User login

How to Optimize Epidermal Approximation During Wound Suturing Using a Smartphone Camera

Practice Gap

Precise wound approximation during cutaneous suturing is of vital importance for optimal closure and long-term scar outcomes. Although buried dermal sutures achieve wound-edge approximation and eversion, meticulous placement of epidermal sutures allows for fine-tuning of the wound edges through epidermal approximation, eversion, and the correction of minor height discrepancies (step-offs).

Several percutaneous suture techniques and materials are available to dermatologic surgeons. However, precise, gap- and tension-free approximation of the wound edges is desired for prompt re-epithelialization and a barely visible scar.1,2

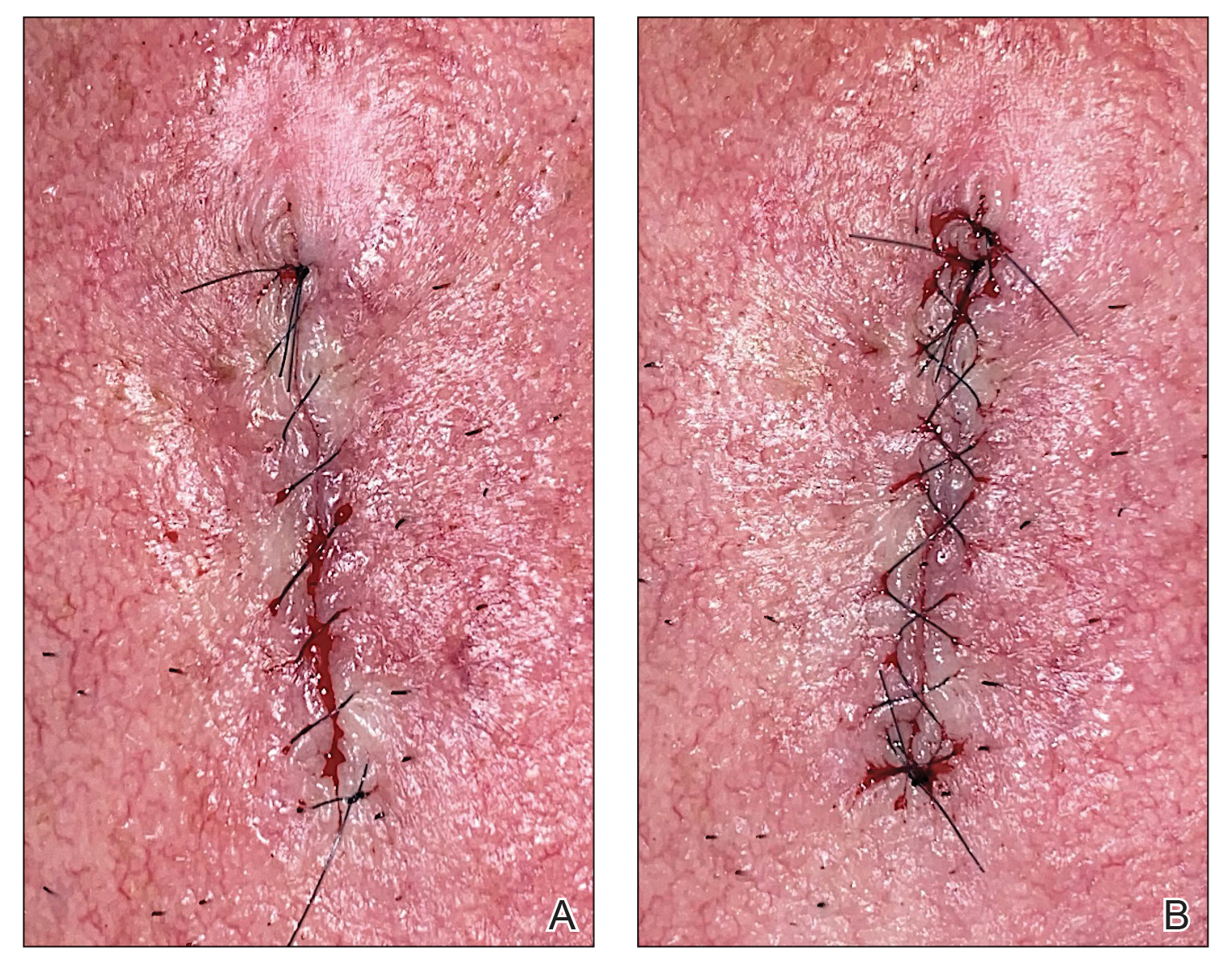

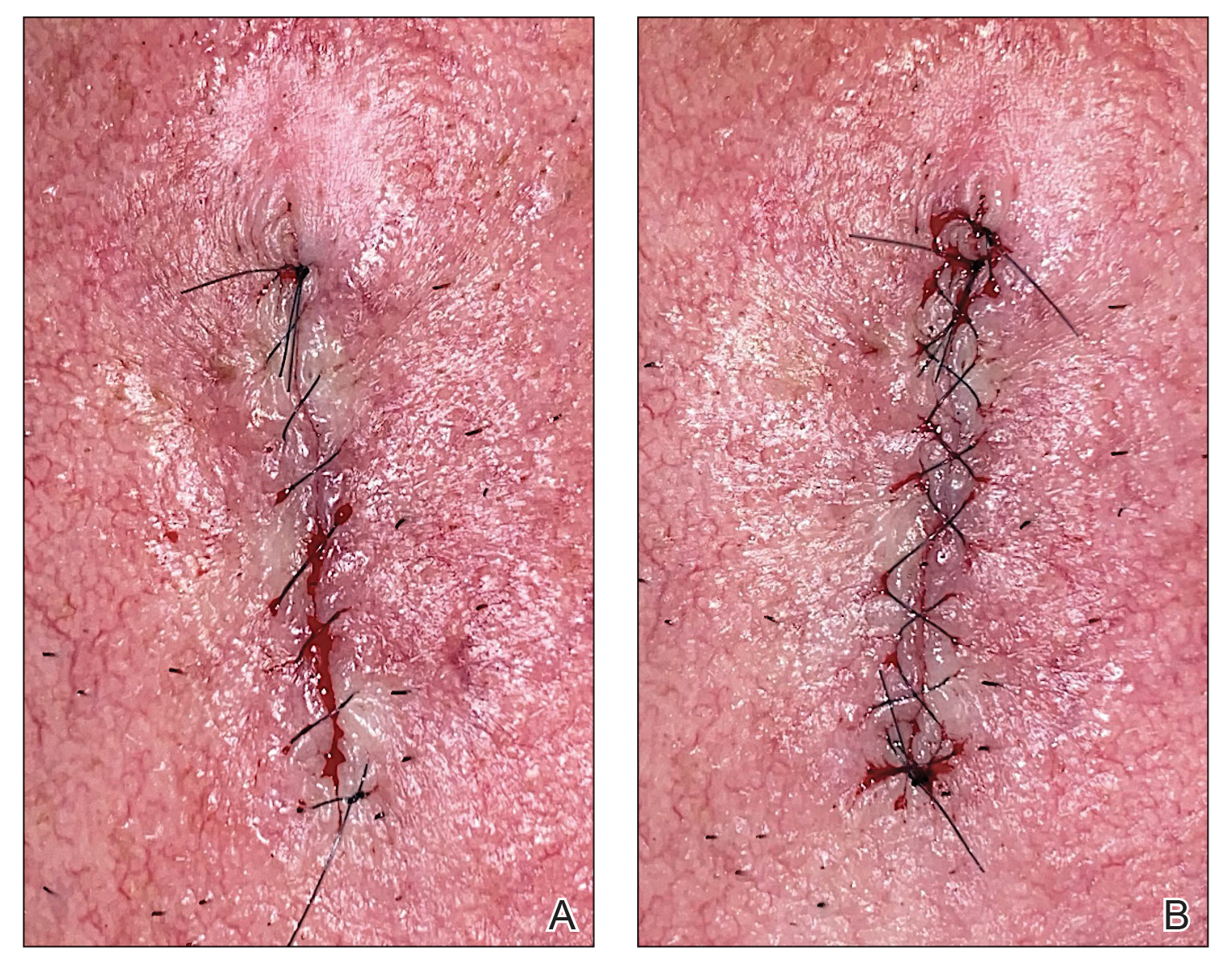

Epidermal sutures should be placed under minimal tension to align the papillary dermis and epidermis precisely. The dermatologic surgeon can evaluate the effectiveness of their suturing technique by carefully examining the closure for visibility of the bilateral wound edges, which should show equally if approximation is precise; small gaps between the wound edges (undesired); or dermal bleeding, which is a manifestation of inaccurate approximation.

Advances in smartphone camera technology have led to high-quality photography in a variety of settings. Although smartphone photography often is used for documentation purposes in health care, we recommend incorporating it as a quality-control checkpoint for objective evaluation, allowing the dermatologic surgeon to scrutinize the wound edges and refine their surgical technique to improve scar outcomes.

The Technique

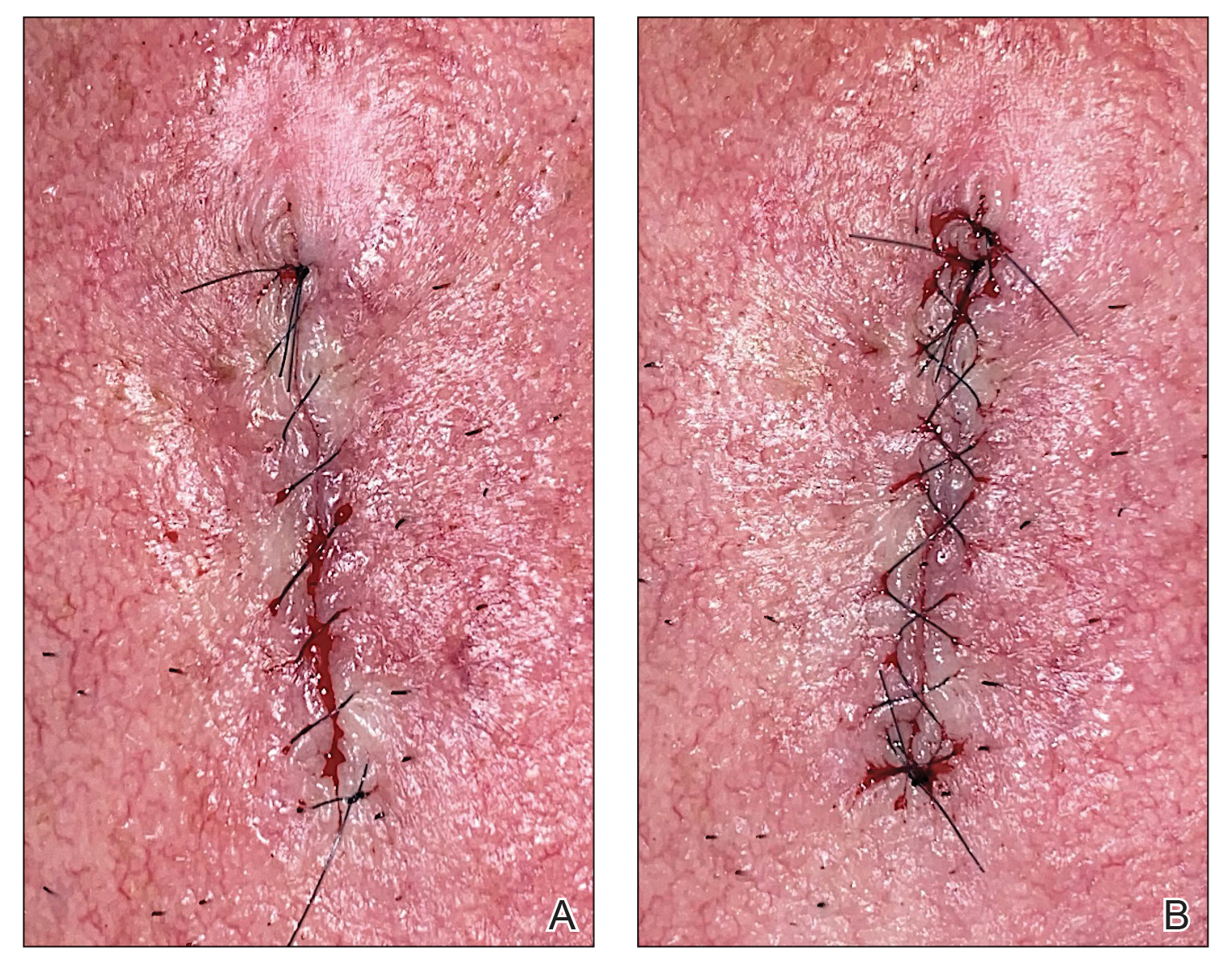

After suturing the wound closed, we routinely use a 12-megapixel smartphone camera (up to 2× optical zoom) to photograph the closed wound at 1× or 2× magnification to capture more details and use the zoom function to further evaluate the wound edges close-up (Figure). In any area where inadequate epidermal approximation is noted on the photograph, an additional stitch can be placed. Photography can be repeated until ideal reapproximation occurs.

Practice Implications

Most smartphones released in recent years have a 12-megapixel camera, making them more easily accessible than surgical loupes. Additionally, surgical loupes are expensive, come with a learning curve, and can be intimidating to new or inexperienced surgeons or dermatology residents. Because virtually every dermatologic surgeon has access to a smartphone and snapping an image takes no more than a few seconds, we believe this technique is a valuable new self-assessment tool for dermatologic surgeons. It may be particularly valuable to dermatology residents and new/inexperienced surgeons looking to improve their techniques and scar outcomes.

- Perry AW, McShane RH. Fine-tuning of the skin edges in the closure of surgical wounds. Controlling inversion and eversion with the path of the needle—the right stitch at the right time. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1981;7:471-476. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1981.tb00680.x

- Miller CJ, Antunes MB, Sobanko JF. Surgical technique for optimal outcomes: part II. repairing tissue: suturing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:389-402. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.006

Practice Gap

Precise wound approximation during cutaneous suturing is of vital importance for optimal closure and long-term scar outcomes. Although buried dermal sutures achieve wound-edge approximation and eversion, meticulous placement of epidermal sutures allows for fine-tuning of the wound edges through epidermal approximation, eversion, and the correction of minor height discrepancies (step-offs).

Several percutaneous suture techniques and materials are available to dermatologic surgeons. However, precise, gap- and tension-free approximation of the wound edges is desired for prompt re-epithelialization and a barely visible scar.1,2

Epidermal sutures should be placed under minimal tension to align the papillary dermis and epidermis precisely. The dermatologic surgeon can evaluate the effectiveness of their suturing technique by carefully examining the closure for visibility of the bilateral wound edges, which should show equally if approximation is precise; small gaps between the wound edges (undesired); or dermal bleeding, which is a manifestation of inaccurate approximation.

Advances in smartphone camera technology have led to high-quality photography in a variety of settings. Although smartphone photography often is used for documentation purposes in health care, we recommend incorporating it as a quality-control checkpoint for objective evaluation, allowing the dermatologic surgeon to scrutinize the wound edges and refine their surgical technique to improve scar outcomes.

The Technique

After suturing the wound closed, we routinely use a 12-megapixel smartphone camera (up to 2× optical zoom) to photograph the closed wound at 1× or 2× magnification to capture more details and use the zoom function to further evaluate the wound edges close-up (Figure). In any area where inadequate epidermal approximation is noted on the photograph, an additional stitch can be placed. Photography can be repeated until ideal reapproximation occurs.

Practice Implications

Most smartphones released in recent years have a 12-megapixel camera, making them more easily accessible than surgical loupes. Additionally, surgical loupes are expensive, come with a learning curve, and can be intimidating to new or inexperienced surgeons or dermatology residents. Because virtually every dermatologic surgeon has access to a smartphone and snapping an image takes no more than a few seconds, we believe this technique is a valuable new self-assessment tool for dermatologic surgeons. It may be particularly valuable to dermatology residents and new/inexperienced surgeons looking to improve their techniques and scar outcomes.

