User login

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Multiple Sclerosis Care for Veterans

The following is a lightly edited transcript of a teleconference recorded in February 2021.

How has COVID impacted Veterans with multiple sclerosis?

Mitchell Wallin, MD, MPH: There has been a lot of concern in the multiple sclerosis (MS) patient community about getting infected with COVID-19 and what to do about it. Now that there are vaccines, the concern is whether and how to take a vaccine. At least here, in the Washington DC/Baltimore area where I practice, we have seen many veterans being hospitalized with COVID-19, some with multiple sclerosis (MS), and some who have died of COVID-19. So, there has been a lot of fear, especially in veterans that are older with comorbid diseases.

Rebecca Spain, MD, MSPH: There also has been an impact on our ability to provide care to our veterans with MS. There are challenges having them come into the office or providing virtual care. There are additional challenges and concerns this year about making changes in MS medications because we can’t see patients in person to or understand their needs or current status of their MS. So, providing care has been a challenge this year as well.

There has also been an impact on our day to day lives, like there has been for all of us, from the lockdown particularly not being able to exercise and socialize as much. There have been physical and social and emotional tolls that this disease has taken on veterans with MS.

Jodie Haselkorn, MD, MPH: The survivors of COVID-19, that are transferred to an inpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation program unit to address impairments related to the cardiopulmonary, immobility, psychological impacts and other medical complications are highly motivated to work with the team to achieve a safe discharge. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Rehabilitation Services has much to offer them.

Heidi Maloni, PhD, NP: Veterans with MS are not at greater risk because they are diagnosed with MS. But, their comorbidities such as hypertension, obesity, or factors such as older age and increased disability can increase the risk of COVID-19 infection and poorer outcomes if infected. might place them at greater risk.

Veterans have asked “Am I at greater risk? Do I need to do something more to protect myself?” I have had innumerable veterans call and ask whether I can write them letters for their employer to ensure that they work at home longer rather than go into the workplace because they’re very nervous and don’t feel confident that masking and distancing is really going to be protective.

Mitchell Wallin: We are analyzing some of our data in the VA health care system related to COVID-19 infections in the MS population. We can’t say for sure what are numbers are, but our rates of infection and hospitalization are higher than the general population and we will soon have a report. We have a majority male population, which is different from the general MS population, which is predominantly female. The proportion of minority patients in VA mirrors those of the US population. These demographic factors along with a high level of comorbid disease put veterans at high risk for acquiring COVID-19. So, in some ways it’s hard to compare when you look at reports from other countries or the US National MS-COVID-19 Registry, which captures a population that is predominantly female. In the VA, our age range spans from the 20s to almost 100 years. We must understand our population to prevent COVID-19 and better care for the most vulnerable.

Rebecca Spain: Heidi, my understanding, although the numbers are small, that for the most part, Veterans with MS who are older are at higher risk of complications and death, which is also true of the general population. But that there is an additional risk for people with MS who have higher disability levels. My understanding from reading the literature, was that people with MS needing or requiring a cane to walk or greater assistance for mobility were at a higher risk for COVID-19 complications, including mortality. I have been particularly encouraged that in many places this special population of people with MS are getting vaccinated sooner.

Heidi Maloni: I completely agree, you said it very clearly, Becca. Their disability level puts them at risk

Rebecca Spain: Disability is a comorbidity.

Heidi Maloni: Yes. Just sitting in a wheelchair and not being able to get a full breath or having problems with respiratory effort really does put you at risk for doing well if you were to have COVID-19.

Are there other ancillary impacts from COVID-19 for patients with MS?

Jodie Haselkorn: Individuals who are hospitalized with COVID-19 miss social touch and social support from family and friends. They miss familiar conversations, a hug and having someone hold their hand. The acute phase of the infection limits professional face-to-face interaction with patients due to time and protective garments. There are reports of negative consequences with isolation and social reintegration of the COVID-19 survivors is necessary and a necessary part of rehabilitation.

Mitchell Wallin: For certain procedures (eg, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) or consultations, we need to bring people into the medical center. Many clinical encounters, however, can be done through telemedicine and both the VA and the US Department of Defense systems were set up to execute this type of visit. We had been doing telemedicine for a long time before the pandemic and we were in a better position than a lot of other health systems to shift to a virtual format with COVID-19. We had to ramp up a little bit and get our tools working a little more effectively for all clinics, but I think we were prepared to broadly execute telemedicine clinics for the pandemic.

Jodie Haselkorn: I agree that the he VA infrastructure was ahead of most other health system in terms of readiness for telehealth and maintaining access to care. Not all health care providers (HCPs) were using it, but the system was there, and included a telehealth coordinator in all of the facilities who could gear health care professionals up quickly. Additionally, a system was in place to provide veterans and caregivers with telehealth home equipment and provide training. Another thing that really helped was the MISSION Act. Veterans who have difficulty travelling for an appointment may have the ability to seek care outside of the VA within their own community. They may be able to go into a local facility to get laboratory or radiologic studies done or continue rehabilitation closer to home.

