User login

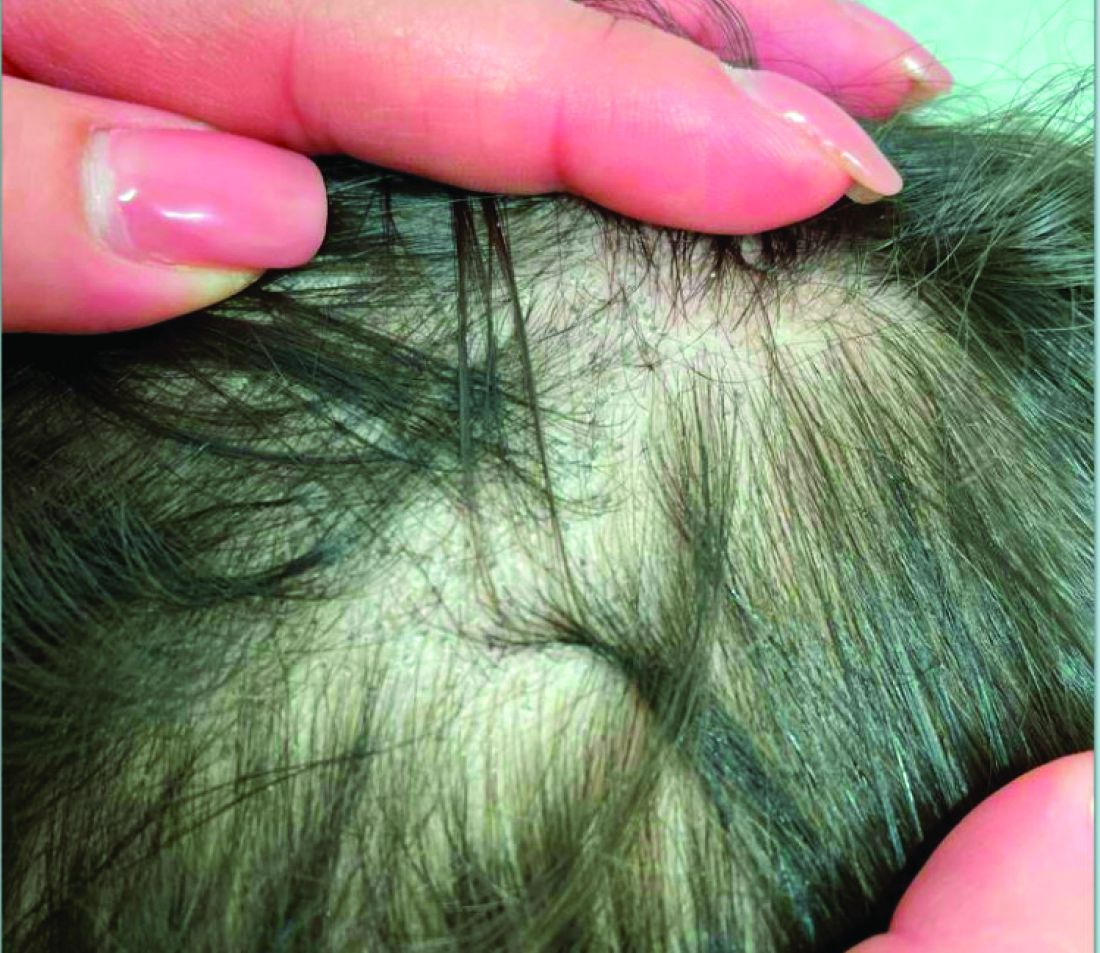

A 7-Year-Old Boy Presents With Dark Spots on His Scalp and Areas of Poor Hair Growth

Given the trichoscopic findings, scrapings from the scaly areas were taken and revealed hyphae, confirming the diagnosis of tinea capitis. A fungal culture identified Trichophyton tonsurans as the causative organism.

Tinea capitis is the most common dermatophyte infection in children. Risk factors include participation in close-contact sports like wrestling or jiu-jitsu, attendance at daycare for younger children, African American hair care practices, pet ownership (particularly cats and rodents), and living in overcrowded conditions.

Diagnosis of tinea capitis requires a thorough clinical history to identify potential risk factors. On physical examination, patchy hair loss with associated scaling should raise suspicion for tinea capitis. Inflammatory signs, such as pustules and swelling, may suggest the presence of a kerion, further supporting the diagnosis. Although some practitioners use Wood’s lamp to help with diagnosis, its utility is limited. It detects fluorescence in Microsporum species (exothrix infections) but not in Trichophyton species (endothrix infections).

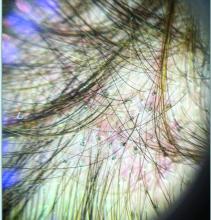

Trichoscopy can be a valuable tool when inflammation is minimal, and only hair loss and scaling are observed. Trichoscopic findings suggestive of tinea capitis include comma hairs, corkscrew hairs (as seen in this patient), Morse code-like hairs, zigzag hairs, bent hairs, block hairs, and i-hairs. Other common, though not characteristic, findings include broken hairs, black dots, perifollicular scaling, and diffuse scaling.

KOH (potassium hydroxide) analysis is another useful method for detecting fungal elements, though it does not identify the specific fungus and may not be available in all clinical settings. Mycologic culture remains the gold standard for diagnosing tinea capitis, though results can take 3-4 weeks. Newer diagnostic techniques, such as PCR analysis and MALDI-TOF/MS, offer more rapid identification of the causative organism.

The differential diagnosis includes:

- Seborrheic dermatitis, which presents with greasy, yellowish scales and itching, with trichoscopy showing twisted, coiled hairs and yellowish scaling.

- Psoriasis, which can mimic tinea capitis but presents with well-demarcated red plaques and silvery-white scales. Trichoscopy shows red dots and uniform scaling.

- Alopecia areata, which causes patchy hair loss without inflammation or scaling, with trichoscopic findings of exclamation mark hairs, black dots, and yellow dots.

- Trichotillomania, a hair-pulling disorder, which results in irregular patches of hair loss. Trichoscopy shows broken hairs of varying lengths, V-sign hairs, and flame-shaped residues at follicular openings.

Treatment of tinea capitis requires systemic antifungals and topical agents to prevent fungal spore spread. Several treatment guidelines are available from different institutions. Griseofulvin (FDA-approved for patients > 2 years of age) has been widely used, particularly for Microsporum canis infections. However, due to limited availability in many countries, terbinafine (FDA-approved for patients > 4 years of age) is now commonly used as first-line therapy, especially for Trichophyton species. Treatment typically lasts 4-6 weeks, and post-treatment cultures may be recommended to confirm mycologic cure.

Concerns about drug resistance have emerged, particularly for terbinafine-resistant dermatophytes linked to mutations in the squalene epoxidase enzyme. Resistance may be driven by limited antifungal availability and poor adherence to prolonged treatment regimens. While fluconazole and itraconazole are used off-label, growing evidence supports their effectiveness, although one large trial showed suboptimal cure rates with fluconazole.

Though systemic antifungals are generally safe, hepatotoxicity remains a concern, especially in patients with hepatic conditions or other comorbidities. Lab monitoring is advised for patients on prolonged or multiple therapies, or for those with coexisting conditions. The decision to conduct lab monitoring should be discussed with parents, balancing the very low risk of hepatotoxicity in healthy children against their comfort level.

An alternative to systemic therapy is photodynamic therapy (PDT), which has been reported as successful in treating tinea capitis infections, particularly in cases of T. mentagrophytes and M. canis. However, large-scale trials are needed to confirm PDT’s efficacy and safety.

In conclusion, children presenting with hair loss, scaling, and associated dark spots on the scalp should be evaluated for fungal infection. While trichoscopy can aid in diagnosis, fungal culture remains the gold standard for confirmation.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Rudnicka L et al. Hair shafts in trichoscopy: clues for diagnosis of hair and scalp diseases. Dermatol Clin. 2013 Oct;31(4):695-708, x. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2013.06.007.

Gupta AK et al. An update on tinea capitis in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2024 Aug 7. doi: 10.1111/pde.15708.

Anna Waskiel-Burnat et al. Trichoscopy of tinea capitis: A systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020 Feb;10(1):43-52. doi: 10.1007/s13555-019-00350-1.

Given the trichoscopic findings, scrapings from the scaly areas were taken and revealed hyphae, confirming the diagnosis of tinea capitis. A fungal culture identified Trichophyton tonsurans as the causative organism.

