User login

Solitary Papule on the Nose

The Diagnosis: Sclerosing Perineurioma

Sclerosing perineurioma, first described in 1997 by Fetsch and Miettinen,1 is a subtype of perineurioma with a strong predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Rare cases involving extra-acral sites including the forearm, elbow, axilla, back, neck, lower leg, thigh, knee, lips, nose, and mouth have been reported.2-4 Perineurioma is a relatively uncommon and benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor with exclusive perineurial differentiation.5 Perineurioma is divided into intraneural and extraneural types; the latter are further subclassified into soft tissue, sclerosing, reticular, and plexiform types. Other rare forms include the sclerosing, Pacinian corpuscle-like perineurioma, lipomatous perineurioma, perineurioma with xanthomatous areas, and perineurioma with granular cells.6,7

Clinically, sclerosing perineurioma usually presents as a solitary lesion; however, rare cases of multiple lesions have been reported.8 Our patient presented with a solitary papule on the nose. Histopathologically, sclerosing perineurioma demonstrates slender spindle cells in a whorled growth pattern (onion skin) embedded in a hyalinized, lamellar, and dense collagenous stroma with intervening cleftlike spaces. Immunohistochemically, the spindle cells of our case stained positive for epithelial membrane antigen (quiz images). Other positive immunostains for perineurioma include claudin-1 and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1). Perineurioma lacks expression of S-100 but can express CD34.2 As a benign tumor, the prognosis of sclerosing perineurioma is excellent. Complete local excision is considered curative.1

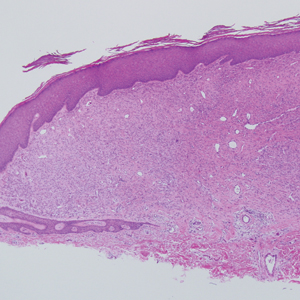

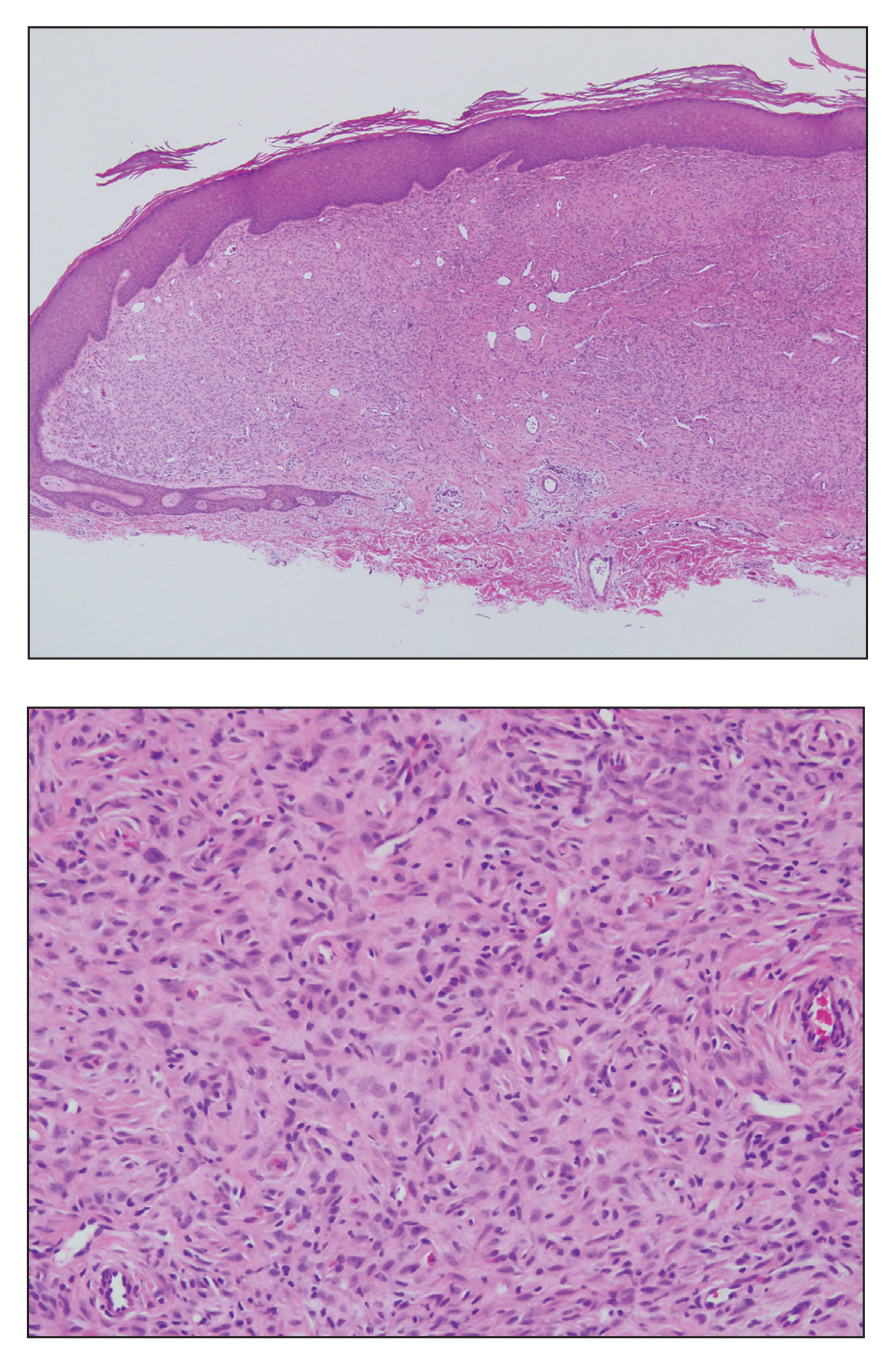

Angiofibroma, also known as fibrous papule, is a common and benign lesion located primarily on or in close proximity to the nose.9 Angiofibromas can be associated with genodermatoses such as tuberous sclerosis, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, or Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. When angiofibromas involve the penis, they are called pearly penile papules. Ungual angiofibroma, also known as Koenen tumor, occurs underneath the nail.10-12 Both facial angiofibromas (>3) and ungual angiofibromas (>2) are independent major criteria for tuberous sclerosis.13 Clinically, angiofibroma presents as a small, dome-shaped, pink papule arising on the lower portion of the nose or nearby area of the central face. Histopathologically, angiofibromas classically demonstrate increased dilated vessels and fibrosis in the dermis. Stellate, plump, spindle-shaped, and multinucleated cells can be seen in the collagenous stroma. The collagen fibers around hair follicles are arranged concentrically, resulting in an onion skin-like appearance. The epidermal rete ridges can be effaced (Figure 1). Increased numbers of single-unit melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction can be seen in some cases. Immunohistochemically, a variable number of spindled and multinucleated cells in the dermis stain with factor XIIIa. There are at least 7 histologic variants of angiofibroma including hypercellular, pigmented, inflammatory, pleomorphic, clear cell, granular cell, and epithelioid.9,14

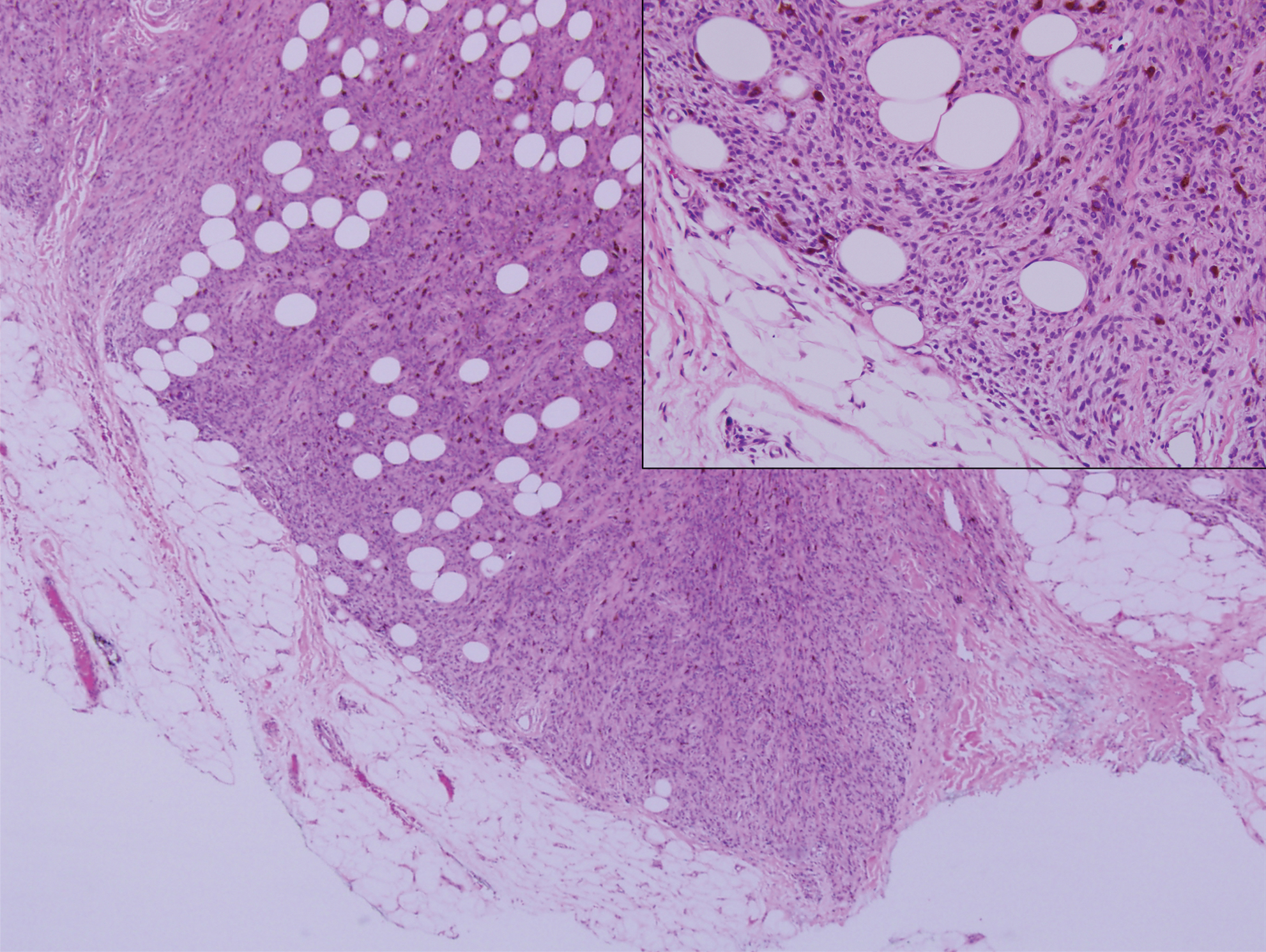

Desmoplastic nevus (DN) is a benign melanocytic neoplasm characterized by predominantly spindle-shaped nevus cells embedded within a fibrotic stroma. Although it can resemble a Spitz nevus, it is recognized as a distinct entity.15-17 Clinically, DN presents as a small and flesh-colored, erythematous or slightly pigmented papule or nodule that usually occurs on the arms and legs of young adults. Histopathologically, DN demonstrates a dermal-based proliferation of spindled melanocytes embedded in a dense collagenous stroma with sparse or absent melanin deposition. The collagen bundles often show artifactual clefts and onion skin-like accentuation around vessels. Melanocytes may be epithelioid (Figure 2).16 Immunohistochemically, DN expresses melanocytic markers such as S-100, Melan-A, and human melanoma black 45, but epithelial membrane antigen is negative. Human melanoma black 45 demonstrates maturation with stronger staining in superficial portions of the lesion and diminution of staining with increasing dermal depth.18 Many other melanocytic tumors share histologic similarities to DN including blue nevus and desmoplastic melanoma.17,19,20

