User login

Differences in Underrepresented in Medicine Applicant Backgrounds and Outcomes in the 2020-2021 Dermatology Residency Match

Dermatology is one of the least diverse medical specialties with only 3% of dermatologists being Black and 4% Latinx.1 Leading dermatology organizations have called for specialty-wide efforts to improve diversity, with a particular focus on the resident selection process.2,3 Medical students who are underrepresented in medicine (UIM)(ie, those who identify as Black, Latinx, Native American, or Pacific Islander) face many potential barriers in applying to dermatology programs, including financial limitations, lack of support and mentorship, and less exposure to the specialty.1,2,4 The COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges in the residency application process with limitations on clinical, research, and volunteer experiences; decreased opportunities for in-person mentorship and away rotations; and a shift to virtual recruitment. Although there has been increased emphasis on recruiting diverse candidates to dermatology, the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated existing barriers for UIM applicants.

We surveyed dermatology residency program directors (PDs) and applicants to evaluate how UIM students approach and fare in the dermatology residency application process as well as the effects of COVID-19 on the most recent application cycle. Herein, we report the results of our surveys with a focus on racial differences in the application process.

Methods

We administered 2 anonymous online surveys—one to 115 PDs through the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) email listserve and another to applicants who participated in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency application cycle through the Dermatology Interest Group Association (DIGA) listserve. The surveys were distributed from March 29 through May 23, 2021. There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants on the DIGA listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, California) institutional review board (approval #UP-21-00118).

Participants were not required to answer every survey question; response rates varied by question. Survey responses with less than 10% completion were excluded from analysis. Data were collected, analyzed, and stored using Qualtrics, a secure online survey platform. The test of equal or given proportions in R studio was used to determine statistically significant differences between variables (P<.05 indicated statistical significance).

Results

The PD survey received 79 complete responses (83.5% complete responses, 73.8% response rate) and the applicant survey received 232 complete responses (83.6% complete responses).

