User login

Prior to the first approved disease modifying therapy (DMT) in the 1990s, treatment approaches for multiple sclerosis (MS) were not well understood. The discovery that MS was an immune mediated inflammatory disease paved the way for the treatments we know today. In 1993, interferon β‐1b became the first DMT for MS approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Approvals for interferon β‐1a as well as glatiramer acetate (GA) soon followed. Today, we consider these the mildest immunosuppressant DMTs; however, their success verified that suppressing the immune system had a positive effect on the MS disease process.

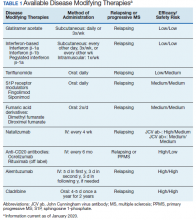

Following these approvals, the disease process in MS is now better understood. Recently approved therapies include monoclonal antibodies, which affect other immune pathways. Today, there are 14 approved DMTs (Table 1). Although the advent of these newer DMTs has revolutionized care for patients with MS, it has been accompanied by increasing costs for the agents. Direct medical costs associated with MS management, coupled with indirect costs from lost productivity, have been estimated to be $24.2 billion annually in the US.1 These increases have been seen across many levels of insurance coverage—private payer, Medicare, and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).2,3

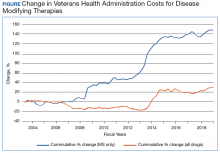

The Figure demonstrates the cost increase that have been seen across VHA between 2004 and 2019 for the DMTs identified in Table 1. Indeed, this compound annual growth rate may be an underestimate because infusion therapies (eg, natalizumab, ocrelizumab, and alemtuzumab) are difficult to track as they may be dispensed directly via a Risk Evaluation Medication Strategy (REMS) program. According to the VHA Pharmacy Benefit Management Service (PBM), in September 2019, dimethyl fumarate (DMF) had the 13th highest total outpatient drug cost for the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), interferon β‐1a ranked 62nd and 83rd (prefilled pen and syringe, respectively), and GA 40 mg ranked 89th.

The DMT landscape has demonstrated significant price fluctuations and given rise to a class of medications that requires extensive oversight in terms of efficacy, safety, and cost minimization. The purpose of this article is to show how delivery of this specialty group of medications can be optimized with safety, efficacy, and cost value within a large health care system.

Factors Impacting DMT Use

Recent changes to MS typing have impacted utilization of DMTs. Traditionally, there were 4 subtypes of MS: relapsing remitting (RRMS), secondary progressive (SPMS), progressive relapsing (PRMS), and primary progressive (PPMS). These subtypes are now viewed more broadly and grouped as either relapsing or progressive. The traditional subtypes fall under these broader definitions. Additionally, SPMS has been broken into active SPMS, characterized by continued worsening of disability unrelated to acute relapses, superimposed with activity that can be seen on magnetic resonance images (MRIs), and nonactive SPMS, which has the same disability progression as active SPMS but without MRI-visible activity.4-6 In 2019, these supplementary designations to SPMS made their first appearance in FDA-approved indications. All existing DMTs now include this terminology in their labelling and are indicated in active SPMS. There remain no DMTs that treat nonactive SPMS.

The current landscape of DMTs is highly varied in method of administration, risks, and benefits. As efficacy of these medications often is marked by how well they can prevent the immune system from attacking myelin, an inverse relationship between safety and efficacy results. The standard treatment outcomes in MS have evolved over time. The following are the commonly used primary outcomes in clinical trials: relapse reduction; increased time between relapses; decreased severity of relapses; prevention or extend time to disability milestones as measured by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) and other disability measures; prevention or extension of time to onset of secondary progressive disease; prevention or reduction of the number and size of new and enhancing lesions on MRI; and limitation of overall MRI lesion burden in the central nervous system (CNS).

Newer treatment outcomes employed in more recent trials include: measures of axonal damage, CNS atrophy, evidence of microscopic disease via conventional MRI and advanced imaging modalities, biomarkers associated with inflammatory disease activity and neurodegeneration in MS, and the use of no evidence of disease activity (NEDA). These outcomes also must be evaluated by the safety concerns of each agent. Short- and long-term safety are critical factors in the selection of DMTs for MS. The injectable therapies for MS (interferon β‐1a, interferon β‐1b, and GA) have established long-term safety profiles from > 20 years of continuous use. The long-term safety profiles of oral immunomodulatory agents and monoclonal antibodies for these drugs in MS have yet to be determined. Safety concerns associated with some therapies and added requirements for safety monitoring may increase the complexity of a therapeutic selection.

Current cost minimization strategies for DMT include limiting DMT agents on formularies, tier systems that incentivize patients/prescribers to select the lowest priced agents on the formulary, negotiating arrangements with manufacturers to freeze prices or provide discounts in exchange for a priority position in the formulary, and requiring prior authorization to initiate or switch therapy. The use of generic medications and interchange to these agents from a brand name formulation can help reduce expense. Several of these strategies have been implemented in VHA.

Disease-Modifying Therapies

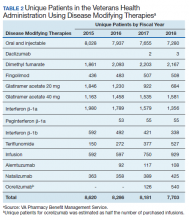

In 2019, 18,645 veterans with MS had either a MS-specific DMT or ≥ 1 annual encounters with a primary diagnosis of MS. Of this population, 4,720 were female and 13,357 were service connected according to VA data. About 50% of veterans with MS take a DMT. This percentage has remained stable over the past decade (Table 2). Although it appears the number of unique veterans prescribed an outpatient DMT is decreasing, this does not include the growing use of infused DMTs or DMTs obtained through the Veterans Choice Program (VCP)/Community Care (CC).

The overall outpatient pharmacy costs for veterans have remained constant despite the reduction in outpatient pharmacy prescription numbers. This may be due to increases in DMT cost to the VHA and the use of more expensive oral agents over the previously used platform injection DMTs.

Generic Conversion

GA is available in 20 mg daily and 40 mg3 times weekly subcutaneous injection dosing. The first evidence of clinical efficacy for a generic formulation for GA was evaluated by the GATE trial.7 This trial was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, active- and placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Eligible participants were randomized to receive daily SC injection for 9 months of 20 mg generic GA (n = 5,353), 20 mg brand GA (n = 5,357), or placebo (n = 584). The primary endpoint was the mean number of gadolinium (Gd1) lesions visible on MRIs during months 7, 8, and 9, which were significantly reduced in the combined GA-treated group and in each GA group individually when compared with the placebo group, confirming the study sensitivity (ie, GA was effective under the conditions of the study). Tolerability (including injection site reactions) and safety (incidence, spectrum, and severity of adverse events [AEs]) were similar in the generic and brand GA groups. These results demonstrated that generic and brand GA had equivalent efficacy, tolerability, and safety over a 9-month period.7

Results of a 15-month extension of the study were presented in 2015 and showed similar efficacy, safety, and tolerability in participants treated with generic GA for 2 years and patients switched from brand to generic GA.8 Multiple shifts for GA occurred, most notably the conversion from branded Copaxone (Teva Pharmaceutical Industries) to generic Glatopa (Sandoz). Subsequently, Sandoz released a generic 40 mg 3 times weekly formulation. Additionally, Mylan entered the generic GA market. With 3 competing manufacturers, internal data from the VHA indicated that it was able to negotiate a single source contract for this medication that provided a savings of $32,088,904.69 between September 2016 and May 2019.

The impact of generic conversions is just being realized. Soon, patents will begin to expire for oral DMTs, leading to an expected growth of generic alternatives. Already the FDA has approved 4 generic alternatives for teriflunomide, 3 for fingolimod (with 13 tentative approvals), and 15 generic alternatives for dimethyl fumarate (DMF). Implementation of therapeutic interchanges will be pursued by VHA as clinically supported by evidence.

Criteria for Use

PBM supports utilizing criteria to help guide providers on DMT options and promote safe, effective, and value-based selection of a DMT. The PBM creates monographs and criteria for use (CFU) for new medications. The monograph contains a literature evaluation of all studies available to date that concern both safety and efficacy of the new medication. Therapeutic alternatives also are presented and assessed for key elements that may determine the most safe and effective use. Additional safety areas for the new medications such as look-alike, sound-alike potential, special populations use (ie, those who are pregnant, the elderly, and those with liver or renal dysfunction), and drug-drug interactions are presented. Lastly, and possibly most importantly in an ever-growing growing world of DMTs, the monograph describes a reasonable place in therapy for the new DMT.

