User login

Lupus Erythematosus Tumidus of the Scalp Masquerading as Alopecia Areata

Lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) is a relatively rare condition but may simply be underdiagnosed in the literature. It presents as urticarialike papules and plaques in sun-exposed areas, characterized by induration and erythema. Lesions occur on the face, neck, upper extremities, and trunk and heal without scarring.1,2 Rarely, lesions can show fine scaling and associated pruritus, but most often the lesions are asymptomatic.3

Case Report

A 45-year-old woman presented with 2 asymptomatic self-described bald spots on the top of the head of 2 months’ duration. The patient denied prior treatment of the lesions and noted one patch was resolving. She reported no involvement of the eyebrows, eyelashes, and axillary and pubic hair. A review of systems was negative. The patient denied personal or family history of lupus, thyroid disease, or vitiligo.

Clinical examination revealed a 1.1-cm round patch of nonscarring alopecia on the right vertex scalp and a 0.9-cm round patch of nonscarring alopecia with moderate hair regrowth on the left vertex scalp. There was no erythema, scaling, or induration. The rest of the scalp was normal in appearance and the eyebrows and eyelashes were uninvolved. The patient was diagnosed with alopecia areata and was treated with 10 mg/mL of intralesional triamcinolone once monthly for 4 months.

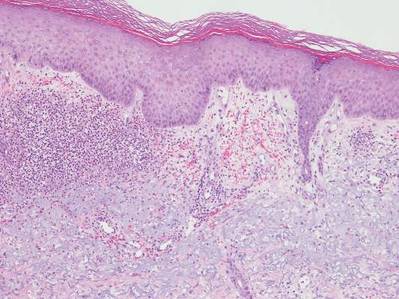

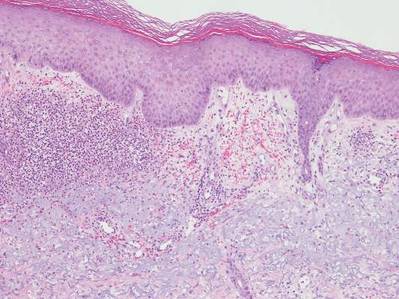

The patient initially showed improvement with moderate hair regrowth. After 4 months of treatment, she developed 3 new 1- to 1.5-cm erythematous alopecic patches on the vertex scalp and had worsening in the initial patches (Figure 1). Given the resistance to standard therapy and the onset of multiple new areas with evidence of inflammatory involvement, a punch biopsy was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed a fairly unremarkable epidermis and a dense dermal inflammatory infiltrate that was present both in the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 2). The inflammatory cells, which appeared to be predominantly comprised of lymphocytes, had a predilection for the vasculature but also were observed within the interstitial dermis. Additionally, mucin appeared to be slightly increased in the deep dermis. The lymphocytic phenotype was confirmed by immunohistochemical studies for CD20 and CD3. The most likely possibilities for this reaction pattern were LET, Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate of the skin (JLIS), gyrate erythema, and lymphoma; however, the immunohistochemical studies effectively ruled out lymphoma. Additionally, there was pronounced dermal mucin noted in the specimen. The patient was diagnosed with LET of the scalp based on the constellation of findings.

Comment

The classification of LET as a single unique entity or disease process sui generis has been in flux in the last decade. Its similarities to JLIS and other forms of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE) have brought debate.4-6 In 1930, Gougerot and Burnier7 documented the first case of LET in the literature, describing smooth, infiltrated, erythematous lesions with no desquamation or other superficial changes seen in 5 patients.

In 2000, interest in LET and other forms of CCLE was increasing, and reports in the literature paralleled. That year, Kuhn et al4 reported 40 cases of LET, characterizing the clinical and histological features of each case to demonstrate that LET should be separate from other forms of CCLE. Until then, it is likely that many lesions that should have been classified as LET were instead classified as various forms of CCLE. The investigators maintained that LET also should be distinct from JLIS because it is associated with UV exposure.4 Kuhn et al8 reviewed phototesting in 60 patients with LET in 2001 and confirmed this subset was the most photosensitive type of lupus erythematosus.

