native to Southeast Asia.1 Its leaves contain psychoactive compounds including mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine, which exert dose-dependent effects on the central nervous system through opioid and monoaminergic receptors.2,3 At low doses (1–5 g), kratom elicits mild stimulant effects such as increased sociability, alertness, and talkativeness. At high doses (5–15 g), kratom has depressant effects that can provide relief from pain and opioid-withdrawal symptoms.3

Traditionally, kratom has been used in Southeast Asia for recreational and ceremonial purposes, to ease opioid-withdrawal symptoms, and to reduce fatigue from manual labor.4 In the 21st century, availability of kratom expanded to Europe, Australia, and the United States, largely facilitated by widespread dissemination of deceitful marketing and unregulated sales on the internet.1 Although large-scale epidemiologic studies evaluating kratom’s prevalence are scarce, available evidence indicates rising worldwide usage, with a notable increase in kratom-related poison center calls between 2011 and 2017 in the United States.5 In July 2023, kratom made headlines due to the death of a woman in Florida following use of the substance.6

A cross-sectional study revealed that in the United States, kratom typically is used by White individuals for self-treatment of anxiety, depression, pain, and opioid withdrawal.7 However, the potential for severe adverse effects and dependence on kratom can outweigh the benefits.6,8 Reported adverse effects of kratom include tachycardia, hypercholesteremia, liver injury, hallucinations, respiratory depression, seizure, coma, and death.9,10 We present a case of kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation.

A 63-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with diffuse tender, pruritic, hyperpigmented skin lesions that developed over the course of 1 year. The lesions were distributed on sun-exposed areas, including the face, neck, and forearms (Figure 1). The patient reported no other major symptoms, and his health was otherwise unremarkable. He had a medical history of psoriasiform and spongiotic dermatitis consistent with eczema, psoriasis, hypercholesteremia, and hyperlipidemia. The patient was not taking any medications at the time of presentation. He had a family history of plaque psoriasis in his father. Five years prior to the current presentation, the patient was treated with adalimumab for steroid-resistant psoriasis; however, despite initial improvement, he experienced recurrence of scaly erythematous plaques and had discontinued adalimumab the year prior to presentation.

When adalimumab was discontinued, the patient sought alternative treatment for the skin symptoms and began self-administering kratom in an attempt to alleviate associated physical discomfort. He ingested approximately 3 bottles of liquid kratom per day, with each bottle containing 180 mg of mitragynine and less than 8 mg of 7-hydroxymitragynine. Although not scientifically proven, kratom has been colloquially advertised to improve psoriasis.11 The patient reported no other medication use or allergies.

Shave biopsies of hyperpigmented lesions on the right side of the neck, ear, and forearm were performed. Histopathology revealed a sparse superficial, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltrate accompanied by a prominent number of melanophages in the superficial dermis (Figure 2). Special stains further confirmed that the pigment was melanin; the specimens stained positive with Fontana-Masson stain (Figure 3) and negative with an iron stain (Figure 4).

Adalimumab-induced hyperpigmentation was considered. A prior case of adalimumab-induced hyperpigmentation manifested on the face. Histopathology was consistent with a superficial, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltrate with melanophages in the dermis; however, hyperpigmentation was absent in the periorbital area, and affected areas faded 4 months after discontinuation of adalimumab.12 Our patient presented with hyperpigmentation 1 year after adalimumab cessation, and the hyperpigmented areas included the periorbital region. Because of the distinct temporal and clinical features, adalimumab-induced hyperpigmentation was eliminated from the differential diagnosis.

Based on the photodistributed pattern of hyperpigmentation, histopathology, and the temporal relationship between hyperpigmentation onset and kratom usage, a diagnosis of kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation was made. The patient was advised to discontinue kratom use and use sun protection to prevent further photodamage. The patient subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Kratom alkaloids bind all 3 opioid receptors—μOP, δOP, and κOPs—in a G-protein–biased manner with 7-hydroxymitragynine, the most pharmacologically active alkaloid, exhibiting a higher affinity for μ-opioid receptors.13,14 In human epidermal melanocytes, binding between μ-opioid receptors and β-endorphin, an endogenous opioid, is associated with increased melanin production. This melanogenesis has been linked to hyperpigmentation.15 Given the similarity between kratom alkaloids and β-endorphin in opioid-receptor binding, it is possible that kratom-induced hyperpigmentation may occur through a similar mechanism involving μ-opioid receptors and melanogenesis in epidermal melanocytes. Moreover, some researchers have theorized that sun exposure may result in free radical formation of certain drugs or their metabolites. These free radicals then can interact with cellular DNA, triggering the release of pigmentary mediators and resulting in hyperpigmentation.16 This theory may explain the photodistributed pattern of kratom-induced hyperpigmentation. Further studies are needed to understand the mechanism behind this adverse reaction and its implications for patient treatment.

