User login

Mrs. C, age 56, has a history of major depressive disorder (MDD). She has been stable for 5 years without medication. Six months ago, she presented to you, along with her son, seeking help. She reported that she had been experiencing insomnia, fatigue, and was not engaging in hobbies. Her son told you that his mother had lost weight and had been avoiding family dinners. Mrs. C reported recurrent thoughts of dying and heard voices vividly telling her that she was a burden and that her family would be better off without her. However, there was no imminent danger of self-harm. At that appointment, you initiated

Since that time, Mrs. C has followed up with you monthly with good response to the medications. Currently, she states her depression is much improved, and she denies hearing voices for approximately 5 months.

Based on her presentation and response, what do the data suggest about her length of treatment, and when should you consider tapering the antipsychotic medication?

In DSM-5, MDD with psychotic features is a severe subtype of MDD that is defined as a major depressive episode characterized by delusions and/or hallucinations.1 In the general population, the lifetime prevalence of this disorder varies from 0.35% to 1%, and the rate is higher in older patients.2 Risk factors include female gender, family history, and concomitant bipolar disorder.2

Epidemiologic studies have shown that psychotic features can occur in 15% to 20% of patients with MDD. The psychotic features that occur during these episodes are delusions and hallucinations.1 These features can be either mood-congruent (related to the depressive themes of worthlessness or guilt) or mood-incongruent (ie, unrelated to depressive themes).1

Treatment options: ECT or pharmacotherapy

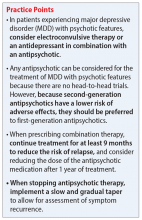

Guidelines from the American Psychiatric Association3 and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence4 recommend treating depression with psychosis with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or with combined antidepressant and antipsychotic medications as first-line options. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) Algorithm for MDD,5 which closely focuses on treatment of MDD with psychotic features, can be used for treatment decisions (see Related Resources).

Electroconvulsive therapy is known to be efficacious in treating patients with MDD with psychotic features and should be considered as a treatment option. However, medication therapy is often chosen as the initial treatment due to the limitations of ECT, including accessibility, cost, and patient preference. However, in certain cases, ECT is the preferred option because it can provide rapid and significant improvement in patients with severe psychosis, suicidality, or risk of imminent harm.

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy for the treatment of MDD with psychotic features should consist of a combination of an antidepressant and antipsychotic medication. This combination has been shown to be more effective than either agent alone. Some combinations have been studied specifically for MDD with psychosis. The Study of the Pharmacotherapy of Psychotic Depression (STOP-PD), a 12-week, double-blind, randomized controlled trial, found that the combination of sertraline and olanzapine was efficacious and superior to monotherapy with olanzapine in an acute setting.6 In another study, the combination of olanzapine and

How long should treatment last?

The optimal timeline for treating patients with MDD with psychotic features is unknown. According to the TMAP algorithm and expert opinion, the continuation phase of pharmacotherapy should include treatment for at least 4 months with an antipsychotic medication and at least 2 years to lifetime treatment with an antidepressant.5 The STOP-PD II study, which was a continuation of the 12-week STOP-PD study, examined antipsychotic duration to determine the effects of continuing olanzapine once an episode of psychotic depression had responded to olanzapine and sertraline.11 Patients who had achieved remission after receiving olanzapine and sertraline were randomized to continue to receive this combination or to receive sertraline plus placebo for 36 weeks. The primary outcome was relapse, which was broadly defined as 1 of the following11:

- a Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (SCID)-rated assessment that revealed the patient had enough symptoms to meet criteria for a DSM-IV major depressive episode

- a 17-item HAM-D scoren of ≥18

- SCID-rated psychosis

- other significant clinical worsening, defined as having a suicide plan or attempting suicide, developing SCID-rated symptoms of mania or hypomania, or being hospitalized in a psychiatric unit.

Compared with sertraline plus placebo, continuing sertraline plus olanzapine reduced the risk of relapse over 36 weeks (hazard ratio, 0.25; 95% confidence interval, 0.13 to 0.48; P < .001).11 However, as expected, the incidence of adverse effects such as weight gain and parkinsonism was higher in the olanzapine group. Therefore, it is important to consider the potential long-term adverse effects of continuing antipsychotic medications.

