User login

Not COVID Toes: Pool Palms and Feet in Pediatric Patients

Practice Gap

Frictional, symmetric, asymptomatic, erythematous macules of the hands and feet can be mistaken for perniolike lesions associated with COVID-19, commonly known as COVID toes. However, in a low-risk setting without other associated symptoms or concerning findings on examination, consider and inquire about frequent use of a swimming pool. This activity can lead to localized pressure- and friction-induced erythema on palmar and plantar surfaces, called “pool palms and feet,” expanding on the already-named lesion “pool palms”—an entity that is distinct from COVID toes.

Technique for Diagnosis

We evaluated 4 patients in the outpatient setting who presented with localized, patterned, erythematous lesions of the hands or feet, or both, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The parents of our patients were concerned that the rash represented “COVID fingers and toes,” which are perniolike lesions seen in patients with suspected or confirmed current or prior COVID-19.1

Pernio, also known as chilblains, is a superficial inflammatory vascular response, usually in the setting of exposure to cold.2 This phenomenon usually appears as erythematous or violaceous macules and papules on acral skin, particularly on the dorsum and sides of the fingers and toes, with edema, vesiculation, and ulceration in more severe cases. Initially, it is pruritic and painful at times.

With COVID toes, there often is a delayed presentation of perniolike lesions after the onset of other COVID-19 symptoms, such as fever, cough, headache, and sore throat.2,3 It has been described more often in younger patients and those with milder disease. However, because our patients had no known exposure to SARS-CoV-2 or other associated symptoms, our suspicion was low.

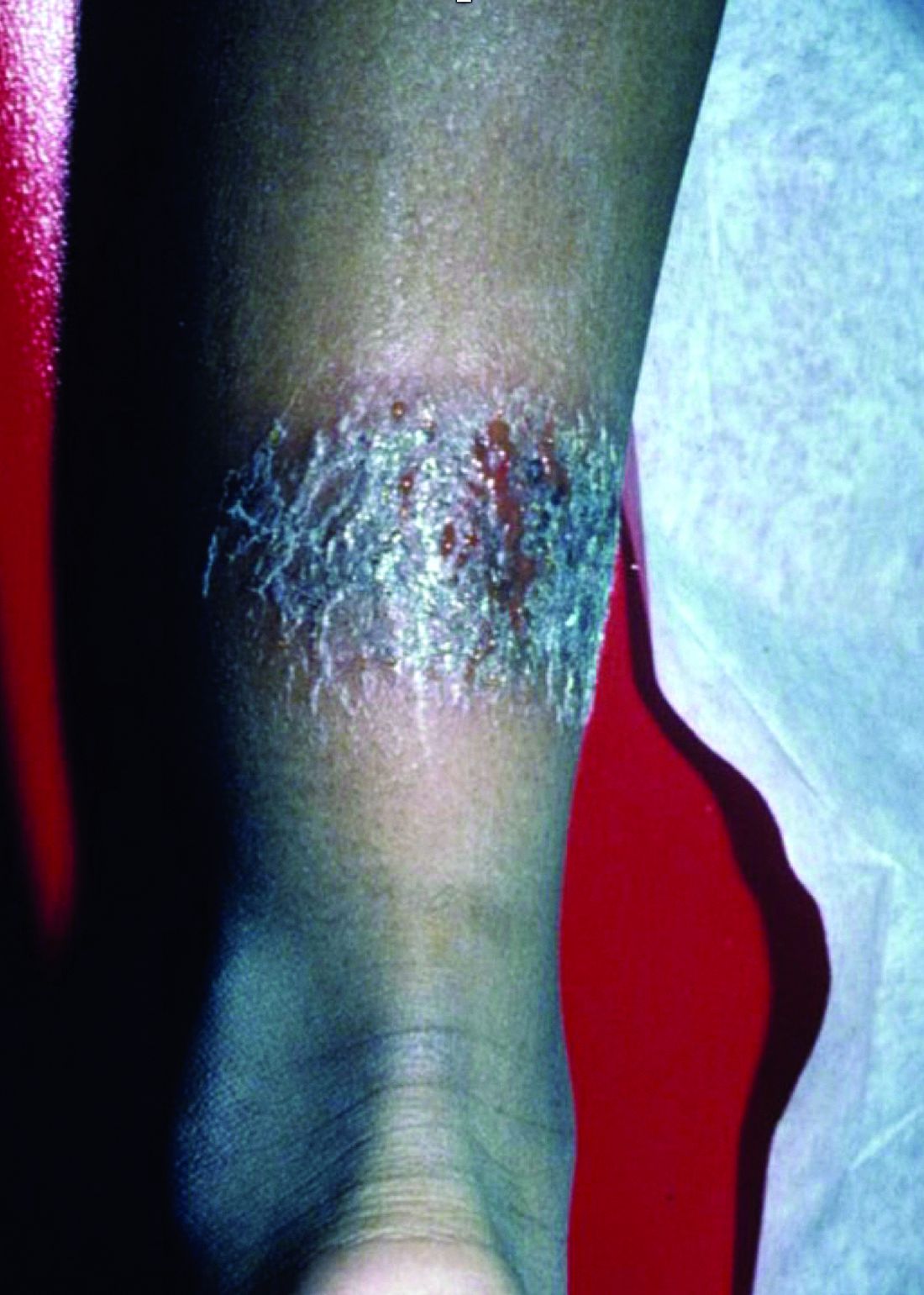

The 4 patients we evaluated—aged 4 to 12 years and in their usual good health—had blanchable erythema of the palmar fingers, palmar eminences of both hands, and plantar surfaces of both feet (Figure). There was no swelling or tenderness, and the lesions had no violaceous coloration, vesiculation, or ulceration. There was no associated pruritus or pain. One patient reported rough texture and mild peeling of the hands.

Upon further inquiry, the patients reported a history of extended time spent in home swimming pools, including holding on to the edge of the pool, due to limitation of activities because of COVID restrictions. One parent noted that the pool that caused the rash had a rough nonslip surface, whereas other pools that the children used, which had a smoother surface, caused no problems.

The morphology of symmetric blanching erythema in areas of pressure and friction, in the absence of a notable medical history, signs, or symptoms, was consistent with a diagnosis of pool palms, which has been described in the medical literature.4-9 Pool palms can affect the palms and soles, which are subject to substantial friction, especially when a person is getting in and out of the pool. There is a general consensus that pool palms is a frictional dermatitis affecting children because the greater fragility of their skin is exacerbated by immersion in water.4-9

Pool palms and feet is benign. Only supportive care, with cessation of swimming and application of emollients, is necessary.

Apart from COVID-19, other conditions to consider in a patient with erythematous lesions of the palms and soles include eczematous dermatitis; neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis; and, if lesions are vesicular, hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Juvenile plantar dermatosis, which is thought to be due to moisture with occlusion in shoes, also might be considered but is distinguished by more scales and fissures that can be painful.

Location of the lesions is a critical variable. The patients we evaluated had lesions primarily on palmar and plantar surfaces where contact with pool surfaces was greatest, such as at bony prominences, which supported a diagnosis of frictional dermatitis, such as pool palms and feet. A thorough history and physical examination are helpful in determining the diagnosis.

Practical Implications

It is important to consider and recognize this localized pressure phenomenon of pool palms and feet, thus obviating an unnecessary workup or therapeutic interventions. Specifically, a finding of erythematous asymptomatic macules, with or without scaling, on bony prominences of the palms and soles is more consistent with pool palms and feet.

Pernio and COVID toes both present as erythematous to violaceous papules and macules, with edema, vesiculation, and ulceration in severe cases, often on the dorsum and sides of fingers and toes; typically the conditions are pruritic and painful at times.