CFU are additional guidance for some DMTs. The development of CFU are based on several questions that arise during the monograph development for a DMT. These include, but are not limited to:

- Are there safety concerns that require the drug to receive a review to ensure safe prescribing (eg, agents with REMS programs, or safety concerns in specific populations)?

- Does the drug require a specialty provider type with knowledge and experience in those disease states to ensure appropriate and safe prescribing (eg restricted to infectious diseases)?

- Do VHA or non-VHA guidelines suggest alternative therapy be used prior to the agent?

- Is a review deemed necessary to ensure the preferred agent is used first (eg, second-line therapy)?

The CFU defines parameters of drug use consistent with high quality and evidence-based patient care. CFUs also serve as a basis for monitoring local, regional, and national patterns of pharmacologic care and help guide health care providers (HCPs) on appropriate use of medication.

CFUs are designed to ensure the HCP is safely starting a medication that has evidence for efficacy for their patient. For example, alemtuzumab is a high-risk, high-efficacy DMT. The alemtuzumab CFU acknowledges this by having exclusion criteria that prevent a veteran at high risk (ie, on another immunosuppressant) from being exposed to severe AEs (ie, severe leukopenia) that are associated with the medication. On the other hand, the inclusion criteria recognize the benefits of alemtuzumab and allows those with highly active MS who have failed other DMTs to receive the medication.

The drug monograph and CFU process is an important part of VHA efforts to optimize patient care. After a draft version is developed, HCPs can provide feedback on the exclusion/inclusion criteria and describe how they anticipate using the medication in their practice. This insight can be beneficial for MS treatment as diverse HCPs may have distinct viewpoints on how DMTs should be started. Pharmacists and physicians on a national level then discuss and decide together what to include in the final drafts of the drug monograph and CFU. Final documents are disseminated to all sites, which encourages consistent practices across the VHA.9 These documents are reviewed on a regular basis and updated as needed based on available literature evidence.

It is well accepted that early use of DMT correlates with lower accumulated long-term disability.10 However, discontinuation of DMT should be treated with equal importance. This benefits the patient by reducing their risk of AEs from DMTs and provides cost savings. Age and disease stability are factors to consider for DMT discontinuation. In a study with patients aged > 45 years and another with patients aged > 60 years, discontinuing DMT rarely had a negative impact and improved quality of life.11,12 A retrospective meta-analysis of age-dependent efficacy of current DMTs predicted that DMT loses efficacy at age 53 years. In addition, higher efficacy DMT only outperforms lower efficacy DMT in patients aged < 40.5 years.13 Stability of disease and lack of relapses for ≥ 2 years also may be a positive predictor to safely discontinue DMT.14,15 The growing literature to support safe discontinuation of DMT makes this a more convincing strategy to avoid unnecessary costs associated with current DMTs. With an average age of 59 years for veterans with MS, this may be one of the largest areas of cost avoidance to consider.

Off-Label Use

Other potential ways to reduce DMT costs is to consider off-label treatments. The OLYMPUS trial studied off-label use of rituximab, an anti-CD20 antibody like ocrelizumab. It did not meet statistical significance for its primary endpoint; however, in a subgroup analysis, off-label use was found to be more effective in a population aged < 51 years.16 Other case reports and smaller scale studies also describe rituximab’s efficacy in MS.17,18 In 2018, the FDA approved the first rituximab biosimilar.19 Further competition from biosimilars likely will make rituximab an even more cost-effective choice when compared with ocrelizumab.

Alternate Dosing Regimens

Extended interval dosing of natalizumab has been studied, extending the standard infusion interval from every 4 weeks to 5- to 8-week intervals. One recent article compared these interval extensions and found that all extended intervals of up to 56 days did not increase new or enhancing lesions on MRI when compared with standard interval dosing.20 Another larger randomized trial is underway to evaluate efficacy and safety of extended interval dosing of natalizumab (NCT03689972). Utilization of this dosing may reduce natalizumab annual costs by up to 50%.

Safety Monitoring

DMF is an oral DMT on the VHA formulary with CFU. Since leukopenia is a known AE, baseline and quarterly monitoring of the complete blood count (CBC) is recommended for patients taking DMF. Additionally, DMF should be held if white blood cell count (WBC) falls below 2,000/mm3.21 There have been recent reports of death secondary to progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) among European patients taking DMF.22-24 This has raised concerns about adherence to recommended CBC monitoring in veterans taking DMF. The association of DMF and leukopenia has been evident since early clinical trials.25 Leukopenia in immunocompromised patients increases the risk of PML.

In the long-term extension study ENDORSE, 6% to 7% of patients continuing DMF had WBC counts of 3.0×109/L compared with 7% to 10% in the new to DMF group.26 In addition 6% to 8% of patients continuing DMF had lymphocyte counts of 0.5×109/L, compared with 5% to 9% in the new to DMF group. The cases of PML occurred in patients who had low lymphocyte counts over an extended period with no adjustment to DMF therapy, such as holding the drug until WBC counts returned to normal levels or stopping the drug. Discussion and review within VHA resulted in the recommendation for quarterly WBC monitoring criteria.

PBM and VA Center for Medication Safety (MedSafe) conducted a medication usage evaluation (MUE) on adherence to the WBC monitoring set forth in the CFU. Data collection began in fourth quarter of fiscal year (FY) 2015 with the most recent reporting period of fourth quarter of FY 2017. The Medication Utilization Evaluation Tool tracks patients with no reported WBC in 90 days and WBC < 2,000/mm3. Over the reporting period, 20% to 23% of patients have not received appropriate quarterly monitoring. Additionally, there have been 4 cases where the WBC decreased below the threshold limit. To ensure safe and effective use of DMF, it is important to adhere to the monitoring requirements set forth in the CFU.

Impact of REMS and Special Distribution

As DMTs increase in efficacy, there are often more risks associated with them. Some of these high-risk medications, including natalizumab and alemtuzumab, have REMS programs and/or have special distribution procedures. Although REMS are imperative for patient safety, the complexity of these programs can be difficult to navigate, which can create a barrier to access. The PBM helps to assist all sites with navigating and adhering to required actions to dispense and administer these medications through a national Special Handling Drugs Microsoft SharePoint site, which provides access to REMS forms and procurement information when drugs are dispensed from specialty pharmacies. Easing this process nationwide empowers more sites to be confident they can dispense specialty medications appropriately.

Clinical Pharmacists

The VHA is unique in its utilization of pharmacists in outpatient clinic settings. Utilization of an interdisciplinary team for medication management has been highly used in VHA for areas like primary care; however, pharmacist involvement in specialty areas is on the rise and MS is no exception. Pharmacists stationed in clinics, such as neurology or spinal cord injury, can impact care for veterans with MS. Interdisciplinary teams that include a pharmacist have been shown to increase patient adherence to DMTs.27 However, pharmacists often assist with medication education and monitoring, which adds an additional layer of safety to DMT treatment. At the VHA, pharmacists also can obtain a scope of practice that allows them to prescribe medications and increase access to care for veterans with MS.

Education

The VHA demonstrates how education on a disease state like MS can be distributed on a large, national scale through drug monographs, CFU, and Microsoft SharePoint sites. In addition, VHA has created the MS Centers of Excellence (MSCoE) that serve as a hub of specialized health care providers in all aspects of MS care.

A core function of the MSCoE is to provide education to both HCPs and patients. The MSCoE and its regional hubs support sites that may not have an HCP who specializes in MS by providing advice on DMT selection, how to obtain specialty medications, and monitoring that needs to be completed to ensure veterans’ safety. The MSCoE also has partnered with the National MS Society to hold a lecture series on topics in MS. This free series is available online to all HCPs who interact with patients who have MS and is a way that VA is extending its best practices and expertise beyond its own health care system. There also is a quarterly newsletter for veterans with MS that highlights new information on DMTs that can affect their care.

