User login

Pinto Bean Pressure Wraps: A Novel Approach to Treating Digital Warts

Practice Gap

Verruca vulgaris is a common dermatologic challenge due to its high prevalence and tendency to recur following routinely employed destructive modalities (eg, cryotherapy, electrosurgery), which can incur a considerable amount of pain and some risk for scarring.1,2 Other treatment methods for warts such as topical salicylic acid preparations, topical immunotherapy, or intralesional allergen injections often require multiple treatment sessions.3,4 Furthermore, the financial burden of traditional wart treatment can be substantial.4 Better techniques are needed to improve the clinician’s approach to treating warts. We describe a home-based technique to treat common digital warts using pinto bean pressure wraps to induce ischemic changes in wart tissue with similar response rates to commonly used modalities.

Technique

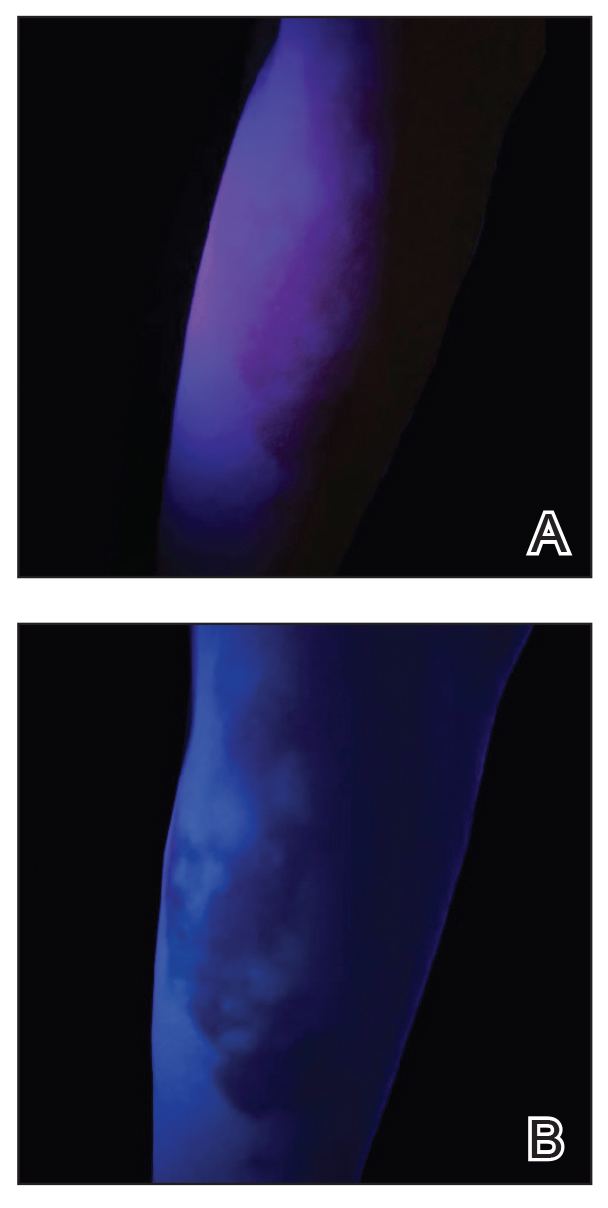

Our technique utilizes a small, hard, convex object that is applied directly over the digital wart. A simple self-adhesive wrap is used to cover the object and maintain constant pressure on the wart overnight. We typically use a dried pinto bean (a variety of the common bean Phaseolus vulgaris) acquired from a local grocery store due to its ideal size, hard surface, and convex shape (Figure 1). The bean is taped in place directly overlying the wart and covered with a self-adhesive wrap overnight. The wrap is removed in the morning, and often no further treatment is needed. The ischemic wart tissue is allowed to slough spontaneously over 1 to 2 weeks. No wound care or dressing is necessary (Figure 2). Larger warts may require application of the pressure wraps for 2 to 3 additional nights. While most warts resolve with this technique, we have observed a recurrence rate similar to that for cryotherapy. Patients are advised that any recurrent warts can be re-treated monthly, if needed, until resolution.

What to Use and How to Prepare—Any small, hard, convex object can be used for the pressure wrap; we also have used appropriately sized and shaped plastic shirt buttons with similar results. Home kits can be assembled in advance and provided to patients at their initial visit along with appropriate instructions (Figure 1A).

Effects on the Skin and Distal Digit—Application of pressure wraps does not harm normal skin; however, care should be taken when the self-adherent wrap is applied so as not to induce ischemia of the distal digit. The wrap should be applied using gentle pressure with patients experiencing minimal discomfort from the overnight application.

Indications—This pressure wrap technique can be employed on most digital warts, including periungual warts, which can be difficult to treat by other means. However, in our experience this technique is not effective for nondigital warts, likely due to the inability to maintain adequate pressure with the overlying dressing. Patients at risk for compromised digital perfusion, such as those with Raynaud phenomenon or systemic sclerosis, should not be treated with pressure wraps due to possible digital ischemia.

Precautions—Patients should be advised that the pinto bean should only be used if dry and should not be ingested. The bean can be a choking hazard for small children, therefore appropriate precautions should be used. Allergic contact dermatitis to the materials used in this technique is possible, but we have never observed this. The pinto bean can be reused for future application as long as it remains dry and provides a hard convex surface.

Practice Implications

The probable mechanism of the ischemic changes to the wart tissue likely is the occlusion of tortuous blood vessels in the dermal papillae, which are intrinsic to wart tissue and absent in normal skin.1 This pressure-induced ischemic injury allows for selective destruction of the wart tissue with sparing of the normal skin. Our technique is fairly novel, although at least one report in the literature has described the use of a mechanical device to induce ischemic changes in skin tags.5

The use of pinto bean pressure wraps to induce ischemic change in digital warts provides a low-risk and nearly pain-free alternative to more expensive and invasive treatment methods. Moreover, this technique allows for a low-cost home-based therapy that can be repeated easily for other digital sites or if recurrence is noted.

- Cardoso J, Calonje E. Cutaneous manifestations of human papillomaviruses: a review. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2011;20:145-154.

- Lipke M. An armamentarium of wart treatments. Clin Med Res. 2006;4:273-293. doi:10.3121/cmr.4.4.273

- Muse M, Stiff K, Glines K, et al. A review of intralesional wart therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:2. doi:10.5070/D3263048027

- Berna R, Margolis D, Barbieri J. Annual health care utilization and costs for treatment of cutaneous and anogenital warts among a commercially insured population in the US, 2017-2019. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:695-697. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0964

- Fredriksson C, Ilias M, Anderson C. New mechanical device for effective removal of skin tags in routine health care. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:9. doi:10.5070/D37tj2800k

Practice Gap

Verruca vulgaris is a common dermatologic challenge due to its high prevalence and tendency to recur following routinely employed destructive modalities (eg, cryotherapy, electrosurgery), which can incur a considerable amount of pain and some risk for scarring.1,2 Other treatment methods for warts such as topical salicylic acid preparations, topical immunotherapy, or intralesional allergen injections often require multiple treatment sessions.3,4 Furthermore, the financial burden of traditional wart treatment can be substantial.4 Better techniques are needed to improve the clinician’s approach to treating warts. We describe a home-based technique to treat common digital warts using pinto bean pressure wraps to induce ischemic changes in wart tissue with similar response rates to commonly used modalities.

Technique

Our technique utilizes a small, hard, convex object that is applied directly over the digital wart. A simple self-adhesive wrap is used to cover the object and maintain constant pressure on the wart overnight. We typically use a dried pinto bean (a variety of the common bean Phaseolus vulgaris) acquired from a local grocery store due to its ideal size, hard surface, and convex shape (Figure 1). The bean is taped in place directly overlying the wart and covered with a self-adhesive wrap overnight. The wrap is removed in the morning, and often no further treatment is needed. The ischemic wart tissue is allowed to slough spontaneously over 1 to 2 weeks. No wound care or dressing is necessary (Figure 2). Larger warts may require application of the pressure wraps for 2 to 3 additional nights. While most warts resolve with this technique, we have observed a recurrence rate similar to that for cryotherapy. Patients are advised that any recurrent warts can be re-treated monthly, if needed, until resolution.

What to Use and How to Prepare—Any small, hard, convex object can be used for the pressure wrap; we also have used appropriately sized and shaped plastic shirt buttons with similar results. Home kits can be assembled in advance and provided to patients at their initial visit along with appropriate instructions (Figure 1A).

Effects on the Skin and Distal Digit—Application of pressure wraps does not harm normal skin; however, care should be taken when the self-adherent wrap is applied so as not to induce ischemia of the distal digit. The wrap should be applied using gentle pressure with patients experiencing minimal discomfort from the overnight application.

Indications—This pressure wrap technique can be employed on most digital warts, including periungual warts, which can be difficult to treat by other means. However, in our experience this technique is not effective for nondigital warts, likely due to the inability to maintain adequate pressure with the overlying dressing. Patients at risk for compromised digital perfusion, such as those with Raynaud phenomenon or systemic sclerosis, should not be treated with pressure wraps due to possible digital ischemia.

Precautions—Patients should be advised that the pinto bean should only be used if dry and should not be ingested. The bean can be a choking hazard for small children, therefore appropriate precautions should be used. Allergic contact dermatitis to the materials used in this technique is possible, but we have never observed this. The pinto bean can be reused for future application as long as it remains dry and provides a hard convex surface.

Practice Implications

The probable mechanism of the ischemic changes to the wart tissue likely is the occlusion of tortuous blood vessels in the dermal papillae, which are intrinsic to wart tissue and absent in normal skin.1 This pressure-induced ischemic injury allows for selective destruction of the wart tissue with sparing of the normal skin. Our technique is fairly novel, although at least one report in the literature has described the use of a mechanical device to induce ischemic changes in skin tags.5

The use of pinto bean pressure wraps to induce ischemic change in digital warts provides a low-risk and nearly pain-free alternative to more expensive and invasive treatment methods. Moreover, this technique allows for a low-cost home-based therapy that can be repeated easily for other digital sites or if recurrence is noted.

Practice Gap

Verruca vulgaris is a common dermatologic challenge due to its high prevalence and tendency to recur following routinely employed destructive modalities (eg, cryotherapy, electrosurgery), which can incur a considerable amount of pain and some risk for scarring.1,2 Other treatment methods for warts such as topical salicylic acid preparations, topical immunotherapy, or intralesional allergen injections often require multiple treatment sessions.3,4 Furthermore, the financial burden of traditional wart treatment can be substantial.4 Better techniques are needed to improve the clinician’s approach to treating warts. We describe a home-based technique to treat common digital warts using pinto bean pressure wraps to induce ischemic changes in wart tissue with similar response rates to commonly used modalities.

Technique

Our technique utilizes a small, hard, convex object that is applied directly over the digital wart. A simple self-adhesive wrap is used to cover the object and maintain constant pressure on the wart overnight. We typically use a dried pinto bean (a variety of the common bean Phaseolus vulgaris) acquired from a local grocery store due to its ideal size, hard surface, and convex shape (Figure 1). The bean is taped in place directly overlying the wart and covered with a self-adhesive wrap overnight. The wrap is removed in the morning, and often no further treatment is needed. The ischemic wart tissue is allowed to slough spontaneously over 1 to 2 weeks. No wound care or dressing is necessary (Figure 2). Larger warts may require application of the pressure wraps for 2 to 3 additional nights. While most warts resolve with this technique, we have observed a recurrence rate similar to that for cryotherapy. Patients are advised that any recurrent warts can be re-treated monthly, if needed, until resolution.

What to Use and How to Prepare—Any small, hard, convex object can be used for the pressure wrap; we also have used appropriately sized and shaped plastic shirt buttons with similar results. Home kits can be assembled in advance and provided to patients at their initial visit along with appropriate instructions (Figure 1A).

Effects on the Skin and Distal Digit—Application of pressure wraps does not harm normal skin; however, care should be taken when the self-adherent wrap is applied so as not to induce ischemia of the distal digit. The wrap should be applied using gentle pressure with patients experiencing minimal discomfort from the overnight application.

Indications—This pressure wrap technique can be employed on most digital warts, including periungual warts, which can be difficult to treat by other means. However, in our experience this technique is not effective for nondigital warts, likely due to the inability to maintain adequate pressure with the overlying dressing. Patients at risk for compromised digital perfusion, such as those with Raynaud phenomenon or systemic sclerosis, should not be treated with pressure wraps due to possible digital ischemia.

Precautions—Patients should be advised that the pinto bean should only be used if dry and should not be ingested. The bean can be a choking hazard for small children, therefore appropriate precautions should be used. Allergic contact dermatitis to the materials used in this technique is possible, but we have never observed this. The pinto bean can be reused for future application as long as it remains dry and provides a hard convex surface.

Practice Implications

The probable mechanism of the ischemic changes to the wart tissue likely is the occlusion of tortuous blood vessels in the dermal papillae, which are intrinsic to wart tissue and absent in normal skin.1 This pressure-induced ischemic injury allows for selective destruction of the wart tissue with sparing of the normal skin. Our technique is fairly novel, although at least one report in the literature has described the use of a mechanical device to induce ischemic changes in skin tags.5

The use of pinto bean pressure wraps to induce ischemic change in digital warts provides a low-risk and nearly pain-free alternative to more expensive and invasive treatment methods. Moreover, this technique allows for a low-cost home-based therapy that can be repeated easily for other digital sites or if recurrence is noted.

- Cardoso J, Calonje E. Cutaneous manifestations of human papillomaviruses: a review. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2011;20:145-154.

- Lipke M. An armamentarium of wart treatments. Clin Med Res. 2006;4:273-293. doi:10.3121/cmr.4.4.273

- Muse M, Stiff K, Glines K, et al. A review of intralesional wart therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:2. doi:10.5070/D3263048027

- Berna R, Margolis D, Barbieri J. Annual health care utilization and costs for treatment of cutaneous and anogenital warts among a commercially insured population in the US, 2017-2019. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:695-697. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0964

- Fredriksson C, Ilias M, Anderson C. New mechanical device for effective removal of skin tags in routine health care. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:9. doi:10.5070/D37tj2800k

- Cardoso J, Calonje E. Cutaneous manifestations of human papillomaviruses: a review. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2011;20:145-154.

- Lipke M. An armamentarium of wart treatments. Clin Med Res. 2006;4:273-293. doi:10.3121/cmr.4.4.273

- Muse M, Stiff K, Glines K, et al. A review of intralesional wart therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:2. doi:10.5070/D3263048027

- Berna R, Margolis D, Barbieri J. Annual health care utilization and costs for treatment of cutaneous and anogenital warts among a commercially insured population in the US, 2017-2019. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:695-697. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0964

- Fredriksson C, Ilias M, Anderson C. New mechanical device for effective removal of skin tags in routine health care. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:9. doi:10.5070/D37tj2800k

Nailing the Nail Biopsy: Surgical Instruments and Their Function in Nail Biopsy Procedures

Practice Gap

The term nail biopsy (NB) may refer to a punch, excisional, shave, or longitudinal biopsy of the nail matrix and/or nail bed.1 Nail surgeries, including NBs, are performed relatively infrequently. In a study using data from the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database 2012-2017, only 1.01% of Mohs surgeons and 0.28% of general dermatologists in the United States performed NBs. Thirty-one states had no dermatologist-performed NBs, while 3 states had no nail biopsies performed by any physician, podiatrist, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant, indicating that there is a shortage of dermatology clinicians performing nail surgeries.2

Dermatologists may not be performing NBs due to unfamiliarity with nail unit anatomy and lack of formal NB training during residency.3 In a survey of 240 dermatology residents in the United States, 58% reported performing fewer than 10 nail procedures during residency, with 25% observing only.4 Of those surveyed, 1% had no exposure to nail procedures during 3 years of residency. Furthermore, when asked to assess their competency in nail surgery on a scale of not competent, competent, and very competent, approximately 30% responded that they were not competent.4 Without sufficient education on procedures involving the nail unit, residents may be reluctant to incorporate nail surgery into their clinical practice.

Due to their complexity, NBs require the use of several specialized surgical instruments that are not used for other dermatologic procedures, and residents and attending physicians who have limited nail training may be unfamiliar with these tools. To address this educational gap, we sought to create a guide that details the surgical instruments used for the nail matrix tangential excision (shave) biopsy technique—the most common technique used in our nail specialty clinic. This guide is intended for educational use by dermatologists who wish to incorporate NB as part of their practice.