Explaining the diagnosis of pool palms and feet and sharing one’s experience with similar cases might help alleviate parental fear and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- de Masson A, Bouaziz J-D, Sulimovic L, et al; SNDV (French National Union of Dermatologists–Venereologists). Chilblains is a common cutaneous finding during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective nationwide study from France. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:667-670. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.161

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al; American Academy of Dermatology Ad Hoc Task Force on COVID-19. Pernio-like skin lesions associated with COVID-19: a case series of 318 patients from 8 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:486-492. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.109

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al. The spectrum of COVID-19-associated dermatologic manifestations: an international registry of 716 patients from 31 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1118-1129. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1016

- Blauvelt A, Duarte AM, Schachner LA. Pool palms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:111. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(08)80819-5

- Wong L-C, Rogers M. Pool palms. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:95. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00347.x

- Novoa A, Klear S. Pool palms. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:41. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2015-309633

- Morgado-Carasco D, Feola H, Vargas-Mora P. Pool palms. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2020;10:e2020009. doi:10.5826/dpc.1001a09

- Cutrone M, Valerio E, Grimalt R. Pool palms: a case report. Dermatol Case Rep. 2019;4:1000154.

- Martína JM, Ricart JM. Erythematous–violaceous lesions on the palms. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:507-508.

Practice Gap

Frictional, symmetric, asymptomatic, erythematous macules of the hands and feet can be mistaken for perniolike lesions associated with COVID-19, commonly known as COVID toes. However, in a low-risk setting without other associated symptoms or concerning findings on examination, consider and inquire about frequent use of a swimming pool. This activity can lead to localized pressure- and friction-induced erythema on palmar and plantar surfaces, called “pool palms and feet,” expanding on the already-named lesion “pool palms”—an entity that is distinct from COVID toes.

Technique for Diagnosis

We evaluated 4 patients in the outpatient setting who presented with localized, patterned, erythematous lesions of the hands or feet, or both, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The parents of our patients were concerned that the rash represented “COVID fingers and toes,” which are perniolike lesions seen in patients with suspected or confirmed current or prior COVID-19.1

Pernio, also known as chilblains, is a superficial inflammatory vascular response, usually in the setting of exposure to cold.2 This phenomenon usually appears as erythematous or violaceous macules and papules on acral skin, particularly on the dorsum and sides of the fingers and toes, with edema, vesiculation, and ulceration in more severe cases. Initially, it is pruritic and painful at times.

With COVID toes, there often is a delayed presentation of perniolike lesions after the onset of other COVID-19 symptoms, such as fever, cough, headache, and sore throat.2,3 It has been described more often in younger patients and those with milder disease. However, because our patients had no known exposure to SARS-CoV-2 or other associated symptoms, our suspicion was low.

The 4 patients we evaluated—aged 4 to 12 years and in their usual good health—had blanchable erythema of the palmar fingers, palmar eminences of both hands, and plantar surfaces of both feet (Figure). There was no swelling or tenderness, and the lesions had no violaceous coloration, vesiculation, or ulceration. There was no associated pruritus or pain. One patient reported rough texture and mild peeling of the hands.

Upon further inquiry, the patients reported a history of extended time spent in home swimming pools, including holding on to the edge of the pool, due to limitation of activities because of COVID restrictions. One parent noted that the pool that caused the rash had a rough nonslip surface, whereas other pools that the children used, which had a smoother surface, caused no problems.

The morphology of symmetric blanching erythema in areas of pressure and friction, in the absence of a notable medical history, signs, or symptoms, was consistent with a diagnosis of pool palms, which has been described in the medical literature.4-9 Pool palms can affect the palms and soles, which are subject to substantial friction, especially when a person is getting in and out of the pool. There is a general consensus that pool palms is a frictional dermatitis affecting children because the greater fragility of their skin is exacerbated by immersion in water.4-9

Pool palms and feet is benign. Only supportive care, with cessation of swimming and application of emollients, is necessary.

Apart from COVID-19, other conditions to consider in a patient with erythematous lesions of the palms and soles include eczematous dermatitis; neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis; and, if lesions are vesicular, hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Juvenile plantar dermatosis, which is thought to be due to moisture with occlusion in shoes, also might be considered but is distinguished by more scales and fissures that can be painful.

Location of the lesions is a critical variable. The patients we evaluated had lesions primarily on palmar and plantar surfaces where contact with pool surfaces was greatest, such as at bony prominences, which supported a diagnosis of frictional dermatitis, such as pool palms and feet. A thorough history and physical examination are helpful in determining the diagnosis.

Practical Implications

It is important to consider and recognize this localized pressure phenomenon of pool palms and feet, thus obviating an unnecessary workup or therapeutic interventions. Specifically, a finding of erythematous asymptomatic macules, with or without scaling, on bony prominences of the palms and soles is more consistent with pool palms and feet.

Pernio and COVID toes both present as erythematous to violaceous papules and macules, with edema, vesiculation, and ulceration in severe cases, often on the dorsum and sides of fingers and toes; typically the conditions are pruritic and painful at times.

Explaining the diagnosis of pool palms and feet and sharing one’s experience with similar cases might help alleviate parental fear and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Practice Gap

Frictional, symmetric, asymptomatic, erythematous macules of the hands and feet can be mistaken for perniolike lesions associated with COVID-19, commonly known as COVID toes. However, in a low-risk setting without other associated symptoms or concerning findings on examination, consider and inquire about frequent use of a swimming pool. This activity can lead to localized pressure- and friction-induced erythema on palmar and plantar surfaces, called “pool palms and feet,” expanding on the already-named lesion “pool palms”—an entity that is distinct from COVID toes.

Technique for Diagnosis

We evaluated 4 patients in the outpatient setting who presented with localized, patterned, erythematous lesions of the hands or feet, or both, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The parents of our patients were concerned that the rash represented “COVID fingers and toes,” which are perniolike lesions seen in patients with suspected or confirmed current or prior COVID-19.1

Pernio, also known as chilblains, is a superficial inflammatory vascular response, usually in the setting of exposure to cold.2 This phenomenon usually appears as erythematous or violaceous macules and papules on acral skin, particularly on the dorsum and sides of the fingers and toes, with edema, vesiculation, and ulceration in more severe cases. Initially, it is pruritic and painful at times.

With COVID toes, there often is a delayed presentation of perniolike lesions after the onset of other COVID-19 symptoms, such as fever, cough, headache, and sore throat.2,3 It has been described more often in younger patients and those with milder disease. However, because our patients had no known exposure to SARS-CoV-2 or other associated symptoms, our suspicion was low.

The 4 patients we evaluated—aged 4 to 12 years and in their usual good health—had blanchable erythema of the palmar fingers, palmar eminences of both hands, and plantar surfaces of both feet (Figure). There was no swelling or tenderness, and the lesions had no violaceous coloration, vesiculation, or ulceration. There was no associated pruritus or pain. One patient reported rough texture and mild peeling of the hands.

Upon further inquiry, the patients reported a history of extended time spent in home swimming pools, including holding on to the edge of the pool, due to limitation of activities because of COVID restrictions. One parent noted that the pool that caused the rash had a rough nonslip surface, whereas other pools that the children used, which had a smoother surface, caused no problems.

The morphology of symmetric blanching erythema in areas of pressure and friction, in the absence of a notable medical history, signs, or symptoms, was consistent with a diagnosis of pool palms, which has been described in the medical literature.4-9 Pool palms can affect the palms and soles, which are subject to substantial friction, especially when a person is getting in and out of the pool. There is a general consensus that pool palms is a frictional dermatitis affecting children because the greater fragility of their skin is exacerbated by immersion in water.4-9

Pool palms and feet is benign. Only supportive care, with cessation of swimming and application of emollients, is necessary.

Apart from COVID-19, other conditions to consider in a patient with erythematous lesions of the palms and soles include eczematous dermatitis; neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis; and, if lesions are vesicular, hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Juvenile plantar dermatosis, which is thought to be due to moisture with occlusion in shoes, also might be considered but is distinguished by more scales and fissures that can be painful.

Location of the lesions is a critical variable. The patients we evaluated had lesions primarily on palmar and plantar surfaces where contact with pool surfaces was greatest, such as at bony prominences, which supported a diagnosis of frictional dermatitis, such as pool palms and feet. A thorough history and physical examination are helpful in determining the diagnosis.

Practical Implications

It is important to consider and recognize this localized pressure phenomenon of pool palms and feet, thus obviating an unnecessary workup or therapeutic interventions. Specifically, a finding of erythematous asymptomatic macules, with or without scaling, on bony prominences of the palms and soles is more consistent with pool palms and feet.