Practice Gap

Precise wound approximation during cutaneous suturing is of vital importance for optimal closure and long-term scar outcomes. Although buried dermal sutures achieve wound-edge approximation and eversion, meticulous placement of epidermal sutures allows for fine-tuning of the wound edges through epidermal approximation, eversion, and the correction of minor height discrepancies (step-offs).

Several percutaneous suture techniques and materials are available to dermatologic surgeons. However, precise, gap- and tension-free approximation of the wound edges is desired for prompt re-epithelialization and a barely visible scar.1,2

Epidermal sutures should be placed under minimal tension to align the papillary dermis and epidermis precisely. The dermatologic surgeon can evaluate the effectiveness of their suturing technique by carefully examining the closure for visibility of the bilateral wound edges, which should show equally if approximation is precise; small gaps between the wound edges (undesired); or dermal bleeding, which is a manifestation of inaccurate approximation.

Advances in smartphone camera technology have led to high-quality photography in a variety of settings. Although smartphone photography often is used for documentation purposes in health care, we recommend incorporating it as a quality-control checkpoint for objective evaluation, allowing the dermatologic surgeon to scrutinize the wound edges and refine their surgical technique to improve scar outcomes.

The Technique

After suturing the wound closed, we routinely use a 12-megapixel smartphone camera (up to 2× optical zoom) to photograph the closed wound at 1× or 2× magnification to capture more details and use the zoom function to further evaluate the wound edges close-up (Figure). In any area where inadequate epidermal approximation is noted on the photograph, an additional stitch can be placed. Photography can be repeated until ideal reapproximation occurs.

Practice Implications

Most smartphones released in recent years have a 12-megapixel camera, making them more easily accessible than surgical loupes. Additionally, surgical loupes are expensive, come with a learning curve, and can be intimidating to new or inexperienced surgeons or dermatology residents. Because virtually every dermatologic surgeon has access to a smartphone and snapping an image takes no more than a few seconds, we believe this technique is a valuable new self-assessment tool for dermatologic surgeons. It may be particularly valuable to dermatology residents and new/inexperienced surgeons looking to improve their techniques and scar outcomes.

- Perry AW, McShane RH. Fine-tuning of the skin edges in the closure of surgical wounds. Controlling inversion and eversion with the path of the needle—the right stitch at the right time. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1981;7:471-476. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1981.tb00680.x

- Miller CJ, Antunes MB, Sobanko JF. Surgical technique for optimal outcomes: part II. repairing tissue: suturing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:389-402. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.006

- Perry AW, McShane RH. Fine-tuning of the skin edges in the closure of surgical wounds. Controlling inversion and eversion with the path of the needle—the right stitch at the right time. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1981;7:471-476. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1981.tb00680.x

- Miller CJ, Antunes MB, Sobanko JF. Surgical technique for optimal outcomes: part II. repairing tissue: suturing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:389-402. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.006

The Role of Toluidine Blue in Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Systematic Review

Toluidine blue (TB), a dye with metachromatic staining properties, was developed in 1856 by William Henry Perkin.1 Metachromasia is a perceptible change in the color of staining of living tissue due to the electrochemical properties of the tissue. Tissues that contain high concentrations of ionized sulfate and phosphate groups (high concentrations of free electronegative groups) form polymeric aggregates of the basic dye solution that alter the absorbed wavelengths of light.2 The function of this characteristic is to use a single dye to highlight different structures in tissue based on their relative chemical differences.3

Toluidine blue primarily was used within the dye industry until the 1960s, when it was first used in vital staining of the oral mucosa.2 Because of the tissue absorption potential, this technique was used to detect the location of oral malignancies.4 Since then, TB has progressively been used for staining fresh frozen sections in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). In a 2003 survey study (N=310), 16.8% of surgeons performing MMS reported using TB in their laboratory.5 We sought to systematically review the published literature describing the uses of TB in the setting of fresh frozen sections and MMS.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search of the PubMed and Cochrane databases for articles published before December 1, 2019, to identify any relevant studies in English. Electronic searches were performed using the terms toluidine blue and Mohs or Mohs micrographic surgery. We manually checked the bibliographies of the identified articles to further identify eligible studies.

Eligibility Criteria—The inclusion criteria were articles that (1) considered TB in the context of MMS, (2) were published in peer-reviewed journals, (3) were published in English, and (4) were available as full text. Systematic reviews were excluded.

Data Extraction and Outcomes—All relevant information regarding the study characteristics, including design, level of evidence, methodologic quality of evidence, pathology examined, and outcome measures, were collected by 2 independent reviewers (T.L. and A.D.) using a predetermined data sheet. The same 2 reviewers were used for all steps of the review process, data were independently obtained, and any discrepancy was introduced for a third opinion (D.H.) and agreed upon by the majority.

Quality Assessment—The level of evidence was evaluated based on the criteria of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Two reviewers (T.L. and A.D.) graded each article included in the review.

