User login

The VA MS Surveillance Registry combines a traditional MS registry with individual clinical and utilization data within the largest integrated health system in the US.

A number of large registries exist for multiple sclerosis (MS) in North America and Europe. The Scandinavian countries have some of the longest running and integrated MS registries to date. The Danish MS Registry was initiated in 1948 and has been consistently maintained to track MS epidemiologic trends.2 Similar databases exist in Swedenand Norway that were created in the later 20th century.3,4 The Rochester Epidemiology Project, launched by Len Kurland at the Mayo Clinic, has tracked the morbidity of MS and many other conditions in Olmsted county Minnesota for > 60 years.5

The Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Ontario, and Manitoba also have long standing MS registries.6-8 Other North American MS registries have gathered state-wide cases, such as the New York State MS Consortium.9 Some registries have gathered a population-based sample throughout the US, such as the Sonya Slifka MS Study.10 The North American Research Consortium on MS (NARCOMS) registry is a patient-driven registry within the US that has enrolled > 30,000 cases.11 The MSBase is the largest online registry to date utilizing data from several countries.12 The MS Bioscreen, based at the University of California San Francisco, is a recent effort to create a longitudinal clinical dataset.13 This electronic registry integrates clinical disease morbidity scales, neuroimaging, genetics and laboratory data for individual patients with the goal of providing predictive tools.

The US military provides a unique population to study MS and has the oldest and largest nation-wide MS cohort in existence starting with World War I service members and continuing through the recent Gulf War Era.14 With the advent of EHRs in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration (VHA) in the mid-1990s and large clinical databases, the possibility of an integrated registry for chronic conditions was created. In this report, we describe the creation of the VA MS Surveillance Registry (MSSR) and the initial roll out to several VA medical centers within the MS Center of Excellence (MSCoE). The MSSR is a unique platform with potential for improving MS patient care and clinical research.

Methods

The MSSR was designed by MSCoE health care providers in conjunction with IT specialists from the VA Northwest Innovation Center. Between 2012 and 2013, the team developed and tested a core template for data entry and refined an efficient data dashboard display to optimize clinical decisions. IT programmers created data entry templates that were tested by 4 to 5 clinicians who provided feedback in biweekly meetings. Technical problems were addressed and enhancements added and the trial process was repeated.

After creation of the prototype MS Assessment Tool (MSAT) data entry template that fed into the prototype MSSR, our team received a grant in 2013 for national development and sustainment. The MSSR was established on the VA Converged Registries Solution (CRS) platform, which is a hardware and software architecture designed to host individual clinical registries and eliminate duplicative development effort while maximizing the ability to create new patient registries. The common platform includes a relational database, Health Level 7 messaging, software classes, security modules, extraction services, and other components. The CR obtains data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), directly from the Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VISTA) and via direct user input using MSAT.

From 2016 to 2019, data from patients with MS followed in several VA MS regional programs were inputted into MSSR. A roll-out process to start patient data entry at VA medical centers began in 2017 that included an orientation, technical support, and quality assurance review. Twelve sites from Veteran Integrated Service Network (VISN) 5 (mid-Atlantic) and VISN 20 (Pacific Northwest) were included in the initial roll-out.

Results

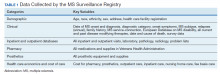

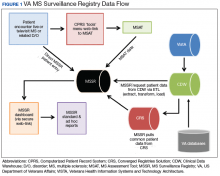

After a live or remote telehealth or telephone visit, a clinician can access MSAT from the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) or directly from the MSSR online portal (Figure 1). The tool uses radio buttons and pull-down menus and takes about 5 to 15 minutes to complete with a list of required variables. Data is auto-saved for efficiency, and the key variables that are collected in MSAT are noted in Table 1. The MSAT subsequently creates a text integration utility progress note with health factors that is processed through an integration engine and eventually transmitted to VISTA and becomes part of the EHR and available to all health care providers involved in that patient’s care. Additionally, data from VA outpatient and inpatient utilization files, pharmacy, prosthetics, laboratory, and radiology databases are included in the CDW and are included in MSSR. With data from 1998 to the present, the MSAT and CDW databases can provide longitudinal data analysis.