In general, the histopathologic and immunohistochemical studies in LET and JLIS can be quite similar. Relatively distinguishing histopathologic findings in JLIS include no evidence of epidermal atrophy, basal vacuolar change, or follicular plugging, as well as negative immunofluorescence studies. Both entities show a predominantly T-cell population with a smaller component of B cells and thus a distinction cannot be made based on relative proportions of T and B cells in lesions.2

In 2003, Alexiades-Armenakas et al6 determined immunohistochemical criteria for LET, finding a predominance of T cells and more CD4 lymphocytes than CD8 lymphocytes with a mean ratio of roughly 3 to 1. Their study results maintained LET should be classified as a form of CCLE due to the chronicity of the lesions, the serologic profile with negative anti–double-stranded DNA, anticentromere, anti-Smith, anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A, anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B, and anti-nuclear ribonucleoprotein antibodies and the rare association with systemic disease.6 This conclusion was further solidified by a review published that same year citing unique histopathological features when compared to subacute cutaneous LE and discoid lupus erythematosus.5

This case illustrates the importance of histologic evaluation in determining the correct diagnosis in a patient with alopecia areata recalcitrant to treatment. Including LET in the differential of alopecic patches on the scalp could prove beneficial for patients, as LET responds well to antimalarial drugs and photoprotection.9 This patient had a normal antinuclear antibody panel and no signs or symptoms of systemic lupus. It was recommended that she avoid sun exposure and begin treatment with hydroxychloroquine but she declined. At a follow-up visit 6 months later she reported the lesions had improved, but a permanent wig had been sewn over the area, so it could not be examined.

- Lee L, Werth V. Rheumatologic disease. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Mosby Elsevier; 2008:615-629.

- Weedon D. The lichenoid reaction pattern. In: Weedon D. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:35-70.

- Dekle CL, Mannes KD, Davis LS, et al. Lupus tumidus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:250-253.

- Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus—a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

- Kuhn A, Sonntag M, Ruzicka T, et al. Histopathologic findings in lupus erythematosus tumidus: review of 80 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:901-908.

- Alexiades-Armenakas MR, Baldassano M, Bince B, et al. Tumid lupus erythematosus: criteria for classification with immunohistochemical analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:494-500.

- Gougerot H, Burnier R. Lupuse rythe mateux “tumidus.” Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syph. 1930;37:1291-1292.

- Kuhn A, Sonntag M, Richter-Hintz D, et al. Phototesting in lupus erythematosus tumidus—review of 60 patients. Photochem Photobiol. 2001;73:532-536.

- Cozzani E, Christana K, Rongioletti F, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: clinical, histopathological and serological aspects and therapy response of 21 patients. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:797-801.

Lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) is a relatively rare condition but may simply be underdiagnosed in the literature. It presents as urticarialike papules and plaques in sun-exposed areas, characterized by induration and erythema. Lesions occur on the face, neck, upper extremities, and trunk and heal without scarring.1,2 Rarely, lesions can show fine scaling and associated pruritus, but most often the lesions are asymptomatic.3

Case Report

A 45-year-old woman presented with 2 asymptomatic self-described bald spots on the top of the head of 2 months’ duration. The patient denied prior treatment of the lesions and noted one patch was resolving. She reported no involvement of the eyebrows, eyelashes, and axillary and pubic hair. A review of systems was negative. The patient denied personal or family history of lupus, thyroid disease, or vitiligo.

Clinical examination revealed a 1.1-cm round patch of nonscarring alopecia on the right vertex scalp and a 0.9-cm round patch of nonscarring alopecia with moderate hair regrowth on the left vertex scalp. There was no erythema, scaling, or induration. The rest of the scalp was normal in appearance and the eyebrows and eyelashes were uninvolved. The patient was diagnosed with alopecia areata and was treated with 10 mg/mL of intralesional triamcinolone once monthly for 4 months.

