User login

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

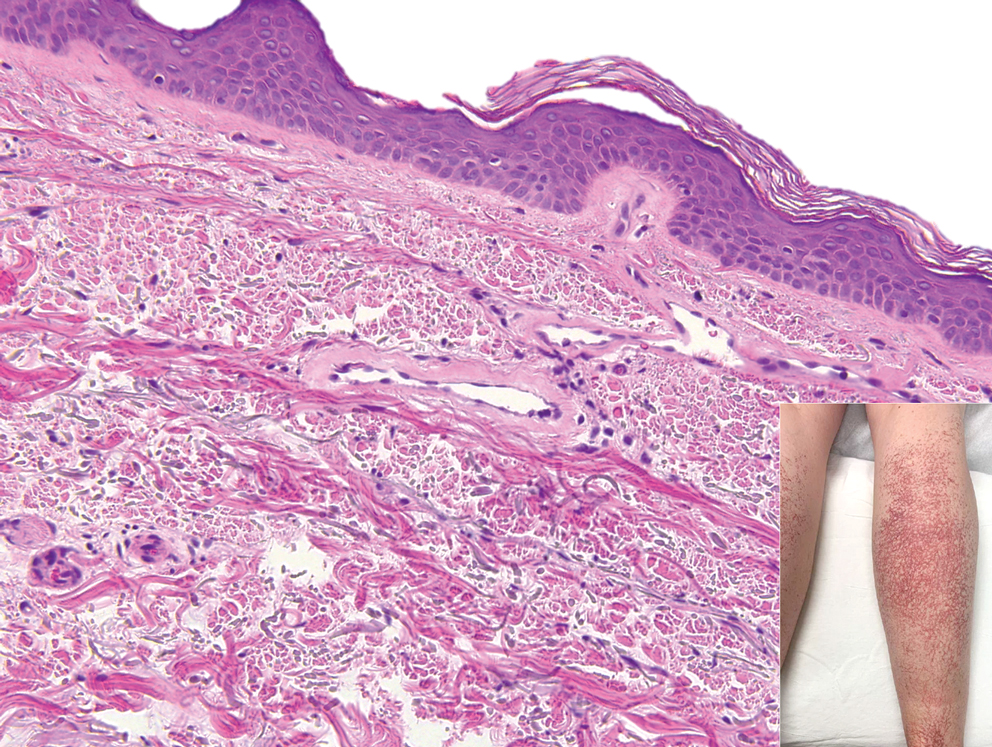

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an idiopathic microangiopathy of the small vessels in the superficial dermis. A condition first identified by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000, CCV likely is underreported, as its clinical mimickers are not routinely biopsied.2 It presents as asymptomatic telangiectatic macules, initially on the lower extremities and often spreading to the trunk. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy often is seen in middle-aged adults, and most patients have comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or cardiovascular disease. The exact etiology of this disease is unknown.3,4