Pernio and COVID toes both present as erythematous to violaceous papules and macules, with edema, vesiculation, and ulceration in severe cases, often on the dorsum and sides of fingers and toes; typically the conditions are pruritic and painful at times.

Explaining the diagnosis of pool palms and feet and sharing one’s experience with similar cases might help alleviate parental fear and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- de Masson A, Bouaziz J-D, Sulimovic L, et al; SNDV (French National Union of Dermatologists–Venereologists). Chilblains is a common cutaneous finding during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective nationwide study from France. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:667-670. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.161

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al; American Academy of Dermatology Ad Hoc Task Force on COVID-19. Pernio-like skin lesions associated with COVID-19: a case series of 318 patients from 8 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:486-492. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.109

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al. The spectrum of COVID-19-associated dermatologic manifestations: an international registry of 716 patients from 31 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1118-1129. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1016

- Blauvelt A, Duarte AM, Schachner LA. Pool palms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:111. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(08)80819-5

- Wong L-C, Rogers M. Pool palms. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:95. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00347.x

- Novoa A, Klear S. Pool palms. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:41. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2015-309633

- Morgado-Carasco D, Feola H, Vargas-Mora P. Pool palms. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2020;10:e2020009. doi:10.5826/dpc.1001a09

- Cutrone M, Valerio E, Grimalt R. Pool palms: a case report. Dermatol Case Rep. 2019;4:1000154.

- Martína JM, Ricart JM. Erythematous–violaceous lesions on the palms. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:507-508.

- de Masson A, Bouaziz J-D, Sulimovic L, et al; SNDV (French National Union of Dermatologists–Venereologists). Chilblains is a common cutaneous finding during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective nationwide study from France. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:667-670. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.161

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al; American Academy of Dermatology Ad Hoc Task Force on COVID-19. Pernio-like skin lesions associated with COVID-19: a case series of 318 patients from 8 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:486-492. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.109

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al. The spectrum of COVID-19-associated dermatologic manifestations: an international registry of 716 patients from 31 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1118-1129. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1016

- Blauvelt A, Duarte AM, Schachner LA. Pool palms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:111. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(08)80819-5

- Wong L-C, Rogers M. Pool palms. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:95. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00347.x

- Novoa A, Klear S. Pool palms. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:41. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2015-309633

- Morgado-Carasco D, Feola H, Vargas-Mora P. Pool palms. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2020;10:e2020009. doi:10.5826/dpc.1001a09

- Cutrone M, Valerio E, Grimalt R. Pool palms: a case report. Dermatol Case Rep. 2019;4:1000154.

- Martína JM, Ricart JM. Erythematous–violaceous lesions on the palms. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:507-508.

Update on Pediatric Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, pruritic, inflammatory skin disease that occurs most frequently in children but also affects many adolescents and adults. There has been a tremendous evolution of knowledge in AD, with insights into pathogenesis, epidemiology, impact of disease, and new therapies. A variety of studies examine the epidemiology of AD and associated comorbidities. The broad developments in disease state research are reflected in new publication numbers of AD citations on PubMed. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE at the end of 2010 using the term atopic dermatitis would have shown 965 citations during the preceding 1-year period. In the 1-year period of June 2019 to June 2020, there were more than 2000 articles. The large body of research includes work of great significance in pediatric AD, and in this article we review recent findings that are important in understanding the progress being made in the field.

Epidemiology and Comorbidities

The epidemiology of AD has evolved over the last few decades, with emerging trends and novel insights into the burden of disease.1 In a recent cross-sectional study on the epidemiology of AD in children aged 6 to 11 years, the 1-year diagnosed AD prevalence estimates worldwide included the following: United States, 10.0%; Canada, 13.3%; the EU5 Countries, 15.5%; Japan, 10.3%; and all countries studied, 12.2%.2 Another recent paper that analyzed data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study showed that the prevalence and persistence of AD in urban US children was 15.0%.3Although pediatric AD may spontaneously remit over time, disease continuing into adolescence and adulthood is common. Paternoster et al4 studied the longitudinal course of AD in children from 2 birth cohort prospective studies, showing distinct AD phenotypes having differing course trajectories over time. Disease subsets included patients with early-onset-persistent and early-onset-late-resolving disease.4 Whether phenotyping or subgroup analysis can be used to predict disease course or risk for development of comorbidities is unknown, but it is interesting to consider how such work could influence tailoring of specific therapies to early disease presentation.

Atopic dermatitis poses a serious public health burden owing to its high prevalence, considerable morbidity and disability, increased health care utilization, and cost of care.1 Recent studies have found notably higher rates of multiple medical and mental health comorbidities in both children and adults with AD, including infections, atopic comorbidities (eg, allergic rhinitis, asthma, food allergies), eye diseases (eg, keratitis, conjunctivitis, keratoconus), and possible cardiovascular diseases and autoimmune disorders.1,5-9 Allergic comorbidities are quite common in pediatric AD patients.10 In a recent study examining the efficacy and safety of dupilumab monotherapy in 251 adolescents with moderate to severe inadequately controlled AD, most had comorbid type 2 diseases including asthma (53.6%), food allergies (60.8%), and allergic rhinitis (65.6%).11

Quality of Life/Life Impact of AD

Pediatric AD has a major impact on the quality of life of patients and their families.12 The well-being and development of children are strongly influenced by the physical and psychosocial health of parents/guardians. Two studies by Ramirez and colleagues13,14 published in 2019 examined sleep disturbances and exhaustion in mothers of children with AD. Data for the studies came from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Children with active AD reported worse sleep quality than those without AD, with nearly 50% higher odds of sleep-quality disturbances. Analysis of the cohort data from 11,649 mother-child pairs who were followed up with a time-varying measure of child AD activity and severity as well as self-reported maternal sleep measures repeated at multiple time points for children aged 6 months to 11 years showed that mothers of children with AD reported difficulty falling asleep, subjectively insufficient sleep, and daytime exhaustion throughout the first 11 years of childhood.13,14 These data suggest that sleep disturbance may be a family affair.

A cross-sectional, real-world study on the burden of AD in children aged 6 to 11 years assessed by self-report demonstrated a substantial and multidimensional impact of AD, including itch, sleep disturbance, skin pain, and health-related quality-of-life impact, as well as comorbidities and school productivity losses. The burden associated with AD was remarkable and increased with disease severity.15

Drucker et al16 completed a comprehensive literature review on the burden of AD, summarized as a report for the National Eczema Association. Quality-of-life impact on pediatric patients included high rates of emotional distress; social isolation; depression; limitations in activities due to lesions with fear of triggers; and behavioral problems such as irritability, crying, and sleep disturbance resulting in difficulty performing at school.16 The psychological impact on children as well as emotional and behavioral difficulties may impact the ability for parents/guardians to implement treatment plans.17

There is a striking association between mental health disorders and AD in the US pediatric population, with a clear dose-dependent relationship that has been observed between the prevalence of a mental health disorder and the reported severity of the skin disease. Data suggest children with AD may be at increased risk for developing mental health disorders. The National Survey of Children’s Health found statistically significant increases in the likelihood of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (odds ratio [OR], 1.87), depression (OR, 1.81), anxiety (OR, 1.77), conduct disorder (OR, 1.87), and autism (OR, 3.04).6

Evolving Practices and Therapies

Bathing Practices

There has long been much controversy regarding best bathing habits for patients with AD. In a 2009 study, cutaneous hydration was quantified after various bathing and moisturizing regimens.18 The study showed clear benefits of emollient application on skin hydration, either after bathing or without bathing. Bathing followed by emollient applications did not decrease skin hydration in contrast to bathing without emollient application.18

There are limited studies evaluating bathing frequency in pediatric patients, and many families receive conflicting information regarding best practice. In one study that surveyed 354 parents, more than 75% of parents/guardians who had seen multiple providers for their child’s AD reported a substantial amount of confusion and frustration from conflicting advice on bathing frequency.19 Cardona et al20 undertook a randomized clinical trial of frequent bathing and moisturizing vs less-frequent bathing and moisturizing in pediatric patients with AD aged 6 months to 11 years. Patients were divided into 2 groups: 1 being bathed twice daily with immediate moisturizer application and the other being bathed twice weekly followed by moisturization, then a switch to the other method. Patients used standardized topical corticosteroids (TCSs) in both groups. There were significant improvements in scoring AD and other objective measures during the frequent bathing time period vs infrequent bathing; in the group that bathed more frequently, SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis) decreased by 21.2 compared with the group that bathed less frequently (95% confidence interval, 14.9-27.6; P<.0001). These findings suggest that more-frequent bathing with immediate moisturization is superior as an acute treatment intervention for improving AD disease severity in comparison to less-frequent bathing with immediate moisturization.20