Results

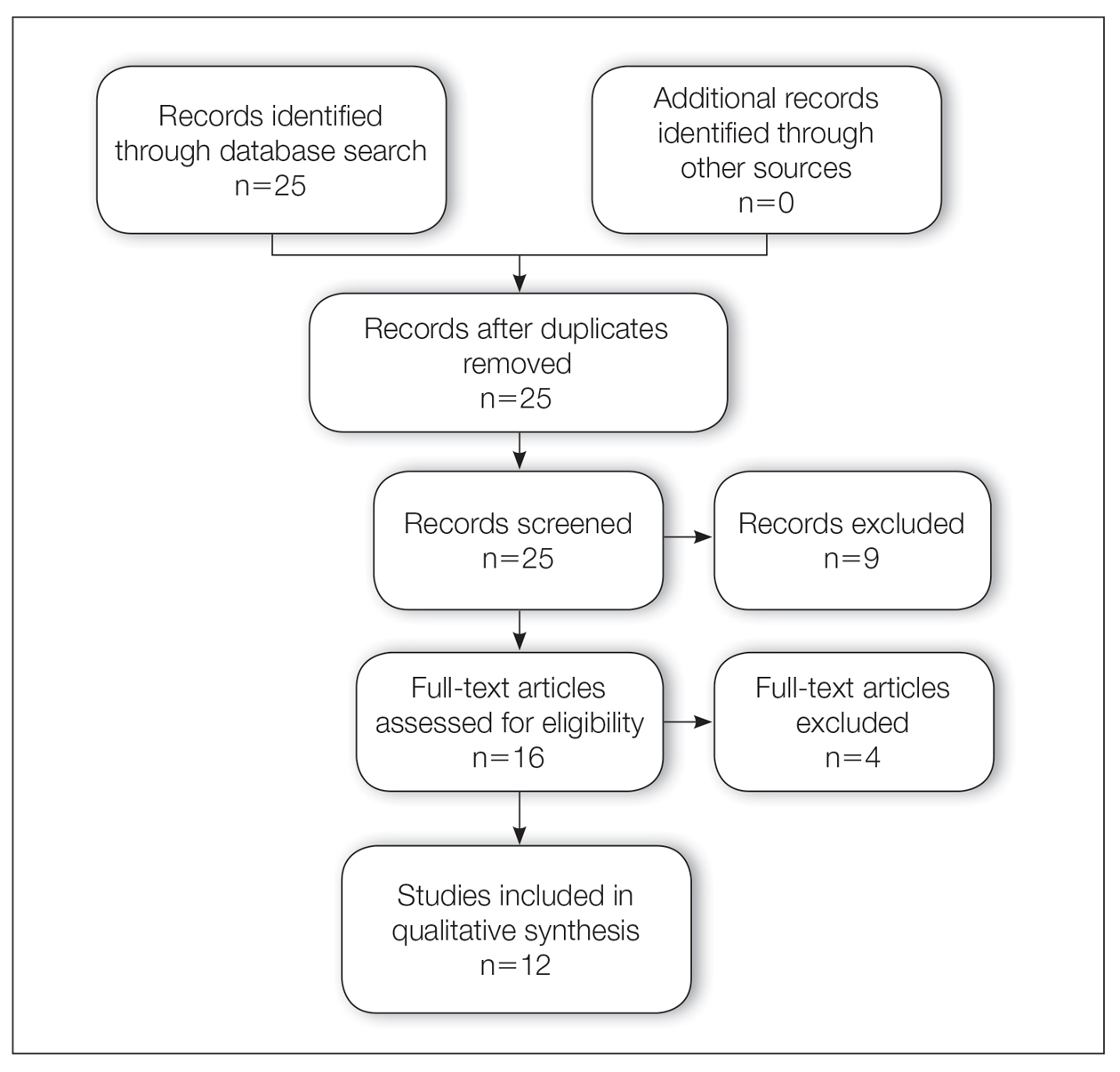

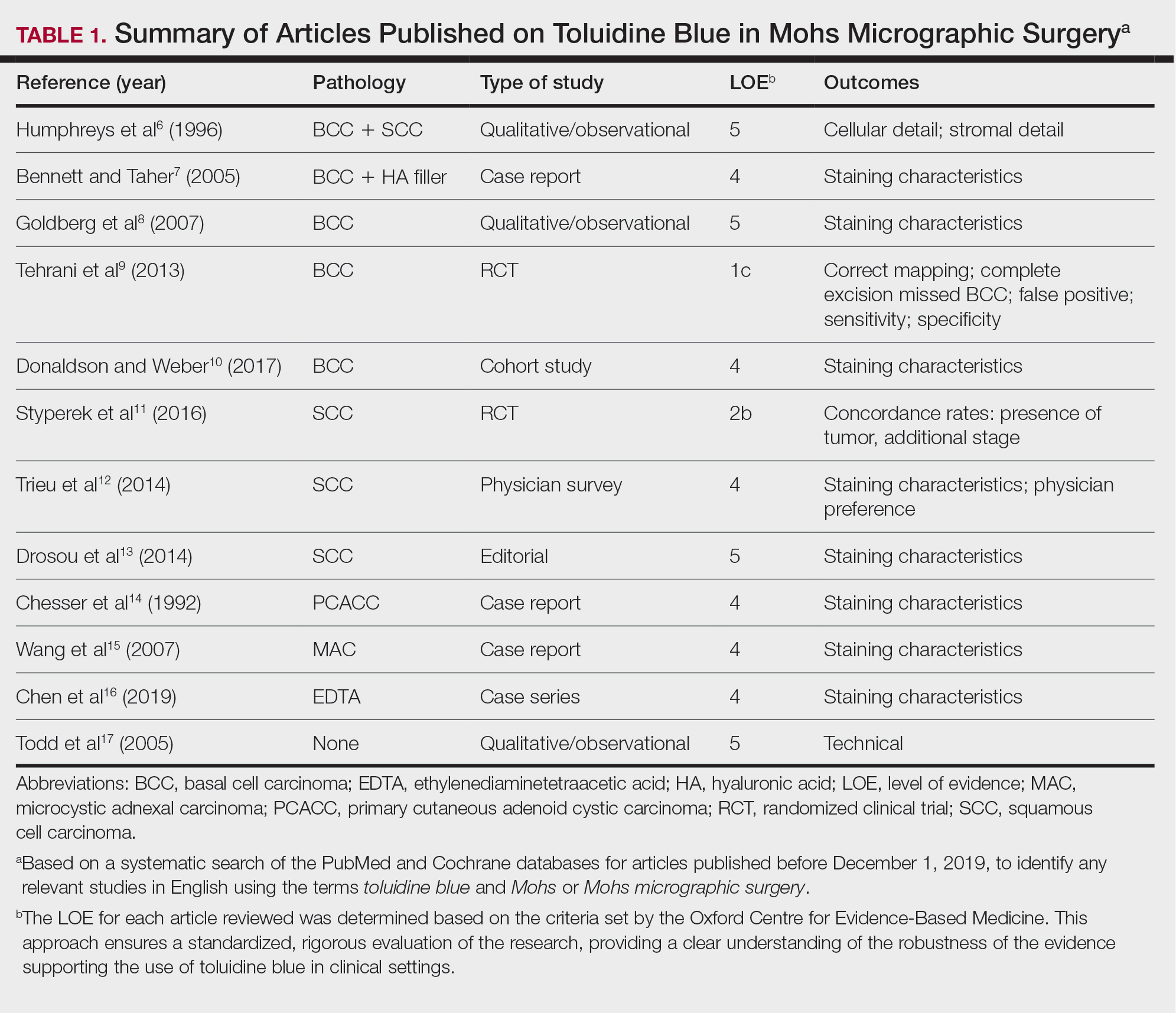

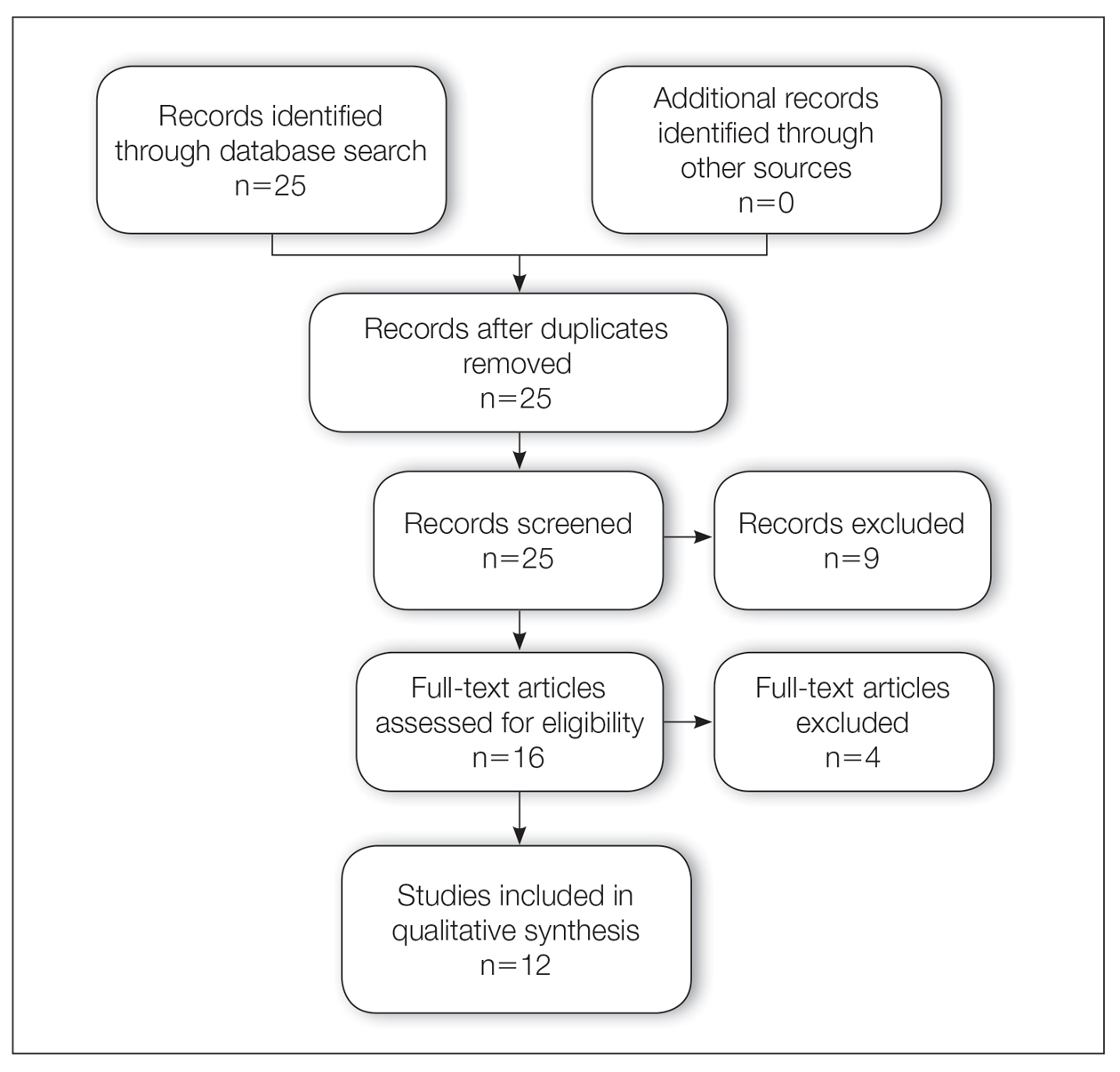

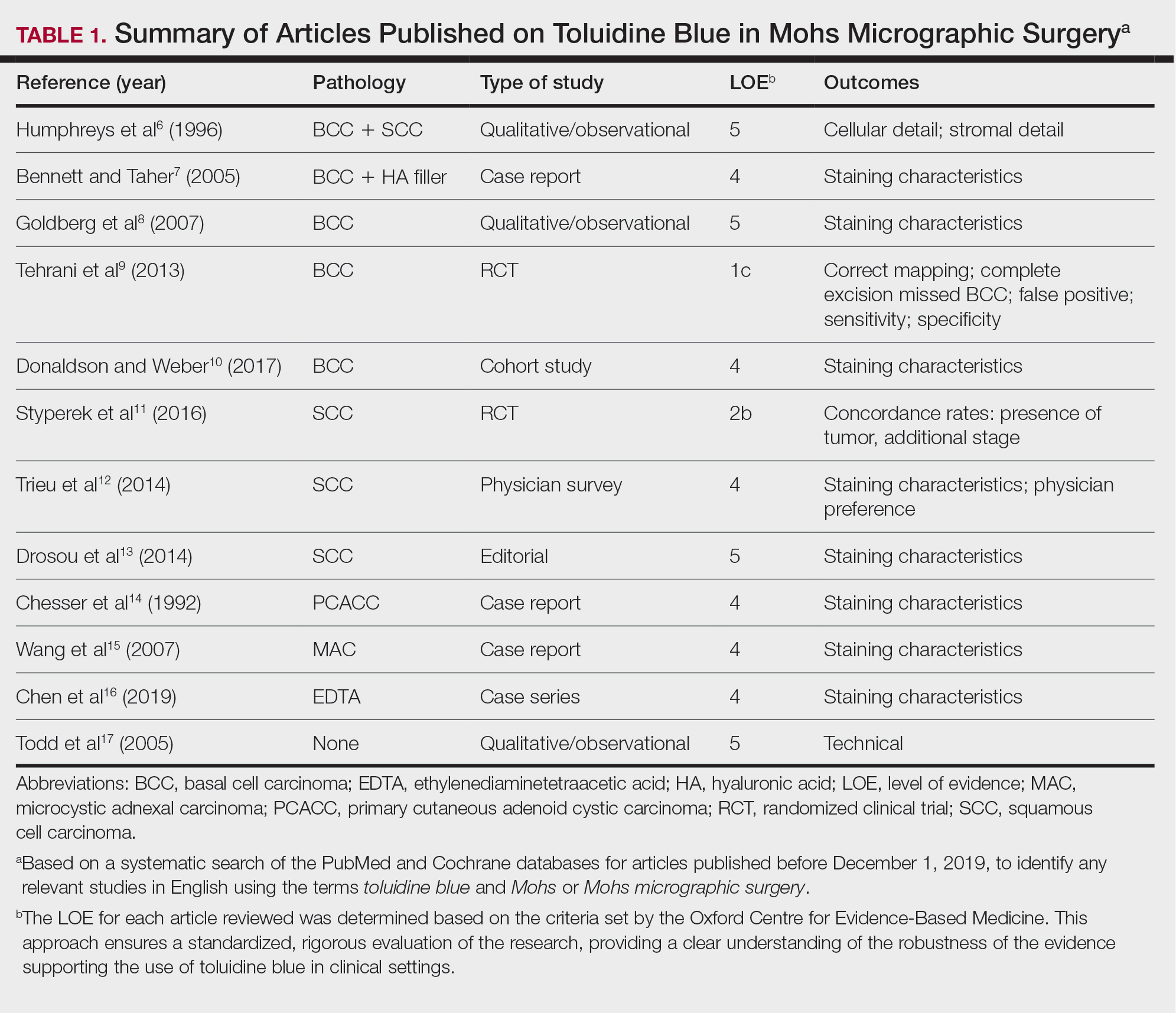

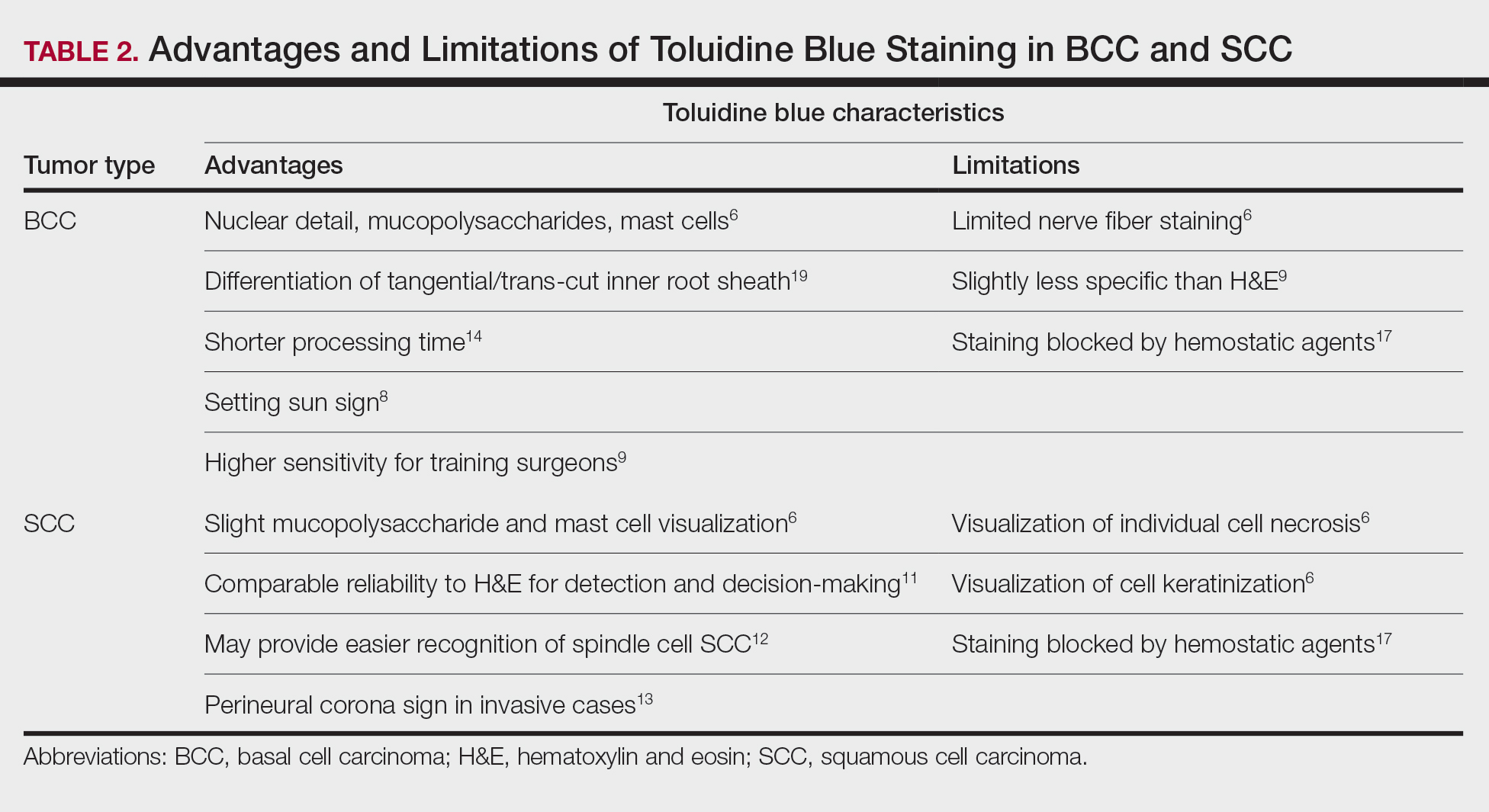

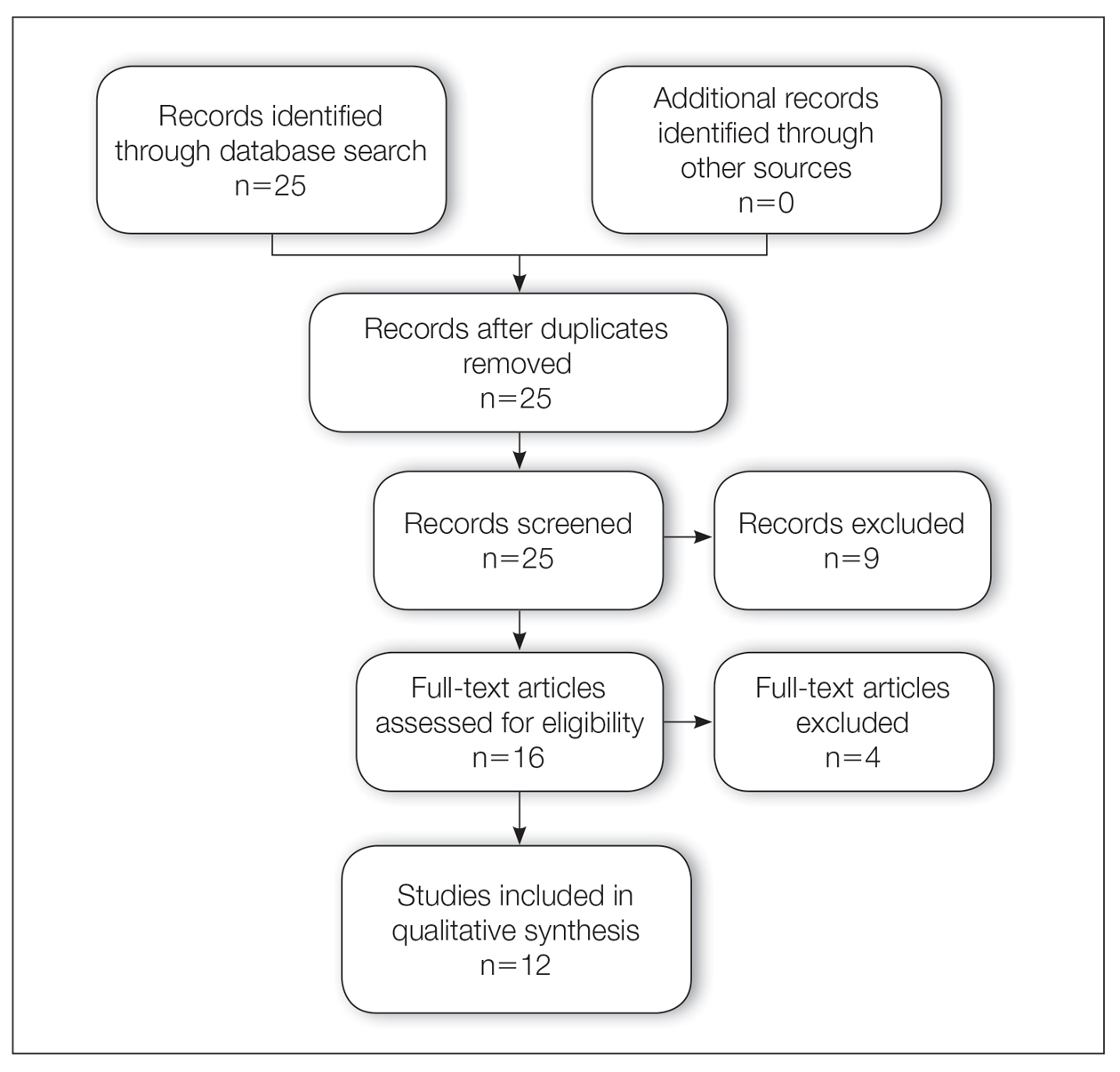

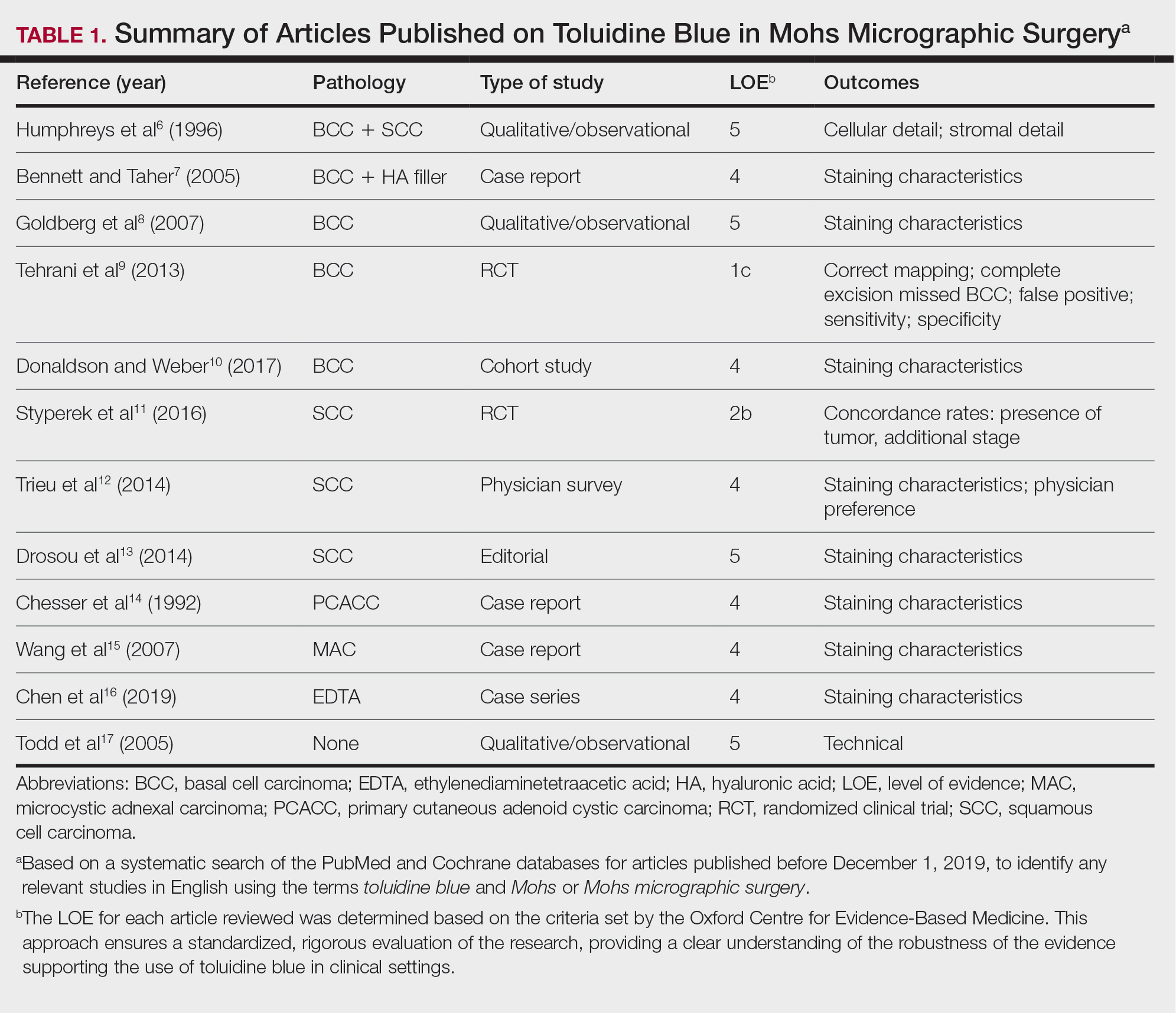

A total of 25 articles were reviewed. After the titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, 12 articles remained (Figure 1). Of these, 1 compared basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), 4 were related to BCC, 3 were related to SCC, 1 was related to microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), 1 was related to primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma (PCACC), and 2 were related to technical aspects of the staining process (Table 1).

