User login

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is widely used in the economically developed world to treat a variety of hematologic malignancies as well as nonmalignant diseases and solid tumors. An estimated 17,900 HSCTs were performed in 2011, and survival rates continue to increase.1 Pulmonary complications post HSCT are common, with rates ranging from 40% to 60%, and are associated with increased morbidity and mortality.2

Clinical diagnosis of pulmonary complications in the HSCT population has been aided by a previously well-defined chronology of the most common diseases.3 Historically, early pulmonary complications were defined as pulmonary complications occurring within 100 days of HSCT (corresponding to the acute graft-versus-host disease [GVHD] period). Late pulmonary complications are those that occur thereafter. This timeline, however, is now more variable given the increasing indications for HSCT, the use of reduced-intensity conditioning strategies, and varied individual immune reconstitution. This article discusses the management of early post-HSCT pulmonary complications; late post-HSCT pulmonary complications will be discussed in a separate follow-up article.

Transplant Basics

The development of pulmonary complications is affected by many factors associated with the transplant. Autologous transplantation involves the collection of a patient’s own stem cells, appropriate storage and processing, and re-implantation after induction therapy. During induction therapy, the patient undergoes high-dose chemotherapy or radiation therapy that ablates the bone marrow. The stem cells are then transfused back into the patient to repopulate the bone marrow. Allogeneic transplants involve the collection of stem cells from a donor. Donors are matched as closely as possible to the recipient’s histocompatibility antigen (HLA) haplotypes to prevent graft failure and rejection. The donor can be related or unrelated to the recipient. If there is not a possibility of a related match (from a sibling), then a national search is undertaken to look for a match through the National Marrow Donor Program. There are fewer transplant reactions and occurrences of GVHD if the major HLAs of the donor and recipient match. Table 1 reviews basic definitions pertaining to HSCT.

How the cells for transplantation are obtained is also an important factor in the rate of complications. There are 3 main sources: peripheral blood, bone marrow, and umbilical cord. Peripheral stem cell harvesting involves exposing the donor to granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (gCSF), which increases peripheral circulation of stem cells. These cells are then collected and infused into the recipient after the recipient has completed an induction regimen involving chemotherapy and/or radiation, depending on the protocol. This procedure is called peripheral blood stem cell transplant (PBSCT). Stem cells can also be directly harvested from bone marrow cells, which are collected from repeated aspiration of bone marrow from the posterior iliac crest.4 This technique is most common in children, whereas in adults peripheral blood stem cells are the most common source. Overall mortality does not differ based on the source of the stem cells. It is postulated that GVHD may be more common in patients undergoing PBSCT, but the graft failure rate may be lower.5

The third option is umbilical cord blood (UCB) as the source of stem cells. This involves the collection of umbilical cord blood that is prepared and frozen after birth. It has a smaller volume of cells, and although fewer cells are needed when using UCB, 2 separate donors may be required for a single adult recipient. The engraftment of the stem cells is slower and infections in the post-transplant period are more common. Prior reports indicate GVHD rates may be lower.4 While the use of UCB is not common in adults, the incidence has doubled over the past decade, increasing from 3% to 6%.

The conditioning regimen can influence pulmonary complications. Traditionally, an ablative transplant involves high-dose chemotherapy or radiation to eradicate the recipient’s bone marrow. This regimen can lead to many complications, especially in the immediate post-transplant period. In the past 10 years, there has been increasing interest in non-myeloablative, or reduced-intensity, conditioning transplants.6 These “mini transplants” involve smaller doses of chemotherapy or radiation, which do not totally eradicate the bone marrow; after the transplant a degree of chimerism develops where the donor and recipient stem cells coexist. The medications in the preparative regimen also should be considered because they can affect pulmonary complications after transplant. Certain chemotherapeutic agents such as carmustine, bleomycin, and many others can lead to acute and chronic presentations of pulmonary diseases such as hypersensitivity pneumonitis, pulmonary fibrosis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and abnormal pulmonary function testing.

After the HSCT, GVHD can develop in more than 50% of allogeneic recipients.3 The incidence of GVHD has been reported to be increasing over the past 12 years.It is divided into acute GVHD (which traditionally happens in the first 100 days after transplant) and chronic GVHD (after day 100). This calendar-day–based system has been augmented based on a 2006 National Institutes of Health working group report emphasizing the importance of organ-specific features of chronic GVHD in the clinical presentation of GVHD.7 Histologic changes in chronic organ GVHD tend to include more fibrotic features, whereas in acute GVHD more inflammatory changes are seen. The NIH working group report also stressed the importance of obtaining a biopsy specimen for histopathologic review and interdisciplinary collaboration to arrive at a consensus diagnosis, and noted the limitations of using histologic changes as the sole determinant of a “gold standard” diagnosis.7 GVHD can directly predispose patients to pulmonary GVHD and indirectly predispose them to infectious complications because the mainstay of therapy for GVHD is increased immunosuppression.

Pretransplant Evaluation

Case Patient 1

A 56-year-old man is diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) after presenting with signs and symptoms consistent with pancytopenia. He has a past medical history of chronic sinus congestion, arthritis, depression, chronic pain, and carpal tunnel surgery. He is employed as an oilfield worker and has a 40-pack-year smoking history, but he recently cut back to half a pack per day. He is being evaluated for allogeneic transplant with his brother as the donor and the planned conditioning regimen is total body irradiation (TBI), thiotepa, cyclophosphamide, and antithymocyte globulin with T-cell depletion. Routine pretransplant pulmonary function testing (PFT) reveals a restrictive pattern and he is sent for pretransplant pulmonary evaluation.

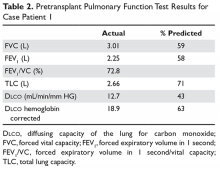

Physical exam reveals a chronically ill appearing man. He is afebrile, the respiratory rate is 16 breaths/min, blood pressure is 145/88 mm Hg, heart rate is 92 beats/min, and oxygen saturation is 95%. He is in no distress. Auscultation of the chest reveals slightly diminished breath sounds bilaterally but is clear and without wheezes, rhonchi, or rales. Heart exam shows regular rate and rhythm without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. Extremities reveal no edema or rashes. Otherwise, the remainder of the exam is normal. The patient’s PFT results are shown in Table 2.

- What aspects of this patient’s history put him at risk for pulmonary complications after transplantation?

Risk Factors for Pulmonary Complications

Predicting who is at risk for pulmonary complications is difficult. Complications are generally divided into infectious and noninfectious categories. Regardless of category, allogeneic HSCT recipients are at increased risk compared with autologous recipients, but even in autologous transplants, more than 25% of patients will develop pulmonary complications in the first year.8 Prior to transplant, patients undergo full PFT. Early on, many studies attempted to show relationships between various factors and post-transplant pulmonary complications. Factors that were implicated were forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (D

Another sometimes overlooked risk before transplantation is restrictive lung disease. One study showed a twofold increase in respiratory failure and mortality if there was pretransplant restriction based on TLC < 80%.16

An interesting study by one group in pretransplant evaluation found decreased muscle strength by maximal inspiratory muscle strength (PImax), maximal expiratory muscle strength (PEmax), dominant hand grip strength, and 6-minute walk test (6MWT) distance prior to allogeneic transplant, but did not find a relationship between these variables and mortality.17 While this study had a small sample size, these findings likely deserve continued investigation.18

- What methods are used to calculate risk for complications?

Risk Scoring Systems

Several pretransplantation risk scores have been developed. In a study that looked at more than 2500 allogeneic transplants, Parimon et al showed that risk of mortality and respiratory failure could be estimated prior to transplant using a scoring system—the Lung Function Score (LFS)—that combines the FEV1 and D

The Pretransplantation Assessment of Mortality score, initially developed in 2006, predicts mortality within the first 2 years after HSCT based on 8 clinical factors: disease risk, age at transplant, donor type, conditioning regimen, and markers of organ function (percentage of predicted FEV1, percentage of predicted D

- What other preoperative testing or interventions should be considered in this patient?

