User login

A Fixed Drug Eruption to Medroxyprogesterone Acetate Injectable Suspension

To the Editor:

A fixed drug eruption (FDE) is a well-documented form of cutaneous hypersensitivity that typically manifests as a sharply demarcated, dusky, round to oval, edematous, red-violaceous macule or patch on the skin and mucous membranes. The lesion often resolves with residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, most commonly as a reaction to ingested drugs or drug components.1 Lesions generally occur at the same anatomic site with repeated exposure to the offending drug. Typically, a single site is affected, but additional sites with more generalized involvement have been reported to occur with subsequent exposure to the offending medication. The diagnosis usually is clinical, but histopathologic findings can help confirm the diagnosis in unusual presentations. We present a novel case of a patient with an FDE from medroxyprogesterone acetate, a contraceptive injection that contains the hormone progestin.

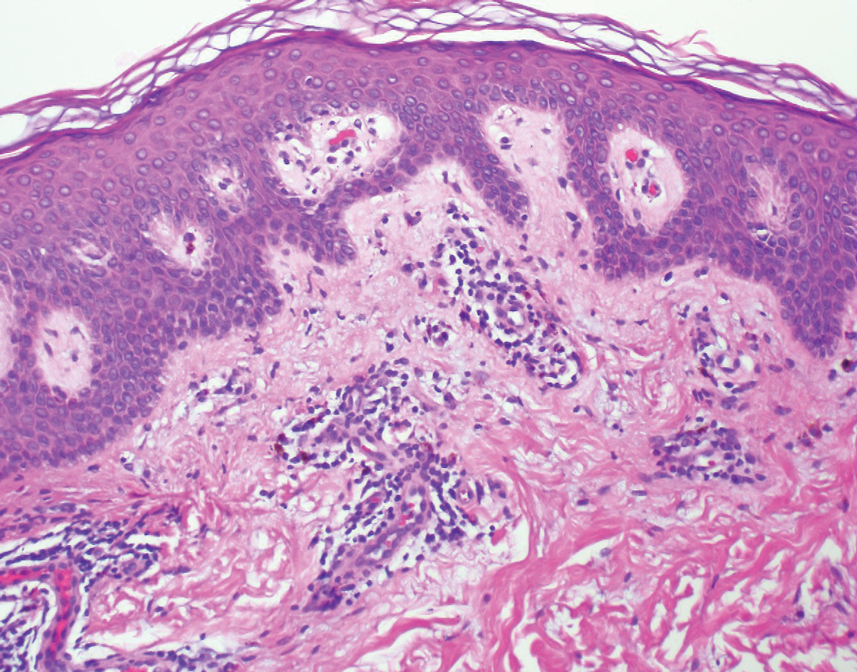

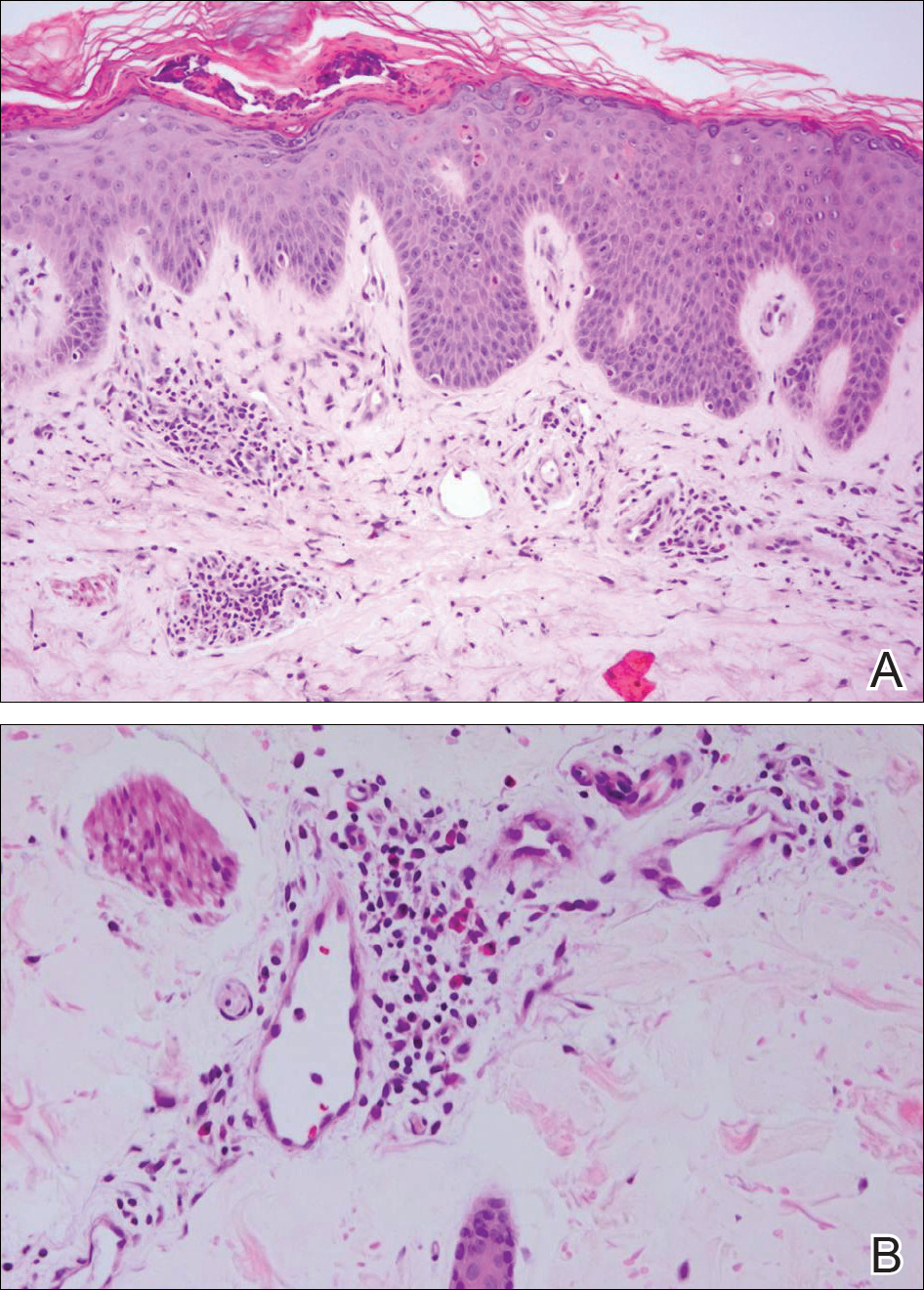

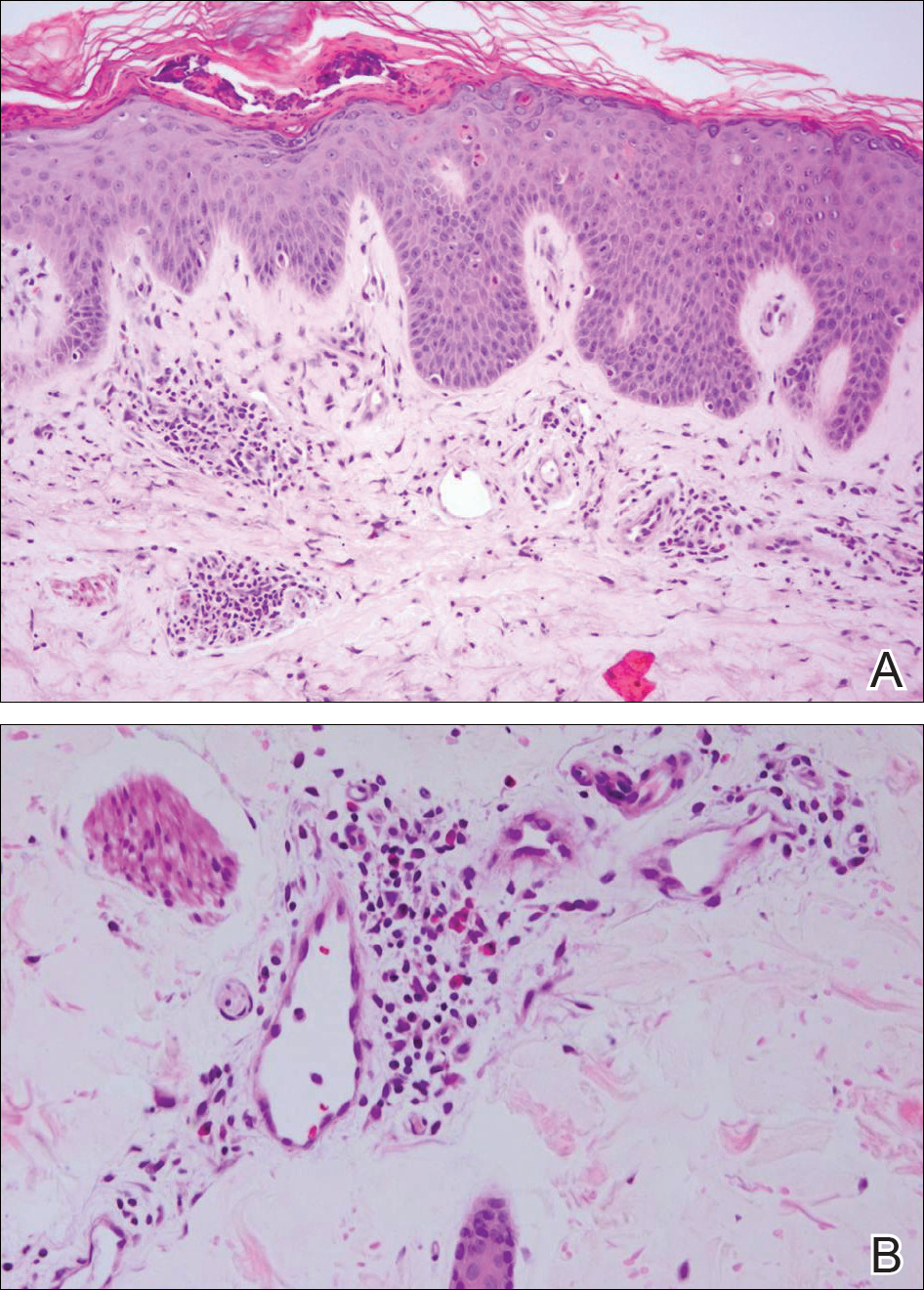

A 35-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a lesion on the left lower buttock of 1 year’s duration. She reported periodic swelling and associated pruritus of the lesion. She denied any growth in size, and no other similar lesions were present. The patient reported a medication history of medroxyprogesterone acetate for birth control, but she denied any other prescription or over-the-counter medication, oral supplements, or recreational drug use. Upon further inquiry, she reported that the recurrence of symptoms appeared to coincide with each administration of medroxyprogesterone acetate, which occurred approximately every 3 months. The eruption cleared between injections and recurred in the same location following subsequent injections. The lesion appeared approximately 2 weeks after the first injection (approximately 1 year prior to presentation to dermatology) and within 2 to 3 days after each subsequent injection. Physical examination revealed a 2×2-cm, circular, slightly violaceous patch on the left buttock (Figure 1). A biopsy was recommended to aid in diagnosis, and the patient was offered a topical steroid for symptomatic relief. A punch biopsy revealed subtle interface dermatitis with superficial perivascular lymphoid infiltrate and marked pigmentary incontinence consistent with an FDE (Figure 2).

An FDE was first reported in 1889 by Bourns,2 and over time more implicated agents and varying clinical presentations have been linked to the disease. The FDE can be accompanied by symptoms of pruritus or paresthesia. Most cases are devoid of systemic symptoms. An FDE can be located anywhere on the body, but it most frequently manifests on the lips, face, hands, feet, and genitalia. Although the eruption often heals with residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, a nonpigmenting FDE due to pseudoephedrine has been reported.3

Common culprits include antibiotics (eg, sulfonamides, trimethoprim, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (eg, naproxen sodium, ibuprofen, celecoxib), barbiturates, antimalarials, and anticonvulsants. Rare cases of FDE induced by foods and food additives also have been reported.4 Oral fluconazole, levocetirizine dihydrochloride, loperamide, and multivitamin-mineral preparations are other rare inducers of FDE.5-8 In 2004, Ritter and Meffert9 described an FDE to the green dye used in inactive oral contraceptive pills. A similar case was reported by Rea et al10 that described an FDE from the inactive sugar pills in ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel, which is another combined oral contraceptive.

The time between ingestion of the offending agent and the manifestation of the disease usually is 1 to 2 weeks; however, upon subsequent exposure, the disease has been reported to manifest within hours.1 CD8+ memory T cells have been shown to be major players in the development of FDE and can be found along the dermoepidermal junction as part of a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction.11 Histopathology reveals superficial and deep interstitial and perivascular infiltrates consisting of lymphocytes with admixed eosinophils and possibly neutrophils in the dermis. In the epidermis, necrotic keratinocytes can be present. In rare cases, FDE may have atypical features, such as in generalized bullous FDE and nonpigmenting FDE, the latter of which more commonly is associated with pseudoephedrine.1

The differential diagnosis for FDE includes erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, autoimmune progesterone dermatitis, and large plaque parapsoriasis. The number and morphology of lesions in erythema multiforme help differentiate it from FDE, as erythema multiforme presents with multiple targetoid lesions. The lesions of generalized bullous FDE can be similar to those of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, and the pigmented patches of FDE can resemble large plaque parapsoriasis.

It is important to consider any medication ingested in the 1- to 2-week period before FDE onset, including over-the-counter medications, health food supplements, and prescription medications. Discontinuation of the implicated medication or any medication potentially cross-reacting with another medication is the most important step in management. Wound care may be needed for any bullous or eroded lesions. Lesions typically resolve within a few days to weeks of stopping the offending agent. Importantly, patients should be counseled on the secondary pigment alterations that may be persistent for several months. Other treatment for FDEs is aimed at symptomatic relief and may include topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines.1

Medroxyprogesterone acetate is a highly effective contraceptive drug with low rates of failure.12 It is a weak androgenic progestin that is administered as a single 150-mg intramuscular injection every 3 months and inhibits gonadotropins. Common side effects include local injection-site reactions, unscheduled bleeding, amenorrhea, weight gain, headache, and mood changes. However, FDE has not been reported as an adverse effect to medroxyprogesterone acetate, both in official US Food and Drug Administration information and in the current literature.12

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (also known as progestin hypersensitivity) is a well-characterized cyclic hypersensitivity reaction to the hormone progesterone that occurs during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. It is known to have a variable clinical presentation including urticaria, erythema multiforme, eczema, and angioedema.13 Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis also has been reported to present as an FDE.14-16 The onset of the cutaneous manifestation often starts a few days before the onset of menses, with spontaneous resolution occurring after the onset of menstruation. The mechanism by which endogenous progesterone or other secretory products become antigenic is unknown. It has been suggested that there is an alteration in the properties of the hormone that would predispose it to be antigenic as it would not be considered self. In 2001, Warin17 proposed the following diagnostic criteria for autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: (1) skin lesions associated with menstrual cycle (premenstrual flare); (2) a positive response to the progesterone intradermal or intramuscular test; and (3) symptomatic improvement after inhibiting progesterone secretion by suppressing ovulation.17 The treatment includes antiallergy medications, progesterone desensitization, omalizumab injection, and leuprolide acetate injection.