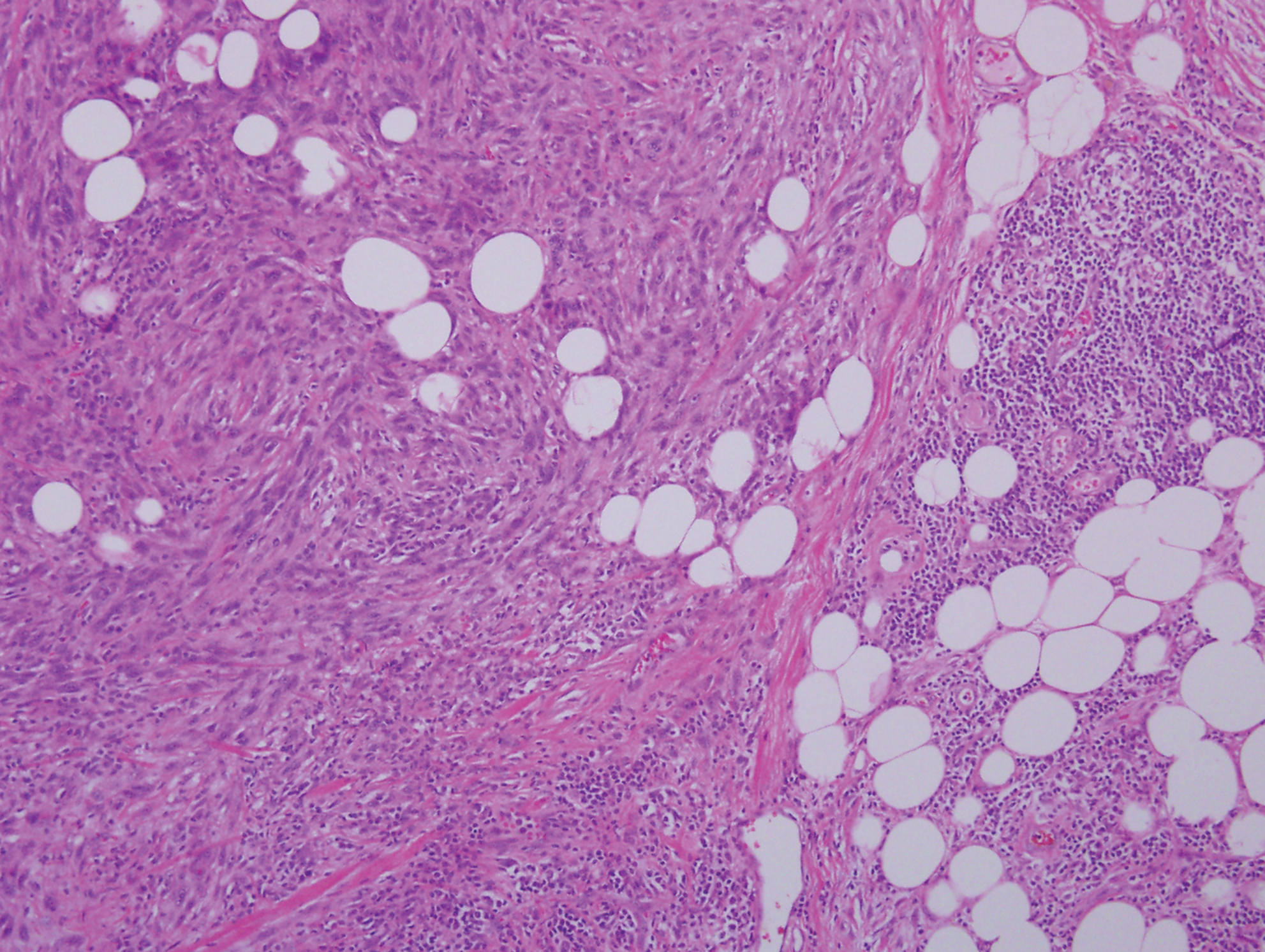

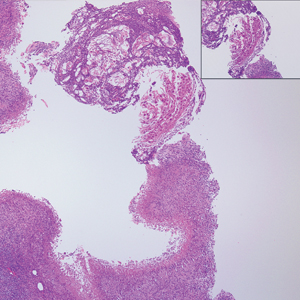

Palisaded encapsulated neuroma, also referred to as solitary circumscribed neuroma, was first described by Reed et al21 in 1972. It is a benign and solitary, firm, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papule that occurs in middle-aged adults, predominately near mucocutaneous junctions of the face. Other locations include the oral mucosa, eyelid, nasal fossa, shoulder, arm, hand, foot, and glans penis.22,23 Histopathologically, palisaded encapsulated neuroma demonstrates a solitary, well-circumscribed, partially encapsulated, intradermal nodule composed of interweaving fascicles of spindle cells with prominent clefts (Figure 3). Rarely, palisaded encapsulated neuroma may have a plexiform or multinodular architecture.24 Immunohistochemically, tumor cells stain positively for S-100 protein, type IV collagen, and vimentin. The capsule, composed of perineural cells, stains positive for epithelial membrane antigen. A neurofilament stain will highlight axons within the tumor.24,25 Currently, palisaded encapsulated neuroma does not have a well-established link to known neurocutaneous or inherited syndromes. Excision is curative with a low risk of recurrence.26

Sclerotic fibromas (SFs) were first reported by Weary et al27 as multiple tumors involving the tongues of patients with Cowden syndrome. Sporadic or solitary SFs of the skin in patients without Cowden syndrome have been reported, and both multiple and solitary SFs present with similar pathologic changes.28-30 Clinically, the solitary variant manifests as a well-demarcated, flesh-colored to erythematous, waxy papule or nodule with no site or sex predilection.30,31 Histologically, SF demonstrates a well-demarcated, nonencapsulated dermal nodule composed of hypocellular and sclerotic collagen bundles with scattered spindled cells and prominent clefts resembling Vincent van Gogh's Starry Night or plywood (Figure 4). Immunohistochemically, the spindled cells strongly express CD34. Factor XIIIa and markers of melanocytic, neural, and muscular differentiation are negative. When rendering a diagnosis in a patient with multiple SFs, a comment regarding the possibility of Cowden syndrome should be mentioned.32

- Fetsch JF, Miettinen M. Sclerosing perineurioma: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases of a distinctive soft tissue lesion with a predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1433-1442.

- Fox MD, Gleason BC, Thomas AB, et al. Extra-acral cutaneous/soft tissue sclerosing perineurioma: an under-recognized entity in the differential of CD34-positive cutaneous neoplasms. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1053-1056.

- Erstine EM, Ko JS, Rubin BP, et al. Broadening the anatomic landscape of sclerosing perineurioma: a series of 5 cases in nonacral sites. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:679-681.

- Senghore N, Cunliffe D, Watt-Smith S, et al. Extraneural perineurioma of the face: an unusual cutaneous presentation of an uncommon tumour. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;39:315-319.

- Lazarus SS, Trombetta LD. Ultrastructural identification of a benign perineurial cell tumor. Cancer. 1978;41:1823-1829.

- Macarenco RS, Cury-Martins J. Extra-acral cutaneous sclerosing perineurioma with CD34 fingerprint pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:388-392.

- Santos-Briz A, Godoy E, Canueto J, et al. Cutaneous intraneural perineurioma: a case report. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:E45-E48.

- Rubin AI, Yassaee M, Johnson W, et al. Multiple cutaneous sclerosing perineuriomas: an extensive presentation with involvement of the bilateral upper extremities. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36(suppl 1):60-65.

- Damman J, Biswas A. Fibrous papule: a histopathologic review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:551-560.

- Macri A, Tanner LS. Cutaneous angiofibroma. StatPearls. https://www.statpearls.com/kb/viewarticle/17566/. Updated January 24, 2019. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- Darling TN, Skarulis MC, Steinberg SM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas and collagenomas in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:853-857.

- Schaffer JV, Gohara MA, McNiff JM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas: a cutaneous manifestation of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:S108-S111.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Bansal C, Stewart D, Li A, et al. Histologic variants of fibrous papule. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:424-428.

- Harris GR, Shea CR, Horenstein MG, et al. Desmoplastic (sclerotic) nevus: an underrecognized entity that resembles dermatofibroma and desmoplastic melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:786-794.

- Ferrara G, Brasiello M, Annese P, et al. Desmoplastic nevus: clinicopathologic keynotes. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:718-722.

- Sherrill AM, Crespo G, Prakash AV, et al. Desmoplastic nevus: an entity distinct from Spitz nevus and blue nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:35-39.

- Kucher C, Zhang PJ, Pasha T, et al. Expression of Melan-A and Ki-67 in desmoplastic melanoma and desmoplastic nevi. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:452-457.

- Sidiropoulos M, Sholl LM, Obregon R, et al. Desmoplastic nevus of chronically sun-damaged skin: an entity to be distinguished from desmoplastic melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:629-634.

- Kiuru M, Patel RM, Busam KJ. Desmoplastic melanocytic nevi with lymphocytic aggregates. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:940-944.

- Reed RJ, Fine RM, Meltzer HD. Palisaded, encapsulated neuromas of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:865-870.

- Newman MD, Milgraum S. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma (PEN): an often misdiagnosed neural tumor. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Beutler B, Cohen PR. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma of the trunk: a case report and review of palisaded encapsulated neuroma. Cureus. 2016;8:E726.

- Jokinen CH, Ragsdale BD, Argenyi ZB. Expanding the clinicopathologic spectrum of palisaded encapsulated neuroma. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:43-48.

- Argenyi ZB. Immunohistochemical characterization of palisaded, encapsulated neuroma. J Cutan Pathol. 1990;17:329-335.

- Batra J, Ramesh V, Molpariya A, et al. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma: an unusual presentation. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:262-264.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry WC Jr, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden's disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

- Mahmood MN, Salama ME, Chaffins M, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of skin: a possible link with pleomorphic fibroma with immunophenotypic expression for O13 (CD99) and CD34. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:631-636.

- Nakashima K, Yamada N, Adachi K, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: morphological characterization of the 'plywood-like pattern'. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):74-79.

- Rapini RP, Golitz LE. Sclerotic fibromas of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:266-271.

- Abbas O, Ghosn S, Bahhady R, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma on the scalp of a young girl: reactive sclerosis pattern? J Dermatol. 2010;37:575-577.

- Hanft VN, Shea CR, McNutt NS, et al. Expression of CD34 in sclerotic ("plywood") fibromas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:17-21.