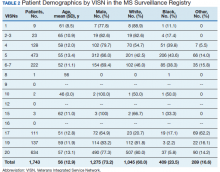

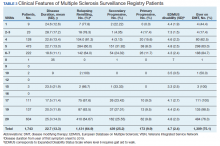

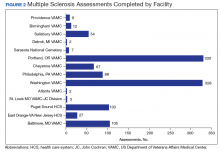

Between 18,000 and 20,000 patients with MS are evaluated in the VHA annually, and 56,000 unique patients have been assessed since 1998. From 2016 to 2019, 1,743 patients with MS or related disorders were enrolled in MSSR (Table 2 and Figure 2). The mean (SD) age of patients was 56.0 (12.9) years and the male:female ratio was 2.7. Racial minorities make up 40% of the cohort. Among those with definite and possible MS, the mean disease duration was 22.7 years and the mean (SD) European Database for MS disability score was 4.7 (2.4) (Table 3). Three-quarters of the MSSR cohort have used ≥ 1 MS disease modifying therapy and 65% were classified as relapsing-remitting MS. An electronic dashboard was developed for health care providers to easily access demographic and clinical data for individuals and groups of patients (Figure 3). Standard and ad hoc reports can be generated from the MSSR. Larger longitudinal analyses can be performed with MSAT and clinical data from CDW. Data on comorbid conditions, pharmacy, radiology and prosthetics utilization, outpatient clinic and inpatient admission can be accessed for each patient or a group of patients.

In 2015, MSCoE published a larger national survey of the VA MS population.15 This study revealed that the majority of clinical features and demographics of the MSSR were not significantly different from other major US MS registries including the North American Research Committee on MS, the New York State MS Consortium, and the Sonya Slifka Study.16-18

Discussion

The MSSR is novel in that it combines a traditional MS registry with individual clinical and utilization data within the largest integrated health system in the US. This new registry leverages the existing databases related to cost of care, utilization, and pharmacy services to provide surveillance tools for longitudinal follow-up of the MS population within the VHA. Because the structure of the MSAT and MSSR were developed in a partnership between IT developers and clinicians, there has been mutual buy-in for those who use it and maintain it. This registry can be a test bed for standardized patient outcomes including the recently released MS Quality measures from the American Academy of Neurology.19

To achieve greater numbers across populations, there has been efforts in Europe to combine registries into a common European Register for MS. A recent survey found that although many European registries were heterogeneous, it would be possible to have a minimum common data set for limited epidemiologic studies.20 Still many registries do not have environmental or genetic data to evaluate etiologic questions.21 Additionally, most registries are not set up to evaluate cost or quality of care within a health care system.

Recommendations for maximizing the impact of existing MS registries were recently released by a panel of MS clinicians and researchers.22 The first recommendation was to create a broad network of registries that would communicate and collaborate. This group of MS registries would have strategic oversight and direction that would greatly streamline and leverage existing and future efforts. Second, registries should standardize data collection and management thereby enhancing the ability to share data and perform meta-analyses with aggregated data. Third, the collection of physician- and patient-reported outcomes should be encouraged to provide a more complete picture of MS. Finally, registries should prioritize research questions and utilize new technologies for data collection. These recommendations would help to coordinate existing registries and accelerate knowledge discovery.

The MSSR will contribute to the growing registry network of data. The MSSR can address questions about clinical outcomes, cost, quality with a growing data repository and linked biobank. Based on the CR platform, the MSSR allows for integration with other VA clinical registries, including registries for traumatic brain injuries, oncology, HIV, hepatitis C virus, and eye injuries. Identifying case outcomes related to other registries is optimized with the CR common structure.

Conclusion

The MSSR has been a useful tool for clinicians managing individual patients and their regional referral populations with real-time access to clinical and utilization data. It will also be a useful research tool in tracking epidemiological trends for the military population. The MSSR has enhanced clinical management of MS and serves as a national source for clinical outcomes.

1. Flachenecker P. Multiple sclerosis databases: present and future. Eur Neurol. 2014;72(suppl 1):29-31.

2. Koch-Henriksen N, Magyari M, Laursen B. Registers of multiple sclerosis in Denmark. Acta Neurol Scand. 2015;132(199):4-10.

3. Alping P, Piehl F, Langer-Gould A, Frisell T; COMBAT-MS Study Group. Validation of the Swedish Multiple Sclerosis Register: further improving a resource for pharmacoepidemiologic evaluations. Epidemiology. 2019;30(2):230-233.

4. Benjaminsen E, Myhr KM, Grytten N, Alstadhaug KB. Validation of the multiple sclerosis diagnosis in the Norwegian Patient Registry. Brain Behav. 2019;9(11):e01422.

5. Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ 3rd. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1202-1213.

6. Kingwell E, Zhu F, Marrie RA, et al. High incidence and increasing prevalence of multiple sclerosis in British Columbia, Canada: findings from over two decades (1991-2010). J Neurol. 2015;262(10):2352-2363.

7. Scalfari A, Neuhaus A, Degenhardt A, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study 10: relapses and long-term disability. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 7):1914-1929.

8. Mahmud SM, Bozat-Emre S, Mostaço-Guidolin LC, Marrie RA. Registry cohort study to determine risk for multiple sclerosis after vaccination for pandemic influenza A(H1N1) with Arepanrix, Manitoba, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(7):1267-1274.

9. Kister I, Chamot E, Bacon JH, Cutter G, Herbert J; New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Trend for decreasing Multiple Sclerosis Severity Scores (MSSS) with increasing calendar year of enrollment into the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Mult Scler. 2011;17(6):725-733.

10. Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden L, Perloffp J, Srinath KP, Hoaglin DC. The Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study: methods and sample characteristics. Mult Scler. 2006;12(1):24-38.

11. Fox RJ, Salter A, Alster JM, et al. Risk tolerance to MS therapies: survey results from the NARCOMS registry. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015;4(3):241-249.

12. Kalincik T, Butzkueven H. The MSBase registry: Informing clinical practice. Mult Scler. 2019;25(14):1828-1834.

13. Gourraud PA, Henry RG, Cree BA, et al. Precision medicine in chronic disease management: the multiple sclerosis BioScreen. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(5):633-642.

14. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Coffman P, et al. The Gulf War era multiple sclerosis cohort: age and incidence rates by race, sex and service. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 6):1778-1785.

15. Culpepper WJ, Wallin MT, Magder LS, et al. VHA Multiple Sclerosis Surveillance Registry and its similarities to other contemporary multiple sclerosis cohorts. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015;52(3):263-272.

16. Salter A, Stahmann A, Ellenberger D, et al. Data harmonization for collaborative research among MS registries: a case study in employment [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 12]. Mult Scler. 2020;1352458520910499.

17. Vaughn CB, Kavak KS, Dwyer MG, et al. Fatigue at enrollment predicts EDSS worsening in the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Mult Scler. 2020;26(1):99-108.

18. Minden SL, Kinkel RP, Machado HT, et al. Use and cost of disease-modifying therapies by Sonya Slifka Study participants: has anything really changed since 2000 and 2009? Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2019;5(1):2055217318820888.

19. Rae-Grant A, Bennett A, Sanders AE, Phipps M, Cheng E, Bever C. Quality improvement in neurology: multiple sclerosis quality measures: Executive summary [published correction appears in Neurology. 2016;86(15):1465]. Neurology. 2015;85(21):1904-1908.

20. Flachenecker P, Buckow K, Pugliatti M, et al; EUReMS Consortium. Multiple sclerosis registries in Europe - results of a systematic survey. Mult Scler. 2014;20(11):1523-1532.

21. Traboulsee A, McMullen K. How useful are MS registries?. Mult Scler. 2014;20(11):1423-1424.

22. Bebo BF Jr, Fox RJ, Lee K, Utz U, Thompson AJ. Landscape of MS patient cohorts and registries: Recommendations for maximizing impact. Mult Scler. 2018;24(5):579-586.

The VA MS Surveillance Registry combines a traditional MS registry with individual clinical and utilization data within the largest integrated health system in the US.

The VA MS Surveillance Registry combines a traditional MS registry with individual clinical and utilization data within the largest integrated health system in the US.

A number of large registries exist for multiple sclerosis (MS) in North America and Europe. The Scandinavian countries have some of the longest running and integrated MS registries to date. The Danish MS Registry was initiated in 1948 and has been consistently maintained to track MS epidemiologic trends.2 Similar databases exist in Swedenand Norway that were created in the later 20th century.3,4 The Rochester Epidemiology Project, launched by Len Kurland at the Mayo Clinic, has tracked the morbidity of MS and many other conditions in Olmsted county Minnesota for > 60 years.5

The Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Ontario, and Manitoba also have long standing MS registries.6-8 Other North American MS registries have gathered state-wide cases, such as the New York State MS Consortium.9 Some registries have gathered a population-based sample throughout the US, such as the Sonya Slifka MS Study.10 The North American Research Consortium on MS (NARCOMS) registry is a patient-driven registry within the US that has enrolled > 30,000 cases.11 The MSBase is the largest online registry to date utilizing data from several countries.12 The MS Bioscreen, based at the University of California San Francisco, is a recent effort to create a longitudinal clinical dataset.13 This electronic registry integrates clinical disease morbidity scales, neuroimaging, genetics and laboratory data for individual patients with the goal of providing predictive tools.