Conclusion

It is an exciting and challenging period in MS treatment. New DMTs are being approved and entering clinical trials at a rapid pace. These new DMT agents may offer increased efficacy, improvements in AE profiles, and the possibility of increased medication adherence—but often at a higher cost. The utilization of CFU and formulary management provides the ability to ensure the safe and appropriate use of medications by veterans, with a secondary outcome of controlling pharmacy expenditures.

The VHA had expenditures of $142,135,938 for DMT use in FY 2018. As the VHA sees the new contract prices for DMT in January 2020, we are reminded that costs will continue to rise with some pharmaceutical manufacturers implementing prices 8% to 11% higher than 2019 prices, when the consumer price index defines an increase of 1.0% for 2020 and 1.4% in 2021.28 It is imperative that the VHA formulary be managed judiciously and the necessary measures be in place for VHA practitioners to enable effective, safe and value-based care to the veteran population.

1. Gooch CL, Pracht E, Borenstein AR. The burden of neurological disease in the United States: a summary report and call to action. Ann Neurol. 2017;81(4):479-484.

2. Hartung DM, Bourdette DN, Ahmed SM, Whitham RH. The cost of multiple sclerosis drugs in the US and the pharmaceutical industry: too big to fail? [published correction appears in Neurology. 2015;85(19):1728]. Neurology. 2015;84(21):2185–2192.

3. San-Juan-Rodriguez A, Good CB, Heyman RA, Parekh N, Shrank WH, Hernandez I. Trends in prices, market share, and spending on self-administered disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis in Medicare Part D. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(11):1386-1390.

4. Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology. 2014;83(3):278-286.

5. Eriksson M, Andersen O, Runmarker B. Long-term follow up of patients with clinically isolated syndromes, relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis [published correction appears in Mult Scler. 2003;9(6):641]. Mult Scler. 2003;9(3):260-274.

6. Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162-173.

7. Cohen J, Belova A, Selmaj K, et al. Equivalence of generic glatiramer acetate in multiple sclerosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(12):1433-1441.

8. Selmaj K, Barkhof F, Belova AN, et al; GATE study group. Switching from branded to generic glatiramer acetate: 15-month GATE trial extension results. Mult Scler. 2017;23(14):1909-1917.

9. Aspinall SL, Sales MM, Good CB, et al. Pharmacy benefits management in the Veterans Health Administration revisited: a decade of advancements, 2004-2014. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(9):1058-1063.

10. Brown JWL, Coles A, Horakova D, et al. Association of initial disease-modifying therapy with later conversion to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. JAMA. 2019;321(2):175-187.

11. Hua LH, Harris H, Conway D, Thompson NR. Changes in patient-reported outcomes between continuers and discontinuers of disease modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis over age 60 [published correction appears in Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;30:293]. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;30:252-256.

12. Bsteh G, Feige J, Ehling R, et al. Discontinuation of disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis - Clinical outcome and prognostic factors. Mult Scler. 2017;23(9):1241-1248.

13. Weideman AM, Tapia-Maltos MA, Johnson K, Greenwood M, Bielekova B. Meta-analysis of the age-dependent efficacy of multiple sclerosis treatments. Front Neurol. 2017;8:577.

14. Kister I, Spelman T, Alroughani R, et al; MSBase Study Group. Discontinuing disease-modifying therapy in MS after a prolonged relapse-free period: a propensity score-matched study [published correction appears in J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019;90(4):e2]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(10):1133-1137.

15. Birnbaum G. Stopping disease-modifying therapy in nonrelapsing multiple sclerosis: experience from a clinical practice. Int J MS Care. 2017;19(1):11-14.

16. Hawker K, O’Connor P, Freedman MS, et al. Rituximab in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis: results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Ann Neurol. 2009;66(4):460-471.

17. Hauser SL, Waubant E, Arnold DL, et al. B-cell depletion with rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(7):676–688.

18. Alping P, Frisell T, Novakova L, et al. Rituximab versus fingolimod after natalizumab in multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(6):950–958.

19. Rituximab-abbs [package insert]. North Wales, PA: Teva Pharmaceuticals; 2018.

20. Zhovtis Ryerson L, Frohman TC, Foley J, et al. Extended interval dosing of natalizumab in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(8):885-889.

21. Dimethyl fumarate [package insert]. Cambridge, MA: Biogen Inc; 2015.

22. van Kester MS, Bouwes Bavinck JN, Quint KD. PML in Patients treated with dimethyl fumarate. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(6):583-584.

23. Nieuwkamp DJ, Murk JL, van Oosten BW. PML in patients treated with dimethyl fumarate. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(6):584.

24. Rosenkranz T, Novas M, Terborg C. PML in a patient with lymphocytopenia treated with dimethyl fumarate. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(15):1476-1478.

25. Longbrake EE, Cross AH. Dimethyl fumarate associated lymphopenia in clinical practice. Mult Scler. 2015;21(6):796-797.

26. Gold R, Arnold DL, Bar-Or A, et al. Long-term effects of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate in multiple sclerosis: Interim analysis of ENDORSE, a randomized extension study. Mult Scler. 2017;23(2):253–265.

27. Hanson RL, Habibi M, Khamo N, Abdou S, Stubbings J. Integrated clinical and specialty pharmacy practice model for management of patients with multiple sclerosis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(6):463-469.

28. Federal Planning Bureau. Consumer Price Index - Inflation forecasts. https://www.plan.be/databases/17-en-consumer+price+index+inflation+forecasts. Updated March 3, 2020. Accessed March 9, 2020.

Prior to the first approved disease modifying therapy (DMT) in the 1990s, treatment approaches for multiple sclerosis (MS) were not well understood. The discovery that MS was an immune mediated inflammatory disease paved the way for the treatments we know today. In 1993, interferon β‐1b became the first DMT for MS approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Approvals for interferon β‐1a as well as glatiramer acetate (GA) soon followed. Today, we consider these the mildest immunosuppressant DMTs; however, their success verified that suppressing the immune system had a positive effect on the MS disease process.

Following these approvals, the disease process in MS is now better understood. Recently approved therapies include monoclonal antibodies, which affect other immune pathways. Today, there are 14 approved DMTs (Table 1). Although the advent of these newer DMTs has revolutionized care for patients with MS, it has been accompanied by increasing costs for the agents. Direct medical costs associated with MS management, coupled with indirect costs from lost productivity, have been estimated to be $24.2 billion annually in the US.1 These increases have been seen across many levels of insurance coverage—private payer, Medicare, and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).2,3

The Figure demonstrates the cost increase that have been seen across VHA between 2004 and 2019 for the DMTs identified in Table 1. Indeed, this compound annual growth rate may be an underestimate because infusion therapies (eg, natalizumab, ocrelizumab, and alemtuzumab) are difficult to track as they may be dispensed directly via a Risk Evaluation Medication Strategy (REMS) program. According to the VHA Pharmacy Benefit Management Service (PBM), in September 2019, dimethyl fumarate (DMF) had the 13th highest total outpatient drug cost for the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), interferon β‐1a ranked 62nd and 83rd (prefilled pen and syringe, respectively), and GA 40 mg ranked 89th.

The DMT landscape has demonstrated significant price fluctuations and given rise to a class of medications that requires extensive oversight in terms of efficacy, safety, and cost minimization. The purpose of this article is to show how delivery of this specialty group of medications can be optimized with safety, efficacy, and cost value within a large health care system.

Factors Impacting DMT Use

Recent changes to MS typing have impacted utilization of DMTs. Traditionally, there were 4 subtypes of MS: relapsing remitting (RRMS), secondary progressive (SPMS), progressive relapsing (PRMS), and primary progressive (PPMS). These subtypes are now viewed more broadly and grouped as either relapsing or progressive. The traditional subtypes fall under these broader definitions. Additionally, SPMS has been broken into active SPMS, characterized by continued worsening of disability unrelated to acute relapses, superimposed with activity that can be seen on magnetic resonance images (MRIs), and nonactive SPMS, which has the same disability progression as active SPMS but without MRI-visible activity.4-6 In 2019, these supplementary designations to SPMS made their first appearance in FDA-approved indications. All existing DMTs now include this terminology in their labelling and are indicated in active SPMS. There remain no DMTs that treat nonactive SPMS.