A majority of the articles included in this review were qualitative and observational in nature, describing the staining characteristics of TB. Study characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Comment

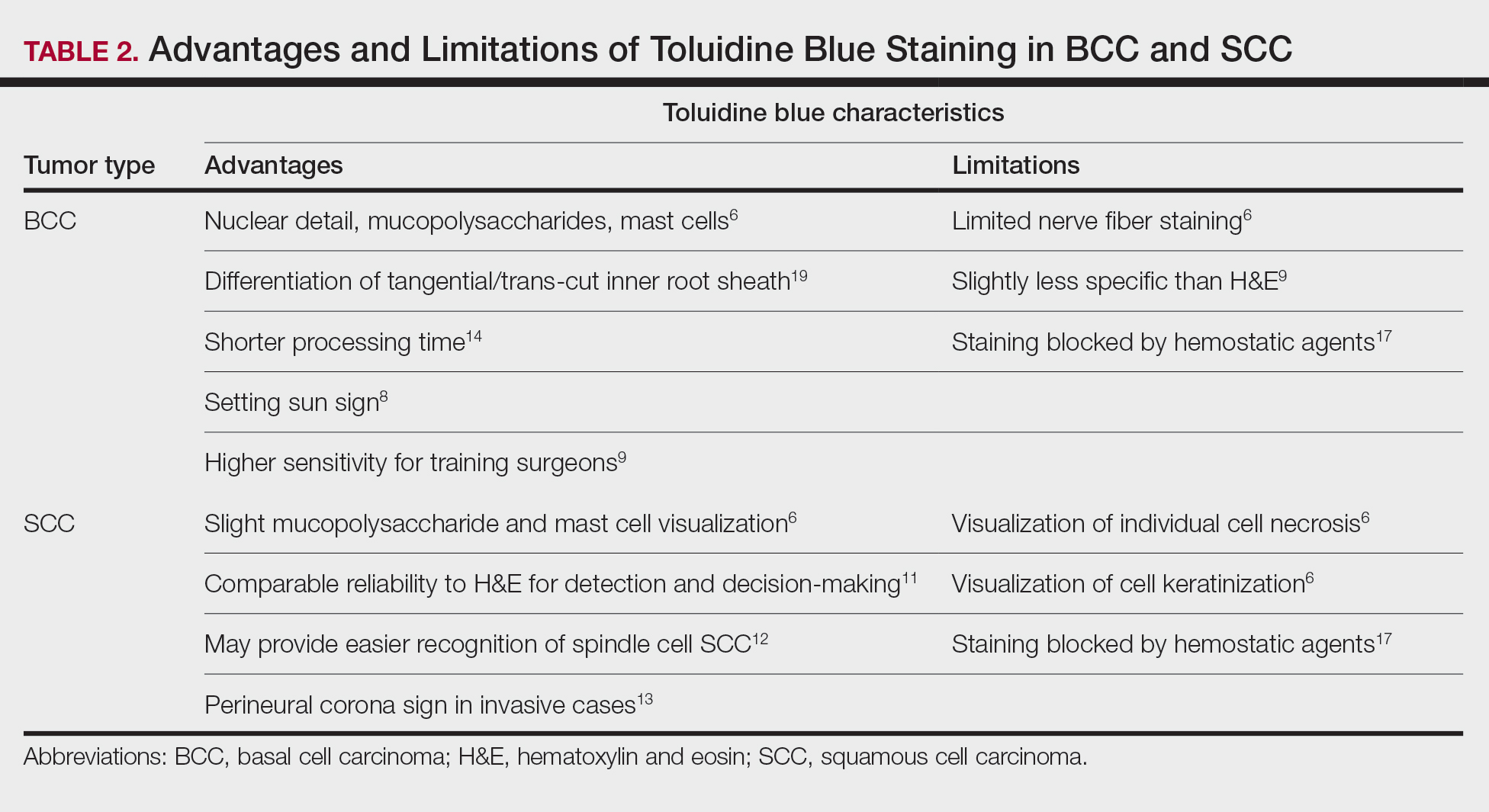

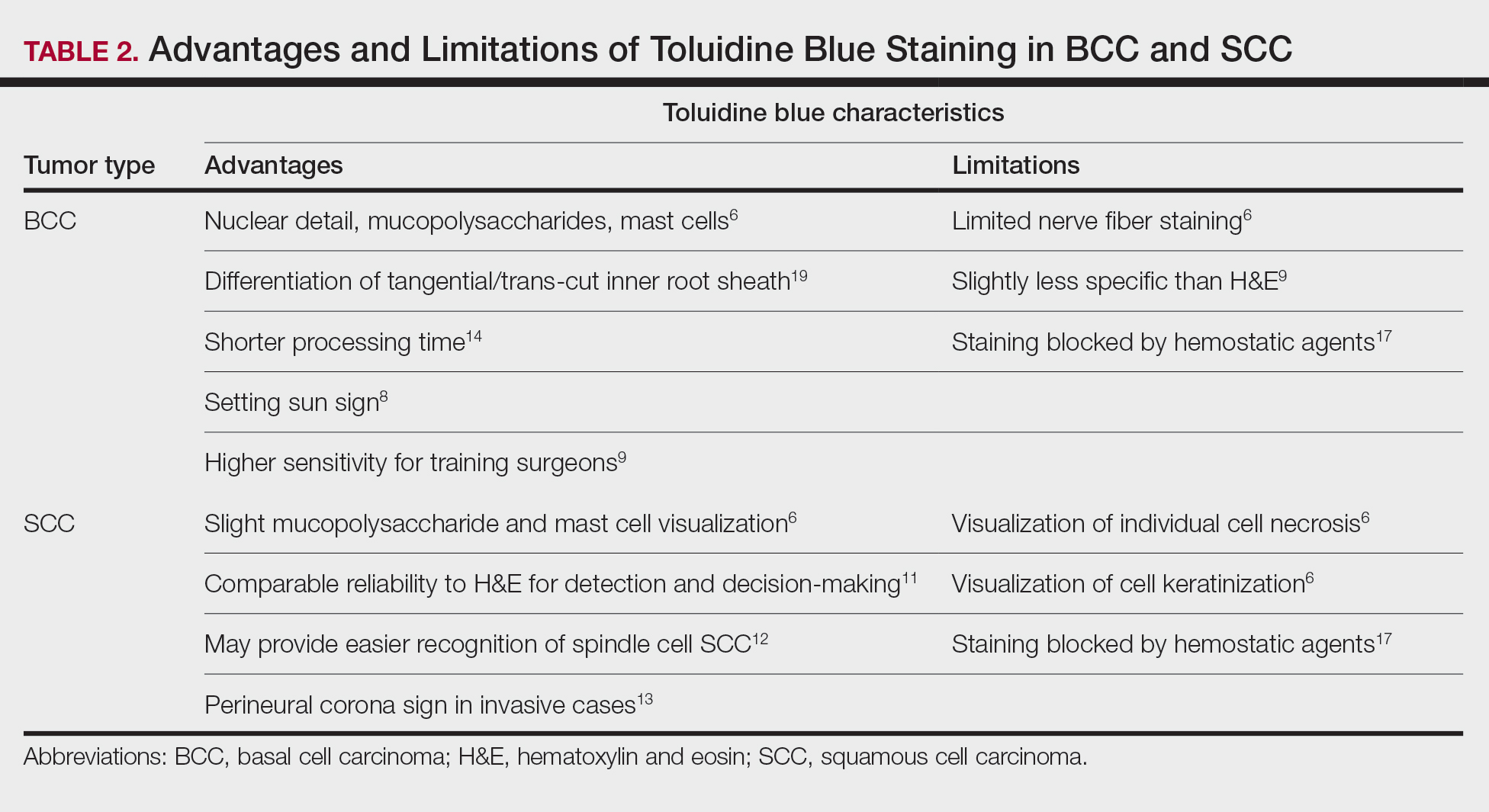

Basal Cell Carcinoma—Toluidine blue staining characteristics help to identify BCC nests by differentiating them from hair follicles in frozen sections. The metachromatic characteristic of TB stains the inner root sheath deep blue and highlights the surrounding stromal mucin of BCC a magenta color.18,19 In hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains, these 2 distinct structures can be differentiated by cleft formation around tumor nests, mitotic figures, and the lack of a fibrous sheath present in BCC tumors.20 The advantages and limitations of TB staining of BCC are presented in Table 2.

Humphreys et al6 suggested a noticeable difference between H&E and TB in the staining of cellular and stromal components. The nuclear detail of tumor cells was subjectively sharper and clearer with TB staining. The staining of stromal components may provide the most assistance in locating BCC islands. Mucopolysaccharide staining may be absent in H&E but stain a deep magenta with TB. Although the presence of mucopolysaccharides does not specifically indicate a tumor, it may prompt further attention and provide an indicator for sparse and infiltrative tumor cells.6 The metachromatic stromal change may indicate a narrow tumor-free margin where additional deeper sections often reveal tumor that may warrant additional resection margin in more aggressive malignancies. In particular, sclerosing/morpheaform BCCs have been shown to induce glycosaminoglycan synthesis and are highlighted more readily with TB than with H&E when compared to surrounding tissue.21 This differentiation in staining has remained a popular reason to routinely incorporate TB into the staining of infiltrative and morpheaform variants of BCC. Additionally, stromal mast cells are believed to be more abundant in the stroma of BCC and are more readily visualized in tissue specimens stained with TB, appearing as bright purple metachromatic granules. These granules are larger than normal and are increased in number.6

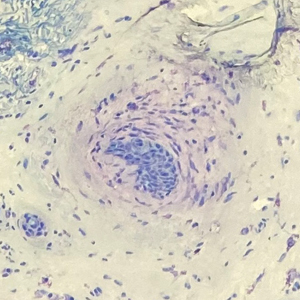

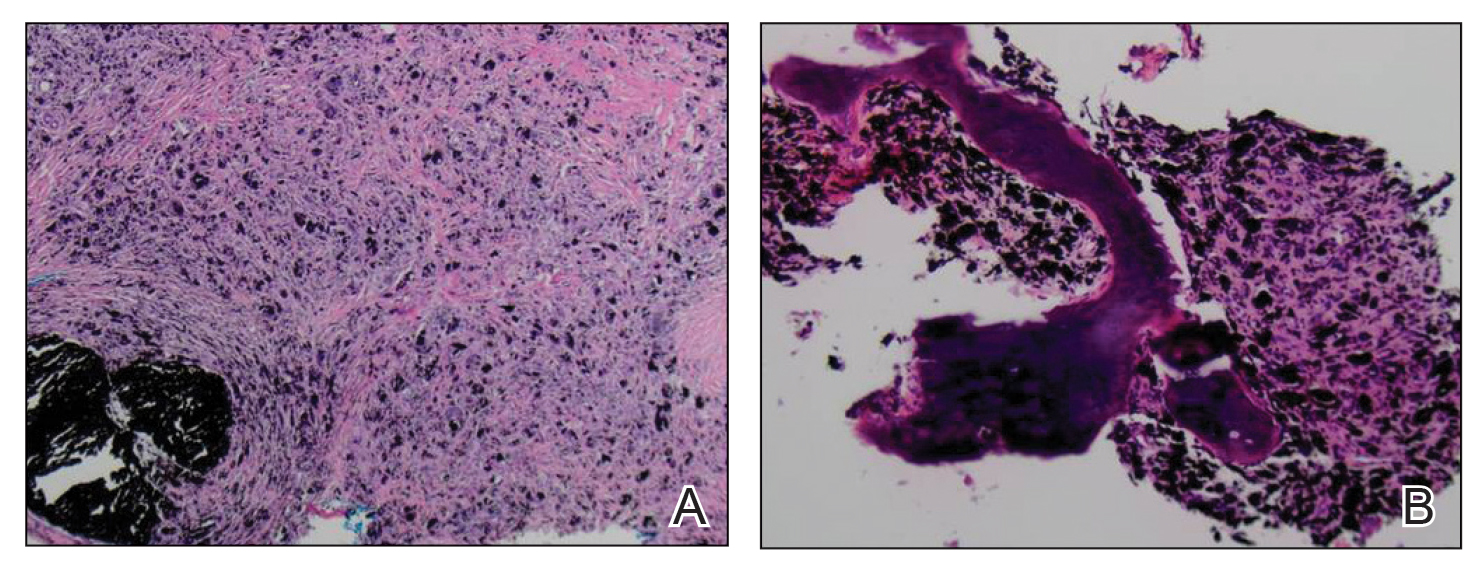

The margin behavior of BCC stained with TB was further characterized by Goldberg et al,8 who coined the term setting sun sign, which may be present in sequential sections of a disappearing nodule of a BCC tumor. Stroma, inflammatory infiltrate, and mast cells produce a magenta glow surrounding BCC tumors that is reminiscent of a setting sun (Figure 2). Invasive BCC is considered variable in this presentation, primarily because of zones of cell-free fluid and edema or the second area of inflammatory cells. This unique sign may benefit the inspecting Mohs surgeon by providing a clue to an underlying process that may have residual BCC tumors. The setting sun sign also may assist in identifying exact surgical margins.8

The nasal surface has a predilection for BCC.22 The skin of the nose has numerous look-alike structures to consider for complete tumor removal and avoidance of unnecessary removal. One challenge is distinguishing follicular basaloid proliferations (FBP) from BCC, a scenario that is more common on the nose.22 When TB staining was used, the sensitivity for detecting FBP reached 100% in 34 cases reviewed by Donaldson and Weber.10 None of the cases examined showed TB metachromasia surrounding FBP, thus indicating that TB can dependably identify this benign entity. Conversely, 5% (N=279) of BCCs confirmed on H&E did not exhibit surrounding TB metachromasia. This finding is concerning regarding the specificity of TB staining for BCC, but the authors of this study suggested the possibility that these exceptions were benign “simulants” (ie, trichoepithelioma) of BCC.10

The use of TB also has been shown to be statistically beneficial in Mohs training. In a single-center, single-fellow experiment, the sensitivity and specificity of using TB for BCC were extrapolated.9 Using TB as an adjunct in deep sections showed superior sensitivity to H&E alone in identifying BCC, increasing sensitivity from 96.3% to 99.7%. In a cohort of 352 BCC excisions and frozen sections, only 1 BCC was not completely excised. If H&E only had been performed, the fellow would have missed 13 residual BCC tumors.9

Bennett and Taher7 described a case in which hyaluronic acid (HA) from a filler injection was confused with the HA surrounding BCC tumor nests. They found that when TB is used as an adjunct, the HA filler is easier to differentiate from the HA surrounding the BCC tumor nests. In frozen sections stained with TB, the HA filler appeared as an amorphous, metachromatic, reddish-purple, whereas the HA surrounding the BCC tumor nests appeared as a well-defined red. These findings were less obvious in the same sections stained with H&E alone.7

Squamous Cell Carcinoma—In early investigations, the utility of TB in identifying SCC in frozen sections was thought to be limited. The description by Humphreys and colleagues6 of staining characteristics in SCC suggested that the nuclear detail that H&E provides is more easily recognized. The deep aqua nuclear staining produced with TB was considered more difficult to observe than the cytoplasmic eosinophilia of pyknotic and keratinizing cells in H&E.6

Toluidine blue may be beneficial in providing unique staining characteristics to further detail tumors that are difficult to interpret, such as spindle cell SCC and perineural invasion of aggressive SCC. In H&E, squamous cells of spindle cell SCC (scSCC) blend into the background of inflammatory cells and can be perceptibly difficult to locate. A small cohort of 3 Mohs surgeons who routinely use H&E were surveyed on their ability to detect a proven scSCC in H&E or TB by photograph.12 All 3 were able to detect the scSCC in the TB photographs, but only 2 of 3 were able to detect it in H&E photographs. All 3 surgeons agreed that TB was preferable to H&E for this tumor type. These findings suggested that TB may be superior and preferred over H&E for visualizing tumor cells of scSCC.12 The TB staining characteristics of perineural invasion of aggressive SCC have been referred to as the perineural corona sign because of the bright magenta stain that forms around affected nerves.13 Drosou et al13 suggested that TB may enhance the diagnostic accuracy for perineural SCC.