Since there is a high risk of infectious complications after transplant, the question of whether pretransplantation patients should undergo screening imaging may arise. There is no evidence that routine chest computed tomography (CT) reduces the risk of infectious complications after transplantation.26 An area that may be insufficiently addressed in the pretransplantation evaluation is smoking cessation counseling.27 Studies have shown an elevated risk of mortality in smokers.28-30 Others have found a higher incidence of respiratory failure but not an increased mortality.31 Overall, with the good rates of smoking cessation that can be accomplished, smokers should be counseled to quit before transplantation.

In summary, patients should undergo full PFTs prior to transplantation to help stratify risk for pulmonary complications and mortality and to establish a clinical baseline. The LFS (using FEV1 and D

Case Patient 1 Conclusion

The patient undergoes transplantation due to his lack of other treatment options. Evaluation prior to transplant, however, shows that he is at high risk for pulmonary complications. He has a LFS of 7 prior to transplant (using the D

Early Infectious Pulmonary Complications

Case Patient 2

A 27-year-old man with a medical history significant for AML and allogeneic HSCT presents with cough productive of a small amount of clear to white sputum, dyspnea on exertion, and fevers for 1 week. He also has mild nausea and a decrease in appetite. He underwent HSCT 2.5 months prior to admission, which was a matched unrelated bone marrow transplant with TBI and cyclophosphamide conditioning. His past medical history is significant only for exercise-induced asthma for which he takes a rescue inhaler infrequently prior to transplantation. His pretransplant PFTs showed normal spirometry with an FEV1 of 106% of predicted and D

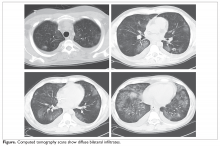

Physical exam is notable for fever of 101.0°F, heart rate 80 beats/min, respiratory rate 16 breaths/ min, and blood pressure 142/78 mm Hg; an admission oxygen saturation is 93% on room air. Lungs show bibasilar crackles and the remainder of the exam is normal. Laboratory testing shows a white blood cell count of 2400 cells/μL, hemoglobin 7.6 g/dL, and platelet count 66 × 103/μL. Creatinine is 1.0 mg/dL. Chest radiograph shows ill-defined bilateral lower-lobe infiltrates. CT scans are shown in the Figure.

- For which infectious complications is this patient most at risk?

Pneumonia

A prospective trial in the HSCT population reported a pneumonia incidence rate of 68%, and pneumonia is more common in allogeneic HSCT with prolonged immunosuppressive therapy.32 Development of pneumonia within 100 days of transplant directly correlates with nonrelapsed mortality.33 Early detection is key, and bronchoscopy within the first 5 days of symptoms has been shown to change therapy in approximately 40% of cases but has not been shown to affect mortality.34 The clinical presentation of pneumonia in the HSCT population can be variable because of the presence of neutropenia and profound immunosuppression. Traditionally accepted diagnostic criteria of fevers, sputum production, and new infiltrates should be used with caution, and an appropriately high index of suspicion should be maintained. Progression to respiratory failure, regardless of causative organism of infection, portends a poor prognosis, with mortality rates estimated at 70% to 90%.35,36 Several transplant-specific factors may affect early infections. For instance, UCB transplants have been found to have a higher incidence of invasive aspergillosis and cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections but without higher mortality attributed to the infections.37

Bacterial Pneumonia

Bacterial pneumonia accounts for 20% to 50% of pneumonia cases in HSCT recipients.38 Gram-negative organisms, specifically Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli, were reported to be the most common pathologic bacteria in recent prospective trials, whereas previous retrospective trials showed that common community-acquired organisms were the most common cause of pneumonia in HSCT recipients.32,39 This underscores the importance of being aware of the clinical prevalence of microorganisms and local antibiograms, along with associated institutional susceptibility profiles. Initiation of immediate empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics is essential when bacterial pneumonia is suspected.

Viral Pneumonia

The prevalence of viral pneumonia in stem cell transplant recipients is estimated at 28%,32 with most cases being caused by community viral pathogens such as rhinovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza A and B, and parainfluenza.39 The prevention, prophylaxis, and early treatment of viral pneumonias, specifically CMV infection, have decreased the mortality associated with early pneumonia after HSCT. Co-infection with bacterial organisms must be considered and has been associated with increased mortality in the intensive care unit setting.40

Supportive treatment with rhinovirus infection is sufficient as the disease is usually self-limited in immunocompromised patients. In contrast, infection with RSV in the lower respiratory tract is associated with increased mortality in prior reports, and recent studies suggest that further exploration of prophylaxis strategies is warranted.41 Treatment with ribavirin remains the backbone of therapy, but drug toxicity continues to limit its use. The addition of immunomodulators such as RSV immune globulin or palivizumab to ribavirin remains controversial, but a retrospective review suggests that early treatment may prevent progression to lower respiratory tract infection and lead to improved mortality.42 Infection with influenza A/B must be considered during influenza season. Treatment with oseltamivir may shorten the duration of disease when influenza A/B or parainfluenza are detected. Reactivation of latent herpes simplex virus during the pre-engraftment phase should also be considered. Treatment is similar to that in nonimmunocompromised hosts. When CMV pneumonia is suspected, careful history regarding compliance with prophylactic antivirals and CMV status of both the recipient and donor are key. A presumptive diagnosis can be made with the presence of appropriate clinical scenario, supportive radiographic images showing areas of ground-glass opacification or consolidation, and positive CMV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay. Visualization of inclusion bodies on lung biopsy tissue remains the gold standard for diagnosis. Treatment consists of CMV immunoglobulin and ganciclovir.

Fungal Pneumonia

Early fungal pneumonias have been associated with increased mortality in the HSCT population.43 Clinical suspicion should remain high and compliance with antifungal prophylaxis should be questioned thoroughly. Invasive aspergillosis (IA) remains the most common fungal infection. A bimodal distribution of onset of infection peaking on day 16 and again on day 96 has been described in the literature.44 Patients often present with classic pneumonia symptoms, but these may be accompanied by hemoptysis. Proven IA diagnosis requires visualization of fungal forms from biopsy or needle aspiration or a positive culture obtained in a sterile fashion.45 Most clinical data comes from experience with probable and possible diagnosis of IA. Bronchoalveolar lavage with testing with Aspergillus galactomannan assay has been shown to be clinically useful in establishing the clinical diagnosis in the HSCT population.46 Classic air-crescent findings on chest CT are helpful in establishing a possible diagnosis, but retrospective analysis reveals CT findings such as focal infiltrates and pulmonary nodular patterns are more common.47 First-line treatment with voriconazole has been shown to decrease short-term mortality attributable to IA but has not had an effect on long-term, all-cause mortality.48 Surgical resection is reserved for patients with refractory disease or patients presenting with massive hemoptysis.

Mucormycosis is an emerging disease with ever increasing prevalence in the HSCT population, reflecting the improved prophylaxis and treatment of IA. Initial clinical presentation is similar to IA, most commonly affecting the lung, although craniofacial involvement is classic for mucormycosis, especially in HSCT patients with diabetes.49Mucor infections can present with massive hemoptysis due to tissue invasion and disregard for tissue and fascial planes. Diagnosis of mucormycosis is associated with as much as a six-fold increase in risk for death. Diagnosis requires identification of the organism by examination or culture and biopsy is often necessary.50,51 Amphotericin B remains first-line therapy as mucormycosis is resistant to azole antifungals, with higher doses recommended for cerebral involvement.52

Candida pulmonary infections during the early HSCT period are becoming increasingly rare due to widespread use of fluconazole prophylaxis and early treatment of mucosal involvement during neutropenia. Endemic fungal infections such as blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, and histoplasmosis should be considered in patients inhabiting specific geographic areas or with recent travel to these areas.

- What test should be performed to evaluate for infectious causes of pneumonia?

