User login

A 4-month-old male was referred for a 3-week history of an itchy generalized rash that started on the neck

Diagnosis: Infection-induced psoriasis (guttate-type, induced by streptococcal intertrigo)

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disorder characterized by well-defined, scaly, erythematous plaques. Guttate psoriasis is a distinct variant of psoriasis that is more common in children and adolescents. Guttate psoriasis usually presents with multiple, scattered, small, drop-like (“guttate”), scaly, erythematous papules and plaques.

The pathophysiology of psoriasis involves an interplay between genetic and environmental factors. Guttate psoriasis is a chronic T-cell–mediated inflammatory disease in which there is an altered balance between T-helper-1 (TH1) and TH2 cells, transcription factor genes, and their products. HLA B-13, B-17, and Cw6 are human leukocyte antigen alleles implicated in genetic susceptibility. It is hypothesized that streptococcal infection precipitates guttate psoriasis by streptococcal superantigen–driven activation of cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen (CLA)–positive lymphocytes. It has been shown that streptococcal exotoxins and streptococcal M proteins act as superantigens.

Diagnosis is often made clinically based on characteristic physical findings and a possible preceding history of streptococcal infection. In patients with streptococcal infection, culture from an appropriate site and measurement of serum antistreptococcal antibody titers (for example, anti-DNase, antihyaluronidase and antistreptolysin-O) can help. A skin biopsy is usually not necessary but may be considered.

This patient presented with intertrigo of the neck and axillae at the time of presentation with the papulosquamous rash. Culture of the intertrigo yielded 4+ Group A beta streptococcus.

Treatment

Although there is currently no cure for guttate psoriasis, various treatment options can relieve symptoms and clear skin lesions, and infection-triggered lesions may remit, usually within several months. However, guttate psoriasis may persist and progress to chronic plaque psoriasis. Many treatment options are based mainly on clinical trials targeted for plaque psoriasis treatment.

For mild psoriasis, topical corticosteroids are first-line treatment. Other topical steroids include vitamin D analogs (calcipotriene), topical retinoids (tazarotene), topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus), and newer non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (roflumilast or tapinarof), neither approved yet in this young age group. In more severe cases, phototherapy with UVB light, traditional systemic immunosuppressive agents (methotrexate, cyclosporine) or targeted biologic therapies may be considered.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis may include generalized intertrigo, pityriasis rubra pilaris, tinea corporis, atopic dermatitis, and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Guttate psoriasis can be distinguished by history and physical exam. Further studies such as potassium hydroxide (KOH) scrapings may be helpful in ruling out the other disorders.

Intertrigo is an inflammatory condition of the flexural surfaces irritated by warm temperatures, friction, moisture, and poor ventilation that is commonly associated with Candida infection and/or streptococcal infection. Candidal intertrigo can present with erythematous patches or plaques in an intertriginous area that may develop erosions, macerations, fissures, crust, and weeping. Satellite papules and pustules are pathognomonic for Candida species. Streptococcal intertrigo usually presents with bright red color and may be painful or pruritic. Perianal streptococcal infection is reported as a trigger of guttate psoriasis in pediatric patients.

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a rare inflammatory papulosquamous disorder with an unknown etiology. Red-orange papules and plaques, hyperkeratotic follicular papules, and palmoplantar hyperkeratosis are primary features. Diagnosis is based on clinical and histopathology. Pityriasis rubra pilaris is self-limited and asymptomatic in many cases. Treatment may not be required, but combination therapy with topical agents includes emollients, keratolytic agents (for example, urea, salicylic acid, alpha-hydroxy acids), topical corticosteroids, tazarotene, and topical calcineurin inhibitors. Systemic agents include oral retinoids and methotrexate.

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that involves genetic and environmental factors, leading to abnormalities in the epidermis and the immune system presenting with its typical morphology and distribution. The morphology of eczematous lesions is distinct from papulosquamous lesions of psoriasis.

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is a toxin-mediated skin disorder which presents with denuded, peeling skin due to epidermolytic exotoxin producing Staphylococcus species. Fever, erythematous rash, malaise, skin pain, and irritability presents initially. Progressive desquamation with accentuation in folds is typical, with progression usually within 1-2 days. Systemic antibiotics covering Staphylococcus should be administered early. Emollients and nonadherent dressings should be applied to affected areas to promote healing. Supportive care includes dehydration management, temperature regulation, and nutrition. Skin desquamation usually occurs within 5 days with resolution within 2 weeks.

This infant displayed streptococcal intertrigo which triggered an early presentation of guttate psoriasis. The patient was managed with completion of a course of oral cephalexin, midstrength topical corticosteroids to the truncal lesions, and mild topical corticosteroids to the face and diaper area with good clinical response.

Danny Lee and Samuel Le serve as research fellows in the Pediatric Dermatology Division of the Department of Dermatology at the University of California San Diego and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is Distinguished Professor of Dermatology and Pediatrics and Vice-Chair of the Department of Dermatology at the University of California San Diego and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. The authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

Suggested Reading

Leung AK et al. Childhood guttate psoriasis: An updated review. Drugs Context. 2023 Oct 23:12:2023-8-2. doi: 10.7573/dic.2023-8-2.

Galili E et al. New-onset guttate psoriasis: A long-term follow-up study. Dermatology. 2023;239(2):188-194. doi: 10.1159/000527737.

Duffin KC et al. Advances and controversies in our understanding of guttate and plaque psoriasis. J Rheumatol. 2023 Nov;50(Suppl 2):4-7. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.2023-0500.

Saleh D, Tanner LS. Guttate Psoriasis. [Updated 2023 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482498/

Dupire G et al. Antistreptococcal interventions for guttate and chronic plaque psoriasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Mar 5;3(3):CD011571. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011571.pub2.

Diagnosis: Infection-induced psoriasis (guttate-type, induced by streptococcal intertrigo)

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disorder characterized by well-defined, scaly, erythematous plaques. Guttate psoriasis is a distinct variant of psoriasis that is more common in children and adolescents. Guttate psoriasis usually presents with multiple, scattered, small, drop-like (“guttate”), scaly, erythematous papules and plaques.

The pathophysiology of psoriasis involves an interplay between genetic and environmental factors. Guttate psoriasis is a chronic T-cell–mediated inflammatory disease in which there is an altered balance between T-helper-1 (TH1) and TH2 cells, transcription factor genes, and their products. HLA B-13, B-17, and Cw6 are human leukocyte antigen alleles implicated in genetic susceptibility. It is hypothesized that streptococcal infection precipitates guttate psoriasis by streptococcal superantigen–driven activation of cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen (CLA)–positive lymphocytes. It has been shown that streptococcal exotoxins and streptococcal M proteins act as superantigens.

Diagnosis is often made clinically based on characteristic physical findings and a possible preceding history of streptococcal infection. In patients with streptococcal infection, culture from an appropriate site and measurement of serum antistreptococcal antibody titers (for example, anti-DNase, antihyaluronidase and antistreptolysin-O) can help. A skin biopsy is usually not necessary but may be considered.

This patient presented with intertrigo of the neck and axillae at the time of presentation with the papulosquamous rash. Culture of the intertrigo yielded 4+ Group A beta streptococcus.

Treatment

Although there is currently no cure for guttate psoriasis, various treatment options can relieve symptoms and clear skin lesions, and infection-triggered lesions may remit, usually within several months. However, guttate psoriasis may persist and progress to chronic plaque psoriasis. Many treatment options are based mainly on clinical trials targeted for plaque psoriasis treatment.

For mild psoriasis, topical corticosteroids are first-line treatment. Other topical steroids include vitamin D analogs (calcipotriene), topical retinoids (tazarotene), topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus), and newer non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (roflumilast or tapinarof), neither approved yet in this young age group. In more severe cases, phototherapy with UVB light, traditional systemic immunosuppressive agents (methotrexate, cyclosporine) or targeted biologic therapies may be considered.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis may include generalized intertrigo, pityriasis rubra pilaris, tinea corporis, atopic dermatitis, and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Guttate psoriasis can be distinguished by history and physical exam. Further studies such as potassium hydroxide (KOH) scrapings may be helpful in ruling out the other disorders.

Intertrigo is an inflammatory condition of the flexural surfaces irritated by warm temperatures, friction, moisture, and poor ventilation that is commonly associated with Candida infection and/or streptococcal infection. Candidal intertrigo can present with erythematous patches or plaques in an intertriginous area that may develop erosions, macerations, fissures, crust, and weeping. Satellite papules and pustules are pathognomonic for Candida species. Streptococcal intertrigo usually presents with bright red color and may be painful or pruritic. Perianal streptococcal infection is reported as a trigger of guttate psoriasis in pediatric patients.

