User login

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has established a number of centers of excellence (CoEs), including centers focused on posttraumatic stress disorder, suicide prevention, epilepsy, and, most recently, the Senator Elizabeth Dole CoE for Veteran and Caregiver Research. Some VA CoE serve as centralized locations for specialty care. For example, the VA Epilepsy CoE is a network of 16 facilities that provide comprehensive epilepsy care for veterans with seizure disorders, including expert and presurgical evaluations and inpatient monitoring.

In contrast, other CoEs, including the multiple sclerosis (MS) CoE, achieve their missions by serving as a resource center to a network of regional and supporting various programs to optimize the care of veterans across the nation within their home US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center (VAMC). The MSCoE are charged, through VHA Directive 1011.06, with establishing at least 1 VA MS Regional Program in each of the 21 Veteran Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) across the country and integrating these and affiliated MS Support Programs into the MS National Network. Currently, there are 29 MS regional programs and 49 MS support programs across the US.1

Established in 2003, the MSCoE is dedicated to furthering the understanding of MS, its impact on veterans, and effective treatments to help manage the disease and its symptoms. In 2002, 2 coordinating centers were selected based on a competitive review process. The MSCoE-East is located at the Baltimore, Maryland and Washington, DC VAMC and serves VISNs 1 to 10. The MSCoE-West serves VISNs 11 to 23 and is jointly-based at VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle, Washington and VA Portland Health Care System in Portland, Oregon. The MSCoEs were made permanent by The Veteran’ Benefits, Healthcare and Information Technology Act of 2006 (38 USC §7330). By partnering with veterans, caregivers, health care professionals, and other affiliates, the MSCoE endeavor to optimize health, activities, participation and quality of life for veterans with MS.

Core Functions

The MSCoE has a 3-part mission. First, the MSCoE seeks to expand care coordination between VAMCs by developing a national network of VA MSCoE Regional and Support Programs. Second, the MSCoE provides resources to VA health care providers (HCPs) through a collaborative approach to clinical care, education, research, and informatics. Third, the MSCoE improves the quality and consistency of health care services delivered to veterans diagnosed with MS nationwide. To meet its objectives, the MSCoE activities are organized around 4 functional cores: clinical care, research, education and training, and informatics and telemedicine.

Clinical Care

The MSCoE delivers high-quality clinical care by identifying veterans with MS who use VA services, understanding their needs, and facilitating appropriate interventions. Veterans with MS are a special cohort for many reasons including that about 70% are male. Men and women veterans not only have different genetics, but also may have different environmental exposures and other risk factors for MS. Since 1998, the VHA has evaluated > 50,000 veterans with MS. Over the past decade, between 18,000 and 20,000 veterans with MS have accessed care within the VHA annually.

The MSCoE advocates for appropriate and safe use of currently available MS disease modifying therapies through collaborations with the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Service (PBM). The MSCoE partners with PBM to develop and disseminate Criteria For Use, safety, and economic monitoring of the impacts of the MS therapies. The MSCoE also provide national consultation services for complex MS cases, clinical education to VA HCPs, and mentors fellows, residents, and medical students.

The VA provides numerous resources that are not readily available in other health care systems and facilitate the care for patients with chronic diseases, including providing low or no co-pays to patients for MS disease modifying agents and other MS related medications, access to medically necessary adaptive equipment at no charge, the Home Improvement and Structural Alteration (HISA) grant for assistance with safe home ingress and egress, respite care, access to a homemaker/home health aide, and caregiver support programs. Eligible veterans also can access additional resources such as adaptive housing and an automobile grant. The VA also provides substantial hands-on assistance to veterans who are homeless. The clinical team and a veteran with MS can leverage VA resources through the National MS Society (NMSS) Navigator Program as well as other community resources.2

The VHA encourages physical activity and wellness through sports and leisure. Veterans with MS can participate in sports programs and special events, including the National Veterans Wheelchair Games, the National Disabled Veterans Winter Sports Clinic, the National Disabled Veterans TEE (Training, Exposure and Experience) golf tournament, the National Veterans Summer Sports Clinic, the National Veterans Golden Age Games, and the National Veterans Creative Sports Festival. HCPs or veterans who are not sure how to access any of these programs can contact the MSCoE or their local VA social workers.

Research

The primary goal of the MSCoE research core is to conduct clinical, health services, epidemiologic, and basic science research relevant to veterans with MS. The MSCoE serves to enhance collaboration among VAMCs, increase the participation of veterans in research, and provide research mentorship for the next generation of VA MS scientists. MSCoE research is carried out by investigators at the MSCoE and the MS Regional Programs, often in collaboration with investigators at academic institutions. This research is supported by competitive grant awards from a variety of funding agencies including the VA Research and Development Service (R&D) and the NMSS. Results from about 40 research grants in Fiscal Year 2019 were disseminated through 34 peer-reviewed publications, 30 posters, presentations, abstracts, and clinical practice guidelines.

There are many examples of recent high impact MS research performed by MSCoE investigators. For example, MSCoE researchers noted an increase in the estimated prevalence of MS to 1 million individuals in the US, about twice the previously estimated prevalence.3-5 In addition, a multicenter study highlighted the prevalence of MS misdiagnosis and common confounders for MS.6 Other research includes pilot clinical trials evaluating lipoic acid as a potential disease modifying therapy in people with secondary progressive MS and the impact of a multicomponent walking aid selection, fitting, and training program for preventing falls in people with MS.7,8 Clinical trial also are investigating telehealth counseling to improve physical activity in MS and a systematic review of rehabilitation interventions in MS.9,10

Education and Training

A unified program of education is essential to effective management of MS nationally. The primary goal of the education and training core is to provide a national program of MS education for HCPs, veterans, and caregivers to improve knowledge, enhance access to resources, and promote effective management strategies. The MSCoE collaborate with the Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA), the Consortium of MS Centers (CMSC), the NMSS, and other national service organizations to increase educational opportunities, share knowledge, and expand participation.