Expanding Treatment Options

Topical Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors

There are several new and evolving topical therapies in AD. Crisaborole ointment 2% is a steroid-free phosphodiesterase inhibitor approved in 2016 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for mild to moderate AD in patients aged 2 years and older. A recent multicenter, open-label, single-arm study in 137 infants (CrisADe CARE 1) evaluated the pharmacokinetics and efficacy of crisaborole ointment 2% applied twice daily for 4 weeks in pediatric patients aged 3 months to less than 24 months of age with mild to moderate AD.21 The study had 2 cohorts: one with a minimum of 5% body surface area involvement and another (the pharmacokinetic cohort) with a minimum of 35% body surface area involvement. Both cohorts demonstrated similar efficacy data. From baseline to day 29, the mean percentage change in eczema area and severity index (EASI) score was −57.5%, and an investigator global assessment (IGA) score of clear or almost clear with at least a 2-grade improvement was achieved in 30.2% of patients. Crisaborole systemic exposures in infants were comparable with those in patients aged 2 years or older. Patients tolerated crisaborole well, with a 4% rate of burning, which was similar to other studies in children and adults but perhaps lower than seen in clinical practice. Pharmacokinetic studies did not show any remarkable noticeable concern with accumulation of propylene glycol absorption.21

Based on the CrisADe CARE 1 study data, in March 2020 the FDA extended the indication of crisaborole ointment 2% from a prior lower age limit of 24 months to approval for use in treating mild to moderate AD in children as young as 3 months, making it the first nonsteroidal topical anti-inflammatory medication to be approved in children younger than 2 years in the United States.

Evolving Topical Therapies

Topical Janus Kinase Inhibitors

Ruxolitinib is a potent inhibitor of Janus kinase 1 (JAK-1) and Janus kinase 2 (JAK-2) and has been developed in topical formulations. In recent phase 3 clinical trials of patients with AD aged 12 years and older with mild to moderate disease (TRuE-AD1 and TRuE-AD2), more than half of the patients treated with either ruxolitinib cream in a 0.75% or 1.5% concentration reached EASI-75 after 8 weeks of treatment.22 Additionally, more patients treated with topical ruxolitinib reached an IGA score of clear to almost clear than patients treated with vehicle at the end of treatment. Thus far, it appears to be very well tolerated, significantly decreases EASI score (P<.0001), and improves overall pruritus.22

Delgocitinib is a topical pan-JAK inhibitor that blocks several cytokine-signaling cascade pathways. It was first developed and approved in Japan in an ointment formulation for use in patients with AD aged 16 years and older.23 The efficacy and safety profile of delgocitinib is currently being evaluated in pediatric patients with AD in Japan. In a recent phase 2 clinical study of 103 Japanese patients aged 2 to 15 years with moderate to severe AD, patients were randomized to receive either delgocitinib ointment in 0.25% or 0.5% concentrations or vehicle ointment twice daily for 4 weeks. The proportion of patients with a modified EASI-75 score was 38.2% (13/34) in the 0.25% group and 50.0% (17/34) in the 0.5% group vs 8.6% (3/35) in the placebo group. More patients treated with delgocitinib ointment received an IGA score of clear or almost clear than patients treated with vehicle at the end of treatment. Overall, both delgocitinib groups demonstrated superior improvement in clinical symptoms and signs without notable side effects.24

Tapinarof

Tapinarof is a topical therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist. In a recent phase 2 randomized study of 2 concentrations and 2 frequencies of tapinarof cream vs vehicle in 247 randomized patients aged 12 to 65 years with moderate to severe disease, tapinarof demonstrated greater success with both concentrations than vehicle at all visits beyond week 2.25 Additionally, in patients treated with tapinarof cream 1%, nearly 50% reached an IGA score of clear to almost clear with at least a 2-grade improvement. More than 50% of patients achieved EASI-75 improvement at 12 weeks of treatment with tapinarof cream 1% used daily. These findings suggest that tapinarof may be an efficacious and well-tolerated treatment for both adolescents and adults with AD; however, large confirmation trials are needed to further investigate.25

Systemic Treatments

Oral JAK Inhibitors

Some of the most exciting novel therapies include several oral JAK inhibitors that target different combinations of kinases and have been shown to decrease AD severity and symptoms. Some of these agents have indications in other disease states, such as baricitinib and upadacitinib, which are both FDA approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, whereas others, such as abrocitinib, have been studied specifically for AD.

Although some agents have only been studied in adults to date, others have included adolescents in their core studies, such as abrocitinib, which received Breakthrough Therapy designation from the FDA for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe AD in February 2018. In recent phase 3 trials of patients aged 12 years and older with moderate to severe AD (JADE MONO-1 and JADE MONO-2), both doses of abrocitinib improved the IGA and EASI-75 outcomes compared with placebo.26 Additional studies will be conducted to further investigate the relative efficacy and safety in patients younger than 18 years.

Biologics

Dupilumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody that inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 signaling without suppressing the immune system. It is approved for use in patients aged 12 years and older with moderate to severe asthma and in adults with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. It is the first biologic to show positive results in the moderate to severe pediatric AD population. There are now extended data available exhibiting sustained benefit in adolescent patients who were continued on dupilumab therapy, evidenced by further improvement in EASI scores at the 1-year mark.27

Recently, dupilumab received approval for use in patients aged 6 to 11 years, making it the first biologic for AD to be approved for use in patients younger than 12 years. The expedited FDA approval was based on the phase 3 results in which the efficacy and safety of dupilumab combined with TCSs were compared to TCSs alone (N=367).28 In this trial, more than twice as many children achieved clear or almost clear skin and more than 4 times as many achieved itch reduction with dupilumab plus TCSs than with TCSs alone. Three-quarters of patients receiving dupilumab at the subsequently approved dosing achieved at least a 75% improvement in overall disease.28 An additional study is being conducted that includes pediatric patients aged 6 months to younger than 6 years (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03346434).

Future Directions in Pediatric AD

Our review summarizes only some of the agents under clinical investigation for use in pediatric AD. Early treatment to establish excellent long-term disease control with aggressive topical regimens or with systemic agents may alter the course of AD and influence the development of comorbidities, though this has not yet been shown in clinical studies. The long-term impact of early treatment, along with many other intriguing issues, will be studied more in the near future.

- Silverberg JI. Public health burden and epidemiology of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:283-289.

- Silverberg JI, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, et al. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in children aged 6–11 years: a cross-sectional study in the United States (US), Canada, Europe, and Japan. Paper presented at: American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting; March 20-24, 2020; Denver, CO.

- McKenzie C, Silverberg JI. The prevalence and persistence of atopic dermatitis in urban United States children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123:173-178.e1.

- Paternoster L, Savenije OEM, Heron J, et al. IJ Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:964-971.

- Silverberg JI, Simpson EL. Association between severe eczema in children and multiple comorbid conditions and increased healthcare utilization. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2013;24:476-486.

- Yaghmaie P, Koudelka CW, Simpson Mental health comorbidity in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:428-433.

- Narla S, Silverberg JI. Association between childhood atopic dermatitis and cutaneous, extracutaneous and systemic infections. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:1467-1468.

- al. Incidence, prevalence, and risk of selected ocular disease in adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:280-286.

- Association of atopic dermatitis with cardiovascular risk factors and diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:1074-1081.

- Major comorbidities of atopic dermatitis: beyond allergic disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:821-838.

- Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.

- Quality of life in families with children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:28-32.

- Assessment of sleep disturbances and exhaustion in mothers of children with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:556-563.

- Association of atopic dermatitis with sleep quality in children.

- Weidinger S, Simpson EL, Eckert L, et al. The patient-reported disease burden in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis: a cross-sectional study in the United States (US), Canada, Europe, and Japan. Paperpresented at: American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting; March 20-24, 2020; Denver, CO.