Rare Tumors—The adjunctive use of TB with H&E has been examined in rare tumors. Published reports have highlighted its use in MMS for treating MAC and PCACC. Toluidine blue exhibits staining advantages for these tumors. It may render isolated nests and perineural invasion of MAC more easily visible on frozen section.15

Although PCACC is rare, the recurrence rate is high.23 Toluidine blue has been used with MMS to ensure complete removal and higher cure rates. The metachromatic nature of TB is advantageous in staining the HA present in these tumors. Those who have reported the use of TB for PCACC prefer it to H&E for frozen sections.14

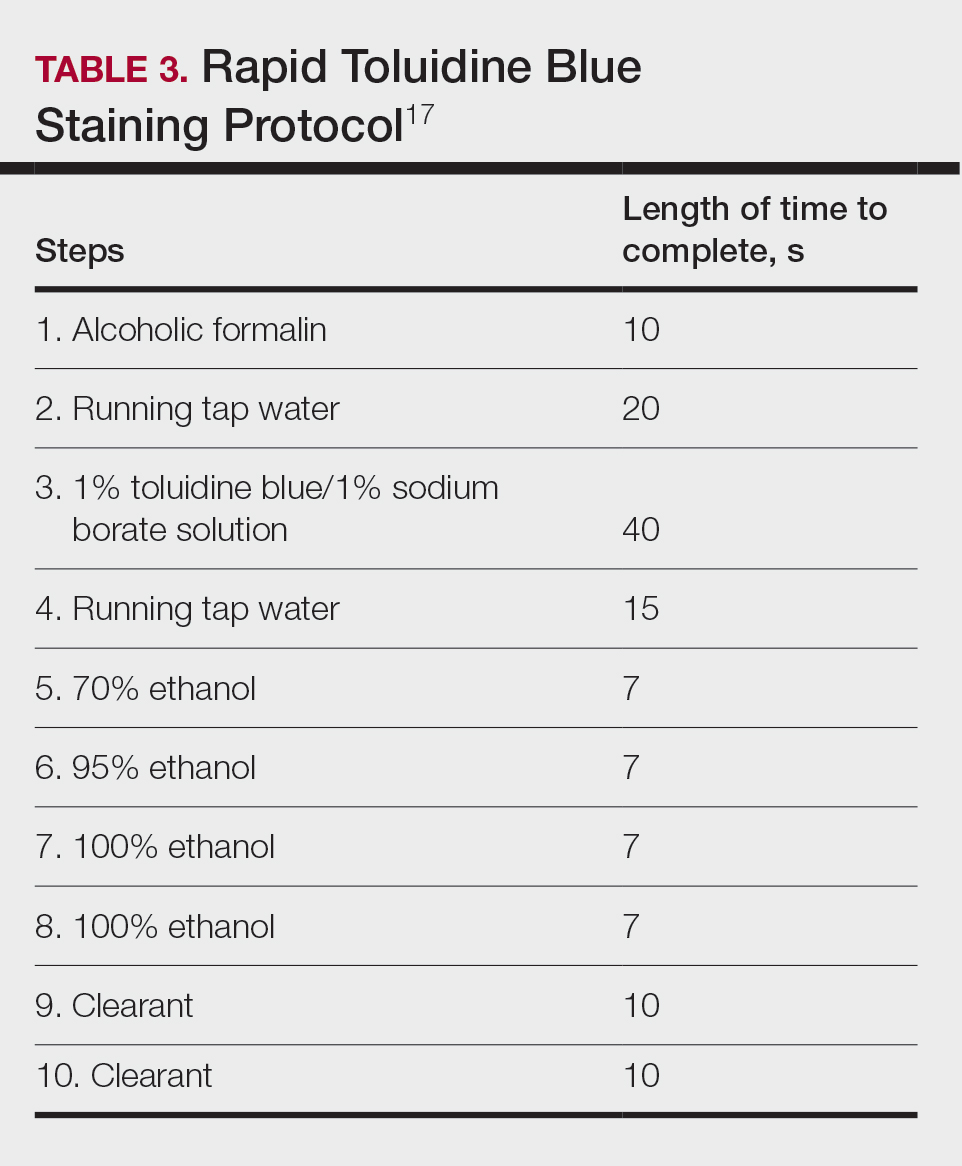

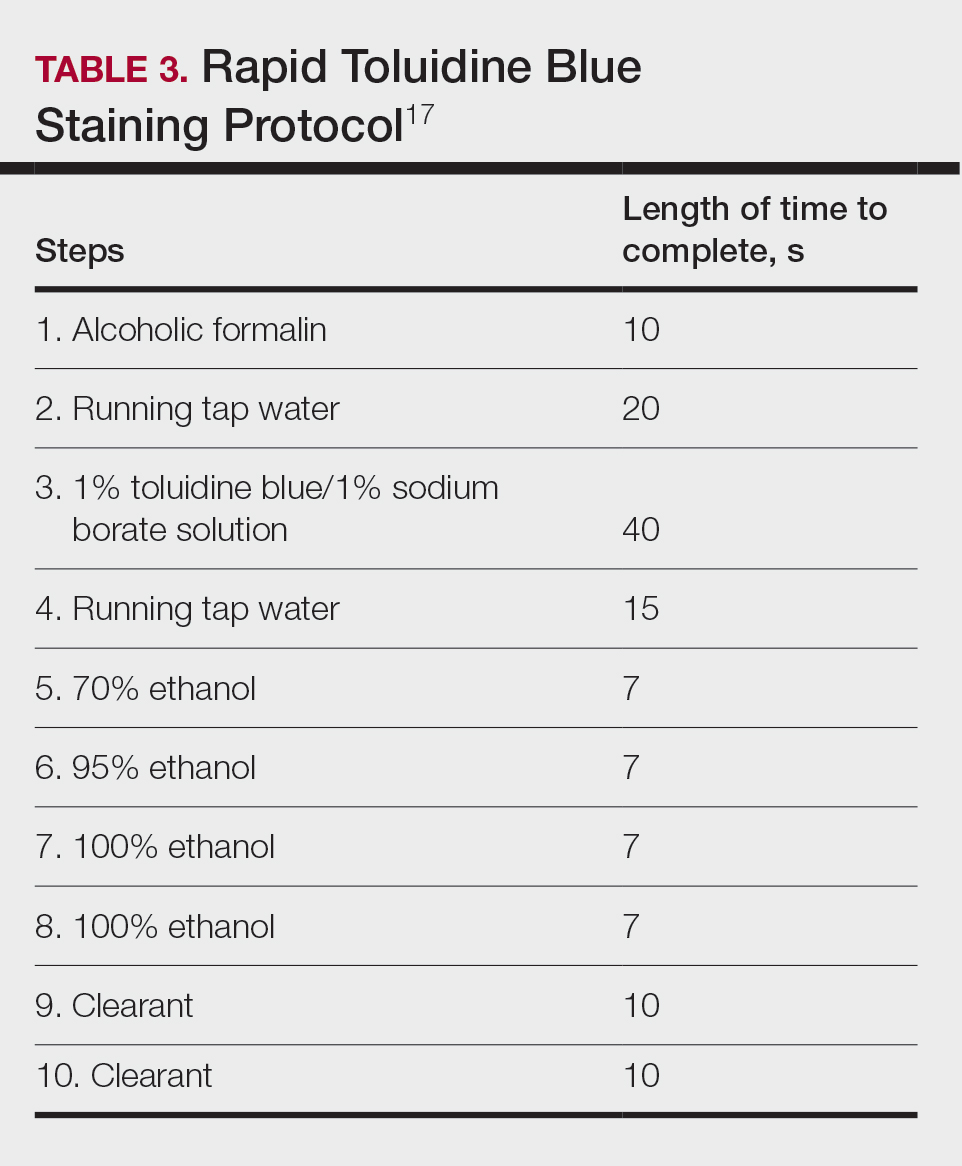

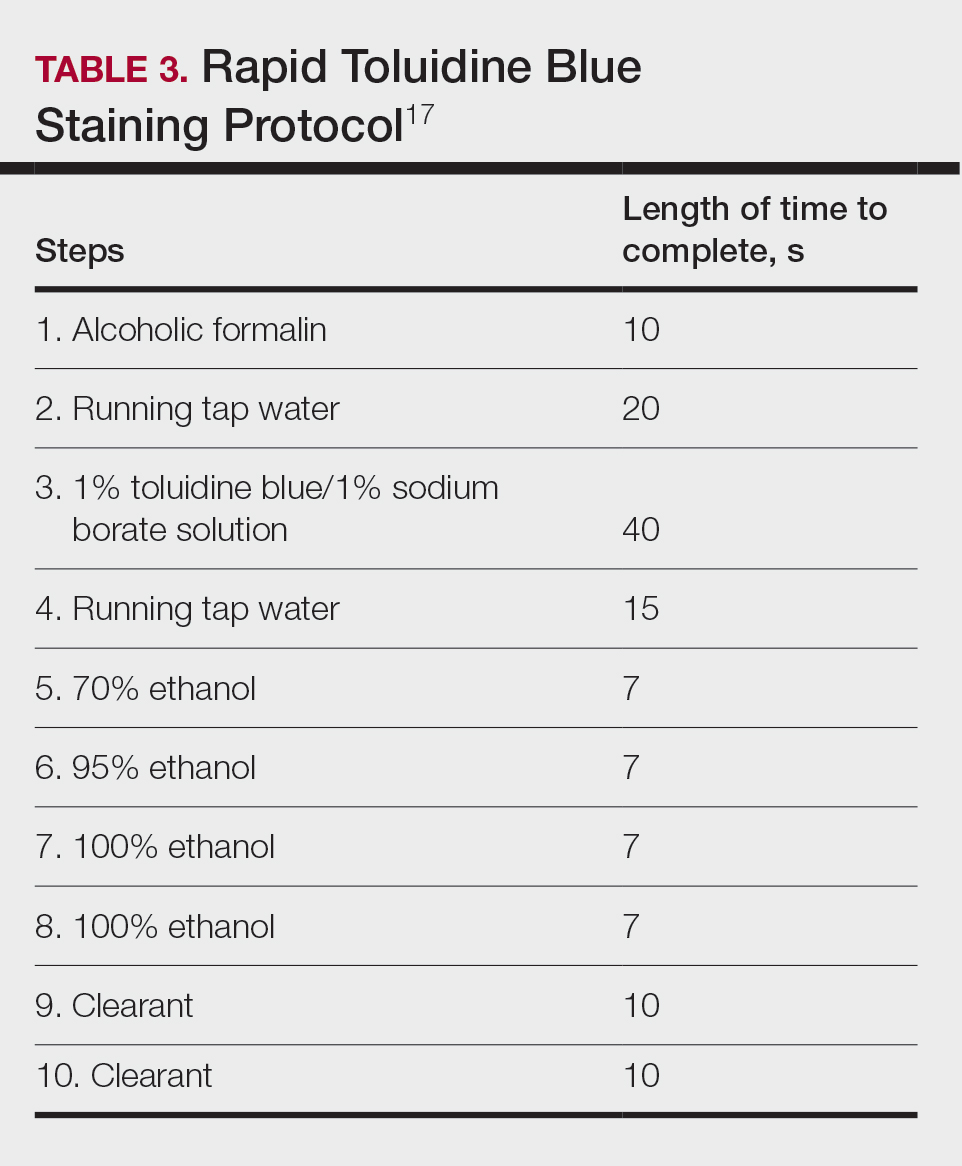

Technical Aspects—The staining time for TB-treated slides is reduced compared to H&E staining; staining can be efficiently done in frozen sections in less than 2.5 minutes using the method shown in Table 3.17 In comparison, typical H&E staining takes 9 minutes, and older TB techniques take 7 minutes.6

Conclusion

Toluidine blue may play an important and helpful role in the successful diagnosis and treatment of particular cutaneous tumors by providing additional diagnostic information. Although surgeons performing MMS will continue using the staining protocols with which they are most comfortable, adjunctive use of TB over time may provide an additional benefit at low risk for disrupting practice efficiency or workflow. Many Mohs surgeons are accustomed to using this stain, even preferring to interpret only TB-stained slides for cutaneous malignancy. Most published studies on this topic have been observational in nature, and additional controlled trials may be warranted to determine the effects on outcomes in real-world practice.

- Culling CF, Allison TR. Cellular Pathology Technique. 4th ed. Butterworths; 1985.

- Bergeron JA, Singer M. Metachromasy: an experimental and theoretical reevaluation. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1958;4:433-457. doi:10.1083/jcb.4.4.433

- Epstein JB, Scully C, Spinelli J. Toluidine blue and Lugol’s iodine application in the assessment of oral malignant disease and lesions at risk of malignancy. J Oral Pathol Med. 1992;21:160-163. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1992.tb00094.x

- Warnakulasuriya KA, Johnson NW. Sensitivity and specificity of OraScan (R) toluidine blue mouthrinse in the detection of oral cancer and precancer. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25:97-103. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb00201.x

- Silapunt S, Peterson SR, Alcalay J, et al. Mohs tissue mapping and processing: a survey study. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:1109-1112; discussion 1112.

- Humphreys TR, Nemeth A, McCrevey S, et al. A pilot study comparing toluidine blue and hematoxylin and eosin staining of basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma during Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:693-697. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00619.x

- Bennett R, Taher M. Restylane persistent for 23 months found during Mohs micrographic surgery: a source of confusion with hyaluronic acid surrounding basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1366-1369. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31223

- Goldberg LH, Wang SQ, Kimyai-Asadi A. The setting sun sign: visualizing the margins of a basal cell carcinoma on serial frozen sections stained with toluidine blue. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:761-763. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33158.x

- Tehrani H, May K, Morris A, et al. Does the dual use of toluidine blue and hematoxylin and eosin staining improve basal cell carcinoma detection by Mohs surgery trainees? Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:995-1000. doi:10.1111/dsu.12180

- Donaldson MR, Weber LA. Toluidine blue supports differentiation of folliculocentric basaloid proliferation from basal cell carcinoma on frozen sections in a small single-practice cohort. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1303-1306. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001107

- Styperek AR, Goldberg LH, Goldschmidt LE, et al. Toluidine blue and hematoxylin and eosin stains are comparable in evaluating squamous cell carcinoma during Mohs. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:1279-1284. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000872

- Trieu D, Drosou A, Goldberg LH, et al. Detecting spindle cell squamous cell carcinomas with toluidine blue on frozen sections. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1259-1260. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000147

- Drosou A, Trieu D, Goldberg LH, et al. The perineural corona sign: enhancing detection of perineural squamous cell carcinoma during Mohs micrographic surgery with toluidine blue stain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:826-827. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.076

- Chesser RS, Bertler DE, Fitzpatrick JE, et al. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery toluidine blue technique. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:175-176. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1992.tb02794.x

- Wang SQ, Goldberg LH, Nemeth A. The merits of adding toluidine blue-stained slides in Mohs surgery in the treatment of a microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:1067-1069. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.01.008

- Chen CL, Wilson S, Afzalneia R, et al. Topical aluminum chloride and Monsel’s solution block toluidine blue staining in Mohs frozen sections: mechanism and solution. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1019-1025. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001761

- Todd MM, Lee JW, Marks VJ. Rapid toluidine blue stain for Mohs’ micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:244-245. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31053

- Picoto AM, Picoto A. Technical procedures for Mohs fresh tissue surgery. J Derm Surg Oncol. 1986;12:134-138. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1986.tb01442.x

- Sperling LC, Winton GB. The transverse anatomy of androgenic alopecia. J Derm Surg Oncol. 1990;16:1127-1133. doi:10.1111/j.1524 -4725.1990.tb00024.x

- Smith-Zagone MJ, Schwartz MR. Frozen section of skin specimens. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:1536-1543. doi:10.5858/2005-129-1536-FSOSS

- Moy RL, Potter TS, Uitto J. Increased glycosaminoglycans production in sclerosing basal cell carcinoma–derived fibroblasts and stimulation of normal skin fibroblast glycosaminoglycans production by a cytokine-derived from sclerosing basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:1029-1036. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.0260111029.x

- Leshin B, White WL. Folliculocentric basaloid proliferation. The bulge (der Wulst) revisited. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:900-906. doi:10.1001/archderm.126.7.900

- Seab JA, Graham JH. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma.J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:113-118. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(87)70182-0

Toluidine blue (TB), a dye with metachromatic staining properties, was developed in 1856 by William Henry Perkin.1 Metachromasia is a perceptible change in the color of staining of living tissue due to the electrochemical properties of the tissue. Tissues that contain high concentrations of ionized sulfate and phosphate groups (high concentrations of free electronegative groups) form polymeric aggregates of the basic dye solution that alter the absorbed wavelengths of light.2 The function of this characteristic is to use a single dye to highlight different structures in tissue based on their relative chemical differences.3

Toluidine blue primarily was used within the dye industry until the 1960s, when it was first used in vital staining of the oral mucosa.2 Because of the tissue absorption potential, this technique was used to detect the location of oral malignancies.4 Since then, TB has progressively been used for staining fresh frozen sections in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). In a 2003 survey study (N=310), 16.8% of surgeons performing MMS reported using TB in their laboratory.5 We sought to systematically review the published literature describing the uses of TB in the setting of fresh frozen sections and MMS.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search of the PubMed and Cochrane databases for articles published before December 1, 2019, to identify any relevant studies in English. Electronic searches were performed using the terms toluidine blue and Mohs or Mohs micrographic surgery. We manually checked the bibliographies of the identified articles to further identify eligible studies.