Role of Flexible Fiberoptic Bronchoscopy

The utility of flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy (FOB) in immune-compromised patients for the evaluation of pulmonary infiltrates is a frequently debated topic. Current studies suggest a diagnosis can be made in approximately 80% of cases in the immune-compromised population.32,53 Noninvasive testing such as urine and serum antigens, sputum cultures, Aspergillus galactomannan assays, viral nasal swabs, and PCR studies often lead to a diagnosis in appropriate clinical scenarios. Conservative management would dictate the use of noninvasive testing whenever possible, and randomized controlled trials have shown noninvasive testing to be noninferior to FOB in preventing need for mechanical ventilation, with no difference in overall mortality.54 FOB has been shown to be most useful in establishing a diagnosis when an infectious etiology is suspected.55 In multivariate analysis, a delay in the identification of the etiology of pulmonary infiltrate was associated with increased mortality.56 Additionally, early FOB was found to be superior to late FOB in revealing a diagnosis. 32,57 Despite its ability to detect the cause of pulmonary disease, direct antibiotic therapy, and possibly change therapy, FOB with diagnostic maneuvers has not been shown to affect mortality.58 In a large case series, FOB with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) revealed a diagnosis in approximately 30% to 50% of cases. The addition of transbronchial biopsy did not improve diagnostic utility.58 More recent studies have confirmed that the addition of transbronchial biopsy does not add to diagnostic yield and is associated with increased adverse events.59 The appropriate use of advanced techniques such as endobronchial ultrasound–guided transbronchial needle aspirations, endobronchial biopsy, and CT-guided navigational bronchoscopy has not been established and should be considered on a case-by-case basis. In summary, routine early BAL is the diagnostic test of choice, especially when infectious pulmonary complications are suspected.

Contraindications for FOB in this population mirror those in the general population. These include acute severe hypoxemic respiratory failure, myocardial ischemia or acute coronary syndrome within 2 weeks of procedure, severe thrombocytopenia, and inability to provide or obtain informed consent from patient or health care power of attorney. Coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia are common comorbid conditions in the HSCT population. A platelet count of < 20 × 103/µL has generally been used as a cut-off for routine FOB with BAL.60 Risks of the procedures should be discussed clearly with the patient, but simple FOB for airway evaluation and BAL is generally well tolerated even under these conditions.

Early Nonifectious Pulmonary Complications

Case Patient 2 Continued

Bronchoscopy with BAL performed the day after admission is unremarkable and stains and cultures are negative for viral, bacterial, and fungal organisms. The patient is initially started on broad-spectrum antibiotics, but his oxygenation continues to worsen to the point that he is placed on noninvasive positive pressure ventilation. He is started empirically on amphotericin B and eventually is intubated. VATS lung biopsy is ultimately performed and pathology is consistent with diffuse alveolar damage.

- Based on these biopsy findings, what is the diagnosis?

Based on the pathology consistent with diffuse alveolar damage, a diagnosis of idiopathic pneumonia syndrome (IPS) is made.

- What noninfectious pulmonary complications occur in the early post-transplant period?

The overall incidence of noninfectious pulmonary complications after HSCT is generally estimated at 20% to 30%.32 Acute pulmonary edema is a common very early noninfectious pulmonary complication and clinically the most straightforward to treat. Three distinct clinical syndromes—peri-engraftment respiratory distress syndrome (PERDS), diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH), and IPS—comprise the remainder of the pertinent early noninfectious complications. Clinical presentation differs based upon the disease entity. Recent studies have evaluated the role of angiotensin-converting enzyme polymorphisms as a predictive marker for risk of developing early noninfectious pulmonary complications.61

Peri-Engraftment Respiratory Distress Syndrome

PERDS is a clinical syndrome comprising the cardinal features of erythematous rash and fever along with noncardiogenic pulmonary infiltrates and hypoxemia that occur in the peri-engraftment period, defined as recovery of absolute neutrophil count to > 500/μL on 2 consecutive days.62 PERDS occurs in the autologous HSCT population and may be a clinical correlate to early GVHD in the allogeneic HSCT population. It is hypothesized that the pathophysiology underlying PERDS is an autoimmune-related capillary leak caused by pro-inflammatory cytokine release.63 Treatment remains anecdotal and currently consists of supportive care and high-dose corticosteroids. Some have favored limiting the use of gCSF given its role in stimulating rapid white blood cell recovery.33 Prognosis is favorable, but progression to fulminant respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation portends a poor prognosis.

Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage

DAH is clinical syndrome consisting of diffuse alveolar infiltrates on pulmonary imaging combined with progressively bloodier return per aliquot during BAL in 3 different subsegments or more than 20% hemosiderin-laden macrophages on BAL fluid evaluation. Classically, DAH is defined in the absence of pulmonary infection or cardiac dysfunction. The pathophysiology is thought to be related to inflammation of pulmonary vasculature within the alveolar walls leading to alveolitis. Although no prospective trials exist, early use of high-dose corticosteroid therapy is thought to improve outcomes;64,65 a recent study, however, showed low-dose steroids may be associated with the lowest mortality.66 Mortality is directly linked to the presence of superimposed infection, need for mechanical ventilation, late onset, and development of multiorgan failure.67

Idiopathic Pneumonia Syndrome

IPS is a complex clinical syndrome whose pathology is felt to stem from a variety of possible lung insults such as direct myeloablative drug toxicity, occult pulmonary infection, or cytokine-driven inflammation. The ATS published an article further subcategorizing IPS as different clinical entities based upon whether the primary insult involves the vascular endothelium, interstitial tissue, and airway tissue, truly idiopathic, or unclassified.68 In clinical practice, IPS is defined as widespread alveolar injury in the absence of evidence of renal failure, heart failure, and excessive fluid resuscitation. In addition, negative testing for a variety of bacterial, viral, and fungal causes is also necessary.69 Clinical syndromes included within the IPS definition are ARDS, acute interstitial pneumonia, DAH, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, and BOS.70 Risk factors for developing IPS include TBI, older age of recipient, acute GVHD, and underlying diagnosis of AML or myelodysplastic syndrome.12 In addition, it has been shown that risk for developing IPS is lower in patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT who receive non-myeloablative conditioning regimens.71 The pathologic finding in IPS is diffuse alveolar damage. A 2006 study in which investigators reviewed BAL samples from patients with IPS found that 3% of the patients had PCR evidence of human metapneumovirus infection, and a study in 2015 found PCR evidence of infection in 53% of BAL samples from patients diagnosed with IPS.72,73 This fuels the debate on whether IPS is truly an infection-driven process where the source of infection, pulmonary or otherwise, simply escapes detection. Various surfactant proteins, which play a role in decreasing surface tension within the alveolar interface and function as mediators within the innate immunity of the lung, have been studied in regard to development of IPS. Small retrospective studies have shown a trend toward lower pre-transplant serum protein surfactant D and the development of IPS.74

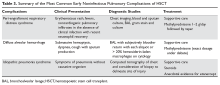

The diagnosis of IPS does not require pathologic diagnosis in most circumstances. The correct clinical findings in association with a negative infectious workup lead to a presumptive diagnosis of IPS. The extent of the infectious workup that must be completed to adequately rule out infection is often a difficult clinical question. Recent recommendations include BAL fluid evaluation for routine bacterial cultures, appropriate viral culture, and consideration of PCR testing to evaluate for Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, and Aspergillus antigens.75 Transbronchial biopsy continues to appear in recommendations, but is not routinely performed and should be completed as the patient’s clinical status permits.8,68 Table 3 reviews basic features of early noninfectious pulmonary complications.

Treatment of IPS centers around moderate to high doses of corticosteroids. Based on IPS experimental modes, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α has been implicated as an important mediator. Unfortunately, several studies evaluating etanercept have produced conflicting results, and this agent’s clinical effects on morbidity and mortality remain in question.76

- What treatment should be offered to the patient with diffuse alveolar damage on biopsy?

Treatment consists of supportive care and empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics with consideration of high-dose corticosteroids. Based upon early studies in murine models implicating TNF, pilot studies were performed evaluating etanercept as a possible safe and effective addition to high-dose systemic corticosteroids.77 Although these results were promising, data from a truncated randomized control clinical trial failed to show improvement in patient response in the adult population.76 More recent data from the same author suggests that pediatric populations with IPS are, however, responsive to etanercept and high-dose corticosteroid therapy.78 When IPS develops as a late complication, treatment with high-dose corticosteroids (2 mg/kg/day) and etanercept (0.4 mg/kg twice weekly) has been shown to improve 2-year survival.79

Case Patient 2 Conclusion

The patient is started on steroids and makes a speedy recovery. He is successfully extubated 5 days later.

