User login

Eccrine Porocarcinoma in 2 Patients

To the Editor:

Porocarcinoma is a rare malignancy of the eccrine sweat glands and is commonly misdiagnosed clinically. We present 2 cases of porocarcinoma and highlight key features of this uncommon disease.

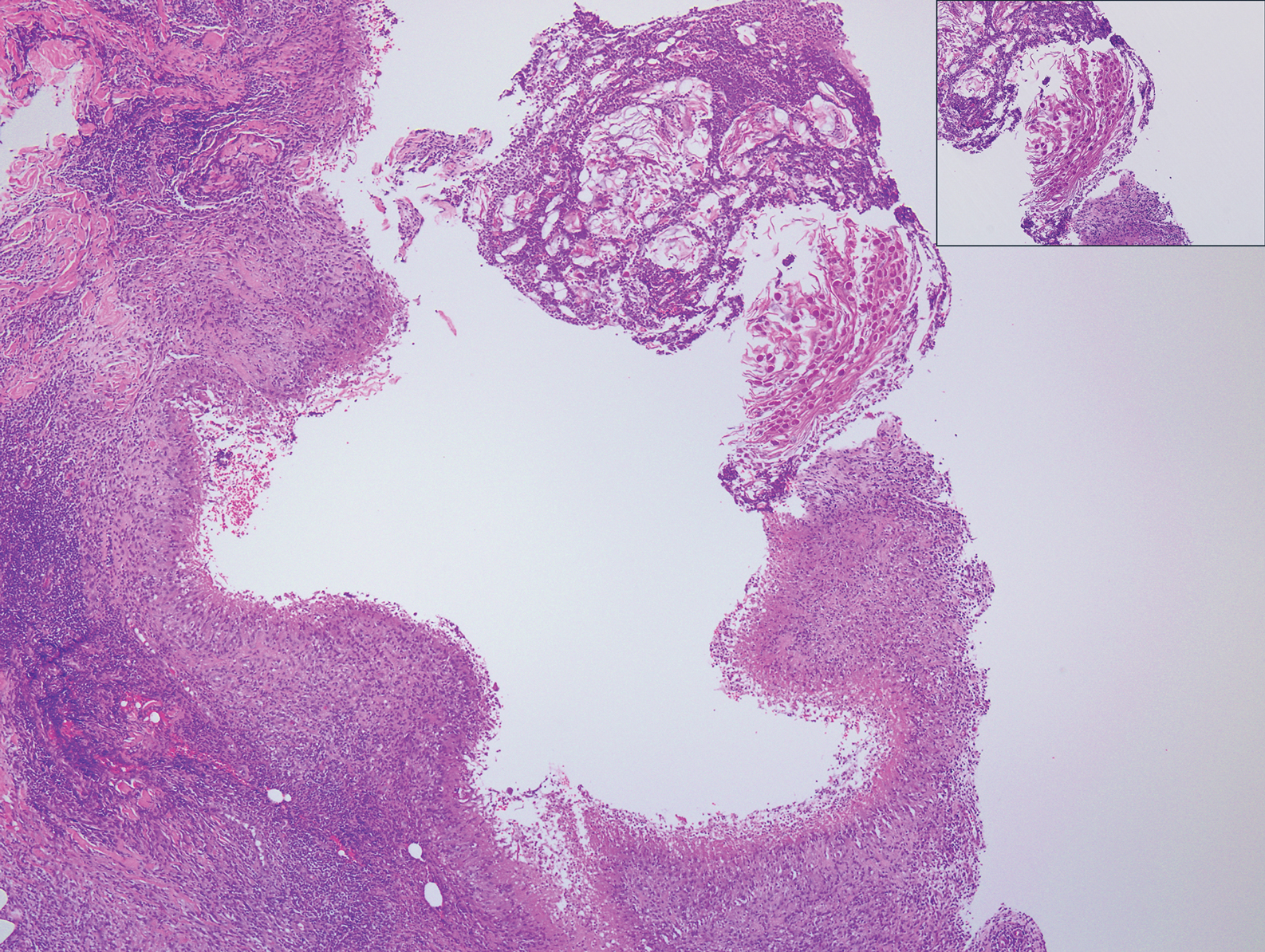

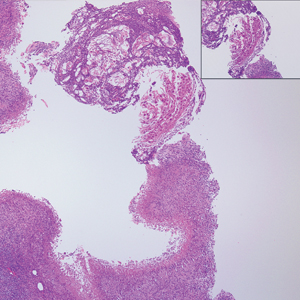

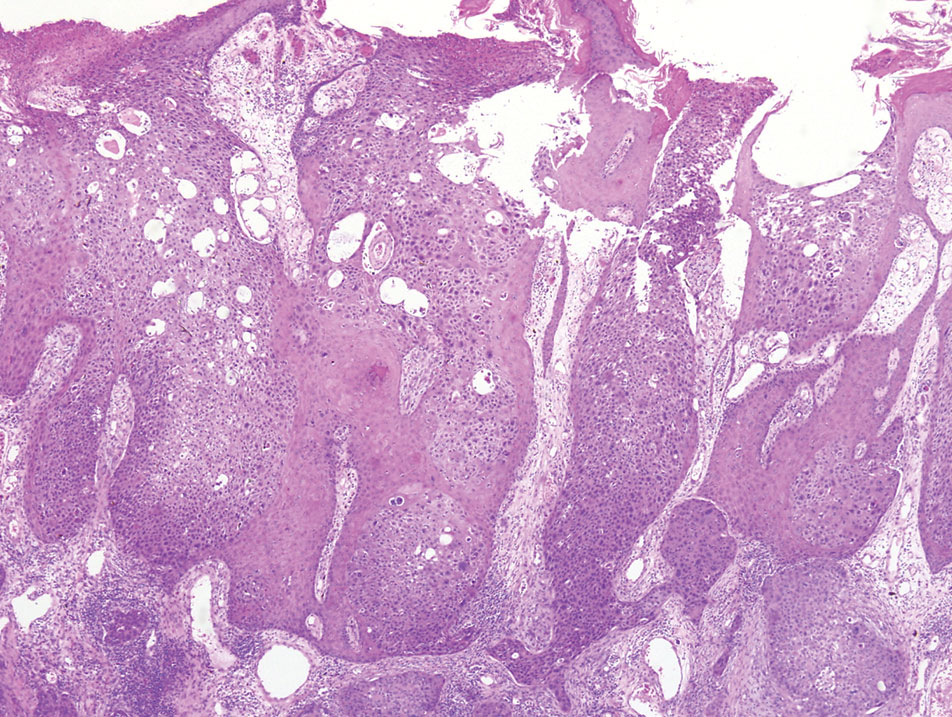

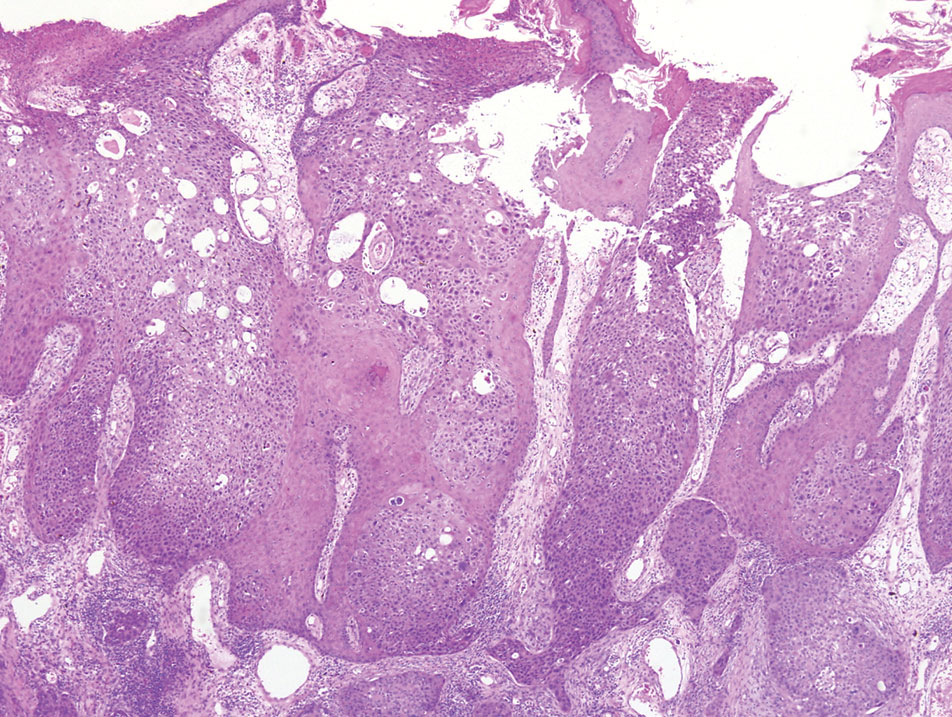

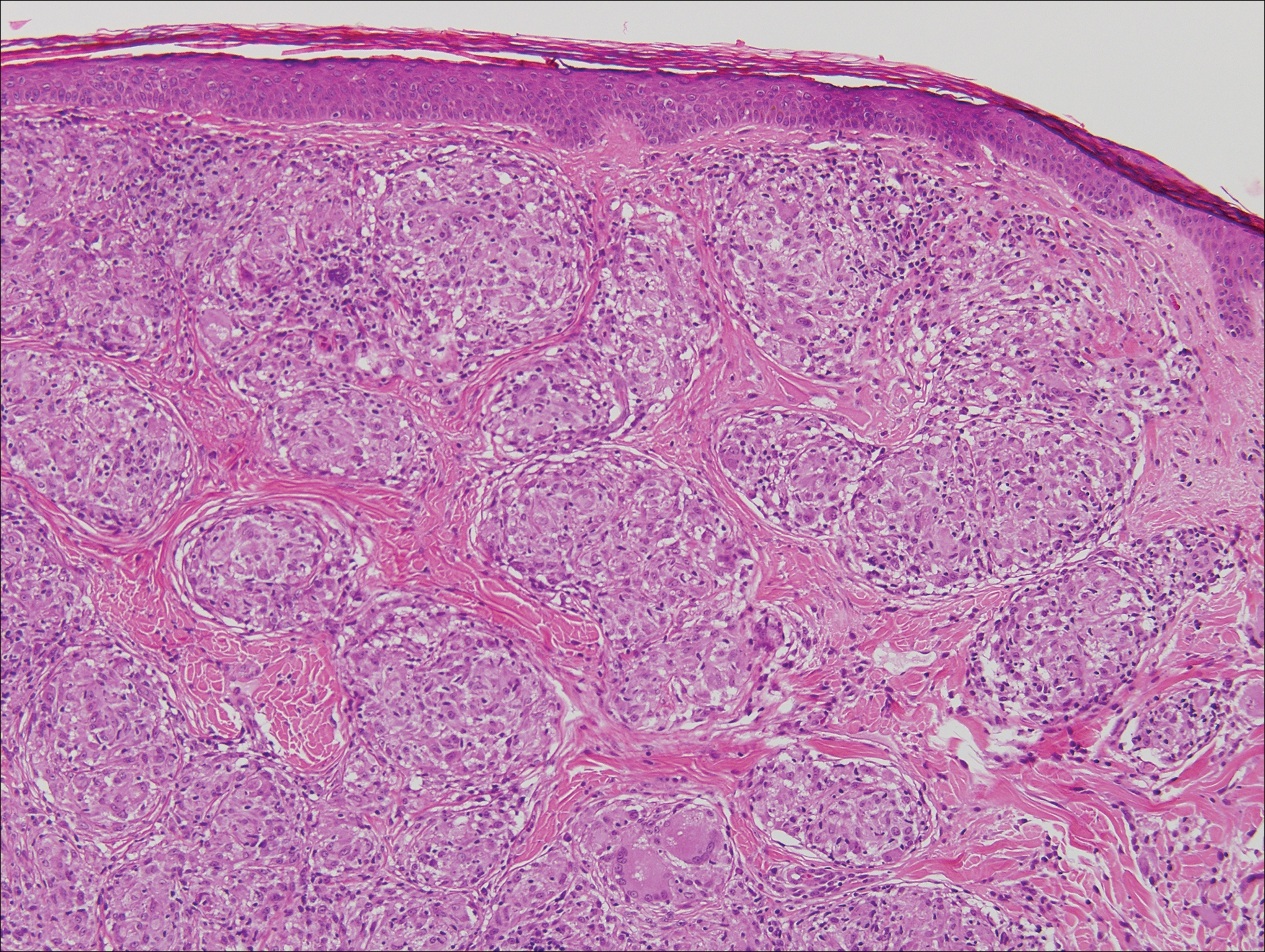

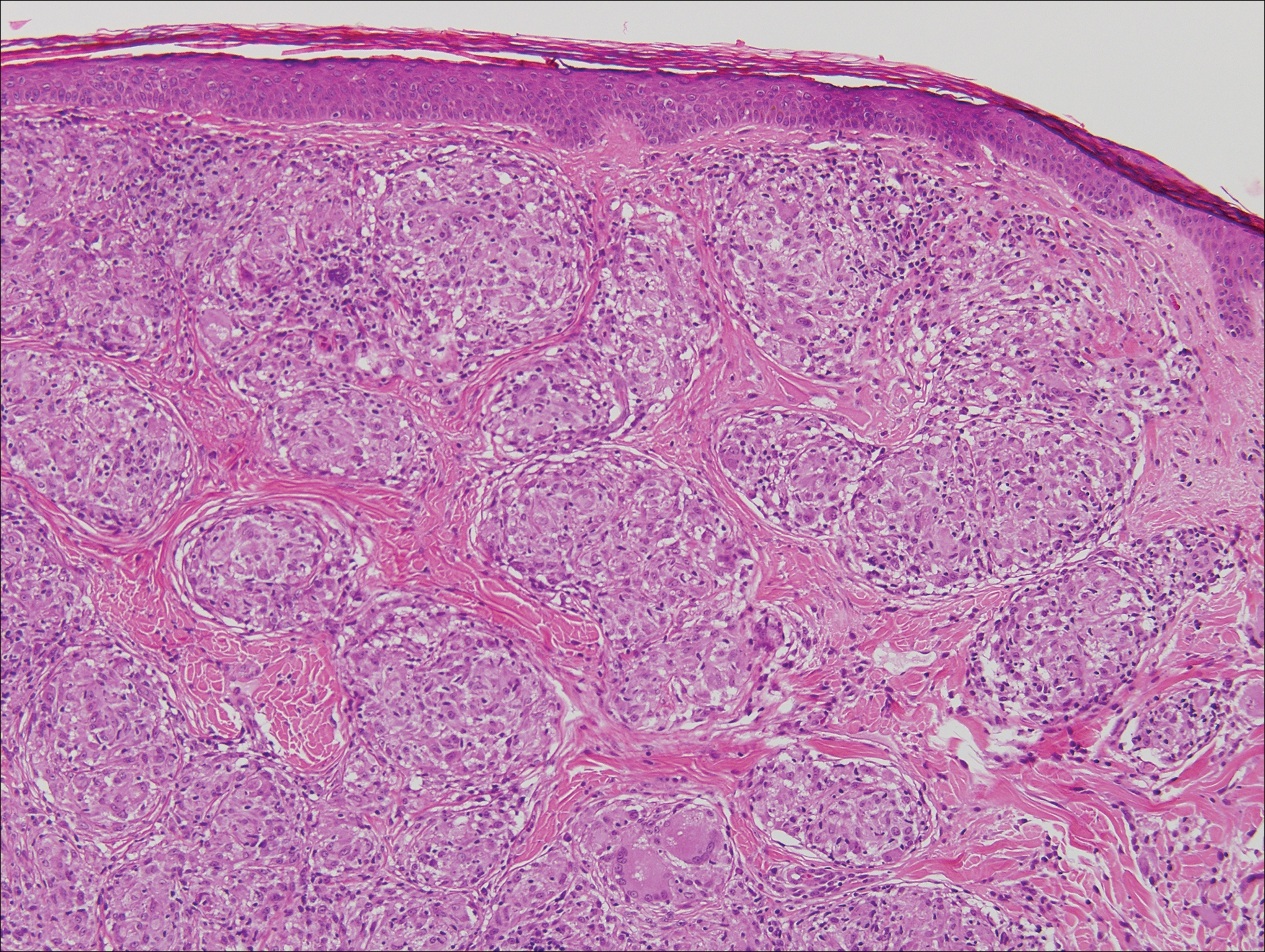

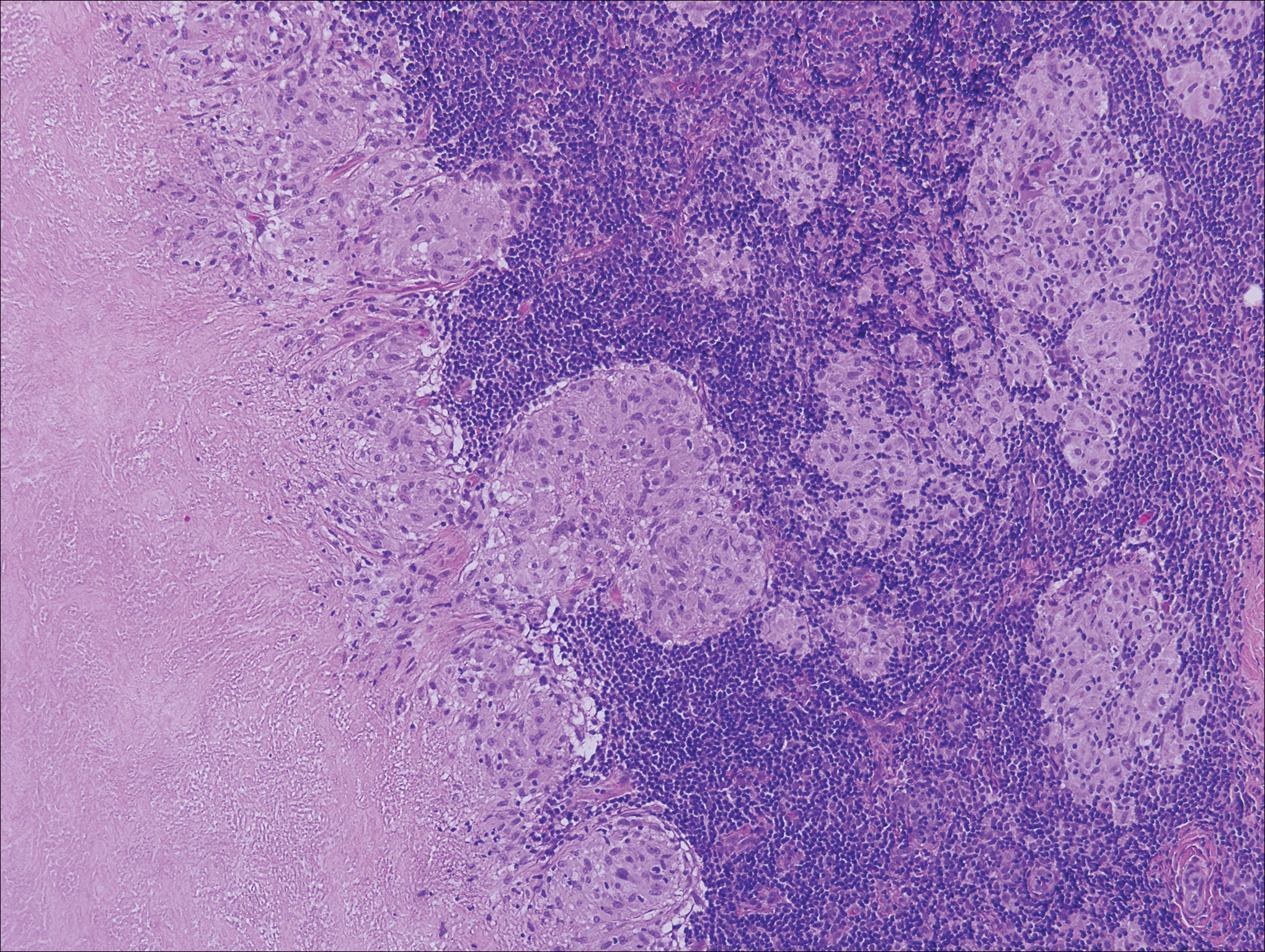

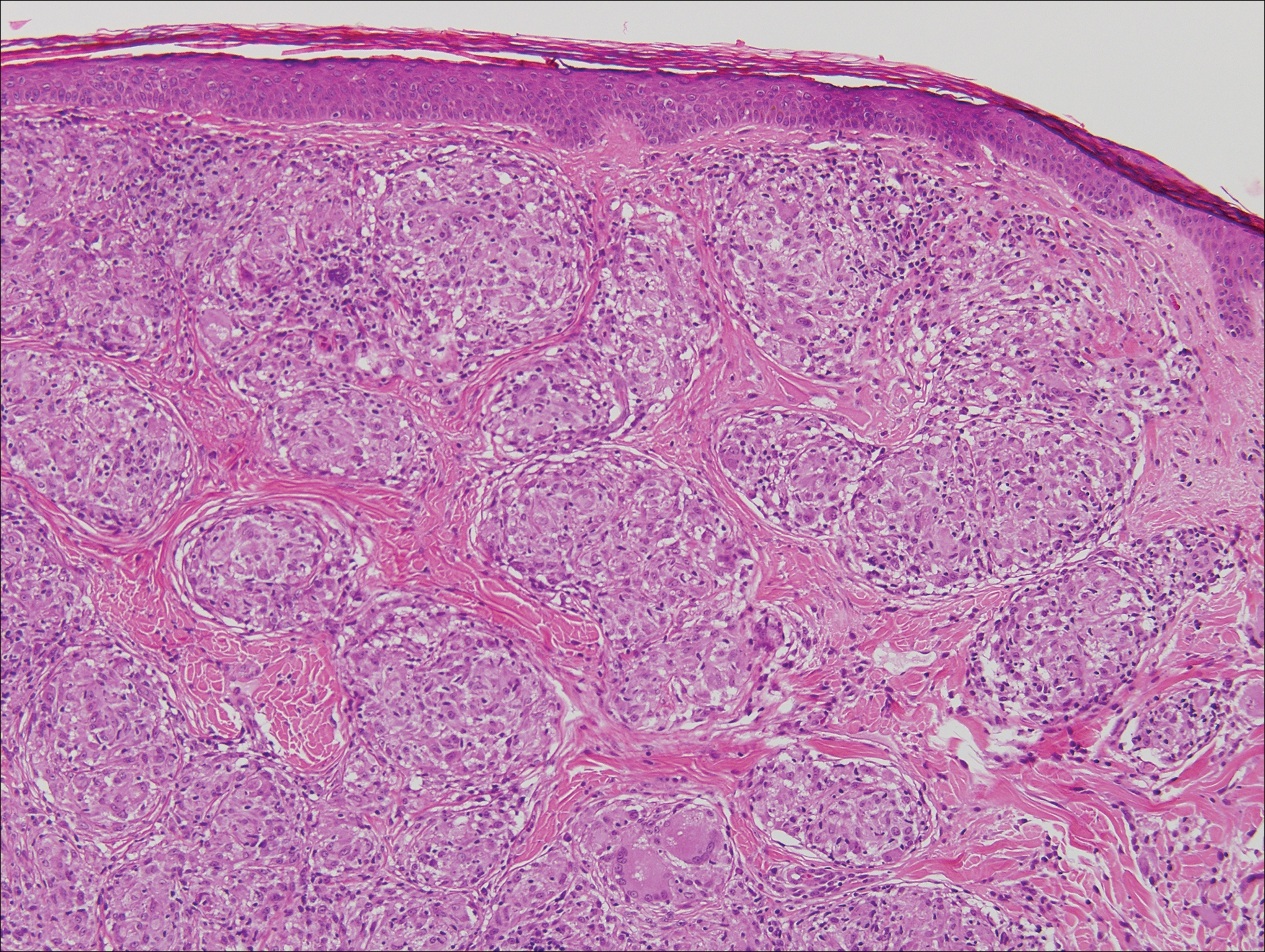

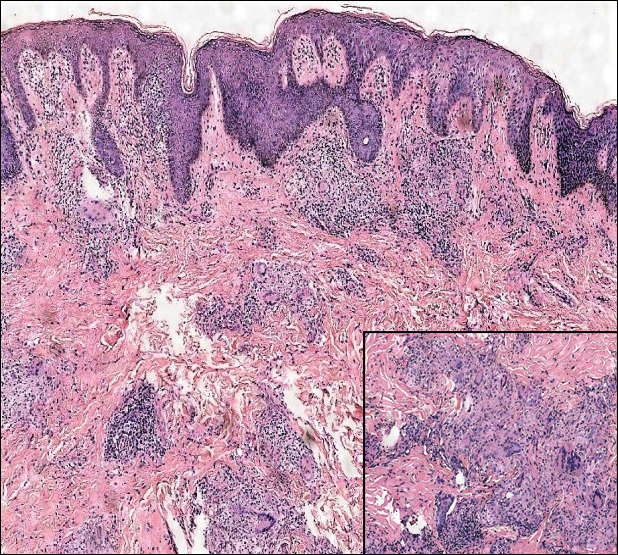

A 65-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a chief concern of a bump on the head of 8 months' duration that gradually enlarged. The lesion recently became painful and contributed to frequent headaches. He reported a history of smoking 1 pack per day and denied trauma to the area or history of immunosuppression. He had no personal or family history of skin cancer. Physical examination revealed a 1.4-cm, heterochromic, pedunculated, keratotic tumor with crusting on the right temporal scalp (Figure 1). No lymphadenopathy was appreciated. The clinical differential diagnosis included irritated seborrheic keratosis, pyogenic granuloma, polypoid malignant melanoma, and nonmelanoma skin cancer. A biopsy of the lesion demonstrated a proliferation of cuboidal cells with focal ductular differentiation arranged in interanastamosing strands arising from the epidermis (Figure 2). Scattered mitotic figures, including atypical forms, cytologic atypia, and foci of necrosis, also were present. The findings were consistent with features of porocarcinoma. Contrast computed tomography of the neck showed no evidence of metastatic disease within the neck. A wide local excision was performed and yielded a tumor measuring 1.8×1.6×0.7 cm with a depth of 0.3 cm and uninvolved margins. No lymphovascular or perineural invasion was identified. At 4-month follow-up, the patient had a well-healed scar on the right scalp without evidence of recurrence or lymphadenopathy.