Tinea capitis is the most common dermatophyte infection in children. Risk factors include participation in close-contact sports like wrestling or jiu-jitsu, attendance at daycare for younger children, African American hair care practices, pet ownership (particularly cats and rodents), and living in overcrowded conditions.

Diagnosis of tinea capitis requires a thorough clinical history to identify potential risk factors. On physical examination, patchy hair loss with associated scaling should raise suspicion for tinea capitis. Inflammatory signs, such as pustules and swelling, may suggest the presence of a kerion, further supporting the diagnosis. Although some practitioners use Wood’s lamp to help with diagnosis, its utility is limited. It detects fluorescence in Microsporum species (exothrix infections) but not in Trichophyton species (endothrix infections).

Trichoscopy can be a valuable tool when inflammation is minimal, and only hair loss and scaling are observed. Trichoscopic findings suggestive of tinea capitis include comma hairs, corkscrew hairs (as seen in this patient), Morse code-like hairs, zigzag hairs, bent hairs, block hairs, and i-hairs. Other common, though not characteristic, findings include broken hairs, black dots, perifollicular scaling, and diffuse scaling.

KOH (potassium hydroxide) analysis is another useful method for detecting fungal elements, though it does not identify the specific fungus and may not be available in all clinical settings. Mycologic culture remains the gold standard for diagnosing tinea capitis, though results can take 3-4 weeks. Newer diagnostic techniques, such as PCR analysis and MALDI-TOF/MS, offer more rapid identification of the causative organism.

The differential diagnosis includes:

- Seborrheic dermatitis, which presents with greasy, yellowish scales and itching, with trichoscopy showing twisted, coiled hairs and yellowish scaling.

- Psoriasis, which can mimic tinea capitis but presents with well-demarcated red plaques and silvery-white scales. Trichoscopy shows red dots and uniform scaling.

- Alopecia areata, which causes patchy hair loss without inflammation or scaling, with trichoscopic findings of exclamation mark hairs, black dots, and yellow dots.

- Trichotillomania, a hair-pulling disorder, which results in irregular patches of hair loss. Trichoscopy shows broken hairs of varying lengths, V-sign hairs, and flame-shaped residues at follicular openings.

Treatment of tinea capitis requires systemic antifungals and topical agents to prevent fungal spore spread. Several treatment guidelines are available from different institutions. Griseofulvin (FDA-approved for patients > 2 years of age) has been widely used, particularly for Microsporum canis infections. However, due to limited availability in many countries, terbinafine (FDA-approved for patients > 4 years of age) is now commonly used as first-line therapy, especially for Trichophyton species. Treatment typically lasts 4-6 weeks, and post-treatment cultures may be recommended to confirm mycologic cure.

Concerns about drug resistance have emerged, particularly for terbinafine-resistant dermatophytes linked to mutations in the squalene epoxidase enzyme. Resistance may be driven by limited antifungal availability and poor adherence to prolonged treatment regimens. While fluconazole and itraconazole are used off-label, growing evidence supports their effectiveness, although one large trial showed suboptimal cure rates with fluconazole.

Though systemic antifungals are generally safe, hepatotoxicity remains a concern, especially in patients with hepatic conditions or other comorbidities. Lab monitoring is advised for patients on prolonged or multiple therapies, or for those with coexisting conditions. The decision to conduct lab monitoring should be discussed with parents, balancing the very low risk of hepatotoxicity in healthy children against their comfort level.

An alternative to systemic therapy is photodynamic therapy (PDT), which has been reported as successful in treating tinea capitis infections, particularly in cases of T. mentagrophytes and M. canis. However, large-scale trials are needed to confirm PDT’s efficacy and safety.

In conclusion, children presenting with hair loss, scaling, and associated dark spots on the scalp should be evaluated for fungal infection. While trichoscopy can aid in diagnosis, fungal culture remains the gold standard for confirmation.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Rudnicka L et al. Hair shafts in trichoscopy: clues for diagnosis of hair and scalp diseases. Dermatol Clin. 2013 Oct;31(4):695-708, x. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2013.06.007.

Gupta AK et al. An update on tinea capitis in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2024 Aug 7. doi: 10.1111/pde.15708.

Anna Waskiel-Burnat et al. Trichoscopy of tinea capitis: A systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020 Feb;10(1):43-52. doi: 10.1007/s13555-019-00350-1.

Given the trichoscopic findings, scrapings from the scaly areas were taken and revealed hyphae, confirming the diagnosis of tinea capitis. A fungal culture identified Trichophyton tonsurans as the causative organism.

Tinea capitis is the most common dermatophyte infection in children. Risk factors include participation in close-contact sports like wrestling or jiu-jitsu, attendance at daycare for younger children, African American hair care practices, pet ownership (particularly cats and rodents), and living in overcrowded conditions.

Diagnosis of tinea capitis requires a thorough clinical history to identify potential risk factors. On physical examination, patchy hair loss with associated scaling should raise suspicion for tinea capitis. Inflammatory signs, such as pustules and swelling, may suggest the presence of a kerion, further supporting the diagnosis. Although some practitioners use Wood’s lamp to help with diagnosis, its utility is limited. It detects fluorescence in Microsporum species (exothrix infections) but not in Trichophyton species (endothrix infections).

Trichoscopy can be a valuable tool when inflammation is minimal, and only hair loss and scaling are observed. Trichoscopic findings suggestive of tinea capitis include comma hairs, corkscrew hairs (as seen in this patient), Morse code-like hairs, zigzag hairs, bent hairs, block hairs, and i-hairs. Other common, though not characteristic, findings include broken hairs, black dots, perifollicular scaling, and diffuse scaling.

KOH (potassium hydroxide) analysis is another useful method for detecting fungal elements, though it does not identify the specific fungus and may not be available in all clinical settings. Mycologic culture remains the gold standard for diagnosing tinea capitis, though results can take 3-4 weeks. Newer diagnostic techniques, such as PCR analysis and MALDI-TOF/MS, offer more rapid identification of the causative organism.

The differential diagnosis includes:

- Seborrheic dermatitis, which presents with greasy, yellowish scales and itching, with trichoscopy showing twisted, coiled hairs and yellowish scaling.

- Psoriasis, which can mimic tinea capitis but presents with well-demarcated red plaques and silvery-white scales. Trichoscopy shows red dots and uniform scaling.

- Alopecia areata, which causes patchy hair loss without inflammation or scaling, with trichoscopic findings of exclamation mark hairs, black dots, and yellow dots.

- Trichotillomania, a hair-pulling disorder, which results in irregular patches of hair loss. Trichoscopy shows broken hairs of varying lengths, V-sign hairs, and flame-shaped residues at follicular openings.

Treatment of tinea capitis requires systemic antifungals and topical agents to prevent fungal spore spread. Several treatment guidelines are available from different institutions. Griseofulvin (FDA-approved for patients > 2 years of age) has been widely used, particularly for Microsporum canis infections. However, due to limited availability in many countries, terbinafine (FDA-approved for patients > 4 years of age) is now commonly used as first-line therapy, especially for Trichophyton species. Treatment typically lasts 4-6 weeks, and post-treatment cultures may be recommended to confirm mycologic cure.

Concerns about drug resistance have emerged, particularly for terbinafine-resistant dermatophytes linked to mutations in the squalene epoxidase enzyme. Resistance may be driven by limited antifungal availability and poor adherence to prolonged treatment regimens. While fluconazole and itraconazole are used off-label, growing evidence supports their effectiveness, although one large trial showed suboptimal cure rates with fluconazole.

Though systemic antifungals are generally safe, hepatotoxicity remains a concern, especially in patients with hepatic conditions or other comorbidities. Lab monitoring is advised for patients on prolonged or multiple therapies, or for those with coexisting conditions. The decision to conduct lab monitoring should be discussed with parents, balancing the very low risk of hepatotoxicity in healthy children against their comfort level.

An alternative to systemic therapy is photodynamic therapy (PDT), which has been reported as successful in treating tinea capitis infections, particularly in cases of T. mentagrophytes and M. canis. However, large-scale trials are needed to confirm PDT’s efficacy and safety.

In conclusion, children presenting with hair loss, scaling, and associated dark spots on the scalp should be evaluated for fungal infection. While trichoscopy can aid in diagnosis, fungal culture remains the gold standard for confirmation.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Rudnicka L et al. Hair shafts in trichoscopy: clues for diagnosis of hair and scalp diseases. Dermatol Clin. 2013 Oct;31(4):695-708, x. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2013.06.007.

Gupta AK et al. An update on tinea capitis in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2024 Aug 7. doi: 10.1111/pde.15708.