The US military provides a unique population to study MS and has the oldest and largest nation-wide MS cohort in existence starting with World War I service members and continuing through the recent Gulf War Era.14 With the advent of EHRs in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration (VHA) in the mid-1990s and large clinical databases, the possibility of an integrated registry for chronic conditions was created. In this report, we describe the creation of the VA MS Surveillance Registry (MSSR) and the initial roll out to several VA medical centers within the MS Center of Excellence (MSCoE). The MSSR is a unique platform with potential for improving MS patient care and clinical research.

Methods

The MSSR was designed by MSCoE health care providers in conjunction with IT specialists from the VA Northwest Innovation Center. Between 2012 and 2013, the team developed and tested a core template for data entry and refined an efficient data dashboard display to optimize clinical decisions. IT programmers created data entry templates that were tested by 4 to 5 clinicians who provided feedback in biweekly meetings. Technical problems were addressed and enhancements added and the trial process was repeated.

After creation of the prototype MS Assessment Tool (MSAT) data entry template that fed into the prototype MSSR, our team received a grant in 2013 for national development and sustainment. The MSSR was established on the VA Converged Registries Solution (CRS) platform, which is a hardware and software architecture designed to host individual clinical registries and eliminate duplicative development effort while maximizing the ability to create new patient registries. The common platform includes a relational database, Health Level 7 messaging, software classes, security modules, extraction services, and other components. The CR obtains data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), directly from the Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VISTA) and via direct user input using MSAT.

From 2016 to 2019, data from patients with MS followed in several VA MS regional programs were inputted into MSSR. A roll-out process to start patient data entry at VA medical centers began in 2017 that included an orientation, technical support, and quality assurance review. Twelve sites from Veteran Integrated Service Network (VISN) 5 (mid-Atlantic) and VISN 20 (Pacific Northwest) were included in the initial roll-out.

Results

After a live or remote telehealth or telephone visit, a clinician can access MSAT from the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) or directly from the MSSR online portal (Figure 1). The tool uses radio buttons and pull-down menus and takes about 5 to 15 minutes to complete with a list of required variables. Data is auto-saved for efficiency, and the key variables that are collected in MSAT are noted in Table 1. The MSAT subsequently creates a text integration utility progress note with health factors that is processed through an integration engine and eventually transmitted to VISTA and becomes part of the EHR and available to all health care providers involved in that patient’s care. Additionally, data from VA outpatient and inpatient utilization files, pharmacy, prosthetics, laboratory, and radiology databases are included in the CDW and are included in MSSR. With data from 1998 to the present, the MSAT and CDW databases can provide longitudinal data analysis.

Between 18,000 and 20,000 patients with MS are evaluated in the VHA annually, and 56,000 unique patients have been assessed since 1998. From 2016 to 2019, 1,743 patients with MS or related disorders were enrolled in MSSR (Table 2 and Figure 2). The mean (SD) age of patients was 56.0 (12.9) years and the male:female ratio was 2.7. Racial minorities make up 40% of the cohort. Among those with definite and possible MS, the mean disease duration was 22.7 years and the mean (SD) European Database for MS disability score was 4.7 (2.4) (Table 3). Three-quarters of the MSSR cohort have used ≥ 1 MS disease modifying therapy and 65% were classified as relapsing-remitting MS. An electronic dashboard was developed for health care providers to easily access demographic and clinical data for individuals and groups of patients (Figure 3). Standard and ad hoc reports can be generated from the MSSR. Larger longitudinal analyses can be performed with MSAT and clinical data from CDW. Data on comorbid conditions, pharmacy, radiology and prosthetics utilization, outpatient clinic and inpatient admission can be accessed for each patient or a group of patients.