Literature on kratom-induced hyperpigmentation is limited. Powell et al17 reported a similar case of kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation—a White man had taken kratom to reduce opioid use and subsequently developed hyperpigmented patches on the arms and face. Moreover, anonymous Reddit users have shared anecdotal reports of hyperpigmentation following kratom use.18

Physicians should be aware of hyperpigmentation as a potential adverse reaction of kratom use as its prevalence increases globally. Further research is warranted to elucidate the mechanism behind this adverse reaction and identify risk factors.

- Prozialeck WC, Avery BA, Boyer EW, et al. Kratom policy: the challenge of balancing therapeutic potential with public safety. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;70:70-77. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.05.003

- Bergen-Cico D, MacClurg K. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) use, addiction potential, and legal status. In: Preedy VR, ed. Neuropathology of Drug Addictions and Substance Misuse. 2016:903-911. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800634-4.00089-5

- Warner ML, Kaufman NC, Grundmann O. The pharmacology and toxicology of kratom: from traditional herb to drug of abuse. Int J Legal Med. 2016;130:127-138. doi:10.1007/s00414-015-1279-y

- Transnational Institute. Kratom in Thailand: decriminalisation and community control? May 3, 2011. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.tni.org/en/publication/kratom-in-thailand-decriminalisation-and-community-control

- Eastlack SC, Cornett EM, Kaye AD. Kratom—pharmacology, clinical implications, and outlook: a comprehensive review. Pain Ther. 2020;9:55-69. doi:10.1007/s40122-020-00151-x

- Reyes R. Family of Florida mom who died from herbal substance kratom wins $11M suit. New York Post. July 30, 2023. Updated July 31, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://nypost.com/2023/07/30/family-of-florida-mom-who-died-from-herbal-substance-kratom-wins-11m-suit/

- Garcia-Romeu A, Cox DJ, Smith KE, et al. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa): user demographics, use patterns, and implications for the opioid epidemic. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;208:107849. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107849

- Mayo Clinic. Kratom: unsafe and ineffective. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/consumer-health/in-depth/kratom/art-20402171

- Sethi R, Hoang N, Ravishankar DA, et al. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa): friend or foe? Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020;22:19nr02507.

- Eggleston W, Stoppacher R, Suen K, et al. Kratom use and toxicities in the United States. Pharmacother J Hum Pharmacol Drug Ther. 2019;39:775-777. doi:10.1002/phar.2280

- Qrius. 6 benefits of kratom you should know for healthy skin. March 21, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://qrius.com/6-benefits-of-kratom-you-should-know-for-healthy-skin/

- Blomberg M, Zachariae COC, Grønhøj F. Hyperpigmentation of the face following adalimumab treatment. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:546-547. doi:10.2340/00015555-0697

- Matsumoto K, Hatori Y, Murayama T, et al. Involvement of μ-opioid receptors in antinociception and inhibition of gastrointestinal transit induced by 7-hydroxymitragynine, isolated from Thai herbal medicine Mitragyna speciosa. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;549:63-70. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.08.013

- Jentsch MJ, Pippin MM. Kratom. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Bigliardi PL, Tobin DJ, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, et al. Opioids and the skin—where do we stand? Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:424-430.

- Boyer M, Katta R, Markus R. Diltiazem-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:10. doi:10.5070/D33c97j4z5

- Powell LR, Ryser TJ, Morey GE, et al. Kratom as a novel cause of photodistributed hyperpigmentation. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;28:145-148. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.07.033

- Haccoon. Skin discoloring? Reddit. June 30, 2019. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.reddit.com/r/quittingkratom/comments/c7b1cm/skin_discoloring/

- Prozialeck WC, Avery BA, Boyer EW, et al. Kratom policy: the challenge of balancing therapeutic potential with public safety. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;70:70-77. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.05.003

- Bergen-Cico D, MacClurg K. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) use, addiction potential, and legal status. In: Preedy VR, ed. Neuropathology of Drug Addictions and Substance Misuse. 2016:903-911. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800634-4.00089-5