- The burden of atopic dermatitis: summary of a report for the National Eczema Association. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:26-30.

- Mitchell AE. Bidirectional relationships between psychological health and dermatological conditions in children. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2018;11:289-298.

- Chiang C, Eichenfield LF. Quantitative assessment of combination bathing and moisturizing regimens on skin hydration in atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:273-278.

- Kempe E, Jain N, Cardona I. Bathing frequency recommendations for pediatric atopic dermatitis: are we adding to parental frustration? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;111:298‐299.

- Cardona ID, Kempe EE, Lary C, et al. Frequent versus infrequent bathing in pediatric atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:1014‐1021.

- Gower , Safety, effectiveness, and pharmacokinetics of crisaborole in infants aged 3 to <24 months with mild‐to‐moderate atopic dermatitis: a phase IV open‐label study (CrisADe CARE 1). Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:275-284.

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment atopic dermatitis: results from two phase 3, randomized, double-blind studies. Presented at: 2nd Annual Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis Conference; April 5, 2020; Chicago, IL.

- Dhillon S. Delgocitinib: first approval. Drugs. 2020;80:609‐615.

- Nakagawa H, Nemoto O, Igarashi A, et al. Phase 2 clinical study of delgocitinib ointment in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144:1575‐1583.

- Peppers J, Paller AS, Maeda-Chubachi T, et al. A phase 2, randomized dose-finding study of tapinarof (GSK2894512 cream) for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:89‐98.e3.

- Simpson EL, Sinclair R, Forman S, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (JADE MONO-1): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396:255-266.

- Cork MJ, Thaçi D, Eichenfield LF, et al. Dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from a phase IIa open-label trial and subsequent phase III open-label extension. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:85‐96.

- Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Thaçi D, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial [published online June 20, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.054.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, pruritic, inflammatory skin disease that occurs most frequently in children but also affects many adolescents and adults. There has been a tremendous evolution of knowledge in AD, with insights into pathogenesis, epidemiology, impact of disease, and new therapies. A variety of studies examine the epidemiology of AD and associated comorbidities. The broad developments in disease state research are reflected in new publication numbers of AD citations on PubMed. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE at the end of 2010 using the term atopic dermatitis would have shown 965 citations during the preceding 1-year period. In the 1-year period of June 2019 to June 2020, there were more than 2000 articles. The large body of research includes work of great significance in pediatric AD, and in this article we review recent findings that are important in understanding the progress being made in the field.

Epidemiology and Comorbidities

The epidemiology of AD has evolved over the last few decades, with emerging trends and novel insights into the burden of disease.1 In a recent cross-sectional study on the epidemiology of AD in children aged 6 to 11 years, the 1-year diagnosed AD prevalence estimates worldwide included the following: United States, 10.0%; Canada, 13.3%; the EU5 Countries, 15.5%; Japan, 10.3%; and all countries studied, 12.2%.2 Another recent paper that analyzed data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study showed that the prevalence and persistence of AD in urban US children was 15.0%.3Although pediatric AD may spontaneously remit over time, disease continuing into adolescence and adulthood is common. Paternoster et al4 studied the longitudinal course of AD in children from 2 birth cohort prospective studies, showing distinct AD phenotypes having differing course trajectories over time. Disease subsets included patients with early-onset-persistent and early-onset-late-resolving disease.4 Whether phenotyping or subgroup analysis can be used to predict disease course or risk for development of comorbidities is unknown, but it is interesting to consider how such work could influence tailoring of specific therapies to early disease presentation.

Atopic dermatitis poses a serious public health burden owing to its high prevalence, considerable morbidity and disability, increased health care utilization, and cost of care.1 Recent studies have found notably higher rates of multiple medical and mental health comorbidities in both children and adults with AD, including infections, atopic comorbidities (eg, allergic rhinitis, asthma, food allergies), eye diseases (eg, keratitis, conjunctivitis, keratoconus), and possible cardiovascular diseases and autoimmune disorders.1,5-9 Allergic comorbidities are quite common in pediatric AD patients.10 In a recent study examining the efficacy and safety of dupilumab monotherapy in 251 adolescents with moderate to severe inadequately controlled AD, most had comorbid type 2 diseases including asthma (53.6%), food allergies (60.8%), and allergic rhinitis (65.6%).11

Quality of Life/Life Impact of AD

Pediatric AD has a major impact on the quality of life of patients and their families.12 The well-being and development of children are strongly influenced by the physical and psychosocial health of parents/guardians. Two studies by Ramirez and colleagues13,14 published in 2019 examined sleep disturbances and exhaustion in mothers of children with AD. Data for the studies came from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Children with active AD reported worse sleep quality than those without AD, with nearly 50% higher odds of sleep-quality disturbances. Analysis of the cohort data from 11,649 mother-child pairs who were followed up with a time-varying measure of child AD activity and severity as well as self-reported maternal sleep measures repeated at multiple time points for children aged 6 months to 11 years showed that mothers of children with AD reported difficulty falling asleep, subjectively insufficient sleep, and daytime exhaustion throughout the first 11 years of childhood.13,14 These data suggest that sleep disturbance may be a family affair.

A cross-sectional, real-world study on the burden of AD in children aged 6 to 11 years assessed by self-report demonstrated a substantial and multidimensional impact of AD, including itch, sleep disturbance, skin pain, and health-related quality-of-life impact, as well as comorbidities and school productivity losses. The burden associated with AD was remarkable and increased with disease severity.15

Drucker et al16 completed a comprehensive literature review on the burden of AD, summarized as a report for the National Eczema Association. Quality-of-life impact on pediatric patients included high rates of emotional distress; social isolation; depression; limitations in activities due to lesions with fear of triggers; and behavioral problems such as irritability, crying, and sleep disturbance resulting in difficulty performing at school.16 The psychological impact on children as well as emotional and behavioral difficulties may impact the ability for parents/guardians to implement treatment plans.17

There is a striking association between mental health disorders and AD in the US pediatric population, with a clear dose-dependent relationship that has been observed between the prevalence of a mental health disorder and the reported severity of the skin disease. Data suggest children with AD may be at increased risk for developing mental health disorders. The National Survey of Children’s Health found statistically significant increases in the likelihood of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (odds ratio [OR], 1.87), depression (OR, 1.81), anxiety (OR, 1.77), conduct disorder (OR, 1.87), and autism (OR, 3.04).6

Evolving Practices and Therapies

Bathing Practices

There has long been much controversy regarding best bathing habits for patients with AD. In a 2009 study, cutaneous hydration was quantified after various bathing and moisturizing regimens.18 The study showed clear benefits of emollient application on skin hydration, either after bathing or without bathing. Bathing followed by emollient applications did not decrease skin hydration in contrast to bathing without emollient application.18

There are limited studies evaluating bathing frequency in pediatric patients, and many families receive conflicting information regarding best practice. In one study that surveyed 354 parents, more than 75% of parents/guardians who had seen multiple providers for their child’s AD reported a substantial amount of confusion and frustration from conflicting advice on bathing frequency.19 Cardona et al20 undertook a randomized clinical trial of frequent bathing and moisturizing vs less-frequent bathing and moisturizing in pediatric patients with AD aged 6 months to 11 years. Patients were divided into 2 groups: 1 being bathed twice daily with immediate moisturizer application and the other being bathed twice weekly followed by moisturization, then a switch to the other method. Patients used standardized topical corticosteroids (TCSs) in both groups. There were significant improvements in scoring AD and other objective measures during the frequent bathing time period vs infrequent bathing; in the group that bathed more frequently, SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis) decreased by 21.2 compared with the group that bathed less frequently (95% confidence interval, 14.9-27.6; P<.0001). These findings suggest that more-frequent bathing with immediate moisturization is superior as an acute treatment intervention for improving AD disease severity in comparison to less-frequent bathing with immediate moisturization.20