The MSCoE education and training core produces a range of products both veterans, HCPs, and others affected by MS. The MSCoE sends a biannual patient newsletter to > 20,000 veterans and a monthly email to > 1,000 VA HCPs. Specific opportunities for HCP education include accredited multidisciplinary MS webinars, sponsored symposia and workshops at the CMSC and PVA Summit annual meetings, and presentations at other university and professional conferences. Enduring educational opportunities for veterans, caregivers, and HCPs can also be found by visiting www.va.gov/ms.

The MSCoE coordinate postdoctoral fellowship training programs to develop expertise in MS health care for the future. It offers VA physician fellowships for neurologists in Baltimore and Portland and for physiatrists in Seattle as well as NMSS fellowships for education and research. In 2019, MSCoE had 6 MD Fellows and 1 PhD Fellow.

Clinical Informatics and Telehealth

The primary goal of the informatics and telemedicine core is to employ state-of-the-art informatics, telemedicine technology, and the MSCoE website, to improve MS health care delivery. The VA has a integrated electronic health record and various data repositories are stored in the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). MSCoE utilizes the CDW to maintain a national MS administrative data repository to understand the VHA care provided to veterans with MS. Data from the CDW have also served as an important resource to facilitate a wide range of veteran-focused MS research. This research has addressed clinical conditions like pain and obesity; health behaviors like smoking, alcohol use, and exercise as well as issues related to care delivery such as specialty care access, medication adherence, and appointment attendance.11-19

Monitoring the health of veterans with MS in the VA requires additional data not available in the CDW. To this end, we have developed the MS Surveillance Registry (MSSR), funded and maintained by the VA Office of Information Technology as part of their Veteran Integrated Registry Platform (VIRP). The purpose of the MSSR is to understand the unique characteristics and treatment patterns of veterans with MS in order to optimize their VHA care. HCPs input MS-specific clinical data on their patients into the MSSR, either through the MS Assessment Tool (MSAT) in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) or through a secure online portal. Other data from existing databases from the CDW is also automatically fed into the MSSR. The MSSR continues to be developed and populated to serve as a resource for the future.

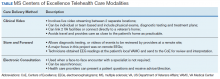

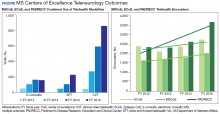

Neurologists, physiatrists, psychologists, and rehabilitation specialists can use telehealth to evaluate and treat veterans who have difficulty accessing outpatient clinics, either because of mobility limitations, or distance. Between 2012 and 2015, the VA MSCoE, together with the Epilepsy CoE and the Parkinson’s Disease Research and Clinical Centers in VISNs 5, 6 (mid-Atlantic) and 20 (Pacific Northwest) initiated an integrated teleneurology project. The goal of this project was to improve patient access to care at 4 tertiary and 12 regional VAMCs. A study team, with administrators and key clinical stakeholders, followed a traditional project management approach to design, plan, implement and evaluate an optimal model for communication and referrals with both live visits and telehealth (Table). Major outcomes of the project included: delivering subspecialty teleneurology to 47 patient sites, increasing interfacility consultation by 133% while reducing wait times by roughly 40%, and increasing telemedicine workload at these centers from 95 annual encounters in 2012 to 1,245 annual encounters in 2015 (Figure).

Today, telehealth for veterans with MS can be delivered to nearby VA facilities closer to their home, within their home, or anywhere else the veteran can use a cellphone or tablet. Telehealth visits can save travel time and expenses and optimize VA productivity and clinic use. The MSCoE and many of the MS regional programs are using telehealth for MS physician follow-up and therapies. The VA Office of Rural Health is also currently working with the MS network to use telehealth to increase access to physical therapy to those who have difficulty coming into clinic.

MSCoE Resources

The MSCoE is funded by VA Central Office through the Office of Specialty Care by Special Purpose funds. The directive specifies that funding for the regional and support programs is through Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation based on VISN and facility workload and complexity. Any research is funded separately through grants, some from VA R&D and others from other sources including the National Institutes of Health, the Patient Centered Outcome Research Institute, affiliated universities, the NMSS, the MS Society of Canada, the Consortium of MS Centers, foundations, and industry.

In 2019, MSCoE investigators received grants totaling > $18 million in funding. In-kind support also is provided by the PVA, the CMSC, the NMSS, and others. The first 3 foundations have been supporters since the inception of the MSCoE and have provided opportunities for the dissemination of education and research for HCPs, fellows, residents and medical students; travel; meeting rooms for MSCoE national meetings; exhibit space for HCP outreach; competitive research and educational grant support; programming and resources for veterans and significant others; organizational expertise; and opportunities for VA HCPs, veterans, and caregivers to learn how to navigate MS with others in the private sector.

Conclusion

The MSCoE had a tremendous impact on improving the consistency and quality of care for veterans with MS through clinical care, research, education and informatics and telehealth. Since opening in 2003, there has been an increase in the number of MS specialty clinics, served veterans with MS, and veterans receiving specialty neurologic and rehabilitation services in VA. Research programs in MS have been initiated to address key questions relevant to veterans with MS, including immunology, epidemiology, clinical care, and rehabilitation. Educational programs and products have evolved with technology and had a greater impact through partnerships with veteran and MS nonprofit organizations.

