User login

To the Editor:

A fixed drug eruption (FDE) is a well-documented form of cutaneous hypersensitivity that typically manifests as a sharply demarcated, dusky, round to oval, edematous, red-violaceous macule or patch on the skin and mucous membranes. The lesion often resolves with residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, most commonly as a reaction to ingested drugs or drug components.1 Lesions generally occur at the same anatomic site with repeated exposure to the offending drug. Typically, a single site is affected, but additional sites with more generalized involvement have been reported to occur with subsequent exposure to the offending medication. The diagnosis usually is clinical, but histopathologic findings can help confirm the diagnosis in unusual presentations. We present a novel case of a patient with an FDE from medroxyprogesterone acetate, a contraceptive injection that contains the hormone progestin.

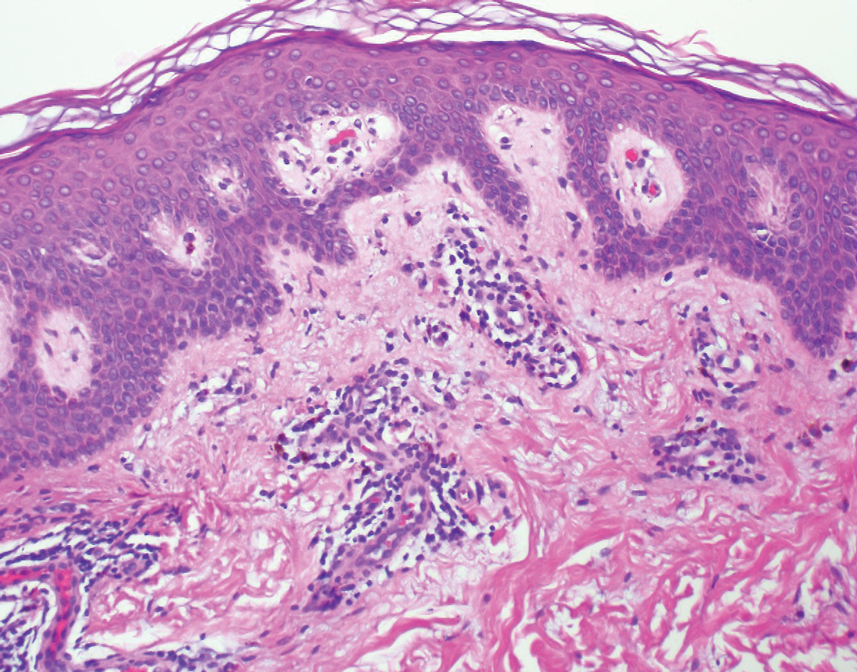

A 35-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a lesion on the left lower buttock of 1 year’s duration. She reported periodic swelling and associated pruritus of the lesion. She denied any growth in size, and no other similar lesions were present. The patient reported a medication history of medroxyprogesterone acetate for birth control, but she denied any other prescription or over-the-counter medication, oral supplements, or recreational drug use. Upon further inquiry, she reported that the recurrence of symptoms appeared to coincide with each administration of medroxyprogesterone acetate, which occurred approximately every 3 months. The eruption cleared between injections and recurred in the same location following subsequent injections. The lesion appeared approximately 2 weeks after the first injection (approximately 1 year prior to presentation to dermatology) and within 2 to 3 days after each subsequent injection. Physical examination revealed a 2×2-cm, circular, slightly violaceous patch on the left buttock (Figure 1). A biopsy was recommended to aid in diagnosis, and the patient was offered a topical steroid for symptomatic relief. A punch biopsy revealed subtle interface dermatitis with superficial perivascular lymphoid infiltrate and marked pigmentary incontinence consistent with an FDE (Figure 2).