Expanding Treatment Options

Topical Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors

There are several new and evolving topical therapies in AD. Crisaborole ointment 2% is a steroid-free phosphodiesterase inhibitor approved in 2016 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for mild to moderate AD in patients aged 2 years and older. A recent multicenter, open-label, single-arm study in 137 infants (CrisADe CARE 1) evaluated the pharmacokinetics and efficacy of crisaborole ointment 2% applied twice daily for 4 weeks in pediatric patients aged 3 months to less than 24 months of age with mild to moderate AD.21 The study had 2 cohorts: one with a minimum of 5% body surface area involvement and another (the pharmacokinetic cohort) with a minimum of 35% body surface area involvement. Both cohorts demonstrated similar efficacy data. From baseline to day 29, the mean percentage change in eczema area and severity index (EASI) score was −57.5%, and an investigator global assessment (IGA) score of clear or almost clear with at least a 2-grade improvement was achieved in 30.2% of patients. Crisaborole systemic exposures in infants were comparable with those in patients aged 2 years or older. Patients tolerated crisaborole well, with a 4% rate of burning, which was similar to other studies in children and adults but perhaps lower than seen in clinical practice. Pharmacokinetic studies did not show any remarkable noticeable concern with accumulation of propylene glycol absorption.21

Based on the CrisADe CARE 1 study data, in March 2020 the FDA extended the indication of crisaborole ointment 2% from a prior lower age limit of 24 months to approval for use in treating mild to moderate AD in children as young as 3 months, making it the first nonsteroidal topical anti-inflammatory medication to be approved in children younger than 2 years in the United States.

Evolving Topical Therapies

Topical Janus Kinase Inhibitors

Ruxolitinib is a potent inhibitor of Janus kinase 1 (JAK-1) and Janus kinase 2 (JAK-2) and has been developed in topical formulations. In recent phase 3 clinical trials of patients with AD aged 12 years and older with mild to moderate disease (TRuE-AD1 and TRuE-AD2), more than half of the patients treated with either ruxolitinib cream in a 0.75% or 1.5% concentration reached EASI-75 after 8 weeks of treatment.22 Additionally, more patients treated with topical ruxolitinib reached an IGA score of clear to almost clear than patients treated with vehicle at the end of treatment. Thus far, it appears to be very well tolerated, significantly decreases EASI score (P<.0001), and improves overall pruritus.22

Delgocitinib is a topical pan-JAK inhibitor that blocks several cytokine-signaling cascade pathways. It was first developed and approved in Japan in an ointment formulation for use in patients with AD aged 16 years and older.23 The efficacy and safety profile of delgocitinib is currently being evaluated in pediatric patients with AD in Japan. In a recent phase 2 clinical study of 103 Japanese patients aged 2 to 15 years with moderate to severe AD, patients were randomized to receive either delgocitinib ointment in 0.25% or 0.5% concentrations or vehicle ointment twice daily for 4 weeks. The proportion of patients with a modified EASI-75 score was 38.2% (13/34) in the 0.25% group and 50.0% (17/34) in the 0.5% group vs 8.6% (3/35) in the placebo group. More patients treated with delgocitinib ointment received an IGA score of clear or almost clear than patients treated with vehicle at the end of treatment. Overall, both delgocitinib groups demonstrated superior improvement in clinical symptoms and signs without notable side effects.24

Tapinarof

Tapinarof is a topical therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist. In a recent phase 2 randomized study of 2 concentrations and 2 frequencies of tapinarof cream vs vehicle in 247 randomized patients aged 12 to 65 years with moderate to severe disease, tapinarof demonstrated greater success with both concentrations than vehicle at all visits beyond week 2.25 Additionally, in patients treated with tapinarof cream 1%, nearly 50% reached an IGA score of clear to almost clear with at least a 2-grade improvement. More than 50% of patients achieved EASI-75 improvement at 12 weeks of treatment with tapinarof cream 1% used daily. These findings suggest that tapinarof may be an efficacious and well-tolerated treatment for both adolescents and adults with AD; however, large confirmation trials are needed to further investigate.25

Systemic Treatments

Oral JAK Inhibitors

Some of the most exciting novel therapies include several oral JAK inhibitors that target different combinations of kinases and have been shown to decrease AD severity and symptoms. Some of these agents have indications in other disease states, such as baricitinib and upadacitinib, which are both FDA approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, whereas others, such as abrocitinib, have been studied specifically for AD.

Although some agents have only been studied in adults to date, others have included adolescents in their core studies, such as abrocitinib, which received Breakthrough Therapy designation from the FDA for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe AD in February 2018. In recent phase 3 trials of patients aged 12 years and older with moderate to severe AD (JADE MONO-1 and JADE MONO-2), both doses of abrocitinib improved the IGA and EASI-75 outcomes compared with placebo.26 Additional studies will be conducted to further investigate the relative efficacy and safety in patients younger than 18 years.

Biologics

Dupilumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody that inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 signaling without suppressing the immune system. It is approved for use in patients aged 12 years and older with moderate to severe asthma and in adults with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. It is the first biologic to show positive results in the moderate to severe pediatric AD population. There are now extended data available exhibiting sustained benefit in adolescent patients who were continued on dupilumab therapy, evidenced by further improvement in EASI scores at the 1-year mark.27

Recently, dupilumab received approval for use in patients aged 6 to 11 years, making it the first biologic for AD to be approved for use in patients younger than 12 years. The expedited FDA approval was based on the phase 3 results in which the efficacy and safety of dupilumab combined with TCSs were compared to TCSs alone (N=367).28 In this trial, more than twice as many children achieved clear or almost clear skin and more than 4 times as many achieved itch reduction with dupilumab plus TCSs than with TCSs alone. Three-quarters of patients receiving dupilumab at the subsequently approved dosing achieved at least a 75% improvement in overall disease.28 An additional study is being conducted that includes pediatric patients aged 6 months to younger than 6 years (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03346434).

Future Directions in Pediatric AD

Our review summarizes only some of the agents under clinical investigation for use in pediatric AD. Early treatment to establish excellent long-term disease control with aggressive topical regimens or with systemic agents may alter the course of AD and influence the development of comorbidities, though this has not yet been shown in clinical studies. The long-term impact of early treatment, along with many other intriguing issues, will be studied more in the near future.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, pruritic, inflammatory skin disease that occurs most frequently in children but also affects many adolescents and adults. There has been a tremendous evolution of knowledge in AD, with insights into pathogenesis, epidemiology, impact of disease, and new therapies. A variety of studies examine the epidemiology of AD and associated comorbidities. The broad developments in disease state research are reflected in new publication numbers of AD citations on PubMed. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE at the end of 2010 using the term atopic dermatitis would have shown 965 citations during the preceding 1-year period. In the 1-year period of June 2019 to June 2020, there were more than 2000 articles. The large body of research includes work of great significance in pediatric AD, and in this article we review recent findings that are important in understanding the progress being made in the field.

Epidemiology and Comorbidities

The epidemiology of AD has evolved over the last few decades, with emerging trends and novel insights into the burden of disease.1 In a recent cross-sectional study on the epidemiology of AD in children aged 6 to 11 years, the 1-year diagnosed AD prevalence estimates worldwide included the following: United States, 10.0%; Canada, 13.3%; the EU5 Countries, 15.5%; Japan, 10.3%; and all countries studied, 12.2%.2 Another recent paper that analyzed data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study showed that the prevalence and persistence of AD in urban US children was 15.0%.3Although pediatric AD may spontaneously remit over time, disease continuing into adolescence and adulthood is common. Paternoster et al4 studied the longitudinal course of AD in children from 2 birth cohort prospective studies, showing distinct AD phenotypes having differing course trajectories over time. Disease subsets included patients with early-onset-persistent and early-onset-late-resolving disease.4 Whether phenotyping or subgroup analysis can be used to predict disease course or risk for development of comorbidities is unknown, but it is interesting to consider how such work could influence tailoring of specific therapies to early disease presentation.