MSCoE strives to minimize impairment and maximize quality of life for veterans with MS by leveraging integrated electronic health records, data repositories, and telehealth services. These efforts have all improved veteran health, access and safety. We look forward to continuing into the next decade by bringing fresh ideas to the care of veterans with MS, their families and caregivers.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Multiple Sclerosis Centers of Excellence. Multiple Sclerosis System of Care-VHA Directive 1101.06 and Multiple Sclerosis Centers of Excellence network facilities. https://www.va.gov/MS/veterans/find_a_clinic/index_clinics.asp. Updated February 26, 2020. Accessed March 6, 2020.

2. National MS Society. MS navigator program. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/For-Professionals/Clinical-Care/MS-Navigator-Program. Accessed March 6, 2020.

3. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, et al. The prevalence of MS in the United States: a population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology. 2019;92:e1029-e1040.

4. GBD 2016 Multiple Sclerosis Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of multiple sclerosis 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(3):269-285.

5. GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(5):459-480.

6. Solomon AJ, Bourdette DN, Cross AH, et al. The contemporary spectrum of multiple sclerosis misdiagnosis: a multicenter study. Neurology. 2016;87(13):1393-1399.

7. Spain R, Powers K, Murchison C, et al. Lipoic acid in secondary progressive MS: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2017;4(5):e374.

8. Martini DN, Zeeboer E, Hildebrand A, Fling BW, Hugos CL, Cameron MH. ADSTEP: preliminary investigation of a multicomponent walking aid program in people with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(10):2050-2058.

9. Turner AP, Hartoonian N, Sloan AP, et al. Improving fatigue and depression in individuals with multiple sclerosis using telephone-administered physical activity counseling. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84(4):297-309.

10. Haselkorn JK, Hughes C, Rae-Grant A, et al. Summary of comprehensive systematic review: rehabilitation in multiple sclerosis: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2015;85(21):1896-1903.

11. Hirsh AT, Turner AP, Ehde DM, Haselkorn JK. Prevalence and impact of pain in multiple sclerosis: physical and psychologic contributors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(4):646-651.

12. Khurana SR, Bamer AM, Turner AP, et al. The prevalence of overweight and obesity in veterans with multiple sclerosis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;88(2):83-91.

13. Turner AP, Kivlahan DR, Kazis LE, Haselkorn JK. Smoking among veterans with multiple sclerosis: prevalence correlates, quit attempts, and unmet need for services. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(11):1394-1399.

14. Turner AP, Hawkins EJ, Haselkorn JK, Kivlahan DR. Alcohol misuse and multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(5):842-848.

15. Turner AP, Kivlahan DR, Haselkorn JK. Exercise and quality of life among people with multiple sclerosis: looking beyond physical functioning to mental health and participation in life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(3):420-428.

16. Turner AP, Chapko MK, Yanez D, et al. Access to multiple sclerosis specialty care. PM R. 2013;5(12):1044-1050.

17. Gromisch ES, Turner AP, Leipertz SL, Beauvais J, Haselkorn JK. Risk factors for suboptimal medication adherence in persons with multiple sclerosis: development of an electronic health record-based explanatory model for disease-modifying therapy use [published online ahead of print, 2019 Dec 3]. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;S0003-9993(19)31430-3143.

18. Settle JR, Maloni H, Bedra M, Finkelstein J, Zhan M, Wallin M. Monitoring medication adherence in multiple sclerosis using a novel web-based tool. J Telemed Telecare. 2016;22:225-233.

19. Gromisch ES, Turner AP, Leipertz SL, Beauvais J, Haselkorn JK. Who is not coming to clinic? A predictive model of excessive missed appointments in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Rel Dis. In Press.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has established a number of centers of excellence (CoEs), including centers focused on posttraumatic stress disorder, suicide prevention, epilepsy, and, most recently, the Senator Elizabeth Dole CoE for Veteran and Caregiver Research. Some VA CoE serve as centralized locations for specialty care. For example, the VA Epilepsy CoE is a network of 16 facilities that provide comprehensive epilepsy care for veterans with seizure disorders, including expert and presurgical evaluations and inpatient monitoring.

In contrast, other CoEs, including the multiple sclerosis (MS) CoE, achieve their missions by serving as a resource center to a network of regional and supporting various programs to optimize the care of veterans across the nation within their home US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center (VAMC). The MSCoE are charged, through VHA Directive 1011.06, with establishing at least 1 VA MS Regional Program in each of the 21 Veteran Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) across the country and integrating these and affiliated MS Support Programs into the MS National Network. Currently, there are 29 MS regional programs and 49 MS support programs across the US.1

Established in 2003, the MSCoE is dedicated to furthering the understanding of MS, its impact on veterans, and effective treatments to help manage the disease and its symptoms. In 2002, 2 coordinating centers were selected based on a competitive review process. The MSCoE-East is located at the Baltimore, Maryland and Washington, DC VAMC and serves VISNs 1 to 10. The MSCoE-West serves VISNs 11 to 23 and is jointly-based at VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle, Washington and VA Portland Health Care System in Portland, Oregon. The MSCoEs were made permanent by The Veteran’ Benefits, Healthcare and Information Technology Act of 2006 (38 USC §7330). By partnering with veterans, caregivers, health care professionals, and other affiliates, the MSCoE endeavor to optimize health, activities, participation and quality of life for veterans with MS.