The current landscape of DMTs is highly varied in method of administration, risks, and benefits. As efficacy of these medications often is marked by how well they can prevent the immune system from attacking myelin, an inverse relationship between safety and efficacy results. The standard treatment outcomes in MS have evolved over time. The following are the commonly used primary outcomes in clinical trials: relapse reduction; increased time between relapses; decreased severity of relapses; prevention or extend time to disability milestones as measured by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) and other disability measures; prevention or extension of time to onset of secondary progressive disease; prevention or reduction of the number and size of new and enhancing lesions on MRI; and limitation of overall MRI lesion burden in the central nervous system (CNS).

Newer treatment outcomes employed in more recent trials include: measures of axonal damage, CNS atrophy, evidence of microscopic disease via conventional MRI and advanced imaging modalities, biomarkers associated with inflammatory disease activity and neurodegeneration in MS, and the use of no evidence of disease activity (NEDA). These outcomes also must be evaluated by the safety concerns of each agent. Short- and long-term safety are critical factors in the selection of DMTs for MS. The injectable therapies for MS (interferon β‐1a, interferon β‐1b, and GA) have established long-term safety profiles from > 20 years of continuous use. The long-term safety profiles of oral immunomodulatory agents and monoclonal antibodies for these drugs in MS have yet to be determined. Safety concerns associated with some therapies and added requirements for safety monitoring may increase the complexity of a therapeutic selection.

Current cost minimization strategies for DMT include limiting DMT agents on formularies, tier systems that incentivize patients/prescribers to select the lowest priced agents on the formulary, negotiating arrangements with manufacturers to freeze prices or provide discounts in exchange for a priority position in the formulary, and requiring prior authorization to initiate or switch therapy. The use of generic medications and interchange to these agents from a brand name formulation can help reduce expense. Several of these strategies have been implemented in VHA.

Disease-Modifying Therapies

In 2019, 18,645 veterans with MS had either a MS-specific DMT or ≥ 1 annual encounters with a primary diagnosis of MS. Of this population, 4,720 were female and 13,357 were service connected according to VA data. About 50% of veterans with MS take a DMT. This percentage has remained stable over the past decade (Table 2). Although it appears the number of unique veterans prescribed an outpatient DMT is decreasing, this does not include the growing use of infused DMTs or DMTs obtained through the Veterans Choice Program (VCP)/Community Care (CC).

The overall outpatient pharmacy costs for veterans have remained constant despite the reduction in outpatient pharmacy prescription numbers. This may be due to increases in DMT cost to the VHA and the use of more expensive oral agents over the previously used platform injection DMTs.

Generic Conversion

GA is available in 20 mg daily and 40 mg3 times weekly subcutaneous injection dosing. The first evidence of clinical efficacy for a generic formulation for GA was evaluated by the GATE trial.7 This trial was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, active- and placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Eligible participants were randomized to receive daily SC injection for 9 months of 20 mg generic GA (n = 5,353), 20 mg brand GA (n = 5,357), or placebo (n = 584). The primary endpoint was the mean number of gadolinium (Gd1) lesions visible on MRIs during months 7, 8, and 9, which were significantly reduced in the combined GA-treated group and in each GA group individually when compared with the placebo group, confirming the study sensitivity (ie, GA was effective under the conditions of the study). Tolerability (including injection site reactions) and safety (incidence, spectrum, and severity of adverse events [AEs]) were similar in the generic and brand GA groups. These results demonstrated that generic and brand GA had equivalent efficacy, tolerability, and safety over a 9-month period.7

Results of a 15-month extension of the study were presented in 2015 and showed similar efficacy, safety, and tolerability in participants treated with generic GA for 2 years and patients switched from brand to generic GA.8 Multiple shifts for GA occurred, most notably the conversion from branded Copaxone (Teva Pharmaceutical Industries) to generic Glatopa (Sandoz). Subsequently, Sandoz released a generic 40 mg 3 times weekly formulation. Additionally, Mylan entered the generic GA market. With 3 competing manufacturers, internal data from the VHA indicated that it was able to negotiate a single source contract for this medication that provided a savings of $32,088,904.69 between September 2016 and May 2019.

The impact of generic conversions is just being realized. Soon, patents will begin to expire for oral DMTs, leading to an expected growth of generic alternatives. Already the FDA has approved 4 generic alternatives for teriflunomide, 3 for fingolimod (with 13 tentative approvals), and 15 generic alternatives for dimethyl fumarate (DMF). Implementation of therapeutic interchanges will be pursued by VHA as clinically supported by evidence.

Criteria for Use

PBM supports utilizing criteria to help guide providers on DMT options and promote safe, effective, and value-based selection of a DMT. The PBM creates monographs and criteria for use (CFU) for new medications. The monograph contains a literature evaluation of all studies available to date that concern both safety and efficacy of the new medication. Therapeutic alternatives also are presented and assessed for key elements that may determine the most safe and effective use. Additional safety areas for the new medications such as look-alike, sound-alike potential, special populations use (ie, those who are pregnant, the elderly, and those with liver or renal dysfunction), and drug-drug interactions are presented. Lastly, and possibly most importantly in an ever-growing growing world of DMTs, the monograph describes a reasonable place in therapy for the new DMT.

CFU are additional guidance for some DMTs. The development of CFU are based on several questions that arise during the monograph development for a DMT. These include, but are not limited to:

- Are there safety concerns that require the drug to receive a review to ensure safe prescribing (eg, agents with REMS programs, or safety concerns in specific populations)?

- Does the drug require a specialty provider type with knowledge and experience in those disease states to ensure appropriate and safe prescribing (eg restricted to infectious diseases)?

- Do VHA or non-VHA guidelines suggest alternative therapy be used prior to the agent?

- Is a review deemed necessary to ensure the preferred agent is used first (eg, second-line therapy)?

The CFU defines parameters of drug use consistent with high quality and evidence-based patient care. CFUs also serve as a basis for monitoring local, regional, and national patterns of pharmacologic care and help guide health care providers (HCPs) on appropriate use of medication.

CFUs are designed to ensure the HCP is safely starting a medication that has evidence for efficacy for their patient. For example, alemtuzumab is a high-risk, high-efficacy DMT. The alemtuzumab CFU acknowledges this by having exclusion criteria that prevent a veteran at high risk (ie, on another immunosuppressant) from being exposed to severe AEs (ie, severe leukopenia) that are associated with the medication. On the other hand, the inclusion criteria recognize the benefits of alemtuzumab and allows those with highly active MS who have failed other DMTs to receive the medication.

The drug monograph and CFU process is an important part of VHA efforts to optimize patient care. After a draft version is developed, HCPs can provide feedback on the exclusion/inclusion criteria and describe how they anticipate using the medication in their practice. This insight can be beneficial for MS treatment as diverse HCPs may have distinct viewpoints on how DMTs should be started. Pharmacists and physicians on a national level then discuss and decide together what to include in the final drafts of the drug monograph and CFU. Final documents are disseminated to all sites, which encourages consistent practices across the VHA.9 These documents are reviewed on a regular basis and updated as needed based on available literature evidence.

It is well accepted that early use of DMT correlates with lower accumulated long-term disability.10 However, discontinuation of DMT should be treated with equal importance. This benefits the patient by reducing their risk of AEs from DMTs and provides cost savings. Age and disease stability are factors to consider for DMT discontinuation. In a study with patients aged > 45 years and another with patients aged > 60 years, discontinuing DMT rarely had a negative impact and improved quality of life.11,12 A retrospective meta-analysis of age-dependent efficacy of current DMTs predicted that DMT loses efficacy at age 53 years. In addition, higher efficacy DMT only outperforms lower efficacy DMT in patients aged < 40.5 years.13 Stability of disease and lack of relapses for ≥ 2 years also may be a positive predictor to safely discontinue DMT.14,15 The growing literature to support safe discontinuation of DMT makes this a more convincing strategy to avoid unnecessary costs associated with current DMTs. With an average age of 59 years for veterans with MS, this may be one of the largest areas of cost avoidance to consider.