Tools and Technique

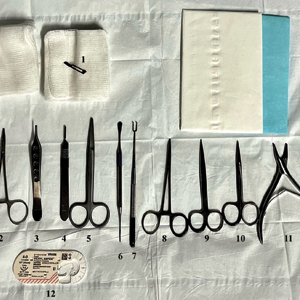

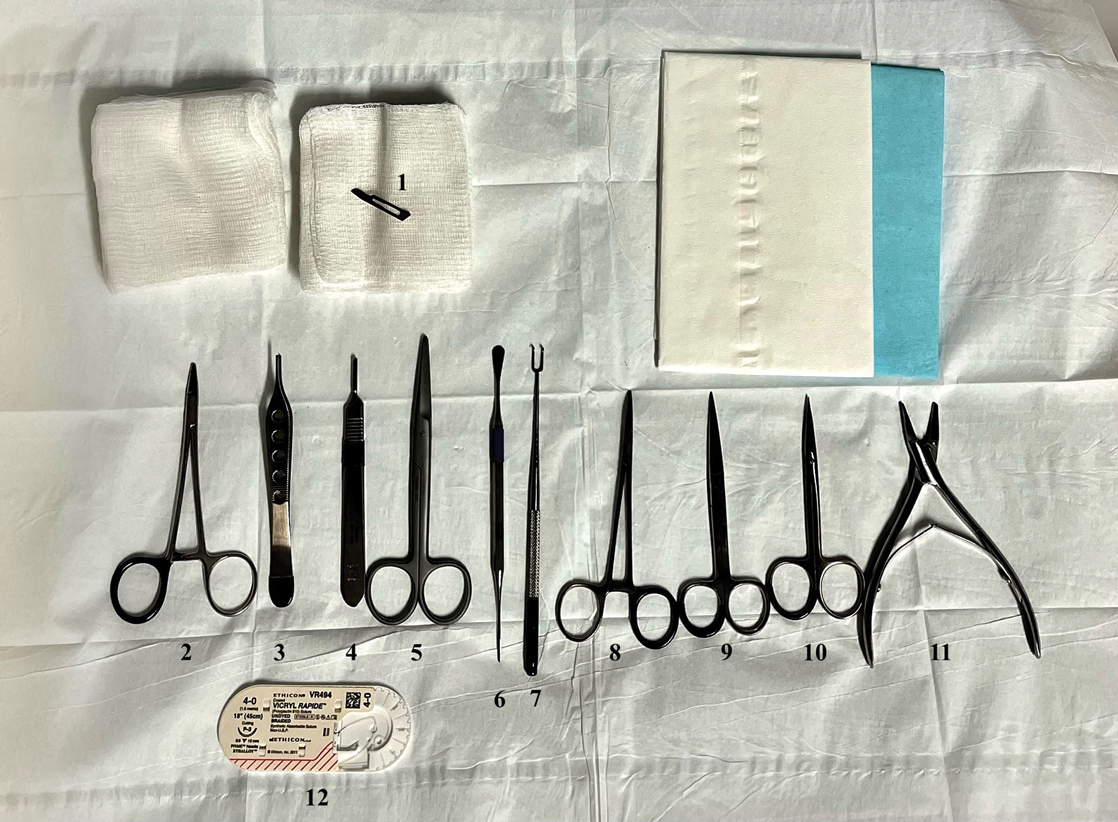

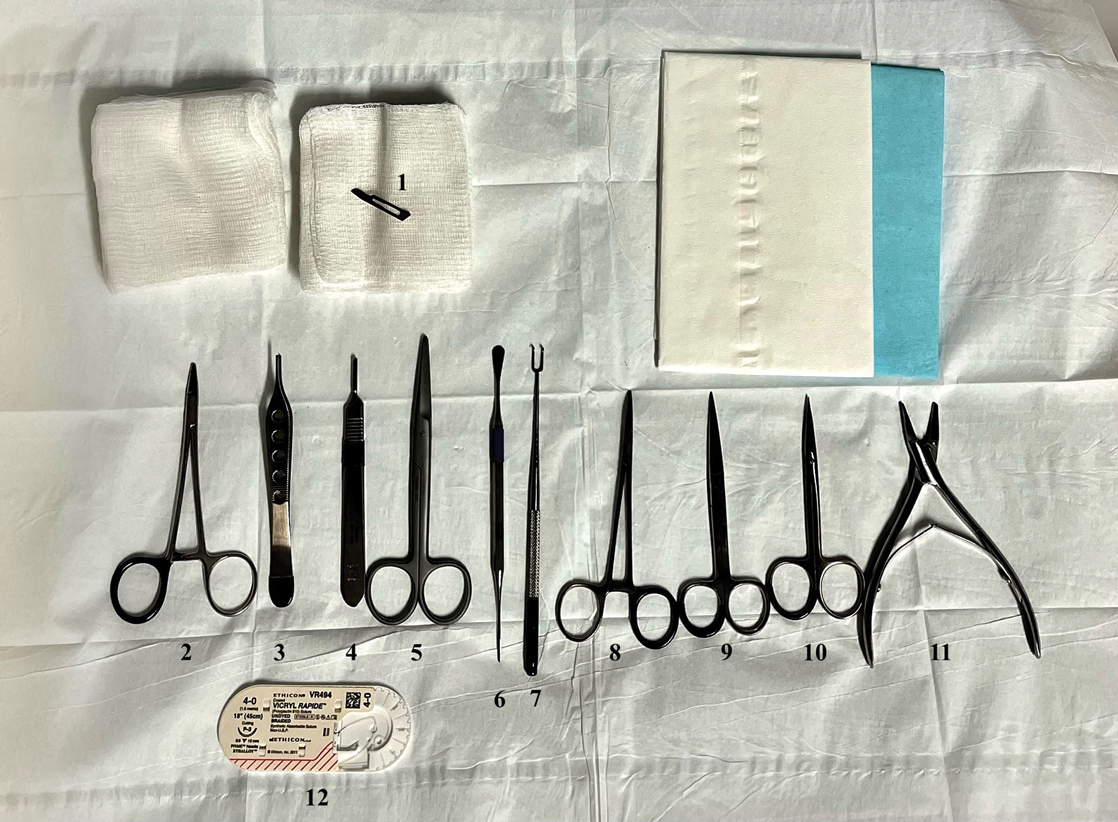

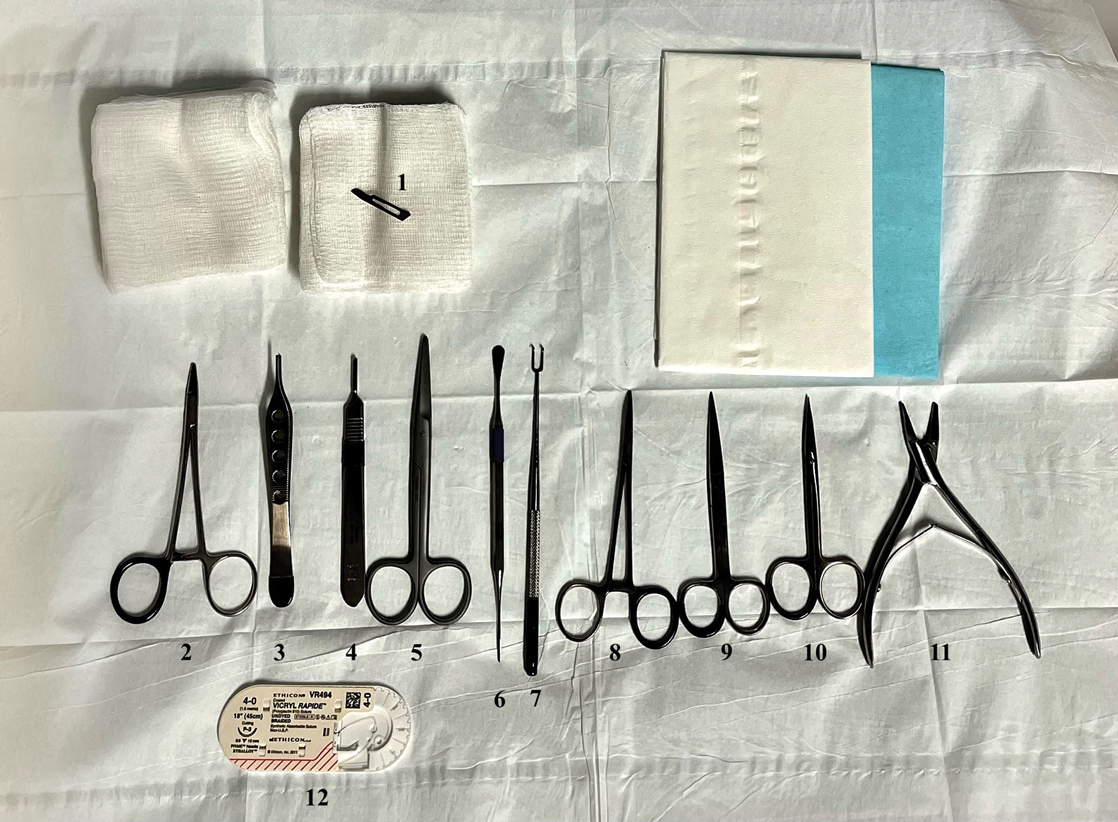

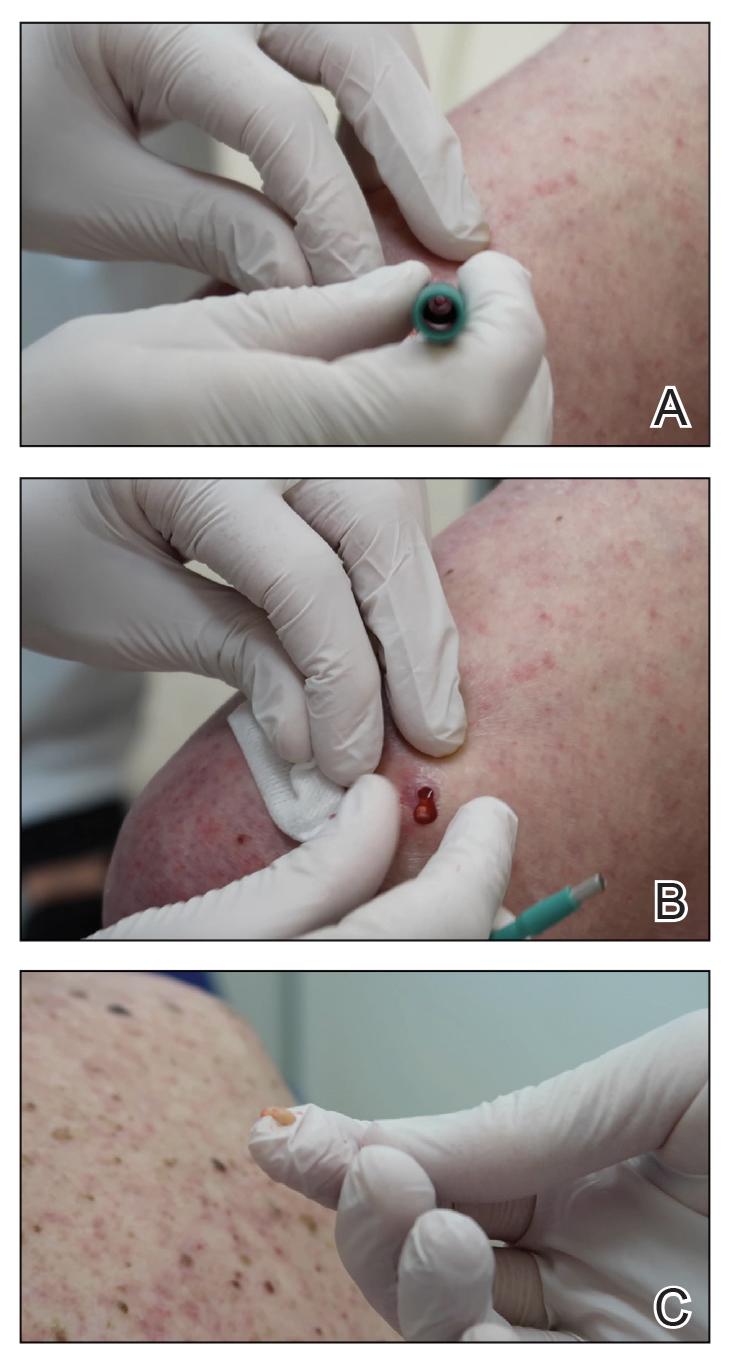

As a major referral center, our New York City–based nail specialty clinic performs a large volume of NBs, many of them performed for clinically concerning longitudinal melanonychias for which a nail matrix shave biopsy most often is performed. We utilize a standardized tray consisting of 12 surgical instruments that are needed to successfully perform a NB from start to finish (Figure). In addition to standard surgical tray items, such as sutures and tissue scissors, additional specialized instruments are necessary for NB procedures, including a nail elevator, an English nail splitter, and skin hook.

After the initial incisions are made at 45° angles to the proximal nail fold surrounding the longitudinal band, the nail elevator is used to separate the proximal nail plate from the underlying nail bed. The English nail splitter is used to create a transverse split separating the proximal from the distal nail plate, and the proximal nail plate then is retracted using a clamp. The skin hook is used to retract the proximal nail fold to expose the pigment in the nail matrix, which is biopsied using the #15 blade and sent for histopathology. The proximal nail fold and retracted nail plate then are put back in place, and absorbable sutures are used to repair the defect. In certain cases, a 3-mm punch biopsy may be used to sample the nail plate and/or the surrounding soft tissue.

Practice Implications

A guide to surgical tools used during NB procedures, including less commonly encountered tools such as a nail elevator and English nail splitter, helps to close the educational gap of NB procedures among dermatology trainees and attending physicians. In conjunction with practical training with cadavers and models, a guide to surgical tools can be reviewed by trainees before hands-on exposure to nail surgery in a clinical setting. By increasing awareness of the tools needed to complete the procedure from start to finish, dermatologists may feel more prepared and confident in their ability to perform NBs, ultimately allowing for more rapid diagnosis of nail malignancies.

- Grover C, Bansal S. Nail biopsy: a user’s manual. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:3-15. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_268_17

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of nail biopsies performed using the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database 2012 to 2017. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:e14928. doi:10.1111/dth.14928

- Hare AQ, Rich P. Clinical and educational gaps in diagnosis of nail disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:269-273. doi:10.1016/j.det.2016.02.002

- Lee EH, Nehal KS, Dusza SW, et al. Procedural dermatology training during dermatology residency: a survey of third-year dermatology residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:475-483.e4835. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.05.044

Practice Gap

The term nail biopsy (NB) may refer to a punch, excisional, shave, or longitudinal biopsy of the nail matrix and/or nail bed.1 Nail surgeries, including NBs, are performed relatively infrequently. In a study using data from the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database 2012-2017, only 1.01% of Mohs surgeons and 0.28% of general dermatologists in the United States performed NBs. Thirty-one states had no dermatologist-performed NBs, while 3 states had no nail biopsies performed by any physician, podiatrist, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant, indicating that there is a shortage of dermatology clinicians performing nail surgeries.2

Dermatologists may not be performing NBs due to unfamiliarity with nail unit anatomy and lack of formal NB training during residency.3 In a survey of 240 dermatology residents in the United States, 58% reported performing fewer than 10 nail procedures during residency, with 25% observing only.4 Of those surveyed, 1% had no exposure to nail procedures during 3 years of residency. Furthermore, when asked to assess their competency in nail surgery on a scale of not competent, competent, and very competent, approximately 30% responded that they were not competent.4 Without sufficient education on procedures involving the nail unit, residents may be reluctant to incorporate nail surgery into their clinical practice.

Due to their complexity, NBs require the use of several specialized surgical instruments that are not used for other dermatologic procedures, and residents and attending physicians who have limited nail training may be unfamiliar with these tools. To address this educational gap, we sought to create a guide that details the surgical instruments used for the nail matrix tangential excision (shave) biopsy technique—the most common technique used in our nail specialty clinic. This guide is intended for educational use by dermatologists who wish to incorporate NB as part of their practice.

Tools and Technique

As a major referral center, our New York City–based nail specialty clinic performs a large volume of NBs, many of them performed for clinically concerning longitudinal melanonychias for which a nail matrix shave biopsy most often is performed. We utilize a standardized tray consisting of 12 surgical instruments that are needed to successfully perform a NB from start to finish (Figure). In addition to standard surgical tray items, such as sutures and tissue scissors, additional specialized instruments are necessary for NB procedures, including a nail elevator, an English nail splitter, and skin hook.

After the initial incisions are made at 45° angles to the proximal nail fold surrounding the longitudinal band, the nail elevator is used to separate the proximal nail plate from the underlying nail bed. The English nail splitter is used to create a transverse split separating the proximal from the distal nail plate, and the proximal nail plate then is retracted using a clamp. The skin hook is used to retract the proximal nail fold to expose the pigment in the nail matrix, which is biopsied using the #15 blade and sent for histopathology. The proximal nail fold and retracted nail plate then are put back in place, and absorbable sutures are used to repair the defect. In certain cases, a 3-mm punch biopsy may be used to sample the nail plate and/or the surrounding soft tissue.

Practice Implications

A guide to surgical tools used during NB procedures, including less commonly encountered tools such as a nail elevator and English nail splitter, helps to close the educational gap of NB procedures among dermatology trainees and attending physicians. In conjunction with practical training with cadavers and models, a guide to surgical tools can be reviewed by trainees before hands-on exposure to nail surgery in a clinical setting. By increasing awareness of the tools needed to complete the procedure from start to finish, dermatologists may feel more prepared and confident in their ability to perform NBs, ultimately allowing for more rapid diagnosis of nail malignancies.

Practice Gap

The term nail biopsy (NB) may refer to a punch, excisional, shave, or longitudinal biopsy of the nail matrix and/or nail bed.1 Nail surgeries, including NBs, are performed relatively infrequently. In a study using data from the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database 2012-2017, only 1.01% of Mohs surgeons and 0.28% of general dermatologists in the United States performed NBs. Thirty-one states had no dermatologist-performed NBs, while 3 states had no nail biopsies performed by any physician, podiatrist, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant, indicating that there is a shortage of dermatology clinicians performing nail surgeries.2

Dermatologists may not be performing NBs due to unfamiliarity with nail unit anatomy and lack of formal NB training during residency.3 In a survey of 240 dermatology residents in the United States, 58% reported performing fewer than 10 nail procedures during residency, with 25% observing only.4 Of those surveyed, 1% had no exposure to nail procedures during 3 years of residency. Furthermore, when asked to assess their competency in nail surgery on a scale of not competent, competent, and very competent, approximately 30% responded that they were not competent.4 Without sufficient education on procedures involving the nail unit, residents may be reluctant to incorporate nail surgery into their clinical practice.

Due to their complexity, NBs require the use of several specialized surgical instruments that are not used for other dermatologic procedures, and residents and attending physicians who have limited nail training may be unfamiliar with these tools. To address this educational gap, we sought to create a guide that details the surgical instruments used for the nail matrix tangential excision (shave) biopsy technique—the most common technique used in our nail specialty clinic. This guide is intended for educational use by dermatologists who wish to incorporate NB as part of their practice.

Tools and Technique

As a major referral center, our New York City–based nail specialty clinic performs a large volume of NBs, many of them performed for clinically concerning longitudinal melanonychias for which a nail matrix shave biopsy most often is performed. We utilize a standardized tray consisting of 12 surgical instruments that are needed to successfully perform a NB from start to finish (Figure). In addition to standard surgical tray items, such as sutures and tissue scissors, additional specialized instruments are necessary for NB procedures, including a nail elevator, an English nail splitter, and skin hook.

After the initial incisions are made at 45° angles to the proximal nail fold surrounding the longitudinal band, the nail elevator is used to separate the proximal nail plate from the underlying nail bed. The English nail splitter is used to create a transverse split separating the proximal from the distal nail plate, and the proximal nail plate then is retracted using a clamp. The skin hook is used to retract the proximal nail fold to expose the pigment in the nail matrix, which is biopsied using the #15 blade and sent for histopathology. The proximal nail fold and retracted nail plate then are put back in place, and absorbable sutures are used to repair the defect. In certain cases, a 3-mm punch biopsy may be used to sample the nail plate and/or the surrounding soft tissue.

Practice Implications

A guide to surgical tools used during NB procedures, including less commonly encountered tools such as a nail elevator and English nail splitter, helps to close the educational gap of NB procedures among dermatology trainees and attending physicians. In conjunction with practical training with cadavers and models, a guide to surgical tools can be reviewed by trainees before hands-on exposure to nail surgery in a clinical setting. By increasing awareness of the tools needed to complete the procedure from start to finish, dermatologists may feel more prepared and confident in their ability to perform NBs, ultimately allowing for more rapid diagnosis of nail malignancies.