Conclusion

Careful pretransplant evaluation, including a full set of pulmonary function tests, can help predict a patient’s risk for pulmonary complications after transplant, allowing risk factor modification strategies to be implemented prior to transplant, including smoking cessation. It also helps identify patients at high risk for complications who will require closer monitoring after transplantation. Early posttransplant complications include infectious and noninfectious entities. Bacterial, viral, and fungal pneumonias are in the differential of infectious pneumonia, and bronchoscopy can be helpful in establishing a diagnosis. A common, important noninfectious cause of early pulmonary complications is IPS, which is treated with steroids and sometimes anti-TNF therapy.

1. Gratwohl A, Baldomero H, Aljurf M, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a global perspective. JAMA 2010;303:1617–24.

2. Kotloff RM, Ahya VN, Crawford SW. Pulmonary complications of solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:22–48.

4. Copelan EA. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1813–26.

5. Anasetti C, Logan BR, Lee SJ, et al. Peripheral-blood stem cells versus bone marrow from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1487–96.

6. Giralt S, Ballen K, Rizzo D, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning regimen workshop: defining the dose spectrum. Report of a workshop convened by the center for international blood and marrow transplant research. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2009;15:367–9.

7. Shulman HM, Kleiner D, Lee SJ, et al. Histopathologic diagnosis of chronic graft-versus-host disease: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: II. Pathology Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2006;12:31–47.

8. Afessa B, Abdulai RM, Kremers WK, et al. Risk factors and outcome of pulmonary complications after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Chest 2012;141:442–50.

9. Bolwell BJ. Are predictive factors clinically useful in bone marrow transplantation? Bone Marrow Transplant 2003;32:853–61.

10. Carlson K, Backlund L, Smedmyr B, et al. Pulmonary function and complications subsequent to autologous bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 1994;14:805–11.

11. Clark JG, Schwartz DA, Flournoy N, et al. Risk factors for airflow obstruction in recipients of bone marrow transplants. Ann Intern Med 1987;107:648–56.

12. Crawford SW, Fisher L. Predictive value of pulmonary function tests before marrow transplantation. Chest 1992; 101:1257–64.

13. Ghalie R, Szidon JP, Thompson L, et al. Evaluation of pulmonary complications after bone marrow transplantation: the role of pretransplant pulmonary function tests. Bone Marrow Transplant 1992;10:359–65.

14. Ho VT, Weller E, Lee SJ, et al. Prognostic factors for early severe pulmonary complications after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2001;7:223–9.

15. Horak DA, Schmidt GM, Zaia JA, et al. Pretransplant pulmonary function predicts cytomegalovirus-associated interstitial pneumonia following bone marrow transplantation. Chest 1992;102:1484–90.

16. Ramirez-Sarmiento A, Orozco-Levi M, Walter EC, et al. Influence of pretransplantation restrictive lung disease on allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation outcomes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2010;16:199–206.

17. White AC, Terrin N, Miller KB, Ryan HF. Impaired respiratory and skeletal muscle strength in patients prior to hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Chest 2005;128145–52.

18. Afessa B. Pretransplant pulmonary evaluation of the blood and marrow transplant recipient. Chest 2005;128:8–10.

19. Parimon T, Madtes DK, Au DH, et al. Pretransplant lung function, respiratory failure, and mortality after stem cell transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:384–90.

20. Pavletic SZ, Martin P, Lee SJ, et al. Measuring therapeutic response in chronic graft-versus-host disease: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: IV. Response Criteria Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2006;12:252–66.

21. Parimon T, Au DH, Martin PJ, Chien JW. A risk score for mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:407–14.

22. Au BK, Gooley TA, Armand P, et al. Reevaluation of the pretransplant assessment of mortality score after allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015;21:848–54.

23. Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood 2005;106:2912–9.

24. Chien JW, Sullivan KM. Carbon monoxide diffusion capacity: how low can you go for hematopoietic cell transplantation eligibility? Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2009;15: 447–53.

25. Coffey DG, Pollyea DA, Myint H, et al. Adjusting DLCO for Hb and its effects on the Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation-specific Comorbidity Index. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013;48:1253–6.

26. Kasow KA, Krueger J, Srivastava DK, et al. Clinical utility of computed tomography screening of chest, abdomen, and sinuses before hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: the St. Jude experience. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2009;15:490–5.

27. Hamadani M, Craig M, Awan FT, Devine SM. How we approach patient evaluation for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2010;45: 1259–68.

28. Savani BN, Montero A, Wu C, et al. Prediction and prevention of transplant-related mortality from pulmonary causes after total body irradiation and allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2005;11:223–30.

29. Ehlers SL, Gastineau DA, Patten CA, et al. The impact of smoking on outcomes among patients undergoing hematopoietic SCT for the treatment of acute leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011;46:285–90.

30. Marks DI, Ballen K, Logan BR, et al. The effect of smoking on allogeneic transplant outcomes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2009;15:1277–87.

31. Tran BT, Halperin A, Chien JW. Cigarette smoking and outcomes after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2011;17:1004–11.

32. Lucena CM, Torres A, Rovira M, et al. Pulmonary complications in hematopoietic SCT: a prospective study. Bone Marrow Transplant 2014;49:1293–9.

33. Chi AK, Soubani AO, White AC, Miller KB. An update on pulmonary complications of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Chest 2013;144:1913–22.

34. Dunagan DP, Baker AM, Hurd DD, Haponik EF. Bronchoscopic evaluation of pulmonary infiltrates following bone marrow transplantation. Chest 1997;111:135–41.

35. Naeem N, Reed MD, Creger RJ, et al. Transfer of the hematopoietic stem cell transplant patient to the intensive care unit: does it really matter? Bone Marrow Transplant 2006;37:119–33.

36. Afessa B, Tefferi A, Hoagland HC, et al. Outcome of recipients of bone marrow transplants who require intensive care unit support. Mayo Clin Proc 1992;67:117–22.

37. Parody R, Martino R, de la Camara R, et al. Fungal and viral infections after allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation from unrelated donors in adults: improving outcomes over time. Bone Marrow Transplant 2015;50:274–81.

38. Orasch C, Weisser M, Mertz D, et al. Comparison of infectious complications during induction/consolidation chemotherapy versus allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2010;45:521–6.

39. Aguilar-Guisado M, Jimenez-Jambrina M, Espigado I, et al. Pneumonia in allogeneic stem cell transplantation recipients: a multicenter prospective study. Clin Transplant 2011;25:E629–38.

40. Palacios G, Hornig M, Cisterna D, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae coinfection is correlated with the severity of H1N1 pandemic influenza. PLoS One 2009;4:e8540.

41. Hynicka LM, Ensor CR. Prophylaxis and treatment of respiratory syncytial virus in adult immunocompromised patients. Ann Pharmacother 2012;46:558–66.

42. Shah JN, Chemaly RF. Management of RSV infections in adult recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2011;2755–63.

43. Marr KA, Bowden RA. Fungal infections in patients undergoing blood and marrow transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis 1999;1:237–46.

44. Wald A, Leisenring W, van Burik JA, Bowden RA. Epidemiology of Aspergillus infections in a large cohort of patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation. J Infect Dis 1997;175:1459–66.

45. Ascioglu S, Rex JH, de Pauw B, et al. Defining opportunistic invasive fungal infections in immunocompromised patients with cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplants: an international consensus. Clin Infect Dis 2002;34:7–14.

46. Fisher CE, Stevens AM, Leisenring W, et al. Independent contribution of bronchoalveolar lavage and serum galactomannan in the diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Transpl Infect Dis 2014;16:505–10.

47. Kojima R, Tateishi U, Kami M, et al. Chest computed tomography of late invasive aspergillosis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2005;11:506–11.

48. Salmeron G, Porcher R, Bergeron A, et al. Persistent poor long-term prognosis of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients surviving invasive aspergillosis. Haematologica 2012;97:1357–63.