An FDE was first reported in 1889 by Bourns,2 and over time more implicated agents and varying clinical presentations have been linked to the disease. The FDE can be accompanied by symptoms of pruritus or paresthesia. Most cases are devoid of systemic symptoms. An FDE can be located anywhere on the body, but it most frequently manifests on the lips, face, hands, feet, and genitalia. Although the eruption often heals with residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, a nonpigmenting FDE due to pseudoephedrine has been reported.3

Common culprits include antibiotics (eg, sulfonamides, trimethoprim, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (eg, naproxen sodium, ibuprofen, celecoxib), barbiturates, antimalarials, and anticonvulsants. Rare cases of FDE induced by foods and food additives also have been reported.4 Oral fluconazole, levocetirizine dihydrochloride, loperamide, and multivitamin-mineral preparations are other rare inducers of FDE.5-8 In 2004, Ritter and Meffert9 described an FDE to the green dye used in inactive oral contraceptive pills. A similar case was reported by Rea et al10 that described an FDE from the inactive sugar pills in ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel, which is another combined oral contraceptive.

The time between ingestion of the offending agent and the manifestation of the disease usually is 1 to 2 weeks; however, upon subsequent exposure, the disease has been reported to manifest within hours.1 CD8+ memory T cells have been shown to be major players in the development of FDE and can be found along the dermoepidermal junction as part of a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction.11 Histopathology reveals superficial and deep interstitial and perivascular infiltrates consisting of lymphocytes with admixed eosinophils and possibly neutrophils in the dermis. In the epidermis, necrotic keratinocytes can be present. In rare cases, FDE may have atypical features, such as in generalized bullous FDE and nonpigmenting FDE, the latter of which more commonly is associated with pseudoephedrine.1

The differential diagnosis for FDE includes erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, autoimmune progesterone dermatitis, and large plaque parapsoriasis. The number and morphology of lesions in erythema multiforme help differentiate it from FDE, as erythema multiforme presents with multiple targetoid lesions. The lesions of generalized bullous FDE can be similar to those of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, and the pigmented patches of FDE can resemble large plaque parapsoriasis.

It is important to consider any medication ingested in the 1- to 2-week period before FDE onset, including over-the-counter medications, health food supplements, and prescription medications. Discontinuation of the implicated medication or any medication potentially cross-reacting with another medication is the most important step in management. Wound care may be needed for any bullous or eroded lesions. Lesions typically resolve within a few days to weeks of stopping the offending agent. Importantly, patients should be counseled on the secondary pigment alterations that may be persistent for several months. Other treatment for FDEs is aimed at symptomatic relief and may include topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines.1

Medroxyprogesterone acetate is a highly effective contraceptive drug with low rates of failure.12 It is a weak androgenic progestin that is administered as a single 150-mg intramuscular injection every 3 months and inhibits gonadotropins. Common side effects include local injection-site reactions, unscheduled bleeding, amenorrhea, weight gain, headache, and mood changes. However, FDE has not been reported as an adverse effect to medroxyprogesterone acetate, both in official US Food and Drug Administration information and in the current literature.12

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (also known as progestin hypersensitivity) is a well-characterized cyclic hypersensitivity reaction to the hormone progesterone that occurs during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. It is known to have a variable clinical presentation including urticaria, erythema multiforme, eczema, and angioedema.13 Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis also has been reported to present as an FDE.14-16 The onset of the cutaneous manifestation often starts a few days before the onset of menses, with spontaneous resolution occurring after the onset of menstruation. The mechanism by which endogenous progesterone or other secretory products become antigenic is unknown. It has been suggested that there is an alteration in the properties of the hormone that would predispose it to be antigenic as it would not be considered self. In 2001, Warin17 proposed the following diagnostic criteria for autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: (1) skin lesions associated with menstrual cycle (premenstrual flare); (2) a positive response to the progesterone intradermal or intramuscular test; and (3) symptomatic improvement after inhibiting progesterone secretion by suppressing ovulation.17 The treatment includes antiallergy medications, progesterone desensitization, omalizumab injection, and leuprolide acetate injection.

Our case represents FDE from medroxyprogesterone acetate. Although we did not formally investigate the antigenicity of the exogenous progesterone, we postulate that the pathophysiology likely is similar to an FDE associated with endogenous progesterone. This reasoning is supported by the time course of the patient’s lesion as well as the worsening of symptoms in the days following the administration of the medication. Additionally, the patient had no history of skin lesions prior to the initiation of medroxyprogesterone acetate or similar lesions associated with her menstrual cycles.