Our case represents FDE from medroxyprogesterone acetate. Although we did not formally investigate the antigenicity of the exogenous progesterone, we postulate that the pathophysiology likely is similar to an FDE associated with endogenous progesterone. This reasoning is supported by the time course of the patient’s lesion as well as the worsening of symptoms in the days following the administration of the medication. Additionally, the patient had no history of skin lesions prior to the initiation of medroxyprogesterone acetate or similar lesions associated with her menstrual cycles.

A careful and detailed review of medication history is necessary to evaluate FDEs. Our case emphasizes that not only endogenous but also exogenous forms of progesterone may cause hypersensitivity, leading to an FDE. With more than 2 million prescriptions of medroxyprogesterone acetate written every year, dermatologists should be aware of the rare but potential risk for an FDE in patients using this medication.18

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Mosby; 2008.

- Bourns DCG. Unusual effects of antipyrine. Br Med J. 1889;2:818-820.

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption as a distinctive reaction pattern: examples caused by sensitivity to pseudoephedrine hydrochloride and tetrahydrozoline. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:403-407.

- Sohn KH, Kim BK, Kim JY, et al. Fixed food eruption caused by Actinidia arguta (hardy kiwi): a case report and literature review. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2017;9:182-184.

- Nakai N, Katoh N. Fixed drug eruption caused by fluconazole: a case report and mini-review of the literature. Allergol Int. 2013;6:139-141.

- An I, Demir V, Ibiloglu I, et al. Fixed drug eruption induced by levocetirizine. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:276-278.

- Matarredona J, Borrás Blasco J, Navarro-Ruiz A, et al. Fixed drug eruption associated to loperamide [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc). 2005;124:198-199.

- Gohel D. Fixed drug eruption due to multi-vitamin multi-mineral preparation. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48:268.

- Ritter SE, Meffert J. A refractory fixed drug reaction to a dye used in an oral contraceptive. Cutis. 2004;74:243-244.

- Rea S, McMeniman E, Darch K, et al. A fixed drug eruption to the sugar pills of a combined oral contraceptive. Poster presented at: The Australasian College of Dermatologists 51st Annual Scientific Meeting; May 22, 2018; Queensland, Australia.

- Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y. Fixed drug eruption: a disease mediated by self-inflicted responses of intraepidermal T cells. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:201-208.

- Depo-Provera CI. Prescribing information. Pfizer; 2020. Accessed March 10, 2022. https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?format=PDF&id=522

- George R, Badawy SZ. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:757854.

- Mokhtari R, Sepaskhah M, Aslani FS, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt685685p4.

- Asai J, Katoh N, Nakano M, et al. Case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption. J Dermatol. 2009;36:643-645.

- Bhardwaj N, Jindal R, Chauhan P. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:E231873.

- Warin AP. Case 2. diagnosis: erythema multiforme as a presentation of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:107-108.

- Medroxyprogesterone Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013-2019. ClinCalc website. Updated September 15, 2021. Accessed March 17, 2022. https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Medroxyprogesterone

To the Editor:

A fixed drug eruption (FDE) is a well-documented form of cutaneous hypersensitivity that typically manifests as a sharply demarcated, dusky, round to oval, edematous, red-violaceous macule or patch on the skin and mucous membranes. The lesion often resolves with residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, most commonly as a reaction to ingested drugs or drug components.1 Lesions generally occur at the same anatomic site with repeated exposure to the offending drug. Typically, a single site is affected, but additional sites with more generalized involvement have been reported to occur with subsequent exposure to the offending medication. The diagnosis usually is clinical, but histopathologic findings can help confirm the diagnosis in unusual presentations. We present a novel case of a patient with an FDE from medroxyprogesterone acetate, a contraceptive injection that contains the hormone progestin.

A 35-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a lesion on the left lower buttock of 1 year’s duration. She reported periodic swelling and associated pruritus of the lesion. She denied any growth in size, and no other similar lesions were present. The patient reported a medication history of medroxyprogesterone acetate for birth control, but she denied any other prescription or over-the-counter medication, oral supplements, or recreational drug use. Upon further inquiry, she reported that the recurrence of symptoms appeared to coincide with each administration of medroxyprogesterone acetate, which occurred approximately every 3 months. The eruption cleared between injections and recurred in the same location following subsequent injections. The lesion appeared approximately 2 weeks after the first injection (approximately 1 year prior to presentation to dermatology) and within 2 to 3 days after each subsequent injection. Physical examination revealed a 2×2-cm, circular, slightly violaceous patch on the left buttock (Figure 1). A biopsy was recommended to aid in diagnosis, and the patient was offered a topical steroid for symptomatic relief. A punch biopsy revealed subtle interface dermatitis with superficial perivascular lymphoid infiltrate and marked pigmentary incontinence consistent with an FDE (Figure 2).

An FDE was first reported in 1889 by Bourns,2 and over time more implicated agents and varying clinical presentations have been linked to the disease. The FDE can be accompanied by symptoms of pruritus or paresthesia. Most cases are devoid of systemic symptoms. An FDE can be located anywhere on the body, but it most frequently manifests on the lips, face, hands, feet, and genitalia. Although the eruption often heals with residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, a nonpigmenting FDE due to pseudoephedrine has been reported.3

Common culprits include antibiotics (eg, sulfonamides, trimethoprim, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (eg, naproxen sodium, ibuprofen, celecoxib), barbiturates, antimalarials, and anticonvulsants. Rare cases of FDE induced by foods and food additives also have been reported.4 Oral fluconazole, levocetirizine dihydrochloride, loperamide, and multivitamin-mineral preparations are other rare inducers of FDE.5-8 In 2004, Ritter and Meffert9 described an FDE to the green dye used in inactive oral contraceptive pills. A similar case was reported by Rea et al10 that described an FDE from the inactive sugar pills in ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel, which is another combined oral contraceptive.

The time between ingestion of the offending agent and the manifestation of the disease usually is 1 to 2 weeks; however, upon subsequent exposure, the disease has been reported to manifest within hours.1 CD8+ memory T cells have been shown to be major players in the development of FDE and can be found along the dermoepidermal junction as part of a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction.11 Histopathology reveals superficial and deep interstitial and perivascular infiltrates consisting of lymphocytes with admixed eosinophils and possibly neutrophils in the dermis. In the epidermis, necrotic keratinocytes can be present. In rare cases, FDE may have atypical features, such as in generalized bullous FDE and nonpigmenting FDE, the latter of which more commonly is associated with pseudoephedrine.1

The differential diagnosis for FDE includes erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, autoimmune progesterone dermatitis, and large plaque parapsoriasis. The number and morphology of lesions in erythema multiforme help differentiate it from FDE, as erythema multiforme presents with multiple targetoid lesions. The lesions of generalized bullous FDE can be similar to those of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, and the pigmented patches of FDE can resemble large plaque parapsoriasis.

It is important to consider any medication ingested in the 1- to 2-week period before FDE onset, including over-the-counter medications, health food supplements, and prescription medications. Discontinuation of the implicated medication or any medication potentially cross-reacting with another medication is the most important step in management. Wound care may be needed for any bullous or eroded lesions. Lesions typically resolve within a few days to weeks of stopping the offending agent. Importantly, patients should be counseled on the secondary pigment alterations that may be persistent for several months. Other treatment for FDEs is aimed at symptomatic relief and may include topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines.1

Medroxyprogesterone acetate is a highly effective contraceptive drug with low rates of failure.12 It is a weak androgenic progestin that is administered as a single 150-mg intramuscular injection every 3 months and inhibits gonadotropins. Common side effects include local injection-site reactions, unscheduled bleeding, amenorrhea, weight gain, headache, and mood changes. However, FDE has not been reported as an adverse effect to medroxyprogesterone acetate, both in official US Food and Drug Administration information and in the current literature.12

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (also known as progestin hypersensitivity) is a well-characterized cyclic hypersensitivity reaction to the hormone progesterone that occurs during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. It is known to have a variable clinical presentation including urticaria, erythema multiforme, eczema, and angioedema.13 Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis also has been reported to present as an FDE.14-16 The onset of the cutaneous manifestation often starts a few days before the onset of menses, with spontaneous resolution occurring after the onset of menstruation. The mechanism by which endogenous progesterone or other secretory products become antigenic is unknown. It has been suggested that there is an alteration in the properties of the hormone that would predispose it to be antigenic as it would not be considered self. In 2001, Warin17 proposed the following diagnostic criteria for autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: (1) skin lesions associated with menstrual cycle (premenstrual flare); (2) a positive response to the progesterone intradermal or intramuscular test; and (3) symptomatic improvement after inhibiting progesterone secretion by suppressing ovulation.17 The treatment includes antiallergy medications, progesterone desensitization, omalizumab injection, and leuprolide acetate injection.

Our case represents FDE from medroxyprogesterone acetate. Although we did not formally investigate the antigenicity of the exogenous progesterone, we postulate that the pathophysiology likely is similar to an FDE associated with endogenous progesterone. This reasoning is supported by the time course of the patient’s lesion as well as the worsening of symptoms in the days following the administration of the medication. Additionally, the patient had no history of skin lesions prior to the initiation of medroxyprogesterone acetate or similar lesions associated with her menstrual cycles.

A careful and detailed review of medication history is necessary to evaluate FDEs. Our case emphasizes that not only endogenous but also exogenous forms of progesterone may cause hypersensitivity, leading to an FDE. With more than 2 million prescriptions of medroxyprogesterone acetate written every year, dermatologists should be aware of the rare but potential risk for an FDE in patients using this medication.18

To the Editor:

A fixed drug eruption (FDE) is a well-documented form of cutaneous hypersensitivity that typically manifests as a sharply demarcated, dusky, round to oval, edematous, red-violaceous macule or patch on the skin and mucous membranes. The lesion often resolves with residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, most commonly as a reaction to ingested drugs or drug components.1 Lesions generally occur at the same anatomic site with repeated exposure to the offending drug. Typically, a single site is affected, but additional sites with more generalized involvement have been reported to occur with subsequent exposure to the offending medication. The diagnosis usually is clinical, but histopathologic findings can help confirm the diagnosis in unusual presentations. We present a novel case of a patient with an FDE from medroxyprogesterone acetate, a contraceptive injection that contains the hormone progestin.

A 35-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a lesion on the left lower buttock of 1 year’s duration. She reported periodic swelling and associated pruritus of the lesion. She denied any growth in size, and no other similar lesions were present. The patient reported a medication history of medroxyprogesterone acetate for birth control, but she denied any other prescription or over-the-counter medication, oral supplements, or recreational drug use. Upon further inquiry, she reported that the recurrence of symptoms appeared to coincide with each administration of medroxyprogesterone acetate, which occurred approximately every 3 months. The eruption cleared between injections and recurred in the same location following subsequent injections. The lesion appeared approximately 2 weeks after the first injection (approximately 1 year prior to presentation to dermatology) and within 2 to 3 days after each subsequent injection. Physical examination revealed a 2×2-cm, circular, slightly violaceous patch on the left buttock (Figure 1). A biopsy was recommended to aid in diagnosis, and the patient was offered a topical steroid for symptomatic relief. A punch biopsy revealed subtle interface dermatitis with superficial perivascular lymphoid infiltrate and marked pigmentary incontinence consistent with an FDE (Figure 2).

An FDE was first reported in 1889 by Bourns,2 and over time more implicated agents and varying clinical presentations have been linked to the disease. The FDE can be accompanied by symptoms of pruritus or paresthesia. Most cases are devoid of systemic symptoms. An FDE can be located anywhere on the body, but it most frequently manifests on the lips, face, hands, feet, and genitalia. Although the eruption often heals with residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, a nonpigmenting FDE due to pseudoephedrine has been reported.3

Common culprits include antibiotics (eg, sulfonamides, trimethoprim, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (eg, naproxen sodium, ibuprofen, celecoxib), barbiturates, antimalarials, and anticonvulsants. Rare cases of FDE induced by foods and food additives also have been reported.4 Oral fluconazole, levocetirizine dihydrochloride, loperamide, and multivitamin-mineral preparations are other rare inducers of FDE.5-8 In 2004, Ritter and Meffert9 described an FDE to the green dye used in inactive oral contraceptive pills. A similar case was reported by Rea et al10 that described an FDE from the inactive sugar pills in ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel, which is another combined oral contraceptive.

The time between ingestion of the offending agent and the manifestation of the disease usually is 1 to 2 weeks; however, upon subsequent exposure, the disease has been reported to manifest within hours.1 CD8+ memory T cells have been shown to be major players in the development of FDE and can be found along the dermoepidermal junction as part of a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction.11 Histopathology reveals superficial and deep interstitial and perivascular infiltrates consisting of lymphocytes with admixed eosinophils and possibly neutrophils in the dermis. In the epidermis, necrotic keratinocytes can be present. In rare cases, FDE may have atypical features, such as in generalized bullous FDE and nonpigmenting FDE, the latter of which more commonly is associated with pseudoephedrine.1

The differential diagnosis for FDE includes erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, autoimmune progesterone dermatitis, and large plaque parapsoriasis. The number and morphology of lesions in erythema multiforme help differentiate it from FDE, as erythema multiforme presents with multiple targetoid lesions. The lesions of generalized bullous FDE can be similar to those of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, and the pigmented patches of FDE can resemble large plaque parapsoriasis.

It is important to consider any medication ingested in the 1- to 2-week period before FDE onset, including over-the-counter medications, health food supplements, and prescription medications. Discontinuation of the implicated medication or any medication potentially cross-reacting with another medication is the most important step in management. Wound care may be needed for any bullous or eroded lesions. Lesions typically resolve within a few days to weeks of stopping the offending agent. Importantly, patients should be counseled on the secondary pigment alterations that may be persistent for several months. Other treatment for FDEs is aimed at symptomatic relief and may include topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines.1

Medroxyprogesterone acetate is a highly effective contraceptive drug with low rates of failure.12 It is a weak androgenic progestin that is administered as a single 150-mg intramuscular injection every 3 months and inhibits gonadotropins. Common side effects include local injection-site reactions, unscheduled bleeding, amenorrhea, weight gain, headache, and mood changes. However, FDE has not been reported as an adverse effect to medroxyprogesterone acetate, both in official US Food and Drug Administration information and in the current literature.12

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (also known as progestin hypersensitivity) is a well-characterized cyclic hypersensitivity reaction to the hormone progesterone that occurs during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. It is known to have a variable clinical presentation including urticaria, erythema multiforme, eczema, and angioedema.13 Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis also has been reported to present as an FDE.14-16 The onset of the cutaneous manifestation often starts a few days before the onset of menses, with spontaneous resolution occurring after the onset of menstruation. The mechanism by which endogenous progesterone or other secretory products become antigenic is unknown. It has been suggested that there is an alteration in the properties of the hormone that would predispose it to be antigenic as it would not be considered self. In 2001, Warin17 proposed the following diagnostic criteria for autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: (1) skin lesions associated with menstrual cycle (premenstrual flare); (2) a positive response to the progesterone intradermal or intramuscular test; and (3) symptomatic improvement after inhibiting progesterone secretion by suppressing ovulation.17 The treatment includes antiallergy medications, progesterone desensitization, omalizumab injection, and leuprolide acetate injection.