49. McNulty JS. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis: predisposing factors. Laryngoscope 1982;92(10 Pt 1):1140.

50. Walsh TJ, Gamaletsou MN, McGinnis MR, et al. Early clinical and laboratory diagnosis of invasive pulmonary, extrapulmonary, and disseminated mucormycosis (zygomycosis). Clin Infect Dis 2012;54 Suppl 1:S55–60.

51. Klingspor L, Saaedi B, Ljungman P, Szakos A. Epidemiology and outcomes of patients with invasive mould infections: a retrospective observational study from a single centre (2005-2009). Mycoses 2015;58:470–7.

52. Danion F, Aguilar C, Catherinot E, et al. Mucormycosis: new developments in a persistently devastating infection. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2015;36:692–70.

53. Rano A, Agusti C, Jimenez P, et al. Pulmonary infiltrates in non-HIV immunocompromised patients: a diagnostic approach using non-invasive and bronchoscopic procedures. Thorax 2001;56:379–87.

54. Azoulay E, Mokart D, Rabbat A, et al. Diagnostic bronchoscopy in hematology and oncology patients with acute respiratory failure: prospective multicenter data. Crit Care Med 2008;36:100–7.

55. Jain P, Sandur S, Meli Y, et al. Role of flexible bronchoscopy in immunocompromised patients with lung infiltrates. Chest 2004;125:712–22.

56. Rano A, Agusti C, Benito N, et al. Prognostic factors of non-HIV immunocompromised patients with pulmonary infiltrates. Chest 2002;122:253–61.

57. Shannon VR, Andersson BS, Lei X, et al. Utility of early versus late fiberoptic bronchoscopy in the evaluation of new pulmonary infiltrates following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2010;45:647–55.

58. Patel NR, Lee PS, Kim JH, et al. The influence of diagnostic bronchoscopy on clinical outcomes comparing adult autologous and allogeneic bone marrow transplant patients. Chest 2005;127:1388–96.

59. Chellapandian D, Lehrnbecher T, Phillips B, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage and lung biopsy in patients with cancer and hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation recipients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:501–9.

60. Carr IM, Koegelenberg CF, von Groote-Bidlingmaier F, et al. Blood loss during flexible bronchoscopy: a prospective observational study. Respiration 2012;84:312–8.

61. Miyamoto M, Onizuka M, Machida S, et al. ACE deletion polymorphism is associated with a high risk of non-infectious pulmonary complications after stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol 2014;99:175–83.

62. Capizzi SA, Kumar S, Huneke NE, et al. Peri-engraftment respiratory distress syndrome during autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2001;27:1299–303.

63. Spitzer TR. Engraftment syndrome following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2001;27:893–8.

64. Wanko SO, Broadwater G, Folz RJ, Chao NJ. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage: retrospective review of clinical outcome in allogeneic transplant recipients treated with aminocaproic acid. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2006;12:949–53.

65. Metcalf JP, Rennard SI, Reed EC, et al. Corticosteroids as adjunctive therapy for diffuse alveolar hemorrhage associated with bone marrow transplantation. University of Nebraska Medical Center Bone Marrow Transplant Group. Am J Med 1994;96:327–34.

66. Rathi NK, Tanner AR, Dinh A, et al. Low-, medium- and high-dose steroids with or without aminocaproic acid in adult hematopoietic SCT patients with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. Bone Marrow Transplant 2015;50:420–6.

67. Afessa B, Tefferi A, Litzow MR, Peters SG. Outcome of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:1364–8.

68. Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Griese M, Madtes DK, et al. An official American Thoracic Society research statement: noninfectious lung injury after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: idiopathic pneumonia syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:1262–79.

69. Clark JG, Hansen JA, Hertz MI, Pet al. NHLBI workshop summary. Idiopathic pneumonia syndrome after bone marrow transplantation. Am Rev Resp Dis 1993;147:1601–6.

70. Vande Vusse LK, Madtes DK. Early onset noninfectious pulmonary syndromes after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Clin Chest Med 2017;38:233–48.

71. Fukuda T, Hackman RC, Guthrie KA, et al. Risks and outcomes of idiopathic pneumonia syndrome after nonmyeloablative and conventional conditioning regimens for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2003;102:2777–85.

72. Englund JA, Boeckh M, Kuypers J, et al. Brief communication: fatal human metapneumovirus infection in stem-cell transplant recipients. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:344–9.

73. Seo S, Renaud C, Kuypers JM, et al. Idiopathic pneumonia syndrome after hematopoietic cell transplantation: evidence of occult infectious etiologies. Blood 2015;125:3789–97.

74. Nakane T, Nakamae H, Kamoi H, et al. Prognostic value of serum surfactant protein D level prior to transplant for the development of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome and idiopathic pneumonia syndrome following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2008;42:43–9.

75. Gilbert CR, Lerner A, Baram M, Awsare BK. Utility of flexible bronchoscopy in the evaluation of pulmonary infiltrates in the hematopoietic stem cell transplant population—a single center fourteen year experience. Arch Bronconeumol 2013;49:189–95.

76. Yanik GA, Horowitz MM, Weisdorf DJ, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor: enbrel (etanercept) for the treatment of idiopathic pneumonia syndrome after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: blood and marrow transplant clinical trials network protocol. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2014;20:858–64.

77. Levine JE, Paczesny S, Mineishi S, et al. Etanercept plus methylprednisolone as initial therapy for acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood 2008;111:2470–5.

78. Yanik GA, Grupp SA, Pulsipher MA, et al. TNF-receptor inhibitor therapy for the treatment of children with idiopathic pneumonia syndrome. A joint Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Consortium and Children’s Oncology Group Study (ASCT0521). Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015;21:67–73.

79. Thompson J, Yin Z, D’Souza A, et al. Etanercept and corticosteroid therapy for the treatment of late-onset idiopathic pneumonia syndrome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant J 2017; 23:1955–60.

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is widely used in the economically developed world to treat a variety of hematologic malignancies as well as nonmalignant diseases and solid tumors. An estimated 17,900 HSCTs were performed in 2011, and survival rates continue to increase.1 Pulmonary complications post HSCT are common, with rates ranging from 40% to 60%, and are associated with increased morbidity and mortality.2

Clinical diagnosis of pulmonary complications in the HSCT population has been aided by a previously well-defined chronology of the most common diseases.3 Historically, early pulmonary complications were defined as pulmonary complications occurring within 100 days of HSCT (corresponding to the acute graft-versus-host disease [GVHD] period). Late pulmonary complications are those that occur thereafter. This timeline, however, is now more variable given the increasing indications for HSCT, the use of reduced-intensity conditioning strategies, and varied individual immune reconstitution. This article discusses the management of early post-HSCT pulmonary complications; late post-HSCT pulmonary complications will be discussed in a separate follow-up article.

Transplant Basics

The development of pulmonary complications is affected by many factors associated with the transplant. Autologous transplantation involves the collection of a patient’s own stem cells, appropriate storage and processing, and re-implantation after induction therapy. During induction therapy, the patient undergoes high-dose chemotherapy or radiation therapy that ablates the bone marrow. The stem cells are then transfused back into the patient to repopulate the bone marrow. Allogeneic transplants involve the collection of stem cells from a donor. Donors are matched as closely as possible to the recipient’s histocompatibility antigen (HLA) haplotypes to prevent graft failure and rejection. The donor can be related or unrelated to the recipient. If there is not a possibility of a related match (from a sibling), then a national search is undertaken to look for a match through the National Marrow Donor Program. There are fewer transplant reactions and occurrences of GVHD if the major HLAs of the donor and recipient match. Table 1 reviews basic definitions pertaining to HSCT.

