User login

A Dermatology Hospitalist Team’s Response to the Inpatient Consult Flowchart

To the Editor:

We read with interest the Cutis article by Dobkin et al1 (Cutis. 2022;109:218-220) regarding guidelines for inpatient and emergency department dermatology consultations. We agree with the authors that dermatology training is lacking in other medical specialties, which makes it challenging for teams to assess the appropriateness of a dermatology consultation in the inpatient setting. Inpatient dermatology consultation can be utilized in a hospital system to aid in rapid and accurate diagnosis, avoid inappropriate therapies, and decrease length of stay2 and readmission rates3 while providing education to the primary teams. This is precisely why in many instances the availability of inpatient dermatology consultation is so important because nondermatologists often are unable to determine whether a rash is life-threatening, benign, or something in between. From the perspective of dermatology hospitalists, there is room for improvement in the flowchart Dobkin et al1 presented to guide inpatient dermatology consultation.

To have a productive relationship with our internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, psychiatry, and other hospital-based colleagues, we must keep an open mind when a consultation is received. We feel that the flowchart proposed by Dobkin et al1 presents too narrow a viewpoint on the utility of inpatient dermatology. It rests on assertions that other teams will be able to determine the appropriate dermatologic diagnosis without involving a dermatologist, which often is not the case.

We disagree with several recommendations in the flowchart, the first being the assertion that patients who are “hemodynamically unstable due to [a] nondermatologic problem (eg, intubated on pressors, febrile, and hypotensive)” are not appropriate for inpatient dermatology consultation.1 Although dermatologists do not commonly encounter patients with critical illness in the outpatient clinic, dermatology consultation can be extremely helpful and even lifesaving in the inpatient setting. It is unrealistic to expect the primary teams to know whether cutaneous manifestations potentially could be related to the patient’s overall clinical picture. On the contrary, we would encourage the primary team in charge of a hemodynamically unstable patient to consult dermatology at the first sign of an unexplained rash. Take for example an acutely ill patient who develops retiform purpura. There are well-established dermatology guidelines for the workup of retiform purpura,4 including prompt biopsy and assessment of broad, potentially life-threatening differential diagnoses from calciphylaxis to angioinvasive fungal infection. In this scenario, the dermatology consultant may render the correct diagnosis and recommend immediate treatment that could be lifesaving.

Secondly, we do not agree with the recommendation that a patient in hospice care is not appropriate for inpatient dermatology consultation. Patients receiving hospice or palliative care have high rates of potentially symptomatic cutaneous diseases,5 including intertrigo and dermatitis—comprising stasis, seborrheic, and contact dermatitis.6 Although aggressive intervention for asymptomatic benign or malignant skin conditions may not be in line with their goals of care, an inpatient dermatology consultation can reduce symptoms and improve quality of life. This population also is one that is unlikely to be able to attend an outpatient dermatology clinic appointment and therefore are good candidates for inpatient consultation.

Lastly, we want to highlight the difference between a stable chronic dermatologic disease and an acute flare that may occur while a patient is hospitalized, regardless of whether it is the reason for admission. For example, a patient with psoriasis affecting limited body surface area who is hospitalized for a myocardial infarction is not appropriate for a dermatology consultation. However, if that same patient develops erythroderma while they are hospitalized for cardiac monitoring, it would certainly be appropriate for dermatology to be consulted. Additionally, there are times when a chronic skin disease is the reason for hospitalization; dermatology, although technically a consulting service, would be the primary decision-maker for the patient’s care in this situation. In these scenarios, it is important for the patient to be able to establish care for long-term outpatient management of their condition; however, it is prudent to involve dermatology while the patient is acutely hospitalized to guide their treatment plan until they are able to see a dermatologist after discharge.

In conclusion, we believe that hospital dermatology is a valuable tool that can be utilized in many different scenarios. Although there are certainly situations more appropriate for outpatient dermatology referral, we would caution against overly simplified algorithms that could discourage valuable inpatient dermatology consultations. It often is worth a conversation with your dermatology consultant (when available at an institution) to determine the best course of action for each patient. Additionally, we recognize the need for more formalized guidelines on when to pursue inpatient dermatology consultation. We are members of the Society of Dermatology Hospitalists and encourage readers to reference their website, which provides additional resources on inpatient dermatology (https://societydermatologyhospitalists.com/inpatient-dermatology-literature/).

Authors’ Response

We appreciate the letter in response to our commentary on the appropriateness of inpatient dermatology consultations. It is the continued refining and re-evaluation of concepts such as these that allow our field to grow and improve knowledge and patient care.

We sought to provide a nonpatronizing yet simple consultation flowchart that would help guide triage of patients in need or not in need of dermatologic evaluation by the inpatient teams. Understandably, the impressions of our flowchart have been variable based on different readers’ medical backgrounds and experiences. It is certainly possible that our flowchart lacked certain exceptions and oversimplified certain concepts, and we welcome further refining of this flowchart to better guide inpatient dermatology consultations.

We do, however, disagree that the primary team would not know whether a patient is intubated in the intensive care unit for a dermatology reason. If the patient is in such a status, it would be pertinent for the primary team to conduct a timely workup that could include consultations until a diagnosis is made. We were not implying that every dermatology consultation in the intensive care unit is unwarranted, especially if it can lead to a primary dermatologic diagnosis. We do believe that a thorough history could elicit an allergy or other chronic skin condition that could save resources and spending within a hospital. Likewise, psoriasis comes in many different presentations, and although we do not believe a consultation for chronic psoriatic plaques is appropriate in the hospital, it is absolutely appropriate for a patient who is erythrodermic from any cause.

Our flowchart was intended to be the first step to providing education on when consultations are appropriate, and further refinement will be necessary.

Hershel Dobkin, MD; Timothy Blackwell, BS; Robin Ashinoff, MD

Drs. Dobkin and Ashinoff are from Hackensack University Medical Center, New Jersey. Mr. Blackwell is from the Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine, Stratford, New Jersey.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Correspondence: Hershel Dobkin, MD, Hackensack University Medical Center, 30 Prospect Ave, Hackensack, NJ 07601 (hersheldobkinpublic@gmail.com).

- Dobkin H, Blackwell T, Ashinoff R. When are inpatient and emergency dermatologic consultations appropriate? Cutis. 2022;109:218-220. doi:10.12788/cutis.0492

- Ko LN, Garza-Mayers AC, St John J, et al. Effect of dermatology consultation on outcomes for patients with presumed cellulitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:529-536. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6196

- Hu L, Haynes H, Ferrazza D, et al. Impact of specialist consultations on inpatient admissions for dermatology-specific and related DRGs. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1477-1482. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2440-2

- Georgesen C, Fox LP, Harp J. Retiform purpura: a diagnostic approach. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:783-796. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.112

- Pisano C, Paladichuk H, Keeling B. Dermatology in palliative medicine [published online October 14, 2021]. BMJ Support Palliat Care. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-003342

- Barnabé C, Daeninck P. “Beauty is only skin deep”: prevalence of dermatologic disease on a palliative care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29:419-422. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.08.009

To the Editor:

We read with interest the Cutis article by Dobkin et al1 (Cutis. 2022;109:218-220) regarding guidelines for inpatient and emergency department dermatology consultations. We agree with the authors that dermatology training is lacking in other medical specialties, which makes it challenging for teams to assess the appropriateness of a dermatology consultation in the inpatient setting. Inpatient dermatology consultation can be utilized in a hospital system to aid in rapid and accurate diagnosis, avoid inappropriate therapies, and decrease length of stay2 and readmission rates3 while providing education to the primary teams. This is precisely why in many instances the availability of inpatient dermatology consultation is so important because nondermatologists often are unable to determine whether a rash is life-threatening, benign, or something in between. From the perspective of dermatology hospitalists, there is room for improvement in the flowchart Dobkin et al1 presented to guide inpatient dermatology consultation.

To have a productive relationship with our internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, psychiatry, and other hospital-based colleagues, we must keep an open mind when a consultation is received. We feel that the flowchart proposed by Dobkin et al1 presents too narrow a viewpoint on the utility of inpatient dermatology. It rests on assertions that other teams will be able to determine the appropriate dermatologic diagnosis without involving a dermatologist, which often is not the case.

We disagree with several recommendations in the flowchart, the first being the assertion that patients who are “hemodynamically unstable due to [a] nondermatologic problem (eg, intubated on pressors, febrile, and hypotensive)” are not appropriate for inpatient dermatology consultation.1 Although dermatologists do not commonly encounter patients with critical illness in the outpatient clinic, dermatology consultation can be extremely helpful and even lifesaving in the inpatient setting. It is unrealistic to expect the primary teams to know whether cutaneous manifestations potentially could be related to the patient’s overall clinical picture. On the contrary, we would encourage the primary team in charge of a hemodynamically unstable patient to consult dermatology at the first sign of an unexplained rash. Take for example an acutely ill patient who develops retiform purpura. There are well-established dermatology guidelines for the workup of retiform purpura,4 including prompt biopsy and assessment of broad, potentially life-threatening differential diagnoses from calciphylaxis to angioinvasive fungal infection. In this scenario, the dermatology consultant may render the correct diagnosis and recommend immediate treatment that could be lifesaving.

Secondly, we do not agree with the recommendation that a patient in hospice care is not appropriate for inpatient dermatology consultation. Patients receiving hospice or palliative care have high rates of potentially symptomatic cutaneous diseases,5 including intertrigo and dermatitis—comprising stasis, seborrheic, and contact dermatitis.6 Although aggressive intervention for asymptomatic benign or malignant skin conditions may not be in line with their goals of care, an inpatient dermatology consultation can reduce symptoms and improve quality of life. This population also is one that is unlikely to be able to attend an outpatient dermatology clinic appointment and therefore are good candidates for inpatient consultation.

Lastly, we want to highlight the difference between a stable chronic dermatologic disease and an acute flare that may occur while a patient is hospitalized, regardless of whether it is the reason for admission. For example, a patient with psoriasis affecting limited body surface area who is hospitalized for a myocardial infarction is not appropriate for a dermatology consultation. However, if that same patient develops erythroderma while they are hospitalized for cardiac monitoring, it would certainly be appropriate for dermatology to be consulted. Additionally, there are times when a chronic skin disease is the reason for hospitalization; dermatology, although technically a consulting service, would be the primary decision-maker for the patient’s care in this situation. In these scenarios, it is important for the patient to be able to establish care for long-term outpatient management of their condition; however, it is prudent to involve dermatology while the patient is acutely hospitalized to guide their treatment plan until they are able to see a dermatologist after discharge.

In conclusion, we believe that hospital dermatology is a valuable tool that can be utilized in many different scenarios. Although there are certainly situations more appropriate for outpatient dermatology referral, we would caution against overly simplified algorithms that could discourage valuable inpatient dermatology consultations. It often is worth a conversation with your dermatology consultant (when available at an institution) to determine the best course of action for each patient. Additionally, we recognize the need for more formalized guidelines on when to pursue inpatient dermatology consultation. We are members of the Society of Dermatology Hospitalists and encourage readers to reference their website, which provides additional resources on inpatient dermatology (https://societydermatologyhospitalists.com/inpatient-dermatology-literature/).

Authors’ Response

We appreciate the letter in response to our commentary on the appropriateness of inpatient dermatology consultations. It is the continued refining and re-evaluation of concepts such as these that allow our field to grow and improve knowledge and patient care.