- Grover C, Bansal S. Nail biopsy: a user’s manual. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:3-15. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_268_17

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of nail biopsies performed using the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database 2012 to 2017. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:e14928. doi:10.1111/dth.14928

- Hare AQ, Rich P. Clinical and educational gaps in diagnosis of nail disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:269-273. doi:10.1016/j.det.2016.02.002

- Lee EH, Nehal KS, Dusza SW, et al. Procedural dermatology training during dermatology residency: a survey of third-year dermatology residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:475-483.e4835. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.05.044

- Grover C, Bansal S. Nail biopsy: a user’s manual. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:3-15. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_268_17

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of nail biopsies performed using the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database 2012 to 2017. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:e14928. doi:10.1111/dth.14928

- Hare AQ, Rich P. Clinical and educational gaps in diagnosis of nail disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:269-273. doi:10.1016/j.det.2016.02.002

- Lee EH, Nehal KS, Dusza SW, et al. Procedural dermatology training during dermatology residency: a survey of third-year dermatology residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:475-483.e4835. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.05.044

Enhanced Care for Pediatric Patients With Generalized Lichen Planus: Diagnosis and Treatment Tips

Practice Gap

Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory cutaneous disorder. Although it often is characterized by the 6 Ps—pruritic, polygonal, planar, purple, papules, and plaques with a predilection for the wrists and ankles—the presentation can vary in morphology and distribution.1-5 With an incidence of approximately 1% in the general population, LP is undoubtedly uncommon.1 Its prevalence in the pediatric population is especially low, with only 2% to 3% of cases manifesting in individuals younger than 20 years.2

Generalized LP (also referred to as eruptive or exanthematous LP) is a rarely reported clinical subtype in which lesions are disseminated or spread rapidly.5 The rarity of generalized LP in children often leads to misdiagnosis or delayed treatment, impacting the patient’s quality of life. Thus, there is a need for heightened awareness among clinicians on the variable presentation of LP in the pediatric population. Incorporating a punch biopsy for the diagnosis of LP when lesions manifest as widespread, erythematous to violaceous, flat-topped papules or plaques, along with the addition of an intramuscular (IM) injection in the treatment plan, improves overall patient outcomes.

