User login

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is increasingly being used to treat hematologic malignancies as well as nonmalignant diseases and solid tumors. Over the past 2 decades overall survival following transplant and transplant-related mortality have improved.1 With this increased survival, there is a need to focus on late complications after transplantation. Pulmonary complications are a common but sometimes underrecognized cause of late morbidity and mortality in HSCT patients. This article, the second of 2 articles on post-HSCT pulmonary complications, reviews late-onset complications, with a focus on the evaluation and treatment of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS), one of the most common and serious late pulmonary complications in HSCT patients. The first article reviewed the management of early-onset pulmonary complications and included a basic overview of stem cell transplantation, discussion of factors associated with pulmonary complications, and a review of methods for assessing pretransplant risk for pulmonary complications in patients undergoing HSCT.2

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old white woman with a history of acute myeloid leukemia status post peripheral blood stem cell transplant presents with dyspnea on exertion, which she states started about 1 month ago and now is limiting her with even 1 flight of stairs. She also complains of mild dry cough and a 4- to 5-lb weight loss over the past 1 to 2 months. She has an occasional runny nose, but denies gastroesophageal reflux, fevers, chills, or night sweats. She has a history of matched related sibling donor transplant with busulfan and cyclophosphamide conditioning 1 year prior to presentation. She has had significant graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), affecting the liver, gastrointestinal tract, skin, and eyes.

On physical examination, heart rate is 110 beats/min, respiratory rate is 16 breaths/min, blood pressure is 92/58 mm Hg, and the patient is afebrile. Eye exam reveals scleral injection, mouth shows dry mucous membranes with a few white plaques, and the skin has chronic changes with a rash over both arms. Cardiac exam reveals tachycardia but regular rhythm and there are no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. Lungs are clear bilaterally and abdomen shows no organomegaly.

Laboratory exam shows a white blood cell count of 7800 cells/μL, hemoglobin level of 12.4 g/dL, and platelet count of 186 × 103/μL. Liver enzymes are mildly elevated. Chest radiograph shows clear lung fields bilaterally.

- What is the differential in this patient with dyspnea 1 year after transplantation?

Late pulmonary complications are generally accepted as those occurring more than 100 days post transplant. This period of time is characterized by chronic GVHD and impaired cellular and humoral immunity. Results of longitudinal studies of infections in adult HSCT patients suggest that special attention should be paid to allogeneic HSCT recipients for post-engraftment infectious pulmonary complications.3 Encapsulated bacteria such as Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae are the most frequent bacterial organisms causing late infectious pulmonary complications. Nontuberculous mycobacteria and Nocardia should also be considered. Depending upon geographic location, social and occupational risk factors, and prevalence, tuberculosis should also enter the differential.

There are many noninfectious late-onset pulmonary complications after HSCT. Unfortunately, the literature has divided pulmonary complications after HSCT using a range of criteria and classifications based upon timing, predominant pulmonary function test (PFT) findings, and etiology. These include early versus late, obstructive versus restrictive, and infectious versus noninfectious, which makes a comprehensive literature review of late pulmonary complications difficult. The most common noninfectious late-onset complications are bronchiolitis obliterans, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (previously referred to as bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia, or BOOP), and interstitial pneumonia. Other rarely reported complications include eosinophilic pneumonia, pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, air leak syndrome, and pulmonary hypertension.

Case Continued

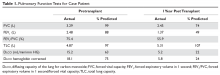

Because the patient does not have symptoms of infection, PFTs are obtained. Pretransplant PFTs and current PFTs are shown in Table 1.

- What is the diagnosis in this case?

Bronchiolitis Obliterans

BOS is one of the most common and most serious late-onset pulmonary diseases after allogeneic transplantation. It is considered the pulmonary form of chronic GVHD. BOS was first described in 1982 in patients with chronic GVHD after bone marrow transplantation.4 Many differing definitions of bronchiolitis obliterans have been described in the literature. A recent review of the topic cites 10 different published sets of criteria for the diagnosis of bronchiolitis obliterans.5 Traditionally, bronchiolitis obliterans was thought to occur in 2% to 8% of patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT, but these findings were from older studies that used a diagnosis based on very specific pathology findings. When more liberal diagnostic criteria are used, the incidence may be as high as 26% of allogeneic HSCT patients.6

Bronchiolitis obliterans is a progressive lung disease characterized by narrowing of the terminal airways and obliteration of the terminal bronchi. Pathology may show constrictive bronchiolitis but can also show lymphocytic bronchiolitis, which may be associated with a better outcome.7 As noted, bronchiolitis obliterans has traditionally been considered a pathologic diagnosis. Current diagnostic criteria have evolved based upon the difficulty in obtaining this diagnosis through transbronchial biopsy given the patchy nature of the disease.8 The gold standard of open lung biopsy is seldom pursued in the post-HSCT population as the procedure continues to carry a worrisome risk-benefit profile.

The 2005 National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic GVHD developed a clinical strategy for diagnosing BOS using the following criteria: absence of active infection, decreased forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) < 75%, FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio of < 70%, and evidence of air trapping on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) or PFTs (residual volume > 120%). These diagnostic criteria were applied to a small series of patients with clinically identified bronchiolitis obliterans or biopsy-proven bronchiolitis obliterans. Only 18% of these patients met the requirements for the NIH consensus definition.5 A 2011 study that applied the NIH criteria found an overall prevalence of 5.5% among all transplant recipients but a prevalence of 14% in patients with GVHD.9 In 2014, the NIH consensus development group updated their recommendations. The new criteria for diagnosis of BOS require the presence of airflow obstruction (FEV1/FVC < 70% or 5th percentile of predicted), FEV1 < 75% predicted with a ≥ 10% decline in fewer than 2 years, absence of infection, and presence of air trapping (by expiratory computed tomography [CT] scan or PFT with residual volume >120% predicted) (Table 2).

Some issues must be considered when determining airflow obstruction. The 2005 NIH working group recommends using Crapo as the reference set,11 but the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III reference values are the preferred reference set at this time12 and should be used in the United States. A recent article showed that the NHANES values were superior to older reference sets (however, they did not use Crapo as the comparison), although this study used the lower limit of normal as compared with the fixed 70% ratio.13 The 2014 NIH consensus group does not recommend a specific reference set and recognizes an FEV1/FVC ratio of 70% or less than the lower limit of normal as the cutoff value for airflow obstruction.10

Another issue in PFT interpretation is the finding of a decrease in FEV1 and FVC and normal total lung capacity, which is termed a nonspecific pattern. This pattern has been reported to occur in 9% of all PFTs and usually is associated with obstructive lung disease or obesity.14 A 2013 study described the nonspecific pattern as a BOS subgroup occurring in up to 31% of bronchiolitis obliterans patients.15

- What are the radiographic findings of BOS?

Chest radiograph is often normal in BOS. As discussed, air trapping can be documented using HRCT, according to the NIH clinical definition of bronchiolitis obliterans.16 A study that explored findings and trends seen on HRCT in HSCT patients with BOS found that the syndrome in these patients is characterized by central airway dilatation.17 Expiratory airway trapping on HRCT is the main finding, and this is best demonstrated on HRCT during inspiratory and expiratory phases.18 Other findings are bronchial wall thickening, parenchymal hypoattenuation, bronchiectasis, and centrilobular nodules.19

Galbán and colleagues developed a new technique called parametric response mapping that uses CT scanners to quantify normal parenchyma, functional small airway disease, emphysema, and parenchymal disease as relative lung volumes.20 This technique can detect airflow obstruction and small airway disease and was found to be a good method for detecting BOS after HSCT. In their study of parametric response mapping, the authors found that functional small airway disease affecting 28% or more of the total lung was highly indicative of bronchiolitis obliterans.20

- What therapies are used to treat BOS?