We sought to provide a nonpatronizing yet simple consultation flowchart that would help guide triage of patients in need or not in need of dermatologic evaluation by the inpatient teams. Understandably, the impressions of our flowchart have been variable based on different readers’ medical backgrounds and experiences. It is certainly possible that our flowchart lacked certain exceptions and oversimplified certain concepts, and we welcome further refining of this flowchart to better guide inpatient dermatology consultations.

We do, however, disagree that the primary team would not know whether a patient is intubated in the intensive care unit for a dermatology reason. If the patient is in such a status, it would be pertinent for the primary team to conduct a timely workup that could include consultations until a diagnosis is made. We were not implying that every dermatology consultation in the intensive care unit is unwarranted, especially if it can lead to a primary dermatologic diagnosis. We do believe that a thorough history could elicit an allergy or other chronic skin condition that could save resources and spending within a hospital. Likewise, psoriasis comes in many different presentations, and although we do not believe a consultation for chronic psoriatic plaques is appropriate in the hospital, it is absolutely appropriate for a patient who is erythrodermic from any cause.

Our flowchart was intended to be the first step to providing education on when consultations are appropriate, and further refinement will be necessary.

Hershel Dobkin, MD; Timothy Blackwell, BS; Robin Ashinoff, MD

Drs. Dobkin and Ashinoff are from Hackensack University Medical Center, New Jersey. Mr. Blackwell is from the Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine, Stratford, New Jersey.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Correspondence: Hershel Dobkin, MD, Hackensack University Medical Center, 30 Prospect Ave, Hackensack, NJ 07601 (hersheldobkinpublic@gmail.com).

To the Editor:

We read with interest the Cutis article by Dobkin et al1 (Cutis. 2022;109:218-220) regarding guidelines for inpatient and emergency department dermatology consultations. We agree with the authors that dermatology training is lacking in other medical specialties, which makes it challenging for teams to assess the appropriateness of a dermatology consultation in the inpatient setting. Inpatient dermatology consultation can be utilized in a hospital system to aid in rapid and accurate diagnosis, avoid inappropriate therapies, and decrease length of stay2 and readmission rates3 while providing education to the primary teams. This is precisely why in many instances the availability of inpatient dermatology consultation is so important because nondermatologists often are unable to determine whether a rash is life-threatening, benign, or something in between. From the perspective of dermatology hospitalists, there is room for improvement in the flowchart Dobkin et al1 presented to guide inpatient dermatology consultation.

To have a productive relationship with our internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, psychiatry, and other hospital-based colleagues, we must keep an open mind when a consultation is received. We feel that the flowchart proposed by Dobkin et al1 presents too narrow a viewpoint on the utility of inpatient dermatology. It rests on assertions that other teams will be able to determine the appropriate dermatologic diagnosis without involving a dermatologist, which often is not the case.

We disagree with several recommendations in the flowchart, the first being the assertion that patients who are “hemodynamically unstable due to [a] nondermatologic problem (eg, intubated on pressors, febrile, and hypotensive)” are not appropriate for inpatient dermatology consultation.1 Although dermatologists do not commonly encounter patients with critical illness in the outpatient clinic, dermatology consultation can be extremely helpful and even lifesaving in the inpatient setting. It is unrealistic to expect the primary teams to know whether cutaneous manifestations potentially could be related to the patient’s overall clinical picture. On the contrary, we would encourage the primary team in charge of a hemodynamically unstable patient to consult dermatology at the first sign of an unexplained rash. Take for example an acutely ill patient who develops retiform purpura. There are well-established dermatology guidelines for the workup of retiform purpura,4 including prompt biopsy and assessment of broad, potentially life-threatening differential diagnoses from calciphylaxis to angioinvasive fungal infection. In this scenario, the dermatology consultant may render the correct diagnosis and recommend immediate treatment that could be lifesaving.

Secondly, we do not agree with the recommendation that a patient in hospice care is not appropriate for inpatient dermatology consultation. Patients receiving hospice or palliative care have high rates of potentially symptomatic cutaneous diseases,5 including intertrigo and dermatitis—comprising stasis, seborrheic, and contact dermatitis.6 Although aggressive intervention for asymptomatic benign or malignant skin conditions may not be in line with their goals of care, an inpatient dermatology consultation can reduce symptoms and improve quality of life. This population also is one that is unlikely to be able to attend an outpatient dermatology clinic appointment and therefore are good candidates for inpatient consultation.

Lastly, we want to highlight the difference between a stable chronic dermatologic disease and an acute flare that may occur while a patient is hospitalized, regardless of whether it is the reason for admission. For example, a patient with psoriasis affecting limited body surface area who is hospitalized for a myocardial infarction is not appropriate for a dermatology consultation. However, if that same patient develops erythroderma while they are hospitalized for cardiac monitoring, it would certainly be appropriate for dermatology to be consulted. Additionally, there are times when a chronic skin disease is the reason for hospitalization; dermatology, although technically a consulting service, would be the primary decision-maker for the patient’s care in this situation. In these scenarios, it is important for the patient to be able to establish care for long-term outpatient management of their condition; however, it is prudent to involve dermatology while the patient is acutely hospitalized to guide their treatment plan until they are able to see a dermatologist after discharge.

In conclusion, we believe that hospital dermatology is a valuable tool that can be utilized in many different scenarios. Although there are certainly situations more appropriate for outpatient dermatology referral, we would caution against overly simplified algorithms that could discourage valuable inpatient dermatology consultations. It often is worth a conversation with your dermatology consultant (when available at an institution) to determine the best course of action for each patient. Additionally, we recognize the need for more formalized guidelines on when to pursue inpatient dermatology consultation. We are members of the Society of Dermatology Hospitalists and encourage readers to reference their website, which provides additional resources on inpatient dermatology (https://societydermatologyhospitalists.com/inpatient-dermatology-literature/).

Authors’ Response

We appreciate the letter in response to our commentary on the appropriateness of inpatient dermatology consultations. It is the continued refining and re-evaluation of concepts such as these that allow our field to grow and improve knowledge and patient care.

We sought to provide a nonpatronizing yet simple consultation flowchart that would help guide triage of patients in need or not in need of dermatologic evaluation by the inpatient teams. Understandably, the impressions of our flowchart have been variable based on different readers’ medical backgrounds and experiences. It is certainly possible that our flowchart lacked certain exceptions and oversimplified certain concepts, and we welcome further refining of this flowchart to better guide inpatient dermatology consultations.

We do, however, disagree that the primary team would not know whether a patient is intubated in the intensive care unit for a dermatology reason. If the patient is in such a status, it would be pertinent for the primary team to conduct a timely workup that could include consultations until a diagnosis is made. We were not implying that every dermatology consultation in the intensive care unit is unwarranted, especially if it can lead to a primary dermatologic diagnosis. We do believe that a thorough history could elicit an allergy or other chronic skin condition that could save resources and spending within a hospital. Likewise, psoriasis comes in many different presentations, and although we do not believe a consultation for chronic psoriatic plaques is appropriate in the hospital, it is absolutely appropriate for a patient who is erythrodermic from any cause.

Our flowchart was intended to be the first step to providing education on when consultations are appropriate, and further refinement will be necessary.

Hershel Dobkin, MD; Timothy Blackwell, BS; Robin Ashinoff, MD

Drs. Dobkin and Ashinoff are from Hackensack University Medical Center, New Jersey. Mr. Blackwell is from the Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine, Stratford, New Jersey.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Correspondence: Hershel Dobkin, MD, Hackensack University Medical Center, 30 Prospect Ave, Hackensack, NJ 07601 (hersheldobkinpublic@gmail.com).

- Dobkin H, Blackwell T, Ashinoff R. When are inpatient and emergency dermatologic consultations appropriate? Cutis. 2022;109:218-220. doi:10.12788/cutis.0492

- Ko LN, Garza-Mayers AC, St John J, et al. Effect of dermatology consultation on outcomes for patients with presumed cellulitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:529-536. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6196

- Hu L, Haynes H, Ferrazza D, et al. Impact of specialist consultations on inpatient admissions for dermatology-specific and related DRGs. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1477-1482. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2440-2

- Georgesen C, Fox LP, Harp J. Retiform purpura: a diagnostic approach. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:783-796. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.112

- Pisano C, Paladichuk H, Keeling B. Dermatology in palliative medicine [published online October 14, 2021]. BMJ Support Palliat Care. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-003342

- Barnabé C, Daeninck P. “Beauty is only skin deep”: prevalence of dermatologic disease on a palliative care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29:419-422. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.08.009

- Dobkin H, Blackwell T, Ashinoff R. When are inpatient and emergency dermatologic consultations appropriate? Cutis. 2022;109:218-220. doi:10.12788/cutis.0492

- Ko LN, Garza-Mayers AC, St John J, et al. Effect of dermatology consultation on outcomes for patients with presumed cellulitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:529-536. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6196

- Hu L, Haynes H, Ferrazza D, et al. Impact of specialist consultations on inpatient admissions for dermatology-specific and related DRGs. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1477-1482. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2440-2

- Georgesen C, Fox LP, Harp J. Retiform purpura: a diagnostic approach. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:783-796. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.112

- Pisano C, Paladichuk H, Keeling B. Dermatology in palliative medicine [published online October 14, 2021]. BMJ Support Palliat Care. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-003342

- Barnabé C, Daeninck P. “Beauty is only skin deep”: prevalence of dermatologic disease on a palliative care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29:419-422. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.08.009

Differences in Underrepresented in Medicine Applicant Backgrounds and Outcomes in the 2020-2021 Dermatology Residency Match

Dermatology is one of the least diverse medical specialties with only 3% of dermatologists being Black and 4% Latinx.1 Leading dermatology organizations have called for specialty-wide efforts to improve diversity, with a particular focus on the resident selection process.2,3 Medical students who are underrepresented in medicine (UIM)(ie, those who identify as Black, Latinx, Native American, or Pacific Islander) face many potential barriers in applying to dermatology programs, including financial limitations, lack of support and mentorship, and less exposure to the specialty.1,2,4 The COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges in the residency application process with limitations on clinical, research, and volunteer experiences; decreased opportunities for in-person mentorship and away rotations; and a shift to virtual recruitment. Although there has been increased emphasis on recruiting diverse candidates to dermatology, the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated existing barriers for UIM applicants.

We surveyed dermatology residency program directors (PDs) and applicants to evaluate how UIM students approach and fare in the dermatology residency application process as well as the effects of COVID-19 on the most recent application cycle. Herein, we report the results of our surveys with a focus on racial differences in the application process.

Methods

We administered 2 anonymous online surveys—one to 115 PDs through the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) email listserve and another to applicants who participated in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency application cycle through the Dermatology Interest Group Association (DIGA) listserve. The surveys were distributed from March 29 through May 23, 2021. There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants on the DIGA listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, California) institutional review board (approval #UP-21-00118).

Participants were not required to answer every survey question; response rates varied by question. Survey responses with less than 10% completion were excluded from analysis. Data were collected, analyzed, and stored using Qualtrics, a secure online survey platform. The test of equal or given proportions in R studio was used to determine statistically significant differences between variables (P<.05 indicated statistical significance).

Results

The PD survey received 79 complete responses (83.5% complete responses, 73.8% response rate) and the applicant survey received 232 complete responses (83.6% complete responses).