A careful and detailed review of medication history is necessary to evaluate FDEs. Our case emphasizes that not only endogenous but also exogenous forms of progesterone may cause hypersensitivity, leading to an FDE. With more than 2 million prescriptions of medroxyprogesterone acetate written every year, dermatologists should be aware of the rare but potential risk for an FDE in patients using this medication.18

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Mosby; 2008.

- Bourns DCG. Unusual effects of antipyrine. Br Med J. 1889;2:818-820.

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption as a distinctive reaction pattern: examples caused by sensitivity to pseudoephedrine hydrochloride and tetrahydrozoline. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:403-407.

- Sohn KH, Kim BK, Kim JY, et al. Fixed food eruption caused by Actinidia arguta (hardy kiwi): a case report and literature review. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2017;9:182-184.

- Nakai N, Katoh N. Fixed drug eruption caused by fluconazole: a case report and mini-review of the literature. Allergol Int. 2013;6:139-141.

- An I, Demir V, Ibiloglu I, et al. Fixed drug eruption induced by levocetirizine. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:276-278.

- Matarredona J, Borrás Blasco J, Navarro-Ruiz A, et al. Fixed drug eruption associated to loperamide [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc). 2005;124:198-199.

- Gohel D. Fixed drug eruption due to multi-vitamin multi-mineral preparation. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48:268.

- Ritter SE, Meffert J. A refractory fixed drug reaction to a dye used in an oral contraceptive. Cutis. 2004;74:243-244.

- Rea S, McMeniman E, Darch K, et al. A fixed drug eruption to the sugar pills of a combined oral contraceptive. Poster presented at: The Australasian College of Dermatologists 51st Annual Scientific Meeting; May 22, 2018; Queensland, Australia.

- Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y. Fixed drug eruption: a disease mediated by self-inflicted responses of intraepidermal T cells. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:201-208.

- Depo-Provera CI. Prescribing information. Pfizer; 2020. Accessed March 10, 2022. https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?format=PDF&id=522

- George R, Badawy SZ. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:757854.

- Mokhtari R, Sepaskhah M, Aslani FS, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt685685p4.

- Asai J, Katoh N, Nakano M, et al. Case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption. J Dermatol. 2009;36:643-645.

- Bhardwaj N, Jindal R, Chauhan P. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:E231873.

- Warin AP. Case 2. diagnosis: erythema multiforme as a presentation of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:107-108.

- Medroxyprogesterone Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013-2019. ClinCalc website. Updated September 15, 2021. Accessed March 17, 2022. https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Medroxyprogesterone

To the Editor:

A fixed drug eruption (FDE) is a well-documented form of cutaneous hypersensitivity that typically manifests as a sharply demarcated, dusky, round to oval, edematous, red-violaceous macule or patch on the skin and mucous membranes. The lesion often resolves with residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, most commonly as a reaction to ingested drugs or drug components.1 Lesions generally occur at the same anatomic site with repeated exposure to the offending drug. Typically, a single site is affected, but additional sites with more generalized involvement have been reported to occur with subsequent exposure to the offending medication. The diagnosis usually is clinical, but histopathologic findings can help confirm the diagnosis in unusual presentations. We present a novel case of a patient with an FDE from medroxyprogesterone acetate, a contraceptive injection that contains the hormone progestin.

A 35-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a lesion on the left lower buttock of 1 year’s duration. She reported periodic swelling and associated pruritus of the lesion. She denied any growth in size, and no other similar lesions were present. The patient reported a medication history of medroxyprogesterone acetate for birth control, but she denied any other prescription or over-the-counter medication, oral supplements, or recreational drug use. Upon further inquiry, she reported that the recurrence of symptoms appeared to coincide with each administration of medroxyprogesterone acetate, which occurred approximately every 3 months. The eruption cleared between injections and recurred in the same location following subsequent injections. The lesion appeared approximately 2 weeks after the first injection (approximately 1 year prior to presentation to dermatology) and within 2 to 3 days after each subsequent injection. Physical examination revealed a 2×2-cm, circular, slightly violaceous patch on the left buttock (Figure 1). A biopsy was recommended to aid in diagnosis, and the patient was offered a topical steroid for symptomatic relief. A punch biopsy revealed subtle interface dermatitis with superficial perivascular lymphoid infiltrate and marked pigmentary incontinence consistent with an FDE (Figure 2).