Off-Label Use

Other potential ways to reduce DMT costs is to consider off-label treatments. The OLYMPUS trial studied off-label use of rituximab, an anti-CD20 antibody like ocrelizumab. It did not meet statistical significance for its primary endpoint; however, in a subgroup analysis, off-label use was found to be more effective in a population aged < 51 years.16 Other case reports and smaller scale studies also describe rituximab’s efficacy in MS.17,18 In 2018, the FDA approved the first rituximab biosimilar.19 Further competition from biosimilars likely will make rituximab an even more cost-effective choice when compared with ocrelizumab.

Alternate Dosing Regimens

Extended interval dosing of natalizumab has been studied, extending the standard infusion interval from every 4 weeks to 5- to 8-week intervals. One recent article compared these interval extensions and found that all extended intervals of up to 56 days did not increase new or enhancing lesions on MRI when compared with standard interval dosing.20 Another larger randomized trial is underway to evaluate efficacy and safety of extended interval dosing of natalizumab (NCT03689972). Utilization of this dosing may reduce natalizumab annual costs by up to 50%.

Safety Monitoring

DMF is an oral DMT on the VHA formulary with CFU. Since leukopenia is a known AE, baseline and quarterly monitoring of the complete blood count (CBC) is recommended for patients taking DMF. Additionally, DMF should be held if white blood cell count (WBC) falls below 2,000/mm3.21 There have been recent reports of death secondary to progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) among European patients taking DMF.22-24 This has raised concerns about adherence to recommended CBC monitoring in veterans taking DMF. The association of DMF and leukopenia has been evident since early clinical trials.25 Leukopenia in immunocompromised patients increases the risk of PML.

In the long-term extension study ENDORSE, 6% to 7% of patients continuing DMF had WBC counts of 3.0×109/L compared with 7% to 10% in the new to DMF group.26 In addition 6% to 8% of patients continuing DMF had lymphocyte counts of 0.5×109/L, compared with 5% to 9% in the new to DMF group. The cases of PML occurred in patients who had low lymphocyte counts over an extended period with no adjustment to DMF therapy, such as holding the drug until WBC counts returned to normal levels or stopping the drug. Discussion and review within VHA resulted in the recommendation for quarterly WBC monitoring criteria.

PBM and VA Center for Medication Safety (MedSafe) conducted a medication usage evaluation (MUE) on adherence to the WBC monitoring set forth in the CFU. Data collection began in fourth quarter of fiscal year (FY) 2015 with the most recent reporting period of fourth quarter of FY 2017. The Medication Utilization Evaluation Tool tracks patients with no reported WBC in 90 days and WBC < 2,000/mm3. Over the reporting period, 20% to 23% of patients have not received appropriate quarterly monitoring. Additionally, there have been 4 cases where the WBC decreased below the threshold limit. To ensure safe and effective use of DMF, it is important to adhere to the monitoring requirements set forth in the CFU.

Impact of REMS and Special Distribution

As DMTs increase in efficacy, there are often more risks associated with them. Some of these high-risk medications, including natalizumab and alemtuzumab, have REMS programs and/or have special distribution procedures. Although REMS are imperative for patient safety, the complexity of these programs can be difficult to navigate, which can create a barrier to access. The PBM helps to assist all sites with navigating and adhering to required actions to dispense and administer these medications through a national Special Handling Drugs Microsoft SharePoint site, which provides access to REMS forms and procurement information when drugs are dispensed from specialty pharmacies. Easing this process nationwide empowers more sites to be confident they can dispense specialty medications appropriately.

Clinical Pharmacists

The VHA is unique in its utilization of pharmacists in outpatient clinic settings. Utilization of an interdisciplinary team for medication management has been highly used in VHA for areas like primary care; however, pharmacist involvement in specialty areas is on the rise and MS is no exception. Pharmacists stationed in clinics, such as neurology or spinal cord injury, can impact care for veterans with MS. Interdisciplinary teams that include a pharmacist have been shown to increase patient adherence to DMTs.27 However, pharmacists often assist with medication education and monitoring, which adds an additional layer of safety to DMT treatment. At the VHA, pharmacists also can obtain a scope of practice that allows them to prescribe medications and increase access to care for veterans with MS.

Education

The VHA demonstrates how education on a disease state like MS can be distributed on a large, national scale through drug monographs, CFU, and Microsoft SharePoint sites. In addition, VHA has created the MS Centers of Excellence (MSCoE) that serve as a hub of specialized health care providers in all aspects of MS care.

A core function of the MSCoE is to provide education to both HCPs and patients. The MSCoE and its regional hubs support sites that may not have an HCP who specializes in MS by providing advice on DMT selection, how to obtain specialty medications, and monitoring that needs to be completed to ensure veterans’ safety. The MSCoE also has partnered with the National MS Society to hold a lecture series on topics in MS. This free series is available online to all HCPs who interact with patients who have MS and is a way that VA is extending its best practices and expertise beyond its own health care system. There also is a quarterly newsletter for veterans with MS that highlights new information on DMTs that can affect their care.

Conclusion

It is an exciting and challenging period in MS treatment. New DMTs are being approved and entering clinical trials at a rapid pace. These new DMT agents may offer increased efficacy, improvements in AE profiles, and the possibility of increased medication adherence—but often at a higher cost. The utilization of CFU and formulary management provides the ability to ensure the safe and appropriate use of medications by veterans, with a secondary outcome of controlling pharmacy expenditures.

The VHA had expenditures of $142,135,938 for DMT use in FY 2018. As the VHA sees the new contract prices for DMT in January 2020, we are reminded that costs will continue to rise with some pharmaceutical manufacturers implementing prices 8% to 11% higher than 2019 prices, when the consumer price index defines an increase of 1.0% for 2020 and 1.4% in 2021.28 It is imperative that the VHA formulary be managed judiciously and the necessary measures be in place for VHA practitioners to enable effective, safe and value-based care to the veteran population.

Prior to the first approved disease modifying therapy (DMT) in the 1990s, treatment approaches for multiple sclerosis (MS) were not well understood. The discovery that MS was an immune mediated inflammatory disease paved the way for the treatments we know today. In 1993, interferon β‐1b became the first DMT for MS approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Approvals for interferon β‐1a as well as glatiramer acetate (GA) soon followed. Today, we consider these the mildest immunosuppressant DMTs; however, their success verified that suppressing the immune system had a positive effect on the MS disease process.

Following these approvals, the disease process in MS is now better understood. Recently approved therapies include monoclonal antibodies, which affect other immune pathways. Today, there are 14 approved DMTs (Table 1). Although the advent of these newer DMTs has revolutionized care for patients with MS, it has been accompanied by increasing costs for the agents. Direct medical costs associated with MS management, coupled with indirect costs from lost productivity, have been estimated to be $24.2 billion annually in the US.1 These increases have been seen across many levels of insurance coverage—private payer, Medicare, and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).2,3

The Figure demonstrates the cost increase that have been seen across VHA between 2004 and 2019 for the DMTs identified in Table 1. Indeed, this compound annual growth rate may be an underestimate because infusion therapies (eg, natalizumab, ocrelizumab, and alemtuzumab) are difficult to track as they may be dispensed directly via a Risk Evaluation Medication Strategy (REMS) program. According to the VHA Pharmacy Benefit Management Service (PBM), in September 2019, dimethyl fumarate (DMF) had the 13th highest total outpatient drug cost for the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), interferon β‐1a ranked 62nd and 83rd (prefilled pen and syringe, respectively), and GA 40 mg ranked 89th.

The DMT landscape has demonstrated significant price fluctuations and given rise to a class of medications that requires extensive oversight in terms of efficacy, safety, and cost minimization. The purpose of this article is to show how delivery of this specialty group of medications can be optimized with safety, efficacy, and cost value within a large health care system.