The Diagnosis: Sclerosing Perineurioma

Sclerosing perineurioma, first described in 1997 by Fetsch and Miettinen,1 is a subtype of perineurioma with a strong predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Rare cases involving extra-acral sites including the forearm, elbow, axilla, back, neck, lower leg, thigh, knee, lips, nose, and mouth have been reported.2-4 Perineurioma is a relatively uncommon and benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor with exclusive perineurial differentiation.5 Perineurioma is divided into intraneural and extraneural types; the latter are further subclassified into soft tissue, sclerosing, reticular, and plexiform types. Other rare forms include the sclerosing, Pacinian corpuscle-like perineurioma, lipomatous perineurioma, perineurioma with xanthomatous areas, and perineurioma with granular cells.6,7

Clinically, sclerosing perineurioma usually presents as a solitary lesion; however, rare cases of multiple lesions have been reported.8 Our patient presented with a solitary papule on the nose. Histopathologically, sclerosing perineurioma demonstrates slender spindle cells in a whorled growth pattern (onion skin) embedded in a hyalinized, lamellar, and dense collagenous stroma with intervening cleftlike spaces. Immunohistochemically, the spindle cells of our case stained positive for epithelial membrane antigen (quiz images). Other positive immunostains for perineurioma include claudin-1 and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1). Perineurioma lacks expression of S-100 but can express CD34.2 As a benign tumor, the prognosis of sclerosing perineurioma is excellent. Complete local excision is considered curative.1

Angiofibroma, also known as fibrous papule, is a common and benign lesion located primarily on or in close proximity to the nose.9 Angiofibromas can be associated with genodermatoses such as tuberous sclerosis, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, or Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. When angiofibromas involve the penis, they are called pearly penile papules. Ungual angiofibroma, also known as Koenen tumor, occurs underneath the nail.10-12 Both facial angiofibromas (>3) and ungual angiofibromas (>2) are independent major criteria for tuberous sclerosis.13 Clinically, angiofibroma presents as a small, dome-shaped, pink papule arising on the lower portion of the nose or nearby area of the central face. Histopathologically, angiofibromas classically demonstrate increased dilated vessels and fibrosis in the dermis. Stellate, plump, spindle-shaped, and multinucleated cells can be seen in the collagenous stroma. The collagen fibers around hair follicles are arranged concentrically, resulting in an onion skin-like appearance. The epidermal rete ridges can be effaced (Figure 1). Increased numbers of single-unit melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction can be seen in some cases. Immunohistochemically, a variable number of spindled and multinucleated cells in the dermis stain with factor XIIIa. There are at least 7 histologic variants of angiofibroma including hypercellular, pigmented, inflammatory, pleomorphic, clear cell, granular cell, and epithelioid.9,14

Desmoplastic nevus (DN) is a benign melanocytic neoplasm characterized by predominantly spindle-shaped nevus cells embedded within a fibrotic stroma. Although it can resemble a Spitz nevus, it is recognized as a distinct entity.15-17 Clinically, DN presents as a small and flesh-colored, erythematous or slightly pigmented papule or nodule that usually occurs on the arms and legs of young adults. Histopathologically, DN demonstrates a dermal-based proliferation of spindled melanocytes embedded in a dense collagenous stroma with sparse or absent melanin deposition. The collagen bundles often show artifactual clefts and onion skin-like accentuation around vessels. Melanocytes may be epithelioid (Figure 2).16 Immunohistochemically, DN expresses melanocytic markers such as S-100, Melan-A, and human melanoma black 45, but epithelial membrane antigen is negative. Human melanoma black 45 demonstrates maturation with stronger staining in superficial portions of the lesion and diminution of staining with increasing dermal depth.18 Many other melanocytic tumors share histologic similarities to DN including blue nevus and desmoplastic melanoma.17,19,20

Palisaded encapsulated neuroma, also referred to as solitary circumscribed neuroma, was first described by Reed et al21 in 1972. It is a benign and solitary, firm, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papule that occurs in middle-aged adults, predominately near mucocutaneous junctions of the face. Other locations include the oral mucosa, eyelid, nasal fossa, shoulder, arm, hand, foot, and glans penis.22,23 Histopathologically, palisaded encapsulated neuroma demonstrates a solitary, well-circumscribed, partially encapsulated, intradermal nodule composed of interweaving fascicles of spindle cells with prominent clefts (Figure 3). Rarely, palisaded encapsulated neuroma may have a plexiform or multinodular architecture.24 Immunohistochemically, tumor cells stain positively for S-100 protein, type IV collagen, and vimentin. The capsule, composed of perineural cells, stains positive for epithelial membrane antigen. A neurofilament stain will highlight axons within the tumor.24,25 Currently, palisaded encapsulated neuroma does not have a well-established link to known neurocutaneous or inherited syndromes. Excision is curative with a low risk of recurrence.26

Sclerotic fibromas (SFs) were first reported by Weary et al27 as multiple tumors involving the tongues of patients with Cowden syndrome. Sporadic or solitary SFs of the skin in patients without Cowden syndrome have been reported, and both multiple and solitary SFs present with similar pathologic changes.28-30 Clinically, the solitary variant manifests as a well-demarcated, flesh-colored to erythematous, waxy papule or nodule with no site or sex predilection.30,31 Histologically, SF demonstrates a well-demarcated, nonencapsulated dermal nodule composed of hypocellular and sclerotic collagen bundles with scattered spindled cells and prominent clefts resembling Vincent van Gogh's Starry Night or plywood (Figure 4). Immunohistochemically, the spindled cells strongly express CD34. Factor XIIIa and markers of melanocytic, neural, and muscular differentiation are negative. When rendering a diagnosis in a patient with multiple SFs, a comment regarding the possibility of Cowden syndrome should be mentioned.32

The Diagnosis: Sclerosing Perineurioma

Sclerosing perineurioma, first described in 1997 by Fetsch and Miettinen,1 is a subtype of perineurioma with a strong predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Rare cases involving extra-acral sites including the forearm, elbow, axilla, back, neck, lower leg, thigh, knee, lips, nose, and mouth have been reported.2-4 Perineurioma is a relatively uncommon and benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor with exclusive perineurial differentiation.5 Perineurioma is divided into intraneural and extraneural types; the latter are further subclassified into soft tissue, sclerosing, reticular, and plexiform types. Other rare forms include the sclerosing, Pacinian corpuscle-like perineurioma, lipomatous perineurioma, perineurioma with xanthomatous areas, and perineurioma with granular cells.6,7

Clinically, sclerosing perineurioma usually presents as a solitary lesion; however, rare cases of multiple lesions have been reported.8 Our patient presented with a solitary papule on the nose. Histopathologically, sclerosing perineurioma demonstrates slender spindle cells in a whorled growth pattern (onion skin) embedded in a hyalinized, lamellar, and dense collagenous stroma with intervening cleftlike spaces. Immunohistochemically, the spindle cells of our case stained positive for epithelial membrane antigen (quiz images). Other positive immunostains for perineurioma include claudin-1 and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1). Perineurioma lacks expression of S-100 but can express CD34.2 As a benign tumor, the prognosis of sclerosing perineurioma is excellent. Complete local excision is considered curative.1

Angiofibroma, also known as fibrous papule, is a common and benign lesion located primarily on or in close proximity to the nose.9 Angiofibromas can be associated with genodermatoses such as tuberous sclerosis, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, or Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. When angiofibromas involve the penis, they are called pearly penile papules. Ungual angiofibroma, also known as Koenen tumor, occurs underneath the nail.10-12 Both facial angiofibromas (>3) and ungual angiofibromas (>2) are independent major criteria for tuberous sclerosis.13 Clinically, angiofibroma presents as a small, dome-shaped, pink papule arising on the lower portion of the nose or nearby area of the central face. Histopathologically, angiofibromas classically demonstrate increased dilated vessels and fibrosis in the dermis. Stellate, plump, spindle-shaped, and multinucleated cells can be seen in the collagenous stroma. The collagen fibers around hair follicles are arranged concentrically, resulting in an onion skin-like appearance. The epidermal rete ridges can be effaced (Figure 1). Increased numbers of single-unit melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction can be seen in some cases. Immunohistochemically, a variable number of spindled and multinucleated cells in the dermis stain with factor XIIIa. There are at least 7 histologic variants of angiofibroma including hypercellular, pigmented, inflammatory, pleomorphic, clear cell, granular cell, and epithelioid.9,14

Desmoplastic nevus (DN) is a benign melanocytic neoplasm characterized by predominantly spindle-shaped nevus cells embedded within a fibrotic stroma. Although it can resemble a Spitz nevus, it is recognized as a distinct entity.15-17 Clinically, DN presents as a small and flesh-colored, erythematous or slightly pigmented papule or nodule that usually occurs on the arms and legs of young adults. Histopathologically, DN demonstrates a dermal-based proliferation of spindled melanocytes embedded in a dense collagenous stroma with sparse or absent melanin deposition. The collagen bundles often show artifactual clefts and onion skin-like accentuation around vessels. Melanocytes may be epithelioid (Figure 2).16 Immunohistochemically, DN expresses melanocytic markers such as S-100, Melan-A, and human melanoma black 45, but epithelial membrane antigen is negative. Human melanoma black 45 demonstrates maturation with stronger staining in superficial portions of the lesion and diminution of staining with increasing dermal depth.18 Many other melanocytic tumors share histologic similarities to DN including blue nevus and desmoplastic melanoma.17,19,20

Palisaded encapsulated neuroma, also referred to as solitary circumscribed neuroma, was first described by Reed et al21 in 1972. It is a benign and solitary, firm, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papule that occurs in middle-aged adults, predominately near mucocutaneous junctions of the face. Other locations include the oral mucosa, eyelid, nasal fossa, shoulder, arm, hand, foot, and glans penis.22,23 Histopathologically, palisaded encapsulated neuroma demonstrates a solitary, well-circumscribed, partially encapsulated, intradermal nodule composed of interweaving fascicles of spindle cells with prominent clefts (Figure 3). Rarely, palisaded encapsulated neuroma may have a plexiform or multinodular architecture.24 Immunohistochemically, tumor cells stain positively for S-100 protein, type IV collagen, and vimentin. The capsule, composed of perineural cells, stains positive for epithelial membrane antigen. A neurofilament stain will highlight axons within the tumor.24,25 Currently, palisaded encapsulated neuroma does not have a well-established link to known neurocutaneous or inherited syndromes. Excision is curative with a low risk of recurrence.26

Sclerotic fibromas (SFs) were first reported by Weary et al27 as multiple tumors involving the tongues of patients with Cowden syndrome. Sporadic or solitary SFs of the skin in patients without Cowden syndrome have been reported, and both multiple and solitary SFs present with similar pathologic changes.28-30 Clinically, the solitary variant manifests as a well-demarcated, flesh-colored to erythematous, waxy papule or nodule with no site or sex predilection.30,31 Histologically, SF demonstrates a well-demarcated, nonencapsulated dermal nodule composed of hypocellular and sclerotic collagen bundles with scattered spindled cells and prominent clefts resembling Vincent van Gogh's Starry Night or plywood (Figure 4). Immunohistochemically, the spindled cells strongly express CD34. Factor XIIIa and markers of melanocytic, neural, and muscular differentiation are negative. When rendering a diagnosis in a patient with multiple SFs, a comment regarding the possibility of Cowden syndrome should be mentioned.32

- Fetsch JF, Miettinen M. Sclerosing perineurioma: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases of a distinctive soft tissue lesion with a predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1433-1442.

- Fox MD, Gleason BC, Thomas AB, et al. Extra-acral cutaneous/soft tissue sclerosing perineurioma: an under-recognized entity in the differential of CD34-positive cutaneous neoplasms. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1053-1056.

