User login

Solitary Pink Plaque on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Plaque-type Syringoma

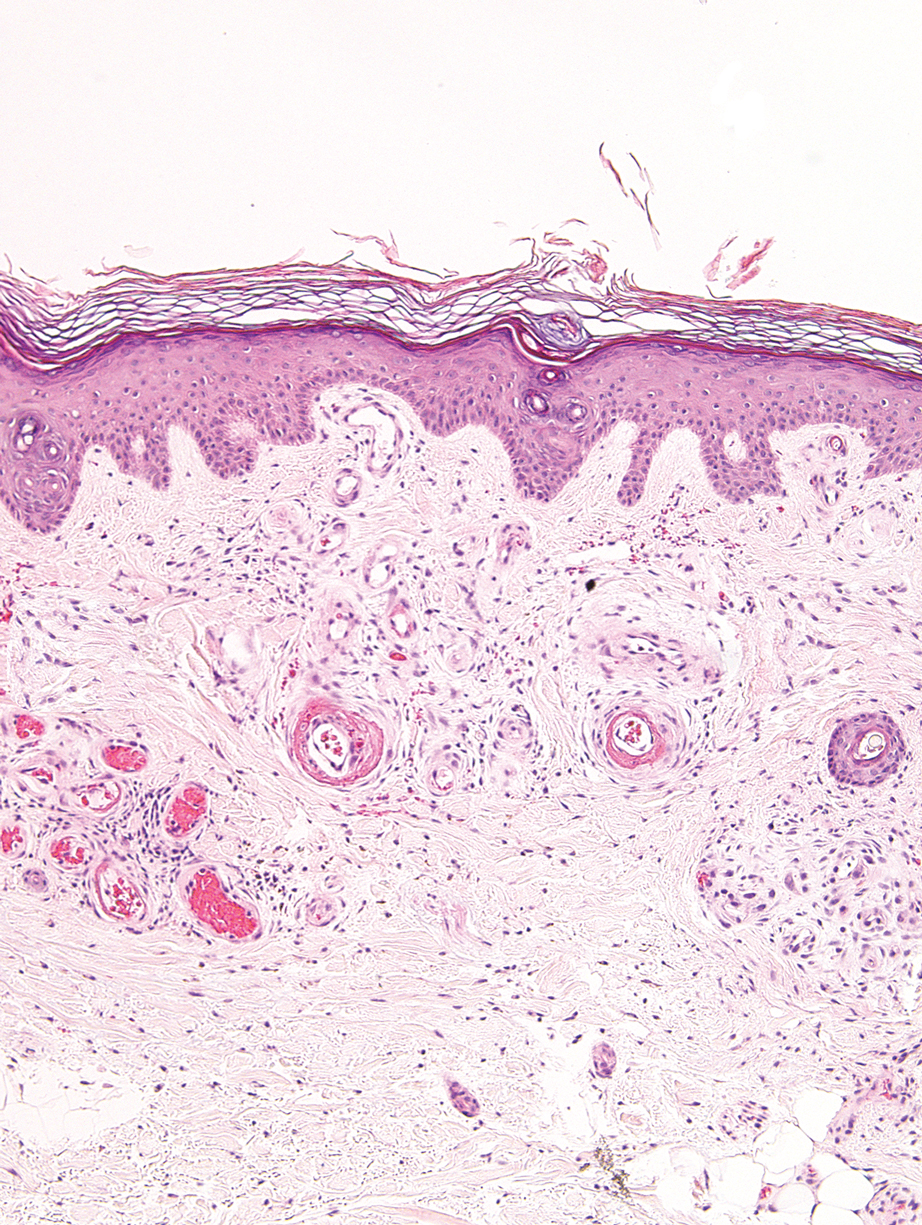

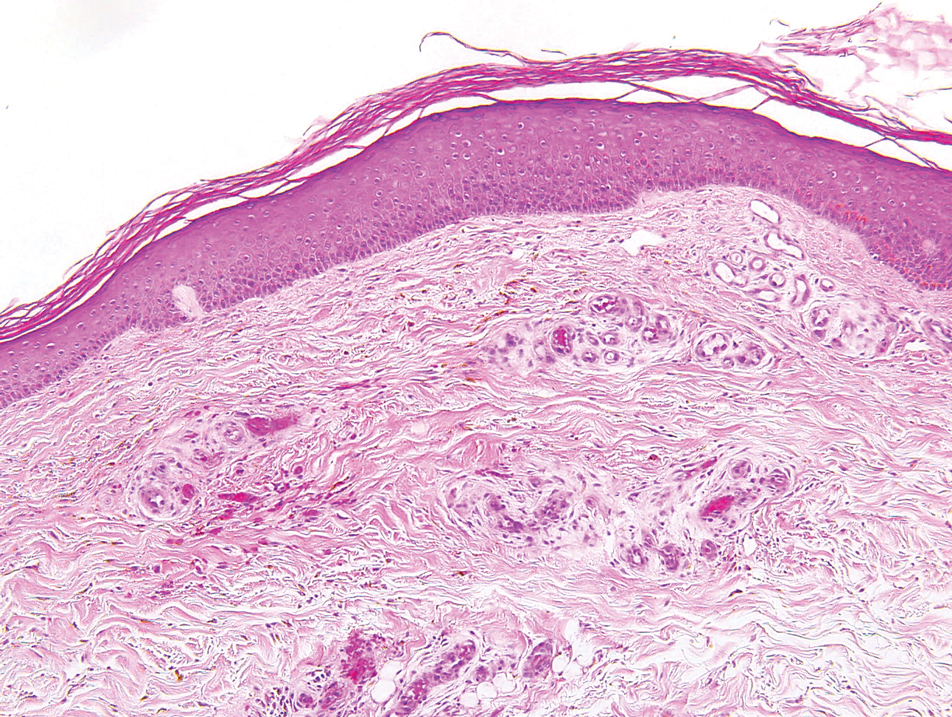

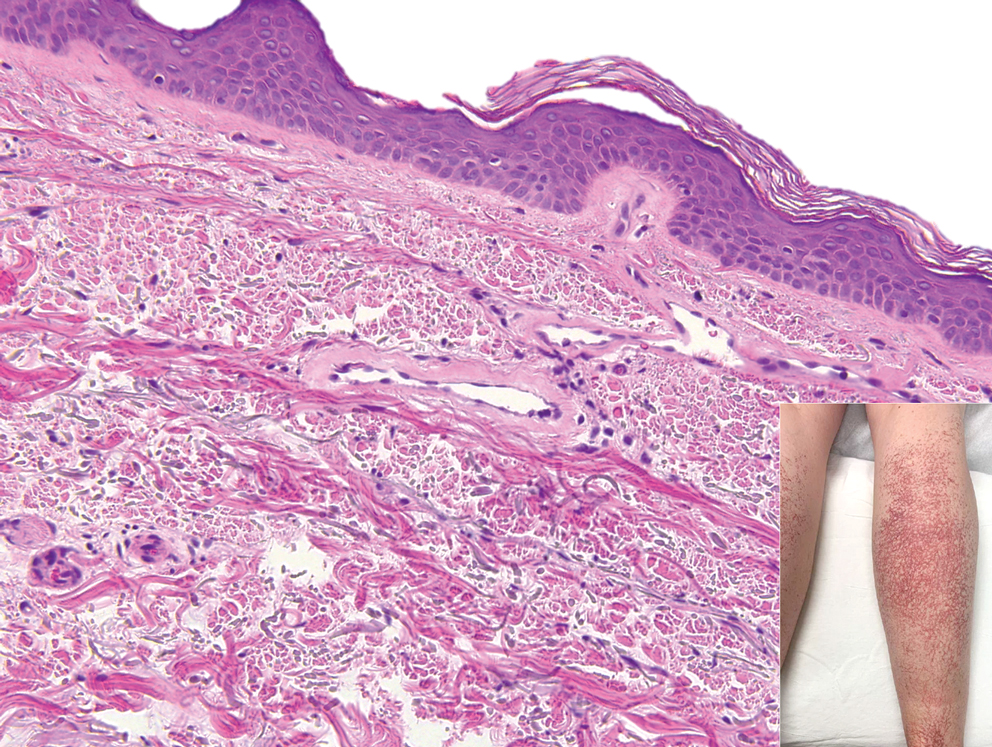

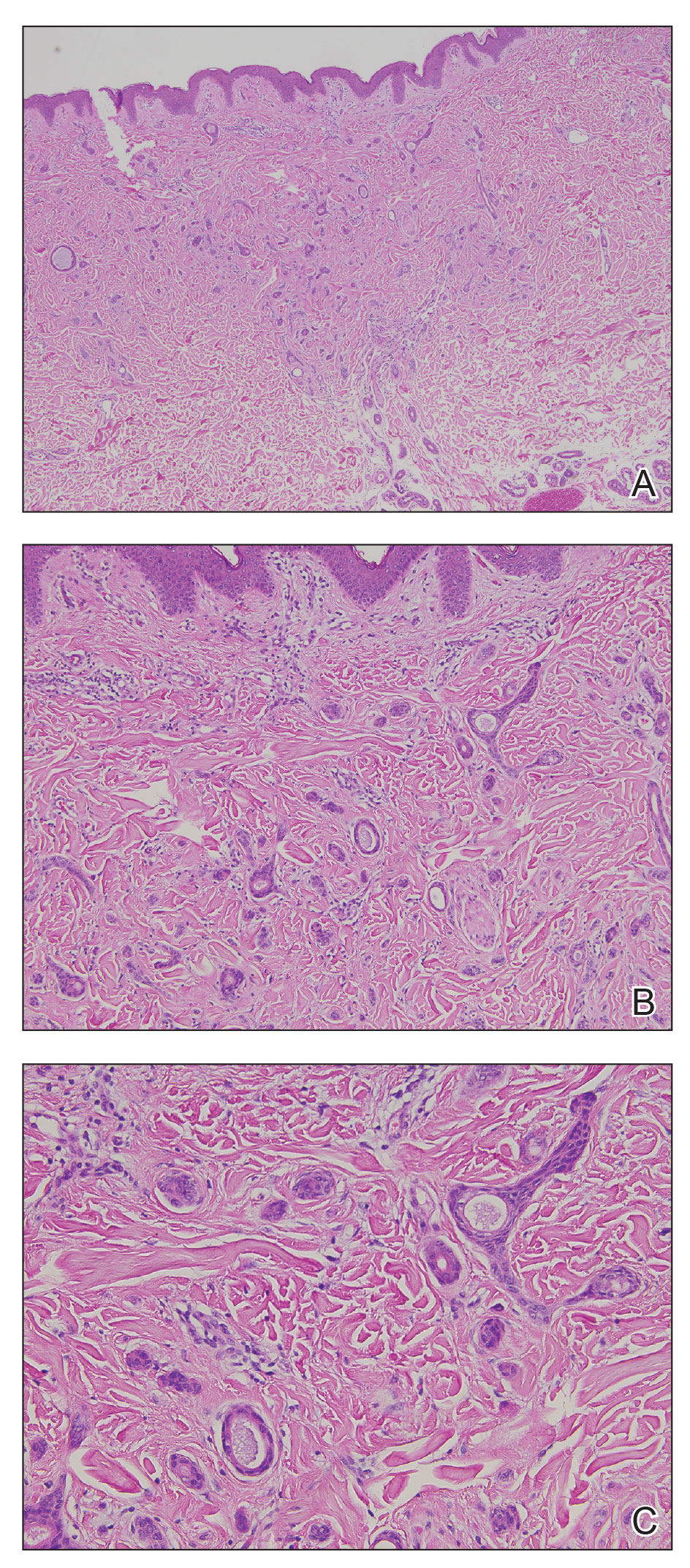

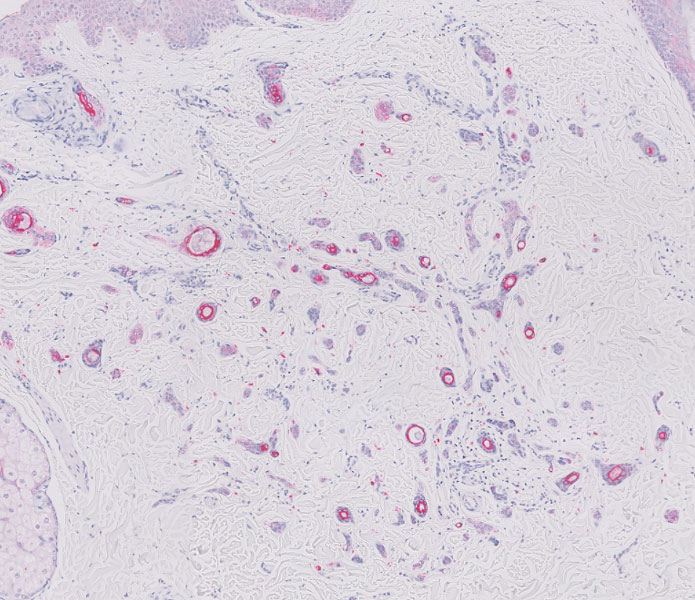

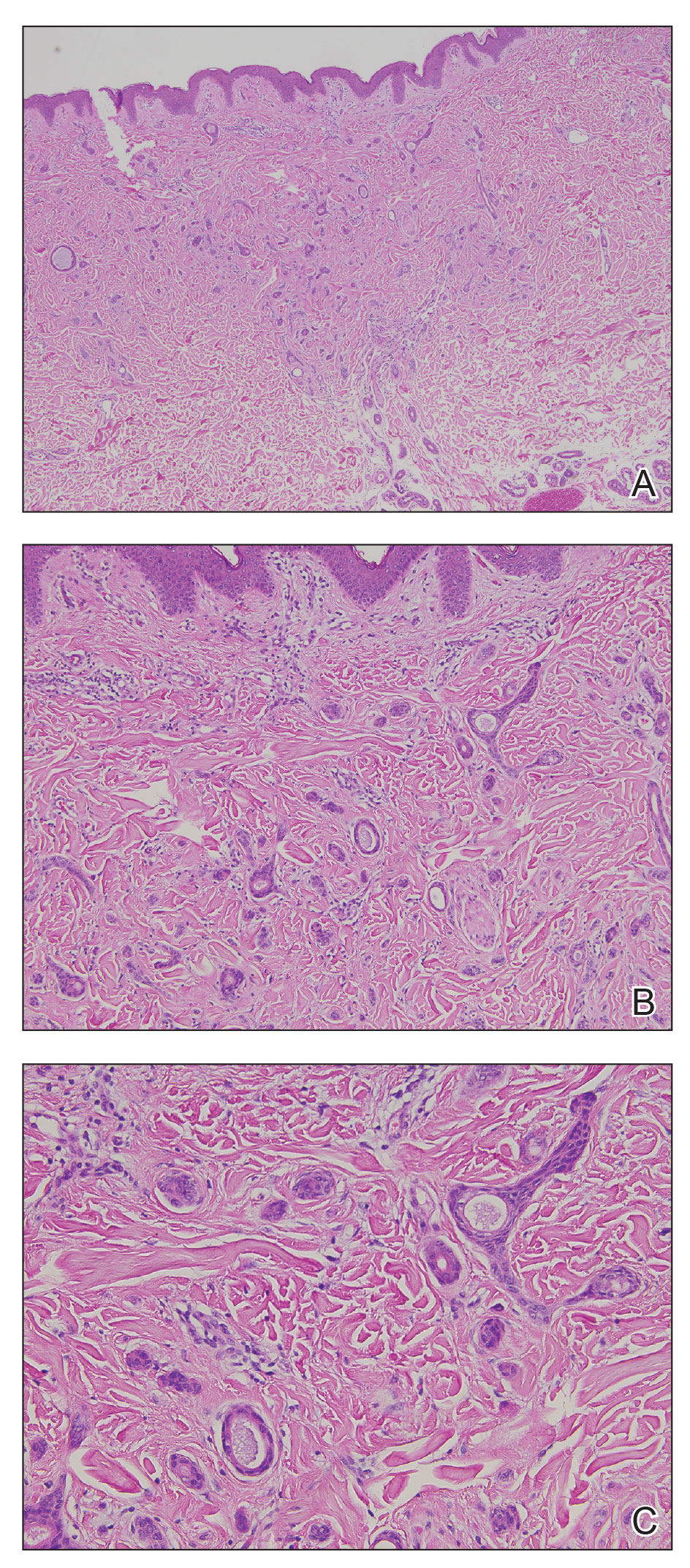

A biopsy demonstrated multiple basaloid islands of tumor cells in the reticular dermis with ductal differentiation, some with a commalike tail. The ducts were lined by 2 to 3 layers of small uniform cuboidal cells without atypia and contained inspissated secretions within the lumina of scattered ducts. There was an associated fibrotic collagenous stroma. There was no evidence of perineural invasion and no deep dermal or subcutaneous extension (Figure 1). Additional cytokeratin immunohistochemical staining highlighted the adnexal proliferation (Figure 2). A diagnosis of plaque-type syringoma (PTS) was made.