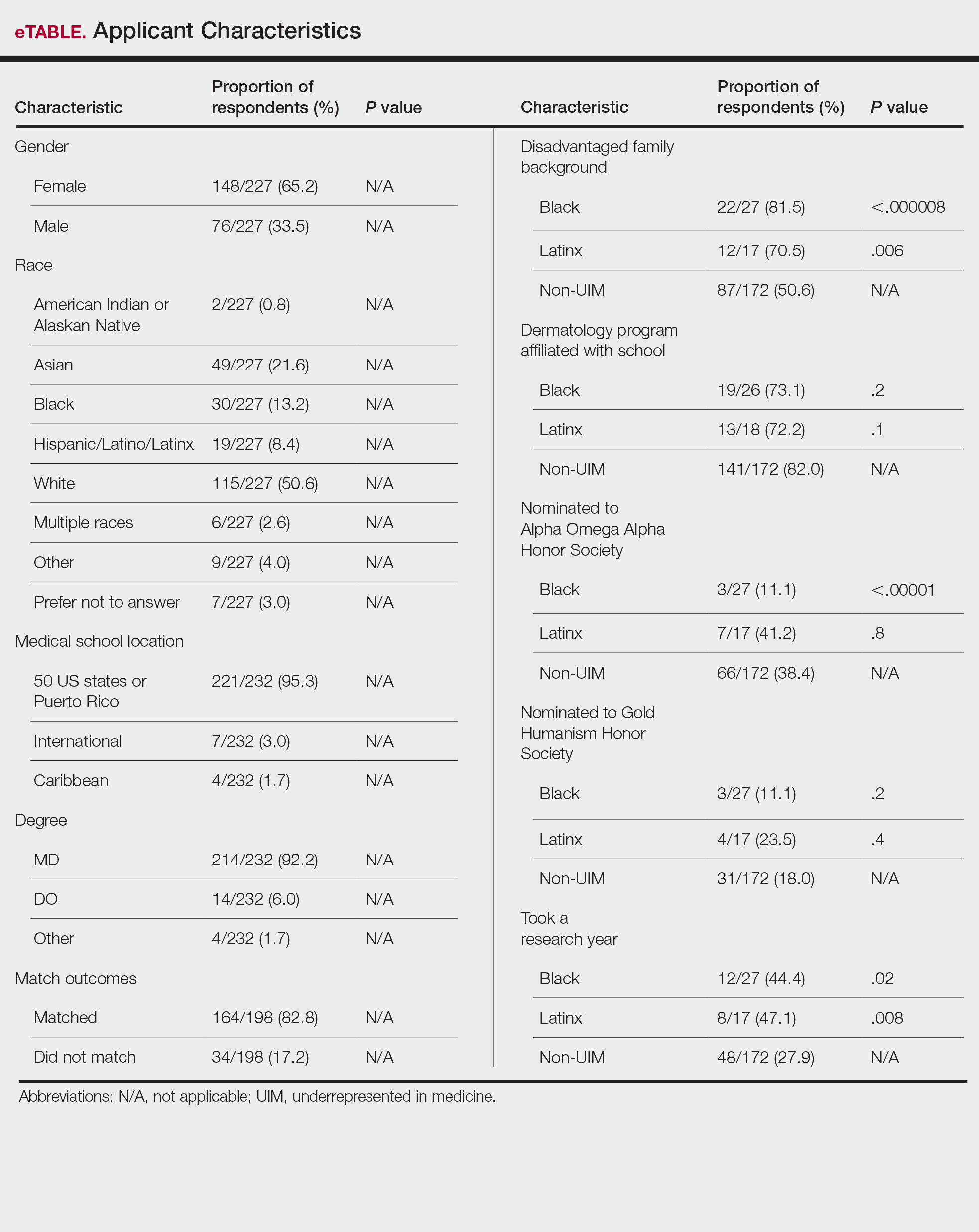

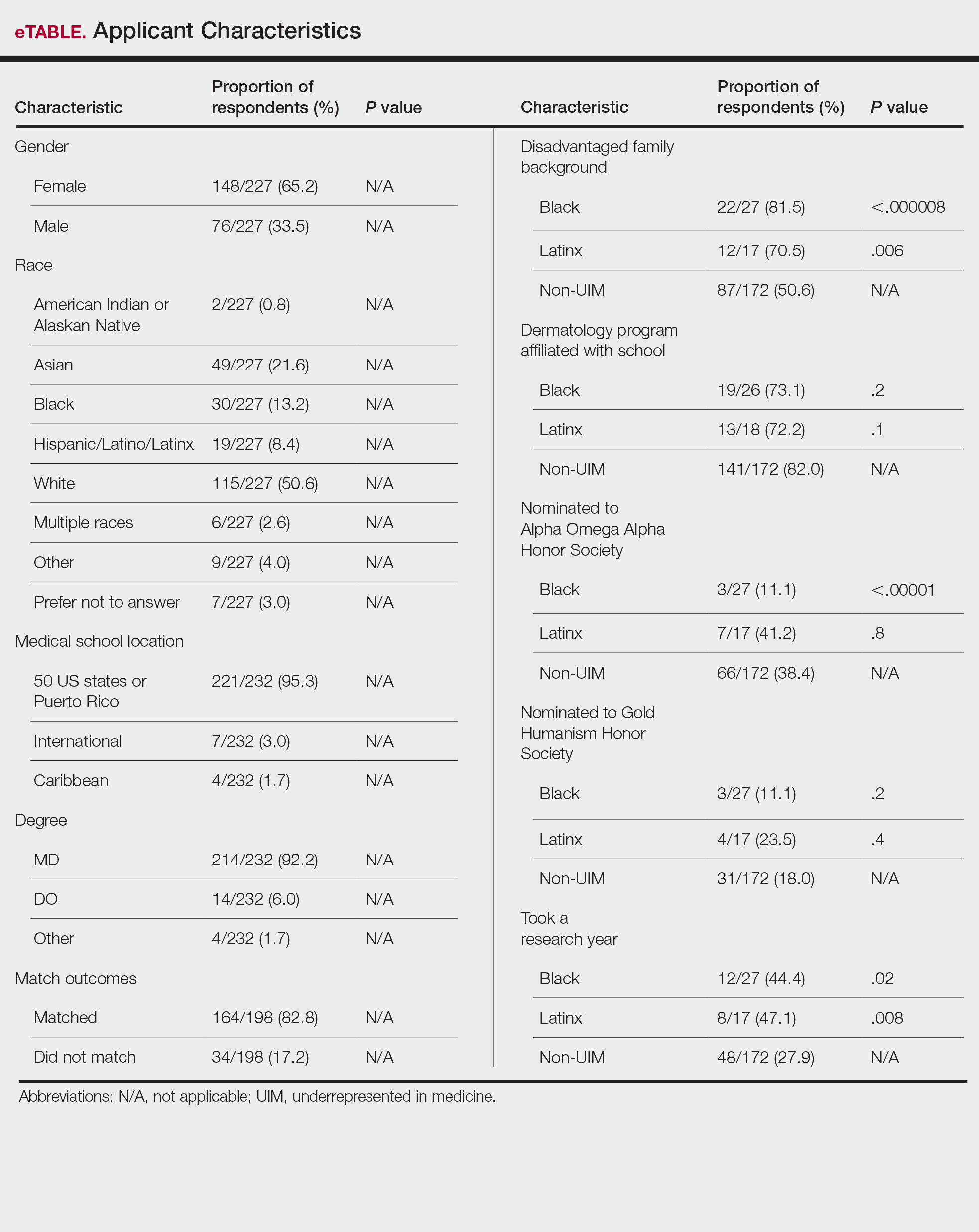

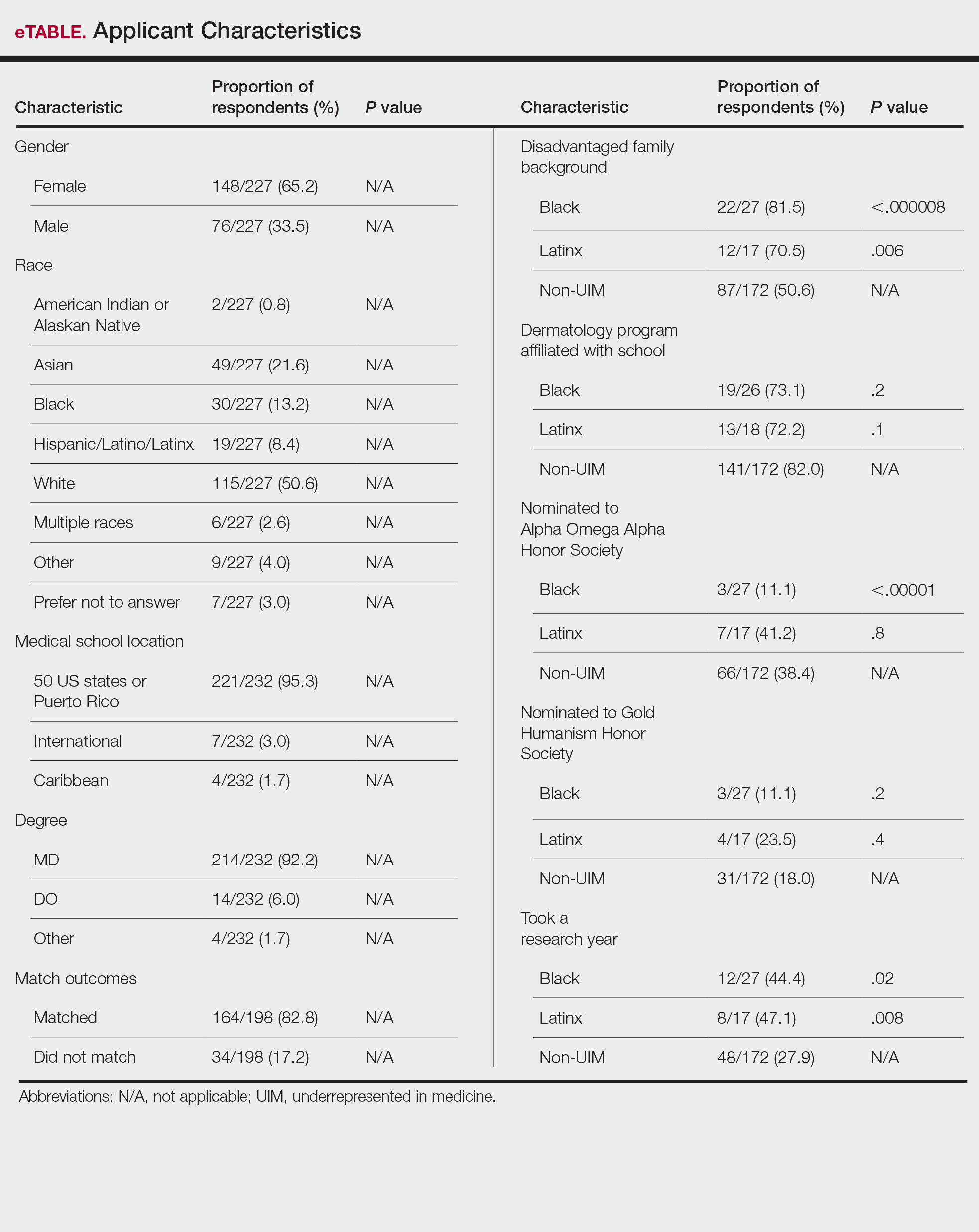

Applicant Characteristics—Applicant characteristics are provided in the eTable; 13.2% and 8.4% of participants were Black and Latinx (including those who identify as Hispanic/Latino), respectively. Only 0.8% of respondents identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native and were excluded from the analysis due to the limited sample size. Those who identified as White, Asian, multiple races, or other and those who preferred not to answer were considered non-UIM participants.

Differences in family background were observed in our cohort, with UIM candidates more likely to have experienced disadvantages, defined as being the first in their family to attend college/graduate school, growing up in a rural area, being a first-generation immigrant, or qualifying as low income. Underrepresented in medicine applicants also were less likely to have a dermatology program at their medical school (both Black and Latinx) and to have been elected to honor societies such as Alpha Omega Alpha and the Gold Humanism Honor Society (Black only).

Underrepresented in medicine applicants were more likely to complete a research gap year (eTable). Most applicants who took research years did so to improve their chances of matching, regardless of their race/ethnicity. For those who did not complete a research year, Black applicants (46.7%) were more likely to base that decision on financial limitations compared to non-UIMs (18.6%, P<.0001). Interestingly, in the PD survey, only 4.5% of respondents considered completion of a research year extremely or very important when compiling rank lists.