The patient initially showed improvement with moderate hair regrowth. After 4 months of treatment, she developed 3 new 1- to 1.5-cm erythematous alopecic patches on the vertex scalp and had worsening in the initial patches (Figure 1). Given the resistance to standard therapy and the onset of multiple new areas with evidence of inflammatory involvement, a punch biopsy was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed a fairly unremarkable epidermis and a dense dermal inflammatory infiltrate that was present both in the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 2). The inflammatory cells, which appeared to be predominantly comprised of lymphocytes, had a predilection for the vasculature but also were observed within the interstitial dermis. Additionally, mucin appeared to be slightly increased in the deep dermis. The lymphocytic phenotype was confirmed by immunohistochemical studies for CD20 and CD3. The most likely possibilities for this reaction pattern were LET, Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate of the skin (JLIS), gyrate erythema, and lymphoma; however, the immunohistochemical studies effectively ruled out lymphoma. Additionally, there was pronounced dermal mucin noted in the specimen. The patient was diagnosed with LET of the scalp based on the constellation of findings.

Comment

The classification of LET as a single unique entity or disease process sui generis has been in flux in the last decade. Its similarities to JLIS and other forms of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE) have brought debate.4-6 In 1930, Gougerot and Burnier7 documented the first case of LET in the literature, describing smooth, infiltrated, erythematous lesions with no desquamation or other superficial changes seen in 5 patients.

In 2000, interest in LET and other forms of CCLE was increasing, and reports in the literature paralleled. That year, Kuhn et al4 reported 40 cases of LET, characterizing the clinical and histological features of each case to demonstrate that LET should be separate from other forms of CCLE. Until then, it is likely that many lesions that should have been classified as LET were instead classified as various forms of CCLE. The investigators maintained that LET also should be distinct from JLIS because it is associated with UV exposure.4 Kuhn et al8 reviewed phototesting in 60 patients with LET in 2001 and confirmed this subset was the most photosensitive type of lupus erythematosus.

In general, the histopathologic and immunohistochemical studies in LET and JLIS can be quite similar. Relatively distinguishing histopathologic findings in JLIS include no evidence of epidermal atrophy, basal vacuolar change, or follicular plugging, as well as negative immunofluorescence studies. Both entities show a predominantly T-cell population with a smaller component of B cells and thus a distinction cannot be made based on relative proportions of T and B cells in lesions.2

In 2003, Alexiades-Armenakas et al6 determined immunohistochemical criteria for LET, finding a predominance of T cells and more CD4 lymphocytes than CD8 lymphocytes with a mean ratio of roughly 3 to 1. Their study results maintained LET should be classified as a form of CCLE due to the chronicity of the lesions, the serologic profile with negative anti–double-stranded DNA, anticentromere, anti-Smith, anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A, anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B, and anti-nuclear ribonucleoprotein antibodies and the rare association with systemic disease.6 This conclusion was further solidified by a review published that same year citing unique histopathological features when compared to subacute cutaneous LE and discoid lupus erythematosus.5

This case illustrates the importance of histologic evaluation in determining the correct diagnosis in a patient with alopecia areata recalcitrant to treatment. Including LET in the differential of alopecic patches on the scalp could prove beneficial for patients, as LET responds well to antimalarial drugs and photoprotection.9 This patient had a normal antinuclear antibody panel and no signs or symptoms of systemic lupus. It was recommended that she avoid sun exposure and begin treatment with hydroxychloroquine but she declined. At a follow-up visit 6 months later she reported the lesions had improved, but a permanent wig had been sewn over the area, so it could not be examined.

Lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) is a relatively rare condition but may simply be underdiagnosed in the literature. It presents as urticarialike papules and plaques in sun-exposed areas, characterized by induration and erythema. Lesions occur on the face, neck, upper extremities, and trunk and heal without scarring.1,2 Rarely, lesions can show fine scaling and associated pruritus, but most often the lesions are asymptomatic.3

Case Report

A 45-year-old woman presented with 2 asymptomatic self-described bald spots on the top of the head of 2 months’ duration. The patient denied prior treatment of the lesions and noted one patch was resolving. She reported no involvement of the eyebrows, eyelashes, and axillary and pubic hair. A review of systems was negative. The patient denied personal or family history of lupus, thyroid disease, or vitiligo.