VA MS Registry Data

Rebecca Spain: Mitch, there are many interesting things we can learn about the interplay between COVID-19 and MS using registries such as how it affects people based on rural vs metropolitan living, whether people are living in single family homes or not as a proxy marker for social support, and so on.

Mitchell Wallin: We have both an MS registry to track and follow patients through our clinical network and a specific COVID-19 registry as well in VA. We have identified the MS cases infected with CoVID-19 and are putting them together.

Jodie Haselkorn: There are a number of efforts in mental health that are moving forward to examine depression and in anxiety during COVID-19. Individuals with MS have increased rates of depression and anxiety above that of the general population during usual times. The literature reports an increase in anxiety and depression in general population associated with the pandemic and veterans with MS seem to be reporting these symptoms more frequently as well. We will be able to track use the registry to assess the impacts of COVID-19 on depression and anxiety in Veterans with MS.

Providing MS Care During COVID-19

Jodie Haselkorn: The transition to telehealth in COVID-19 has been surprisingly seamless with some additional training for veterans and HCPs. I initially experienced an inefficiency in my clinic visit productivity. It took me longer to see a veteran because I wasn’t doing telehealth in our clinic with support staff and residents, my examination had to change, my documentation template needed to be restructured, and the coding was different. Sometimes I saw a veteran in clinic the and my next appointment required me to move back to my office in another building for a telehealth appointment. Teaching virtual trainees who also participated in the clinic encounters had its own challenges and rewards. My ‘motor routine’ was disrupted.

Rebecca Spain: There’s a real learning curve for telehealth in terms of how comfortable you feel with the data you get by telephone or video and how reliable that is. There are issues based on technology factors—like the patient’s bandwidth—because determining how smooth their motions are is challenging if you have a jerky, intermittent signal. I learned quickly to always do the physical examination first because I might lose video connection partway through and have to switch to a phone visit!

It’s still an open question, how much are we missing by using a video and not in-person visits. And what are the long-term health outcomes and implications of that? That is something that needs to be studied in neurology where we pride ourselves on the physical examination. When move to a virtual physical examination, is there cost? There are incredible gains using telehealth in terms of convenience and access to care, which may outweigh some of the drawbacks in particular cases.

There are also pandemic challenge in terms of clinic workflow. At VA Portland Health Care System in Oregon, I have 3 clinics for Friday morning: telephone, virtual, and face-to-face clinics. It’s a real struggle for the schedulers. And because of that transition to new system workflows to accommodate this, some patient visits have been dropped, lost, or scheduled incorrectly.

Heidi Maloni: As the nurse in this group, I agree with everything that Becca and Jodie have said about telehealth. But, I have found some benefits, and one of them is a greater intimacy with my patients. What do I mean by that? For instance, if a patient has taken me to their kitchen and opened their cupboard to show me the breakfast cereal, I’m also observing that there’s nothing else in that cupboard other than cereal. I’m also putting some things together about health and wellness. Or, for the first time, I might meet their significant other who can’t come to clinic because they’re working, but they are at home with the patient. And then having that 3-way conversation with the patient and the significant other, that’s kind of opened up my sense of who that person is.

You are right about the neurological examination. It’s challenging to make exacting assessments. When gathering household objects, ice bags and pronged forks to assess sensation, you remember that this exam is subjective and there is meaning in this remote evaluation. But all in all, I have been blessed with telehealth. Patients don’t mind it at all. They’re completely open to the idea. They like the telehealth for the contact they are able to have with their HCP.

Jodie Haselkorn: As you were saying that, Heidi, I thought, I’ve been inside my veterans’ bathrooms virtually and have seen all of their equipment that they have at home. In a face-to-face clinic visit, you don’t have an opportunity to see all their canes and walkers, braces, and other assistive technology. Some of it’s stashed in a closet, some of it under the bed. In a virtual visit, I get to understand why some is not used, what veterans prefer, and see their own innovations for mobility and self-care.

Mitchell Wallin: There’s a typical ritual that patients talk about when they go to a clinic. They check in, sit down, and wait for the nurse to give them their vital signs and set them up in the room. And then they meet with their HCP, and finally they complete the tasks on the checklist. And part of that may mean scheduling an MRI or going to the lab. But some of these handoffs don’t happen as well on telehealth. Maybe we haven’t integrated these segments of a clinical visit into telehealth platforms. But it could be developed, and there could be new neurologic tools to improve the interview and physical examination. Twenty years ago, you couldn’t deposit a check on your phone; but now you can do everything on your phone you could do in a physical bank. With some creativity, we can improve parts of the neurological exam that are currently difficult to assess remotely.

Jodie Haselkorn: I have not used peripherals in video telehealth to home and I would need to become accustomed to their use with current technology and train patients and caregivers. I would like telehealth peripherals such as a stethoscope to listen to the abdomen of a veteran with neurogenic bowel or a user-friendly ultrasound probe to measure postvoid residual urine in an individual with symptoms of neurogenic bladder, in addition to devices that measure walking speed and pulmonary function. I look forward to the development, use, and the incorporation peripherals that will enable a more extensive virtual exam within the home.