An FDE was first reported in 1889 by Bourns,2 and over time more implicated agents and varying clinical presentations have been linked to the disease. The FDE can be accompanied by symptoms of pruritus or paresthesia. Most cases are devoid of systemic symptoms. An FDE can be located anywhere on the body, but it most frequently manifests on the lips, face, hands, feet, and genitalia. Although the eruption often heals with residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, a nonpigmenting FDE due to pseudoephedrine has been reported.3

Common culprits include antibiotics (eg, sulfonamides, trimethoprim, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (eg, naproxen sodium, ibuprofen, celecoxib), barbiturates, antimalarials, and anticonvulsants. Rare cases of FDE induced by foods and food additives also have been reported.4 Oral fluconazole, levocetirizine dihydrochloride, loperamide, and multivitamin-mineral preparations are other rare inducers of FDE.5-8 In 2004, Ritter and Meffert9 described an FDE to the green dye used in inactive oral contraceptive pills. A similar case was reported by Rea et al10 that described an FDE from the inactive sugar pills in ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel, which is another combined oral contraceptive.

The time between ingestion of the offending agent and the manifestation of the disease usually is 1 to 2 weeks; however, upon subsequent exposure, the disease has been reported to manifest within hours.1 CD8+ memory T cells have been shown to be major players in the development of FDE and can be found along the dermoepidermal junction as part of a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction.11 Histopathology reveals superficial and deep interstitial and perivascular infiltrates consisting of lymphocytes with admixed eosinophils and possibly neutrophils in the dermis. In the epidermis, necrotic keratinocytes can be present. In rare cases, FDE may have atypical features, such as in generalized bullous FDE and nonpigmenting FDE, the latter of which more commonly is associated with pseudoephedrine.1

The differential diagnosis for FDE includes erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, autoimmune progesterone dermatitis, and large plaque parapsoriasis. The number and morphology of lesions in erythema multiforme help differentiate it from FDE, as erythema multiforme presents with multiple targetoid lesions. The lesions of generalized bullous FDE can be similar to those of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, and the pigmented patches of FDE can resemble large plaque parapsoriasis.

It is important to consider any medication ingested in the 1- to 2-week period before FDE onset, including over-the-counter medications, health food supplements, and prescription medications. Discontinuation of the implicated medication or any medication potentially cross-reacting with another medication is the most important step in management. Wound care may be needed for any bullous or eroded lesions. Lesions typically resolve within a few days to weeks of stopping the offending agent. Importantly, patients should be counseled on the secondary pigment alterations that may be persistent for several months. Other treatment for FDEs is aimed at symptomatic relief and may include topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines.1

Medroxyprogesterone acetate is a highly effective contraceptive drug with low rates of failure.12 It is a weak androgenic progestin that is administered as a single 150-mg intramuscular injection every 3 months and inhibits gonadotropins. Common side effects include local injection-site reactions, unscheduled bleeding, amenorrhea, weight gain, headache, and mood changes. However, FDE has not been reported as an adverse effect to medroxyprogesterone acetate, both in official US Food and Drug Administration information and in the current literature.12

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (also known as progestin hypersensitivity) is a well-characterized cyclic hypersensitivity reaction to the hormone progesterone that occurs during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. It is known to have a variable clinical presentation including urticaria, erythema multiforme, eczema, and angioedema.13 Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis also has been reported to present as an FDE.14-16 The onset of the cutaneous manifestation often starts a few days before the onset of menses, with spontaneous resolution occurring after the onset of menstruation. The mechanism by which endogenous progesterone or other secretory products become antigenic is unknown. It has been suggested that there is an alteration in the properties of the hormone that would predispose it to be antigenic as it would not be considered self. In 2001, Warin17 proposed the following diagnostic criteria for autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: (1) skin lesions associated with menstrual cycle (premenstrual flare); (2) a positive response to the progesterone intradermal or intramuscular test; and (3) symptomatic improvement after inhibiting progesterone secretion by suppressing ovulation.17 The treatment includes antiallergy medications, progesterone desensitization, omalizumab injection, and leuprolide acetate injection.