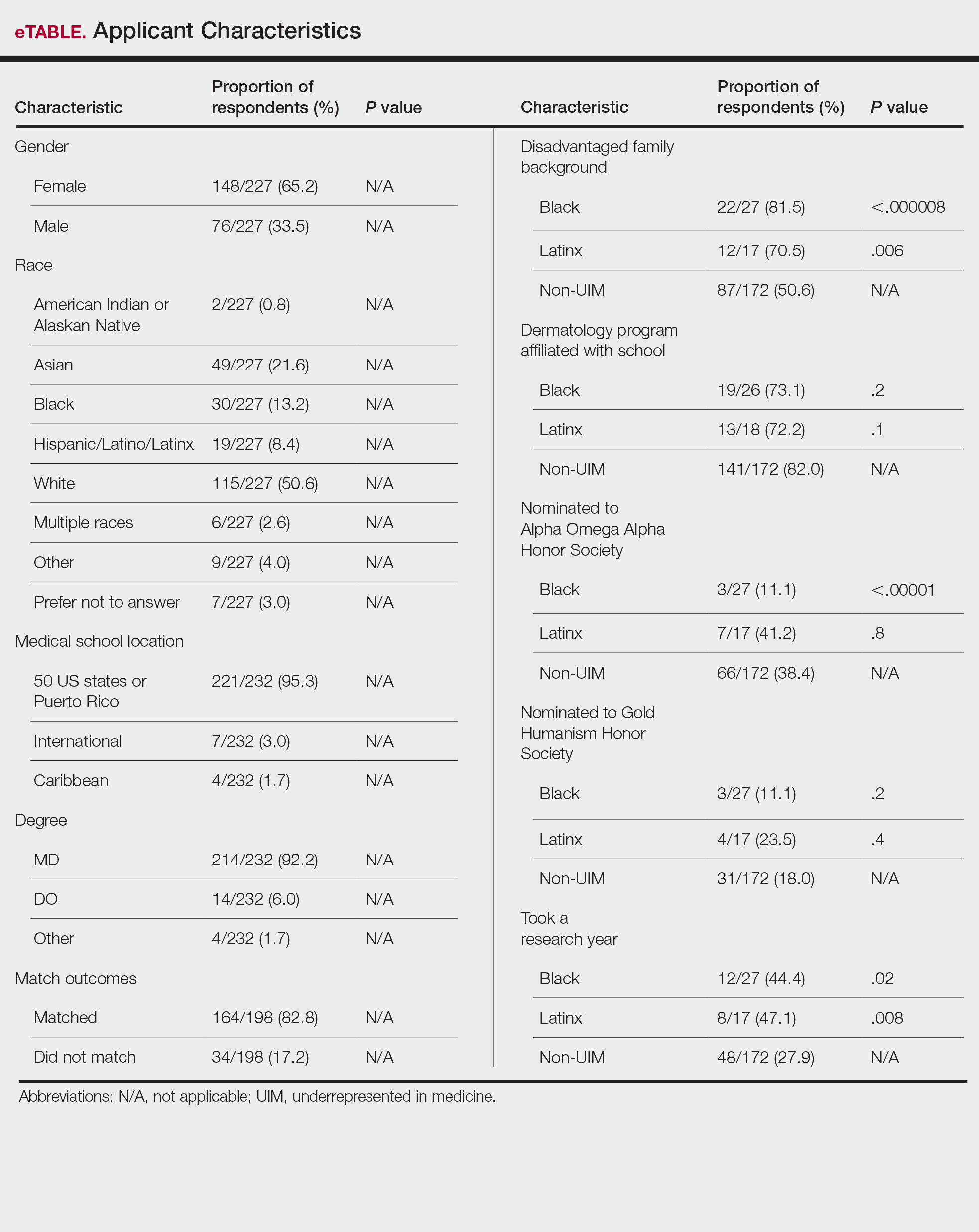

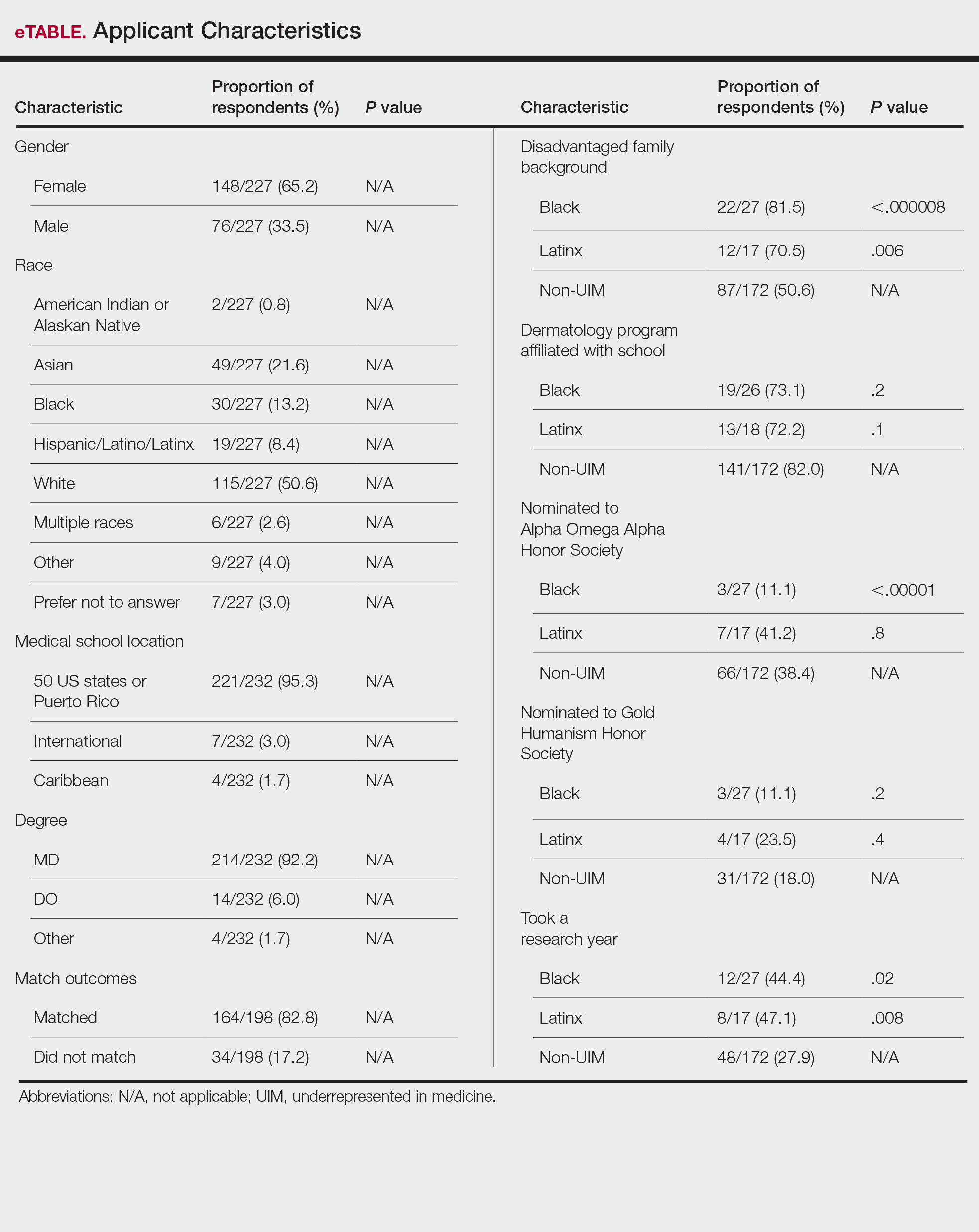

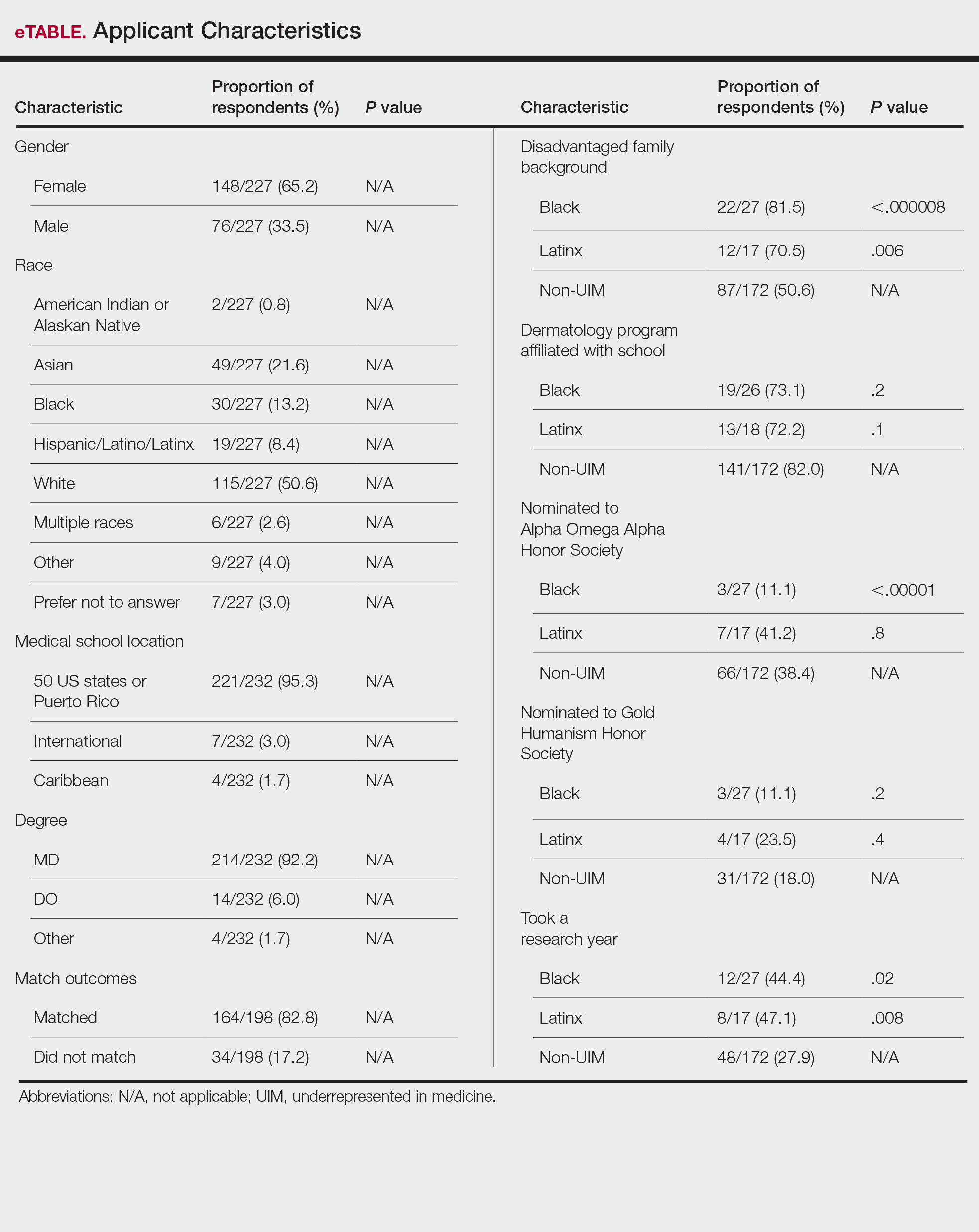

Applicant Characteristics—Applicant characteristics are provided in the eTable; 13.2% and 8.4% of participants were Black and Latinx (including those who identify as Hispanic/Latino), respectively. Only 0.8% of respondents identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native and were excluded from the analysis due to the limited sample size. Those who identified as White, Asian, multiple races, or other and those who preferred not to answer were considered non-UIM participants.