Traditionally, BOS has been treated with systemic immunosuppression. The recommended treatment had been systemic steroids at approximately 1 mg/ kg. However, it is increasingly recognized that BOS responds poorly to systemic steroids, and systemic steroids may actually be harmful and associated with increased mortality.15,21 The chronic GVHD recommendations from 2005 recommend ancillary therapy with inhaled corticosteroids and pulmonary rehabilitation.11 The updated 2011 German consensus statement lays out a clear management strategy for mild and moderate-severe disease with monitoring recommendations.22 The 2014 NIH chronic GVHD working group recommends fluticasone, azithromycin, and montelukast (ie, the FAM protocol) for treating BOS.23 FAM therapy in BOS may help lower the systemic steroid dose.24,25 Montelukast is not considered a treatment mainstay for BOS after lung transplant, but there is a study showing possible benefit in chronic GVHD.26 An evaluation of the natural history of a cohort of BOS patients treated with FAM therapy showed a rapid decline of FEV1 in the 6 months prior to diagnosis and treatment of BOS and subsequent stabilization following diagnosis and treatment.27 The benefit of high-dose inhaled corticosteroids or the combination of inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta-agonists has been demonstrated in small studies, which showed that these agents stabilized FEV1 and avoided the untoward side effects of systemic corticosteroids.28–30

Macrolide antibiotics have been explored as a treatment for BOS post HSCT because pilot studies suggested that azithromycin improved or stabilized FEV1 in patients with BOS after lung transplant or HSCT.31–33 Other studies of azithromycin have not shown benefit in the HSCT population after 3 months of therapy.34 A recent meta-analysis could neither support or refute the benefit of azithromycin for BOS after HSCT.35 In the lung transplant population, a study showed that patients who were started on azithromycin after transplant and continued on it 3 times a week had improved FEV1; these patients also had a reduced rate of BOS and improved overall and BOS-free survival 2 years after transplant.36 However, these benefits of azithromycin have not been observed in patients after HSCT. In fact, the ALLOZITHRO trial was stopped early because prophylactic azithromycin started at the time of the conditioning regimen with HSCT was associated with increased hematologic disease relapse, a decrease in airflow-decline-free survival, and reduced 2-year survival.30

Azithromycin is believed to exert an effect by its anti-inflammatory properties and perhaps by decreasing lung neutrophilia (it may be most beneficial in the subset of patients with high neutrophilia on bronchoalveolar lavage [BAL]).30 Adverse effects of chronic azithromycin include QT prolongation, cardiac arrhythmia, hearing loss, and antibiotic-resistant organism colonization.37,38

Other therapies include pulmonary rehabilitation, which may improve health-related quality of life and 6-minute walk distance,39 extracorporeal photopheresis,40 immunosuppression with calcineurin inhibitors or mycophenolate mofetil,21,41 and lung transplantation.42–44 A study with imatinib for the treatment of lung disease in steroid-refractory GVHD has shown promising results, but further validation with larger clinical trials is required.45

Case Continued

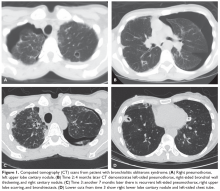

The patient is diagnosed with BOS and is treated for several months with prednisone 40 mg/day weaned over 3 months. She is started on inhaled corticosteroids, a proton pump inhibitor, and azithromycin 3 times per week, but she has a progressive decline in FEV1. She starts pulmonary rehabilitation but continues to functionally decline. Over the next year she develops bilateral pneumothoraces and bilateral cavitary nodules (Figure 1).

- What is causing this decline and the radiographic abnormalities?

Spontaneous air leak syndrome has been described in a little more than 1% of patients undergoing HSCT and has included pneumothorax and mediastinal and subcutaneous emphysema.46 It appears that air leak syndrome is more likely to occur in patients with chronic GVHD.47 The association between chronic GVHD and air leak syndrome could explain this patient’s recurrent pneumothoraces. The recurrent cavitary nodules are suspicious for infectious etiologies such as nontuberculous mycobacteria, tuberculosis, and fungal infections.

Case Continued

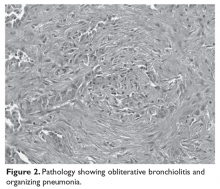

During an episode of pneumothorax, the patient undergoes chest tube placement, pleurodesis, and lung biopsy. Pathology reveals bronchiolitis obliterans as well as organizing pneumonia (Figure 2). No organisms are seen on acid-fast bacilli or GMS stains.

- What are the other late-onset noninfectious pulmonary complications?

Definitions of other late noninfectious pulmonary complications following HSCT are shown in Table 3.

Interstitial pneumonias may represent COP or may be idiopathic pneumonia syndrome with a later onset or a nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. This syndrome is poorly defined, with a number of differing definitions of the syndrome published in the literature.50–55

A rare pulmonary complication after HSCT is pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD). Pulmonary hypertension has been reported after HSCT,56 but PVOD is a subset of pulmonary hypertension. It is associated with pleural effusions and volume overload on chest radiography.57,58 It may present early or late after transplant and is poorly understood.

Besides obstructive and restrictive PFT abnormalities, changes in small airway function59 after transplant and loss in diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (D

Case Conclusion

The patient’s lung function continues to worsen, but no infectious etiologies are discovered. Ultimately, she dies of respiratory failure caused by progressive bronchiolitis obliterans.

Conclusion

Late pulmonary complications occur frequently in patients who have undergone HSCT. These complications can be classified as infectious versus noninfectious etiologies. Late-onset complications are more common in allogeneic transplantations because they are associated with chronic GVHD. These complications can be manifestations of pulmonary GHVD or can be infectious complications associated with prolonged immunosuppression. Appropriate monitoring for the development of BOS is essential. Early and aggressive treatment of respiratory infections and diagnostic bronchoscopy with BAL can help elucidate most infectious causes. Still, diagnostic challenges remain and multiple causes of respiratory deterioration can be present concurrently in the post-HSCT patient. Steroid therapy remains the mainstay treatment for most noninfectious pulmonary complications and should be strongly considered once infection is effectively ruled out.

1. Remberger M, Ackefors M, Berglund S, et al. Improved survival after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in recent years. A single-center study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2011;17:1688–97.

2. Wood KL, Esguerra VG. Management of late pulmonary complications after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Hosp Phys Hematology-Oncology Board Review Manual 2018;13(1):36–48.

3. Ninin E, Milpied N, Moreau P, et al. Longitudinal study of bacterial, viral, and fungal infections in adult recipients of bone marrow transplants. Clin Infect Dis 2001;33:41–7.

4. Roca J, Granena A, Rodriguez-Roisin R, et al. Fatal airway disease in an adult with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Thorax 1982;37:77–8.

5. Williams KM, Chien JW, Gladwin MT, Pavletic SZ. Bronchiolitis obliterans after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. JAMA 2009;302:306–14.

6. Chien JW, Martin PJ, Gooley TA, et al. Airflow obstruction after myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:208–14.

7. Holbro A, Lehmann T, Girsberger S, et al. Lung histology predicts outcome of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2013;19:973–80.

8. Chamberlain D, Maurer J, Chaparro C, Idolor L. Evaluation of transbronchial lung biopsy specimens in the diagnosis of bronchiolitis obliterans after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 1994;13:963–71.

9. Au BK, Au MA, Chien JW. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome epidemiology after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2011;17:1072–8.

10. Jagasia MH, Greinix HT, Arora M, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: I. The 2014 Diagnosis and Staging Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015;21:389–401.

11. Couriel D, Carpenter PA, Cutler C, et al. Ancillary therapy and supportive care of chronic graft-versus-host disease: national institutes of health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic Graft-versus-host disease: V. Ancillary Therapy and Supportive Care Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2006;12:375–96.

12. Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J 2005;26:948–68.

13. Williams KM, Hnatiuk O, Mitchell SA, et al. NHANES III equations enhance early detection and mortality prediction of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2014;49:561–6.