- Erstine EM, Ko JS, Rubin BP, et al. Broadening the anatomic landscape of sclerosing perineurioma: a series of 5 cases in nonacral sites. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:679-681.

- Senghore N, Cunliffe D, Watt-Smith S, et al. Extraneural perineurioma of the face: an unusual cutaneous presentation of an uncommon tumour. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;39:315-319.

- Lazarus SS, Trombetta LD. Ultrastructural identification of a benign perineurial cell tumor. Cancer. 1978;41:1823-1829.

- Macarenco RS, Cury-Martins J. Extra-acral cutaneous sclerosing perineurioma with CD34 fingerprint pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:388-392.

- Santos-Briz A, Godoy E, Canueto J, et al. Cutaneous intraneural perineurioma: a case report. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:E45-E48.

- Rubin AI, Yassaee M, Johnson W, et al. Multiple cutaneous sclerosing perineuriomas: an extensive presentation with involvement of the bilateral upper extremities. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36(suppl 1):60-65.

- Damman J, Biswas A. Fibrous papule: a histopathologic review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:551-560.

- Macri A, Tanner LS. Cutaneous angiofibroma. StatPearls. https://www.statpearls.com/kb/viewarticle/17566/. Updated January 24, 2019. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- Darling TN, Skarulis MC, Steinberg SM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas and collagenomas in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:853-857.

- Schaffer JV, Gohara MA, McNiff JM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas: a cutaneous manifestation of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:S108-S111.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Bansal C, Stewart D, Li A, et al. Histologic variants of fibrous papule. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:424-428.

- Harris GR, Shea CR, Horenstein MG, et al. Desmoplastic (sclerotic) nevus: an underrecognized entity that resembles dermatofibroma and desmoplastic melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:786-794.

- Ferrara G, Brasiello M, Annese P, et al. Desmoplastic nevus: clinicopathologic keynotes. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:718-722.

- Sherrill AM, Crespo G, Prakash AV, et al. Desmoplastic nevus: an entity distinct from Spitz nevus and blue nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:35-39.

- Kucher C, Zhang PJ, Pasha T, et al. Expression of Melan-A and Ki-67 in desmoplastic melanoma and desmoplastic nevi. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:452-457.

- Sidiropoulos M, Sholl LM, Obregon R, et al. Desmoplastic nevus of chronically sun-damaged skin: an entity to be distinguished from desmoplastic melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:629-634.

- Kiuru M, Patel RM, Busam KJ. Desmoplastic melanocytic nevi with lymphocytic aggregates. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:940-944.

- Reed RJ, Fine RM, Meltzer HD. Palisaded, encapsulated neuromas of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:865-870.

- Newman MD, Milgraum S. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma (PEN): an often misdiagnosed neural tumor. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Beutler B, Cohen PR. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma of the trunk: a case report and review of palisaded encapsulated neuroma. Cureus. 2016;8:E726.

- Jokinen CH, Ragsdale BD, Argenyi ZB. Expanding the clinicopathologic spectrum of palisaded encapsulated neuroma. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:43-48.

- Argenyi ZB. Immunohistochemical characterization of palisaded, encapsulated neuroma. J Cutan Pathol. 1990;17:329-335.

- Batra J, Ramesh V, Molpariya A, et al. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma: an unusual presentation. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:262-264.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry WC Jr, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden's disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

- Mahmood MN, Salama ME, Chaffins M, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of skin: a possible link with pleomorphic fibroma with immunophenotypic expression for O13 (CD99) and CD34. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:631-636.

- Nakashima K, Yamada N, Adachi K, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: morphological characterization of the 'plywood-like pattern'. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):74-79.

- Rapini RP, Golitz LE. Sclerotic fibromas of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:266-271.

- Abbas O, Ghosn S, Bahhady R, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma on the scalp of a young girl: reactive sclerosis pattern? J Dermatol. 2010;37:575-577.

- Hanft VN, Shea CR, McNutt NS, et al. Expression of CD34 in sclerotic ("plywood") fibromas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:17-21.

- Fetsch JF, Miettinen M. Sclerosing perineurioma: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases of a distinctive soft tissue lesion with a predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1433-1442.

- Fox MD, Gleason BC, Thomas AB, et al. Extra-acral cutaneous/soft tissue sclerosing perineurioma: an under-recognized entity in the differential of CD34-positive cutaneous neoplasms. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1053-1056.

- Erstine EM, Ko JS, Rubin BP, et al. Broadening the anatomic landscape of sclerosing perineurioma: a series of 5 cases in nonacral sites. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:679-681.

- Senghore N, Cunliffe D, Watt-Smith S, et al. Extraneural perineurioma of the face: an unusual cutaneous presentation of an uncommon tumour. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;39:315-319.

- Lazarus SS, Trombetta LD. Ultrastructural identification of a benign perineurial cell tumor. Cancer. 1978;41:1823-1829.

- Macarenco RS, Cury-Martins J. Extra-acral cutaneous sclerosing perineurioma with CD34 fingerprint pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:388-392.

- Santos-Briz A, Godoy E, Canueto J, et al. Cutaneous intraneural perineurioma: a case report. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:E45-E48.

- Rubin AI, Yassaee M, Johnson W, et al. Multiple cutaneous sclerosing perineuriomas: an extensive presentation with involvement of the bilateral upper extremities. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36(suppl 1):60-65.

- Damman J, Biswas A. Fibrous papule: a histopathologic review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:551-560.

- Macri A, Tanner LS. Cutaneous angiofibroma. StatPearls. https://www.statpearls.com/kb/viewarticle/17566/. Updated January 24, 2019. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- Darling TN, Skarulis MC, Steinberg SM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas and collagenomas in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:853-857.

- Schaffer JV, Gohara MA, McNiff JM, et al. Multiple facial angiofibromas: a cutaneous manifestation of Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:S108-S111.

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254.

- Bansal C, Stewart D, Li A, et al. Histologic variants of fibrous papule. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:424-428.

- Harris GR, Shea CR, Horenstein MG, et al. Desmoplastic (sclerotic) nevus: an underrecognized entity that resembles dermatofibroma and desmoplastic melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:786-794.

- Ferrara G, Brasiello M, Annese P, et al. Desmoplastic nevus: clinicopathologic keynotes. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:718-722.

- Sherrill AM, Crespo G, Prakash AV, et al. Desmoplastic nevus: an entity distinct from Spitz nevus and blue nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:35-39.

- Kucher C, Zhang PJ, Pasha T, et al. Expression of Melan-A and Ki-67 in desmoplastic melanoma and desmoplastic nevi. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:452-457.

- Sidiropoulos M, Sholl LM, Obregon R, et al. Desmoplastic nevus of chronically sun-damaged skin: an entity to be distinguished from desmoplastic melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:629-634.

- Kiuru M, Patel RM, Busam KJ. Desmoplastic melanocytic nevi with lymphocytic aggregates. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:940-944.

- Reed RJ, Fine RM, Meltzer HD. Palisaded, encapsulated neuromas of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:865-870.

- Newman MD, Milgraum S. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma (PEN): an often misdiagnosed neural tumor. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12.

- Beutler B, Cohen PR. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma of the trunk: a case report and review of palisaded encapsulated neuroma. Cureus. 2016;8:E726.

- Jokinen CH, Ragsdale BD, Argenyi ZB. Expanding the clinicopathologic spectrum of palisaded encapsulated neuroma. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:43-48.

- Argenyi ZB. Immunohistochemical characterization of palisaded, encapsulated neuroma. J Cutan Pathol. 1990;17:329-335.

- Batra J, Ramesh V, Molpariya A, et al. Palisaded encapsulated neuroma: an unusual presentation. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:262-264.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry WC Jr, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden's disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

- Mahmood MN, Salama ME, Chaffins M, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of skin: a possible link with pleomorphic fibroma with immunophenotypic expression for O13 (CD99) and CD34. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:631-636.

- Nakashima K, Yamada N, Adachi K, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: morphological characterization of the 'plywood-like pattern'. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):74-79.

- Rapini RP, Golitz LE. Sclerotic fibromas of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:266-271.

- Abbas O, Ghosn S, Bahhady R, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma on the scalp of a young girl: reactive sclerosis pattern? J Dermatol. 2010;37:575-577.

- Hanft VN, Shea CR, McNutt NS, et al. Expression of CD34 in sclerotic ("plywood") fibromas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:17-21.

A 25-year-old man presented with a flesh-colored papule on the left side of the nose of 2 years' duration.

Systemic Epstein-Barr Virus–Positive T-cell Lymphoma of Childhood

Case Report

A 7-year-old Chinese boy presented with multiple painful oral and tongue ulcers of 2 weeks’ duration as well as acute onset of moderate to high fever (highest temperature, 39.3°C) for 5 days. The fever was reported to have run a relapsing course, accompanied by rigors but without convulsions or cognitive changes. At times, the patient had nasal congestion, nasal discharge, and cough. He also had a transient eruption on the back and hands as well as an indurated red nodule on the left forearm.

Before the patient was hospitalized, antibiotic therapy was administered by other physicians, but the condition of fever and oral ulcers did not improve. After the patient was hospitalized, new tender nodules emerged on the scalp, buttocks, and lower extremities. New ulcers also appeared on the palate.

History

Two months earlier, the patient had presented with a painful perioral skin ulcer that resolved after being treated as contagious eczema. Another dermatologist previously had considered a diagnosis of hand-foot-and-mouth disease.

The patient was born by normal spontaneous vaginal delivery, without abnormality. He was breastfed; feeding, growth, and the developmental history showed no abnormality. He was the family’s eldest child, with a healthy brother and sister. There was no history of familial illness. He received bacillus Calmette-Guérin and poliomyelitis vaccines after birth; the rest of the vaccine history was unclear. There was no history of immunologic abnormality.

Physical Examination

A 1.5×1.5-cm, warm, red nodule with a central black crust was noted on the left forearm (Figure 1A). Several similar lesions were noted on the buttocks, scalp, and lower extremities. Multiple ulcers, as large as 1 cm, were present on the tongue, palate, and left angle of the mouth (Figure 1B). The pharynx was congested, and the tonsils were mildly enlarged. Multiple enlarged, movable, nontender lymph nodes could be palpated in the cervical basins, axillae, and groin. No purpura or ecchymosis was detected.

Laboratory Results

Laboratory testing revealed a normal total white blood cell count (4.26×109/L [reference range, 4.0–12.0×109/L]), with normal neutrophils (1.36×109/L [reference range, 1.32–7.90×109/L]), lymphocytes (2.77×109/L [reference range, 1.20–6.00×109/L]), and monocytes (0.13×109/L [reference range, 0.08–0.80×109/L]); a mildly decreased hemoglobin level (115 g/L [reference range, 120–160 g/L]); a normal platelet count (102×109/L [reference range, 100–380×109/L]); an elevated lactate dehydrogenase level (614 U/L [reference range, 110–330 U/L]); an elevated α-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase level (483 U/L [reference range, 120–270 U/L]); elevated prothrombin time (15.3 s [reference range, 9–14 s]); elevated activated partial thromboplastin time (59.8 s [reference range, 20.6–39.6 s]); and an elevated D-dimer level (1.51 mg/L [reference range, <0.73 mg/L]). In addition, autoantibody testing revealed a positive antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 and a strong positive anti–Ro-52 level.