Syringomas are benign dermal sweat gland tumors that typically present as flesh-colored papules on the cheeks or periorbital area of young females. Plaque-type tumors as well as papulonodular, eruptive, disseminated, urticaria pigmentosa–like, lichen planus–like, or milialike syringomas also have been reported. Syringomas may be associated with certain medical conditions such as Down syndrome, Nicolau-Balus syndrome, and both scarring and nonscarring alopecias.1 The clear cell variant of syringoma often is associated with diabetes mellitus.2 Kikuchi et al3 first described PTS in 1979. Plaque-type syringomas rarely are reported in the literature, and sites of involvement include the head and neck region, upper lip, chest, upper extremities, vulva, penis, and scrotum.4-6

Histologically, syringomatous lesions are composed of multiple small ducts lined by 2 to 3 layers of cuboidal epithelium. The ducts may be arranged in nests or strands of basaloid cells surrounded by a dense fibrotic stroma. Occasionally, the ducts will form a comma- or teardropshaped tail; however, this also may be observed in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma (DTE).7 Perineural invasion is absent in syringomas. Syringomas exhibit a lateral growth pattern that typically is limited to the upper half of the reticular dermis and spares the underlying subcutis, muscle, and bone. The growth pattern may be discontinuous with proliferations juxtaposed by normal-appearing skin.8 Syringomas usually express progesterone receptors and are known to proliferate at puberty, suggesting that these neoplasms are under hormonal control.9 Although syringomas are benign, various treatment options that may be pursued for cosmetic purposes include radiofrequency, staged excision, laser ablation, and oral isotretinoin.8,10 If only a superficial biopsy is obtained, syringomas may display features of other adnexal neoplasms, including microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), DTE, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN).

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is a locally aggressive neoplasm first described by Goldstein et al11 in 1982 an indurated, ill-defined plaque or nodule on the face with a predilection for the upper and lower lip. Prior radiation therapy and immunosuppression are risk factors for the development of MAC.12 Histologically, the superficial portion displays small cornifying cysts interspersed with islands of basaloid cells and may mimic a syringoma. However, the deeper portions demonstrate ducts lined by a single layer of cells with a background of hyalinized and sclerotic stroma. The tumor cells may occupy the deep dermis and underlying subcutis, muscle, or bone and demonstrate an infiltrative growth pattern and perineural invasion. Treatment includes Mohs micrographic surgery.

Desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas most commonly present as solitary white to yellowish annular papules or plaques with a central dell located on sun-exposed areas of the face, cheeks, or chin. This benign neoplasm has a bimodal age distribution, primarily affecting females either in childhood or adulthood.13 Histologically, strands and nests of basaloid epithelial cells proliferate in a dense eosinophilic desmoplastic stroma. The basaloid islands are narrow and cordlike with growth parallel to the surface epidermis and do not dive deeply into the deep dermis or subcutis. Ductal differentiation with associated secretions typically is not seen in DTE.1 Calcifications and foreign body granulomatous infiltrates may be present. Merkel cells also are present in this tumor and may be highlighted by immunohistochemistry with cytokeratin 20.14 Rarely, desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas may transform into trichoblastic carcinomas. Treatment may consist of surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

Morpheaform BCC also is included in the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnosis of infiltrative basaloid neoplasms. It is one of the more aggressive variants of BCC. The use of immunohistochemical staining may aid in differentiating between these sclerosing adnexal neoplasms.15 For example, pleckstrin homologylike domain family A member 1 (PHLDA1) is a stem cell marker that is heavily expressed in DTE as a specific follicular bulge marker but is not present in a morpheaform BCC. This highlights the follicular nature of DTEs at the molecular level. BerEP4 is a monoclonal antibody that serves as an epithelial marker for 2 glycopolypeptides: 34 and 39 kDa. This antibody may demonstrate positivity in morpheaform BCC but does not stain cells of interest in MAC.

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus clinically presents with erythematous and warty papules in a linear distribution following the Blaschko lines. The papules often are reported to be intensely pruritic and usually are localized to one extremity.16 Although adultonset forms of ILVEN have been described,17 it most commonly is diagnosed in young children. Histologically, ILVEN consists of psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with alternating areas of parakeratosis and orthokeratosis with underlying agranulosis and hypergranulosis, respectively.18 The upper dermis contains a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Treatment with laser therapy and surgical excision has led to both symptomatic and clinical improvement of ILVEN.16

Plaque-type syringomas are a rare variant of syringomas that clinically may mimic other common inflammatory and neoplastic conditions. An adequate biopsy is imperative to differentiate between adnexal neoplasms, as a small superficial biopsy of a syringoma may demonstrate features observed in other malignant or locally aggressive neoplasms. In our patient, the small ducts lined by cuboidal epithelium with no cellular atypia and no deep dermal growth or perineural invasion allowed for the diagnosis of PTS. Therapeutic options were reviewed with our patient, including oral isotretinoin, laser therapy, and staged excision. Ultimately, our patient elected not to pursue treatment, and she is being monitored clinically for any changes in appearance or symptoms.

- Suwattee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma [published online November 12, 2007]. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Furue M, Hori Y, Nakabayashi Y. Clear-cell syringoma. association with diabetes mellitus. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:131-138.

- Kikuchi I, Idemori M, Okazaki M. Plaque type syringoma. J Dermatol. 1979;6:329-331.

- Kavala M, Can B, Zindanci I, et al. Vulvar pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:831-832.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Okuda H, Tei N, Shimizu K, et al. Chondroid syringoma of the scrotum. Int J Urol. 2008;15:944-945.

- Wallace JS, Bond JS, Seidel GD, et al. An important mimicker: plaquetype syringoma mistakenly diagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:810-812.

- Clark M, Duprey C, Sutton A, et al. Plaque-type syringoma masquerading as microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of the literature and description of a novel technique that emphasizes lesion architecture to help make the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:E98-E101.

- Wallace ML, Smoller BR. Progesterone receptor positivity supports hormonal control of syringomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:442-445.

- Mainitz M, Schmidt JB, Gebhart W. Response of multiple syringomas to isotretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1986;66:51-55.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Pujol RM, LeBoit PE, Su WP. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma with extensive sebaceous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:358-362.

- Rahman J, Tahir M, Arekemase H, et al. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: histopathologic and immunohistochemical criteria for differentiation of a rare benign hair follicle tumor from other cutaneous adnexal tumors. Cureus. 2020;12:E9703.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Sellheyer K, Nelson P, Kutzner H, et al. The immunohistochemical differential diagnosis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and morpheaform basal cell carcinoma using BerEP4 and stem cell markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:363-370.

- Gianfaldoni S, Tchernev G, Gianfaldoni R, et al. A case of “inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus” (ILVEN) treated with CO2 laser ablation. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5:454-457.

- Kawaguchi H, Takeuchi M, Ono H, et al. Adult onset of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus [published online October 27, 1999]. J Dermatol. 1999;26:599-602.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA, Prenshaw KL, et al. The psoriasiform reaction pattern. In: Patterson JW. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2021:99-120.