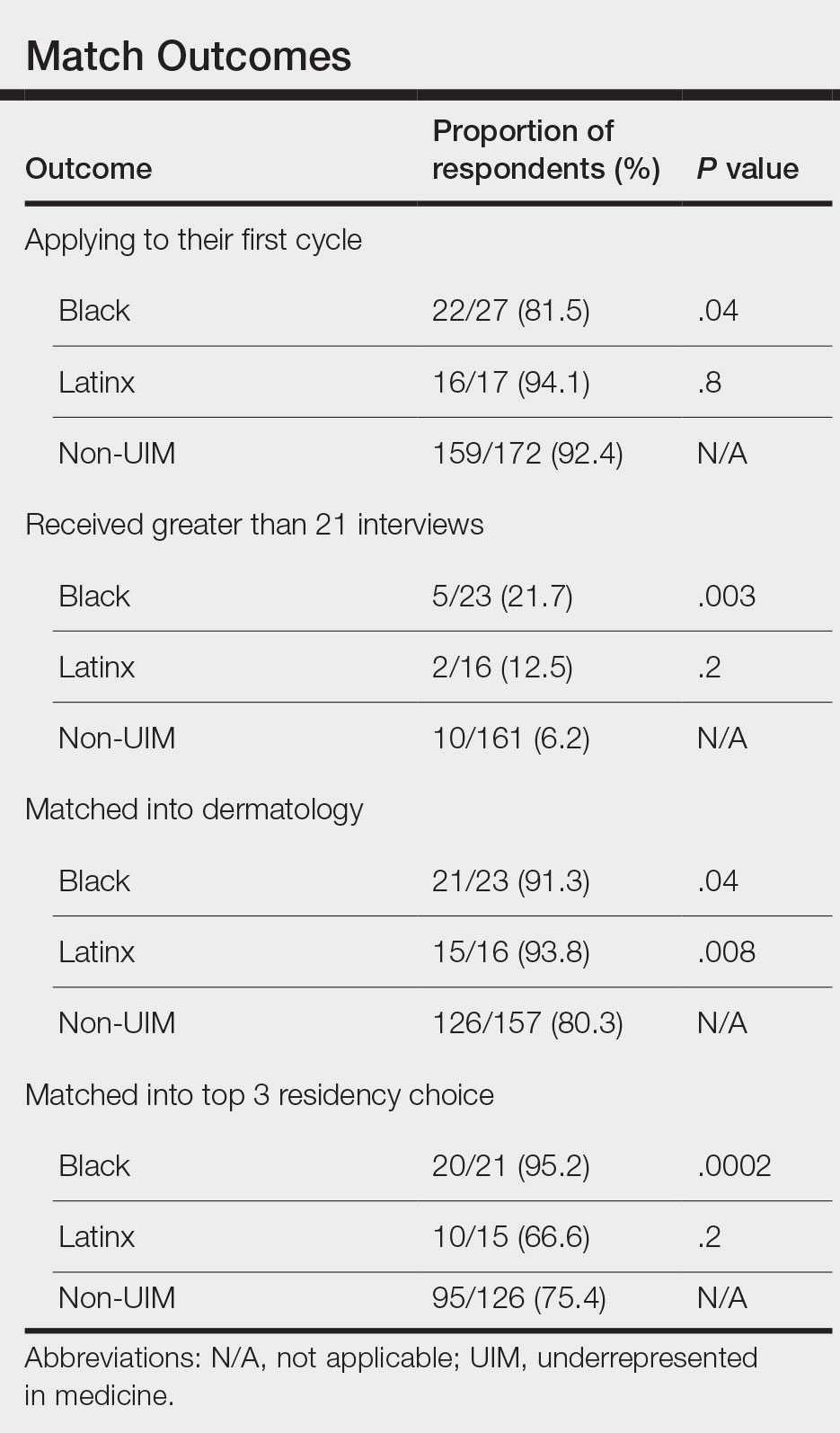

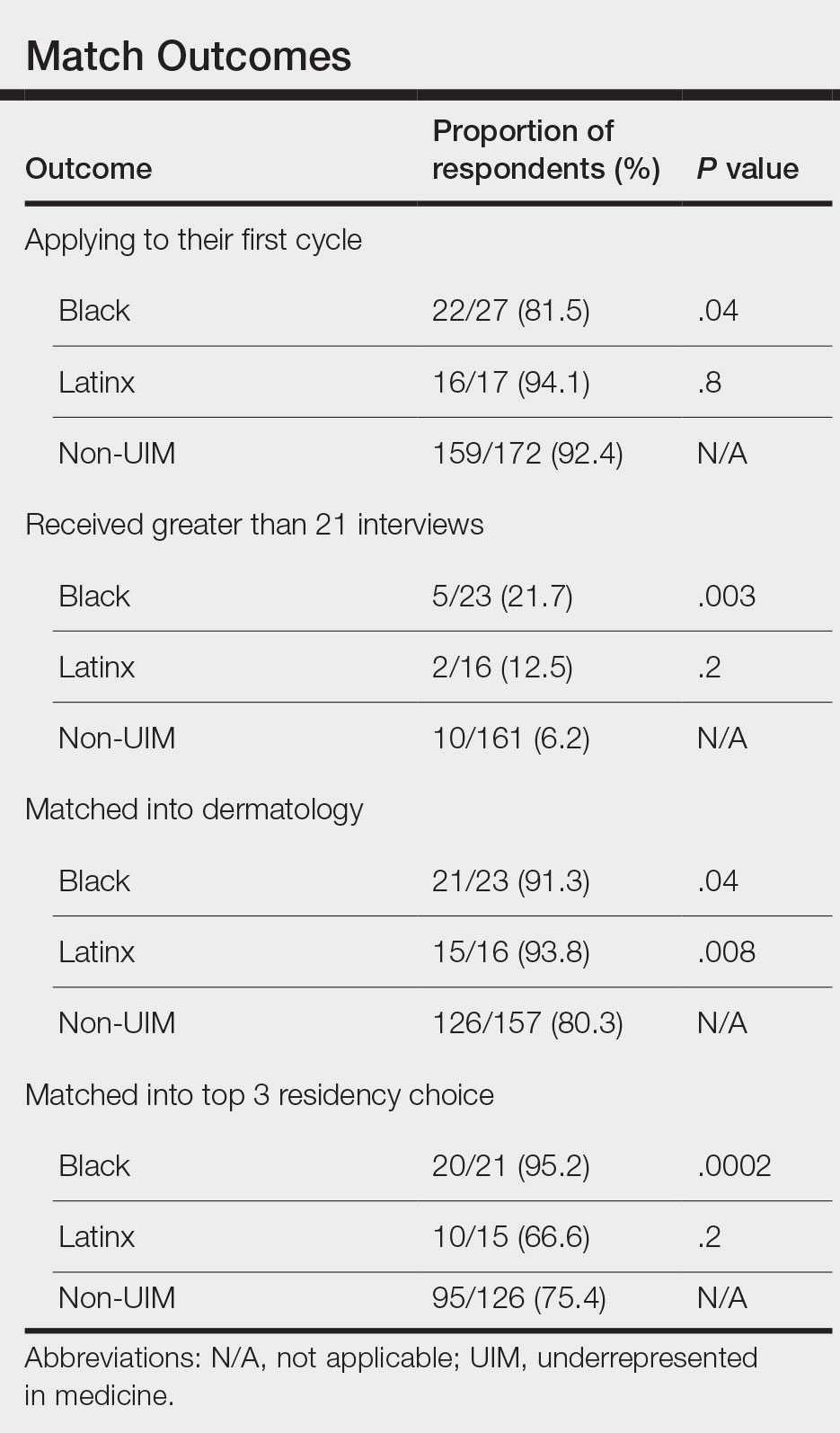

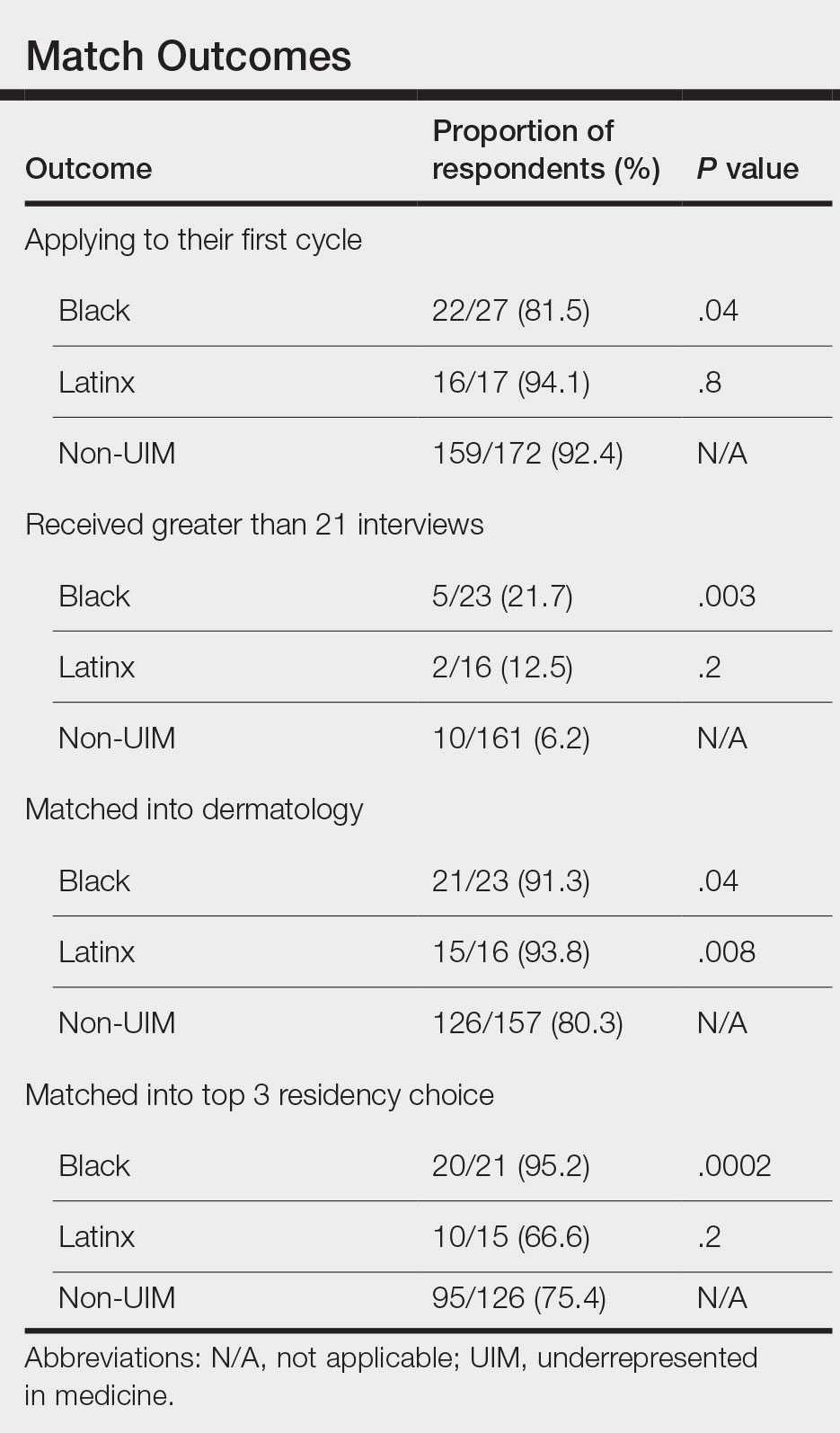

Application Process and Match Outcomes—The Table highlights differences in how UIM applicants approached the application process. Black but not Latinx applicants were less likely to be first-time applicants to dermatology compared to non-UIM applicants. Black applicants (8.3%) were significantly less likely to apply to more than 100 programs compared to non-UIM applicants (29.5%, P=.0002). Underrepresented in medicine applicants received greater numbers of interviews despite applying to fewer programs overall.