Eligibility Criteria—The inclusion criteria were articles that (1) considered TB in the context of MMS, (2) were published in peer-reviewed journals, (3) were published in English, and (4) were available as full text. Systematic reviews were excluded.

Data Extraction and Outcomes—All relevant information regarding the study characteristics, including design, level of evidence, methodologic quality of evidence, pathology examined, and outcome measures, were collected by 2 independent reviewers (T.L. and A.D.) using a predetermined data sheet. The same 2 reviewers were used for all steps of the review process, data were independently obtained, and any discrepancy was introduced for a third opinion (D.H.) and agreed upon by the majority.

Quality Assessment—The level of evidence was evaluated based on the criteria of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Two reviewers (T.L. and A.D.) graded each article included in the review.

Results

A total of 25 articles were reviewed. After the titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, 12 articles remained (Figure 1). Of these, 1 compared basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), 4 were related to BCC, 3 were related to SCC, 1 was related to microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), 1 was related to primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma (PCACC), and 2 were related to technical aspects of the staining process (Table 1).

A majority of the articles included in this review were qualitative and observational in nature, describing the staining characteristics of TB. Study characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Comment

Basal Cell Carcinoma—Toluidine blue staining characteristics help to identify BCC nests by differentiating them from hair follicles in frozen sections. The metachromatic characteristic of TB stains the inner root sheath deep blue and highlights the surrounding stromal mucin of BCC a magenta color.18,19 In hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains, these 2 distinct structures can be differentiated by cleft formation around tumor nests, mitotic figures, and the lack of a fibrous sheath present in BCC tumors.20 The advantages and limitations of TB staining of BCC are presented in Table 2.

Humphreys et al6 suggested a noticeable difference between H&E and TB in the staining of cellular and stromal components. The nuclear detail of tumor cells was subjectively sharper and clearer with TB staining. The staining of stromal components may provide the most assistance in locating BCC islands. Mucopolysaccharide staining may be absent in H&E but stain a deep magenta with TB. Although the presence of mucopolysaccharides does not specifically indicate a tumor, it may prompt further attention and provide an indicator for sparse and infiltrative tumor cells.6 The metachromatic stromal change may indicate a narrow tumor-free margin where additional deeper sections often reveal tumor that may warrant additional resection margin in more aggressive malignancies. In particular, sclerosing/morpheaform BCCs have been shown to induce glycosaminoglycan synthesis and are highlighted more readily with TB than with H&E when compared to surrounding tissue.21 This differentiation in staining has remained a popular reason to routinely incorporate TB into the staining of infiltrative and morpheaform variants of BCC. Additionally, stromal mast cells are believed to be more abundant in the stroma of BCC and are more readily visualized in tissue specimens stained with TB, appearing as bright purple metachromatic granules. These granules are larger than normal and are increased in number.6

The margin behavior of BCC stained with TB was further characterized by Goldberg et al,8 who coined the term setting sun sign, which may be present in sequential sections of a disappearing nodule of a BCC tumor. Stroma, inflammatory infiltrate, and mast cells produce a magenta glow surrounding BCC tumors that is reminiscent of a setting sun (Figure 2). Invasive BCC is considered variable in this presentation, primarily because of zones of cell-free fluid and edema or the second area of inflammatory cells. This unique sign may benefit the inspecting Mohs surgeon by providing a clue to an underlying process that may have residual BCC tumors. The setting sun sign also may assist in identifying exact surgical margins.8

The nasal surface has a predilection for BCC.22 The skin of the nose has numerous look-alike structures to consider for complete tumor removal and avoidance of unnecessary removal. One challenge is distinguishing follicular basaloid proliferations (FBP) from BCC, a scenario that is more common on the nose.22 When TB staining was used, the sensitivity for detecting FBP reached 100% in 34 cases reviewed by Donaldson and Weber.10 None of the cases examined showed TB metachromasia surrounding FBP, thus indicating that TB can dependably identify this benign entity. Conversely, 5% (N=279) of BCCs confirmed on H&E did not exhibit surrounding TB metachromasia. This finding is concerning regarding the specificity of TB staining for BCC, but the authors of this study suggested the possibility that these exceptions were benign “simulants” (ie, trichoepithelioma) of BCC.10

The use of TB also has been shown to be statistically beneficial in Mohs training. In a single-center, single-fellow experiment, the sensitivity and specificity of using TB for BCC were extrapolated.9 Using TB as an adjunct in deep sections showed superior sensitivity to H&E alone in identifying BCC, increasing sensitivity from 96.3% to 99.7%. In a cohort of 352 BCC excisions and frozen sections, only 1 BCC was not completely excised. If H&E only had been performed, the fellow would have missed 13 residual BCC tumors.9

Bennett and Taher7 described a case in which hyaluronic acid (HA) from a filler injection was confused with the HA surrounding BCC tumor nests. They found that when TB is used as an adjunct, the HA filler is easier to differentiate from the HA surrounding the BCC tumor nests. In frozen sections stained with TB, the HA filler appeared as an amorphous, metachromatic, reddish-purple, whereas the HA surrounding the BCC tumor nests appeared as a well-defined red. These findings were less obvious in the same sections stained with H&E alone.7

Squamous Cell Carcinoma—In early investigations, the utility of TB in identifying SCC in frozen sections was thought to be limited. The description by Humphreys and colleagues6 of staining characteristics in SCC suggested that the nuclear detail that H&E provides is more easily recognized. The deep aqua nuclear staining produced with TB was considered more difficult to observe than the cytoplasmic eosinophilia of pyknotic and keratinizing cells in H&E.6

Toluidine blue may be beneficial in providing unique staining characteristics to further detail tumors that are difficult to interpret, such as spindle cell SCC and perineural invasion of aggressive SCC. In H&E, squamous cells of spindle cell SCC (scSCC) blend into the background of inflammatory cells and can be perceptibly difficult to locate. A small cohort of 3 Mohs surgeons who routinely use H&E were surveyed on their ability to detect a proven scSCC in H&E or TB by photograph.12 All 3 were able to detect the scSCC in the TB photographs, but only 2 of 3 were able to detect it in H&E photographs. All 3 surgeons agreed that TB was preferable to H&E for this tumor type. These findings suggested that TB may be superior and preferred over H&E for visualizing tumor cells of scSCC.12 The TB staining characteristics of perineural invasion of aggressive SCC have been referred to as the perineural corona sign because of the bright magenta stain that forms around affected nerves.13 Drosou et al13 suggested that TB may enhance the diagnostic accuracy for perineural SCC.

Rare Tumors—The adjunctive use of TB with H&E has been examined in rare tumors. Published reports have highlighted its use in MMS for treating MAC and PCACC. Toluidine blue exhibits staining advantages for these tumors. It may render isolated nests and perineural invasion of MAC more easily visible on frozen section.15

Although PCACC is rare, the recurrence rate is high.23 Toluidine blue has been used with MMS to ensure complete removal and higher cure rates. The metachromatic nature of TB is advantageous in staining the HA present in these tumors. Those who have reported the use of TB for PCACC prefer it to H&E for frozen sections.14

Technical Aspects—The staining time for TB-treated slides is reduced compared to H&E staining; staining can be efficiently done in frozen sections in less than 2.5 minutes using the method shown in Table 3.17 In comparison, typical H&E staining takes 9 minutes, and older TB techniques take 7 minutes.6

Conclusion

Toluidine blue may play an important and helpful role in the successful diagnosis and treatment of particular cutaneous tumors by providing additional diagnostic information. Although surgeons performing MMS will continue using the staining protocols with which they are most comfortable, adjunctive use of TB over time may provide an additional benefit at low risk for disrupting practice efficiency or workflow. Many Mohs surgeons are accustomed to using this stain, even preferring to interpret only TB-stained slides for cutaneous malignancy. Most published studies on this topic have been observational in nature, and additional controlled trials may be warranted to determine the effects on outcomes in real-world practice.

Toluidine blue (TB), a dye with metachromatic staining properties, was developed in 1856 by William Henry Perkin.1 Metachromasia is a perceptible change in the color of staining of living tissue due to the electrochemical properties of the tissue. Tissues that contain high concentrations of ionized sulfate and phosphate groups (high concentrations of free electronegative groups) form polymeric aggregates of the basic dye solution that alter the absorbed wavelengths of light.2 The function of this characteristic is to use a single dye to highlight different structures in tissue based on their relative chemical differences.3

Toluidine blue primarily was used within the dye industry until the 1960s, when it was first used in vital staining of the oral mucosa.2 Because of the tissue absorption potential, this technique was used to detect the location of oral malignancies.4 Since then, TB has progressively been used for staining fresh frozen sections in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). In a 2003 survey study (N=310), 16.8% of surgeons performing MMS reported using TB in their laboratory.5 We sought to systematically review the published literature describing the uses of TB in the setting of fresh frozen sections and MMS.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search of the PubMed and Cochrane databases for articles published before December 1, 2019, to identify any relevant studies in English. Electronic searches were performed using the terms toluidine blue and Mohs or Mohs micrographic surgery. We manually checked the bibliographies of the identified articles to further identify eligible studies.

Eligibility Criteria—The inclusion criteria were articles that (1) considered TB in the context of MMS, (2) were published in peer-reviewed journals, (3) were published in English, and (4) were available as full text. Systematic reviews were excluded.

Data Extraction and Outcomes—All relevant information regarding the study characteristics, including design, level of evidence, methodologic quality of evidence, pathology examined, and outcome measures, were collected by 2 independent reviewers (T.L. and A.D.) using a predetermined data sheet. The same 2 reviewers were used for all steps of the review process, data were independently obtained, and any discrepancy was introduced for a third opinion (D.H.) and agreed upon by the majority.

Quality Assessment—The level of evidence was evaluated based on the criteria of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Two reviewers (T.L. and A.D.) graded each article included in the review.

Results

A total of 25 articles were reviewed. After the titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, 12 articles remained (Figure 1). Of these, 1 compared basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), 4 were related to BCC, 3 were related to SCC, 1 was related to microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), 1 was related to primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma (PCACC), and 2 were related to technical aspects of the staining process (Table 1).

A majority of the articles included in this review were qualitative and observational in nature, describing the staining characteristics of TB. Study characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Comment

Basal Cell Carcinoma—Toluidine blue staining characteristics help to identify BCC nests by differentiating them from hair follicles in frozen sections. The metachromatic characteristic of TB stains the inner root sheath deep blue and highlights the surrounding stromal mucin of BCC a magenta color.18,19 In hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains, these 2 distinct structures can be differentiated by cleft formation around tumor nests, mitotic figures, and the lack of a fibrous sheath present in BCC tumors.20 The advantages and limitations of TB staining of BCC are presented in Table 2.

Humphreys et al6 suggested a noticeable difference between H&E and TB in the staining of cellular and stromal components. The nuclear detail of tumor cells was subjectively sharper and clearer with TB staining. The staining of stromal components may provide the most assistance in locating BCC islands. Mucopolysaccharide staining may be absent in H&E but stain a deep magenta with TB. Although the presence of mucopolysaccharides does not specifically indicate a tumor, it may prompt further attention and provide an indicator for sparse and infiltrative tumor cells.6 The metachromatic stromal change may indicate a narrow tumor-free margin where additional deeper sections often reveal tumor that may warrant additional resection margin in more aggressive malignancies. In particular, sclerosing/morpheaform BCCs have been shown to induce glycosaminoglycan synthesis and are highlighted more readily with TB than with H&E when compared to surrounding tissue.21 This differentiation in staining has remained a popular reason to routinely incorporate TB into the staining of infiltrative and morpheaform variants of BCC. Additionally, stromal mast cells are believed to be more abundant in the stroma of BCC and are more readily visualized in tissue specimens stained with TB, appearing as bright purple metachromatic granules. These granules are larger than normal and are increased in number.6

The margin behavior of BCC stained with TB was further characterized by Goldberg et al,8 who coined the term setting sun sign, which may be present in sequential sections of a disappearing nodule of a BCC tumor. Stroma, inflammatory infiltrate, and mast cells produce a magenta glow surrounding BCC tumors that is reminiscent of a setting sun (Figure 2). Invasive BCC is considered variable in this presentation, primarily because of zones of cell-free fluid and edema or the second area of inflammatory cells. This unique sign may benefit the inspecting Mohs surgeon by providing a clue to an underlying process that may have residual BCC tumors. The setting sun sign also may assist in identifying exact surgical margins.8

The nasal surface has a predilection for BCC.22 The skin of the nose has numerous look-alike structures to consider for complete tumor removal and avoidance of unnecessary removal. One challenge is distinguishing follicular basaloid proliferations (FBP) from BCC, a scenario that is more common on the nose.22 When TB staining was used, the sensitivity for detecting FBP reached 100% in 34 cases reviewed by Donaldson and Weber.10 None of the cases examined showed TB metachromasia surrounding FBP, thus indicating that TB can dependably identify this benign entity. Conversely, 5% (N=279) of BCCs confirmed on H&E did not exhibit surrounding TB metachromasia. This finding is concerning regarding the specificity of TB staining for BCC, but the authors of this study suggested the possibility that these exceptions were benign “simulants” (ie, trichoepithelioma) of BCC.10

The use of TB also has been shown to be statistically beneficial in Mohs training. In a single-center, single-fellow experiment, the sensitivity and specificity of using TB for BCC were extrapolated.9 Using TB as an adjunct in deep sections showed superior sensitivity to H&E alone in identifying BCC, increasing sensitivity from 96.3% to 99.7%. In a cohort of 352 BCC excisions and frozen sections, only 1 BCC was not completely excised. If H&E only had been performed, the fellow would have missed 13 residual BCC tumors.9

Bennett and Taher7 described a case in which hyaluronic acid (HA) from a filler injection was confused with the HA surrounding BCC tumor nests. They found that when TB is used as an adjunct, the HA filler is easier to differentiate from the HA surrounding the BCC tumor nests. In frozen sections stained with TB, the HA filler appeared as an amorphous, metachromatic, reddish-purple, whereas the HA surrounding the BCC tumor nests appeared as a well-defined red. These findings were less obvious in the same sections stained with H&E alone.7

Squamous Cell Carcinoma—In early investigations, the utility of TB in identifying SCC in frozen sections was thought to be limited. The description by Humphreys and colleagues6 of staining characteristics in SCC suggested that the nuclear detail that H&E provides is more easily recognized. The deep aqua nuclear staining produced with TB was considered more difficult to observe than the cytoplasmic eosinophilia of pyknotic and keratinizing cells in H&E.6

Toluidine blue may be beneficial in providing unique staining characteristics to further detail tumors that are difficult to interpret, such as spindle cell SCC and perineural invasion of aggressive SCC. In H&E, squamous cells of spindle cell SCC (scSCC) blend into the background of inflammatory cells and can be perceptibly difficult to locate. A small cohort of 3 Mohs surgeons who routinely use H&E were surveyed on their ability to detect a proven scSCC in H&E or TB by photograph.12 All 3 were able to detect the scSCC in the TB photographs, but only 2 of 3 were able to detect it in H&E photographs. All 3 surgeons agreed that TB was preferable to H&E for this tumor type. These findings suggested that TB may be superior and preferred over H&E for visualizing tumor cells of scSCC.12 The TB staining characteristics of perineural invasion of aggressive SCC have been referred to as the perineural corona sign because of the bright magenta stain that forms around affected nerves.13 Drosou et al13 suggested that TB may enhance the diagnostic accuracy for perineural SCC.