Our case represents FDE from medroxyprogesterone acetate. Although we did not formally investigate the antigenicity of the exogenous progesterone, we postulate that the pathophysiology likely is similar to an FDE associated with endogenous progesterone. This reasoning is supported by the time course of the patient’s lesion as well as the worsening of symptoms in the days following the administration of the medication. Additionally, the patient had no history of skin lesions prior to the initiation of medroxyprogesterone acetate or similar lesions associated with her menstrual cycles.

A careful and detailed review of medication history is necessary to evaluate FDEs. Our case emphasizes that not only endogenous but also exogenous forms of progesterone may cause hypersensitivity, leading to an FDE. With more than 2 million prescriptions of medroxyprogesterone acetate written every year, dermatologists should be aware of the rare but potential risk for an FDE in patients using this medication.18

To the Editor:

A fixed drug eruption (FDE) is a well-documented form of cutaneous hypersensitivity that typically manifests as a sharply demarcated, dusky, round to oval, edematous, red-violaceous macule or patch on the skin and mucous membranes. The lesion often resolves with residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, most commonly as a reaction to ingested drugs or drug components.1 Lesions generally occur at the same anatomic site with repeated exposure to the offending drug. Typically, a single site is affected, but additional sites with more generalized involvement have been reported to occur with subsequent exposure to the offending medication. The diagnosis usually is clinical, but histopathologic findings can help confirm the diagnosis in unusual presentations. We present a novel case of a patient with an FDE from medroxyprogesterone acetate, a contraceptive injection that contains the hormone progestin.

A 35-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a lesion on the left lower buttock of 1 year’s duration. She reported periodic swelling and associated pruritus of the lesion. She denied any growth in size, and no other similar lesions were present. The patient reported a medication history of medroxyprogesterone acetate for birth control, but she denied any other prescription or over-the-counter medication, oral supplements, or recreational drug use. Upon further inquiry, she reported that the recurrence of symptoms appeared to coincide with each administration of medroxyprogesterone acetate, which occurred approximately every 3 months. The eruption cleared between injections and recurred in the same location following subsequent injections. The lesion appeared approximately 2 weeks after the first injection (approximately 1 year prior to presentation to dermatology) and within 2 to 3 days after each subsequent injection. Physical examination revealed a 2×2-cm, circular, slightly violaceous patch on the left buttock (Figure 1). A biopsy was recommended to aid in diagnosis, and the patient was offered a topical steroid for symptomatic relief. A punch biopsy revealed subtle interface dermatitis with superficial perivascular lymphoid infiltrate and marked pigmentary incontinence consistent with an FDE (Figure 2).

An FDE was first reported in 1889 by Bourns,2 and over time more implicated agents and varying clinical presentations have been linked to the disease. The FDE can be accompanied by symptoms of pruritus or paresthesia. Most cases are devoid of systemic symptoms. An FDE can be located anywhere on the body, but it most frequently manifests on the lips, face, hands, feet, and genitalia. Although the eruption often heals with residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, a nonpigmenting FDE due to pseudoephedrine has been reported.3

Common culprits include antibiotics (eg, sulfonamides, trimethoprim, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (eg, naproxen sodium, ibuprofen, celecoxib), barbiturates, antimalarials, and anticonvulsants. Rare cases of FDE induced by foods and food additives also have been reported.4 Oral fluconazole, levocetirizine dihydrochloride, loperamide, and multivitamin-mineral preparations are other rare inducers of FDE.5-8 In 2004, Ritter and Meffert9 described an FDE to the green dye used in inactive oral contraceptive pills. A similar case was reported by Rea et al10 that described an FDE from the inactive sugar pills in ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel, which is another combined oral contraceptive.