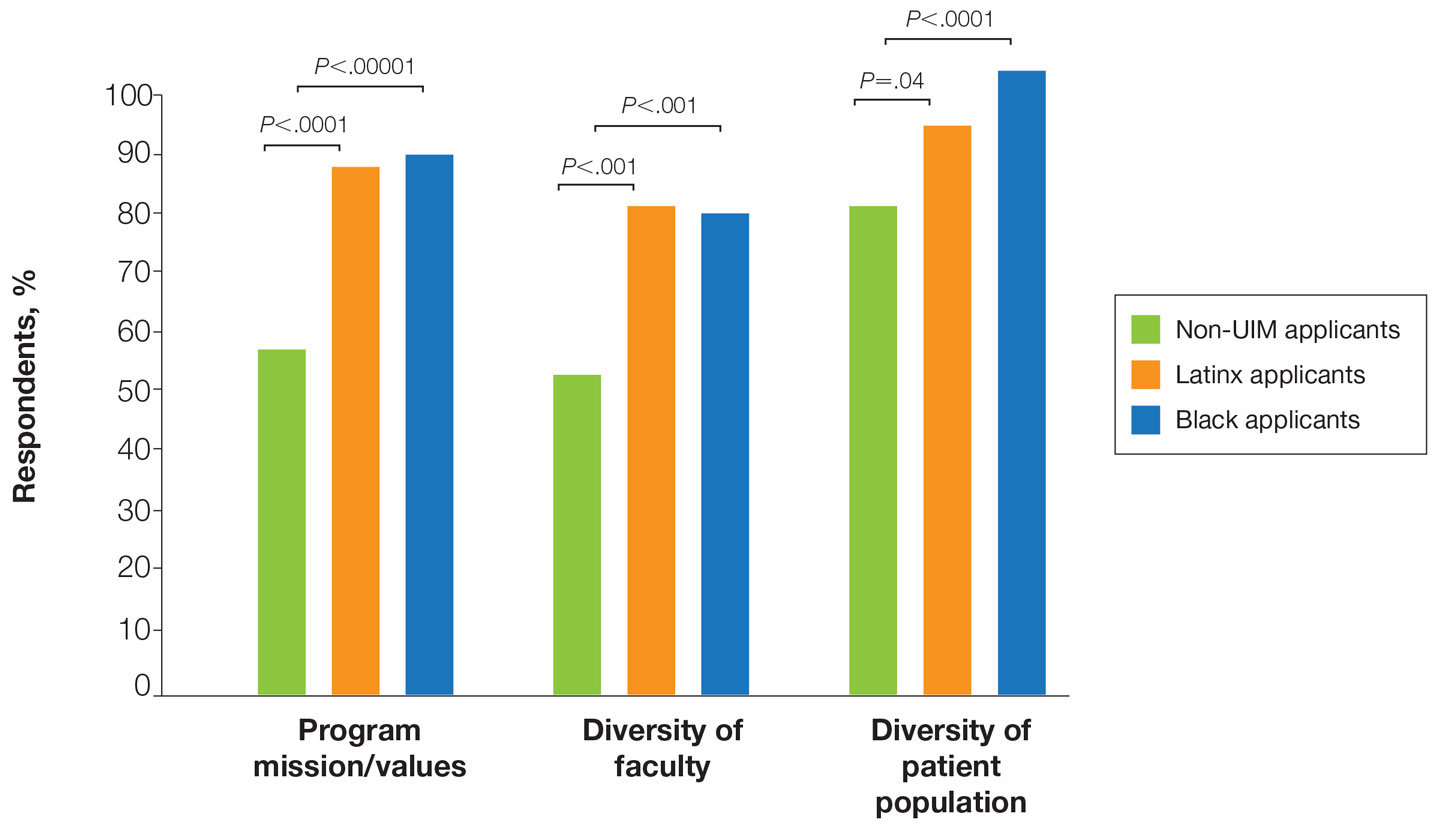

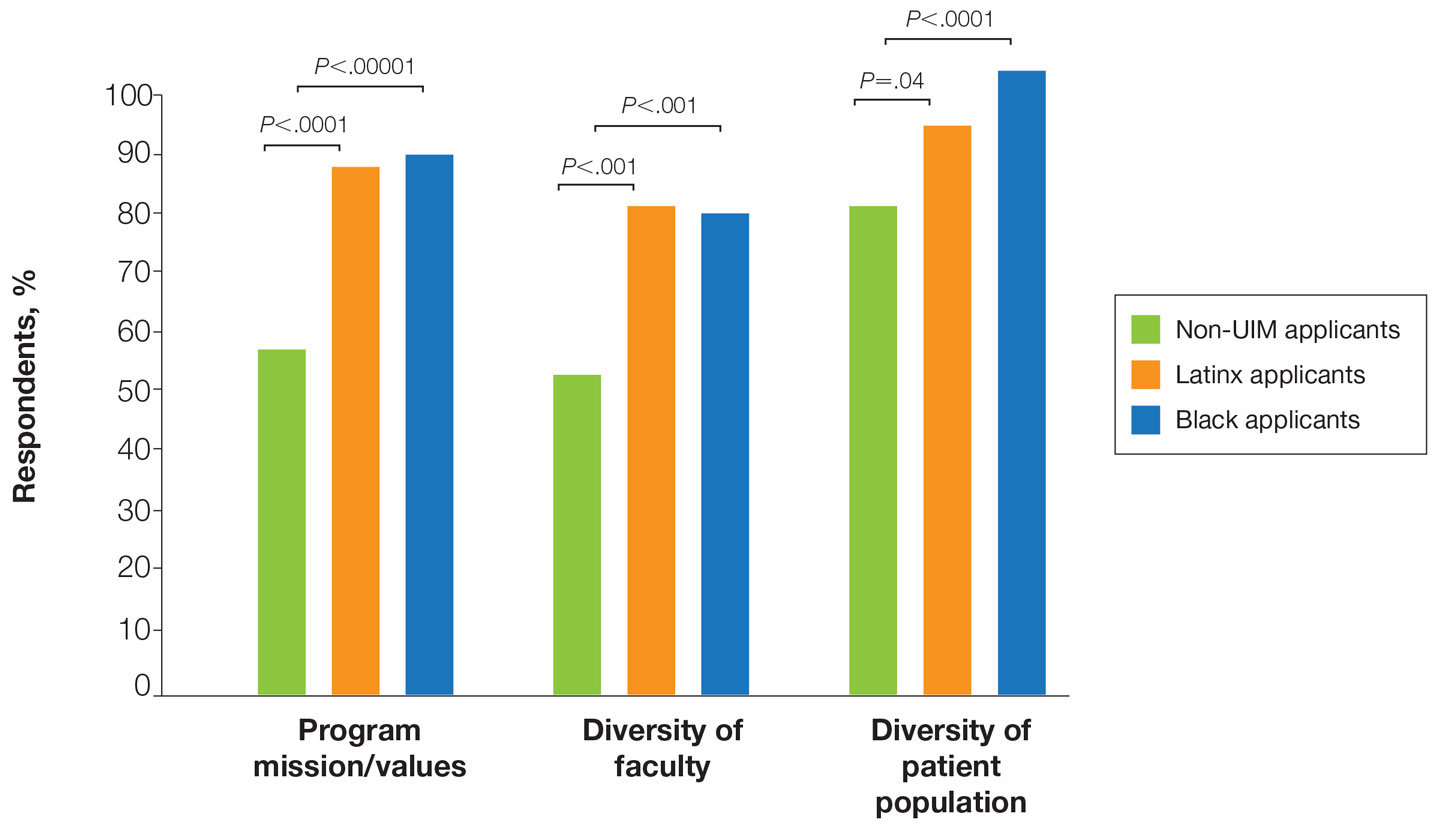

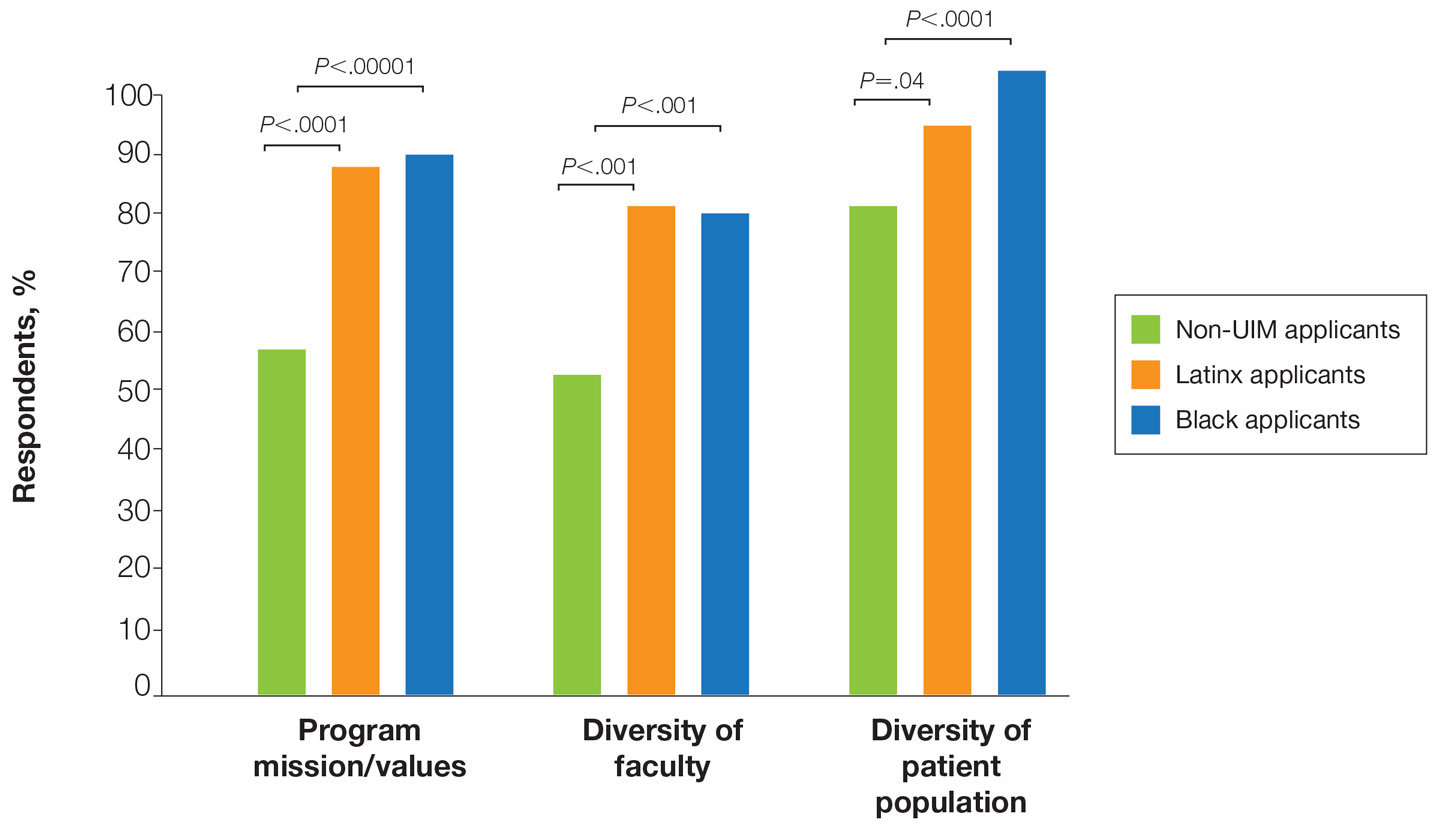

There also were differences in how UIM candidates approached their rank lists, with Black and Latinx applicants prioritizing diversity of patient populations and program faculty as well as program missions and values (Figure).

In our cohort, UIM candidates were more likely than non-UIM to match, and Black applicants were most likely to match at one of their top 3 choices (Table). In the PD survey, 77.6% of PDs considered contribution to diversity an important factor when compiling their rank lists.

Comment

Applicant Background—Dermatology is a competitive specialty with a challenging application process2 that has been further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study elucidated how the 2020-2021 application cycle affected UIM dermatology applicants. Prior studies have found that UIM medical students were more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds; financial constraints pose a major barrier for UIM and low-income students interested in dermatology.4-6 We found this to be true in our cohort, as Black and Latinx applicants were significantly more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds (P<.000008 and P=.006, respectively). Additionally, we found that Black applicants were more likely than any other group to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not taking a research gap year.

Although most applicants who completed a research year did so to increase their chances of matching, a higher percentage of UIMs took research years compared to non-UIM applicants. This finding could indicate greater anxiety about matching among UIM applicants vs their non-UIM counterparts. Black students have faced discrimination in clinical grading,7 have perceived racial discrimination in residency interviews,8,9 and have shown to be less likely to be elected to medical school honor societies.10 We found that UIM applicants were more likely to pursue a research year compared to other applicants,11 possibly because they felt additional pressure to enhance their applications or because UIM candidates were less likely to have a home dermatology program. Expansion of mentorship programs, visiting student electives, and grants for UIMs may alleviate the need for these candidates to complete a research year and reduce disparities in the application process.

Factors Influencing Rank Lists for Applicants—In our cohort, UIMs were significantly more likely to rank diversity of patients (P<.0001 for Black applicants and P=.04 for Latinx applicants) and faculty (P<.001 for Black applicants and P<.001 for Latinx applicants) as important factors in choosing a residency program. Historically, dermatology has been disproportionately White in its physician workforce and patient population.1,12 Students with lower incomes or who identify as minorities cite the lack of diversity in dermatology as a considerable barrier to pursuing a career in the specialty.4,5 Service learning, pipeline programs aimed at early exposure to dermatology, and increased access to care for diverse patient populations are important measures to improve diversity in the dermatology workforce.13-15 Residency programs should consider how to incorporate these aspects into didactic and clinical curricula to better recruit diverse candidates to the field.

Equity in the Application Process—We found that Black applicants were more likely than non-UIM applicants to be reapplicants to dermatology; however, Black applicants in our study also were more likely to receive more interview invites, match into dermatology, and match into one of their top 3 programs. These findings are interesting, particularly given concerns about equity in the application process. It is possible that Black applicants who overcome barriers to applying to dermatology ultimately are more successful applicants. Recently, there has been an increased focus in the field on diversifying dermatology, which was further intensified last year.2,3 Indicative of this shift, our PD survey showed that most programs reported that applicants’ contributions to diversity were important factors in the application process. Additionally, an emphasis by PDs on a holistic review of applications coupled with direct advocacy for increased representation may have contributed to the increased match rates for UIM applicants reported in our survey.

Latinx Applicants—Our study showed differences in how Latinx candidates fared in the application process; although Latinx applicants were more likely than their non-Latinx counterparts to match into dermatology, they were less likely than non-Latinx applicants to match into one of their top 3 programs. Given that Latinx encompasses ethnicity, not race, there may be a difference in how intentional focus on and advocacy for increasing diversity in dermatology affected different UIM applicant groups. Both race and ethnicity are social constructs rather than scientific categorizations; thus, it is difficult in survey studies such as ours to capture the intersectionality present across and between groups. Lastly, it is possible that the respondents to our applicant survey are not representative of the full cohort of UIM applicants.

Study Limitations—A major limitation of our study was that we did not have a method of reaching all dermatology applicants. Although our study shows promising results suggestive of increased diversity in the last application cycle, release of the National Resident Matching Program results from 2020-2021 with racially stratified data will be imperative to assess equity in the match process for all specialties and to confirm the generalizability of our results.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4683

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Diversity In Dermatology: Diversity Committee Approved Plan 2021-2023. Published January 26, 2021. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://assets.ctfassets.net/1ny4yoiyrqia/xQgnCE6ji5skUlcZQHS2b/65f0a9072811e11afcc33d043e02cd4d/DEI_Plan.pdf

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by under-represented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatologyresidency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Patel PM, et al. Considerations for dermatology residency applicants underrepresented in medicine amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E247.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.141

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Grbic D, Jones DJ, Case ST. The role of socioeconomic status in medical school admissions: validation of a socioeconomic indicator for use in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2015;90:953-960. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000653

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao ZC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Ellis J, Otugo O, Landry A, et al. Interviewed while Black [published online November 11, 2020]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2401-2404. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2023999

- Anthony Douglas II, Hendrix J. Black medical student considerations in the era of virtual interviews. Ann Surg. 2021;274:232-233. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004946

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623

- Runge M, Renati S, Helfrich Y. 16146 dermatology residency applicants: how many pursue a dedicated research year or dual-degree, and do their stats differ [published online December 1, 2020]? J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.304

- Stern RS. Dermatologists and office-based care of dermatologic disease in the 21st century. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:126-130. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09108.x

- Oyesanya T, Grossberg AL, Okoye GA. Increasing minority representation in the dermatology department: the Johns Hopkins experience. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1133-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2018

- Humphrey VS, James AJ. The importance of service learning in dermatology residency: an actionable approach to improve resident education and skin health equity. Cutis. 2021;107:120-122. doi:10.12788/cutis.0199

Dermatology is one of the least diverse medical specialties with only 3% of dermatologists being Black and 4% Latinx.1 Leading dermatology organizations have called for specialty-wide efforts to improve diversity, with a particular focus on the resident selection process.2,3 Medical students who are underrepresented in medicine (UIM)(ie, those who identify as Black, Latinx, Native American, or Pacific Islander) face many potential barriers in applying to dermatology programs, including financial limitations, lack of support and mentorship, and less exposure to the specialty.1,2,4 The COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges in the residency application process with limitations on clinical, research, and volunteer experiences; decreased opportunities for in-person mentorship and away rotations; and a shift to virtual recruitment. Although there has been increased emphasis on recruiting diverse candidates to dermatology, the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated existing barriers for UIM applicants.

