User login

Enhancing Cosmetic and Functional Improvement of Recalcitrant Nail Lichen Planus With Resin Nail

Practice Gap

Lichen planus (LP)—a chronic inflammatory disorder affecting the nails—is prevalent in 10% to 15% of patients and is more common in the fingernails than toenails. Clinical manifestation includes longitudinal ridges, nail plate atrophy, and splitting, which all contribute to cosmetic disfigurement and difficulty with functionality. Quality of life and daily activities may be impacted profoundly.1 First-line therapies include intralesional and systemic corticosteroids; however, efficacy is limited and recurrence is common.1,2 Lichen planus is one of the few conditions that may cause permanent and debilitating nail loss.

Tools

A resin nail can be used to improve cosmetic appearance and functionality in patients with recalcitrant nail LP. The composite resin creates a flexible nonporous nail and allows the underlying natural nail to grow. Application of resin nails has been used for toenail onychodystrophies to improve cosmesis and functionality but has not been reported for fingernails. The resin typically lasts 6 to 8 weeks on toenails.

The Technique

Application of a resin nail involves several steps (see video online). First, the affected nail should be debrided and a bonding agent applied. Next, multiple layers of resin are applied until the patient’s desired thickness is achieved (typically 2 layers), followed by a sealing agent. Finally, the nail is cured with UV light. We recommend applying sunscreen to the hand(s) prior to curing with UV light. The liquid resin allows the nail to be customized to the patient’s desired length and shape. The overall procedure takes approximately 20 minutes for a single nail.

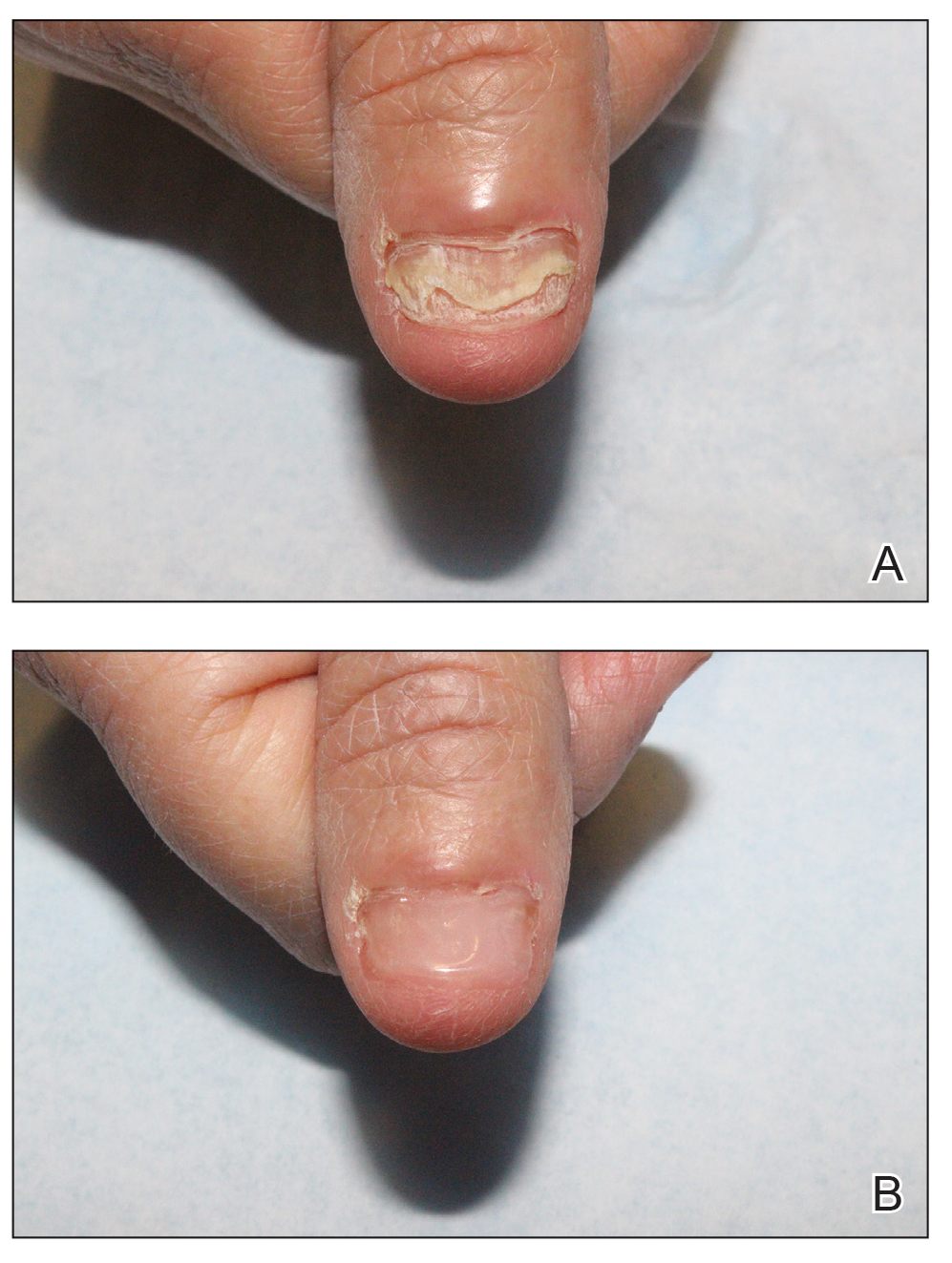

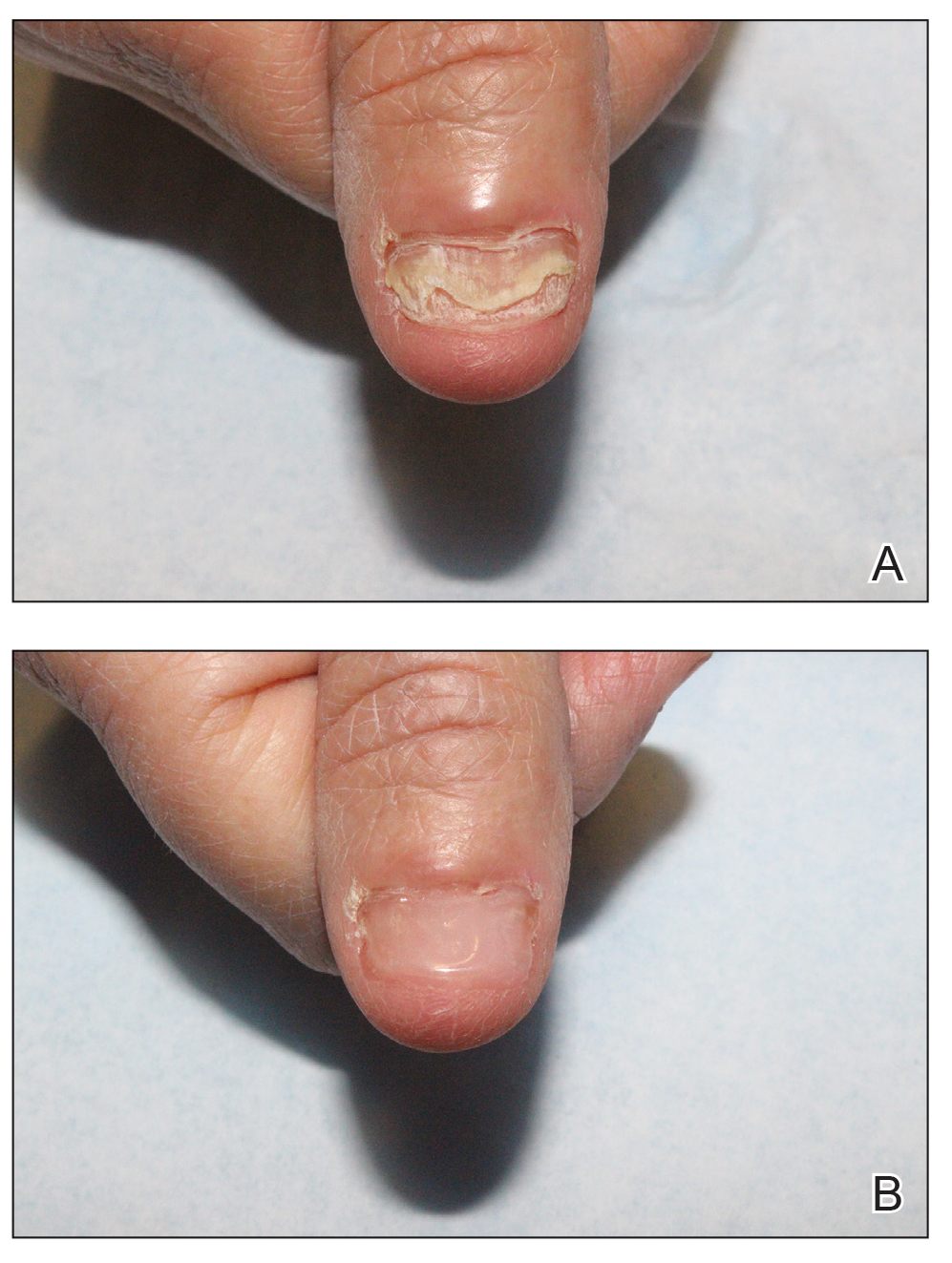

We applied resin nail to the thumbnail of a 46-year-old woman with recalcitrant isolated nail LP of 7 years’ duration (Figure). She previously had difficulties performing everyday activities, and the resin improved her functionality. She also was pleased with the cosmetic appearance. After 2 weeks, the resin started falling off with corresponding natural nail growth. The patient denied any adverse events.

Practice Implications

Resin nail application may serve as a temporary solution to improve cosmesis and functionality in patients with recalcitrant nail LP. As shown in our patient, the resin may fall off faster on the fingernails than the toenails, likely because of the faster growth rate of fingernails and more frequent exposure from daily activities. Further studies of resin nail application for the fingernails are needed to establish duration in patients with varying levels of activity (eg, washing dishes, woodworking).

Because the resin nail may be removed easily at any time, resin nail application does not interfere with treatments such as intralesional steroid injections. For patients using a topical medication regimen, the resin nail may be applied slightly distal to the cuticle so that the medication can still be applied by the proximal nail fold of the underlying natural nail.

The resin nail should be kept short and removed after 2 to 4 weeks for the fingernails and 6 to 8 weeks for the toenails to examine the underlying natural nail. Patients may go about their daily activities with the resin nail, including applying nail polish to the resin nail, bathing, and swimming. Resin nail application may complement medical treatments and improve quality of life for patients with nail LP.

