User login

Solitary Pink Plaque on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Plaque-type Syringoma

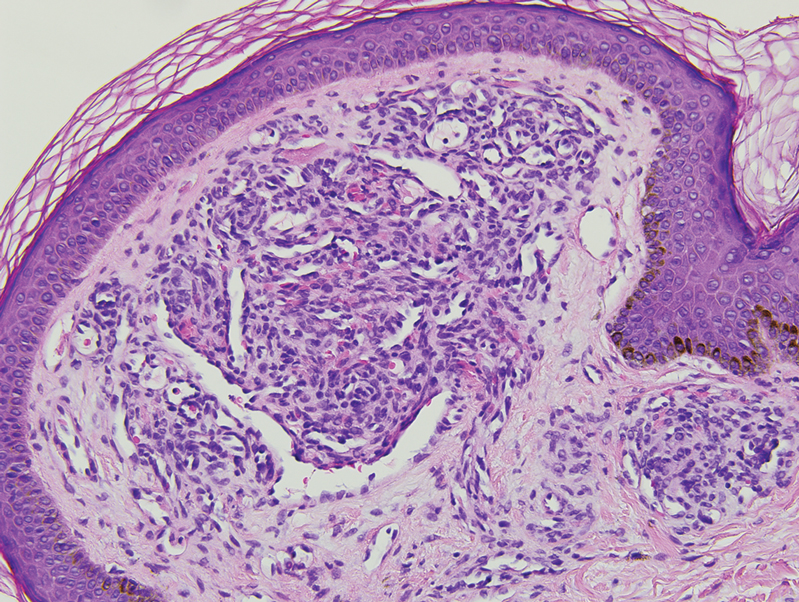

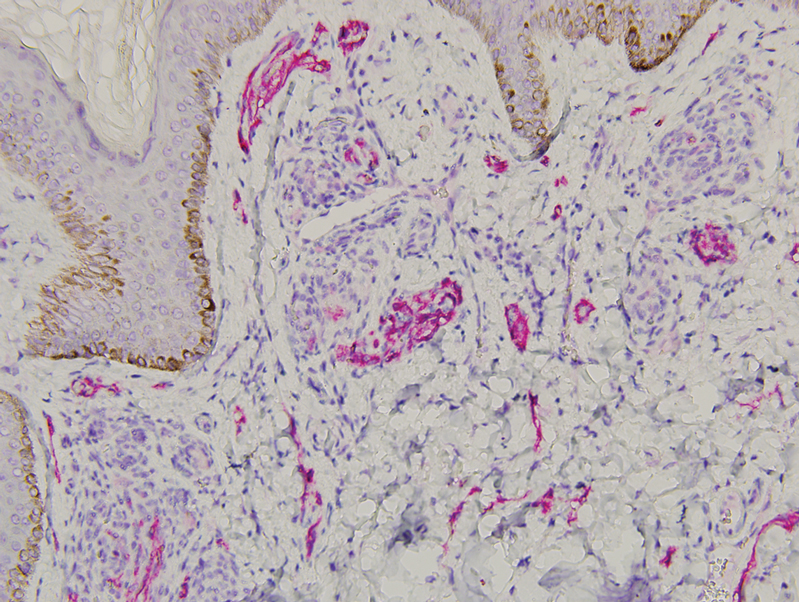

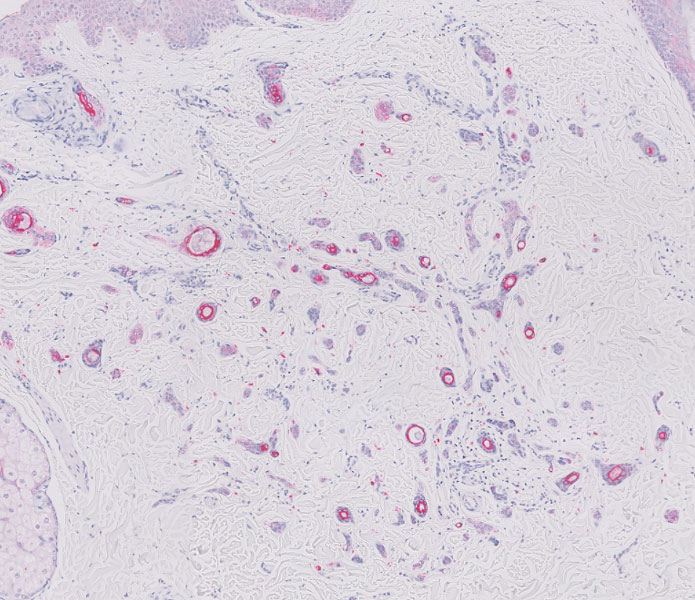

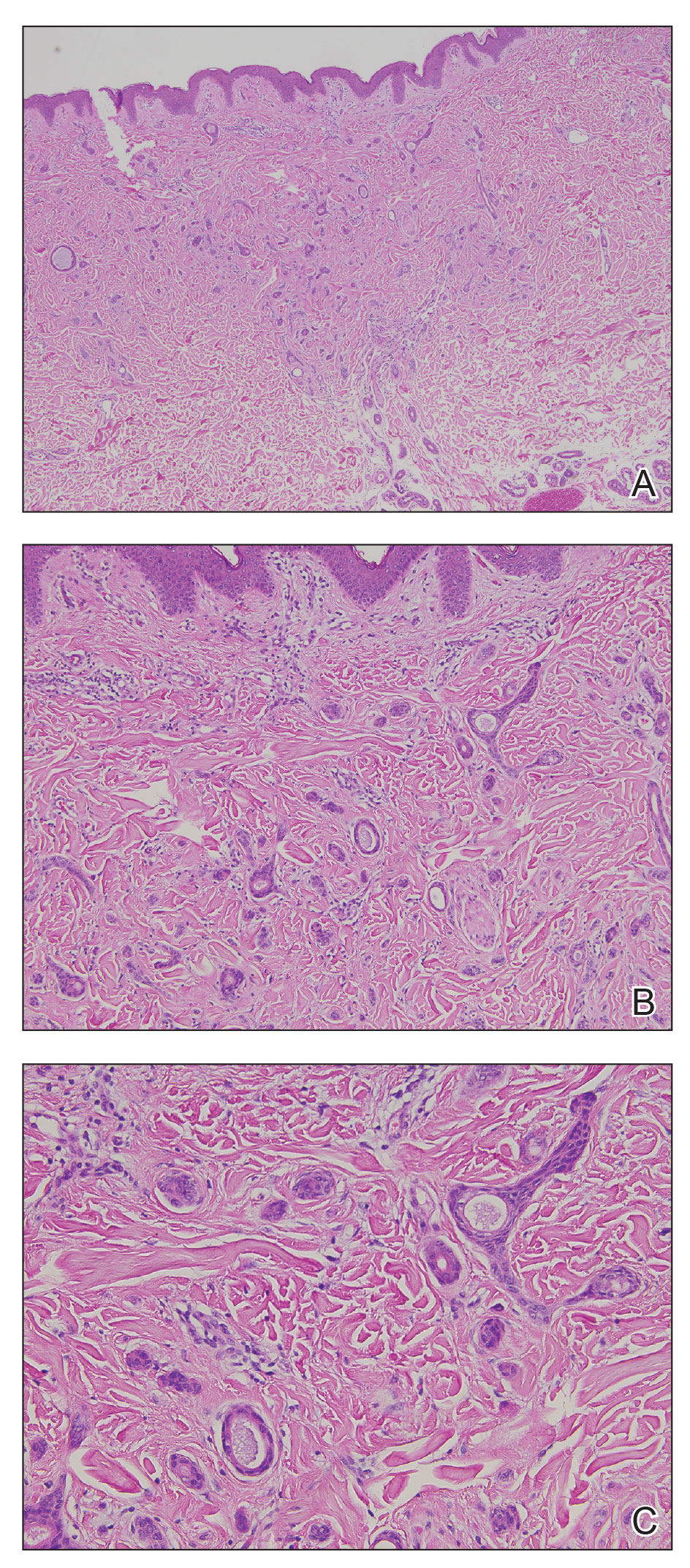

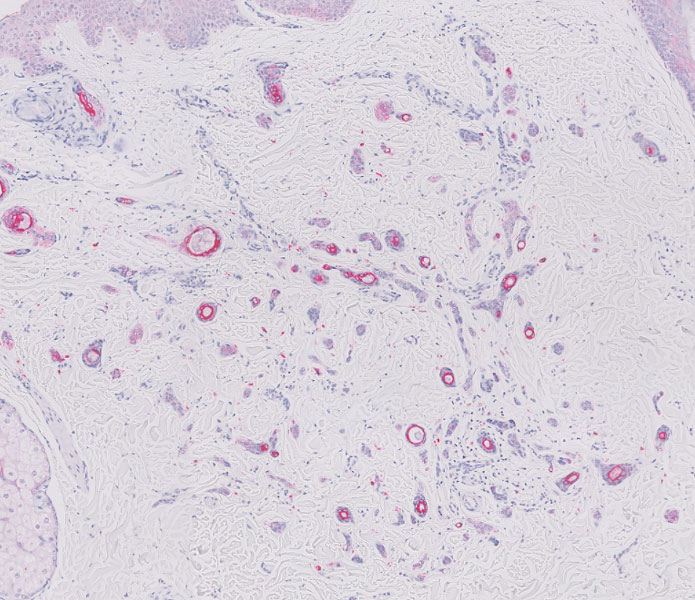

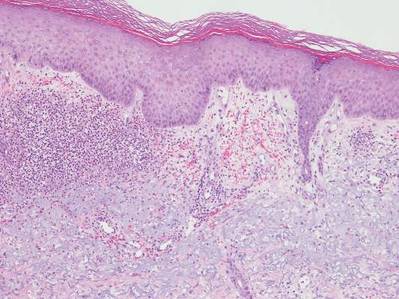

A biopsy demonstrated multiple basaloid islands of tumor cells in the reticular dermis with ductal differentiation, some with a commalike tail. The ducts were lined by 2 to 3 layers of small uniform cuboidal cells without atypia and contained inspissated secretions within the lumina of scattered ducts. There was an associated fibrotic collagenous stroma. There was no evidence of perineural invasion and no deep dermal or subcutaneous extension (Figure 1). Additional cytokeratin immunohistochemical staining highlighted the adnexal proliferation (Figure 2). A diagnosis of plaque-type syringoma (PTS) was made.