We surveyed dermatology residency program directors (PDs) and applicants to evaluate how UIM students approach and fare in the dermatology residency application process as well as the effects of COVID-19 on the most recent application cycle. Herein, we report the results of our surveys with a focus on racial differences in the application process.

Methods

We administered 2 anonymous online surveys—one to 115 PDs through the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) email listserve and another to applicants who participated in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency application cycle through the Dermatology Interest Group Association (DIGA) listserve. The surveys were distributed from March 29 through May 23, 2021. There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants on the DIGA listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, California) institutional review board (approval #UP-21-00118).

Participants were not required to answer every survey question; response rates varied by question. Survey responses with less than 10% completion were excluded from analysis. Data were collected, analyzed, and stored using Qualtrics, a secure online survey platform. The test of equal or given proportions in R studio was used to determine statistically significant differences between variables (P<.05 indicated statistical significance).

Results

The PD survey received 79 complete responses (83.5% complete responses, 73.8% response rate) and the applicant survey received 232 complete responses (83.6% complete responses).

Applicant Characteristics—Applicant characteristics are provided in the eTable; 13.2% and 8.4% of participants were Black and Latinx (including those who identify as Hispanic/Latino), respectively. Only 0.8% of respondents identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native and were excluded from the analysis due to the limited sample size. Those who identified as White, Asian, multiple races, or other and those who preferred not to answer were considered non-UIM participants.

Differences in family background were observed in our cohort, with UIM candidates more likely to have experienced disadvantages, defined as being the first in their family to attend college/graduate school, growing up in a rural area, being a first-generation immigrant, or qualifying as low income. Underrepresented in medicine applicants also were less likely to have a dermatology program at their medical school (both Black and Latinx) and to have been elected to honor societies such as Alpha Omega Alpha and the Gold Humanism Honor Society (Black only).

Underrepresented in medicine applicants were more likely to complete a research gap year (eTable). Most applicants who took research years did so to improve their chances of matching, regardless of their race/ethnicity. For those who did not complete a research year, Black applicants (46.7%) were more likely to base that decision on financial limitations compared to non-UIMs (18.6%, P<.0001). Interestingly, in the PD survey, only 4.5% of respondents considered completion of a research year extremely or very important when compiling rank lists.

Application Process and Match Outcomes—The Table highlights differences in how UIM applicants approached the application process. Black but not Latinx applicants were less likely to be first-time applicants to dermatology compared to non-UIM applicants. Black applicants (8.3%) were significantly less likely to apply to more than 100 programs compared to non-UIM applicants (29.5%, P=.0002). Underrepresented in medicine applicants received greater numbers of interviews despite applying to fewer programs overall.

There also were differences in how UIM candidates approached their rank lists, with Black and Latinx applicants prioritizing diversity of patient populations and program faculty as well as program missions and values (Figure).

In our cohort, UIM candidates were more likely than non-UIM to match, and Black applicants were most likely to match at one of their top 3 choices (Table). In the PD survey, 77.6% of PDs considered contribution to diversity an important factor when compiling their rank lists.

Comment

Applicant Background—Dermatology is a competitive specialty with a challenging application process2 that has been further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study elucidated how the 2020-2021 application cycle affected UIM dermatology applicants. Prior studies have found that UIM medical students were more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds; financial constraints pose a major barrier for UIM and low-income students interested in dermatology.4-6 We found this to be true in our cohort, as Black and Latinx applicants were significantly more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds (P<.000008 and P=.006, respectively). Additionally, we found that Black applicants were more likely than any other group to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not taking a research gap year.

Although most applicants who completed a research year did so to increase their chances of matching, a higher percentage of UIMs took research years compared to non-UIM applicants. This finding could indicate greater anxiety about matching among UIM applicants vs their non-UIM counterparts. Black students have faced discrimination in clinical grading,7 have perceived racial discrimination in residency interviews,8,9 and have shown to be less likely to be elected to medical school honor societies.10 We found that UIM applicants were more likely to pursue a research year compared to other applicants,11 possibly because they felt additional pressure to enhance their applications or because UIM candidates were less likely to have a home dermatology program. Expansion of mentorship programs, visiting student electives, and grants for UIMs may alleviate the need for these candidates to complete a research year and reduce disparities in the application process.

Factors Influencing Rank Lists for Applicants—In our cohort, UIMs were significantly more likely to rank diversity of patients (P<.0001 for Black applicants and P=.04 for Latinx applicants) and faculty (P<.001 for Black applicants and P<.001 for Latinx applicants) as important factors in choosing a residency program. Historically, dermatology has been disproportionately White in its physician workforce and patient population.1,12 Students with lower incomes or who identify as minorities cite the lack of diversity in dermatology as a considerable barrier to pursuing a career in the specialty.4,5 Service learning, pipeline programs aimed at early exposure to dermatology, and increased access to care for diverse patient populations are important measures to improve diversity in the dermatology workforce.13-15 Residency programs should consider how to incorporate these aspects into didactic and clinical curricula to better recruit diverse candidates to the field.

Equity in the Application Process—We found that Black applicants were more likely than non-UIM applicants to be reapplicants to dermatology; however, Black applicants in our study also were more likely to receive more interview invites, match into dermatology, and match into one of their top 3 programs. These findings are interesting, particularly given concerns about equity in the application process. It is possible that Black applicants who overcome barriers to applying to dermatology ultimately are more successful applicants. Recently, there has been an increased focus in the field on diversifying dermatology, which was further intensified last year.2,3 Indicative of this shift, our PD survey showed that most programs reported that applicants’ contributions to diversity were important factors in the application process. Additionally, an emphasis by PDs on a holistic review of applications coupled with direct advocacy for increased representation may have contributed to the increased match rates for UIM applicants reported in our survey.

Latinx Applicants—Our study showed differences in how Latinx candidates fared in the application process; although Latinx applicants were more likely than their non-Latinx counterparts to match into dermatology, they were less likely than non-Latinx applicants to match into one of their top 3 programs. Given that Latinx encompasses ethnicity, not race, there may be a difference in how intentional focus on and advocacy for increasing diversity in dermatology affected different UIM applicant groups. Both race and ethnicity are social constructs rather than scientific categorizations; thus, it is difficult in survey studies such as ours to capture the intersectionality present across and between groups. Lastly, it is possible that the respondents to our applicant survey are not representative of the full cohort of UIM applicants.

Study Limitations—A major limitation of our study was that we did not have a method of reaching all dermatology applicants. Although our study shows promising results suggestive of increased diversity in the last application cycle, release of the National Resident Matching Program results from 2020-2021 with racially stratified data will be imperative to assess equity in the match process for all specialties and to confirm the generalizability of our results.

Dermatology is one of the least diverse medical specialties with only 3% of dermatologists being Black and 4% Latinx.1 Leading dermatology organizations have called for specialty-wide efforts to improve diversity, with a particular focus on the resident selection process.2,3 Medical students who are underrepresented in medicine (UIM)(ie, those who identify as Black, Latinx, Native American, or Pacific Islander) face many potential barriers in applying to dermatology programs, including financial limitations, lack of support and mentorship, and less exposure to the specialty.1,2,4 The COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges in the residency application process with limitations on clinical, research, and volunteer experiences; decreased opportunities for in-person mentorship and away rotations; and a shift to virtual recruitment. Although there has been increased emphasis on recruiting diverse candidates to dermatology, the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated existing barriers for UIM applicants.

We surveyed dermatology residency program directors (PDs) and applicants to evaluate how UIM students approach and fare in the dermatology residency application process as well as the effects of COVID-19 on the most recent application cycle. Herein, we report the results of our surveys with a focus on racial differences in the application process.

Methods

We administered 2 anonymous online surveys—one to 115 PDs through the Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) email listserve and another to applicants who participated in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency application cycle through the Dermatology Interest Group Association (DIGA) listserve. The surveys were distributed from March 29 through May 23, 2021. There was no way to determine the number of dermatology applicants on the DIGA listserve. The surveys were reviewed and approved by the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, California) institutional review board (approval #UP-21-00118).

Participants were not required to answer every survey question; response rates varied by question. Survey responses with less than 10% completion were excluded from analysis. Data were collected, analyzed, and stored using Qualtrics, a secure online survey platform. The test of equal or given proportions in R studio was used to determine statistically significant differences between variables (P<.05 indicated statistical significance).

Results

The PD survey received 79 complete responses (83.5% complete responses, 73.8% response rate) and the applicant survey received 232 complete responses (83.6% complete responses).

Applicant Characteristics—Applicant characteristics are provided in the eTable; 13.2% and 8.4% of participants were Black and Latinx (including those who identify as Hispanic/Latino), respectively. Only 0.8% of respondents identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native and were excluded from the analysis due to the limited sample size. Those who identified as White, Asian, multiple races, or other and those who preferred not to answer were considered non-UIM participants.

Differences in family background were observed in our cohort, with UIM candidates more likely to have experienced disadvantages, defined as being the first in their family to attend college/graduate school, growing up in a rural area, being a first-generation immigrant, or qualifying as low income. Underrepresented in medicine applicants also were less likely to have a dermatology program at their medical school (both Black and Latinx) and to have been elected to honor societies such as Alpha Omega Alpha and the Gold Humanism Honor Society (Black only).

Underrepresented in medicine applicants were more likely to complete a research gap year (eTable). Most applicants who took research years did so to improve their chances of matching, regardless of their race/ethnicity. For those who did not complete a research year, Black applicants (46.7%) were more likely to base that decision on financial limitations compared to non-UIMs (18.6%, P<.0001). Interestingly, in the PD survey, only 4.5% of respondents considered completion of a research year extremely or very important when compiling rank lists.

Application Process and Match Outcomes—The Table highlights differences in how UIM applicants approached the application process. Black but not Latinx applicants were less likely to be first-time applicants to dermatology compared to non-UIM applicants. Black applicants (8.3%) were significantly less likely to apply to more than 100 programs compared to non-UIM applicants (29.5%, P=.0002). Underrepresented in medicine applicants received greater numbers of interviews despite applying to fewer programs overall.

There also were differences in how UIM candidates approached their rank lists, with Black and Latinx applicants prioritizing diversity of patient populations and program faculty as well as program missions and values (Figure).

In our cohort, UIM candidates were more likely than non-UIM to match, and Black applicants were most likely to match at one of their top 3 choices (Table). In the PD survey, 77.6% of PDs considered contribution to diversity an important factor when compiling their rank lists.

Comment

Applicant Background—Dermatology is a competitive specialty with a challenging application process2 that has been further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study elucidated how the 2020-2021 application cycle affected UIM dermatology applicants. Prior studies have found that UIM medical students were more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds; financial constraints pose a major barrier for UIM and low-income students interested in dermatology.4-6 We found this to be true in our cohort, as Black and Latinx applicants were significantly more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds (P<.000008 and P=.006, respectively). Additionally, we found that Black applicants were more likely than any other group to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not taking a research gap year.