How the cells for transplantation are obtained is also an important factor in the rate of complications. There are 3 main sources: peripheral blood, bone marrow, and umbilical cord. Peripheral stem cell harvesting involves exposing the donor to granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (gCSF), which increases peripheral circulation of stem cells. These cells are then collected and infused into the recipient after the recipient has completed an induction regimen involving chemotherapy and/or radiation, depending on the protocol. This procedure is called peripheral blood stem cell transplant (PBSCT). Stem cells can also be directly harvested from bone marrow cells, which are collected from repeated aspiration of bone marrow from the posterior iliac crest.4 This technique is most common in children, whereas in adults peripheral blood stem cells are the most common source. Overall mortality does not differ based on the source of the stem cells. It is postulated that GVHD may be more common in patients undergoing PBSCT, but the graft failure rate may be lower.5

The third option is umbilical cord blood (UCB) as the source of stem cells. This involves the collection of umbilical cord blood that is prepared and frozen after birth. It has a smaller volume of cells, and although fewer cells are needed when using UCB, 2 separate donors may be required for a single adult recipient. The engraftment of the stem cells is slower and infections in the post-transplant period are more common. Prior reports indicate GVHD rates may be lower.4 While the use of UCB is not common in adults, the incidence has doubled over the past decade, increasing from 3% to 6%.

The conditioning regimen can influence pulmonary complications. Traditionally, an ablative transplant involves high-dose chemotherapy or radiation to eradicate the recipient’s bone marrow. This regimen can lead to many complications, especially in the immediate post-transplant period. In the past 10 years, there has been increasing interest in non-myeloablative, or reduced-intensity, conditioning transplants.6 These “mini transplants” involve smaller doses of chemotherapy or radiation, which do not totally eradicate the bone marrow; after the transplant a degree of chimerism develops where the donor and recipient stem cells coexist. The medications in the preparative regimen also should be considered because they can affect pulmonary complications after transplant. Certain chemotherapeutic agents such as carmustine, bleomycin, and many others can lead to acute and chronic presentations of pulmonary diseases such as hypersensitivity pneumonitis, pulmonary fibrosis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and abnormal pulmonary function testing.

After the HSCT, GVHD can develop in more than 50% of allogeneic recipients.3 The incidence of GVHD has been reported to be increasing over the past 12 years.It is divided into acute GVHD (which traditionally happens in the first 100 days after transplant) and chronic GVHD (after day 100). This calendar-day–based system has been augmented based on a 2006 National Institutes of Health working group report emphasizing the importance of organ-specific features of chronic GVHD in the clinical presentation of GVHD.7 Histologic changes in chronic organ GVHD tend to include more fibrotic features, whereas in acute GVHD more inflammatory changes are seen. The NIH working group report also stressed the importance of obtaining a biopsy specimen for histopathologic review and interdisciplinary collaboration to arrive at a consensus diagnosis, and noted the limitations of using histologic changes as the sole determinant of a “gold standard” diagnosis.7 GVHD can directly predispose patients to pulmonary GVHD and indirectly predispose them to infectious complications because the mainstay of therapy for GVHD is increased immunosuppression.

Pretransplant Evaluation

Case Patient 1

A 56-year-old man is diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) after presenting with signs and symptoms consistent with pancytopenia. He has a past medical history of chronic sinus congestion, arthritis, depression, chronic pain, and carpal tunnel surgery. He is employed as an oilfield worker and has a 40-pack-year smoking history, but he recently cut back to half a pack per day. He is being evaluated for allogeneic transplant with his brother as the donor and the planned conditioning regimen is total body irradiation (TBI), thiotepa, cyclophosphamide, and antithymocyte globulin with T-cell depletion. Routine pretransplant pulmonary function testing (PFT) reveals a restrictive pattern and he is sent for pretransplant pulmonary evaluation.

Physical exam reveals a chronically ill appearing man. He is afebrile, the respiratory rate is 16 breaths/min, blood pressure is 145/88 mm Hg, heart rate is 92 beats/min, and oxygen saturation is 95%. He is in no distress. Auscultation of the chest reveals slightly diminished breath sounds bilaterally but is clear and without wheezes, rhonchi, or rales. Heart exam shows regular rate and rhythm without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. Extremities reveal no edema or rashes. Otherwise, the remainder of the exam is normal. The patient’s PFT results are shown in Table 2.

- What aspects of this patient’s history put him at risk for pulmonary complications after transplantation?

Risk Factors for Pulmonary Complications

Predicting who is at risk for pulmonary complications is difficult. Complications are generally divided into infectious and noninfectious categories. Regardless of category, allogeneic HSCT recipients are at increased risk compared with autologous recipients, but even in autologous transplants, more than 25% of patients will develop pulmonary complications in the first year.8 Prior to transplant, patients undergo full PFT. Early on, many studies attempted to show relationships between various factors and post-transplant pulmonary complications. Factors that were implicated were forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (D

Another sometimes overlooked risk before transplantation is restrictive lung disease. One study showed a twofold increase in respiratory failure and mortality if there was pretransplant restriction based on TLC < 80%.16

An interesting study by one group in pretransplant evaluation found decreased muscle strength by maximal inspiratory muscle strength (PImax), maximal expiratory muscle strength (PEmax), dominant hand grip strength, and 6-minute walk test (6MWT) distance prior to allogeneic transplant, but did not find a relationship between these variables and mortality.17 While this study had a small sample size, these findings likely deserve continued investigation.18

- What methods are used to calculate risk for complications?

Risk Scoring Systems

Several pretransplantation risk scores have been developed. In a study that looked at more than 2500 allogeneic transplants, Parimon et al showed that risk of mortality and respiratory failure could be estimated prior to transplant using a scoring system—the Lung Function Score (LFS)—that combines the FEV1 and D

The Pretransplantation Assessment of Mortality score, initially developed in 2006, predicts mortality within the first 2 years after HSCT based on 8 clinical factors: disease risk, age at transplant, donor type, conditioning regimen, and markers of organ function (percentage of predicted FEV1, percentage of predicted D

- What other preoperative testing or interventions should be considered in this patient?

Since there is a high risk of infectious complications after transplant, the question of whether pretransplantation patients should undergo screening imaging may arise. There is no evidence that routine chest computed tomography (CT) reduces the risk of infectious complications after transplantation.26 An area that may be insufficiently addressed in the pretransplantation evaluation is smoking cessation counseling.27 Studies have shown an elevated risk of mortality in smokers.28-30 Others have found a higher incidence of respiratory failure but not an increased mortality.31 Overall, with the good rates of smoking cessation that can be accomplished, smokers should be counseled to quit before transplantation.

In summary, patients should undergo full PFTs prior to transplantation to help stratify risk for pulmonary complications and mortality and to establish a clinical baseline. The LFS (using FEV1 and D

Case Patient 1 Conclusion

The patient undergoes transplantation due to his lack of other treatment options. Evaluation prior to transplant, however, shows that he is at high risk for pulmonary complications. He has a LFS of 7 prior to transplant (using the D

Early Infectious Pulmonary Complications

Case Patient 2

A 27-year-old man with a medical history significant for AML and allogeneic HSCT presents with cough productive of a small amount of clear to white sputum, dyspnea on exertion, and fevers for 1 week. He also has mild nausea and a decrease in appetite. He underwent HSCT 2.5 months prior to admission, which was a matched unrelated bone marrow transplant with TBI and cyclophosphamide conditioning. His past medical history is significant only for exercise-induced asthma for which he takes a rescue inhaler infrequently prior to transplantation. His pretransplant PFTs showed normal spirometry with an FEV1 of 106% of predicted and D

Physical exam is notable for fever of 101.0°F, heart rate 80 beats/min, respiratory rate 16 breaths/ min, and blood pressure 142/78 mm Hg; an admission oxygen saturation is 93% on room air. Lungs show bibasilar crackles and the remainder of the exam is normal. Laboratory testing shows a white blood cell count of 2400 cells/μL, hemoglobin 7.6 g/dL, and platelet count 66 × 103/μL. Creatinine is 1.0 mg/dL. Chest radiograph shows ill-defined bilateral lower-lobe infiltrates. CT scans are shown in the Figure.

- For which infectious complications is this patient most at risk?