Syringomas are benign dermal sweat gland tumors that typically present as flesh-colored papules on the cheeks or periorbital area of young females. Plaque-type tumors as well as papulonodular, eruptive, disseminated, urticaria pigmentosa–like, lichen planus–like, or milialike syringomas also have been reported. Syringomas may be associated with certain medical conditions such as Down syndrome, Nicolau-Balus syndrome, and both scarring and nonscarring alopecias.1 The clear cell variant of syringoma often is associated with diabetes mellitus.2 Kikuchi et al3 first described PTS in 1979. Plaque-type syringomas rarely are reported in the literature, and sites of involvement include the head and neck region, upper lip, chest, upper extremities, vulva, penis, and scrotum.4-6

Histologically, syringomatous lesions are composed of multiple small ducts lined by 2 to 3 layers of cuboidal epithelium. The ducts may be arranged in nests or strands of basaloid cells surrounded by a dense fibrotic stroma. Occasionally, the ducts will form a comma- or teardropshaped tail; however, this also may be observed in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma (DTE).7 Perineural invasion is absent in syringomas. Syringomas exhibit a lateral growth pattern that typically is limited to the upper half of the reticular dermis and spares the underlying subcutis, muscle, and bone. The growth pattern may be discontinuous with proliferations juxtaposed by normal-appearing skin.8 Syringomas usually express progesterone receptors and are known to proliferate at puberty, suggesting that these neoplasms are under hormonal control.9 Although syringomas are benign, various treatment options that may be pursued for cosmetic purposes include radiofrequency, staged excision, laser ablation, and oral isotretinoin.8,10 If only a superficial biopsy is obtained, syringomas may display features of other adnexal neoplasms, including microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), DTE, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN).

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is a locally aggressive neoplasm first described by Goldstein et al11 in 1982 an indurated, ill-defined plaque or nodule on the face with a predilection for the upper and lower lip. Prior radiation therapy and immunosuppression are risk factors for the development of MAC.12 Histologically, the superficial portion displays small cornifying cysts interspersed with islands of basaloid cells and may mimic a syringoma. However, the deeper portions demonstrate ducts lined by a single layer of cells with a background of hyalinized and sclerotic stroma. The tumor cells may occupy the deep dermis and underlying subcutis, muscle, or bone and demonstrate an infiltrative growth pattern and perineural invasion. Treatment includes Mohs micrographic surgery.

Desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas most commonly present as solitary white to yellowish annular papules or plaques with a central dell located on sun-exposed areas of the face, cheeks, or chin. This benign neoplasm has a bimodal age distribution, primarily affecting females either in childhood or adulthood.13 Histologically, strands and nests of basaloid epithelial cells proliferate in a dense eosinophilic desmoplastic stroma. The basaloid islands are narrow and cordlike with growth parallel to the surface epidermis and do not dive deeply into the deep dermis or subcutis. Ductal differentiation with associated secretions typically is not seen in DTE.1 Calcifications and foreign body granulomatous infiltrates may be present. Merkel cells also are present in this tumor and may be highlighted by immunohistochemistry with cytokeratin 20.14 Rarely, desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas may transform into trichoblastic carcinomas. Treatment may consist of surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

Morpheaform BCC also is included in the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnosis of infiltrative basaloid neoplasms. It is one of the more aggressive variants of BCC. The use of immunohistochemical staining may aid in differentiating between these sclerosing adnexal neoplasms.15 For example, pleckstrin homologylike domain family A member 1 (PHLDA1) is a stem cell marker that is heavily expressed in DTE as a specific follicular bulge marker but is not present in a morpheaform BCC. This highlights the follicular nature of DTEs at the molecular level. BerEP4 is a monoclonal antibody that serves as an epithelial marker for 2 glycopolypeptides: 34 and 39 kDa. This antibody may demonstrate positivity in morpheaform BCC but does not stain cells of interest in MAC.

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus clinically presents with erythematous and warty papules in a linear distribution following the Blaschko lines. The papules often are reported to be intensely pruritic and usually are localized to one extremity.16 Although adultonset forms of ILVEN have been described,17 it most commonly is diagnosed in young children. Histologically, ILVEN consists of psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with alternating areas of parakeratosis and orthokeratosis with underlying agranulosis and hypergranulosis, respectively.18 The upper dermis contains a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Treatment with laser therapy and surgical excision has led to both symptomatic and clinical improvement of ILVEN.16

Plaque-type syringomas are a rare variant of syringomas that clinically may mimic other common inflammatory and neoplastic conditions. An adequate biopsy is imperative to differentiate between adnexal neoplasms, as a small superficial biopsy of a syringoma may demonstrate features observed in other malignant or locally aggressive neoplasms. In our patient, the small ducts lined by cuboidal epithelium with no cellular atypia and no deep dermal growth or perineural invasion allowed for the diagnosis of PTS. Therapeutic options were reviewed with our patient, including oral isotretinoin, laser therapy, and staged excision. Ultimately, our patient elected not to pursue treatment, and she is being monitored clinically for any changes in appearance or symptoms.

- Suwattee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma [published online November 12, 2007]. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Furue M, Hori Y, Nakabayashi Y. Clear-cell syringoma. association with diabetes mellitus. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:131-138.

- Kikuchi I, Idemori M, Okazaki M. Plaque type syringoma. J Dermatol. 1979;6:329-331.

- Kavala M, Can B, Zindanci I, et al. Vulvar pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:831-832.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Okuda H, Tei N, Shimizu K, et al. Chondroid syringoma of the scrotum. Int J Urol. 2008;15:944-945.

- Wallace JS, Bond JS, Seidel GD, et al. An important mimicker: plaquetype syringoma mistakenly diagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:810-812.

- Clark M, Duprey C, Sutton A, et al. Plaque-type syringoma masquerading as microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of the literature and description of a novel technique that emphasizes lesion architecture to help make the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:E98-E101.

- Wallace ML, Smoller BR. Progesterone receptor positivity supports hormonal control of syringomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:442-445.

- Mainitz M, Schmidt JB, Gebhart W. Response of multiple syringomas to isotretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1986;66:51-55.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Pujol RM, LeBoit PE, Su WP. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma with extensive sebaceous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:358-362.

- Rahman J, Tahir M, Arekemase H, et al. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: histopathologic and immunohistochemical criteria for differentiation of a rare benign hair follicle tumor from other cutaneous adnexal tumors. Cureus. 2020;12:E9703.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Sellheyer K, Nelson P, Kutzner H, et al. The immunohistochemical differential diagnosis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and morpheaform basal cell carcinoma using BerEP4 and stem cell markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:363-370.

- Gianfaldoni S, Tchernev G, Gianfaldoni R, et al. A case of “inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus” (ILVEN) treated with CO2 laser ablation. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5:454-457.

- Kawaguchi H, Takeuchi M, Ono H, et al. Adult onset of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus [published online October 27, 1999]. J Dermatol. 1999;26:599-602.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA, Prenshaw KL, et al. The psoriasiform reaction pattern. In: Patterson JW. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2021:99-120.

The Diagnosis: Plaque-type Syringoma

A biopsy demonstrated multiple basaloid islands of tumor cells in the reticular dermis with ductal differentiation, some with a commalike tail. The ducts were lined by 2 to 3 layers of small uniform cuboidal cells without atypia and contained inspissated secretions within the lumina of scattered ducts. There was an associated fibrotic collagenous stroma. There was no evidence of perineural invasion and no deep dermal or subcutaneous extension (Figure 1). Additional cytokeratin immunohistochemical staining highlighted the adnexal proliferation (Figure 2). A diagnosis of plaque-type syringoma (PTS) was made.