The Diagnosis: Plaque-type Syringoma

A biopsy demonstrated multiple basaloid islands of tumor cells in the reticular dermis with ductal differentiation, some with a commalike tail. The ducts were lined by 2 to 3 layers of small uniform cuboidal cells without atypia and contained inspissated secretions within the lumina of scattered ducts. There was an associated fibrotic collagenous stroma. There was no evidence of perineural invasion and no deep dermal or subcutaneous extension (Figure 1). Additional cytokeratin immunohistochemical staining highlighted the adnexal proliferation (Figure 2). A diagnosis of plaque-type syringoma (PTS) was made.

Syringomas are benign dermal sweat gland tumors that typically present as flesh-colored papules on the cheeks or periorbital area of young females. Plaque-type tumors as well as papulonodular, eruptive, disseminated, urticaria pigmentosa–like, lichen planus–like, or milialike syringomas also have been reported. Syringomas may be associated with certain medical conditions such as Down syndrome, Nicolau-Balus syndrome, and both scarring and nonscarring alopecias.1 The clear cell variant of syringoma often is associated with diabetes mellitus.2 Kikuchi et al3 first described PTS in 1979. Plaque-type syringomas rarely are reported in the literature, and sites of involvement include the head and neck region, upper lip, chest, upper extremities, vulva, penis, and scrotum.4-6

Histologically, syringomatous lesions are composed of multiple small ducts lined by 2 to 3 layers of cuboidal epithelium. The ducts may be arranged in nests or strands of basaloid cells surrounded by a dense fibrotic stroma. Occasionally, the ducts will form a comma- or teardropshaped tail; however, this also may be observed in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma (DTE).7 Perineural invasion is absent in syringomas. Syringomas exhibit a lateral growth pattern that typically is limited to the upper half of the reticular dermis and spares the underlying subcutis, muscle, and bone. The growth pattern may be discontinuous with proliferations juxtaposed by normal-appearing skin.8 Syringomas usually express progesterone receptors and are known to proliferate at puberty, suggesting that these neoplasms are under hormonal control.9 Although syringomas are benign, various treatment options that may be pursued for cosmetic purposes include radiofrequency, staged excision, laser ablation, and oral isotretinoin.8,10 If only a superficial biopsy is obtained, syringomas may display features of other adnexal neoplasms, including microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), DTE, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN).

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is a locally aggressive neoplasm first described by Goldstein et al11 in 1982 an indurated, ill-defined plaque or nodule on the face with a predilection for the upper and lower lip. Prior radiation therapy and immunosuppression are risk factors for the development of MAC.12 Histologically, the superficial portion displays small cornifying cysts interspersed with islands of basaloid cells and may mimic a syringoma. However, the deeper portions demonstrate ducts lined by a single layer of cells with a background of hyalinized and sclerotic stroma. The tumor cells may occupy the deep dermis and underlying subcutis, muscle, or bone and demonstrate an infiltrative growth pattern and perineural invasion. Treatment includes Mohs micrographic surgery.

Desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas most commonly present as solitary white to yellowish annular papules or plaques with a central dell located on sun-exposed areas of the face, cheeks, or chin. This benign neoplasm has a bimodal age distribution, primarily affecting females either in childhood or adulthood.13 Histologically, strands and nests of basaloid epithelial cells proliferate in a dense eosinophilic desmoplastic stroma. The basaloid islands are narrow and cordlike with growth parallel to the surface epidermis and do not dive deeply into the deep dermis or subcutis. Ductal differentiation with associated secretions typically is not seen in DTE.1 Calcifications and foreign body granulomatous infiltrates may be present. Merkel cells also are present in this tumor and may be highlighted by immunohistochemistry with cytokeratin 20.14 Rarely, desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas may transform into trichoblastic carcinomas. Treatment may consist of surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

Morpheaform BCC also is included in the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnosis of infiltrative basaloid neoplasms. It is one of the more aggressive variants of BCC. The use of immunohistochemical staining may aid in differentiating between these sclerosing adnexal neoplasms.15 For example, pleckstrin homologylike domain family A member 1 (PHLDA1) is a stem cell marker that is heavily expressed in DTE as a specific follicular bulge marker but is not present in a morpheaform BCC. This highlights the follicular nature of DTEs at the molecular level. BerEP4 is a monoclonal antibody that serves as an epithelial marker for 2 glycopolypeptides: 34 and 39 kDa. This antibody may demonstrate positivity in morpheaform BCC but does not stain cells of interest in MAC.

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus clinically presents with erythematous and warty papules in a linear distribution following the Blaschko lines. The papules often are reported to be intensely pruritic and usually are localized to one extremity.16 Although adultonset forms of ILVEN have been described,17 it most commonly is diagnosed in young children. Histologically, ILVEN consists of psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with alternating areas of parakeratosis and orthokeratosis with underlying agranulosis and hypergranulosis, respectively.18 The upper dermis contains a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Treatment with laser therapy and surgical excision has led to both symptomatic and clinical improvement of ILVEN.16

Plaque-type syringomas are a rare variant of syringomas that clinically may mimic other common inflammatory and neoplastic conditions. An adequate biopsy is imperative to differentiate between adnexal neoplasms, as a small superficial biopsy of a syringoma may demonstrate features observed in other malignant or locally aggressive neoplasms. In our patient, the small ducts lined by cuboidal epithelium with no cellular atypia and no deep dermal growth or perineural invasion allowed for the diagnosis of PTS. Therapeutic options were reviewed with our patient, including oral isotretinoin, laser therapy, and staged excision. Ultimately, our patient elected not to pursue treatment, and she is being monitored clinically for any changes in appearance or symptoms.

The Diagnosis: Plaque-type Syringoma

A biopsy demonstrated multiple basaloid islands of tumor cells in the reticular dermis with ductal differentiation, some with a commalike tail. The ducts were lined by 2 to 3 layers of small uniform cuboidal cells without atypia and contained inspissated secretions within the lumina of scattered ducts. There was an associated fibrotic collagenous stroma. There was no evidence of perineural invasion and no deep dermal or subcutaneous extension (Figure 1). Additional cytokeratin immunohistochemical staining highlighted the adnexal proliferation (Figure 2). A diagnosis of plaque-type syringoma (PTS) was made.

Syringomas are benign dermal sweat gland tumors that typically present as flesh-colored papules on the cheeks or periorbital area of young females. Plaque-type tumors as well as papulonodular, eruptive, disseminated, urticaria pigmentosa–like, lichen planus–like, or milialike syringomas also have been reported. Syringomas may be associated with certain medical conditions such as Down syndrome, Nicolau-Balus syndrome, and both scarring and nonscarring alopecias.1 The clear cell variant of syringoma often is associated with diabetes mellitus.2 Kikuchi et al3 first described PTS in 1979. Plaque-type syringomas rarely are reported in the literature, and sites of involvement include the head and neck region, upper lip, chest, upper extremities, vulva, penis, and scrotum.4-6

Histologically, syringomatous lesions are composed of multiple small ducts lined by 2 to 3 layers of cuboidal epithelium. The ducts may be arranged in nests or strands of basaloid cells surrounded by a dense fibrotic stroma. Occasionally, the ducts will form a comma- or teardropshaped tail; however, this also may be observed in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma (DTE).7 Perineural invasion is absent in syringomas. Syringomas exhibit a lateral growth pattern that typically is limited to the upper half of the reticular dermis and spares the underlying subcutis, muscle, and bone. The growth pattern may be discontinuous with proliferations juxtaposed by normal-appearing skin.8 Syringomas usually express progesterone receptors and are known to proliferate at puberty, suggesting that these neoplasms are under hormonal control.9 Although syringomas are benign, various treatment options that may be pursued for cosmetic purposes include radiofrequency, staged excision, laser ablation, and oral isotretinoin.8,10 If only a superficial biopsy is obtained, syringomas may display features of other adnexal neoplasms, including microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), DTE, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN).