Weighing the evidence

Electroconvulsive therapy is considered a first-line treatment option for MDD with psychotic features; however, because of limitations associated with this approach, antidepressants plus antipsychotics are often utilized as an initial treatment.

Continue to: CASE

CASE CONTINUED

Based on the results of the STOP-PD and STOP-PD II trials, Mrs. C should be continued on sertraline plus olanzapine for at least another 3 to 6 months before an olanzapine taper should be considered. At that time, the risks and benefits of a taper vs continuing therapy should be considered. Given her history of MDD and the severity of this most recent episode, sertraline therapy should be continued for at least 2 years, and possibly indefinitely.

Related Resources

- Texas Medication Algorithm Project. Algorithm for the treatment of major depressive disorder with psychotic features. https://chsciowa.org/sites/chsciowa.org/files/resource/files/9_-_depression_med_algorithm_supplement.pdf

- Dold M, Bartova L, Kautzky A, et al. Psychotic features in patients with major depressive disorder: a report from the European Group for the Study of Resistant Depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(1):17m12090. doi: 10.4088/ JCP.17m12090

- Flint AJ, Meyers BS, Rothschild AJ, et al. Effect of continuing olanzapine vs placebo on relapse among patients with psychotic depression in remission: the STOP-PD II randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322(7): 622-631.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil, Endep

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Haloperidol • Haldol

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Jääskeläinen E, Juola T, Korpela H, et al. Epidemiology of psychotic depression - systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2018;48(6):905-918.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4)(suppl):1-45.

4. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Depression in adults: recognition and management: clinical guideline [CG90]. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Published October 28, 2009. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90

5. Crimson ML, Trivedi M, Pigott TA, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project: report of the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on medication treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(3):142-156.

6. Meyers BS, Flint AJ, Rothschild AJ, et al. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of olanzapine plus sertraline vs olanzapine plus placebo for psychotic depression: the study of pharmacotherapy for psychotic depression -- the STOP-PD study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(8):838-847.

7. Rothschild AJ, Williamson DJ, Tohen MF, et al. A double-blind, randomized study of olanzapine and olanzapine/fluoxetine combination for major depression with psychotic features. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(4):365-373.

8. Wijkstra J, Burger H, van den Broek WW, et al. Treatment of unipolar psychotic depression: a randomized, doubleblind study comparing imipramine, venlafaxine, and venlafaxine plus quetiapine. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;21(3):190-200.

9. Muller-Siecheneder F, Muller M, Hillert A, et al. Risperidone versus haloperidol and amitriptyline in the treatment of patients with a combined psychotic and depressive syndrome. J Clin Psychopharm. 1998;18(2):111-120.

10. Spiker DG, Weiss JC, Dealy RS, et al. The pharmacological treatment of delusional depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(4):430-436.

11. Flint AJ, Meyers BS, Rothschild AJ, et al. Effect of continuing olanzapine vs placebo on relapse among patients with psychotic depression in remission: the STOP-PD II randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322(7):622-631.

Mrs. C, age 56, has a history of major depressive disorder (MDD). She has been stable for 5 years without medication. Six months ago, she presented to you, along with her son, seeking help. She reported that she had been experiencing insomnia, fatigue, and was not engaging in hobbies. Her son told you that his mother had lost weight and had been avoiding family dinners. Mrs. C reported recurrent thoughts of dying and heard voices vividly telling her that she was a burden and that her family would be better off without her. However, there was no imminent danger of self-harm. At that appointment, you initiated

Since that time, Mrs. C has followed up with you monthly with good response to the medications. Currently, she states her depression is much improved, and she denies hearing voices for approximately 5 months.

Based on her presentation and response, what do the data suggest about her length of treatment, and when should you consider tapering the antipsychotic medication?

In DSM-5, MDD with psychotic features is a severe subtype of MDD that is defined as a major depressive episode characterized by delusions and/or hallucinations.1 In the general population, the lifetime prevalence of this disorder varies from 0.35% to 1%, and the rate is higher in older patients.2 Risk factors include female gender, family history, and concomitant bipolar disorder.2

Epidemiologic studies have shown that psychotic features can occur in 15% to 20% of patients with MDD. The psychotic features that occur during these episodes are delusions and hallucinations.1 These features can be either mood-congruent (related to the depressive themes of worthlessness or guilt) or mood-incongruent (ie, unrelated to depressive themes).1

Treatment options: ECT or pharmacotherapy

Guidelines from the American Psychiatric Association3 and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence4 recommend treating depression with psychosis with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or with combined antidepressant and antipsychotic medications as first-line options. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) Algorithm for MDD,5 which closely focuses on treatment of MDD with psychotic features, can be used for treatment decisions (see Related Resources).