In 2015, MSCoE published a larger national survey of the VA MS population.15 This study revealed that the majority of clinical features and demographics of the MSSR were not significantly different from other major US MS registries including the North American Research Committee on MS, the New York State MS Consortium, and the Sonya Slifka Study.16-18

Discussion

The MSSR is novel in that it combines a traditional MS registry with individual clinical and utilization data within the largest integrated health system in the US. This new registry leverages the existing databases related to cost of care, utilization, and pharmacy services to provide surveillance tools for longitudinal follow-up of the MS population within the VHA. Because the structure of the MSAT and MSSR were developed in a partnership between IT developers and clinicians, there has been mutual buy-in for those who use it and maintain it. This registry can be a test bed for standardized patient outcomes including the recently released MS Quality measures from the American Academy of Neurology.19

To achieve greater numbers across populations, there has been efforts in Europe to combine registries into a common European Register for MS. A recent survey found that although many European registries were heterogeneous, it would be possible to have a minimum common data set for limited epidemiologic studies.20 Still many registries do not have environmental or genetic data to evaluate etiologic questions.21 Additionally, most registries are not set up to evaluate cost or quality of care within a health care system.

Recommendations for maximizing the impact of existing MS registries were recently released by a panel of MS clinicians and researchers.22 The first recommendation was to create a broad network of registries that would communicate and collaborate. This group of MS registries would have strategic oversight and direction that would greatly streamline and leverage existing and future efforts. Second, registries should standardize data collection and management thereby enhancing the ability to share data and perform meta-analyses with aggregated data. Third, the collection of physician- and patient-reported outcomes should be encouraged to provide a more complete picture of MS. Finally, registries should prioritize research questions and utilize new technologies for data collection. These recommendations would help to coordinate existing registries and accelerate knowledge discovery.

The MSSR will contribute to the growing registry network of data. The MSSR can address questions about clinical outcomes, cost, quality with a growing data repository and linked biobank. Based on the CR platform, the MSSR allows for integration with other VA clinical registries, including registries for traumatic brain injuries, oncology, HIV, hepatitis C virus, and eye injuries. Identifying case outcomes related to other registries is optimized with the CR common structure.

Conclusion

The MSSR has been a useful tool for clinicians managing individual patients and their regional referral populations with real-time access to clinical and utilization data. It will also be a useful research tool in tracking epidemiological trends for the military population. The MSSR has enhanced clinical management of MS and serves as a national source for clinical outcomes.

A number of large registries exist for multiple sclerosis (MS) in North America and Europe. The Scandinavian countries have some of the longest running and integrated MS registries to date. The Danish MS Registry was initiated in 1948 and has been consistently maintained to track MS epidemiologic trends.2 Similar databases exist in Swedenand Norway that were created in the later 20th century.3,4 The Rochester Epidemiology Project, launched by Len Kurland at the Mayo Clinic, has tracked the morbidity of MS and many other conditions in Olmsted county Minnesota for > 60 years.5

The Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Ontario, and Manitoba also have long standing MS registries.6-8 Other North American MS registries have gathered state-wide cases, such as the New York State MS Consortium.9 Some registries have gathered a population-based sample throughout the US, such as the Sonya Slifka MS Study.10 The North American Research Consortium on MS (NARCOMS) registry is a patient-driven registry within the US that has enrolled > 30,000 cases.11 The MSBase is the largest online registry to date utilizing data from several countries.12 The MS Bioscreen, based at the University of California San Francisco, is a recent effort to create a longitudinal clinical dataset.13 This electronic registry integrates clinical disease morbidity scales, neuroimaging, genetics and laboratory data for individual patients with the goal of providing predictive tools.

The US military provides a unique population to study MS and has the oldest and largest nation-wide MS cohort in existence starting with World War I service members and continuing through the recent Gulf War Era.14 With the advent of EHRs in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration (VHA) in the mid-1990s and large clinical databases, the possibility of an integrated registry for chronic conditions was created. In this report, we describe the creation of the VA MS Surveillance Registry (MSSR) and the initial roll out to several VA medical centers within the MS Center of Excellence (MSCoE). The MSSR is a unique platform with potential for improving MS patient care and clinical research.

Methods

The MSSR was designed by MSCoE health care providers in conjunction with IT specialists from the VA Northwest Innovation Center. Between 2012 and 2013, the team developed and tested a core template for data entry and refined an efficient data dashboard display to optimize clinical decisions. IT programmers created data entry templates that were tested by 4 to 5 clinicians who provided feedback in biweekly meetings. Technical problems were addressed and enhancements added and the trial process was repeated.