- Gupta MK, Lipner SR. Review of nail lichen planus: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:221-230. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.12.002

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A, Starace M, et al. Isolated nail lichen planus: an expert consensus on treatment of the classical form. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1717-1723. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.056

Practice Gap

Lichen planus (LP)—a chronic inflammatory disorder affecting the nails—is prevalent in 10% to 15% of patients and is more common in the fingernails than toenails. Clinical manifestation includes longitudinal ridges, nail plate atrophy, and splitting, which all contribute to cosmetic disfigurement and difficulty with functionality. Quality of life and daily activities may be impacted profoundly.1 First-line therapies include intralesional and systemic corticosteroids; however, efficacy is limited and recurrence is common.1,2 Lichen planus is one of the few conditions that may cause permanent and debilitating nail loss.

Tools

A resin nail can be used to improve cosmetic appearance and functionality in patients with recalcitrant nail LP. The composite resin creates a flexible nonporous nail and allows the underlying natural nail to grow. Application of resin nails has been used for toenail onychodystrophies to improve cosmesis and functionality but has not been reported for fingernails. The resin typically lasts 6 to 8 weeks on toenails.

The Technique

Application of a resin nail involves several steps (see video online). First, the affected nail should be debrided and a bonding agent applied. Next, multiple layers of resin are applied until the patient’s desired thickness is achieved (typically 2 layers), followed by a sealing agent. Finally, the nail is cured with UV light. We recommend applying sunscreen to the hand(s) prior to curing with UV light. The liquid resin allows the nail to be customized to the patient’s desired length and shape. The overall procedure takes approximately 20 minutes for a single nail.

We applied resin nail to the thumbnail of a 46-year-old woman with recalcitrant isolated nail LP of 7 years’ duration (Figure). She previously had difficulties performing everyday activities, and the resin improved her functionality. She also was pleased with the cosmetic appearance. After 2 weeks, the resin started falling off with corresponding natural nail growth. The patient denied any adverse events.

Practice Implications

Resin nail application may serve as a temporary solution to improve cosmesis and functionality in patients with recalcitrant nail LP. As shown in our patient, the resin may fall off faster on the fingernails than the toenails, likely because of the faster growth rate of fingernails and more frequent exposure from daily activities. Further studies of resin nail application for the fingernails are needed to establish duration in patients with varying levels of activity (eg, washing dishes, woodworking).

Because the resin nail may be removed easily at any time, resin nail application does not interfere with treatments such as intralesional steroid injections. For patients using a topical medication regimen, the resin nail may be applied slightly distal to the cuticle so that the medication can still be applied by the proximal nail fold of the underlying natural nail.

The resin nail should be kept short and removed after 2 to 4 weeks for the fingernails and 6 to 8 weeks for the toenails to examine the underlying natural nail. Patients may go about their daily activities with the resin nail, including applying nail polish to the resin nail, bathing, and swimming. Resin nail application may complement medical treatments and improve quality of life for patients with nail LP.

Practice Gap

Lichen planus (LP)—a chronic inflammatory disorder affecting the nails—is prevalent in 10% to 15% of patients and is more common in the fingernails than toenails. Clinical manifestation includes longitudinal ridges, nail plate atrophy, and splitting, which all contribute to cosmetic disfigurement and difficulty with functionality. Quality of life and daily activities may be impacted profoundly.1 First-line therapies include intralesional and systemic corticosteroids; however, efficacy is limited and recurrence is common.1,2 Lichen planus is one of the few conditions that may cause permanent and debilitating nail loss.

Tools

A resin nail can be used to improve cosmetic appearance and functionality in patients with recalcitrant nail LP. The composite resin creates a flexible nonporous nail and allows the underlying natural nail to grow. Application of resin nails has been used for toenail onychodystrophies to improve cosmesis and functionality but has not been reported for fingernails. The resin typically lasts 6 to 8 weeks on toenails.

The Technique

Application of a resin nail involves several steps (see video online). First, the affected nail should be debrided and a bonding agent applied. Next, multiple layers of resin are applied until the patient’s desired thickness is achieved (typically 2 layers), followed by a sealing agent. Finally, the nail is cured with UV light. We recommend applying sunscreen to the hand(s) prior to curing with UV light. The liquid resin allows the nail to be customized to the patient’s desired length and shape. The overall procedure takes approximately 20 minutes for a single nail.

We applied resin nail to the thumbnail of a 46-year-old woman with recalcitrant isolated nail LP of 7 years’ duration (Figure). She previously had difficulties performing everyday activities, and the resin improved her functionality. She also was pleased with the cosmetic appearance. After 2 weeks, the resin started falling off with corresponding natural nail growth. The patient denied any adverse events.

Practice Implications

Resin nail application may serve as a temporary solution to improve cosmesis and functionality in patients with recalcitrant nail LP. As shown in our patient, the resin may fall off faster on the fingernails than the toenails, likely because of the faster growth rate of fingernails and more frequent exposure from daily activities. Further studies of resin nail application for the fingernails are needed to establish duration in patients with varying levels of activity (eg, washing dishes, woodworking).

Because the resin nail may be removed easily at any time, resin nail application does not interfere with treatments such as intralesional steroid injections. For patients using a topical medication regimen, the resin nail may be applied slightly distal to the cuticle so that the medication can still be applied by the proximal nail fold of the underlying natural nail.

The resin nail should be kept short and removed after 2 to 4 weeks for the fingernails and 6 to 8 weeks for the toenails to examine the underlying natural nail. Patients may go about their daily activities with the resin nail, including applying nail polish to the resin nail, bathing, and swimming. Resin nail application may complement medical treatments and improve quality of life for patients with nail LP.

- Gupta MK, Lipner SR. Review of nail lichen planus: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:221-230. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.12.002

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A, Starace M, et al. Isolated nail lichen planus: an expert consensus on treatment of the classical form. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1717-1723. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.056

- Gupta MK, Lipner SR. Review of nail lichen planus: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:221-230. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.12.002

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A, Starace M, et al. Isolated nail lichen planus: an expert consensus on treatment of the classical form. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1717-1723. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.056

Minimally Invasive Nail Surgery: Techniques to Improve the Patient Experience

Nail surgical procedures including biopsies, correction of onychocryptosis and other deformities, and excision of tumors are essential for diagnosing and treating nail disorders. Nail surgery often is perceived by dermatologists as a difficult-to-perform, high-risk procedure associated with patient anxiety, pain, and permanent scarring, which may limit implementation. Misconceptions about nail surgical techniques, aftercare, and patient outcomes are prevalent, and a paucity of nail surgery randomized clinical trials hinder formulation of standardized guidelines.1 In a survey-based study of 95 dermatology residency programs (240 total respondents), 58% of residents said they performed 10 or fewer nail procedures, 10% performed more than 10 procedures, 25% only observed nail procedures, 4% were exposed by lecture only, and 1% had no exposure; 30% said they felt incompetent performing nail biopsies.2 In a retrospective study of nail biopsies performed from 2012 to 2017 in the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database, only 0.28% and 1.01% of all general dermatologists and Mohs surgeons, respectively, performed nail biopsies annually.3 A minimally invasive nail surgery technique is essential to alleviating dermatologist and patient apprehension, which may lead to greater adoption and improved outcomes.

Reduce Patient Anxiety During Nail Surgery

The prospect of undergoing nail surgery can be psychologically distressing to patients because the nail unit is highly sensitive, intraoperative and postoperative pain are common concerns, patient education materials generally are scarce and inaccurate,4 and procedures are performed under local anesthesia with the patient fully awake. In a prospective study of 48 patients undergoing nail surgery, the median preoperative Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory level was 42.00 (IQR, 6.50).5 Patient distress may be minimized by providing verbal and written educational materials, discussing expectations, and preoperatively using fast-acting benzodiazepines when necessary.6 Utilizing a sleep mask,7 stress ball,8 music,9 and/or virtual reality10 also may reduce patient anxiety during nail surgery.

Use Proper Anesthetic Techniques

Proper anesthetic technique is crucial to achieve the optimal patient experience during nail surgery. With a wing block, the anesthetic is injected into 3 points: (1) the proximal nail fold, (2) the medial/lateral fold, and (3) the hyponychium. The wing block is the preferred technique by many nail surgeons because the second and third injections are given in skin that is already anesthetized, reducing patient discomfort to a single pinprick11; additionally, there is lower postoperative paresthesia risk with the wing block compared with other digital nerve blocks.12 Ropivacaine, a fast-acting and long-acting anesthetic, is preferred over lidocaine to minimize immediate postoperative pain. Buffering the anesthetic solution to physiologic pH and slow infiltration can reduce pain during infiltration.12 Distraction12 provided by ethyl chloride refrigerant spray, an air-cooling device,13 or vibration also can reduce pain during anesthesia.

Punch Biopsy and Excision Tips

The punch biopsy is a minimally invasive method for diagnosing various neoplastic and inflammatory nail unit conditions, except for pigmented lesions.12 For polydactylous nail conditions requiring biopsy, a digit on the nondominant hand should be selected if possible. The punch is applied directly to the nail plate and twisted with downward pressure until the bone is reached, with the instrument withdrawn slowly to prevent surrounding nail plate detachment. Hemostasis is easily achieved with direct pressure and/or use of epinephrine or ropivacaine during anesthesia, and a digital tourniquet generally is not required. Applying microporous polysaccharide hemospheres powder14 or kaolin-impregnated gauze15 with direct pressure is helpful in managing continued bleeding following nail surgery. Punching through the proximal nail matrix should be avoided to prevent permanent onychodystrophy.