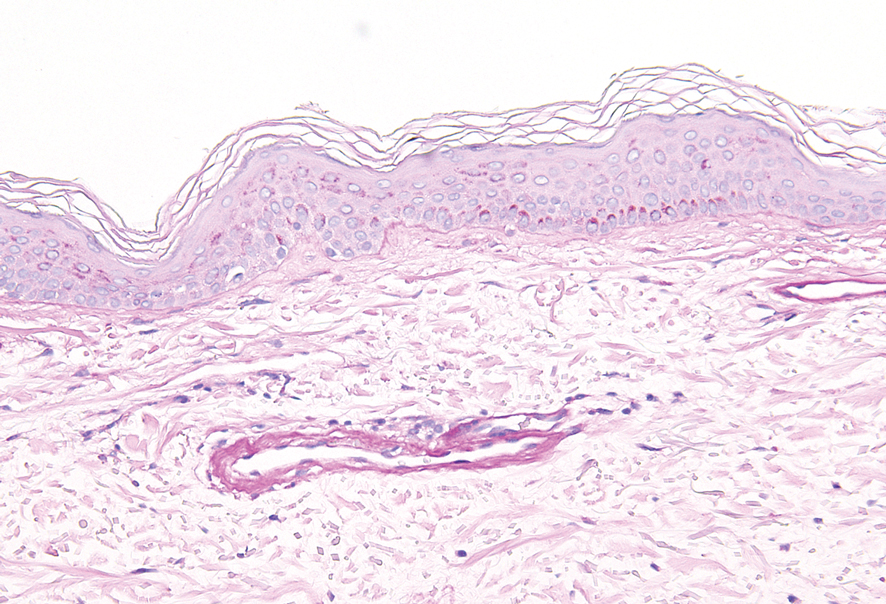

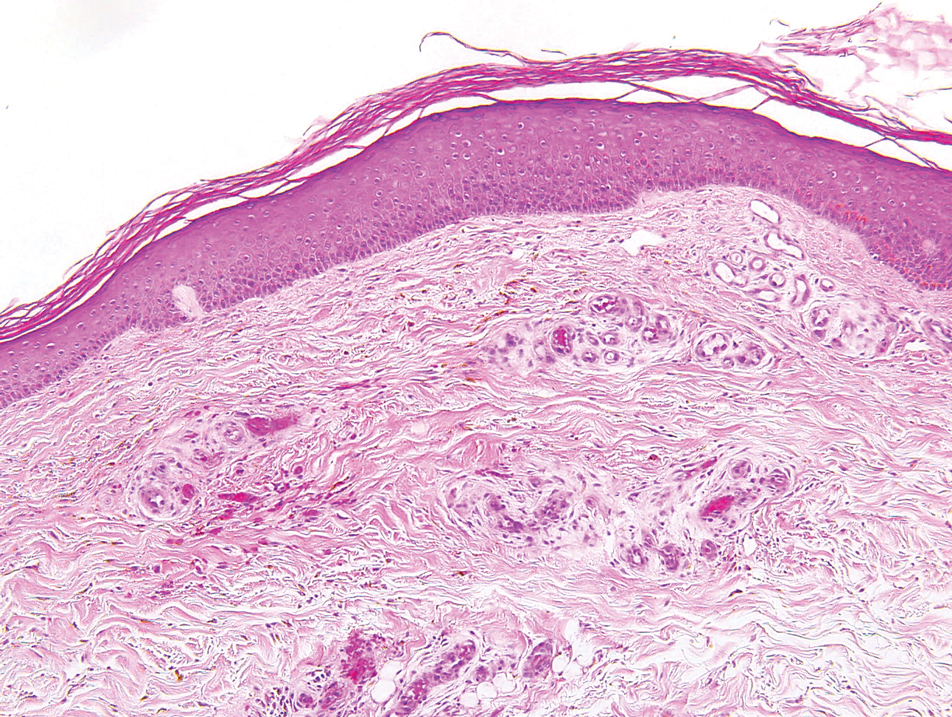

Histopathologically, CCV is characterized by dilated superficial vessels with thickened eosinophilic walls. The eosinophilic material is composed of hyalinized type IV collagen, which is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 1).3,4 Stains for amyloid are negative.

Generalized essential telangiectasia (GET) is a condition that presents with symmetric, blanchable, erythematous telangiectases.5 These lesions can occur alone or can accompany systemic diseases. Similar to CCV, the telangiectases tend to begin on the legs before gradually spreading to the trunk; however, this process more often is seen in females and occurs at an earlier age. Unlike CCV, GET can occur on mucosal surfaces, with cases of conjunctival and oral involvement reported.6 Generalized essential telangiectasia usually is a diagnosis of exclusion.7,8 It is thought that many CCV lesions have been misclassified clinically as GET, which highlights the importance of biopsy. Microscopically, GET is distinct from CCV in that the superficial dermis lacks thick-walled vessels.5,7 Although usually not associated with systemic diseases or progressive morbidity, treatment options are limited.8