Clinical examination revealed a 1.1-cm round patch of nonscarring alopecia on the right vertex scalp and a 0.9-cm round patch of nonscarring alopecia with moderate hair regrowth on the left vertex scalp. There was no erythema, scaling, or induration. The rest of the scalp was normal in appearance and the eyebrows and eyelashes were uninvolved. The patient was diagnosed with alopecia areata and was treated with 10 mg/mL of intralesional triamcinolone once monthly for 4 months.

The patient initially showed improvement with moderate hair regrowth. After 4 months of treatment, she developed 3 new 1- to 1.5-cm erythematous alopecic patches on the vertex scalp and had worsening in the initial patches (Figure 1). Given the resistance to standard therapy and the onset of multiple new areas with evidence of inflammatory involvement, a punch biopsy was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed a fairly unremarkable epidermis and a dense dermal inflammatory infiltrate that was present both in the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 2). The inflammatory cells, which appeared to be predominantly comprised of lymphocytes, had a predilection for the vasculature but also were observed within the interstitial dermis. Additionally, mucin appeared to be slightly increased in the deep dermis. The lymphocytic phenotype was confirmed by immunohistochemical studies for CD20 and CD3. The most likely possibilities for this reaction pattern were LET, Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate of the skin (JLIS), gyrate erythema, and lymphoma; however, the immunohistochemical studies effectively ruled out lymphoma. Additionally, there was pronounced dermal mucin noted in the specimen. The patient was diagnosed with LET of the scalp based on the constellation of findings.

Comment

The classification of LET as a single unique entity or disease process sui generis has been in flux in the last decade. Its similarities to JLIS and other forms of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE) have brought debate.4-6 In 1930, Gougerot and Burnier7 documented the first case of LET in the literature, describing smooth, infiltrated, erythematous lesions with no desquamation or other superficial changes seen in 5 patients.

In 2000, interest in LET and other forms of CCLE was increasing, and reports in the literature paralleled. That year, Kuhn et al4 reported 40 cases of LET, characterizing the clinical and histological features of each case to demonstrate that LET should be separate from other forms of CCLE. Until then, it is likely that many lesions that should have been classified as LET were instead classified as various forms of CCLE. The investigators maintained that LET also should be distinct from JLIS because it is associated with UV exposure.4 Kuhn et al8 reviewed phototesting in 60 patients with LET in 2001 and confirmed this subset was the most photosensitive type of lupus erythematosus.

In general, the histopathologic and immunohistochemical studies in LET and JLIS can be quite similar. Relatively distinguishing histopathologic findings in JLIS include no evidence of epidermal atrophy, basal vacuolar change, or follicular plugging, as well as negative immunofluorescence studies. Both entities show a predominantly T-cell population with a smaller component of B cells and thus a distinction cannot be made based on relative proportions of T and B cells in lesions.2

In 2003, Alexiades-Armenakas et al6 determined immunohistochemical criteria for LET, finding a predominance of T cells and more CD4 lymphocytes than CD8 lymphocytes with a mean ratio of roughly 3 to 1. Their study results maintained LET should be classified as a form of CCLE due to the chronicity of the lesions, the serologic profile with negative anti–double-stranded DNA, anticentromere, anti-Smith, anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A, anti-La/Sjögren syndrome antigen B, and anti-nuclear ribonucleoprotein antibodies and the rare association with systemic disease.6 This conclusion was further solidified by a review published that same year citing unique histopathological features when compared to subacute cutaneous LE and discoid lupus erythematosus.5

This case illustrates the importance of histologic evaluation in determining the correct diagnosis in a patient with alopecia areata recalcitrant to treatment. Including LET in the differential of alopecic patches on the scalp could prove beneficial for patients, as LET responds well to antimalarial drugs and photoprotection.9 This patient had a normal antinuclear antibody panel and no signs or symptoms of systemic lupus. It was recommended that she avoid sun exposure and begin treatment with hydroxychloroquine but she declined. At a follow-up visit 6 months later she reported the lesions had improved, but a permanent wig had been sewn over the area, so it could not be examined.