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a rare inflammatory papulosquamous disorder with an unknown etiology. Red-orange papules and plaques, hyperkeratotic follicular papules, and palmoplantar hyperkeratosis are primary features. Diagnosis is based on clinical and histopathology. Pityriasis rubra pilaris is self-limited and asymptomatic in many cases. Treatment may not be required, but combination therapy with topical agents includes emollients, keratolytic agents (for example, urea, salicylic acid, alpha-hydroxy acids), topical corticosteroids, tazarotene, and topical calcineurin inhibitors. Systemic agents include oral retinoids and methotrexate.

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that involves genetic and environmental factors, leading to abnormalities in the epidermis and the immune system presenting with its typical morphology and distribution. The morphology of eczematous lesions is distinct from papulosquamous lesions of psoriasis.

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is a toxin-mediated skin disorder which presents with denuded, peeling skin due to epidermolytic exotoxin producing Staphylococcus species. Fever, erythematous rash, malaise, skin pain, and irritability presents initially. Progressive desquamation with accentuation in folds is typical, with progression usually within 1-2 days. Systemic antibiotics covering Staphylococcus should be administered early. Emollients and nonadherent dressings should be applied to affected areas to promote healing. Supportive care includes dehydration management, temperature regulation, and nutrition. Skin desquamation usually occurs within 5 days with resolution within 2 weeks.

This infant displayed streptococcal intertrigo which triggered an early presentation of guttate psoriasis. The patient was managed with completion of a course of oral cephalexin, midstrength topical corticosteroids to the truncal lesions, and mild topical corticosteroids to the face and diaper area with good clinical response.

Danny Lee and Samuel Le serve as research fellows in the Pediatric Dermatology Division of the Department of Dermatology at the University of California San Diego and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is Distinguished Professor of Dermatology and Pediatrics and Vice-Chair of the Department of Dermatology at the University of California San Diego and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. The authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

Suggested Reading

Leung AK et al. Childhood guttate psoriasis: An updated review. Drugs Context. 2023 Oct 23:12:2023-8-2. doi: 10.7573/dic.2023-8-2.

Galili E et al. New-onset guttate psoriasis: A long-term follow-up study. Dermatology. 2023;239(2):188-194. doi: 10.1159/000527737.

Duffin KC et al. Advances and controversies in our understanding of guttate and plaque psoriasis. J Rheumatol. 2023 Nov;50(Suppl 2):4-7. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.2023-0500.

Saleh D, Tanner LS. Guttate Psoriasis. [Updated 2023 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482498/

Dupire G et al. Antistreptococcal interventions for guttate and chronic plaque psoriasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Mar 5;3(3):CD011571. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011571.pub2.

Diagnosis: Infection-induced psoriasis (guttate-type, induced by streptococcal intertrigo)

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disorder characterized by well-defined, scaly, erythematous plaques. Guttate psoriasis is a distinct variant of psoriasis that is more common in children and adolescents. Guttate psoriasis usually presents with multiple, scattered, small, drop-like (“guttate”), scaly, erythematous papules and plaques.

The pathophysiology of psoriasis involves an interplay between genetic and environmental factors. Guttate psoriasis is a chronic T-cell–mediated inflammatory disease in which there is an altered balance between T-helper-1 (TH1) and TH2 cells, transcription factor genes, and their products. HLA B-13, B-17, and Cw6 are human leukocyte antigen alleles implicated in genetic susceptibility. It is hypothesized that streptococcal infection precipitates guttate psoriasis by streptococcal superantigen–driven activation of cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen (CLA)–positive lymphocytes. It has been shown that streptococcal exotoxins and streptococcal M proteins act as superantigens.

Diagnosis is often made clinically based on characteristic physical findings and a possible preceding history of streptococcal infection. In patients with streptococcal infection, culture from an appropriate site and measurement of serum antistreptococcal antibody titers (for example, anti-DNase, antihyaluronidase and antistreptolysin-O) can help. A skin biopsy is usually not necessary but may be considered.

This patient presented with intertrigo of the neck and axillae at the time of presentation with the papulosquamous rash. Culture of the intertrigo yielded 4+ Group A beta streptococcus.

Treatment

Although there is currently no cure for guttate psoriasis, various treatment options can relieve symptoms and clear skin lesions, and infection-triggered lesions may remit, usually within several months. However, guttate psoriasis may persist and progress to chronic plaque psoriasis. Many treatment options are based mainly on clinical trials targeted for plaque psoriasis treatment.

For mild psoriasis, topical corticosteroids are first-line treatment. Other topical steroids include vitamin D analogs (calcipotriene), topical retinoids (tazarotene), topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus), and newer non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (roflumilast or tapinarof), neither approved yet in this young age group. In more severe cases, phototherapy with UVB light, traditional systemic immunosuppressive agents (methotrexate, cyclosporine) or targeted biologic therapies may be considered.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis may include generalized intertrigo, pityriasis rubra pilaris, tinea corporis, atopic dermatitis, and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Guttate psoriasis can be distinguished by history and physical exam. Further studies such as potassium hydroxide (KOH) scrapings may be helpful in ruling out the other disorders.

Intertrigo is an inflammatory condition of the flexural surfaces irritated by warm temperatures, friction, moisture, and poor ventilation that is commonly associated with Candida infection and/or streptococcal infection. Candidal intertrigo can present with erythematous patches or plaques in an intertriginous area that may develop erosions, macerations, fissures, crust, and weeping. Satellite papules and pustules are pathognomonic for Candida species. Streptococcal intertrigo usually presents with bright red color and may be painful or pruritic. Perianal streptococcal infection is reported as a trigger of guttate psoriasis in pediatric patients.

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a rare inflammatory papulosquamous disorder with an unknown etiology. Red-orange papules and plaques, hyperkeratotic follicular papules, and palmoplantar hyperkeratosis are primary features. Diagnosis is based on clinical and histopathology. Pityriasis rubra pilaris is self-limited and asymptomatic in many cases. Treatment may not be required, but combination therapy with topical agents includes emollients, keratolytic agents (for example, urea, salicylic acid, alpha-hydroxy acids), topical corticosteroids, tazarotene, and topical calcineurin inhibitors. Systemic agents include oral retinoids and methotrexate.

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that involves genetic and environmental factors, leading to abnormalities in the epidermis and the immune system presenting with its typical morphology and distribution. The morphology of eczematous lesions is distinct from papulosquamous lesions of psoriasis.

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is a toxin-mediated skin disorder which presents with denuded, peeling skin due to epidermolytic exotoxin producing Staphylococcus species. Fever, erythematous rash, malaise, skin pain, and irritability presents initially. Progressive desquamation with accentuation in folds is typical, with progression usually within 1-2 days. Systemic antibiotics covering Staphylococcus should be administered early. Emollients and nonadherent dressings should be applied to affected areas to promote healing. Supportive care includes dehydration management, temperature regulation, and nutrition. Skin desquamation usually occurs within 5 days with resolution within 2 weeks.

This infant displayed streptococcal intertrigo which triggered an early presentation of guttate psoriasis. The patient was managed with completion of a course of oral cephalexin, midstrength topical corticosteroids to the truncal lesions, and mild topical corticosteroids to the face and diaper area with good clinical response.

Danny Lee and Samuel Le serve as research fellows in the Pediatric Dermatology Division of the Department of Dermatology at the University of California San Diego and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is Distinguished Professor of Dermatology and Pediatrics and Vice-Chair of the Department of Dermatology at the University of California San Diego and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. The authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

Suggested Reading

Leung AK et al. Childhood guttate psoriasis: An updated review. Drugs Context. 2023 Oct 23:12:2023-8-2. doi: 10.7573/dic.2023-8-2.

Galili E et al. New-onset guttate psoriasis: A long-term follow-up study. Dermatology. 2023;239(2):188-194. doi: 10.1159/000527737.

Duffin KC et al. Advances and controversies in our understanding of guttate and plaque psoriasis. J Rheumatol. 2023 Nov;50(Suppl 2):4-7. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.2023-0500.

Saleh D, Tanner LS. Guttate Psoriasis. [Updated 2023 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482498/

Dupire G et al. Antistreptococcal interventions for guttate and chronic plaque psoriasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Mar 5;3(3):CD011571. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011571.pub2.

On physical exam, there was an erythematous patch with overlying areas of macerations on the neck and axilla. The trunk, extremities, and diaper area had multiple psoriasiform erythematous thin plaques with overlying scales.

What is the diagnosis?

Answer: A

Pityriasis alba is a common benign skin disorder that presents as hypopigmented skin most noticeable in darker skin types. It presents as whitish or mildly erythematous patches, commonly on the face, though it can appear on the trunk and extremities as well. It is estimated that about 1% of the general population is affected and may be more common after months with more extended sun exposure.