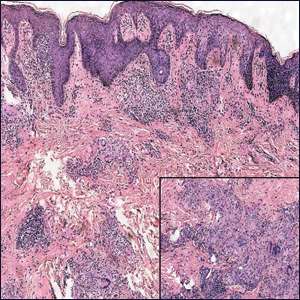

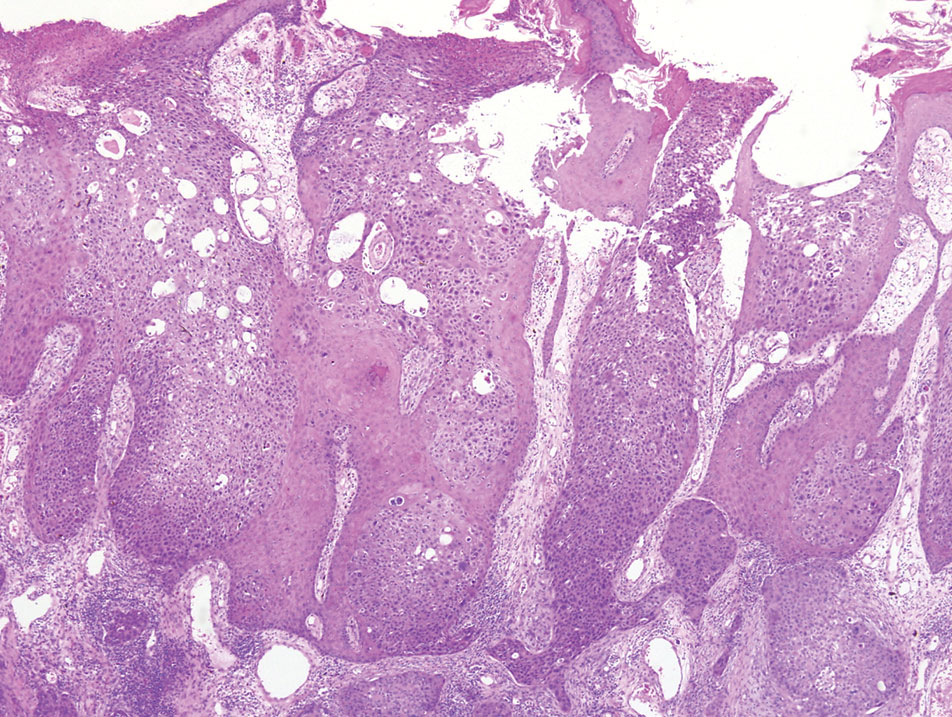

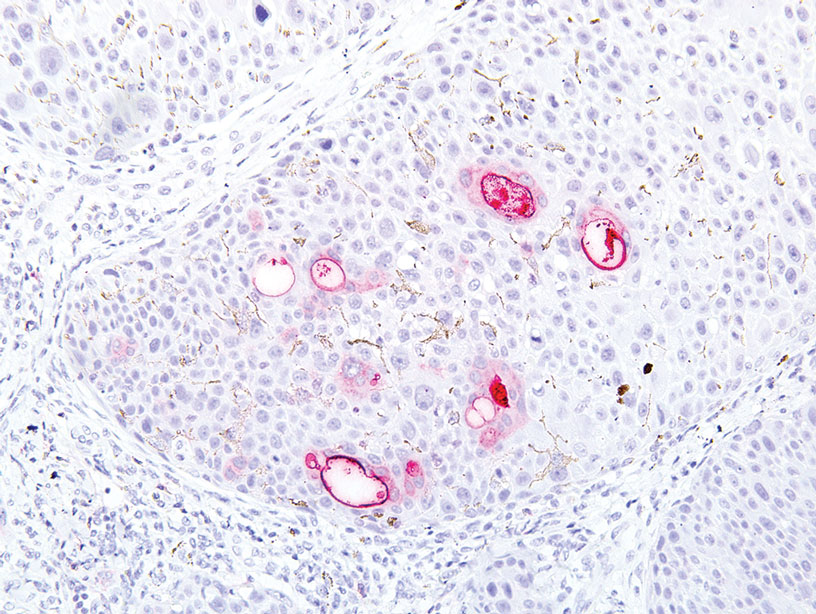

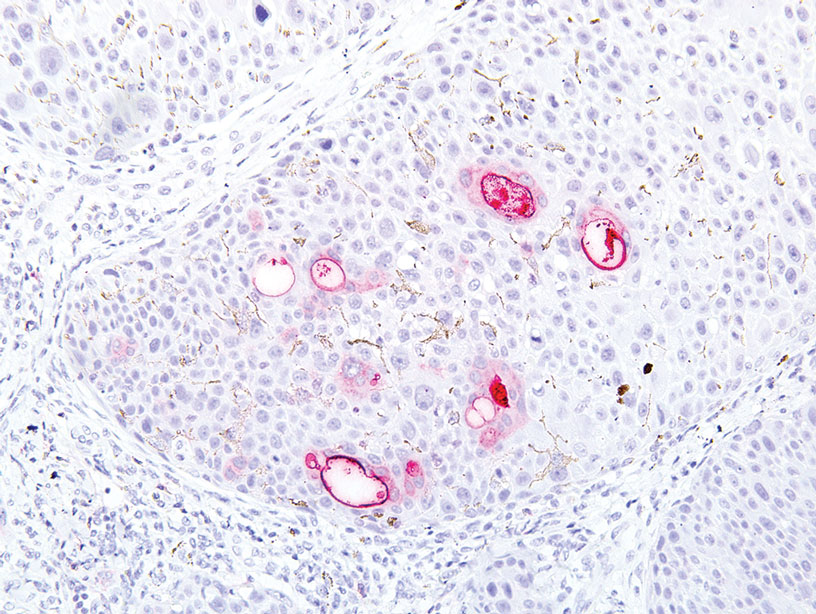

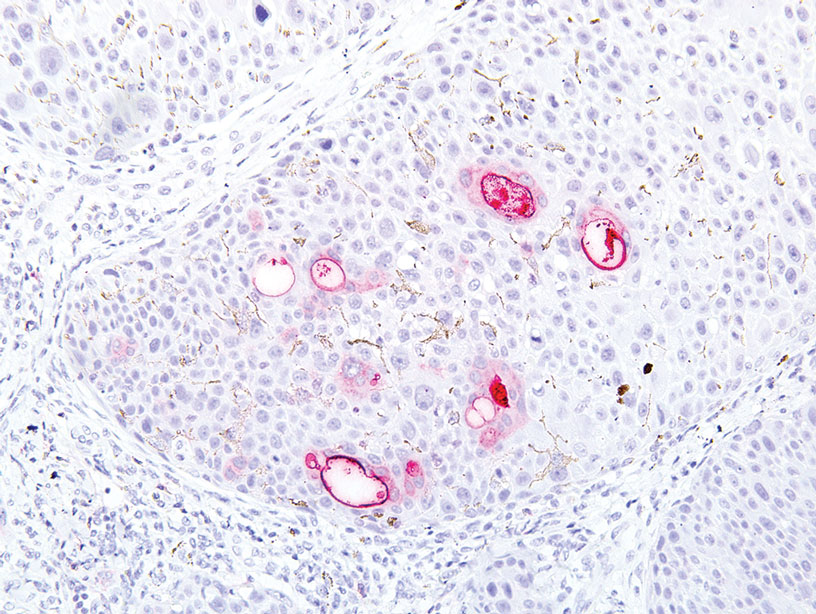

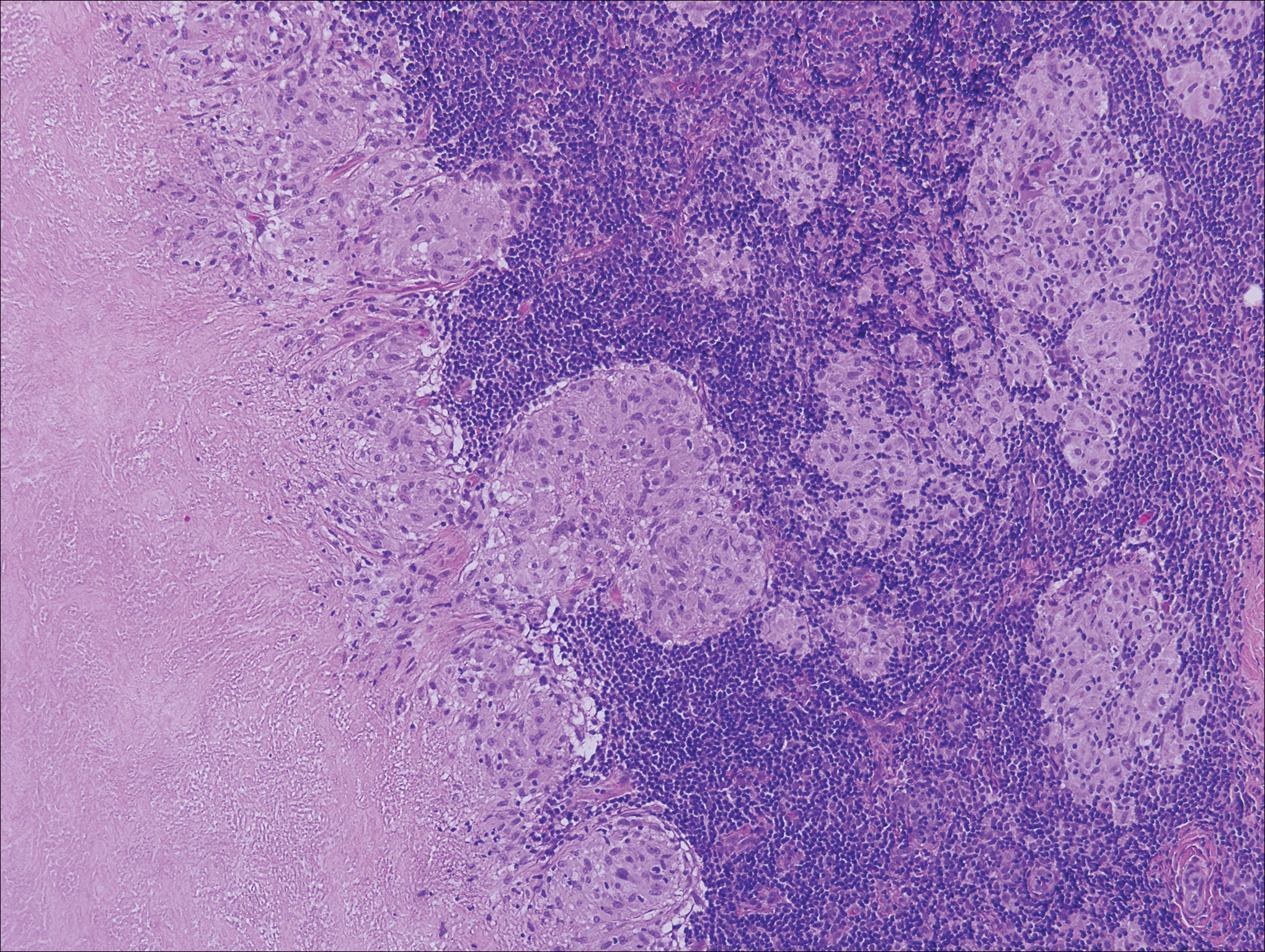

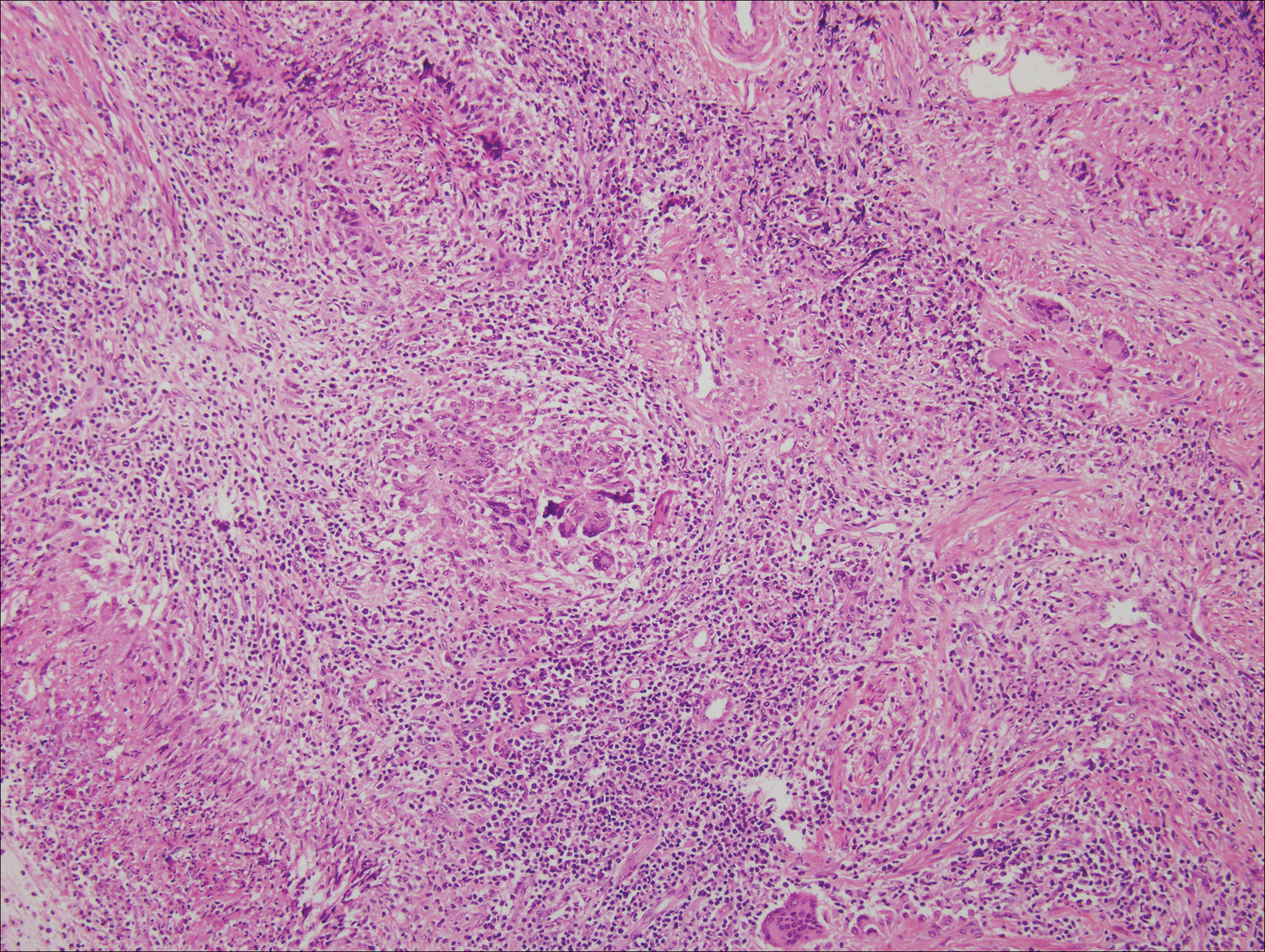

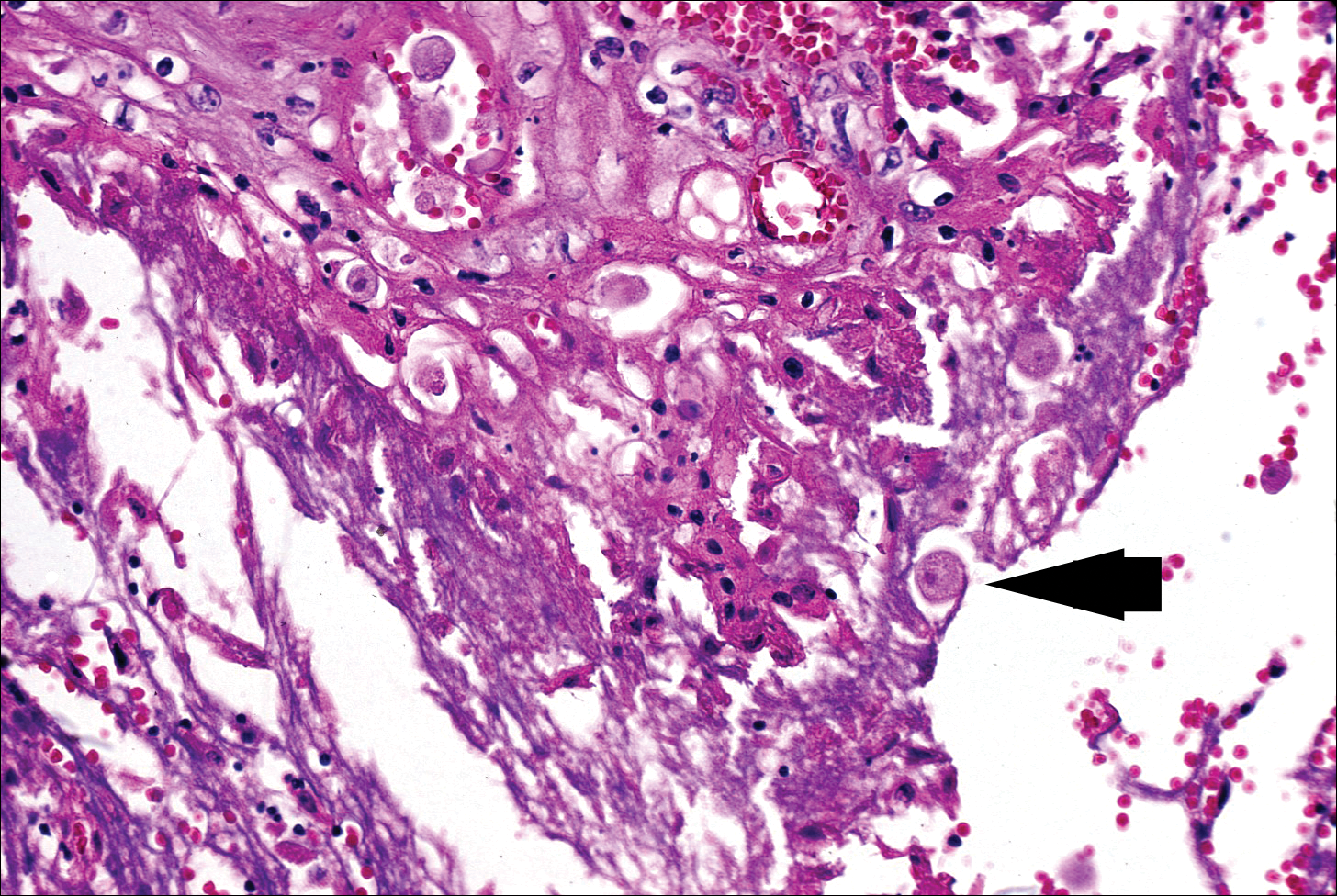

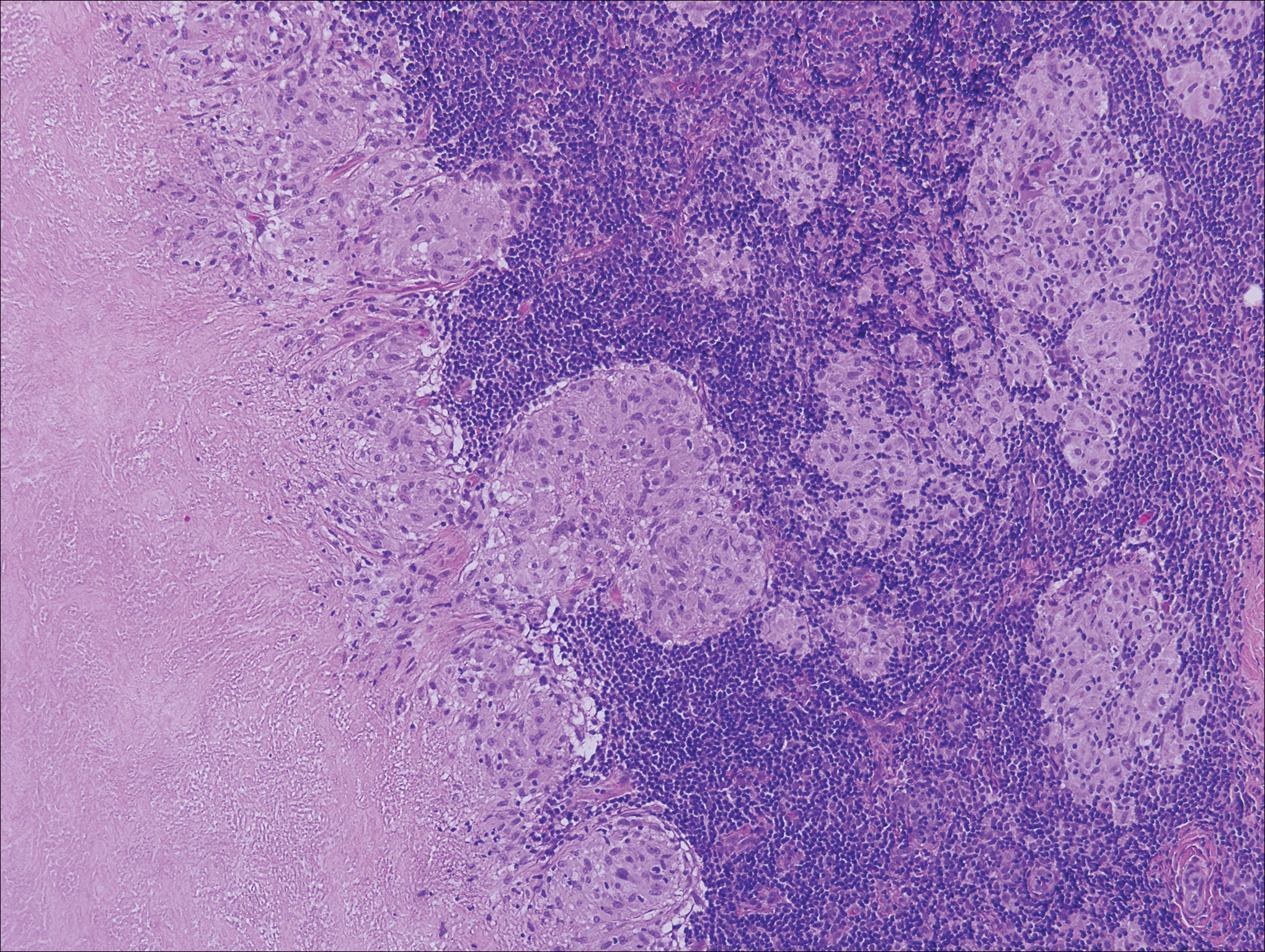

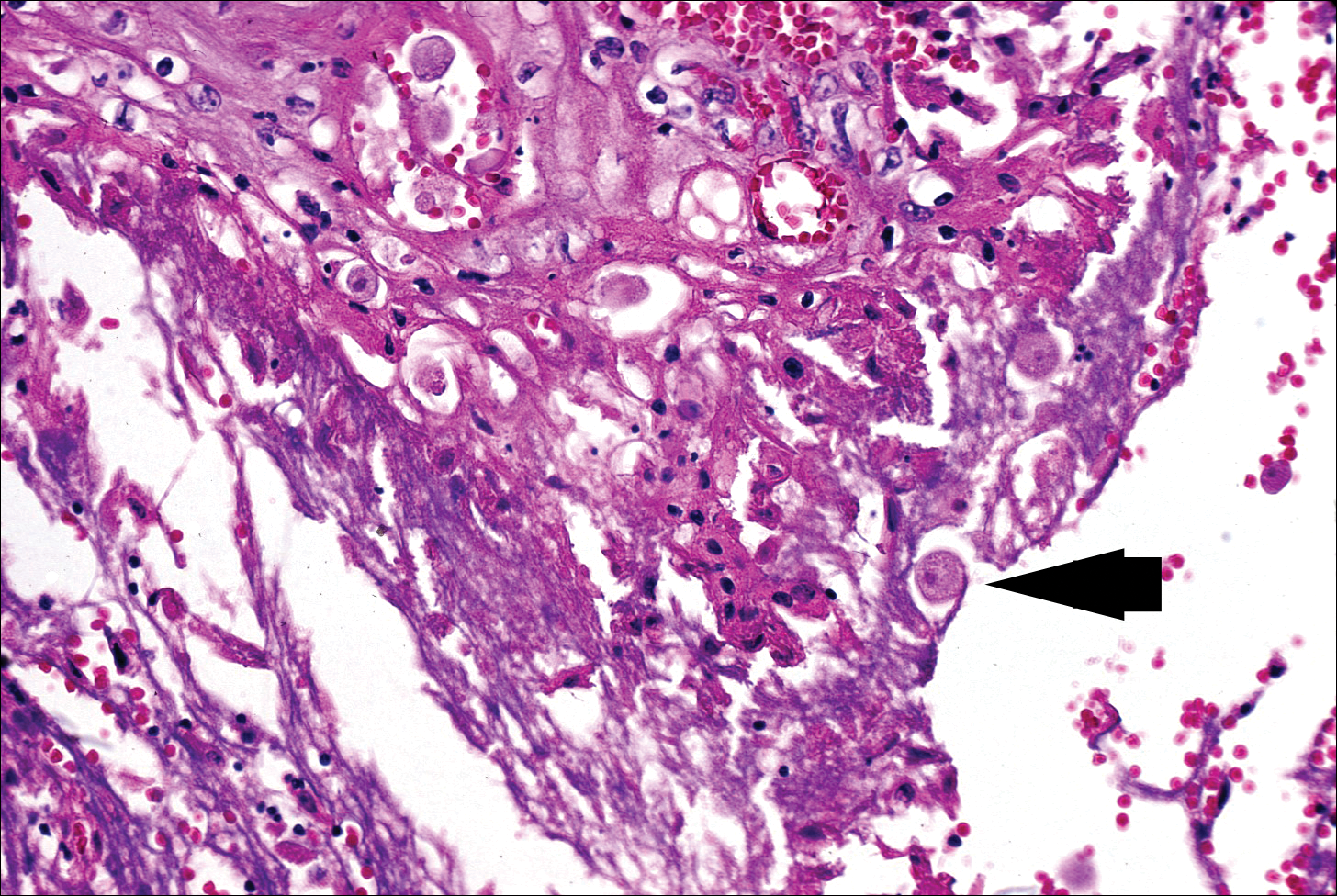

A 32-year-old woman presented to dermatology with a chief concern of a mass on the back of 2 years’ duration that rapidly enlarged and became painful following irritation from her bra strap 2 months earlier. She had no relevant medical history. Physical examination revealed a firm, tender, heterochromic nodule measuring 3.0×2.8 cm on the left mid back inferior to the left scapula (Figure 3). The lesion expressed serosanguineous discharge. No lymphadenopathy was appreciated on examination. The clinical differential diagnosis included an inflamed cyst, nodular melanoma, cutaneous metastasis, and nonmelanoma skin cancer. The patient underwent an excisional biopsy, which demonstrated porocarcinoma with positive margins, microsatellitosis, and evidence of lymphovascular invasion. Carcinoembryonic antigen immunohistochemistry highlighted ducts within the tumor (Figure 4). The patient underwent re-excision with 2-cm margins, and no residual tumor was appreciated on pathology.