Electroconvulsive therapy is known to be efficacious in treating patients with MDD with psychotic features and should be considered as a treatment option. However, medication therapy is often chosen as the initial treatment due to the limitations of ECT, including accessibility, cost, and patient preference. However, in certain cases, ECT is the preferred option because it can provide rapid and significant improvement in patients with severe psychosis, suicidality, or risk of imminent harm.

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy for the treatment of MDD with psychotic features should consist of a combination of an antidepressant and antipsychotic medication. This combination has been shown to be more effective than either agent alone. Some combinations have been studied specifically for MDD with psychosis. The Study of the Pharmacotherapy of Psychotic Depression (STOP-PD), a 12-week, double-blind, randomized controlled trial, found that the combination of sertraline and olanzapine was efficacious and superior to monotherapy with olanzapine in an acute setting.6 In another study, the combination of olanzapine and

How long should treatment last?

The optimal timeline for treating patients with MDD with psychotic features is unknown. According to the TMAP algorithm and expert opinion, the continuation phase of pharmacotherapy should include treatment for at least 4 months with an antipsychotic medication and at least 2 years to lifetime treatment with an antidepressant.5 The STOP-PD II study, which was a continuation of the 12-week STOP-PD study, examined antipsychotic duration to determine the effects of continuing olanzapine once an episode of psychotic depression had responded to olanzapine and sertraline.11 Patients who had achieved remission after receiving olanzapine and sertraline were randomized to continue to receive this combination or to receive sertraline plus placebo for 36 weeks. The primary outcome was relapse, which was broadly defined as 1 of the following11:

- a Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (SCID)-rated assessment that revealed the patient had enough symptoms to meet criteria for a DSM-IV major depressive episode

- a 17-item HAM-D scoren of ≥18

- SCID-rated psychosis

- other significant clinical worsening, defined as having a suicide plan or attempting suicide, developing SCID-rated symptoms of mania or hypomania, or being hospitalized in a psychiatric unit.

Compared with sertraline plus placebo, continuing sertraline plus olanzapine reduced the risk of relapse over 36 weeks (hazard ratio, 0.25; 95% confidence interval, 0.13 to 0.48; P < .001).11 However, as expected, the incidence of adverse effects such as weight gain and parkinsonism was higher in the olanzapine group. Therefore, it is important to consider the potential long-term adverse effects of continuing antipsychotic medications.

Weighing the evidence

Electroconvulsive therapy is considered a first-line treatment option for MDD with psychotic features; however, because of limitations associated with this approach, antidepressants plus antipsychotics are often utilized as an initial treatment.

Continue to: CASE

CASE CONTINUED

Based on the results of the STOP-PD and STOP-PD II trials, Mrs. C should be continued on sertraline plus olanzapine for at least another 3 to 6 months before an olanzapine taper should be considered. At that time, the risks and benefits of a taper vs continuing therapy should be considered. Given her history of MDD and the severity of this most recent episode, sertraline therapy should be continued for at least 2 years, and possibly indefinitely.

Related Resources

- Texas Medication Algorithm Project. Algorithm for the treatment of major depressive disorder with psychotic features. https://chsciowa.org/sites/chsciowa.org/files/resource/files/9_-_depression_med_algorithm_supplement.pdf

- Dold M, Bartova L, Kautzky A, et al. Psychotic features in patients with major depressive disorder: a report from the European Group for the Study of Resistant Depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(1):17m12090. doi: 10.4088/ JCP.17m12090

- Flint AJ, Meyers BS, Rothschild AJ, et al. Effect of continuing olanzapine vs placebo on relapse among patients with psychotic depression in remission: the STOP-PD II randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322(7): 622-631.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil, Endep

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Haloperidol • Haldol

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Mrs. C, age 56, has a history of major depressive disorder (MDD). She has been stable for 5 years without medication. Six months ago, she presented to you, along with her son, seeking help. She reported that she had been experiencing insomnia, fatigue, and was not engaging in hobbies. Her son told you that his mother had lost weight and had been avoiding family dinners. Mrs. C reported recurrent thoughts of dying and heard voices vividly telling her that she was a burden and that her family would be better off without her. However, there was no imminent danger of self-harm. At that appointment, you initiated

Since that time, Mrs. C has followed up with you monthly with good response to the medications. Currently, she states her depression is much improved, and she denies hearing voices for approximately 5 months.