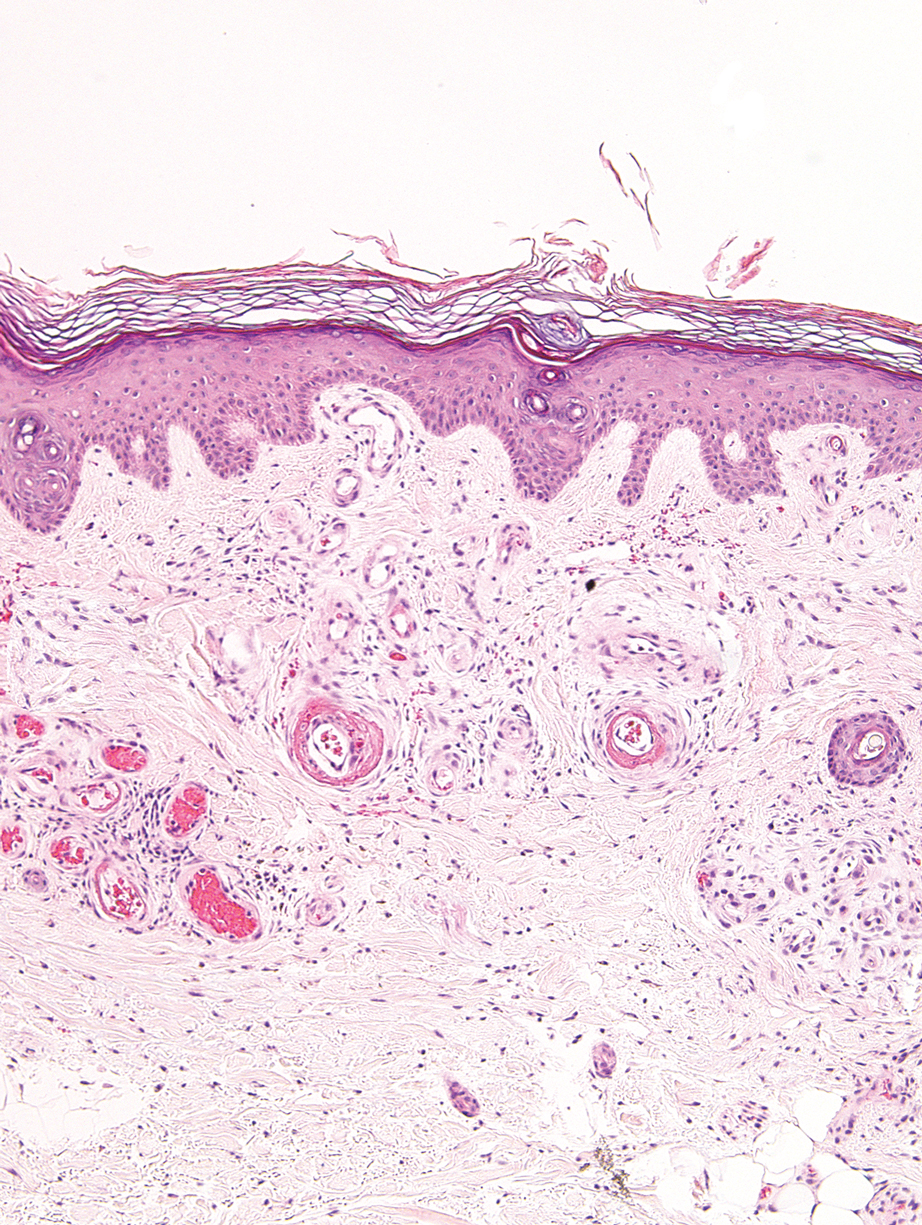

Livedoid vasculopathy, also known as atrophie blanche, is caused by fibrin thrombi occlusion of dermal vessels. Clinically, patients have recurrent telangiectatic papules and painful ulcers on the lower extremities that gradually heal, leaving behind white stellate scars. It is caused by an underlying prothrombotic state with a superimposed inflammatory response.9 Livedoid vasculopathy primarily affects middle-aged women, and many patients have comorbidities such as scleroderma or systemic lupus erythematosus. Histologically, the epidermis often is ulcerated, and thrombi are visualized within small vessels. Eosinophilic fibrinoid material is deposited in vessel walls, including but not confined to vessels at the base of the epidermal ulcer (Figure 2). The fibrinoid material is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant and can be highlighted with immunofluorescence, which may help to distinguish this entity from CCV.1,9 As the disease progresses, vessels are diffusely hyalinized, and there is epidermal atrophy and dermal sclerosis. Treatment options include antiplatelet and fibrinolytic drugs with a multidisciplinary approach to resolve pain and scarring.9