Positron emission tomography and computed tomography revealed a hypermetabolic left axillary lymph node. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration was positive for malignant cells consistent with metastatic carcinoma. Dissection of left axillary lymph nodes yielded metastatic porocarcinoma in 2 of 13 nodes. The largest tumor deposit measured 0.9 cm, and no extracapsular extension was identified. The patient continues to be monitored with semiannual full-body skin examinations as well as positron emission tomography and computed tomography scans, with no evidence of recurrence 2 years later.

Porocarcinoma is a rare malignancy of the skin arising from the eccrine sweat glands1 with an incidence rate of 0.4 cases per 1 million person-years in the United States. These tumors represent 0.005% to 0.01% of all skin cancers.2 The mean age of onset is approximately 65 years with no predilection for sex. The mean time from initial presentation to treatment is 5.6 to 8.5 years.3-5

Eccrine sweat glands consist of a straight intradermal duct (syrinx); coiled intradermal duct; and spiral intraepidermal duct (acrosyringium), which opens onto the skin. Both eccrine poromas (solitary benign eccrine gland tumors) and eccrine porocarcinomas develop from the acrosyringium. Eccrine poromas most commonly are found in sites containing the highest density of eccrine glands such as the palms, soles, axillae, and forehead, whereas porocarcinomas most commonly are found on the head, neck, arms, and legs.1,3,4,6,7 A solitary painless nodule that may ulcerate or bleed is the most common presentation.1,3-5,7

The etiology of eccrine porocarcinoma is poorly understood, but it has been found to arise de novo or to develop from pre-existing poromas or even from nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Chronic sunlight exposure, irradiation, lymphedema, trauma, and immunosuppression (eg, Hodgkin disease, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, HIV) have been reported as potential predisposing factors.3,4,6,8,9

Eccrine porocarcinoma often is clinically misdiagnosed as nonmelanoma skin cancer, pyogenic granuloma, amelanotic melanoma, fibroma, verruca vulgaris, or metastatic carcinoma. Appropriate classification is essential, as metastasis is present in 25% to 31% of cases, and local recurrence occurs in 20% to 25% of cases.1,3-5,7

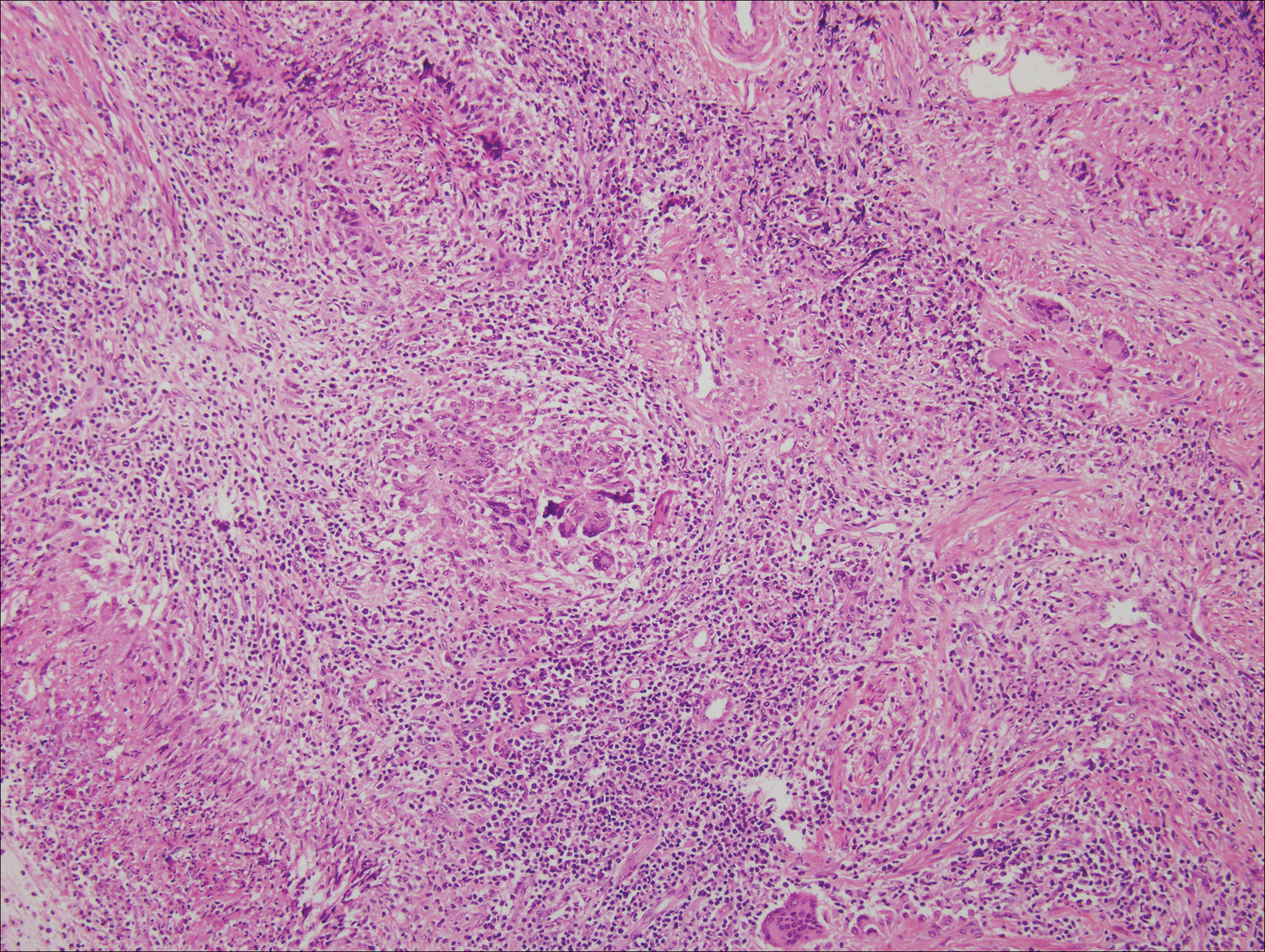

Microscopically, porocarcinomas are comprised of atypical basaloid epithelial cells with focal ductular differentiation. Typically, there is an extensive intraepidermal component that invades into the dermis in anastomosing ribbons and cords. The degree of nuclear atypia, mitotic activity, and invasive growth pattern, as well as the presence of necrosis, are useful histologic features to differentiate porocarcinoma from poroma, which may be present in the background. Given the sometimes-extensive squamous differentiation, porocarcinoma can be confused with squamous cell carcinoma. In these cases, immunohistochemical stains such as epithelial membrane antigen or carcinoembryonic antigen can be used to highlight the ductal differentiation.1,5,8,10

Poor histologic prognostic indicators include a high mitotic index (>14 mitoses per field), a tumor depth greater than 7 mm, and evidence of lymphovascular invasion. Positive lymph node involvement is associated with a 65% to 67% mortality rate.1,8

Because of its propensity to metastasize via the lymphatic system and the high mortality rate associated with such metastases, early identification and treatment are essential. Treatment is accomplished via Mohs micrographic surgery or wide local excision with negative margins. Lymphadenectomy is indicated if regional lymph nodes are involved. Radiation and chemotherapy have been used in patients with metastatic and recurrent disease with mixed results.1,3-5,7 There is no adequate standardized chemotherapy or drug regimen established for porocarcinoma.5 Tsunoda et al11 proposed that sentinel lymph node biopsy should be considered first-line management of eccrine porocarcinoma; however, this remains unproven on the basis of a limited case series. Others conclude that sentinel lymph node biopsy should be recommended for cases with poor histologic prognostic features.1,5

- Marone U, Caraco C, Anniciello AM, et al. Metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma: report of a case and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:32.

- Blake PW, Bradford PT, Devesa SS, et al. Cutaneous appendageal carcinoma incidence and survival patterns in the United States: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:625-632.

- Salih AM, Kakamad FH, Baba HO, et al. Porocarcinoma; presentation and management, a meta-analysis of 453 cases. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2017;20:74-79.

- Ritter AM, Graham RS, Amaker B, et al. Intracranial extension of an eccrine porocarcinoma. case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:138-140.

- Khaja M, Ashraf U, Mehershahi S, et al. Recurrent metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Case Rep. 2019;20:179-183.

- Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: a review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignant forms. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1053-1061.

- Lloyd MS, El-Muttardi N, Robson A. Eccrine porocarcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2003;11:153-156.

- Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720.

- Tarkhan II, Domingo J. Metastasizing eccrine porocarcinoma developing in a sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn. report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:413‐415.

- Prieto VG, Shea CR, Celebi JK, et al. Adnexal tumors. In: Busam KJ. Dermatopathology: A Volume in the Foundations in Diagnostic Pathology Series. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2016:388-446.

- Tsunoda K, Onishi M, Maeda F, et al. Evaluation of sentinel lymph node biopsy for eccrine porocarcinoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:691-692.

To the Editor:

Porocarcinoma is a rare malignancy of the eccrine sweat glands and is commonly misdiagnosed clinically. We present 2 cases of porocarcinoma and highlight key features of this uncommon disease.

A 65-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a chief concern of a bump on the head of 8 months' duration that gradually enlarged. The lesion recently became painful and contributed to frequent headaches. He reported a history of smoking 1 pack per day and denied trauma to the area or history of immunosuppression. He had no personal or family history of skin cancer. Physical examination revealed a 1.4-cm, heterochromic, pedunculated, keratotic tumor with crusting on the right temporal scalp (Figure 1). No lymphadenopathy was appreciated. The clinical differential diagnosis included irritated seborrheic keratosis, pyogenic granuloma, polypoid malignant melanoma, and nonmelanoma skin cancer. A biopsy of the lesion demonstrated a proliferation of cuboidal cells with focal ductular differentiation arranged in interanastamosing strands arising from the epidermis (Figure 2). Scattered mitotic figures, including atypical forms, cytologic atypia, and foci of necrosis, also were present. The findings were consistent with features of porocarcinoma. Contrast computed tomography of the neck showed no evidence of metastatic disease within the neck. A wide local excision was performed and yielded a tumor measuring 1.8×1.6×0.7 cm with a depth of 0.3 cm and uninvolved margins. No lymphovascular or perineural invasion was identified. At 4-month follow-up, the patient had a well-healed scar on the right scalp without evidence of recurrence or lymphadenopathy.

A 32-year-old woman presented to dermatology with a chief concern of a mass on the back of 2 years’ duration that rapidly enlarged and became painful following irritation from her bra strap 2 months earlier. She had no relevant medical history. Physical examination revealed a firm, tender, heterochromic nodule measuring 3.0×2.8 cm on the left mid back inferior to the left scapula (Figure 3). The lesion expressed serosanguineous discharge. No lymphadenopathy was appreciated on examination. The clinical differential diagnosis included an inflamed cyst, nodular melanoma, cutaneous metastasis, and nonmelanoma skin cancer. The patient underwent an excisional biopsy, which demonstrated porocarcinoma with positive margins, microsatellitosis, and evidence of lymphovascular invasion. Carcinoembryonic antigen immunohistochemistry highlighted ducts within the tumor (Figure 4). The patient underwent re-excision with 2-cm margins, and no residual tumor was appreciated on pathology.

Positron emission tomography and computed tomography revealed a hypermetabolic left axillary lymph node. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration was positive for malignant cells consistent with metastatic carcinoma. Dissection of left axillary lymph nodes yielded metastatic porocarcinoma in 2 of 13 nodes. The largest tumor deposit measured 0.9 cm, and no extracapsular extension was identified. The patient continues to be monitored with semiannual full-body skin examinations as well as positron emission tomography and computed tomography scans, with no evidence of recurrence 2 years later.

Porocarcinoma is a rare malignancy of the skin arising from the eccrine sweat glands1 with an incidence rate of 0.4 cases per 1 million person-years in the United States. These tumors represent 0.005% to 0.01% of all skin cancers.2 The mean age of onset is approximately 65 years with no predilection for sex. The mean time from initial presentation to treatment is 5.6 to 8.5 years.3-5

Eccrine sweat glands consist of a straight intradermal duct (syrinx); coiled intradermal duct; and spiral intraepidermal duct (acrosyringium), which opens onto the skin. Both eccrine poromas (solitary benign eccrine gland tumors) and eccrine porocarcinomas develop from the acrosyringium. Eccrine poromas most commonly are found in sites containing the highest density of eccrine glands such as the palms, soles, axillae, and forehead, whereas porocarcinomas most commonly are found on the head, neck, arms, and legs.1,3,4,6,7 A solitary painless nodule that may ulcerate or bleed is the most common presentation.1,3-5,7

The etiology of eccrine porocarcinoma is poorly understood, but it has been found to arise de novo or to develop from pre-existing poromas or even from nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Chronic sunlight exposure, irradiation, lymphedema, trauma, and immunosuppression (eg, Hodgkin disease, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, HIV) have been reported as potential predisposing factors.3,4,6,8,9

Eccrine porocarcinoma often is clinically misdiagnosed as nonmelanoma skin cancer, pyogenic granuloma, amelanotic melanoma, fibroma, verruca vulgaris, or metastatic carcinoma. Appropriate classification is essential, as metastasis is present in 25% to 31% of cases, and local recurrence occurs in 20% to 25% of cases.1,3-5,7

Microscopically, porocarcinomas are comprised of atypical basaloid epithelial cells with focal ductular differentiation. Typically, there is an extensive intraepidermal component that invades into the dermis in anastomosing ribbons and cords. The degree of nuclear atypia, mitotic activity, and invasive growth pattern, as well as the presence of necrosis, are useful histologic features to differentiate porocarcinoma from poroma, which may be present in the background. Given the sometimes-extensive squamous differentiation, porocarcinoma can be confused with squamous cell carcinoma. In these cases, immunohistochemical stains such as epithelial membrane antigen or carcinoembryonic antigen can be used to highlight the ductal differentiation.1,5,8,10

Poor histologic prognostic indicators include a high mitotic index (>14 mitoses per field), a tumor depth greater than 7 mm, and evidence of lymphovascular invasion. Positive lymph node involvement is associated with a 65% to 67% mortality rate.1,8

Because of its propensity to metastasize via the lymphatic system and the high mortality rate associated with such metastases, early identification and treatment are essential. Treatment is accomplished via Mohs micrographic surgery or wide local excision with negative margins. Lymphadenectomy is indicated if regional lymph nodes are involved. Radiation and chemotherapy have been used in patients with metastatic and recurrent disease with mixed results.1,3-5,7 There is no adequate standardized chemotherapy or drug regimen established for porocarcinoma.5 Tsunoda et al11 proposed that sentinel lymph node biopsy should be considered first-line management of eccrine porocarcinoma; however, this remains unproven on the basis of a limited case series. Others conclude that sentinel lymph node biopsy should be recommended for cases with poor histologic prognostic features.1,5

To the Editor:

Porocarcinoma is a rare malignancy of the eccrine sweat glands and is commonly misdiagnosed clinically. We present 2 cases of porocarcinoma and highlight key features of this uncommon disease.

A 65-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a chief concern of a bump on the head of 8 months' duration that gradually enlarged. The lesion recently became painful and contributed to frequent headaches. He reported a history of smoking 1 pack per day and denied trauma to the area or history of immunosuppression. He had no personal or family history of skin cancer. Physical examination revealed a 1.4-cm, heterochromic, pedunculated, keratotic tumor with crusting on the right temporal scalp (Figure 1). No lymphadenopathy was appreciated. The clinical differential diagnosis included irritated seborrheic keratosis, pyogenic granuloma, polypoid malignant melanoma, and nonmelanoma skin cancer. A biopsy of the lesion demonstrated a proliferation of cuboidal cells with focal ductular differentiation arranged in interanastamosing strands arising from the epidermis (Figure 2). Scattered mitotic figures, including atypical forms, cytologic atypia, and foci of necrosis, also were present. The findings were consistent with features of porocarcinoma. Contrast computed tomography of the neck showed no evidence of metastatic disease within the neck. A wide local excision was performed and yielded a tumor measuring 1.8×1.6×0.7 cm with a depth of 0.3 cm and uninvolved margins. No lymphovascular or perineural invasion was identified. At 4-month follow-up, the patient had a well-healed scar on the right scalp without evidence of recurrence or lymphadenopathy.