- Lee L, Werth V. Rheumatologic disease. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Mosby Elsevier; 2008:615-629.

- Weedon D. The lichenoid reaction pattern. In: Weedon D. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:35-70.

- Dekle CL, Mannes KD, Davis LS, et al. Lupus tumidus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:250-253.

- Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus—a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

- Kuhn A, Sonntag M, Ruzicka T, et al. Histopathologic findings in lupus erythematosus tumidus: review of 80 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:901-908.

- Alexiades-Armenakas MR, Baldassano M, Bince B, et al. Tumid lupus erythematosus: criteria for classification with immunohistochemical analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:494-500.

- Gougerot H, Burnier R. Lupuse rythe mateux “tumidus.” Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syph. 1930;37:1291-1292.

- Kuhn A, Sonntag M, Richter-Hintz D, et al. Phototesting in lupus erythematosus tumidus—review of 60 patients. Photochem Photobiol. 2001;73:532-536.

- Cozzani E, Christana K, Rongioletti F, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: clinical, histopathological and serological aspects and therapy response of 21 patients. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:797-801.

- Lee L, Werth V. Rheumatologic disease. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Mosby Elsevier; 2008:615-629.

- Weedon D. The lichenoid reaction pattern. In: Weedon D. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:35-70.

- Dekle CL, Mannes KD, Davis LS, et al. Lupus tumidus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:250-253.

- Kuhn A, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus—a neglected subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 40 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1033-1041.

- Kuhn A, Sonntag M, Ruzicka T, et al. Histopathologic findings in lupus erythematosus tumidus: review of 80 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:901-908.

- Alexiades-Armenakas MR, Baldassano M, Bince B, et al. Tumid lupus erythematosus: criteria for classification with immunohistochemical analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:494-500.

- Gougerot H, Burnier R. Lupuse rythe mateux “tumidus.” Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syph. 1930;37:1291-1292.

- Kuhn A, Sonntag M, Richter-Hintz D, et al. Phototesting in lupus erythematosus tumidus—review of 60 patients. Photochem Photobiol. 2001;73:532-536.

- Cozzani E, Christana K, Rongioletti F, et al. Lupus erythematosus tumidus: clinical, histopathological and serological aspects and therapy response of 21 patients. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:797-801.

Practice Points

- Lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) of the scalp can mimic alopecia areata on clinical presentation.

- A unique variant of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, LET presents in sun-exposed areas without any corresponding systemic signs.

- Lupus erythematosus tumidus may respond well to antimalarial drugs.

Itchy Papules and Plaques on the Dorsal Hands

The Diagnosis: Neutrophilic Dermatosis of the Dorsal Hands

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH) is considered to be an uncommon localized variant of Sweet syndrome (SS). The term pustular vasculitis originally was used to describe this condition by Strutton et al1 in 1995 due to the presence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histology. In 2000, Galaria et al2 suggested this eruption was a localized variant of SS based on clinical presentations that demonstrated associated fever and lack of necrotizing vasculitis and proposed the term neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands to describe the condition. Cases of similar cutaneous eruptions on the hands associated with fever, leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and leukocytoclasis have since been reported.3-5 Some authors have concluded that these eruptions, previously termed atypical pyoderma gangrenosum and pustular vasculitis of the hands, represent a single disease entity and should be designated as NDDH.3,4