The time between ingestion of the offending agent and the manifestation of the disease usually is 1 to 2 weeks; however, upon subsequent exposure, the disease has been reported to manifest within hours.1 CD8+ memory T cells have been shown to be major players in the development of FDE and can be found along the dermoepidermal junction as part of a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction.11 Histopathology reveals superficial and deep interstitial and perivascular infiltrates consisting of lymphocytes with admixed eosinophils and possibly neutrophils in the dermis. In the epidermis, necrotic keratinocytes can be present. In rare cases, FDE may have atypical features, such as in generalized bullous FDE and nonpigmenting FDE, the latter of which more commonly is associated with pseudoephedrine.1

The differential diagnosis for FDE includes erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, autoimmune progesterone dermatitis, and large plaque parapsoriasis. The number and morphology of lesions in erythema multiforme help differentiate it from FDE, as erythema multiforme presents with multiple targetoid lesions. The lesions of generalized bullous FDE can be similar to those of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, and the pigmented patches of FDE can resemble large plaque parapsoriasis.

It is important to consider any medication ingested in the 1- to 2-week period before FDE onset, including over-the-counter medications, health food supplements, and prescription medications. Discontinuation of the implicated medication or any medication potentially cross-reacting with another medication is the most important step in management. Wound care may be needed for any bullous or eroded lesions. Lesions typically resolve within a few days to weeks of stopping the offending agent. Importantly, patients should be counseled on the secondary pigment alterations that may be persistent for several months. Other treatment for FDEs is aimed at symptomatic relief and may include topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines.1

Medroxyprogesterone acetate is a highly effective contraceptive drug with low rates of failure.12 It is a weak androgenic progestin that is administered as a single 150-mg intramuscular injection every 3 months and inhibits gonadotropins. Common side effects include local injection-site reactions, unscheduled bleeding, amenorrhea, weight gain, headache, and mood changes. However, FDE has not been reported as an adverse effect to medroxyprogesterone acetate, both in official US Food and Drug Administration information and in the current literature.12

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (also known as progestin hypersensitivity) is a well-characterized cyclic hypersensitivity reaction to the hormone progesterone that occurs during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. It is known to have a variable clinical presentation including urticaria, erythema multiforme, eczema, and angioedema.13 Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis also has been reported to present as an FDE.14-16 The onset of the cutaneous manifestation often starts a few days before the onset of menses, with spontaneous resolution occurring after the onset of menstruation. The mechanism by which endogenous progesterone or other secretory products become antigenic is unknown. It has been suggested that there is an alteration in the properties of the hormone that would predispose it to be antigenic as it would not be considered self. In 2001, Warin17 proposed the following diagnostic criteria for autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: (1) skin lesions associated with menstrual cycle (premenstrual flare); (2) a positive response to the progesterone intradermal or intramuscular test; and (3) symptomatic improvement after inhibiting progesterone secretion by suppressing ovulation.17 The treatment includes antiallergy medications, progesterone desensitization, omalizumab injection, and leuprolide acetate injection.

Our case represents FDE from medroxyprogesterone acetate. Although we did not formally investigate the antigenicity of the exogenous progesterone, we postulate that the pathophysiology likely is similar to an FDE associated with endogenous progesterone. This reasoning is supported by the time course of the patient’s lesion as well as the worsening of symptoms in the days following the administration of the medication. Additionally, the patient had no history of skin lesions prior to the initiation of medroxyprogesterone acetate or similar lesions associated with her menstrual cycles.

A careful and detailed review of medication history is necessary to evaluate FDEs. Our case emphasizes that not only endogenous but also exogenous forms of progesterone may cause hypersensitivity, leading to an FDE. With more than 2 million prescriptions of medroxyprogesterone acetate written every year, dermatologists should be aware of the rare but potential risk for an FDE in patients using this medication.18

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Mosby; 2008.

- Bourns DCG. Unusual effects of antipyrine. Br Med J. 1889;2:818-820.

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption as a distinctive reaction pattern: examples caused by sensitivity to pseudoephedrine hydrochloride and tetrahydrozoline. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:403-407.

- Sohn KH, Kim BK, Kim JY, et al. Fixed food eruption caused by Actinidia arguta (hardy kiwi): a case report and literature review. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2017;9:182-184.

- Nakai N, Katoh N. Fixed drug eruption caused by fluconazole: a case report and mini-review of the literature. Allergol Int. 2013;6:139-141.