While a specific cause has not been identified, it is thought to represent post-inflammatory hypopigmentation, and is thought by many experts to be more common in atopic individuals; it is considered a minor clinical criterion for atopic dermatitis. The name relates to its appearance at times being scaly (pityriasis) and its whitish coloration (alba) and may represent a non-specific dermatitis.

It occurs predominantly in children and adolescents, and a slight male predominance has been noted. Even though this condition is not seasonal, the lesions become more obvious in the spring and summer because of sun exposure and darkening of the surrounding normal skin.

Physical examination reveals multiple round or oval shaped hypopigmented poorly defined macules, patches, or thin plaques. Mild scaling may be present. The number of lesions is variable. The most common presentation is asymptomatic, although some patients report mild pruritus. Two infrequent variants have been reported. Pigmented pityriasis is mostly reported in patients with darker skin in South Africa and the Middle East and presents with hyperpigmented bluish patches surrounded by a hypopigmented ring. Extensive pityriasis alba is another uncommon variant, characterized by widespread symmetrical lesions distributed predominantly on the trunk. Seborrheic dermatitis presents as a mild form of dandruff, often with asymptomatic or mildly itchy scalp with scaling, though involvement of the face can be seen around the eyebrows, glabella, and nasolabial areas.

Less common conditions in the differential diagnosis include other inflammatory conditions (contact dermatitis, psoriasis), genodermatoses (such as ash-leaf macules of tuberous sclerosis), infectious diseases (leprosy, and tinea corporis or faciei) and nevoid conditions (such as nevus anemicus). Leprosy is tremendously rare in children in the United States and can present as sharply demarcated usually elevated plaques often with diminished sensation. Hypopigmentation secondary to topical medications or skin procedures should also be considered. When encountering chronic, refractory, or extensive cases, an alarm for pityriasis lichenoides chronica and cutaneous lymphoma (hypopigmented mycosis fungoides) might be considered.

Pityriasis alba is a self-limited condition with a good prognosis and expected complete resolution, most commonly within 1 year. Patients and their parents should be educated regarding the benign and self-limited nature of pityriasis alba. Affected areas should be sun-protected to avoid worsening of the cosmetic appearance and prevent sunburn in the hypopigmented areas. The frequent use of emollients is the mainstay of treatment. Some topical treatments may reduce erythema and pruritus and accelerate repigmentation. Low-potency topical steroids, such as 1% hydrocortisone, are an alternative treatment, especially when itchiness is present. Topical calcineurin inhibitors such as 0.1% tacrolimus or 1% pimecrolimus have also been reported to be effective, as well as topical vitamin D derivatives (calcitriol and calcipotriol).

Suggested reading

1. Treat: Abdel-Wahab HM and Ragaie MH. Pityriasis alba: Toward an effective treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022 Jun;33(4):2285-9. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2021.1959014. Epub 2021 Aug 1.

2. PEARLS: Givler DN et al. Pityriasis alba. 2023 Feb 19. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

3. Choi SH et al. Pityriasis alba in pediatric patients with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023 Apr 1;22(4):417-8. doi: 10.36849/JDD.7221.

4. Gawai SR et al. Association of pityriasis alba with atopic dermatitis: A cross-sectional study. Indian J Dermatol. 2021 Sep-Oct;66(5):567-8. doi: 10.4103/ijd.ijd_936_20.

Dr. Guelfand is a visiting dermatology resident in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego. Dr. Vuong is a clinical fellow in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and distinguished professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. No author has any relevant financial disclosures.

Answer: A

Pityriasis alba is a common benign skin disorder that presents as hypopigmented skin most noticeable in darker skin types. It presents as whitish or mildly erythematous patches, commonly on the face, though it can appear on the trunk and extremities as well. It is estimated that about 1% of the general population is affected and may be more common after months with more extended sun exposure.

While a specific cause has not been identified, it is thought to represent post-inflammatory hypopigmentation, and is thought by many experts to be more common in atopic individuals; it is considered a minor clinical criterion for atopic dermatitis. The name relates to its appearance at times being scaly (pityriasis) and its whitish coloration (alba) and may represent a non-specific dermatitis.

It occurs predominantly in children and adolescents, and a slight male predominance has been noted. Even though this condition is not seasonal, the lesions become more obvious in the spring and summer because of sun exposure and darkening of the surrounding normal skin.

Physical examination reveals multiple round or oval shaped hypopigmented poorly defined macules, patches, or thin plaques. Mild scaling may be present. The number of lesions is variable. The most common presentation is asymptomatic, although some patients report mild pruritus. Two infrequent variants have been reported. Pigmented pityriasis is mostly reported in patients with darker skin in South Africa and the Middle East and presents with hyperpigmented bluish patches surrounded by a hypopigmented ring. Extensive pityriasis alba is another uncommon variant, characterized by widespread symmetrical lesions distributed predominantly on the trunk. Seborrheic dermatitis presents as a mild form of dandruff, often with asymptomatic or mildly itchy scalp with scaling, though involvement of the face can be seen around the eyebrows, glabella, and nasolabial areas.

Less common conditions in the differential diagnosis include other inflammatory conditions (contact dermatitis, psoriasis), genodermatoses (such as ash-leaf macules of tuberous sclerosis), infectious diseases (leprosy, and tinea corporis or faciei) and nevoid conditions (such as nevus anemicus). Leprosy is tremendously rare in children in the United States and can present as sharply demarcated usually elevated plaques often with diminished sensation. Hypopigmentation secondary to topical medications or skin procedures should also be considered. When encountering chronic, refractory, or extensive cases, an alarm for pityriasis lichenoides chronica and cutaneous lymphoma (hypopigmented mycosis fungoides) might be considered.

Pityriasis alba is a self-limited condition with a good prognosis and expected complete resolution, most commonly within 1 year. Patients and their parents should be educated regarding the benign and self-limited nature of pityriasis alba. Affected areas should be sun-protected to avoid worsening of the cosmetic appearance and prevent sunburn in the hypopigmented areas. The frequent use of emollients is the mainstay of treatment. Some topical treatments may reduce erythema and pruritus and accelerate repigmentation. Low-potency topical steroids, such as 1% hydrocortisone, are an alternative treatment, especially when itchiness is present. Topical calcineurin inhibitors such as 0.1% tacrolimus or 1% pimecrolimus have also been reported to be effective, as well as topical vitamin D derivatives (calcitriol and calcipotriol).

Suggested reading

1. Treat: Abdel-Wahab HM and Ragaie MH. Pityriasis alba: Toward an effective treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022 Jun;33(4):2285-9. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2021.1959014. Epub 2021 Aug 1.

2. PEARLS: Givler DN et al. Pityriasis alba. 2023 Feb 19. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

3. Choi SH et al. Pityriasis alba in pediatric patients with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023 Apr 1;22(4):417-8. doi: 10.36849/JDD.7221.

4. Gawai SR et al. Association of pityriasis alba with atopic dermatitis: A cross-sectional study. Indian J Dermatol. 2021 Sep-Oct;66(5):567-8. doi: 10.4103/ijd.ijd_936_20.

Dr. Guelfand is a visiting dermatology resident in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego. Dr. Vuong is a clinical fellow in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and distinguished professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. No author has any relevant financial disclosures.

Answer: A

Pityriasis alba is a common benign skin disorder that presents as hypopigmented skin most noticeable in darker skin types. It presents as whitish or mildly erythematous patches, commonly on the face, though it can appear on the trunk and extremities as well. It is estimated that about 1% of the general population is affected and may be more common after months with more extended sun exposure.

While a specific cause has not been identified, it is thought to represent post-inflammatory hypopigmentation, and is thought by many experts to be more common in atopic individuals; it is considered a minor clinical criterion for atopic dermatitis. The name relates to its appearance at times being scaly (pityriasis) and its whitish coloration (alba) and may represent a non-specific dermatitis.

It occurs predominantly in children and adolescents, and a slight male predominance has been noted. Even though this condition is not seasonal, the lesions become more obvious in the spring and summer because of sun exposure and darkening of the surrounding normal skin.

Physical examination reveals multiple round or oval shaped hypopigmented poorly defined macules, patches, or thin plaques. Mild scaling may be present. The number of lesions is variable. The most common presentation is asymptomatic, although some patients report mild pruritus. Two infrequent variants have been reported. Pigmented pityriasis is mostly reported in patients with darker skin in South Africa and the Middle East and presents with hyperpigmented bluish patches surrounded by a hypopigmented ring. Extensive pityriasis alba is another uncommon variant, characterized by widespread symmetrical lesions distributed predominantly on the trunk. Seborrheic dermatitis presents as a mild form of dandruff, often with asymptomatic or mildly itchy scalp with scaling, though involvement of the face can be seen around the eyebrows, glabella, and nasolabial areas.