Tools and Techniques

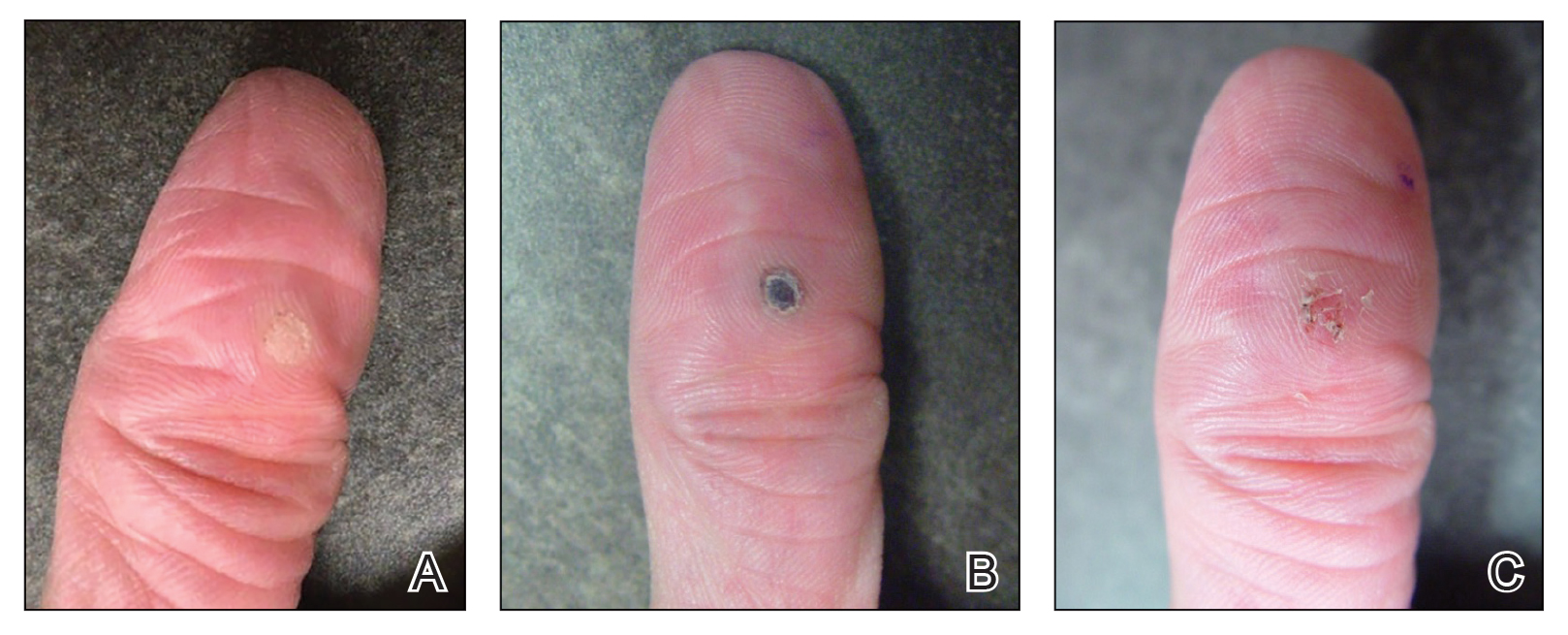

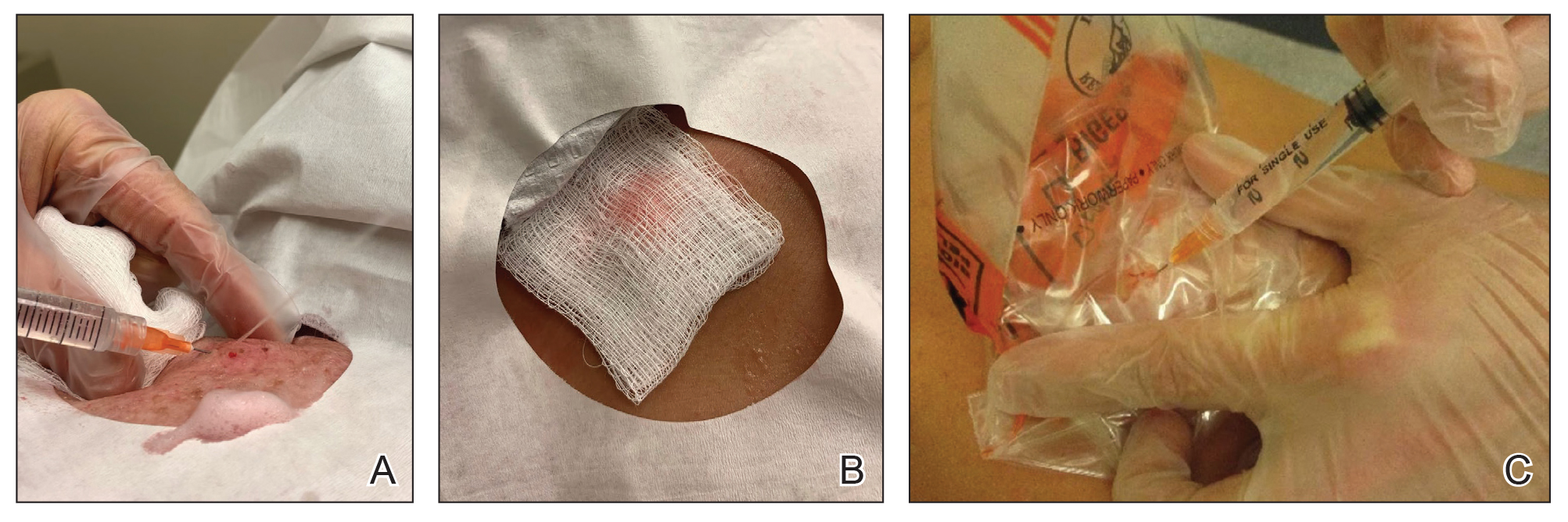

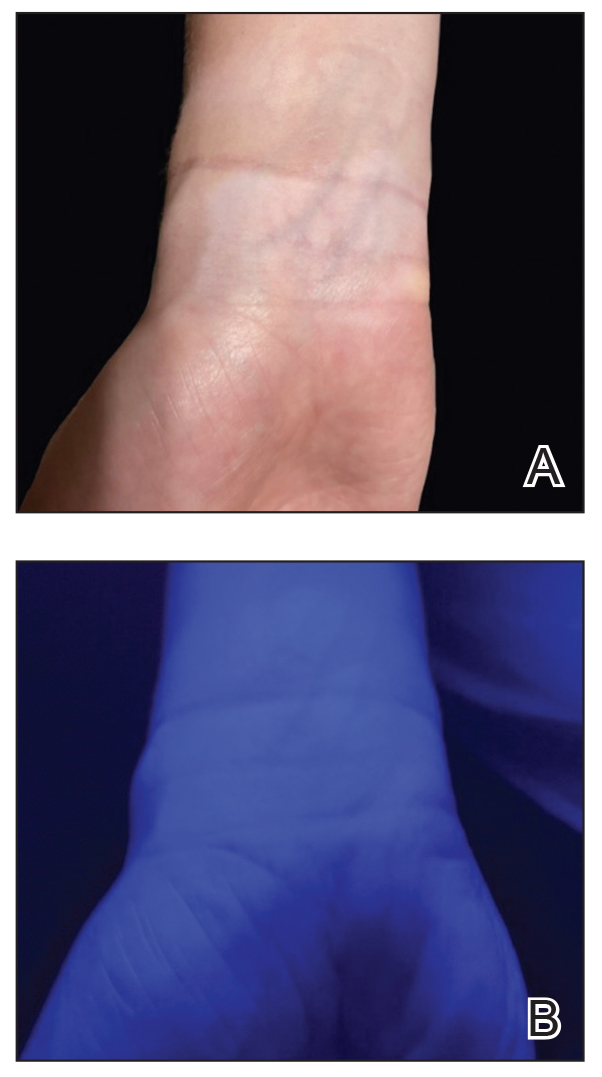

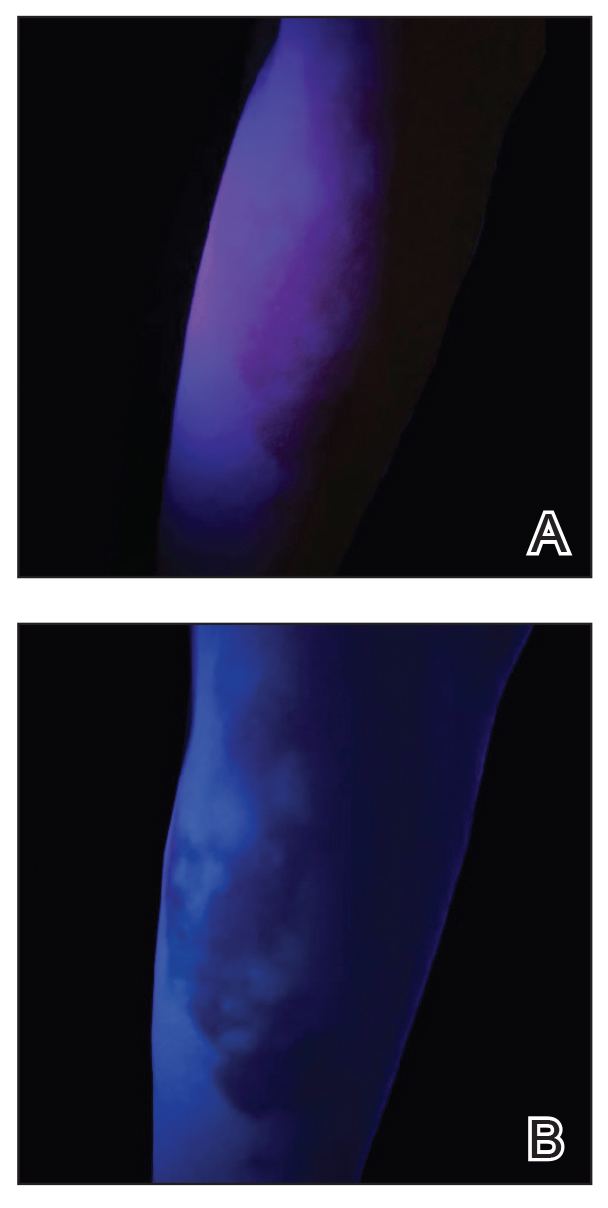

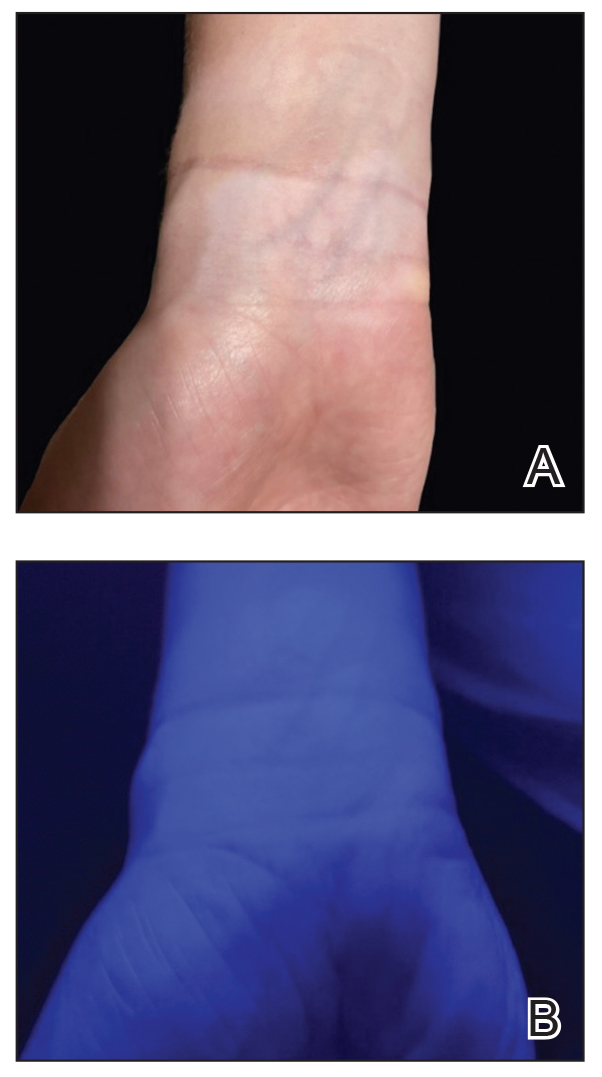

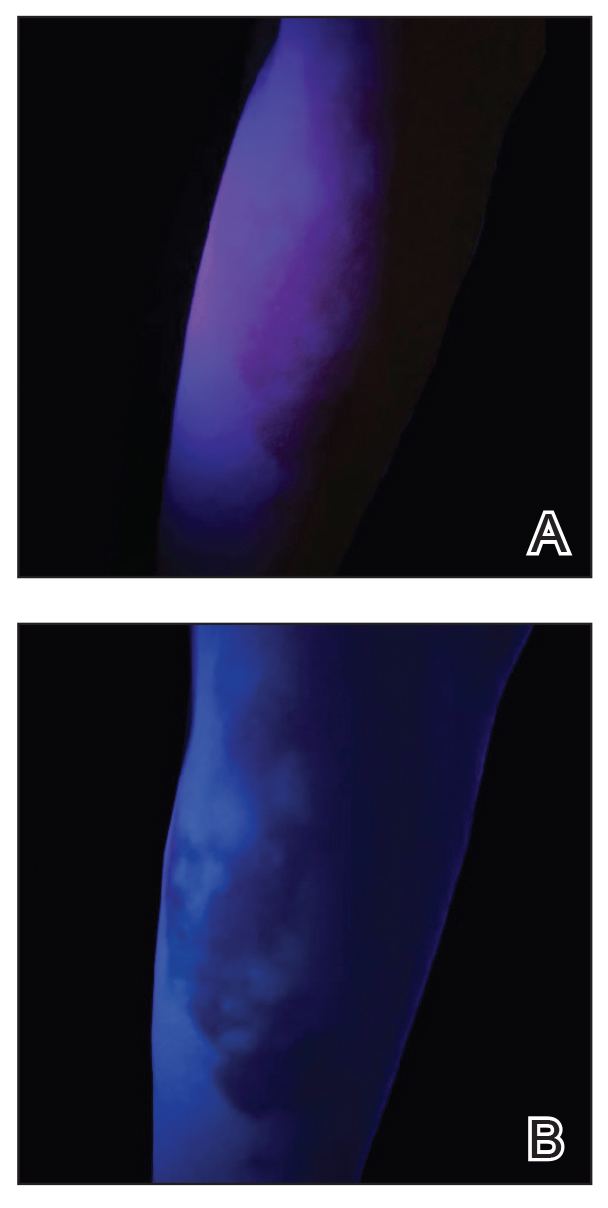

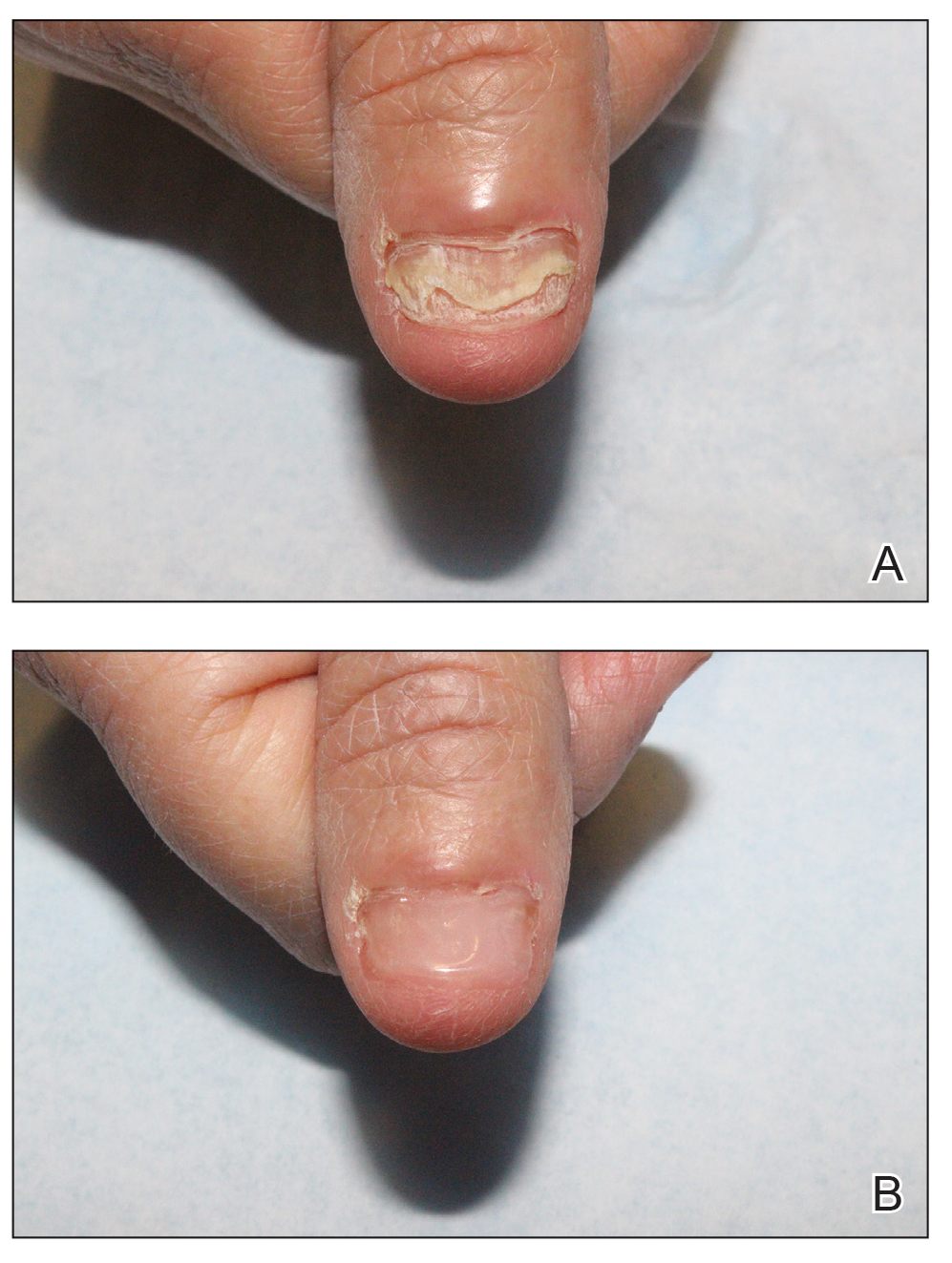

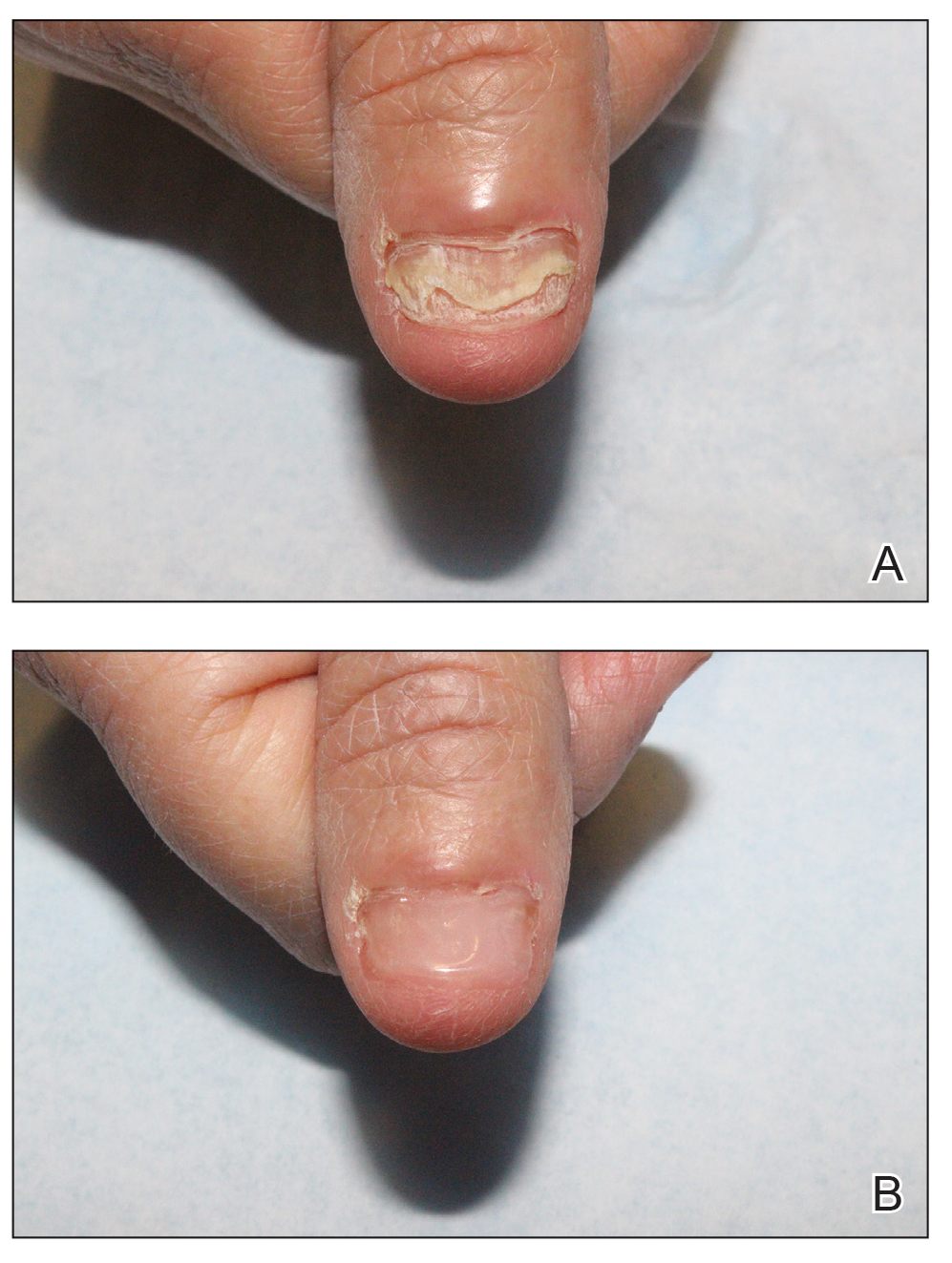

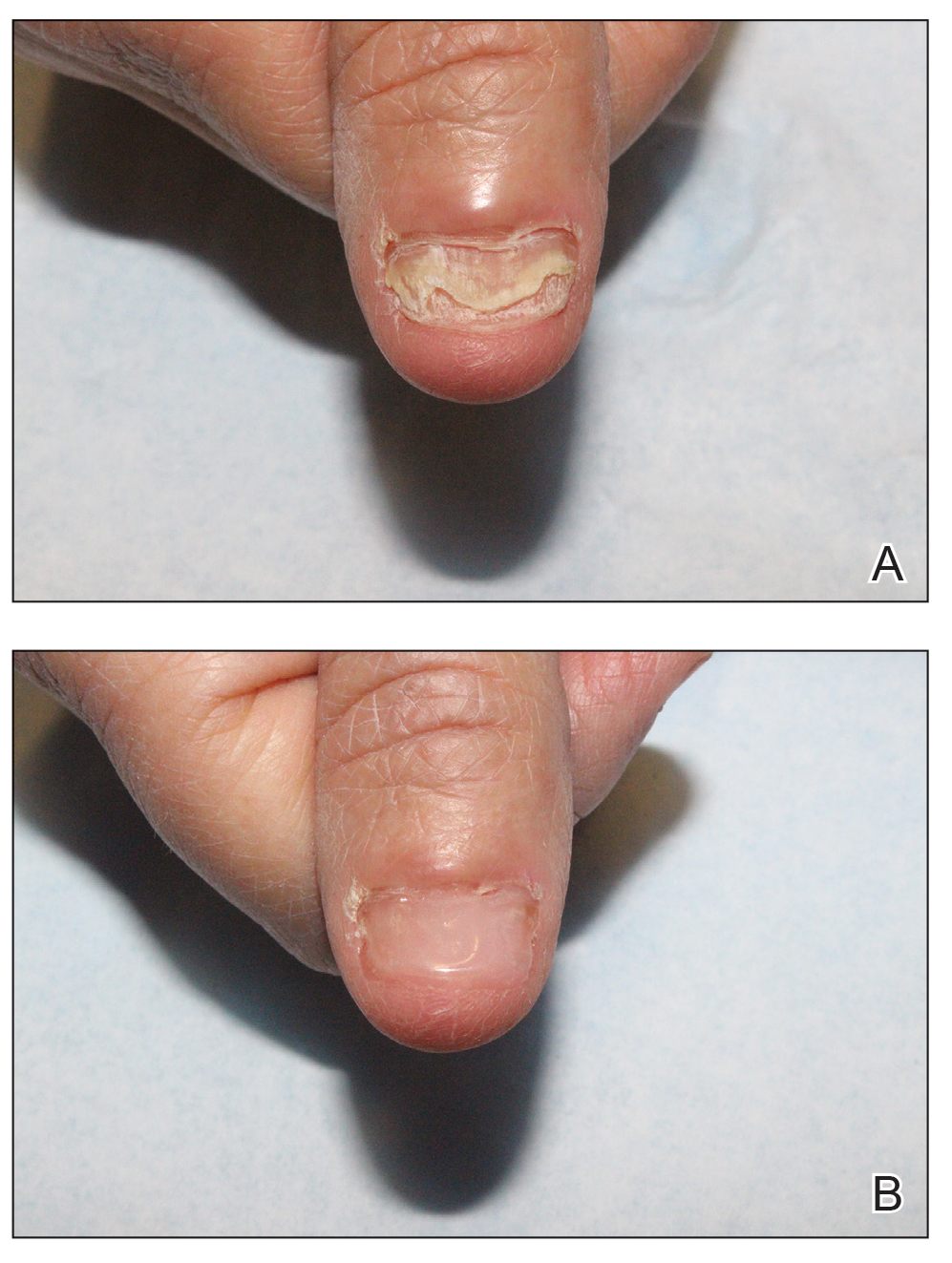

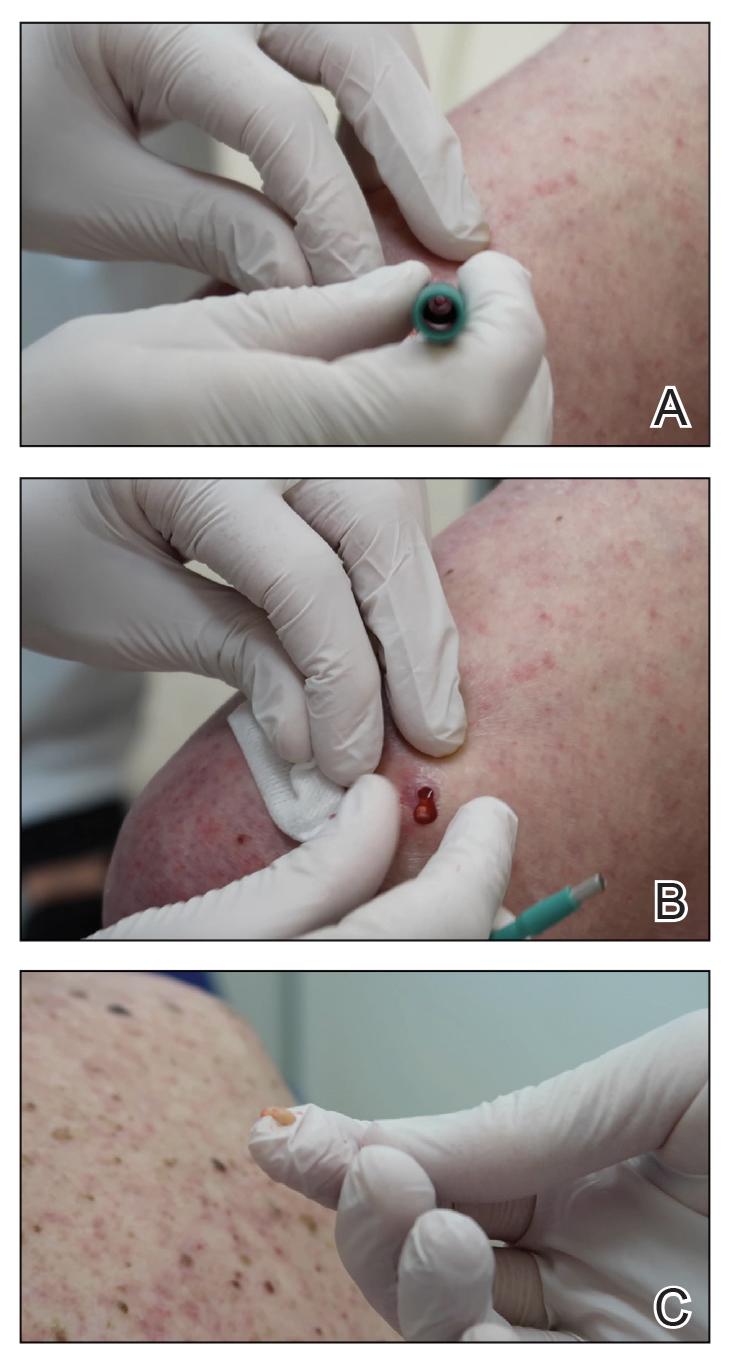

A detailed physical examination followed by a punch biopsy was critical for the diagnosis of generalized LP in a 7-year-old Black girl. The examination revealed a widespread distribution of dark, violaceous, polygonal, shiny, flat-topped, firm papules coalescing into plaques across the entire body, with a greater predilection for the legs and overlying joints (Figure, A). Some lesions exhibited fine, silver-white, reticular patterns consistent with Wickham striae. Notably, there was no involvement of the scalp, nails, or mucosal surfaces.

The patient had no relevant medical or family history of skin disease and no recent history of illness. She previously was treated by a pediatrician with triamcinolone cream 0.1%, a course of oral cephalexin, and oral cetirizine 10 mg once daily without relief of symptoms.

Although the clinical presentation was consistent with LP, the differential diagnosis included lichen simplex chronicus, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and generalized granuloma annulare. To address the need for early recognition of LP in pediatric patients, a punch biopsy of a lesion on the left anterior thigh was performed and showed lichenoid interface dermatitis—a pivotal finding in distinguishing LP from other conditions in the differential.

Given the patient’s age and severity of the LP, a combination of topical and systemic therapies was prescribed—clobetasol cream 0.025% twice daily and 1 injection of 0.5 cc of IM triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg/mL. This regimen was guided by the efficacy of IM injections in providing prompt symptomatic relief, particularly for patients with extensive disease or for those whose condition is refractory to topical treatments.6 Our patient achieved remarkable improvement at 2-week follow-up (Figure, B), without any observed adverse effects. At that time, the patient’s mother refused further systemic treatment and opted for only the topical therapy as well as natural light therapy.

Practice Implications

Timely and accurate diagnosis of LP in pediatric patients, especially those with skin of color, is crucial. Early intervention is especially important in mitigating the risk for chronic symptoms and preventing potential scarring, which tends to be more pronounced and challenging to treat in individuals with darker skin tones.7 Although not present in our patient, it is important to note that LP can affect the face (including the eyelids) as well as the palms and soles in pediatric patients with skin of color.

The most common approach to management of pediatric LP involves the use of a topical corticosteroid and an oral antihistamine, but the recalcitrant and generalized distribution of lesions warrants the administration of a systemic corticosteroid regardless of the patient’s age.6 In our patient, prompt administration of low-dose IM triamcinolone was both crucial and beneficial. Although an underutilized approach, IM triamcinolone helps to prevent the progression of lesions to the scalp, nails, and mucosa while also reducing inflammation and pruritus in glabrous skin.8

Triamcinolone acetonide injections—administered at concentrations of 5 to 40 mg/mL—directly into the lesion (0.5–1 cc per 2 cm2) are highly effective in managing recalcitrant thickened lesions such as those seen in hypertrophic LP and palmoplantar LP.6 This treatment is particularly beneficial when lesions are unresponsive to topical therapies. Administered every 3 to 6 weeks, these injections provide rapid symptom relief, typically within 72 hours,6 while also contributing to the reduction of lesion size and thickness over time. The concentration of triamcinolone acetonide should be selected based on the lesion’s severity, with higher concentrations reserved for thicker, more resistant lesions. More frequent injections may be warranted in cases in which rapid lesion reduction is necessary, while less frequent sessions may suffice for maintenance therapy. It is important to follow patients closely for adverse effects, such as signs of local skin atrophy or hypopigmentation, and to adjust the dose or frequency accordingly. To mitigate these risks, consider using the lowest effective concentration and rotating injection sites if treating multiple lesions. Additionally, combining intralesional corticosteroids with topical therapies can enhance outcomes, particularly in cases in which monotherapy is insufficient.

Patients should be monitored vigilantly for complications of LP. The risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is a particular concern for patients with skin of color. Other complications of untreated LP include nail deformities and scarring alopecia.9 Regular and thorough follow-ups every few months to monitor scalp, mucosal, and genital involvement are essential to manage this risk effectively.

Furthermore, patient education is key. Informing patients and their caregivers about the nature of LP, the available treatment options, and the importance of ongoing follow-up can help to enhance treatment adherence and improve overall outcomes.

- Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. Lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:723-732. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1103641

- Handa S, Sahoo B. Childhood lichen planus: a study of 87 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:423-427. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01522.x

- George J, Murray T, Bain M. Generalized, eruptive lichen planus in a pediatric patient. Contemp Pediatr. 2022;39:32-34.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 1, 2023. Accessed August 12, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526126/

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2015.04.001

- Mutalik SD, Belgaumkar VA, Rasal YD. Current perspectives in the treatment of childhood lichen planus. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2021;22:316-325. doi:10.4103/ijpd.ijpd_165_20

- Usatine RP, Tinitigan M. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen planus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:53-60.

- Thomas LW, Elsensohn A, Bergheim T, et al. Intramuscular steroids in the treatment of dermatologic disease: a systematic review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:323-329.

- Gorouhi F, Davari P, Fazel N. Cutaneous and mucosal lichen planus: a comprehensive review of clinical subtypes, risk factors, diagnosis, and prognosis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:742826. doi:10.1155/2014/742826

Practice Gap

Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory cutaneous disorder. Although it often is characterized by the 6 Ps—pruritic, polygonal, planar, purple, papules, and plaques with a predilection for the wrists and ankles—the presentation can vary in morphology and distribution.1-5 With an incidence of approximately 1% in the general population, LP is undoubtedly uncommon.1 Its prevalence in the pediatric population is especially low, with only 2% to 3% of cases manifesting in individuals younger than 20 years.2

Generalized LP (also referred to as eruptive or exanthematous LP) is a rarely reported clinical subtype in which lesions are disseminated or spread rapidly.5 The rarity of generalized LP in children often leads to misdiagnosis or delayed treatment, impacting the patient’s quality of life. Thus, there is a need for heightened awareness among clinicians on the variable presentation of LP in the pediatric population. Incorporating a punch biopsy for the diagnosis of LP when lesions manifest as widespread, erythematous to violaceous, flat-topped papules or plaques, along with the addition of an intramuscular (IM) injection in the treatment plan, improves overall patient outcomes.