14. Hyatt RE, Cowl CT, Bjoraker JA, Scanlon PD. Conditions associated with an abnormal nonspecific pattern of pulmonary function tests. Chest 2009;135:419–24.

15. Bergeron A, Godet C, Chevret S, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic SCT: phenotypes and prognosis. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013;48:819–24.

16. Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2005;11:945–56.

17. Gazourian L, Coronata AM, Rogers AJ, et al. Airway dilation in bronchiolitis obliterans after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Respir Med 2013;107:276–83.

18. Gunn ML, Godwin JD, Kanne JP, et al. High-resolution CT findings of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Thorac Imaging 2008;23:244–50.

19. Sargent MA, Cairns RA, Murdoch MJ, et al. Obstructive lung disease in children after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: evaluation with high-resolution CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995;164:693–6.

20. Galban CJ, Boes JL, Bule M, et al. Parametric response mapping as an indicator of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2014;20:1592–8.

21. Meyer KC, Raghu G, Verleden GM, et al. An international ISHLT/ATS/ERS clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and management of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1479–1503.

22. Hildebrandt GC, Fazekas T, Lawitschka A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary chronic GVHD: report from the consensus conference on clinical practice in chronic GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011;46:1283–95.

23. Carpenter PA, Kitko CL, Elad S, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: V. The 2014 Ancillary Therapy and Supportive Care Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015;21:1167–87.

24. Norman BC, Jacobsohn DA, Williams KM, et al. Fluticasone, azithromycin and montelukast therapy in reducing corticosteroid exposure in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic SCT: a case series of eight patients. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011;46:1369–73.

25. Williams KM, Cheng GS, Pusic I, et al. Fluticasone, azithromycin, and montelukast treatment for new-onset bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2016;22:710–6.

26. Or R, Gesundheit B, Resnick I, et al. Sparing effect by montelukast treatment for chronic graft versus host disease: a pilot study. Transplantation 2007;83:577–81.

27. Cheng GS, Storer B, Chien JW, et al. Lung function trajectory in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016;13:1932–9.

28. Bergeron A, Belle A, Chevret S, et al. Combined inhaled steroids and bronchodilatators in obstructive airway disease after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2007;39:547–53.

29. Bashoura L, Gupta S, Jain A, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids stabilize constrictive bronchiolitis after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2008;41:63–7.

30. Bergeron A, Chevret S, Granata A, et al. Effect of azithromycin on airflow decline-free survival after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant: the ALLOZITHRO randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;318:557–66.

31. Gerhardt SG, McDyer JF, Girgis RE, et al. Maintenance azithromycin therapy for bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome: results of a pilot study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:121–5.

32. Khalid M, Al Saghir A, Saleemi S, et al. Azithromycin in bronchiolitis obliterans complicating bone marrow transplantation: a preliminary study. Eur Respir J 2005;25:490–3.

33. Maimon N, Lipton JH, Chan CK, Marras TK. Macrolides in the treatment of bronchiolitis obliterans in allograft recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant 2009;44:69–73.

34. Lam DC, Lam B, Wong MK, et al. Effects of azithromycin in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic SCT--a randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled study. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011;46:1551–6.

35. Yadav H, Peters SG, Keogh KA, et al. Azithromycin for the treatment of obliterative bronchiolitis after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2016;22:2264–9.

36. Vos R, Vanaudenaerde BM, Verleden SE, et al. A randomised controlled trial of azithromycin to prevent chronic rejection after lung transplantation. Eur Respir J 2011;37:164–72.

37. Svanstrom H, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of azithromycin and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1704–12.

38. Albert RK, Connett J, Bailey WC, et al. Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med 2011;365:689–98.

39. Tran J, Norder EE, Diaz PT, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2012;18:1250–4.

40. Lucid CE, Savani BN, Engelhardt BG, et al. Extracorporeal photopheresis in patients with refractory bronchiolitis obliterans developing after allo-SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011;46:426–9.

41. Hostettler KE, Halter JP, Gerull S, et al. Calcineurin inhibitors in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome following stem cell transplantation. Eur Respir J 2014;43:221–32.

42. Holm AM, Riise GC, Brinch L, et al. Lung transplantation for bronchiolitis obliterans after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: unresolved questions. Transplantation 2013;96:e21–22.

43. Cheng GS, Edelman JD, Madtes DK, et al. Outcomes of lung transplantation after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2014;20:1169–75.

44. Okumura H, Ohtake S, Ontachi Y, et al. Living-donor lobar lung transplantation for broncho-bronchiolitis obliterans after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: does bronchiolitis obliterans recur in transplanted lungs? Int J Hematol 2007;86:369–73.

45. Olivieri A, Cimminiello M, Corradini P, et al. Long-term outcome and prospective validation of NIH response criteria in 39 patients receiving imatinib for steroid-refractory chronic GVHD. Blood 2013;122:4111–8.

46. Rahmanian S, Wood KL. Bronchiolitis obliterans and the risk of pneumothorax after transbronchial biopsy. Respiratory Medicine CME 2010;3:87–9.

47. Sakai R, Kanamori H, Nakaseko C, et al. Air-leak syndrome following allo-SCT in adult patients: report from the Kanto Study Group for Cell Therapy in Japan. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011;46:379–84.

48. Visscher DW, Myers JL. Histologic spectrum of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:322–9.

49. Cordier JF. Cryptogenic organising pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2006;28:422–46.

50. Nishio N, Yagasaki H, Takahashi Y, et al. Late-onset non-infectious pulmonary complications following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children. Bone Marrow Transplant 2009;44:303–8.

51. Ueda K, Watadani T, Maeda E, et al. Outcome and treatment of late-onset noninfectious pulmonary complications after allogeneic haematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2010;45:1719–27.

52. Schlemmer F, Chevret S, Lorillon G, et al. Late-onset noninfectious interstitial lung disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Respir Med 2014;108:1525–33.

53. Palmas A, Tefferi A, Myers JL, et al. Late-onset noninfectious pulmonary complications after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Br J Haematol 1998;100:680–7.

54. Sakaida E, Nakaseko C, Harima A, et al. Late-onset noninfectious pulmonary complications after allogeneic stem cell transplantation are significantly associated with chronic graft-versus-host disease and with the graft-versus-leukemia effect. Blood 2003;102:4236–42.

55. Solh M, Arat M, Cao Q, et al. Late-onset noninfectious pulmonary complications in adult allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Transplantation 2011;91:798–803.

56. Dandoy CE, Hirsch R, Chima R, et al. Pulmonary hypertension after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2013;19:1546–56.

57. Bunte MC, Patnaik MM, Pritzker MR, Burns LJ. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a rare model of endothelial dysfunction. Bone Marrow Transplant 2008;41:677–86.

58. Troussard X, Bernaudin JF, Cordonnier C, et al. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease after bone marrow transplantation. Thorax 1984;39:956–7.

59. Lahzami S, Schoeffel RE, Pechey V, et al. Small airways function declines after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Eur Respir J 2011;38:1180–8.

60. Jain NA, Pophali PA, Klotz JK, et al. Repair of impaired pulmonary function is possible in very-long-term allogeneic stem cell transplantation survivors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2014;20:209–13.

61. Barisione G, Bacigalupo A, Crimi E, et al. Changes in lung volumes and airway responsiveness following haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Eur Respir J 2008;32:1576–82.

62. Kovalszki A, Schumaker GL, Klein A, et al. Reduced respiratory and skeletal muscle strength in survivors of sibling or unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2008;41:965–9.

63. Mathiesen S, Uhlving HH, Buchvald F, et al. Aerobic exercise capacity at long-term follow-up after paediatric allogeneic haematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2014;49:1393–9.