Our case represents FDE from medroxyprogesterone acetate. Although we did not formally investigate the antigenicity of the exogenous progesterone, we postulate that the pathophysiology likely is similar to an FDE associated with endogenous progesterone. This reasoning is supported by the time course of the patient’s lesion as well as the worsening of symptoms in the days following the administration of the medication. Additionally, the patient had no history of skin lesions prior to the initiation of medroxyprogesterone acetate or similar lesions associated with her menstrual cycles.

A careful and detailed review of medication history is necessary to evaluate FDEs. Our case emphasizes that not only endogenous but also exogenous forms of progesterone may cause hypersensitivity, leading to an FDE. With more than 2 million prescriptions of medroxyprogesterone acetate written every year, dermatologists should be aware of the rare but potential risk for an FDE in patients using this medication.18

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Mosby; 2008.

- Bourns DCG. Unusual effects of antipyrine. Br Med J. 1889;2:818-820.

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption as a distinctive reaction pattern: examples caused by sensitivity to pseudoephedrine hydrochloride and tetrahydrozoline. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:403-407.

- Sohn KH, Kim BK, Kim JY, et al. Fixed food eruption caused by Actinidia arguta (hardy kiwi): a case report and literature review. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2017;9:182-184.

- Nakai N, Katoh N. Fixed drug eruption caused by fluconazole: a case report and mini-review of the literature. Allergol Int. 2013;6:139-141.

- An I, Demir V, Ibiloglu I, et al. Fixed drug eruption induced by levocetirizine. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:276-278.

- Matarredona J, Borrás Blasco J, Navarro-Ruiz A, et al. Fixed drug eruption associated to loperamide [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc). 2005;124:198-199.

- Gohel D. Fixed drug eruption due to multi-vitamin multi-mineral preparation. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48:268.

- Ritter SE, Meffert J. A refractory fixed drug reaction to a dye used in an oral contraceptive. Cutis. 2004;74:243-244.

- Rea S, McMeniman E, Darch K, et al. A fixed drug eruption to the sugar pills of a combined oral contraceptive. Poster presented at: The Australasian College of Dermatologists 51st Annual Scientific Meeting; May 22, 2018; Queensland, Australia.

- Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y. Fixed drug eruption: a disease mediated by self-inflicted responses of intraepidermal T cells. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:201-208.

- Depo-Provera CI. Prescribing information. Pfizer; 2020. Accessed March 10, 2022. https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?format=PDF&id=522

- George R, Badawy SZ. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:757854.

- Mokhtari R, Sepaskhah M, Aslani FS, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt685685p4.

- Asai J, Katoh N, Nakano M, et al. Case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption. J Dermatol. 2009;36:643-645.

- Bhardwaj N, Jindal R, Chauhan P. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:E231873.

- Warin AP. Case 2. diagnosis: erythema multiforme as a presentation of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:107-108.

- Medroxyprogesterone Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013-2019. ClinCalc website. Updated September 15, 2021. Accessed March 17, 2022. https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Medroxyprogesterone

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Mosby; 2008.

- Bourns DCG. Unusual effects of antipyrine. Br Med J. 1889;2:818-820.

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption as a distinctive reaction pattern: examples caused by sensitivity to pseudoephedrine hydrochloride and tetrahydrozoline. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:403-407.

- Sohn KH, Kim BK, Kim JY, et al. Fixed food eruption caused by Actinidia arguta (hardy kiwi): a case report and literature review. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2017;9:182-184.

- Nakai N, Katoh N. Fixed drug eruption caused by fluconazole: a case report and mini-review of the literature. Allergol Int. 2013;6:139-141.

- An I, Demir V, Ibiloglu I, et al. Fixed drug eruption induced by levocetirizine. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:276-278.

- Matarredona J, Borrás Blasco J, Navarro-Ruiz A, et al. Fixed drug eruption associated to loperamide [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc). 2005;124:198-199.

- Gohel D. Fixed drug eruption due to multi-vitamin multi-mineral preparation. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48:268.

- Ritter SE, Meffert J. A refractory fixed drug reaction to a dye used in an oral contraceptive. Cutis. 2004;74:243-244.

- Rea S, McMeniman E, Darch K, et al. A fixed drug eruption to the sugar pills of a combined oral contraceptive. Poster presented at: The Australasian College of Dermatologists 51st Annual Scientific Meeting; May 22, 2018; Queensland, Australia.

- Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y. Fixed drug eruption: a disease mediated by self-inflicted responses of intraepidermal T cells. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:201-208.

- Depo-Provera CI. Prescribing information. Pfizer; 2020. Accessed March 10, 2022. https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?format=PDF&id=522

- George R, Badawy SZ. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:757854.

- Mokhtari R, Sepaskhah M, Aslani FS, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt685685p4.

- Asai J, Katoh N, Nakano M, et al. Case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption. J Dermatol. 2009;36:643-645.

- Bhardwaj N, Jindal R, Chauhan P. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:E231873.

- Warin AP. Case 2. diagnosis: erythema multiforme as a presentation of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:107-108.

- Medroxyprogesterone Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013-2019. ClinCalc website. Updated September 15, 2021. Accessed March 17, 2022. https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Medroxyprogesterone

Practice Points

- Exogenous progesterone from the administration of the contraceptive injectable medroxyprogesterone acetate has the potential to cause a cutaneous hypersensitivity reaction in the form of a fixed drug eruption (FDE).

- Dermatologists should perform a careful and detailed review of medication history to evaluate drug eruptions.

Perianal Condyloma Acuminatum-like Plaque

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD), a chronic inflammatory granulomatous disease of the gastrointestinal tract, has a wide spectrum of presentations.1 The condition may affect the vulva, perineum, or perianal skin by direct extension from the gastrointestinal tract or may appear as a separate and distinct cutaneous focus of disease referred to as metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2

Cutaneous lesions of MCD include ulcers, fissures, sinus tracts, abscesses, and vegetative plaques, which typically extend in continuity with sites of intra-abdominal disease to the perineum, buttocks, or abdominal wall, as well as ostomy sites or incisional scars. Erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum are the most common nonspecific cutaneous manifestations. Other cutaneous lesions described in CD include polyarteritis nodosa, psoriasis, erythema multiforme, erythema elevatum diutinum, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, acne fulminans, pyoderma faciale, neutrophilic lobular panniculitis, granulomatous vasculitis, and porokeratosis.3

Perianal skin is the most common site of cutaneous involvement in individuals with CD. It is a marker of more severe disease and is associated with multiple surgical interventions and frequent relapses and has been reported in 22% of patients with CD.4 Most already had an existing diagnosis of gastrointestinal CD, which was active in one-third of individuals; however, 20% presented with disease at nongastrointestinal sites 2 months to 4 years prior to developing the gastrointestinal CD manifestations.5 Our patient presented with lesions on the perianal skin of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea. A colonoscopy demonstrated shallow ulcers involving the ileocecal portion of the gut, colon, and rectum. A biopsy from intestinal mucosal tissue showed acute and chronic inflammation with necrosis mixed with granulomatous inflammation, suggestive of CD.

Microscopically, the dominant histologic features of MCD are similar to those of bowel lesions, including an inflammatory infiltrate commonly consisting of sterile noncaseating sarcoidal granulomas, foreign body and Langhans giant cells, epithelioid histiocytes, and plasma cells surrounded by numerous mononuclear cells within the dermis with occasional extension into the subcutis (quiz image). Less common features include collagen degeneration, an infiltrate rich in eosinophils, dermal edema, and mixed lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis.6

Metastatic CD often is misdiagnosed. A detailed history and physical examination may help narrow the differential; however, biopsy is necessary to establish a diagnosis of MCD. The histologic differential diagnosis of sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation of genital skin includes sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, leprosy or other mycobacterial and parasitic infection, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and granulomatous infiltrate associated with certain exogenous material (eg, silica, zirconium, beryllium, tattoo pigment).

Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan disease that most frequently affects the lungs, skin, and lymph nodes. Its etiopathogenesis has not been clearly elucidated.7 Cutaneous lesions are present in 20% to 35% of patients.8 Given the wide variability of clinical manifestations, cutaneous sarcoidosis is another one of the great imitators. Cutaneous lesions are classified as specific and nonspecific depending on the presence of noncaseating granulomas on histologic studies and include maculopapules, plaques, nodules, lupus pernio, scar infiltration, alopecia, ulcerative lesions, and hypopigmentation. The most common nonspecific lesion of cutaneous sarcoidosis is erythema nodosum. Other manifestations include calcifications, prurigo, erythema multiforme, nail clubbing, and Sweet syndrome.9