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is a locally aggressive neoplasm first described by Goldstein et al11 in 1982 an indurated, ill-defined plaque or nodule on the face with a predilection for the upper and lower lip. Prior radiation therapy and immunosuppression are risk factors for the development of MAC.12 Histologically, the superficial portion displays small cornifying cysts interspersed with islands of basaloid cells and may mimic a syringoma. However, the deeper portions demonstrate ducts lined by a single layer of cells with a background of hyalinized and sclerotic stroma. The tumor cells may occupy the deep dermis and underlying subcutis, muscle, or bone and demonstrate an infiltrative growth pattern and perineural invasion. Treatment includes Mohs micrographic surgery.

Desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas most commonly present as solitary white to yellowish annular papules or plaques with a central dell located on sun-exposed areas of the face, cheeks, or chin. This benign neoplasm has a bimodal age distribution, primarily affecting females either in childhood or adulthood.13 Histologically, strands and nests of basaloid epithelial cells proliferate in a dense eosinophilic desmoplastic stroma. The basaloid islands are narrow and cordlike with growth parallel to the surface epidermis and do not dive deeply into the deep dermis or subcutis. Ductal differentiation with associated secretions typically is not seen in DTE.1 Calcifications and foreign body granulomatous infiltrates may be present. Merkel cells also are present in this tumor and may be highlighted by immunohistochemistry with cytokeratin 20.14 Rarely, desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas may transform into trichoblastic carcinomas. Treatment may consist of surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

Morpheaform BCC also is included in the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnosis of infiltrative basaloid neoplasms. It is one of the more aggressive variants of BCC. The use of immunohistochemical staining may aid in differentiating between these sclerosing adnexal neoplasms.15 For example, pleckstrin homologylike domain family A member 1 (PHLDA1) is a stem cell marker that is heavily expressed in DTE as a specific follicular bulge marker but is not present in a morpheaform BCC. This highlights the follicular nature of DTEs at the molecular level. BerEP4 is a monoclonal antibody that serves as an epithelial marker for 2 glycopolypeptides: 34 and 39 kDa. This antibody may demonstrate positivity in morpheaform BCC but does not stain cells of interest in MAC.

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus clinically presents with erythematous and warty papules in a linear distribution following the Blaschko lines. The papules often are reported to be intensely pruritic and usually are localized to one extremity.16 Although adultonset forms of ILVEN have been described,17 it most commonly is diagnosed in young children. Histologically, ILVEN consists of psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with alternating areas of parakeratosis and orthokeratosis with underlying agranulosis and hypergranulosis, respectively.18 The upper dermis contains a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Treatment with laser therapy and surgical excision has led to both symptomatic and clinical improvement of ILVEN.16

Plaque-type syringomas are a rare variant of syringomas that clinically may mimic other common inflammatory and neoplastic conditions. An adequate biopsy is imperative to differentiate between adnexal neoplasms, as a small superficial biopsy of a syringoma may demonstrate features observed in other malignant or locally aggressive neoplasms. In our patient, the small ducts lined by cuboidal epithelium with no cellular atypia and no deep dermal growth or perineural invasion allowed for the diagnosis of PTS. Therapeutic options were reviewed with our patient, including oral isotretinoin, laser therapy, and staged excision. Ultimately, our patient elected not to pursue treatment, and she is being monitored clinically for any changes in appearance or symptoms.

- Suwattee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma [published online November 12, 2007]. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Furue M, Hori Y, Nakabayashi Y. Clear-cell syringoma. association with diabetes mellitus. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:131-138.

- Kikuchi I, Idemori M, Okazaki M. Plaque type syringoma. J Dermatol. 1979;6:329-331.

- Kavala M, Can B, Zindanci I, et al. Vulvar pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:831-832.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Okuda H, Tei N, Shimizu K, et al. Chondroid syringoma of the scrotum. Int J Urol. 2008;15:944-945.

- Wallace JS, Bond JS, Seidel GD, et al. An important mimicker: plaquetype syringoma mistakenly diagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:810-812.

- Clark M, Duprey C, Sutton A, et al. Plaque-type syringoma masquerading as microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of the literature and description of a novel technique that emphasizes lesion architecture to help make the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:E98-E101.

- Wallace ML, Smoller BR. Progesterone receptor positivity supports hormonal control of syringomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:442-445.

- Mainitz M, Schmidt JB, Gebhart W. Response of multiple syringomas to isotretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1986;66:51-55.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Pujol RM, LeBoit PE, Su WP. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma with extensive sebaceous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:358-362.

- Rahman J, Tahir M, Arekemase H, et al. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: histopathologic and immunohistochemical criteria for differentiation of a rare benign hair follicle tumor from other cutaneous adnexal tumors. Cureus. 2020;12:E9703.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Sellheyer K, Nelson P, Kutzner H, et al. The immunohistochemical differential diagnosis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and morpheaform basal cell carcinoma using BerEP4 and stem cell markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:363-370.

- Gianfaldoni S, Tchernev G, Gianfaldoni R, et al. A case of “inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus” (ILVEN) treated with CO2 laser ablation. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5:454-457.

- Kawaguchi H, Takeuchi M, Ono H, et al. Adult onset of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus [published online October 27, 1999]. J Dermatol. 1999;26:599-602.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA, Prenshaw KL, et al. The psoriasiform reaction pattern. In: Patterson JW. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2021:99-120.

- Suwattee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma [published online November 12, 2007]. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Furue M, Hori Y, Nakabayashi Y. Clear-cell syringoma. association with diabetes mellitus. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:131-138.

- Kikuchi I, Idemori M, Okazaki M. Plaque type syringoma. J Dermatol. 1979;6:329-331.

- Kavala M, Can B, Zindanci I, et al. Vulvar pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:831-832.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Okuda H, Tei N, Shimizu K, et al. Chondroid syringoma of the scrotum. Int J Urol. 2008;15:944-945.

- Wallace JS, Bond JS, Seidel GD, et al. An important mimicker: plaquetype syringoma mistakenly diagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:810-812.

- Clark M, Duprey C, Sutton A, et al. Plaque-type syringoma masquerading as microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of the literature and description of a novel technique that emphasizes lesion architecture to help make the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:E98-E101.

- Wallace ML, Smoller BR. Progesterone receptor positivity supports hormonal control of syringomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:442-445.

- Mainitz M, Schmidt JB, Gebhart W. Response of multiple syringomas to isotretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1986;66:51-55.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Pujol RM, LeBoit PE, Su WP. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma with extensive sebaceous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:358-362.

- Rahman J, Tahir M, Arekemase H, et al. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: histopathologic and immunohistochemical criteria for differentiation of a rare benign hair follicle tumor from other cutaneous adnexal tumors. Cureus. 2020;12:E9703.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Sellheyer K, Nelson P, Kutzner H, et al. The immunohistochemical differential diagnosis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and morpheaform basal cell carcinoma using BerEP4 and stem cell markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:363-370.

- Gianfaldoni S, Tchernev G, Gianfaldoni R, et al. A case of “inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus” (ILVEN) treated with CO2 laser ablation. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5:454-457.

- Kawaguchi H, Takeuchi M, Ono H, et al. Adult onset of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus [published online October 27, 1999]. J Dermatol. 1999;26:599-602.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA, Prenshaw KL, et al. The psoriasiform reaction pattern. In: Patterson JW. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2021:99-120.

A 17-year-old adolescent girl presented with a solitary, 8-cm, pink plaque on the anterior aspect of the neck of 5 years’ duration. No similar skin findings were present elsewhere on the body. The rash was not painful or pruritic, and she denied prior trauma to the site. The patient previously had tried a salicylic acid bodywash as well as mupirocin cream 2% and mometasone ointment with no improvement. Her medical history was unremarkable, and she had no known allergies. There was no family history of a similar rash. Physical examination revealed no palpable subcutaneous lumps or masses and no lymphadenopathy of the head or neck. An incisional biopsy was performed.