Core Functions

The MSCoE has a 3-part mission. First, the MSCoE seeks to expand care coordination between VAMCs by developing a national network of VA MSCoE Regional and Support Programs. Second, the MSCoE provides resources to VA health care providers (HCPs) through a collaborative approach to clinical care, education, research, and informatics. Third, the MSCoE improves the quality and consistency of health care services delivered to veterans diagnosed with MS nationwide. To meet its objectives, the MSCoE activities are organized around 4 functional cores: clinical care, research, education and training, and informatics and telemedicine.

Clinical Care

The MSCoE delivers high-quality clinical care by identifying veterans with MS who use VA services, understanding their needs, and facilitating appropriate interventions. Veterans with MS are a special cohort for many reasons including that about 70% are male. Men and women veterans not only have different genetics, but also may have different environmental exposures and other risk factors for MS. Since 1998, the VHA has evaluated > 50,000 veterans with MS. Over the past decade, between 18,000 and 20,000 veterans with MS have accessed care within the VHA annually.

The MSCoE advocates for appropriate and safe use of currently available MS disease modifying therapies through collaborations with the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Service (PBM). The MSCoE partners with PBM to develop and disseminate Criteria For Use, safety, and economic monitoring of the impacts of the MS therapies. The MSCoE also provide national consultation services for complex MS cases, clinical education to VA HCPs, and mentors fellows, residents, and medical students.

The VA provides numerous resources that are not readily available in other health care systems and facilitate the care for patients with chronic diseases, including providing low or no co-pays to patients for MS disease modifying agents and other MS related medications, access to medically necessary adaptive equipment at no charge, the Home Improvement and Structural Alteration (HISA) grant for assistance with safe home ingress and egress, respite care, access to a homemaker/home health aide, and caregiver support programs. Eligible veterans also can access additional resources such as adaptive housing and an automobile grant. The VA also provides substantial hands-on assistance to veterans who are homeless. The clinical team and a veteran with MS can leverage VA resources through the National MS Society (NMSS) Navigator Program as well as other community resources.2

The VHA encourages physical activity and wellness through sports and leisure. Veterans with MS can participate in sports programs and special events, including the National Veterans Wheelchair Games, the National Disabled Veterans Winter Sports Clinic, the National Disabled Veterans TEE (Training, Exposure and Experience) golf tournament, the National Veterans Summer Sports Clinic, the National Veterans Golden Age Games, and the National Veterans Creative Sports Festival. HCPs or veterans who are not sure how to access any of these programs can contact the MSCoE or their local VA social workers.

Research

The primary goal of the MSCoE research core is to conduct clinical, health services, epidemiologic, and basic science research relevant to veterans with MS. The MSCoE serves to enhance collaboration among VAMCs, increase the participation of veterans in research, and provide research mentorship for the next generation of VA MS scientists. MSCoE research is carried out by investigators at the MSCoE and the MS Regional Programs, often in collaboration with investigators at academic institutions. This research is supported by competitive grant awards from a variety of funding agencies including the VA Research and Development Service (R&D) and the NMSS. Results from about 40 research grants in Fiscal Year 2019 were disseminated through 34 peer-reviewed publications, 30 posters, presentations, abstracts, and clinical practice guidelines.

There are many examples of recent high impact MS research performed by MSCoE investigators. For example, MSCoE researchers noted an increase in the estimated prevalence of MS to 1 million individuals in the US, about twice the previously estimated prevalence.3-5 In addition, a multicenter study highlighted the prevalence of MS misdiagnosis and common confounders for MS.6 Other research includes pilot clinical trials evaluating lipoic acid as a potential disease modifying therapy in people with secondary progressive MS and the impact of a multicomponent walking aid selection, fitting, and training program for preventing falls in people with MS.7,8 Clinical trial also are investigating telehealth counseling to improve physical activity in MS and a systematic review of rehabilitation interventions in MS.9,10

Education and Training

A unified program of education is essential to effective management of MS nationally. The primary goal of the education and training core is to provide a national program of MS education for HCPs, veterans, and caregivers to improve knowledge, enhance access to resources, and promote effective management strategies. The MSCoE collaborate with the Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA), the Consortium of MS Centers (CMSC), the NMSS, and other national service organizations to increase educational opportunities, share knowledge, and expand participation.

The MSCoE education and training core produces a range of products both veterans, HCPs, and others affected by MS. The MSCoE sends a biannual patient newsletter to > 20,000 veterans and a monthly email to > 1,000 VA HCPs. Specific opportunities for HCP education include accredited multidisciplinary MS webinars, sponsored symposia and workshops at the CMSC and PVA Summit annual meetings, and presentations at other university and professional conferences. Enduring educational opportunities for veterans, caregivers, and HCPs can also be found by visiting www.va.gov/ms.

The MSCoE coordinate postdoctoral fellowship training programs to develop expertise in MS health care for the future. It offers VA physician fellowships for neurologists in Baltimore and Portland and for physiatrists in Seattle as well as NMSS fellowships for education and research. In 2019, MSCoE had 6 MD Fellows and 1 PhD Fellow.