A tangential matrix shave biopsy requires a more practiced technique and is preferred for sampling longitudinal melanonychia. A partial proximal nail plate avulsion adequately exposes the origin of pigment and avoids complete avulsion, which may cause more onychodystrophy.16 For broad erythronychia, a total nail avulsion may be necessary. For narrow, well-defined erythronychia, a less-invasive approach such as trap-door avulsion, longitudinal nail strip, or lateral nail plate curl, depending on the etiology, often is sufficient. Tissue excision should be tailored to the specific etiology, with localized excision sufficient for glomus tumors; onychopapillomas require tangential excision of the distal matrix, entire nail bed, and hyperkeratotic papule at the hyponychium. Pushing the cuticle with an elevator/spatula instead of making 2 tangential incisions on the proximal nail fold has been suggested to decrease postoperative paronychia risk.12 A Teflon-coated blade is used to achieve a smooth cut with minimal drag, enabling collection of specimens less than 1 mm thick, which provides sufficient nail matrix epithelium and dermis for histologic examination.16 After obtaining the specimen, the avulsed nail plate may be sutured back to the nail bed using a rapidly absorbable suture such as polyglactin 910, serving as a temporary biological dressing and splint for the nail unit during healing.12 In a retrospective study of 30 patients with longitudinal melanonychia undergoing tangential matrix excision, 27% (8/30) developed postoperative onychodystrophy.17 Although this technique carries relatively lower risk of permanent onychodystrophy compared to other methods, it still is important to acknowledge during the preoperative consent process.12

The lateral longitudinal excision is a valuable technique for diagnosing nail unit inflammatory conditions. Classically, a longitudinal sample including the proximal nail fold, complete matrix, lateral plate, lateral nail fold, hyponychium, and distal tip skin is obtained, with a 10% narrowing of the nail plate expected. If the lateral horn of the nail matrix is missed, permanent lateral malalignment and spicule formation are potential risks. To minimize narrowing of the nail plate and postoperative paronychia, a longitudinal nail strip—where the proximal nail fold and matrix are left intact—is an alternative technique.18

Pain Management Approaches

Appropriate postoperative pain management is crucial for optimizing patient outcomes. In a prospective study of 20 patients undergoing nail biopsy, the mean pain score 6 to 12 hours postprocedure was 5.7 on a scale of 0 to 10. Patients with presurgery pain vs those without experienced significantly higher pain levels both during anesthesia and after surgery (both P<.05).19 Therefore, a personalized approach to pain management based on presence of presurgical pain is warranted. In a randomized clinical trial of 16 patients anesthetized with lidocaine 2% and intraoperative infiltration with a combination of ropivacaine 0.5 mL and triamcinolone (10 mg/mL [0.5 mL]) vs lidocaine 2% alone, the intraoperative mixture reduced postoperative pain (mean pain score, 2 of 10 at 48 hours postprocedure vs 7.88 of 10 in the control group [P<.001]).20

A Cochrane review of 4 unpublished dental and orthopedic surgery studies showed that gabapentin is superior to placebo in the treatment of acute postoperative pain. Therefore, a single dose of gabapentin (250 mg) may be considered in patients at risk for high postoperative pain.21 In a randomized double-blind trial of 210 Mohs micrographic surgery patients, those receiving acetaminophen and ibuprofen reported lower pain scores at 2, 4, 8, and 12 hours postprocedure compared with patients taking acetaminophen and codeine or acetaminophen alone.22 However, the role of opioids in pain management following nail surgery has not been adequately studied.

Wound Care

An efficient dressing protects the surgical wound, facilitates healing, and provides comfort. In our experience, an initial layer of petrolatum-impregnated gauze followed by a pressure-padded bandage consisting of folded dry gauze secured in place with longitudinally applied tape to avoid a tourniquet effect is effective for nail surgical wounds. As the last step, self-adherent elastic wrap is applied around the digit and extended proximally to prevent a tourniquet effect.23

Final Thoughts

Due to the intricate anatomy of the nail unit, nail surgeries are inherently more invasive than most dermatologic surgical procedures. It is crucial to adopt a minimally invasive approach to reduce tissue damage and potential complications in both the short-term and long-term. Adopting this approach may substantially improve patient outcomes and enhance diagnostic and treatment efficacy.

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Nail surgery myths and truths. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:230-234.

- Lee EH, Nehal KS, Dusza SW, et al. Procedural dermatology training during dermatology residency: a survey of third-year dermatology residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:475-483.E4835. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.05.044

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of nail biopsies performed using the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database 2012 to 2017. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14928. doi:10.1111/dth.14928

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Evaluating the impact and educational value of YouTube videos on nail biopsy procedures. Cutis. 2020;105:148-149, E1.

- Göktay F, Altan ZM, Talas A, et al. Anxiety among patients undergoing nail surgery and skin punch biopsy: effects of age, gender, educational status, and previous experience. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:35-39. doi:10.1177/1203475415588645

- Lipner SR. Pain-minimizing strategies for nail surgery. Cutis. 2018;101:76-77.

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilizing a sleep mask to reduce patient anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2021;108:36. doi:10.12788/cutis.0285

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilization of a stress ball to diminish anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2020;105:294.

- Vachiramon V, Sobanko JF, Rattanaumpawan P, et al. Music reduces patient anxiety during Mohs surgery: an open-label randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:298-305. doi:10.1111/dsu.12047

- Higgins S, Feinstein S, Hawkins M, et al. Virtual reality to improve the experience of the Mohs patient—a prospective interventional study. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1009-1018. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001854

- Jellinek NJ, Vélez NF. Nail surgery: best way to obtain effective anesthesia. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:265-271. doi:10.1016/j.det.2014.12.007

- Baltz JO, Jellinek NJ. Nail surgery: six essential techniques. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:305-318. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.12.015

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Air cooling for improved analgesia during local anesthetic infiltration for nail surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:E231-E232. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.11.032

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Microporous polysaccharide hemospheres powder for hemostasis following nail surgery [published online March 26, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.069

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Kaolin-impregnated gauze for hemostasis following nail surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:E13-E14. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.008

- Jellinek N. Nail matrix biopsy of longitudinal melanonychia: diagnostic algorithm including the matrix shave biopsy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:803-810. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.001

- Richert B, Theunis A, Norrenberg S, et al. Tangential excision of pigmented nail matrix lesions responsible for longitudinal melanonychia: evaluation of the technique on a series of 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:96-104. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.01.029

- Godse R, Jariwala N, Rubin AI. How we do it: the longitudinal nail strip biopsy for nail unit inflammatory dermatoses. Dermatol Surg. 2023;49:311-313. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003707

- Ricardo JW, Qiu Y, Lipner SR. Longitudinal perioperative pain assessment in nail surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:874-876. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.11.042

- Di Chiacchio N, Ocampo-Garza J, Villarreal-Villarreal CD, et al. Post-nail procedure analgesia: a randomized control pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:860-862. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.015

- Straube S, Derry S, Moore RA, et al. Single dose oral gabapentin for established acute postoperative pain in adults [published online May 12, 2010]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010:CD008183. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008183.pub2

- Sniezek PJ, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. A randomized controlled trial comparing acetaminophen, acetaminophen and ibuprofen, and acetaminophen and codeine for postoperative pain relief after Mohs surgery and cutaneous reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1007-1013. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02022.x

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. How we do it: pressure-padded dressing with self-adherent elastic wrap for wound care after nail surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:442-444. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002371

Nail surgical procedures including biopsies, correction of onychocryptosis and other deformities, and excision of tumors are essential for diagnosing and treating nail disorders. Nail surgery often is perceived by dermatologists as a difficult-to-perform, high-risk procedure associated with patient anxiety, pain, and permanent scarring, which may limit implementation. Misconceptions about nail surgical techniques, aftercare, and patient outcomes are prevalent, and a paucity of nail surgery randomized clinical trials hinder formulation of standardized guidelines.1 In a survey-based study of 95 dermatology residency programs (240 total respondents), 58% of residents said they performed 10 or fewer nail procedures, 10% performed more than 10 procedures, 25% only observed nail procedures, 4% were exposed by lecture only, and 1% had no exposure; 30% said they felt incompetent performing nail biopsies.2 In a retrospective study of nail biopsies performed from 2012 to 2017 in the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database, only 0.28% and 1.01% of all general dermatologists and Mohs surgeons, respectively, performed nail biopsies annually.3 A minimally invasive nail surgery technique is essential to alleviating dermatologist and patient apprehension, which may lead to greater adoption and improved outcomes.

Reduce Patient Anxiety During Nail Surgery

The prospect of undergoing nail surgery can be psychologically distressing to patients because the nail unit is highly sensitive, intraoperative and postoperative pain are common concerns, patient education materials generally are scarce and inaccurate,4 and procedures are performed under local anesthesia with the patient fully awake. In a prospective study of 48 patients undergoing nail surgery, the median preoperative Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory level was 42.00 (IQR, 6.50).5 Patient distress may be minimized by providing verbal and written educational materials, discussing expectations, and preoperatively using fast-acting benzodiazepines when necessary.6 Utilizing a sleep mask,7 stress ball,8 music,9 and/or virtual reality10 also may reduce patient anxiety during nail surgery.

Use Proper Anesthetic Techniques

Proper anesthetic technique is crucial to achieve the optimal patient experience during nail surgery. With a wing block, the anesthetic is injected into 3 points: (1) the proximal nail fold, (2) the medial/lateral fold, and (3) the hyponychium. The wing block is the preferred technique by many nail surgeons because the second and third injections are given in skin that is already anesthetized, reducing patient discomfort to a single pinprick11; additionally, there is lower postoperative paresthesia risk with the wing block compared with other digital nerve blocks.12 Ropivacaine, a fast-acting and long-acting anesthetic, is preferred over lidocaine to minimize immediate postoperative pain. Buffering the anesthetic solution to physiologic pH and slow infiltration can reduce pain during infiltration.12 Distraction12 provided by ethyl chloride refrigerant spray, an air-cooling device,13 or vibration also can reduce pain during anesthesia.

Punch Biopsy and Excision Tips

The punch biopsy is a minimally invasive method for diagnosing various neoplastic and inflammatory nail unit conditions, except for pigmented lesions.12 For polydactylous nail conditions requiring biopsy, a digit on the nondominant hand should be selected if possible. The punch is applied directly to the nail plate and twisted with downward pressure until the bone is reached, with the instrument withdrawn slowly to prevent surrounding nail plate detachment. Hemostasis is easily achieved with direct pressure and/or use of epinephrine or ropivacaine during anesthesia, and a digital tourniquet generally is not required. Applying microporous polysaccharide hemospheres powder14 or kaolin-impregnated gauze15 with direct pressure is helpful in managing continued bleeding following nail surgery. Punching through the proximal nail matrix should be avoided to prevent permanent onychodystrophy.