After creation of the prototype MS Assessment Tool (MSAT) data entry template that fed into the prototype MSSR, our team received a grant in 2013 for national development and sustainment. The MSSR was established on the VA Converged Registries Solution (CRS) platform, which is a hardware and software architecture designed to host individual clinical registries and eliminate duplicative development effort while maximizing the ability to create new patient registries. The common platform includes a relational database, Health Level 7 messaging, software classes, security modules, extraction services, and other components. The CR obtains data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), directly from the Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VISTA) and via direct user input using MSAT.

From 2016 to 2019, data from patients with MS followed in several VA MS regional programs were inputted into MSSR. A roll-out process to start patient data entry at VA medical centers began in 2017 that included an orientation, technical support, and quality assurance review. Twelve sites from Veteran Integrated Service Network (VISN) 5 (mid-Atlantic) and VISN 20 (Pacific Northwest) were included in the initial roll-out.

Results

After a live or remote telehealth or telephone visit, a clinician can access MSAT from the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) or directly from the MSSR online portal (Figure 1). The tool uses radio buttons and pull-down menus and takes about 5 to 15 minutes to complete with a list of required variables. Data is auto-saved for efficiency, and the key variables that are collected in MSAT are noted in Table 1. The MSAT subsequently creates a text integration utility progress note with health factors that is processed through an integration engine and eventually transmitted to VISTA and becomes part of the EHR and available to all health care providers involved in that patient’s care. Additionally, data from VA outpatient and inpatient utilization files, pharmacy, prosthetics, laboratory, and radiology databases are included in the CDW and are included in MSSR. With data from 1998 to the present, the MSAT and CDW databases can provide longitudinal data analysis.

Between 18,000 and 20,000 patients with MS are evaluated in the VHA annually, and 56,000 unique patients have been assessed since 1998. From 2016 to 2019, 1,743 patients with MS or related disorders were enrolled in MSSR (Table 2 and Figure 2). The mean (SD) age of patients was 56.0 (12.9) years and the male:female ratio was 2.7. Racial minorities make up 40% of the cohort. Among those with definite and possible MS, the mean disease duration was 22.7 years and the mean (SD) European Database for MS disability score was 4.7 (2.4) (Table 3). Three-quarters of the MSSR cohort have used ≥ 1 MS disease modifying therapy and 65% were classified as relapsing-remitting MS. An electronic dashboard was developed for health care providers to easily access demographic and clinical data for individuals and groups of patients (Figure 3). Standard and ad hoc reports can be generated from the MSSR. Larger longitudinal analyses can be performed with MSAT and clinical data from CDW. Data on comorbid conditions, pharmacy, radiology and prosthetics utilization, outpatient clinic and inpatient admission can be accessed for each patient or a group of patients.

In 2015, MSCoE published a larger national survey of the VA MS population.15 This study revealed that the majority of clinical features and demographics of the MSSR were not significantly different from other major US MS registries including the North American Research Committee on MS, the New York State MS Consortium, and the Sonya Slifka Study.16-18

Discussion

The MSSR is novel in that it combines a traditional MS registry with individual clinical and utilization data within the largest integrated health system in the US. This new registry leverages the existing databases related to cost of care, utilization, and pharmacy services to provide surveillance tools for longitudinal follow-up of the MS population within the VHA. Because the structure of the MSAT and MSSR were developed in a partnership between IT developers and clinicians, there has been mutual buy-in for those who use it and maintain it. This registry can be a test bed for standardized patient outcomes including the recently released MS Quality measures from the American Academy of Neurology.19

To achieve greater numbers across populations, there has been efforts in Europe to combine registries into a common European Register for MS. A recent survey found that although many European registries were heterogeneous, it would be possible to have a minimum common data set for limited epidemiologic studies.20 Still many registries do not have environmental or genetic data to evaluate etiologic questions.21 Additionally, most registries are not set up to evaluate cost or quality of care within a health care system.

Recommendations for maximizing the impact of existing MS registries were recently released by a panel of MS clinicians and researchers.22 The first recommendation was to create a broad network of registries that would communicate and collaborate. This group of MS registries would have strategic oversight and direction that would greatly streamline and leverage existing and future efforts. Second, registries should standardize data collection and management thereby enhancing the ability to share data and perform meta-analyses with aggregated data. Third, the collection of physician- and patient-reported outcomes should be encouraged to provide a more complete picture of MS. Finally, registries should prioritize research questions and utilize new technologies for data collection. These recommendations would help to coordinate existing registries and accelerate knowledge discovery.