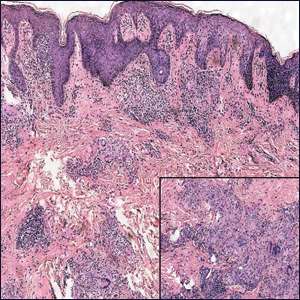

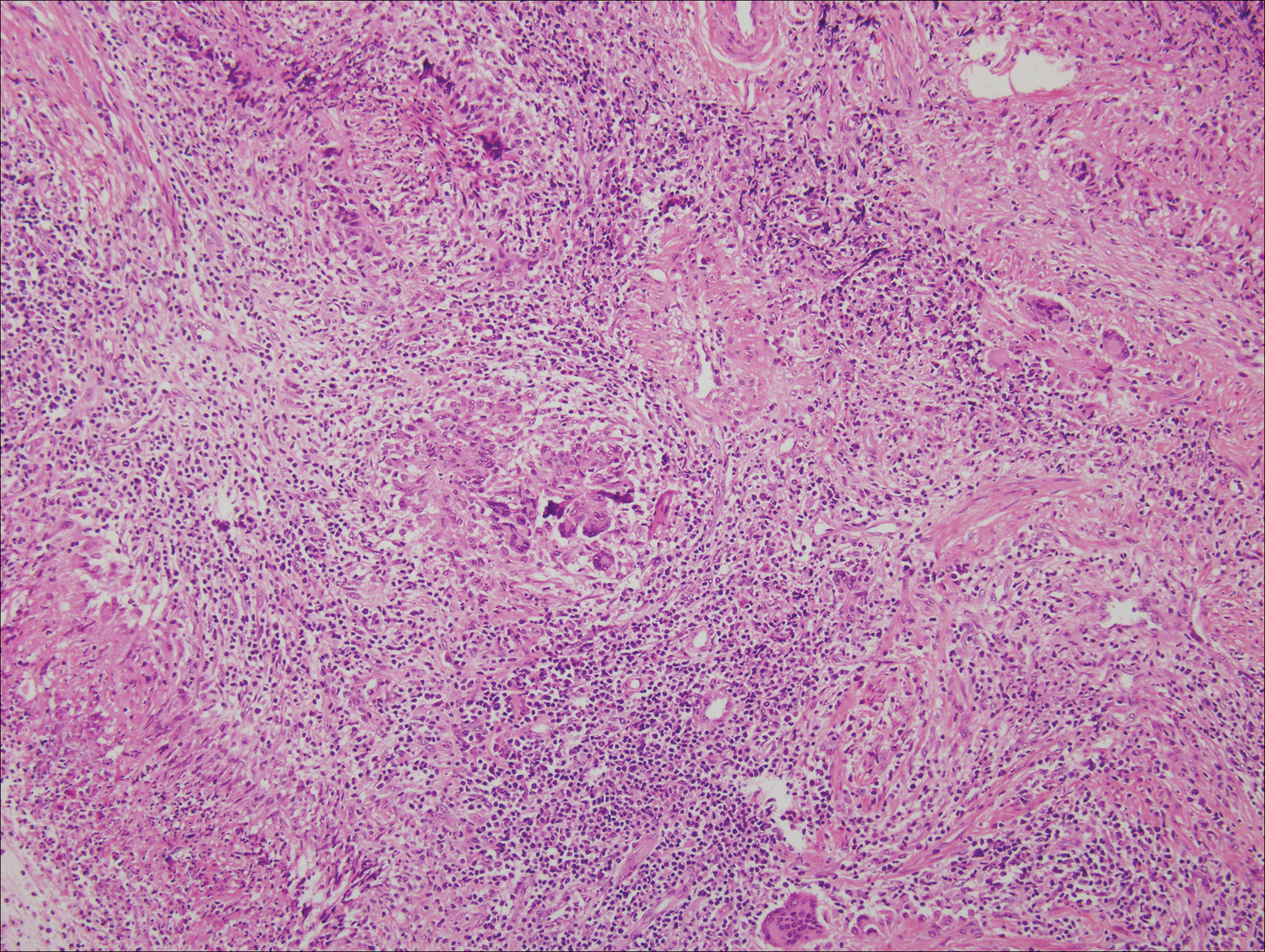

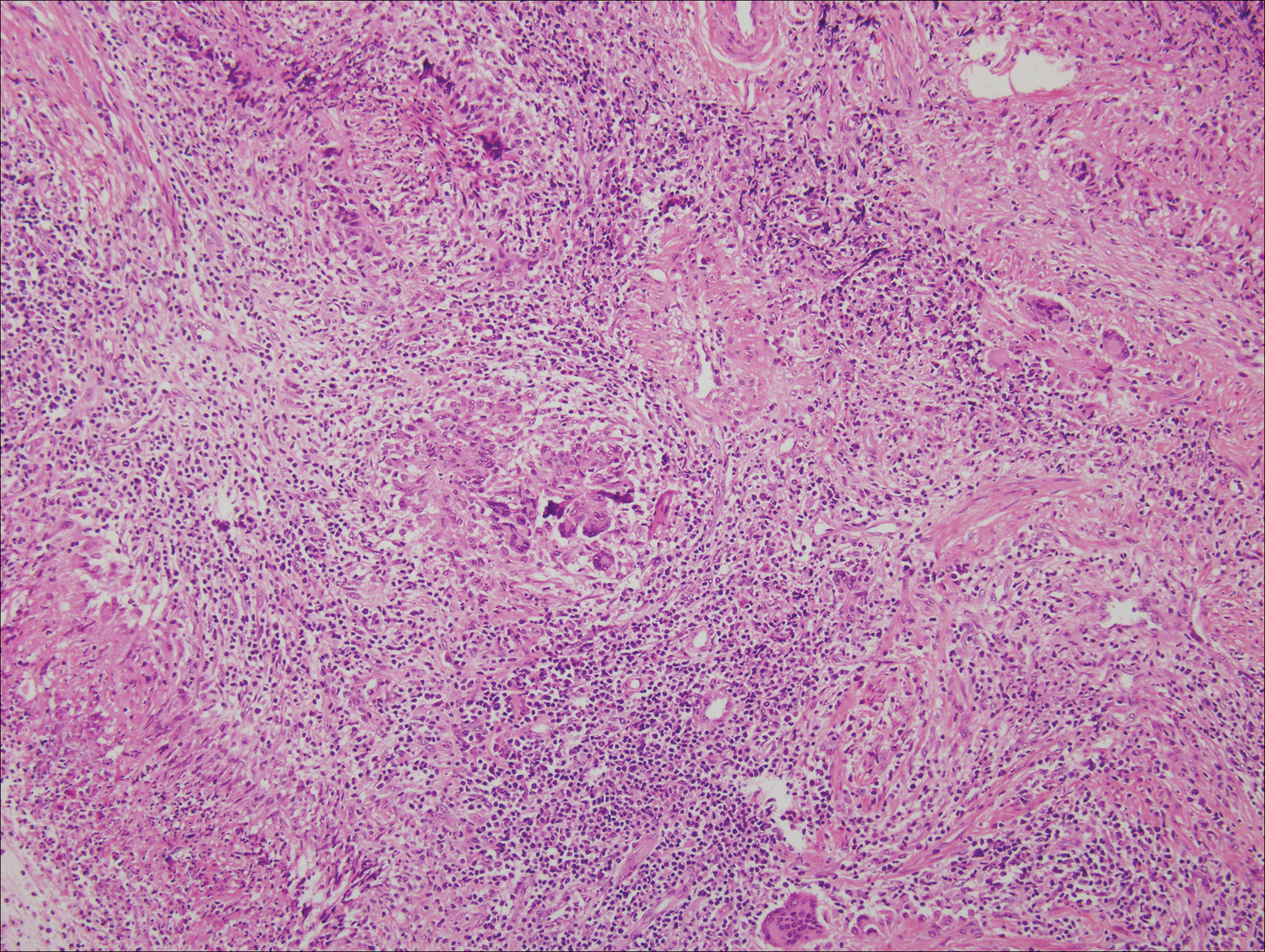

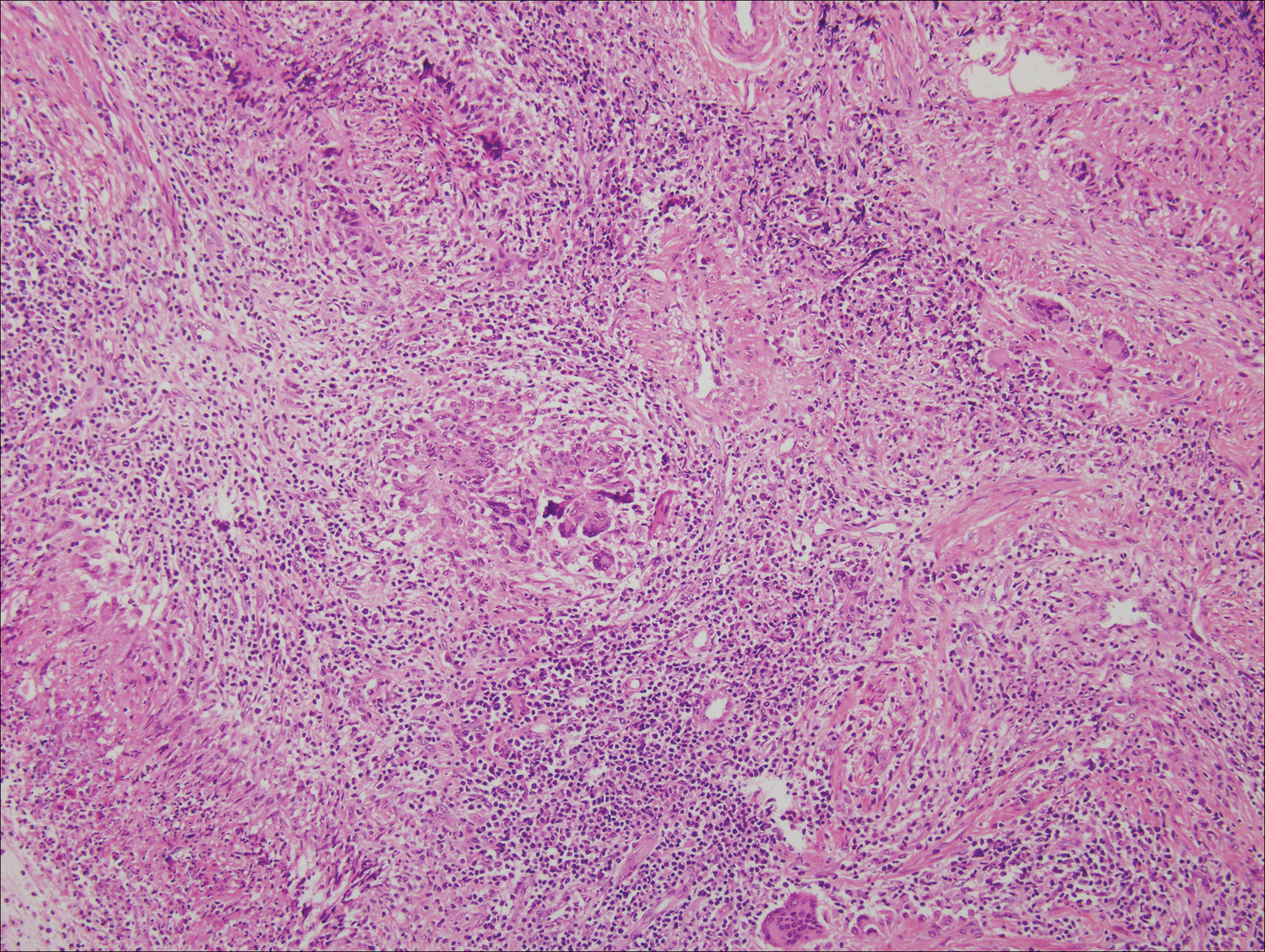

Histologic findings in sarcoidosis generally are independent of the respective organ and clinical disease presentation. The epidermis usually remains unchanged, whereas the dermis shows a superficial and deep nodular granulomatous infiltrate. Granulomas consist of epithelioid cells with only few giant cells and no surrounding lymphocytes or a very sparse lymphocytic infiltrate ("naked" granuloma)(Figure 1). Foreign bodies, including silica, are known to be able to induce sarcoid granulomas, especially in patients with sarcoidosis. A sarcoidal reaction in long-standing scar tissue points to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.10

Cutaneous tuberculosis primarily is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and less frequently Mycobacterium bovis.11,12 The manifestations of cutaneous tuberculosis depends on various factors such as the type of infection, mode of dissemination, host immunity, and whether it is a first-time infection or a recurrence. In Europe, the head and neck regions are most frequently affected.13 Lesions present as red-brown papules coalescing into a plaque. The tissue, especially in central parts of the lesion, is fragile (probe phenomenon). Diascopy shows the typical apple jelly-like color.