Clinical Informatics and Telehealth

The primary goal of the informatics and telemedicine core is to employ state-of-the-art informatics, telemedicine technology, and the MSCoE website, to improve MS health care delivery. The VA has a integrated electronic health record and various data repositories are stored in the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). MSCoE utilizes the CDW to maintain a national MS administrative data repository to understand the VHA care provided to veterans with MS. Data from the CDW have also served as an important resource to facilitate a wide range of veteran-focused MS research. This research has addressed clinical conditions like pain and obesity; health behaviors like smoking, alcohol use, and exercise as well as issues related to care delivery such as specialty care access, medication adherence, and appointment attendance.11-19

Monitoring the health of veterans with MS in the VA requires additional data not available in the CDW. To this end, we have developed the MS Surveillance Registry (MSSR), funded and maintained by the VA Office of Information Technology as part of their Veteran Integrated Registry Platform (VIRP). The purpose of the MSSR is to understand the unique characteristics and treatment patterns of veterans with MS in order to optimize their VHA care. HCPs input MS-specific clinical data on their patients into the MSSR, either through the MS Assessment Tool (MSAT) in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) or through a secure online portal. Other data from existing databases from the CDW is also automatically fed into the MSSR. The MSSR continues to be developed and populated to serve as a resource for the future.

Neurologists, physiatrists, psychologists, and rehabilitation specialists can use telehealth to evaluate and treat veterans who have difficulty accessing outpatient clinics, either because of mobility limitations, or distance. Between 2012 and 2015, the VA MSCoE, together with the Epilepsy CoE and the Parkinson’s Disease Research and Clinical Centers in VISNs 5, 6 (mid-Atlantic) and 20 (Pacific Northwest) initiated an integrated teleneurology project. The goal of this project was to improve patient access to care at 4 tertiary and 12 regional VAMCs. A study team, with administrators and key clinical stakeholders, followed a traditional project management approach to design, plan, implement and evaluate an optimal model for communication and referrals with both live visits and telehealth (Table). Major outcomes of the project included: delivering subspecialty teleneurology to 47 patient sites, increasing interfacility consultation by 133% while reducing wait times by roughly 40%, and increasing telemedicine workload at these centers from 95 annual encounters in 2012 to 1,245 annual encounters in 2015 (Figure).

Today, telehealth for veterans with MS can be delivered to nearby VA facilities closer to their home, within their home, or anywhere else the veteran can use a cellphone or tablet. Telehealth visits can save travel time and expenses and optimize VA productivity and clinic use. The MSCoE and many of the MS regional programs are using telehealth for MS physician follow-up and therapies. The VA Office of Rural Health is also currently working with the MS network to use telehealth to increase access to physical therapy to those who have difficulty coming into clinic.

MSCoE Resources

The MSCoE is funded by VA Central Office through the Office of Specialty Care by Special Purpose funds. The directive specifies that funding for the regional and support programs is through Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation based on VISN and facility workload and complexity. Any research is funded separately through grants, some from VA R&D and others from other sources including the National Institutes of Health, the Patient Centered Outcome Research Institute, affiliated universities, the NMSS, the MS Society of Canada, the Consortium of MS Centers, foundations, and industry.

In 2019, MSCoE investigators received grants totaling > $18 million in funding. In-kind support also is provided by the PVA, the CMSC, the NMSS, and others. The first 3 foundations have been supporters since the inception of the MSCoE and have provided opportunities for the dissemination of education and research for HCPs, fellows, residents and medical students; travel; meeting rooms for MSCoE national meetings; exhibit space for HCP outreach; competitive research and educational grant support; programming and resources for veterans and significant others; organizational expertise; and opportunities for VA HCPs, veterans, and caregivers to learn how to navigate MS with others in the private sector.

Conclusion

The MSCoE had a tremendous impact on improving the consistency and quality of care for veterans with MS through clinical care, research, education and informatics and telehealth. Since opening in 2003, there has been an increase in the number of MS specialty clinics, served veterans with MS, and veterans receiving specialty neurologic and rehabilitation services in VA. Research programs in MS have been initiated to address key questions relevant to veterans with MS, including immunology, epidemiology, clinical care, and rehabilitation. Educational programs and products have evolved with technology and had a greater impact through partnerships with veteran and MS nonprofit organizations.

MSCoE strives to minimize impairment and maximize quality of life for veterans with MS by leveraging integrated electronic health records, data repositories, and telehealth services. These efforts have all improved veteran health, access and safety. We look forward to continuing into the next decade by bringing fresh ideas to the care of veterans with MS, their families and caregivers.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has established a number of centers of excellence (CoEs), including centers focused on posttraumatic stress disorder, suicide prevention, epilepsy, and, most recently, the Senator Elizabeth Dole CoE for Veteran and Caregiver Research. Some VA CoE serve as centralized locations for specialty care. For example, the VA Epilepsy CoE is a network of 16 facilities that provide comprehensive epilepsy care for veterans with seizure disorders, including expert and presurgical evaluations and inpatient monitoring.

In contrast, other CoEs, including the multiple sclerosis (MS) CoE, achieve their missions by serving as a resource center to a network of regional and supporting various programs to optimize the care of veterans across the nation within their home US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center (VAMC). The MSCoE are charged, through VHA Directive 1011.06, with establishing at least 1 VA MS Regional Program in each of the 21 Veteran Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) across the country and integrating these and affiliated MS Support Programs into the MS National Network. Currently, there are 29 MS regional programs and 49 MS support programs across the US.1

Established in 2003, the MSCoE is dedicated to furthering the understanding of MS, its impact on veterans, and effective treatments to help manage the disease and its symptoms. In 2002, 2 coordinating centers were selected based on a competitive review process. The MSCoE-East is located at the Baltimore, Maryland and Washington, DC VAMC and serves VISNs 1 to 10. The MSCoE-West serves VISNs 11 to 23 and is jointly-based at VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle, Washington and VA Portland Health Care System in Portland, Oregon. The MSCoEs were made permanent by The Veteran’ Benefits, Healthcare and Information Technology Act of 2006 (38 USC §7330). By partnering with veterans, caregivers, health care professionals, and other affiliates, the MSCoE endeavor to optimize health, activities, participation and quality of life for veterans with MS.