Anna Waskiel-Burnat et al. Trichoscopy of tinea capitis: A systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020 Feb;10(1):43-52. doi: 10.1007/s13555-019-00350-1.

A 14-Year-Old Female Presents With a Growth Under Her Toenail

BY XOCHITL LONGSTAFF, BS; ANGELINA LABIB, MD; AND DAWN EICHENFIELD, MD, PHD

Diagnosis: Subungual bony exostosis

The patient was referred to orthopedics for further evaluation and ultimately underwent excisional surgery. At her most recent follow-up visit with orthopedic surgery, her new nail was observed to be growing well.

Subungual exostosis, also known as Dupuytren’s exostosis, is a benign osteocartilaginous tumor that classically presents as a bony growth at the dorsal aspect of the distal phalanx of the great toe, near the nail bed. The pathogenesis remains unclear, but suggested etiologies include prior trauma, infection, and hereditary abnormalities.1

Clinically, lesions can be painful and may be associated with skin ulceration. The location at the dorsal distal great toe is a key distinguishing feature. Physical exam reveals a firm, fixed nodule with a hyperkeratotic smooth surface.2

Radiographic evaluation, particularly with a lateral view, is often diagnostic. The classic radiographic finding in subungual exostosis is an osseous structure connected to the distal phalanx, with a hazy periphery representing a fibrocartilage cap.

Treatment involves complete marginal excision. The complications from surgical excision are minimal, with the most common being recurrence.3 However, the recurrence rate is also generally low, around 4%.1

Ms. Longstaff is currently completing a research year as a Pediatric Clinical Research Fellow at University of California San Diego (UCSD) Rady Children’s Hospital prior to finishing her final year at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Labib is the Post-Doctoral Pediatric Clinical Research Fellow at UCSD Rady Children’s Hospital. Dr. Eichenfield is a dermatologist at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and assistant clinical professor at UCSD.

References

1. Alabdullrahman LW et al. Osteochondroma. In: StatPearls [Internet]. 2024 Feb 26. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544296/#.

2. DaCambra MP et al. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 Apr;472(4):1251-9. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3345-4.

3. Womack ME et al. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2022 Mar 22;6(3):e21.00239. doi: 10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-21-00239.

BY XOCHITL LONGSTAFF, BS; ANGELINA LABIB, MD; AND DAWN EICHENFIELD, MD, PHD

Diagnosis: Subungual bony exostosis

The patient was referred to orthopedics for further evaluation and ultimately underwent excisional surgery. At her most recent follow-up visit with orthopedic surgery, her new nail was observed to be growing well.

Subungual exostosis, also known as Dupuytren’s exostosis, is a benign osteocartilaginous tumor that classically presents as a bony growth at the dorsal aspect of the distal phalanx of the great toe, near the nail bed. The pathogenesis remains unclear, but suggested etiologies include prior trauma, infection, and hereditary abnormalities.1

Clinically, lesions can be painful and may be associated with skin ulceration. The location at the dorsal distal great toe is a key distinguishing feature. Physical exam reveals a firm, fixed nodule with a hyperkeratotic smooth surface.2

Radiographic evaluation, particularly with a lateral view, is often diagnostic. The classic radiographic finding in subungual exostosis is an osseous structure connected to the distal phalanx, with a hazy periphery representing a fibrocartilage cap.

Treatment involves complete marginal excision. The complications from surgical excision are minimal, with the most common being recurrence.3 However, the recurrence rate is also generally low, around 4%.1

Ms. Longstaff is currently completing a research year as a Pediatric Clinical Research Fellow at University of California San Diego (UCSD) Rady Children’s Hospital prior to finishing her final year at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Labib is the Post-Doctoral Pediatric Clinical Research Fellow at UCSD Rady Children’s Hospital. Dr. Eichenfield is a dermatologist at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and assistant clinical professor at UCSD.

References

1. Alabdullrahman LW et al. Osteochondroma. In: StatPearls [Internet]. 2024 Feb 26. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544296/#.

2. DaCambra MP et al. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 Apr;472(4):1251-9. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3345-4.

3. Womack ME et al. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2022 Mar 22;6(3):e21.00239. doi: 10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-21-00239.

BY XOCHITL LONGSTAFF, BS; ANGELINA LABIB, MD; AND DAWN EICHENFIELD, MD, PHD

Diagnosis: Subungual bony exostosis

The patient was referred to orthopedics for further evaluation and ultimately underwent excisional surgery. At her most recent follow-up visit with orthopedic surgery, her new nail was observed to be growing well.

Subungual exostosis, also known as Dupuytren’s exostosis, is a benign osteocartilaginous tumor that classically presents as a bony growth at the dorsal aspect of the distal phalanx of the great toe, near the nail bed. The pathogenesis remains unclear, but suggested etiologies include prior trauma, infection, and hereditary abnormalities.1

Clinically, lesions can be painful and may be associated with skin ulceration. The location at the dorsal distal great toe is a key distinguishing feature. Physical exam reveals a firm, fixed nodule with a hyperkeratotic smooth surface.2

Radiographic evaluation, particularly with a lateral view, is often diagnostic. The classic radiographic finding in subungual exostosis is an osseous structure connected to the distal phalanx, with a hazy periphery representing a fibrocartilage cap.

Treatment involves complete marginal excision. The complications from surgical excision are minimal, with the most common being recurrence.3 However, the recurrence rate is also generally low, around 4%.1

Ms. Longstaff is currently completing a research year as a Pediatric Clinical Research Fellow at University of California San Diego (UCSD) Rady Children’s Hospital prior to finishing her final year at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Labib is the Post-Doctoral Pediatric Clinical Research Fellow at UCSD Rady Children’s Hospital. Dr. Eichenfield is a dermatologist at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and assistant clinical professor at UCSD.

References

1. Alabdullrahman LW et al. Osteochondroma. In: StatPearls [Internet]. 2024 Feb 26. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544296/#.

2. DaCambra MP et al. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 Apr;472(4):1251-9. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3345-4.

3. Womack ME et al. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2022 Mar 22;6(3):e21.00239. doi: 10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-21-00239.

A 14-year-old healthy female presents with a painful nodule under her great toenail. The nodule had been present for 2 months and there was no preceding trauma. Three days prior to presentation, her nail cracked and bled after bumping her toe. The toe is painful to palpation. Given the associated pain, the patient visited urgent care and was prescribed cephalexin and acetaminophen.

Physical examination reveals a skin-colored subungual nodule with hypertrophic tissue originating from the nail bed of the right great toe, but no thickening of the nail plate (Figures 1-3).

A 7-Month-Old Female Presented With Nail Changes

Given the clinical presentation and the absence of other systemic or dermatological findings, the diagnosis of chevron nails was made.

Discussion

The condition is characterized by transverse ridges on the nails that converge towards the center, forming a V or chevron shape. This condition was first described by Perry et al. and later by Shuster et al., who explained that the condition might result from axial growth of the nail with synchronous growth occurring from a chevron-shaped growing edge of the nail root. Alternatively, Shuster suggested that sequential growth, with localized variation in the nail production rate, could propagate a wave from the center of the nail to the edge.

The etiology of chevron nails is not well understood, but it is believed to result from temporary disruptions in the nail matrix, possibly related to minor illness or physiological stress during infancy.

In the case of our 7-month-old patient, the history of mild upper respiratory infections might have contributed to the development of chevron nails. However, the lack of other significant illness, skin involvement, or systemic findings supports the benign and self-limiting nature of this condition. Parents were reassured that chevron nails typically resolve on their own as the child grows and that no specific treatment is necessary.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of transverse nail changes in children includes other conditions such as trachyonychia, lichen planus, Darier disease, and pachyonychia congenita.

Trachyonychia, also known as “sandpaper nails,” trachyonychia is characterized by the roughening of the nail surface, giving it a dull and ridged appearance. The condition may affect all 20 nails and is often associated with underlying dermatological conditions such as lichen planus or alopecia areata. Unlike chevron nails, trachyonychia presents with more diffuse nail changes and does not typically feature the distinct V-shaped ridging seen in this patient.

Lichen planus is an inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, mucous membranes, and nails. Nail involvement in lichen planus can lead to longitudinal ridging, thinning, and sometimes even complete nail loss. The absence of other characteristic features of lichen planus, such as violaceous papules on the skin or white lacy patterns on mucous membranes (Wickham striae), makes this diagnosis less likely in our patient.