A tangential matrix shave biopsy requires a more practiced technique and is preferred for sampling longitudinal melanonychia. A partial proximal nail plate avulsion adequately exposes the origin of pigment and avoids complete avulsion, which may cause more onychodystrophy.16 For broad erythronychia, a total nail avulsion may be necessary. For narrow, well-defined erythronychia, a less-invasive approach such as trap-door avulsion, longitudinal nail strip, or lateral nail plate curl, depending on the etiology, often is sufficient. Tissue excision should be tailored to the specific etiology, with localized excision sufficient for glomus tumors; onychopapillomas require tangential excision of the distal matrix, entire nail bed, and hyperkeratotic papule at the hyponychium. Pushing the cuticle with an elevator/spatula instead of making 2 tangential incisions on the proximal nail fold has been suggested to decrease postoperative paronychia risk.12 A Teflon-coated blade is used to achieve a smooth cut with minimal drag, enabling collection of specimens less than 1 mm thick, which provides sufficient nail matrix epithelium and dermis for histologic examination.16 After obtaining the specimen, the avulsed nail plate may be sutured back to the nail bed using a rapidly absorbable suture such as polyglactin 910, serving as a temporary biological dressing and splint for the nail unit during healing.12 In a retrospective study of 30 patients with longitudinal melanonychia undergoing tangential matrix excision, 27% (8/30) developed postoperative onychodystrophy.17 Although this technique carries relatively lower risk of permanent onychodystrophy compared to other methods, it still is important to acknowledge during the preoperative consent process.12

The lateral longitudinal excision is a valuable technique for diagnosing nail unit inflammatory conditions. Classically, a longitudinal sample including the proximal nail fold, complete matrix, lateral plate, lateral nail fold, hyponychium, and distal tip skin is obtained, with a 10% narrowing of the nail plate expected. If the lateral horn of the nail matrix is missed, permanent lateral malalignment and spicule formation are potential risks. To minimize narrowing of the nail plate and postoperative paronychia, a longitudinal nail strip—where the proximal nail fold and matrix are left intact—is an alternative technique.18

Pain Management Approaches

Appropriate postoperative pain management is crucial for optimizing patient outcomes. In a prospective study of 20 patients undergoing nail biopsy, the mean pain score 6 to 12 hours postprocedure was 5.7 on a scale of 0 to 10. Patients with presurgery pain vs those without experienced significantly higher pain levels both during anesthesia and after surgery (both P<.05).19 Therefore, a personalized approach to pain management based on presence of presurgical pain is warranted. In a randomized clinical trial of 16 patients anesthetized with lidocaine 2% and intraoperative infiltration with a combination of ropivacaine 0.5 mL and triamcinolone (10 mg/mL [0.5 mL]) vs lidocaine 2% alone, the intraoperative mixture reduced postoperative pain (mean pain score, 2 of 10 at 48 hours postprocedure vs 7.88 of 10 in the control group [P<.001]).20

A Cochrane review of 4 unpublished dental and orthopedic surgery studies showed that gabapentin is superior to placebo in the treatment of acute postoperative pain. Therefore, a single dose of gabapentin (250 mg) may be considered in patients at risk for high postoperative pain.21 In a randomized double-blind trial of 210 Mohs micrographic surgery patients, those receiving acetaminophen and ibuprofen reported lower pain scores at 2, 4, 8, and 12 hours postprocedure compared with patients taking acetaminophen and codeine or acetaminophen alone.22 However, the role of opioids in pain management following nail surgery has not been adequately studied.

Wound Care

An efficient dressing protects the surgical wound, facilitates healing, and provides comfort. In our experience, an initial layer of petrolatum-impregnated gauze followed by a pressure-padded bandage consisting of folded dry gauze secured in place with longitudinally applied tape to avoid a tourniquet effect is effective for nail surgical wounds. As the last step, self-adherent elastic wrap is applied around the digit and extended proximally to prevent a tourniquet effect.23

Final Thoughts

Due to the intricate anatomy of the nail unit, nail surgeries are inherently more invasive than most dermatologic surgical procedures. It is crucial to adopt a minimally invasive approach to reduce tissue damage and potential complications in both the short-term and long-term. Adopting this approach may substantially improve patient outcomes and enhance diagnostic and treatment efficacy.

Nail surgical procedures including biopsies, correction of onychocryptosis and other deformities, and excision of tumors are essential for diagnosing and treating nail disorders. Nail surgery often is perceived by dermatologists as a difficult-to-perform, high-risk procedure associated with patient anxiety, pain, and permanent scarring, which may limit implementation. Misconceptions about nail surgical techniques, aftercare, and patient outcomes are prevalent, and a paucity of nail surgery randomized clinical trials hinder formulation of standardized guidelines.1 In a survey-based study of 95 dermatology residency programs (240 total respondents), 58% of residents said they performed 10 or fewer nail procedures, 10% performed more than 10 procedures, 25% only observed nail procedures, 4% were exposed by lecture only, and 1% had no exposure; 30% said they felt incompetent performing nail biopsies.2 In a retrospective study of nail biopsies performed from 2012 to 2017 in the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database, only 0.28% and 1.01% of all general dermatologists and Mohs surgeons, respectively, performed nail biopsies annually.3 A minimally invasive nail surgery technique is essential to alleviating dermatologist and patient apprehension, which may lead to greater adoption and improved outcomes.

Reduce Patient Anxiety During Nail Surgery

The prospect of undergoing nail surgery can be psychologically distressing to patients because the nail unit is highly sensitive, intraoperative and postoperative pain are common concerns, patient education materials generally are scarce and inaccurate,4 and procedures are performed under local anesthesia with the patient fully awake. In a prospective study of 48 patients undergoing nail surgery, the median preoperative Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory level was 42.00 (IQR, 6.50).5 Patient distress may be minimized by providing verbal and written educational materials, discussing expectations, and preoperatively using fast-acting benzodiazepines when necessary.6 Utilizing a sleep mask,7 stress ball,8 music,9 and/or virtual reality10 also may reduce patient anxiety during nail surgery.

Use Proper Anesthetic Techniques

Proper anesthetic technique is crucial to achieve the optimal patient experience during nail surgery. With a wing block, the anesthetic is injected into 3 points: (1) the proximal nail fold, (2) the medial/lateral fold, and (3) the hyponychium. The wing block is the preferred technique by many nail surgeons because the second and third injections are given in skin that is already anesthetized, reducing patient discomfort to a single pinprick11; additionally, there is lower postoperative paresthesia risk with the wing block compared with other digital nerve blocks.12 Ropivacaine, a fast-acting and long-acting anesthetic, is preferred over lidocaine to minimize immediate postoperative pain. Buffering the anesthetic solution to physiologic pH and slow infiltration can reduce pain during infiltration.12 Distraction12 provided by ethyl chloride refrigerant spray, an air-cooling device,13 or vibration also can reduce pain during anesthesia.

Punch Biopsy and Excision Tips

The punch biopsy is a minimally invasive method for diagnosing various neoplastic and inflammatory nail unit conditions, except for pigmented lesions.12 For polydactylous nail conditions requiring biopsy, a digit on the nondominant hand should be selected if possible. The punch is applied directly to the nail plate and twisted with downward pressure until the bone is reached, with the instrument withdrawn slowly to prevent surrounding nail plate detachment. Hemostasis is easily achieved with direct pressure and/or use of epinephrine or ropivacaine during anesthesia, and a digital tourniquet generally is not required. Applying microporous polysaccharide hemospheres powder14 or kaolin-impregnated gauze15 with direct pressure is helpful in managing continued bleeding following nail surgery. Punching through the proximal nail matrix should be avoided to prevent permanent onychodystrophy.

A tangential matrix shave biopsy requires a more practiced technique and is preferred for sampling longitudinal melanonychia. A partial proximal nail plate avulsion adequately exposes the origin of pigment and avoids complete avulsion, which may cause more onychodystrophy.16 For broad erythronychia, a total nail avulsion may be necessary. For narrow, well-defined erythronychia, a less-invasive approach such as trap-door avulsion, longitudinal nail strip, or lateral nail plate curl, depending on the etiology, often is sufficient. Tissue excision should be tailored to the specific etiology, with localized excision sufficient for glomus tumors; onychopapillomas require tangential excision of the distal matrix, entire nail bed, and hyperkeratotic papule at the hyponychium. Pushing the cuticle with an elevator/spatula instead of making 2 tangential incisions on the proximal nail fold has been suggested to decrease postoperative paronychia risk.12 A Teflon-coated blade is used to achieve a smooth cut with minimal drag, enabling collection of specimens less than 1 mm thick, which provides sufficient nail matrix epithelium and dermis for histologic examination.16 After obtaining the specimen, the avulsed nail plate may be sutured back to the nail bed using a rapidly absorbable suture such as polyglactin 910, serving as a temporary biological dressing and splint for the nail unit during healing.12 In a retrospective study of 30 patients with longitudinal melanonychia undergoing tangential matrix excision, 27% (8/30) developed postoperative onychodystrophy.17 Although this technique carries relatively lower risk of permanent onychodystrophy compared to other methods, it still is important to acknowledge during the preoperative consent process.12

The lateral longitudinal excision is a valuable technique for diagnosing nail unit inflammatory conditions. Classically, a longitudinal sample including the proximal nail fold, complete matrix, lateral plate, lateral nail fold, hyponychium, and distal tip skin is obtained, with a 10% narrowing of the nail plate expected. If the lateral horn of the nail matrix is missed, permanent lateral malalignment and spicule formation are potential risks. To minimize narrowing of the nail plate and postoperative paronychia, a longitudinal nail strip—where the proximal nail fold and matrix are left intact—is an alternative technique.18

Pain Management Approaches

Appropriate postoperative pain management is crucial for optimizing patient outcomes. In a prospective study of 20 patients undergoing nail biopsy, the mean pain score 6 to 12 hours postprocedure was 5.7 on a scale of 0 to 10. Patients with presurgery pain vs those without experienced significantly higher pain levels both during anesthesia and after surgery (both P<.05).19 Therefore, a personalized approach to pain management based on presence of presurgical pain is warranted. In a randomized clinical trial of 16 patients anesthetized with lidocaine 2% and intraoperative infiltration with a combination of ropivacaine 0.5 mL and triamcinolone (10 mg/mL [0.5 mL]) vs lidocaine 2% alone, the intraoperative mixture reduced postoperative pain (mean pain score, 2 of 10 at 48 hours postprocedure vs 7.88 of 10 in the control group [P<.001]).20

A Cochrane review of 4 unpublished dental and orthopedic surgery studies showed that gabapentin is superior to placebo in the treatment of acute postoperative pain. Therefore, a single dose of gabapentin (250 mg) may be considered in patients at risk for high postoperative pain.21 In a randomized double-blind trial of 210 Mohs micrographic surgery patients, those receiving acetaminophen and ibuprofen reported lower pain scores at 2, 4, 8, and 12 hours postprocedure compared with patients taking acetaminophen and codeine or acetaminophen alone.22 However, the role of opioids in pain management following nail surgery has not been adequately studied.

Wound Care

An efficient dressing protects the surgical wound, facilitates healing, and provides comfort. In our experience, an initial layer of petrolatum-impregnated gauze followed by a pressure-padded bandage consisting of folded dry gauze secured in place with longitudinally applied tape to avoid a tourniquet effect is effective for nail surgical wounds. As the last step, self-adherent elastic wrap is applied around the digit and extended proximally to prevent a tourniquet effect.23

Final Thoughts

Due to the intricate anatomy of the nail unit, nail surgeries are inherently more invasive than most dermatologic surgical procedures. It is crucial to adopt a minimally invasive approach to reduce tissue damage and potential complications in both the short-term and long-term. Adopting this approach may substantially improve patient outcomes and enhance diagnostic and treatment efficacy.

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Nail surgery myths and truths. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:230-234.

- Lee EH, Nehal KS, Dusza SW, et al. Procedural dermatology training during dermatology residency: a survey of third-year dermatology residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:475-483.E4835. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.05.044

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of nail biopsies performed using the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database 2012 to 2017. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14928. doi:10.1111/dth.14928

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Evaluating the impact and educational value of YouTube videos on nail biopsy procedures. Cutis. 2020;105:148-149, E1.