Less common conditions in the differential diagnosis include other inflammatory conditions (contact dermatitis, psoriasis), genodermatoses (such as ash-leaf macules of tuberous sclerosis), infectious diseases (leprosy, and tinea corporis or faciei) and nevoid conditions (such as nevus anemicus). Leprosy is tremendously rare in children in the United States and can present as sharply demarcated usually elevated plaques often with diminished sensation. Hypopigmentation secondary to topical medications or skin procedures should also be considered. When encountering chronic, refractory, or extensive cases, an alarm for pityriasis lichenoides chronica and cutaneous lymphoma (hypopigmented mycosis fungoides) might be considered.

Pityriasis alba is a self-limited condition with a good prognosis and expected complete resolution, most commonly within 1 year. Patients and their parents should be educated regarding the benign and self-limited nature of pityriasis alba. Affected areas should be sun-protected to avoid worsening of the cosmetic appearance and prevent sunburn in the hypopigmented areas. The frequent use of emollients is the mainstay of treatment. Some topical treatments may reduce erythema and pruritus and accelerate repigmentation. Low-potency topical steroids, such as 1% hydrocortisone, are an alternative treatment, especially when itchiness is present. Topical calcineurin inhibitors such as 0.1% tacrolimus or 1% pimecrolimus have also been reported to be effective, as well as topical vitamin D derivatives (calcitriol and calcipotriol).

Suggested reading

1. Treat: Abdel-Wahab HM and Ragaie MH. Pityriasis alba: Toward an effective treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022 Jun;33(4):2285-9. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2021.1959014. Epub 2021 Aug 1.

2. PEARLS: Givler DN et al. Pityriasis alba. 2023 Feb 19. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

3. Choi SH et al. Pityriasis alba in pediatric patients with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023 Apr 1;22(4):417-8. doi: 10.36849/JDD.7221.

4. Gawai SR et al. Association of pityriasis alba with atopic dermatitis: A cross-sectional study. Indian J Dermatol. 2021 Sep-Oct;66(5):567-8. doi: 10.4103/ijd.ijd_936_20.

Dr. Guelfand is a visiting dermatology resident in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego. Dr. Vuong is a clinical fellow in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and distinguished professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. No author has any relevant financial disclosures.

The lesions were asymptomatic, and the review of systems was otherwise negative.

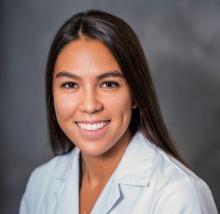

Physical examination revealed multiple poorly defined thin hypopigmented patches with a bilateral distribution, mostly on the cheeks.

The patches had focal superficial nonadherent thin white scales and were mildly rough to the touch. The rest of the physical exam was unremarkable, including no active eczematous lesions on the trunk or extremities.

What's the diagnosis?

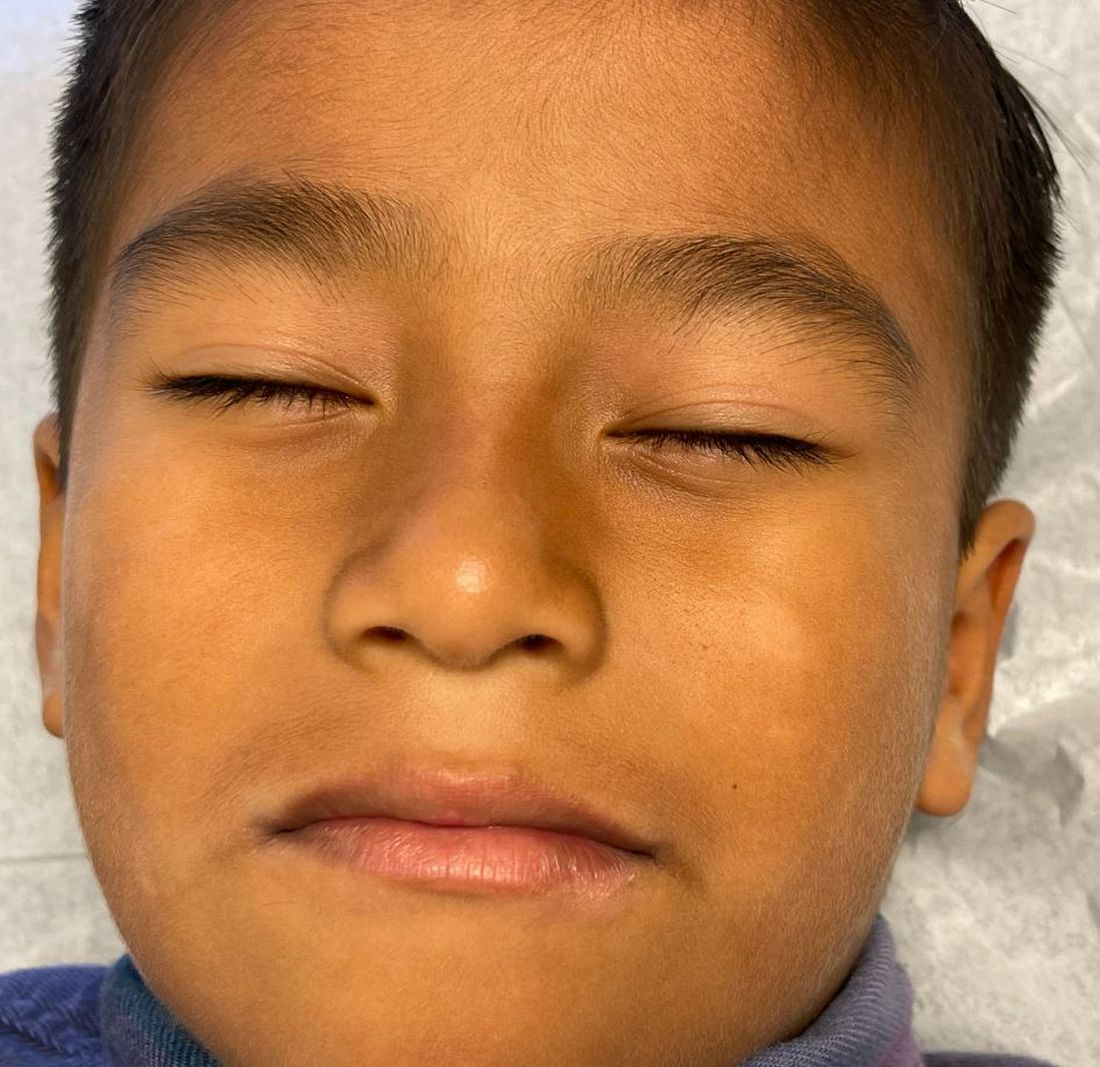

Given the characteristic clinical presentation, the most likely diagnosis is pilomatrixoma.

Pilomatrixomas are benign adnexal tumors that arise from immature matrix cells of the hair follicles located on dermal or subcutaneous tissue.

The cause of pilomatrixoma remains unclear. Recent studies have suggested that the development of pilomatrixoma are related to mutations in the Wnt signaling pathway, where beta-catenin gene (CTNNB1) mutation is the most frequently reported.1-4

Pilomatrixomas are more common in children and often present before 10 years of age.1,2,5 They commonly appear in head and neck, as well as upper extremities, trunk, and lower extremities.2,6

The clinical manifestations of pilomatrixomas are diverse and according to their appearance five classic clinical types are described: mass, pigmented, mixed, ulcerated, and keloid-like.2,3 The mass type is the predominant form, where it generally presents as a hard and freely mobile nodule covered by skin that may present a firm calcified protruding nodule. Other less common types include: lymphangiectasic, anetodermic, perforating, and bullous.2,6,7

Pilomatrixomas are mostly solitary, whereas multiple forms are reported to be associated with familial inheritance or syndromic conditions, such as myotonic dystrophy, Gardner syndrome, Turner’s syndrome, and Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome.2-4 However, children and adolescents occasionally present with multiple pilomatricomas with no associated syndrome.

On physical exam a helpful features for the diagnosis is the “teeter-totter sign,” which can be illustrated by pressing on one edge of the lesion that will cause the opposite edge to protrude from the skin. Another helpful tool is to use a light to transilluminate and the calcification produces a bluish opaque hue,8 as light cannot transmit through the calcification, often differentiating it from epidermal inclusion cysts or other noncalcified lesions.

What is the differential diagnosis?