Darier disease, also known as keratosis follicularis, is a genetic disorder characterized by greasy, warty papules primarily on seborrheic areas of the skin, nail abnormalities, and sometimes mucosal involvement. Nail changes in Darier disease include longitudinal red and white streaks, V-shaped notching at the free edge of the nails, and subungual hyperkeratosis. These nail changes are more severe and distinct than the simple transverse ridging seen in chevron nails. The absence of other clinical signs of Darier disease, such as skin papules or characteristic nail notching, makes this diagnosis unlikely in our patient.

Pachyonychia congenita is a rare genetic disorder characterized by thickened nails (pachyonychia), painful plantar keratoderma, and sometimes oral leukokeratosis. The condition typically presents with significant nail thickening and other systemic findings, which were absent in our patient. The distinct pattern of V-shaped ridging observed in chevron nails does not align with the typical presentation of pachyonychia congenita.

Next Steps

No specific treatment is required for chevron nails. The condition is typically self-resolving, and the nails usually return to a normal appearance as the child continues to grow. Parents were advised to monitor the nails for any changes or new symptoms and were reassured about the benign nature of the findings. Follow-up was scheduled to ensure the resolution of the condition as the child develops.

Conclusion

Chevron nails are an important consideration in the differential diagnosis of transverse nail ridging in infants and young children. While the condition is benign and self-limiting, it is crucial to differentiate it from other nail dystrophies, such as trachyonychia, lichen planus, Darier disease, and pachyonychia congenita, which may require further investigation or intervention. Awareness of chevron nails can help prevent unnecessary worry and provide reassurance to parents and caregivers.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

Suggested Reading

Delano S, Belazarian L. Chevron nails: A normal variant in the pediatric population. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014 Jan-Feb;31(1):e24-5. doi: 10.1111/pde.12193.

John JM et al. Chevron nail — An under-recognised normal variant of nail development. Arch Dis Child. 2024 Jul 18;109(8):648. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2024-326975.

Shuster S. The significance of chevron nails. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:151–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1996.d01-961.x.

Starace M et al. Nail disorders in children. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018 Oct;4(4):217-229. doi: 10.1159/000486020.

Given the clinical presentation and the absence of other systemic or dermatological findings, the diagnosis of chevron nails was made.

Discussion

The condition is characterized by transverse ridges on the nails that converge towards the center, forming a V or chevron shape. This condition was first described by Perry et al. and later by Shuster et al., who explained that the condition might result from axial growth of the nail with synchronous growth occurring from a chevron-shaped growing edge of the nail root. Alternatively, Shuster suggested that sequential growth, with localized variation in the nail production rate, could propagate a wave from the center of the nail to the edge.

The etiology of chevron nails is not well understood, but it is believed to result from temporary disruptions in the nail matrix, possibly related to minor illness or physiological stress during infancy.

In the case of our 7-month-old patient, the history of mild upper respiratory infections might have contributed to the development of chevron nails. However, the lack of other significant illness, skin involvement, or systemic findings supports the benign and self-limiting nature of this condition. Parents were reassured that chevron nails typically resolve on their own as the child grows and that no specific treatment is necessary.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of transverse nail changes in children includes other conditions such as trachyonychia, lichen planus, Darier disease, and pachyonychia congenita.

Trachyonychia, also known as “sandpaper nails,” trachyonychia is characterized by the roughening of the nail surface, giving it a dull and ridged appearance. The condition may affect all 20 nails and is often associated with underlying dermatological conditions such as lichen planus or alopecia areata. Unlike chevron nails, trachyonychia presents with more diffuse nail changes and does not typically feature the distinct V-shaped ridging seen in this patient.

Lichen planus is an inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, mucous membranes, and nails. Nail involvement in lichen planus can lead to longitudinal ridging, thinning, and sometimes even complete nail loss. The absence of other characteristic features of lichen planus, such as violaceous papules on the skin or white lacy patterns on mucous membranes (Wickham striae), makes this diagnosis less likely in our patient.

Darier disease, also known as keratosis follicularis, is a genetic disorder characterized by greasy, warty papules primarily on seborrheic areas of the skin, nail abnormalities, and sometimes mucosal involvement. Nail changes in Darier disease include longitudinal red and white streaks, V-shaped notching at the free edge of the nails, and subungual hyperkeratosis. These nail changes are more severe and distinct than the simple transverse ridging seen in chevron nails. The absence of other clinical signs of Darier disease, such as skin papules or characteristic nail notching, makes this diagnosis unlikely in our patient.

Pachyonychia congenita is a rare genetic disorder characterized by thickened nails (pachyonychia), painful plantar keratoderma, and sometimes oral leukokeratosis. The condition typically presents with significant nail thickening and other systemic findings, which were absent in our patient. The distinct pattern of V-shaped ridging observed in chevron nails does not align with the typical presentation of pachyonychia congenita.

Next Steps

No specific treatment is required for chevron nails. The condition is typically self-resolving, and the nails usually return to a normal appearance as the child continues to grow. Parents were advised to monitor the nails for any changes or new symptoms and were reassured about the benign nature of the findings. Follow-up was scheduled to ensure the resolution of the condition as the child develops.

Conclusion

Chevron nails are an important consideration in the differential diagnosis of transverse nail ridging in infants and young children. While the condition is benign and self-limiting, it is crucial to differentiate it from other nail dystrophies, such as trachyonychia, lichen planus, Darier disease, and pachyonychia congenita, which may require further investigation or intervention. Awareness of chevron nails can help prevent unnecessary worry and provide reassurance to parents and caregivers.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

Suggested Reading

Delano S, Belazarian L. Chevron nails: A normal variant in the pediatric population. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014 Jan-Feb;31(1):e24-5. doi: 10.1111/pde.12193.

John JM et al. Chevron nail — An under-recognised normal variant of nail development. Arch Dis Child. 2024 Jul 18;109(8):648. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2024-326975.

Shuster S. The significance of chevron nails. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:151–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1996.d01-961.x.

Starace M et al. Nail disorders in children. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018 Oct;4(4):217-229. doi: 10.1159/000486020.

Given the clinical presentation and the absence of other systemic or dermatological findings, the diagnosis of chevron nails was made.

Discussion

The condition is characterized by transverse ridges on the nails that converge towards the center, forming a V or chevron shape. This condition was first described by Perry et al. and later by Shuster et al., who explained that the condition might result from axial growth of the nail with synchronous growth occurring from a chevron-shaped growing edge of the nail root. Alternatively, Shuster suggested that sequential growth, with localized variation in the nail production rate, could propagate a wave from the center of the nail to the edge.

The etiology of chevron nails is not well understood, but it is believed to result from temporary disruptions in the nail matrix, possibly related to minor illness or physiological stress during infancy.

In the case of our 7-month-old patient, the history of mild upper respiratory infections might have contributed to the development of chevron nails. However, the lack of other significant illness, skin involvement, or systemic findings supports the benign and self-limiting nature of this condition. Parents were reassured that chevron nails typically resolve on their own as the child grows and that no specific treatment is necessary.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of transverse nail changes in children includes other conditions such as trachyonychia, lichen planus, Darier disease, and pachyonychia congenita.

Trachyonychia, also known as “sandpaper nails,” trachyonychia is characterized by the roughening of the nail surface, giving it a dull and ridged appearance. The condition may affect all 20 nails and is often associated with underlying dermatological conditions such as lichen planus or alopecia areata. Unlike chevron nails, trachyonychia presents with more diffuse nail changes and does not typically feature the distinct V-shaped ridging seen in this patient.

Lichen planus is an inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, mucous membranes, and nails. Nail involvement in lichen planus can lead to longitudinal ridging, thinning, and sometimes even complete nail loss. The absence of other characteristic features of lichen planus, such as violaceous papules on the skin or white lacy patterns on mucous membranes (Wickham striae), makes this diagnosis less likely in our patient.

Darier disease, also known as keratosis follicularis, is a genetic disorder characterized by greasy, warty papules primarily on seborrheic areas of the skin, nail abnormalities, and sometimes mucosal involvement. Nail changes in Darier disease include longitudinal red and white streaks, V-shaped notching at the free edge of the nails, and subungual hyperkeratosis. These nail changes are more severe and distinct than the simple transverse ridging seen in chevron nails. The absence of other clinical signs of Darier disease, such as skin papules or characteristic nail notching, makes this diagnosis unlikely in our patient.

Pachyonychia congenita is a rare genetic disorder characterized by thickened nails (pachyonychia), painful plantar keratoderma, and sometimes oral leukokeratosis. The condition typically presents with significant nail thickening and other systemic findings, which were absent in our patient. The distinct pattern of V-shaped ridging observed in chevron nails does not align with the typical presentation of pachyonychia congenita.