The peripheral blood lymphocyte classification demonstrated a prominent elevated percentage of T lymphocytes, with predominantly CD8+ cells (CD3, 94.87%; CD8, 71.57%; CD4, 24.98%; CD4:CD8 ratio, 0.35) and a diminished percentage of B lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cells. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) antibody testing was positive for anti–viral capsid antigen (VCA) IgG and negative for anti-VCA IgM.

Smears of the ulcer on the tongue demonstrated gram-positive cocci, gram-negative bacilli, and diplococci. Culture of sputum showed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Inspection for acid-fast bacilli in sputum yielded negative results 3 times. A purified protein derivative skin test for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection was negative.

Imaging and Other Studies

Computed tomography of the chest and abdomen demonstrated 2 nodular opacities on the lower right lung; spotted opacities on the upper right lung; floccular opacities on the rest area of the lung; mild pleural effusion; enlargement of lymph nodes on the mediastinum, the bilateral hilum of the lung, and mesentery; and hepatosplenomegaly. Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia. Nasal cavity endoscopy showed sinusitis. Fundus examination showed vasculopathy of the left retina. A colonoscopy showed normal mucosa.

Histopathology

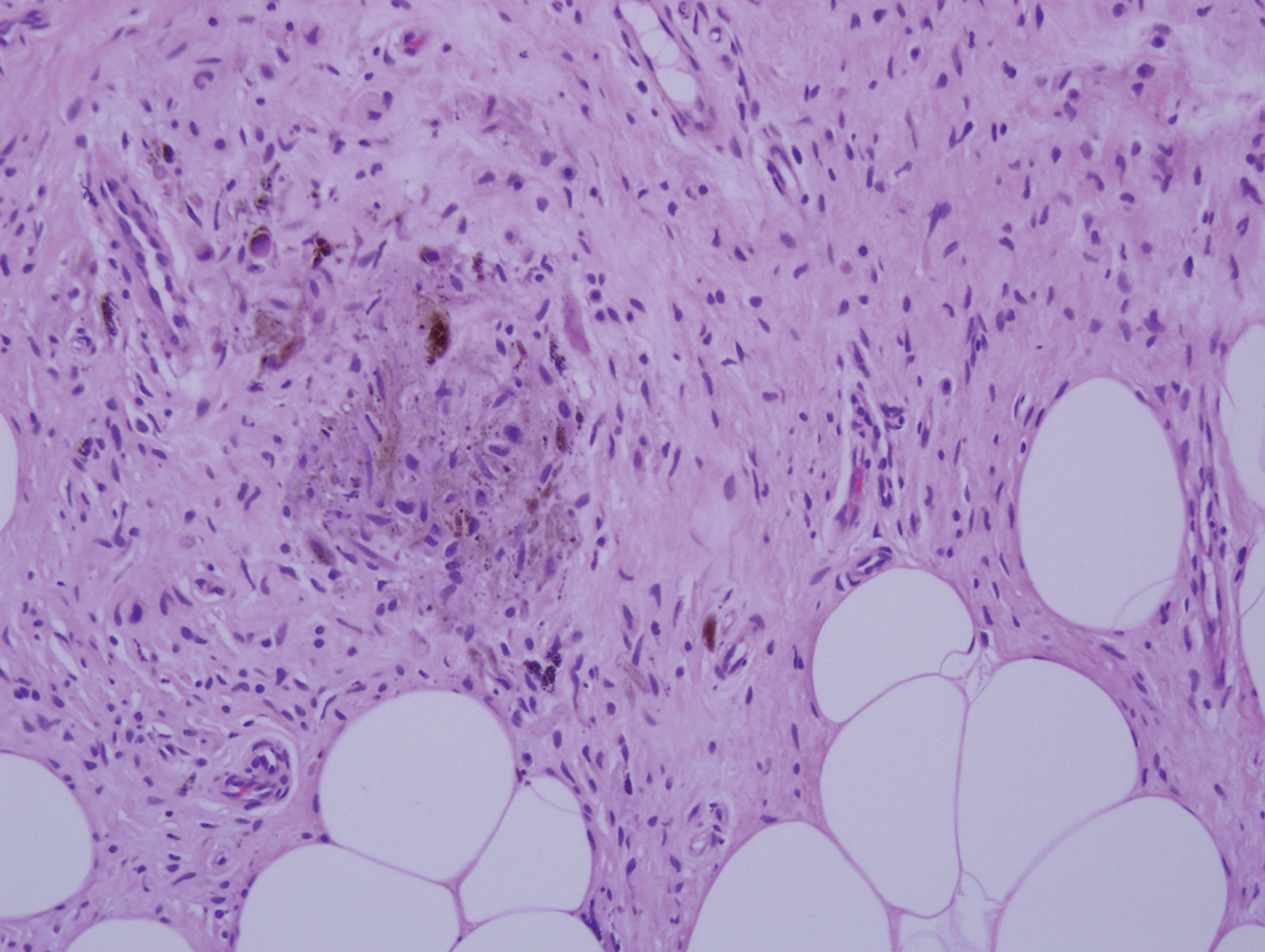

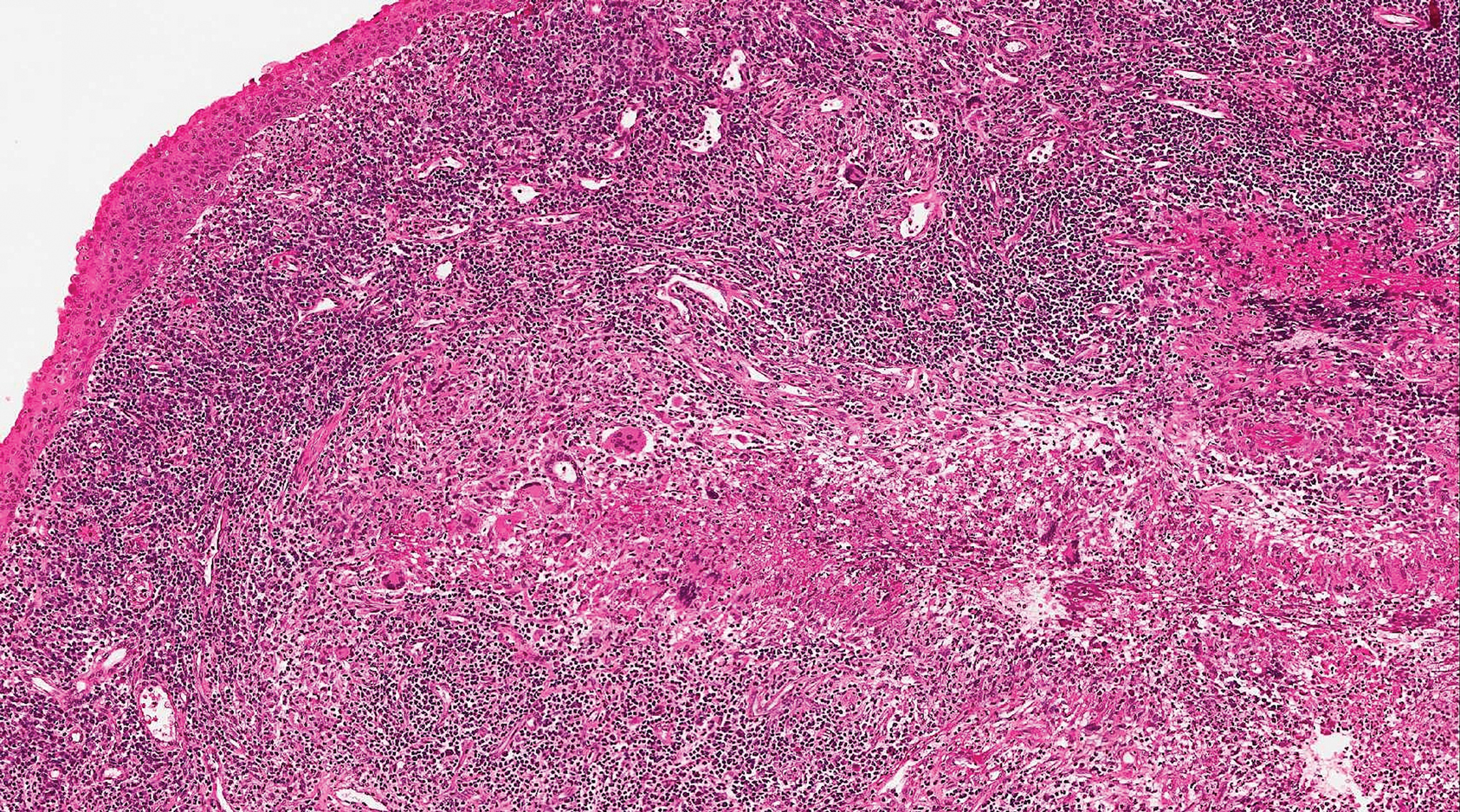

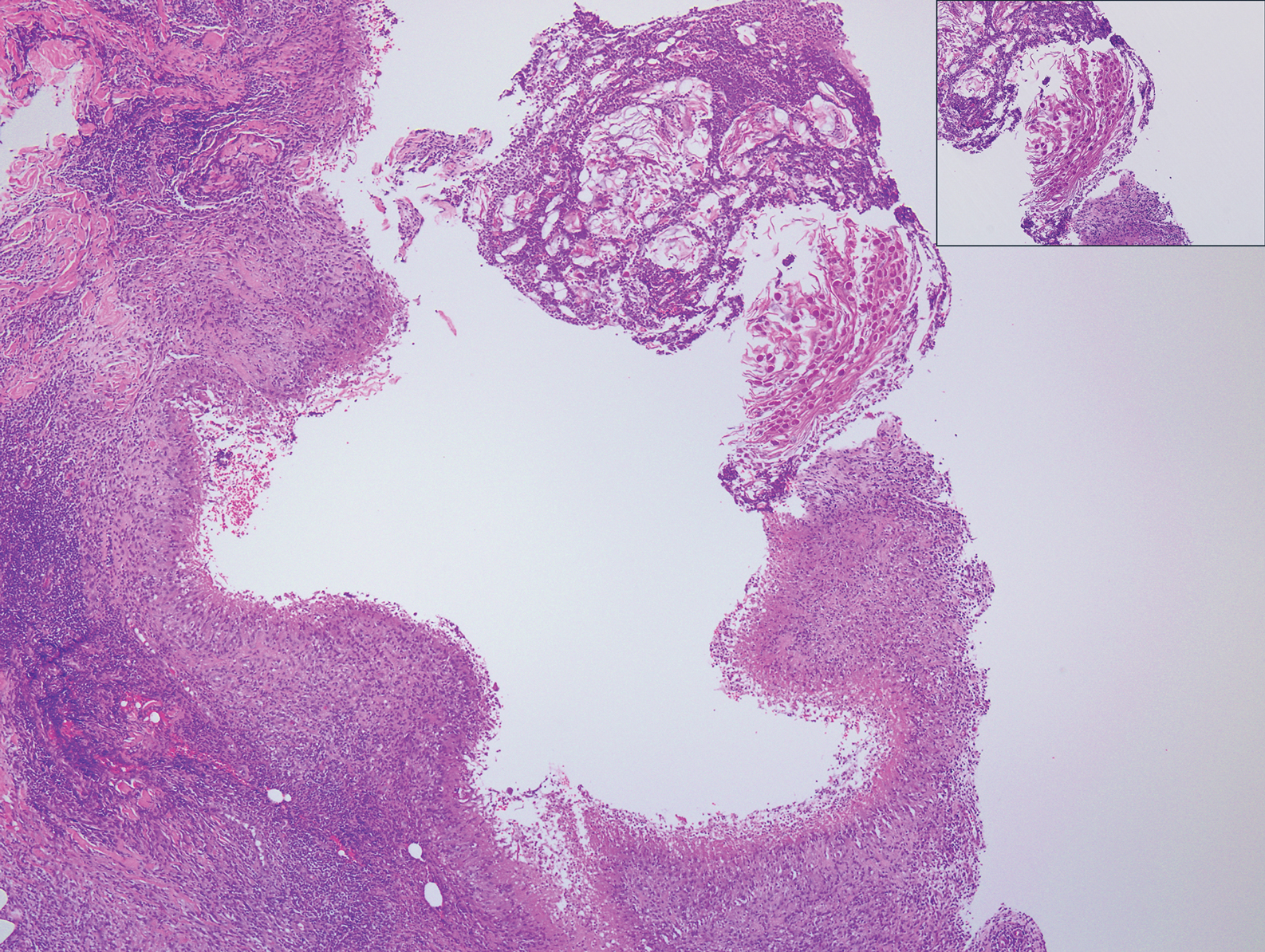

Biopsy of the nodule on the left arm showed dense, superficial to deep perivascular, periadnexal, perineural, and panniculitislike lymphoid infiltrates, as well as a sparse interstitial infiltrate with irregular and pleomorphic medium to large nuclei. Lymphoid cells showed mild epidermotropism, with tagging to the basal layer. Some vessel walls were infiltrated by similar cells (Figure 2). Infiltrative atypical lymphoid cells expressed CD3 and CD7 and were mostly CD8+, with a few CD4+ cells and most cells negative for CD5, CD20, CD30, CD56, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase. Cytotoxic markers granzyme B and T-cell intracellular antigen protein 1 were scattered positive. Immunostaining for Ki-67 protein highlighted an increased proliferative rate of 80% in malignant cells. In situ hybridization for EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) demonstrated EBV-positive atypical lymphoid cells (Figure 3). Analysis for T-cell receptor (TCR) γ gene rearrangement revealed a monoclonal pattern. Bone marrow aspirate showed proliferation of the 3 cell lines. The percentage of T lymphocytes was increased (20% of all nucleated cells). No hemophagocytic activity was found.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma was made. Before the final diagnosis was made, the patient was treated by rheumatologists with antibiotics, antiviral drugs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and other symptomatic treatments. Following antibiotic therapy, a sputum culture reverted to normal flora, the coagulation index (ie, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time) returned to normal, and the D-dimer level decreased to 1.19 mg/L.

The patient’s parents refused to accept chemotherapy for him. Instead, they chose herbal therapy only; 5 months later, they reported that all of his symptoms had resolved; however, the disease suddenly relapsed after another 7 months, with multiple skin nodules and fever. The patient died, even with chemotherapy in another hospital.

Comment

Prevalence and Presentation

Epstein-Barr virus is a ubiquitous γ-herpesvirus with tropism for B cells, affecting more than 90% of the adult population worldwide. In addition to infecting B cells, EBV is capable of infecting T and NK cells, leading to various EBV-related lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs). The frequency and clinical presentation of infection varies based on the type of EBV-infected cells and the state of host immunity.1-3

Primary infection usually is asymptomatic and occurs early in life; when symptomatic, the disease usually presents as infectious mononucleosis (IM), characterized by polyclonal expansion of infected B cells and subsequent cytotoxic T-cell response. A diagnosis of EBV infection can be made by testing for specific IgM and IgG antibodies against VCA, early antigens, and EBV nuclear antigen proteins.3,4

Associated LPDs

Although most symptoms associated with IM resolve within weeks or months, persistent or recurrent IM-like symptoms or even lasting disease occasionally occur, particularly in children and young adults. This complication is known as chronic active EBV infection (CAEBV), frequently associated with EBV-infected T-cell or NK-cell proliferation, especially in East Asian populations.3,5

Epstein-Barr virus–positive T-cell and NK-cell LPDs of childhood include CAEBV infection of T-cell and NK-cell types and systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood. The former includes hydroa vacciniforme–like LPD and severe mosquito bite allergy.3

Systemic EBV-Positive T-cell Lymphoma of Childhood

This entity occurs not only in children but also in adolescents and young adults. A fulminant illness characterized by clonal proliferation of EBV-infected cytotoxic T cells, it can develop shortly after primary EBV infection or is linked to CAEBV infection. The disorder is rare and has a racial predilection for Asian (ie, Japanese, Chinese, Korean) populations and indigenous populations of Mexico and Central and South America.6-8

Complications

Systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is often complicated by hemophagocytic syndrome, coagulopathy, sepsis, and multiorgan failure. Other signs and symptoms include high fever, rash, jaundice, diarrhea, pancytopenia, and hepatosplenomegaly. The liver, spleen, lymph nodes, and bone marrow are commonly involved, and the disease can involve skin, the heart, and the lungs.9,10

Diagnosis

When systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma occurs shortly after IM, serology shows low or absent anti-VCA IgM and positive anti-VCA IgG. Infiltrating T cells usually are small and lack cytologic atypia; however, cases with pleomorphic, medium to large lymphoid cells, irregular nuclei, and frequent mitoses have been described. Hemophagocytosis can be seen in the liver, spleen, and bone marrow.3,11

The most typical phenotype of systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma is CD2+CD3+CD8+CD20−CD56−, with expression of the cytotoxic granules known as T-cell intracellular antigen 1 and granzyme B. Rare cases of CD4+ and mixed CD4+/CD8+ phenotypes have been described, usually in the setting of CAEBV infection.3,12 Neoplastic cells have monoclonally rearranged TCR-γ genes and consistent EBER positivity with in situ hybridization.13 A final diagnosis is based on a comprehensive analysis of clinical, morphological, immunohistochemical, and molecular biological aspects.

Clinical Course and Prognosis