Tools and Techniques

A detailed physical examination followed by a punch biopsy was critical for the diagnosis of generalized LP in a 7-year-old Black girl. The examination revealed a widespread distribution of dark, violaceous, polygonal, shiny, flat-topped, firm papules coalescing into plaques across the entire body, with a greater predilection for the legs and overlying joints (Figure, A). Some lesions exhibited fine, silver-white, reticular patterns consistent with Wickham striae. Notably, there was no involvement of the scalp, nails, or mucosal surfaces.

The patient had no relevant medical or family history of skin disease and no recent history of illness. She previously was treated by a pediatrician with triamcinolone cream 0.1%, a course of oral cephalexin, and oral cetirizine 10 mg once daily without relief of symptoms.

Although the clinical presentation was consistent with LP, the differential diagnosis included lichen simplex chronicus, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and generalized granuloma annulare. To address the need for early recognition of LP in pediatric patients, a punch biopsy of a lesion on the left anterior thigh was performed and showed lichenoid interface dermatitis—a pivotal finding in distinguishing LP from other conditions in the differential.

Given the patient’s age and severity of the LP, a combination of topical and systemic therapies was prescribed—clobetasol cream 0.025% twice daily and 1 injection of 0.5 cc of IM triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg/mL. This regimen was guided by the efficacy of IM injections in providing prompt symptomatic relief, particularly for patients with extensive disease or for those whose condition is refractory to topical treatments.6 Our patient achieved remarkable improvement at 2-week follow-up (Figure, B), without any observed adverse effects. At that time, the patient’s mother refused further systemic treatment and opted for only the topical therapy as well as natural light therapy.

Practice Implications

Timely and accurate diagnosis of LP in pediatric patients, especially those with skin of color, is crucial. Early intervention is especially important in mitigating the risk for chronic symptoms and preventing potential scarring, which tends to be more pronounced and challenging to treat in individuals with darker skin tones.7 Although not present in our patient, it is important to note that LP can affect the face (including the eyelids) as well as the palms and soles in pediatric patients with skin of color.

The most common approach to management of pediatric LP involves the use of a topical corticosteroid and an oral antihistamine, but the recalcitrant and generalized distribution of lesions warrants the administration of a systemic corticosteroid regardless of the patient’s age.6 In our patient, prompt administration of low-dose IM triamcinolone was both crucial and beneficial. Although an underutilized approach, IM triamcinolone helps to prevent the progression of lesions to the scalp, nails, and mucosa while also reducing inflammation and pruritus in glabrous skin.8

Triamcinolone acetonide injections—administered at concentrations of 5 to 40 mg/mL—directly into the lesion (0.5–1 cc per 2 cm2) are highly effective in managing recalcitrant thickened lesions such as those seen in hypertrophic LP and palmoplantar LP.6 This treatment is particularly beneficial when lesions are unresponsive to topical therapies. Administered every 3 to 6 weeks, these injections provide rapid symptom relief, typically within 72 hours,6 while also contributing to the reduction of lesion size and thickness over time. The concentration of triamcinolone acetonide should be selected based on the lesion’s severity, with higher concentrations reserved for thicker, more resistant lesions. More frequent injections may be warranted in cases in which rapid lesion reduction is necessary, while less frequent sessions may suffice for maintenance therapy. It is important to follow patients closely for adverse effects, such as signs of local skin atrophy or hypopigmentation, and to adjust the dose or frequency accordingly. To mitigate these risks, consider using the lowest effective concentration and rotating injection sites if treating multiple lesions. Additionally, combining intralesional corticosteroids with topical therapies can enhance outcomes, particularly in cases in which monotherapy is insufficient.

Patients should be monitored vigilantly for complications of LP. The risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is a particular concern for patients with skin of color. Other complications of untreated LP include nail deformities and scarring alopecia.9 Regular and thorough follow-ups every few months to monitor scalp, mucosal, and genital involvement are essential to manage this risk effectively.

Furthermore, patient education is key. Informing patients and their caregivers about the nature of LP, the available treatment options, and the importance of ongoing follow-up can help to enhance treatment adherence and improve overall outcomes.

Practice Gap

Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory cutaneous disorder. Although it often is characterized by the 6 Ps—pruritic, polygonal, planar, purple, papules, and plaques with a predilection for the wrists and ankles—the presentation can vary in morphology and distribution.1-5 With an incidence of approximately 1% in the general population, LP is undoubtedly uncommon.1 Its prevalence in the pediatric population is especially low, with only 2% to 3% of cases manifesting in individuals younger than 20 years.2

Generalized LP (also referred to as eruptive or exanthematous LP) is a rarely reported clinical subtype in which lesions are disseminated or spread rapidly.5 The rarity of generalized LP in children often leads to misdiagnosis or delayed treatment, impacting the patient’s quality of life. Thus, there is a need for heightened awareness among clinicians on the variable presentation of LP in the pediatric population. Incorporating a punch biopsy for the diagnosis of LP when lesions manifest as widespread, erythematous to violaceous, flat-topped papules or plaques, along with the addition of an intramuscular (IM) injection in the treatment plan, improves overall patient outcomes.

Tools and Techniques

A detailed physical examination followed by a punch biopsy was critical for the diagnosis of generalized LP in a 7-year-old Black girl. The examination revealed a widespread distribution of dark, violaceous, polygonal, shiny, flat-topped, firm papules coalescing into plaques across the entire body, with a greater predilection for the legs and overlying joints (Figure, A). Some lesions exhibited fine, silver-white, reticular patterns consistent with Wickham striae. Notably, there was no involvement of the scalp, nails, or mucosal surfaces.

The patient had no relevant medical or family history of skin disease and no recent history of illness. She previously was treated by a pediatrician with triamcinolone cream 0.1%, a course of oral cephalexin, and oral cetirizine 10 mg once daily without relief of symptoms.

Although the clinical presentation was consistent with LP, the differential diagnosis included lichen simplex chronicus, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and generalized granuloma annulare. To address the need for early recognition of LP in pediatric patients, a punch biopsy of a lesion on the left anterior thigh was performed and showed lichenoid interface dermatitis—a pivotal finding in distinguishing LP from other conditions in the differential.

Given the patient’s age and severity of the LP, a combination of topical and systemic therapies was prescribed—clobetasol cream 0.025% twice daily and 1 injection of 0.5 cc of IM triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg/mL. This regimen was guided by the efficacy of IM injections in providing prompt symptomatic relief, particularly for patients with extensive disease or for those whose condition is refractory to topical treatments.6 Our patient achieved remarkable improvement at 2-week follow-up (Figure, B), without any observed adverse effects. At that time, the patient’s mother refused further systemic treatment and opted for only the topical therapy as well as natural light therapy.

Practice Implications

Timely and accurate diagnosis of LP in pediatric patients, especially those with skin of color, is crucial. Early intervention is especially important in mitigating the risk for chronic symptoms and preventing potential scarring, which tends to be more pronounced and challenging to treat in individuals with darker skin tones.7 Although not present in our patient, it is important to note that LP can affect the face (including the eyelids) as well as the palms and soles in pediatric patients with skin of color.

The most common approach to management of pediatric LP involves the use of a topical corticosteroid and an oral antihistamine, but the recalcitrant and generalized distribution of lesions warrants the administration of a systemic corticosteroid regardless of the patient’s age.6 In our patient, prompt administration of low-dose IM triamcinolone was both crucial and beneficial. Although an underutilized approach, IM triamcinolone helps to prevent the progression of lesions to the scalp, nails, and mucosa while also reducing inflammation and pruritus in glabrous skin.8

Triamcinolone acetonide injections—administered at concentrations of 5 to 40 mg/mL—directly into the lesion (0.5–1 cc per 2 cm2) are highly effective in managing recalcitrant thickened lesions such as those seen in hypertrophic LP and palmoplantar LP.6 This treatment is particularly beneficial when lesions are unresponsive to topical therapies. Administered every 3 to 6 weeks, these injections provide rapid symptom relief, typically within 72 hours,6 while also contributing to the reduction of lesion size and thickness over time. The concentration of triamcinolone acetonide should be selected based on the lesion’s severity, with higher concentrations reserved for thicker, more resistant lesions. More frequent injections may be warranted in cases in which rapid lesion reduction is necessary, while less frequent sessions may suffice for maintenance therapy. It is important to follow patients closely for adverse effects, such as signs of local skin atrophy or hypopigmentation, and to adjust the dose or frequency accordingly. To mitigate these risks, consider using the lowest effective concentration and rotating injection sites if treating multiple lesions. Additionally, combining intralesional corticosteroids with topical therapies can enhance outcomes, particularly in cases in which monotherapy is insufficient.

Patients should be monitored vigilantly for complications of LP. The risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is a particular concern for patients with skin of color. Other complications of untreated LP include nail deformities and scarring alopecia.9 Regular and thorough follow-ups every few months to monitor scalp, mucosal, and genital involvement are essential to manage this risk effectively.

Furthermore, patient education is key. Informing patients and their caregivers about the nature of LP, the available treatment options, and the importance of ongoing follow-up can help to enhance treatment adherence and improve overall outcomes.

- Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. Lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:723-732. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1103641

- Handa S, Sahoo B. Childhood lichen planus: a study of 87 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:423-427. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01522.x

- George J, Murray T, Bain M. Generalized, eruptive lichen planus in a pediatric patient. Contemp Pediatr. 2022;39:32-34.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 1, 2023. Accessed August 12, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526126/

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2015.04.001

- Mutalik SD, Belgaumkar VA, Rasal YD. Current perspectives in the treatment of childhood lichen planus. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2021;22:316-325. doi:10.4103/ijpd.ijpd_165_20

- Usatine RP, Tinitigan M. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen planus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:53-60.

- Thomas LW, Elsensohn A, Bergheim T, et al. Intramuscular steroids in the treatment of dermatologic disease: a systematic review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:323-329.

- Gorouhi F, Davari P, Fazel N. Cutaneous and mucosal lichen planus: a comprehensive review of clinical subtypes, risk factors, diagnosis, and prognosis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:742826. doi:10.1155/2014/742826

- Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Clinical practice. Lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:723-732. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1103641

- Handa S, Sahoo B. Childhood lichen planus: a study of 87 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:423-427. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01522.x

- George J, Murray T, Bain M. Generalized, eruptive lichen planus in a pediatric patient. Contemp Pediatr. 2022;39:32-34.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 1, 2023. Accessed August 12, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526126/

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2015.04.001

- Mutalik SD, Belgaumkar VA, Rasal YD. Current perspectives in the treatment of childhood lichen planus. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2021;22:316-325. doi:10.4103/ijpd.ijpd_165_20

- Usatine RP, Tinitigan M. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen planus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:53-60.

- Thomas LW, Elsensohn A, Bergheim T, et al. Intramuscular steroids in the treatment of dermatologic disease: a systematic review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:323-329.

- Gorouhi F, Davari P, Fazel N. Cutaneous and mucosal lichen planus: a comprehensive review of clinical subtypes, risk factors, diagnosis, and prognosis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:742826. doi:10.1155/2014/742826

Customized Dermal Curette: An Alternative and Effective Shaving Tool in Nail Surgery

Practice Gap

Longitudinal melanonychia (LM) is characterized by the presence of a dark brown, longitudinal, pigmented band on the nail unit, often caused by melanocytic activation or melanocytic hyperplasia in the nail matrix. Distinguishing between benign and early malignant LM is crucial due to their similar clinical presentations.1 Hence, surgical excision of the pigmented nail matrix followed by histopathologic examination is a common procedure aimed at managing LM and reducing the risk for delayed diagnosis of subungual melanoma.

Tangential matrix excision combined with the nail window technique has emerged as a common and favored surgical strategy for managing LM.2 This method is highly valued for its ability to minimize the risk for severe permanent nail dystrophy and effectively reduce postsurgical pigmentation recurrence.

The procedure begins with the creation of a matrix window along the lateral edge of the pigmented band followed by 1 lateral incision carefully made on each side of the nail fold. This meticulous approach allows for the complete exposure of the pigmented lesion. Subsequently, the nail fold is separated from the dorsal surface of the nail plate to facilitate access to the pigmented nail matrix. Finally, the target pigmented area is excised using a scalpel.

Despite the recognized efficacy of this procedure, challenges do arise, particularly when the width of the pigmented matrix lesion is narrow. Holding the scalpel horizontally to ensure precise excision can prove to be demanding, leading to difficulty achieving complete lesion removal and obtaining the desired cosmetic outcomes. As such, there is a clear need to explore alternative tools that can effectively address these challenges while ensuring optimal surgical outcomes for patients with LM. We propose the use of the customized dermal curette.