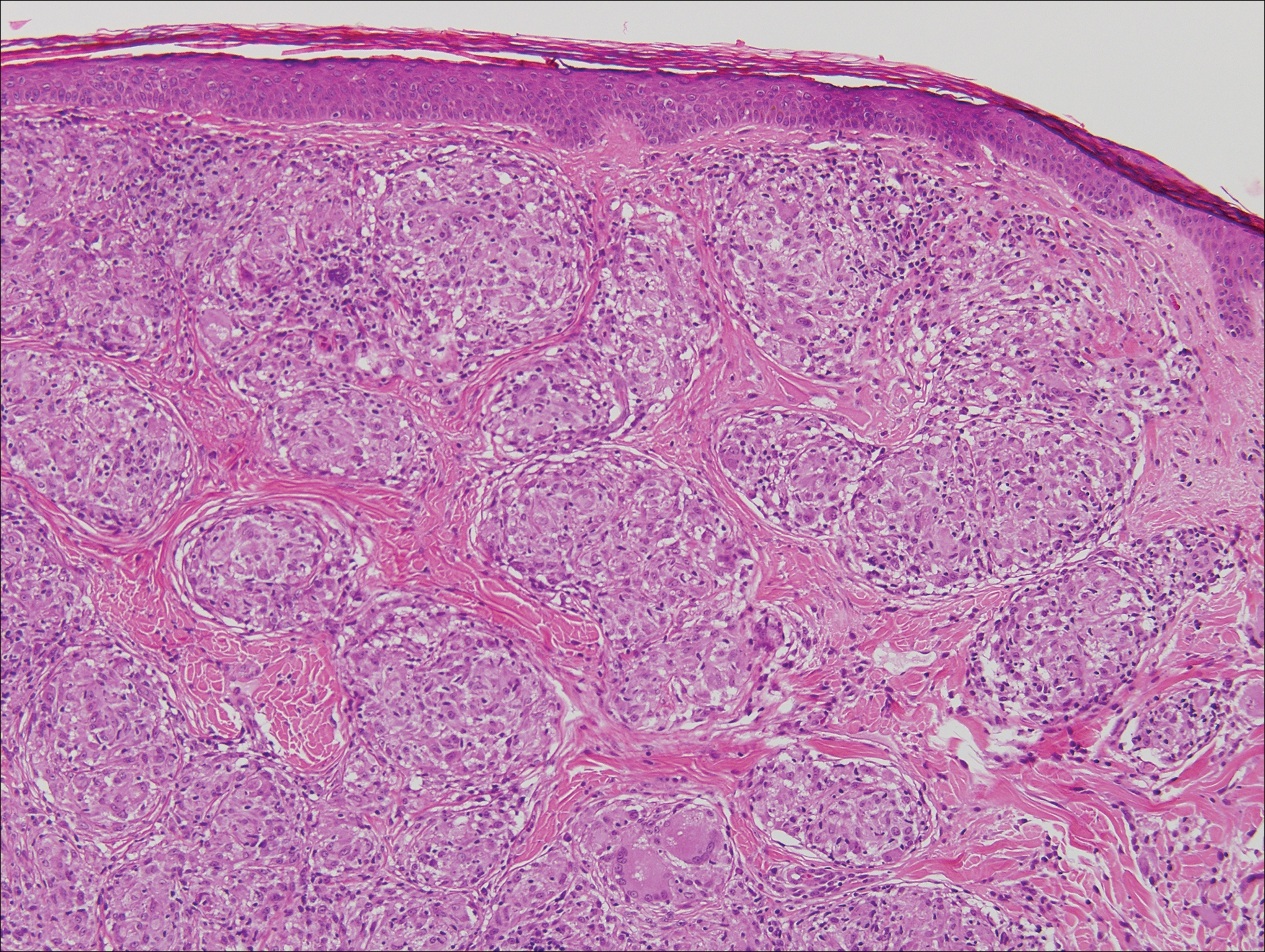

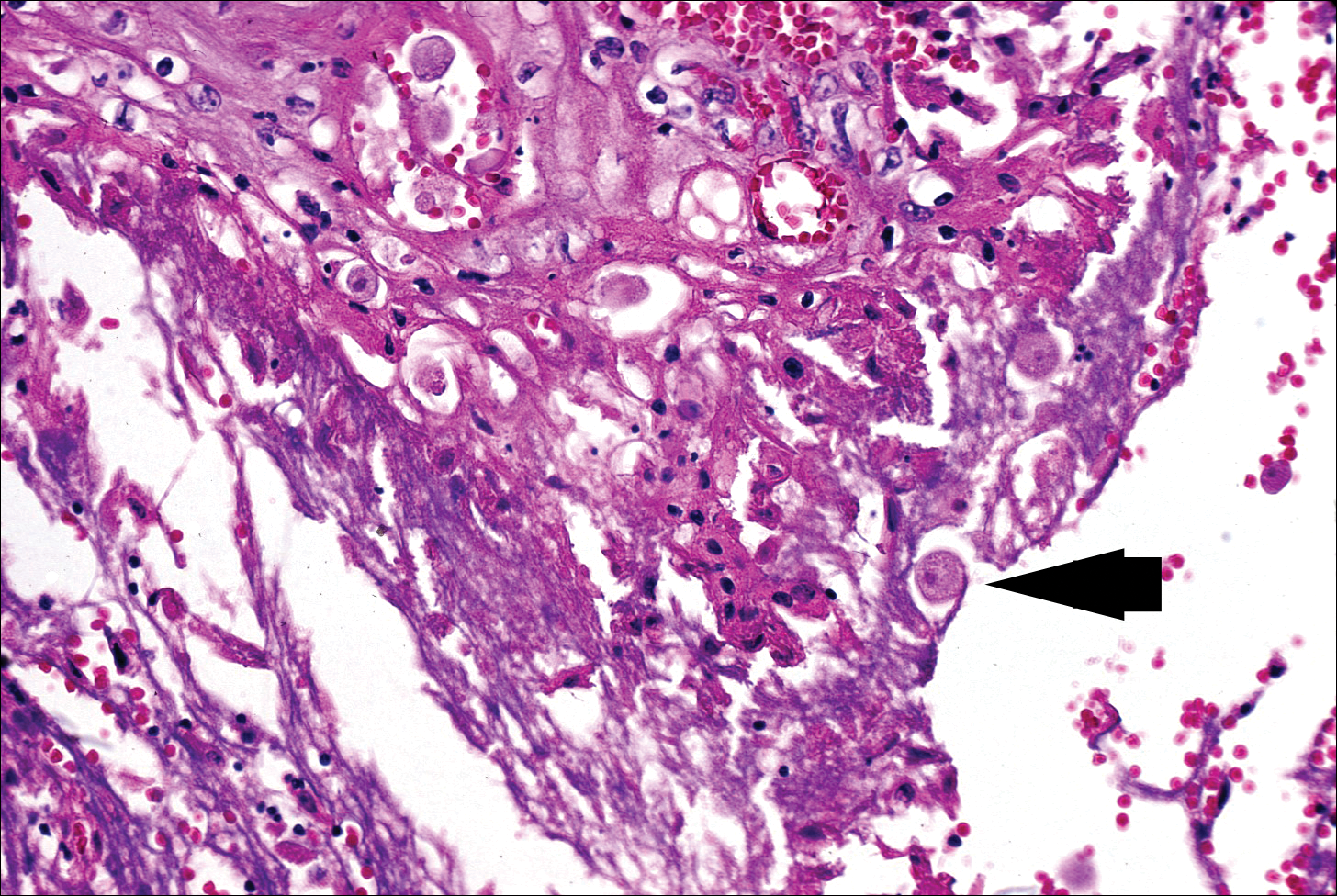

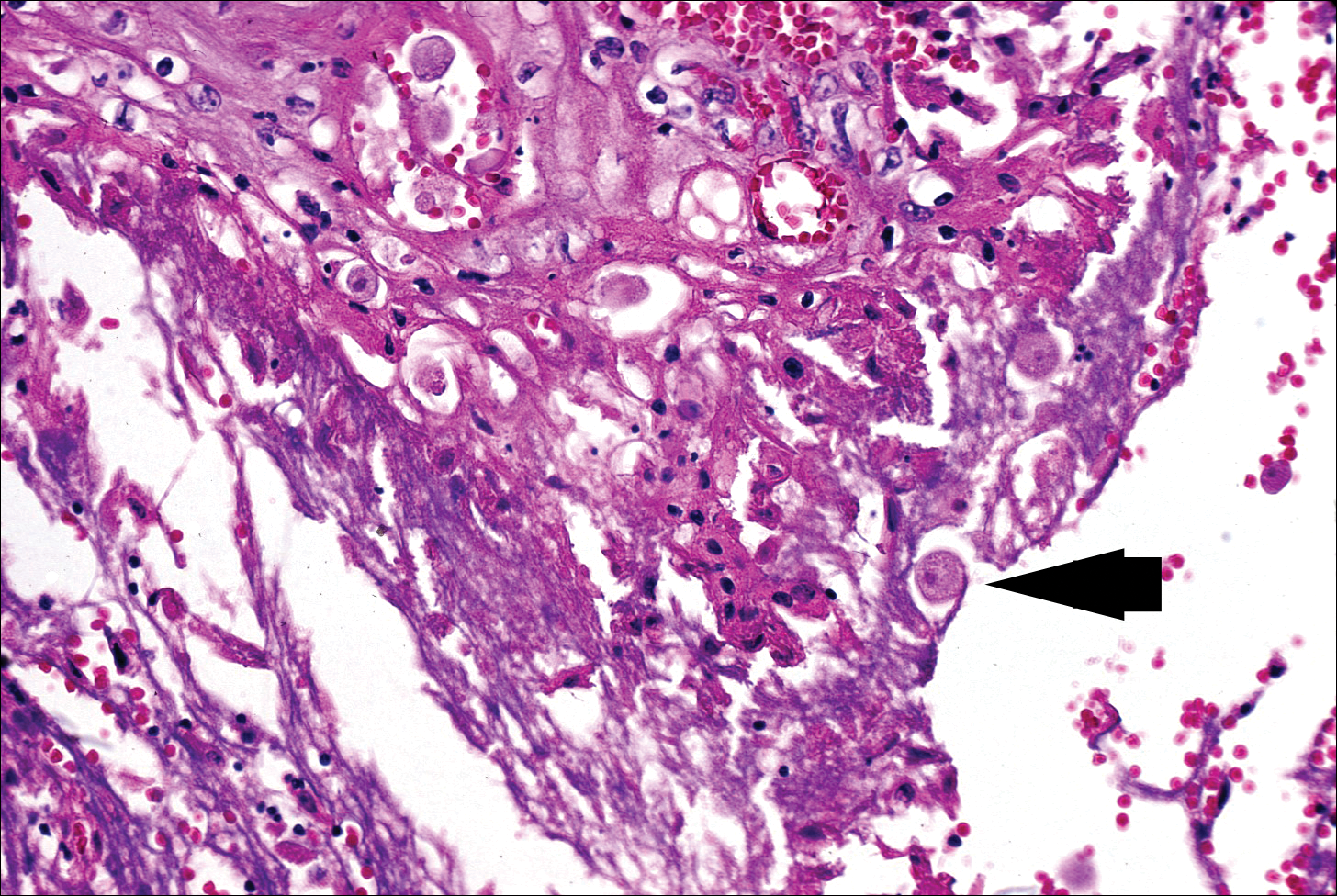

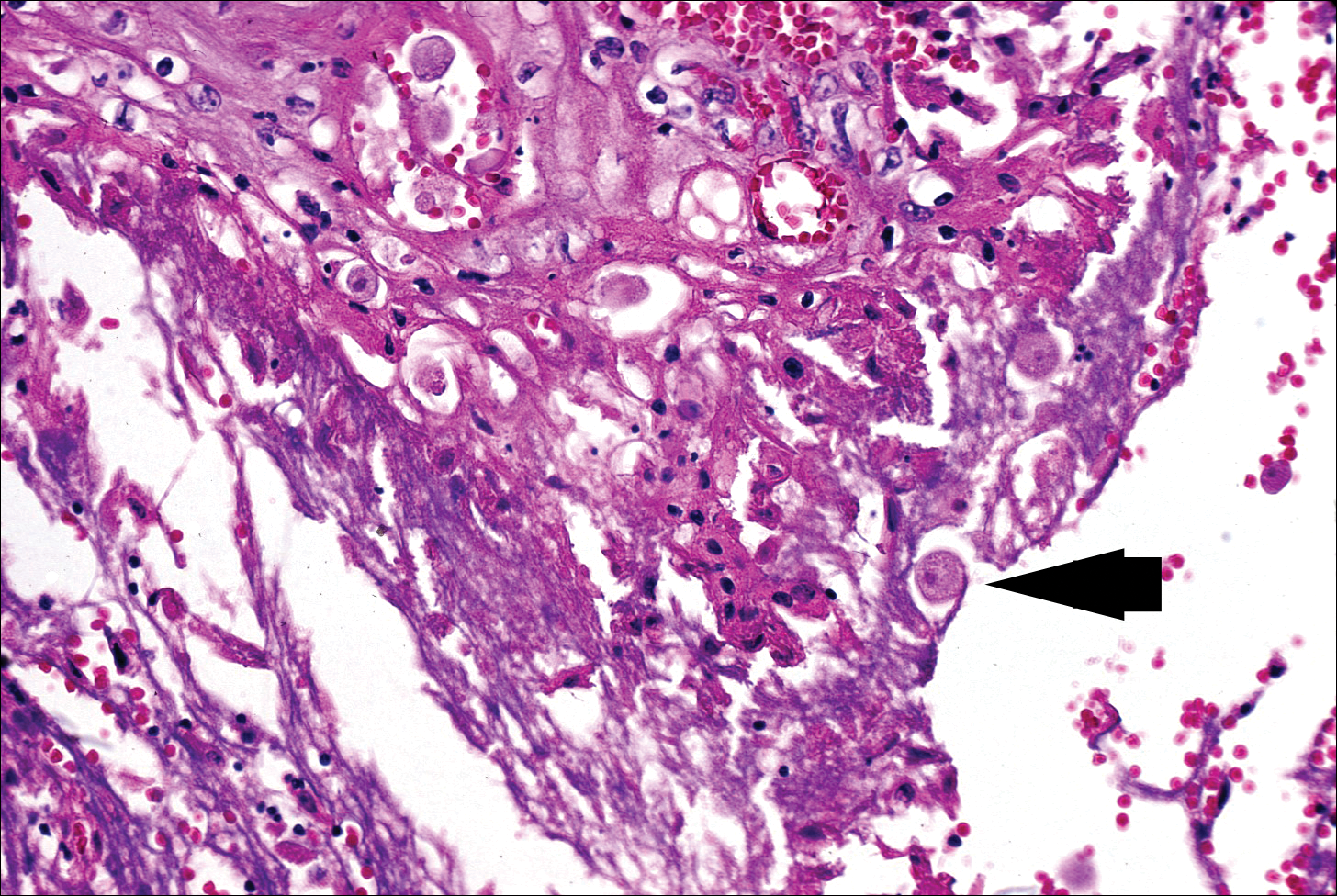

Histologically, cutaneous tuberculosis is characterized by typical tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid cells and Langhans giant cells at the center surrounded by lymphocytes (Figure 2). Caseous necrosis as well as fibrosis may occur,14,15 and the granulomas tend to coalesce.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis, is a complex, multisystemic disease with varying manifestations. The condition has been defined as a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the upper and lower respiratory tracts and necrotizing vasculitis affecting predominantly small- to medium-sized vessels.16 The etiology of GPA is thought to be linked to environmental and infectious triggers inciting onset of disease in genetically predisposed individuals. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies play an important role in the pathogenesis of this disease. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to GPA can present as papules, nodules, palpable purpura, ulcers resembling pyoderma gangrenosum, or necrotizing lesions leading to gangrene.17