Next Steps

No specific treatment is required for chevron nails. The condition is typically self-resolving, and the nails usually return to a normal appearance as the child continues to grow. Parents were advised to monitor the nails for any changes or new symptoms and were reassured about the benign nature of the findings. Follow-up was scheduled to ensure the resolution of the condition as the child develops.

Conclusion

Chevron nails are an important consideration in the differential diagnosis of transverse nail ridging in infants and young children. While the condition is benign and self-limiting, it is crucial to differentiate it from other nail dystrophies, such as trachyonychia, lichen planus, Darier disease, and pachyonychia congenita, which may require further investigation or intervention. Awareness of chevron nails can help prevent unnecessary worry and provide reassurance to parents and caregivers.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

Suggested Reading

Delano S, Belazarian L. Chevron nails: A normal variant in the pediatric population. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014 Jan-Feb;31(1):e24-5. doi: 10.1111/pde.12193.

John JM et al. Chevron nail — An under-recognised normal variant of nail development. Arch Dis Child. 2024 Jul 18;109(8):648. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2024-326975.

Shuster S. The significance of chevron nails. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:151–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1996.d01-961.x.

Starace M et al. Nail disorders in children. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018 Oct;4(4):217-229. doi: 10.1159/000486020.

There was no family history of similar nail findings and no relatives had a history of chronic skin conditions or congenital nail disorders.

On physical examination, several of the child’s fingernails exhibited distinct longitudinal ridges, with a characteristic pattern where the ridges converged at the center of the nail, forming a V-shape. There were no other concerning dermatologic findings, such as rashes, plaques, or erosions, and the skin and hair appeared otherwise normal. The rest of the physical exam was unremarkable.

A 7-year-old female presents with persistent pimples on the nose and cheeks for approximately 1 year

Diagnosis

During the visit, skin scrapings were performed, revealing several Demodex mites, confirming the diagnosis of demodicosis.

Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis are the two common species implicated. The life cycle of Demodex spp. occurs in the sebaceous glands, leading to mechanical and chemical irritation of the skin.

Various immune responses are also triggered, such as a keratinocyte response via Toll-like receptor 2. Patients usually present with non-specific symptoms such as skin erythema, irritation, peeling, and dryness on the cheeks, eyelids, and paranasal areas. Patients may develop a maculopapular or rosacea-like rash.

Diagnosis is often made through microscopic examination of a skin sample in KOH solution. In rare occasions, a skin surface standardization biopsy method may be used, which determines the density of mites per 1 cm2. Dermoscopy may identify spiky white structures. Molecular methods such as PCR can be used but are not standard.

The differential diagnosis may include acne, rosacea, folliculitis, and Candida infection. Demodicosis can be differentiated by history and further studies including dermoscopy.

Acne vulgaris is an inflammatory disease of the skin’s pilosebaceous unit, primarily involving the face and trunk. It can present with comedones, papules, pustules, and nodules. Secondary signs suggestive of acne vulgaris include scars, erythema, and hyperpigmentation. All forms of acne share a common pathogenesis resulting in the formation of microcomedones, precursors for all clinical acne lesions. In this patient, the absence of microcomedones and the presence of primary inflammatory papules localized to the nose and cheeks suggested an alternative diagnosis.

Rosacea was also considered in the differential diagnosis. Rosacea is an inflammatory dermatosis characterized by erythema, telangiectasia, recurrent flushing, and inflammatory lesions including papulopustules and swelling, primarily affecting the face. The pathogenesis of rosacea is not fully understood but is suggested to involve immune-mediated responses. Vascular dysregulation and reactive oxygen species damage keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells. A higher incidence of rosacea in those with a family history and UV exposure is a known trigger. Demodex folliculorum and Helicobacter pylori are also implicated. Occasionally, Demodex infestation and rosacea may co-occur, and treatment with topical metronidazole can be helpful.

Folliculitis is an infection and inflammation of the hair follicles, forming pustules or erythematous papules over hair-covered skin. It is commonly caused by bacterial infection but can also be due to fungi, viruses, and noninfectious causes such as eosinophilic folliculitis. Diagnosis is clinical, based on physical exam and history, such as recent increased sweating or scratching. KOH prep can be used for Malassezia folliculitis and skin biopsy for eosinophilic folliculitis. Treatment targets the underlying cause. Most bacterial folliculitis cases resolve without treatment, but topical antibiotics may be used. Fungal folliculitis requires oral antifungals, and herpes simplex folliculitis can be treated with antiviral medications.

Cutaneous candidiasis is an infection of the skin by various Candida species, commonly C. albicans. Superficial infections of the skin and mucous membranes, such as intertrigo, are common types. Risk factors include immunosuppression, endocrine disorders, or compromised blood flow. Increased humidity, occlusion, broken skin barriers, and altered skin microbial flora contribute to Candida infection. Diagnosis is clinical but can be confirmed by KOH prep, microscopy, and culture. Treatment involves anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antifungal medications. Topical clotrimazole, nystatin, and miconazole are commonly used. Recurrence is prevented by keeping the affected area dry with barrier creams.

Therapeutic goals include arresting mite reproduction, elimination, and preventing recurrent infestations. Treatment may last several months, and the choice of drug depends on patient factors. There have been no standardized treatment studies or long-term effectiveness analyses. Antibiotics such as tetracycline, metronidazole, doxycycline, and ivermectin may be used to prevent proliferation. Permethrin, benzyl benzoate, crotamiton, lindane, and sulfur have also been used. Metronidazole is a common treatment for demodicosis, as was used in our patient for several weeks until the lesions cleared. Systemic metronidazole therapy may be indicated for reducing Demodex spp. density. Severe cases, particularly in immunocompromised individuals, may require oral ivermectin. Appropriate hygiene is important for prevention, such as washing the face with non-oily cleansers and laundering linens regularly.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Mr. Lee is a medical student at the University of California San Diego.

Suggested Reading

Chudzicka-Strugała I et al. Demodicosis in different age groups and alternative treatment options—A review. J Clin Med. 2023 Feb 19;12(4):1649. doi: 10.3390/jcm12041649.

Eichenfield DZ et al. Management of acne vulgaris: A review. JAMA. 2021 Nov 23;326(20):2055-2067. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.17633.

Sharma A et al. Rosacea management: A comprehensive review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 May;21(5):1895-1904. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14816.

Taudorf EH et al. Cutaneous candidiasis — an evidence-based review of topical and systemic treatments to inform clinical practice. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Oct;33(10):1863-1873. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15782.

Winters RD, Mitchell M. Folliculitis. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547754/

Diagnosis

During the visit, skin scrapings were performed, revealing several Demodex mites, confirming the diagnosis of demodicosis.

Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis are the two common species implicated. The life cycle of Demodex spp. occurs in the sebaceous glands, leading to mechanical and chemical irritation of the skin.

Various immune responses are also triggered, such as a keratinocyte response via Toll-like receptor 2. Patients usually present with non-specific symptoms such as skin erythema, irritation, peeling, and dryness on the cheeks, eyelids, and paranasal areas. Patients may develop a maculopapular or rosacea-like rash.

Diagnosis is often made through microscopic examination of a skin sample in KOH solution. In rare occasions, a skin surface standardization biopsy method may be used, which determines the density of mites per 1 cm2. Dermoscopy may identify spiky white structures. Molecular methods such as PCR can be used but are not standard.

The differential diagnosis may include acne, rosacea, folliculitis, and Candida infection. Demodicosis can be differentiated by history and further studies including dermoscopy.

Acne vulgaris is an inflammatory disease of the skin’s pilosebaceous unit, primarily involving the face and trunk. It can present with comedones, papules, pustules, and nodules. Secondary signs suggestive of acne vulgaris include scars, erythema, and hyperpigmentation. All forms of acne share a common pathogenesis resulting in the formation of microcomedones, precursors for all clinical acne lesions. In this patient, the absence of microcomedones and the presence of primary inflammatory papules localized to the nose and cheeks suggested an alternative diagnosis.

Rosacea was also considered in the differential diagnosis. Rosacea is an inflammatory dermatosis characterized by erythema, telangiectasia, recurrent flushing, and inflammatory lesions including papulopustules and swelling, primarily affecting the face. The pathogenesis of rosacea is not fully understood but is suggested to involve immune-mediated responses. Vascular dysregulation and reactive oxygen species damage keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells. A higher incidence of rosacea in those with a family history and UV exposure is a known trigger. Demodex folliculorum and Helicobacter pylori are also implicated. Occasionally, Demodex infestation and rosacea may co-occur, and treatment with topical metronidazole can be helpful.