Progressive Telangiectatic Rash

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an idiopathic microangiopathy of the small vessels in the superficial dermis. A condition first identified by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000, CCV likely is underreported, as its clinical mimickers are not routinely biopsied.2 It presents as asymptomatic telangiectatic macules, initially on the lower extremities and often spreading to the trunk. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy often is seen in middle-aged adults, and most patients have comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or cardiovascular disease. The exact etiology of this disease is unknown.3,4

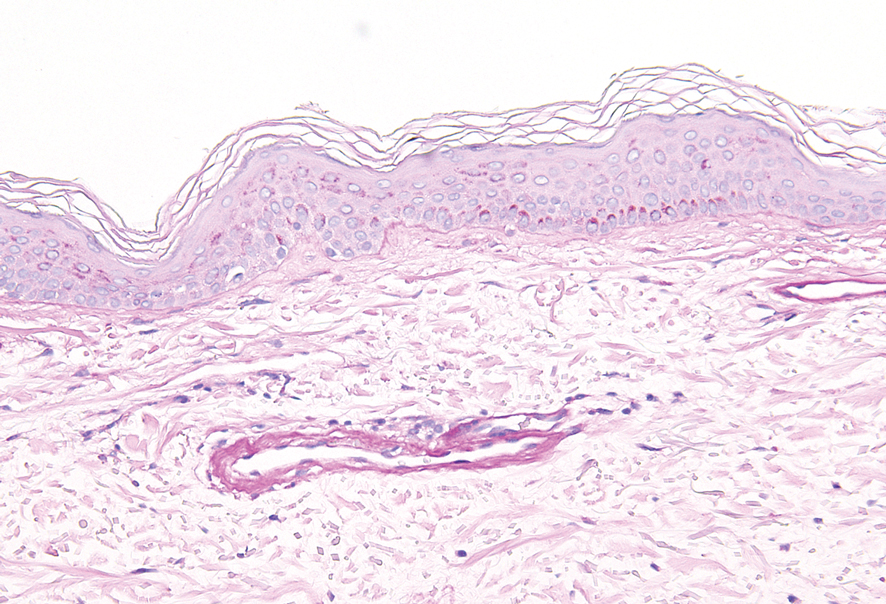

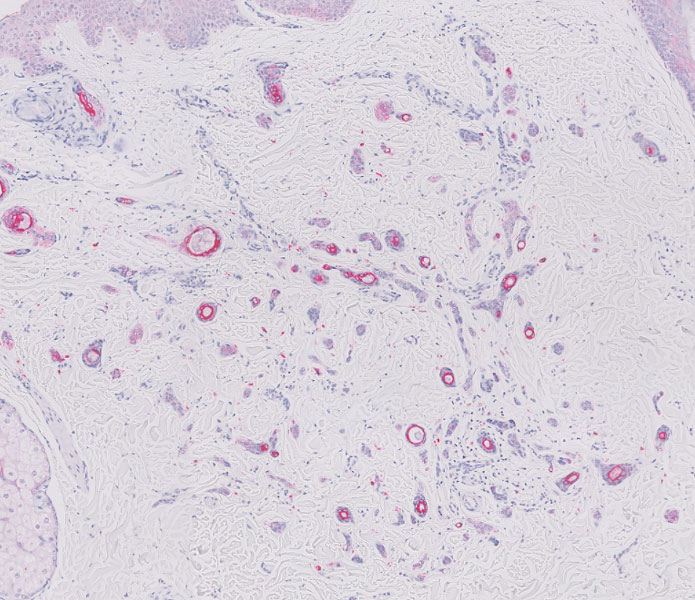

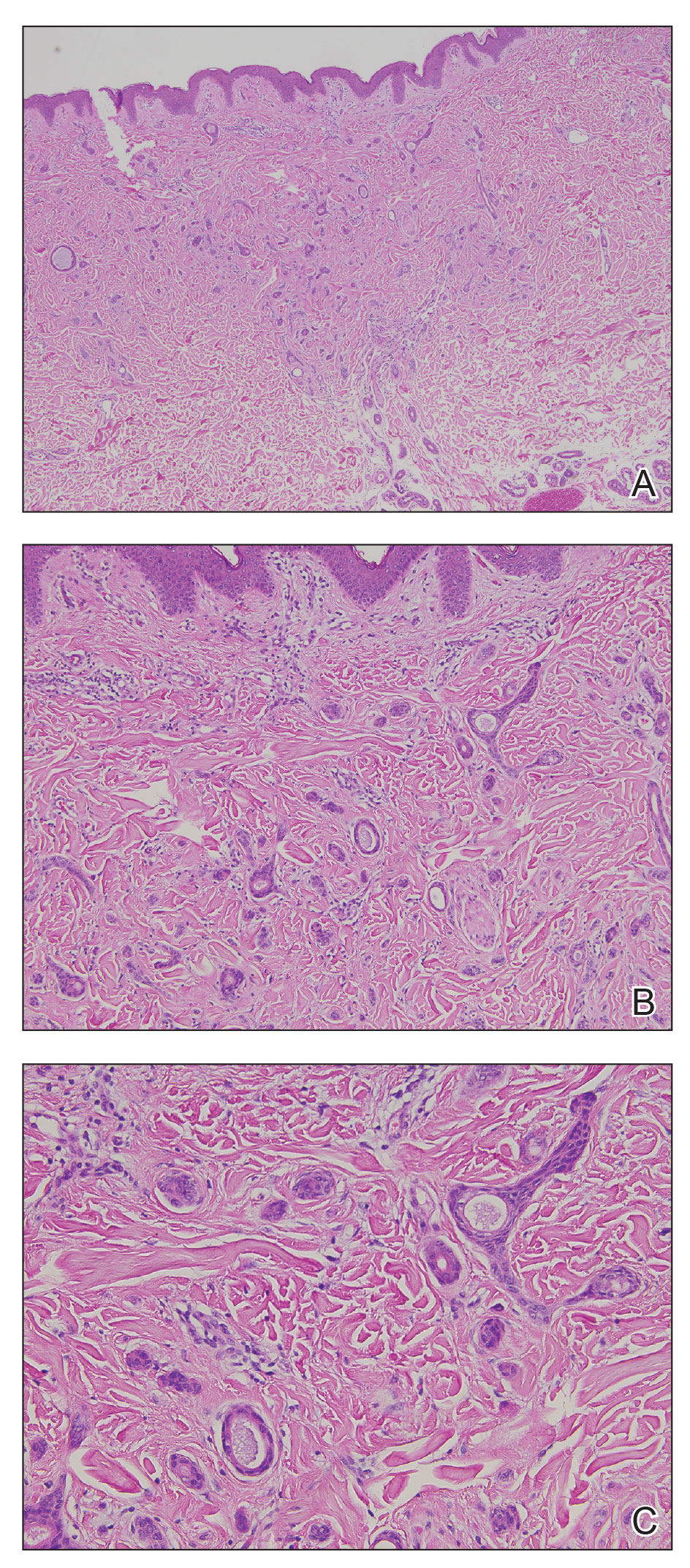

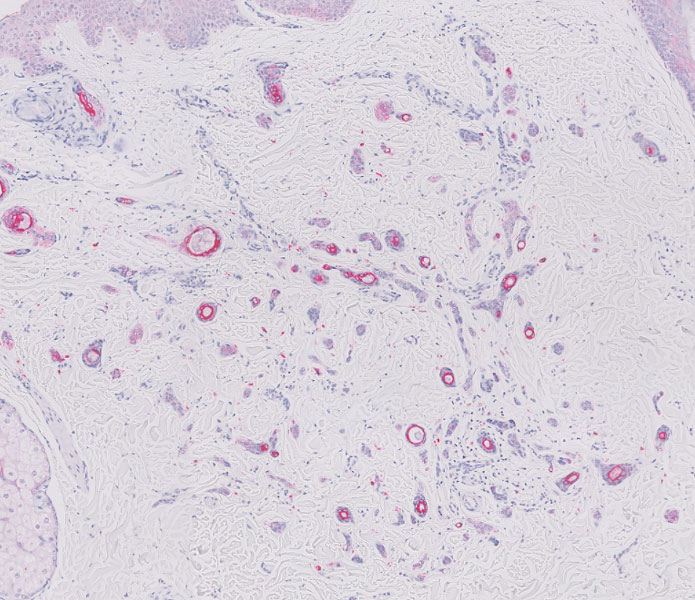

Histopathologically, CCV is characterized by dilated superficial vessels with thickened eosinophilic walls. The eosinophilic material is composed of hyalinized type IV collagen, which is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 1).3,4 Stains for amyloid are negative.