Differences in family background were observed in our cohort, with UIM candidates more likely to have experienced disadvantages, defined as being the first in their family to attend college/graduate school, growing up in a rural area, being a first-generation immigrant, or qualifying as low income. Underrepresented in medicine applicants also were less likely to have a dermatology program at their medical school (both Black and Latinx) and to have been elected to honor societies such as Alpha Omega Alpha and the Gold Humanism Honor Society (Black only).

Underrepresented in medicine applicants were more likely to complete a research gap year (eTable). Most applicants who took research years did so to improve their chances of matching, regardless of their race/ethnicity. For those who did not complete a research year, Black applicants (46.7%) were more likely to base that decision on financial limitations compared to non-UIMs (18.6%, P<.0001). Interestingly, in the PD survey, only 4.5% of respondents considered completion of a research year extremely or very important when compiling rank lists.

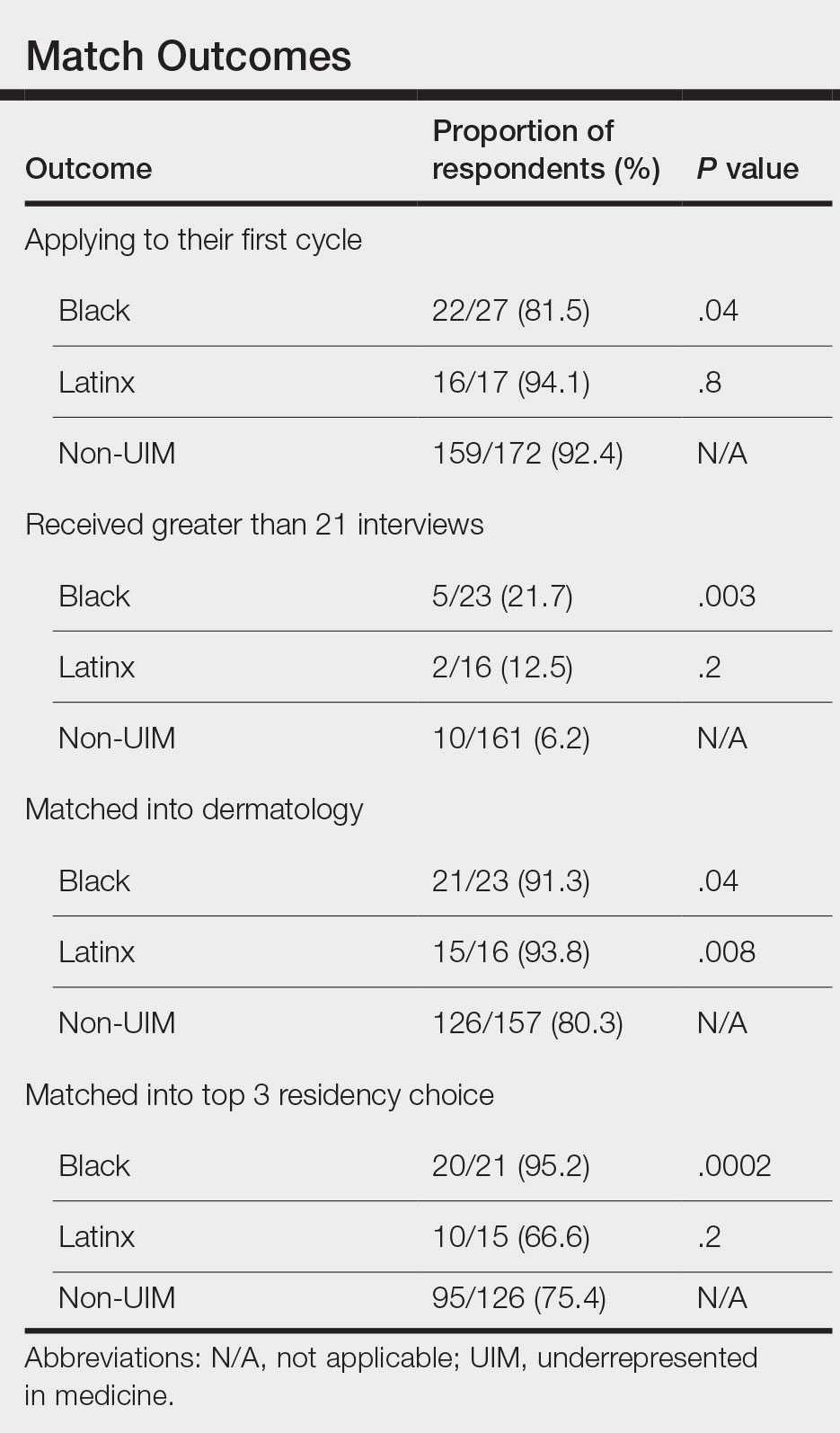

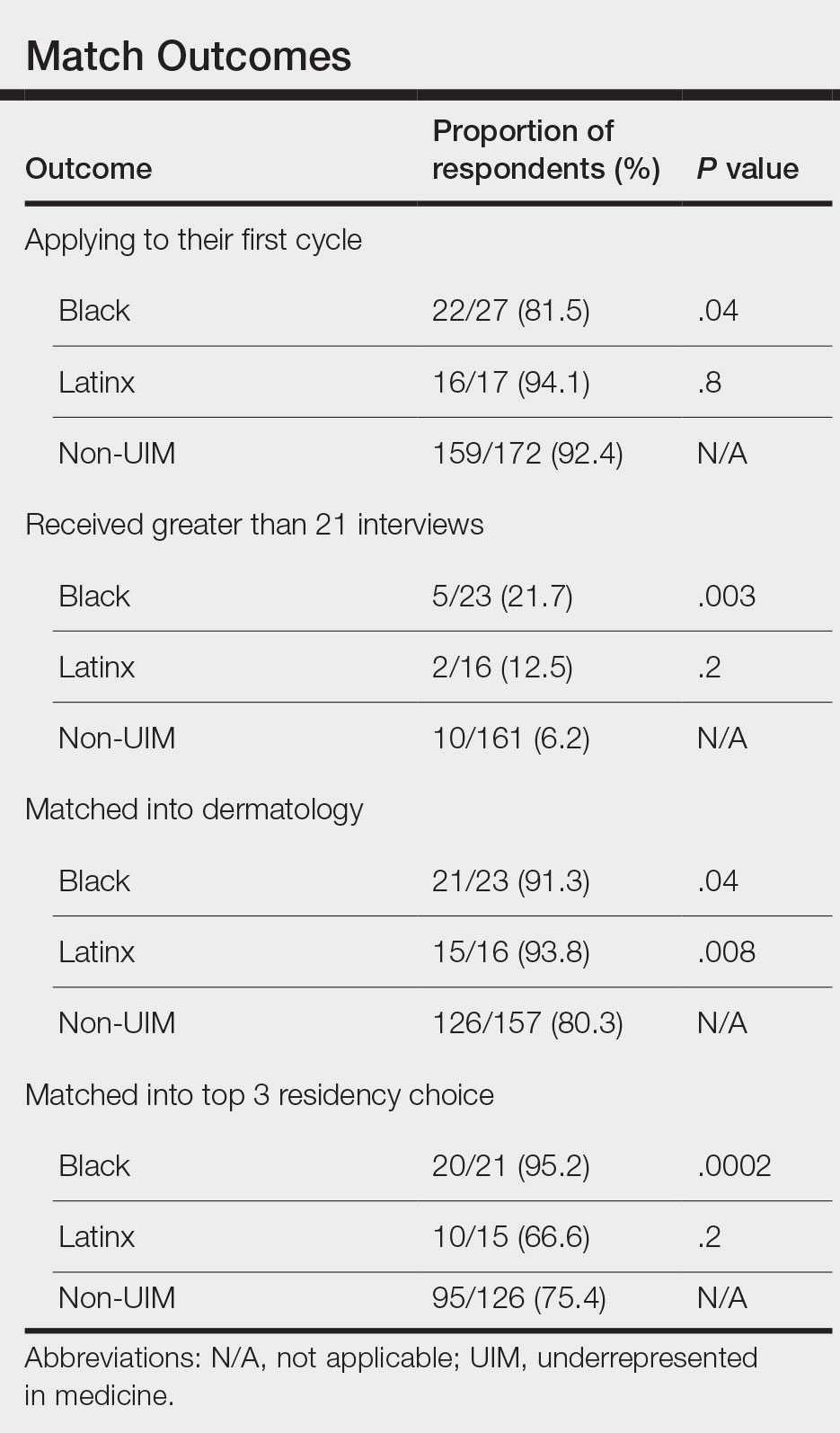

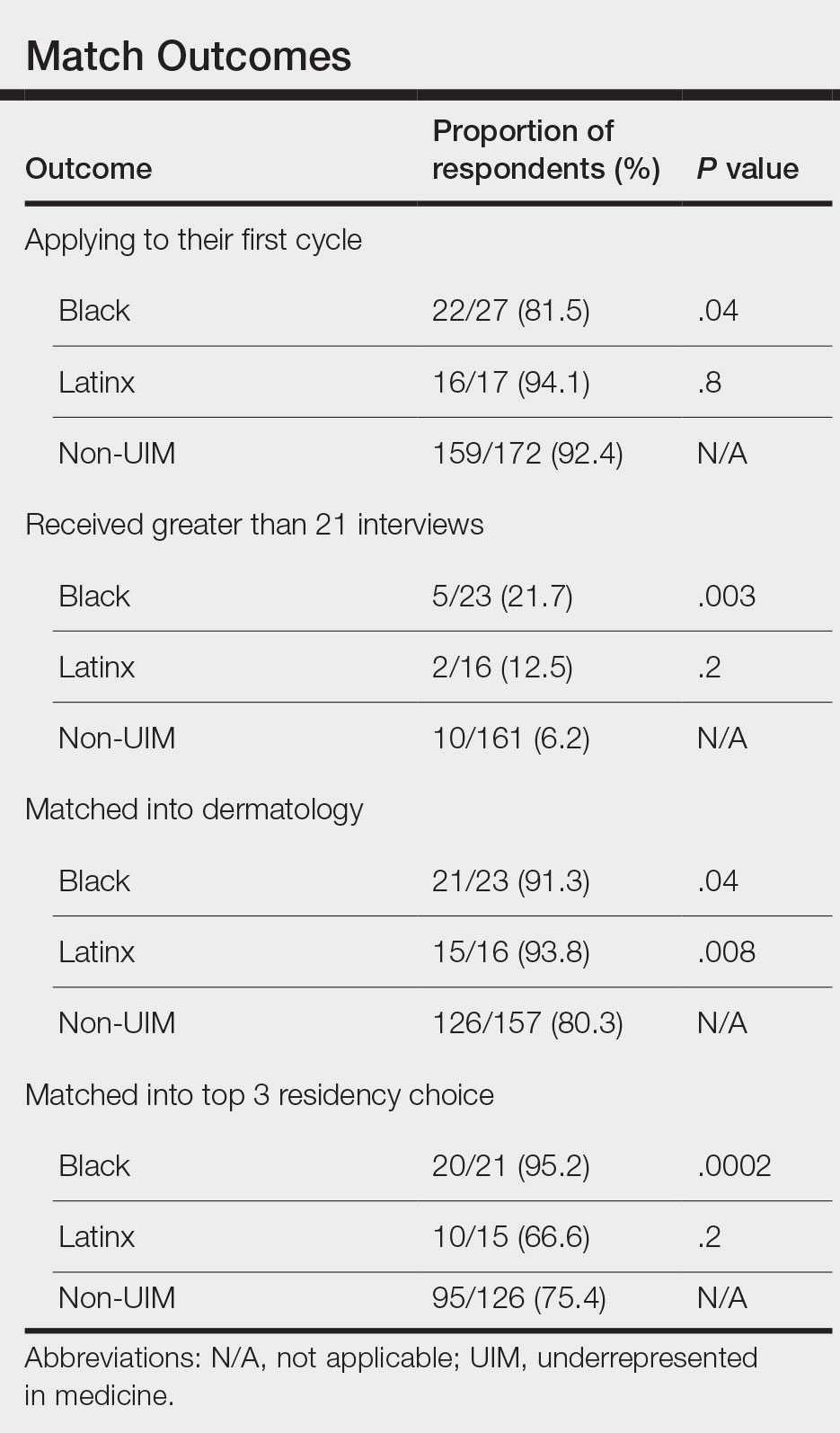

Application Process and Match Outcomes—The Table highlights differences in how UIM applicants approached the application process. Black but not Latinx applicants were less likely to be first-time applicants to dermatology compared to non-UIM applicants. Black applicants (8.3%) were significantly less likely to apply to more than 100 programs compared to non-UIM applicants (29.5%, P=.0002). Underrepresented in medicine applicants received greater numbers of interviews despite applying to fewer programs overall.