Folliculitis is an infection and inflammation of the hair follicles, forming pustules or erythematous papules over hair-covered skin. It is commonly caused by bacterial infection but can also be due to fungi, viruses, and noninfectious causes such as eosinophilic folliculitis. Diagnosis is clinical, based on physical exam and history, such as recent increased sweating or scratching. KOH prep can be used for Malassezia folliculitis and skin biopsy for eosinophilic folliculitis. Treatment targets the underlying cause. Most bacterial folliculitis cases resolve without treatment, but topical antibiotics may be used. Fungal folliculitis requires oral antifungals, and herpes simplex folliculitis can be treated with antiviral medications.

Cutaneous candidiasis is an infection of the skin by various Candida species, commonly C. albicans. Superficial infections of the skin and mucous membranes, such as intertrigo, are common types. Risk factors include immunosuppression, endocrine disorders, or compromised blood flow. Increased humidity, occlusion, broken skin barriers, and altered skin microbial flora contribute to Candida infection. Diagnosis is clinical but can be confirmed by KOH prep, microscopy, and culture. Treatment involves anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antifungal medications. Topical clotrimazole, nystatin, and miconazole are commonly used. Recurrence is prevented by keeping the affected area dry with barrier creams.

Therapeutic goals include arresting mite reproduction, elimination, and preventing recurrent infestations. Treatment may last several months, and the choice of drug depends on patient factors. There have been no standardized treatment studies or long-term effectiveness analyses. Antibiotics such as tetracycline, metronidazole, doxycycline, and ivermectin may be used to prevent proliferation. Permethrin, benzyl benzoate, crotamiton, lindane, and sulfur have also been used. Metronidazole is a common treatment for demodicosis, as was used in our patient for several weeks until the lesions cleared. Systemic metronidazole therapy may be indicated for reducing Demodex spp. density. Severe cases, particularly in immunocompromised individuals, may require oral ivermectin. Appropriate hygiene is important for prevention, such as washing the face with non-oily cleansers and laundering linens regularly.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Mr. Lee is a medical student at the University of California San Diego.

Suggested Reading

Chudzicka-Strugała I et al. Demodicosis in different age groups and alternative treatment options—A review. J Clin Med. 2023 Feb 19;12(4):1649. doi: 10.3390/jcm12041649.

Eichenfield DZ et al. Management of acne vulgaris: A review. JAMA. 2021 Nov 23;326(20):2055-2067. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.17633.

Sharma A et al. Rosacea management: A comprehensive review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 May;21(5):1895-1904. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14816.

Taudorf EH et al. Cutaneous candidiasis — an evidence-based review of topical and systemic treatments to inform clinical practice. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Oct;33(10):1863-1873. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15782.

Winters RD, Mitchell M. Folliculitis. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547754/

Diagnosis

During the visit, skin scrapings were performed, revealing several Demodex mites, confirming the diagnosis of demodicosis.

Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis are the two common species implicated. The life cycle of Demodex spp. occurs in the sebaceous glands, leading to mechanical and chemical irritation of the skin.

Various immune responses are also triggered, such as a keratinocyte response via Toll-like receptor 2. Patients usually present with non-specific symptoms such as skin erythema, irritation, peeling, and dryness on the cheeks, eyelids, and paranasal areas. Patients may develop a maculopapular or rosacea-like rash.

Diagnosis is often made through microscopic examination of a skin sample in KOH solution. In rare occasions, a skin surface standardization biopsy method may be used, which determines the density of mites per 1 cm2. Dermoscopy may identify spiky white structures. Molecular methods such as PCR can be used but are not standard.

The differential diagnosis may include acne, rosacea, folliculitis, and Candida infection. Demodicosis can be differentiated by history and further studies including dermoscopy.

Acne vulgaris is an inflammatory disease of the skin’s pilosebaceous unit, primarily involving the face and trunk. It can present with comedones, papules, pustules, and nodules. Secondary signs suggestive of acne vulgaris include scars, erythema, and hyperpigmentation. All forms of acne share a common pathogenesis resulting in the formation of microcomedones, precursors for all clinical acne lesions. In this patient, the absence of microcomedones and the presence of primary inflammatory papules localized to the nose and cheeks suggested an alternative diagnosis.

Rosacea was also considered in the differential diagnosis. Rosacea is an inflammatory dermatosis characterized by erythema, telangiectasia, recurrent flushing, and inflammatory lesions including papulopustules and swelling, primarily affecting the face. The pathogenesis of rosacea is not fully understood but is suggested to involve immune-mediated responses. Vascular dysregulation and reactive oxygen species damage keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells. A higher incidence of rosacea in those with a family history and UV exposure is a known trigger. Demodex folliculorum and Helicobacter pylori are also implicated. Occasionally, Demodex infestation and rosacea may co-occur, and treatment with topical metronidazole can be helpful.

Folliculitis is an infection and inflammation of the hair follicles, forming pustules or erythematous papules over hair-covered skin. It is commonly caused by bacterial infection but can also be due to fungi, viruses, and noninfectious causes such as eosinophilic folliculitis. Diagnosis is clinical, based on physical exam and history, such as recent increased sweating or scratching. KOH prep can be used for Malassezia folliculitis and skin biopsy for eosinophilic folliculitis. Treatment targets the underlying cause. Most bacterial folliculitis cases resolve without treatment, but topical antibiotics may be used. Fungal folliculitis requires oral antifungals, and herpes simplex folliculitis can be treated with antiviral medications.

Cutaneous candidiasis is an infection of the skin by various Candida species, commonly C. albicans. Superficial infections of the skin and mucous membranes, such as intertrigo, are common types. Risk factors include immunosuppression, endocrine disorders, or compromised blood flow. Increased humidity, occlusion, broken skin barriers, and altered skin microbial flora contribute to Candida infection. Diagnosis is clinical but can be confirmed by KOH prep, microscopy, and culture. Treatment involves anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antifungal medications. Topical clotrimazole, nystatin, and miconazole are commonly used. Recurrence is prevented by keeping the affected area dry with barrier creams.

Therapeutic goals include arresting mite reproduction, elimination, and preventing recurrent infestations. Treatment may last several months, and the choice of drug depends on patient factors. There have been no standardized treatment studies or long-term effectiveness analyses. Antibiotics such as tetracycline, metronidazole, doxycycline, and ivermectin may be used to prevent proliferation. Permethrin, benzyl benzoate, crotamiton, lindane, and sulfur have also been used. Metronidazole is a common treatment for demodicosis, as was used in our patient for several weeks until the lesions cleared. Systemic metronidazole therapy may be indicated for reducing Demodex spp. density. Severe cases, particularly in immunocompromised individuals, may require oral ivermectin. Appropriate hygiene is important for prevention, such as washing the face with non-oily cleansers and laundering linens regularly.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Mr. Lee is a medical student at the University of California San Diego.

Suggested Reading

Chudzicka-Strugała I et al. Demodicosis in different age groups and alternative treatment options—A review. J Clin Med. 2023 Feb 19;12(4):1649. doi: 10.3390/jcm12041649.

Eichenfield DZ et al. Management of acne vulgaris: A review. JAMA. 2021 Nov 23;326(20):2055-2067. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.17633.

Sharma A et al. Rosacea management: A comprehensive review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 May;21(5):1895-1904. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14816.

Taudorf EH et al. Cutaneous candidiasis — an evidence-based review of topical and systemic treatments to inform clinical practice. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Oct;33(10):1863-1873. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15782.

Winters RD, Mitchell M. Folliculitis. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547754/

A 7-year-old female presents with persistent pimples on the nose and cheeks for approximately 1 year. She had been treated with several topical antibiotics and acne washes without resolution of the lesions. There were no signs of early puberty, and the child had no history of medical conditions. Her mother has a history of rosacea. Physical examination revealed erythematous papules on the nose and cheeks bilaterally.

A 6-Year-Old Female Presents With a Bruise-Like Lesion on the Lip, Tongue, and Chin Area Present Since Birth

Diagnosis: Venous Malformation

Although present at birth, they are not always clinically evident early in life. They also tend to grow with the child without spontaneous regression, causing potential cosmetic concerns or complications from impingement on surrounding tissue.

Venous malformations appear with a bluish color appearing beneath the skin and can vary significantly in size and severity. Venous malformations are compressible and characterized by low to stagnant blood flow, which can spontaneously thrombose. Clinically, this may cause pain, swelling, skin changes, tissue and limb overgrowth, or functional impairment depending on location and size.