- Göktay F, Altan ZM, Talas A, et al. Anxiety among patients undergoing nail surgery and skin punch biopsy: effects of age, gender, educational status, and previous experience. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:35-39. doi:10.1177/1203475415588645

- Lipner SR. Pain-minimizing strategies for nail surgery. Cutis. 2018;101:76-77.

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilizing a sleep mask to reduce patient anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2021;108:36. doi:10.12788/cutis.0285

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilization of a stress ball to diminish anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2020;105:294.

- Vachiramon V, Sobanko JF, Rattanaumpawan P, et al. Music reduces patient anxiety during Mohs surgery: an open-label randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:298-305. doi:10.1111/dsu.12047

- Higgins S, Feinstein S, Hawkins M, et al. Virtual reality to improve the experience of the Mohs patient—a prospective interventional study. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1009-1018. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001854

- Jellinek NJ, Vélez NF. Nail surgery: best way to obtain effective anesthesia. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:265-271. doi:10.1016/j.det.2014.12.007

- Baltz JO, Jellinek NJ. Nail surgery: six essential techniques. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:305-318. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.12.015

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Air cooling for improved analgesia during local anesthetic infiltration for nail surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:E231-E232. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.11.032

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Microporous polysaccharide hemospheres powder for hemostasis following nail surgery [published online March 26, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.069

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Kaolin-impregnated gauze for hemostasis following nail surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:E13-E14. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.008

- Jellinek N. Nail matrix biopsy of longitudinal melanonychia: diagnostic algorithm including the matrix shave biopsy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:803-810. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.001

- Richert B, Theunis A, Norrenberg S, et al. Tangential excision of pigmented nail matrix lesions responsible for longitudinal melanonychia: evaluation of the technique on a series of 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:96-104. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.01.029

- Godse R, Jariwala N, Rubin AI. How we do it: the longitudinal nail strip biopsy for nail unit inflammatory dermatoses. Dermatol Surg. 2023;49:311-313. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003707

- Ricardo JW, Qiu Y, Lipner SR. Longitudinal perioperative pain assessment in nail surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:874-876. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.11.042

- Di Chiacchio N, Ocampo-Garza J, Villarreal-Villarreal CD, et al. Post-nail procedure analgesia: a randomized control pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:860-862. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.015

- Straube S, Derry S, Moore RA, et al. Single dose oral gabapentin for established acute postoperative pain in adults [published online May 12, 2010]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010:CD008183. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008183.pub2

- Sniezek PJ, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. A randomized controlled trial comparing acetaminophen, acetaminophen and ibuprofen, and acetaminophen and codeine for postoperative pain relief after Mohs surgery and cutaneous reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1007-1013. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02022.x

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. How we do it: pressure-padded dressing with self-adherent elastic wrap for wound care after nail surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:442-444. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002371

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Nail surgery myths and truths. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:230-234.

- Lee EH, Nehal KS, Dusza SW, et al. Procedural dermatology training during dermatology residency: a survey of third-year dermatology residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:475-483.E4835. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.05.044

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of nail biopsies performed using the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database 2012 to 2017. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14928. doi:10.1111/dth.14928

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Evaluating the impact and educational value of YouTube videos on nail biopsy procedures. Cutis. 2020;105:148-149, E1.

- Göktay F, Altan ZM, Talas A, et al. Anxiety among patients undergoing nail surgery and skin punch biopsy: effects of age, gender, educational status, and previous experience. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:35-39. doi:10.1177/1203475415588645

- Lipner SR. Pain-minimizing strategies for nail surgery. Cutis. 2018;101:76-77.

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilizing a sleep mask to reduce patient anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2021;108:36. doi:10.12788/cutis.0285

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Utilization of a stress ball to diminish anxiety during nail surgery. Cutis. 2020;105:294.

- Vachiramon V, Sobanko JF, Rattanaumpawan P, et al. Music reduces patient anxiety during Mohs surgery: an open-label randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:298-305. doi:10.1111/dsu.12047

- Higgins S, Feinstein S, Hawkins M, et al. Virtual reality to improve the experience of the Mohs patient—a prospective interventional study. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1009-1018. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001854

- Jellinek NJ, Vélez NF. Nail surgery: best way to obtain effective anesthesia. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:265-271. doi:10.1016/j.det.2014.12.007

- Baltz JO, Jellinek NJ. Nail surgery: six essential techniques. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:305-318. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.12.015

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Air cooling for improved analgesia during local anesthetic infiltration for nail surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:E231-E232. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.11.032

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Microporous polysaccharide hemospheres powder for hemostasis following nail surgery [published online March 26, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.069

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. Kaolin-impregnated gauze for hemostasis following nail surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:E13-E14. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.008

- Jellinek N. Nail matrix biopsy of longitudinal melanonychia: diagnostic algorithm including the matrix shave biopsy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:803-810. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.001

- Richert B, Theunis A, Norrenberg S, et al. Tangential excision of pigmented nail matrix lesions responsible for longitudinal melanonychia: evaluation of the technique on a series of 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:96-104. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.01.029

- Godse R, Jariwala N, Rubin AI. How we do it: the longitudinal nail strip biopsy for nail unit inflammatory dermatoses. Dermatol Surg. 2023;49:311-313. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003707

- Ricardo JW, Qiu Y, Lipner SR. Longitudinal perioperative pain assessment in nail surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:874-876. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.11.042

- Di Chiacchio N, Ocampo-Garza J, Villarreal-Villarreal CD, et al. Post-nail procedure analgesia: a randomized control pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:860-862. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.015

- Straube S, Derry S, Moore RA, et al. Single dose oral gabapentin for established acute postoperative pain in adults [published online May 12, 2010]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010:CD008183. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008183.pub2

- Sniezek PJ, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. A randomized controlled trial comparing acetaminophen, acetaminophen and ibuprofen, and acetaminophen and codeine for postoperative pain relief after Mohs surgery and cutaneous reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1007-1013. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02022.x

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. How we do it: pressure-padded dressing with self-adherent elastic wrap for wound care after nail surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:442-444. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002371

Dermatology Author Gender Trends During the COVID-19 Pandemic

To the Editor:

Peer-reviewed publications are important determinants for promotions, academic leadership, and grants in dermatology.1 The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on dermatology research productivity remains an area of investigation. We sought to determine authorship trends for males and females during the pandemic.

A cross-sectional retrospective study of the top 20 dermatology journals—determined by impact factor and Google Scholar H5-index—was conducted to identify manuscripts with submission date specified prepandemic (May 1, 2019–October 31, 2019) and during the pandemic (May 1, 2020–October 31, 2020). Submission date, first/last author name, sex, and affiliated country were extracted. Single authors were designated as first authors. Gender API (https://gender-api.com/en/) classified gender. A χ2 test (P<.05) compared differences in proportions of female first/last authors from 2019 to 2020.