The Technique

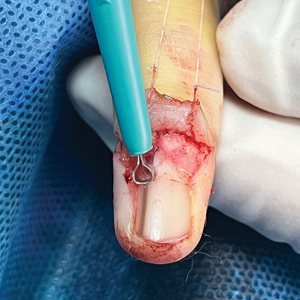

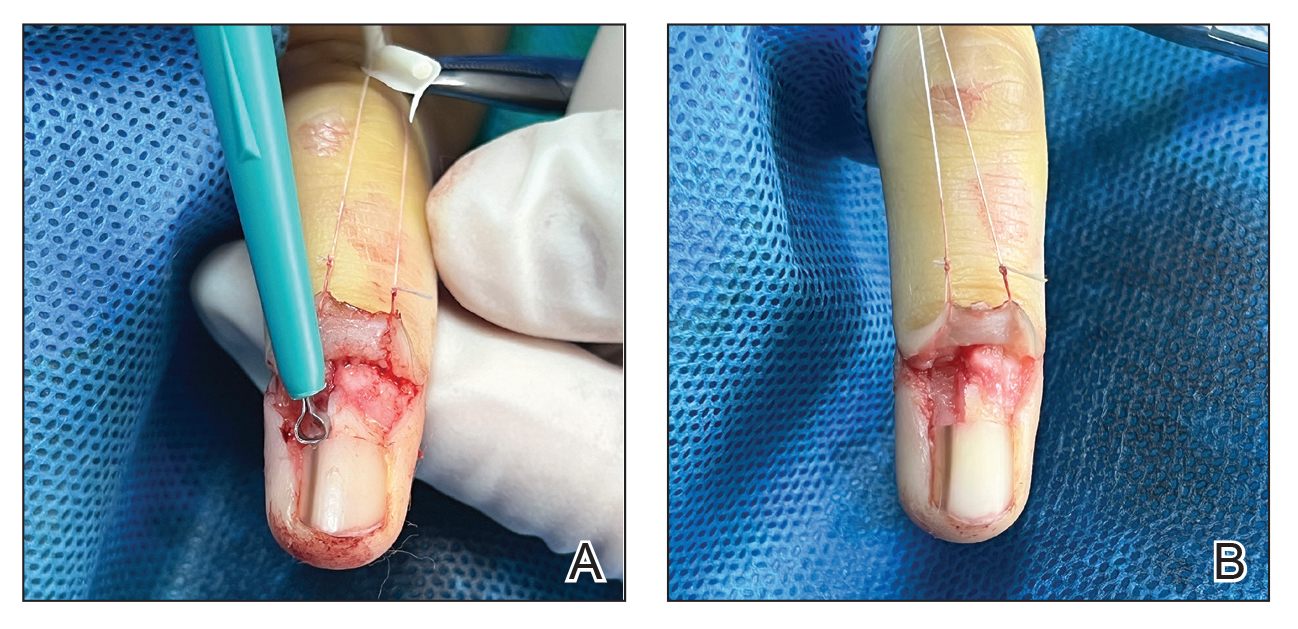

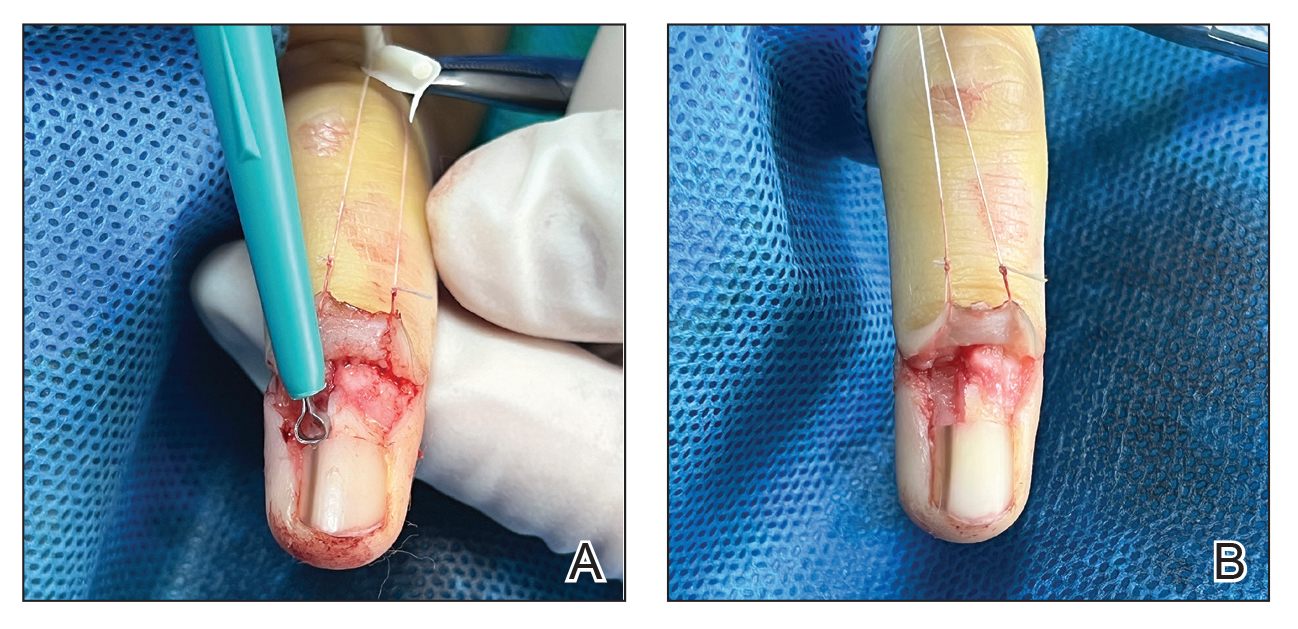

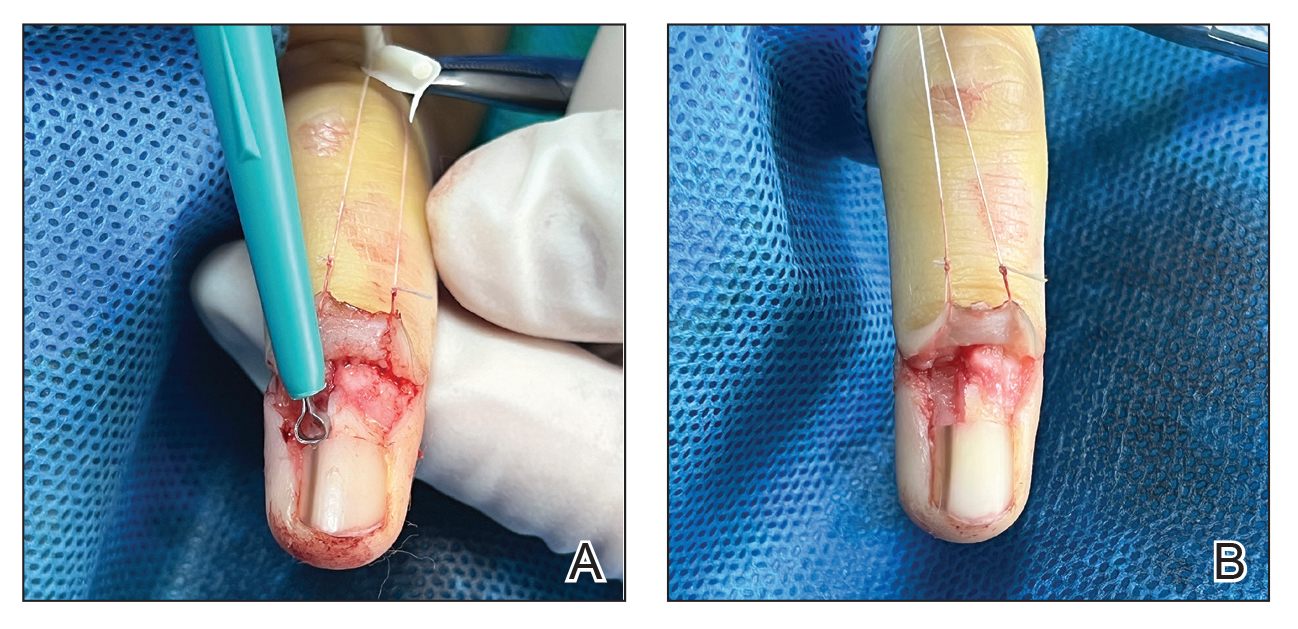

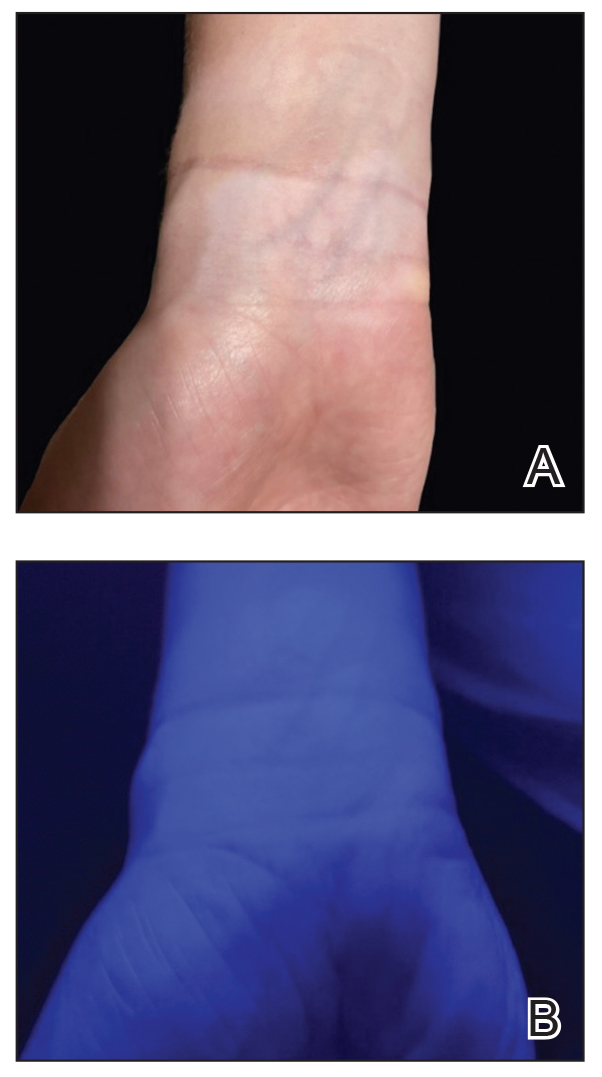

An improved curette tool is a practical solution for complete removal of the pigmented nail matrix. This enhanced instrument is crafted from a sterile disposable dermal curette with its top flattened using a needle holder(Figure 1). Termed the customized dermal curette, this device is a simple yet accurate tool for the precise excision of pigmented lesions within the nail matrix. Importantly, it offers versatility by accommodating different widths of pigmented lesions through the availability of various sizes of dermal curettes (Figure 2).

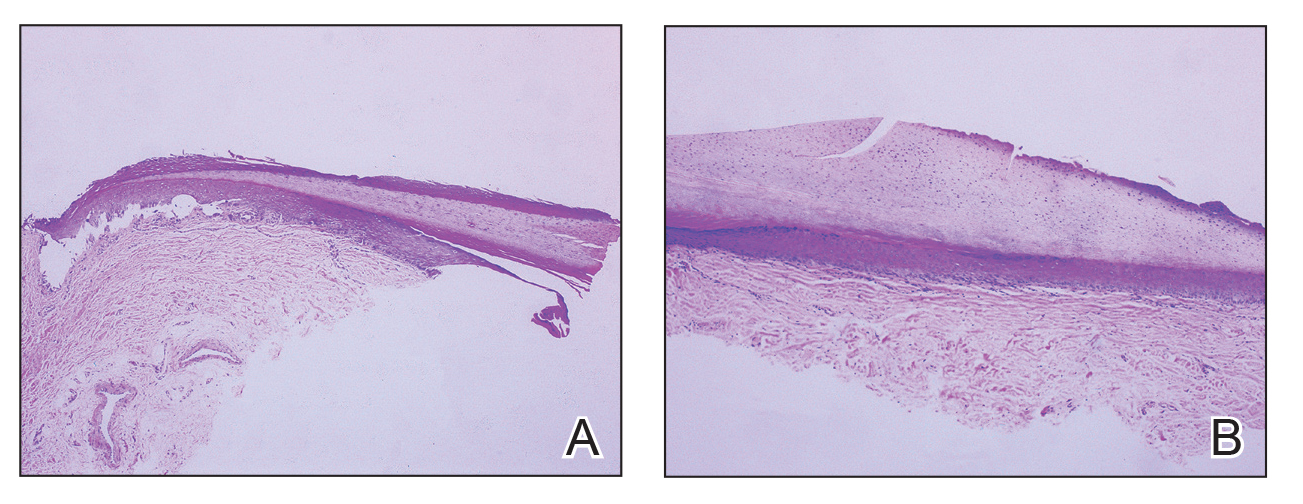

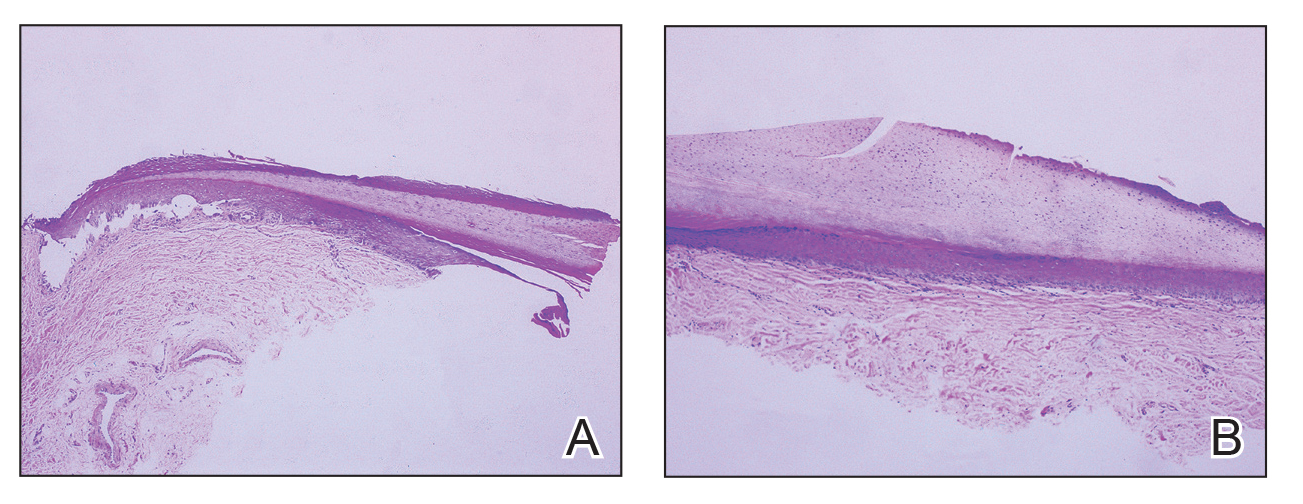

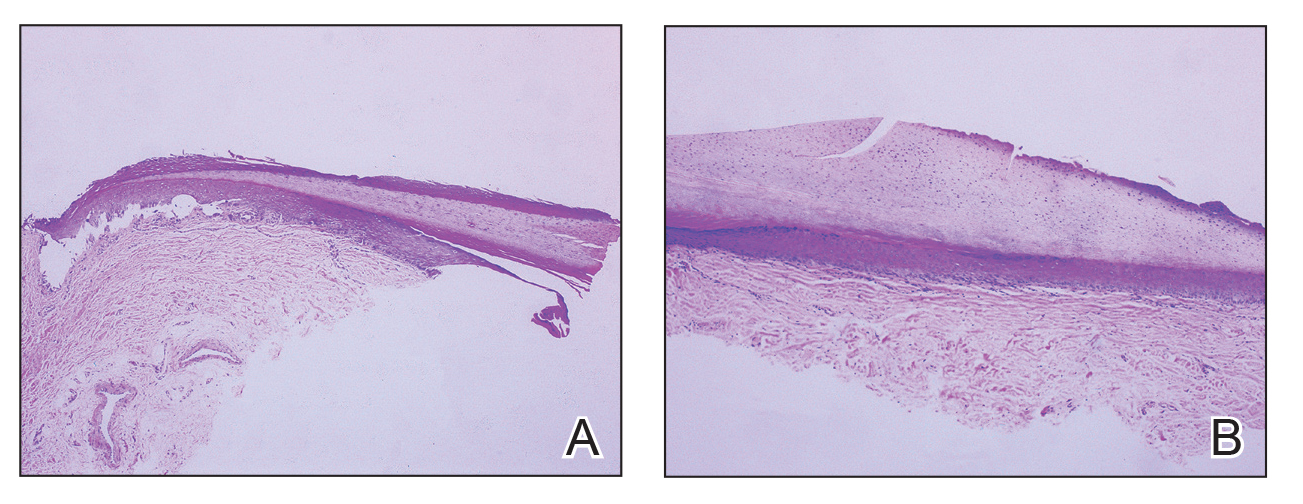

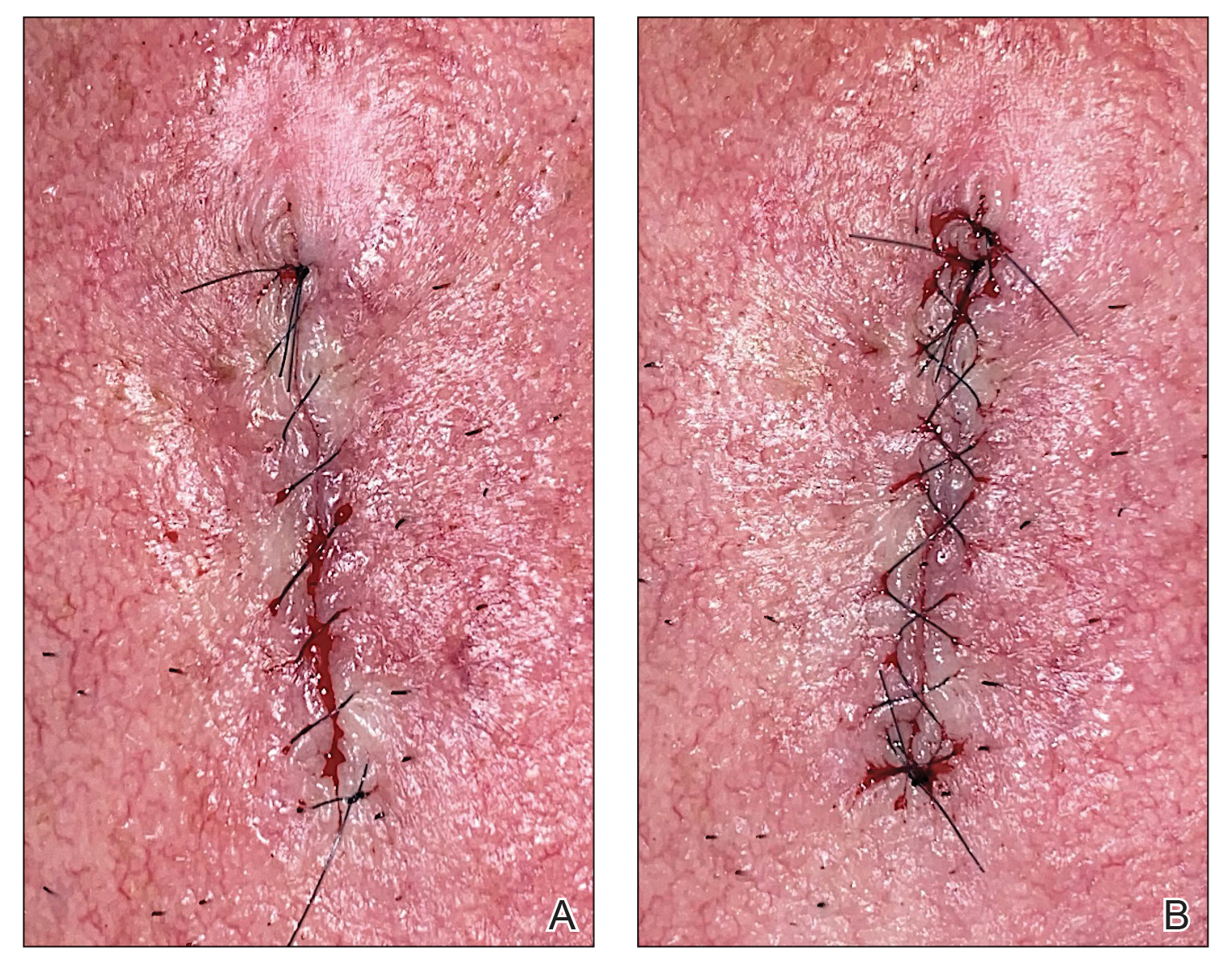

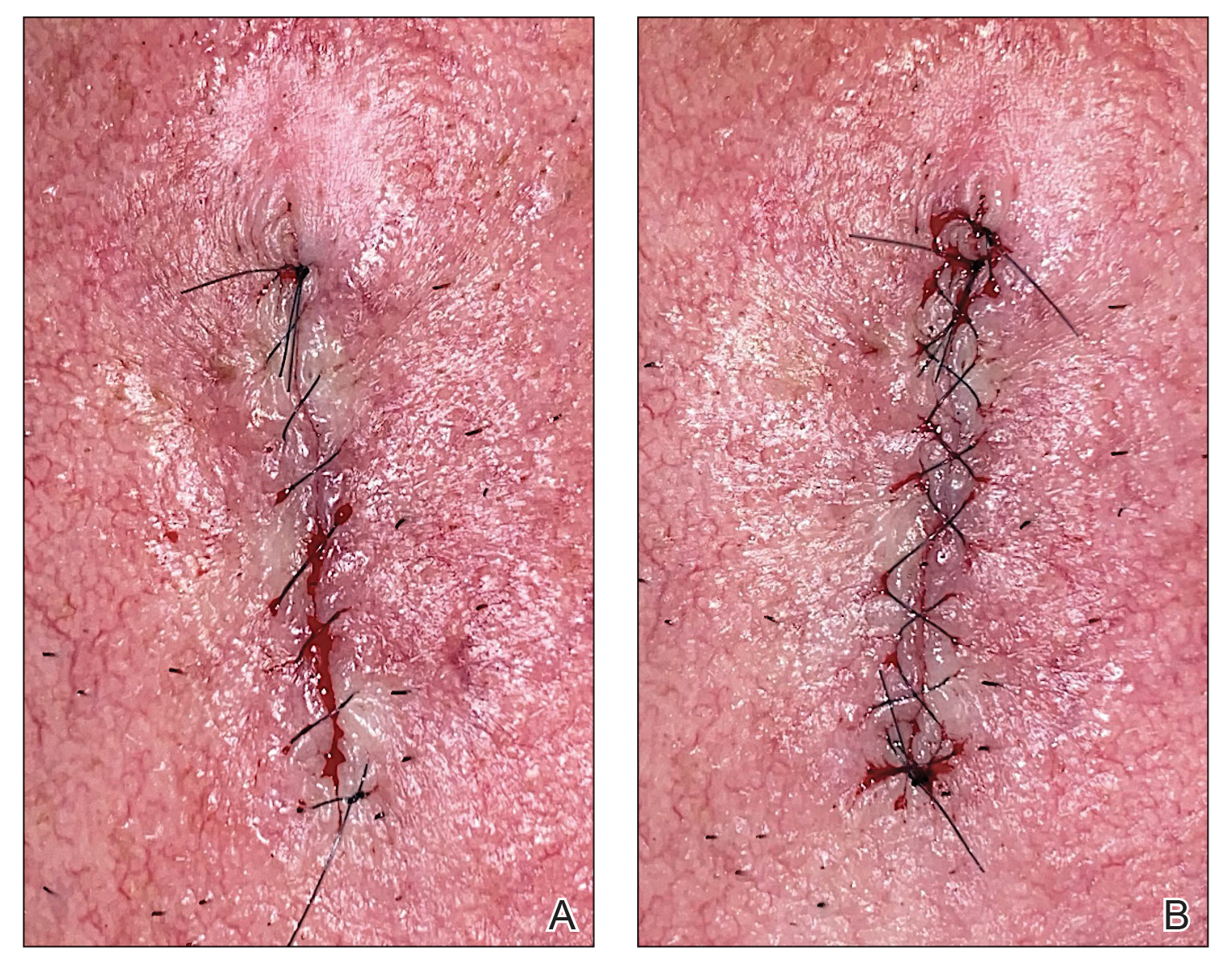

Histopathologically, we have found that the scalpel technique may lead to variable tissue removal, resulting in differences in tissue thickness, fragility, and completeness (Figure 3A). Conversely, the customized dermal curette consistently provides more accurate tissue excision, resulting in uniform tissue thickness and integrity (Figure 3B).