Syringomas are benign dermal sweat gland tumors that typically present as flesh-colored papules on the cheeks or periorbital area of young females. Plaque-type tumors as well as papulonodular, eruptive, disseminated, urticaria pigmentosa–like, lichen planus–like, or milialike syringomas also have been reported. Syringomas may be associated with certain medical conditions such as Down syndrome, Nicolau-Balus syndrome, and both scarring and nonscarring alopecias.1 The clear cell variant of syringoma often is associated with diabetes mellitus.2 Kikuchi et al3 first described PTS in 1979. Plaque-type syringomas rarely are reported in the literature, and sites of involvement include the head and neck region, upper lip, chest, upper extremities, vulva, penis, and scrotum.4-6

Histologically, syringomatous lesions are composed of multiple small ducts lined by 2 to 3 layers of cuboidal epithelium. The ducts may be arranged in nests or strands of basaloid cells surrounded by a dense fibrotic stroma. Occasionally, the ducts will form a comma- or teardropshaped tail; however, this also may be observed in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma (DTE).7 Perineural invasion is absent in syringomas. Syringomas exhibit a lateral growth pattern that typically is limited to the upper half of the reticular dermis and spares the underlying subcutis, muscle, and bone. The growth pattern may be discontinuous with proliferations juxtaposed by normal-appearing skin.8 Syringomas usually express progesterone receptors and are known to proliferate at puberty, suggesting that these neoplasms are under hormonal control.9 Although syringomas are benign, various treatment options that may be pursued for cosmetic purposes include radiofrequency, staged excision, laser ablation, and oral isotretinoin.8,10 If only a superficial biopsy is obtained, syringomas may display features of other adnexal neoplasms, including microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), DTE, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN).

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is a locally aggressive neoplasm first described by Goldstein et al11 in 1982 an indurated, ill-defined plaque or nodule on the face with a predilection for the upper and lower lip. Prior radiation therapy and immunosuppression are risk factors for the development of MAC.12 Histologically, the superficial portion displays small cornifying cysts interspersed with islands of basaloid cells and may mimic a syringoma. However, the deeper portions demonstrate ducts lined by a single layer of cells with a background of hyalinized and sclerotic stroma. The tumor cells may occupy the deep dermis and underlying subcutis, muscle, or bone and demonstrate an infiltrative growth pattern and perineural invasion. Treatment includes Mohs micrographic surgery.

Desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas most commonly present as solitary white to yellowish annular papules or plaques with a central dell located on sun-exposed areas of the face, cheeks, or chin. This benign neoplasm has a bimodal age distribution, primarily affecting females either in childhood or adulthood.13 Histologically, strands and nests of basaloid epithelial cells proliferate in a dense eosinophilic desmoplastic stroma. The basaloid islands are narrow and cordlike with growth parallel to the surface epidermis and do not dive deeply into the deep dermis or subcutis. Ductal differentiation with associated secretions typically is not seen in DTE.1 Calcifications and foreign body granulomatous infiltrates may be present. Merkel cells also are present in this tumor and may be highlighted by immunohistochemistry with cytokeratin 20.14 Rarely, desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas may transform into trichoblastic carcinomas. Treatment may consist of surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

Morpheaform BCC also is included in the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnosis of infiltrative basaloid neoplasms. It is one of the more aggressive variants of BCC. The use of immunohistochemical staining may aid in differentiating between these sclerosing adnexal neoplasms.15 For example, pleckstrin homologylike domain family A member 1 (PHLDA1) is a stem cell marker that is heavily expressed in DTE as a specific follicular bulge marker but is not present in a morpheaform BCC. This highlights the follicular nature of DTEs at the molecular level. BerEP4 is a monoclonal antibody that serves as an epithelial marker for 2 glycopolypeptides: 34 and 39 kDa. This antibody may demonstrate positivity in morpheaform BCC but does not stain cells of interest in MAC.

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus clinically presents with erythematous and warty papules in a linear distribution following the Blaschko lines. The papules often are reported to be intensely pruritic and usually are localized to one extremity.16 Although adultonset forms of ILVEN have been described,17 it most commonly is diagnosed in young children. Histologically, ILVEN consists of psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with alternating areas of parakeratosis and orthokeratosis with underlying agranulosis and hypergranulosis, respectively.18 The upper dermis contains a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Treatment with laser therapy and surgical excision has led to both symptomatic and clinical improvement of ILVEN.16

Plaque-type syringomas are a rare variant of syringomas that clinically may mimic other common inflammatory and neoplastic conditions. An adequate biopsy is imperative to differentiate between adnexal neoplasms, as a small superficial biopsy of a syringoma may demonstrate features observed in other malignant or locally aggressive neoplasms. In our patient, the small ducts lined by cuboidal epithelium with no cellular atypia and no deep dermal growth or perineural invasion allowed for the diagnosis of PTS. Therapeutic options were reviewed with our patient, including oral isotretinoin, laser therapy, and staged excision. Ultimately, our patient elected not to pursue treatment, and she is being monitored clinically for any changes in appearance or symptoms.

The Diagnosis: Plaque-type Syringoma

A biopsy demonstrated multiple basaloid islands of tumor cells in the reticular dermis with ductal differentiation, some with a commalike tail. The ducts were lined by 2 to 3 layers of small uniform cuboidal cells without atypia and contained inspissated secretions within the lumina of scattered ducts. There was an associated fibrotic collagenous stroma. There was no evidence of perineural invasion and no deep dermal or subcutaneous extension (Figure 1). Additional cytokeratin immunohistochemical staining highlighted the adnexal proliferation (Figure 2). A diagnosis of plaque-type syringoma (PTS) was made.

Syringomas are benign dermal sweat gland tumors that typically present as flesh-colored papules on the cheeks or periorbital area of young females. Plaque-type tumors as well as papulonodular, eruptive, disseminated, urticaria pigmentosa–like, lichen planus–like, or milialike syringomas also have been reported. Syringomas may be associated with certain medical conditions such as Down syndrome, Nicolau-Balus syndrome, and both scarring and nonscarring alopecias.1 The clear cell variant of syringoma often is associated with diabetes mellitus.2 Kikuchi et al3 first described PTS in 1979. Plaque-type syringomas rarely are reported in the literature, and sites of involvement include the head and neck region, upper lip, chest, upper extremities, vulva, penis, and scrotum.4-6

Histologically, syringomatous lesions are composed of multiple small ducts lined by 2 to 3 layers of cuboidal epithelium. The ducts may be arranged in nests or strands of basaloid cells surrounded by a dense fibrotic stroma. Occasionally, the ducts will form a comma- or teardropshaped tail; however, this also may be observed in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma (DTE).7 Perineural invasion is absent in syringomas. Syringomas exhibit a lateral growth pattern that typically is limited to the upper half of the reticular dermis and spares the underlying subcutis, muscle, and bone. The growth pattern may be discontinuous with proliferations juxtaposed by normal-appearing skin.8 Syringomas usually express progesterone receptors and are known to proliferate at puberty, suggesting that these neoplasms are under hormonal control.9 Although syringomas are benign, various treatment options that may be pursued for cosmetic purposes include radiofrequency, staged excision, laser ablation, and oral isotretinoin.8,10 If only a superficial biopsy is obtained, syringomas may display features of other adnexal neoplasms, including microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), DTE, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN).

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is a locally aggressive neoplasm first described by Goldstein et al11 in 1982 an indurated, ill-defined plaque or nodule on the face with a predilection for the upper and lower lip. Prior radiation therapy and immunosuppression are risk factors for the development of MAC.12 Histologically, the superficial portion displays small cornifying cysts interspersed with islands of basaloid cells and may mimic a syringoma. However, the deeper portions demonstrate ducts lined by a single layer of cells with a background of hyalinized and sclerotic stroma. The tumor cells may occupy the deep dermis and underlying subcutis, muscle, or bone and demonstrate an infiltrative growth pattern and perineural invasion. Treatment includes Mohs micrographic surgery.

Desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas most commonly present as solitary white to yellowish annular papules or plaques with a central dell located on sun-exposed areas of the face, cheeks, or chin. This benign neoplasm has a bimodal age distribution, primarily affecting females either in childhood or adulthood.13 Histologically, strands and nests of basaloid epithelial cells proliferate in a dense eosinophilic desmoplastic stroma. The basaloid islands are narrow and cordlike with growth parallel to the surface epidermis and do not dive deeply into the deep dermis or subcutis. Ductal differentiation with associated secretions typically is not seen in DTE.1 Calcifications and foreign body granulomatous infiltrates may be present. Merkel cells also are present in this tumor and may be highlighted by immunohistochemistry with cytokeratin 20.14 Rarely, desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas may transform into trichoblastic carcinomas. Treatment may consist of surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

Morpheaform BCC also is included in the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnosis of infiltrative basaloid neoplasms. It is one of the more aggressive variants of BCC. The use of immunohistochemical staining may aid in differentiating between these sclerosing adnexal neoplasms.15 For example, pleckstrin homologylike domain family A member 1 (PHLDA1) is a stem cell marker that is heavily expressed in DTE as a specific follicular bulge marker but is not present in a morpheaform BCC. This highlights the follicular nature of DTEs at the molecular level. BerEP4 is a monoclonal antibody that serves as an epithelial marker for 2 glycopolypeptides: 34 and 39 kDa. This antibody may demonstrate positivity in morpheaform BCC but does not stain cells of interest in MAC.

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus clinically presents with erythematous and warty papules in a linear distribution following the Blaschko lines. The papules often are reported to be intensely pruritic and usually are localized to one extremity.16 Although adultonset forms of ILVEN have been described,17 it most commonly is diagnosed in young children. Histologically, ILVEN consists of psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with alternating areas of parakeratosis and orthokeratosis with underlying agranulosis and hypergranulosis, respectively.18 The upper dermis contains a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Treatment with laser therapy and surgical excision has led to both symptomatic and clinical improvement of ILVEN.16

Plaque-type syringomas are a rare variant of syringomas that clinically may mimic other common inflammatory and neoplastic conditions. An adequate biopsy is imperative to differentiate between adnexal neoplasms, as a small superficial biopsy of a syringoma may demonstrate features observed in other malignant or locally aggressive neoplasms. In our patient, the small ducts lined by cuboidal epithelium with no cellular atypia and no deep dermal growth or perineural invasion allowed for the diagnosis of PTS. Therapeutic options were reviewed with our patient, including oral isotretinoin, laser therapy, and staged excision. Ultimately, our patient elected not to pursue treatment, and she is being monitored clinically for any changes in appearance or symptoms.