Because of the diverse clinical presentations, pilomatrixomas are frequently misdiagnosed. The percentage of correct preoperative diagnosis reported is low, varying from 16% to 43% in different series.1,9-11 They most frequently are misdiagnosed as other types of cysts such as epidermal, dermoid, or sebaceous.2,3,5,12,13 Rapidly growing pilomatrixomas can be also be misdiagnosed as malignant soft-tissue tumors, cutaneous lymphoma, or sarcomas.5,13

When presenting with a classic history and physical features, diagnosis is clinical, and no further studies are recommended.14 To improve diagnostic accuracy when encountering unusual subtypes, imaging is recommended, including ultrasound. Ultrasound adds a high positive predictive value (95.56%).2 Generally, on ultrasound a pilomatrixoma is described as an oval, well-defined, heterogeneous, hyperechoic subcutaneous mass with or without posterior shadowing.2 The definitive diagnosis is, however, made by histopathologic examination.

Pilomatrixomas do not spontaneously regress, therefore complete surgical resection is the standard treatment. During the follow-up period, very low recurrence rates have been reported, varying from 1.5% to 2% which generally occurs because of incomplete resection.2,3

Plexiform neurofibromas are usually congenital tumors of peripheral nerve sheath associated with neurofibromatosis type 1, often with a “bag of worms” feel on palpation. Epidermoid cysts generally present as dermal nodules often with a visible puncture, mobile on soft and mobile on palpation. Dermatofibromas present as firm, usually hyperpigmented papule or nodules that are fixed to subcutaneous tissue, thus often “dimpling” when pitched. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare soft-tissue sarcoma which presents as a firm, slow growing indurated plaques growing over months to years.

Conclusion

Pilomatrixomas are a benign adnexal tumor that sometimes can present as atypical forms such as this case. Diagnosis is usually based on clinical diagnosis, and transillumination can be a bedside clue. When the clinical diagnosis remains obscure an ultrasound can be helpful. The main aim of this case is to improve awareness of the variable presentations of pilomatrixomas and the importance of high level of suspicion supported by careful clinical evaluation.

Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Al-Nabti is a clinical fellow in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego. Dr. Guelfand is a visiting dermatology resident in the division of pediaric and adolescent dermatology, University of Califonia, San Diego.

References

1. Jones CD et al. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:631-41.

2. Hu JL et al. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2020;21(5):288-93.

3. Adhikari G and Jadhav GS. Cureus. 2022;14(2):22228.

4. Cóbar JP et al. J Surg Case Rep. 2023;2023(4):rjad182.

5. Schwarz Y et al. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;85:148-53.

6. Kose D et al. J Cancer Res Ther. 2014;10(3):549-51.

7. Sabater-Abad J et al. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26(8):13030/qt4h16s45w.

8. Alkatan HM et al. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2021;84:106068.

9. Pant I et al. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:390-2.

10. Kaddu S et al. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18(4):333-8

11. Schwarz Y et al. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;85:148-53.

12. Wang YN et al. Chin Med J (Engl). 2021;134(16):2011-2.

13. Yannoutsos A et al. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40(9):690-3.

14. Zhao A et al. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021;1455613211044778.

Given the characteristic clinical presentation, the most likely diagnosis is pilomatrixoma.

Pilomatrixomas are benign adnexal tumors that arise from immature matrix cells of the hair follicles located on dermal or subcutaneous tissue.

The cause of pilomatrixoma remains unclear. Recent studies have suggested that the development of pilomatrixoma are related to mutations in the Wnt signaling pathway, where beta-catenin gene (CTNNB1) mutation is the most frequently reported.1-4

Pilomatrixomas are more common in children and often present before 10 years of age.1,2,5 They commonly appear in head and neck, as well as upper extremities, trunk, and lower extremities.2,6

The clinical manifestations of pilomatrixomas are diverse and according to their appearance five classic clinical types are described: mass, pigmented, mixed, ulcerated, and keloid-like.2,3 The mass type is the predominant form, where it generally presents as a hard and freely mobile nodule covered by skin that may present a firm calcified protruding nodule. Other less common types include: lymphangiectasic, anetodermic, perforating, and bullous.2,6,7

Pilomatrixomas are mostly solitary, whereas multiple forms are reported to be associated with familial inheritance or syndromic conditions, such as myotonic dystrophy, Gardner syndrome, Turner’s syndrome, and Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome.2-4 However, children and adolescents occasionally present with multiple pilomatricomas with no associated syndrome.

On physical exam a helpful features for the diagnosis is the “teeter-totter sign,” which can be illustrated by pressing on one edge of the lesion that will cause the opposite edge to protrude from the skin. Another helpful tool is to use a light to transilluminate and the calcification produces a bluish opaque hue,8 as light cannot transmit through the calcification, often differentiating it from epidermal inclusion cysts or other noncalcified lesions.

What is the differential diagnosis?

Because of the diverse clinical presentations, pilomatrixomas are frequently misdiagnosed. The percentage of correct preoperative diagnosis reported is low, varying from 16% to 43% in different series.1,9-11 They most frequently are misdiagnosed as other types of cysts such as epidermal, dermoid, or sebaceous.2,3,5,12,13 Rapidly growing pilomatrixomas can be also be misdiagnosed as malignant soft-tissue tumors, cutaneous lymphoma, or sarcomas.5,13

When presenting with a classic history and physical features, diagnosis is clinical, and no further studies are recommended.14 To improve diagnostic accuracy when encountering unusual subtypes, imaging is recommended, including ultrasound. Ultrasound adds a high positive predictive value (95.56%).2 Generally, on ultrasound a pilomatrixoma is described as an oval, well-defined, heterogeneous, hyperechoic subcutaneous mass with or without posterior shadowing.2 The definitive diagnosis is, however, made by histopathologic examination.

Pilomatrixomas do not spontaneously regress, therefore complete surgical resection is the standard treatment. During the follow-up period, very low recurrence rates have been reported, varying from 1.5% to 2% which generally occurs because of incomplete resection.2,3

Plexiform neurofibromas are usually congenital tumors of peripheral nerve sheath associated with neurofibromatosis type 1, often with a “bag of worms” feel on palpation. Epidermoid cysts generally present as dermal nodules often with a visible puncture, mobile on soft and mobile on palpation. Dermatofibromas present as firm, usually hyperpigmented papule or nodules that are fixed to subcutaneous tissue, thus often “dimpling” when pitched. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare soft-tissue sarcoma which presents as a firm, slow growing indurated plaques growing over months to years.

Conclusion

Pilomatrixomas are a benign adnexal tumor that sometimes can present as atypical forms such as this case. Diagnosis is usually based on clinical diagnosis, and transillumination can be a bedside clue. When the clinical diagnosis remains obscure an ultrasound can be helpful. The main aim of this case is to improve awareness of the variable presentations of pilomatrixomas and the importance of high level of suspicion supported by careful clinical evaluation.

Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Al-Nabti is a clinical fellow in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego. Dr. Guelfand is a visiting dermatology resident in the division of pediaric and adolescent dermatology, University of Califonia, San Diego.

References

1. Jones CD et al. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:631-41.

2. Hu JL et al. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2020;21(5):288-93.

3. Adhikari G and Jadhav GS. Cureus. 2022;14(2):22228.

4. Cóbar JP et al. J Surg Case Rep. 2023;2023(4):rjad182.

5. Schwarz Y et al. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;85:148-53.

6. Kose D et al. J Cancer Res Ther. 2014;10(3):549-51.

7. Sabater-Abad J et al. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26(8):13030/qt4h16s45w.

8. Alkatan HM et al. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2021;84:106068.

9. Pant I et al. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:390-2.

10. Kaddu S et al. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18(4):333-8

11. Schwarz Y et al. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;85:148-53.

12. Wang YN et al. Chin Med J (Engl). 2021;134(16):2011-2.

13. Yannoutsos A et al. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40(9):690-3.

14. Zhao A et al. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021;1455613211044778.

Given the characteristic clinical presentation, the most likely diagnosis is pilomatrixoma.

Pilomatrixomas are benign adnexal tumors that arise from immature matrix cells of the hair follicles located on dermal or subcutaneous tissue.

The cause of pilomatrixoma remains unclear. Recent studies have suggested that the development of pilomatrixoma are related to mutations in the Wnt signaling pathway, where beta-catenin gene (CTNNB1) mutation is the most frequently reported.1-4

Pilomatrixomas are more common in children and often present before 10 years of age.1,2,5 They commonly appear in head and neck, as well as upper extremities, trunk, and lower extremities.2,6

The clinical manifestations of pilomatrixomas are diverse and according to their appearance five classic clinical types are described: mass, pigmented, mixed, ulcerated, and keloid-like.2,3 The mass type is the predominant form, where it generally presents as a hard and freely mobile nodule covered by skin that may present a firm calcified protruding nodule. Other less common types include: lymphangiectasic, anetodermic, perforating, and bullous.2,6,7

Pilomatrixomas are mostly solitary, whereas multiple forms are reported to be associated with familial inheritance or syndromic conditions, such as myotonic dystrophy, Gardner syndrome, Turner’s syndrome, and Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome.2-4 However, children and adolescents occasionally present with multiple pilomatricomas with no associated syndrome.