Core Functions

The MSCoE has a 3-part mission. First, the MSCoE seeks to expand care coordination between VAMCs by developing a national network of VA MSCoE Regional and Support Programs. Second, the MSCoE provides resources to VA health care providers (HCPs) through a collaborative approach to clinical care, education, research, and informatics. Third, the MSCoE improves the quality and consistency of health care services delivered to veterans diagnosed with MS nationwide. To meet its objectives, the MSCoE activities are organized around 4 functional cores: clinical care, research, education and training, and informatics and telemedicine.

Clinical Care

The MSCoE delivers high-quality clinical care by identifying veterans with MS who use VA services, understanding their needs, and facilitating appropriate interventions. Veterans with MS are a special cohort for many reasons including that about 70% are male. Men and women veterans not only have different genetics, but also may have different environmental exposures and other risk factors for MS. Since 1998, the VHA has evaluated > 50,000 veterans with MS. Over the past decade, between 18,000 and 20,000 veterans with MS have accessed care within the VHA annually.

The MSCoE advocates for appropriate and safe use of currently available MS disease modifying therapies through collaborations with the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Service (PBM). The MSCoE partners with PBM to develop and disseminate Criteria For Use, safety, and economic monitoring of the impacts of the MS therapies. The MSCoE also provide national consultation services for complex MS cases, clinical education to VA HCPs, and mentors fellows, residents, and medical students.

The VA provides numerous resources that are not readily available in other health care systems and facilitate the care for patients with chronic diseases, including providing low or no co-pays to patients for MS disease modifying agents and other MS related medications, access to medically necessary adaptive equipment at no charge, the Home Improvement and Structural Alteration (HISA) grant for assistance with safe home ingress and egress, respite care, access to a homemaker/home health aide, and caregiver support programs. Eligible veterans also can access additional resources such as adaptive housing and an automobile grant. The VA also provides substantial hands-on assistance to veterans who are homeless. The clinical team and a veteran with MS can leverage VA resources through the National MS Society (NMSS) Navigator Program as well as other community resources.2

The VHA encourages physical activity and wellness through sports and leisure. Veterans with MS can participate in sports programs and special events, including the National Veterans Wheelchair Games, the National Disabled Veterans Winter Sports Clinic, the National Disabled Veterans TEE (Training, Exposure and Experience) golf tournament, the National Veterans Summer Sports Clinic, the National Veterans Golden Age Games, and the National Veterans Creative Sports Festival. HCPs or veterans who are not sure how to access any of these programs can contact the MSCoE or their local VA social workers.

Research

The primary goal of the MSCoE research core is to conduct clinical, health services, epidemiologic, and basic science research relevant to veterans with MS. The MSCoE serves to enhance collaboration among VAMCs, increase the participation of veterans in research, and provide research mentorship for the next generation of VA MS scientists. MSCoE research is carried out by investigators at the MSCoE and the MS Regional Programs, often in collaboration with investigators at academic institutions. This research is supported by competitive grant awards from a variety of funding agencies including the VA Research and Development Service (R&D) and the NMSS. Results from about 40 research grants in Fiscal Year 2019 were disseminated through 34 peer-reviewed publications, 30 posters, presentations, abstracts, and clinical practice guidelines.

There are many examples of recent high impact MS research performed by MSCoE investigators. For example, MSCoE researchers noted an increase in the estimated prevalence of MS to 1 million individuals in the US, about twice the previously estimated prevalence.3-5 In addition, a multicenter study highlighted the prevalence of MS misdiagnosis and common confounders for MS.6 Other research includes pilot clinical trials evaluating lipoic acid as a potential disease modifying therapy in people with secondary progressive MS and the impact of a multicomponent walking aid selection, fitting, and training program for preventing falls in people with MS.7,8 Clinical trial also are investigating telehealth counseling to improve physical activity in MS and a systematic review of rehabilitation interventions in MS.9,10

Education and Training

A unified program of education is essential to effective management of MS nationally. The primary goal of the education and training core is to provide a national program of MS education for HCPs, veterans, and caregivers to improve knowledge, enhance access to resources, and promote effective management strategies. The MSCoE collaborate with the Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA), the Consortium of MS Centers (CMSC), the NMSS, and other national service organizations to increase educational opportunities, share knowledge, and expand participation.

The MSCoE education and training core produces a range of products both veterans, HCPs, and others affected by MS. The MSCoE sends a biannual patient newsletter to > 20,000 veterans and a monthly email to > 1,000 VA HCPs. Specific opportunities for HCP education include accredited multidisciplinary MS webinars, sponsored symposia and workshops at the CMSC and PVA Summit annual meetings, and presentations at other university and professional conferences. Enduring educational opportunities for veterans, caregivers, and HCPs can also be found by visiting www.va.gov/ms.

The MSCoE coordinate postdoctoral fellowship training programs to develop expertise in MS health care for the future. It offers VA physician fellowships for neurologists in Baltimore and Portland and for physiatrists in Seattle as well as NMSS fellowships for education and research. In 2019, MSCoE had 6 MD Fellows and 1 PhD Fellow.