Rare Tumors—The adjunctive use of TB with H&E has been examined in rare tumors. Published reports have highlighted its use in MMS for treating MAC and PCACC. Toluidine blue exhibits staining advantages for these tumors. It may render isolated nests and perineural invasion of MAC more easily visible on frozen section.15

Although PCACC is rare, the recurrence rate is high.23 Toluidine blue has been used with MMS to ensure complete removal and higher cure rates. The metachromatic nature of TB is advantageous in staining the HA present in these tumors. Those who have reported the use of TB for PCACC prefer it to H&E for frozen sections.14

Technical Aspects—The staining time for TB-treated slides is reduced compared to H&E staining; staining can be efficiently done in frozen sections in less than 2.5 minutes using the method shown in Table 3.17 In comparison, typical H&E staining takes 9 minutes, and older TB techniques take 7 minutes.6

Conclusion

Toluidine blue may play an important and helpful role in the successful diagnosis and treatment of particular cutaneous tumors by providing additional diagnostic information. Although surgeons performing MMS will continue using the staining protocols with which they are most comfortable, adjunctive use of TB over time may provide an additional benefit at low risk for disrupting practice efficiency or workflow. Many Mohs surgeons are accustomed to using this stain, even preferring to interpret only TB-stained slides for cutaneous malignancy. Most published studies on this topic have been observational in nature, and additional controlled trials may be warranted to determine the effects on outcomes in real-world practice.

- Culling CF, Allison TR. Cellular Pathology Technique. 4th ed. Butterworths; 1985.

- Bergeron JA, Singer M. Metachromasy: an experimental and theoretical reevaluation. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1958;4:433-457. doi:10.1083/jcb.4.4.433

- Epstein JB, Scully C, Spinelli J. Toluidine blue and Lugol’s iodine application in the assessment of oral malignant disease and lesions at risk of malignancy. J Oral Pathol Med. 1992;21:160-163. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1992.tb00094.x

- Warnakulasuriya KA, Johnson NW. Sensitivity and specificity of OraScan (R) toluidine blue mouthrinse in the detection of oral cancer and precancer. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25:97-103. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb00201.x

- Silapunt S, Peterson SR, Alcalay J, et al. Mohs tissue mapping and processing: a survey study. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:1109-1112; discussion 1112.

- Humphreys TR, Nemeth A, McCrevey S, et al. A pilot study comparing toluidine blue and hematoxylin and eosin staining of basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma during Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:693-697. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00619.x

- Bennett R, Taher M. Restylane persistent for 23 months found during Mohs micrographic surgery: a source of confusion with hyaluronic acid surrounding basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1366-1369. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31223

- Goldberg LH, Wang SQ, Kimyai-Asadi A. The setting sun sign: visualizing the margins of a basal cell carcinoma on serial frozen sections stained with toluidine blue. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:761-763. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33158.x

- Tehrani H, May K, Morris A, et al. Does the dual use of toluidine blue and hematoxylin and eosin staining improve basal cell carcinoma detection by Mohs surgery trainees? Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:995-1000. doi:10.1111/dsu.12180

- Donaldson MR, Weber LA. Toluidine blue supports differentiation of folliculocentric basaloid proliferation from basal cell carcinoma on frozen sections in a small single-practice cohort. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1303-1306. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001107

- Styperek AR, Goldberg LH, Goldschmidt LE, et al. Toluidine blue and hematoxylin and eosin stains are comparable in evaluating squamous cell carcinoma during Mohs. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:1279-1284. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000872

- Trieu D, Drosou A, Goldberg LH, et al. Detecting spindle cell squamous cell carcinomas with toluidine blue on frozen sections. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1259-1260. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000147

- Drosou A, Trieu D, Goldberg LH, et al. The perineural corona sign: enhancing detection of perineural squamous cell carcinoma during Mohs micrographic surgery with toluidine blue stain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:826-827. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.076

- Chesser RS, Bertler DE, Fitzpatrick JE, et al. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery toluidine blue technique. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:175-176. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1992.tb02794.x

- Wang SQ, Goldberg LH, Nemeth A. The merits of adding toluidine blue-stained slides in Mohs surgery in the treatment of a microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:1067-1069. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.01.008

- Chen CL, Wilson S, Afzalneia R, et al. Topical aluminum chloride and Monsel’s solution block toluidine blue staining in Mohs frozen sections: mechanism and solution. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1019-1025. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001761

- Todd MM, Lee JW, Marks VJ. Rapid toluidine blue stain for Mohs’ micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:244-245. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31053

- Picoto AM, Picoto A. Technical procedures for Mohs fresh tissue surgery. J Derm Surg Oncol. 1986;12:134-138. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1986.tb01442.x

- Sperling LC, Winton GB. The transverse anatomy of androgenic alopecia. J Derm Surg Oncol. 1990;16:1127-1133. doi:10.1111/j.1524 -4725.1990.tb00024.x

- Smith-Zagone MJ, Schwartz MR. Frozen section of skin specimens. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:1536-1543. doi:10.5858/2005-129-1536-FSOSS

- Moy RL, Potter TS, Uitto J. Increased glycosaminoglycans production in sclerosing basal cell carcinoma–derived fibroblasts and stimulation of normal skin fibroblast glycosaminoglycans production by a cytokine-derived from sclerosing basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:1029-1036. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.0260111029.x

- Leshin B, White WL. Folliculocentric basaloid proliferation. The bulge (der Wulst) revisited. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:900-906. doi:10.1001/archderm.126.7.900

- Seab JA, Graham JH. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma.J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:113-118. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(87)70182-0

- Culling CF, Allison TR. Cellular Pathology Technique. 4th ed. Butterworths; 1985.

- Bergeron JA, Singer M. Metachromasy: an experimental and theoretical reevaluation. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1958;4:433-457. doi:10.1083/jcb.4.4.433

- Epstein JB, Scully C, Spinelli J. Toluidine blue and Lugol’s iodine application in the assessment of oral malignant disease and lesions at risk of malignancy. J Oral Pathol Med. 1992;21:160-163. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1992.tb00094.x

- Warnakulasuriya KA, Johnson NW. Sensitivity and specificity of OraScan (R) toluidine blue mouthrinse in the detection of oral cancer and precancer. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25:97-103. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb00201.x

- Silapunt S, Peterson SR, Alcalay J, et al. Mohs tissue mapping and processing: a survey study. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:1109-1112; discussion 1112.

- Humphreys TR, Nemeth A, McCrevey S, et al. A pilot study comparing toluidine blue and hematoxylin and eosin staining of basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma during Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:693-697. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00619.x

- Bennett R, Taher M. Restylane persistent for 23 months found during Mohs micrographic surgery: a source of confusion with hyaluronic acid surrounding basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1366-1369. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31223

- Goldberg LH, Wang SQ, Kimyai-Asadi A. The setting sun sign: visualizing the margins of a basal cell carcinoma on serial frozen sections stained with toluidine blue. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:761-763. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33158.x

- Tehrani H, May K, Morris A, et al. Does the dual use of toluidine blue and hematoxylin and eosin staining improve basal cell carcinoma detection by Mohs surgery trainees? Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:995-1000. doi:10.1111/dsu.12180

- Donaldson MR, Weber LA. Toluidine blue supports differentiation of folliculocentric basaloid proliferation from basal cell carcinoma on frozen sections in a small single-practice cohort. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1303-1306. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001107

- Styperek AR, Goldberg LH, Goldschmidt LE, et al. Toluidine blue and hematoxylin and eosin stains are comparable in evaluating squamous cell carcinoma during Mohs. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:1279-1284. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000872

- Trieu D, Drosou A, Goldberg LH, et al. Detecting spindle cell squamous cell carcinomas with toluidine blue on frozen sections. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1259-1260. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000147

- Drosou A, Trieu D, Goldberg LH, et al. The perineural corona sign: enhancing detection of perineural squamous cell carcinoma during Mohs micrographic surgery with toluidine blue stain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:826-827. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.076

- Chesser RS, Bertler DE, Fitzpatrick JE, et al. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery toluidine blue technique. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:175-176. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1992.tb02794.x

- Wang SQ, Goldberg LH, Nemeth A. The merits of adding toluidine blue-stained slides in Mohs surgery in the treatment of a microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:1067-1069. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.01.008

- Chen CL, Wilson S, Afzalneia R, et al. Topical aluminum chloride and Monsel’s solution block toluidine blue staining in Mohs frozen sections: mechanism and solution. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1019-1025. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001761

- Todd MM, Lee JW, Marks VJ. Rapid toluidine blue stain for Mohs’ micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:244-245. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31053

- Picoto AM, Picoto A. Technical procedures for Mohs fresh tissue surgery. J Derm Surg Oncol. 1986;12:134-138. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1986.tb01442.x

- Sperling LC, Winton GB. The transverse anatomy of androgenic alopecia. J Derm Surg Oncol. 1990;16:1127-1133. doi:10.1111/j.1524 -4725.1990.tb00024.x

- Smith-Zagone MJ, Schwartz MR. Frozen section of skin specimens. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:1536-1543. doi:10.5858/2005-129-1536-FSOSS

- Moy RL, Potter TS, Uitto J. Increased glycosaminoglycans production in sclerosing basal cell carcinoma–derived fibroblasts and stimulation of normal skin fibroblast glycosaminoglycans production by a cytokine-derived from sclerosing basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:1029-1036. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.0260111029.x

- Leshin B, White WL. Folliculocentric basaloid proliferation. The bulge (der Wulst) revisited. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:900-906. doi:10.1001/archderm.126.7.900

- Seab JA, Graham JH. Primary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma.J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:113-118. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(87)70182-0

Practice Points

- Toluidine blue (TB) staining can be integrated into Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) for enhanced diagnosis of cutaneous tumors. Its metachromatic properties can aid in differentiating tumor cells from surrounding tissues, especially in basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas.

- It is important to develop expertise in interpreting TB-stained sections, as it may offer clearer visualization of nuclear details and stromal components, potentially leading to more accurate diagnosis and effective tumor margin identification.

- Toluidine blue staining can be incorporated into routine MMS practice considering its quick staining process and low disruption to workflow. This can potentially improve diagnostic efficiency without significantly lengthening surgery time.

Paradoxical Reaction to TNF-α Inhibitor Therapy in a Patient With Hidradenitis Suppurativa

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the pilosebaceous unit that occurs in concert with elevations of various cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-1β, IL-10, and IL-17.1,2 Adalimumab is a TNF-α inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HS. Although TNF-α inhibitors are effective for many immune-mediated inflammatory disorders, paradoxical drug reactions have been reported following treatment with these agents.3-6 True paradoxical drug reactions likely are immune mediated and directly lead to new onset of a pathologic condition that would otherwise respond to that drug. For example, there are reports of rheumatoid arthritis patients who were treated with a TNF-α inhibitor and developed psoriatic skin lesions.3,6 Paradoxical drug reactions also have been reported with acute-onset inflammatory bowel disease and HS or less commonly pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), uveitis, granulomatous reactions, and vasculitis.4,5 We present the case of a patient with HS who was treated with a TNF-α inhibitor and developed 2 distinct paradoxical drug reactions. We also provide an overview of paradoxical drug reactions associated with TNF-α inhibitors.

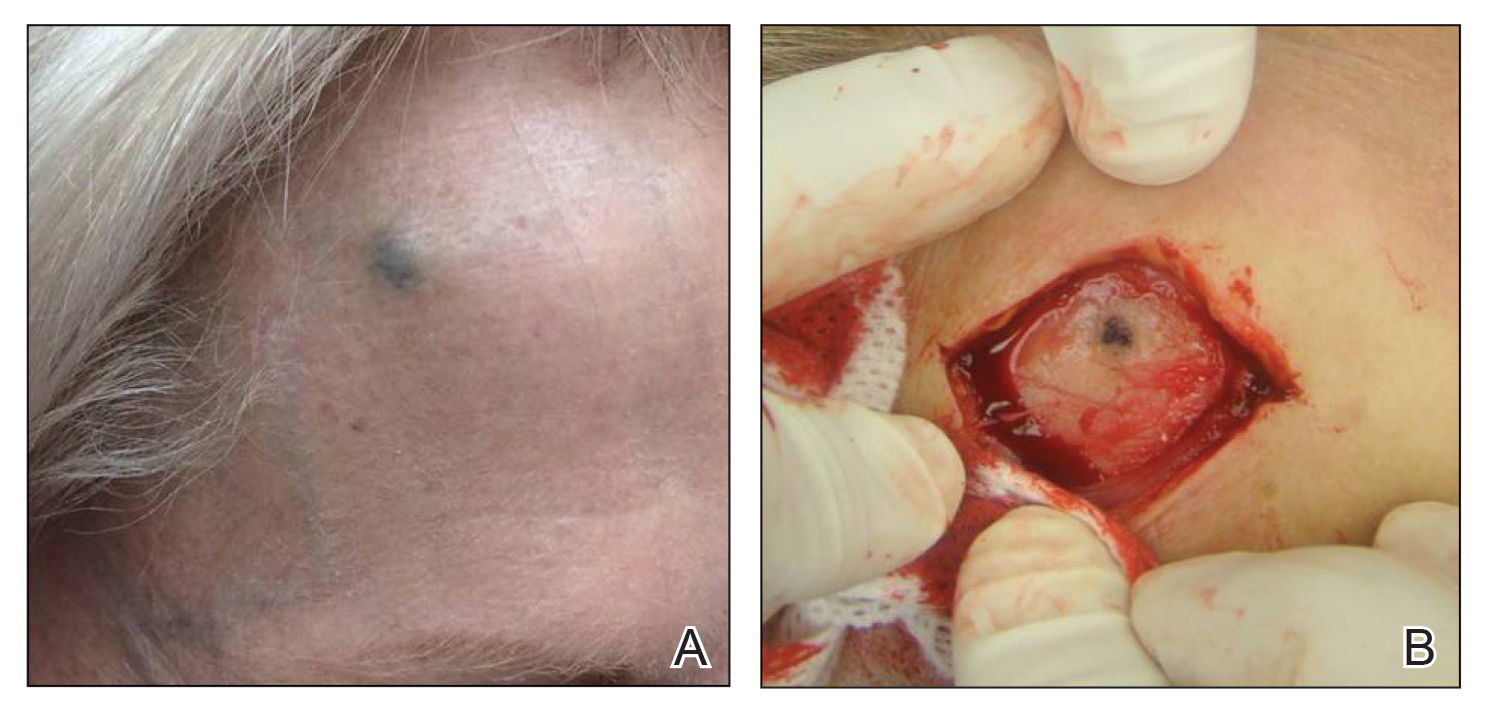

A 38-year-old woman developed a painful “boil” on the right leg that was previously treated in the emergency department with incision and drainage as well as oral clindamycin for 7 days, but the lesion spread and continued to worsen. She had a history of HS in the axillae and groin region that had been present since 12 years of age. The condition was poorly controlled despite multiple courses of oral antibiotics and surgical resections. An oral contraceptive also was attempted, but the patient discontinued treatment when liver enzyme levels became elevated. The patient had no other notable medical history, including skin disease. There was a family history of HS in her father and a sibling. Seeking more effective treatment, the patient was offered adalimumab approximately 4 months prior to clinical presentation and agreed to start a course of the drug. She received a loading dose of 160 mg on day 1 and 80 mg on day 15 followed by a maintenance dosage of 40 mg weekly. She experienced improvement in HS symptoms after 3 months on adalimumab; however, she developed scaly pruritic patches on the scalp, arms, and legs that were consistent with psoriasis. Because of the absence of a personal or family history of psoriasis, the patient was informed of the probability of paradoxical psoriasis resulting from adalimumab. She elected to continue adalimumab because of the improvement in HS symptoms, and the psoriatic lesions were mild and adequately controlled with a topical steroid.