The MSSR will contribute to the growing registry network of data. The MSSR can address questions about clinical outcomes, cost, quality with a growing data repository and linked biobank. Based on the CR platform, the MSSR allows for integration with other VA clinical registries, including registries for traumatic brain injuries, oncology, HIV, hepatitis C virus, and eye injuries. Identifying case outcomes related to other registries is optimized with the CR common structure.

Conclusion

The MSSR has been a useful tool for clinicians managing individual patients and their regional referral populations with real-time access to clinical and utilization data. It will also be a useful research tool in tracking epidemiological trends for the military population. The MSSR has enhanced clinical management of MS and serves as a national source for clinical outcomes.

1. Flachenecker P. Multiple sclerosis databases: present and future. Eur Neurol. 2014;72(suppl 1):29-31.

2. Koch-Henriksen N, Magyari M, Laursen B. Registers of multiple sclerosis in Denmark. Acta Neurol Scand. 2015;132(199):4-10.

3. Alping P, Piehl F, Langer-Gould A, Frisell T; COMBAT-MS Study Group. Validation of the Swedish Multiple Sclerosis Register: further improving a resource for pharmacoepidemiologic evaluations. Epidemiology. 2019;30(2):230-233.

4. Benjaminsen E, Myhr KM, Grytten N, Alstadhaug KB. Validation of the multiple sclerosis diagnosis in the Norwegian Patient Registry. Brain Behav. 2019;9(11):e01422.

5. Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ 3rd. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1202-1213.

6. Kingwell E, Zhu F, Marrie RA, et al. High incidence and increasing prevalence of multiple sclerosis in British Columbia, Canada: findings from over two decades (1991-2010). J Neurol. 2015;262(10):2352-2363.

7. Scalfari A, Neuhaus A, Degenhardt A, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study 10: relapses and long-term disability. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 7):1914-1929.

8. Mahmud SM, Bozat-Emre S, Mostaço-Guidolin LC, Marrie RA. Registry cohort study to determine risk for multiple sclerosis after vaccination for pandemic influenza A(H1N1) with Arepanrix, Manitoba, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(7):1267-1274.

9. Kister I, Chamot E, Bacon JH, Cutter G, Herbert J; New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Trend for decreasing Multiple Sclerosis Severity Scores (MSSS) with increasing calendar year of enrollment into the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Mult Scler. 2011;17(6):725-733.

10. Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden L, Perloffp J, Srinath KP, Hoaglin DC. The Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study: methods and sample characteristics. Mult Scler. 2006;12(1):24-38.

11. Fox RJ, Salter A, Alster JM, et al. Risk tolerance to MS therapies: survey results from the NARCOMS registry. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015;4(3):241-249.

12. Kalincik T, Butzkueven H. The MSBase registry: Informing clinical practice. Mult Scler. 2019;25(14):1828-1834.

13. Gourraud PA, Henry RG, Cree BA, et al. Precision medicine in chronic disease management: the multiple sclerosis BioScreen. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(5):633-642.

14. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Coffman P, et al. The Gulf War era multiple sclerosis cohort: age and incidence rates by race, sex and service. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 6):1778-1785.

15. Culpepper WJ, Wallin MT, Magder LS, et al. VHA Multiple Sclerosis Surveillance Registry and its similarities to other contemporary multiple sclerosis cohorts. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015;52(3):263-272.

16. Salter A, Stahmann A, Ellenberger D, et al. Data harmonization for collaborative research among MS registries: a case study in employment [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 12]. Mult Scler. 2020;1352458520910499.

17. Vaughn CB, Kavak KS, Dwyer MG, et al. Fatigue at enrollment predicts EDSS worsening in the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Mult Scler. 2020;26(1):99-108.

18. Minden SL, Kinkel RP, Machado HT, et al. Use and cost of disease-modifying therapies by Sonya Slifka Study participants: has anything really changed since 2000 and 2009? Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2019;5(1):2055217318820888.

19. Rae-Grant A, Bennett A, Sanders AE, Phipps M, Cheng E, Bever C. Quality improvement in neurology: multiple sclerosis quality measures: Executive summary [published correction appears in Neurology. 2016;86(15):1465]. Neurology. 2015;85(21):1904-1908.

20. Flachenecker P, Buckow K, Pugliatti M, et al; EUReMS Consortium. Multiple sclerosis registries in Europe - results of a systematic survey. Mult Scler. 2014;20(11):1523-1532.