A 32-year-old woman presented to dermatology with a chief concern of a mass on the back of 2 years’ duration that rapidly enlarged and became painful following irritation from her bra strap 2 months earlier. She had no relevant medical history. Physical examination revealed a firm, tender, heterochromic nodule measuring 3.0×2.8 cm on the left mid back inferior to the left scapula (Figure 3). The lesion expressed serosanguineous discharge. No lymphadenopathy was appreciated on examination. The clinical differential diagnosis included an inflamed cyst, nodular melanoma, cutaneous metastasis, and nonmelanoma skin cancer. The patient underwent an excisional biopsy, which demonstrated porocarcinoma with positive margins, microsatellitosis, and evidence of lymphovascular invasion. Carcinoembryonic antigen immunohistochemistry highlighted ducts within the tumor (Figure 4). The patient underwent re-excision with 2-cm margins, and no residual tumor was appreciated on pathology.

Positron emission tomography and computed tomography revealed a hypermetabolic left axillary lymph node. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration was positive for malignant cells consistent with metastatic carcinoma. Dissection of left axillary lymph nodes yielded metastatic porocarcinoma in 2 of 13 nodes. The largest tumor deposit measured 0.9 cm, and no extracapsular extension was identified. The patient continues to be monitored with semiannual full-body skin examinations as well as positron emission tomography and computed tomography scans, with no evidence of recurrence 2 years later.

Porocarcinoma is a rare malignancy of the skin arising from the eccrine sweat glands1 with an incidence rate of 0.4 cases per 1 million person-years in the United States. These tumors represent 0.005% to 0.01% of all skin cancers.2 The mean age of onset is approximately 65 years with no predilection for sex. The mean time from initial presentation to treatment is 5.6 to 8.5 years.3-5

Eccrine sweat glands consist of a straight intradermal duct (syrinx); coiled intradermal duct; and spiral intraepidermal duct (acrosyringium), which opens onto the skin. Both eccrine poromas (solitary benign eccrine gland tumors) and eccrine porocarcinomas develop from the acrosyringium. Eccrine poromas most commonly are found in sites containing the highest density of eccrine glands such as the palms, soles, axillae, and forehead, whereas porocarcinomas most commonly are found on the head, neck, arms, and legs.1,3,4,6,7 A solitary painless nodule that may ulcerate or bleed is the most common presentation.1,3-5,7

The etiology of eccrine porocarcinoma is poorly understood, but it has been found to arise de novo or to develop from pre-existing poromas or even from nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Chronic sunlight exposure, irradiation, lymphedema, trauma, and immunosuppression (eg, Hodgkin disease, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, HIV) have been reported as potential predisposing factors.3,4,6,8,9

Eccrine porocarcinoma often is clinically misdiagnosed as nonmelanoma skin cancer, pyogenic granuloma, amelanotic melanoma, fibroma, verruca vulgaris, or metastatic carcinoma. Appropriate classification is essential, as metastasis is present in 25% to 31% of cases, and local recurrence occurs in 20% to 25% of cases.1,3-5,7

Microscopically, porocarcinomas are comprised of atypical basaloid epithelial cells with focal ductular differentiation. Typically, there is an extensive intraepidermal component that invades into the dermis in anastomosing ribbons and cords. The degree of nuclear atypia, mitotic activity, and invasive growth pattern, as well as the presence of necrosis, are useful histologic features to differentiate porocarcinoma from poroma, which may be present in the background. Given the sometimes-extensive squamous differentiation, porocarcinoma can be confused with squamous cell carcinoma. In these cases, immunohistochemical stains such as epithelial membrane antigen or carcinoembryonic antigen can be used to highlight the ductal differentiation.1,5,8,10

Poor histologic prognostic indicators include a high mitotic index (>14 mitoses per field), a tumor depth greater than 7 mm, and evidence of lymphovascular invasion. Positive lymph node involvement is associated with a 65% to 67% mortality rate.1,8

Because of its propensity to metastasize via the lymphatic system and the high mortality rate associated with such metastases, early identification and treatment are essential. Treatment is accomplished via Mohs micrographic surgery or wide local excision with negative margins. Lymphadenectomy is indicated if regional lymph nodes are involved. Radiation and chemotherapy have been used in patients with metastatic and recurrent disease with mixed results.1,3-5,7 There is no adequate standardized chemotherapy or drug regimen established for porocarcinoma.5 Tsunoda et al11 proposed that sentinel lymph node biopsy should be considered first-line management of eccrine porocarcinoma; however, this remains unproven on the basis of a limited case series. Others conclude that sentinel lymph node biopsy should be recommended for cases with poor histologic prognostic features.1,5

- Marone U, Caraco C, Anniciello AM, et al. Metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma: report of a case and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:32.

- Blake PW, Bradford PT, Devesa SS, et al. Cutaneous appendageal carcinoma incidence and survival patterns in the United States: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:625-632.

- Salih AM, Kakamad FH, Baba HO, et al. Porocarcinoma; presentation and management, a meta-analysis of 453 cases. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2017;20:74-79.

- Ritter AM, Graham RS, Amaker B, et al. Intracranial extension of an eccrine porocarcinoma. case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:138-140.

- Khaja M, Ashraf U, Mehershahi S, et al. Recurrent metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Case Rep. 2019;20:179-183.

- Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: a review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignant forms. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1053-1061.

- Lloyd MS, El-Muttardi N, Robson A. Eccrine porocarcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2003;11:153-156.

- Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720.

- Tarkhan II, Domingo J. Metastasizing eccrine porocarcinoma developing in a sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn. report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:413‐415.

- Prieto VG, Shea CR, Celebi JK, et al. Adnexal tumors. In: Busam KJ. Dermatopathology: A Volume in the Foundations in Diagnostic Pathology Series. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2016:388-446.

- Tsunoda K, Onishi M, Maeda F, et al. Evaluation of sentinel lymph node biopsy for eccrine porocarcinoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:691-692.

- Marone U, Caraco C, Anniciello AM, et al. Metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma: report of a case and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:32.

- Blake PW, Bradford PT, Devesa SS, et al. Cutaneous appendageal carcinoma incidence and survival patterns in the United States: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:625-632.

- Salih AM, Kakamad FH, Baba HO, et al. Porocarcinoma; presentation and management, a meta-analysis of 453 cases. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2017;20:74-79.

- Ritter AM, Graham RS, Amaker B, et al. Intracranial extension of an eccrine porocarcinoma. case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:138-140.

- Khaja M, Ashraf U, Mehershahi S, et al. Recurrent metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Case Rep. 2019;20:179-183.

- Sawaya JL, Khachemoune A. Poroma: a review of eccrine, apocrine, and malignant forms. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1053-1061.

- Lloyd MS, El-Muttardi N, Robson A. Eccrine porocarcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2003;11:153-156.

- Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720.

- Tarkhan II, Domingo J. Metastasizing eccrine porocarcinoma developing in a sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn. report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:413‐415.

- Prieto VG, Shea CR, Celebi JK, et al. Adnexal tumors. In: Busam KJ. Dermatopathology: A Volume in the Foundations in Diagnostic Pathology Series. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2016:388-446.

- Tsunoda K, Onishi M, Maeda F, et al. Evaluation of sentinel lymph node biopsy for eccrine porocarcinoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:691-692.

Practice Points

- Eccrine porocarcinoma is a rare malignancy that clinically mimics other cutaneous malignancies.

- Early histologic diagnosis is essential, as lymphatic metastasis is common and carries a 65% to 67% mortality rate.

Progressive Telangiectatic Rash

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an idiopathic microangiopathy of the small vessels in the superficial dermis. A condition first identified by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000, CCV likely is underreported, as its clinical mimickers are not routinely biopsied.2 It presents as asymptomatic telangiectatic macules, initially on the lower extremities and often spreading to the trunk. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy often is seen in middle-aged adults, and most patients have comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or cardiovascular disease. The exact etiology of this disease is unknown.3,4

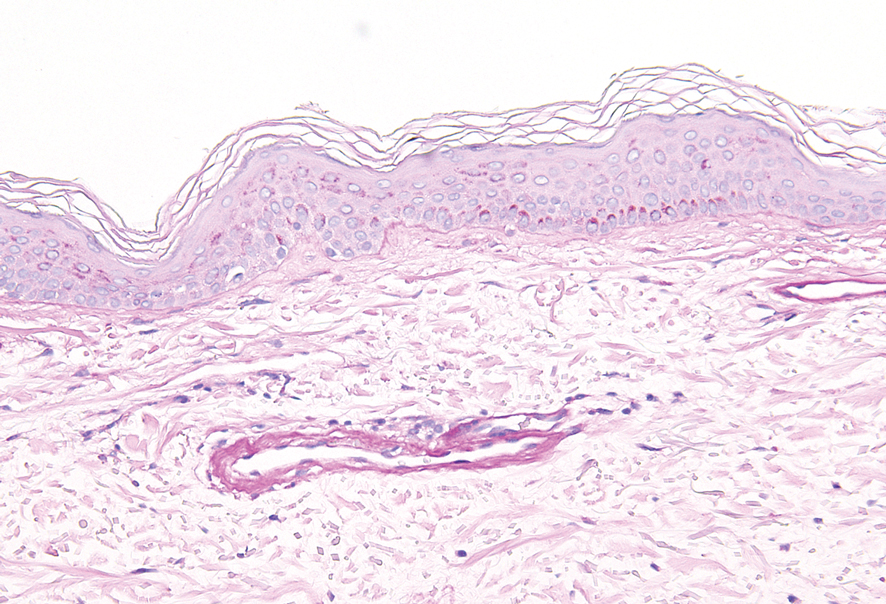

Histopathologically, CCV is characterized by dilated superficial vessels with thickened eosinophilic walls. The eosinophilic material is composed of hyalinized type IV collagen, which is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 1).3,4 Stains for amyloid are negative.

Generalized essential telangiectasia (GET) is a condition that presents with symmetric, blanchable, erythematous telangiectases.5 These lesions can occur alone or can accompany systemic diseases. Similar to CCV, the telangiectases tend to begin on the legs before gradually spreading to the trunk; however, this process more often is seen in females and occurs at an earlier age. Unlike CCV, GET can occur on mucosal surfaces, with cases of conjunctival and oral involvement reported.6 Generalized essential telangiectasia usually is a diagnosis of exclusion.7,8 It is thought that many CCV lesions have been misclassified clinically as GET, which highlights the importance of biopsy. Microscopically, GET is distinct from CCV in that the superficial dermis lacks thick-walled vessels.5,7 Although usually not associated with systemic diseases or progressive morbidity, treatment options are limited.8

Livedoid vasculopathy, also known as atrophie blanche, is caused by fibrin thrombi occlusion of dermal vessels. Clinically, patients have recurrent telangiectatic papules and painful ulcers on the lower extremities that gradually heal, leaving behind white stellate scars. It is caused by an underlying prothrombotic state with a superimposed inflammatory response.9 Livedoid vasculopathy primarily affects middle-aged women, and many patients have comorbidities such as scleroderma or systemic lupus erythematosus. Histologically, the epidermis often is ulcerated, and thrombi are visualized within small vessels. Eosinophilic fibrinoid material is deposited in vessel walls, including but not confined to vessels at the base of the epidermal ulcer (Figure 2). The fibrinoid material is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant and can be highlighted with immunofluorescence, which may help to distinguish this entity from CCV.1,9 As the disease progresses, vessels are diffusely hyalinized, and there is epidermal atrophy and dermal sclerosis. Treatment options include antiplatelet and fibrinolytic drugs with a multidisciplinary approach to resolve pain and scarring.9

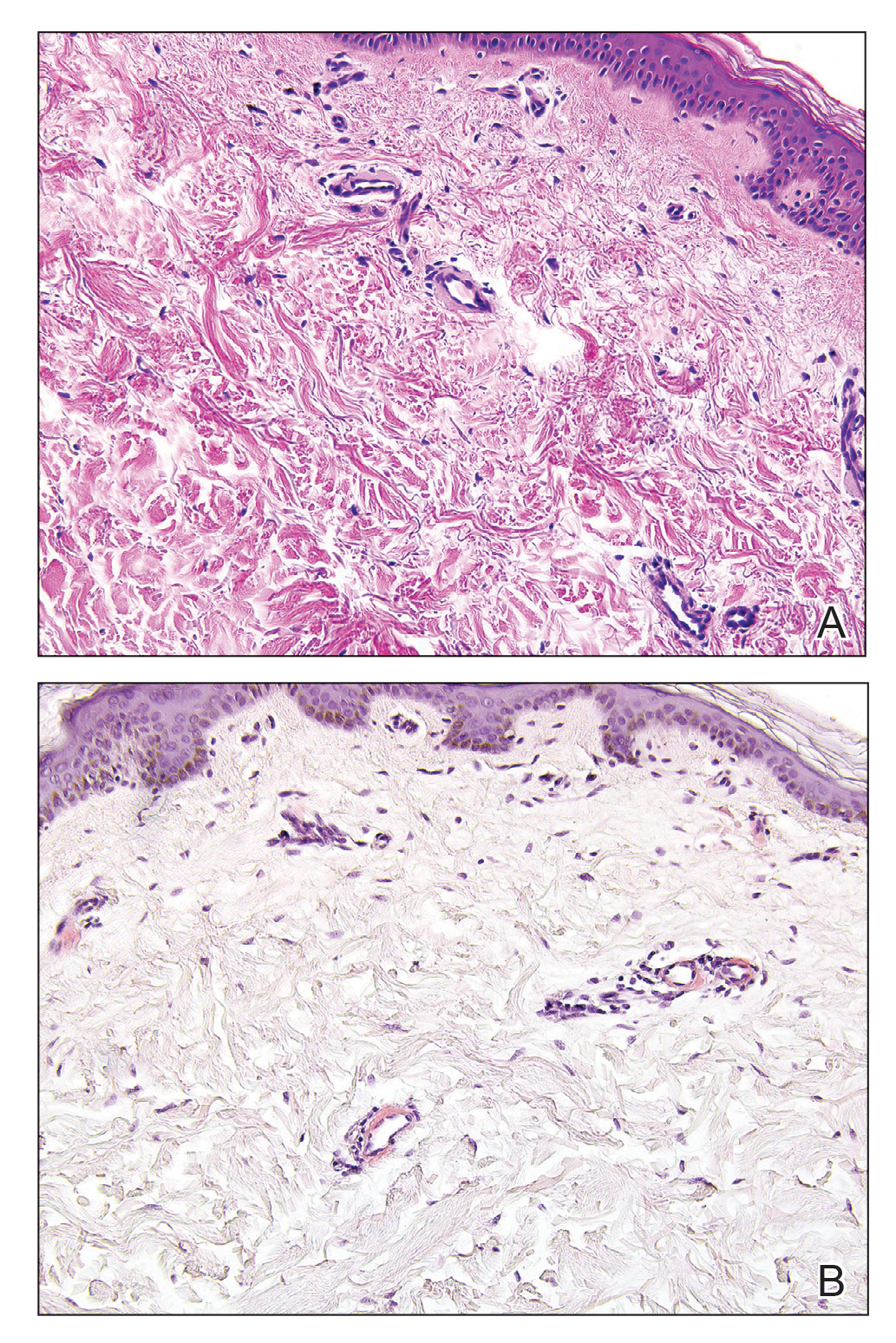

Primary systemic amyloidosis is a rare condition, and cutaneous manifestations are seen in approximately one-third of affected individuals. Amyloid deposition results in waxy papules that predominantly affect the face and periorbital areas but also may occur on the neck, flexural areas, and genitalia.5 Because the amyloid deposits also can be found within vessel walls, hemorrhagic lesions may occur. Microscopically, amorphous eosinophilic material can be found within the vessel walls, similar to CCV (Figure 3A); however, when stained with Congo red, cutaneous amyloidosis shows waxy red-orange material involving the vessel walls and exhibits apple green birefringence under polarization (Figure 3B).10 Amyloid also will be negative for type IV collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, whereas CCV will be positive.5

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Bondier L, Tardieu M, Leveque P, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of two cases presenting as disseminated telangiectasias and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:682-688.

- Sartori DS, Almeida HL Jr, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52.

- Patterson JW, ed. Vascular tumors. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016:1069-1115.

- Knöpfel N, Martín-Santiago A, Saus C, et al. Extensive acquired telangiectasias: comparison of generalized essential telangiectasia and cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:E21-E26.

- Karimkhani C, Boyers LN, Olivere J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Cutis. 2019;103:E7-E8.

- McGrae JD, Winkelmann RK. Generalized essential telangiectasia: report of a clinical and histochemical study of 13 patients with acquired cutaneous lesions. JAMA. 1963;185:909-913.

- Vasudeva B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478.

- Ko CJ, Barr RJ. Color--pink. In: Ko CJ, Barr RJ, eds. Dermatopathology: Diagnosis by First Impression. 3rd ed. Wiley; 2016:303-322.

- Clark ML, McGuinness AE, Vidal CI. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a unique case with positive direct immunofluorescence findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:77-79.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an idiopathic microangiopathy of the small vessels in the superficial dermis. A condition first identified by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000, CCV likely is underreported, as its clinical mimickers are not routinely biopsied.2 It presents as asymptomatic telangiectatic macules, initially on the lower extremities and often spreading to the trunk. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy often is seen in middle-aged adults, and most patients have comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or cardiovascular disease. The exact etiology of this disease is unknown.3,4

Histopathologically, CCV is characterized by dilated superficial vessels with thickened eosinophilic walls. The eosinophilic material is composed of hyalinized type IV collagen, which is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 1).3,4 Stains for amyloid are negative.