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands characteristically presents with hemorrhagic pustular ulcerations limited to or predominantly located on the dorsal hands, as seen in our patient. Histopathologically, NDDH demonstrates a neutrophil-predominant infiltrate of the upper dermis and marked papillary dermal edema; a punch biopsy specimen from our patient was consistent with these features (Figure). Two punch biopsies were performed and were negative for fungus and acid-fast bacteria and positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Vasculitis, if present, is more commonly seen in eruptions of longer duration (ie, months to years) and is thought to be secondary to the dense neutrophilic infiltrate and not a primary vasculitis.3,6,7 Similar to classic SS, NDDH is inherently responsive to corticosteroid therapy. Successful treatment also has been reported with dapsone, colchicine, sulfapyridine, potassium iodide, intralesional and topical corticosteroids, and topical tacrolimus.2-8 Oral minocycline has shown variable results.3,4

Numerous case series have demonstrated that a majority of cases of NDDH are associated with hematologic or solid organ malignancies, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), inflammatory bowel disease, or other underlying systemic diseases.3,5,9 It is important for dermatologists to recognize NDDH, distinguish it from localized infection, and perform the appropriate workup (eg, basic laboratory tests [complete blood count, complete metabolic panel], age-appropriate malignancy screening, colonoscopy, bone marrow biopsy) to exclude associated systemic diseases.

Our patient demonstrated characteristic clinical and histopathologic findings of NDDH in association with early MDS and possible common bile duct (CBD) malignancy. The lesions showed a rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy. The initial differential diagnoses included NDDH or other neutrophilic dermatosis, phototoxic drug eruption, and atypical mycobacterial or fungal infection (cultures were negative in our patient). Physical examination and histopathologic findings along with the patient’s clinical course and rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy supported the diagnosis of NDDH. Our patient’s multiple comorbidities, including macrocytic anemia, MDS, and potential CBD malignancy, presented a therapeutic challenge. Oral dapsone, an ideal steroid-sparing agent for neutrophilic dermatoses including NDDH, was avoided given its associated hematologic side effects including hemolysis, methemoglobinemia, and possible agranulocytosis. To date, the patient has not received any further treatment for MDS or the CBD mass and continues regular follow-up with hematology, gastroenterology, and dermatology.

This case highlights the importance of including NDDH in the differential diagnosis of papules and plaques on the hands, especially in patients with known malignancies, and emphasizes the association of neutrophilic dermatoses with malignancy and systemic disease.

- Strutton G, Weedon D, Robertson I. Pustular vasculitis of the hands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:192-198.

- Galaria NA, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Kligman D, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: pustular vasculitis revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:870-874.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM. Neutrophilic dermatosis (pustular vasculitis) of the dorsal hands. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:361-365.

- Weening RH, Bruce AJ, McEvoy MT, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: four new cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:95-102.

- Malone JC, Slone SP, Wills-Frank LA, et al. Vascular inflammation (vasculitis) in Sweet syndrome: a clinicopathologic study of 28 biopsy specimens from 21 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:345-349.

- Cohen PR. Skin lesions of Sweet syndrome and its dorsal hand variant contain vasculitis: an oxymoron or an epiphenomenon? Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:400-403.

- Del Pozo J, Sacristán F, Martínez W, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: presentation of eight cases and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2007;34:243-247.

- Callen JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:409-419.

The Diagnosis: Neutrophilic Dermatosis of the Dorsal Hands

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH) is considered to be an uncommon localized variant of Sweet syndrome (SS). The term pustular vasculitis originally was used to describe this condition by Strutton et al1 in 1995 due to the presence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histology. In 2000, Galaria et al2 suggested this eruption was a localized variant of SS based on clinical presentations that demonstrated associated fever and lack of necrotizing vasculitis and proposed the term neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands to describe the condition. Cases of similar cutaneous eruptions on the hands associated with fever, leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and leukocytoclasis have since been reported.3-5 Some authors have concluded that these eruptions, previously termed atypical pyoderma gangrenosum and pustular vasculitis of the hands, represent a single disease entity and should be designated as NDDH.3,4