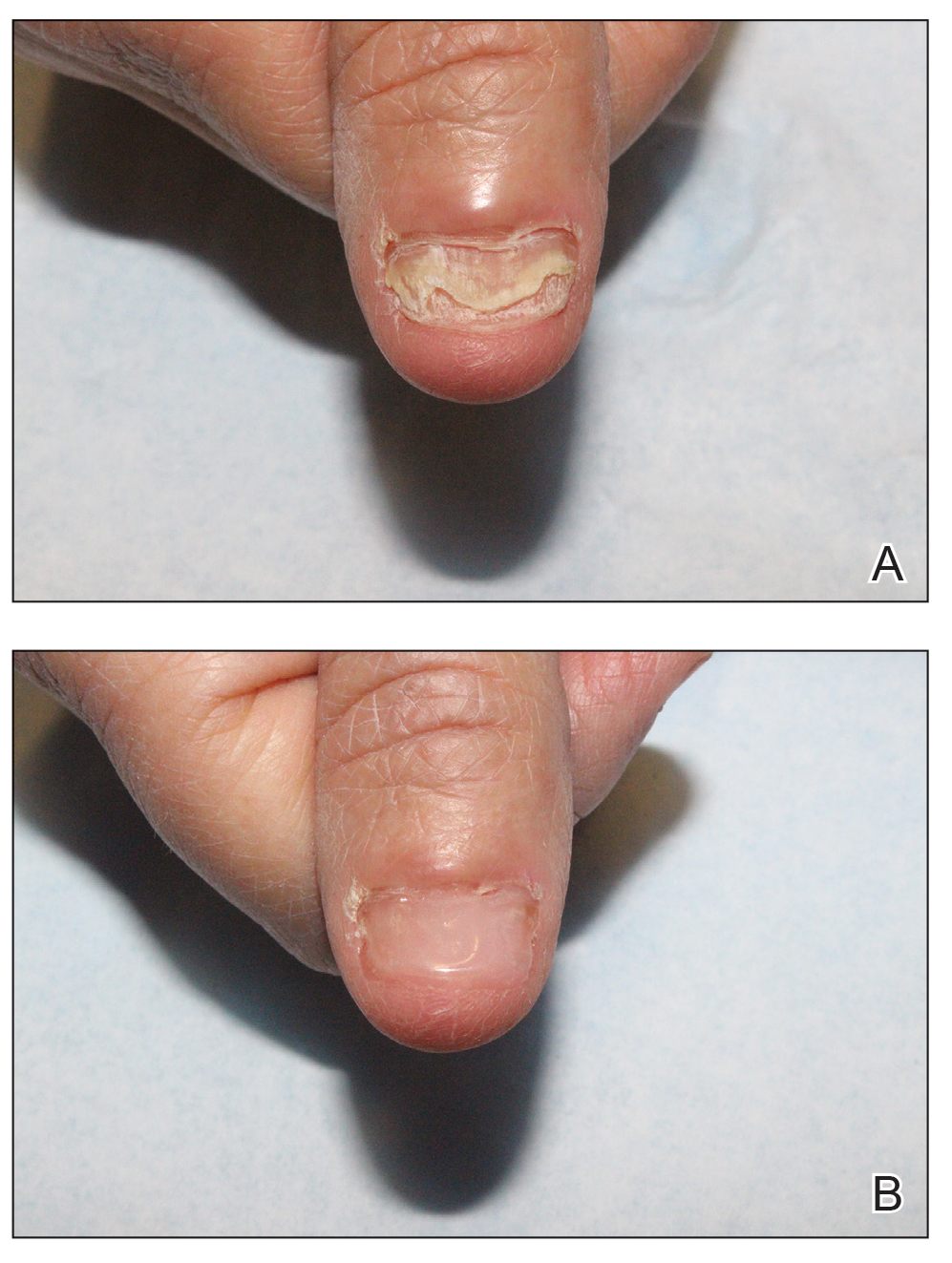

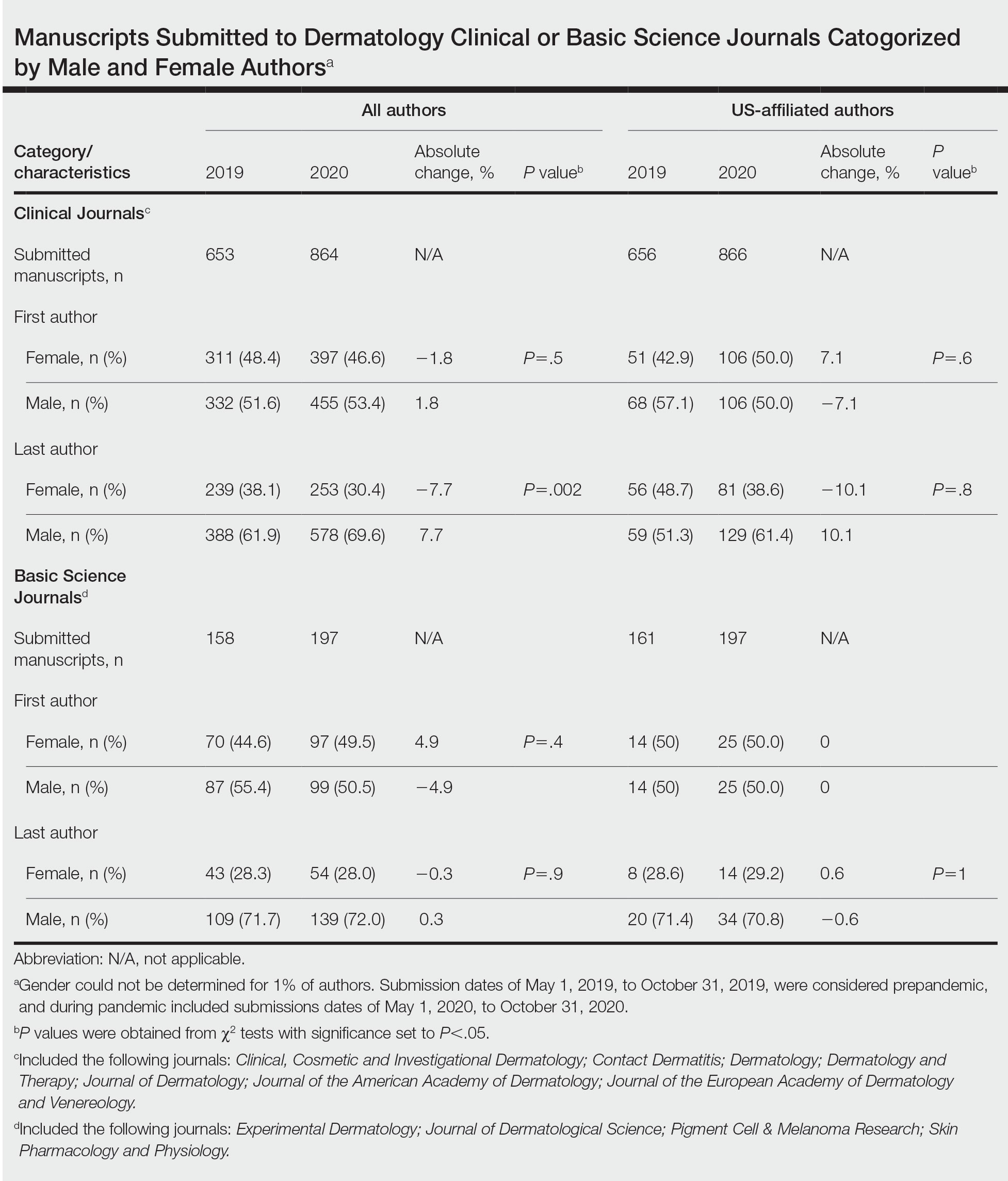

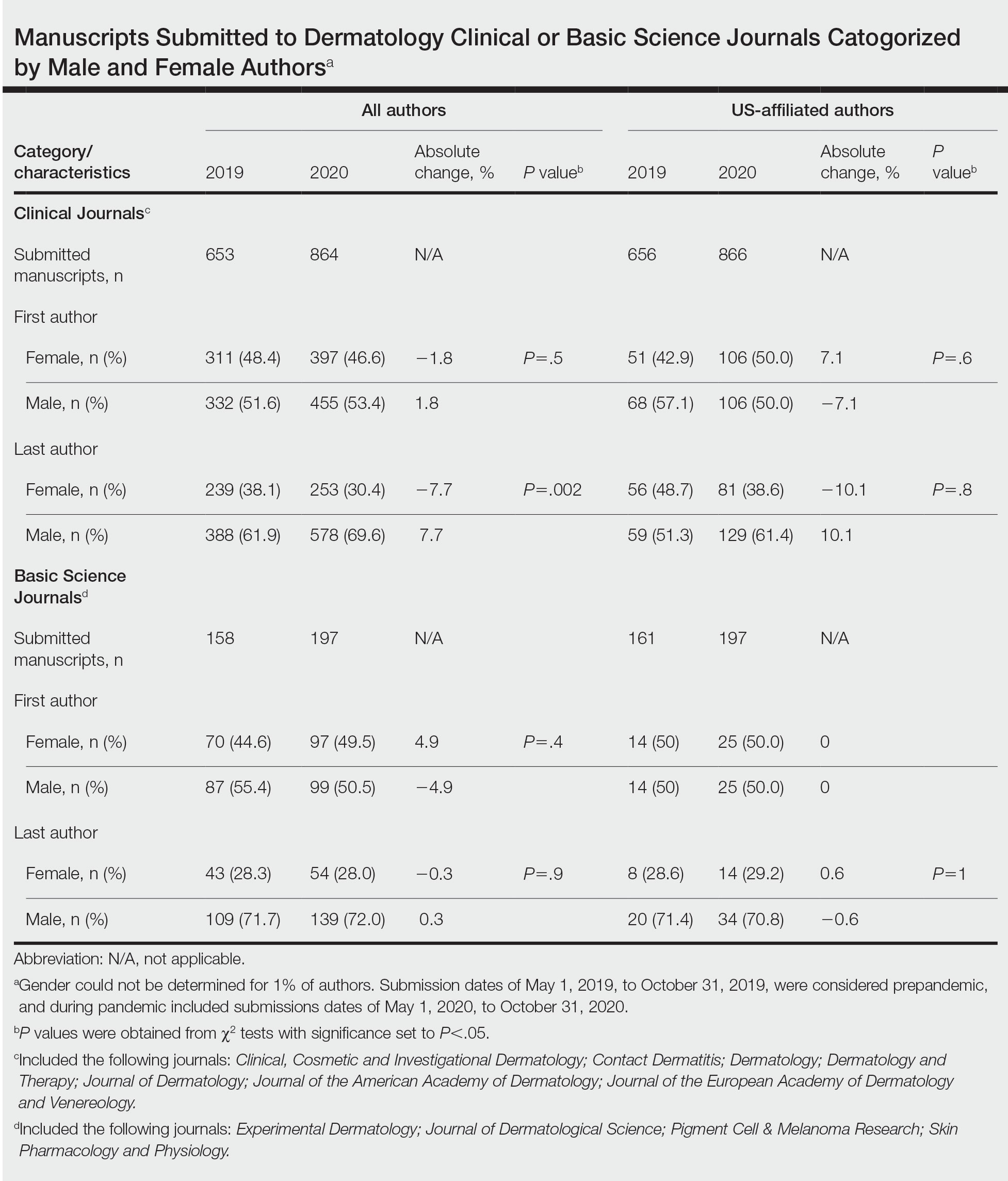

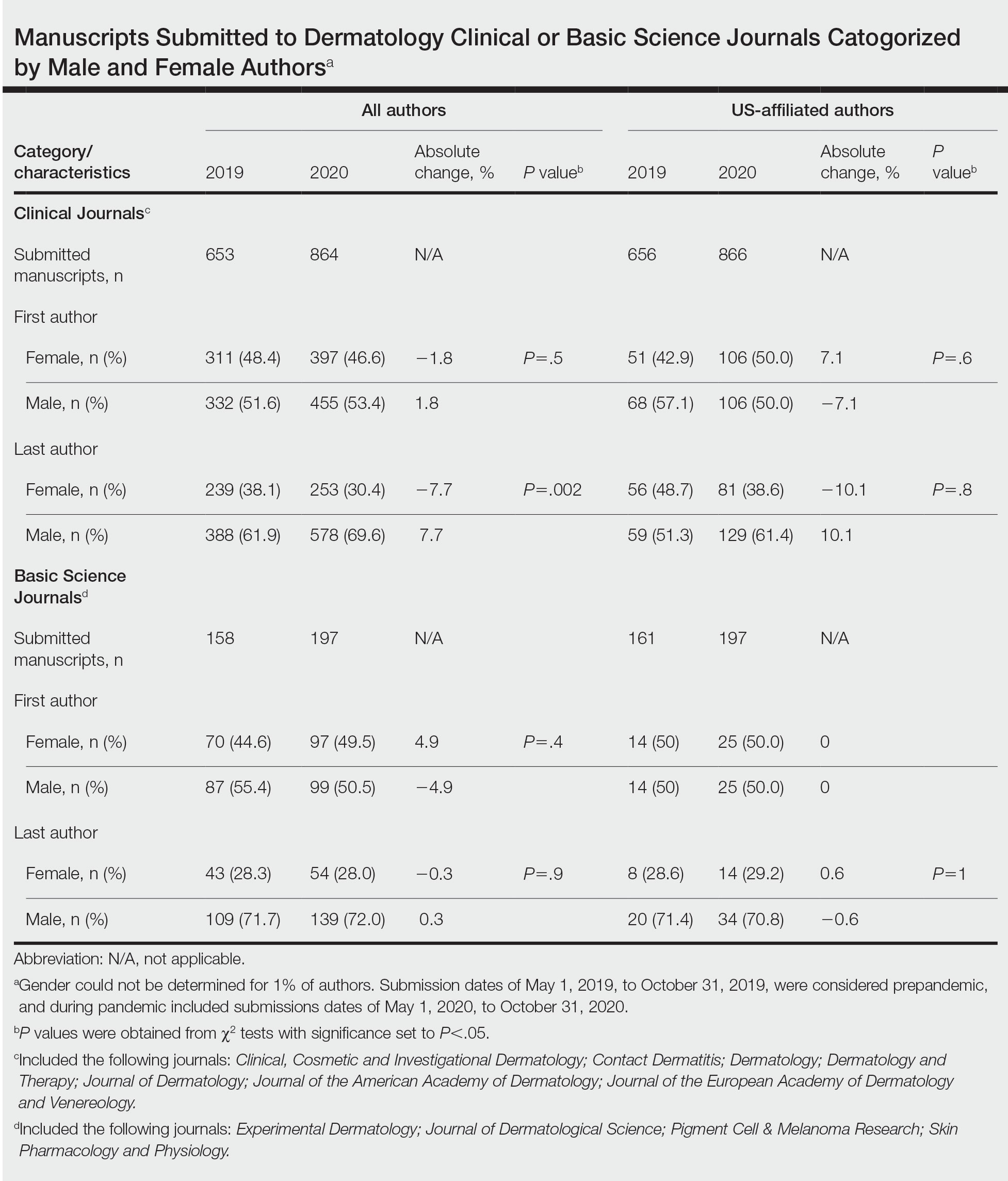

Overall, 811 and 1061 articles submitted in 2019 and 2020, respectively, were included. There were 1517 articles submitted to clinical journals and 355 articles submitted to basic science journals (Table). For the 7 clinical journals included, there was a 7.7% decrease in the proportion of female last authors in 2020 vs 2019 (P=.002), with the largest decrease between August and September 2020. Although other comparisons did not yield statistically significant differences (P>.05 all)(Table), several trends were observed. For clinical journals, there was a 1.8% decrease in the proportion of female first authors. For the 4 basic science journals included, there was a 4.9% increase and a 0.3% decrease in percentages of female first and last authors, respectively, for 2020 vs 2019.