Venous malformations result from disorganized angiogenesis secondary to sporadic mutations in somatic cells. The most common implicated gene is TEK, a receptor tyrosine kinase. PIK3CA has also been involved. Both genes are involved in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, which regulates cell growth, proliferation, and angiogenesis. In venous endothelial cells, abnormal angiogenesis and vessel maturation may lead to venous malformation formation. Dysplastic vessels frequently separate from normal veins but may be contiguous with the deep venous system.

Diagnosis involves clinical history and physical examination. Imaging with ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be utilized. While ultrasound may be preferred for superficial venous malformations, MRI or MRI with MR angiography (MRA) is the preferred method for venous malformation assessment. Genetic testing may be appropriate for complex malformations, as classification of lesions by underlying mutation may allow targeted therapy.

This patient’s past MRI and MRA findings were consistent with a venous malformation.

Treatment

Venous malformations rarely regress spontaneously. Treatment is required if venous malformations are symptomatic, which may include pain, swelling, deformity, thrombosis, or interference with daily activities of living. Treatment plans require consideration of patient goals of care. The main categories of therapy are embolization/sclerotherapy, surgical resection, and molecular targeted therapy.

Sclerotherapy is a well-tolerated and efficacious first-line therapy. It can be used as either nonsurgical curative therapy or preoperative adjunct therapy to minimize blood loss before surgical resection. While surgical resection may cause scarring, multimodal approaches with sclerotherapy or laser therapy can decrease complications. Molecular therapies aim to reduce vascular proliferation and symptoms. Referral to hematology/oncology for evaluation and consideration of chemotherapeutic agents may be required. Sirolimus has been shown in mice models to inhibit an endothelial cell tyrosine kinase receptor that plays a role in venous malformation growth. Multiple studies have proved its efficacy in managing complicated vascular anomalies, including venous malformations. Alpelisib is an inhibitor of PI3KCA, which is part of the pathway that contributes to venous malformation formation. Dactolisib, a dual inhibitor of the PI3KA and mTOR pathways, and rebastinib, a TEK inhibitor, are being investigated.

Differential Diagnoses

The differential diagnosis includes dermal melanocytosis, nevus of Ota, hemangioma of infancy, and ashy dermatosis. In addition, venous malformations can be part of more complex vascular malformations.

Dermal melanocytosis, also known as Mongolian spots, are blue-gray patches of discoloration on the skin that appear at birth or shortly after. They result from the arrest of dermal melanocytes in the dermis during fetal life and tissue modeling. They are commonly observed in those of Asian or African descent with darker skin types. Most often, they are located in the lumbar or sacral-gluteal region. Unlike venous malformations, they are benign and do not involve vascular abnormalities. They typically fade over time.

Nevus of Ota is a benign congenital condition that presents with blue-gray or brown patches of pigmentation on the skin around the eyes, cheeks, and forehead. They are dermal melanocytes with a speckled instead of uniform appearance. Nevus of Ota primarily affects individuals of Asian descent and typically presents in the trigeminal nerve distribution region. Treatment can be done to minimize deformity, generally with pigmented laser surgery.

Hemangiomas of infancy are common benign tumors of infancy caused by endothelial cell proliferation. They are characterized by rapid growth followed by spontaneous involution within the first year of life and for several years. Hemangiomas can be superficial, deep, or mixed with features of both superficial and deep. Superficial hemangiomas present as raised, lobulated, and bright red while deep hemangiomas present as a bluish-hued nodule, plaque, or tumor. They are diagnosed clinically but skin biopsies and imaging can confirm the suspected diagnosis. While hemangiomas may self-resolve, complicated hemangiomas can be treated with topical timolol, oral propranolol, topical and intralesional corticosteroids, pulsed-dye laser, and surgical resection.

Ashy dermatosis is a term for asymptomatic, gray-blue or ashy patches distributed symmetrically on the trunk, head, neck, and upper extremities. It primarily affects individuals with darker skin types (Fitzpatrick III-V), and is more common in patients with Hispanic, Asian, or African backgrounds. The direct cause of ashy dermatosis is unknown but it is thought to be linked to drug ingestion, genetics, infection, and immune-mediated mechanisms. The general treatment includes topical corticosteroids, clofazimine, topical calcineurin inhibitors, oral dapsone, phototherapy, topical retinoids, or isotretinoin to reduce inflammation and pigmentation.

Danny Lee and Samuel Le serve as research fellows and Jolina Bui as research associate in the Pediatric Dermatology Division of the Department of Dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is Distinguished Professor of Dermatology and Pediatrics and Vice-Chair of the Department of Dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. The authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

Suggested Reading

Agarwal P, Patel BC. Nevus of Ota and Ito. [Updated 2023 Jul 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

Dompmartin A et al. The VASCERN-VASCA Working Group Diagnostic and Management Pathways for Venous Malformations. J Vasc Anom (Phila). 2023 Mar 23;4(2):e064.

Dompmartin A et al. Venous malformation: Update on aetiopathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Phlebology. 2010 Oct;25(5):224-235.

Gupta D, Thappa DM. Mongolian spots. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013 Jul-Aug;79(4):469-478.

Krowchuk DP et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Infantile Hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019 Jan;143(1):e20183475.

Nguyen K, Khachemoune A. Ashy dermatosis: A review. Dermatol Online J. 2019 May 15;25(5):13030/qt44f462s8.

Patel ND, Chong AT et al. Venous Malformations. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2022 Dec 20;39(5):498-507.

Diagnosis: Venous Malformation

Although present at birth, they are not always clinically evident early in life. They also tend to grow with the child without spontaneous regression, causing potential cosmetic concerns or complications from impingement on surrounding tissue.

Venous malformations appear with a bluish color appearing beneath the skin and can vary significantly in size and severity. Venous malformations are compressible and characterized by low to stagnant blood flow, which can spontaneously thrombose. Clinically, this may cause pain, swelling, skin changes, tissue and limb overgrowth, or functional impairment depending on location and size.

Venous malformations result from disorganized angiogenesis secondary to sporadic mutations in somatic cells. The most common implicated gene is TEK, a receptor tyrosine kinase. PIK3CA has also been involved. Both genes are involved in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, which regulates cell growth, proliferation, and angiogenesis. In venous endothelial cells, abnormal angiogenesis and vessel maturation may lead to venous malformation formation. Dysplastic vessels frequently separate from normal veins but may be contiguous with the deep venous system.

Diagnosis involves clinical history and physical examination. Imaging with ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be utilized. While ultrasound may be preferred for superficial venous malformations, MRI or MRI with MR angiography (MRA) is the preferred method for venous malformation assessment. Genetic testing may be appropriate for complex malformations, as classification of lesions by underlying mutation may allow targeted therapy.

This patient’s past MRI and MRA findings were consistent with a venous malformation.

Treatment

Venous malformations rarely regress spontaneously. Treatment is required if venous malformations are symptomatic, which may include pain, swelling, deformity, thrombosis, or interference with daily activities of living. Treatment plans require consideration of patient goals of care. The main categories of therapy are embolization/sclerotherapy, surgical resection, and molecular targeted therapy.

Sclerotherapy is a well-tolerated and efficacious first-line therapy. It can be used as either nonsurgical curative therapy or preoperative adjunct therapy to minimize blood loss before surgical resection. While surgical resection may cause scarring, multimodal approaches with sclerotherapy or laser therapy can decrease complications. Molecular therapies aim to reduce vascular proliferation and symptoms. Referral to hematology/oncology for evaluation and consideration of chemotherapeutic agents may be required. Sirolimus has been shown in mice models to inhibit an endothelial cell tyrosine kinase receptor that plays a role in venous malformation growth. Multiple studies have proved its efficacy in managing complicated vascular anomalies, including venous malformations. Alpelisib is an inhibitor of PI3KCA, which is part of the pathway that contributes to venous malformation formation. Dactolisib, a dual inhibitor of the PI3KA and mTOR pathways, and rebastinib, a TEK inhibitor, are being investigated.

Differential Diagnoses

The differential diagnosis includes dermal melanocytosis, nevus of Ota, hemangioma of infancy, and ashy dermatosis. In addition, venous malformations can be part of more complex vascular malformations.

Dermal melanocytosis, also known as Mongolian spots, are blue-gray patches of discoloration on the skin that appear at birth or shortly after. They result from the arrest of dermal melanocytes in the dermis during fetal life and tissue modeling. They are commonly observed in those of Asian or African descent with darker skin types. Most often, they are located in the lumbar or sacral-gluteal region. Unlike venous malformations, they are benign and do not involve vascular abnormalities. They typically fade over time.