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is increasingly being used to treat hematologic malignancies as well as nonmalignant diseases and solid tumors. Over the past 2 decades overall survival following transplant and transplant-related mortality have improved.1 With this increased survival, there is a need to focus on late complications after transplantation. Pulmonary complications are a common but sometimes underrecognized cause of late morbidity and mortality in HSCT patients. This article, the second of 2 articles on post-HSCT pulmonary complications, reviews late-onset complications, with a focus on the evaluation and treatment of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS), one of the most common and serious late pulmonary complications in HSCT patients. The first article reviewed the management of early-onset pulmonary complications and included a basic overview of stem cell transplantation, discussion of factors associated with pulmonary complications, and a review of methods for assessing pretransplant risk for pulmonary complications in patients undergoing HSCT.2

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old white woman with a history of acute myeloid leukemia status post peripheral blood stem cell transplant presents with dyspnea on exertion, which she states started about 1 month ago and now is limiting her with even 1 flight of stairs. She also complains of mild dry cough and a 4- to 5-lb weight loss over the past 1 to 2 months. She has an occasional runny nose, but denies gastroesophageal reflux, fevers, chills, or night sweats. She has a history of matched related sibling donor transplant with busulfan and cyclophosphamide conditioning 1 year prior to presentation. She has had significant graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), affecting the liver, gastrointestinal tract, skin, and eyes.

On physical examination, heart rate is 110 beats/min, respiratory rate is 16 breaths/min, blood pressure is 92/58 mm Hg, and the patient is afebrile. Eye exam reveals scleral injection, mouth shows dry mucous membranes with a few white plaques, and the skin has chronic changes with a rash over both arms. Cardiac exam reveals tachycardia but regular rhythm and there are no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. Lungs are clear bilaterally and abdomen shows no organomegaly.

Laboratory exam shows a white blood cell count of 7800 cells/μL, hemoglobin level of 12.4 g/dL, and platelet count of 186 × 103/μL. Liver enzymes are mildly elevated. Chest radiograph shows clear lung fields bilaterally.

- What is the differential in this patient with dyspnea 1 year after transplantation?

Late pulmonary complications are generally accepted as those occurring more than 100 days post transplant. This period of time is characterized by chronic GVHD and impaired cellular and humoral immunity. Results of longitudinal studies of infections in adult HSCT patients suggest that special attention should be paid to allogeneic HSCT recipients for post-engraftment infectious pulmonary complications.3 Encapsulated bacteria such as Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae are the most frequent bacterial organisms causing late infectious pulmonary complications. Nontuberculous mycobacteria and Nocardia should also be considered. Depending upon geographic location, social and occupational risk factors, and prevalence, tuberculosis should also enter the differential.

There are many noninfectious late-onset pulmonary complications after HSCT. Unfortunately, the literature has divided pulmonary complications after HSCT using a range of criteria and classifications based upon timing, predominant pulmonary function test (PFT) findings, and etiology. These include early versus late, obstructive versus restrictive, and infectious versus noninfectious, which makes a comprehensive literature review of late pulmonary complications difficult. The most common noninfectious late-onset complications are bronchiolitis obliterans, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (previously referred to as bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia, or BOOP), and interstitial pneumonia. Other rarely reported complications include eosinophilic pneumonia, pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, air leak syndrome, and pulmonary hypertension.

Case Continued

Because the patient does not have symptoms of infection, PFTs are obtained. Pretransplant PFTs and current PFTs are shown in Table 1.

- What is the diagnosis in this case?

Bronchiolitis Obliterans

BOS is one of the most common and most serious late-onset pulmonary diseases after allogeneic transplantation. It is considered the pulmonary form of chronic GVHD. BOS was first described in 1982 in patients with chronic GVHD after bone marrow transplantation.4 Many differing definitions of bronchiolitis obliterans have been described in the literature. A recent review of the topic cites 10 different published sets of criteria for the diagnosis of bronchiolitis obliterans.5 Traditionally, bronchiolitis obliterans was thought to occur in 2% to 8% of patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT, but these findings were from older studies that used a diagnosis based on very specific pathology findings. When more liberal diagnostic criteria are used, the incidence may be as high as 26% of allogeneic HSCT patients.6

Bronchiolitis obliterans is a progressive lung disease characterized by narrowing of the terminal airways and obliteration of the terminal bronchi. Pathology may show constrictive bronchiolitis but can also show lymphocytic bronchiolitis, which may be associated with a better outcome.7 As noted, bronchiolitis obliterans has traditionally been considered a pathologic diagnosis. Current diagnostic criteria have evolved based upon the difficulty in obtaining this diagnosis through transbronchial biopsy given the patchy nature of the disease.8 The gold standard of open lung biopsy is seldom pursued in the post-HSCT population as the procedure continues to carry a worrisome risk-benefit profile.

The 2005 National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic GVHD developed a clinical strategy for diagnosing BOS using the following criteria: absence of active infection, decreased forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) < 75%, FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio of < 70%, and evidence of air trapping on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) or PFTs (residual volume > 120%). These diagnostic criteria were applied to a small series of patients with clinically identified bronchiolitis obliterans or biopsy-proven bronchiolitis obliterans. Only 18% of these patients met the requirements for the NIH consensus definition.5 A 2011 study that applied the NIH criteria found an overall prevalence of 5.5% among all transplant recipients but a prevalence of 14% in patients with GVHD.9 In 2014, the NIH consensus development group updated their recommendations. The new criteria for diagnosis of BOS require the presence of airflow obstruction (FEV1/FVC < 70% or 5th percentile of predicted), FEV1 < 75% predicted with a ≥ 10% decline in fewer than 2 years, absence of infection, and presence of air trapping (by expiratory computed tomography [CT] scan or PFT with residual volume >120% predicted) (Table 2).

Some issues must be considered when determining airflow obstruction. The 2005 NIH working group recommends using Crapo as the reference set,11 but the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III reference values are the preferred reference set at this time12 and should be used in the United States. A recent article showed that the NHANES values were superior to older reference sets (however, they did not use Crapo as the comparison), although this study used the lower limit of normal as compared with the fixed 70% ratio.13 The 2014 NIH consensus group does not recommend a specific reference set and recognizes an FEV1/FVC ratio of 70% or less than the lower limit of normal as the cutoff value for airflow obstruction.10

Another issue in PFT interpretation is the finding of a decrease in FEV1 and FVC and normal total lung capacity, which is termed a nonspecific pattern. This pattern has been reported to occur in 9% of all PFTs and usually is associated with obstructive lung disease or obesity.14 A 2013 study described the nonspecific pattern as a BOS subgroup occurring in up to 31% of bronchiolitis obliterans patients.15

- What are the radiographic findings of BOS?

Chest radiograph is often normal in BOS. As discussed, air trapping can be documented using HRCT, according to the NIH clinical definition of bronchiolitis obliterans.16 A study that explored findings and trends seen on HRCT in HSCT patients with BOS found that the syndrome in these patients is characterized by central airway dilatation.17 Expiratory airway trapping on HRCT is the main finding, and this is best demonstrated on HRCT during inspiratory and expiratory phases.18 Other findings are bronchial wall thickening, parenchymal hypoattenuation, bronchiectasis, and centrilobular nodules.19

Galbán and colleagues developed a new technique called parametric response mapping that uses CT scanners to quantify normal parenchyma, functional small airway disease, emphysema, and parenchymal disease as relative lung volumes.20 This technique can detect airflow obstruction and small airway disease and was found to be a good method for detecting BOS after HSCT. In their study of parametric response mapping, the authors found that functional small airway disease affecting 28% or more of the total lung was highly indicative of bronchiolitis obliterans.20

- What therapies are used to treat BOS?