Factors Impacting DMT Use

Recent changes to MS typing have impacted utilization of DMTs. Traditionally, there were 4 subtypes of MS: relapsing remitting (RRMS), secondary progressive (SPMS), progressive relapsing (PRMS), and primary progressive (PPMS). These subtypes are now viewed more broadly and grouped as either relapsing or progressive. The traditional subtypes fall under these broader definitions. Additionally, SPMS has been broken into active SPMS, characterized by continued worsening of disability unrelated to acute relapses, superimposed with activity that can be seen on magnetic resonance images (MRIs), and nonactive SPMS, which has the same disability progression as active SPMS but without MRI-visible activity.4-6 In 2019, these supplementary designations to SPMS made their first appearance in FDA-approved indications. All existing DMTs now include this terminology in their labelling and are indicated in active SPMS. There remain no DMTs that treat nonactive SPMS.

The current landscape of DMTs is highly varied in method of administration, risks, and benefits. As efficacy of these medications often is marked by how well they can prevent the immune system from attacking myelin, an inverse relationship between safety and efficacy results. The standard treatment outcomes in MS have evolved over time. The following are the commonly used primary outcomes in clinical trials: relapse reduction; increased time between relapses; decreased severity of relapses; prevention or extend time to disability milestones as measured by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) and other disability measures; prevention or extension of time to onset of secondary progressive disease; prevention or reduction of the number and size of new and enhancing lesions on MRI; and limitation of overall MRI lesion burden in the central nervous system (CNS).

Newer treatment outcomes employed in more recent trials include: measures of axonal damage, CNS atrophy, evidence of microscopic disease via conventional MRI and advanced imaging modalities, biomarkers associated with inflammatory disease activity and neurodegeneration in MS, and the use of no evidence of disease activity (NEDA). These outcomes also must be evaluated by the safety concerns of each agent. Short- and long-term safety are critical factors in the selection of DMTs for MS. The injectable therapies for MS (interferon β‐1a, interferon β‐1b, and GA) have established long-term safety profiles from > 20 years of continuous use. The long-term safety profiles of oral immunomodulatory agents and monoclonal antibodies for these drugs in MS have yet to be determined. Safety concerns associated with some therapies and added requirements for safety monitoring may increase the complexity of a therapeutic selection.

Current cost minimization strategies for DMT include limiting DMT agents on formularies, tier systems that incentivize patients/prescribers to select the lowest priced agents on the formulary, negotiating arrangements with manufacturers to freeze prices or provide discounts in exchange for a priority position in the formulary, and requiring prior authorization to initiate or switch therapy. The use of generic medications and interchange to these agents from a brand name formulation can help reduce expense. Several of these strategies have been implemented in VHA.

Disease-Modifying Therapies

In 2019, 18,645 veterans with MS had either a MS-specific DMT or ≥ 1 annual encounters with a primary diagnosis of MS. Of this population, 4,720 were female and 13,357 were service connected according to VA data. About 50% of veterans with MS take a DMT. This percentage has remained stable over the past decade (Table 2). Although it appears the number of unique veterans prescribed an outpatient DMT is decreasing, this does not include the growing use of infused DMTs or DMTs obtained through the Veterans Choice Program (VCP)/Community Care (CC).

The overall outpatient pharmacy costs for veterans have remained constant despite the reduction in outpatient pharmacy prescription numbers. This may be due to increases in DMT cost to the VHA and the use of more expensive oral agents over the previously used platform injection DMTs.

Generic Conversion

GA is available in 20 mg daily and 40 mg3 times weekly subcutaneous injection dosing. The first evidence of clinical efficacy for a generic formulation for GA was evaluated by the GATE trial.7 This trial was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, active- and placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Eligible participants were randomized to receive daily SC injection for 9 months of 20 mg generic GA (n = 5,353), 20 mg brand GA (n = 5,357), or placebo (n = 584). The primary endpoint was the mean number of gadolinium (Gd1) lesions visible on MRIs during months 7, 8, and 9, which were significantly reduced in the combined GA-treated group and in each GA group individually when compared with the placebo group, confirming the study sensitivity (ie, GA was effective under the conditions of the study). Tolerability (including injection site reactions) and safety (incidence, spectrum, and severity of adverse events [AEs]) were similar in the generic and brand GA groups. These results demonstrated that generic and brand GA had equivalent efficacy, tolerability, and safety over a 9-month period.7

Results of a 15-month extension of the study were presented in 2015 and showed similar efficacy, safety, and tolerability in participants treated with generic GA for 2 years and patients switched from brand to generic GA.8 Multiple shifts for GA occurred, most notably the conversion from branded Copaxone (Teva Pharmaceutical Industries) to generic Glatopa (Sandoz). Subsequently, Sandoz released a generic 40 mg 3 times weekly formulation. Additionally, Mylan entered the generic GA market. With 3 competing manufacturers, internal data from the VHA indicated that it was able to negotiate a single source contract for this medication that provided a savings of $32,088,904.69 between September 2016 and May 2019.

The impact of generic conversions is just being realized. Soon, patents will begin to expire for oral DMTs, leading to an expected growth of generic alternatives. Already the FDA has approved 4 generic alternatives for teriflunomide, 3 for fingolimod (with 13 tentative approvals), and 15 generic alternatives for dimethyl fumarate (DMF). Implementation of therapeutic interchanges will be pursued by VHA as clinically supported by evidence.

Criteria for Use

PBM supports utilizing criteria to help guide providers on DMT options and promote safe, effective, and value-based selection of a DMT. The PBM creates monographs and criteria for use (CFU) for new medications. The monograph contains a literature evaluation of all studies available to date that concern both safety and efficacy of the new medication. Therapeutic alternatives also are presented and assessed for key elements that may determine the most safe and effective use. Additional safety areas for the new medications such as look-alike, sound-alike potential, special populations use (ie, those who are pregnant, the elderly, and those with liver or renal dysfunction), and drug-drug interactions are presented. Lastly, and possibly most importantly in an ever-growing growing world of DMTs, the monograph describes a reasonable place in therapy for the new DMT.

CFU are additional guidance for some DMTs. The development of CFU are based on several questions that arise during the monograph development for a DMT. These include, but are not limited to:

- Are there safety concerns that require the drug to receive a review to ensure safe prescribing (eg, agents with REMS programs, or safety concerns in specific populations)?

- Does the drug require a specialty provider type with knowledge and experience in those disease states to ensure appropriate and safe prescribing (eg restricted to infectious diseases)?

- Do VHA or non-VHA guidelines suggest alternative therapy be used prior to the agent?

- Is a review deemed necessary to ensure the preferred agent is used first (eg, second-line therapy)?

The CFU defines parameters of drug use consistent with high quality and evidence-based patient care. CFUs also serve as a basis for monitoring local, regional, and national patterns of pharmacologic care and help guide health care providers (HCPs) on appropriate use of medication.

CFUs are designed to ensure the HCP is safely starting a medication that has evidence for efficacy for their patient. For example, alemtuzumab is a high-risk, high-efficacy DMT. The alemtuzumab CFU acknowledges this by having exclusion criteria that prevent a veteran at high risk (ie, on another immunosuppressant) from being exposed to severe AEs (ie, severe leukopenia) that are associated with the medication. On the other hand, the inclusion criteria recognize the benefits of alemtuzumab and allows those with highly active MS who have failed other DMTs to receive the medication.

The drug monograph and CFU process is an important part of VHA efforts to optimize patient care. After a draft version is developed, HCPs can provide feedback on the exclusion/inclusion criteria and describe how they anticipate using the medication in their practice. This insight can be beneficial for MS treatment as diverse HCPs may have distinct viewpoints on how DMTs should be started. Pharmacists and physicians on a national level then discuss and decide together what to include in the final drafts of the drug monograph and CFU. Final documents are disseminated to all sites, which encourages consistent practices across the VHA.9 These documents are reviewed on a regular basis and updated as needed based on available literature evidence.