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands characteristically presents with hemorrhagic pustular ulcerations limited to or predominantly located on the dorsal hands, as seen in our patient. Histopathologically, NDDH demonstrates a neutrophil-predominant infiltrate of the upper dermis and marked papillary dermal edema; a punch biopsy specimen from our patient was consistent with these features (Figure). Two punch biopsies were performed and were negative for fungus and acid-fast bacteria and positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Vasculitis, if present, is more commonly seen in eruptions of longer duration (ie, months to years) and is thought to be secondary to the dense neutrophilic infiltrate and not a primary vasculitis.3,6,7 Similar to classic SS, NDDH is inherently responsive to corticosteroid therapy. Successful treatment also has been reported with dapsone, colchicine, sulfapyridine, potassium iodide, intralesional and topical corticosteroids, and topical tacrolimus.2-8 Oral minocycline has shown variable results.3,4

Numerous case series have demonstrated that a majority of cases of NDDH are associated with hematologic or solid organ malignancies, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), inflammatory bowel disease, or other underlying systemic diseases.3,5,9 It is important for dermatologists to recognize NDDH, distinguish it from localized infection, and perform the appropriate workup (eg, basic laboratory tests [complete blood count, complete metabolic panel], age-appropriate malignancy screening, colonoscopy, bone marrow biopsy) to exclude associated systemic diseases.

Our patient demonstrated characteristic clinical and histopathologic findings of NDDH in association with early MDS and possible common bile duct (CBD) malignancy. The lesions showed a rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy. The initial differential diagnoses included NDDH or other neutrophilic dermatosis, phototoxic drug eruption, and atypical mycobacterial or fungal infection (cultures were negative in our patient). Physical examination and histopathologic findings along with the patient’s clinical course and rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy supported the diagnosis of NDDH. Our patient’s multiple comorbidities, including macrocytic anemia, MDS, and potential CBD malignancy, presented a therapeutic challenge. Oral dapsone, an ideal steroid-sparing agent for neutrophilic dermatoses including NDDH, was avoided given its associated hematologic side effects including hemolysis, methemoglobinemia, and possible agranulocytosis. To date, the patient has not received any further treatment for MDS or the CBD mass and continues regular follow-up with hematology, gastroenterology, and dermatology.

This case highlights the importance of including NDDH in the differential diagnosis of papules and plaques on the hands, especially in patients with known malignancies, and emphasizes the association of neutrophilic dermatoses with malignancy and systemic disease.

The Diagnosis: Neutrophilic Dermatosis of the Dorsal Hands

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH) is considered to be an uncommon localized variant of Sweet syndrome (SS). The term pustular vasculitis originally was used to describe this condition by Strutton et al1 in 1995 due to the presence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histology. In 2000, Galaria et al2 suggested this eruption was a localized variant of SS based on clinical presentations that demonstrated associated fever and lack of necrotizing vasculitis and proposed the term neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands to describe the condition. Cases of similar cutaneous eruptions on the hands associated with fever, leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and leukocytoclasis have since been reported.3-5 Some authors have concluded that these eruptions, previously termed atypical pyoderma gangrenosum and pustular vasculitis of the hands, represent a single disease entity and should be designated as NDDH.3,4

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands characteristically presents with hemorrhagic pustular ulcerations limited to or predominantly located on the dorsal hands, as seen in our patient. Histopathologically, NDDH demonstrates a neutrophil-predominant infiltrate of the upper dermis and marked papillary dermal edema; a punch biopsy specimen from our patient was consistent with these features (Figure). Two punch biopsies were performed and were negative for fungus and acid-fast bacteria and positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Vasculitis, if present, is more commonly seen in eruptions of longer duration (ie, months to years) and is thought to be secondary to the dense neutrophilic infiltrate and not a primary vasculitis.3,6,7 Similar to classic SS, NDDH is inherently responsive to corticosteroid therapy. Successful treatment also has been reported with dapsone, colchicine, sulfapyridine, potassium iodide, intralesional and topical corticosteroids, and topical tacrolimus.2-8 Oral minocycline has shown variable results.3,4

Numerous case series have demonstrated that a majority of cases of NDDH are associated with hematologic or solid organ malignancies, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), inflammatory bowel disease, or other underlying systemic diseases.3,5,9 It is important for dermatologists to recognize NDDH, distinguish it from localized infection, and perform the appropriate workup (eg, basic laboratory tests [complete blood count, complete metabolic panel], age-appropriate malignancy screening, colonoscopy, bone marrow biopsy) to exclude associated systemic diseases.