Pneumonia

A prospective trial in the HSCT population reported a pneumonia incidence rate of 68%, and pneumonia is more common in allogeneic HSCT with prolonged immunosuppressive therapy.32 Development of pneumonia within 100 days of transplant directly correlates with nonrelapsed mortality.33 Early detection is key, and bronchoscopy within the first 5 days of symptoms has been shown to change therapy in approximately 40% of cases but has not been shown to affect mortality.34 The clinical presentation of pneumonia in the HSCT population can be variable because of the presence of neutropenia and profound immunosuppression. Traditionally accepted diagnostic criteria of fevers, sputum production, and new infiltrates should be used with caution, and an appropriately high index of suspicion should be maintained. Progression to respiratory failure, regardless of causative organism of infection, portends a poor prognosis, with mortality rates estimated at 70% to 90%.35,36 Several transplant-specific factors may affect early infections. For instance, UCB transplants have been found to have a higher incidence of invasive aspergillosis and cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections but without higher mortality attributed to the infections.37

Bacterial Pneumonia

Bacterial pneumonia accounts for 20% to 50% of pneumonia cases in HSCT recipients.38 Gram-negative organisms, specifically Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli, were reported to be the most common pathologic bacteria in recent prospective trials, whereas previous retrospective trials showed that common community-acquired organisms were the most common cause of pneumonia in HSCT recipients.32,39 This underscores the importance of being aware of the clinical prevalence of microorganisms and local antibiograms, along with associated institutional susceptibility profiles. Initiation of immediate empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics is essential when bacterial pneumonia is suspected.

Viral Pneumonia

The prevalence of viral pneumonia in stem cell transplant recipients is estimated at 28%,32 with most cases being caused by community viral pathogens such as rhinovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza A and B, and parainfluenza.39 The prevention, prophylaxis, and early treatment of viral pneumonias, specifically CMV infection, have decreased the mortality associated with early pneumonia after HSCT. Co-infection with bacterial organisms must be considered and has been associated with increased mortality in the intensive care unit setting.40

Supportive treatment with rhinovirus infection is sufficient as the disease is usually self-limited in immunocompromised patients. In contrast, infection with RSV in the lower respiratory tract is associated with increased mortality in prior reports, and recent studies suggest that further exploration of prophylaxis strategies is warranted.41 Treatment with ribavirin remains the backbone of therapy, but drug toxicity continues to limit its use. The addition of immunomodulators such as RSV immune globulin or palivizumab to ribavirin remains controversial, but a retrospective review suggests that early treatment may prevent progression to lower respiratory tract infection and lead to improved mortality.42 Infection with influenza A/B must be considered during influenza season. Treatment with oseltamivir may shorten the duration of disease when influenza A/B or parainfluenza are detected. Reactivation of latent herpes simplex virus during the pre-engraftment phase should also be considered. Treatment is similar to that in nonimmunocompromised hosts. When CMV pneumonia is suspected, careful history regarding compliance with prophylactic antivirals and CMV status of both the recipient and donor are key. A presumptive diagnosis can be made with the presence of appropriate clinical scenario, supportive radiographic images showing areas of ground-glass opacification or consolidation, and positive CMV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay. Visualization of inclusion bodies on lung biopsy tissue remains the gold standard for diagnosis. Treatment consists of CMV immunoglobulin and ganciclovir.

Fungal Pneumonia

Early fungal pneumonias have been associated with increased mortality in the HSCT population.43 Clinical suspicion should remain high and compliance with antifungal prophylaxis should be questioned thoroughly. Invasive aspergillosis (IA) remains the most common fungal infection. A bimodal distribution of onset of infection peaking on day 16 and again on day 96 has been described in the literature.44 Patients often present with classic pneumonia symptoms, but these may be accompanied by hemoptysis. Proven IA diagnosis requires visualization of fungal forms from biopsy or needle aspiration or a positive culture obtained in a sterile fashion.45 Most clinical data comes from experience with probable and possible diagnosis of IA. Bronchoalveolar lavage with testing with Aspergillus galactomannan assay has been shown to be clinically useful in establishing the clinical diagnosis in the HSCT population.46 Classic air-crescent findings on chest CT are helpful in establishing a possible diagnosis, but retrospective analysis reveals CT findings such as focal infiltrates and pulmonary nodular patterns are more common.47 First-line treatment with voriconazole has been shown to decrease short-term mortality attributable to IA but has not had an effect on long-term, all-cause mortality.48 Surgical resection is reserved for patients with refractory disease or patients presenting with massive hemoptysis.

Mucormycosis is an emerging disease with ever increasing prevalence in the HSCT population, reflecting the improved prophylaxis and treatment of IA. Initial clinical presentation is similar to IA, most commonly affecting the lung, although craniofacial involvement is classic for mucormycosis, especially in HSCT patients with diabetes.49Mucor infections can present with massive hemoptysis due to tissue invasion and disregard for tissue and fascial planes. Diagnosis of mucormycosis is associated with as much as a six-fold increase in risk for death. Diagnosis requires identification of the organism by examination or culture and biopsy is often necessary.50,51 Amphotericin B remains first-line therapy as mucormycosis is resistant to azole antifungals, with higher doses recommended for cerebral involvement.52

Candida pulmonary infections during the early HSCT period are becoming increasingly rare due to widespread use of fluconazole prophylaxis and early treatment of mucosal involvement during neutropenia. Endemic fungal infections such as blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, and histoplasmosis should be considered in patients inhabiting specific geographic areas or with recent travel to these areas.

- What test should be performed to evaluate for infectious causes of pneumonia?

Role of Flexible Fiberoptic Bronchoscopy

The utility of flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy (FOB) in immune-compromised patients for the evaluation of pulmonary infiltrates is a frequently debated topic. Current studies suggest a diagnosis can be made in approximately 80% of cases in the immune-compromised population.32,53 Noninvasive testing such as urine and serum antigens, sputum cultures, Aspergillus galactomannan assays, viral nasal swabs, and PCR studies often lead to a diagnosis in appropriate clinical scenarios. Conservative management would dictate the use of noninvasive testing whenever possible, and randomized controlled trials have shown noninvasive testing to be noninferior to FOB in preventing need for mechanical ventilation, with no difference in overall mortality.54 FOB has been shown to be most useful in establishing a diagnosis when an infectious etiology is suspected.55 In multivariate analysis, a delay in the identification of the etiology of pulmonary infiltrate was associated with increased mortality.56 Additionally, early FOB was found to be superior to late FOB in revealing a diagnosis. 32,57 Despite its ability to detect the cause of pulmonary disease, direct antibiotic therapy, and possibly change therapy, FOB with diagnostic maneuvers has not been shown to affect mortality.58 In a large case series, FOB with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) revealed a diagnosis in approximately 30% to 50% of cases. The addition of transbronchial biopsy did not improve diagnostic utility.58 More recent studies have confirmed that the addition of transbronchial biopsy does not add to diagnostic yield and is associated with increased adverse events.59 The appropriate use of advanced techniques such as endobronchial ultrasound–guided transbronchial needle aspirations, endobronchial biopsy, and CT-guided navigational bronchoscopy has not been established and should be considered on a case-by-case basis. In summary, routine early BAL is the diagnostic test of choice, especially when infectious pulmonary complications are suspected.

Contraindications for FOB in this population mirror those in the general population. These include acute severe hypoxemic respiratory failure, myocardial ischemia or acute coronary syndrome within 2 weeks of procedure, severe thrombocytopenia, and inability to provide or obtain informed consent from patient or health care power of attorney. Coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia are common comorbid conditions in the HSCT population. A platelet count of < 20 × 103/µL has generally been used as a cut-off for routine FOB with BAL.60 Risks of the procedures should be discussed clearly with the patient, but simple FOB for airway evaluation and BAL is generally well tolerated even under these conditions.

Early Nonifectious Pulmonary Complications

Case Patient 2 Continued

Bronchoscopy with BAL performed the day after admission is unremarkable and stains and cultures are negative for viral, bacterial, and fungal organisms. The patient is initially started on broad-spectrum antibiotics, but his oxygenation continues to worsen to the point that he is placed on noninvasive positive pressure ventilation. He is started empirically on amphotericin B and eventually is intubated. VATS lung biopsy is ultimately performed and pathology is consistent with diffuse alveolar damage.

- Based on these biopsy findings, what is the diagnosis?

Based on the pathology consistent with diffuse alveolar damage, a diagnosis of idiopathic pneumonia syndrome (IPS) is made.