It is well accepted that early use of DMT correlates with lower accumulated long-term disability.10 However, discontinuation of DMT should be treated with equal importance. This benefits the patient by reducing their risk of AEs from DMTs and provides cost savings. Age and disease stability are factors to consider for DMT discontinuation. In a study with patients aged > 45 years and another with patients aged > 60 years, discontinuing DMT rarely had a negative impact and improved quality of life.11,12 A retrospective meta-analysis of age-dependent efficacy of current DMTs predicted that DMT loses efficacy at age 53 years. In addition, higher efficacy DMT only outperforms lower efficacy DMT in patients aged < 40.5 years.13 Stability of disease and lack of relapses for ≥ 2 years also may be a positive predictor to safely discontinue DMT.14,15 The growing literature to support safe discontinuation of DMT makes this a more convincing strategy to avoid unnecessary costs associated with current DMTs. With an average age of 59 years for veterans with MS, this may be one of the largest areas of cost avoidance to consider.

Off-Label Use

Other potential ways to reduce DMT costs is to consider off-label treatments. The OLYMPUS trial studied off-label use of rituximab, an anti-CD20 antibody like ocrelizumab. It did not meet statistical significance for its primary endpoint; however, in a subgroup analysis, off-label use was found to be more effective in a population aged < 51 years.16 Other case reports and smaller scale studies also describe rituximab’s efficacy in MS.17,18 In 2018, the FDA approved the first rituximab biosimilar.19 Further competition from biosimilars likely will make rituximab an even more cost-effective choice when compared with ocrelizumab.

Alternate Dosing Regimens

Extended interval dosing of natalizumab has been studied, extending the standard infusion interval from every 4 weeks to 5- to 8-week intervals. One recent article compared these interval extensions and found that all extended intervals of up to 56 days did not increase new or enhancing lesions on MRI when compared with standard interval dosing.20 Another larger randomized trial is underway to evaluate efficacy and safety of extended interval dosing of natalizumab (NCT03689972). Utilization of this dosing may reduce natalizumab annual costs by up to 50%.

Safety Monitoring

DMF is an oral DMT on the VHA formulary with CFU. Since leukopenia is a known AE, baseline and quarterly monitoring of the complete blood count (CBC) is recommended for patients taking DMF. Additionally, DMF should be held if white blood cell count (WBC) falls below 2,000/mm3.21 There have been recent reports of death secondary to progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) among European patients taking DMF.22-24 This has raised concerns about adherence to recommended CBC monitoring in veterans taking DMF. The association of DMF and leukopenia has been evident since early clinical trials.25 Leukopenia in immunocompromised patients increases the risk of PML.

In the long-term extension study ENDORSE, 6% to 7% of patients continuing DMF had WBC counts of 3.0×109/L compared with 7% to 10% in the new to DMF group.26 In addition 6% to 8% of patients continuing DMF had lymphocyte counts of 0.5×109/L, compared with 5% to 9% in the new to DMF group. The cases of PML occurred in patients who had low lymphocyte counts over an extended period with no adjustment to DMF therapy, such as holding the drug until WBC counts returned to normal levels or stopping the drug. Discussion and review within VHA resulted in the recommendation for quarterly WBC monitoring criteria.

PBM and VA Center for Medication Safety (MedSafe) conducted a medication usage evaluation (MUE) on adherence to the WBC monitoring set forth in the CFU. Data collection began in fourth quarter of fiscal year (FY) 2015 with the most recent reporting period of fourth quarter of FY 2017. The Medication Utilization Evaluation Tool tracks patients with no reported WBC in 90 days and WBC < 2,000/mm3. Over the reporting period, 20% to 23% of patients have not received appropriate quarterly monitoring. Additionally, there have been 4 cases where the WBC decreased below the threshold limit. To ensure safe and effective use of DMF, it is important to adhere to the monitoring requirements set forth in the CFU.

Impact of REMS and Special Distribution

As DMTs increase in efficacy, there are often more risks associated with them. Some of these high-risk medications, including natalizumab and alemtuzumab, have REMS programs and/or have special distribution procedures. Although REMS are imperative for patient safety, the complexity of these programs can be difficult to navigate, which can create a barrier to access. The PBM helps to assist all sites with navigating and adhering to required actions to dispense and administer these medications through a national Special Handling Drugs Microsoft SharePoint site, which provides access to REMS forms and procurement information when drugs are dispensed from specialty pharmacies. Easing this process nationwide empowers more sites to be confident they can dispense specialty medications appropriately.

Clinical Pharmacists

The VHA is unique in its utilization of pharmacists in outpatient clinic settings. Utilization of an interdisciplinary team for medication management has been highly used in VHA for areas like primary care; however, pharmacist involvement in specialty areas is on the rise and MS is no exception. Pharmacists stationed in clinics, such as neurology or spinal cord injury, can impact care for veterans with MS. Interdisciplinary teams that include a pharmacist have been shown to increase patient adherence to DMTs.27 However, pharmacists often assist with medication education and monitoring, which adds an additional layer of safety to DMT treatment. At the VHA, pharmacists also can obtain a scope of practice that allows them to prescribe medications and increase access to care for veterans with MS.

Education

The VHA demonstrates how education on a disease state like MS can be distributed on a large, national scale through drug monographs, CFU, and Microsoft SharePoint sites. In addition, VHA has created the MS Centers of Excellence (MSCoE) that serve as a hub of specialized health care providers in all aspects of MS care.

A core function of the MSCoE is to provide education to both HCPs and patients. The MSCoE and its regional hubs support sites that may not have an HCP who specializes in MS by providing advice on DMT selection, how to obtain specialty medications, and monitoring that needs to be completed to ensure veterans’ safety. The MSCoE also has partnered with the National MS Society to hold a lecture series on topics in MS. This free series is available online to all HCPs who interact with patients who have MS and is a way that VA is extending its best practices and expertise beyond its own health care system. There also is a quarterly newsletter for veterans with MS that highlights new information on DMTs that can affect their care.

Conclusion

It is an exciting and challenging period in MS treatment. New DMTs are being approved and entering clinical trials at a rapid pace. These new DMT agents may offer increased efficacy, improvements in AE profiles, and the possibility of increased medication adherence—but often at a higher cost. The utilization of CFU and formulary management provides the ability to ensure the safe and appropriate use of medications by veterans, with a secondary outcome of controlling pharmacy expenditures.

The VHA had expenditures of $142,135,938 for DMT use in FY 2018. As the VHA sees the new contract prices for DMT in January 2020, we are reminded that costs will continue to rise with some pharmaceutical manufacturers implementing prices 8% to 11% higher than 2019 prices, when the consumer price index defines an increase of 1.0% for 2020 and 1.4% in 2021.28 It is imperative that the VHA formulary be managed judiciously and the necessary measures be in place for VHA practitioners to enable effective, safe and value-based care to the veteran population.

1. Gooch CL, Pracht E, Borenstein AR. The burden of neurological disease in the United States: a summary report and call to action. Ann Neurol. 2017;81(4):479-484.

2. Hartung DM, Bourdette DN, Ahmed SM, Whitham RH. The cost of multiple sclerosis drugs in the US and the pharmaceutical industry: too big to fail? [published correction appears in Neurology. 2015;85(19):1728]. Neurology. 2015;84(21):2185–2192.

3. San-Juan-Rodriguez A, Good CB, Heyman RA, Parekh N, Shrank WH, Hernandez I. Trends in prices, market share, and spending on self-administered disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis in Medicare Part D. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(11):1386-1390.

4. Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology. 2014;83(3):278-286.

5. Eriksson M, Andersen O, Runmarker B. Long-term follow up of patients with clinically isolated syndromes, relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis [published correction appears in Mult Scler. 2003;9(6):641]. Mult Scler. 2003;9(3):260-274.

6. Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162-173.

7. Cohen J, Belova A, Selmaj K, et al. Equivalence of generic glatiramer acetate in multiple sclerosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(12):1433-1441.