Atopic dermatitis poses a serious public health burden owing to its high prevalence, considerable morbidity and disability, increased health care utilization, and cost of care.1 Recent studies have found notably higher rates of multiple medical and mental health comorbidities in both children and adults with AD, including infections, atopic comorbidities (eg, allergic rhinitis, asthma, food allergies), eye diseases (eg, keratitis, conjunctivitis, keratoconus), and possible cardiovascular diseases and autoimmune disorders.1,5-9 Allergic comorbidities are quite common in pediatric AD patients.10 In a recent study examining the efficacy and safety of dupilumab monotherapy in 251 adolescents with moderate to severe inadequately controlled AD, most had comorbid type 2 diseases including asthma (53.6%), food allergies (60.8%), and allergic rhinitis (65.6%).11

Quality of Life/Life Impact of AD

Pediatric AD has a major impact on the quality of life of patients and their families.12 The well-being and development of children are strongly influenced by the physical and psychosocial health of parents/guardians. Two studies by Ramirez and colleagues13,14 published in 2019 examined sleep disturbances and exhaustion in mothers of children with AD. Data for the studies came from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Children with active AD reported worse sleep quality than those without AD, with nearly 50% higher odds of sleep-quality disturbances. Analysis of the cohort data from 11,649 mother-child pairs who were followed up with a time-varying measure of child AD activity and severity as well as self-reported maternal sleep measures repeated at multiple time points for children aged 6 months to 11 years showed that mothers of children with AD reported difficulty falling asleep, subjectively insufficient sleep, and daytime exhaustion throughout the first 11 years of childhood.13,14 These data suggest that sleep disturbance may be a family affair.

A cross-sectional, real-world study on the burden of AD in children aged 6 to 11 years assessed by self-report demonstrated a substantial and multidimensional impact of AD, including itch, sleep disturbance, skin pain, and health-related quality-of-life impact, as well as comorbidities and school productivity losses. The burden associated with AD was remarkable and increased with disease severity.15

Drucker et al16 completed a comprehensive literature review on the burden of AD, summarized as a report for the National Eczema Association. Quality-of-life impact on pediatric patients included high rates of emotional distress; social isolation; depression; limitations in activities due to lesions with fear of triggers; and behavioral problems such as irritability, crying, and sleep disturbance resulting in difficulty performing at school.16 The psychological impact on children as well as emotional and behavioral difficulties may impact the ability for parents/guardians to implement treatment plans.17

There is a striking association between mental health disorders and AD in the US pediatric population, with a clear dose-dependent relationship that has been observed between the prevalence of a mental health disorder and the reported severity of the skin disease. Data suggest children with AD may be at increased risk for developing mental health disorders. The National Survey of Children’s Health found statistically significant increases in the likelihood of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (odds ratio [OR], 1.87), depression (OR, 1.81), anxiety (OR, 1.77), conduct disorder (OR, 1.87), and autism (OR, 3.04).6

Evolving Practices and Therapies

Bathing Practices

There has long been much controversy regarding best bathing habits for patients with AD. In a 2009 study, cutaneous hydration was quantified after various bathing and moisturizing regimens.18 The study showed clear benefits of emollient application on skin hydration, either after bathing or without bathing. Bathing followed by emollient applications did not decrease skin hydration in contrast to bathing without emollient application.18

There are limited studies evaluating bathing frequency in pediatric patients, and many families receive conflicting information regarding best practice. In one study that surveyed 354 parents, more than 75% of parents/guardians who had seen multiple providers for their child’s AD reported a substantial amount of confusion and frustration from conflicting advice on bathing frequency.19 Cardona et al20 undertook a randomized clinical trial of frequent bathing and moisturizing vs less-frequent bathing and moisturizing in pediatric patients with AD aged 6 months to 11 years. Patients were divided into 2 groups: 1 being bathed twice daily with immediate moisturizer application and the other being bathed twice weekly followed by moisturization, then a switch to the other method. Patients used standardized topical corticosteroids (TCSs) in both groups. There were significant improvements in scoring AD and other objective measures during the frequent bathing time period vs infrequent bathing; in the group that bathed more frequently, SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis) decreased by 21.2 compared with the group that bathed less frequently (95% confidence interval, 14.9-27.6; P<.0001). These findings suggest that more-frequent bathing with immediate moisturization is superior as an acute treatment intervention for improving AD disease severity in comparison to less-frequent bathing with immediate moisturization.20

Expanding Treatment Options

Topical Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors

There are several new and evolving topical therapies in AD. Crisaborole ointment 2% is a steroid-free phosphodiesterase inhibitor approved in 2016 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for mild to moderate AD in patients aged 2 years and older. A recent multicenter, open-label, single-arm study in 137 infants (CrisADe CARE 1) evaluated the pharmacokinetics and efficacy of crisaborole ointment 2% applied twice daily for 4 weeks in pediatric patients aged 3 months to less than 24 months of age with mild to moderate AD.21 The study had 2 cohorts: one with a minimum of 5% body surface area involvement and another (the pharmacokinetic cohort) with a minimum of 35% body surface area involvement. Both cohorts demonstrated similar efficacy data. From baseline to day 29, the mean percentage change in eczema area and severity index (EASI) score was −57.5%, and an investigator global assessment (IGA) score of clear or almost clear with at least a 2-grade improvement was achieved in 30.2% of patients. Crisaborole systemic exposures in infants were comparable with those in patients aged 2 years or older. Patients tolerated crisaborole well, with a 4% rate of burning, which was similar to other studies in children and adults but perhaps lower than seen in clinical practice. Pharmacokinetic studies did not show any remarkable noticeable concern with accumulation of propylene glycol absorption.21

Based on the CrisADe CARE 1 study data, in March 2020 the FDA extended the indication of crisaborole ointment 2% from a prior lower age limit of 24 months to approval for use in treating mild to moderate AD in children as young as 3 months, making it the first nonsteroidal topical anti-inflammatory medication to be approved in children younger than 2 years in the United States.

Evolving Topical Therapies

Topical Janus Kinase Inhibitors

Ruxolitinib is a potent inhibitor of Janus kinase 1 (JAK-1) and Janus kinase 2 (JAK-2) and has been developed in topical formulations. In recent phase 3 clinical trials of patients with AD aged 12 years and older with mild to moderate disease (TRuE-AD1 and TRuE-AD2), more than half of the patients treated with either ruxolitinib cream in a 0.75% or 1.5% concentration reached EASI-75 after 8 weeks of treatment.22 Additionally, more patients treated with topical ruxolitinib reached an IGA score of clear to almost clear than patients treated with vehicle at the end of treatment. Thus far, it appears to be very well tolerated, significantly decreases EASI score (P<.0001), and improves overall pruritus.22

Delgocitinib is a topical pan-JAK inhibitor that blocks several cytokine-signaling cascade pathways. It was first developed and approved in Japan in an ointment formulation for use in patients with AD aged 16 years and older.23 The efficacy and safety profile of delgocitinib is currently being evaluated in pediatric patients with AD in Japan. In a recent phase 2 clinical study of 103 Japanese patients aged 2 to 15 years with moderate to severe AD, patients were randomized to receive either delgocitinib ointment in 0.25% or 0.5% concentrations or vehicle ointment twice daily for 4 weeks. The proportion of patients with a modified EASI-75 score was 38.2% (13/34) in the 0.25% group and 50.0% (17/34) in the 0.5% group vs 8.6% (3/35) in the placebo group. More patients treated with delgocitinib ointment received an IGA score of clear or almost clear than patients treated with vehicle at the end of treatment. Overall, both delgocitinib groups demonstrated superior improvement in clinical symptoms and signs without notable side effects.24

Tapinarof

Tapinarof is a topical therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist. In a recent phase 2 randomized study of 2 concentrations and 2 frequencies of tapinarof cream vs vehicle in 247 randomized patients aged 12 to 65 years with moderate to severe disease, tapinarof demonstrated greater success with both concentrations than vehicle at all visits beyond week 2.25 Additionally, in patients treated with tapinarof cream 1%, nearly 50% reached an IGA score of clear to almost clear with at least a 2-grade improvement. More than 50% of patients achieved EASI-75 improvement at 12 weeks of treatment with tapinarof cream 1% used daily. These findings suggest that tapinarof may be an efficacious and well-tolerated treatment for both adolescents and adults with AD; however, large confirmation trials are needed to further investigate.25

Systemic Treatments

Oral JAK Inhibitors

Some of the most exciting novel therapies include several oral JAK inhibitors that target different combinations of kinases and have been shown to decrease AD severity and symptoms. Some of these agents have indications in other disease states, such as baricitinib and upadacitinib, which are both FDA approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, whereas others, such as abrocitinib, have been studied specifically for AD.