Most patients with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma have an aggressive clinical course with high mortality. In a few cases, patients were reported to respond to a regimen of etoposide and dexamethasone, followed by allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.3

In recognition of the aggressive clinical behavior and desire to clearly distinguish systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma from CAEBV infection, the older term systemic EBV-positive T-cell LPD of childhood, which had been introduced in 2008 to the World Health Organization classification, was changed to systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood in the revised 2016 World Health Organization classification.6,12 However, Kim et al14 reported a case with excellent response to corticosteroid administration, suggesting that systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood may be more heterogeneous in terms of prognosis.

Our patient presented with acute IM-like symptoms, including high fever, tonsillar enlargement, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly, as well as uncommon oral ulcers and skin lesions, including indurated nodules. Histopathologic changes in the skin nodule, proliferation in bone marrow, immunohistochemical phenotype, and positivity of EBER and TCR-γ monoclonal rearrangement were all consistent with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood. The patient was positive for VCA IgG and negative for VCA IgM, compatible with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood occurring shortly after IM. Neither pancytopenia, hemophagocytic syndrome, nor multiorgan failure occurred during the course.

Differential Diagnosis

It is important to distinguish IM from systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood and CAEBV infection. Detection of anti–VCA IgM in the early stage, its disappearance during the clinical course, and appearance of anti-EBV–determined nuclear antigen is useful to distinguish IM from the neoplasms, as systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is negative for anti-EBV–determined nuclear antigen. Carefully following the clinical course also is important.3,15

Epstein-Barr virus–associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis can occur in association with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood and might represent a continuum of disease rather than distinct entities.14 The most useful marker for differentiating EBV-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is an abnormal karyotype rather than molecular clonality.16

Outcome

Mortality risk in EBV-associated T-cell and NK-cell LPD is not primarily dependent on whether the lesion has progressed to lymphoma but instead is related to associated complications.17

Conclusion

Although systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is a rare disorder and has race predilection, dermatologists should be aware due to the aggressive clinical source and poor prognosis. Histopathology and in situ hybridization for EBER and TCR gene rearrangements are critical for final diagnosis. Although rare cases can show temporary resolution, the final outcome of this disease is not optimistic.

- Ameli F, Ghafourian F, Masir N. Systematic Epstein-Barr virus-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disease presenting as a persistent fever and cough: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:288.

- Kim HJ, Ko YH, Kim JE, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lympho-proliferative disorders: review and update on 2016 WHO classification. J Pathol Transl Med. 2017;51:352-358.

- Dojcinov SD, Fend F, Quintanilla-Martinez L. EBV-positive lymphoproliferations of B- T- and NK-cell derivation in non-immunocompromised hosts [published online March 7, 2018]. Pathogens. doi:10.3390/pathogens7010028.

- Luzuriaga K, Sullivan JL. Infectious mononucleosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1993-2000.

- Cohen JI, Kimura H, Nakamura S, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disease in non-immunocompromised hosts: a status report and summary of an international meeting, 8-9 September 2008. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1472-1482.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375-2390.

- Kim WY, Montes-Mojarro IA, Fend F, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated T and NK-cell lymphoproliferative diseases. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:71.

- Hong M, Ko YH, Yoo KH, et al. EBV-positive T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative disease of childhood. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:137-147.

- Quintanilla-Martinez L, Kumar S, Fend F, et al. Fulminant EBV(+) T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder following acute/chronic EBV infection: a distinct clinicopathologic syndrome. Blood. 2000;96:443-451.

- Chen G, Chen L, Qin X, et al. Systemic Epstein-Barr virus positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disease of childhood with hemophagocytic syndrome. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:7110-7113.

- Grywalska E, Rolinski J. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphomas. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:291-303.

- Huang W, Lv N, Ying J, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of four cases of EBV positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders of childhood in China. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:4991-4999.

- Tabanelli V, Agostinelli C, Sabattini E, et al. Systemic Epstein-Barr-virus-positive T cell lymphoproliferative childhood disease in a 22-year-old Caucasian man: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:218.

- Kim DH, Kim M, Kim Y, et al. Systemic Epstein-Barr virus-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disease of childhood with good response to steroid therapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017;39:e497-e500.

- Arai A, Yamaguchi T, Komatsu H, et al. Infectious mononucleosis accompanied by clonal proliferation of EBV-infected cells and infection of CD8-positive cells. Int J Hematol. 2014;99:671-675.

- Smith MC, Cohen DN, Greig B, et al. The ambiguous boundary between EBV-related hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and systemic EBV-driven T cell lymphoproliferative disorder. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5738-5749.

- Paik JH, Choe JY, Kim H, et al. Clinicopathological categorization of Epstein-Barr virus-positive T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative disease: an analysis of 42 cases with an emphasis on prognostic implications. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58:53-63.

Case Report

A 7-year-old Chinese boy presented with multiple painful oral and tongue ulcers of 2 weeks’ duration as well as acute onset of moderate to high fever (highest temperature, 39.3°C) for 5 days. The fever was reported to have run a relapsing course, accompanied by rigors but without convulsions or cognitive changes. At times, the patient had nasal congestion, nasal discharge, and cough. He also had a transient eruption on the back and hands as well as an indurated red nodule on the left forearm.