Based on her presentation and response, what do the data suggest about her length of treatment, and when should you consider tapering the antipsychotic medication?

In DSM-5, MDD with psychotic features is a severe subtype of MDD that is defined as a major depressive episode characterized by delusions and/or hallucinations.1 In the general population, the lifetime prevalence of this disorder varies from 0.35% to 1%, and the rate is higher in older patients.2 Risk factors include female gender, family history, and concomitant bipolar disorder.2

Epidemiologic studies have shown that psychotic features can occur in 15% to 20% of patients with MDD. The psychotic features that occur during these episodes are delusions and hallucinations.1 These features can be either mood-congruent (related to the depressive themes of worthlessness or guilt) or mood-incongruent (ie, unrelated to depressive themes).1

Treatment options: ECT or pharmacotherapy

Guidelines from the American Psychiatric Association3 and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence4 recommend treating depression with psychosis with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or with combined antidepressant and antipsychotic medications as first-line options. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) Algorithm for MDD,5 which closely focuses on treatment of MDD with psychotic features, can be used for treatment decisions (see Related Resources).

Electroconvulsive therapy is known to be efficacious in treating patients with MDD with psychotic features and should be considered as a treatment option. However, medication therapy is often chosen as the initial treatment due to the limitations of ECT, including accessibility, cost, and patient preference. However, in certain cases, ECT is the preferred option because it can provide rapid and significant improvement in patients with severe psychosis, suicidality, or risk of imminent harm.

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy for the treatment of MDD with psychotic features should consist of a combination of an antidepressant and antipsychotic medication. This combination has been shown to be more effective than either agent alone. Some combinations have been studied specifically for MDD with psychosis. The Study of the Pharmacotherapy of Psychotic Depression (STOP-PD), a 12-week, double-blind, randomized controlled trial, found that the combination of sertraline and olanzapine was efficacious and superior to monotherapy with olanzapine in an acute setting.6 In another study, the combination of olanzapine and

How long should treatment last?

The optimal timeline for treating patients with MDD with psychotic features is unknown. According to the TMAP algorithm and expert opinion, the continuation phase of pharmacotherapy should include treatment for at least 4 months with an antipsychotic medication and at least 2 years to lifetime treatment with an antidepressant.5 The STOP-PD II study, which was a continuation of the 12-week STOP-PD study, examined antipsychotic duration to determine the effects of continuing olanzapine once an episode of psychotic depression had responded to olanzapine and sertraline.11 Patients who had achieved remission after receiving olanzapine and sertraline were randomized to continue to receive this combination or to receive sertraline plus placebo for 36 weeks. The primary outcome was relapse, which was broadly defined as 1 of the following11:

- a Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (SCID)-rated assessment that revealed the patient had enough symptoms to meet criteria for a DSM-IV major depressive episode

- a 17-item HAM-D scoren of ≥18

- SCID-rated psychosis

- other significant clinical worsening, defined as having a suicide plan or attempting suicide, developing SCID-rated symptoms of mania or hypomania, or being hospitalized in a psychiatric unit.

Compared with sertraline plus placebo, continuing sertraline plus olanzapine reduced the risk of relapse over 36 weeks (hazard ratio, 0.25; 95% confidence interval, 0.13 to 0.48; P < .001).11 However, as expected, the incidence of adverse effects such as weight gain and parkinsonism was higher in the olanzapine group. Therefore, it is important to consider the potential long-term adverse effects of continuing antipsychotic medications.

Weighing the evidence

Electroconvulsive therapy is considered a first-line treatment option for MDD with psychotic features; however, because of limitations associated with this approach, antidepressants plus antipsychotics are often utilized as an initial treatment.