Although some agents have only been studied in adults to date, others have included adolescents in their core studies, such as abrocitinib, which received Breakthrough Therapy designation from the FDA for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe AD in February 2018. In recent phase 3 trials of patients aged 12 years and older with moderate to severe AD (JADE MONO-1 and JADE MONO-2), both doses of abrocitinib improved the IGA and EASI-75 outcomes compared with placebo.26 Additional studies will be conducted to further investigate the relative efficacy and safety in patients younger than 18 years.

Biologics

Dupilumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody that inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 signaling without suppressing the immune system. It is approved for use in patients aged 12 years and older with moderate to severe asthma and in adults with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. It is the first biologic to show positive results in the moderate to severe pediatric AD population. There are now extended data available exhibiting sustained benefit in adolescent patients who were continued on dupilumab therapy, evidenced by further improvement in EASI scores at the 1-year mark.27

Recently, dupilumab received approval for use in patients aged 6 to 11 years, making it the first biologic for AD to be approved for use in patients younger than 12 years. The expedited FDA approval was based on the phase 3 results in which the efficacy and safety of dupilumab combined with TCSs were compared to TCSs alone (N=367).28 In this trial, more than twice as many children achieved clear or almost clear skin and more than 4 times as many achieved itch reduction with dupilumab plus TCSs than with TCSs alone. Three-quarters of patients receiving dupilumab at the subsequently approved dosing achieved at least a 75% improvement in overall disease.28 An additional study is being conducted that includes pediatric patients aged 6 months to younger than 6 years (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03346434).

Future Directions in Pediatric AD

Our review summarizes only some of the agents under clinical investigation for use in pediatric AD. Early treatment to establish excellent long-term disease control with aggressive topical regimens or with systemic agents may alter the course of AD and influence the development of comorbidities, though this has not yet been shown in clinical studies. The long-term impact of early treatment, along with many other intriguing issues, will be studied more in the near future.

- Silverberg JI. Public health burden and epidemiology of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:283-289.

- Silverberg JI, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, et al. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in children aged 6–11 years: a cross-sectional study in the United States (US), Canada, Europe, and Japan. Paper presented at: American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting; March 20-24, 2020; Denver, CO.

- McKenzie C, Silverberg JI. The prevalence and persistence of atopic dermatitis in urban United States children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123:173-178.e1.

- Paternoster L, Savenije OEM, Heron J, et al. IJ Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:964-971.

- Silverberg JI, Simpson EL. Association between severe eczema in children and multiple comorbid conditions and increased healthcare utilization. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2013;24:476-486.

- Yaghmaie P, Koudelka CW, Simpson Mental health comorbidity in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:428-433.

- Narla S, Silverberg JI. Association between childhood atopic dermatitis and cutaneous, extracutaneous and systemic infections. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:1467-1468.

- al. Incidence, prevalence, and risk of selected ocular disease in adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:280-286.

- Association of atopic dermatitis with cardiovascular risk factors and diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:1074-1081.

- Major comorbidities of atopic dermatitis: beyond allergic disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:821-838.

- Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.

- Quality of life in families with children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:28-32.

- Assessment of sleep disturbances and exhaustion in mothers of children with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:556-563.

- Association of atopic dermatitis with sleep quality in children.

- Weidinger S, Simpson EL, Eckert L, et al. The patient-reported disease burden in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis: a cross-sectional study in the United States (US), Canada, Europe, and Japan. Paperpresented at: American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting; March 20-24, 2020; Denver, CO.

- The burden of atopic dermatitis: summary of a report for the National Eczema Association. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:26-30.

- Mitchell AE. Bidirectional relationships between psychological health and dermatological conditions in children. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2018;11:289-298.

- Chiang C, Eichenfield LF. Quantitative assessment of combination bathing and moisturizing regimens on skin hydration in atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:273-278.

- Kempe E, Jain N, Cardona I. Bathing frequency recommendations for pediatric atopic dermatitis: are we adding to parental frustration? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;111:298‐299.

- Cardona ID, Kempe EE, Lary C, et al. Frequent versus infrequent bathing in pediatric atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:1014‐1021.

- Gower , Safety, effectiveness, and pharmacokinetics of crisaborole in infants aged 3 to <24 months with mild‐to‐moderate atopic dermatitis: a phase IV open‐label study (CrisADe CARE 1). Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:275-284.

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment atopic dermatitis: results from two phase 3, randomized, double-blind studies. Presented at: 2nd Annual Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis Conference; April 5, 2020; Chicago, IL.

- Dhillon S. Delgocitinib: first approval. Drugs. 2020;80:609‐615.

- Nakagawa H, Nemoto O, Igarashi A, et al. Phase 2 clinical study of delgocitinib ointment in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144:1575‐1583.

- Peppers J, Paller AS, Maeda-Chubachi T, et al. A phase 2, randomized dose-finding study of tapinarof (GSK2894512 cream) for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:89‐98.e3.

- Simpson EL, Sinclair R, Forman S, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (JADE MONO-1): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396:255-266.

- Cork MJ, Thaçi D, Eichenfield LF, et al. Dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from a phase IIa open-label trial and subsequent phase III open-label extension. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:85‐96.

- Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Thaçi D, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial [published online June 20, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.054.

- Silverberg JI. Public health burden and epidemiology of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:283-289.

- Silverberg JI, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, et al. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in children aged 6–11 years: a cross-sectional study in the United States (US), Canada, Europe, and Japan. Paper presented at: American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting; March 20-24, 2020; Denver, CO.

- McKenzie C, Silverberg JI. The prevalence and persistence of atopic dermatitis in urban United States children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123:173-178.e1.

- Paternoster L, Savenije OEM, Heron J, et al. IJ Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:964-971.

- Silverberg JI, Simpson EL. Association between severe eczema in children and multiple comorbid conditions and increased healthcare utilization. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2013;24:476-486.

- Yaghmaie P, Koudelka CW, Simpson Mental health comorbidity in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:428-433.

- Narla S, Silverberg JI. Association between childhood atopic dermatitis and cutaneous, extracutaneous and systemic infections. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:1467-1468.

- al. Incidence, prevalence, and risk of selected ocular disease in adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:280-286.

- Association of atopic dermatitis with cardiovascular risk factors and diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:1074-1081.

- Major comorbidities of atopic dermatitis: beyond allergic disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:821-838.

- Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.

- Quality of life in families with children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:28-32.

- Assessment of sleep disturbances and exhaustion in mothers of children with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:556-563.

- Association of atopic dermatitis with sleep quality in children.

- Weidinger S, Simpson EL, Eckert L, et al. The patient-reported disease burden in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis: a cross-sectional study in the United States (US), Canada, Europe, and Japan. Paperpresented at: American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting; March 20-24, 2020; Denver, CO.

- The burden of atopic dermatitis: summary of a report for the National Eczema Association. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:26-30.

- Mitchell AE. Bidirectional relationships between psychological health and dermatological conditions in children. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2018;11:289-298.

- Chiang C, Eichenfield LF. Quantitative assessment of combination bathing and moisturizing regimens on skin hydration in atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:273-278.

- Kempe E, Jain N, Cardona I. Bathing frequency recommendations for pediatric atopic dermatitis: are we adding to parental frustration? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;111:298‐299.

- Cardona ID, Kempe EE, Lary C, et al. Frequent versus infrequent bathing in pediatric atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:1014‐1021.

- Gower , Safety, effectiveness, and pharmacokinetics of crisaborole in infants aged 3 to <24 months with mild‐to‐moderate atopic dermatitis: a phase IV open‐label study (CrisADe CARE 1). Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:275-284.

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment atopic dermatitis: results from two phase 3, randomized, double-blind studies. Presented at: 2nd Annual Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis Conference; April 5, 2020; Chicago, IL.

- Dhillon S. Delgocitinib: first approval. Drugs. 2020;80:609‐615.

- Nakagawa H, Nemoto O, Igarashi A, et al. Phase 2 clinical study of delgocitinib ointment in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144:1575‐1583.

- Peppers J, Paller AS, Maeda-Chubachi T, et al. A phase 2, randomized dose-finding study of tapinarof (GSK2894512 cream) for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:89‐98.e3.