Although most applicants who completed a research year did so to increase their chances of matching, a higher percentage of UIMs took research years compared to non-UIM applicants. This finding could indicate greater anxiety about matching among UIM applicants vs their non-UIM counterparts. Black students have faced discrimination in clinical grading,7 have perceived racial discrimination in residency interviews,8,9 and have shown to be less likely to be elected to medical school honor societies.10 We found that UIM applicants were more likely to pursue a research year compared to other applicants,11 possibly because they felt additional pressure to enhance their applications or because UIM candidates were less likely to have a home dermatology program. Expansion of mentorship programs, visiting student electives, and grants for UIMs may alleviate the need for these candidates to complete a research year and reduce disparities in the application process.

Factors Influencing Rank Lists for Applicants—In our cohort, UIMs were significantly more likely to rank diversity of patients (P<.0001 for Black applicants and P=.04 for Latinx applicants) and faculty (P<.001 for Black applicants and P<.001 for Latinx applicants) as important factors in choosing a residency program. Historically, dermatology has been disproportionately White in its physician workforce and patient population.1,12 Students with lower incomes or who identify as minorities cite the lack of diversity in dermatology as a considerable barrier to pursuing a career in the specialty.4,5 Service learning, pipeline programs aimed at early exposure to dermatology, and increased access to care for diverse patient populations are important measures to improve diversity in the dermatology workforce.13-15 Residency programs should consider how to incorporate these aspects into didactic and clinical curricula to better recruit diverse candidates to the field.

Equity in the Application Process—We found that Black applicants were more likely than non-UIM applicants to be reapplicants to dermatology; however, Black applicants in our study also were more likely to receive more interview invites, match into dermatology, and match into one of their top 3 programs. These findings are interesting, particularly given concerns about equity in the application process. It is possible that Black applicants who overcome barriers to applying to dermatology ultimately are more successful applicants. Recently, there has been an increased focus in the field on diversifying dermatology, which was further intensified last year.2,3 Indicative of this shift, our PD survey showed that most programs reported that applicants’ contributions to diversity were important factors in the application process. Additionally, an emphasis by PDs on a holistic review of applications coupled with direct advocacy for increased representation may have contributed to the increased match rates for UIM applicants reported in our survey.

Latinx Applicants—Our study showed differences in how Latinx candidates fared in the application process; although Latinx applicants were more likely than their non-Latinx counterparts to match into dermatology, they were less likely than non-Latinx applicants to match into one of their top 3 programs. Given that Latinx encompasses ethnicity, not race, there may be a difference in how intentional focus on and advocacy for increasing diversity in dermatology affected different UIM applicant groups. Both race and ethnicity are social constructs rather than scientific categorizations; thus, it is difficult in survey studies such as ours to capture the intersectionality present across and between groups. Lastly, it is possible that the respondents to our applicant survey are not representative of the full cohort of UIM applicants.

Study Limitations—A major limitation of our study was that we did not have a method of reaching all dermatology applicants. Although our study shows promising results suggestive of increased diversity in the last application cycle, release of the National Resident Matching Program results from 2020-2021 with racially stratified data will be imperative to assess equity in the match process for all specialties and to confirm the generalizability of our results.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4683

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Diversity In Dermatology: Diversity Committee Approved Plan 2021-2023. Published January 26, 2021. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://assets.ctfassets.net/1ny4yoiyrqia/xQgnCE6ji5skUlcZQHS2b/65f0a9072811e11afcc33d043e02cd4d/DEI_Plan.pdf

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by under-represented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatologyresidency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Patel PM, et al. Considerations for dermatology residency applicants underrepresented in medicine amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E247.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.141

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Grbic D, Jones DJ, Case ST. The role of socioeconomic status in medical school admissions: validation of a socioeconomic indicator for use in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2015;90:953-960. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000653

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao ZC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Ellis J, Otugo O, Landry A, et al. Interviewed while Black [published online November 11, 2020]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2401-2404. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2023999

- Anthony Douglas II, Hendrix J. Black medical student considerations in the era of virtual interviews. Ann Surg. 2021;274:232-233. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004946

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623

- Runge M, Renati S, Helfrich Y. 16146 dermatology residency applicants: how many pursue a dedicated research year or dual-degree, and do their stats differ [published online December 1, 2020]? J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.304

- Stern RS. Dermatologists and office-based care of dermatologic disease in the 21st century. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:126-130. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09108.x

- Oyesanya T, Grossberg AL, Okoye GA. Increasing minority representation in the dermatology department: the Johns Hopkins experience. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1133-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2018

- Humphrey VS, James AJ. The importance of service learning in dermatology residency: an actionable approach to improve resident education and skin health equity. Cutis. 2021;107:120-122. doi:10.12788/cutis.0199

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4683

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Diversity In Dermatology: Diversity Committee Approved Plan 2021-2023. Published January 26, 2021. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://assets.ctfassets.net/1ny4yoiyrqia/xQgnCE6ji5skUlcZQHS2b/65f0a9072811e11afcc33d043e02cd4d/DEI_Plan.pdf

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by under-represented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatologyresidency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Jones VA, Clark KA, Patel PM, et al. Considerations for dermatology residency applicants underrepresented in medicine amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E247.doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.141

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Grbic D, Jones DJ, Case ST. The role of socioeconomic status in medical school admissions: validation of a socioeconomic indicator for use in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2015;90:953-960. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000653

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao ZC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31:487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Ellis J, Otugo O, Landry A, et al. Interviewed while Black [published online November 11, 2020]. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2401-2404. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2023999

- Anthony Douglas II, Hendrix J. Black medical student considerations in the era of virtual interviews. Ann Surg. 2021;274:232-233. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000004946

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9623

- Runge M, Renati S, Helfrich Y. 16146 dermatology residency applicants: how many pursue a dedicated research year or dual-degree, and do their stats differ [published online December 1, 2020]? J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.304

- Stern RS. Dermatologists and office-based care of dermatologic disease in the 21st century. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:126-130. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09108.x

- Oyesanya T, Grossberg AL, Okoye GA. Increasing minority representation in the dermatology department: the Johns Hopkins experience. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1133-1134. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2018

- Humphrey VS, James AJ. The importance of service learning in dermatology residency: an actionable approach to improve resident education and skin health equity. Cutis. 2021;107:120-122. doi:10.12788/cutis.0199

Practice Points

- Underrepresented in medicine (UIM) dermatology residency applicants (Black and Latinx) are more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds and to have financial concerns about the residency application process.

- When choosing a dermatology residency program, diversity of patients and faculty are more important to UIM dermatology residency applicants than to their non-UIM counterparts.

- Increased awareness of and focus on a holistic review process by dermatology residency programs may contribute to higher rates of matching among Black applicants in our study.

The Residency Application Process: Current and Future Landscape

Amid increasing numbers of applications, decreasing match rates, and ongoing lack of diversity in the dermatology trainee workforce, the COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges to the dermatology residency application process and laid bare systemic inequities and inherent problems that must be addressed. Historically, dermatology applicants have excelled in academic metrics, such as US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) scores and nomination to the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. As biases associated with these academic metrics are being elucidated, they have in turn become less available. With the upcoming change in USMLE Step 1 reporting to pass/fail only, as well as the elimination of Alpha Omega Alpha nomination for students, clinical grades, and/or class ranks at many medical schools, other elements of the application, such as volunteer experiences and research publications, may be weighed more heavily in the selection process. This may serve to exacerbate the application arms race, characterized by a steady rise in volunteer experiences, research publications, and research gap years that has already begun and likely will continue, particularly among dermatology applicants.

These issues are not unique to dermatology and are occurring across all medical specialties to varying degrees. The monetary and opportunity costs of the application process have become astronomical for both applicants and faculty. Faculty are overburdened with administrative duties related to resident recruitment and advising, and students are experiencing heightened match-related anxiety earlier and more acutely. These factors may contribute to burnout among trainees and faculty and may have deleterious effects on medical education. It is clear that transformative work must be pursued to ensure an equitable and sustainable residency application process moving forward. In this column, we review the notable work being done within dermatology and across specialties to reform the residency application process.

Coalition Recommendations

In August 2021, the Coalition for Physician Accountability (CoPA) released recommendations for comprehensive improvement of the undergraduate medical education (UME) to graduate medical education transition, which includes residency application. Of the 9 principal themes addressed, 2 focus on the residency application process: (1) equitable mission-driven application review, and (2) optimization of the application, interview, and selection processes, which relates to application volume as well as interview offers and formats.1

In the area of application review, CoPA recommends replacing all letters of recommendation with structured evaluative letters as a universal tool in the application process.1 These letters would include specialty-specific questions based on core competencies and would be completed by an evaluator who directly observed the student. Additionally, the group recommends revising the content and structure of the medical student performance evaluation to improve access to longitudinal assessment data about students. Ideally, developing UME competency outcomes to apply across learners would decrease reliance on traditional but potentially problematic application elements, such as licensing examination scores, clinical grades, and narrative evaluations.1

To optimize residency application processes, CoPA recommends exploring innovative approaches to reduce application volume and maximize applicants interviewing and matching at programs where mutual interest is high.1 Suggestions to address these issues include preference signaling, application caps, and/or additional rounds of application or matching. Standardization of the interview process also is recommended to improve equity, minimize educational disruption, and improve applicant well-being. Suggestions include the use of common interview offer and scheduling platforms, policies to govern interview offers and scheduling timelines, interview caps, and ongoing study of the impact of virtual interviews.1

Residency Application Innovations Implemented by Other Specialties

A number of specialties have developed innovations in the residency application process to improve equity and fairness as well as optimize applicant-program fit. Emergency medicine created a now widely adopted, specialty-specific standardized letter of evaluation (SLOE).2 It compares applicants across a number of measures that include personal qualities, clinical skills, and a global assessment. The SLOE is designed to assess and compare applicants across institutions rather than provide recommendations. The emergency medicine SLOE also provides useful information about the letter writer, including duration and depth of interaction with the applicant and distribution of rankings of prior applicants.2

In 2019, obstetrics and gynecology launched a standardized application and interview process, which set a specialty-wide application deadline, limited interview invitations to the number of interview positions available, encouraged coordinated release of interview offers, and allowed applicants 72 hours to respond to invitations.3 These measures were implemented to improve fairness, transparency, and applicant well-being, as well as to promote equitable distribution of interviews. Data following this launch suggested that universal offer dates reduced excessive interviewing among competitive applicants.3

Last year, otolaryngology implemented a process known as preference signaling in which applicants were able to signal up to 5 preferred programs at the time of application. A signal allowed applicants to demonstrate interest in specific programs and could be used by programs during their application review process. Most applicants opted to submit signals, and programs received 0 to 71 signals (mean, 22).4 Almost all programs received at least 1 signal. The rate of receiving an interview was significantly higher for signaled programs (58%) compared to nonsignaled programs (14%)(P<.001), indicating that preference signaling may be beneficial for both programs and applicants for interview selection.4

Residency Application Innovations Implemented by Dermatology

Over the last 2 application cycles, dermatology has implemented several innovations to the residency application process. Initial work included release of guidelines for residency programs to conduct holistic application review,5 recommendations for website updates to share program-specific information with prospective trainees,6 and informational webinars and statements to update dermatology applicants about changes to the process and to answer application-related questions.7-9

In 2020, dermatology initiated a coordinated interview invitation release in which interview offers were released on prespecified dates and applicants were given 48 hours prior to scheduling. Approximately 50% of residency programs participated in the first year, yet nearly all programs released on 1 of 2 universal dates in the current cycle. In a recent survey of dermatology applicants, nearly 90% supported coordinated release.10 Several other specialties also have incorporated universal release dates into their processes.