Practice Implications

Compared to the traditional scalpel, this modified tool offers distinct advantages. Specifically, the customized dermal curette provides enhanced maneuverability and control during the procedure, thereby improving the overall efficacy of the excision process. It also offers a more accurate approach to completely remove pigmented bands, which reduces the risk for postoperative recurrence. The simplicity, affordability, and ease of operation associated with customized dermal curettes holds promise as an effective alternative for tissue shaving, especially in cases involving narrow pigmented matrix lesions, thereby addressing a notable practice gap and enhancing patient care.

- Tan WC, Wang DY, Seghers AC, et al. Should we biopsy melanonychia striata in Asian children? a retrospective observational study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:864-868. doi:10.1111/pde.13934

- Zhou Y, Chen W, Liu ZR, et al. Modified shave surgery combined with nail window technique for the treatment of longitudinal melanonychia: evaluation of the method on a series of 67 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:717-722. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.065

Practice Gap

Longitudinal melanonychia (LM) is characterized by the presence of a dark brown, longitudinal, pigmented band on the nail unit, often caused by melanocytic activation or melanocytic hyperplasia in the nail matrix. Distinguishing between benign and early malignant LM is crucial due to their similar clinical presentations.1 Hence, surgical excision of the pigmented nail matrix followed by histopathologic examination is a common procedure aimed at managing LM and reducing the risk for delayed diagnosis of subungual melanoma.

Tangential matrix excision combined with the nail window technique has emerged as a common and favored surgical strategy for managing LM.2 This method is highly valued for its ability to minimize the risk for severe permanent nail dystrophy and effectively reduce postsurgical pigmentation recurrence.

The procedure begins with the creation of a matrix window along the lateral edge of the pigmented band followed by 1 lateral incision carefully made on each side of the nail fold. This meticulous approach allows for the complete exposure of the pigmented lesion. Subsequently, the nail fold is separated from the dorsal surface of the nail plate to facilitate access to the pigmented nail matrix. Finally, the target pigmented area is excised using a scalpel.

Despite the recognized efficacy of this procedure, challenges do arise, particularly when the width of the pigmented matrix lesion is narrow. Holding the scalpel horizontally to ensure precise excision can prove to be demanding, leading to difficulty achieving complete lesion removal and obtaining the desired cosmetic outcomes. As such, there is a clear need to explore alternative tools that can effectively address these challenges while ensuring optimal surgical outcomes for patients with LM. We propose the use of the customized dermal curette.

The Technique

An improved curette tool is a practical solution for complete removal of the pigmented nail matrix. This enhanced instrument is crafted from a sterile disposable dermal curette with its top flattened using a needle holder(Figure 1). Termed the customized dermal curette, this device is a simple yet accurate tool for the precise excision of pigmented lesions within the nail matrix. Importantly, it offers versatility by accommodating different widths of pigmented lesions through the availability of various sizes of dermal curettes (Figure 2).

Histopathologically, we have found that the scalpel technique may lead to variable tissue removal, resulting in differences in tissue thickness, fragility, and completeness (Figure 3A). Conversely, the customized dermal curette consistently provides more accurate tissue excision, resulting in uniform tissue thickness and integrity (Figure 3B).

Practice Implications

Compared to the traditional scalpel, this modified tool offers distinct advantages. Specifically, the customized dermal curette provides enhanced maneuverability and control during the procedure, thereby improving the overall efficacy of the excision process. It also offers a more accurate approach to completely remove pigmented bands, which reduces the risk for postoperative recurrence. The simplicity, affordability, and ease of operation associated with customized dermal curettes holds promise as an effective alternative for tissue shaving, especially in cases involving narrow pigmented matrix lesions, thereby addressing a notable practice gap and enhancing patient care.

Practice Gap

Longitudinal melanonychia (LM) is characterized by the presence of a dark brown, longitudinal, pigmented band on the nail unit, often caused by melanocytic activation or melanocytic hyperplasia in the nail matrix. Distinguishing between benign and early malignant LM is crucial due to their similar clinical presentations.1 Hence, surgical excision of the pigmented nail matrix followed by histopathologic examination is a common procedure aimed at managing LM and reducing the risk for delayed diagnosis of subungual melanoma.

Tangential matrix excision combined with the nail window technique has emerged as a common and favored surgical strategy for managing LM.2 This method is highly valued for its ability to minimize the risk for severe permanent nail dystrophy and effectively reduce postsurgical pigmentation recurrence.

The procedure begins with the creation of a matrix window along the lateral edge of the pigmented band followed by 1 lateral incision carefully made on each side of the nail fold. This meticulous approach allows for the complete exposure of the pigmented lesion. Subsequently, the nail fold is separated from the dorsal surface of the nail plate to facilitate access to the pigmented nail matrix. Finally, the target pigmented area is excised using a scalpel.

Despite the recognized efficacy of this procedure, challenges do arise, particularly when the width of the pigmented matrix lesion is narrow. Holding the scalpel horizontally to ensure precise excision can prove to be demanding, leading to difficulty achieving complete lesion removal and obtaining the desired cosmetic outcomes. As such, there is a clear need to explore alternative tools that can effectively address these challenges while ensuring optimal surgical outcomes for patients with LM. We propose the use of the customized dermal curette.

The Technique

An improved curette tool is a practical solution for complete removal of the pigmented nail matrix. This enhanced instrument is crafted from a sterile disposable dermal curette with its top flattened using a needle holder(Figure 1). Termed the customized dermal curette, this device is a simple yet accurate tool for the precise excision of pigmented lesions within the nail matrix. Importantly, it offers versatility by accommodating different widths of pigmented lesions through the availability of various sizes of dermal curettes (Figure 2).

Histopathologically, we have found that the scalpel technique may lead to variable tissue removal, resulting in differences in tissue thickness, fragility, and completeness (Figure 3A). Conversely, the customized dermal curette consistently provides more accurate tissue excision, resulting in uniform tissue thickness and integrity (Figure 3B).

Practice Implications

Compared to the traditional scalpel, this modified tool offers distinct advantages. Specifically, the customized dermal curette provides enhanced maneuverability and control during the procedure, thereby improving the overall efficacy of the excision process. It also offers a more accurate approach to completely remove pigmented bands, which reduces the risk for postoperative recurrence. The simplicity, affordability, and ease of operation associated with customized dermal curettes holds promise as an effective alternative for tissue shaving, especially in cases involving narrow pigmented matrix lesions, thereby addressing a notable practice gap and enhancing patient care.

- Tan WC, Wang DY, Seghers AC, et al. Should we biopsy melanonychia striata in Asian children? a retrospective observational study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:864-868. doi:10.1111/pde.13934

- Zhou Y, Chen W, Liu ZR, et al. Modified shave surgery combined with nail window technique for the treatment of longitudinal melanonychia: evaluation of the method on a series of 67 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:717-722. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.065

- Tan WC, Wang DY, Seghers AC, et al. Should we biopsy melanonychia striata in Asian children? a retrospective observational study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:864-868. doi:10.1111/pde.13934

- Zhou Y, Chen W, Liu ZR, et al. Modified shave surgery combined with nail window technique for the treatment of longitudinal melanonychia: evaluation of the method on a series of 67 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:717-722. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.065

Two Techniques to Avoid Cyst Spray During Excision

Practice Gap

Epidermoid cysts are asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, mobile, subcutaneous masses that elevate the skin. Also known as epidermal, keratin, or infundibular cysts, epidermoid cysts are caused by proliferation of surface epidermoid cells within the dermis and can arise anywhere on the body, most commonly on the face, neck, and trunk.1 Cutaneous cysts often contain fluid or semifluid contents and can be aesthetically displeasing or cause mild pain, prompting patients to seek removal. Definitive treatment of epidermoid cysts is complete surgical removal,2 which can be performed in office in a sterile or clean manner by either dermatologists or primary care providers.

Prior to incision, a local anesthetic—commonly lidocaine with epinephrine—is injected in the region surrounding the cyst sac so as not to rupture the cyst wall. Maintaining the cyst wall throughout the procedure ensures total cyst removal and minimizes the risk for recurrence. However, it often is difficult to approximate the cyst border because it cannot be visualized prior to incision.