Before the patient was hospitalized, antibiotic therapy was administered by other physicians, but the condition of fever and oral ulcers did not improve. After the patient was hospitalized, new tender nodules emerged on the scalp, buttocks, and lower extremities. New ulcers also appeared on the palate.

History

Two months earlier, the patient had presented with a painful perioral skin ulcer that resolved after being treated as contagious eczema. Another dermatologist previously had considered a diagnosis of hand-foot-and-mouth disease.

The patient was born by normal spontaneous vaginal delivery, without abnormality. He was breastfed; feeding, growth, and the developmental history showed no abnormality. He was the family’s eldest child, with a healthy brother and sister. There was no history of familial illness. He received bacillus Calmette-Guérin and poliomyelitis vaccines after birth; the rest of the vaccine history was unclear. There was no history of immunologic abnormality.

Physical Examination

A 1.5×1.5-cm, warm, red nodule with a central black crust was noted on the left forearm (Figure 1A). Several similar lesions were noted on the buttocks, scalp, and lower extremities. Multiple ulcers, as large as 1 cm, were present on the tongue, palate, and left angle of the mouth (Figure 1B). The pharynx was congested, and the tonsils were mildly enlarged. Multiple enlarged, movable, nontender lymph nodes could be palpated in the cervical basins, axillae, and groin. No purpura or ecchymosis was detected.

Laboratory Results

Laboratory testing revealed a normal total white blood cell count (4.26×109/L [reference range, 4.0–12.0×109/L]), with normal neutrophils (1.36×109/L [reference range, 1.32–7.90×109/L]), lymphocytes (2.77×109/L [reference range, 1.20–6.00×109/L]), and monocytes (0.13×109/L [reference range, 0.08–0.80×109/L]); a mildly decreased hemoglobin level (115 g/L [reference range, 120–160 g/L]); a normal platelet count (102×109/L [reference range, 100–380×109/L]); an elevated lactate dehydrogenase level (614 U/L [reference range, 110–330 U/L]); an elevated α-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase level (483 U/L [reference range, 120–270 U/L]); elevated prothrombin time (15.3 s [reference range, 9–14 s]); elevated activated partial thromboplastin time (59.8 s [reference range, 20.6–39.6 s]); and an elevated D-dimer level (1.51 mg/L [reference range, <0.73 mg/L]). In addition, autoantibody testing revealed a positive antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 and a strong positive anti–Ro-52 level.

The peripheral blood lymphocyte classification demonstrated a prominent elevated percentage of T lymphocytes, with predominantly CD8+ cells (CD3, 94.87%; CD8, 71.57%; CD4, 24.98%; CD4:CD8 ratio, 0.35) and a diminished percentage of B lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cells. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) antibody testing was positive for anti–viral capsid antigen (VCA) IgG and negative for anti-VCA IgM.

Smears of the ulcer on the tongue demonstrated gram-positive cocci, gram-negative bacilli, and diplococci. Culture of sputum showed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Inspection for acid-fast bacilli in sputum yielded negative results 3 times. A purified protein derivative skin test for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection was negative.

Imaging and Other Studies

Computed tomography of the chest and abdomen demonstrated 2 nodular opacities on the lower right lung; spotted opacities on the upper right lung; floccular opacities on the rest area of the lung; mild pleural effusion; enlargement of lymph nodes on the mediastinum, the bilateral hilum of the lung, and mesentery; and hepatosplenomegaly. Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia. Nasal cavity endoscopy showed sinusitis. Fundus examination showed vasculopathy of the left retina. A colonoscopy showed normal mucosa.

Histopathology

Biopsy of the nodule on the left arm showed dense, superficial to deep perivascular, periadnexal, perineural, and panniculitislike lymphoid infiltrates, as well as a sparse interstitial infiltrate with irregular and pleomorphic medium to large nuclei. Lymphoid cells showed mild epidermotropism, with tagging to the basal layer. Some vessel walls were infiltrated by similar cells (Figure 2). Infiltrative atypical lymphoid cells expressed CD3 and CD7 and were mostly CD8+, with a few CD4+ cells and most cells negative for CD5, CD20, CD30, CD56, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase. Cytotoxic markers granzyme B and T-cell intracellular antigen protein 1 were scattered positive. Immunostaining for Ki-67 protein highlighted an increased proliferative rate of 80% in malignant cells. In situ hybridization for EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) demonstrated EBV-positive atypical lymphoid cells (Figure 3). Analysis for T-cell receptor (TCR) γ gene rearrangement revealed a monoclonal pattern. Bone marrow aspirate showed proliferation of the 3 cell lines. The percentage of T lymphocytes was increased (20% of all nucleated cells). No hemophagocytic activity was found.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma was made. Before the final diagnosis was made, the patient was treated by rheumatologists with antibiotics, antiviral drugs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and other symptomatic treatments. Following antibiotic therapy, a sputum culture reverted to normal flora, the coagulation index (ie, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time) returned to normal, and the D-dimer level decreased to 1.19 mg/L.

The patient’s parents refused to accept chemotherapy for him. Instead, they chose herbal therapy only; 5 months later, they reported that all of his symptoms had resolved; however, the disease suddenly relapsed after another 7 months, with multiple skin nodules and fever. The patient died, even with chemotherapy in another hospital.

Comment

Prevalence and Presentation

Epstein-Barr virus is a ubiquitous γ-herpesvirus with tropism for B cells, affecting more than 90% of the adult population worldwide. In addition to infecting B cells, EBV is capable of infecting T and NK cells, leading to various EBV-related lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs). The frequency and clinical presentation of infection varies based on the type of EBV-infected cells and the state of host immunity.1-3

Primary infection usually is asymptomatic and occurs early in life; when symptomatic, the disease usually presents as infectious mononucleosis (IM), characterized by polyclonal expansion of infected B cells and subsequent cytotoxic T-cell response. A diagnosis of EBV infection can be made by testing for specific IgM and IgG antibodies against VCA, early antigens, and EBV nuclear antigen proteins.3,4

Associated LPDs

Although most symptoms associated with IM resolve within weeks or months, persistent or recurrent IM-like symptoms or even lasting disease occasionally occur, particularly in children and young adults. This complication is known as chronic active EBV infection (CAEBV), frequently associated with EBV-infected T-cell or NK-cell proliferation, especially in East Asian populations.3,5

Epstein-Barr virus–positive T-cell and NK-cell LPDs of childhood include CAEBV infection of T-cell and NK-cell types and systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood. The former includes hydroa vacciniforme–like LPD and severe mosquito bite allergy.3

Systemic EBV-Positive T-cell Lymphoma of Childhood

This entity occurs not only in children but also in adolescents and young adults. A fulminant illness characterized by clonal proliferation of EBV-infected cytotoxic T cells, it can develop shortly after primary EBV infection or is linked to CAEBV infection. The disorder is rare and has a racial predilection for Asian (ie, Japanese, Chinese, Korean) populations and indigenous populations of Mexico and Central and South America.6-8

Complications

Systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is often complicated by hemophagocytic syndrome, coagulopathy, sepsis, and multiorgan failure. Other signs and symptoms include high fever, rash, jaundice, diarrhea, pancytopenia, and hepatosplenomegaly. The liver, spleen, lymph nodes, and bone marrow are commonly involved, and the disease can involve skin, the heart, and the lungs.9,10

Diagnosis

When systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma occurs shortly after IM, serology shows low or absent anti-VCA IgM and positive anti-VCA IgG. Infiltrating T cells usually are small and lack cytologic atypia; however, cases with pleomorphic, medium to large lymphoid cells, irregular nuclei, and frequent mitoses have been described. Hemophagocytosis can be seen in the liver, spleen, and bone marrow.3,11

The most typical phenotype of systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma is CD2+CD3+CD8+CD20−CD56−, with expression of the cytotoxic granules known as T-cell intracellular antigen 1 and granzyme B. Rare cases of CD4+ and mixed CD4+/CD8+ phenotypes have been described, usually in the setting of CAEBV infection.3,12 Neoplastic cells have monoclonally rearranged TCR-γ genes and consistent EBER positivity with in situ hybridization.13 A final diagnosis is based on a comprehensive analysis of clinical, morphological, immunohistochemical, and molecular biological aspects.

Clinical Course and Prognosis

Most patients with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma have an aggressive clinical course with high mortality. In a few cases, patients were reported to respond to a regimen of etoposide and dexamethasone, followed by allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.3

In recognition of the aggressive clinical behavior and desire to clearly distinguish systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma from CAEBV infection, the older term systemic EBV-positive T-cell LPD of childhood, which had been introduced in 2008 to the World Health Organization classification, was changed to systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood in the revised 2016 World Health Organization classification.6,12 However, Kim et al14 reported a case with excellent response to corticosteroid administration, suggesting that systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood may be more heterogeneous in terms of prognosis.

Our patient presented with acute IM-like symptoms, including high fever, tonsillar enlargement, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly, as well as uncommon oral ulcers and skin lesions, including indurated nodules. Histopathologic changes in the skin nodule, proliferation in bone marrow, immunohistochemical phenotype, and positivity of EBER and TCR-γ monoclonal rearrangement were all consistent with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood. The patient was positive for VCA IgG and negative for VCA IgM, compatible with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood occurring shortly after IM. Neither pancytopenia, hemophagocytic syndrome, nor multiorgan failure occurred during the course.

Differential Diagnosis

It is important to distinguish IM from systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood and CAEBV infection. Detection of anti–VCA IgM in the early stage, its disappearance during the clinical course, and appearance of anti-EBV–determined nuclear antigen is useful to distinguish IM from the neoplasms, as systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is negative for anti-EBV–determined nuclear antigen. Carefully following the clinical course also is important.3,15

Epstein-Barr virus–associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis can occur in association with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood and might represent a continuum of disease rather than distinct entities.14 The most useful marker for differentiating EBV-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is an abnormal karyotype rather than molecular clonality.16

Outcome

Mortality risk in EBV-associated T-cell and NK-cell LPD is not primarily dependent on whether the lesion has progressed to lymphoma but instead is related to associated complications.17

Conclusion

Although systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is a rare disorder and has race predilection, dermatologists should be aware due to the aggressive clinical source and poor prognosis. Histopathology and in situ hybridization for EBER and TCR gene rearrangements are critical for final diagnosis. Although rare cases can show temporary resolution, the final outcome of this disease is not optimistic.

Case Report

A 7-year-old Chinese boy presented with multiple painful oral and tongue ulcers of 2 weeks’ duration as well as acute onset of moderate to high fever (highest temperature, 39.3°C) for 5 days. The fever was reported to have run a relapsing course, accompanied by rigors but without convulsions or cognitive changes. At times, the patient had nasal congestion, nasal discharge, and cough. He also had a transient eruption on the back and hands as well as an indurated red nodule on the left forearm.

Before the patient was hospitalized, antibiotic therapy was administered by other physicians, but the condition of fever and oral ulcers did not improve. After the patient was hospitalized, new tender nodules emerged on the scalp, buttocks, and lower extremities. New ulcers also appeared on the palate.

History

Two months earlier, the patient had presented with a painful perioral skin ulcer that resolved after being treated as contagious eczema. Another dermatologist previously had considered a diagnosis of hand-foot-and-mouth disease.