For the 2021-2022 application cycle, dermatology—along with internal medicine and general surgery—participated in the Association of American Medical Colleges’ pilot supplemental Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) application.11 The pilot was designed as a first step to updating the ERAS content by allowing students to share more information about their extracurricular, research, and clinical activities, as well as geographic and program preferences to optimize applicant-program fit. Preference signaling, similar to the otolaryngology process, was included in the supplemental application, with dermatology applicants choosing up to 3 preferred programs to signal, excluding their home programs and any programs where they completed in-person away rotations. Preliminary data suggest that the vast majority of dermatology programs and applicants participated in the supplemental application.12 Ongoing analysis of survey data from applicants, advisors, and program directors will help inform future directions. Dermatology has been an integral partner in the development, implementation, and evaluation of this pilot.

Proposed Innovations to the Application Process

Given the challenges of the current application process, there has been a long list of proposed innovations to ameliorate applicant, advisor, and program concerns.13 Many of these approaches are intended to respond to increasing costs to programs and applicants as well as the lack of equity in the process. Application caps and an early result acceptance program have both been proposed to address the ever-increasing volume of applications.14,15 Neither of these proposals has been adopted by a specialty yet, but obstetrics and gynecology stakeholders have shown broad support for an early result acceptance program, signaling a possible future pilot.16

Interview caps also have been proposed to promote more equitable distribution of interview positions.17 Ophthalmology implemented this approach in the 2021-2022 application cycle, with applicants limited to a maximum of 18 interviews.18 Data from this pilot will help determine the effect of interview caps as well as the optimal limit, which will vary by specialty.

Changes to the application content itself could better facilitate holistic review and optimize applicant-program fit. This is the principle driving the pilot supplemental ERAS application, but it also has been addressed in other specialties. Ophthalmology replaced the traditional personal statement with a shorter autobiographical statement as well as 2 short personal essay questions. Plastic surgery designed a common supplemental application, currently in its second iteration, that highlights specialty-specific information from applicants to promote holistic review and eventually reduce application costs.19

Final Thoughts

The reforms introduced and proposed by dermatology and other specialties represent initial steps to address the issues inherent to the current residency application process. Providing faculty with better tools to holistically assess applicants during the review process and increasing transparency between programs and applicants should help optimize applicant-program fit and increase diversity in the dermatology workforce. Streamlining the application process to allow students to highlight their unique qualities in a user-friendly format as well as addressing potential inequities in interview distribution and access to the application process hopefully will contribute to better outcomes for both programs and applicants. However, many of these steps are likely to create additional administrative burdens on program faculty and are unlikely to allay student fears about matching.

The underlying issue for many specialties, and particularly for dermatology, is that demand far outstrips supply. With stable numbers of residency positions and an ever-increasing number of applicants, the match rate will continue to decrease, leading to increased anxiety among those interested in pursuing dermatology. Although USMLE Step 1 scores have been shown to have racial bias20 and there are no data correlating scores with clinical performance, the elimination of a scoring system may affect the number of applicants entering dermatology with downstream effects on match rates. Heightened anxiety places increased pressure on students to choose a specialty earlier in their training and impacts the activities they pursue during medical school. Overemphasis on specialty choice and the match process can lead to higher rates of burnout among students and trainees, as students may focus on activities designed to increase their chances of matching at the expense of pursuing activities that could lead to greater engagement and passion in their careers—a key protective factor against burnout.

The goal of the residency application process is to optimize fit between candidates and programs by aligning goals, values, and learning environment. Students and programs working together as honest brokers can lead to transformative change in the process, freeing both parties to highlight their unique qualities and contributions. Programs benefit from optimal fit by being able to hone their particular mission and recruit and retain residents and faculty engaged in that mission. Residents will thrive in programs that support their learning and career goals and will ultimately be better positioned to meaningfully contribute to their chosen field in whatever capacity they choose.

Acknowledgments—The views presented in this column reflect those of the 9 elected members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology Residency Program Directors Section steering committee, all of whom are program directors at their institutions (listed in parentheses): Ammar Ahmed, MD (The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas); Yolanda Helfrich, MD (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan); Jo-Ann M. Latkowksi, MD (New York University, New York); Kiran Motaparthi, MD (University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida); Adena E. Rosenblatt, MD, PhD (The University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois); Ilana S. Rosman, MD (Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri); Travis Vandergriff, MD (University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, Texas); Diane Whitaker-Worth, MD (University of Connecticut, Farmington, Connecticut); Scott Worswick, MD (University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California).

- Coalition for Physician Accountability. The Coalition for Physician Accountability’s Undergraduate Medical Education–Graduate Medical Education Review Committee (UGRC): recommendations for comprehensive improvement of the UME-GME transition. Accessed March 7, 2022. https://physicianaccountability.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/UGRC-Coalition-Report-FINAL.pdf

- Jackson JS, Bond M, Love JN, et al. Emergency medicine standardized letter of evaluation (SLOE): findings from the new electronic SLOE format. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11:182-186.

- Santos-Parker KS, Morgan HK, Katz NT, et al. Can standardized dates for interview offers mitigate excessive interviewing? J Surg Educ. 2021;78:1091-1096.

- Pletcher SD, Chang CWD, Thorne MC, et al. The otolaryngology residency program preference signaling experience [published online October 5, 2021]. Acad Med. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004441

- Association of Professors of Dermatology. Holistic review. Accessed March 7, 2022. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/3_Holistic%20review_Oct2020.pdf

- Rosmarin D, Friedman AJ, Burkemper NM, et al. The Association of Professors of Dermatology Program Directors Task Force and Residency Program Transparency Work Group guidelines on residency program transparency. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:1117-1118.

- Rosman IS, Schadt CR, Samimi SS, et al. Approaching the dermatology residency application process during a pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E351-E352.

- Association of Professors of Dermatology. Program director resources. Accessed March 7, 2022. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/programdirectors_resources.php

- Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, Wu AG, et al. A national webinar for dermatology applicants during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:574-575.

- Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, Rinderknecht FA, et al. Current perspectives of and potential reforms to the dermatology residency application process: a nationwide survey of program directors and applicants. Clin Dermatol. In press.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Supplemental ERAS application (for the ERAS 2022 cycle). Accessed March 7, 2022. https://students-residents.aamc.org/applying-residencies-eras/supplementalerasapplication

- Association of American Medical Colleges. AAMC supplemental ERAS application: key findings from the 2022 application cycle. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/media/58891/download

- Warm EJ, Kinnear B, Pereira A, et al. The residency match: escaping the prisoner’s dilemma. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13:616-625.

- Carmody JB, Rosman IS, Carlson JC. Application fever: reviewing the causes, costs, and cures for residency application inflation. Cureus. 2021;13:E13804.

- Hammoud MM, Andrews J, Skochelak SE. Improving the residency application and selection process: an optional early result acceptance program. JAMA. 2020;323:503-504.

- Winkel AF, Morgan HK, Akingbola O, et al. Perspectives of stakeholders about an early release acceptance program to complement the residency match in obstetrics and gynecology. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:E2124158.

- Morgan HK, Winkel AF, Standiford T, et al. The case for capping residency interviews. J Surg Educ. 2021;78:755-762.

- Association of University Professors of Ophthalmology. 2021-22 ophthalmology residency match FAQs. Accessed March 7, 2022. https://aupo.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/Residency%20Match%20FAQs_2021.pdf

- American Council of Academic Plastic Surgeons. Applying to plastic surgery (PSCA). Accessed March 7, 2022. https://acaplasticsurgeons.org/PSCA/

- Rubright JD, Jodoin M, Barone MA. Examining demographics, prior academic performance, and United States Medical Licensing Examination Scores. Acad Med. 2019;94:364-370.

Amid increasing numbers of applications, decreasing match rates, and ongoing lack of diversity in the dermatology trainee workforce, the COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges to the dermatology residency application process and laid bare systemic inequities and inherent problems that must be addressed. Historically, dermatology applicants have excelled in academic metrics, such as US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) scores and nomination to the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. As biases associated with these academic metrics are being elucidated, they have in turn become less available. With the upcoming change in USMLE Step 1 reporting to pass/fail only, as well as the elimination of Alpha Omega Alpha nomination for students, clinical grades, and/or class ranks at many medical schools, other elements of the application, such as volunteer experiences and research publications, may be weighed more heavily in the selection process. This may serve to exacerbate the application arms race, characterized by a steady rise in volunteer experiences, research publications, and research gap years that has already begun and likely will continue, particularly among dermatology applicants.

These issues are not unique to dermatology and are occurring across all medical specialties to varying degrees. The monetary and opportunity costs of the application process have become astronomical for both applicants and faculty. Faculty are overburdened with administrative duties related to resident recruitment and advising, and students are experiencing heightened match-related anxiety earlier and more acutely. These factors may contribute to burnout among trainees and faculty and may have deleterious effects on medical education. It is clear that transformative work must be pursued to ensure an equitable and sustainable residency application process moving forward. In this column, we review the notable work being done within dermatology and across specialties to reform the residency application process.