8. Selmaj K, Barkhof F, Belova AN, et al; GATE study group. Switching from branded to generic glatiramer acetate: 15-month GATE trial extension results. Mult Scler. 2017;23(14):1909-1917.

9. Aspinall SL, Sales MM, Good CB, et al. Pharmacy benefits management in the Veterans Health Administration revisited: a decade of advancements, 2004-2014. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(9):1058-1063.

10. Brown JWL, Coles A, Horakova D, et al. Association of initial disease-modifying therapy with later conversion to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. JAMA. 2019;321(2):175-187.

11. Hua LH, Harris H, Conway D, Thompson NR. Changes in patient-reported outcomes between continuers and discontinuers of disease modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis over age 60 [published correction appears in Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;30:293]. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;30:252-256.

12. Bsteh G, Feige J, Ehling R, et al. Discontinuation of disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis - Clinical outcome and prognostic factors. Mult Scler. 2017;23(9):1241-1248.

13. Weideman AM, Tapia-Maltos MA, Johnson K, Greenwood M, Bielekova B. Meta-analysis of the age-dependent efficacy of multiple sclerosis treatments. Front Neurol. 2017;8:577.

14. Kister I, Spelman T, Alroughani R, et al; MSBase Study Group. Discontinuing disease-modifying therapy in MS after a prolonged relapse-free period: a propensity score-matched study [published correction appears in J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019;90(4):e2]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(10):1133-1137.

15. Birnbaum G. Stopping disease-modifying therapy in nonrelapsing multiple sclerosis: experience from a clinical practice. Int J MS Care. 2017;19(1):11-14.

16. Hawker K, O’Connor P, Freedman MS, et al. Rituximab in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis: results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Ann Neurol. 2009;66(4):460-471.

17. Hauser SL, Waubant E, Arnold DL, et al. B-cell depletion with rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(7):676–688.

18. Alping P, Frisell T, Novakova L, et al. Rituximab versus fingolimod after natalizumab in multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(6):950–958.

19. Rituximab-abbs [package insert]. North Wales, PA: Teva Pharmaceuticals; 2018.

20. Zhovtis Ryerson L, Frohman TC, Foley J, et al. Extended interval dosing of natalizumab in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(8):885-889.

21. Dimethyl fumarate [package insert]. Cambridge, MA: Biogen Inc; 2015.

22. van Kester MS, Bouwes Bavinck JN, Quint KD. PML in Patients treated with dimethyl fumarate. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(6):583-584.

23. Nieuwkamp DJ, Murk JL, van Oosten BW. PML in patients treated with dimethyl fumarate. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(6):584.

24. Rosenkranz T, Novas M, Terborg C. PML in a patient with lymphocytopenia treated with dimethyl fumarate. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(15):1476-1478.

25. Longbrake EE, Cross AH. Dimethyl fumarate associated lymphopenia in clinical practice. Mult Scler. 2015;21(6):796-797.

26. Gold R, Arnold DL, Bar-Or A, et al. Long-term effects of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate in multiple sclerosis: Interim analysis of ENDORSE, a randomized extension study. Mult Scler. 2017;23(2):253–265.

27. Hanson RL, Habibi M, Khamo N, Abdou S, Stubbings J. Integrated clinical and specialty pharmacy practice model for management of patients with multiple sclerosis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(6):463-469.

28. Federal Planning Bureau. Consumer Price Index - Inflation forecasts. https://www.plan.be/databases/17-en-consumer+price+index+inflation+forecasts. Updated March 3, 2020. Accessed March 9, 2020.

1. Gooch CL, Pracht E, Borenstein AR. The burden of neurological disease in the United States: a summary report and call to action. Ann Neurol. 2017;81(4):479-484.

2. Hartung DM, Bourdette DN, Ahmed SM, Whitham RH. The cost of multiple sclerosis drugs in the US and the pharmaceutical industry: too big to fail? [published correction appears in Neurology. 2015;85(19):1728]. Neurology. 2015;84(21):2185–2192.

3. San-Juan-Rodriguez A, Good CB, Heyman RA, Parekh N, Shrank WH, Hernandez I. Trends in prices, market share, and spending on self-administered disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis in Medicare Part D. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(11):1386-1390.

4. Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology. 2014;83(3):278-286.

5. Eriksson M, Andersen O, Runmarker B. Long-term follow up of patients with clinically isolated syndromes, relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis [published correction appears in Mult Scler. 2003;9(6):641]. Mult Scler. 2003;9(3):260-274.

6. Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162-173.

7. Cohen J, Belova A, Selmaj K, et al. Equivalence of generic glatiramer acetate in multiple sclerosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(12):1433-1441.

8. Selmaj K, Barkhof F, Belova AN, et al; GATE study group. Switching from branded to generic glatiramer acetate: 15-month GATE trial extension results. Mult Scler. 2017;23(14):1909-1917.

9. Aspinall SL, Sales MM, Good CB, et al. Pharmacy benefits management in the Veterans Health Administration revisited: a decade of advancements, 2004-2014. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(9):1058-1063.

10. Brown JWL, Coles A, Horakova D, et al. Association of initial disease-modifying therapy with later conversion to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. JAMA. 2019;321(2):175-187.

11. Hua LH, Harris H, Conway D, Thompson NR. Changes in patient-reported outcomes between continuers and discontinuers of disease modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis over age 60 [published correction appears in Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;30:293]. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;30:252-256.

12. Bsteh G, Feige J, Ehling R, et al. Discontinuation of disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis - Clinical outcome and prognostic factors. Mult Scler. 2017;23(9):1241-1248.

13. Weideman AM, Tapia-Maltos MA, Johnson K, Greenwood M, Bielekova B. Meta-analysis of the age-dependent efficacy of multiple sclerosis treatments. Front Neurol. 2017;8:577.

14. Kister I, Spelman T, Alroughani R, et al; MSBase Study Group. Discontinuing disease-modifying therapy in MS after a prolonged relapse-free period: a propensity score-matched study [published correction appears in J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019;90(4):e2]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(10):1133-1137.

15. Birnbaum G. Stopping disease-modifying therapy in nonrelapsing multiple sclerosis: experience from a clinical practice. Int J MS Care. 2017;19(1):11-14.

16. Hawker K, O’Connor P, Freedman MS, et al. Rituximab in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis: results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Ann Neurol. 2009;66(4):460-471.

17. Hauser SL, Waubant E, Arnold DL, et al. B-cell depletion with rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(7):676–688.

18. Alping P, Frisell T, Novakova L, et al. Rituximab versus fingolimod after natalizumab in multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(6):950–958.

19. Rituximab-abbs [package insert]. North Wales, PA: Teva Pharmaceuticals; 2018.

20. Zhovtis Ryerson L, Frohman TC, Foley J, et al. Extended interval dosing of natalizumab in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(8):885-889.

21. Dimethyl fumarate [package insert]. Cambridge, MA: Biogen Inc; 2015.

22. van Kester MS, Bouwes Bavinck JN, Quint KD. PML in Patients treated with dimethyl fumarate. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(6):583-584.

23. Nieuwkamp DJ, Murk JL, van Oosten BW. PML in patients treated with dimethyl fumarate. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(6):584.

24. Rosenkranz T, Novas M, Terborg C. PML in a patient with lymphocytopenia treated with dimethyl fumarate. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(15):1476-1478.

25. Longbrake EE, Cross AH. Dimethyl fumarate associated lymphopenia in clinical practice. Mult Scler. 2015;21(6):796-797.

26. Gold R, Arnold DL, Bar-Or A, et al. Long-term effects of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate in multiple sclerosis: Interim analysis of ENDORSE, a randomized extension study. Mult Scler. 2017;23(2):253–265.

27. Hanson RL, Habibi M, Khamo N, Abdou S, Stubbings J. Integrated clinical and specialty pharmacy practice model for management of patients with multiple sclerosis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(6):463-469.

28. Federal Planning Bureau. Consumer Price Index - Inflation forecasts. https://www.plan.be/databases/17-en-consumer+price+index+inflation+forecasts. Updated March 3, 2020. Accessed March 9, 2020.