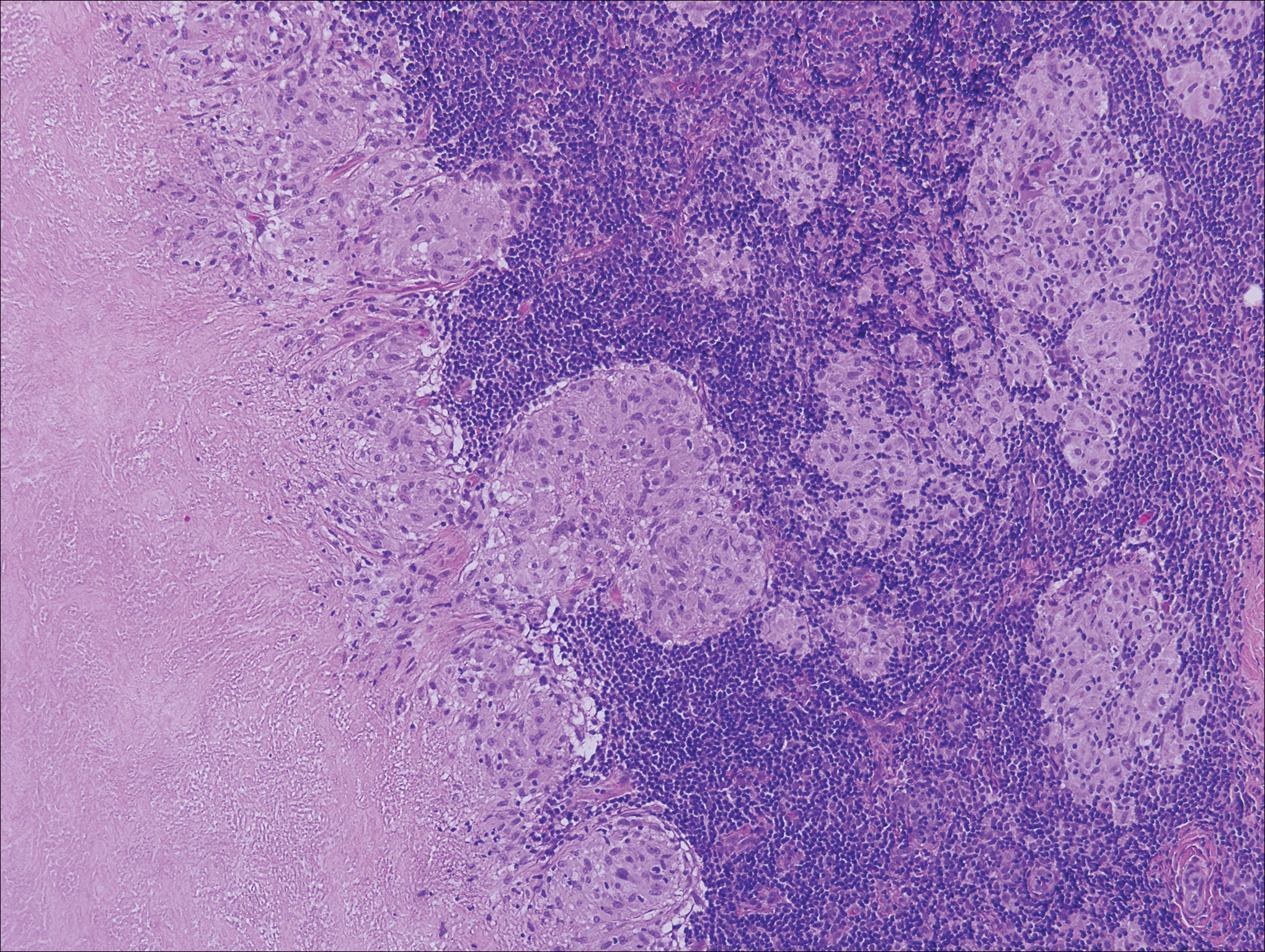

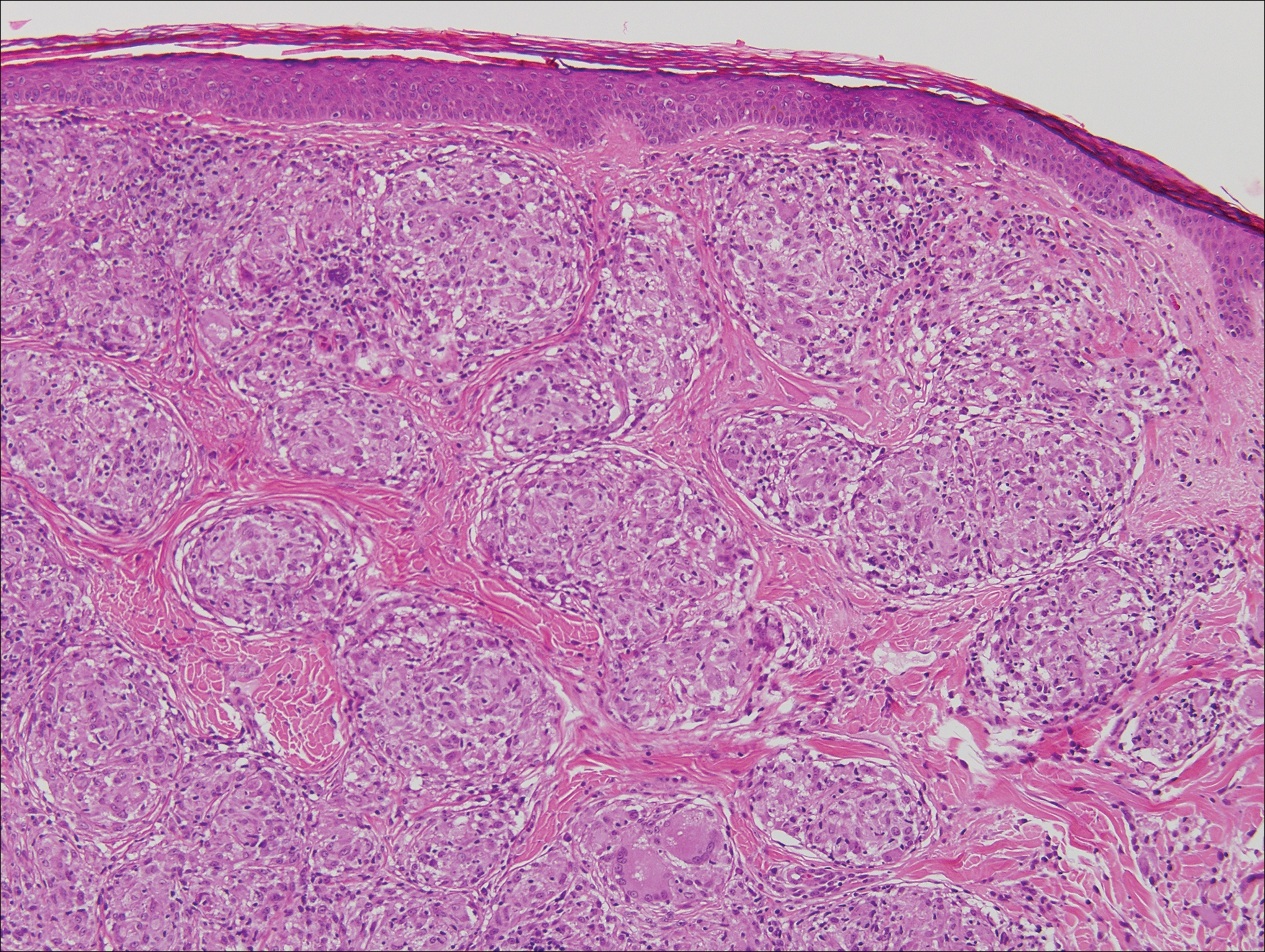

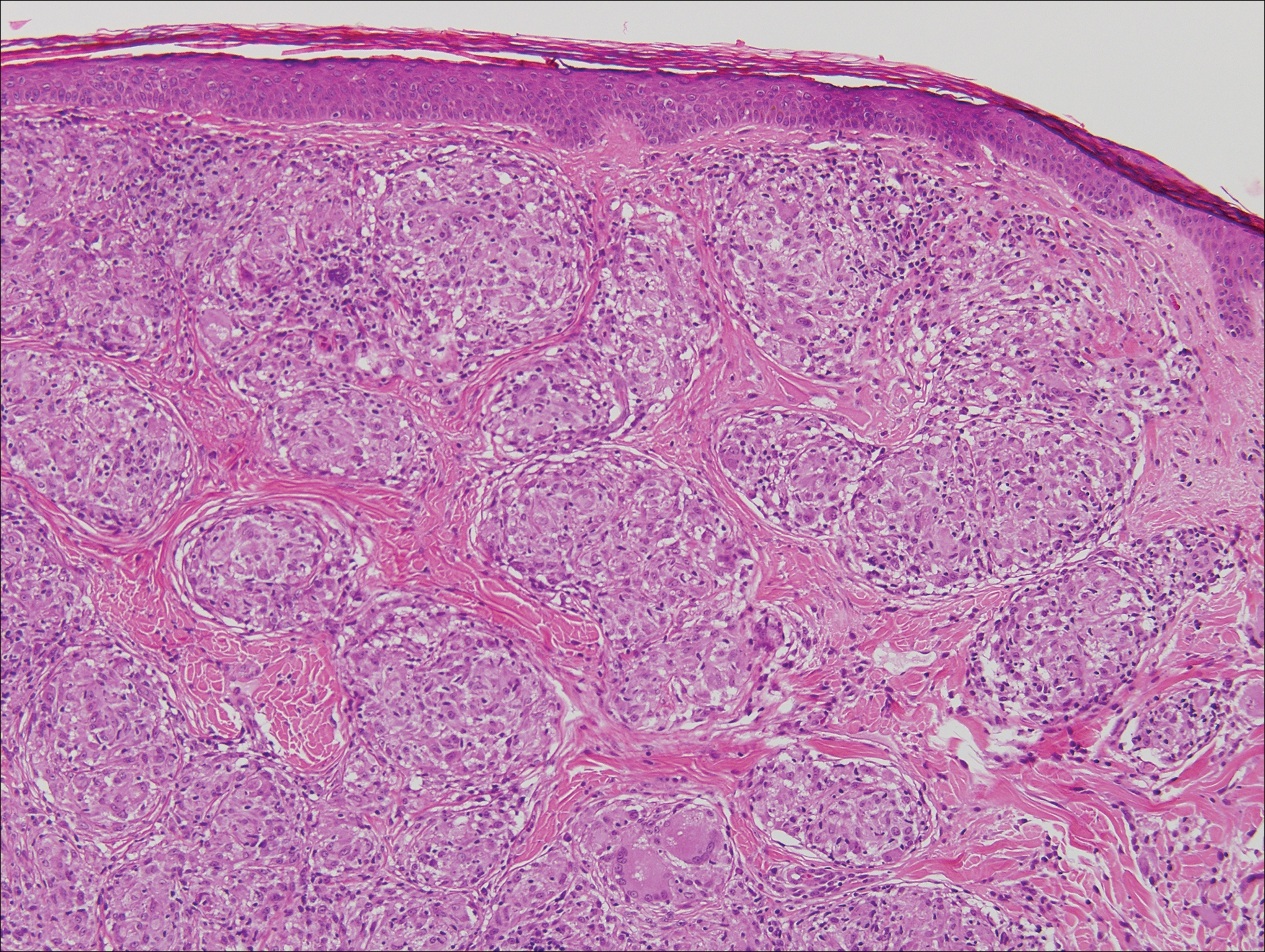

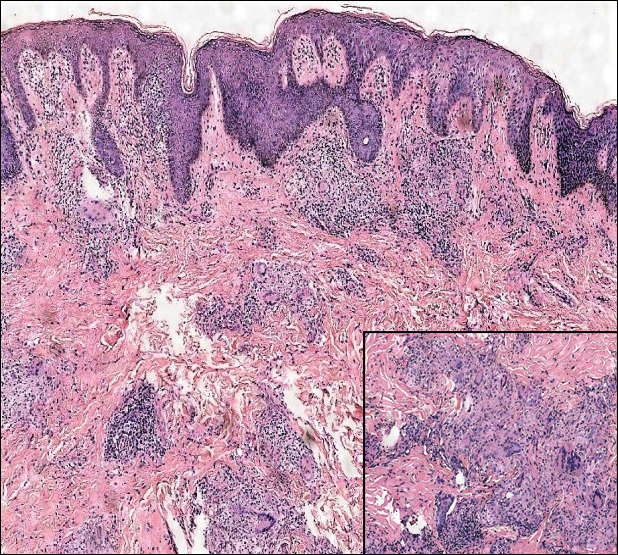

The predominant histopathologic pattern in cutaneous lesions of GPA is leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which is present in up to 50% of biopsies.18 Characteristic findings that aid in establishing the diagnosis include histologic evidence of focal necrosis, fibrinoid degeneration, palisading granuloma surrounding neutrophils (Figure 3), and granulomatous vasculitis involving muscular vessel walls.19 Nonpalisading foci of necrosis or fibrinoid degeneration may precede the development of the typical palisading granuloma.20

The typical histopathologic pattern of cutaneous amebiasis is ulceration with vascular necrosis (Figure 4).21 The organisms have prominent round nuclei and nucleoli and the cytoplasm may have a scalloped border.

- Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Landmark article Oct 25, 1932. regional ileitis. a pathologic and clinical entity. by Burril B. Crohn, Leon Gonzburg and Gordon D. Oppenheimer. JAMA. 1984;251:73-79.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Weedon D. Miscellaneous conditions. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:554.

- Samitz MH, Dana Jr AS, Rosenberg P. Cutaneous vasculitis in association with Crohn's disease. Cutis. 1970;6:51-56.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn's disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder: a review [published online January 3, 2017]. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150.

- Mahony J, Helms SE, Brodell RT. The sarcoidal granuloma: a unifying hypothesis for an enigmatic response. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:654-659.

- Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, et al. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003.

- Fernandez-Faith E, McDonnell J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: differential diagnosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:276-287.

- Walsh NM, Hanly JG, Tremaine R, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and foreign bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:203-207.

- Semaan R, Traboulsi R, Kanj S. Primary Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex cutaneous infection: report of two cases and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:472-477.

- Lai-Cheong JE, Perez A, Tang V, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of tuberculosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:461-466.

- Marcoval J, Servitje O, Moreno A, et al. Lupus vulgaris. clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic study of 10 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:404-407.

- Tronnier M, Wolff H. Dermatosen mit granulomatöser Entzündung. Histopathologie der Haut. In: Kerl H, Garbe C, Cerroni L, et al, eds. New York, NY: Springer; 2003.

- Min KW, Ko JY, Park CK. Histopathological spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:582-595.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1-11.

- Comfere NI, Macaron NC, Gibson LE. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener's granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 patients and correlation to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody status. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:739-747.

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Berti E. Skin involvement in cutaneous and systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:467-476.

- Bramsiepe I, Danz B, Heine R, et al. Primary cutaneous manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;27:1429-1432.

- Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener's granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

- Guidry JA, Downing C, Tyring SK. Deep fungal infections, blastomycosis-like pyoderma, and granulomatous sexually transmitted infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:595-607.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD), a chronic inflammatory granulomatous disease of the gastrointestinal tract, has a wide spectrum of presentations.1 The condition may affect the vulva, perineum, or perianal skin by direct extension from the gastrointestinal tract or may appear as a separate and distinct cutaneous focus of disease referred to as metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2

Cutaneous lesions of MCD include ulcers, fissures, sinus tracts, abscesses, and vegetative plaques, which typically extend in continuity with sites of intra-abdominal disease to the perineum, buttocks, or abdominal wall, as well as ostomy sites or incisional scars. Erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum are the most common nonspecific cutaneous manifestations. Other cutaneous lesions described in CD include polyarteritis nodosa, psoriasis, erythema multiforme, erythema elevatum diutinum, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, acne fulminans, pyoderma faciale, neutrophilic lobular panniculitis, granulomatous vasculitis, and porokeratosis.3

Perianal skin is the most common site of cutaneous involvement in individuals with CD. It is a marker of more severe disease and is associated with multiple surgical interventions and frequent relapses and has been reported in 22% of patients with CD.4 Most already had an existing diagnosis of gastrointestinal CD, which was active in one-third of individuals; however, 20% presented with disease at nongastrointestinal sites 2 months to 4 years prior to developing the gastrointestinal CD manifestations.5 Our patient presented with lesions on the perianal skin of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea. A colonoscopy demonstrated shallow ulcers involving the ileocecal portion of the gut, colon, and rectum. A biopsy from intestinal mucosal tissue showed acute and chronic inflammation with necrosis mixed with granulomatous inflammation, suggestive of CD.

Microscopically, the dominant histologic features of MCD are similar to those of bowel lesions, including an inflammatory infiltrate commonly consisting of sterile noncaseating sarcoidal granulomas, foreign body and Langhans giant cells, epithelioid histiocytes, and plasma cells surrounded by numerous mononuclear cells within the dermis with occasional extension into the subcutis (quiz image). Less common features include collagen degeneration, an infiltrate rich in eosinophils, dermal edema, and mixed lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis.6

Metastatic CD often is misdiagnosed. A detailed history and physical examination may help narrow the differential; however, biopsy is necessary to establish a diagnosis of MCD. The histologic differential diagnosis of sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation of genital skin includes sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, leprosy or other mycobacterial and parasitic infection, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and granulomatous infiltrate associated with certain exogenous material (eg, silica, zirconium, beryllium, tattoo pigment).

Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan disease that most frequently affects the lungs, skin, and lymph nodes. Its etiopathogenesis has not been clearly elucidated.7 Cutaneous lesions are present in 20% to 35% of patients.8 Given the wide variability of clinical manifestations, cutaneous sarcoidosis is another one of the great imitators. Cutaneous lesions are classified as specific and nonspecific depending on the presence of noncaseating granulomas on histologic studies and include maculopapules, plaques, nodules, lupus pernio, scar infiltration, alopecia, ulcerative lesions, and hypopigmentation. The most common nonspecific lesion of cutaneous sarcoidosis is erythema nodosum. Other manifestations include calcifications, prurigo, erythema multiforme, nail clubbing, and Sweet syndrome.9

Histologic findings in sarcoidosis generally are independent of the respective organ and clinical disease presentation. The epidermis usually remains unchanged, whereas the dermis shows a superficial and deep nodular granulomatous infiltrate. Granulomas consist of epithelioid cells with only few giant cells and no surrounding lymphocytes or a very sparse lymphocytic infiltrate ("naked" granuloma)(Figure 1). Foreign bodies, including silica, are known to be able to induce sarcoid granulomas, especially in patients with sarcoidosis. A sarcoidal reaction in long-standing scar tissue points to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.10

Cutaneous tuberculosis primarily is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and less frequently Mycobacterium bovis.11,12 The manifestations of cutaneous tuberculosis depends on various factors such as the type of infection, mode of dissemination, host immunity, and whether it is a first-time infection or a recurrence. In Europe, the head and neck regions are most frequently affected.13 Lesions present as red-brown papules coalescing into a plaque. The tissue, especially in central parts of the lesion, is fragile (probe phenomenon). Diascopy shows the typical apple jelly-like color.

Histologically, cutaneous tuberculosis is characterized by typical tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid cells and Langhans giant cells at the center surrounded by lymphocytes (Figure 2). Caseous necrosis as well as fibrosis may occur,14,15 and the granulomas tend to coalesce.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis, is a complex, multisystemic disease with varying manifestations. The condition has been defined as a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the upper and lower respiratory tracts and necrotizing vasculitis affecting predominantly small- to medium-sized vessels.16 The etiology of GPA is thought to be linked to environmental and infectious triggers inciting onset of disease in genetically predisposed individuals. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies play an important role in the pathogenesis of this disease. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to GPA can present as papules, nodules, palpable purpura, ulcers resembling pyoderma gangrenosum, or necrotizing lesions leading to gangrene.17

The predominant histopathologic pattern in cutaneous lesions of GPA is leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which is present in up to 50% of biopsies.18 Characteristic findings that aid in establishing the diagnosis include histologic evidence of focal necrosis, fibrinoid degeneration, palisading granuloma surrounding neutrophils (Figure 3), and granulomatous vasculitis involving muscular vessel walls.19 Nonpalisading foci of necrosis or fibrinoid degeneration may precede the development of the typical palisading granuloma.20

The typical histopathologic pattern of cutaneous amebiasis is ulceration with vascular necrosis (Figure 4).21 The organisms have prominent round nuclei and nucleoli and the cytoplasm may have a scalloped border.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Crohn Disease

Crohn disease (CD), a chronic inflammatory granulomatous disease of the gastrointestinal tract, has a wide spectrum of presentations.1 The condition may affect the vulva, perineum, or perianal skin by direct extension from the gastrointestinal tract or may appear as a separate and distinct cutaneous focus of disease referred to as metastatic Crohn disease (MCD).2

Cutaneous lesions of MCD include ulcers, fissures, sinus tracts, abscesses, and vegetative plaques, which typically extend in continuity with sites of intra-abdominal disease to the perineum, buttocks, or abdominal wall, as well as ostomy sites or incisional scars. Erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum are the most common nonspecific cutaneous manifestations. Other cutaneous lesions described in CD include polyarteritis nodosa, psoriasis, erythema multiforme, erythema elevatum diutinum, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, acne fulminans, pyoderma faciale, neutrophilic lobular panniculitis, granulomatous vasculitis, and porokeratosis.3

Perianal skin is the most common site of cutaneous involvement in individuals with CD. It is a marker of more severe disease and is associated with multiple surgical interventions and frequent relapses and has been reported in 22% of patients with CD.4 Most already had an existing diagnosis of gastrointestinal CD, which was active in one-third of individuals; however, 20% presented with disease at nongastrointestinal sites 2 months to 4 years prior to developing the gastrointestinal CD manifestations.5 Our patient presented with lesions on the perianal skin of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea. A colonoscopy demonstrated shallow ulcers involving the ileocecal portion of the gut, colon, and rectum. A biopsy from intestinal mucosal tissue showed acute and chronic inflammation with necrosis mixed with granulomatous inflammation, suggestive of CD.

Microscopically, the dominant histologic features of MCD are similar to those of bowel lesions, including an inflammatory infiltrate commonly consisting of sterile noncaseating sarcoidal granulomas, foreign body and Langhans giant cells, epithelioid histiocytes, and plasma cells surrounded by numerous mononuclear cells within the dermis with occasional extension into the subcutis (quiz image). Less common features include collagen degeneration, an infiltrate rich in eosinophils, dermal edema, and mixed lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis.6

Metastatic CD often is misdiagnosed. A detailed history and physical examination may help narrow the differential; however, biopsy is necessary to establish a diagnosis of MCD. The histologic differential diagnosis of sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation of genital skin includes sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, leprosy or other mycobacterial and parasitic infection, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and granulomatous infiltrate associated with certain exogenous material (eg, silica, zirconium, beryllium, tattoo pigment).

Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan disease that most frequently affects the lungs, skin, and lymph nodes. Its etiopathogenesis has not been clearly elucidated.7 Cutaneous lesions are present in 20% to 35% of patients.8 Given the wide variability of clinical manifestations, cutaneous sarcoidosis is another one of the great imitators. Cutaneous lesions are classified as specific and nonspecific depending on the presence of noncaseating granulomas on histologic studies and include maculopapules, plaques, nodules, lupus pernio, scar infiltration, alopecia, ulcerative lesions, and hypopigmentation. The most common nonspecific lesion of cutaneous sarcoidosis is erythema nodosum. Other manifestations include calcifications, prurigo, erythema multiforme, nail clubbing, and Sweet syndrome.9

Histologic findings in sarcoidosis generally are independent of the respective organ and clinical disease presentation. The epidermis usually remains unchanged, whereas the dermis shows a superficial and deep nodular granulomatous infiltrate. Granulomas consist of epithelioid cells with only few giant cells and no surrounding lymphocytes or a very sparse lymphocytic infiltrate ("naked" granuloma)(Figure 1). Foreign bodies, including silica, are known to be able to induce sarcoid granulomas, especially in patients with sarcoidosis. A sarcoidal reaction in long-standing scar tissue points to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.10

Cutaneous tuberculosis primarily is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and less frequently Mycobacterium bovis.11,12 The manifestations of cutaneous tuberculosis depends on various factors such as the type of infection, mode of dissemination, host immunity, and whether it is a first-time infection or a recurrence. In Europe, the head and neck regions are most frequently affected.13 Lesions present as red-brown papules coalescing into a plaque. The tissue, especially in central parts of the lesion, is fragile (probe phenomenon). Diascopy shows the typical apple jelly-like color.

Histologically, cutaneous tuberculosis is characterized by typical tuberculoid granulomas with epithelioid cells and Langhans giant cells at the center surrounded by lymphocytes (Figure 2). Caseous necrosis as well as fibrosis may occur,14,15 and the granulomas tend to coalesce.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis, is a complex, multisystemic disease with varying manifestations. The condition has been defined as a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the upper and lower respiratory tracts and necrotizing vasculitis affecting predominantly small- to medium-sized vessels.16 The etiology of GPA is thought to be linked to environmental and infectious triggers inciting onset of disease in genetically predisposed individuals. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies play an important role in the pathogenesis of this disease. Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to GPA can present as papules, nodules, palpable purpura, ulcers resembling pyoderma gangrenosum, or necrotizing lesions leading to gangrene.17

The predominant histopathologic pattern in cutaneous lesions of GPA is leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which is present in up to 50% of biopsies.18 Characteristic findings that aid in establishing the diagnosis include histologic evidence of focal necrosis, fibrinoid degeneration, palisading granuloma surrounding neutrophils (Figure 3), and granulomatous vasculitis involving muscular vessel walls.19 Nonpalisading foci of necrosis or fibrinoid degeneration may precede the development of the typical palisading granuloma.20

The typical histopathologic pattern of cutaneous amebiasis is ulceration with vascular necrosis (Figure 4).21 The organisms have prominent round nuclei and nucleoli and the cytoplasm may have a scalloped border.

- Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Landmark article Oct 25, 1932. regional ileitis. a pathologic and clinical entity. by Burril B. Crohn, Leon Gonzburg and Gordon D. Oppenheimer. JAMA. 1984;251:73-79.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Weedon D. Miscellaneous conditions. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:554.

- Samitz MH, Dana Jr AS, Rosenberg P. Cutaneous vasculitis in association with Crohn's disease. Cutis. 1970;6:51-56.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn's disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder: a review [published online January 3, 2017]. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150.

- Mahony J, Helms SE, Brodell RT. The sarcoidal granuloma: a unifying hypothesis for an enigmatic response. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:654-659.

- Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, et al. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003.

- Fernandez-Faith E, McDonnell J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: differential diagnosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:276-287.

- Walsh NM, Hanly JG, Tremaine R, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and foreign bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:203-207.

- Semaan R, Traboulsi R, Kanj S. Primary Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex cutaneous infection: report of two cases and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:472-477.

- Lai-Cheong JE, Perez A, Tang V, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of tuberculosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:461-466.

- Marcoval J, Servitje O, Moreno A, et al. Lupus vulgaris. clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic study of 10 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:404-407.

- Tronnier M, Wolff H. Dermatosen mit granulomatöser Entzündung. Histopathologie der Haut. In: Kerl H, Garbe C, Cerroni L, et al, eds. New York, NY: Springer; 2003.

- Min KW, Ko JY, Park CK. Histopathological spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:582-595.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1-11.

- Comfere NI, Macaron NC, Gibson LE. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener's granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 patients and correlation to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody status. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:739-747.

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Berti E. Skin involvement in cutaneous and systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:467-476.

- Bramsiepe I, Danz B, Heine R, et al. Primary cutaneous manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;27:1429-1432.

- Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener's granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

- Guidry JA, Downing C, Tyring SK. Deep fungal infections, blastomycosis-like pyoderma, and granulomatous sexually transmitted infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:595-607.

- Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Landmark article Oct 25, 1932. regional ileitis. a pathologic and clinical entity. by Burril B. Crohn, Leon Gonzburg and Gordon D. Oppenheimer. JAMA. 1984;251:73-79.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn's disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Weedon D. Miscellaneous conditions. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:554.

- Samitz MH, Dana Jr AS, Rosenberg P. Cutaneous vasculitis in association with Crohn's disease. Cutis. 1970;6:51-56.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn's disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder: a review [published online January 3, 2017]. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150.

- Mahony J, Helms SE, Brodell RT. The sarcoidal granuloma: a unifying hypothesis for an enigmatic response. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:654-659.

- Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, et al. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2003.

- Fernandez-Faith E, McDonnell J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: differential diagnosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:276-287.

- Walsh NM, Hanly JG, Tremaine R, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and foreign bodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:203-207.

- Semaan R, Traboulsi R, Kanj S. Primary Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex cutaneous infection: report of two cases and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:472-477.

- Lai-Cheong JE, Perez A, Tang V, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of tuberculosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:461-466.

- Marcoval J, Servitje O, Moreno A, et al. Lupus vulgaris. clinical, histopathologic, and bacteriologic study of 10 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:404-407.

- Tronnier M, Wolff H. Dermatosen mit granulomatöser Entzündung. Histopathologie der Haut. In: Kerl H, Garbe C, Cerroni L, et al, eds. New York, NY: Springer; 2003.

- Min KW, Ko JY, Park CK. Histopathological spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:582-595.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1-11.

- Comfere NI, Macaron NC, Gibson LE. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener's granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 patients and correlation to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody status. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:739-747.

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Berti E. Skin involvement in cutaneous and systemic vasculitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:467-476.

- Bramsiepe I, Danz B, Heine R, et al. Primary cutaneous manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis [in German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;27:1429-1432.

- Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, et al. Cutaneous Wegener's granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605-612.

- Guidry JA, Downing C, Tyring SK. Deep fungal infections, blastomycosis-like pyoderma, and granulomatous sexually transmitted infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:595-607.

A 19-year-old man presented with a perianal condyloma acuminatum-like plaque of 2 years' duration and a 6-month history of diarrhea.