At the current presentation 1 month later, physical examination revealed a large indurated and ulcerated area with jagged edges at the incision and drainage site (Figure 1). Pyoderma gangrenosum was clinically suspected; a biopsy was performed, and the patient was started on oral prednisone. At 2-week follow-up, the ulcer was found to be rapidly resolving with prednisone and healing with cribriform scarring (Figure 2). Histopathology revealed an undermining neutrophilic inflammatory process that was consistent with PG. A diagnosis of PG was made based on previously published criteria7 and the following major/minor criteria in the patient: pathology; absence of infection on histologic analysis; history of pathergy related to worsening ulceration at the site of incision and drainage of the initial boil; clinical findings of an ulcer with peripheral violaceous erythema; undermined borders and tenderness at the site; and rapid resolution of the ulcer with prednisone.

Cessation of adalimumab gradually led to clearance of both psoriasiform lesions and PG; however, HS lesions persisted.

Although the precise pathogenesis of HS is unclear, both genetic abnormalities of the pilosebaceous unit and a dysregulated immune reaction appear to lead to the clinical characteristics of chronic inflammation and scarring seen in HS. A key effector appears to be helper T-cell (TH17) lymphocyte activation, with increased secretion of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-17.1,2 In turn, IL-17 induces higher expression of TNF-α, leading to a persistent cycle of inflammation. Peripheral recruitment of IL-17–producing neutrophils also may contribute to chronic inflammation.8

Adalimumab is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic indicated for the treatment of HS. Our patient initially responded to adalimumab with improvement of HS; however, treatment had to be discontinued because of the unusual occurrence of 2 distinct paradoxical reactions in a short span of time. Psoriasis and PG are both considered true paradoxical reactions because primary occurrences of both diseases usually are responsive to treatment with adalimumab.

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis arises de novo and is estimated to occur in approximately 5% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.3,6 Palmoplantar pustular psoriasiform reactions are the most common form of paradoxical psoriasis. Topical medications can be used to treat skin lesions, but systemic treatment is required in many cases. Switching to an alternate class of a biologic, such as an IL-17, IL-12/23, or IL-23 inhibitor, can improve the skin reaction; however, such treatment is inconsistently successful, and paradoxical drug reactions also have been seen with these other classes of biologics.4,9

Recent studies support distinct immune causes for classical and paradoxical psoriasis. In classical psoriasis, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) produce IFN-α, which stimulates conventional dendritic cells to produce TNF-α. However, TNF-α matures both pDCs and conventional dendritic cells; upon maturation, both types of dendritic cells lose the ability to produce IFN-α, thus allowing TNF-α to become dominant.10 The blockade of TNF-α prevents pDC maturation, leading to uninhibited IFN-α, which appears to drive inflammation in paradoxical psoriasis. In classical psoriasis, oligoclonal dermal CD4+ T cells and epidermal CD8+ T cells remain, even in resolved skin lesions, and can cause disease recurrence through reactivation of skin-resident memory T cells.11 No relapse of paradoxical psoriasis occurs with discontinuation of anti-TNF-α therapy, which supports the notion of an absence of memory T cells.

The incidence of paradoxical psoriasis in patients receiving a TNF-α inhibitor for HS is unclear.12 There are case series in which patients who had concurrent psoriasis and HS were successfully treated with a TNF-α inhibitor.13 A recently recognized condition—PASH syndrome—encompasses the clinical triad of PG, acne, and HS.10

Our patient had no history of acne or PG, only a long-standing history of HS. New-onset PG occurred only after a TNF-α inhibitor was initiated. Notably, PASH syndrome has been successfully treated with TNF-α inhibitors, highlighting the shared inflammatory etiology of HS and PG.14 In patients with concurrent PG and HS, TNF-α inhibitors were more effective for treating PG than for HS.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is an inflammatory disorder that often occurs concomitantly with other conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease. The exact underlying cause of PG is unclear, but there appears to be both neutrophil and T-cell dysfunction in PG, with excess inflammatory cytokine production (eg, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-17).15

The mainstay of treatment of PG is systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressives, such as cyclosporine. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors as well as other interleukin inhibitors are increasingly utilized as potential therapeutic alternatives for PG.16,17

Unlike paradoxical psoriasis, the underlying cause of paradoxical PG is unclear.18,19 A similar mechanism may be postulated whereby inhibition of TNF-α leads to excessive activation of alternative inflammatory pathways that result in paradoxical PG. In one study, the prevalence of PG among 68,232 patients with HS was 0.18% compared with 0.01% among those without HS; therefore, patients with HS appear to be more predisposed to PG.20

This case illustrates the complex, often conflicting effects of cytokine inhibition in the paradoxical elicitation of alternative inflammatory disorders as an unintended consequence of the initial cytokine blockade. It is likely that genetic predisposition allows for paradoxical reactions in some patients when there is predominant inhibition of one cytokine in the inflammatory pathway. In rare cases, multiple paradoxical reactions are possible.

1. Vossen ARJV, van der Zee HH, Prens EP. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review integrating inflammatory pathways into a cohesive pathogenic model. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2965. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02965

2. Goldburg SR, Strober BE, Payette MJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology, clinical presentation and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020; 82:1045-1058. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.090

3. Brown G, Wang E, Leon A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis: systematic review of clinical features, histopathological findings, and management experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:334-341. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.012

4. Puig L. Paradoxical reactions: anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agents, ustekinumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab and others. Curr Prob Dermatol. 2018;53:49-63. doi:10.1159/000479475

5. Faivre C, Villani AP, Aubin F, et al; . Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): an unrecognized paradoxical effect of biologic agents (BA) used in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1153-1159. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.018

6. Ko JM, Gottlieb AB, Kerbleski JF. Induction and exacerbation of psoriasis with TNF-blockade therapy: a review and analysis of 127 cases. J Dermatolog Treat. 2009;20:100-108. doi:10.1080/09546630802441234

7. Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:461-466. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5980

8. Lima AL, Karl I, Giner T, et al. Keratinocytes and neutrophils are important sources of proinflammatory molecules in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:514-521. doi:10.1111/bjd.14214

9. Li SJ, Perez-Chada LM, Merola JF. TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis: proposed algorithm for treatment and management. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2019;4:70-80. doi:10.1177/2475530318810851

10. Conrad C, Di Domizio J, Mylonas A, et al. TNF blockade induces a dysregulated type I interferon response without autoimmunity in paradoxical psoriasis. Nat Commun. 2018;9:25. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02466-4

11. Matos TR, O’Malley JT, Lowry EL, et al. Clinically resolved psoriatic lesions contain psoriasis-specific IL-17-producing αβ T cell clones. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:4031-4041. doi:10.1172/JCI93396

12. Faivre C, Villani AP, Aubin F, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): an unrecognized paradoxical effect of biologic agents (BA) used in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1153-1159. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.018

13. Marzano AV, Damiani G, Ceccherini I, et al. Autoinflammation in pyoderma gangrenosum and its syndromic form (pyoderma gangrenosum, acne and suppurative hidradenitis). Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1588-1598. doi:10.1111/bjd.15226

14. Cugno M, Borghi A, Marzano AV. PAPA, PASH, PAPASH syndromes: pathophysiology, presentation and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:555-562. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0265-1

15. Wang EA, Steel A, Luxardi G, et al. Classic ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum is a T cell-mediated disease targeting follicular adnexal structures: a hypothesis based on molecular and clinicopathologic studies. Front Immunol. 2018;8:1980. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01980

16. Patel F, Fitzmaurice S, Duong C, et al. Effective strategies for the management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:525-531. doi:10.2340/00015555-2008

17. Partridge ACR, Bai JW, Rosen CF, et al. Effectiveness of systemic treatments for pyoderma gangrenosum: a systematic review of observational studies and clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:290-295. doi:10.1111/bjd.16485

18. Benzaquen M, Monnier J, Beaussault Y, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum arising during treatment of psoriasis with adalimumab: effectiveness of ustekinumab. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:e270-e271. doi:10.1111/ajd.12545

19. Fujimoto N, Yamasaki Y, Watanabe RJ. Paradoxical uveitis and pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with psoriatic arthritis under infliximab treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:1139-1140. doi:10.1111/ddg.13632

20. Tannenbaum R, Strunk A, Garg A. Overall and subgroup prevalence of pyoderma gangrenosum among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a population-based analysis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1533-1537. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.004

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the pilosebaceous unit that occurs in concert with elevations of various cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-1β, IL-10, and IL-17.1,2 Adalimumab is a TNF-α inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HS. Although TNF-α inhibitors are effective for many immune-mediated inflammatory disorders, paradoxical drug reactions have been reported following treatment with these agents.3-6 True paradoxical drug reactions likely are immune mediated and directly lead to new onset of a pathologic condition that would otherwise respond to that drug. For example, there are reports of rheumatoid arthritis patients who were treated with a TNF-α inhibitor and developed psoriatic skin lesions.3,6 Paradoxical drug reactions also have been reported with acute-onset inflammatory bowel disease and HS or less commonly pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), uveitis, granulomatous reactions, and vasculitis.4,5 We present the case of a patient with HS who was treated with a TNF-α inhibitor and developed 2 distinct paradoxical drug reactions. We also provide an overview of paradoxical drug reactions associated with TNF-α inhibitors.

A 38-year-old woman developed a painful “boil” on the right leg that was previously treated in the emergency department with incision and drainage as well as oral clindamycin for 7 days, but the lesion spread and continued to worsen. She had a history of HS in the axillae and groin region that had been present since 12 years of age. The condition was poorly controlled despite multiple courses of oral antibiotics and surgical resections. An oral contraceptive also was attempted, but the patient discontinued treatment when liver enzyme levels became elevated. The patient had no other notable medical history, including skin disease. There was a family history of HS in her father and a sibling. Seeking more effective treatment, the patient was offered adalimumab approximately 4 months prior to clinical presentation and agreed to start a course of the drug. She received a loading dose of 160 mg on day 1 and 80 mg on day 15 followed by a maintenance dosage of 40 mg weekly. She experienced improvement in HS symptoms after 3 months on adalimumab; however, she developed scaly pruritic patches on the scalp, arms, and legs that were consistent with psoriasis. Because of the absence of a personal or family history of psoriasis, the patient was informed of the probability of paradoxical psoriasis resulting from adalimumab. She elected to continue adalimumab because of the improvement in HS symptoms, and the psoriatic lesions were mild and adequately controlled with a topical steroid.

At the current presentation 1 month later, physical examination revealed a large indurated and ulcerated area with jagged edges at the incision and drainage site (Figure 1). Pyoderma gangrenosum was clinically suspected; a biopsy was performed, and the patient was started on oral prednisone. At 2-week follow-up, the ulcer was found to be rapidly resolving with prednisone and healing with cribriform scarring (Figure 2). Histopathology revealed an undermining neutrophilic inflammatory process that was consistent with PG. A diagnosis of PG was made based on previously published criteria7 and the following major/minor criteria in the patient: pathology; absence of infection on histologic analysis; history of pathergy related to worsening ulceration at the site of incision and drainage of the initial boil; clinical findings of an ulcer with peripheral violaceous erythema; undermined borders and tenderness at the site; and rapid resolution of the ulcer with prednisone.

Cessation of adalimumab gradually led to clearance of both psoriasiform lesions and PG; however, HS lesions persisted.

Although the precise pathogenesis of HS is unclear, both genetic abnormalities of the pilosebaceous unit and a dysregulated immune reaction appear to lead to the clinical characteristics of chronic inflammation and scarring seen in HS. A key effector appears to be helper T-cell (TH17) lymphocyte activation, with increased secretion of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-17.1,2 In turn, IL-17 induces higher expression of TNF-α, leading to a persistent cycle of inflammation. Peripheral recruitment of IL-17–producing neutrophils also may contribute to chronic inflammation.8

Adalimumab is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic indicated for the treatment of HS. Our patient initially responded to adalimumab with improvement of HS; however, treatment had to be discontinued because of the unusual occurrence of 2 distinct paradoxical reactions in a short span of time. Psoriasis and PG are both considered true paradoxical reactions because primary occurrences of both diseases usually are responsive to treatment with adalimumab.

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis arises de novo and is estimated to occur in approximately 5% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.3,6 Palmoplantar pustular psoriasiform reactions are the most common form of paradoxical psoriasis. Topical medications can be used to treat skin lesions, but systemic treatment is required in many cases. Switching to an alternate class of a biologic, such as an IL-17, IL-12/23, or IL-23 inhibitor, can improve the skin reaction; however, such treatment is inconsistently successful, and paradoxical drug reactions also have been seen with these other classes of biologics.4,9

Recent studies support distinct immune causes for classical and paradoxical psoriasis. In classical psoriasis, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) produce IFN-α, which stimulates conventional dendritic cells to produce TNF-α. However, TNF-α matures both pDCs and conventional dendritic cells; upon maturation, both types of dendritic cells lose the ability to produce IFN-α, thus allowing TNF-α to become dominant.10 The blockade of TNF-α prevents pDC maturation, leading to uninhibited IFN-α, which appears to drive inflammation in paradoxical psoriasis. In classical psoriasis, oligoclonal dermal CD4+ T cells and epidermal CD8+ T cells remain, even in resolved skin lesions, and can cause disease recurrence through reactivation of skin-resident memory T cells.11 No relapse of paradoxical psoriasis occurs with discontinuation of anti-TNF-α therapy, which supports the notion of an absence of memory T cells.

The incidence of paradoxical psoriasis in patients receiving a TNF-α inhibitor for HS is unclear.12 There are case series in which patients who had concurrent psoriasis and HS were successfully treated with a TNF-α inhibitor.13 A recently recognized condition—PASH syndrome—encompasses the clinical triad of PG, acne, and HS.10

Our patient had no history of acne or PG, only a long-standing history of HS. New-onset PG occurred only after a TNF-α inhibitor was initiated. Notably, PASH syndrome has been successfully treated with TNF-α inhibitors, highlighting the shared inflammatory etiology of HS and PG.14 In patients with concurrent PG and HS, TNF-α inhibitors were more effective for treating PG than for HS.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is an inflammatory disorder that often occurs concomitantly with other conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease. The exact underlying cause of PG is unclear, but there appears to be both neutrophil and T-cell dysfunction in PG, with excess inflammatory cytokine production (eg, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-17).15

The mainstay of treatment of PG is systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressives, such as cyclosporine. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors as well as other interleukin inhibitors are increasingly utilized as potential therapeutic alternatives for PG.16,17

Unlike paradoxical psoriasis, the underlying cause of paradoxical PG is unclear.18,19 A similar mechanism may be postulated whereby inhibition of TNF-α leads to excessive activation of alternative inflammatory pathways that result in paradoxical PG. In one study, the prevalence of PG among 68,232 patients with HS was 0.18% compared with 0.01% among those without HS; therefore, patients with HS appear to be more predisposed to PG.20