Traditionally, BOS has been treated with systemic immunosuppression. The recommended treatment had been systemic steroids at approximately 1 mg/ kg. However, it is increasingly recognized that BOS responds poorly to systemic steroids, and systemic steroids may actually be harmful and associated with increased mortality.15,21 The chronic GVHD recommendations from 2005 recommend ancillary therapy with inhaled corticosteroids and pulmonary rehabilitation.11 The updated 2011 German consensus statement lays out a clear management strategy for mild and moderate-severe disease with monitoring recommendations.22 The 2014 NIH chronic GVHD working group recommends fluticasone, azithromycin, and montelukast (ie, the FAM protocol) for treating BOS.23 FAM therapy in BOS may help lower the systemic steroid dose.24,25 Montelukast is not considered a treatment mainstay for BOS after lung transplant, but there is a study showing possible benefit in chronic GVHD.26 An evaluation of the natural history of a cohort of BOS patients treated with FAM therapy showed a rapid decline of FEV1 in the 6 months prior to diagnosis and treatment of BOS and subsequent stabilization following diagnosis and treatment.27 The benefit of high-dose inhaled corticosteroids or the combination of inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta-agonists has been demonstrated in small studies, which showed that these agents stabilized FEV1 and avoided the untoward side effects of systemic corticosteroids.28–30

Macrolide antibiotics have been explored as a treatment for BOS post HSCT because pilot studies suggested that azithromycin improved or stabilized FEV1 in patients with BOS after lung transplant or HSCT.31–33 Other studies of azithromycin have not shown benefit in the HSCT population after 3 months of therapy.34 A recent meta-analysis could neither support or refute the benefit of azithromycin for BOS after HSCT.35 In the lung transplant population, a study showed that patients who were started on azithromycin after transplant and continued on it 3 times a week had improved FEV1; these patients also had a reduced rate of BOS and improved overall and BOS-free survival 2 years after transplant.36 However, these benefits of azithromycin have not been observed in patients after HSCT. In fact, the ALLOZITHRO trial was stopped early because prophylactic azithromycin started at the time of the conditioning regimen with HSCT was associated with increased hematologic disease relapse, a decrease in airflow-decline-free survival, and reduced 2-year survival.30

Azithromycin is believed to exert an effect by its anti-inflammatory properties and perhaps by decreasing lung neutrophilia (it may be most beneficial in the subset of patients with high neutrophilia on bronchoalveolar lavage [BAL]).30 Adverse effects of chronic azithromycin include QT prolongation, cardiac arrhythmia, hearing loss, and antibiotic-resistant organism colonization.37,38

Other therapies include pulmonary rehabilitation, which may improve health-related quality of life and 6-minute walk distance,39 extracorporeal photopheresis,40 immunosuppression with calcineurin inhibitors or mycophenolate mofetil,21,41 and lung transplantation.42–44 A study with imatinib for the treatment of lung disease in steroid-refractory GVHD has shown promising results, but further validation with larger clinical trials is required.45

Case Continued

The patient is diagnosed with BOS and is treated for several months with prednisone 40 mg/day weaned over 3 months. She is started on inhaled corticosteroids, a proton pump inhibitor, and azithromycin 3 times per week, but she has a progressive decline in FEV1. She starts pulmonary rehabilitation but continues to functionally decline. Over the next year she develops bilateral pneumothoraces and bilateral cavitary nodules (Figure 1).

- What is causing this decline and the radiographic abnormalities?

Spontaneous air leak syndrome has been described in a little more than 1% of patients undergoing HSCT and has included pneumothorax and mediastinal and subcutaneous emphysema.46 It appears that air leak syndrome is more likely to occur in patients with chronic GVHD.47 The association between chronic GVHD and air leak syndrome could explain this patient’s recurrent pneumothoraces. The recurrent cavitary nodules are suspicious for infectious etiologies such as nontuberculous mycobacteria, tuberculosis, and fungal infections.

Case Continued

During an episode of pneumothorax, the patient undergoes chest tube placement, pleurodesis, and lung biopsy. Pathology reveals bronchiolitis obliterans as well as organizing pneumonia (Figure 2). No organisms are seen on acid-fast bacilli or GMS stains.

- What are the other late-onset noninfectious pulmonary complications?

Definitions of other late noninfectious pulmonary complications following HSCT are shown in Table 3.

Interstitial pneumonias may represent COP or may be idiopathic pneumonia syndrome with a later onset or a nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. This syndrome is poorly defined, with a number of differing definitions of the syndrome published in the literature.50–55

A rare pulmonary complication after HSCT is pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD). Pulmonary hypertension has been reported after HSCT,56 but PVOD is a subset of pulmonary hypertension. It is associated with pleural effusions and volume overload on chest radiography.57,58 It may present early or late after transplant and is poorly understood.

Besides obstructive and restrictive PFT abnormalities, changes in small airway function59 after transplant and loss in diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (D

Case Conclusion

The patient’s lung function continues to worsen, but no infectious etiologies are discovered. Ultimately, she dies of respiratory failure caused by progressive bronchiolitis obliterans.

Conclusion

Late pulmonary complications occur frequently in patients who have undergone HSCT. These complications can be classified as infectious versus noninfectious etiologies. Late-onset complications are more common in allogeneic transplantations because they are associated with chronic GVHD. These complications can be manifestations of pulmonary GHVD or can be infectious complications associated with prolonged immunosuppression. Appropriate monitoring for the development of BOS is essential. Early and aggressive treatment of respiratory infections and diagnostic bronchoscopy with BAL can help elucidate most infectious causes. Still, diagnostic challenges remain and multiple causes of respiratory deterioration can be present concurrently in the post-HSCT patient. Steroid therapy remains the mainstay treatment for most noninfectious pulmonary complications and should be strongly considered once infection is effectively ruled out.

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is increasingly being used to treat hematologic malignancies as well as nonmalignant diseases and solid tumors. Over the past 2 decades overall survival following transplant and transplant-related mortality have improved.1 With this increased survival, there is a need to focus on late complications after transplantation. Pulmonary complications are a common but sometimes underrecognized cause of late morbidity and mortality in HSCT patients. This article, the second of 2 articles on post-HSCT pulmonary complications, reviews late-onset complications, with a focus on the evaluation and treatment of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS), one of the most common and serious late pulmonary complications in HSCT patients. The first article reviewed the management of early-onset pulmonary complications and included a basic overview of stem cell transplantation, discussion of factors associated with pulmonary complications, and a review of methods for assessing pretransplant risk for pulmonary complications in patients undergoing HSCT.2

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old white woman with a history of acute myeloid leukemia status post peripheral blood stem cell transplant presents with dyspnea on exertion, which she states started about 1 month ago and now is limiting her with even 1 flight of stairs. She also complains of mild dry cough and a 4- to 5-lb weight loss over the past 1 to 2 months. She has an occasional runny nose, but denies gastroesophageal reflux, fevers, chills, or night sweats. She has a history of matched related sibling donor transplant with busulfan and cyclophosphamide conditioning 1 year prior to presentation. She has had significant graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), affecting the liver, gastrointestinal tract, skin, and eyes.

On physical examination, heart rate is 110 beats/min, respiratory rate is 16 breaths/min, blood pressure is 92/58 mm Hg, and the patient is afebrile. Eye exam reveals scleral injection, mouth shows dry mucous membranes with a few white plaques, and the skin has chronic changes with a rash over both arms. Cardiac exam reveals tachycardia but regular rhythm and there are no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. Lungs are clear bilaterally and abdomen shows no organomegaly.

Laboratory exam shows a white blood cell count of 7800 cells/μL, hemoglobin level of 12.4 g/dL, and platelet count of 186 × 103/μL. Liver enzymes are mildly elevated. Chest radiograph shows clear lung fields bilaterally.

- What is the differential in this patient with dyspnea 1 year after transplantation?

Late pulmonary complications are generally accepted as those occurring more than 100 days post transplant. This period of time is characterized by chronic GVHD and impaired cellular and humoral immunity. Results of longitudinal studies of infections in adult HSCT patients suggest that special attention should be paid to allogeneic HSCT recipients for post-engraftment infectious pulmonary complications.3 Encapsulated bacteria such as Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae are the most frequent bacterial organisms causing late infectious pulmonary complications. Nontuberculous mycobacteria and Nocardia should also be considered. Depending upon geographic location, social and occupational risk factors, and prevalence, tuberculosis should also enter the differential.