The patient was born by normal spontaneous vaginal delivery, without abnormality. He was breastfed; feeding, growth, and the developmental history showed no abnormality. He was the family’s eldest child, with a healthy brother and sister. There was no history of familial illness. He received bacillus Calmette-Guérin and poliomyelitis vaccines after birth; the rest of the vaccine history was unclear. There was no history of immunologic abnormality.

Physical Examination

A 1.5×1.5-cm, warm, red nodule with a central black crust was noted on the left forearm (Figure 1A). Several similar lesions were noted on the buttocks, scalp, and lower extremities. Multiple ulcers, as large as 1 cm, were present on the tongue, palate, and left angle of the mouth (Figure 1B). The pharynx was congested, and the tonsils were mildly enlarged. Multiple enlarged, movable, nontender lymph nodes could be palpated in the cervical basins, axillae, and groin. No purpura or ecchymosis was detected.

Laboratory Results

Laboratory testing revealed a normal total white blood cell count (4.26×109/L [reference range, 4.0–12.0×109/L]), with normal neutrophils (1.36×109/L [reference range, 1.32–7.90×109/L]), lymphocytes (2.77×109/L [reference range, 1.20–6.00×109/L]), and monocytes (0.13×109/L [reference range, 0.08–0.80×109/L]); a mildly decreased hemoglobin level (115 g/L [reference range, 120–160 g/L]); a normal platelet count (102×109/L [reference range, 100–380×109/L]); an elevated lactate dehydrogenase level (614 U/L [reference range, 110–330 U/L]); an elevated α-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase level (483 U/L [reference range, 120–270 U/L]); elevated prothrombin time (15.3 s [reference range, 9–14 s]); elevated activated partial thromboplastin time (59.8 s [reference range, 20.6–39.6 s]); and an elevated D-dimer level (1.51 mg/L [reference range, <0.73 mg/L]). In addition, autoantibody testing revealed a positive antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 and a strong positive anti–Ro-52 level.

The peripheral blood lymphocyte classification demonstrated a prominent elevated percentage of T lymphocytes, with predominantly CD8+ cells (CD3, 94.87%; CD8, 71.57%; CD4, 24.98%; CD4:CD8 ratio, 0.35) and a diminished percentage of B lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cells. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) antibody testing was positive for anti–viral capsid antigen (VCA) IgG and negative for anti-VCA IgM.

Smears of the ulcer on the tongue demonstrated gram-positive cocci, gram-negative bacilli, and diplococci. Culture of sputum showed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Inspection for acid-fast bacilli in sputum yielded negative results 3 times. A purified protein derivative skin test for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection was negative.

Imaging and Other Studies

Computed tomography of the chest and abdomen demonstrated 2 nodular opacities on the lower right lung; spotted opacities on the upper right lung; floccular opacities on the rest area of the lung; mild pleural effusion; enlargement of lymph nodes on the mediastinum, the bilateral hilum of the lung, and mesentery; and hepatosplenomegaly. Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia. Nasal cavity endoscopy showed sinusitis. Fundus examination showed vasculopathy of the left retina. A colonoscopy showed normal mucosa.

Histopathology

Biopsy of the nodule on the left arm showed dense, superficial to deep perivascular, periadnexal, perineural, and panniculitislike lymphoid infiltrates, as well as a sparse interstitial infiltrate with irregular and pleomorphic medium to large nuclei. Lymphoid cells showed mild epidermotropism, with tagging to the basal layer. Some vessel walls were infiltrated by similar cells (Figure 2). Infiltrative atypical lymphoid cells expressed CD3 and CD7 and were mostly CD8+, with a few CD4+ cells and most cells negative for CD5, CD20, CD30, CD56, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase. Cytotoxic markers granzyme B and T-cell intracellular antigen protein 1 were scattered positive. Immunostaining for Ki-67 protein highlighted an increased proliferative rate of 80% in malignant cells. In situ hybridization for EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) demonstrated EBV-positive atypical lymphoid cells (Figure 3). Analysis for T-cell receptor (TCR) γ gene rearrangement revealed a monoclonal pattern. Bone marrow aspirate showed proliferation of the 3 cell lines. The percentage of T lymphocytes was increased (20% of all nucleated cells). No hemophagocytic activity was found.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma was made. Before the final diagnosis was made, the patient was treated by rheumatologists with antibiotics, antiviral drugs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and other symptomatic treatments. Following antibiotic therapy, a sputum culture reverted to normal flora, the coagulation index (ie, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time) returned to normal, and the D-dimer level decreased to 1.19 mg/L.

The patient’s parents refused to accept chemotherapy for him. Instead, they chose herbal therapy only; 5 months later, they reported that all of his symptoms had resolved; however, the disease suddenly relapsed after another 7 months, with multiple skin nodules and fever. The patient died, even with chemotherapy in another hospital.

Comment

Prevalence and Presentation

Epstein-Barr virus is a ubiquitous γ-herpesvirus with tropism for B cells, affecting more than 90% of the adult population worldwide. In addition to infecting B cells, EBV is capable of infecting T and NK cells, leading to various EBV-related lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs). The frequency and clinical presentation of infection varies based on the type of EBV-infected cells and the state of host immunity.1-3

Primary infection usually is asymptomatic and occurs early in life; when symptomatic, the disease usually presents as infectious mononucleosis (IM), characterized by polyclonal expansion of infected B cells and subsequent cytotoxic T-cell response. A diagnosis of EBV infection can be made by testing for specific IgM and IgG antibodies against VCA, early antigens, and EBV nuclear antigen proteins.3,4

Associated LPDs

Although most symptoms associated with IM resolve within weeks or months, persistent or recurrent IM-like symptoms or even lasting disease occasionally occur, particularly in children and young adults. This complication is known as chronic active EBV infection (CAEBV), frequently associated with EBV-infected T-cell or NK-cell proliferation, especially in East Asian populations.3,5

Epstein-Barr virus–positive T-cell and NK-cell LPDs of childhood include CAEBV infection of T-cell and NK-cell types and systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood. The former includes hydroa vacciniforme–like LPD and severe mosquito bite allergy.3

Systemic EBV-Positive T-cell Lymphoma of Childhood

This entity occurs not only in children but also in adolescents and young adults. A fulminant illness characterized by clonal proliferation of EBV-infected cytotoxic T cells, it can develop shortly after primary EBV infection or is linked to CAEBV infection. The disorder is rare and has a racial predilection for Asian (ie, Japanese, Chinese, Korean) populations and indigenous populations of Mexico and Central and South America.6-8

Complications

Systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is often complicated by hemophagocytic syndrome, coagulopathy, sepsis, and multiorgan failure. Other signs and symptoms include high fever, rash, jaundice, diarrhea, pancytopenia, and hepatosplenomegaly. The liver, spleen, lymph nodes, and bone marrow are commonly involved, and the disease can involve skin, the heart, and the lungs.9,10

Diagnosis

When systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma occurs shortly after IM, serology shows low or absent anti-VCA IgM and positive anti-VCA IgG. Infiltrating T cells usually are small and lack cytologic atypia; however, cases with pleomorphic, medium to large lymphoid cells, irregular nuclei, and frequent mitoses have been described. Hemophagocytosis can be seen in the liver, spleen, and bone marrow.3,11

The most typical phenotype of systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma is CD2+CD3+CD8+CD20−CD56−, with expression of the cytotoxic granules known as T-cell intracellular antigen 1 and granzyme B. Rare cases of CD4+ and mixed CD4+/CD8+ phenotypes have been described, usually in the setting of CAEBV infection.3,12 Neoplastic cells have monoclonally rearranged TCR-γ genes and consistent EBER positivity with in situ hybridization.13 A final diagnosis is based on a comprehensive analysis of clinical, morphological, immunohistochemical, and molecular biological aspects.

Clinical Course and Prognosis

Most patients with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma have an aggressive clinical course with high mortality. In a few cases, patients were reported to respond to a regimen of etoposide and dexamethasone, followed by allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.3

In recognition of the aggressive clinical behavior and desire to clearly distinguish systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma from CAEBV infection, the older term systemic EBV-positive T-cell LPD of childhood, which had been introduced in 2008 to the World Health Organization classification, was changed to systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood in the revised 2016 World Health Organization classification.6,12 However, Kim et al14 reported a case with excellent response to corticosteroid administration, suggesting that systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood may be more heterogeneous in terms of prognosis.

Our patient presented with acute IM-like symptoms, including high fever, tonsillar enlargement, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly, as well as uncommon oral ulcers and skin lesions, including indurated nodules. Histopathologic changes in the skin nodule, proliferation in bone marrow, immunohistochemical phenotype, and positivity of EBER and TCR-γ monoclonal rearrangement were all consistent with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood. The patient was positive for VCA IgG and negative for VCA IgM, compatible with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood occurring shortly after IM. Neither pancytopenia, hemophagocytic syndrome, nor multiorgan failure occurred during the course.

Differential Diagnosis

It is important to distinguish IM from systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood and CAEBV infection. Detection of anti–VCA IgM in the early stage, its disappearance during the clinical course, and appearance of anti-EBV–determined nuclear antigen is useful to distinguish IM from the neoplasms, as systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is negative for anti-EBV–determined nuclear antigen. Carefully following the clinical course also is important.3,15

Epstein-Barr virus–associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis can occur in association with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood and might represent a continuum of disease rather than distinct entities.14 The most useful marker for differentiating EBV-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is an abnormal karyotype rather than molecular clonality.16

Outcome

Mortality risk in EBV-associated T-cell and NK-cell LPD is not primarily dependent on whether the lesion has progressed to lymphoma but instead is related to associated complications.17

Conclusion

Although systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is a rare disorder and has race predilection, dermatologists should be aware due to the aggressive clinical source and poor prognosis. Histopathology and in situ hybridization for EBER and TCR gene rearrangements are critical for final diagnosis. Although rare cases can show temporary resolution, the final outcome of this disease is not optimistic.

- Ameli F, Ghafourian F, Masir N. Systematic Epstein-Barr virus-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disease presenting as a persistent fever and cough: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:288.

- Kim HJ, Ko YH, Kim JE, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lympho-proliferative disorders: review and update on 2016 WHO classification. J Pathol Transl Med. 2017;51:352-358.

- Dojcinov SD, Fend F, Quintanilla-Martinez L. EBV-positive lymphoproliferations of B- T- and NK-cell derivation in non-immunocompromised hosts [published online March 7, 2018]. Pathogens. doi:10.3390/pathogens7010028.

- Luzuriaga K, Sullivan JL. Infectious mononucleosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1993-2000.

- Cohen JI, Kimura H, Nakamura S, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disease in non-immunocompromised hosts: a status report and summary of an international meeting, 8-9 September 2008. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1472-1482.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375-2390.

- Kim WY, Montes-Mojarro IA, Fend F, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated T and NK-cell lymphoproliferative diseases. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:71.

- Hong M, Ko YH, Yoo KH, et al. EBV-positive T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative disease of childhood. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:137-147.

- Quintanilla-Martinez L, Kumar S, Fend F, et al. Fulminant EBV(+) T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder following acute/chronic EBV infection: a distinct clinicopathologic syndrome. Blood. 2000;96:443-451.

- Chen G, Chen L, Qin X, et al. Systemic Epstein-Barr virus positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disease of childhood with hemophagocytic syndrome. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:7110-7113.

- Grywalska E, Rolinski J. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphomas. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:291-303.