Nevus of Ota is a benign congenital condition that presents with blue-gray or brown patches of pigmentation on the skin around the eyes, cheeks, and forehead. They are dermal melanocytes with a speckled instead of uniform appearance. Nevus of Ota primarily affects individuals of Asian descent and typically presents in the trigeminal nerve distribution region. Treatment can be done to minimize deformity, generally with pigmented laser surgery.

Hemangiomas of infancy are common benign tumors of infancy caused by endothelial cell proliferation. They are characterized by rapid growth followed by spontaneous involution within the first year of life and for several years. Hemangiomas can be superficial, deep, or mixed with features of both superficial and deep. Superficial hemangiomas present as raised, lobulated, and bright red while deep hemangiomas present as a bluish-hued nodule, plaque, or tumor. They are diagnosed clinically but skin biopsies and imaging can confirm the suspected diagnosis. While hemangiomas may self-resolve, complicated hemangiomas can be treated with topical timolol, oral propranolol, topical and intralesional corticosteroids, pulsed-dye laser, and surgical resection.

Ashy dermatosis is a term for asymptomatic, gray-blue or ashy patches distributed symmetrically on the trunk, head, neck, and upper extremities. It primarily affects individuals with darker skin types (Fitzpatrick III-V), and is more common in patients with Hispanic, Asian, or African backgrounds. The direct cause of ashy dermatosis is unknown but it is thought to be linked to drug ingestion, genetics, infection, and immune-mediated mechanisms. The general treatment includes topical corticosteroids, clofazimine, topical calcineurin inhibitors, oral dapsone, phototherapy, topical retinoids, or isotretinoin to reduce inflammation and pigmentation.

Danny Lee and Samuel Le serve as research fellows and Jolina Bui as research associate in the Pediatric Dermatology Division of the Department of Dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is Distinguished Professor of Dermatology and Pediatrics and Vice-Chair of the Department of Dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. The authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

Suggested Reading

Agarwal P, Patel BC. Nevus of Ota and Ito. [Updated 2023 Jul 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

Dompmartin A et al. The VASCERN-VASCA Working Group Diagnostic and Management Pathways for Venous Malformations. J Vasc Anom (Phila). 2023 Mar 23;4(2):e064.

Dompmartin A et al. Venous malformation: Update on aetiopathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Phlebology. 2010 Oct;25(5):224-235.

Gupta D, Thappa DM. Mongolian spots. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013 Jul-Aug;79(4):469-478.

Krowchuk DP et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Infantile Hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019 Jan;143(1):e20183475.

Nguyen K, Khachemoune A. Ashy dermatosis: A review. Dermatol Online J. 2019 May 15;25(5):13030/qt44f462s8.

Patel ND, Chong AT et al. Venous Malformations. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2022 Dec 20;39(5):498-507.

Diagnosis: Venous Malformation

Although present at birth, they are not always clinically evident early in life. They also tend to grow with the child without spontaneous regression, causing potential cosmetic concerns or complications from impingement on surrounding tissue.

Venous malformations appear with a bluish color appearing beneath the skin and can vary significantly in size and severity. Venous malformations are compressible and characterized by low to stagnant blood flow, which can spontaneously thrombose. Clinically, this may cause pain, swelling, skin changes, tissue and limb overgrowth, or functional impairment depending on location and size.

Venous malformations result from disorganized angiogenesis secondary to sporadic mutations in somatic cells. The most common implicated gene is TEK, a receptor tyrosine kinase. PIK3CA has also been involved. Both genes are involved in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, which regulates cell growth, proliferation, and angiogenesis. In venous endothelial cells, abnormal angiogenesis and vessel maturation may lead to venous malformation formation. Dysplastic vessels frequently separate from normal veins but may be contiguous with the deep venous system.

Diagnosis involves clinical history and physical examination. Imaging with ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be utilized. While ultrasound may be preferred for superficial venous malformations, MRI or MRI with MR angiography (MRA) is the preferred method for venous malformation assessment. Genetic testing may be appropriate for complex malformations, as classification of lesions by underlying mutation may allow targeted therapy.

This patient’s past MRI and MRA findings were consistent with a venous malformation.

Treatment

Venous malformations rarely regress spontaneously. Treatment is required if venous malformations are symptomatic, which may include pain, swelling, deformity, thrombosis, or interference with daily activities of living. Treatment plans require consideration of patient goals of care. The main categories of therapy are embolization/sclerotherapy, surgical resection, and molecular targeted therapy.

Sclerotherapy is a well-tolerated and efficacious first-line therapy. It can be used as either nonsurgical curative therapy or preoperative adjunct therapy to minimize blood loss before surgical resection. While surgical resection may cause scarring, multimodal approaches with sclerotherapy or laser therapy can decrease complications. Molecular therapies aim to reduce vascular proliferation and symptoms. Referral to hematology/oncology for evaluation and consideration of chemotherapeutic agents may be required. Sirolimus has been shown in mice models to inhibit an endothelial cell tyrosine kinase receptor that plays a role in venous malformation growth. Multiple studies have proved its efficacy in managing complicated vascular anomalies, including venous malformations. Alpelisib is an inhibitor of PI3KCA, which is part of the pathway that contributes to venous malformation formation. Dactolisib, a dual inhibitor of the PI3KA and mTOR pathways, and rebastinib, a TEK inhibitor, are being investigated.

Differential Diagnoses

The differential diagnosis includes dermal melanocytosis, nevus of Ota, hemangioma of infancy, and ashy dermatosis. In addition, venous malformations can be part of more complex vascular malformations.

Dermal melanocytosis, also known as Mongolian spots, are blue-gray patches of discoloration on the skin that appear at birth or shortly after. They result from the arrest of dermal melanocytes in the dermis during fetal life and tissue modeling. They are commonly observed in those of Asian or African descent with darker skin types. Most often, they are located in the lumbar or sacral-gluteal region. Unlike venous malformations, they are benign and do not involve vascular abnormalities. They typically fade over time.

Nevus of Ota is a benign congenital condition that presents with blue-gray or brown patches of pigmentation on the skin around the eyes, cheeks, and forehead. They are dermal melanocytes with a speckled instead of uniform appearance. Nevus of Ota primarily affects individuals of Asian descent and typically presents in the trigeminal nerve distribution region. Treatment can be done to minimize deformity, generally with pigmented laser surgery.

Hemangiomas of infancy are common benign tumors of infancy caused by endothelial cell proliferation. They are characterized by rapid growth followed by spontaneous involution within the first year of life and for several years. Hemangiomas can be superficial, deep, or mixed with features of both superficial and deep. Superficial hemangiomas present as raised, lobulated, and bright red while deep hemangiomas present as a bluish-hued nodule, plaque, or tumor. They are diagnosed clinically but skin biopsies and imaging can confirm the suspected diagnosis. While hemangiomas may self-resolve, complicated hemangiomas can be treated with topical timolol, oral propranolol, topical and intralesional corticosteroids, pulsed-dye laser, and surgical resection.

Ashy dermatosis is a term for asymptomatic, gray-blue or ashy patches distributed symmetrically on the trunk, head, neck, and upper extremities. It primarily affects individuals with darker skin types (Fitzpatrick III-V), and is more common in patients with Hispanic, Asian, or African backgrounds. The direct cause of ashy dermatosis is unknown but it is thought to be linked to drug ingestion, genetics, infection, and immune-mediated mechanisms. The general treatment includes topical corticosteroids, clofazimine, topical calcineurin inhibitors, oral dapsone, phototherapy, topical retinoids, or isotretinoin to reduce inflammation and pigmentation.

Danny Lee and Samuel Le serve as research fellows and Jolina Bui as research associate in the Pediatric Dermatology Division of the Department of Dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is Distinguished Professor of Dermatology and Pediatrics and Vice-Chair of the Department of Dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. The authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

Suggested Reading

Agarwal P, Patel BC. Nevus of Ota and Ito. [Updated 2023 Jul 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

Dompmartin A et al. The VASCERN-VASCA Working Group Diagnostic and Management Pathways for Venous Malformations. J Vasc Anom (Phila). 2023 Mar 23;4(2):e064.

Dompmartin A et al. Venous malformation: Update on aetiopathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Phlebology. 2010 Oct;25(5):224-235.

Gupta D, Thappa DM. Mongolian spots. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013 Jul-Aug;79(4):469-478.

Krowchuk DP et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Infantile Hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019 Jan;143(1):e20183475.