Generalized essential telangiectasia (GET) is a condition that presents with symmetric, blanchable, erythematous telangiectases.5 These lesions can occur alone or can accompany systemic diseases. Similar to CCV, the telangiectases tend to begin on the legs before gradually spreading to the trunk; however, this process more often is seen in females and occurs at an earlier age. Unlike CCV, GET can occur on mucosal surfaces, with cases of conjunctival and oral involvement reported.6 Generalized essential telangiectasia usually is a diagnosis of exclusion.7,8 It is thought that many CCV lesions have been misclassified clinically as GET, which highlights the importance of biopsy. Microscopically, GET is distinct from CCV in that the superficial dermis lacks thick-walled vessels.5,7 Although usually not associated with systemic diseases or progressive morbidity, treatment options are limited.8

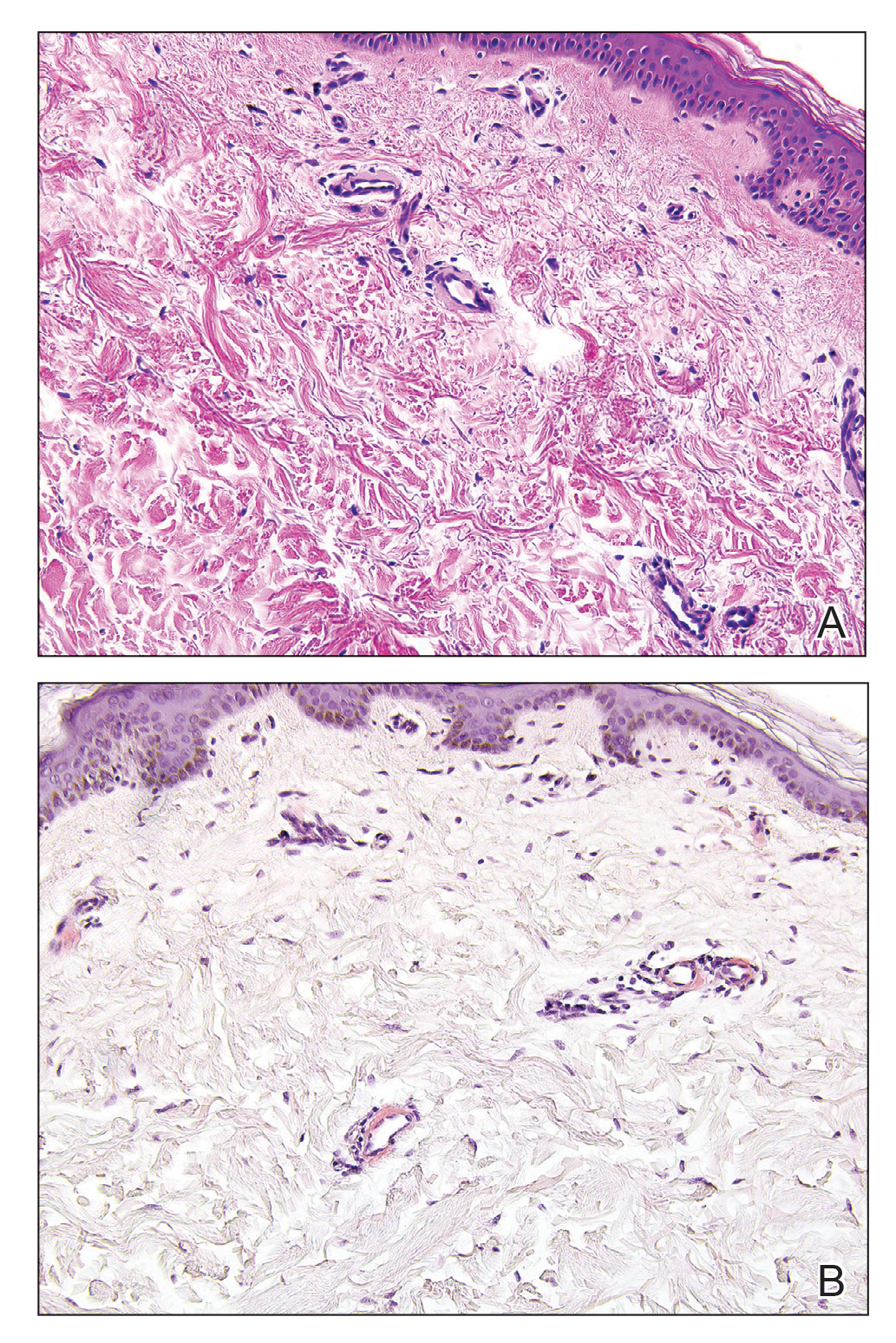

Livedoid vasculopathy, also known as atrophie blanche, is caused by fibrin thrombi occlusion of dermal vessels. Clinically, patients have recurrent telangiectatic papules and painful ulcers on the lower extremities that gradually heal, leaving behind white stellate scars. It is caused by an underlying prothrombotic state with a superimposed inflammatory response.9 Livedoid vasculopathy primarily affects middle-aged women, and many patients have comorbidities such as scleroderma or systemic lupus erythematosus. Histologically, the epidermis often is ulcerated, and thrombi are visualized within small vessels. Eosinophilic fibrinoid material is deposited in vessel walls, including but not confined to vessels at the base of the epidermal ulcer (Figure 2). The fibrinoid material is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant and can be highlighted with immunofluorescence, which may help to distinguish this entity from CCV.1,9 As the disease progresses, vessels are diffusely hyalinized, and there is epidermal atrophy and dermal sclerosis. Treatment options include antiplatelet and fibrinolytic drugs with a multidisciplinary approach to resolve pain and scarring.9

Primary systemic amyloidosis is a rare condition, and cutaneous manifestations are seen in approximately one-third of affected individuals. Amyloid deposition results in waxy papules that predominantly affect the face and periorbital areas but also may occur on the neck, flexural areas, and genitalia.5 Because the amyloid deposits also can be found within vessel walls, hemorrhagic lesions may occur. Microscopically, amorphous eosinophilic material can be found within the vessel walls, similar to CCV (Figure 3A); however, when stained with Congo red, cutaneous amyloidosis shows waxy red-orange material involving the vessel walls and exhibits apple green birefringence under polarization (Figure 3B).10 Amyloid also will be negative for type IV collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, whereas CCV will be positive.5

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Bondier L, Tardieu M, Leveque P, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of two cases presenting as disseminated telangiectasias and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:682-688.

- Sartori DS, Almeida HL Jr, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52.

- Patterson JW, ed. Vascular tumors. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016:1069-1115.

- Knöpfel N, Martín-Santiago A, Saus C, et al. Extensive acquired telangiectasias: comparison of generalized essential telangiectasia and cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:E21-E26.

- Karimkhani C, Boyers LN, Olivere J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Cutis. 2019;103:E7-E8.

- McGrae JD, Winkelmann RK. Generalized essential telangiectasia: report of a clinical and histochemical study of 13 patients with acquired cutaneous lesions. JAMA. 1963;185:909-913.

- Vasudeva B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478.

- Ko CJ, Barr RJ. Color--pink. In: Ko CJ, Barr RJ, eds. Dermatopathology: Diagnosis by First Impression. 3rd ed. Wiley; 2016:303-322.

- Clark ML, McGuinness AE, Vidal CI. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a unique case with positive direct immunofluorescence findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:77-79.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an idiopathic microangiopathy of the small vessels in the superficial dermis. A condition first identified by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000, CCV likely is underreported, as its clinical mimickers are not routinely biopsied.2 It presents as asymptomatic telangiectatic macules, initially on the lower extremities and often spreading to the trunk. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy often is seen in middle-aged adults, and most patients have comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or cardiovascular disease. The exact etiology of this disease is unknown.3,4

Histopathologically, CCV is characterized by dilated superficial vessels with thickened eosinophilic walls. The eosinophilic material is composed of hyalinized type IV collagen, which is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 1).3,4 Stains for amyloid are negative.