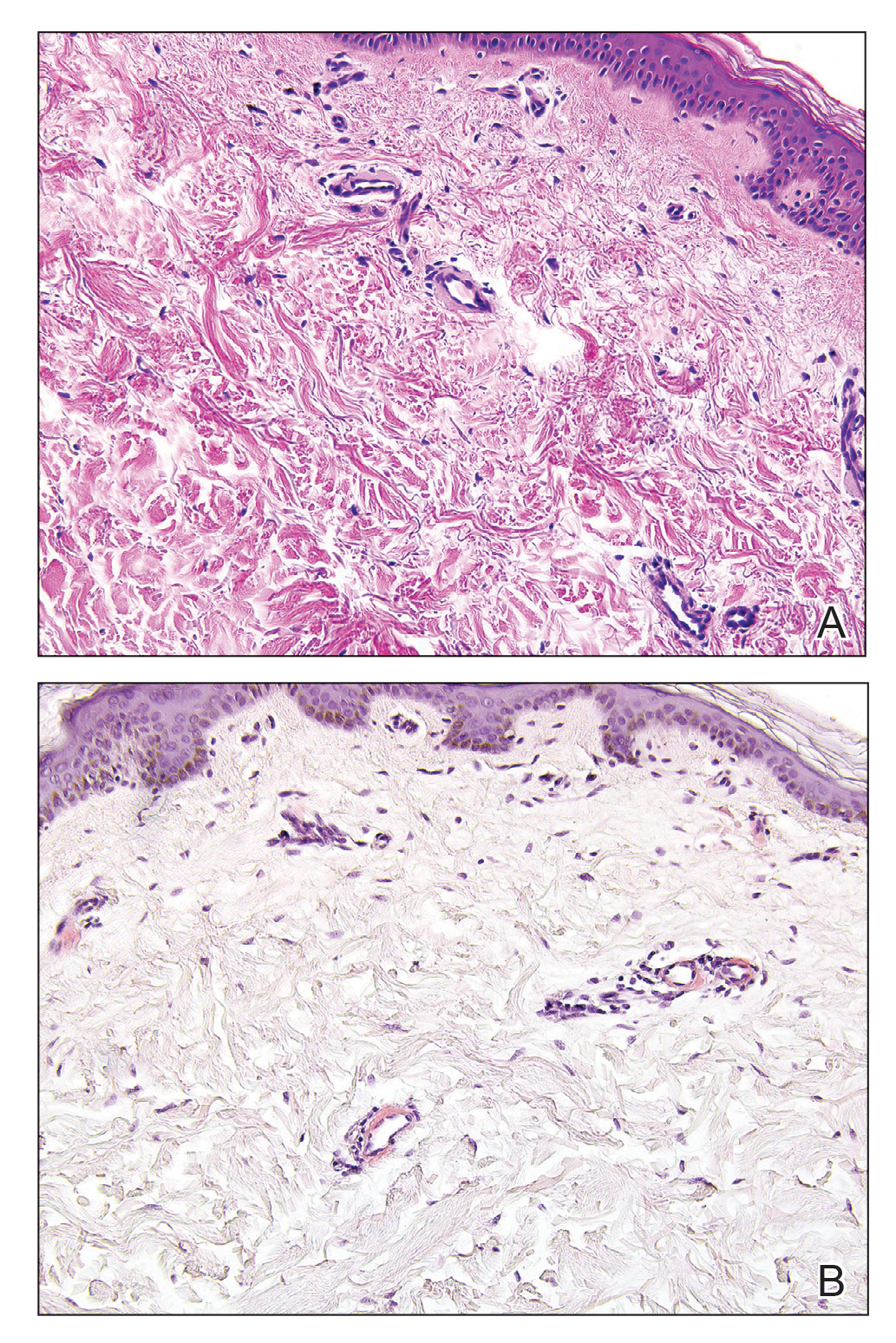

Primary systemic amyloidosis is a rare condition, and cutaneous manifestations are seen in approximately one-third of affected individuals. Amyloid deposition results in waxy papules that predominantly affect the face and periorbital areas but also may occur on the neck, flexural areas, and genitalia.5 Because the amyloid deposits also can be found within vessel walls, hemorrhagic lesions may occur. Microscopically, amorphous eosinophilic material can be found within the vessel walls, similar to CCV (Figure 3A); however, when stained with Congo red, cutaneous amyloidosis shows waxy red-orange material involving the vessel walls and exhibits apple green birefringence under polarization (Figure 3B).10 Amyloid also will be negative for type IV collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, whereas CCV will be positive.5

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Bondier L, Tardieu M, Leveque P, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of two cases presenting as disseminated telangiectasias and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:682-688.

- Sartori DS, Almeida HL Jr, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52.

- Patterson JW, ed. Vascular tumors. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016:1069-1115.

- Knöpfel N, Martín-Santiago A, Saus C, et al. Extensive acquired telangiectasias: comparison of generalized essential telangiectasia and cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:E21-E26.

- Karimkhani C, Boyers LN, Olivere J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Cutis. 2019;103:E7-E8.

- McGrae JD, Winkelmann RK. Generalized essential telangiectasia: report of a clinical and histochemical study of 13 patients with acquired cutaneous lesions. JAMA. 1963;185:909-913.