21. Traboulsee A, McMullen K. How useful are MS registries?. Mult Scler. 2014;20(11):1423-1424.

22. Bebo BF Jr, Fox RJ, Lee K, Utz U, Thompson AJ. Landscape of MS patient cohorts and registries: Recommendations for maximizing impact. Mult Scler. 2018;24(5):579-586.

1. Flachenecker P. Multiple sclerosis databases: present and future. Eur Neurol. 2014;72(suppl 1):29-31.

2. Koch-Henriksen N, Magyari M, Laursen B. Registers of multiple sclerosis in Denmark. Acta Neurol Scand. 2015;132(199):4-10.

3. Alping P, Piehl F, Langer-Gould A, Frisell T; COMBAT-MS Study Group. Validation of the Swedish Multiple Sclerosis Register: further improving a resource for pharmacoepidemiologic evaluations. Epidemiology. 2019;30(2):230-233.

4. Benjaminsen E, Myhr KM, Grytten N, Alstadhaug KB. Validation of the multiple sclerosis diagnosis in the Norwegian Patient Registry. Brain Behav. 2019;9(11):e01422.

5. Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ 3rd. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1202-1213.

6. Kingwell E, Zhu F, Marrie RA, et al. High incidence and increasing prevalence of multiple sclerosis in British Columbia, Canada: findings from over two decades (1991-2010). J Neurol. 2015;262(10):2352-2363.

7. Scalfari A, Neuhaus A, Degenhardt A, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study 10: relapses and long-term disability. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 7):1914-1929.

8. Mahmud SM, Bozat-Emre S, Mostaço-Guidolin LC, Marrie RA. Registry cohort study to determine risk for multiple sclerosis after vaccination for pandemic influenza A(H1N1) with Arepanrix, Manitoba, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(7):1267-1274.

9. Kister I, Chamot E, Bacon JH, Cutter G, Herbert J; New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Trend for decreasing Multiple Sclerosis Severity Scores (MSSS) with increasing calendar year of enrollment into the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Mult Scler. 2011;17(6):725-733.

10. Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden L, Perloffp J, Srinath KP, Hoaglin DC. The Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study: methods and sample characteristics. Mult Scler. 2006;12(1):24-38.

11. Fox RJ, Salter A, Alster JM, et al. Risk tolerance to MS therapies: survey results from the NARCOMS registry. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015;4(3):241-249.

12. Kalincik T, Butzkueven H. The MSBase registry: Informing clinical practice. Mult Scler. 2019;25(14):1828-1834.

13. Gourraud PA, Henry RG, Cree BA, et al. Precision medicine in chronic disease management: the multiple sclerosis BioScreen. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(5):633-642.

14. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Coffman P, et al. The Gulf War era multiple sclerosis cohort: age and incidence rates by race, sex and service. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 6):1778-1785.

15. Culpepper WJ, Wallin MT, Magder LS, et al. VHA Multiple Sclerosis Surveillance Registry and its similarities to other contemporary multiple sclerosis cohorts. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015;52(3):263-272.

16. Salter A, Stahmann A, Ellenberger D, et al. Data harmonization for collaborative research among MS registries: a case study in employment [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 12]. Mult Scler. 2020;1352458520910499.

17. Vaughn CB, Kavak KS, Dwyer MG, et al. Fatigue at enrollment predicts EDSS worsening in the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Mult Scler. 2020;26(1):99-108.

18. Minden SL, Kinkel RP, Machado HT, et al. Use and cost of disease-modifying therapies by Sonya Slifka Study participants: has anything really changed since 2000 and 2009? Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2019;5(1):2055217318820888.

19. Rae-Grant A, Bennett A, Sanders AE, Phipps M, Cheng E, Bever C. Quality improvement in neurology: multiple sclerosis quality measures: Executive summary [published correction appears in Neurology. 2016;86(15):1465]. Neurology. 2015;85(21):1904-1908.

20. Flachenecker P, Buckow K, Pugliatti M, et al; EUReMS Consortium. Multiple sclerosis registries in Europe - results of a systematic survey. Mult Scler. 2014;20(11):1523-1532.

21. Traboulsee A, McMullen K. How useful are MS registries?. Mult Scler. 2014;20(11):1423-1424.

22. Bebo BF Jr, Fox RJ, Lee K, Utz U, Thompson AJ. Landscape of MS patient cohorts and registries: Recommendations for maximizing impact. Mult Scler. 2018;24(5):579-586.