There are many noninfectious late-onset pulmonary complications after HSCT. Unfortunately, the literature has divided pulmonary complications after HSCT using a range of criteria and classifications based upon timing, predominant pulmonary function test (PFT) findings, and etiology. These include early versus late, obstructive versus restrictive, and infectious versus noninfectious, which makes a comprehensive literature review of late pulmonary complications difficult. The most common noninfectious late-onset complications are bronchiolitis obliterans, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (previously referred to as bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia, or BOOP), and interstitial pneumonia. Other rarely reported complications include eosinophilic pneumonia, pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, air leak syndrome, and pulmonary hypertension.

Case Continued

Because the patient does not have symptoms of infection, PFTs are obtained. Pretransplant PFTs and current PFTs are shown in Table 1.

- What is the diagnosis in this case?

Bronchiolitis Obliterans

BOS is one of the most common and most serious late-onset pulmonary diseases after allogeneic transplantation. It is considered the pulmonary form of chronic GVHD. BOS was first described in 1982 in patients with chronic GVHD after bone marrow transplantation.4 Many differing definitions of bronchiolitis obliterans have been described in the literature. A recent review of the topic cites 10 different published sets of criteria for the diagnosis of bronchiolitis obliterans.5 Traditionally, bronchiolitis obliterans was thought to occur in 2% to 8% of patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT, but these findings were from older studies that used a diagnosis based on very specific pathology findings. When more liberal diagnostic criteria are used, the incidence may be as high as 26% of allogeneic HSCT patients.6

Bronchiolitis obliterans is a progressive lung disease characterized by narrowing of the terminal airways and obliteration of the terminal bronchi. Pathology may show constrictive bronchiolitis but can also show lymphocytic bronchiolitis, which may be associated with a better outcome.7 As noted, bronchiolitis obliterans has traditionally been considered a pathologic diagnosis. Current diagnostic criteria have evolved based upon the difficulty in obtaining this diagnosis through transbronchial biopsy given the patchy nature of the disease.8 The gold standard of open lung biopsy is seldom pursued in the post-HSCT population as the procedure continues to carry a worrisome risk-benefit profile.

The 2005 National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic GVHD developed a clinical strategy for diagnosing BOS using the following criteria: absence of active infection, decreased forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) < 75%, FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio of < 70%, and evidence of air trapping on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) or PFTs (residual volume > 120%). These diagnostic criteria were applied to a small series of patients with clinically identified bronchiolitis obliterans or biopsy-proven bronchiolitis obliterans. Only 18% of these patients met the requirements for the NIH consensus definition.5 A 2011 study that applied the NIH criteria found an overall prevalence of 5.5% among all transplant recipients but a prevalence of 14% in patients with GVHD.9 In 2014, the NIH consensus development group updated their recommendations. The new criteria for diagnosis of BOS require the presence of airflow obstruction (FEV1/FVC < 70% or 5th percentile of predicted), FEV1 < 75% predicted with a ≥ 10% decline in fewer than 2 years, absence of infection, and presence of air trapping (by expiratory computed tomography [CT] scan or PFT with residual volume >120% predicted) (Table 2).

Some issues must be considered when determining airflow obstruction. The 2005 NIH working group recommends using Crapo as the reference set,11 but the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III reference values are the preferred reference set at this time12 and should be used in the United States. A recent article showed that the NHANES values were superior to older reference sets (however, they did not use Crapo as the comparison), although this study used the lower limit of normal as compared with the fixed 70% ratio.13 The 2014 NIH consensus group does not recommend a specific reference set and recognizes an FEV1/FVC ratio of 70% or less than the lower limit of normal as the cutoff value for airflow obstruction.10

Another issue in PFT interpretation is the finding of a decrease in FEV1 and FVC and normal total lung capacity, which is termed a nonspecific pattern. This pattern has been reported to occur in 9% of all PFTs and usually is associated with obstructive lung disease or obesity.14 A 2013 study described the nonspecific pattern as a BOS subgroup occurring in up to 31% of bronchiolitis obliterans patients.15

- What are the radiographic findings of BOS?

Chest radiograph is often normal in BOS. As discussed, air trapping can be documented using HRCT, according to the NIH clinical definition of bronchiolitis obliterans.16 A study that explored findings and trends seen on HRCT in HSCT patients with BOS found that the syndrome in these patients is characterized by central airway dilatation.17 Expiratory airway trapping on HRCT is the main finding, and this is best demonstrated on HRCT during inspiratory and expiratory phases.18 Other findings are bronchial wall thickening, parenchymal hypoattenuation, bronchiectasis, and centrilobular nodules.19

Galbán and colleagues developed a new technique called parametric response mapping that uses CT scanners to quantify normal parenchyma, functional small airway disease, emphysema, and parenchymal disease as relative lung volumes.20 This technique can detect airflow obstruction and small airway disease and was found to be a good method for detecting BOS after HSCT. In their study of parametric response mapping, the authors found that functional small airway disease affecting 28% or more of the total lung was highly indicative of bronchiolitis obliterans.20

- What therapies are used to treat BOS?

Traditionally, BOS has been treated with systemic immunosuppression. The recommended treatment had been systemic steroids at approximately 1 mg/ kg. However, it is increasingly recognized that BOS responds poorly to systemic steroids, and systemic steroids may actually be harmful and associated with increased mortality.15,21 The chronic GVHD recommendations from 2005 recommend ancillary therapy with inhaled corticosteroids and pulmonary rehabilitation.11 The updated 2011 German consensus statement lays out a clear management strategy for mild and moderate-severe disease with monitoring recommendations.22 The 2014 NIH chronic GVHD working group recommends fluticasone, azithromycin, and montelukast (ie, the FAM protocol) for treating BOS.23 FAM therapy in BOS may help lower the systemic steroid dose.24,25 Montelukast is not considered a treatment mainstay for BOS after lung transplant, but there is a study showing possible benefit in chronic GVHD.26 An evaluation of the natural history of a cohort of BOS patients treated with FAM therapy showed a rapid decline of FEV1 in the 6 months prior to diagnosis and treatment of BOS and subsequent stabilization following diagnosis and treatment.27 The benefit of high-dose inhaled corticosteroids or the combination of inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta-agonists has been demonstrated in small studies, which showed that these agents stabilized FEV1 and avoided the untoward side effects of systemic corticosteroids.28–30

Macrolide antibiotics have been explored as a treatment for BOS post HSCT because pilot studies suggested that azithromycin improved or stabilized FEV1 in patients with BOS after lung transplant or HSCT.31–33 Other studies of azithromycin have not shown benefit in the HSCT population after 3 months of therapy.34 A recent meta-analysis could neither support or refute the benefit of azithromycin for BOS after HSCT.35 In the lung transplant population, a study showed that patients who were started on azithromycin after transplant and continued on it 3 times a week had improved FEV1; these patients also had a reduced rate of BOS and improved overall and BOS-free survival 2 years after transplant.36 However, these benefits of azithromycin have not been observed in patients after HSCT. In fact, the ALLOZITHRO trial was stopped early because prophylactic azithromycin started at the time of the conditioning regimen with HSCT was associated with increased hematologic disease relapse, a decrease in airflow-decline-free survival, and reduced 2-year survival.30

Azithromycin is believed to exert an effect by its anti-inflammatory properties and perhaps by decreasing lung neutrophilia (it may be most beneficial in the subset of patients with high neutrophilia on bronchoalveolar lavage [BAL]).30 Adverse effects of chronic azithromycin include QT prolongation, cardiac arrhythmia, hearing loss, and antibiotic-resistant organism colonization.37,38

Other therapies include pulmonary rehabilitation, which may improve health-related quality of life and 6-minute walk distance,39 extracorporeal photopheresis,40 immunosuppression with calcineurin inhibitors or mycophenolate mofetil,21,41 and lung transplantation.42–44 A study with imatinib for the treatment of lung disease in steroid-refractory GVHD has shown promising results, but further validation with larger clinical trials is required.45

Case Continued

The patient is diagnosed with BOS and is treated for several months with prednisone 40 mg/day weaned over 3 months. She is started on inhaled corticosteroids, a proton pump inhibitor, and azithromycin 3 times per week, but she has a progressive decline in FEV1. She starts pulmonary rehabilitation but continues to functionally decline. Over the next year she develops bilateral pneumothoraces and bilateral cavitary nodules (Figure 1).