Hyperpigmented Papules and Plaques

The Diagnosis: Persistent Still Disease

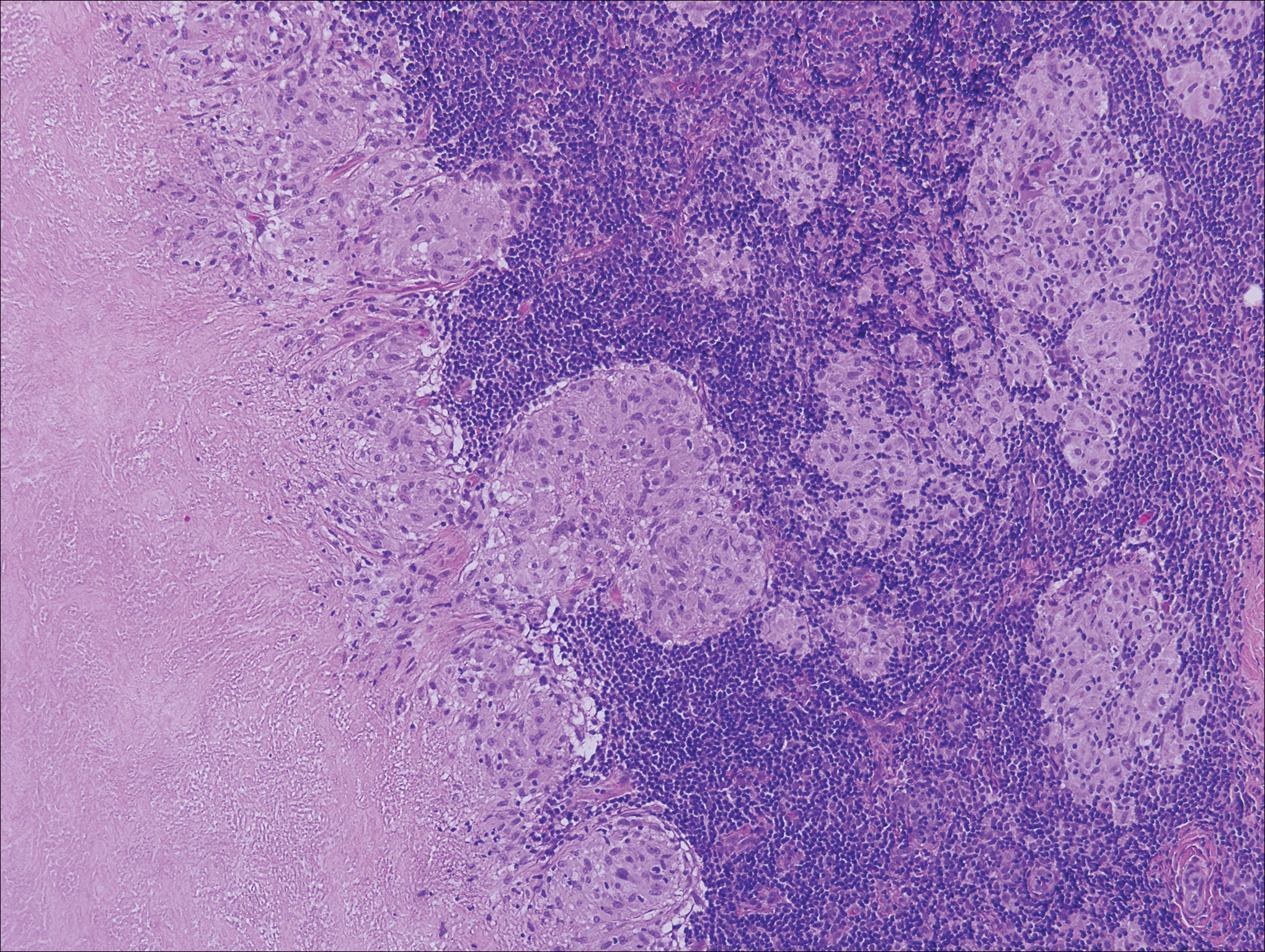

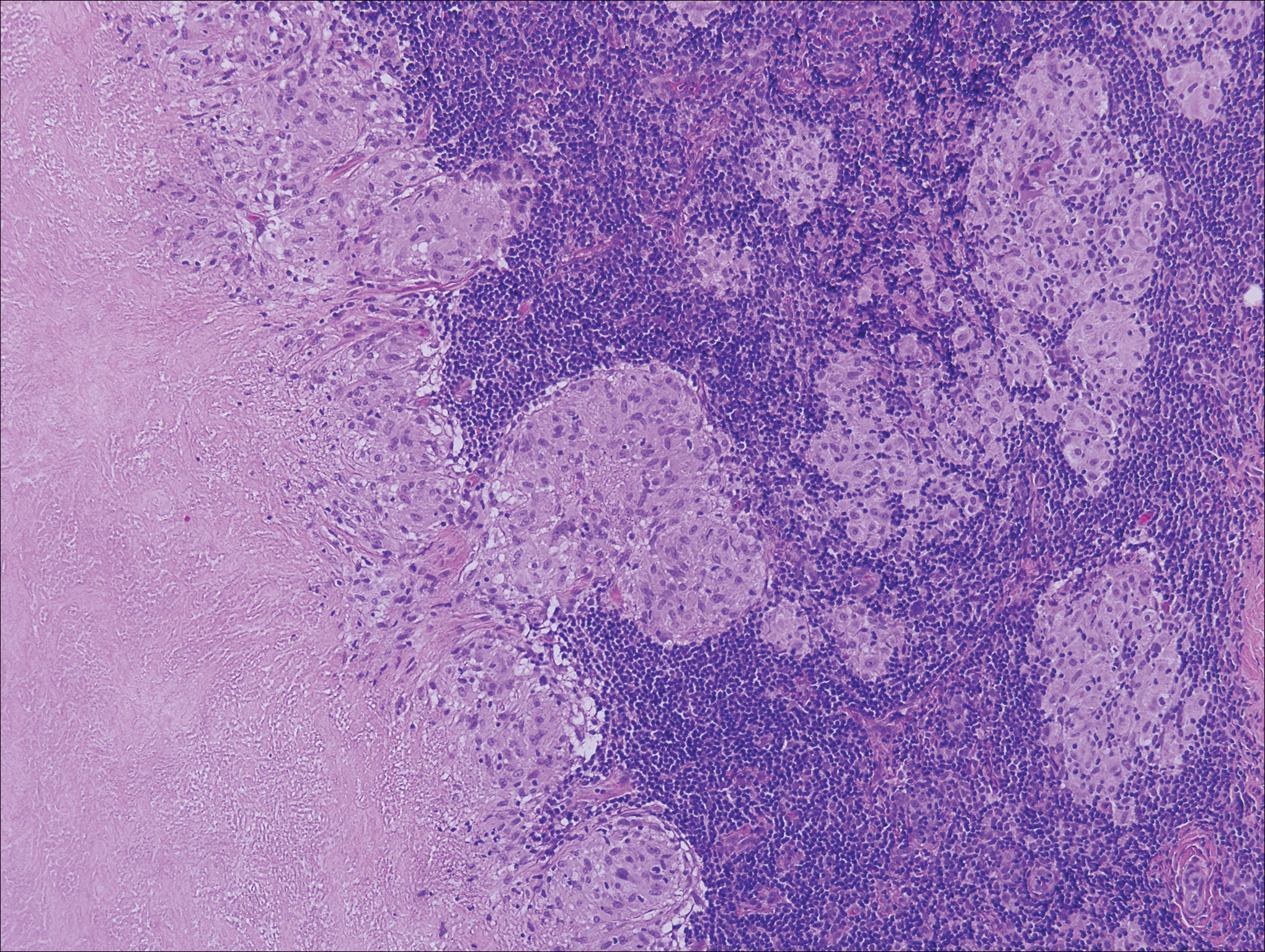

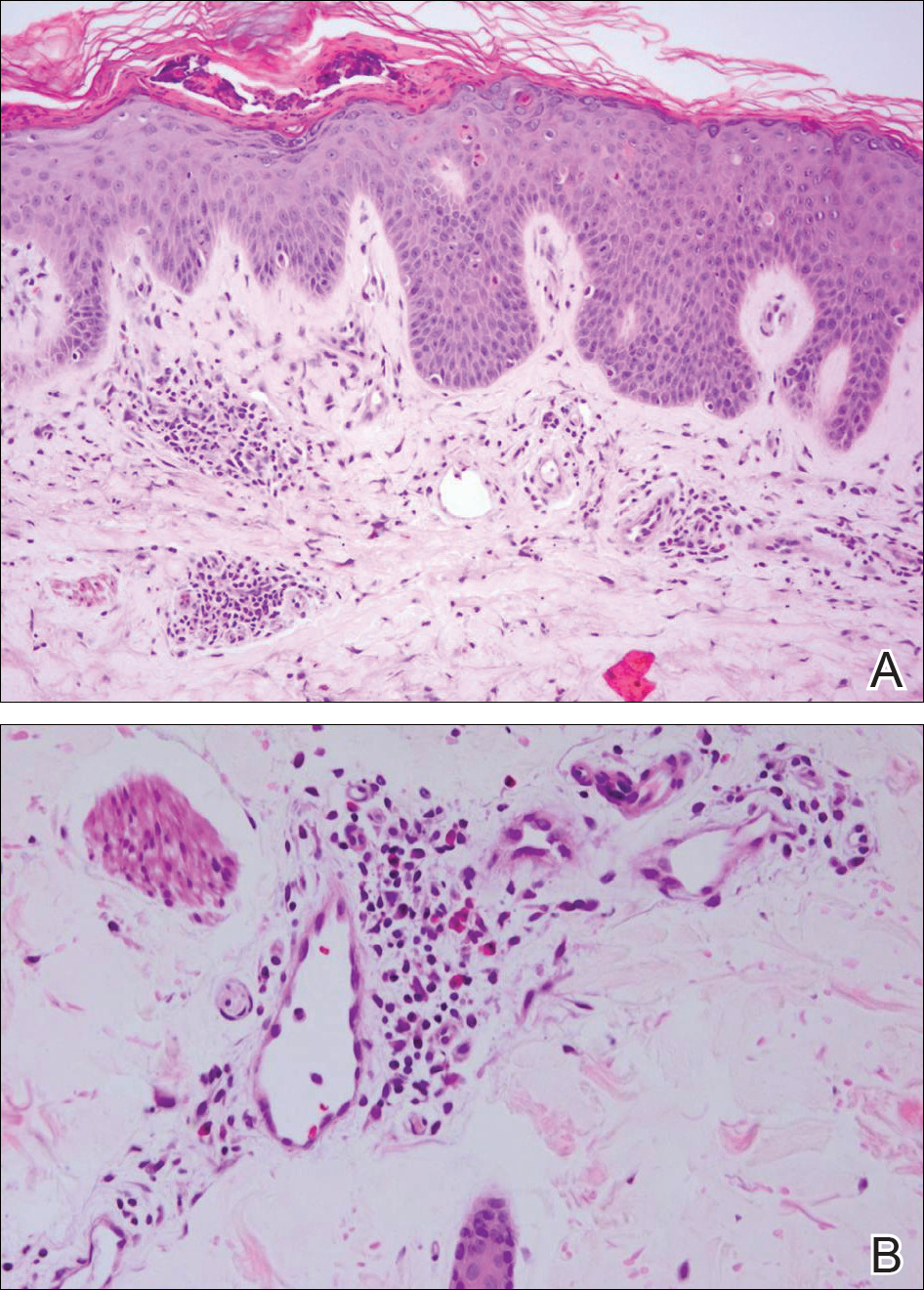

At the time of presentation, the patient had not taken systemic medications for a year. Laboratory studies revealed leukocytosis with neutrophilia and a serum ferritin level of 5493 ng/mL (reference range, 15-200 ng/mL). Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody serologies were within reference range. Microbiologic workup was negative. Lymph node and bone marrow biopsies were negative for a lymphoproliferative disorder. Skin biopsies were performed on the back and forearm. Histologic evaluation revealed orthokeratosis, slight acanthosis, and dyskeratosis confined to the upper layers of the epidermis without evidence of interface dermatitis. There was a mixed perivascular infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and neutrophils with no attendant vasculitic change (Figure).

The patient was discharged on prednisone and seen for outpatient follow-up weeks later. Six weeks later, the cutaneous eruption remained unchanged. The patient was unable to start other systemic medications due to lack of insurance and ineligibility for the local patient-assistance program; he was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Adult-onset Still disease is a rare, systemic, inflammatory condition with a broad spectrum of clinical presentations.1-3 Still disease affects all age groups, and children with Still disease (<16 years) usually have a concurrent diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (formerly known as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis).1,2,4 Still disease preferentially affects adolescents and adults aged 16 to 35 years, with more than 75% of new cases occurring in this age range.1 Worldwide, the incidence and prevalence of Still disease is disputed with no conclusive rates established.1,3

Still disease is characterized by 4 cardinal signs: high spiking fevers (temperature, ≥39°C); leukocytosis with a predominance of neutrophils (≥10,000 cells/mm3 with ≥80% neutrophils); arthralgia or arthritis; and an evanescent, nonpruritic, salmon-colored morbilliform eruption of the skin, typically on the trunk or extremities.2 Histologic evaluation of the classic Still disease eruption displays perivascular inflammation of the superficial dermis with infiltration by lymphocytes and histiocytes.3

In 1992, major and minor diagnostic criteria were established for adult-onset Still disease. For diagnosis, patients must meet 5 criteria, including 2 major criteria.5 Major criteria include arthralgia or arthritis present for more than 2 weeks, fever (temperature, >39°C) for at least 1 week, the classic Still disease morbilliform eruption (ie, salmon colored, evanescent, morbilliform), and leukocytosis with more than 80% neutrophils. Minor criteria include sore throat, lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly, negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody serologies, and abnormal liver function (defined as elevated transaminases).5 Although not included in the diagnostic criteria, there have been reports of elevated serum ferritin levels in patients with Still disease, a finding that potentially is useful in distinguishing between active and inactive rheumatic conditions.6,7

Several case reports have described persistent Still disease, a subtype of Still disease in which patients present with brown-red, persistent, pruritic macules, papules, and plaques that are widespread and oddly shaped.8,9 Histologically, this subtype is characterized by necrotic keratinocytes in the epidermis and dermal perivascular inflammation composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes.10 This histology differs from classic Still disease in that the latter typically does not have superficial epidermal dyskeratosis. Our case is consistent with reports of persistent Still disease.

Although the etiology of Still disease remains to be elucidated, HLA-B17, -B18, -B35, and -DR2 have been associated with the disease.3 Furthermore, helper T cell TH1, IL-2, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor α have been implicated in disease pathology, enabling the use of newer targeted pharmacologic therapies. Canakinumab, an IL-1β inhibitor, has been found to improve arthritis, fever, and rash in patients with Still disease.11 These findings are particularly encouraging for patients who have not experienced improvement with traditional antirheumatic drugs, such as our patient who was not steroid responsive.3

Although a salmon-colored, evanescent, morbilliform eruption in the context of other systemic signs and symptoms readily evokes consideration of Still disease, the less common fixed cutaneous eruption seen in our case may evade accurate diagnosis. Our case aims to increase awareness of this unusual and rare subtype of the cutaneous eruption of Still disease, as a timely diagnosis may prevent potentially life-threatening sequelae including cardiopulmonary disease and respiratory failure.3,5,9

- Efthimiou P, Paik PK, Bielory L. Diagnosis and management of adult onset Still's disease [published online October 11, 2005]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:564-572.

- Fautrel B. Adult-onset Still disease. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:773-792.

- Bagnari V, Colina M, Ciancio G, et al. Adult-onset Still's disease. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:855-862.

- Ravelli A, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2007;369:767-778.

- Yamaguchi M, Ohta A, Tsunematsu, T, et al. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still's disease. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:424-430.

- Van Reeth C, Le Moel G, Lasne Y, et al. Serum ferritin and isoferritins are tools for diagnosis of active adult Still's disease. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:890-895.

- Novak S, Anic F, Luke-Vrbanic TS. Extremely high serum ferritin levels as a main diagnostic tool of adult-onset Still's disease. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:1091-1094.

- Fortna RR, Gudjonsson JE, Seidel G, et al. Persistent pruritic papules and plaques: a characteristic histopathologic presentation seen in a subset of patients with adult-onset and juvenile Still's disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:932-937.

- Yang CC, Lee JY, Liu MF, et al. Adult-onset Still's disease with persistent skin eruption and fatal respiratory failure in a Taiwanese woman. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:593-594.

- Lee JY, Yang CC, Hsu MM. Histopathology of persistent papules and plaques in adult-onset Still's disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1003-1008.

- Kontzias A, Efthimiou P. The use of canakinumab, a novel IL-1β long-acting inhibitor in refractory adult-onset Still's disease. Sem Arthritis Rheum. 2012;42:201-205.

The Diagnosis: Persistent Still Disease

At the time of presentation, the patient had not taken systemic medications for a year. Laboratory studies revealed leukocytosis with neutrophilia and a serum ferritin level of 5493 ng/mL (reference range, 15-200 ng/mL). Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody serologies were within reference range. Microbiologic workup was negative. Lymph node and bone marrow biopsies were negative for a lymphoproliferative disorder. Skin biopsies were performed on the back and forearm. Histologic evaluation revealed orthokeratosis, slight acanthosis, and dyskeratosis confined to the upper layers of the epidermis without evidence of interface dermatitis. There was a mixed perivascular infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and neutrophils with no attendant vasculitic change (Figure).

The patient was discharged on prednisone and seen for outpatient follow-up weeks later. Six weeks later, the cutaneous eruption remained unchanged. The patient was unable to start other systemic medications due to lack of insurance and ineligibility for the local patient-assistance program; he was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Adult-onset Still disease is a rare, systemic, inflammatory condition with a broad spectrum of clinical presentations.1-3 Still disease affects all age groups, and children with Still disease (<16 years) usually have a concurrent diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (formerly known as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis).1,2,4 Still disease preferentially affects adolescents and adults aged 16 to 35 years, with more than 75% of new cases occurring in this age range.1 Worldwide, the incidence and prevalence of Still disease is disputed with no conclusive rates established.1,3

Still disease is characterized by 4 cardinal signs: high spiking fevers (temperature, ≥39°C); leukocytosis with a predominance of neutrophils (≥10,000 cells/mm3 with ≥80% neutrophils); arthralgia or arthritis; and an evanescent, nonpruritic, salmon-colored morbilliform eruption of the skin, typically on the trunk or extremities.2 Histologic evaluation of the classic Still disease eruption displays perivascular inflammation of the superficial dermis with infiltration by lymphocytes and histiocytes.3

In 1992, major and minor diagnostic criteria were established for adult-onset Still disease. For diagnosis, patients must meet 5 criteria, including 2 major criteria.5 Major criteria include arthralgia or arthritis present for more than 2 weeks, fever (temperature, >39°C) for at least 1 week, the classic Still disease morbilliform eruption (ie, salmon colored, evanescent, morbilliform), and leukocytosis with more than 80% neutrophils. Minor criteria include sore throat, lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly, negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody serologies, and abnormal liver function (defined as elevated transaminases).5 Although not included in the diagnostic criteria, there have been reports of elevated serum ferritin levels in patients with Still disease, a finding that potentially is useful in distinguishing between active and inactive rheumatic conditions.6,7

Several case reports have described persistent Still disease, a subtype of Still disease in which patients present with brown-red, persistent, pruritic macules, papules, and plaques that are widespread and oddly shaped.8,9 Histologically, this subtype is characterized by necrotic keratinocytes in the epidermis and dermal perivascular inflammation composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes.10 This histology differs from classic Still disease in that the latter typically does not have superficial epidermal dyskeratosis. Our case is consistent with reports of persistent Still disease.

Although the etiology of Still disease remains to be elucidated, HLA-B17, -B18, -B35, and -DR2 have been associated with the disease.3 Furthermore, helper T cell TH1, IL-2, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor α have been implicated in disease pathology, enabling the use of newer targeted pharmacologic therapies. Canakinumab, an IL-1β inhibitor, has been found to improve arthritis, fever, and rash in patients with Still disease.11 These findings are particularly encouraging for patients who have not experienced improvement with traditional antirheumatic drugs, such as our patient who was not steroid responsive.3

Although a salmon-colored, evanescent, morbilliform eruption in the context of other systemic signs and symptoms readily evokes consideration of Still disease, the less common fixed cutaneous eruption seen in our case may evade accurate diagnosis. Our case aims to increase awareness of this unusual and rare subtype of the cutaneous eruption of Still disease, as a timely diagnosis may prevent potentially life-threatening sequelae including cardiopulmonary disease and respiratory failure.3,5,9

The Diagnosis: Persistent Still Disease

At the time of presentation, the patient had not taken systemic medications for a year. Laboratory studies revealed leukocytosis with neutrophilia and a serum ferritin level of 5493 ng/mL (reference range, 15-200 ng/mL). Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody serologies were within reference range. Microbiologic workup was negative. Lymph node and bone marrow biopsies were negative for a lymphoproliferative disorder. Skin biopsies were performed on the back and forearm. Histologic evaluation revealed orthokeratosis, slight acanthosis, and dyskeratosis confined to the upper layers of the epidermis without evidence of interface dermatitis. There was a mixed perivascular infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and neutrophils with no attendant vasculitic change (Figure).

The patient was discharged on prednisone and seen for outpatient follow-up weeks later. Six weeks later, the cutaneous eruption remained unchanged. The patient was unable to start other systemic medications due to lack of insurance and ineligibility for the local patient-assistance program; he was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Adult-onset Still disease is a rare, systemic, inflammatory condition with a broad spectrum of clinical presentations.1-3 Still disease affects all age groups, and children with Still disease (<16 years) usually have a concurrent diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (formerly known as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis).1,2,4 Still disease preferentially affects adolescents and adults aged 16 to 35 years, with more than 75% of new cases occurring in this age range.1 Worldwide, the incidence and prevalence of Still disease is disputed with no conclusive rates established.1,3

Still disease is characterized by 4 cardinal signs: high spiking fevers (temperature, ≥39°C); leukocytosis with a predominance of neutrophils (≥10,000 cells/mm3 with ≥80% neutrophils); arthralgia or arthritis; and an evanescent, nonpruritic, salmon-colored morbilliform eruption of the skin, typically on the trunk or extremities.2 Histologic evaluation of the classic Still disease eruption displays perivascular inflammation of the superficial dermis with infiltration by lymphocytes and histiocytes.3

In 1992, major and minor diagnostic criteria were established for adult-onset Still disease. For diagnosis, patients must meet 5 criteria, including 2 major criteria.5 Major criteria include arthralgia or arthritis present for more than 2 weeks, fever (temperature, >39°C) for at least 1 week, the classic Still disease morbilliform eruption (ie, salmon colored, evanescent, morbilliform), and leukocytosis with more than 80% neutrophils. Minor criteria include sore throat, lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly, negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody serologies, and abnormal liver function (defined as elevated transaminases).5 Although not included in the diagnostic criteria, there have been reports of elevated serum ferritin levels in patients with Still disease, a finding that potentially is useful in distinguishing between active and inactive rheumatic conditions.6,7