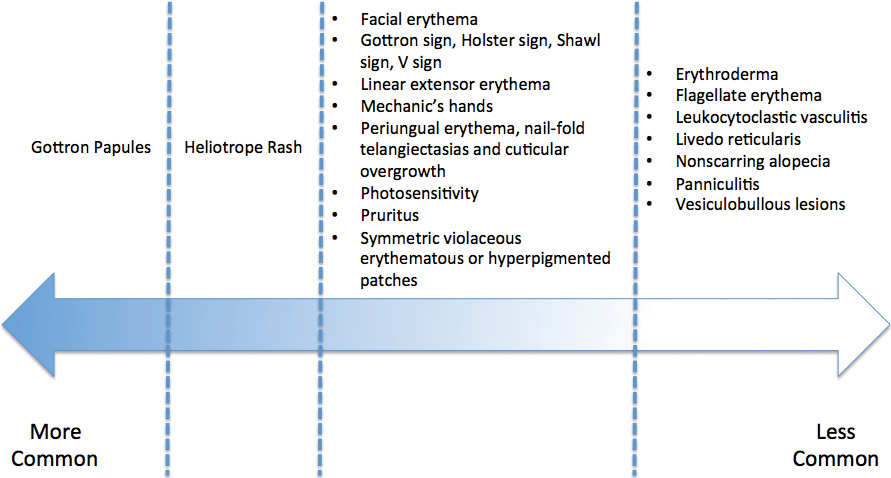

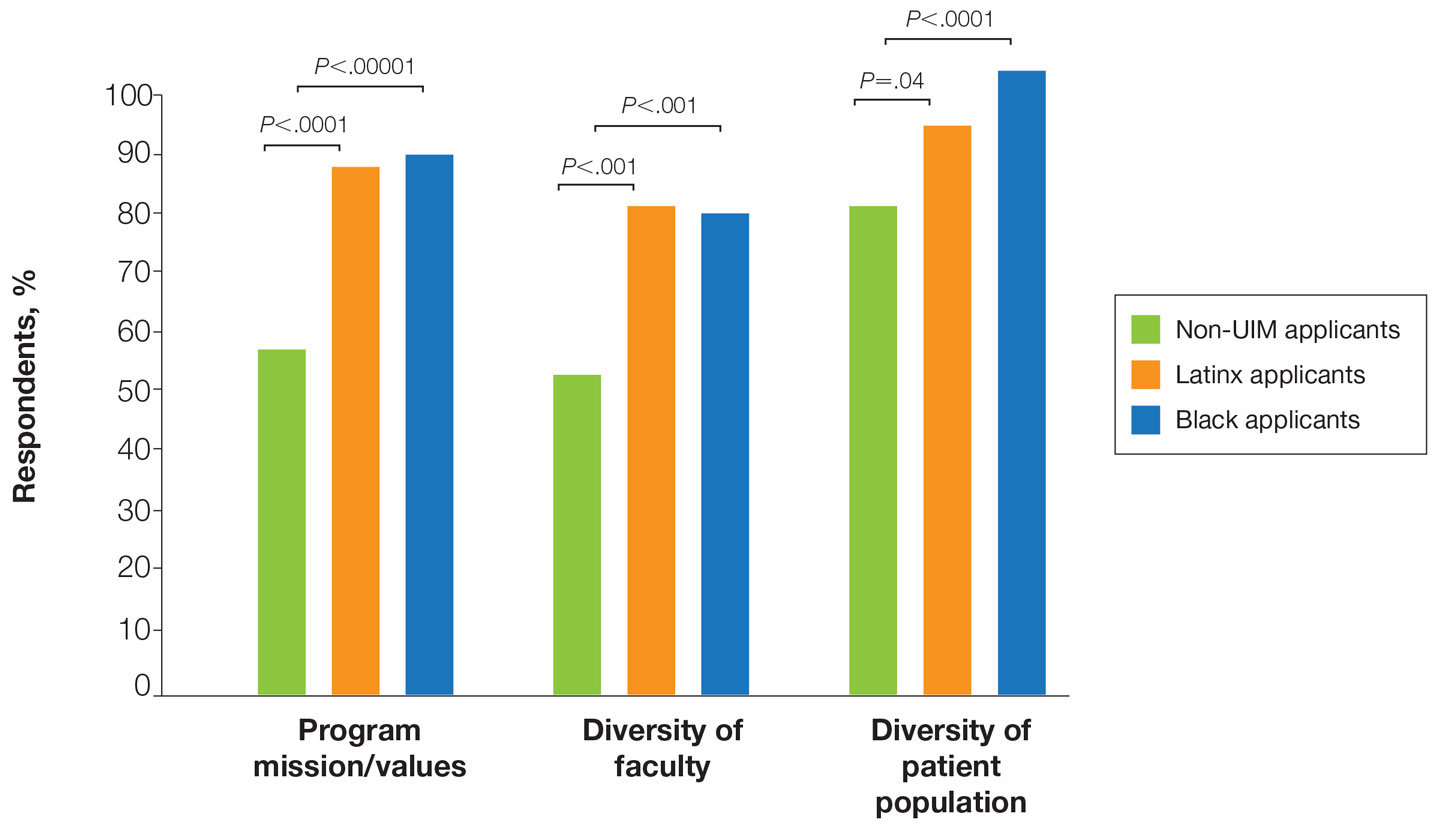

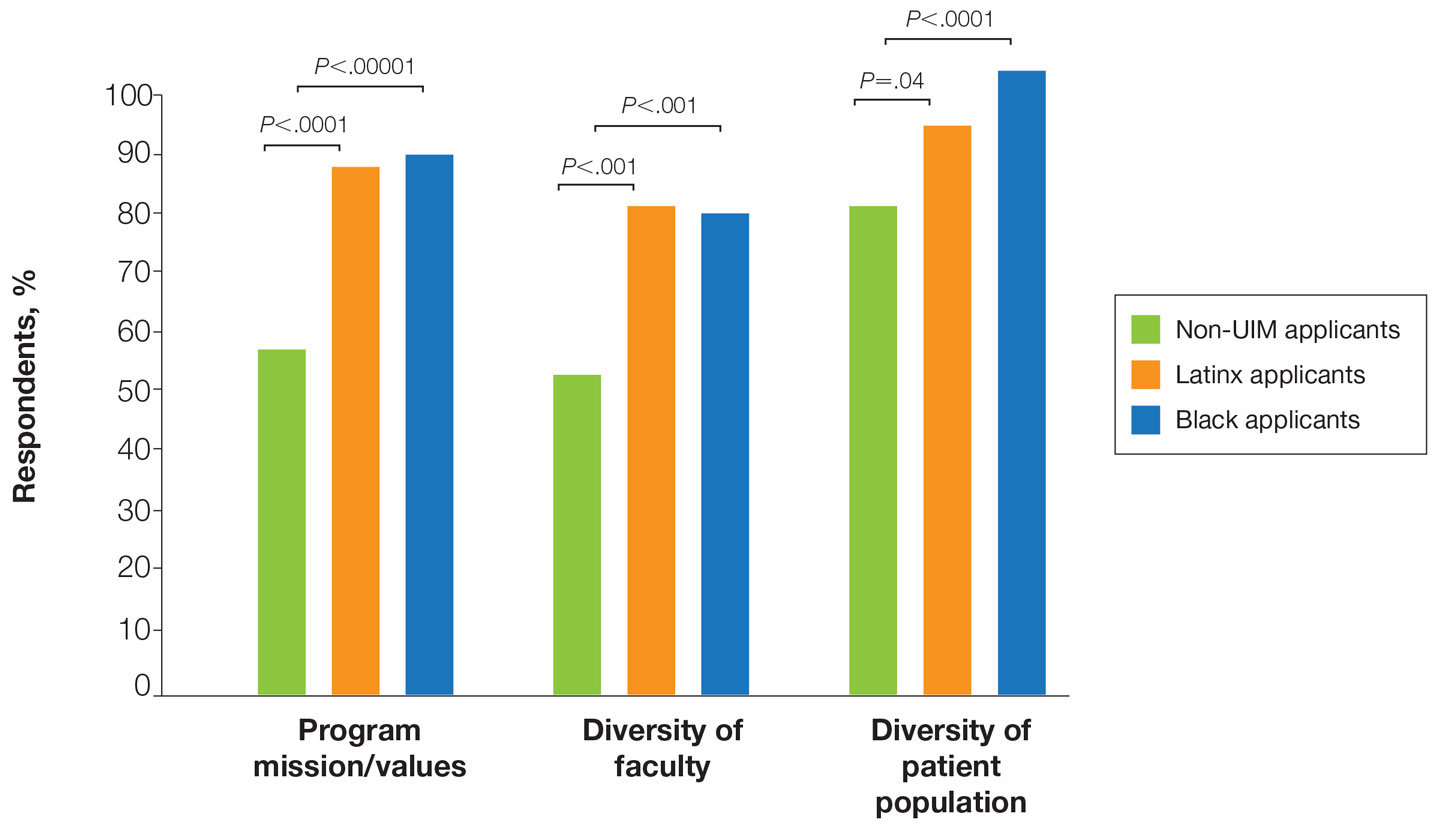

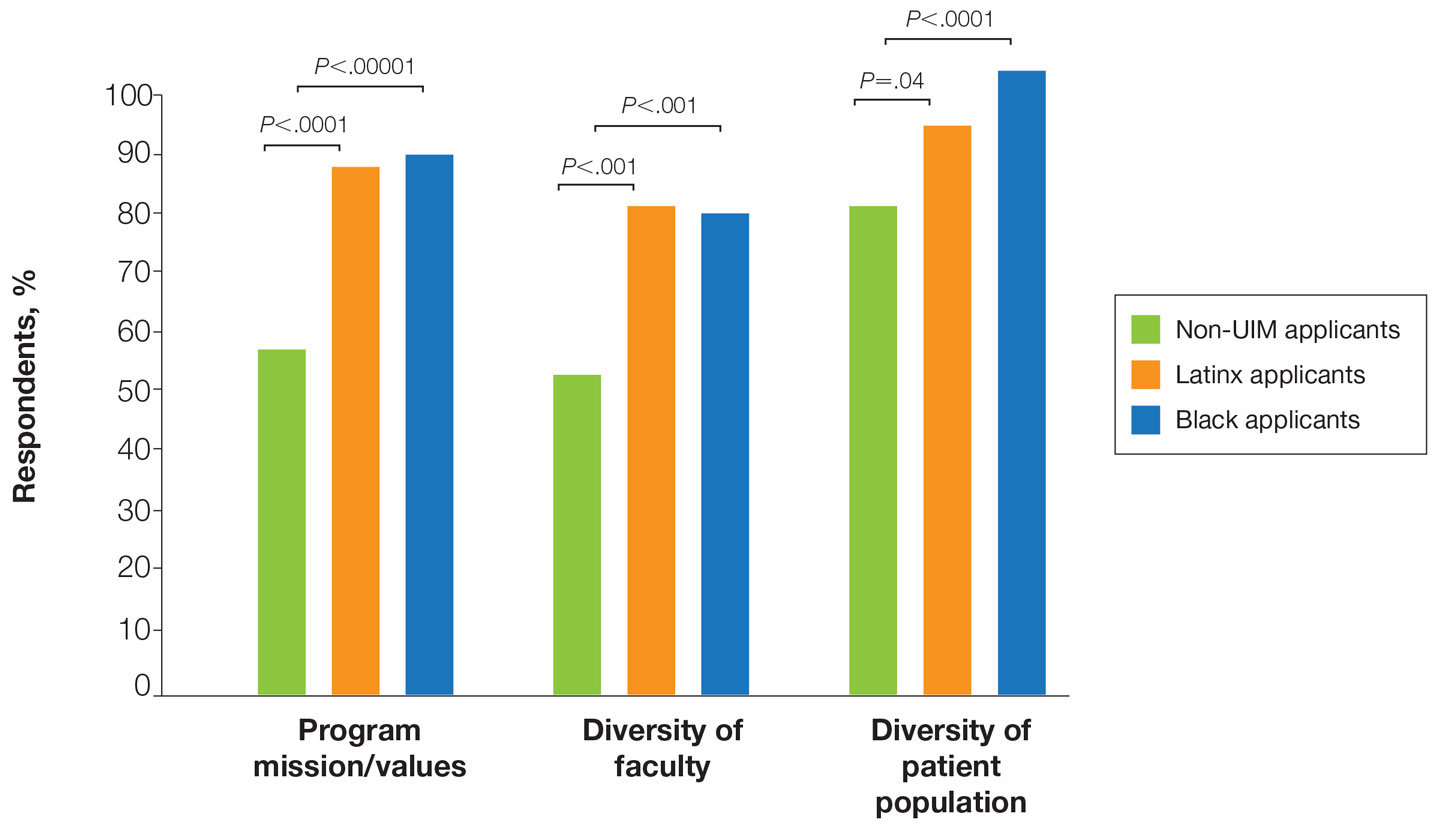

There also were differences in how UIM candidates approached their rank lists, with Black and Latinx applicants prioritizing diversity of patient populations and program faculty as well as program missions and values (Figure).

In our cohort, UIM candidates were more likely than non-UIM to match, and Black applicants were most likely to match at one of their top 3 choices (Table). In the PD survey, 77.6% of PDs considered contribution to diversity an important factor when compiling their rank lists.

Comment

Applicant Background—Dermatology is a competitive specialty with a challenging application process2 that has been further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study elucidated how the 2020-2021 application cycle affected UIM dermatology applicants. Prior studies have found that UIM medical students were more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds; financial constraints pose a major barrier for UIM and low-income students interested in dermatology.4-6 We found this to be true in our cohort, as Black and Latinx applicants were significantly more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds (P<.000008 and P=.006, respectively). Additionally, we found that Black applicants were more likely than any other group to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not taking a research gap year.

Although most applicants who completed a research year did so to increase their chances of matching, a higher percentage of UIMs took research years compared to non-UIM applicants. This finding could indicate greater anxiety about matching among UIM applicants vs their non-UIM counterparts. Black students have faced discrimination in clinical grading,7 have perceived racial discrimination in residency interviews,8,9 and have shown to be less likely to be elected to medical school honor societies.10 We found that UIM applicants were more likely to pursue a research year compared to other applicants,11 possibly because they felt additional pressure to enhance their applications or because UIM candidates were less likely to have a home dermatology program. Expansion of mentorship programs, visiting student electives, and grants for UIMs may alleviate the need for these candidates to complete a research year and reduce disparities in the application process.

Factors Influencing Rank Lists for Applicants—In our cohort, UIMs were significantly more likely to rank diversity of patients (P<.0001 for Black applicants and P=.04 for Latinx applicants) and faculty (P<.001 for Black applicants and P<.001 for Latinx applicants) as important factors in choosing a residency program. Historically, dermatology has been disproportionately White in its physician workforce and patient population.1,12 Students with lower incomes or who identify as minorities cite the lack of diversity in dermatology as a considerable barrier to pursuing a career in the specialty.4,5 Service learning, pipeline programs aimed at early exposure to dermatology, and increased access to care for diverse patient populations are important measures to improve diversity in the dermatology workforce.13-15 Residency programs should consider how to incorporate these aspects into didactic and clinical curricula to better recruit diverse candidates to the field.

Equity in the Application Process—We found that Black applicants were more likely than non-UIM applicants to be reapplicants to dermatology; however, Black applicants in our study also were more likely to receive more interview invites, match into dermatology, and match into one of their top 3 programs. These findings are interesting, particularly given concerns about equity in the application process. It is possible that Black applicants who overcome barriers to applying to dermatology ultimately are more successful applicants. Recently, there has been an increased focus in the field on diversifying dermatology, which was further intensified last year.2,3 Indicative of this shift, our PD survey showed that most programs reported that applicants’ contributions to diversity were important factors in the application process. Additionally, an emphasis by PDs on a holistic review of applications coupled with direct advocacy for increased representation may have contributed to the increased match rates for UIM applicants reported in our survey.

Latinx Applicants—Our study showed differences in how Latinx candidates fared in the application process; although Latinx applicants were more likely than their non-Latinx counterparts to match into dermatology, they were less likely than non-Latinx applicants to match into one of their top 3 programs. Given that Latinx encompasses ethnicity, not race, there may be a difference in how intentional focus on and advocacy for increasing diversity in dermatology affected different UIM applicant groups. Both race and ethnicity are social constructs rather than scientific categorizations; thus, it is difficult in survey studies such as ours to capture the intersectionality present across and between groups. Lastly, it is possible that the respondents to our applicant survey are not representative of the full cohort of UIM applicants.

Study Limitations—A major limitation of our study was that we did not have a method of reaching all dermatology applicants. Although our study shows promising results suggestive of increased diversity in the last application cycle, release of the National Resident Matching Program results from 2020-2021 with racially stratified data will be imperative to assess equity in the match process for all specialties and to confirm the generalizability of our results.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4683

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Diversity In Dermatology: Diversity Committee Approved Plan 2021-2023. Published January 26, 2021. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://assets.ctfassets.net/1ny4yoiyrqia/xQgnCE6ji5skUlcZQHS2b/65f0a9072811e11afcc33d043e02cd4d/DEI_Plan.pdf