Generalized essential telangiectasia (GET) is a condition that presents with symmetric, blanchable, erythematous telangiectases.5 These lesions can occur alone or can accompany systemic diseases. Similar to CCV, the telangiectases tend to begin on the legs before gradually spreading to the trunk; however, this process more often is seen in females and occurs at an earlier age. Unlike CCV, GET can occur on mucosal surfaces, with cases of conjunctival and oral involvement reported.6 Generalized essential telangiectasia usually is a diagnosis of exclusion.7,8 It is thought that many CCV lesions have been misclassified clinically as GET, which highlights the importance of biopsy. Microscopically, GET is distinct from CCV in that the superficial dermis lacks thick-walled vessels.5,7 Although usually not associated with systemic diseases or progressive morbidity, treatment options are limited.8

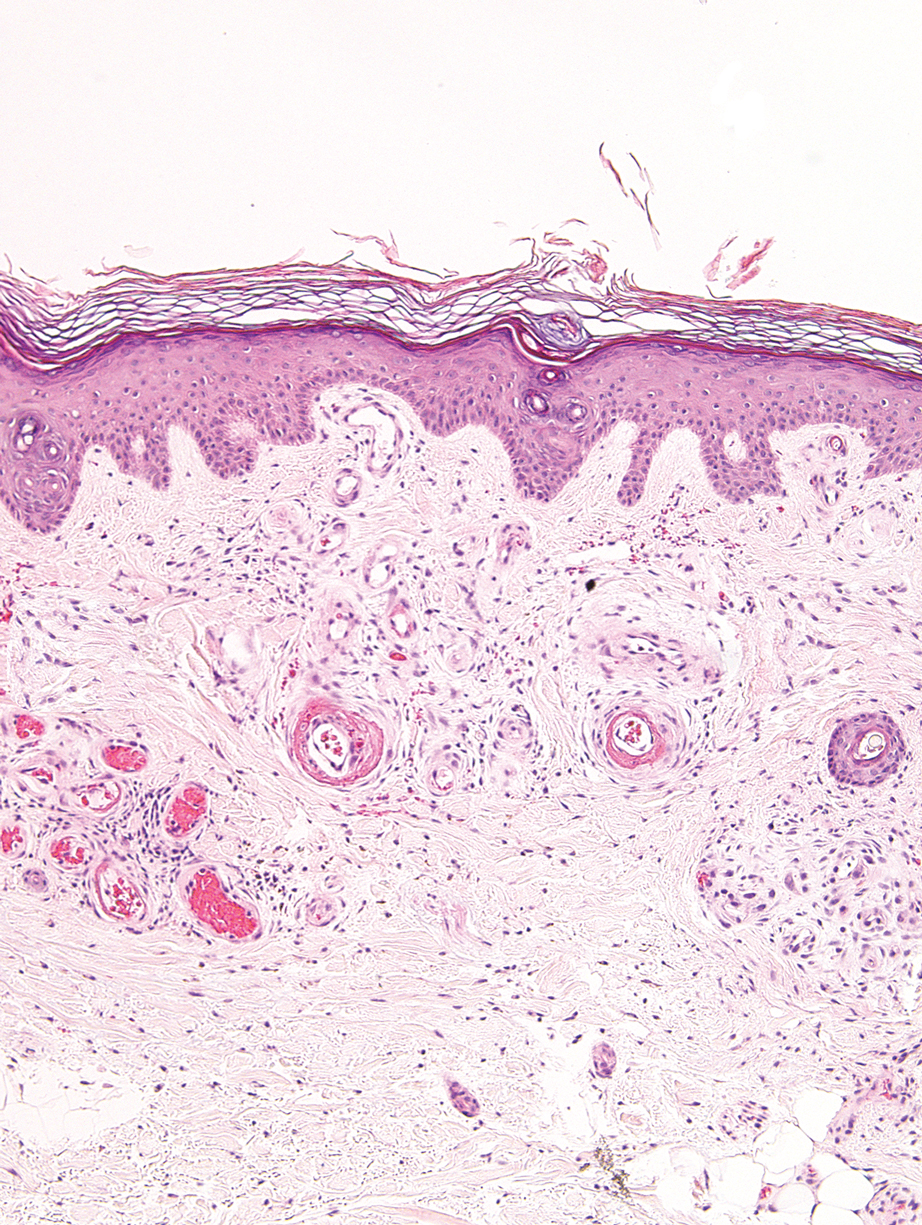

Livedoid vasculopathy, also known as atrophie blanche, is caused by fibrin thrombi occlusion of dermal vessels. Clinically, patients have recurrent telangiectatic papules and painful ulcers on the lower extremities that gradually heal, leaving behind white stellate scars. It is caused by an underlying prothrombotic state with a superimposed inflammatory response.9 Livedoid vasculopathy primarily affects middle-aged women, and many patients have comorbidities such as scleroderma or systemic lupus erythematosus. Histologically, the epidermis often is ulcerated, and thrombi are visualized within small vessels. Eosinophilic fibrinoid material is deposited in vessel walls, including but not confined to vessels at the base of the epidermal ulcer (Figure 2). The fibrinoid material is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant and can be highlighted with immunofluorescence, which may help to distinguish this entity from CCV.1,9 As the disease progresses, vessels are diffusely hyalinized, and there is epidermal atrophy and dermal sclerosis. Treatment options include antiplatelet and fibrinolytic drugs with a multidisciplinary approach to resolve pain and scarring.9

Primary systemic amyloidosis is a rare condition, and cutaneous manifestations are seen in approximately one-third of affected individuals. Amyloid deposition results in waxy papules that predominantly affect the face and periorbital areas but also may occur on the neck, flexural areas, and genitalia.5 Because the amyloid deposits also can be found within vessel walls, hemorrhagic lesions may occur. Microscopically, amorphous eosinophilic material can be found within the vessel walls, similar to CCV (Figure 3A); however, when stained with Congo red, cutaneous amyloidosis shows waxy red-orange material involving the vessel walls and exhibits apple green birefringence under polarization (Figure 3B).10 Amyloid also will be negative for type IV collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, whereas CCV will be positive.5

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an idiopathic microangiopathy of the small vessels in the superficial dermis. A condition first identified by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000, CCV likely is underreported, as its clinical mimickers are not routinely biopsied.2 It presents as asymptomatic telangiectatic macules, initially on the lower extremities and often spreading to the trunk. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy often is seen in middle-aged adults, and most patients have comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or cardiovascular disease. The exact etiology of this disease is unknown.3,4

Histopathologically, CCV is characterized by dilated superficial vessels with thickened eosinophilic walls. The eosinophilic material is composed of hyalinized type IV collagen, which is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 1).3,4 Stains for amyloid are negative.

Generalized essential telangiectasia (GET) is a condition that presents with symmetric, blanchable, erythematous telangiectases.5 These lesions can occur alone or can accompany systemic diseases. Similar to CCV, the telangiectases tend to begin on the legs before gradually spreading to the trunk; however, this process more often is seen in females and occurs at an earlier age. Unlike CCV, GET can occur on mucosal surfaces, with cases of conjunctival and oral involvement reported.6 Generalized essential telangiectasia usually is a diagnosis of exclusion.7,8 It is thought that many CCV lesions have been misclassified clinically as GET, which highlights the importance of biopsy. Microscopically, GET is distinct from CCV in that the superficial dermis lacks thick-walled vessels.5,7 Although usually not associated with systemic diseases or progressive morbidity, treatment options are limited.8

Livedoid vasculopathy, also known as atrophie blanche, is caused by fibrin thrombi occlusion of dermal vessels. Clinically, patients have recurrent telangiectatic papules and painful ulcers on the lower extremities that gradually heal, leaving behind white stellate scars. It is caused by an underlying prothrombotic state with a superimposed inflammatory response.9 Livedoid vasculopathy primarily affects middle-aged women, and many patients have comorbidities such as scleroderma or systemic lupus erythematosus. Histologically, the epidermis often is ulcerated, and thrombi are visualized within small vessels. Eosinophilic fibrinoid material is deposited in vessel walls, including but not confined to vessels at the base of the epidermal ulcer (Figure 2). The fibrinoid material is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant and can be highlighted with immunofluorescence, which may help to distinguish this entity from CCV.1,9 As the disease progresses, vessels are diffusely hyalinized, and there is epidermal atrophy and dermal sclerosis. Treatment options include antiplatelet and fibrinolytic drugs with a multidisciplinary approach to resolve pain and scarring.9

Primary systemic amyloidosis is a rare condition, and cutaneous manifestations are seen in approximately one-third of affected individuals. Amyloid deposition results in waxy papules that predominantly affect the face and periorbital areas but also may occur on the neck, flexural areas, and genitalia.5 Because the amyloid deposits also can be found within vessel walls, hemorrhagic lesions may occur. Microscopically, amorphous eosinophilic material can be found within the vessel walls, similar to CCV (Figure 3A); however, when stained with Congo red, cutaneous amyloidosis shows waxy red-orange material involving the vessel walls and exhibits apple green birefringence under polarization (Figure 3B).10 Amyloid also will be negative for type IV collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, whereas CCV will be positive.5

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Bondier L, Tardieu M, Leveque P, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of two cases presenting as disseminated telangiectasias and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:682-688.

- Sartori DS, Almeida HL Jr, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52.

- Patterson JW, ed. Vascular tumors. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016:1069-1115.

- Knöpfel N, Martín-Santiago A, Saus C, et al. Extensive acquired telangiectasias: comparison of generalized essential telangiectasia and cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:E21-E26.

- Karimkhani C, Boyers LN, Olivere J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Cutis. 2019;103:E7-E8.

- McGrae JD, Winkelmann RK. Generalized essential telangiectasia: report of a clinical and histochemical study of 13 patients with acquired cutaneous lesions. JAMA. 1963;185:909-913.

- Vasudeva B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478.

- Ko CJ, Barr RJ. Color--pink. In: Ko CJ, Barr RJ, eds. Dermatopathology: Diagnosis by First Impression. 3rd ed. Wiley; 2016:303-322.

- Clark ML, McGuinness AE, Vidal CI. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a unique case with positive direct immunofluorescence findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:77-79.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Bondier L, Tardieu M, Leveque P, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of two cases presenting as disseminated telangiectasias and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:682-688.

- Sartori DS, Almeida HL Jr, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52.

- Patterson JW, ed. Vascular tumors. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016:1069-1115.

- Knöpfel N, Martín-Santiago A, Saus C, et al. Extensive acquired telangiectasias: comparison of generalized essential telangiectasia and cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:E21-E26.

- Karimkhani C, Boyers LN, Olivere J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Cutis. 2019;103:E7-E8.

- McGrae JD, Winkelmann RK. Generalized essential telangiectasia: report of a clinical and histochemical study of 13 patients with acquired cutaneous lesions. JAMA. 1963;185:909-913.

- Vasudeva B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478.

- Ko CJ, Barr RJ. Color--pink. In: Ko CJ, Barr RJ, eds. Dermatopathology: Diagnosis by First Impression. 3rd ed. Wiley; 2016:303-322.

- Clark ML, McGuinness AE, Vidal CI. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a unique case with positive direct immunofluorescence findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:77-79.

A 54-year-old woman presented with purple-red vessels on the lower legs of 15 years’ duration with gradual proximal progression to involve the thighs, breasts, and forearms. A punch biopsy of the inner thigh was obtained for histopathologic evaluation.

Tender White Lesions on the Groin

The Diagnosis: Candidal Intertrigo

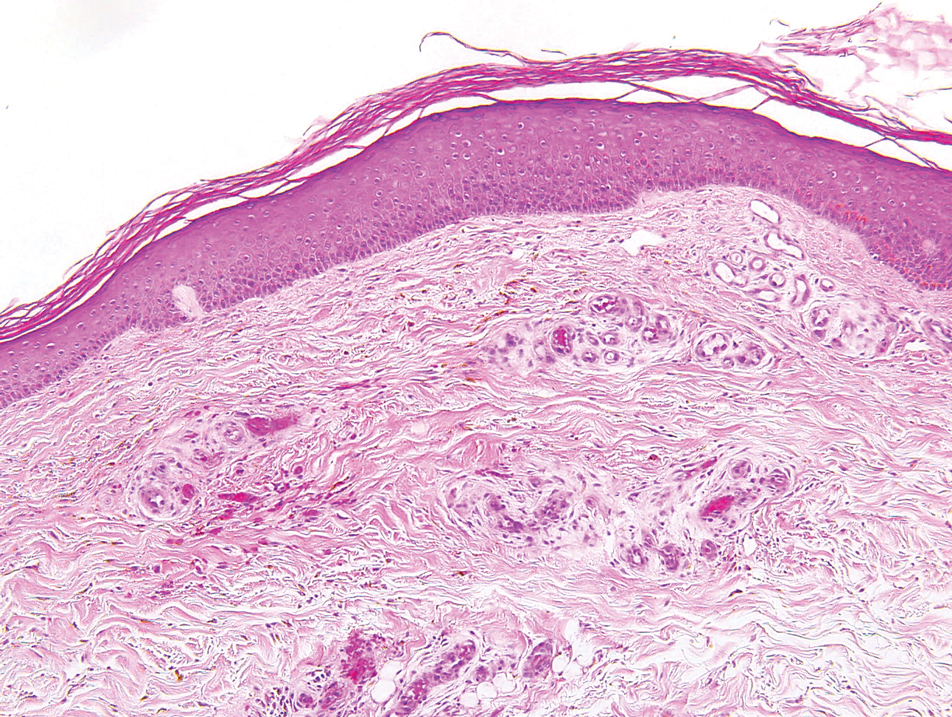

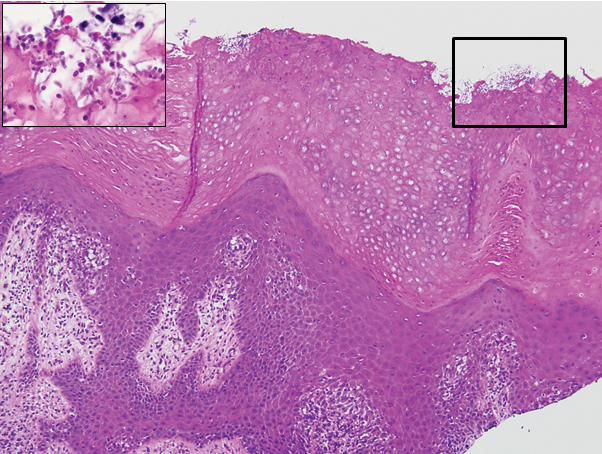

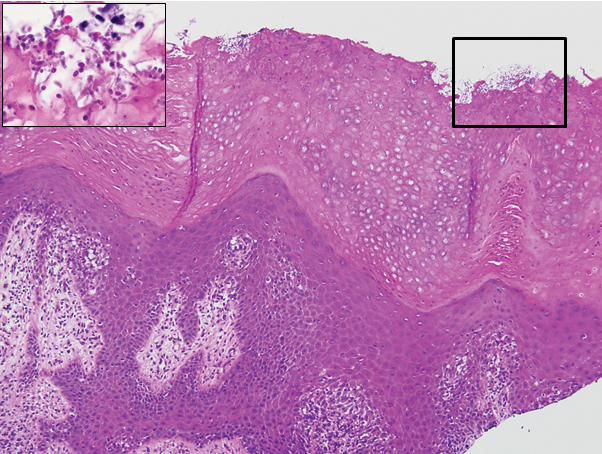

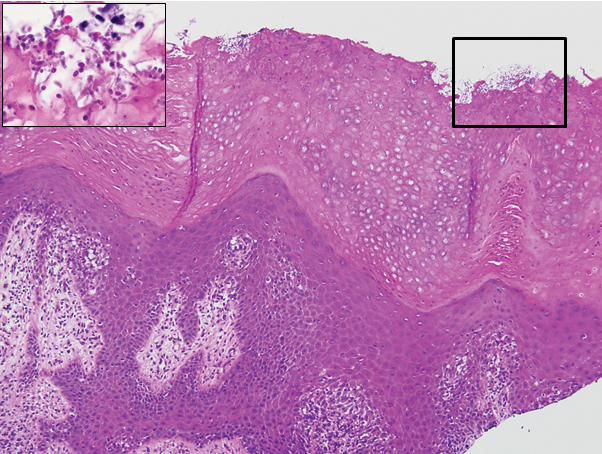

The biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of severe hyperkeratotic candidal intertrigo with no evidence of Hailey-Hailey disease. Hematoxylin and eosin- stained sections demonstrated irregular acanthosis and variable spongiosis. The stratum corneum was predominantly orthokeratotic with overlying psuedohyphae and yeast fungal elements (Figure 1).