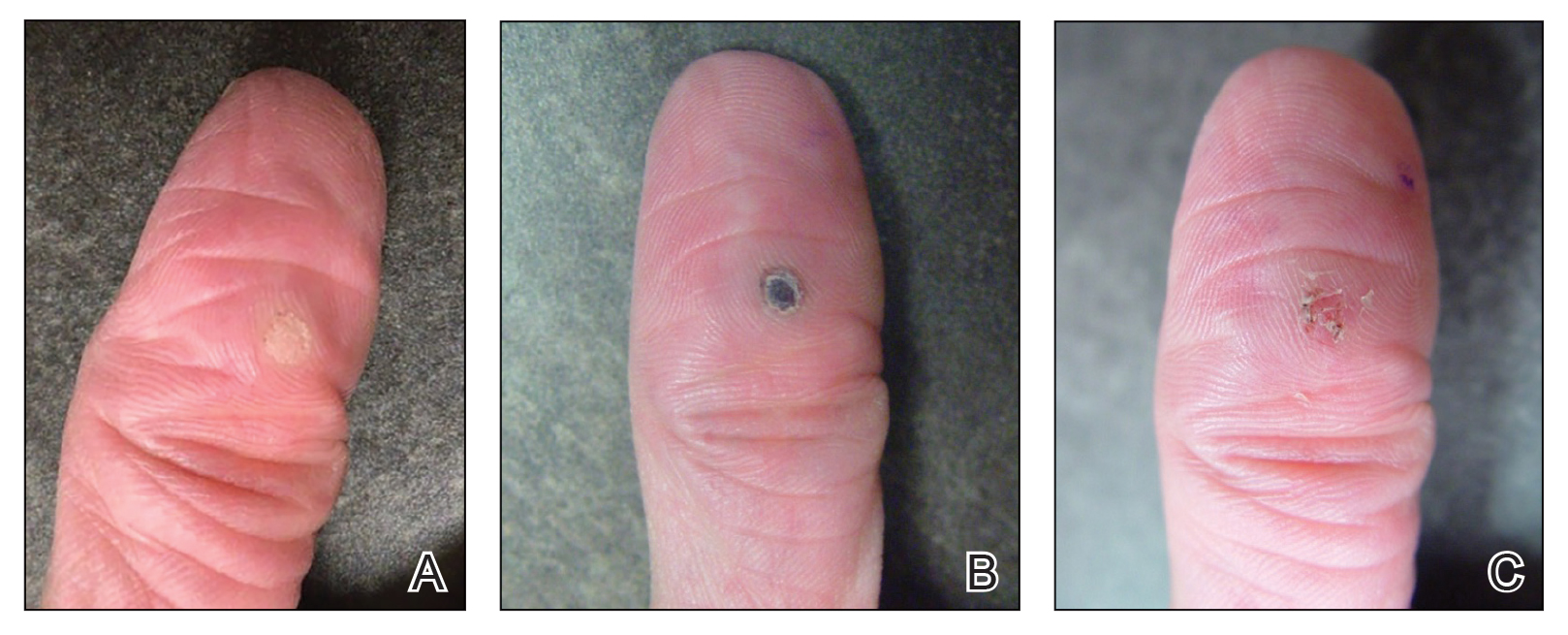

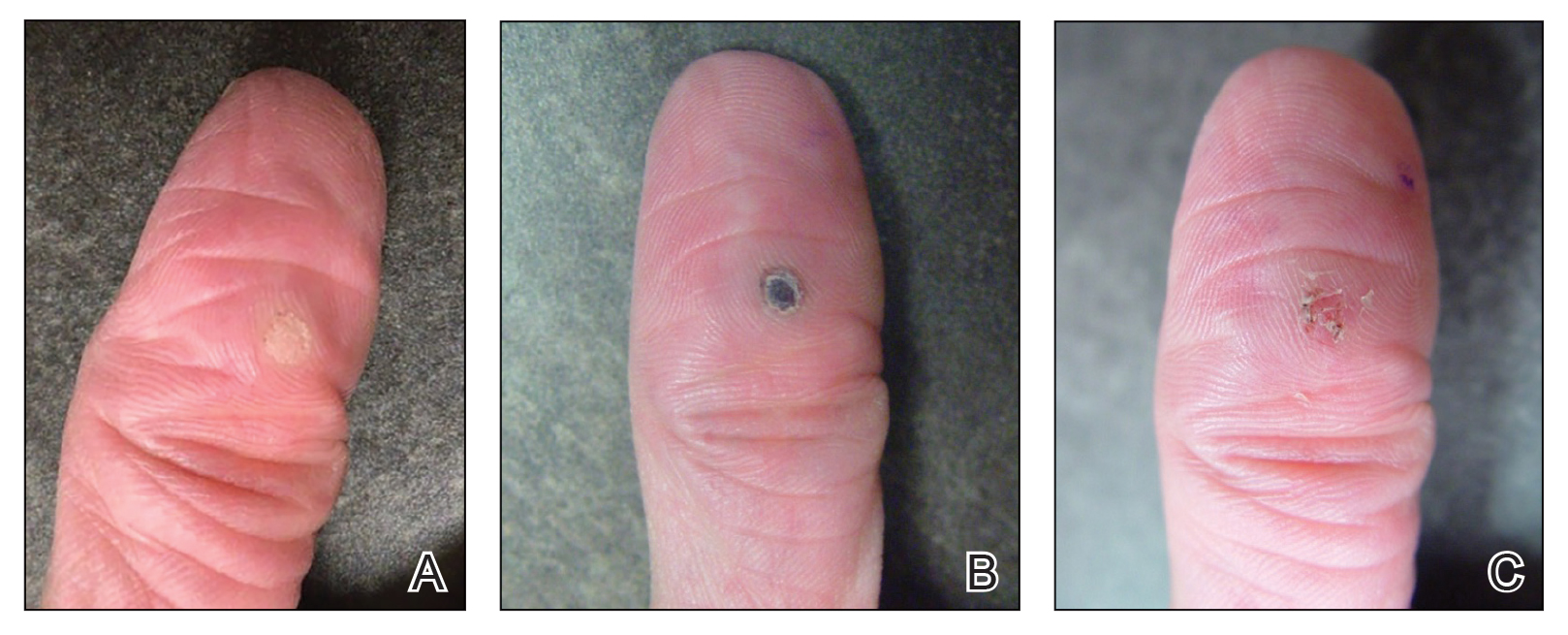

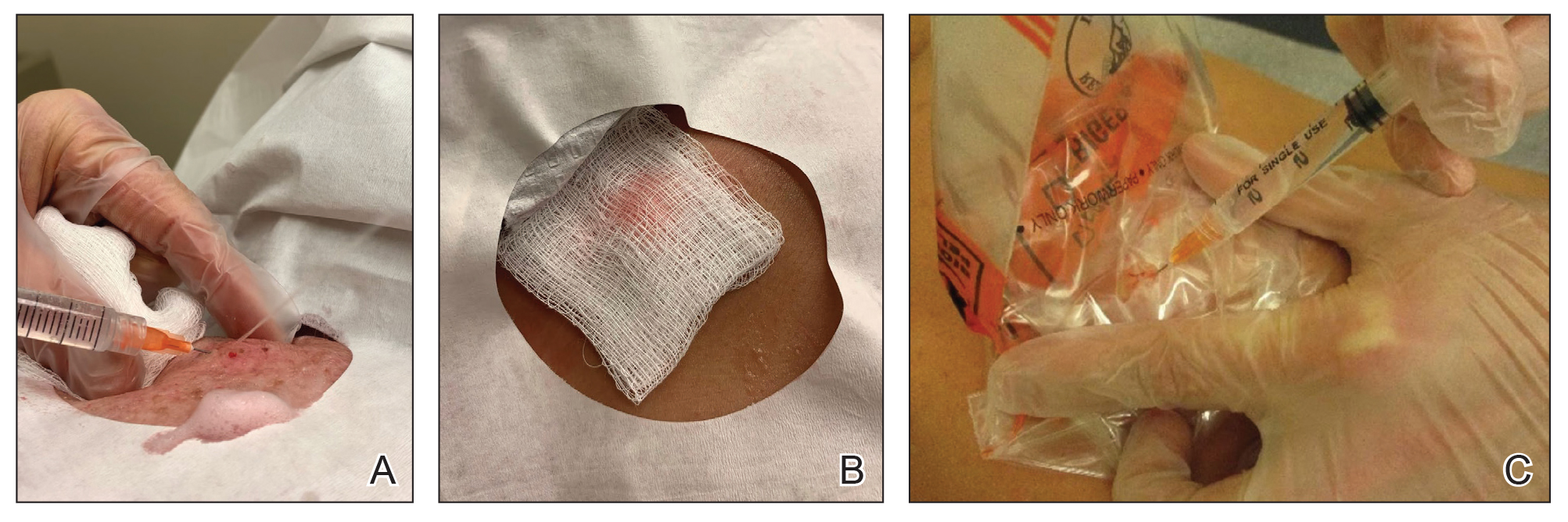

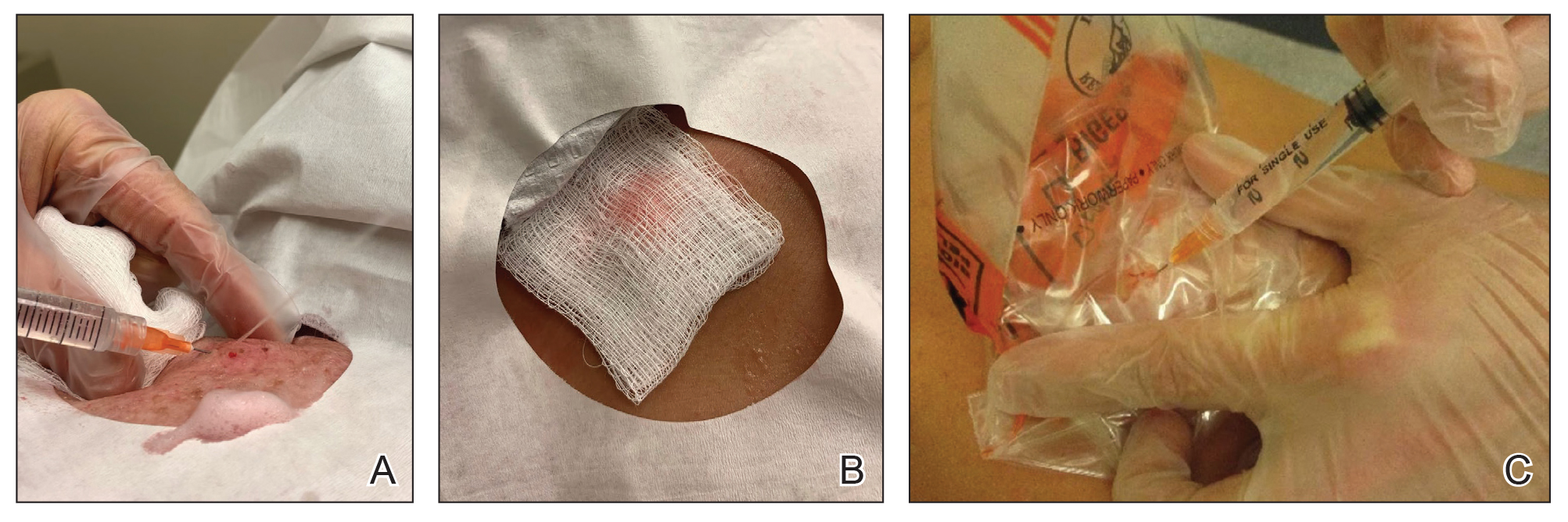

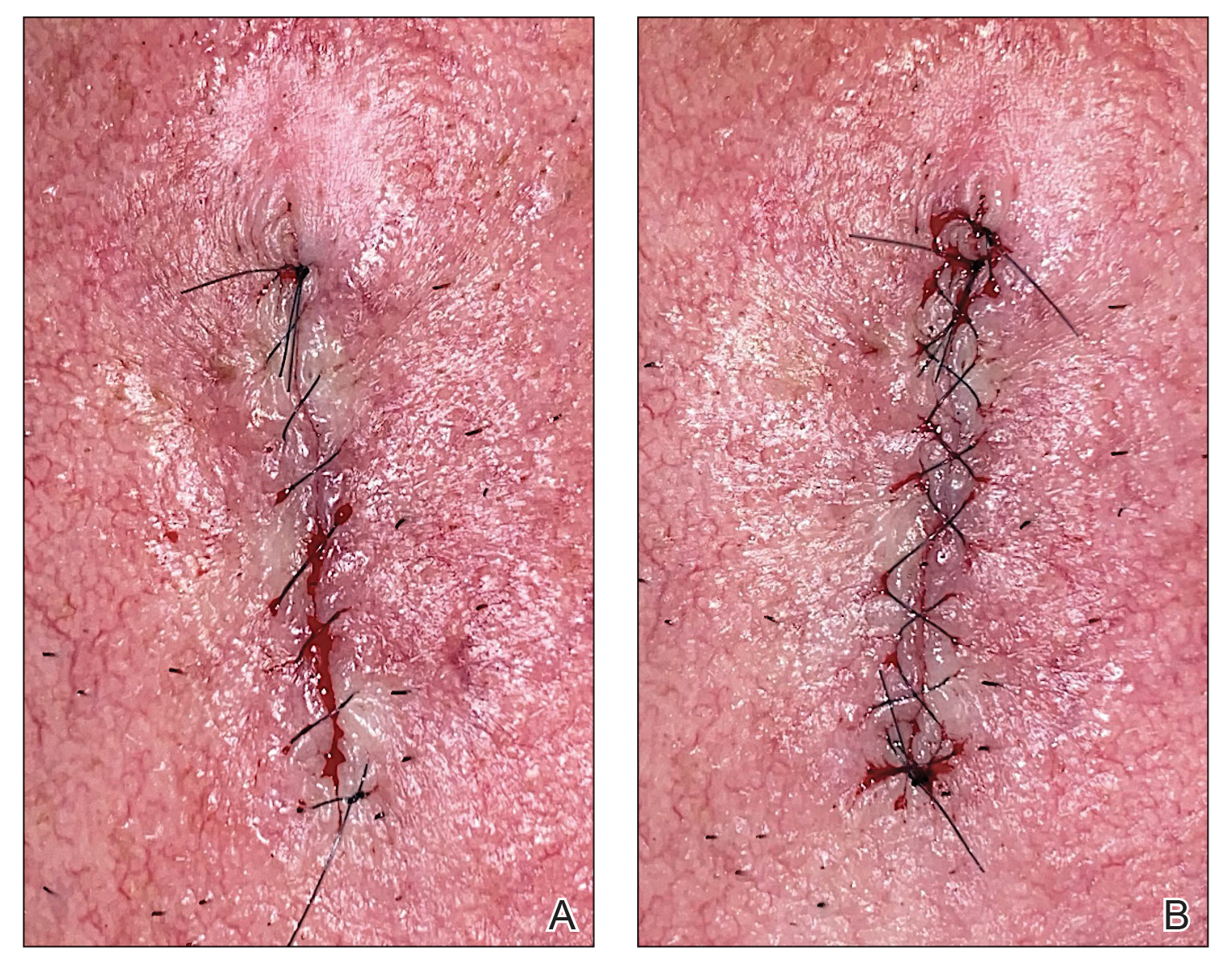

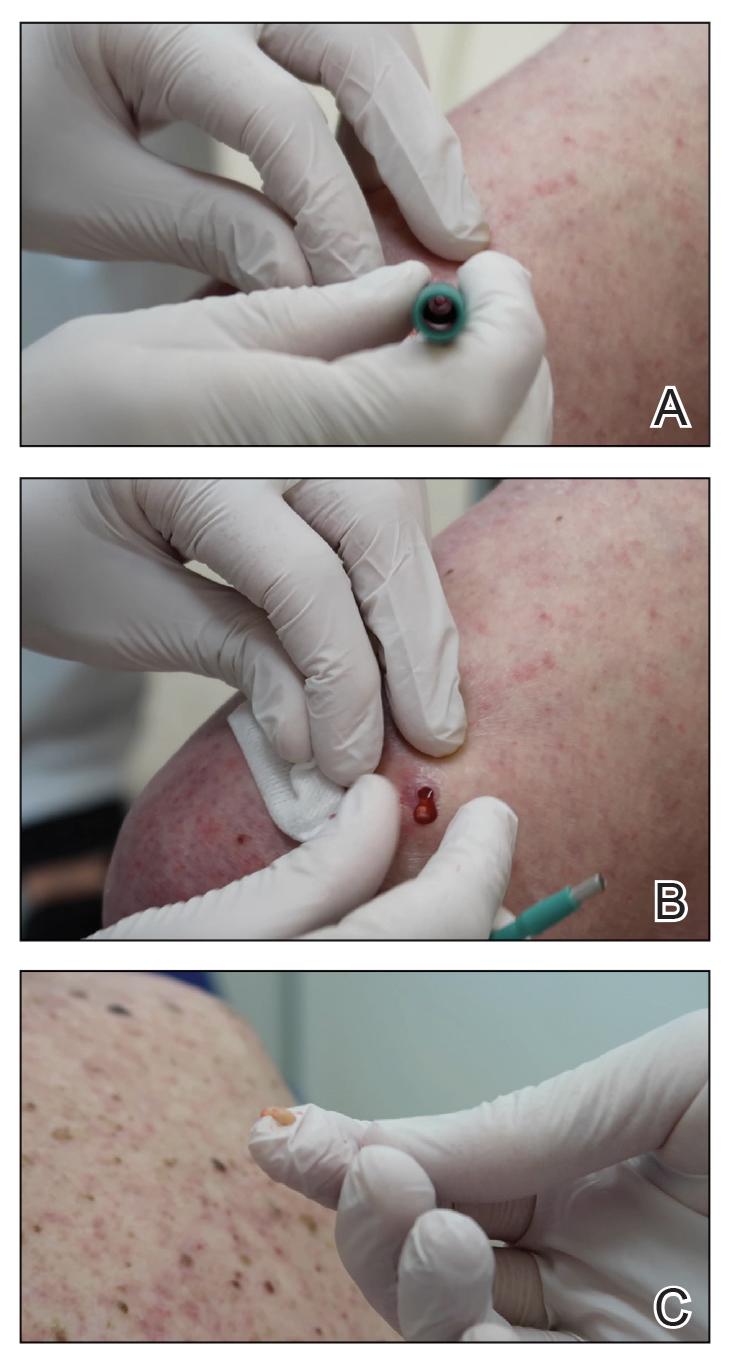

Throughout the duration of the procedure, cyst contents may suddenly spray out of the area and pose a risk to providers and their staff (Figure, A). Even with careful application around the periphery, either puncture or pericystic anesthesia between the cyst wall and the dermis can lead to splatter. Larger and wider peripheral anesthesia may not be possible given a shortage of lidocaine and a desire to minimize injection. Even with meticulous use of personal protective equipment in cutaneous surgery, infectious organisms found in ruptured cysts and abscesses may spray the surgical field.3 Therefore, it is in our best interest to minimize the trajectory of cyst spray contents.

The Tools

We have employed 2 simple techniques using equipment normally found on a standard surgical tray for easy safe injection of cysts. Supplies needed include 4×4-inch gauze pads, alcohol and chlorhexidine, a marker, all instruments necessary for cyst excision, and a small clear biohazard bag.

The Technique

Prior to covering the cyst, care is taken to locate the cyst opening. At times, a comedo or punctum can be seen overlying the cyst bulge. We mark the lumen and cyst opening with a surgical marker. If the pore is not easily identified, we draw an 8-mm circle around the mound of the cyst.

One option is to apply a gauze pad over the cyst to allow for stabilization of the surgical field and blanket the area from splatter (Figure, B). Then we cover the cyst using antiseptic-soaked gauze as a protective barrier to avoid potentially contaminated spray. This tool can be constructed from a 4×4-inch gauze pad with the addition of alcohol and chlorhexidine. When the cyst is covered, the surgeon can inject the lesion and surrounding tissue without biohazard splatter.

Another method is to cover the cyst with a small clear biohazard bag (Figure, C). When injecting anesthetic through the bag, the spray is captured by the bag and does not reach the surgeon or staff. This method is potentially more effective given that the cyst can still be visualized fully for more accurate injection.

Practice Implications

Outpatient surgical excision is a common effective procedure for epidermoid cysts. However, it is not uncommon for cyst contents to spray during the injection of anesthetic, posing a nuisance to the surgeon, health care staff, and patient. The technique of covering the lesion with antiseptic-soaked gauze or a small clear biohazard bag prevents cyst contents from spraying and reduces risk for contamination. In addition to these protective benefits, the use of readily available items replaces the need to order a splatter control shield.

Limitations—Although we seldom see spray using our technique, covering the cyst with gauze may disguise the region of interest and interfere with accurate incision. Marking the lesion prior to anesthesia administration or using a clear biohazard bag minimizes difficulty visualizing the cyst opening.

- Zito PM, Scharf R. Epidermoid cyst. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed June 13, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499974

- Weir CB, St. Hilaire NJ. Epidermal inclusion cyst. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed June3, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532310/

- Kuniyuki S, Yoshida Y, Maekawa N, et al. Bacteriological study of epidermal cysts. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;88:23-25. doi:10.2340/00015555-0348

Practice Gap

Epidermoid cysts are asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, mobile, subcutaneous masses that elevate the skin. Also known as epidermal, keratin, or infundibular cysts, epidermoid cysts are caused by proliferation of surface epidermoid cells within the dermis and can arise anywhere on the body, most commonly on the face, neck, and trunk.1 Cutaneous cysts often contain fluid or semifluid contents and can be aesthetically displeasing or cause mild pain, prompting patients to seek removal. Definitive treatment of epidermoid cysts is complete surgical removal,2 which can be performed in office in a sterile or clean manner by either dermatologists or primary care providers.

Prior to incision, a local anesthetic—commonly lidocaine with epinephrine—is injected in the region surrounding the cyst sac so as not to rupture the cyst wall. Maintaining the cyst wall throughout the procedure ensures total cyst removal and minimizes the risk for recurrence. However, it often is difficult to approximate the cyst border because it cannot be visualized prior to incision.

Throughout the duration of the procedure, cyst contents may suddenly spray out of the area and pose a risk to providers and their staff (Figure, A). Even with careful application around the periphery, either puncture or pericystic anesthesia between the cyst wall and the dermis can lead to splatter. Larger and wider peripheral anesthesia may not be possible given a shortage of lidocaine and a desire to minimize injection. Even with meticulous use of personal protective equipment in cutaneous surgery, infectious organisms found in ruptured cysts and abscesses may spray the surgical field.3 Therefore, it is in our best interest to minimize the trajectory of cyst spray contents.

The Tools

We have employed 2 simple techniques using equipment normally found on a standard surgical tray for easy safe injection of cysts. Supplies needed include 4×4-inch gauze pads, alcohol and chlorhexidine, a marker, all instruments necessary for cyst excision, and a small clear biohazard bag.

The Technique

Prior to covering the cyst, care is taken to locate the cyst opening. At times, a comedo or punctum can be seen overlying the cyst bulge. We mark the lumen and cyst opening with a surgical marker. If the pore is not easily identified, we draw an 8-mm circle around the mound of the cyst.

One option is to apply a gauze pad over the cyst to allow for stabilization of the surgical field and blanket the area from splatter (Figure, B). Then we cover the cyst using antiseptic-soaked gauze as a protective barrier to avoid potentially contaminated spray. This tool can be constructed from a 4×4-inch gauze pad with the addition of alcohol and chlorhexidine. When the cyst is covered, the surgeon can inject the lesion and surrounding tissue without biohazard splatter.

Another method is to cover the cyst with a small clear biohazard bag (Figure, C). When injecting anesthetic through the bag, the spray is captured by the bag and does not reach the surgeon or staff. This method is potentially more effective given that the cyst can still be visualized fully for more accurate injection.

Practice Implications

Outpatient surgical excision is a common effective procedure for epidermoid cysts. However, it is not uncommon for cyst contents to spray during the injection of anesthetic, posing a nuisance to the surgeon, health care staff, and patient. The technique of covering the lesion with antiseptic-soaked gauze or a small clear biohazard bag prevents cyst contents from spraying and reduces risk for contamination. In addition to these protective benefits, the use of readily available items replaces the need to order a splatter control shield.

Limitations—Although we seldom see spray using our technique, covering the cyst with gauze may disguise the region of interest and interfere with accurate incision. Marking the lesion prior to anesthesia administration or using a clear biohazard bag minimizes difficulty visualizing the cyst opening.

Practice Gap

Epidermoid cysts are asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, mobile, subcutaneous masses that elevate the skin. Also known as epidermal, keratin, or infundibular cysts, epidermoid cysts are caused by proliferation of surface epidermoid cells within the dermis and can arise anywhere on the body, most commonly on the face, neck, and trunk.1 Cutaneous cysts often contain fluid or semifluid contents and can be aesthetically displeasing or cause mild pain, prompting patients to seek removal. Definitive treatment of epidermoid cysts is complete surgical removal,2 which can be performed in office in a sterile or clean manner by either dermatologists or primary care providers.

Prior to incision, a local anesthetic—commonly lidocaine with epinephrine—is injected in the region surrounding the cyst sac so as not to rupture the cyst wall. Maintaining the cyst wall throughout the procedure ensures total cyst removal and minimizes the risk for recurrence. However, it often is difficult to approximate the cyst border because it cannot be visualized prior to incision.

Throughout the duration of the procedure, cyst contents may suddenly spray out of the area and pose a risk to providers and their staff (Figure, A). Even with careful application around the periphery, either puncture or pericystic anesthesia between the cyst wall and the dermis can lead to splatter. Larger and wider peripheral anesthesia may not be possible given a shortage of lidocaine and a desire to minimize injection. Even with meticulous use of personal protective equipment in cutaneous surgery, infectious organisms found in ruptured cysts and abscesses may spray the surgical field.3 Therefore, it is in our best interest to minimize the trajectory of cyst spray contents.

The Tools

We have employed 2 simple techniques using equipment normally found on a standard surgical tray for easy safe injection of cysts. Supplies needed include 4×4-inch gauze pads, alcohol and chlorhexidine, a marker, all instruments necessary for cyst excision, and a small clear biohazard bag.

The Technique

Prior to covering the cyst, care is taken to locate the cyst opening. At times, a comedo or punctum can be seen overlying the cyst bulge. We mark the lumen and cyst opening with a surgical marker. If the pore is not easily identified, we draw an 8-mm circle around the mound of the cyst.

One option is to apply a gauze pad over the cyst to allow for stabilization of the surgical field and blanket the area from splatter (Figure, B). Then we cover the cyst using antiseptic-soaked gauze as a protective barrier to avoid potentially contaminated spray. This tool can be constructed from a 4×4-inch gauze pad with the addition of alcohol and chlorhexidine. When the cyst is covered, the surgeon can inject the lesion and surrounding tissue without biohazard splatter.

Another method is to cover the cyst with a small clear biohazard bag (Figure, C). When injecting anesthetic through the bag, the spray is captured by the bag and does not reach the surgeon or staff. This method is potentially more effective given that the cyst can still be visualized fully for more accurate injection.

Practice Implications

Outpatient surgical excision is a common effective procedure for epidermoid cysts. However, it is not uncommon for cyst contents to spray during the injection of anesthetic, posing a nuisance to the surgeon, health care staff, and patient. The technique of covering the lesion with antiseptic-soaked gauze or a small clear biohazard bag prevents cyst contents from spraying and reduces risk for contamination. In addition to these protective benefits, the use of readily available items replaces the need to order a splatter control shield.

Limitations—Although we seldom see spray using our technique, covering the cyst with gauze may disguise the region of interest and interfere with accurate incision. Marking the lesion prior to anesthesia administration or using a clear biohazard bag minimizes difficulty visualizing the cyst opening.

- Zito PM, Scharf R. Epidermoid cyst. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed June 13, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499974

- Weir CB, St. Hilaire NJ. Epidermal inclusion cyst. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed June3, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532310/

- Kuniyuki S, Yoshida Y, Maekawa N, et al. Bacteriological study of epidermal cysts. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;88:23-25. doi:10.2340/00015555-0348

- Zito PM, Scharf R. Epidermoid cyst. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed June 13, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499974

- Weir CB, St. Hilaire NJ. Epidermal inclusion cyst. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed June3, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532310/

- Kuniyuki S, Yoshida Y, Maekawa N, et al. Bacteriological study of epidermal cysts. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;88:23-25. doi:10.2340/00015555-0348

Need a Wood Lamp Alternative? Grab Your Smartphone

Practice Gap

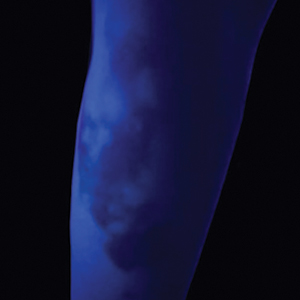

The Wood lamp commonly is used as a diagnostic tool for pigmentary skin conditions (eg, vitiligo) or skin conditions that exhibit fluorescence (eg, erythrasma).1 Recently, its diagnostic efficacy has extended to scabies, in which it unveils a distinctive wavy, bluish-white, linear fluorescence upon illumination.2