Clinical Informatics and Telehealth

The primary goal of the informatics and telemedicine core is to employ state-of-the-art informatics, telemedicine technology, and the MSCoE website, to improve MS health care delivery. The VA has a integrated electronic health record and various data repositories are stored in the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). MSCoE utilizes the CDW to maintain a national MS administrative data repository to understand the VHA care provided to veterans with MS. Data from the CDW have also served as an important resource to facilitate a wide range of veteran-focused MS research. This research has addressed clinical conditions like pain and obesity; health behaviors like smoking, alcohol use, and exercise as well as issues related to care delivery such as specialty care access, medication adherence, and appointment attendance.11-19

Monitoring the health of veterans with MS in the VA requires additional data not available in the CDW. To this end, we have developed the MS Surveillance Registry (MSSR), funded and maintained by the VA Office of Information Technology as part of their Veteran Integrated Registry Platform (VIRP). The purpose of the MSSR is to understand the unique characteristics and treatment patterns of veterans with MS in order to optimize their VHA care. HCPs input MS-specific clinical data on their patients into the MSSR, either through the MS Assessment Tool (MSAT) in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) or through a secure online portal. Other data from existing databases from the CDW is also automatically fed into the MSSR. The MSSR continues to be developed and populated to serve as a resource for the future.

Neurologists, physiatrists, psychologists, and rehabilitation specialists can use telehealth to evaluate and treat veterans who have difficulty accessing outpatient clinics, either because of mobility limitations, or distance. Between 2012 and 2015, the VA MSCoE, together with the Epilepsy CoE and the Parkinson’s Disease Research and Clinical Centers in VISNs 5, 6 (mid-Atlantic) and 20 (Pacific Northwest) initiated an integrated teleneurology project. The goal of this project was to improve patient access to care at 4 tertiary and 12 regional VAMCs. A study team, with administrators and key clinical stakeholders, followed a traditional project management approach to design, plan, implement and evaluate an optimal model for communication and referrals with both live visits and telehealth (Table). Major outcomes of the project included: delivering subspecialty teleneurology to 47 patient sites, increasing interfacility consultation by 133% while reducing wait times by roughly 40%, and increasing telemedicine workload at these centers from 95 annual encounters in 2012 to 1,245 annual encounters in 2015 (Figure).

Today, telehealth for veterans with MS can be delivered to nearby VA facilities closer to their home, within their home, or anywhere else the veteran can use a cellphone or tablet. Telehealth visits can save travel time and expenses and optimize VA productivity and clinic use. The MSCoE and many of the MS regional programs are using telehealth for MS physician follow-up and therapies. The VA Office of Rural Health is also currently working with the MS network to use telehealth to increase access to physical therapy to those who have difficulty coming into clinic.

MSCoE Resources

The MSCoE is funded by VA Central Office through the Office of Specialty Care by Special Purpose funds. The directive specifies that funding for the regional and support programs is through Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation based on VISN and facility workload and complexity. Any research is funded separately through grants, some from VA R&D and others from other sources including the National Institutes of Health, the Patient Centered Outcome Research Institute, affiliated universities, the NMSS, the MS Society of Canada, the Consortium of MS Centers, foundations, and industry.

In 2019, MSCoE investigators received grants totaling > $18 million in funding. In-kind support also is provided by the PVA, the CMSC, the NMSS, and others. The first 3 foundations have been supporters since the inception of the MSCoE and have provided opportunities for the dissemination of education and research for HCPs, fellows, residents and medical students; travel; meeting rooms for MSCoE national meetings; exhibit space for HCP outreach; competitive research and educational grant support; programming and resources for veterans and significant others; organizational expertise; and opportunities for VA HCPs, veterans, and caregivers to learn how to navigate MS with others in the private sector.

Conclusion

The MSCoE had a tremendous impact on improving the consistency and quality of care for veterans with MS through clinical care, research, education and informatics and telehealth. Since opening in 2003, there has been an increase in the number of MS specialty clinics, served veterans with MS, and veterans receiving specialty neurologic and rehabilitation services in VA. Research programs in MS have been initiated to address key questions relevant to veterans with MS, including immunology, epidemiology, clinical care, and rehabilitation. Educational programs and products have evolved with technology and had a greater impact through partnerships with veteran and MS nonprofit organizations.

MSCoE strives to minimize impairment and maximize quality of life for veterans with MS by leveraging integrated electronic health records, data repositories, and telehealth services. These efforts have all improved veteran health, access and safety. We look forward to continuing into the next decade by bringing fresh ideas to the care of veterans with MS, their families and caregivers.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Multiple Sclerosis Centers of Excellence. Multiple Sclerosis System of Care-VHA Directive 1101.06 and Multiple Sclerosis Centers of Excellence network facilities. https://www.va.gov/MS/veterans/find_a_clinic/index_clinics.asp. Updated February 26, 2020. Accessed March 6, 2020.

2. National MS Society. MS navigator program. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/For-Professionals/Clinical-Care/MS-Navigator-Program. Accessed March 6, 2020.

3. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, et al. The prevalence of MS in the United States: a population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology. 2019;92:e1029-e1040.

4. GBD 2016 Multiple Sclerosis Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of multiple sclerosis 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(3):269-285.

5. GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(5):459-480.

6. Solomon AJ, Bourdette DN, Cross AH, et al. The contemporary spectrum of multiple sclerosis misdiagnosis: a multicenter study. Neurology. 2016;87(13):1393-1399.

7. Spain R, Powers K, Murchison C, et al. Lipoic acid in secondary progressive MS: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2017;4(5):e374.

8. Martini DN, Zeeboer E, Hildebrand A, Fling BW, Hugos CL, Cameron MH. ADSTEP: preliminary investigation of a multicomponent walking aid program in people with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(10):2050-2058.