- Suwattee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma [published online November 12, 2007]. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Furue M, Hori Y, Nakabayashi Y. Clear-cell syringoma. association with diabetes mellitus. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:131-138.

- Kikuchi I, Idemori M, Okazaki M. Plaque type syringoma. J Dermatol. 1979;6:329-331.

- Kavala M, Can B, Zindanci I, et al. Vulvar pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:831-832.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Okuda H, Tei N, Shimizu K, et al. Chondroid syringoma of the scrotum. Int J Urol. 2008;15:944-945.

- Wallace JS, Bond JS, Seidel GD, et al. An important mimicker: plaquetype syringoma mistakenly diagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:810-812.

- Clark M, Duprey C, Sutton A, et al. Plaque-type syringoma masquerading as microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of the literature and description of a novel technique that emphasizes lesion architecture to help make the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:E98-E101.

- Wallace ML, Smoller BR. Progesterone receptor positivity supports hormonal control of syringomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:442-445.

- Mainitz M, Schmidt JB, Gebhart W. Response of multiple syringomas to isotretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1986;66:51-55.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Pujol RM, LeBoit PE, Su WP. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma with extensive sebaceous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:358-362.

- Rahman J, Tahir M, Arekemase H, et al. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: histopathologic and immunohistochemical criteria for differentiation of a rare benign hair follicle tumor from other cutaneous adnexal tumors. Cureus. 2020;12:E9703.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Sellheyer K, Nelson P, Kutzner H, et al. The immunohistochemical differential diagnosis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and morpheaform basal cell carcinoma using BerEP4 and stem cell markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:363-370.

- Gianfaldoni S, Tchernev G, Gianfaldoni R, et al. A case of “inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus” (ILVEN) treated with CO2 laser ablation. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5:454-457.

- Kawaguchi H, Takeuchi M, Ono H, et al. Adult onset of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus [published online October 27, 1999]. J Dermatol. 1999;26:599-602.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA, Prenshaw KL, et al. The psoriasiform reaction pattern. In: Patterson JW. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2021:99-120.

- Suwattee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma [published online November 12, 2007]. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Furue M, Hori Y, Nakabayashi Y. Clear-cell syringoma. association with diabetes mellitus. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:131-138.

- Kikuchi I, Idemori M, Okazaki M. Plaque type syringoma. J Dermatol. 1979;6:329-331.

- Kavala M, Can B, Zindanci I, et al. Vulvar pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:831-832.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Okuda H, Tei N, Shimizu K, et al. Chondroid syringoma of the scrotum. Int J Urol. 2008;15:944-945.

- Wallace JS, Bond JS, Seidel GD, et al. An important mimicker: plaquetype syringoma mistakenly diagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:810-812.

- Clark M, Duprey C, Sutton A, et al. Plaque-type syringoma masquerading as microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of the literature and description of a novel technique that emphasizes lesion architecture to help make the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:E98-E101.

- Wallace ML, Smoller BR. Progesterone receptor positivity supports hormonal control of syringomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:442-445.

- Mainitz M, Schmidt JB, Gebhart W. Response of multiple syringomas to isotretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1986;66:51-55.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Pujol RM, LeBoit PE, Su WP. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma with extensive sebaceous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:358-362.

- Rahman J, Tahir M, Arekemase H, et al. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: histopathologic and immunohistochemical criteria for differentiation of a rare benign hair follicle tumor from other cutaneous adnexal tumors. Cureus. 2020;12:E9703.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Sellheyer K, Nelson P, Kutzner H, et al. The immunohistochemical differential diagnosis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and morpheaform basal cell carcinoma using BerEP4 and stem cell markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:363-370.

- Gianfaldoni S, Tchernev G, Gianfaldoni R, et al. A case of “inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus” (ILVEN) treated with CO2 laser ablation. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5:454-457.

- Kawaguchi H, Takeuchi M, Ono H, et al. Adult onset of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus [published online October 27, 1999]. J Dermatol. 1999;26:599-602.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA, Prenshaw KL, et al. The psoriasiform reaction pattern. In: Patterson JW. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2021:99-120.

A 17-year-old adolescent girl presented with a solitary, 8-cm, pink plaque on the anterior aspect of the neck of 5 years’ duration. No similar skin findings were present elsewhere on the body. The rash was not painful or pruritic, and she denied prior trauma to the site. The patient previously had tried a salicylic acid bodywash as well as mupirocin cream 2% and mometasone ointment with no improvement. Her medical history was unremarkable, and she had no known allergies. There was no family history of a similar rash. Physical examination revealed no palpable subcutaneous lumps or masses and no lymphadenopathy of the head or neck. An incisional biopsy was performed.