Generalized essential telangiectasia (GET) is a condition that presents with symmetric, blanchable, erythematous telangiectases.5 These lesions can occur alone or can accompany systemic diseases. Similar to CCV, the telangiectases tend to begin on the legs before gradually spreading to the trunk; however, this process more often is seen in females and occurs at an earlier age. Unlike CCV, GET can occur on mucosal surfaces, with cases of conjunctival and oral involvement reported.6 Generalized essential telangiectasia usually is a diagnosis of exclusion.7,8 It is thought that many CCV lesions have been misclassified clinically as GET, which highlights the importance of biopsy. Microscopically, GET is distinct from CCV in that the superficial dermis lacks thick-walled vessels.5,7 Although usually not associated with systemic diseases or progressive morbidity, treatment options are limited.8

Livedoid vasculopathy, also known as atrophie blanche, is caused by fibrin thrombi occlusion of dermal vessels. Clinically, patients have recurrent telangiectatic papules and painful ulcers on the lower extremities that gradually heal, leaving behind white stellate scars. It is caused by an underlying prothrombotic state with a superimposed inflammatory response.9 Livedoid vasculopathy primarily affects middle-aged women, and many patients have comorbidities such as scleroderma or systemic lupus erythematosus. Histologically, the epidermis often is ulcerated, and thrombi are visualized within small vessels. Eosinophilic fibrinoid material is deposited in vessel walls, including but not confined to vessels at the base of the epidermal ulcer (Figure 2). The fibrinoid material is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant and can be highlighted with immunofluorescence, which may help to distinguish this entity from CCV.1,9 As the disease progresses, vessels are diffusely hyalinized, and there is epidermal atrophy and dermal sclerosis. Treatment options include antiplatelet and fibrinolytic drugs with a multidisciplinary approach to resolve pain and scarring.9

Primary systemic amyloidosis is a rare condition, and cutaneous manifestations are seen in approximately one-third of affected individuals. Amyloid deposition results in waxy papules that predominantly affect the face and periorbital areas but also may occur on the neck, flexural areas, and genitalia.5 Because the amyloid deposits also can be found within vessel walls, hemorrhagic lesions may occur. Microscopically, amorphous eosinophilic material can be found within the vessel walls, similar to CCV (Figure 3A); however, when stained with Congo red, cutaneous amyloidosis shows waxy red-orange material involving the vessel walls and exhibits apple green birefringence under polarization (Figure 3B).10 Amyloid also will be negative for type IV collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, whereas CCV will be positive.5

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an idiopathic microangiopathy of the small vessels in the superficial dermis. A condition first identified by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000, CCV likely is underreported, as its clinical mimickers are not routinely biopsied.2 It presents as asymptomatic telangiectatic macules, initially on the lower extremities and often spreading to the trunk. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy often is seen in middle-aged adults, and most patients have comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or cardiovascular disease. The exact etiology of this disease is unknown.3,4

Histopathologically, CCV is characterized by dilated superficial vessels with thickened eosinophilic walls. The eosinophilic material is composed of hyalinized type IV collagen, which is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 1).3,4 Stains for amyloid are negative.

Generalized essential telangiectasia (GET) is a condition that presents with symmetric, blanchable, erythematous telangiectases.5 These lesions can occur alone or can accompany systemic diseases. Similar to CCV, the telangiectases tend to begin on the legs before gradually spreading to the trunk; however, this process more often is seen in females and occurs at an earlier age. Unlike CCV, GET can occur on mucosal surfaces, with cases of conjunctival and oral involvement reported.6 Generalized essential telangiectasia usually is a diagnosis of exclusion.7,8 It is thought that many CCV lesions have been misclassified clinically as GET, which highlights the importance of biopsy. Microscopically, GET is distinct from CCV in that the superficial dermis lacks thick-walled vessels.5,7 Although usually not associated with systemic diseases or progressive morbidity, treatment options are limited.8

Livedoid vasculopathy, also known as atrophie blanche, is caused by fibrin thrombi occlusion of dermal vessels. Clinically, patients have recurrent telangiectatic papules and painful ulcers on the lower extremities that gradually heal, leaving behind white stellate scars. It is caused by an underlying prothrombotic state with a superimposed inflammatory response.9 Livedoid vasculopathy primarily affects middle-aged women, and many patients have comorbidities such as scleroderma or systemic lupus erythematosus. Histologically, the epidermis often is ulcerated, and thrombi are visualized within small vessels. Eosinophilic fibrinoid material is deposited in vessel walls, including but not confined to vessels at the base of the epidermal ulcer (Figure 2). The fibrinoid material is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant and can be highlighted with immunofluorescence, which may help to distinguish this entity from CCV.1,9 As the disease progresses, vessels are diffusely hyalinized, and there is epidermal atrophy and dermal sclerosis. Treatment options include antiplatelet and fibrinolytic drugs with a multidisciplinary approach to resolve pain and scarring.9

Primary systemic amyloidosis is a rare condition, and cutaneous manifestations are seen in approximately one-third of affected individuals. Amyloid deposition results in waxy papules that predominantly affect the face and periorbital areas but also may occur on the neck, flexural areas, and genitalia.5 Because the amyloid deposits also can be found within vessel walls, hemorrhagic lesions may occur. Microscopically, amorphous eosinophilic material can be found within the vessel walls, similar to CCV (Figure 3A); however, when stained with Congo red, cutaneous amyloidosis shows waxy red-orange material involving the vessel walls and exhibits apple green birefringence under polarization (Figure 3B).10 Amyloid also will be negative for type IV collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, whereas CCV will be positive.5

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Bondier L, Tardieu M, Leveque P, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of two cases presenting as disseminated telangiectasias and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:682-688.

- Sartori DS, Almeida HL Jr, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52.

- Patterson JW, ed. Vascular tumors. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016:1069-1115.

- Knöpfel N, Martín-Santiago A, Saus C, et al. Extensive acquired telangiectasias: comparison of generalized essential telangiectasia and cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:E21-E26.

- Karimkhani C, Boyers LN, Olivere J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Cutis. 2019;103:E7-E8.

- McGrae JD, Winkelmann RK. Generalized essential telangiectasia: report of a clinical and histochemical study of 13 patients with acquired cutaneous lesions. JAMA. 1963;185:909-913.

- Vasudeva B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478.

- Ko CJ, Barr RJ. Color--pink. In: Ko CJ, Barr RJ, eds. Dermatopathology: Diagnosis by First Impression. 3rd ed. Wiley; 2016:303-322.

- Clark ML, McGuinness AE, Vidal CI. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a unique case with positive direct immunofluorescence findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:77-79.

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Bondier L, Tardieu M, Leveque P, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of two cases presenting as disseminated telangiectasias and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:682-688.

- Sartori DS, Almeida HL Jr, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52.

- Patterson JW, ed. Vascular tumors. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016:1069-1115.

- Knöpfel N, Martín-Santiago A, Saus C, et al. Extensive acquired telangiectasias: comparison of generalized essential telangiectasia and cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:E21-E26.

- Karimkhani C, Boyers LN, Olivere J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Cutis. 2019;103:E7-E8.

- McGrae JD, Winkelmann RK. Generalized essential telangiectasia: report of a clinical and histochemical study of 13 patients with acquired cutaneous lesions. JAMA. 1963;185:909-913.

- Vasudeva B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478.

- Ko CJ, Barr RJ. Color--pink. In: Ko CJ, Barr RJ, eds. Dermatopathology: Diagnosis by First Impression. 3rd ed. Wiley; 2016:303-322.

- Clark ML, McGuinness AE, Vidal CI. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a unique case with positive direct immunofluorescence findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:77-79.

A 54-year-old woman presented with purple-red vessels on the lower legs of 15 years’ duration with gradual proximal progression to involve the thighs, breasts, and forearms. A punch biopsy of the inner thigh was obtained for histopathologic evaluation.