9. Turner AP, Hartoonian N, Sloan AP, et al. Improving fatigue and depression in individuals with multiple sclerosis using telephone-administered physical activity counseling. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84(4):297-309.

10. Haselkorn JK, Hughes C, Rae-Grant A, et al. Summary of comprehensive systematic review: rehabilitation in multiple sclerosis: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2015;85(21):1896-1903.

11. Hirsh AT, Turner AP, Ehde DM, Haselkorn JK. Prevalence and impact of pain in multiple sclerosis: physical and psychologic contributors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(4):646-651.

12. Khurana SR, Bamer AM, Turner AP, et al. The prevalence of overweight and obesity in veterans with multiple sclerosis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;88(2):83-91.

13. Turner AP, Kivlahan DR, Kazis LE, Haselkorn JK. Smoking among veterans with multiple sclerosis: prevalence correlates, quit attempts, and unmet need for services. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(11):1394-1399.

14. Turner AP, Hawkins EJ, Haselkorn JK, Kivlahan DR. Alcohol misuse and multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(5):842-848.

15. Turner AP, Kivlahan DR, Haselkorn JK. Exercise and quality of life among people with multiple sclerosis: looking beyond physical functioning to mental health and participation in life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(3):420-428.

16. Turner AP, Chapko MK, Yanez D, et al. Access to multiple sclerosis specialty care. PM R. 2013;5(12):1044-1050.

17. Gromisch ES, Turner AP, Leipertz SL, Beauvais J, Haselkorn JK. Risk factors for suboptimal medication adherence in persons with multiple sclerosis: development of an electronic health record-based explanatory model for disease-modifying therapy use [published online ahead of print, 2019 Dec 3]. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;S0003-9993(19)31430-3143.

18. Settle JR, Maloni H, Bedra M, Finkelstein J, Zhan M, Wallin M. Monitoring medication adherence in multiple sclerosis using a novel web-based tool. J Telemed Telecare. 2016;22:225-233.

19. Gromisch ES, Turner AP, Leipertz SL, Beauvais J, Haselkorn JK. Who is not coming to clinic? A predictive model of excessive missed appointments in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Rel Dis. In Press.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Multiple Sclerosis Centers of Excellence. Multiple Sclerosis System of Care-VHA Directive 1101.06 and Multiple Sclerosis Centers of Excellence network facilities. https://www.va.gov/MS/veterans/find_a_clinic/index_clinics.asp. Updated February 26, 2020. Accessed March 6, 2020.

2. National MS Society. MS navigator program. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/For-Professionals/Clinical-Care/MS-Navigator-Program. Accessed March 6, 2020.

3. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, et al. The prevalence of MS in the United States: a population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology. 2019;92:e1029-e1040.

4. GBD 2016 Multiple Sclerosis Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of multiple sclerosis 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(3):269-285.

5. GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(5):459-480.

6. Solomon AJ, Bourdette DN, Cross AH, et al. The contemporary spectrum of multiple sclerosis misdiagnosis: a multicenter study. Neurology. 2016;87(13):1393-1399.

7. Spain R, Powers K, Murchison C, et al. Lipoic acid in secondary progressive MS: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2017;4(5):e374.

8. Martini DN, Zeeboer E, Hildebrand A, Fling BW, Hugos CL, Cameron MH. ADSTEP: preliminary investigation of a multicomponent walking aid program in people with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(10):2050-2058.

9. Turner AP, Hartoonian N, Sloan AP, et al. Improving fatigue and depression in individuals with multiple sclerosis using telephone-administered physical activity counseling. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84(4):297-309.

10. Haselkorn JK, Hughes C, Rae-Grant A, et al. Summary of comprehensive systematic review: rehabilitation in multiple sclerosis: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2015;85(21):1896-1903.

11. Hirsh AT, Turner AP, Ehde DM, Haselkorn JK. Prevalence and impact of pain in multiple sclerosis: physical and psychologic contributors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(4):646-651.

12. Khurana SR, Bamer AM, Turner AP, et al. The prevalence of overweight and obesity in veterans with multiple sclerosis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;88(2):83-91.

13. Turner AP, Kivlahan DR, Kazis LE, Haselkorn JK. Smoking among veterans with multiple sclerosis: prevalence correlates, quit attempts, and unmet need for services. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(11):1394-1399.

14. Turner AP, Hawkins EJ, Haselkorn JK, Kivlahan DR. Alcohol misuse and multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(5):842-848.

15. Turner AP, Kivlahan DR, Haselkorn JK. Exercise and quality of life among people with multiple sclerosis: looking beyond physical functioning to mental health and participation in life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(3):420-428.

16. Turner AP, Chapko MK, Yanez D, et al. Access to multiple sclerosis specialty care. PM R. 2013;5(12):1044-1050.

17. Gromisch ES, Turner AP, Leipertz SL, Beauvais J, Haselkorn JK. Risk factors for suboptimal medication adherence in persons with multiple sclerosis: development of an electronic health record-based explanatory model for disease-modifying therapy use [published online ahead of print, 2019 Dec 3]. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;S0003-9993(19)31430-3143.

18. Settle JR, Maloni H, Bedra M, Finkelstein J, Zhan M, Wallin M. Monitoring medication adherence in multiple sclerosis using a novel web-based tool. J Telemed Telecare. 2016;22:225-233.

19. Gromisch ES, Turner AP, Leipertz SL, Beauvais J, Haselkorn JK. Who is not coming to clinic? A predictive model of excessive missed appointments in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Rel Dis. In Press.