Vascular Plaque in a Pregnant Patient With a History of Breast Cancer

The Diagnosis: Tufted Angioma

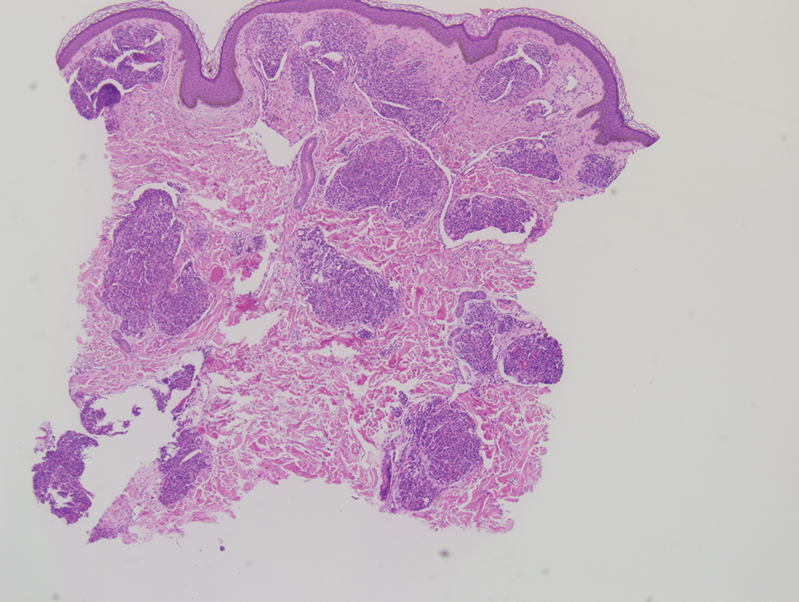

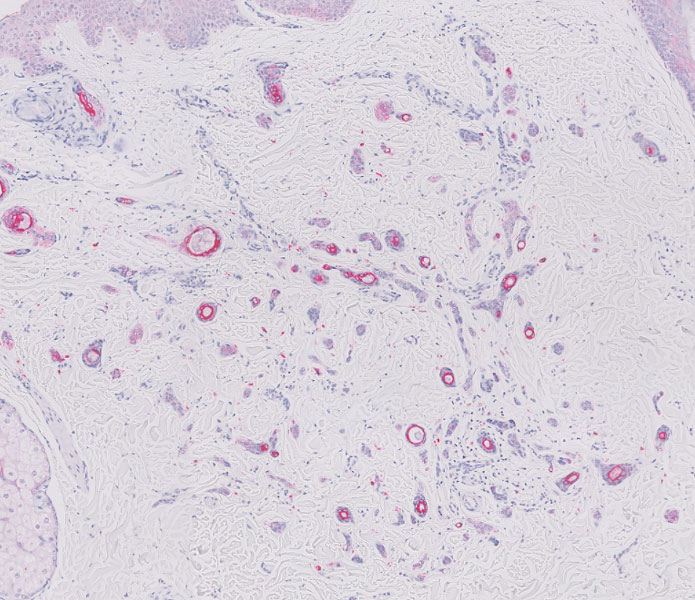

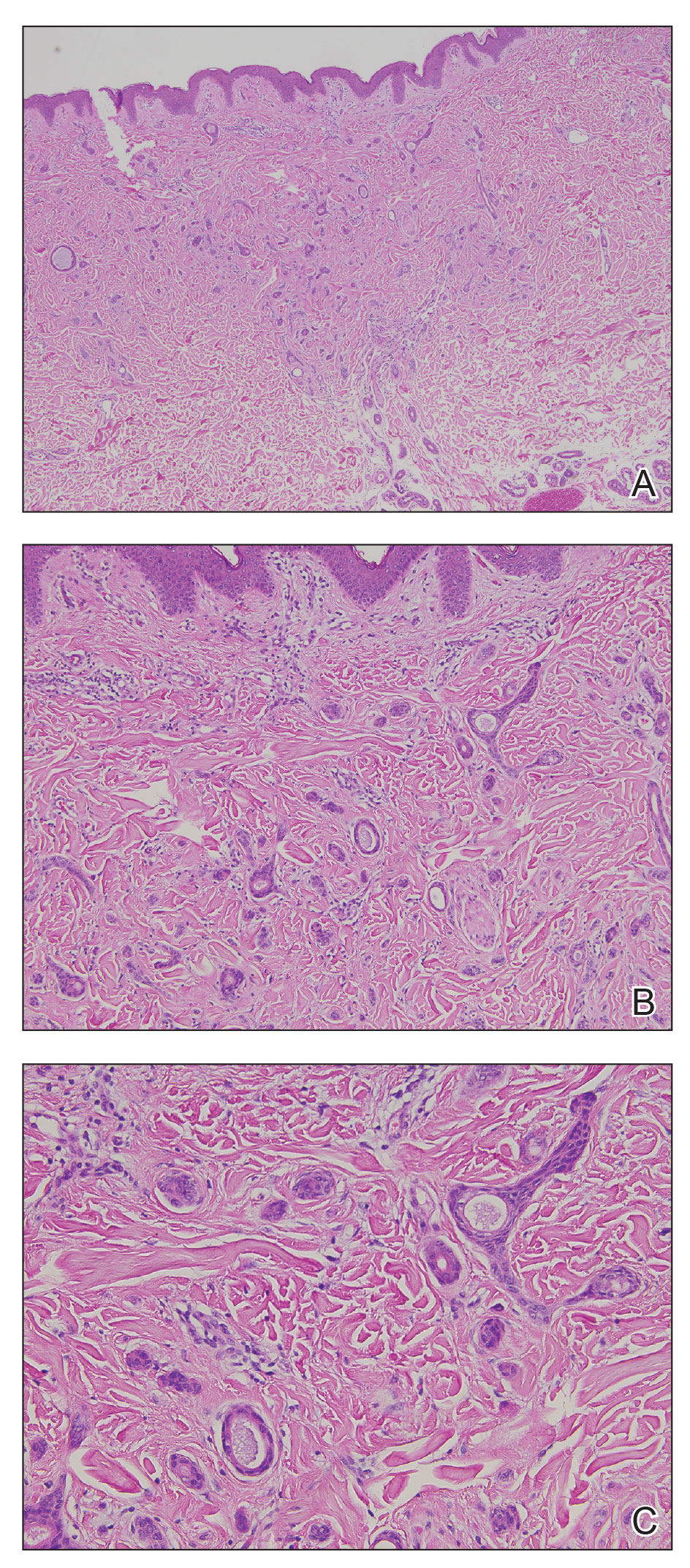

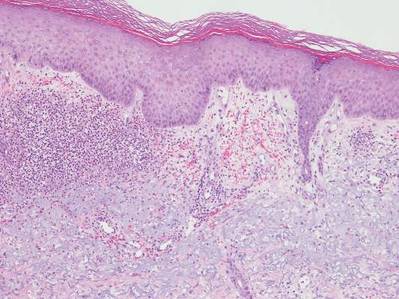

Histopathology revealed discrete lobules of closely packed capillaries with bland endothelial cells throughout the upper and lower dermis (Figure 1). The surrounding crescentlike vessels and lymphatics stained with D2-40 (Figure 2). These histologic findings were consistent with tufted angioma, and the patient elected for observation.

Tufted angiomas are benign vascular lesions named for the tufted appearance of capillaries on histology.1 They commonly present in children, with a lower incidence in adults and rare cases in pregnancy.2 Tufted angiomas typically present as solitary, slowly expanding, erythematous macules, plaques, or nodules on the neck or trunk ranging in size from less than 1 to 10 cm.2-4 They can be histologically distinguished from other vascular tumors, including aggressive malignant neoplasms.1

Tufted angiomas are identified by characteristic “cannon ball tufts” of capillaries in the dermis and subcutis at low power.3,5 Distinct cellular lobules may be found bulging into thin-walled vascular channels at the margins of the lobules in the dermis and subcutis (Figure 3).4 The lobules are formed by cells with spindle-shaped nuclei.6 Some mitotic figures may be present, but no cellular atypia is seen.2 The capillaries at the periphery appear as dilated semilunar vessels.4 Dilated lymphatics, which stain with D2-40, can be found at the periphery of the tufted capillaries and throughout the remaining dermis.3,4

Tufted angiomas may arise independently in adults but also have been associated with conditions such as pregnancy. Omori et al7 identified an acquired tufted angioma in pregnancy that was positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors. Reports of tufted angiomas in pregnancy vary; some are multiple lesions, some regress postpartum, and some undergo successful surgical treatment.3,5

Vascular lesions such as tufted angiomas specifically may appear in pregnancy due to a high-volume state with vasodilation and increased vascular proliferation. Although tumor angiogenesis has been linked to specific growth factors and cytokines, it has been hypothesized that the systemic hormones of pregnancy such as human chorionic gonadotropin, estradiol, and progesterone also shift the body to a more angiogenic state.8 In a study of cutaneous changes in pregnant women (N=905), 41% developed a vascular skin change, including spider veins, varicosities, hemangiomas, and granulomas.9 The most common vascular tumor in pregnancy is pyogenic granuloma. Pyogenic granulomas are small, solitary, friable papules that commonly are found on the hands, forearms, face, or in the mouth; histologically they demonstrate dilated capillaries in lobular structures accompanied by larger thick-walled vessels.3,10,11

Tufted angiomas may mimic a variety of other conditions. Epithelioid hemangioma, considered by some to be on the same morphologic spectrum as angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia, classically occurs in young adults on the head and in the neck region. It histologically demonstrates a lobular appearance at low power; however, these lobules are made up of vessels with histiocytoid to epithelioid endothelial cells surrounded by a prominent inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes and eosinophils.12

Kaposi sarcoma may appear on the neck but most often presents as macules and patches on the extremities that may form nodules with a rubbery consistency. In tufted angiomas, the cellular nodules with dilated channels at the margins bear a resemblance to Kaposi sarcoma or kaposiform hemangioendothelioma; however, in tufted angiomas the lobules are composed of bland spindle cells and slitlike vessels at the periphery.3,13,14 Tufted angiomas are negative for human herpesvirus 8 and typically do not have an associated inflammatory infiltrate with plasma cells.11,15

Moreover, it is important to differentiate tufted angioma from a cutaneous manifestation of an underlying malignancy, which has been described previously in cases of breast cancer.16,17 Our case illustrates a rare vascular tumor arising in the novel context of a pregnant patient with breast cancer. Distinguishing tufted angioma from other benign or malignant vascular tumors is necessary to avoid inappropriate therapeutic interventions.

- Jones EW, Orkin M. Tufted angioma (angioblastoma). a benign progressive angioma, not to be confused with Kaposi’s sarcoma or low-grade angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):214-225.

- Lee B, Chiu M, Soriano T, et al. Adult-onset tufted angioma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2006;78:341-345.

- Kim YK, Kim HJ, Lee KG. Acquired tufted angioma associated with pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:458-459.

- Feito-Rodriguez M, Sanchez-Orta A, De Lucas R, et al. Congenital tufted angioma: a multicenter retrospective study of 30 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:808-816.

- Pietroletti R, Leardi S, Simi M. Perianal acquired tufted angioma associated with pregnancy: case report. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:117-119.

- Osio A, Fraitag S, Hadj-Rabia S, et al. Clinical spectrum of tufted angiomas in childhood: a report of 13 cases and a review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:758-763.

- Omori M, Bito T, Nishigori C. Acquired tufted angioma in pregnancy showing expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:898-899.

- Boeldt DS, Bird IM. Vascular adaptation in pregnancy and endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia. J Endocrinol. 2017;232:R27-R44.

- Fernandes LB, Amaral W. Clinical study of skin changes in low and high risk pregnant women. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:822-826.

- Walker JL, Wang AR, Kroumpouzos G, et al. Cutaneous tumors in pregnancy. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:359-367.

- Sarwal P, Lapumnuaypol K. Pyogenic granuloma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Ortins-Pina A, Llamas-Velasco M, Turpin S, et al. FOSB immunoreactivity in endothelia of epithelioid hemangioma (angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia). J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:395-402.

- Arai E, Kuramochi A, Tsuchida T, et al. Usefulness of D2-40 immunohistochemistry for differentiation between kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:492-497.

- Grassi S, Carugno A, Vignini M, et al. Adult-onset tufted angiomas associated with an arteriovenous malformation in a renal transplant recipient: case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:162-165.

- Lyons LL, North PE, Mac-Moune Lai F, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: a study of 33 cases emphasizing its pathologic, immunophenotypic, and biologic uniqueness from juvenile hemangioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:559-568.

- Putra HP, Djawad K, Nurdin AR. Cutaneous lesions as the first manifestation of breast cancer: a rare case. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:383.

- Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:73-98.

The Diagnosis: Tufted Angioma

Histopathology revealed discrete lobules of closely packed capillaries with bland endothelial cells throughout the upper and lower dermis (Figure 1). The surrounding crescentlike vessels and lymphatics stained with D2-40 (Figure 2). These histologic findings were consistent with tufted angioma, and the patient elected for observation.