Hyperimmunoglobulinemia E syndrome (HIES), also known as hyper-IgE syndrome or Job syndrome, is a rare immunodeficiency disorder characterized by an eczematous dermatitis-like rash, recurrent skin and lung abscesses, eosinophilia, and elevated serum IgE. Facial asymmetry, prominent forehead, deep-set eyes, broad nose, and roughened facial skin with large pores are characteristic of the sporadic and autosomal-recessive forms. Other common findings include retained primary teeth, hyperextensible joints, and recurrent mucocutaneous candidiasis.1

Although autosomal-dominant and autosomal-recessive inheritance patterns exist, sporadic mutations are the most common cause of HIES.2 Several genes have been implicated depending on the inheritance pattern. The majority of autosomal-dominant cases are associated with inactivating STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) mutations, whereas the majority of autosomal-recessive cases are associated with inactivating DOCK8 (dedicator of cytokinesis 8) mutations.1 Ultimately, all of these mutations lead to an impaired helper T cell (TH17) response, which is crucial for clearing fungal and extracellular bacterial infections.3

Skin eruptions typically are the first manifestation of HIES; they appear within the first week to month of life as papulopustular eruptions on the face and scalp and rapidly generalize to the rest of the body, favoring the shoulders, arms, chest, and buttocks. The pustules then coalesce into crusted plaques that resemble atopic dermatitis, frequently with superimposed Staphylococcus aureus infection. On microscopy, the pustules are folliculocentric and often contain eosinophils, whereas the plaques may contain intraepidermal collections of eosinophils.1

Mucocutaneous candidiasis is seen in approximately 60% of HIES cases and is closely linked to STAT3 inactivating mutations.3 Histologically, there is marked acanthosis with neutrophil exocytosis and abundant yeast and pseudohyphal forms within the stratum corneum (Figure 2).4 Cutaneous candidal infections typically require both oral and topical antifungal agents to clear the infection.3 Most cases of mucocutaneous candidiasis are caused by Candida albicans; however, other known culprits include Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida krusei.5,6 Of note, species identification and antifungal susceptibility studies may be useful in refractory cases, especially with C glabrata, which is known to acquire resistance to azoles, such as fluconazole, with emerging resistance to echinocandins.6

The differential diagnosis of this groin eruption included Hailey-Hailey disease; pemphigus vegetans, Hallopeau type; tinea cruris; and inverse psoriasis. Hailey-Hailey disease can be complicated by a superimposed candidal infection with similar clinical features, and biopsy may be required for definitive diagnosis. Hailey-Hailey disease typically presents with macerated fissured plaques that resemble macerated tissue paper with red fissures (Figure 3). Biopsy confirms full-thickness acantholysis resembling a dilapidated brick wall with minimal dyskeratosis.1 Pemphigus vegetans is a localized variant of pemphigus vulgaris with a predilection for flexural surfaces. The lesions progress to vegetating erosive plaques.4 The Hallopeau type often is studded with pustules and typically remains more localized than the Neumann type. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates intercellular deposition of IgG and C3, and routine sections characteristically show pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses.1,4 Tinea cruris is characterized by erythematous annular lesions with raised scaly borders spreading down the inner thighs.7 The epidermis is variably spongiotic with parakeratosis, and neutrophils often present in a layered stratum corneum with basketweave keratin above a layer of more compact and eosinophilic keratin. Fungal stains, such as periodic acid-Schiff, will highlight the fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum. The inguinal folds are a typical location for inverse psoriasis, which generally appears as thin, sharply demarcated, shiny red plaques with less scale than plaque psoriasis.1 Psoriasiform hyperplasia with a diminished granular layer and tortuous papillary dermal vessels would be expected histologically.1

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- Schwartz RA, Tarlow MM. Dermatologic manifestations of Job syndrome. Medscape website. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1050852-overview. Updated April 22, 2019. Accessed March 28, 2020.

- Minegishi Y, Saito M. Cutaneous manifestations of hyper IgE syndrome. Allergol Int. 2012;61:191-196.

- Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Executive summary: clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:409-417.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Antifungal resistance. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/antifungal-resistance.html. Updated March 17, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2020.

- Tinea cruris. DermNet NZ website. https://www.dermnetnz.org/topics/tinea-cruris/. Published 2003. Accessed March 28, 2020.

The Diagnosis: Candidal Intertrigo

The biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of severe hyperkeratotic candidal intertrigo with no evidence of Hailey-Hailey disease. Hematoxylin and eosin- stained sections demonstrated irregular acanthosis and variable spongiosis. The stratum corneum was predominantly orthokeratotic with overlying psuedohyphae and yeast fungal elements (Figure 1).

Hyperimmunoglobulinemia E syndrome (HIES), also known as hyper-IgE syndrome or Job syndrome, is a rare immunodeficiency disorder characterized by an eczematous dermatitis-like rash, recurrent skin and lung abscesses, eosinophilia, and elevated serum IgE. Facial asymmetry, prominent forehead, deep-set eyes, broad nose, and roughened facial skin with large pores are characteristic of the sporadic and autosomal-recessive forms. Other common findings include retained primary teeth, hyperextensible joints, and recurrent mucocutaneous candidiasis.1

Although autosomal-dominant and autosomal-recessive inheritance patterns exist, sporadic mutations are the most common cause of HIES.2 Several genes have been implicated depending on the inheritance pattern. The majority of autosomal-dominant cases are associated with inactivating STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) mutations, whereas the majority of autosomal-recessive cases are associated with inactivating DOCK8 (dedicator of cytokinesis 8) mutations.1 Ultimately, all of these mutations lead to an impaired helper T cell (TH17) response, which is crucial for clearing fungal and extracellular bacterial infections.3

Skin eruptions typically are the first manifestation of HIES; they appear within the first week to month of life as papulopustular eruptions on the face and scalp and rapidly generalize to the rest of the body, favoring the shoulders, arms, chest, and buttocks. The pustules then coalesce into crusted plaques that resemble atopic dermatitis, frequently with superimposed Staphylococcus aureus infection. On microscopy, the pustules are folliculocentric and often contain eosinophils, whereas the plaques may contain intraepidermal collections of eosinophils.1

Mucocutaneous candidiasis is seen in approximately 60% of HIES cases and is closely linked to STAT3 inactivating mutations.3 Histologically, there is marked acanthosis with neutrophil exocytosis and abundant yeast and pseudohyphal forms within the stratum corneum (Figure 2).4 Cutaneous candidal infections typically require both oral and topical antifungal agents to clear the infection.3 Most cases of mucocutaneous candidiasis are caused by Candida albicans; however, other known culprits include Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida krusei.5,6 Of note, species identification and antifungal susceptibility studies may be useful in refractory cases, especially with C glabrata, which is known to acquire resistance to azoles, such as fluconazole, with emerging resistance to echinocandins.6

The differential diagnosis of this groin eruption included Hailey-Hailey disease; pemphigus vegetans, Hallopeau type; tinea cruris; and inverse psoriasis. Hailey-Hailey disease can be complicated by a superimposed candidal infection with similar clinical features, and biopsy may be required for definitive diagnosis. Hailey-Hailey disease typically presents with macerated fissured plaques that resemble macerated tissue paper with red fissures (Figure 3). Biopsy confirms full-thickness acantholysis resembling a dilapidated brick wall with minimal dyskeratosis.1 Pemphigus vegetans is a localized variant of pemphigus vulgaris with a predilection for flexural surfaces. The lesions progress to vegetating erosive plaques.4 The Hallopeau type often is studded with pustules and typically remains more localized than the Neumann type. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates intercellular deposition of IgG and C3, and routine sections characteristically show pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses.1,4 Tinea cruris is characterized by erythematous annular lesions with raised scaly borders spreading down the inner thighs.7 The epidermis is variably spongiotic with parakeratosis, and neutrophils often present in a layered stratum corneum with basketweave keratin above a layer of more compact and eosinophilic keratin. Fungal stains, such as periodic acid-Schiff, will highlight the fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum. The inguinal folds are a typical location for inverse psoriasis, which generally appears as thin, sharply demarcated, shiny red plaques with less scale than plaque psoriasis.1 Psoriasiform hyperplasia with a diminished granular layer and tortuous papillary dermal vessels would be expected histologically.1

The Diagnosis: Candidal Intertrigo

The biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of severe hyperkeratotic candidal intertrigo with no evidence of Hailey-Hailey disease. Hematoxylin and eosin- stained sections demonstrated irregular acanthosis and variable spongiosis. The stratum corneum was predominantly orthokeratotic with overlying psuedohyphae and yeast fungal elements (Figure 1).

Hyperimmunoglobulinemia E syndrome (HIES), also known as hyper-IgE syndrome or Job syndrome, is a rare immunodeficiency disorder characterized by an eczematous dermatitis-like rash, recurrent skin and lung abscesses, eosinophilia, and elevated serum IgE. Facial asymmetry, prominent forehead, deep-set eyes, broad nose, and roughened facial skin with large pores are characteristic of the sporadic and autosomal-recessive forms. Other common findings include retained primary teeth, hyperextensible joints, and recurrent mucocutaneous candidiasis.1

Although autosomal-dominant and autosomal-recessive inheritance patterns exist, sporadic mutations are the most common cause of HIES.2 Several genes have been implicated depending on the inheritance pattern. The majority of autosomal-dominant cases are associated with inactivating STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) mutations, whereas the majority of autosomal-recessive cases are associated with inactivating DOCK8 (dedicator of cytokinesis 8) mutations.1 Ultimately, all of these mutations lead to an impaired helper T cell (TH17) response, which is crucial for clearing fungal and extracellular bacterial infections.3

Skin eruptions typically are the first manifestation of HIES; they appear within the first week to month of life as papulopustular eruptions on the face and scalp and rapidly generalize to the rest of the body, favoring the shoulders, arms, chest, and buttocks. The pustules then coalesce into crusted plaques that resemble atopic dermatitis, frequently with superimposed Staphylococcus aureus infection. On microscopy, the pustules are folliculocentric and often contain eosinophils, whereas the plaques may contain intraepidermal collections of eosinophils.1

Mucocutaneous candidiasis is seen in approximately 60% of HIES cases and is closely linked to STAT3 inactivating mutations.3 Histologically, there is marked acanthosis with neutrophil exocytosis and abundant yeast and pseudohyphal forms within the stratum corneum (Figure 2).4 Cutaneous candidal infections typically require both oral and topical antifungal agents to clear the infection.3 Most cases of mucocutaneous candidiasis are caused by Candida albicans; however, other known culprits include Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida krusei.5,6 Of note, species identification and antifungal susceptibility studies may be useful in refractory cases, especially with C glabrata, which is known to acquire resistance to azoles, such as fluconazole, with emerging resistance to echinocandins.6

The differential diagnosis of this groin eruption included Hailey-Hailey disease; pemphigus vegetans, Hallopeau type; tinea cruris; and inverse psoriasis. Hailey-Hailey disease can be complicated by a superimposed candidal infection with similar clinical features, and biopsy may be required for definitive diagnosis. Hailey-Hailey disease typically presents with macerated fissured plaques that resemble macerated tissue paper with red fissures (Figure 3). Biopsy confirms full-thickness acantholysis resembling a dilapidated brick wall with minimal dyskeratosis.1 Pemphigus vegetans is a localized variant of pemphigus vulgaris with a predilection for flexural surfaces. The lesions progress to vegetating erosive plaques.4 The Hallopeau type often is studded with pustules and typically remains more localized than the Neumann type. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates intercellular deposition of IgG and C3, and routine sections characteristically show pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses.1,4 Tinea cruris is characterized by erythematous annular lesions with raised scaly borders spreading down the inner thighs.7 The epidermis is variably spongiotic with parakeratosis, and neutrophils often present in a layered stratum corneum with basketweave keratin above a layer of more compact and eosinophilic keratin. Fungal stains, such as periodic acid-Schiff, will highlight the fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum. The inguinal folds are a typical location for inverse psoriasis, which generally appears as thin, sharply demarcated, shiny red plaques with less scale than plaque psoriasis.1 Psoriasiform hyperplasia with a diminished granular layer and tortuous papillary dermal vessels would be expected histologically.1

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- Schwartz RA, Tarlow MM. Dermatologic manifestations of Job syndrome. Medscape website. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1050852-overview. Updated April 22, 2019. Accessed March 28, 2020.

- Minegishi Y, Saito M. Cutaneous manifestations of hyper IgE syndrome. Allergol Int. 2012;61:191-196.

- Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Executive summary: clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:409-417.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Antifungal resistance. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/antifungal-resistance.html. Updated March 17, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2020.

- Tinea cruris. DermNet NZ website. https://www.dermnetnz.org/topics/tinea-cruris/. Published 2003. Accessed March 28, 2020.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- Schwartz RA, Tarlow MM. Dermatologic manifestations of Job syndrome. Medscape website. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1050852-overview. Updated April 22, 2019. Accessed March 28, 2020.

- Minegishi Y, Saito M. Cutaneous manifestations of hyper IgE syndrome. Allergol Int. 2012;61:191-196.

- Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Executive summary: clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:409-417.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Antifungal resistance. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/antifungal-resistance.html. Updated March 17, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2020.

- Tinea cruris. DermNet NZ website. https://www.dermnetnz.org/topics/tinea-cruris/. Published 2003. Accessed March 28, 2020.

A 28-year-old man with a history of hyperimmunoglobulinemia E syndrome (previously known as Job syndrome), coarse facial features, and multiple skin and soft tissue infections presented to the university dermatology clinic with persistent white, macerated, fissured groin plaques that were present for months. The lesions were tender and pruritic with a burning sensation. Treatment with topical terbinafine and oral fluconazole was attempted without resolution of the eruption. A biopsy of the groin lesion was performed.

Solitary Nodule on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Ruptured Molluscum

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is caused by a DNA virus (MC virus) belonging to the poxvirus family. Molluscum contagiosum is common and predominantly seen in children and young adults. In sexually active adults, the lesions commonly occur in the genital region, abdomen, and inner thighs. In immunocompromised individuals, including those with AIDS, the lesions are more extensive and may cause disfigurement.1 Molluscum contagiosum involving epidermoid cysts has been reported.2

Histopathologically, MC can be classified as noninflammatory or inflammatory. In noninflamed lesions, multiple large, intracytoplasmic, eosinophilic inclusions (Henderson-Paterson bodies) appear within the lobulated endophytic and hyperplastic epidermis. Ultrastructurally, these bodies show membrane-bound collections of MC virus.1 Replicating Henderson-Paterson bodies can result in rupture and inflammation. This case demonstrates a palisading granuloma containing keratin with few Henderson-Paterson bodies (quiz image) due to prior rupture of a molluscum or molluscoid cyst.

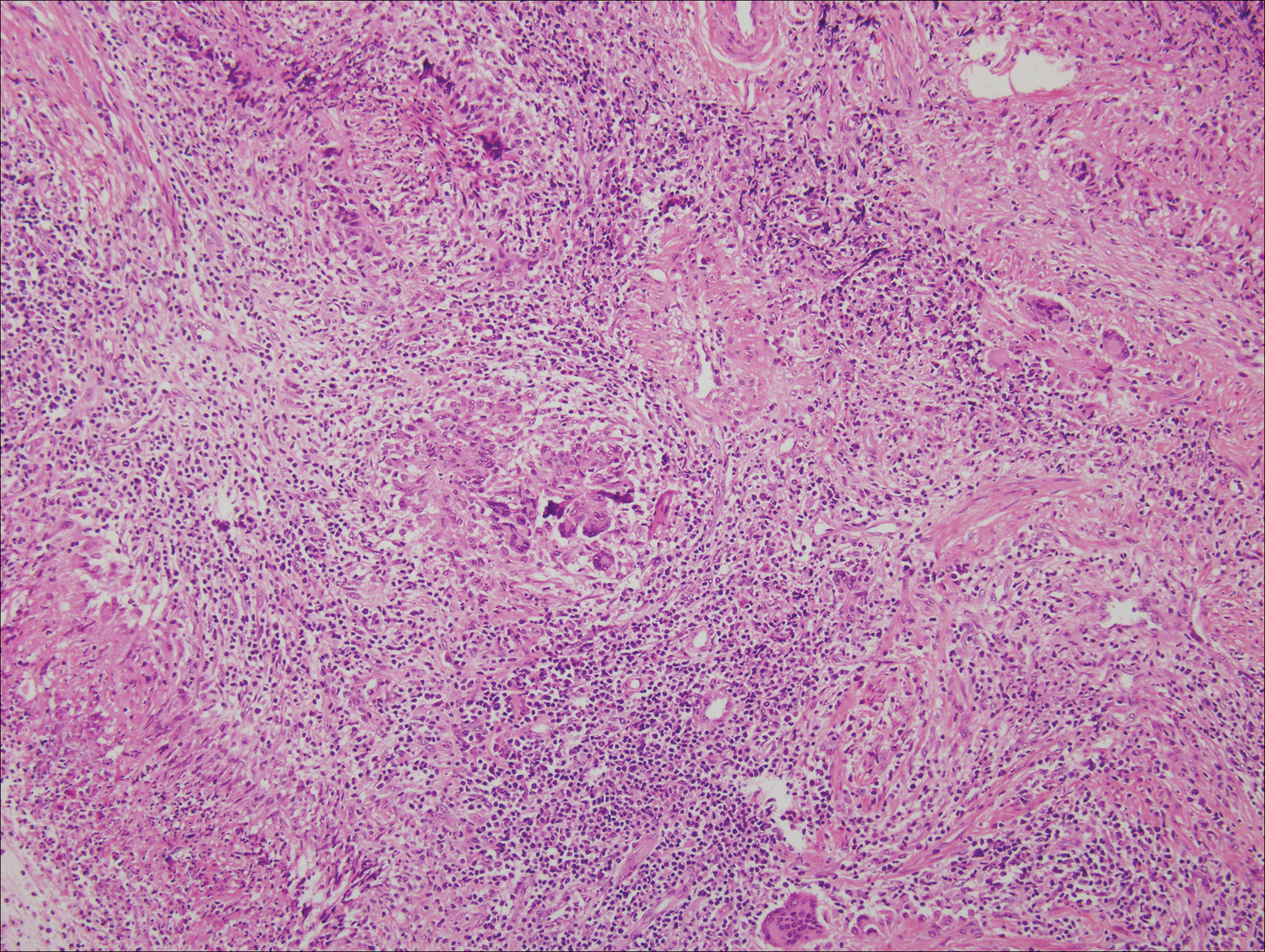

Rheumatoid nodules, the most characteristic histopathologic lesions of rheumatoid arthritis, are most commonly found in the subcutis at points of pressure and may occur in connective tissue of numerous organs. Rheumatoid nodules are firm, nontender, and mobile within the subcutaneous tissue but may be fixed to underlying structures including the periosteum, tendons, or bursae.3,4 Occasionally, superficial nodules may perforate the epidermis.5 The inner central necrobiotic zone appears as intensely eosinophilic, amorphous fibrin and other cellular debris. This central area is surrounded by histiocytes in a palisaded configuration (Figure 1). Multinucleated foreign body giant cells also may be present. Occasionally, mast cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils are present.6,7

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei presents with multiple discrete, smooth, yellow-brown to red, dome-shaped papules. The lesions typically are located on the central and lateral sides of the face and infrequently involve the neck. Other sites including the axillae, arms, hands, legs, and groin occasionally can be involved. Diascopy may reveal an apple jelly color.8,9 The histopathologic hallmark of lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei is an epithelioid cell granuloma with central necrosis (Figure 2).