Our patient demonstrated characteristic clinical and histopathologic findings of NDDH in association with early MDS and possible common bile duct (CBD) malignancy. The lesions showed a rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy. The initial differential diagnoses included NDDH or other neutrophilic dermatosis, phototoxic drug eruption, and atypical mycobacterial or fungal infection (cultures were negative in our patient). Physical examination and histopathologic findings along with the patient’s clinical course and rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy supported the diagnosis of NDDH. Our patient’s multiple comorbidities, including macrocytic anemia, MDS, and potential CBD malignancy, presented a therapeutic challenge. Oral dapsone, an ideal steroid-sparing agent for neutrophilic dermatoses including NDDH, was avoided given its associated hematologic side effects including hemolysis, methemoglobinemia, and possible agranulocytosis. To date, the patient has not received any further treatment for MDS or the CBD mass and continues regular follow-up with hematology, gastroenterology, and dermatology.

This case highlights the importance of including NDDH in the differential diagnosis of papules and plaques on the hands, especially in patients with known malignancies, and emphasizes the association of neutrophilic dermatoses with malignancy and systemic disease.

- Strutton G, Weedon D, Robertson I. Pustular vasculitis of the hands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:192-198.

- Galaria NA, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Kligman D, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: pustular vasculitis revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:870-874.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM. Neutrophilic dermatosis (pustular vasculitis) of the dorsal hands. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:361-365.

- Weening RH, Bruce AJ, McEvoy MT, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: four new cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:95-102.

- Malone JC, Slone SP, Wills-Frank LA, et al. Vascular inflammation (vasculitis) in Sweet syndrome: a clinicopathologic study of 28 biopsy specimens from 21 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:345-349.

- Cohen PR. Skin lesions of Sweet syndrome and its dorsal hand variant contain vasculitis: an oxymoron or an epiphenomenon? Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:400-403.

- Del Pozo J, Sacristán F, Martínez W, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: presentation of eight cases and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2007;34:243-247.

- Callen JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:409-419.

- Strutton G, Weedon D, Robertson I. Pustular vasculitis of the hands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:192-198.

- Galaria NA, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Kligman D, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: pustular vasculitis revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:870-874.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM. Neutrophilic dermatosis (pustular vasculitis) of the dorsal hands. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:361-365.

- Weening RH, Bruce AJ, McEvoy MT, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: four new cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:95-102.

- Malone JC, Slone SP, Wills-Frank LA, et al. Vascular inflammation (vasculitis) in Sweet syndrome: a clinicopathologic study of 28 biopsy specimens from 21 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:345-349.

- Cohen PR. Skin lesions of Sweet syndrome and its dorsal hand variant contain vasculitis: an oxymoron or an epiphenomenon? Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:400-403.

- Del Pozo J, Sacristán F, Martínez W, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: presentation of eight cases and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2007;34:243-247.

- Callen JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:409-419.

A 69-year-old man presented with tender, itchy papules and plaques on the bilateral dorsal hands of 2 months’ duration. The plaques had started as small papules that gradually enlarged and then became ulcerated. The patient denied prior trauma or constitutional symptoms. Laboratory testing revealed macrocytic anemia, thrombocytosis, and hypoalbuminemia. A complete blood count and complete metabolic panel were otherwise unremarkable. A recent bone marrow biopsy for macrocytic anemia performed prior to the current presentation suggested early myelodysplastic syndrome, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography revealed a large mass in the common bile duct that was suspicious for malignancy. Two punch biopsies were performed and were negative for fungus and acid-fast bacteria and positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Treatment with topical clobetasol 0.05% twice daily was initiated with complete healing of the plaques on the hands after 2 weeks of use; however, the patient continued to develop new ulcerated papulonodules distally.