Tufted angiomas are benign vascular lesions named for the tufted appearance of capillaries on histology.1 They commonly present in children, with a lower incidence in adults and rare cases in pregnancy.2 Tufted angiomas typically present as solitary, slowly expanding, erythematous macules, plaques, or nodules on the neck or trunk ranging in size from less than 1 to 10 cm.2-4 They can be histologically distinguished from other vascular tumors, including aggressive malignant neoplasms.1

Tufted angiomas are identified by characteristic “cannon ball tufts” of capillaries in the dermis and subcutis at low power.3,5 Distinct cellular lobules may be found bulging into thin-walled vascular channels at the margins of the lobules in the dermis and subcutis (Figure 3).4 The lobules are formed by cells with spindle-shaped nuclei.6 Some mitotic figures may be present, but no cellular atypia is seen.2 The capillaries at the periphery appear as dilated semilunar vessels.4 Dilated lymphatics, which stain with D2-40, can be found at the periphery of the tufted capillaries and throughout the remaining dermis.3,4

Tufted angiomas may arise independently in adults but also have been associated with conditions such as pregnancy. Omori et al7 identified an acquired tufted angioma in pregnancy that was positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors. Reports of tufted angiomas in pregnancy vary; some are multiple lesions, some regress postpartum, and some undergo successful surgical treatment.3,5

Vascular lesions such as tufted angiomas specifically may appear in pregnancy due to a high-volume state with vasodilation and increased vascular proliferation. Although tumor angiogenesis has been linked to specific growth factors and cytokines, it has been hypothesized that the systemic hormones of pregnancy such as human chorionic gonadotropin, estradiol, and progesterone also shift the body to a more angiogenic state.8 In a study of cutaneous changes in pregnant women (N=905), 41% developed a vascular skin change, including spider veins, varicosities, hemangiomas, and granulomas.9 The most common vascular tumor in pregnancy is pyogenic granuloma. Pyogenic granulomas are small, solitary, friable papules that commonly are found on the hands, forearms, face, or in the mouth; histologically they demonstrate dilated capillaries in lobular structures accompanied by larger thick-walled vessels.3,10,11

Tufted angiomas may mimic a variety of other conditions. Epithelioid hemangioma, considered by some to be on the same morphologic spectrum as angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia, classically occurs in young adults on the head and in the neck region. It histologically demonstrates a lobular appearance at low power; however, these lobules are made up of vessels with histiocytoid to epithelioid endothelial cells surrounded by a prominent inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes and eosinophils.12

Kaposi sarcoma may appear on the neck but most often presents as macules and patches on the extremities that may form nodules with a rubbery consistency. In tufted angiomas, the cellular nodules with dilated channels at the margins bear a resemblance to Kaposi sarcoma or kaposiform hemangioendothelioma; however, in tufted angiomas the lobules are composed of bland spindle cells and slitlike vessels at the periphery.3,13,14 Tufted angiomas are negative for human herpesvirus 8 and typically do not have an associated inflammatory infiltrate with plasma cells.11,15

Moreover, it is important to differentiate tufted angioma from a cutaneous manifestation of an underlying malignancy, which has been described previously in cases of breast cancer.16,17 Our case illustrates a rare vascular tumor arising in the novel context of a pregnant patient with breast cancer. Distinguishing tufted angioma from other benign or malignant vascular tumors is necessary to avoid inappropriate therapeutic interventions.

The Diagnosis: Tufted Angioma

Histopathology revealed discrete lobules of closely packed capillaries with bland endothelial cells throughout the upper and lower dermis (Figure 1). The surrounding crescentlike vessels and lymphatics stained with D2-40 (Figure 2). These histologic findings were consistent with tufted angioma, and the patient elected for observation.

Tufted angiomas are benign vascular lesions named for the tufted appearance of capillaries on histology.1 They commonly present in children, with a lower incidence in adults and rare cases in pregnancy.2 Tufted angiomas typically present as solitary, slowly expanding, erythematous macules, plaques, or nodules on the neck or trunk ranging in size from less than 1 to 10 cm.2-4 They can be histologically distinguished from other vascular tumors, including aggressive malignant neoplasms.1

Tufted angiomas are identified by characteristic “cannon ball tufts” of capillaries in the dermis and subcutis at low power.3,5 Distinct cellular lobules may be found bulging into thin-walled vascular channels at the margins of the lobules in the dermis and subcutis (Figure 3).4 The lobules are formed by cells with spindle-shaped nuclei.6 Some mitotic figures may be present, but no cellular atypia is seen.2 The capillaries at the periphery appear as dilated semilunar vessels.4 Dilated lymphatics, which stain with D2-40, can be found at the periphery of the tufted capillaries and throughout the remaining dermis.3,4

Tufted angiomas may arise independently in adults but also have been associated with conditions such as pregnancy. Omori et al7 identified an acquired tufted angioma in pregnancy that was positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors. Reports of tufted angiomas in pregnancy vary; some are multiple lesions, some regress postpartum, and some undergo successful surgical treatment.3,5

Vascular lesions such as tufted angiomas specifically may appear in pregnancy due to a high-volume state with vasodilation and increased vascular proliferation. Although tumor angiogenesis has been linked to specific growth factors and cytokines, it has been hypothesized that the systemic hormones of pregnancy such as human chorionic gonadotropin, estradiol, and progesterone also shift the body to a more angiogenic state.8 In a study of cutaneous changes in pregnant women (N=905), 41% developed a vascular skin change, including spider veins, varicosities, hemangiomas, and granulomas.9 The most common vascular tumor in pregnancy is pyogenic granuloma. Pyogenic granulomas are small, solitary, friable papules that commonly are found on the hands, forearms, face, or in the mouth; histologically they demonstrate dilated capillaries in lobular structures accompanied by larger thick-walled vessels.3,10,11

Tufted angiomas may mimic a variety of other conditions. Epithelioid hemangioma, considered by some to be on the same morphologic spectrum as angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia, classically occurs in young adults on the head and in the neck region. It histologically demonstrates a lobular appearance at low power; however, these lobules are made up of vessels with histiocytoid to epithelioid endothelial cells surrounded by a prominent inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes and eosinophils.12

Kaposi sarcoma may appear on the neck but most often presents as macules and patches on the extremities that may form nodules with a rubbery consistency. In tufted angiomas, the cellular nodules with dilated channels at the margins bear a resemblance to Kaposi sarcoma or kaposiform hemangioendothelioma; however, in tufted angiomas the lobules are composed of bland spindle cells and slitlike vessels at the periphery.3,13,14 Tufted angiomas are negative for human herpesvirus 8 and typically do not have an associated inflammatory infiltrate with plasma cells.11,15

Moreover, it is important to differentiate tufted angioma from a cutaneous manifestation of an underlying malignancy, which has been described previously in cases of breast cancer.16,17 Our case illustrates a rare vascular tumor arising in the novel context of a pregnant patient with breast cancer. Distinguishing tufted angioma from other benign or malignant vascular tumors is necessary to avoid inappropriate therapeutic interventions.

- Jones EW, Orkin M. Tufted angioma (angioblastoma). a benign progressive angioma, not to be confused with Kaposi’s sarcoma or low-grade angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):214-225.

- Lee B, Chiu M, Soriano T, et al. Adult-onset tufted angioma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2006;78:341-345.

- Kim YK, Kim HJ, Lee KG. Acquired tufted angioma associated with pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:458-459.

- Feito-Rodriguez M, Sanchez-Orta A, De Lucas R, et al. Congenital tufted angioma: a multicenter retrospective study of 30 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:808-816.

- Pietroletti R, Leardi S, Simi M. Perianal acquired tufted angioma associated with pregnancy: case report. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:117-119.

- Osio A, Fraitag S, Hadj-Rabia S, et al. Clinical spectrum of tufted angiomas in childhood: a report of 13 cases and a review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:758-763.

- Omori M, Bito T, Nishigori C. Acquired tufted angioma in pregnancy showing expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:898-899.

- Boeldt DS, Bird IM. Vascular adaptation in pregnancy and endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia. J Endocrinol. 2017;232:R27-R44.

- Fernandes LB, Amaral W. Clinical study of skin changes in low and high risk pregnant women. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:822-826.

- Walker JL, Wang AR, Kroumpouzos G, et al. Cutaneous tumors in pregnancy. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:359-367.

- Sarwal P, Lapumnuaypol K. Pyogenic granuloma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Ortins-Pina A, Llamas-Velasco M, Turpin S, et al. FOSB immunoreactivity in endothelia of epithelioid hemangioma (angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia). J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:395-402.

- Arai E, Kuramochi A, Tsuchida T, et al. Usefulness of D2-40 immunohistochemistry for differentiation between kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:492-497.

- Grassi S, Carugno A, Vignini M, et al. Adult-onset tufted angiomas associated with an arteriovenous malformation in a renal transplant recipient: case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:162-165.

- Lyons LL, North PE, Mac-Moune Lai F, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: a study of 33 cases emphasizing its pathologic, immunophenotypic, and biologic uniqueness from juvenile hemangioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:559-568.

- Putra HP, Djawad K, Nurdin AR. Cutaneous lesions as the first manifestation of breast cancer: a rare case. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:383.

- Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:73-98.

- Jones EW, Orkin M. Tufted angioma (angioblastoma). a benign progressive angioma, not to be confused with Kaposi’s sarcoma or low-grade angiosarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):214-225.

- Lee B, Chiu M, Soriano T, et al. Adult-onset tufted angioma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2006;78:341-345.

- Kim YK, Kim HJ, Lee KG. Acquired tufted angioma associated with pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:458-459.

- Feito-Rodriguez M, Sanchez-Orta A, De Lucas R, et al. Congenital tufted angioma: a multicenter retrospective study of 30 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:808-816.

- Pietroletti R, Leardi S, Simi M. Perianal acquired tufted angioma associated with pregnancy: case report. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:117-119.

- Osio A, Fraitag S, Hadj-Rabia S, et al. Clinical spectrum of tufted angiomas in childhood: a report of 13 cases and a review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:758-763.