- What is causing this decline and the radiographic abnormalities?

Spontaneous air leak syndrome has been described in a little more than 1% of patients undergoing HSCT and has included pneumothorax and mediastinal and subcutaneous emphysema.46 It appears that air leak syndrome is more likely to occur in patients with chronic GVHD.47 The association between chronic GVHD and air leak syndrome could explain this patient’s recurrent pneumothoraces. The recurrent cavitary nodules are suspicious for infectious etiologies such as nontuberculous mycobacteria, tuberculosis, and fungal infections.

Case Continued

During an episode of pneumothorax, the patient undergoes chest tube placement, pleurodesis, and lung biopsy. Pathology reveals bronchiolitis obliterans as well as organizing pneumonia (Figure 2). No organisms are seen on acid-fast bacilli or GMS stains.

- What are the other late-onset noninfectious pulmonary complications?

Definitions of other late noninfectious pulmonary complications following HSCT are shown in Table 3.

Interstitial pneumonias may represent COP or may be idiopathic pneumonia syndrome with a later onset or a nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. This syndrome is poorly defined, with a number of differing definitions of the syndrome published in the literature.50–55

A rare pulmonary complication after HSCT is pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD). Pulmonary hypertension has been reported after HSCT,56 but PVOD is a subset of pulmonary hypertension. It is associated with pleural effusions and volume overload on chest radiography.57,58 It may present early or late after transplant and is poorly understood.

Besides obstructive and restrictive PFT abnormalities, changes in small airway function59 after transplant and loss in diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (D

Case Conclusion

The patient’s lung function continues to worsen, but no infectious etiologies are discovered. Ultimately, she dies of respiratory failure caused by progressive bronchiolitis obliterans.

Conclusion

Late pulmonary complications occur frequently in patients who have undergone HSCT. These complications can be classified as infectious versus noninfectious etiologies. Late-onset complications are more common in allogeneic transplantations because they are associated with chronic GVHD. These complications can be manifestations of pulmonary GHVD or can be infectious complications associated with prolonged immunosuppression. Appropriate monitoring for the development of BOS is essential. Early and aggressive treatment of respiratory infections and diagnostic bronchoscopy with BAL can help elucidate most infectious causes. Still, diagnostic challenges remain and multiple causes of respiratory deterioration can be present concurrently in the post-HSCT patient. Steroid therapy remains the mainstay treatment for most noninfectious pulmonary complications and should be strongly considered once infection is effectively ruled out.

1. Remberger M, Ackefors M, Berglund S, et al. Improved survival after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in recent years. A single-center study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2011;17:1688–97.

2. Wood KL, Esguerra VG. Management of late pulmonary complications after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Hosp Phys Hematology-Oncology Board Review Manual 2018;13(1):36–48.

3. Ninin E, Milpied N, Moreau P, et al. Longitudinal study of bacterial, viral, and fungal infections in adult recipients of bone marrow transplants. Clin Infect Dis 2001;33:41–7.

4. Roca J, Granena A, Rodriguez-Roisin R, et al. Fatal airway disease in an adult with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Thorax 1982;37:77–8.

5. Williams KM, Chien JW, Gladwin MT, Pavletic SZ. Bronchiolitis obliterans after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. JAMA 2009;302:306–14.

6. Chien JW, Martin PJ, Gooley TA, et al. Airflow obstruction after myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:208–14.

7. Holbro A, Lehmann T, Girsberger S, et al. Lung histology predicts outcome of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2013;19:973–80.

8. Chamberlain D, Maurer J, Chaparro C, Idolor L. Evaluation of transbronchial lung biopsy specimens in the diagnosis of bronchiolitis obliterans after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 1994;13:963–71.

9. Au BK, Au MA, Chien JW. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome epidemiology after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2011;17:1072–8.

10. Jagasia MH, Greinix HT, Arora M, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: I. The 2014 Diagnosis and Staging Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015;21:389–401.

11. Couriel D, Carpenter PA, Cutler C, et al. Ancillary therapy and supportive care of chronic graft-versus-host disease: national institutes of health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic Graft-versus-host disease: V. Ancillary Therapy and Supportive Care Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2006;12:375–96.

12. Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J 2005;26:948–68.

13. Williams KM, Hnatiuk O, Mitchell SA, et al. NHANES III equations enhance early detection and mortality prediction of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2014;49:561–6.

14. Hyatt RE, Cowl CT, Bjoraker JA, Scanlon PD. Conditions associated with an abnormal nonspecific pattern of pulmonary function tests. Chest 2009;135:419–24.

15. Bergeron A, Godet C, Chevret S, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic SCT: phenotypes and prognosis. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013;48:819–24.

16. Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2005;11:945–56.

17. Gazourian L, Coronata AM, Rogers AJ, et al. Airway dilation in bronchiolitis obliterans after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Respir Med 2013;107:276–83.

18. Gunn ML, Godwin JD, Kanne JP, et al. High-resolution CT findings of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Thorac Imaging 2008;23:244–50.

19. Sargent MA, Cairns RA, Murdoch MJ, et al. Obstructive lung disease in children after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: evaluation with high-resolution CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995;164:693–6.

20. Galban CJ, Boes JL, Bule M, et al. Parametric response mapping as an indicator of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2014;20:1592–8.

21. Meyer KC, Raghu G, Verleden GM, et al. An international ISHLT/ATS/ERS clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and management of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1479–1503.

22. Hildebrandt GC, Fazekas T, Lawitschka A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary chronic GVHD: report from the consensus conference on clinical practice in chronic GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011;46:1283–95.

23. Carpenter PA, Kitko CL, Elad S, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: V. The 2014 Ancillary Therapy and Supportive Care Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015;21:1167–87.

24. Norman BC, Jacobsohn DA, Williams KM, et al. Fluticasone, azithromycin and montelukast therapy in reducing corticosteroid exposure in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic SCT: a case series of eight patients. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011;46:1369–73.

25. Williams KM, Cheng GS, Pusic I, et al. Fluticasone, azithromycin, and montelukast treatment for new-onset bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2016;22:710–6.

26. Or R, Gesundheit B, Resnick I, et al. Sparing effect by montelukast treatment for chronic graft versus host disease: a pilot study. Transplantation 2007;83:577–81.

27. Cheng GS, Storer B, Chien JW, et al. Lung function trajectory in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016;13:1932–9.

28. Bergeron A, Belle A, Chevret S, et al. Combined inhaled steroids and bronchodilatators in obstructive airway disease after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2007;39:547–53.

29. Bashoura L, Gupta S, Jain A, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids stabilize constrictive bronchiolitis after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2008;41:63–7.

30. Bergeron A, Chevret S, Granata A, et al. Effect of azithromycin on airflow decline-free survival after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant: the ALLOZITHRO randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;318:557–66.

31. Gerhardt SG, McDyer JF, Girgis RE, et al. Maintenance azithromycin therapy for bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome: results of a pilot study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:121–5.

32. Khalid M, Al Saghir A, Saleemi S, et al. Azithromycin in bronchiolitis obliterans complicating bone marrow transplantation: a preliminary study. Eur Respir J 2005;25:490–3.

33. Maimon N, Lipton JH, Chan CK, Marras TK. Macrolides in the treatment of bronchiolitis obliterans in allograft recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant 2009;44:69–73.