Coalition Recommendations

In August 2021, the Coalition for Physician Accountability (CoPA) released recommendations for comprehensive improvement of the undergraduate medical education (UME) to graduate medical education transition, which includes residency application. Of the 9 principal themes addressed, 2 focus on the residency application process: (1) equitable mission-driven application review, and (2) optimization of the application, interview, and selection processes, which relates to application volume as well as interview offers and formats.1

In the area of application review, CoPA recommends replacing all letters of recommendation with structured evaluative letters as a universal tool in the application process.1 These letters would include specialty-specific questions based on core competencies and would be completed by an evaluator who directly observed the student. Additionally, the group recommends revising the content and structure of the medical student performance evaluation to improve access to longitudinal assessment data about students. Ideally, developing UME competency outcomes to apply across learners would decrease reliance on traditional but potentially problematic application elements, such as licensing examination scores, clinical grades, and narrative evaluations.1

To optimize residency application processes, CoPA recommends exploring innovative approaches to reduce application volume and maximize applicants interviewing and matching at programs where mutual interest is high.1 Suggestions to address these issues include preference signaling, application caps, and/or additional rounds of application or matching. Standardization of the interview process also is recommended to improve equity, minimize educational disruption, and improve applicant well-being. Suggestions include the use of common interview offer and scheduling platforms, policies to govern interview offers and scheduling timelines, interview caps, and ongoing study of the impact of virtual interviews.1

Residency Application Innovations Implemented by Other Specialties

A number of specialties have developed innovations in the residency application process to improve equity and fairness as well as optimize applicant-program fit. Emergency medicine created a now widely adopted, specialty-specific standardized letter of evaluation (SLOE).2 It compares applicants across a number of measures that include personal qualities, clinical skills, and a global assessment. The SLOE is designed to assess and compare applicants across institutions rather than provide recommendations. The emergency medicine SLOE also provides useful information about the letter writer, including duration and depth of interaction with the applicant and distribution of rankings of prior applicants.2

In 2019, obstetrics and gynecology launched a standardized application and interview process, which set a specialty-wide application deadline, limited interview invitations to the number of interview positions available, encouraged coordinated release of interview offers, and allowed applicants 72 hours to respond to invitations.3 These measures were implemented to improve fairness, transparency, and applicant well-being, as well as to promote equitable distribution of interviews. Data following this launch suggested that universal offer dates reduced excessive interviewing among competitive applicants.3

Last year, otolaryngology implemented a process known as preference signaling in which applicants were able to signal up to 5 preferred programs at the time of application. A signal allowed applicants to demonstrate interest in specific programs and could be used by programs during their application review process. Most applicants opted to submit signals, and programs received 0 to 71 signals (mean, 22).4 Almost all programs received at least 1 signal. The rate of receiving an interview was significantly higher for signaled programs (58%) compared to nonsignaled programs (14%)(P<.001), indicating that preference signaling may be beneficial for both programs and applicants for interview selection.4

Residency Application Innovations Implemented by Dermatology

Over the last 2 application cycles, dermatology has implemented several innovations to the residency application process. Initial work included release of guidelines for residency programs to conduct holistic application review,5 recommendations for website updates to share program-specific information with prospective trainees,6 and informational webinars and statements to update dermatology applicants about changes to the process and to answer application-related questions.7-9

In 2020, dermatology initiated a coordinated interview invitation release in which interview offers were released on prespecified dates and applicants were given 48 hours prior to scheduling. Approximately 50% of residency programs participated in the first year, yet nearly all programs released on 1 of 2 universal dates in the current cycle. In a recent survey of dermatology applicants, nearly 90% supported coordinated release.10 Several other specialties also have incorporated universal release dates into their processes.

For the 2021-2022 application cycle, dermatology—along with internal medicine and general surgery—participated in the Association of American Medical Colleges’ pilot supplemental Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) application.11 The pilot was designed as a first step to updating the ERAS content by allowing students to share more information about their extracurricular, research, and clinical activities, as well as geographic and program preferences to optimize applicant-program fit. Preference signaling, similar to the otolaryngology process, was included in the supplemental application, with dermatology applicants choosing up to 3 preferred programs to signal, excluding their home programs and any programs where they completed in-person away rotations. Preliminary data suggest that the vast majority of dermatology programs and applicants participated in the supplemental application.12 Ongoing analysis of survey data from applicants, advisors, and program directors will help inform future directions. Dermatology has been an integral partner in the development, implementation, and evaluation of this pilot.

Proposed Innovations to the Application Process

Given the challenges of the current application process, there has been a long list of proposed innovations to ameliorate applicant, advisor, and program concerns.13 Many of these approaches are intended to respond to increasing costs to programs and applicants as well as the lack of equity in the process. Application caps and an early result acceptance program have both been proposed to address the ever-increasing volume of applications.14,15 Neither of these proposals has been adopted by a specialty yet, but obstetrics and gynecology stakeholders have shown broad support for an early result acceptance program, signaling a possible future pilot.16

Interview caps also have been proposed to promote more equitable distribution of interview positions.17 Ophthalmology implemented this approach in the 2021-2022 application cycle, with applicants limited to a maximum of 18 interviews.18 Data from this pilot will help determine the effect of interview caps as well as the optimal limit, which will vary by specialty.

Changes to the application content itself could better facilitate holistic review and optimize applicant-program fit. This is the principle driving the pilot supplemental ERAS application, but it also has been addressed in other specialties. Ophthalmology replaced the traditional personal statement with a shorter autobiographical statement as well as 2 short personal essay questions. Plastic surgery designed a common supplemental application, currently in its second iteration, that highlights specialty-specific information from applicants to promote holistic review and eventually reduce application costs.19

Final Thoughts

The reforms introduced and proposed by dermatology and other specialties represent initial steps to address the issues inherent to the current residency application process. Providing faculty with better tools to holistically assess applicants during the review process and increasing transparency between programs and applicants should help optimize applicant-program fit and increase diversity in the dermatology workforce. Streamlining the application process to allow students to highlight their unique qualities in a user-friendly format as well as addressing potential inequities in interview distribution and access to the application process hopefully will contribute to better outcomes for both programs and applicants. However, many of these steps are likely to create additional administrative burdens on program faculty and are unlikely to allay student fears about matching.

The underlying issue for many specialties, and particularly for dermatology, is that demand far outstrips supply. With stable numbers of residency positions and an ever-increasing number of applicants, the match rate will continue to decrease, leading to increased anxiety among those interested in pursuing dermatology. Although USMLE Step 1 scores have been shown to have racial bias20 and there are no data correlating scores with clinical performance, the elimination of a scoring system may affect the number of applicants entering dermatology with downstream effects on match rates. Heightened anxiety places increased pressure on students to choose a specialty earlier in their training and impacts the activities they pursue during medical school. Overemphasis on specialty choice and the match process can lead to higher rates of burnout among students and trainees, as students may focus on activities designed to increase their chances of matching at the expense of pursuing activities that could lead to greater engagement and passion in their careers—a key protective factor against burnout.

The goal of the residency application process is to optimize fit between candidates and programs by aligning goals, values, and learning environment. Students and programs working together as honest brokers can lead to transformative change in the process, freeing both parties to highlight their unique qualities and contributions. Programs benefit from optimal fit by being able to hone their particular mission and recruit and retain residents and faculty engaged in that mission. Residents will thrive in programs that support their learning and career goals and will ultimately be better positioned to meaningfully contribute to their chosen field in whatever capacity they choose.

Acknowledgments—The views presented in this column reflect those of the 9 elected members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology Residency Program Directors Section steering committee, all of whom are program directors at their institutions (listed in parentheses): Ammar Ahmed, MD (The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas); Yolanda Helfrich, MD (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan); Jo-Ann M. Latkowksi, MD (New York University, New York); Kiran Motaparthi, MD (University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida); Adena E. Rosenblatt, MD, PhD (The University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois); Ilana S. Rosman, MD (Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri); Travis Vandergriff, MD (University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, Texas); Diane Whitaker-Worth, MD (University of Connecticut, Farmington, Connecticut); Scott Worswick, MD (University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California).

Amid increasing numbers of applications, decreasing match rates, and ongoing lack of diversity in the dermatology trainee workforce, the COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional challenges to the dermatology residency application process and laid bare systemic inequities and inherent problems that must be addressed. Historically, dermatology applicants have excelled in academic metrics, such as US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) scores and nomination to the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society. As biases associated with these academic metrics are being elucidated, they have in turn become less available. With the upcoming change in USMLE Step 1 reporting to pass/fail only, as well as the elimination of Alpha Omega Alpha nomination for students, clinical grades, and/or class ranks at many medical schools, other elements of the application, such as volunteer experiences and research publications, may be weighed more heavily in the selection process. This may serve to exacerbate the application arms race, characterized by a steady rise in volunteer experiences, research publications, and research gap years that has already begun and likely will continue, particularly among dermatology applicants.

These issues are not unique to dermatology and are occurring across all medical specialties to varying degrees. The monetary and opportunity costs of the application process have become astronomical for both applicants and faculty. Faculty are overburdened with administrative duties related to resident recruitment and advising, and students are experiencing heightened match-related anxiety earlier and more acutely. These factors may contribute to burnout among trainees and faculty and may have deleterious effects on medical education. It is clear that transformative work must be pursued to ensure an equitable and sustainable residency application process moving forward. In this column, we review the notable work being done within dermatology and across specialties to reform the residency application process.

Coalition Recommendations

In August 2021, the Coalition for Physician Accountability (CoPA) released recommendations for comprehensive improvement of the undergraduate medical education (UME) to graduate medical education transition, which includes residency application. Of the 9 principal themes addressed, 2 focus on the residency application process: (1) equitable mission-driven application review, and (2) optimization of the application, interview, and selection processes, which relates to application volume as well as interview offers and formats.1

In the area of application review, CoPA recommends replacing all letters of recommendation with structured evaluative letters as a universal tool in the application process.1 These letters would include specialty-specific questions based on core competencies and would be completed by an evaluator who directly observed the student. Additionally, the group recommends revising the content and structure of the medical student performance evaluation to improve access to longitudinal assessment data about students. Ideally, developing UME competency outcomes to apply across learners would decrease reliance on traditional but potentially problematic application elements, such as licensing examination scores, clinical grades, and narrative evaluations.1

To optimize residency application processes, CoPA recommends exploring innovative approaches to reduce application volume and maximize applicants interviewing and matching at programs where mutual interest is high.1 Suggestions to address these issues include preference signaling, application caps, and/or additional rounds of application or matching. Standardization of the interview process also is recommended to improve equity, minimize educational disruption, and improve applicant well-being. Suggestions include the use of common interview offer and scheduling platforms, policies to govern interview offers and scheduling timelines, interview caps, and ongoing study of the impact of virtual interviews.1

Residency Application Innovations Implemented by Other Specialties

A number of specialties have developed innovations in the residency application process to improve equity and fairness as well as optimize applicant-program fit. Emergency medicine created a now widely adopted, specialty-specific standardized letter of evaluation (SLOE).2 It compares applicants across a number of measures that include personal qualities, clinical skills, and a global assessment. The SLOE is designed to assess and compare applicants across institutions rather than provide recommendations. The emergency medicine SLOE also provides useful information about the letter writer, including duration and depth of interaction with the applicant and distribution of rankings of prior applicants.2

In 2019, obstetrics and gynecology launched a standardized application and interview process, which set a specialty-wide application deadline, limited interview invitations to the number of interview positions available, encouraged coordinated release of interview offers, and allowed applicants 72 hours to respond to invitations.3 These measures were implemented to improve fairness, transparency, and applicant well-being, as well as to promote equitable distribution of interviews. Data following this launch suggested that universal offer dates reduced excessive interviewing among competitive applicants.3

Last year, otolaryngology implemented a process known as preference signaling in which applicants were able to signal up to 5 preferred programs at the time of application. A signal allowed applicants to demonstrate interest in specific programs and could be used by programs during their application review process. Most applicants opted to submit signals, and programs received 0 to 71 signals (mean, 22).4 Almost all programs received at least 1 signal. The rate of receiving an interview was significantly higher for signaled programs (58%) compared to nonsignaled programs (14%)(P<.001), indicating that preference signaling may be beneficial for both programs and applicants for interview selection.4

Residency Application Innovations Implemented by Dermatology

Over the last 2 application cycles, dermatology has implemented several innovations to the residency application process. Initial work included release of guidelines for residency programs to conduct holistic application review,5 recommendations for website updates to share program-specific information with prospective trainees,6 and informational webinars and statements to update dermatology applicants about changes to the process and to answer application-related questions.7-9