- Omori M, Bito T, Nishigori C. Acquired tufted angioma in pregnancy showing expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:898-899.

- Boeldt DS, Bird IM. Vascular adaptation in pregnancy and endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia. J Endocrinol. 2017;232:R27-R44.

- Fernandes LB, Amaral W. Clinical study of skin changes in low and high risk pregnant women. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:822-826.

- Walker JL, Wang AR, Kroumpouzos G, et al. Cutaneous tumors in pregnancy. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:359-367.

- Sarwal P, Lapumnuaypol K. Pyogenic granuloma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Ortins-Pina A, Llamas-Velasco M, Turpin S, et al. FOSB immunoreactivity in endothelia of epithelioid hemangioma (angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia). J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:395-402.

- Arai E, Kuramochi A, Tsuchida T, et al. Usefulness of D2-40 immunohistochemistry for differentiation between kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:492-497.

- Grassi S, Carugno A, Vignini M, et al. Adult-onset tufted angiomas associated with an arteriovenous malformation in a renal transplant recipient: case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:162-165.

- Lyons LL, North PE, Mac-Moune Lai F, et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: a study of 33 cases emphasizing its pathologic, immunophenotypic, and biologic uniqueness from juvenile hemangioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:559-568.

- Putra HP, Djawad K, Nurdin AR. Cutaneous lesions as the first manifestation of breast cancer: a rare case. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:383.

- Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:73-98.

A 31-year-old woman at 34 weeks’ gestation presented with skin discoloration of the anterior neck of 7 months’ duration. Her pregnancy had been complicated by a diagnosis of invasive papillary carcinoma of the breast with unilateral complete mastectomy and negative sentinel lymph node biopsy in the first trimester. The lesion was tender, darkening, and rapidly enlarging. Physical examination demonstrated a linear, violaceous, vascular, and indurated plaque with microvesiculation that was 3.5 cm in width. She had no history of blistering sunburns, frequent UV exposure, or skin cancer.

Itchy Papules and Plaques on the Dorsal Hands

The Diagnosis: Neutrophilic Dermatosis of the Dorsal Hands

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH) is considered to be an uncommon localized variant of Sweet syndrome (SS). The term pustular vasculitis originally was used to describe this condition by Strutton et al1 in 1995 due to the presence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histology. In 2000, Galaria et al2 suggested this eruption was a localized variant of SS based on clinical presentations that demonstrated associated fever and lack of necrotizing vasculitis and proposed the term neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands to describe the condition. Cases of similar cutaneous eruptions on the hands associated with fever, leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and leukocytoclasis have since been reported.3-5 Some authors have concluded that these eruptions, previously termed atypical pyoderma gangrenosum and pustular vasculitis of the hands, represent a single disease entity and should be designated as NDDH.3,4

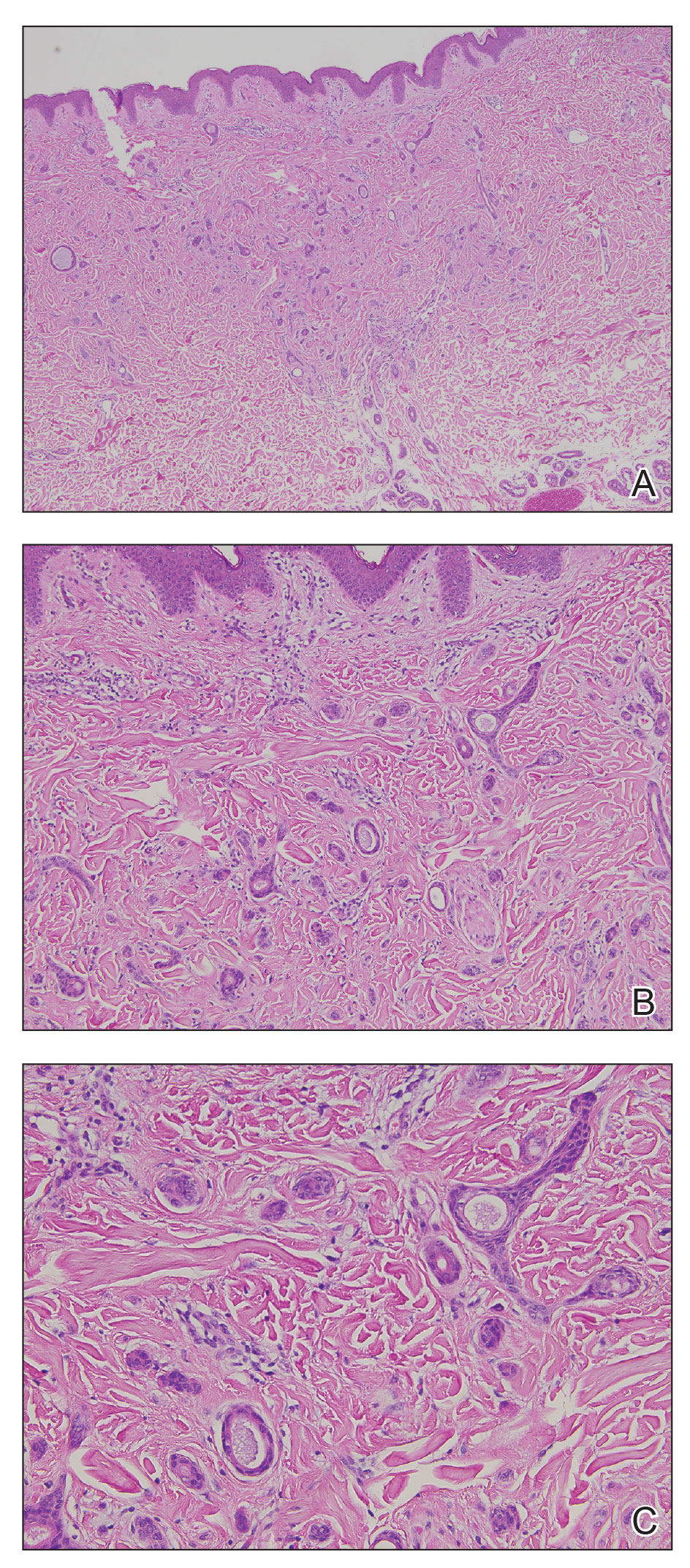

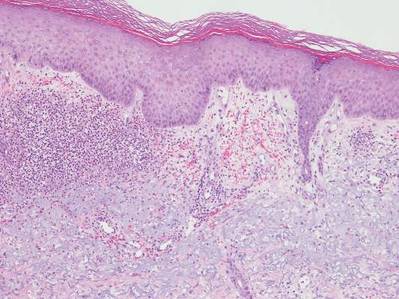

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands characteristically presents with hemorrhagic pustular ulcerations limited to or predominantly located on the dorsal hands, as seen in our patient. Histopathologically, NDDH demonstrates a neutrophil-predominant infiltrate of the upper dermis and marked papillary dermal edema; a punch biopsy specimen from our patient was consistent with these features (Figure). Two punch biopsies were performed and were negative for fungus and acid-fast bacteria and positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Vasculitis, if present, is more commonly seen in eruptions of longer duration (ie, months to years) and is thought to be secondary to the dense neutrophilic infiltrate and not a primary vasculitis.3,6,7 Similar to classic SS, NDDH is inherently responsive to corticosteroid therapy. Successful treatment also has been reported with dapsone, colchicine, sulfapyridine, potassium iodide, intralesional and topical corticosteroids, and topical tacrolimus.2-8 Oral minocycline has shown variable results.3,4

Numerous case series have demonstrated that a majority of cases of NDDH are associated with hematologic or solid organ malignancies, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), inflammatory bowel disease, or other underlying systemic diseases.3,5,9 It is important for dermatologists to recognize NDDH, distinguish it from localized infection, and perform the appropriate workup (eg, basic laboratory tests [complete blood count, complete metabolic panel], age-appropriate malignancy screening, colonoscopy, bone marrow biopsy) to exclude associated systemic diseases.

Our patient demonstrated characteristic clinical and histopathologic findings of NDDH in association with early MDS and possible common bile duct (CBD) malignancy. The lesions showed a rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy. The initial differential diagnoses included NDDH or other neutrophilic dermatosis, phototoxic drug eruption, and atypical mycobacterial or fungal infection (cultures were negative in our patient). Physical examination and histopathologic findings along with the patient’s clinical course and rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy supported the diagnosis of NDDH. Our patient’s multiple comorbidities, including macrocytic anemia, MDS, and potential CBD malignancy, presented a therapeutic challenge. Oral dapsone, an ideal steroid-sparing agent for neutrophilic dermatoses including NDDH, was avoided given its associated hematologic side effects including hemolysis, methemoglobinemia, and possible agranulocytosis. To date, the patient has not received any further treatment for MDS or the CBD mass and continues regular follow-up with hematology, gastroenterology, and dermatology.

This case highlights the importance of including NDDH in the differential diagnosis of papules and plaques on the hands, especially in patients with known malignancies, and emphasizes the association of neutrophilic dermatoses with malignancy and systemic disease.

- Strutton G, Weedon D, Robertson I. Pustular vasculitis of the hands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:192-198.

- Galaria NA, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Kligman D, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: pustular vasculitis revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:870-874.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM. Neutrophilic dermatosis (pustular vasculitis) of the dorsal hands. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:361-365.

- Weening RH, Bruce AJ, McEvoy MT, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: four new cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:95-102.