On physical exam a helpful features for the diagnosis is the “teeter-totter sign,” which can be illustrated by pressing on one edge of the lesion that will cause the opposite edge to protrude from the skin. Another helpful tool is to use a light to transilluminate and the calcification produces a bluish opaque hue,8 as light cannot transmit through the calcification, often differentiating it from epidermal inclusion cysts or other noncalcified lesions.

What is the differential diagnosis?

Because of the diverse clinical presentations, pilomatrixomas are frequently misdiagnosed. The percentage of correct preoperative diagnosis reported is low, varying from 16% to 43% in different series.1,9-11 They most frequently are misdiagnosed as other types of cysts such as epidermal, dermoid, or sebaceous.2,3,5,12,13 Rapidly growing pilomatrixomas can be also be misdiagnosed as malignant soft-tissue tumors, cutaneous lymphoma, or sarcomas.5,13

When presenting with a classic history and physical features, diagnosis is clinical, and no further studies are recommended.14 To improve diagnostic accuracy when encountering unusual subtypes, imaging is recommended, including ultrasound. Ultrasound adds a high positive predictive value (95.56%).2 Generally, on ultrasound a pilomatrixoma is described as an oval, well-defined, heterogeneous, hyperechoic subcutaneous mass with or without posterior shadowing.2 The definitive diagnosis is, however, made by histopathologic examination.

Pilomatrixomas do not spontaneously regress, therefore complete surgical resection is the standard treatment. During the follow-up period, very low recurrence rates have been reported, varying from 1.5% to 2% which generally occurs because of incomplete resection.2,3

Plexiform neurofibromas are usually congenital tumors of peripheral nerve sheath associated with neurofibromatosis type 1, often with a “bag of worms” feel on palpation. Epidermoid cysts generally present as dermal nodules often with a visible puncture, mobile on soft and mobile on palpation. Dermatofibromas present as firm, usually hyperpigmented papule or nodules that are fixed to subcutaneous tissue, thus often “dimpling” when pitched. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare soft-tissue sarcoma which presents as a firm, slow growing indurated plaques growing over months to years.

Conclusion

Pilomatrixomas are a benign adnexal tumor that sometimes can present as atypical forms such as this case. Diagnosis is usually based on clinical diagnosis, and transillumination can be a bedside clue. When the clinical diagnosis remains obscure an ultrasound can be helpful. The main aim of this case is to improve awareness of the variable presentations of pilomatrixomas and the importance of high level of suspicion supported by careful clinical evaluation.

Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Al-Nabti is a clinical fellow in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego. Dr. Guelfand is a visiting dermatology resident in the division of pediaric and adolescent dermatology, University of Califonia, San Diego.

References

1. Jones CD et al. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:631-41.

2. Hu JL et al. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2020;21(5):288-93.

3. Adhikari G and Jadhav GS. Cureus. 2022;14(2):22228.

4. Cóbar JP et al. J Surg Case Rep. 2023;2023(4):rjad182.

5. Schwarz Y et al. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;85:148-53.

6. Kose D et al. J Cancer Res Ther. 2014;10(3):549-51.

7. Sabater-Abad J et al. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26(8):13030/qt4h16s45w.

8. Alkatan HM et al. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2021;84:106068.

9. Pant I et al. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:390-2.

10. Kaddu S et al. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18(4):333-8

11. Schwarz Y et al. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;85:148-53.

12. Wang YN et al. Chin Med J (Engl). 2021;134(16):2011-2.

13. Yannoutsos A et al. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40(9):690-3.

14. Zhao A et al. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021;1455613211044778.

On physical exam there was a well-circumscribed skin-colored nodule measuring 3.1 x 3 cm that was tender on palpation. The nodule was mobile, with a firm, stony feel, and no punctum was visualized. Transillumination revealed a subtle bluish hue within the nodule.

A toddler presents with a dark line on a fingernail

Given the over 1-year history of an unchanging longitudinal band of pigment without extension to the proximal or lateral nailfolds or any other nail findings, the most likely diagnosis is benign longitudinal melanonychia.

Longitudinal melanonychia, also known as melanonychia striata, describes a brown to black streak of pigment extending from the nail matrix to the free edge of the nail.1,2

This disorder can occur secondary to a wide variety of benign and pathologic causes including lentigines, nevi, melanoma, chronic trauma, inflammatory skin diseases, systemic diseases, iatrogenic causes, and genetic syndromes.3 In melanocytic causes of longitudinal melanonychia, either melanocytic activation or hyperplasia drive pigmentary development leading to the brown to black band seen in the nail.4 Benign causes of longitudinal melanonychia include benign melanocyte activation, lentigo, and benign nevus.1

What’s the differential diagnosis?

The differential diagnosis for longitudinal melanonychia can include a wide variety of local and systemic causes. For our discussion, we will limit our differential to other locally involved disorders of the nail including subungual melanoma, subungual hematoma, onychomycosis, and glomus tumor.

Subungual melanoma is a rare subtype of acral lentiginous melanoma that most often presents as longitudinal melanonychia. Subungual melanoma is more common in those aged 50-70 years, individuals with personal or family history of melanoma or dysplastic nevus syndrome, and persons with African American, Native American, and Asian descent. Longitudinal melanonychia features that can be concerning for subungual melanoma include the presence of multiple colors, width greater than or equal to 3 mm, blurry borders, rapid increase in size, and extension to the proximal or lateral nailfolds (Hutchinson’s sign). Biopsy is required to make the diagnosis of subungual melanoma but is not necessary for melanonychia without atypical features.

Treatment of subungual melanoma depends on disease stage and can range from wide local excision of the nail apparatus to amputation of the affected digit and management with a medical oncologist. Given the absence of concerning neoplastic findings or personal or family history of melanoma, subungual melanoma is unlikely in this patient.

Subungual hematoma is an accumulation of blood underneath the nail plate that is typically the result of acute or chronic trauma to the distal phalanx. It can present as purple, red, pink, brown, or black discoloration under the nail plate and is most commonly found on the first toe. With acute trauma, pain is usually present upon initial injury. Subungual hematomas typically resolve on their own with normal nail growth. The absence of a history of trauma or pain, and the linear appearance of the lesion in our patient are inconsistent with a subungual hematoma.

Onychomycosis is a fungal infection of the nail caused by dermatophytes, nondermatophytes, or yeasts. It may present with longitudinal melanonychia; however, it more often presents with other nail abnormalities such as nail thickening, yellow discoloration, onycholysis, splitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, and nail plate destruction, which are not present in this patient. Furthermore, onychomycosis is more common in adults than children. Diagnosis is usually made with potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations, histopathologic examination of nail clippings with a periodic acid-Schiff stain, fungal culture, or PCR.

Glomus tumor is a rare, benign neoplasm originating from cells of the glomus body. It is often found in the subungual region, in addition to other areas rich in glomus bodies such as the fingertips, palms, wrists, and forearms. Subungual glomus tumors present as a red, purple, or blueish lesions under the nail plate. Distal notching or an overlying longitudinal fissure may be present. Subungual glomus tumors are typically associated with pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold sensitivity, features that are not present in our patient. The history and examination of our patient are much more consistent with benign longitudinal melanonychia.

It appears that melanoma associated with longitudinal melanonychia is very rare in children. According to one review published in 2020, only 12 cases of pediatric subungual melanoma have been reported.5 Recent series have observed longitudinal melanonychia in large sets of children, with findings that demonstrate that the vast majority of longitudinal melanonychia either stops progressing or regresses. These investigations therefore recommend serial observation of longitudinal melanonychia except in rare circumstances.6,7

Given the lack of troubling findings or concerning history, our patient was managed with observation. On follow-up 6 months later, he was found to have no change in his nail pigmentation.

Dr. Haft is an inflammatory skin disease fellow in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology; Ms. Sui is a research associate in the department of dermatology, division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology; and Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics, all at the University of California and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. They have no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Mannava KA et al. Hand Surg. 2013;18(1):133-9.

2. Leung AKC et al. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58(11):1239-45.

3. Andre J and Lateur N. Dermatol Clin. 2006;24(3):329-39.

4. Lee DK and Lipner SR. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):694-712.

5. Smith RJ and Rubin AI. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2020;32(4):506-15. .

6. Matsui Y et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(4):946-8.

7. Lee JS et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87(2):366-72.

Given the over 1-year history of an unchanging longitudinal band of pigment without extension to the proximal or lateral nailfolds or any other nail findings, the most likely diagnosis is benign longitudinal melanonychia.