Our findings indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic may have impacted female authors’ productivity in clinical dermatology publications. In a survey-based study for 2010 to 2011, female physician-researchers (n=437) spent 8.5 more hours per week on domestic activities and childcare and were more likely to take time off for childcare if their partner worked full time compared with males (n=612)(42.6% vs 12.4%, respectively).2 Our observation that female last authors had a significant decrease in publications may suggest that this population had a disproportionate burden of domestic labor and childcare during the pandemic. It is possible that last authors, who generally are more senior researchers, may be more likely to have childcare, eldercare, and other types of domestic responsibilities. Similarly, in a study of surgery submissions (n=1068), there were 6%, 7%, and 4% decreases in percentages of female last, corresponding, and first authors, respectively, from 2019 to 2020.3Our study had limitations. Only 11 journals were analyzed because others did not have specified submission dates. Some journals only provided submission information for a subset of articles (eg, those published in the In Press section), which may have accounted for the large discrepancy in submission numbers for 2019 to 2020. Gender could not be determined for 1% of authors and was limited to female and male. Although our study submission time frame (May–October 2020) aimed at identifying research conducted during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, some of these studies may have been conducted months or years before the pandemic. Future studies should focus on longer and more comprehensive time frames. Finally, estimated dates of stay-at-home orders fail to consider differences within countries.

The proportion of female US-affiliated first and last authors publishing in dermatology journals increased from 12% to 48% in 1976 and from 6% to 31% in 2006,4 which is encouraging. However, a gender gap persists, with one-third of National Institutes of Health grants in dermatology and one-fourth of research project grants in dermatology awarded to women.5 Consequences of the pandemic on academic productivity may include fewer women represented in higher academic ranks, lower compensation, and lower career satisfaction compared with men.1 We urge academic institutions and funding agencies to recognize and take action to mitigate long-term sequelae. Extended grant end dates and submission periods, funding opportunities dedicated to women, and prioritization of female-authored submissions are some strategies that can safeguard equitable career progression in dermatology research.

- Stewart C, Lipner SR. Gender and race trends in academic rank of dermatologists at top U.S. institutions: a cross-sectional study. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:283-285. doi:10.1016/j .ijwd.2020.04.010

- Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, et al. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by highachieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med. 2014; 160:344-353. doi:10.7326/M13-0974

- Kibbe MR. Consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on manuscript submissions by women. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:803-804. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2020.3917

- Feramisco JD, Leitenberger JJ, Redfern SI, et al. A gender gap in the dermatology literature? cross-sectional analysis of manuscript authorship trends in dermatology journals during 3 decades. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;6:63-69. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.044

- Cheng MY, Sukhov A, Sultani H, et al. Trends in national institutes of health funding of principal investigators in dermatology research by academic degree and sex. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:883-888. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.0271

To the Editor:

Peer-reviewed publications are important determinants for promotions, academic leadership, and grants in dermatology.1 The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on dermatology research productivity remains an area of investigation. We sought to determine authorship trends for males and females during the pandemic.

A cross-sectional retrospective study of the top 20 dermatology journals—determined by impact factor and Google Scholar H5-index—was conducted to identify manuscripts with submission date specified prepandemic (May 1, 2019–October 31, 2019) and during the pandemic (May 1, 2020–October 31, 2020). Submission date, first/last author name, sex, and affiliated country were extracted. Single authors were designated as first authors. Gender API (https://gender-api.com/en/) classified gender. A χ2 test (P<.05) compared differences in proportions of female first/last authors from 2019 to 2020.

Overall, 811 and 1061 articles submitted in 2019 and 2020, respectively, were included. There were 1517 articles submitted to clinical journals and 355 articles submitted to basic science journals (Table). For the 7 clinical journals included, there was a 7.7% decrease in the proportion of female last authors in 2020 vs 2019 (P=.002), with the largest decrease between August and September 2020. Although other comparisons did not yield statistically significant differences (P>.05 all)(Table), several trends were observed. For clinical journals, there was a 1.8% decrease in the proportion of female first authors. For the 4 basic science journals included, there was a 4.9% increase and a 0.3% decrease in percentages of female first and last authors, respectively, for 2020 vs 2019.

Our findings indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic may have impacted female authors’ productivity in clinical dermatology publications. In a survey-based study for 2010 to 2011, female physician-researchers (n=437) spent 8.5 more hours per week on domestic activities and childcare and were more likely to take time off for childcare if their partner worked full time compared with males (n=612)(42.6% vs 12.4%, respectively).2 Our observation that female last authors had a significant decrease in publications may suggest that this population had a disproportionate burden of domestic labor and childcare during the pandemic. It is possible that last authors, who generally are more senior researchers, may be more likely to have childcare, eldercare, and other types of domestic responsibilities. Similarly, in a study of surgery submissions (n=1068), there were 6%, 7%, and 4% decreases in percentages of female last, corresponding, and first authors, respectively, from 2019 to 2020.3Our study had limitations. Only 11 journals were analyzed because others did not have specified submission dates. Some journals only provided submission information for a subset of articles (eg, those published in the In Press section), which may have accounted for the large discrepancy in submission numbers for 2019 to 2020. Gender could not be determined for 1% of authors and was limited to female and male. Although our study submission time frame (May–October 2020) aimed at identifying research conducted during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, some of these studies may have been conducted months or years before the pandemic. Future studies should focus on longer and more comprehensive time frames. Finally, estimated dates of stay-at-home orders fail to consider differences within countries.

The proportion of female US-affiliated first and last authors publishing in dermatology journals increased from 12% to 48% in 1976 and from 6% to 31% in 2006,4 which is encouraging. However, a gender gap persists, with one-third of National Institutes of Health grants in dermatology and one-fourth of research project grants in dermatology awarded to women.5 Consequences of the pandemic on academic productivity may include fewer women represented in higher academic ranks, lower compensation, and lower career satisfaction compared with men.1 We urge academic institutions and funding agencies to recognize and take action to mitigate long-term sequelae. Extended grant end dates and submission periods, funding opportunities dedicated to women, and prioritization of female-authored submissions are some strategies that can safeguard equitable career progression in dermatology research.

To the Editor:

Peer-reviewed publications are important determinants for promotions, academic leadership, and grants in dermatology.1 The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on dermatology research productivity remains an area of investigation. We sought to determine authorship trends for males and females during the pandemic.

A cross-sectional retrospective study of the top 20 dermatology journals—determined by impact factor and Google Scholar H5-index—was conducted to identify manuscripts with submission date specified prepandemic (May 1, 2019–October 31, 2019) and during the pandemic (May 1, 2020–October 31, 2020). Submission date, first/last author name, sex, and affiliated country were extracted. Single authors were designated as first authors. Gender API (https://gender-api.com/en/) classified gender. A χ2 test (P<.05) compared differences in proportions of female first/last authors from 2019 to 2020.

Overall, 811 and 1061 articles submitted in 2019 and 2020, respectively, were included. There were 1517 articles submitted to clinical journals and 355 articles submitted to basic science journals (Table). For the 7 clinical journals included, there was a 7.7% decrease in the proportion of female last authors in 2020 vs 2019 (P=.002), with the largest decrease between August and September 2020. Although other comparisons did not yield statistically significant differences (P>.05 all)(Table), several trends were observed. For clinical journals, there was a 1.8% decrease in the proportion of female first authors. For the 4 basic science journals included, there was a 4.9% increase and a 0.3% decrease in percentages of female first and last authors, respectively, for 2020 vs 2019.

Our findings indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic may have impacted female authors’ productivity in clinical dermatology publications. In a survey-based study for 2010 to 2011, female physician-researchers (n=437) spent 8.5 more hours per week on domestic activities and childcare and were more likely to take time off for childcare if their partner worked full time compared with males (n=612)(42.6% vs 12.4%, respectively).2 Our observation that female last authors had a significant decrease in publications may suggest that this population had a disproportionate burden of domestic labor and childcare during the pandemic. It is possible that last authors, who generally are more senior researchers, may be more likely to have childcare, eldercare, and other types of domestic responsibilities. Similarly, in a study of surgery submissions (n=1068), there were 6%, 7%, and 4% decreases in percentages of female last, corresponding, and first authors, respectively, from 2019 to 2020.3Our study had limitations. Only 11 journals were analyzed because others did not have specified submission dates. Some journals only provided submission information for a subset of articles (eg, those published in the In Press section), which may have accounted for the large discrepancy in submission numbers for 2019 to 2020. Gender could not be determined for 1% of authors and was limited to female and male. Although our study submission time frame (May–October 2020) aimed at identifying research conducted during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, some of these studies may have been conducted months or years before the pandemic. Future studies should focus on longer and more comprehensive time frames. Finally, estimated dates of stay-at-home orders fail to consider differences within countries.

The proportion of female US-affiliated first and last authors publishing in dermatology journals increased from 12% to 48% in 1976 and from 6% to 31% in 2006,4 which is encouraging. However, a gender gap persists, with one-third of National Institutes of Health grants in dermatology and one-fourth of research project grants in dermatology awarded to women.5 Consequences of the pandemic on academic productivity may include fewer women represented in higher academic ranks, lower compensation, and lower career satisfaction compared with men.1 We urge academic institutions and funding agencies to recognize and take action to mitigate long-term sequelae. Extended grant end dates and submission periods, funding opportunities dedicated to women, and prioritization of female-authored submissions are some strategies that can safeguard equitable career progression in dermatology research.