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by under-represented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatologyresidency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Patel PM, et al. Considerations for dermatology residency applicants underrepresented in medicine amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E247.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.141

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Grbic D, Jones DJ, Case ST. The role of socioeconomic status in medical school admissions: validation of a socioeconomic indicator for use in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2015;90:953-960. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000653

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao ZC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Ellis J, Otugo O, Landry A, et al. Interviewed while Black [published online November 11, 2020]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2401-2404. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2023999

- Anthony Douglas II, Hendrix J. Black medical student considerations in the era of virtual interviews. Ann Surg. 2021;274:232-233. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004946

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623

- Runge M, Renati S, Helfrich Y. 16146 dermatology residency applicants: how many pursue a dedicated research year or dual-degree, and do their stats differ [published online December 1, 2020]? J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.304

- Stern RS. Dermatologists and office-based care of dermatologic disease in the 21st century. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:126-130. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09108.x

- Oyesanya T, Grossberg AL, Okoye GA. Increasing minority representation in the dermatology department: the Johns Hopkins experience. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1133-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2018

- Humphrey VS, James AJ. The importance of service learning in dermatology residency: an actionable approach to improve resident education and skin health equity. Cutis. 2021;107:120-122. doi:10.12788/cutis.0199

Dermatology is one of the least diverse medical specialties with only 3% of dermatologists being Black and 4% Latinx.1 Leading dermatology organizations have called for specialty-wide efforts to improve diversity, with a particular focus on the resident selection process.2,3 Medical students who are underrepresented in medicine (UIM)(ie, those who identify as Black, Latinx, Native American, or Pacific Islander) face many potential barriers in applying to dermatology programs, including financial limitations, lack of support and mentorship, and less exposure to the specialty.1,2,4 The COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges in the residency application process with limitations on clinical, research, and volunteer experiences; decreased opportunities for in-person mentorship and away rotations; and a shift to virtual recruitment. Although there has been increased emphasis on recruiting diverse candidates to dermatology, the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated existing barriers for UIM applicants.

We surveyed dermatology residency program directors (PDs) and applicants to evaluate how UIM students approach and fare in the dermatology residency application process as well as the effects of COVID-19 on the most recent application cycle. Herein, we report the results of our surveys with a focus on racial differences in the application process.

Methods

We administered 2 anonymous online surveys—one to 115 PDs through the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) email listserve and another to applicants who participated in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency application cycle through the Dermatology Interest Group Association (DIGA) listserve. The surveys were distributed from March 29 through May 23, 2021. There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants on the DIGA listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, California) institutional review board (approval #UP-21-00118).

Participants were not required to answer every survey question; response rates varied by question. Survey responses with less than 10% completion were excluded from analysis. Data were collected, analyzed, and stored using Qualtrics, a secure online survey platform. The test of equal or given proportions in R studio was used to determine statistically significant differences between variables (P<.05 indicated statistical significance).

Results

The PD survey received 79 complete responses (83.5% complete responses, 73.8% response rate) and the applicant survey received 232 complete responses (83.6% complete responses).

Applicant Characteristics—Applicant characteristics are provided in the eTable; 13.2% and 8.4% of participants were Black and Latinx (including those who identify as Hispanic/Latino), respectively. Only 0.8% of respondents identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native and were excluded from the analysis due to the limited sample size. Those who identified as White, Asian, multiple races, or other and those who preferred not to answer were considered non-UIM participants.

Differences in family background were observed in our cohort, with UIM candidates more likely to have experienced disadvantages, defined as being the first in their family to attend college/graduate school, growing up in a rural area, being a first-generation immigrant, or qualifying as low income. Underrepresented in medicine applicants also were less likely to have a dermatology program at their medical school (both Black and Latinx) and to have been elected to honor societies such as Alpha Omega Alpha and the Gold Humanism Honor Society (Black only).