Longitudinal melanonychia, also known as melanonychia striata, describes a brown to black streak of pigment extending from the nail matrix to the free edge of the nail.1,2

This disorder can occur secondary to a wide variety of benign and pathologic causes including lentigines, nevi, melanoma, chronic trauma, inflammatory skin diseases, systemic diseases, iatrogenic causes, and genetic syndromes.3 In melanocytic causes of longitudinal melanonychia, either melanocytic activation or hyperplasia drive pigmentary development leading to the brown to black band seen in the nail.4 Benign causes of longitudinal melanonychia include benign melanocyte activation, lentigo, and benign nevus.1

What’s the differential diagnosis?

The differential diagnosis for longitudinal melanonychia can include a wide variety of local and systemic causes. For our discussion, we will limit our differential to other locally involved disorders of the nail including subungual melanoma, subungual hematoma, onychomycosis, and glomus tumor.

Subungual melanoma is a rare subtype of acral lentiginous melanoma that most often presents as longitudinal melanonychia. Subungual melanoma is more common in those aged 50-70 years, individuals with personal or family history of melanoma or dysplastic nevus syndrome, and persons with African American, Native American, and Asian descent. Longitudinal melanonychia features that can be concerning for subungual melanoma include the presence of multiple colors, width greater than or equal to 3 mm, blurry borders, rapid increase in size, and extension to the proximal or lateral nailfolds (Hutchinson’s sign). Biopsy is required to make the diagnosis of subungual melanoma but is not necessary for melanonychia without atypical features.

Treatment of subungual melanoma depends on disease stage and can range from wide local excision of the nail apparatus to amputation of the affected digit and management with a medical oncologist. Given the absence of concerning neoplastic findings or personal or family history of melanoma, subungual melanoma is unlikely in this patient.

Subungual hematoma is an accumulation of blood underneath the nail plate that is typically the result of acute or chronic trauma to the distal phalanx. It can present as purple, red, pink, brown, or black discoloration under the nail plate and is most commonly found on the first toe. With acute trauma, pain is usually present upon initial injury. Subungual hematomas typically resolve on their own with normal nail growth. The absence of a history of trauma or pain, and the linear appearance of the lesion in our patient are inconsistent with a subungual hematoma.

Onychomycosis is a fungal infection of the nail caused by dermatophytes, nondermatophytes, or yeasts. It may present with longitudinal melanonychia; however, it more often presents with other nail abnormalities such as nail thickening, yellow discoloration, onycholysis, splitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, and nail plate destruction, which are not present in this patient. Furthermore, onychomycosis is more common in adults than children. Diagnosis is usually made with potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations, histopathologic examination of nail clippings with a periodic acid-Schiff stain, fungal culture, or PCR.

Glomus tumor is a rare, benign neoplasm originating from cells of the glomus body. It is often found in the subungual region, in addition to other areas rich in glomus bodies such as the fingertips, palms, wrists, and forearms. Subungual glomus tumors present as a red, purple, or blueish lesions under the nail plate. Distal notching or an overlying longitudinal fissure may be present. Subungual glomus tumors are typically associated with pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold sensitivity, features that are not present in our patient. The history and examination of our patient are much more consistent with benign longitudinal melanonychia.

It appears that melanoma associated with longitudinal melanonychia is very rare in children. According to one review published in 2020, only 12 cases of pediatric subungual melanoma have been reported.5 Recent series have observed longitudinal melanonychia in large sets of children, with findings that demonstrate that the vast majority of longitudinal melanonychia either stops progressing or regresses. These investigations therefore recommend serial observation of longitudinal melanonychia except in rare circumstances.6,7

Given the lack of troubling findings or concerning history, our patient was managed with observation. On follow-up 6 months later, he was found to have no change in his nail pigmentation.

Dr. Haft is an inflammatory skin disease fellow in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology; Ms. Sui is a research associate in the department of dermatology, division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology; and Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics, all at the University of California and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. They have no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Mannava KA et al. Hand Surg. 2013;18(1):133-9.

2. Leung AKC et al. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58(11):1239-45.

3. Andre J and Lateur N. Dermatol Clin. 2006;24(3):329-39.

4. Lee DK and Lipner SR. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):694-712.

5. Smith RJ and Rubin AI. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2020;32(4):506-15. .

6. Matsui Y et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(4):946-8.

7. Lee JS et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87(2):366-72.

Given the over 1-year history of an unchanging longitudinal band of pigment without extension to the proximal or lateral nailfolds or any other nail findings, the most likely diagnosis is benign longitudinal melanonychia.

Longitudinal melanonychia, also known as melanonychia striata, describes a brown to black streak of pigment extending from the nail matrix to the free edge of the nail.1,2

This disorder can occur secondary to a wide variety of benign and pathologic causes including lentigines, nevi, melanoma, chronic trauma, inflammatory skin diseases, systemic diseases, iatrogenic causes, and genetic syndromes.3 In melanocytic causes of longitudinal melanonychia, either melanocytic activation or hyperplasia drive pigmentary development leading to the brown to black band seen in the nail.4 Benign causes of longitudinal melanonychia include benign melanocyte activation, lentigo, and benign nevus.1

What’s the differential diagnosis?

The differential diagnosis for longitudinal melanonychia can include a wide variety of local and systemic causes. For our discussion, we will limit our differential to other locally involved disorders of the nail including subungual melanoma, subungual hematoma, onychomycosis, and glomus tumor.

Subungual melanoma is a rare subtype of acral lentiginous melanoma that most often presents as longitudinal melanonychia. Subungual melanoma is more common in those aged 50-70 years, individuals with personal or family history of melanoma or dysplastic nevus syndrome, and persons with African American, Native American, and Asian descent. Longitudinal melanonychia features that can be concerning for subungual melanoma include the presence of multiple colors, width greater than or equal to 3 mm, blurry borders, rapid increase in size, and extension to the proximal or lateral nailfolds (Hutchinson’s sign). Biopsy is required to make the diagnosis of subungual melanoma but is not necessary for melanonychia without atypical features.

Treatment of subungual melanoma depends on disease stage and can range from wide local excision of the nail apparatus to amputation of the affected digit and management with a medical oncologist. Given the absence of concerning neoplastic findings or personal or family history of melanoma, subungual melanoma is unlikely in this patient.

Subungual hematoma is an accumulation of blood underneath the nail plate that is typically the result of acute or chronic trauma to the distal phalanx. It can present as purple, red, pink, brown, or black discoloration under the nail plate and is most commonly found on the first toe. With acute trauma, pain is usually present upon initial injury. Subungual hematomas typically resolve on their own with normal nail growth. The absence of a history of trauma or pain, and the linear appearance of the lesion in our patient are inconsistent with a subungual hematoma.

Onychomycosis is a fungal infection of the nail caused by dermatophytes, nondermatophytes, or yeasts. It may present with longitudinal melanonychia; however, it more often presents with other nail abnormalities such as nail thickening, yellow discoloration, onycholysis, splitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, and nail plate destruction, which are not present in this patient. Furthermore, onychomycosis is more common in adults than children. Diagnosis is usually made with potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations, histopathologic examination of nail clippings with a periodic acid-Schiff stain, fungal culture, or PCR.

Glomus tumor is a rare, benign neoplasm originating from cells of the glomus body. It is often found in the subungual region, in addition to other areas rich in glomus bodies such as the fingertips, palms, wrists, and forearms. Subungual glomus tumors present as a red, purple, or blueish lesions under the nail plate. Distal notching or an overlying longitudinal fissure may be present. Subungual glomus tumors are typically associated with pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold sensitivity, features that are not present in our patient. The history and examination of our patient are much more consistent with benign longitudinal melanonychia.

It appears that melanoma associated with longitudinal melanonychia is very rare in children. According to one review published in 2020, only 12 cases of pediatric subungual melanoma have been reported.5 Recent series have observed longitudinal melanonychia in large sets of children, with findings that demonstrate that the vast majority of longitudinal melanonychia either stops progressing or regresses. These investigations therefore recommend serial observation of longitudinal melanonychia except in rare circumstances.6,7

Given the lack of troubling findings or concerning history, our patient was managed with observation. On follow-up 6 months later, he was found to have no change in his nail pigmentation.

Dr. Haft is an inflammatory skin disease fellow in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology; Ms. Sui is a research associate in the department of dermatology, division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology; and Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics, all at the University of California and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. They have no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Mannava KA et al. Hand Surg. 2013;18(1):133-9.