- Warner ML, Kaufman NC, Grundmann O. The pharmacology and toxicology of kratom: from traditional herb to drug of abuse. Int J Legal Med. 2016;130:127-138. doi:10.1007/s00414-015-1279-y

- Transnational Institute. Kratom in Thailand: decriminalisation and community control? May 3, 2011. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.tni.org/en/publication/kratom-in-thailand-decriminalisation-and-community-control

- Eastlack SC, Cornett EM, Kaye AD. Kratom—pharmacology, clinical implications, and outlook: a comprehensive review. Pain Ther. 2020;9:55-69. doi:10.1007/s40122-020-00151-x

- Reyes R. Family of Florida mom who died from herbal substance kratom wins $11M suit. New York Post. July 30, 2023. Updated July 31, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://nypost.com/2023/07/30/family-of-florida-mom-who-died-from-herbal-substance-kratom-wins-11m-suit/

- Garcia-Romeu A, Cox DJ, Smith KE, et al. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa): user demographics, use patterns, and implications for the opioid epidemic. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;208:107849. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107849

- Mayo Clinic. Kratom: unsafe and ineffective. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/consumer-health/in-depth/kratom/art-20402171

- Sethi R, Hoang N, Ravishankar DA, et al. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa): friend or foe? Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020;22:19nr02507.

- Eggleston W, Stoppacher R, Suen K, et al. Kratom use and toxicities in the United States. Pharmacother J Hum Pharmacol Drug Ther. 2019;39:775-777. doi:10.1002/phar.2280

- Qrius. 6 benefits of kratom you should know for healthy skin. March 21, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://qrius.com/6-benefits-of-kratom-you-should-know-for-healthy-skin/

- Blomberg M, Zachariae COC, Grønhøj F. Hyperpigmentation of the face following adalimumab treatment. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:546-547. doi:10.2340/00015555-0697

- Matsumoto K, Hatori Y, Murayama T, et al. Involvement of μ-opioid receptors in antinociception and inhibition of gastrointestinal transit induced by 7-hydroxymitragynine, isolated from Thai herbal medicine Mitragyna speciosa. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;549:63-70. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.08.013

- Jentsch MJ, Pippin MM. Kratom. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Bigliardi PL, Tobin DJ, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, et al. Opioids and the skin—where do we stand? Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:424-430.

- Boyer M, Katta R, Markus R. Diltiazem-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:10. doi:10.5070/D33c97j4z5

- Powell LR, Ryser TJ, Morey GE, et al. Kratom as a novel cause of photodistributed hyperpigmentation. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;28:145-148. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.07.033

- Haccoon. Skin discoloring? Reddit. June 30, 2019. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://www.reddit.com/r/quittingkratom/comments/c7b1cm/skin_discoloring/

Practice Points

- Clinicians should be aware of photodistributed hyperpigmentation as a potential adverse effect of kratom usage.

- Kratom-induced photodistributed hyperpigmentation should be suspected in patients with hyperpigmented lesions in sun-exposed areas of the skin following kratom use. A biopsy of lesions should be obtained to confirm the diagnosis.

- Cessation of kratom should be recommended.

Unlocking the Potential of Baricitinib for Vitiligo

Vitiligo, the most common skin pigmentation disorder, has affected patients for thousands of years.1 The psychological and social impacts on patients include sleep and sexual disorders, low self-esteem, low quality of life, anxiety, and depression when compared to those without vitiligo.2,3 There have been substantial therapeutic advancements in the treatment of vitiligo, with the recent approval of ruxolitinib cream 1.5% by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2022 and by the European Medicines Agency in 2023.4 Ruxolitinib is the first topical Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor approved by the FDA for the treatment of nonsegmental vitiligo in patients 12 years and older, ushering in the era of JAK inhibitors for patients affected by vitiligo. The efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib was supported by 2 randomized clinical trials.4 It also is FDA approved for the intermittent and short-term treatment of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis in nonimmunocompromised patients 12 years and older whose disease is not adequately controlled with other topical medications.5

Vitiligo is characterized by an important inflammatory component, with the JAK/STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) pathway playing a crucial role in transmitting signals of inflammatory cytokines. In particular, IFN-γ and chemokines CXCL9 and CXCL10 are major contributors to the development of vitiligo, acting through the JAK/STAT pathway in local keratinocytes. Inhibiting JAK activity helps mitigate the effects of IFN-γ and downstream chemokines.6