- An I, Demir V, Ibiloglu I, et al. Fixed drug eruption induced by levocetirizine. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:276-278.

- Matarredona J, Borrás Blasco J, Navarro-Ruiz A, et al. Fixed drug eruption associated to loperamide [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc). 2005;124:198-199.

- Gohel D. Fixed drug eruption due to multi-vitamin multi-mineral preparation. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48:268.

- Ritter SE, Meffert J. A refractory fixed drug reaction to a dye used in an oral contraceptive. Cutis. 2004;74:243-244.

- Rea S, McMeniman E, Darch K, et al. A fixed drug eruption to the sugar pills of a combined oral contraceptive. Poster presented at: The Australasian College of Dermatologists 51st Annual Scientific Meeting; May 22, 2018; Queensland, Australia.

- Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y. Fixed drug eruption: a disease mediated by self-inflicted responses of intraepidermal T cells. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:201-208.

- Depo-Provera CI. Prescribing information. Pfizer; 2020. Accessed March 10, 2022. https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?format=PDF&id=522

- George R, Badawy SZ. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:757854.

- Mokhtari R, Sepaskhah M, Aslani FS, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt685685p4.

- Asai J, Katoh N, Nakano M, et al. Case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption. J Dermatol. 2009;36:643-645.

- Bhardwaj N, Jindal R, Chauhan P. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:E231873.

- Warin AP. Case 2. diagnosis: erythema multiforme as a presentation of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:107-108.

- Medroxyprogesterone Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013-2019. ClinCalc website. Updated September 15, 2021. Accessed March 17, 2022. https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Medroxyprogesterone

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Mosby; 2008.

- Bourns DCG. Unusual effects of antipyrine. Br Med J. 1889;2:818-820.

- Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption as a distinctive reaction pattern: examples caused by sensitivity to pseudoephedrine hydrochloride and tetrahydrozoline. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:403-407.

- Sohn KH, Kim BK, Kim JY, et al. Fixed food eruption caused by Actinidia arguta (hardy kiwi): a case report and literature review. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2017;9:182-184.

- Nakai N, Katoh N. Fixed drug eruption caused by fluconazole: a case report and mini-review of the literature. Allergol Int. 2013;6:139-141.

- An I, Demir V, Ibiloglu I, et al. Fixed drug eruption induced by levocetirizine. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:276-278.

- Matarredona J, Borrás Blasco J, Navarro-Ruiz A, et al. Fixed drug eruption associated to loperamide [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc). 2005;124:198-199.

- Gohel D. Fixed drug eruption due to multi-vitamin multi-mineral preparation. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48:268.

- Ritter SE, Meffert J. A refractory fixed drug reaction to a dye used in an oral contraceptive. Cutis. 2004;74:243-244.

- Rea S, McMeniman E, Darch K, et al. A fixed drug eruption to the sugar pills of a combined oral contraceptive. Poster presented at: The Australasian College of Dermatologists 51st Annual Scientific Meeting; May 22, 2018; Queensland, Australia.

- Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y. Fixed drug eruption: a disease mediated by self-inflicted responses of intraepidermal T cells. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:201-208.

- Depo-Provera CI. Prescribing information. Pfizer; 2020. Accessed March 10, 2022. https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?format=PDF&id=522

- George R, Badawy SZ. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:757854.

- Mokhtari R, Sepaskhah M, Aslani FS, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt685685p4.

- Asai J, Katoh N, Nakano M, et al. Case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption. J Dermatol. 2009;36:643-645.

- Bhardwaj N, Jindal R, Chauhan P. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:E231873.

- Warin AP. Case 2. diagnosis: erythema multiforme as a presentation of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:107-108.

- Medroxyprogesterone Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013-2019. ClinCalc website. Updated September 15, 2021. Accessed March 17, 2022. https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Medroxyprogesterone

Practice Points

- Exogenous progesterone from the administration of the contraceptive injectable medroxyprogesterone acetate has the potential to cause a cutaneous hypersensitivity reaction in the form of a fixed drug eruption (FDE).

- Dermatologists should perform a careful and detailed review of medication history to evaluate drug eruptions.