2. Leung AKC et al. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58(11):1239-45.

3. Andre J and Lateur N. Dermatol Clin. 2006;24(3):329-39.

4. Lee DK and Lipner SR. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):694-712.

5. Smith RJ and Rubin AI. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2020;32(4):506-15. .

6. Matsui Y et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(4):946-8.

7. Lee JS et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87(2):366-72.

Examination findings reveal a 2-mm brown longitudinal band on the radial aspect of the right thumbnail that does not extend into the proximal or lateral nailfolds. The rest of the skin and nail exam is unremarkable.

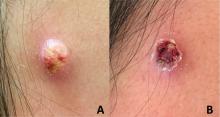

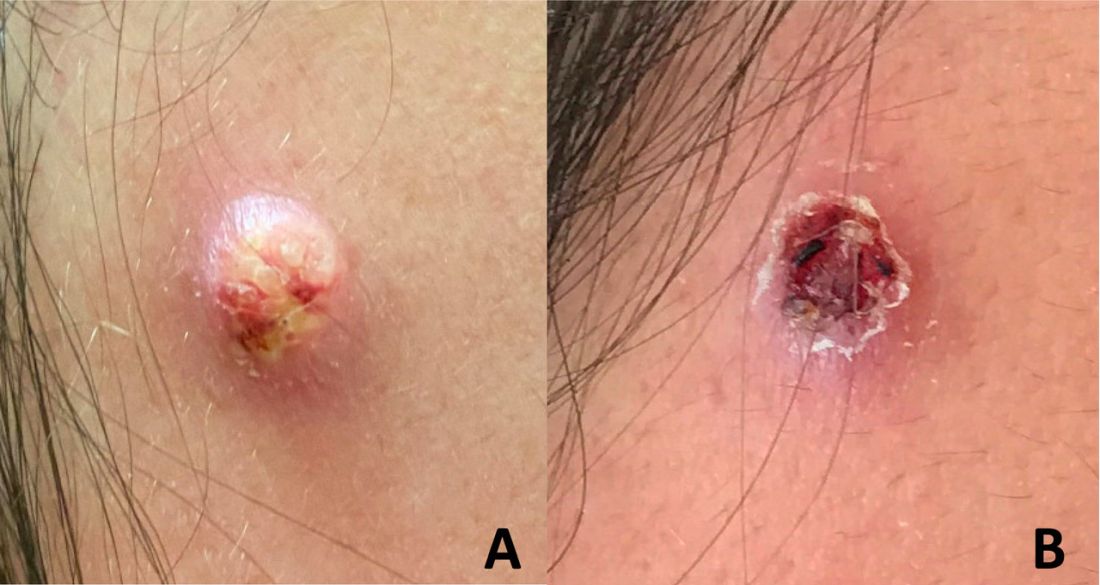

An adolescent male presents with an eroded bump on the temple

The correct answer is (D), molluscum contagiosum. Upon surgical excision, the pathology indicated the lesion was consistent with molluscum contagiosum.

Molluscum contagiosum is a benign skin disorder caused by a pox virus and is frequently seen in children. This disease is transmitted primarily through direct skin contact with an infected individual.1 Contaminated fomites have been suggested as another source of infection.2 The typical lesion appears dome-shaped, round, and pinkish-purple in color.1 The incubation period ranges from 2 weeks to 6 months and is typically self-limited in immunocompetent hosts; however, in immunocompromised persons, molluscum contagiosum lesions may present atypically such that they are larger in size and/or resemble malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma or keratoacanthoma (for single lesions), or other infectious diseases, such as cryptococcosis and histoplasmosis (for more numerous lesions).3,4 A giant atypical molluscum contagiosum is rarely seen in healthy individuals.

What’s on the differential?

The recent episode of bleeding raises concern for other neoplastic processes of the skin including squamous cell carcinoma or basal cell carcinoma as well as cutaneous metastatic rhabdoid tumor, given the patient’s history.

Eruptive keratoacanthomas are also reported in patients taking nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, which the patient has received for treatment of his recurrent metastatic rhabdoid tumor.5 More common entities such as a pyogenic granuloma or verruca are also included on the differential. The initial presentation of the lesion, however, is more consistent with the pearly umbilicated papules associated with molluscum contagiosum.

Comments from Dr. Eichenfield

This is a very hard diagnosis to make with the clinical findings and history.

Molluscum contagiosum infections are common, but with this patient’s medical history, biopsy and excision with pathologic examination was an appropriate approach to make a certain diagnosis.

Ms. Moyal is a research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego.

References

1. Brown J et al. Int J Dermatol. 2006 Feb;45(2):93-9.

2. Hanson D and Diven DG. Dermatol Online J. 2003 Mar;9(2).

3. Badri T and Gandhi GR. Molluscum contagiosum. 2022. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing.

4. Schwartz JJ and Myskowski PL. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992 Oct 1;27(4):583-8.

5. Antonov NK et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2019 Apr 5;5(4):342-5.

The correct answer is (D), molluscum contagiosum. Upon surgical excision, the pathology indicated the lesion was consistent with molluscum contagiosum.

Molluscum contagiosum is a benign skin disorder caused by a pox virus and is frequently seen in children. This disease is transmitted primarily through direct skin contact with an infected individual.1 Contaminated fomites have been suggested as another source of infection.2 The typical lesion appears dome-shaped, round, and pinkish-purple in color.1 The incubation period ranges from 2 weeks to 6 months and is typically self-limited in immunocompetent hosts; however, in immunocompromised persons, molluscum contagiosum lesions may present atypically such that they are larger in size and/or resemble malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma or keratoacanthoma (for single lesions), or other infectious diseases, such as cryptococcosis and histoplasmosis (for more numerous lesions).3,4 A giant atypical molluscum contagiosum is rarely seen in healthy individuals.

What’s on the differential?

The recent episode of bleeding raises concern for other neoplastic processes of the skin including squamous cell carcinoma or basal cell carcinoma as well as cutaneous metastatic rhabdoid tumor, given the patient’s history.

Eruptive keratoacanthomas are also reported in patients taking nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, which the patient has received for treatment of his recurrent metastatic rhabdoid tumor.5 More common entities such as a pyogenic granuloma or verruca are also included on the differential. The initial presentation of the lesion, however, is more consistent with the pearly umbilicated papules associated with molluscum contagiosum.

Comments from Dr. Eichenfield

This is a very hard diagnosis to make with the clinical findings and history.

Molluscum contagiosum infections are common, but with this patient’s medical history, biopsy and excision with pathologic examination was an appropriate approach to make a certain diagnosis.

Ms. Moyal is a research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego.

References

1. Brown J et al. Int J Dermatol. 2006 Feb;45(2):93-9.

2. Hanson D and Diven DG. Dermatol Online J. 2003 Mar;9(2).

3. Badri T and Gandhi GR. Molluscum contagiosum. 2022. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing.

4. Schwartz JJ and Myskowski PL. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992 Oct 1;27(4):583-8.

5. Antonov NK et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2019 Apr 5;5(4):342-5.

The correct answer is (D), molluscum contagiosum. Upon surgical excision, the pathology indicated the lesion was consistent with molluscum contagiosum.

Molluscum contagiosum is a benign skin disorder caused by a pox virus and is frequently seen in children. This disease is transmitted primarily through direct skin contact with an infected individual.1 Contaminated fomites have been suggested as another source of infection.2 The typical lesion appears dome-shaped, round, and pinkish-purple in color.1 The incubation period ranges from 2 weeks to 6 months and is typically self-limited in immunocompetent hosts; however, in immunocompromised persons, molluscum contagiosum lesions may present atypically such that they are larger in size and/or resemble malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma or keratoacanthoma (for single lesions), or other infectious diseases, such as cryptococcosis and histoplasmosis (for more numerous lesions).3,4 A giant atypical molluscum contagiosum is rarely seen in healthy individuals.

What’s on the differential?

The recent episode of bleeding raises concern for other neoplastic processes of the skin including squamous cell carcinoma or basal cell carcinoma as well as cutaneous metastatic rhabdoid tumor, given the patient’s history.

Eruptive keratoacanthomas are also reported in patients taking nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, which the patient has received for treatment of his recurrent metastatic rhabdoid tumor.5 More common entities such as a pyogenic granuloma or verruca are also included on the differential. The initial presentation of the lesion, however, is more consistent with the pearly umbilicated papules associated with molluscum contagiosum.

Comments from Dr. Eichenfield

This is a very hard diagnosis to make with the clinical findings and history.

Molluscum contagiosum infections are common, but with this patient’s medical history, biopsy and excision with pathologic examination was an appropriate approach to make a certain diagnosis.

Ms. Moyal is a research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego.

References