- Vasudeva B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478.

- Ko CJ, Barr RJ. Color--pink. In: Ko CJ, Barr RJ, eds. Dermatopathology: Diagnosis by First Impression. 3rd ed. Wiley; 2016:303-322.

- Clark ML, McGuinness AE, Vidal CI. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a unique case with positive direct immunofluorescence findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:77-79.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an idiopathic microangiopathy of the small vessels in the superficial dermis. A condition first identified by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000, CCV likely is underreported, as its clinical mimickers are not routinely biopsied.2 It presents as asymptomatic telangiectatic macules, initially on the lower extremities and often spreading to the trunk. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy often is seen in middle-aged adults, and most patients have comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or cardiovascular disease. The exact etiology of this disease is unknown.3,4

Histopathologically, CCV is characterized by dilated superficial vessels with thickened eosinophilic walls. The eosinophilic material is composed of hyalinized type IV collagen, which is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 1).3,4 Stains for amyloid are negative.

Generalized essential telangiectasia (GET) is a condition that presents with symmetric, blanchable, erythematous telangiectases.5 These lesions can occur alone or can accompany systemic diseases. Similar to CCV, the telangiectases tend to begin on the legs before gradually spreading to the trunk; however, this process more often is seen in females and occurs at an earlier age. Unlike CCV, GET can occur on mucosal surfaces, with cases of conjunctival and oral involvement reported.6 Generalized essential telangiectasia usually is a diagnosis of exclusion.7,8 It is thought that many CCV lesions have been misclassified clinically as GET, which highlights the importance of biopsy. Microscopically, GET is distinct from CCV in that the superficial dermis lacks thick-walled vessels.5,7 Although usually not associated with systemic diseases or progressive morbidity, treatment options are limited.8

Livedoid vasculopathy, also known as atrophie blanche, is caused by fibrin thrombi occlusion of dermal vessels. Clinically, patients have recurrent telangiectatic papules and painful ulcers on the lower extremities that gradually heal, leaving behind white stellate scars. It is caused by an underlying prothrombotic state with a superimposed inflammatory response.9 Livedoid vasculopathy primarily affects middle-aged women, and many patients have comorbidities such as scleroderma or systemic lupus erythematosus. Histologically, the epidermis often is ulcerated, and thrombi are visualized within small vessels. Eosinophilic fibrinoid material is deposited in vessel walls, including but not confined to vessels at the base of the epidermal ulcer (Figure 2). The fibrinoid material is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant and can be highlighted with immunofluorescence, which may help to distinguish this entity from CCV.1,9 As the disease progresses, vessels are diffusely hyalinized, and there is epidermal atrophy and dermal sclerosis. Treatment options include antiplatelet and fibrinolytic drugs with a multidisciplinary approach to resolve pain and scarring.9

Primary systemic amyloidosis is a rare condition, and cutaneous manifestations are seen in approximately one-third of affected individuals. Amyloid deposition results in waxy papules that predominantly affect the face and periorbital areas but also may occur on the neck, flexural areas, and genitalia.5 Because the amyloid deposits also can be found within vessel walls, hemorrhagic lesions may occur. Microscopically, amorphous eosinophilic material can be found within the vessel walls, similar to CCV (Figure 3A); however, when stained with Congo red, cutaneous amyloidosis shows waxy red-orange material involving the vessel walls and exhibits apple green birefringence under polarization (Figure 3B).10 Amyloid also will be negative for type IV collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, whereas CCV will be positive.5

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an idiopathic microangiopathy of the small vessels in the superficial dermis. A condition first identified by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000, CCV likely is underreported, as its clinical mimickers are not routinely biopsied.2 It presents as asymptomatic telangiectatic macules, initially on the lower extremities and often spreading to the trunk. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy often is seen in middle-aged adults, and most patients have comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or cardiovascular disease. The exact etiology of this disease is unknown.3,4

Histopathologically, CCV is characterized by dilated superficial vessels with thickened eosinophilic walls. The eosinophilic material is composed of hyalinized type IV collagen, which is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 1).3,4 Stains for amyloid are negative.