- Malone JC, Slone SP, Wills-Frank LA, et al. Vascular inflammation (vasculitis) in Sweet syndrome: a clinicopathologic study of 28 biopsy specimens from 21 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:345-349.

- Cohen PR. Skin lesions of Sweet syndrome and its dorsal hand variant contain vasculitis: an oxymoron or an epiphenomenon? Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:400-403.

- Del Pozo J, Sacristán F, Martínez W, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: presentation of eight cases and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2007;34:243-247.

- Callen JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:409-419.

The Diagnosis: Neutrophilic Dermatosis of the Dorsal Hands

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH) is considered to be an uncommon localized variant of Sweet syndrome (SS). The term pustular vasculitis originally was used to describe this condition by Strutton et al1 in 1995 due to the presence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histology. In 2000, Galaria et al2 suggested this eruption was a localized variant of SS based on clinical presentations that demonstrated associated fever and lack of necrotizing vasculitis and proposed the term neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands to describe the condition. Cases of similar cutaneous eruptions on the hands associated with fever, leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and leukocytoclasis have since been reported.3-5 Some authors have concluded that these eruptions, previously termed atypical pyoderma gangrenosum and pustular vasculitis of the hands, represent a single disease entity and should be designated as NDDH.3,4

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands characteristically presents with hemorrhagic pustular ulcerations limited to or predominantly located on the dorsal hands, as seen in our patient. Histopathologically, NDDH demonstrates a neutrophil-predominant infiltrate of the upper dermis and marked papillary dermal edema; a punch biopsy specimen from our patient was consistent with these features (Figure). Two punch biopsies were performed and were negative for fungus and acid-fast bacteria and positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Vasculitis, if present, is more commonly seen in eruptions of longer duration (ie, months to years) and is thought to be secondary to the dense neutrophilic infiltrate and not a primary vasculitis.3,6,7 Similar to classic SS, NDDH is inherently responsive to corticosteroid therapy. Successful treatment also has been reported with dapsone, colchicine, sulfapyridine, potassium iodide, intralesional and topical corticosteroids, and topical tacrolimus.2-8 Oral minocycline has shown variable results.3,4

Numerous case series have demonstrated that a majority of cases of NDDH are associated with hematologic or solid organ malignancies, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), inflammatory bowel disease, or other underlying systemic diseases.3,5,9 It is important for dermatologists to recognize NDDH, distinguish it from localized infection, and perform the appropriate workup (eg, basic laboratory tests [complete blood count, complete metabolic panel], age-appropriate malignancy screening, colonoscopy, bone marrow biopsy) to exclude associated systemic diseases.

Our patient demonstrated characteristic clinical and histopathologic findings of NDDH in association with early MDS and possible common bile duct (CBD) malignancy. The lesions showed a rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy. The initial differential diagnoses included NDDH or other neutrophilic dermatosis, phototoxic drug eruption, and atypical mycobacterial or fungal infection (cultures were negative in our patient). Physical examination and histopathologic findings along with the patient’s clinical course and rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy supported the diagnosis of NDDH. Our patient’s multiple comorbidities, including macrocytic anemia, MDS, and potential CBD malignancy, presented a therapeutic challenge. Oral dapsone, an ideal steroid-sparing agent for neutrophilic dermatoses including NDDH, was avoided given its associated hematologic side effects including hemolysis, methemoglobinemia, and possible agranulocytosis. To date, the patient has not received any further treatment for MDS or the CBD mass and continues regular follow-up with hematology, gastroenterology, and dermatology.

This case highlights the importance of including NDDH in the differential diagnosis of papules and plaques on the hands, especially in patients with known malignancies, and emphasizes the association of neutrophilic dermatoses with malignancy and systemic disease.

The Diagnosis: Neutrophilic Dermatosis of the Dorsal Hands

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH) is considered to be an uncommon localized variant of Sweet syndrome (SS). The term pustular vasculitis originally was used to describe this condition by Strutton et al1 in 1995 due to the presence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histology. In 2000, Galaria et al2 suggested this eruption was a localized variant of SS based on clinical presentations that demonstrated associated fever and lack of necrotizing vasculitis and proposed the term neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands to describe the condition. Cases of similar cutaneous eruptions on the hands associated with fever, leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and leukocytoclasis have since been reported.3-5 Some authors have concluded that these eruptions, previously termed atypical pyoderma gangrenosum and pustular vasculitis of the hands, represent a single disease entity and should be designated as NDDH.3,4

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands characteristically presents with hemorrhagic pustular ulcerations limited to or predominantly located on the dorsal hands, as seen in our patient. Histopathologically, NDDH demonstrates a neutrophil-predominant infiltrate of the upper dermis and marked papillary dermal edema; a punch biopsy specimen from our patient was consistent with these features (Figure). Two punch biopsies were performed and were negative for fungus and acid-fast bacteria and positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Vasculitis, if present, is more commonly seen in eruptions of longer duration (ie, months to years) and is thought to be secondary to the dense neutrophilic infiltrate and not a primary vasculitis.3,6,7 Similar to classic SS, NDDH is inherently responsive to corticosteroid therapy. Successful treatment also has been reported with dapsone, colchicine, sulfapyridine, potassium iodide, intralesional and topical corticosteroids, and topical tacrolimus.2-8 Oral minocycline has shown variable results.3,4

Numerous case series have demonstrated that a majority of cases of NDDH are associated with hematologic or solid organ malignancies, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), inflammatory bowel disease, or other underlying systemic diseases.3,5,9 It is important for dermatologists to recognize NDDH, distinguish it from localized infection, and perform the appropriate workup (eg, basic laboratory tests [complete blood count, complete metabolic panel], age-appropriate malignancy screening, colonoscopy, bone marrow biopsy) to exclude associated systemic diseases.

Our patient demonstrated characteristic clinical and histopathologic findings of NDDH in association with early MDS and possible common bile duct (CBD) malignancy. The lesions showed a rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy. The initial differential diagnoses included NDDH or other neutrophilic dermatosis, phototoxic drug eruption, and atypical mycobacterial or fungal infection (cultures were negative in our patient). Physical examination and histopathologic findings along with the patient’s clinical course and rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy supported the diagnosis of NDDH. Our patient’s multiple comorbidities, including macrocytic anemia, MDS, and potential CBD malignancy, presented a therapeutic challenge. Oral dapsone, an ideal steroid-sparing agent for neutrophilic dermatoses including NDDH, was avoided given its associated hematologic side effects including hemolysis, methemoglobinemia, and possible agranulocytosis. To date, the patient has not received any further treatment for MDS or the CBD mass and continues regular follow-up with hematology, gastroenterology, and dermatology.

This case highlights the importance of including NDDH in the differential diagnosis of papules and plaques on the hands, especially in patients with known malignancies, and emphasizes the association of neutrophilic dermatoses with malignancy and systemic disease.

- Strutton G, Weedon D, Robertson I. Pustular vasculitis of the hands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:192-198.

- Galaria NA, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Kligman D, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: pustular vasculitis revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:870-874.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM. Neutrophilic dermatosis (pustular vasculitis) of the dorsal hands. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:361-365.

- Weening RH, Bruce AJ, McEvoy MT, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: four new cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:95-102.

- Malone JC, Slone SP, Wills-Frank LA, et al. Vascular inflammation (vasculitis) in Sweet syndrome: a clinicopathologic study of 28 biopsy specimens from 21 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:345-349.

- Cohen PR. Skin lesions of Sweet syndrome and its dorsal hand variant contain vasculitis: an oxymoron or an epiphenomenon? Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:400-403.

- Del Pozo J, Sacristán F, Martínez W, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: presentation of eight cases and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2007;34:243-247.

- Callen JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:409-419.

- Strutton G, Weedon D, Robertson I. Pustular vasculitis of the hands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:192-198.

- Galaria NA, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Kligman D, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: pustular vasculitis revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:870-874.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM. Neutrophilic dermatosis (pustular vasculitis) of the dorsal hands. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:361-365.

- Weening RH, Bruce AJ, McEvoy MT, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: four new cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:95-102.

- Malone JC, Slone SP, Wills-Frank LA, et al. Vascular inflammation (vasculitis) in Sweet syndrome: a clinicopathologic study of 28 biopsy specimens from 21 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:345-349.

- Cohen PR. Skin lesions of Sweet syndrome and its dorsal hand variant contain vasculitis: an oxymoron or an epiphenomenon? Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:400-403.

- Del Pozo J, Sacristán F, Martínez W, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: presentation of eight cases and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2007;34:243-247.

- Callen JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:409-419.

A 69-year-old man presented with tender, itchy papules and plaques on the bilateral dorsal hands of 2 months’ duration. The plaques had started as small papules that gradually enlarged and then became ulcerated. The patient denied prior trauma or constitutional symptoms. Laboratory testing revealed macrocytic anemia, thrombocytosis, and hypoalbuminemia. A complete blood count and complete metabolic panel were otherwise unremarkable. A recent bone marrow biopsy for macrocytic anemia performed prior to the current presentation suggested early myelodysplastic syndrome, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography revealed a large mass in the common bile duct that was suspicious for malignancy. Two punch biopsies were performed and were negative for fungus and acid-fast bacteria and positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Treatment with topical clobetasol 0.05% twice daily was initiated with complete healing of the plaques on the hands after 2 weeks of use; however, the patient continued to develop new ulcerated papulonodules distally.