- Stewart C, Lipner SR. Gender and race trends in academic rank of dermatologists at top U.S. institutions: a cross-sectional study. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:283-285. doi:10.1016/j .ijwd.2020.04.010

- Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, et al. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by highachieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med. 2014; 160:344-353. doi:10.7326/M13-0974

- Kibbe MR. Consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on manuscript submissions by women. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:803-804. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2020.3917

- Feramisco JD, Leitenberger JJ, Redfern SI, et al. A gender gap in the dermatology literature? cross-sectional analysis of manuscript authorship trends in dermatology journals during 3 decades. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;6:63-69. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.044

- Cheng MY, Sukhov A, Sultani H, et al. Trends in national institutes of health funding of principal investigators in dermatology research by academic degree and sex. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:883-888. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.0271

- Stewart C, Lipner SR. Gender and race trends in academic rank of dermatologists at top U.S. institutions: a cross-sectional study. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:283-285. doi:10.1016/j .ijwd.2020.04.010

- Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, et al. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by highachieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med. 2014; 160:344-353. doi:10.7326/M13-0974

- Kibbe MR. Consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on manuscript submissions by women. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:803-804. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2020.3917

- Feramisco JD, Leitenberger JJ, Redfern SI, et al. A gender gap in the dermatology literature? cross-sectional analysis of manuscript authorship trends in dermatology journals during 3 decades. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;6:63-69. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.044

- Cheng MY, Sukhov A, Sultani H, et al. Trends in national institutes of health funding of principal investigators in dermatology research by academic degree and sex. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:883-888. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.0271

Practice Points

- The academic productivity of female dermatologists as last authors in dermatology clinical journals has potentially been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

- To potentially aid in the resurgence of female dermatologist authors impacted by the pandemic, academic institutions and funding agencies may consider implementing strategies such as extending grant end dates, providing dedicated funding opportunities, and prioritizing female-authored submissions in dermatology research.

Utilizing a Sleep Mask to Reduce Patient Anxiety During Nail Surgery

Practice Gap

Perioperative anxiety is common in patients undergoing nail surgery. Patients might worry about seeing blood; about the procedure itself, including nail avulsion; and about associated pain and disfigurement. Nail surgery causes a high level of anxiety that correlates positively with postoperative pain1 and overall patient dissatisfaction. Furthermore, surgery-related anxiety is a predictor of increased postoperative analgesic use2 and delayed recovery.3

Therefore, implementing strategies that reduce perioperative anxiety may help minimize postoperative pain. Squeezing a stress ball, hand-holding, virtual reality, and music are tools that have been studied to reduce anxiety in the context of Mohs micrographic surgery; these strategies have not been studied for nail surgery.

The Technique

Using a sleep mask is a practical solution to reduce patient anxiety during nail surgery. A minority of patients will choose to watch their surgical procedure; most become unnerved observing their nail surgery. Using a sleep mask diverts visual attention from the surgical field without physically interfering with the nail surgeon. Utilizing a sleep mask is cost-effective, with disposable sleep masks available online for less than $0.30 each. Patients can bring their own mask, or a mask can be offered prior to surgery.

If desired, patients are instructed to wear the sleep mask during the entirety of the procedure, starting from anesthetic infiltration until wound closure and dressing application. Any adjustments can be made with the patient’s free hand. The sleep mask can be offered to patients of all ages undergoing nail surgery under local anesthesia, except babies and young children, who require general anesthesia.

Practical Implications

Distraction is an important strategy to reduce anxiety and pain in patients undergoing surgical procedures. In an observational study of 3087 surgical patients, 36% reported that self-distraction was the most helpful strategy for coping with preoperative anxiety.4 In a randomized, open-label clinical trial of 72 patients undergoing peripheral venous catheterization, asking the patients simple questions during the procedure was more effective than local anesthesia in reducing the perception of pain.5

It is crucial to implement strategies to reduce anxiety in patients undergoing nail surgery. Using a sleep mask impedes direct visualization of the surgical field, thus distracting the patient’s sight and attention from the procedure. Furthermore, this technique is safe and cost-effective.

Controlled clinical trials are necessary to assess the efficacy of this method in reducing nail surgery–related anxiety in comparison to other techniques.

- Navarro-Gastón D, Munuera-Martínez PV. Prevalence of preoperative anxiety and its relationship with postoperative pain in foot nail surgery: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4481. doi:10.3390/ijerph17124481

- Ip HYV, Abrishami A, Peng PWH, et al. Predictors of postoperative pain and analgesic consumption: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:657-677. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181aae87a

- Mavros MN, Athanasiou S, Gkegkes ID, et al. Do psychological variables affect early surgical recovery? PLoS One. 2011;6:E20306. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020306

- Aust H, Rüsch D, Schuster M, et al. Coping strategies in anxious surgical patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:250. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1492-5

- Balanyuk I, Ledonne G, Provenzano M, et al. Distraction technique for pain reduction in peripheral venous catheterization: randomized, controlled trial. Acta Biomed. 2018;89(suppl 4):55-63. doi:10.23750/abmv89i4-S.7115

Practice Gap

Perioperative anxiety is common in patients undergoing nail surgery. Patients might worry about seeing blood; about the procedure itself, including nail avulsion; and about associated pain and disfigurement. Nail surgery causes a high level of anxiety that correlates positively with postoperative pain1 and overall patient dissatisfaction. Furthermore, surgery-related anxiety is a predictor of increased postoperative analgesic use2 and delayed recovery.3

Therefore, implementing strategies that reduce perioperative anxiety may help minimize postoperative pain. Squeezing a stress ball, hand-holding, virtual reality, and music are tools that have been studied to reduce anxiety in the context of Mohs micrographic surgery; these strategies have not been studied for nail surgery.

The Technique

Using a sleep mask is a practical solution to reduce patient anxiety during nail surgery. A minority of patients will choose to watch their surgical procedure; most become unnerved observing their nail surgery. Using a sleep mask diverts visual attention from the surgical field without physically interfering with the nail surgeon. Utilizing a sleep mask is cost-effective, with disposable sleep masks available online for less than $0.30 each. Patients can bring their own mask, or a mask can be offered prior to surgery.

If desired, patients are instructed to wear the sleep mask during the entirety of the procedure, starting from anesthetic infiltration until wound closure and dressing application. Any adjustments can be made with the patient’s free hand. The sleep mask can be offered to patients of all ages undergoing nail surgery under local anesthesia, except babies and young children, who require general anesthesia.

Practical Implications

Distraction is an important strategy to reduce anxiety and pain in patients undergoing surgical procedures. In an observational study of 3087 surgical patients, 36% reported that self-distraction was the most helpful strategy for coping with preoperative anxiety.4 In a randomized, open-label clinical trial of 72 patients undergoing peripheral venous catheterization, asking the patients simple questions during the procedure was more effective than local anesthesia in reducing the perception of pain.5

It is crucial to implement strategies to reduce anxiety in patients undergoing nail surgery. Using a sleep mask impedes direct visualization of the surgical field, thus distracting the patient’s sight and attention from the procedure. Furthermore, this technique is safe and cost-effective.

Controlled clinical trials are necessary to assess the efficacy of this method in reducing nail surgery–related anxiety in comparison to other techniques.

Practice Gap

Perioperative anxiety is common in patients undergoing nail surgery. Patients might worry about seeing blood; about the procedure itself, including nail avulsion; and about associated pain and disfigurement. Nail surgery causes a high level of anxiety that correlates positively with postoperative pain1 and overall patient dissatisfaction. Furthermore, surgery-related anxiety is a predictor of increased postoperative analgesic use2 and delayed recovery.3

Therefore, implementing strategies that reduce perioperative anxiety may help minimize postoperative pain. Squeezing a stress ball, hand-holding, virtual reality, and music are tools that have been studied to reduce anxiety in the context of Mohs micrographic surgery; these strategies have not been studied for nail surgery.

The Technique

Using a sleep mask is a practical solution to reduce patient anxiety during nail surgery. A minority of patients will choose to watch their surgical procedure; most become unnerved observing their nail surgery. Using a sleep mask diverts visual attention from the surgical field without physically interfering with the nail surgeon. Utilizing a sleep mask is cost-effective, with disposable sleep masks available online for less than $0.30 each. Patients can bring their own mask, or a mask can be offered prior to surgery.

If desired, patients are instructed to wear the sleep mask during the entirety of the procedure, starting from anesthetic infiltration until wound closure and dressing application. Any adjustments can be made with the patient’s free hand. The sleep mask can be offered to patients of all ages undergoing nail surgery under local anesthesia, except babies and young children, who require general anesthesia.

Practical Implications

Distraction is an important strategy to reduce anxiety and pain in patients undergoing surgical procedures. In an observational study of 3087 surgical patients, 36% reported that self-distraction was the most helpful strategy for coping with preoperative anxiety.4 In a randomized, open-label clinical trial of 72 patients undergoing peripheral venous catheterization, asking the patients simple questions during the procedure was more effective than local anesthesia in reducing the perception of pain.5

It is crucial to implement strategies to reduce anxiety in patients undergoing nail surgery. Using a sleep mask impedes direct visualization of the surgical field, thus distracting the patient’s sight and attention from the procedure. Furthermore, this technique is safe and cost-effective.

Controlled clinical trials are necessary to assess the efficacy of this method in reducing nail surgery–related anxiety in comparison to other techniques.

- Navarro-Gastón D, Munuera-Martínez PV. Prevalence of preoperative anxiety and its relationship with postoperative pain in foot nail surgery: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4481. doi:10.3390/ijerph17124481

- Ip HYV, Abrishami A, Peng PWH, et al. Predictors of postoperative pain and analgesic consumption: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:657-677. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181aae87a

- Mavros MN, Athanasiou S, Gkegkes ID, et al. Do psychological variables affect early surgical recovery? PLoS One. 2011;6:E20306. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020306

- Aust H, Rüsch D, Schuster M, et al. Coping strategies in anxious surgical patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:250. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1492-5

- Balanyuk I, Ledonne G, Provenzano M, et al. Distraction technique for pain reduction in peripheral venous catheterization: randomized, controlled trial. Acta Biomed. 2018;89(suppl 4):55-63. doi:10.23750/abmv89i4-S.7115

- Navarro-Gastón D, Munuera-Martínez PV. Prevalence of preoperative anxiety and its relationship with postoperative pain in foot nail surgery: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4481. doi:10.3390/ijerph17124481

- Ip HYV, Abrishami A, Peng PWH, et al. Predictors of postoperative pain and analgesic consumption: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:657-677. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181aae87a

- Mavros MN, Athanasiou S, Gkegkes ID, et al. Do psychological variables affect early surgical recovery? PLoS One. 2011;6:E20306. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020306

- Aust H, Rüsch D, Schuster M, et al. Coping strategies in anxious surgical patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:250. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1492-5