Generalized essential telangiectasia (GET) is a condition that presents with symmetric, blanchable, erythematous telangiectases.5 These lesions can occur alone or can accompany systemic diseases. Similar to CCV, the telangiectases tend to begin on the legs before gradually spreading to the trunk; however, this process more often is seen in females and occurs at an earlier age. Unlike CCV, GET can occur on mucosal surfaces, with cases of conjunctival and oral involvement reported.6 Generalized essential telangiectasia usually is a diagnosis of exclusion.7,8 It is thought that many CCV lesions have been misclassified clinically as GET, which highlights the importance of biopsy. Microscopically, GET is distinct from CCV in that the superficial dermis lacks thick-walled vessels.5,7 Although usually not associated with systemic diseases or progressive morbidity, treatment options are limited.8

Livedoid vasculopathy, also known as atrophie blanche, is caused by fibrin thrombi occlusion of dermal vessels. Clinically, patients have recurrent telangiectatic papules and painful ulcers on the lower extremities that gradually heal, leaving behind white stellate scars. It is caused by an underlying prothrombotic state with a superimposed inflammatory response.9 Livedoid vasculopathy primarily affects middle-aged women, and many patients have comorbidities such as scleroderma or systemic lupus erythematosus. Histologically, the epidermis often is ulcerated, and thrombi are visualized within small vessels. Eosinophilic fibrinoid material is deposited in vessel walls, including but not confined to vessels at the base of the epidermal ulcer (Figure 2). The fibrinoid material is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant and can be highlighted with immunofluorescence, which may help to distinguish this entity from CCV.1,9 As the disease progresses, vessels are diffusely hyalinized, and there is epidermal atrophy and dermal sclerosis. Treatment options include antiplatelet and fibrinolytic drugs with a multidisciplinary approach to resolve pain and scarring.9

Primary systemic amyloidosis is a rare condition, and cutaneous manifestations are seen in approximately one-third of affected individuals. Amyloid deposition results in waxy papules that predominantly affect the face and periorbital areas but also may occur on the neck, flexural areas, and genitalia.5 Because the amyloid deposits also can be found within vessel walls, hemorrhagic lesions may occur. Microscopically, amorphous eosinophilic material can be found within the vessel walls, similar to CCV (Figure 3A); however, when stained with Congo red, cutaneous amyloidosis shows waxy red-orange material involving the vessel walls and exhibits apple green birefringence under polarization (Figure 3B).10 Amyloid also will be negative for type IV collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, whereas CCV will be positive.5

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Bondier L, Tardieu M, Leveque P, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of two cases presenting as disseminated telangiectasias and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:682-688.

- Sartori DS, Almeida HL Jr, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52.

- Patterson JW, ed. Vascular tumors. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016:1069-1115.

- Knöpfel N, Martín-Santiago A, Saus C, et al. Extensive acquired telangiectasias: comparison of generalized essential telangiectasia and cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:E21-E26.

- Karimkhani C, Boyers LN, Olivere J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Cutis. 2019;103:E7-E8.

- McGrae JD, Winkelmann RK. Generalized essential telangiectasia: report of a clinical and histochemical study of 13 patients with acquired cutaneous lesions. JAMA. 1963;185:909-913.

- Vasudeva B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478.

- Ko CJ, Barr RJ. Color--pink. In: Ko CJ, Barr RJ, eds. Dermatopathology: Diagnosis by First Impression. 3rd ed. Wiley; 2016:303-322.

- Clark ML, McGuinness AE, Vidal CI. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a unique case with positive direct immunofluorescence findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:77-79.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Bondier L, Tardieu M, Leveque P, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of two cases presenting as disseminated telangiectasias and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:682-688.

- Sartori DS, Almeida HL Jr, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52.

- Patterson JW, ed. Vascular tumors. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016:1069-1115.

- Knöpfel N, Martín-Santiago A, Saus C, et al. Extensive acquired telangiectasias: comparison of generalized essential telangiectasia and cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:E21-E26.

- Karimkhani C, Boyers LN, Olivere J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Cutis. 2019;103:E7-E8.

- McGrae JD, Winkelmann RK. Generalized essential telangiectasia: report of a clinical and histochemical study of 13 patients with acquired cutaneous lesions. JAMA. 1963;185:909-913.

- Vasudeva B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478.

- Ko CJ, Barr RJ. Color--pink. In: Ko CJ, Barr RJ, eds. Dermatopathology: Diagnosis by First Impression. 3rd ed. Wiley; 2016:303-322.

- Clark ML, McGuinness AE, Vidal CI. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a unique case with positive direct immunofluorescence findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:77-79.

A 54-year-old woman presented with purple-red vessels on the lower legs of 15 years’ duration with gradual proximal progression to involve the thighs, breasts, and forearms. A punch biopsy of the inner thigh was obtained for histopathologic evaluation.