Underrepresented in medicine applicants were more likely to complete a research gap year (eTable). Most applicants who took research years did so to improve their chances of matching, regardless of their race/ethnicity. For those who did not complete a research year, Black applicants (46.7%) were more likely to base that decision on financial limitations compared to non-UIMs (18.6%, P<.0001). Interestingly, in the PD survey, only 4.5% of respondents considered completion of a research year extremely or very important when compiling rank lists.

Application Process and Match Outcomes—The Table highlights differences in how UIM applicants approached the application process. Black but not Latinx applicants were less likely to be first-time applicants to dermatology compared to non-UIM applicants. Black applicants (8.3%) were significantly less likely to apply to more than 100 programs compared to non-UIM applicants (29.5%, P=.0002). Underrepresented in medicine applicants received greater numbers of interviews despite applying to fewer programs overall.

There also were differences in how UIM candidates approached their rank lists, with Black and Latinx applicants prioritizing diversity of patient populations and program faculty as well as program missions and values (Figure).

In our cohort, UIM candidates were more likely than non-UIM to match, and Black applicants were most likely to match at one of their top 3 choices (Table). In the PD survey, 77.6% of PDs considered contribution to diversity an important factor when compiling their rank lists.

Comment

Applicant Background—Dermatology is a competitive specialty with a challenging application process2 that has been further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study elucidated how the 2020-2021 application cycle affected UIM dermatology applicants. Prior studies have found that UIM medical students were more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds; financial constraints pose a major barrier for UIM and low-income students interested in dermatology.4-6 We found this to be true in our cohort, as Black and Latinx applicants were significantly more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds (P<.000008 and P=.006, respectively). Additionally, we found that Black applicants were more likely than any other group to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not taking a research gap year.

Although most applicants who completed a research year did so to increase their chances of matching, a higher percentage of UIMs took research years compared to non-UIM applicants. This finding could indicate greater anxiety about matching among UIM applicants vs their non-UIM counterparts. Black students have faced discrimination in clinical grading,7 have perceived racial discrimination in residency interviews,8,9 and have shown to be less likely to be elected to medical school honor societies.10 We found that UIM applicants were more likely to pursue a research year compared to other applicants,11 possibly because they felt additional pressure to enhance their applications or because UIM candidates were less likely to have a home dermatology program. Expansion of mentorship programs, visiting student electives, and grants for UIMs may alleviate the need for these candidates to complete a research year and reduce disparities in the application process.

Factors Influencing Rank Lists for Applicants—In our cohort, UIMs were significantly more likely to rank diversity of patients (P<.0001 for Black applicants and P=.04 for Latinx applicants) and faculty (P<.001 for Black applicants and P<.001 for Latinx applicants) as important factors in choosing a residency program. Historically, dermatology has been disproportionately White in its physician workforce and patient population.1,12 Students with lower incomes or who identify as minorities cite the lack of diversity in dermatology as a considerable barrier to pursuing a career in the specialty.4,5 Service learning, pipeline programs aimed at early exposure to dermatology, and increased access to care for diverse patient populations are important measures to improve diversity in the dermatology workforce.13-15 Residency programs should consider how to incorporate these aspects into didactic and clinical curricula to better recruit diverse candidates to the field.

Equity in the Application Process—We found that Black applicants were more likely than non-UIM applicants to be reapplicants to dermatology; however, Black applicants in our study also were more likely to receive more interview invites, match into dermatology, and match into one of their top 3 programs. These findings are interesting, particularly given concerns about equity in the application process. It is possible that Black applicants who overcome barriers to applying to dermatology ultimately are more successful applicants. Recently, there has been an increased focus in the field on diversifying dermatology, which was further intensified last year.2,3 Indicative of this shift, our PD survey showed that most programs reported that applicants’ contributions to diversity were important factors in the application process. Additionally, an emphasis by PDs on a holistic review of applications coupled with direct advocacy for increased representation may have contributed to the increased match rates for UIM applicants reported in our survey.

Latinx Applicants—Our study showed differences in how Latinx candidates fared in the application process; although Latinx applicants were more likely than their non-Latinx counterparts to match into dermatology, they were less likely than non-Latinx applicants to match into one of their top 3 programs. Given that Latinx encompasses ethnicity, not race, there may be a difference in how intentional focus on and advocacy for increasing diversity in dermatology affected different UIM applicant groups. Both race and ethnicity are social constructs rather than scientific categorizations; thus, it is difficult in survey studies such as ours to capture the intersectionality present across and between groups. Lastly, it is possible that the respondents to our applicant survey are not representative of the full cohort of UIM applicants.

Study Limitations—A major limitation of our study was that we did not have a method of reaching all dermatology applicants. Although our study shows promising results suggestive of increased diversity in the last application cycle, release of the National Resident Matching Program results from 2020-2021 with racially stratified data will be imperative to assess equity in the match process for all specialties and to confirm the generalizability of our results.

Dermatology is one of the least diverse medical specialties with only 3% of dermatologists being Black and 4% Latinx.1 Leading dermatology organizations have called for specialty-wide efforts to improve diversity, with a particular focus on the resident selection process.2,3 Medical students who are underrepresented in medicine (UIM)(ie, those who identify as Black, Latinx, Native American, or Pacific Islander) face many potential barriers in applying to dermatology programs, including financial limitations, lack of support and mentorship, and less exposure to the specialty.1,2,4 The COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges in the residency application process with limitations on clinical, research, and volunteer experiences; decreased opportunities for in-person mentorship and away rotations; and a shift to virtual recruitment. Although there has been increased emphasis on recruiting diverse candidates to dermatology, the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated existing barriers for UIM applicants.

We surveyed dermatology residency program directors (PDs) and applicants to evaluate how UIM students approach and fare in the dermatology residency application process as well as the effects of COVID-19 on the most recent application cycle. Herein, we report the results of our surveys with a focus on racial differences in the application process.

Methods

We administered 2 anonymous online surveys—one to 115 PDs through the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) email listserve and another to applicants who participated in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency application cycle through the Dermatology Interest Group Association (DIGA) listserve. The surveys were distributed from March 29 through May 23, 2021. There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants on the DIGA listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, California) institutional review board (approval #UP-21-00118).

Participants were not required to answer every survey question; response rates varied by question. Survey responses with less than 10% completion were excluded from analysis. Data were collected, analyzed, and stored using Qualtrics, a secure online survey platform. The test of equal or given proportions in R studio was used to determine statistically significant differences between variables (P<.05 indicated statistical significance).

Results

The PD survey received 79 complete responses (83.5% complete responses, 73.8% response rate) and the applicant survey received 232 complete responses (83.6% complete responses).

Applicant Characteristics—Applicant characteristics are provided in the eTable; 13.2% and 8.4% of participants were Black and Latinx (including those who identify as Hispanic/Latino), respectively. Only 0.8% of respondents identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native and were excluded from the analysis due to the limited sample size. Those who identified as White, Asian, multiple races, or other and those who preferred not to answer were considered non-UIM participants.

Differences in family background were observed in our cohort, with UIM candidates more likely to have experienced disadvantages, defined as being the first in their family to attend college/graduate school, growing up in a rural area, being a first-generation immigrant, or qualifying as low income. Underrepresented in medicine applicants also were less likely to have a dermatology program at their medical school (both Black and Latinx) and to have been elected to honor societies such as Alpha Omega Alpha and the Gold Humanism Honor Society (Black only).

Underrepresented in medicine applicants were more likely to complete a research gap year (eTable). Most applicants who took research years did so to improve their chances of matching, regardless of their race/ethnicity. For those who did not complete a research year, Black applicants (46.7%) were more likely to base that decision on financial limitations compared to non-UIMs (18.6%, P<.0001). Interestingly, in the PD survey, only 4.5% of respondents considered completion of a research year extremely or very important when compiling rank lists.

Application Process and Match Outcomes—The Table highlights differences in how UIM applicants approached the application process. Black but not Latinx applicants were less likely to be first-time applicants to dermatology compared to non-UIM applicants. Black applicants (8.3%) were significantly less likely to apply to more than 100 programs compared to non-UIM applicants (29.5%, P=.0002). Underrepresented in medicine applicants received greater numbers of interviews despite applying to fewer programs overall.

There also were differences in how UIM candidates approached their rank lists, with Black and Latinx applicants prioritizing diversity of patient populations and program faculty as well as program missions and values (Figure).

In our cohort, UIM candidates were more likely than non-UIM to match, and Black applicants were most likely to match at one of their top 3 choices (Table). In the PD survey, 77.6% of PDs considered contribution to diversity an important factor when compiling their rank lists.

Comment

Applicant Background—Dermatology is a competitive specialty with a challenging application process2 that has been further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study elucidated how the 2020-2021 application cycle affected UIM dermatology applicants. Prior studies have found that UIM medical students were more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds; financial constraints pose a major barrier for UIM and low-income students interested in dermatology.4-6 We found this to be true in our cohort, as Black and Latinx applicants were significantly more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds (P<.000008 and P=.006, respectively). Additionally, we found that Black applicants were more likely than any other group to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not taking a research gap year.

Although most applicants who completed a research year did so to increase their chances of matching, a higher percentage of UIMs took research years compared to non-UIM applicants. This finding could indicate greater anxiety about matching among UIM applicants vs their non-UIM counterparts. Black students have faced discrimination in clinical grading,7 have perceived racial discrimination in residency interviews,8,9 and have shown to be less likely to be elected to medical school honor societies.10 We found that UIM applicants were more likely to pursue a research year compared to other applicants,11 possibly because they felt additional pressure to enhance their applications or because UIM candidates were less likely to have a home dermatology program. Expansion of mentorship programs, visiting student electives, and grants for UIMs may alleviate the need for these candidates to complete a research year and reduce disparities in the application process.

Factors Influencing Rank Lists for Applicants—In our cohort, UIMs were significantly more likely to rank diversity of patients (P<.0001 for Black applicants and P=.04 for Latinx applicants) and faculty (P<.001 for Black applicants and P<.001 for Latinx applicants) as important factors in choosing a residency program. Historically, dermatology has been disproportionately White in its physician workforce and patient population.1,12 Students with lower incomes or who identify as minorities cite the lack of diversity in dermatology as a considerable barrier to pursuing a career in the specialty.4,5 Service learning, pipeline programs aimed at early exposure to dermatology, and increased access to care for diverse patient populations are important measures to improve diversity in the dermatology workforce.13-15 Residency programs should consider how to incorporate these aspects into didactic and clinical curricula to better recruit diverse candidates to the field.

Equity in the Application Process—We found that Black applicants were more likely than non-UIM applicants to be reapplicants to dermatology; however, Black applicants in our study also were more likely to receive more interview invites, match into dermatology, and match into one of their top 3 programs. These findings are interesting, particularly given concerns about equity in the application process. It is possible that Black applicants who overcome barriers to applying to dermatology ultimately are more successful applicants. Recently, there has been an increased focus in the field on diversifying dermatology, which was further intensified last year.2,3 Indicative of this shift, our PD survey showed that most programs reported that applicants’ contributions to diversity were important factors in the application process. Additionally, an emphasis by PDs on a holistic review of applications coupled with direct advocacy for increased representation may have contributed to the increased match rates for UIM applicants reported in our survey.