34. Lam DC, Lam B, Wong MK, et al. Effects of azithromycin in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic SCT--a randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled study. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011;46:1551–6.

35. Yadav H, Peters SG, Keogh KA, et al. Azithromycin for the treatment of obliterative bronchiolitis after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2016;22:2264–9.

36. Vos R, Vanaudenaerde BM, Verleden SE, et al. A randomised controlled trial of azithromycin to prevent chronic rejection after lung transplantation. Eur Respir J 2011;37:164–72.

37. Svanstrom H, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of azithromycin and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1704–12.

38. Albert RK, Connett J, Bailey WC, et al. Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med 2011;365:689–98.

39. Tran J, Norder EE, Diaz PT, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2012;18:1250–4.

40. Lucid CE, Savani BN, Engelhardt BG, et al. Extracorporeal photopheresis in patients with refractory bronchiolitis obliterans developing after allo-SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011;46:426–9.

41. Hostettler KE, Halter JP, Gerull S, et al. Calcineurin inhibitors in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome following stem cell transplantation. Eur Respir J 2014;43:221–32.

42. Holm AM, Riise GC, Brinch L, et al. Lung transplantation for bronchiolitis obliterans after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: unresolved questions. Transplantation 2013;96:e21–22.

43. Cheng GS, Edelman JD, Madtes DK, et al. Outcomes of lung transplantation after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2014;20:1169–75.

44. Okumura H, Ohtake S, Ontachi Y, et al. Living-donor lobar lung transplantation for broncho-bronchiolitis obliterans after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: does bronchiolitis obliterans recur in transplanted lungs? Int J Hematol 2007;86:369–73.

45. Olivieri A, Cimminiello M, Corradini P, et al. Long-term outcome and prospective validation of NIH response criteria in 39 patients receiving imatinib for steroid-refractory chronic GVHD. Blood 2013;122:4111–8.

46. Rahmanian S, Wood KL. Bronchiolitis obliterans and the risk of pneumothorax after transbronchial biopsy. Respiratory Medicine CME 2010;3:87–9.

47. Sakai R, Kanamori H, Nakaseko C, et al. Air-leak syndrome following allo-SCT in adult patients: report from the Kanto Study Group for Cell Therapy in Japan. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011;46:379–84.

48. Visscher DW, Myers JL. Histologic spectrum of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:322–9.

49. Cordier JF. Cryptogenic organising pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2006;28:422–46.

50. Nishio N, Yagasaki H, Takahashi Y, et al. Late-onset non-infectious pulmonary complications following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children. Bone Marrow Transplant 2009;44:303–8.

51. Ueda K, Watadani T, Maeda E, et al. Outcome and treatment of late-onset noninfectious pulmonary complications after allogeneic haematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2010;45:1719–27.

52. Schlemmer F, Chevret S, Lorillon G, et al. Late-onset noninfectious interstitial lung disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Respir Med 2014;108:1525–33.

53. Palmas A, Tefferi A, Myers JL, et al. Late-onset noninfectious pulmonary complications after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Br J Haematol 1998;100:680–7.

54. Sakaida E, Nakaseko C, Harima A, et al. Late-onset noninfectious pulmonary complications after allogeneic stem cell transplantation are significantly associated with chronic graft-versus-host disease and with the graft-versus-leukemia effect. Blood 2003;102:4236–42.

55. Solh M, Arat M, Cao Q, et al. Late-onset noninfectious pulmonary complications in adult allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Transplantation 2011;91:798–803.

56. Dandoy CE, Hirsch R, Chima R, et al. Pulmonary hypertension after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2013;19:1546–56.

57. Bunte MC, Patnaik MM, Pritzker MR, Burns LJ. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a rare model of endothelial dysfunction. Bone Marrow Transplant 2008;41:677–86.

58. Troussard X, Bernaudin JF, Cordonnier C, et al. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease after bone marrow transplantation. Thorax 1984;39:956–7.

59. Lahzami S, Schoeffel RE, Pechey V, et al. Small airways function declines after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Eur Respir J 2011;38:1180–8.

60. Jain NA, Pophali PA, Klotz JK, et al. Repair of impaired pulmonary function is possible in very-long-term allogeneic stem cell transplantation survivors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2014;20:209–13.

61. Barisione G, Bacigalupo A, Crimi E, et al. Changes in lung volumes and airway responsiveness following haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Eur Respir J 2008;32:1576–82.

62. Kovalszki A, Schumaker GL, Klein A, et al. Reduced respiratory and skeletal muscle strength in survivors of sibling or unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2008;41:965–9.

63. Mathiesen S, Uhlving HH, Buchvald F, et al. Aerobic exercise capacity at long-term follow-up after paediatric allogeneic haematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2014;49:1393–9.

1. Remberger M, Ackefors M, Berglund S, et al. Improved survival after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in recent years. A single-center study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2011;17:1688–97.

2. Wood KL, Esguerra VG. Management of late pulmonary complications after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Hosp Phys Hematology-Oncology Board Review Manual 2018;13(1):36–48.

3. Ninin E, Milpied N, Moreau P, et al. Longitudinal study of bacterial, viral, and fungal infections in adult recipients of bone marrow transplants. Clin Infect Dis 2001;33:41–7.

4. Roca J, Granena A, Rodriguez-Roisin R, et al. Fatal airway disease in an adult with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Thorax 1982;37:77–8.

5. Williams KM, Chien JW, Gladwin MT, Pavletic SZ. Bronchiolitis obliterans after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. JAMA 2009;302:306–14.

6. Chien JW, Martin PJ, Gooley TA, et al. Airflow obstruction after myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:208–14.

7. Holbro A, Lehmann T, Girsberger S, et al. Lung histology predicts outcome of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2013;19:973–80.

8. Chamberlain D, Maurer J, Chaparro C, Idolor L. Evaluation of transbronchial lung biopsy specimens in the diagnosis of bronchiolitis obliterans after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 1994;13:963–71.

9. Au BK, Au MA, Chien JW. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome epidemiology after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2011;17:1072–8.

10. Jagasia MH, Greinix HT, Arora M, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: I. The 2014 Diagnosis and Staging Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015;21:389–401.

11. Couriel D, Carpenter PA, Cutler C, et al. Ancillary therapy and supportive care of chronic graft-versus-host disease: national institutes of health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic Graft-versus-host disease: V. Ancillary Therapy and Supportive Care Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2006;12:375–96.

12. Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J 2005;26:948–68.

13. Williams KM, Hnatiuk O, Mitchell SA, et al. NHANES III equations enhance early detection and mortality prediction of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2014;49:561–6.

14. Hyatt RE, Cowl CT, Bjoraker JA, Scanlon PD. Conditions associated with an abnormal nonspecific pattern of pulmonary function tests. Chest 2009;135:419–24.

15. Bergeron A, Godet C, Chevret S, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic SCT: phenotypes and prognosis. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013;48:819–24.

16. Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2005;11:945–56.

17. Gazourian L, Coronata AM, Rogers AJ, et al. Airway dilation in bronchiolitis obliterans after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Respir Med 2013;107:276–83.

18. Gunn ML, Godwin JD, Kanne JP, et al. High-resolution CT findings of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Thorac Imaging 2008;23:244–50.

19. Sargent MA, Cairns RA, Murdoch MJ, et al. Obstructive lung disease in children after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: evaluation with high-resolution CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995;164:693–6.

20. Galban CJ, Boes JL, Bule M, et al. Parametric response mapping as an indicator of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2014;20:1592–8.

21. Meyer KC, Raghu G, Verleden GM, et al. An international ISHLT/ATS/ERS clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and management of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1479–1503.

22. Hildebrandt GC, Fazekas T, Lawitschka A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary chronic GVHD: report from the consensus conference on clinical practice in chronic GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011;46:1283–95.