- What noninfectious pulmonary complications occur in the early post-transplant period?

The overall incidence of noninfectious pulmonary complications after HSCT is generally estimated at 20% to 30%.32 Acute pulmonary edema is a common very early noninfectious pulmonary complication and clinically the most straightforward to treat. Three distinct clinical syndromes—peri-engraftment respiratory distress syndrome (PERDS), diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH), and IPS—comprise the remainder of the pertinent early noninfectious complications. Clinical presentation differs based upon the disease entity. Recent studies have evaluated the role of angiotensin-converting enzyme polymorphisms as a predictive marker for risk of developing early noninfectious pulmonary complications.61

Peri-Engraftment Respiratory Distress Syndrome

PERDS is a clinical syndrome comprising the cardinal features of erythematous rash and fever along with noncardiogenic pulmonary infiltrates and hypoxemia that occur in the peri-engraftment period, defined as recovery of absolute neutrophil count to > 500/μL on 2 consecutive days.62 PERDS occurs in the autologous HSCT population and may be a clinical correlate to early GVHD in the allogeneic HSCT population. It is hypothesized that the pathophysiology underlying PERDS is an autoimmune-related capillary leak caused by pro-inflammatory cytokine release.63 Treatment remains anecdotal and currently consists of supportive care and high-dose corticosteroids. Some have favored limiting the use of gCSF given its role in stimulating rapid white blood cell recovery.33 Prognosis is favorable, but progression to fulminant respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation portends a poor prognosis.

Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage

DAH is clinical syndrome consisting of diffuse alveolar infiltrates on pulmonary imaging combined with progressively bloodier return per aliquot during BAL in 3 different subsegments or more than 20% hemosiderin-laden macrophages on BAL fluid evaluation. Classically, DAH is defined in the absence of pulmonary infection or cardiac dysfunction. The pathophysiology is thought to be related to inflammation of pulmonary vasculature within the alveolar walls leading to alveolitis. Although no prospective trials exist, early use of high-dose corticosteroid therapy is thought to improve outcomes;64,65 a recent study, however, showed low-dose steroids may be associated with the lowest mortality.66 Mortality is directly linked to the presence of superimposed infection, need for mechanical ventilation, late onset, and development of multiorgan failure.67

Idiopathic Pneumonia Syndrome

IPS is a complex clinical syndrome whose pathology is felt to stem from a variety of possible lung insults such as direct myeloablative drug toxicity, occult pulmonary infection, or cytokine-driven inflammation. The ATS published an article further subcategorizing IPS as different clinical entities based upon whether the primary insult involves the vascular endothelium, interstitial tissue, and airway tissue, truly idiopathic, or unclassified.68 In clinical practice, IPS is defined as widespread alveolar injury in the absence of evidence of renal failure, heart failure, and excessive fluid resuscitation. In addition, negative testing for a variety of bacterial, viral, and fungal causes is also necessary.69 Clinical syndromes included within the IPS definition are ARDS, acute interstitial pneumonia, DAH, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, and BOS.70 Risk factors for developing IPS include TBI, older age of recipient, acute GVHD, and underlying diagnosis of AML or myelodysplastic syndrome.12 In addition, it has been shown that risk for developing IPS is lower in patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT who receive non-myeloablative conditioning regimens.71 The pathologic finding in IPS is diffuse alveolar damage. A 2006 study in which investigators reviewed BAL samples from patients with IPS found that 3% of the patients had PCR evidence of human metapneumovirus infection, and a study in 2015 found PCR evidence of infection in 53% of BAL samples from patients diagnosed with IPS.72,73 This fuels the debate on whether IPS is truly an infection-driven process where the source of infection, pulmonary or otherwise, simply escapes detection. Various surfactant proteins, which play a role in decreasing surface tension within the alveolar interface and function as mediators within the innate immunity of the lung, have been studied in regard to development of IPS. Small retrospective studies have shown a trend toward lower pre-transplant serum protein surfactant D and the development of IPS.74

The diagnosis of IPS does not require pathologic diagnosis in most circumstances. The correct clinical findings in association with a negative infectious workup lead to a presumptive diagnosis of IPS. The extent of the infectious workup that must be completed to adequately rule out infection is often a difficult clinical question. Recent recommendations include BAL fluid evaluation for routine bacterial cultures, appropriate viral culture, and consideration of PCR testing to evaluate for Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, and Aspergillus antigens.75 Transbronchial biopsy continues to appear in recommendations, but is not routinely performed and should be completed as the patient’s clinical status permits.8,68 Table 3 reviews basic features of early noninfectious pulmonary complications.

Treatment of IPS centers around moderate to high doses of corticosteroids. Based on IPS experimental modes, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α has been implicated as an important mediator. Unfortunately, several studies evaluating etanercept have produced conflicting results, and this agent’s clinical effects on morbidity and mortality remain in question.76

- What treatment should be offered to the patient with diffuse alveolar damage on biopsy?

Treatment consists of supportive care and empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics with consideration of high-dose corticosteroids. Based upon early studies in murine models implicating TNF, pilot studies were performed evaluating etanercept as a possible safe and effective addition to high-dose systemic corticosteroids.77 Although these results were promising, data from a truncated randomized control clinical trial failed to show improvement in patient response in the adult population.76 More recent data from the same author suggests that pediatric populations with IPS are, however, responsive to etanercept and high-dose corticosteroid therapy.78 When IPS develops as a late complication, treatment with high-dose corticosteroids (2 mg/kg/day) and etanercept (0.4 mg/kg twice weekly) has been shown to improve 2-year survival.79

Case Patient 2 Conclusion

The patient is started on steroids and makes a speedy recovery. He is successfully extubated 5 days later.

Conclusion

Careful pretransplant evaluation, including a full set of pulmonary function tests, can help predict a patient’s risk for pulmonary complications after transplant, allowing risk factor modification strategies to be implemented prior to transplant, including smoking cessation. It also helps identify patients at high risk for complications who will require closer monitoring after transplantation. Early posttransplant complications include infectious and noninfectious entities. Bacterial, viral, and fungal pneumonias are in the differential of infectious pneumonia, and bronchoscopy can be helpful in establishing a diagnosis. A common, important noninfectious cause of early pulmonary complications is IPS, which is treated with steroids and sometimes anti-TNF therapy.

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is widely used in the economically developed world to treat a variety of hematologic malignancies as well as nonmalignant diseases and solid tumors. An estimated 17,900 HSCTs were performed in 2011, and survival rates continue to increase.1 Pulmonary complications post HSCT are common, with rates ranging from 40% to 60%, and are associated with increased morbidity and mortality.2

Clinical diagnosis of pulmonary complications in the HSCT population has been aided by a previously well-defined chronology of the most common diseases.3 Historically, early pulmonary complications were defined as pulmonary complications occurring within 100 days of HSCT (corresponding to the acute graft-versus-host disease [GVHD] period). Late pulmonary complications are those that occur thereafter. This timeline, however, is now more variable given the increasing indications for HSCT, the use of reduced-intensity conditioning strategies, and varied individual immune reconstitution. This article discusses the management of early post-HSCT pulmonary complications; late post-HSCT pulmonary complications will be discussed in a separate follow-up article.

Transplant Basics

The development of pulmonary complications is affected by many factors associated with the transplant. Autologous transplantation involves the collection of a patient’s own stem cells, appropriate storage and processing, and re-implantation after induction therapy. During induction therapy, the patient undergoes high-dose chemotherapy or radiation therapy that ablates the bone marrow. The stem cells are then transfused back into the patient to repopulate the bone marrow. Allogeneic transplants involve the collection of stem cells from a donor. Donors are matched as closely as possible to the recipient’s histocompatibility antigen (HLA) haplotypes to prevent graft failure and rejection. The donor can be related or unrelated to the recipient. If there is not a possibility of a related match (from a sibling), then a national search is undertaken to look for a match through the National Marrow Donor Program. There are fewer transplant reactions and occurrences of GVHD if the major HLAs of the donor and recipient match. Table 1 reviews basic definitions pertaining to HSCT.