Latinx Applicants—Our study showed differences in how Latinx candidates fared in the application process; although Latinx applicants were more likely than their non-Latinx counterparts to match into dermatology, they were less likely than non-Latinx applicants to match into one of their top 3 programs. Given that Latinx encompasses ethnicity, not race, there may be a difference in how intentional focus on and advocacy for increasing diversity in dermatology affected different UIM applicant groups. Both race and ethnicity are social constructs rather than scientific categorizations; thus, it is difficult in survey studies such as ours to capture the intersectionality present across and between groups. Lastly, it is possible that the respondents to our applicant survey are not representative of the full cohort of UIM applicants.

Study Limitations—A major limitation of our study was that we did not have a method of reaching all dermatology applicants. Although our study shows promising results suggestive of increased diversity in the last application cycle, release of the National Resident Matching Program results from 2020-2021 with racially stratified data will be imperative to assess equity in the match process for all specialties and to confirm the generalizability of our results.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4683

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Diversity In Dermatology: Diversity Committee Approved Plan 2021-2023. Published January 26, 2021. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://assets.ctfassets.net/1ny4yoiyrqia/xQgnCE6ji5skUlcZQHS2b/65f0a9072811e11afcc33d043e02cd4d/DEI_Plan.pdf

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by under-represented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatologyresidency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Patel PM, et al. Considerations for dermatology residency applicants underrepresented in medicine amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E247.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.141

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Grbic D, Jones DJ, Case ST. The role of socioeconomic status in medical school admissions: validation of a socioeconomic indicator for use in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2015;90:953-960. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000653

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao ZC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Ellis J, Otugo O, Landry A, et al. Interviewed while Black [published online November 11, 2020]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2401-2404. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2023999

- Anthony Douglas II, Hendrix J. Black medical student considerations in the era of virtual interviews. Ann Surg. 2021;274:232-233. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004946

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623

- Runge M, Renati S, Helfrich Y. 16146 dermatology residency applicants: how many pursue a dedicated research year or dual-degree, and do their stats differ [published online December 1, 2020]? J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.304

- Stern RS. Dermatologists and office-based care of dermatologic disease in the 21st century. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:126-130. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09108.x

- Oyesanya T, Grossberg AL, Okoye GA. Increasing minority representation in the dermatology department: the Johns Hopkins experience. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1133-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2018

- Humphrey VS, James AJ. The importance of service learning in dermatology residency: an actionable approach to improve resident education and skin health equity. Cutis. 2021;107:120-122. doi:10.12788/cutis.0199

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4683

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Diversity In Dermatology: Diversity Committee Approved Plan 2021-2023. Published January 26, 2021. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://assets.ctfassets.net/1ny4yoiyrqia/xQgnCE6ji5skUlcZQHS2b/65f0a9072811e11afcc33d043e02cd4d/DEI_Plan.pdf

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by under-represented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatologyresidency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Patel PM, et al. Considerations for dermatology residency applicants underrepresented in medicine amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E247.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.141

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Grbic D, Jones DJ, Case ST. The role of socioeconomic status in medical school admissions: validation of a socioeconomic indicator for use in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2015;90:953-960. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000653

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao ZC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Ellis J, Otugo O, Landry A, et al. Interviewed while Black [published online November 11, 2020]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2401-2404. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2023999

- Anthony Douglas II, Hendrix J. Black medical student considerations in the era of virtual interviews. Ann Surg. 2021;274:232-233. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004946

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623

- Runge M, Renati S, Helfrich Y. 16146 dermatology residency applicants: how many pursue a dedicated research year or dual-degree, and do their stats differ [published online December 1, 2020]? J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.304

- Stern RS. Dermatologists and office-based care of dermatologic disease in the 21st century. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:126-130. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09108.x

- Oyesanya T, Grossberg AL, Okoye GA. Increasing minority representation in the dermatology department: the Johns Hopkins experience. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1133-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2018

- Humphrey VS, James AJ. The importance of service learning in dermatology residency: an actionable approach to improve resident education and skin health equity. Cutis. 2021;107:120-122. doi:10.12788/cutis.0199

Practice Points

- Underrepresented in medicine (UIM) dermatology residency applicants (Black and Latinx) are more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds and to have financial concerns about the residency application process.

- When choosing a dermatology residency program, diversity of patients and faculty are more important to UIM dermatology residency applicants than to their non-UIM counterparts.

- Increased awareness of and focus on a holistic review process by dermatology residency programs may contribute to higher rates of matching among Black applicants in our study.

Residency Roundup: Introducing a New Partnership Between Cutis and the APD-RPDS

We are excited to announce a new partnership between Cutis and the Association of Professors of Dermatology Residency Program Directors Section (APD-RPDS). The new APD-RPDS column Residency Roundup will contain quarterly communications and submissions that we hope will facilitate greater dissemination of information that is useful to the dermatology teaching community.

The APD is a group of academic dermatologists whose membership comprises chairs, chiefs, residency and fellowship program directors, and teaching faculty. Each fall, the group convenes in Chicago, Illinois, for a 2-day meeting centered around departmental and program leadership with a focus on education. The APD-RPDS was formed in 2020 and is led by a steering committee of 9 members, including our current Chair, Ilana S. Rosman, MD (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri), and Vice Chair, Jo-Ann M. Latkowski, MD (New York University, New York). Committee members are elected from and by the APD membership and must serve in program leadership at their home programs. The APD-RPDS helps plan and coordinate breakout sessions and lectures at the annual APD meeting, which typically relate to program director duties, changing policies within the American Board of Dermatology or Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, ideas for future growth, and changes in our specialty and in resident education. Members of the APD-RPDS have access to the APD listserv, a valuable resource for discussing issues affecting residency training. We also have work groups led by our members, which include diversity, equity, and inclusion; resource development; communications; and the annual survey. To join the APD, the RPDS, and/or any of our workgroups, please reach out to us or visit the APD website (https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org).

We look forward to welcoming and expediently reviewing members’ submissions to the new Residency Roundup column falling into 2 principal categories within the scope of dermatologic recruitment, didactic education, and clinical training. The first category will feature novel tools, programs, and platforms to improve dermatology training through collaboration. This could entail a description of a new platform designed for sharing resources among programs and specialties to enhance learning for trainees and faculty alike. For example, if a database is created that contains prerecorded lectures pertaining to alopecia, a potential article submission might introduce the database and provide information on what topics are covered and how to access these lectures for readers worldwide. Likewise, if a new technology emerges that allows for easier collaboration among programs, a possible submission would introduce the technology and discuss its potential benefits to trainees, faculty, and practicing dermatologists.

Secondly and more commonly, we anticipate the Residency Roundup column will feature articles that delve into the critical issues and challenges currently impacting recruitment, training, and administration in dermatology residency programs. Specific topics may include but are not limited to recruitment of underrepresented in medicine applicants to dermatology, technological advances to improve teaching methods within training programs, surveys delving into the dermatology match process, and educational gaps or future directions in the specialty. The column occasionally may be used to disseminate information from our section of the APD, including consensus statements or editorials related to changes implemented in the dermatology residency application process. A prospective editorial on this subject could explore varying viewpoints of implemented and proposed changes as well as the reasons behind the changes.

Our group is collaborative, and our aim is to improve education, equity, management of program director responsibilities, and the dermatology application process for programs and applicants alike. With your input, experience, and varied perspectives, we look forward to moving the field of dermatology to a better future by working together.

We are excited to announce a new partnership between Cutis and the Association of Professors of Dermatology Residency Program Directors Section (APD-RPDS). The new APD-RPDS column Residency Roundup will contain quarterly communications and submissions that we hope will facilitate greater dissemination of information that is useful to the dermatology teaching community.

The APD is a group of academic dermatologists whose membership comprises chairs, chiefs, residency and fellowship program directors, and teaching faculty. Each fall, the group convenes in Chicago, Illinois, for a 2-day meeting centered around departmental and program leadership with a focus on education. The APD-RPDS was formed in 2020 and is led by a steering committee of 9 members, including our current Chair, Ilana S. Rosman, MD (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri), and Vice Chair, Jo-Ann M. Latkowski, MD (New York University, New York). Committee members are elected from and by the APD membership and must serve in program leadership at their home programs. The APD-RPDS helps plan and coordinate breakout sessions and lectures at the annual APD meeting, which typically relate to program director duties, changing policies within the American Board of Dermatology or Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, ideas for future growth, and changes in our specialty and in resident education. Members of the APD-RPDS have access to the APD listserv, a valuable resource for discussing issues affecting residency training. We also have work groups led by our members, which include diversity, equity, and inclusion; resource development; communications; and the annual survey. To join the APD, the RPDS, and/or any of our workgroups, please reach out to us or visit the APD website (https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org).

We look forward to welcoming and expediently reviewing members’ submissions to the new Residency Roundup column falling into 2 principal categories within the scope of dermatologic recruitment, didactic education, and clinical training. The first category will feature novel tools, programs, and platforms to improve dermatology training through collaboration. This could entail a description of a new platform designed for sharing resources among programs and specialties to enhance learning for trainees and faculty alike. For example, if a database is created that contains prerecorded lectures pertaining to alopecia, a potential article submission might introduce the database and provide information on what topics are covered and how to access these lectures for readers worldwide. Likewise, if a new technology emerges that allows for easier collaboration among programs, a possible submission would introduce the technology and discuss its potential benefits to trainees, faculty, and practicing dermatologists.

Secondly and more commonly, we anticipate the Residency Roundup column will feature articles that delve into the critical issues and challenges currently impacting recruitment, training, and administration in dermatology residency programs. Specific topics may include but are not limited to recruitment of underrepresented in medicine applicants to dermatology, technological advances to improve teaching methods within training programs, surveys delving into the dermatology match process, and educational gaps or future directions in the specialty. The column occasionally may be used to disseminate information from our section of the APD, including consensus statements or editorials related to changes implemented in the dermatology residency application process. A prospective editorial on this subject could explore varying viewpoints of implemented and proposed changes as well as the reasons behind the changes.

Our group is collaborative, and our aim is to improve education, equity, management of program director responsibilities, and the dermatology application process for programs and applicants alike. With your input, experience, and varied perspectives, we look forward to moving the field of dermatology to a better future by working together.

We are excited to announce a new partnership between Cutis and the Association of Professors of Dermatology Residency Program Directors Section (APD-RPDS). The new APD-RPDS column Residency Roundup will contain quarterly communications and submissions that we hope will facilitate greater dissemination of information that is useful to the dermatology teaching community.

The APD is a group of academic dermatologists whose membership comprises chairs, chiefs, residency and fellowship program directors, and teaching faculty. Each fall, the group convenes in Chicago, Illinois, for a 2-day meeting centered around departmental and program leadership with a focus on education. The APD-RPDS was formed in 2020 and is led by a steering committee of 9 members, including our current Chair, Ilana S. Rosman, MD (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri), and Vice Chair, Jo-Ann M. Latkowski, MD (New York University, New York). Committee members are elected from and by the APD membership and must serve in program leadership at their home programs. The APD-RPDS helps plan and coordinate breakout sessions and lectures at the annual APD meeting, which typically relate to program director duties, changing policies within the American Board of Dermatology or Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, ideas for future growth, and changes in our specialty and in resident education. Members of the APD-RPDS have access to the APD listserv, a valuable resource for discussing issues affecting residency training. We also have work groups led by our members, which include diversity, equity, and inclusion; resource development; communications; and the annual survey. To join the APD, the RPDS, and/or any of our workgroups, please reach out to us or visit the APD website (https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org).