Continue to: CASE

CASE CONTINUED

Based on the results of the STOP-PD and STOP-PD II trials, Mrs. C should be continued on sertraline plus olanzapine for at least another 3 to 6 months before an olanzapine taper should be considered. At that time, the risks and benefits of a taper vs continuing therapy should be considered. Given her history of MDD and the severity of this most recent episode, sertraline therapy should be continued for at least 2 years, and possibly indefinitely.

Related Resources

- Texas Medication Algorithm Project. Algorithm for the treatment of major depressive disorder with psychotic features. https://chsciowa.org/sites/chsciowa.org/files/resource/files/9_-_depression_med_algorithm_supplement.pdf

- Dold M, Bartova L, Kautzky A, et al. Psychotic features in patients with major depressive disorder: a report from the European Group for the Study of Resistant Depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(1):17m12090. doi: 10.4088/ JCP.17m12090

- Flint AJ, Meyers BS, Rothschild AJ, et al. Effect of continuing olanzapine vs placebo on relapse among patients with psychotic depression in remission: the STOP-PD II randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322(7): 622-631.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil, Endep

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Haloperidol • Haldol

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Jääskeläinen E, Juola T, Korpela H, et al. Epidemiology of psychotic depression - systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2018;48(6):905-918.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4)(suppl):1-45.

4. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Depression in adults: recognition and management: clinical guideline [CG90]. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Published October 28, 2009. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90

5. Crimson ML, Trivedi M, Pigott TA, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project: report of the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on medication treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(3):142-156.

6. Meyers BS, Flint AJ, Rothschild AJ, et al. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of olanzapine plus sertraline vs olanzapine plus placebo for psychotic depression: the study of pharmacotherapy for psychotic depression -- the STOP-PD study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(8):838-847.

7. Rothschild AJ, Williamson DJ, Tohen MF, et al. A double-blind, randomized study of olanzapine and olanzapine/fluoxetine combination for major depression with psychotic features. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(4):365-373.

8. Wijkstra J, Burger H, van den Broek WW, et al. Treatment of unipolar psychotic depression: a randomized, doubleblind study comparing imipramine, venlafaxine, and venlafaxine plus quetiapine. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;21(3):190-200.

9. Muller-Siecheneder F, Muller M, Hillert A, et al. Risperidone versus haloperidol and amitriptyline in the treatment of patients with a combined psychotic and depressive syndrome. J Clin Psychopharm. 1998;18(2):111-120.

10. Spiker DG, Weiss JC, Dealy RS, et al. The pharmacological treatment of delusional depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(4):430-436.

11. Flint AJ, Meyers BS, Rothschild AJ, et al. Effect of continuing olanzapine vs placebo on relapse among patients with psychotic depression in remission: the STOP-PD II randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322(7):622-631.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Jääskeläinen E, Juola T, Korpela H, et al. Epidemiology of psychotic depression - systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2018;48(6):905-918.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4)(suppl):1-45.

4. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Depression in adults: recognition and management: clinical guideline [CG90]. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Published October 28, 2009. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90

5. Crimson ML, Trivedi M, Pigott TA, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project: report of the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on medication treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(3):142-156.

6. Meyers BS, Flint AJ, Rothschild AJ, et al. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of olanzapine plus sertraline vs olanzapine plus placebo for psychotic depression: the study of pharmacotherapy for psychotic depression -- the STOP-PD study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(8):838-847.

7. Rothschild AJ, Williamson DJ, Tohen MF, et al. A double-blind, randomized study of olanzapine and olanzapine/fluoxetine combination for major depression with psychotic features. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(4):365-373.

8. Wijkstra J, Burger H, van den Broek WW, et al. Treatment of unipolar psychotic depression: a randomized, doubleblind study comparing imipramine, venlafaxine, and venlafaxine plus quetiapine. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;21(3):190-200.

9. Muller-Siecheneder F, Muller M, Hillert A, et al. Risperidone versus haloperidol and amitriptyline in the treatment of patients with a combined psychotic and depressive syndrome. J Clin Psychopharm. 1998;18(2):111-120.

10. Spiker DG, Weiss JC, Dealy RS, et al. The pharmacological treatment of delusional depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(4):430-436.

11. Flint AJ, Meyers BS, Rothschild AJ, et al. Effect of continuing olanzapine vs placebo on relapse among patients with psychotic depression in remission: the STOP-PD II randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322(7):622-631.