Epithelioid sarcoma (ES) is a soft tissue tumor with a known propensity for local recurrence, regional lymph node involvement, sporotrichoid spread, and distant metastases.10 The name was coined by Enzinger11 in 1970 during a review of 62 cases of a “peculiar form of sarcoma that has repeatedly been confused with a chronic inflammatory process, a necrotizing granuloma, and a squamous cell carcinoma.” Epithelioid sarcoma tends to grow slowly in a nodular or multinodular manner along fascial structures and tendons, often with central necrosis and ulceration of the overlying skin. Histopathologically, classic ES shows nodular masses of uniform plump epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and prominent central necrosis. A biphasic pattern is typical with spindle cells merging with epithelioid cells. Cellular atypia is relatively mild and mitoses are rare (Figure 3). Recurrent or metastatic lesions can show a greater degree of pleomorphism.12 Given the low-grade atypia in early lesions, this sarcoma is easily misdiagnosed as granulomatous dermatitis. Immunohistochemically, the majority of ES cases are positive for cytokeratins and epithelial membrane antigen; SMARCB1/INI-1 expression is characteristically lost.13

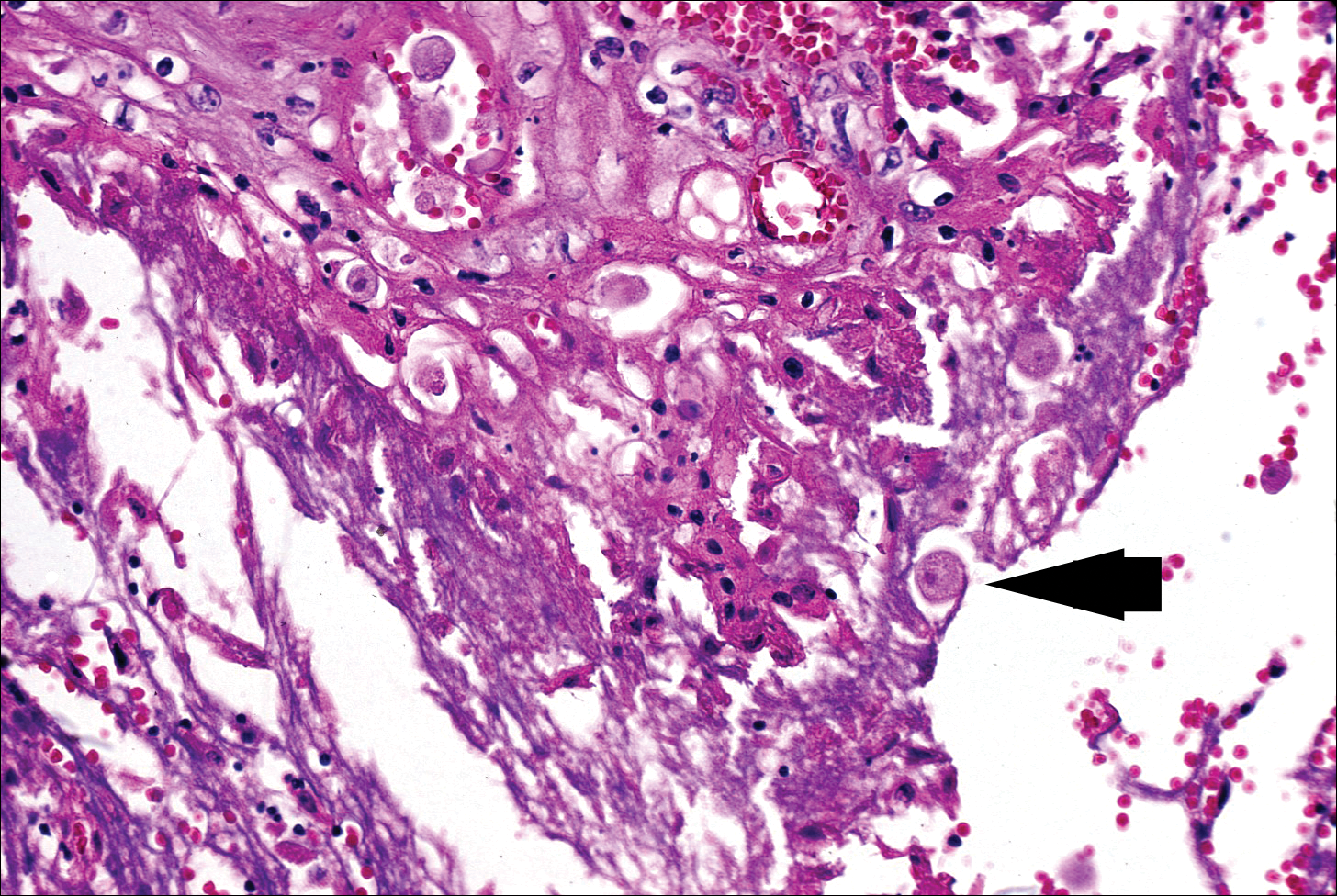

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis) is an autoimmune vasculitis highly associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Clinical manifestations include systemic necrotizing vasculitis; necrotizing glomerulonephritis; and granulomatous inflammation, which predominantly involves the upper respiratory tract, skin, and mucosa.14,15 Skin involvement may be the initial manifestation of the disease and consists of palpable purpura, papules, ulcerations, vesicles, subcutaneous nodules, necrotizing ulcerations, papulonecrotic lesions, and petechiae. None of the findings are pathognomonic. The cutaneous histopathologic spectrum includes leukocytoclastic vasculitis, extravascular palisading granulomas, and granulomatous vasculitis.16 In the acute lesions of granulomatosis with polyangiitis, the predominant pattern of inflammation is not granulomatous but purulent with the appearance of an abscess. As it evolves, it develops a central zone of necrosis with extensive karyorrhectic debris and palisades of macrophages with scattered multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4).17

1. Nandhini G, Rajkumar K, Kanth KS, et al. Molluscum contagiosum in a 12-year-old child—report of a case and review of literature. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7:63-66.

2. Phelps A, Murphy M, Elaba Z, et al. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection in benign cutaneous epithelial cystic lesions-report of 2 cases with different pathogenesis? Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:740-742.

3. Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209; quiz 210-192.

4. Sibbitt WL Jr, Williams RC Jr. Cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:563-572.

5. Barzilai A, Huszar M, Shpiro D, et al. Pseudorheumatoid nodules in adults: a juxta-articular form of nodular granuloma annulare. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:1-5.

6. Garcia-Patos V. Rheumatoid nodule. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:100-107.

7. Patterson JW. Rheumatoid nodule and subcutaneous granuloma annulare. a comparative histologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1988;10:1-8.

8. Sehgal VN, Srivastava G, Aggarwal AK, et al. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei part II: an overview. Skinmed. 2005;4:234-238.

9. Cymerman R, Rosenstein R, Shvartsbeyn M, et al. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21. pii:13030/qt6b83q5gp.

10. Sobanko JF, Meijer L, Nigra TP. Epithelioid sarcoma: a review and update. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:49-54.

11. Enzinger FM. Epitheloid sarcoma. a sarcoma simulating a granuloma or a carcinoma. Cancer. 1970;26:1029-1041.

12. Fisher C. Epithelioid sarcoma of Enzinger. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:114-121.

13. Miettinen M, Fanburg-Smith JC, Virolainen M, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: an immunohistochemical analysis of 112 classical and variant cases and a discussion of the differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:934-942.

14. Lutalo PM, D’Cruz DP. Diagnosis and classification of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (aka Wegener’s granulomatosis)[published online January 29, 2014]. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:94-98.

15. Frances C, Du LT, Piette JC, et al. Wegener’s granulomatosis. dermatological manifestations in 75 cases with clinicopathologic correlation. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:861-867.

16. Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener’s granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

17. Jennette JC. Nomenclature and classification of vasculitis: lessons learned from granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis). Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;164 (suppl 1):7-10.

The Diagnosis: Ruptured Molluscum

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is caused by a DNA virus (MC virus) belonging to the poxvirus family. Molluscum contagiosum is common and predominantly seen in children and young adults. In sexually active adults, the lesions commonly occur in the genital region, abdomen, and inner thighs. In immunocompromised individuals, including those with AIDS, the lesions are more extensive and may cause disfigurement.1 Molluscum contagiosum involving epidermoid cysts has been reported.2

Histopathologically, MC can be classified as noninflammatory or inflammatory. In noninflamed lesions, multiple large, intracytoplasmic, eosinophilic inclusions (Henderson-Paterson bodies) appear within the lobulated endophytic and hyperplastic epidermis. Ultrastructurally, these bodies show membrane-bound collections of MC virus.1 Replicating Henderson-Paterson bodies can result in rupture and inflammation. This case demonstrates a palisading granuloma containing keratin with few Henderson-Paterson bodies (quiz image) due to prior rupture of a molluscum or molluscoid cyst.

Rheumatoid nodules, the most characteristic histopathologic lesions of rheumatoid arthritis, are most commonly found in the subcutis at points of pressure and may occur in connective tissue of numerous organs. Rheumatoid nodules are firm, nontender, and mobile within the subcutaneous tissue but may be fixed to underlying structures including the periosteum, tendons, or bursae.3,4 Occasionally, superficial nodules may perforate the epidermis.5 The inner central necrobiotic zone appears as intensely eosinophilic, amorphous fibrin and other cellular debris. This central area is surrounded by histiocytes in a palisaded configuration (Figure 1). Multinucleated foreign body giant cells also may be present. Occasionally, mast cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils are present.6,7

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei presents with multiple discrete, smooth, yellow-brown to red, dome-shaped papules. The lesions typically are located on the central and lateral sides of the face and infrequently involve the neck. Other sites including the axillae, arms, hands, legs, and groin occasionally can be involved. Diascopy may reveal an apple jelly color.8,9 The histopathologic hallmark of lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei is an epithelioid cell granuloma with central necrosis (Figure 2).

Epithelioid sarcoma (ES) is a soft tissue tumor with a known propensity for local recurrence, regional lymph node involvement, sporotrichoid spread, and distant metastases.10 The name was coined by Enzinger11 in 1970 during a review of 62 cases of a “peculiar form of sarcoma that has repeatedly been confused with a chronic inflammatory process, a necrotizing granuloma, and a squamous cell carcinoma.” Epithelioid sarcoma tends to grow slowly in a nodular or multinodular manner along fascial structures and tendons, often with central necrosis and ulceration of the overlying skin. Histopathologically, classic ES shows nodular masses of uniform plump epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and prominent central necrosis. A biphasic pattern is typical with spindle cells merging with epithelioid cells. Cellular atypia is relatively mild and mitoses are rare (Figure 3). Recurrent or metastatic lesions can show a greater degree of pleomorphism.12 Given the low-grade atypia in early lesions, this sarcoma is easily misdiagnosed as granulomatous dermatitis. Immunohistochemically, the majority of ES cases are positive for cytokeratins and epithelial membrane antigen; SMARCB1/INI-1 expression is characteristically lost.13

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis) is an autoimmune vasculitis highly associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Clinical manifestations include systemic necrotizing vasculitis; necrotizing glomerulonephritis; and granulomatous inflammation, which predominantly involves the upper respiratory tract, skin, and mucosa.14,15 Skin involvement may be the initial manifestation of the disease and consists of palpable purpura, papules, ulcerations, vesicles, subcutaneous nodules, necrotizing ulcerations, papulonecrotic lesions, and petechiae. None of the findings are pathognomonic. The cutaneous histopathologic spectrum includes leukocytoclastic vasculitis, extravascular palisading granulomas, and granulomatous vasculitis.16 In the acute lesions of granulomatosis with polyangiitis, the predominant pattern of inflammation is not granulomatous but purulent with the appearance of an abscess. As it evolves, it develops a central zone of necrosis with extensive karyorrhectic debris and palisades of macrophages with scattered multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4).17

The Diagnosis: Ruptured Molluscum

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is caused by a DNA virus (MC virus) belonging to the poxvirus family. Molluscum contagiosum is common and predominantly seen in children and young adults. In sexually active adults, the lesions commonly occur in the genital region, abdomen, and inner thighs. In immunocompromised individuals, including those with AIDS, the lesions are more extensive and may cause disfigurement.1 Molluscum contagiosum involving epidermoid cysts has been reported.2

Histopathologically, MC can be classified as noninflammatory or inflammatory. In noninflamed lesions, multiple large, intracytoplasmic, eosinophilic inclusions (Henderson-Paterson bodies) appear within the lobulated endophytic and hyperplastic epidermis. Ultrastructurally, these bodies show membrane-bound collections of MC virus.1 Replicating Henderson-Paterson bodies can result in rupture and inflammation. This case demonstrates a palisading granuloma containing keratin with few Henderson-Paterson bodies (quiz image) due to prior rupture of a molluscum or molluscoid cyst.

Rheumatoid nodules, the most characteristic histopathologic lesions of rheumatoid arthritis, are most commonly found in the subcutis at points of pressure and may occur in connective tissue of numerous organs. Rheumatoid nodules are firm, nontender, and mobile within the subcutaneous tissue but may be fixed to underlying structures including the periosteum, tendons, or bursae.3,4 Occasionally, superficial nodules may perforate the epidermis.5 The inner central necrobiotic zone appears as intensely eosinophilic, amorphous fibrin and other cellular debris. This central area is surrounded by histiocytes in a palisaded configuration (Figure 1). Multinucleated foreign body giant cells also may be present. Occasionally, mast cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils are present.6,7

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei presents with multiple discrete, smooth, yellow-brown to red, dome-shaped papules. The lesions typically are located on the central and lateral sides of the face and infrequently involve the neck. Other sites including the axillae, arms, hands, legs, and groin occasionally can be involved. Diascopy may reveal an apple jelly color.8,9 The histopathologic hallmark of lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei is an epithelioid cell granuloma with central necrosis (Figure 2).

Epithelioid sarcoma (ES) is a soft tissue tumor with a known propensity for local recurrence, regional lymph node involvement, sporotrichoid spread, and distant metastases.10 The name was coined by Enzinger11 in 1970 during a review of 62 cases of a “peculiar form of sarcoma that has repeatedly been confused with a chronic inflammatory process, a necrotizing granuloma, and a squamous cell carcinoma.” Epithelioid sarcoma tends to grow slowly in a nodular or multinodular manner along fascial structures and tendons, often with central necrosis and ulceration of the overlying skin. Histopathologically, classic ES shows nodular masses of uniform plump epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and prominent central necrosis. A biphasic pattern is typical with spindle cells merging with epithelioid cells. Cellular atypia is relatively mild and mitoses are rare (Figure 3). Recurrent or metastatic lesions can show a greater degree of pleomorphism.12 Given the low-grade atypia in early lesions, this sarcoma is easily misdiagnosed as granulomatous dermatitis. Immunohistochemically, the majority of ES cases are positive for cytokeratins and epithelial membrane antigen; SMARCB1/INI-1 expression is characteristically lost.13

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis) is an autoimmune vasculitis highly associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Clinical manifestations include systemic necrotizing vasculitis; necrotizing glomerulonephritis; and granulomatous inflammation, which predominantly involves the upper respiratory tract, skin, and mucosa.14,15 Skin involvement may be the initial manifestation of the disease and consists of palpable purpura, papules, ulcerations, vesicles, subcutaneous nodules, necrotizing ulcerations, papulonecrotic lesions, and petechiae. None of the findings are pathognomonic. The cutaneous histopathologic spectrum includes leukocytoclastic vasculitis, extravascular palisading granulomas, and granulomatous vasculitis.16 In the acute lesions of granulomatosis with polyangiitis, the predominant pattern of inflammation is not granulomatous but purulent with the appearance of an abscess. As it evolves, it develops a central zone of necrosis with extensive karyorrhectic debris and palisades of macrophages with scattered multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4).17

1. Nandhini G, Rajkumar K, Kanth KS, et al. Molluscum contagiosum in a 12-year-old child—report of a case and review of literature. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7:63-66.

2. Phelps A, Murphy M, Elaba Z, et al. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection in benign cutaneous epithelial cystic lesions-report of 2 cases with different pathogenesis? Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:740-742.

3. Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209; quiz 210-192.

4. Sibbitt WL Jr, Williams RC Jr. Cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:563-572.

5. Barzilai A, Huszar M, Shpiro D, et al. Pseudorheumatoid nodules in adults: a juxta-articular form of nodular granuloma annulare. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:1-5.

6. Garcia-Patos V. Rheumatoid nodule. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:100-107.

7. Patterson JW. Rheumatoid nodule and subcutaneous granuloma annulare. a comparative histologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1988;10:1-8.