What are the MS Centers of Excellence working on now?

Jodie Haselkorn: We are working to understand the healthcare needs of veterans with MS by evaluating not only care for MS within the VA, but also the types and quantity of MS specialty care VA that is being received in the community during the pandemic. Dr. Wallin is also using the registry to lead a telehealth study to capture the variety of different codes that VA health professionals in MS have used to document workload by telehealth, and face-to-face, and telephone encounters.

Rebecca Spain: The MS Center of Excellence (MSCoE) is coming out with note templates to be available for HCPs, which we can refine as we get experience. This is s one way we can promote high standards in MS care by making these ancillary tools more productive.

Jodie Haselkorn: We are looking at different ways to achieve a high-quality virtual examination using standardized examination strategies and patient and caregiver information to prepare for a specialty MS visit.

Rebecca Spain: I would like to, in more of a research setting, study health outcomes using telehealth vs in person and start tracking that long term.

Mitchell Wallin: We can probably do more in terms of standardization, such as the routine patient reported surveys and implementing the new Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers’ International MRI criteria. The COVID pandemic has affected everything in medical care. But we want to have a regular standardized outcome to assess, and if we can start to do some of the standard data collection through telemedicine, it becomes part of our regular clinic data.

Heidi Maloni: We need better technology. You can do electrocardiograms on your watch. Could we do Dinamaps? Could we figure out strength? That’s a wish list.

Jodie Haselkorn: Since the MSCoE is a national program, we were set up to do what we needed to do for education. We were able to continue on with all of our HCP webinars, including the series with the National MS Society (NMSS). We also have a Specialty Care Access Network-Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (SCAN-ECHO) series with the Northwest ECHO VA program and collaborated with the Can Do MS program on patient education as well. We’ve sent out 2 printed newsletters for veterans. The training of HCPs for the future has continued as well. All of our postdoctoral fellows who have finished their programs on time and moved on to either clinical practice or received career development grants to continue their VA careers, a new fellow has joined, and our other fellows are continuing as planned.

The loss that we sustained was in-person meetings. We held MSCoE Regional Program meetings in the East and West that combined education and administrative goals. Both of these were well attended and successful. There was a lot of virtual education available from multiple sources. It was challenging this year was to anticipate what education programming people wanted from MSCoE. Interestingly, a lot of our regional HCPs did not want much more COVID-19 education. They wanted other education and we were able to meet those needs.

Did the pandemic impact the VA MS registry?

Mitchell Wallin: Like any electronic product, the VA MS Surveillance Registry must be maintained, and we have tried to encourage people to use it. Our biggest concern was to identify cases of MS that got infected with COVID-19 and to put those people into the registry. In some cases, Veterans with MS were in locations without a MS clinic. So, we’ve spent a lot more time identifying those cases and adjudicating them to make sure their infection and MS were documented correctly.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the VA healthcare system has been taxed like others and so HCPs have been a lot busier than normal, forcing new workflows. It has been a hard year that way because a lot of health care providers have been doing many other jobs to help maintain patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Heidi Maloni: The impact of COVID-19 has been positive for the registry because we’ve had more opportunities to populate it.

Jodie Haselkorn: Dr. Wallin and the COVID-19 Registry group began building the combined registry at the onset of the pandemic. We have developed the capacity to identify COVID-19 infections in veterans who have MS and receive care in the VA. We entered these cases in the MS Surveillance Registry and have developed a linkage with the COVID-19 national VA registry. We are in the middle of the grunt work part case entry, but it is a rich resource.

How has the pandemic impacted MS research?

Rebecca Spain: COVID-19 has put a big damper on clinical research progress, including some of our MSCoE studies. It has been difficult to have subjects come in for clinical visits. It’s been difficult to get approval for new studies. It’s shifted timelines dramatically, and then that always increases budgets in a time when there’s not a lot of extra money. So, for clinical research, it’s been a real struggle and a strain and an ever-moving target. For laboratory research most, if not all, centers that have laboratory research at some point were closed and have only slowly reopened. Some still haven’t reopened to any kind of research or laboratory. So, it’s been tough, I think, on research in general.

Heidi Maloni: I would say the word is devastating. The pandemic essentially put a stop to in-person research studies. Our hospital was in research phase I, meaning human subjects can only participate in a research study if they are an inpatient or outpatient with an established clinic visit (clinics open to 25% occupancy) or involved in a study requiring safety monitoring, This plan limits risk of COVID-19 exposure.

Rebecca Spain: There is risk for a higher dropout rate of subjects from studies meaning there’s less chance of success for finding answers if enough people don’t stay in. At a certain point, you have to say, “Is this going to be a successful study?”

Jodie Haselkorn: Dr. Spain has done an amazing job leading a multisite, international clinical trial funded by the VA and the NMSS and kept it afloat, despite challenges. The pandemic has had impacts, but the study continues to move towards completion. I’ve appreciated the efforts of the Research Service at VA Puget Sound to ensure that we could safely obtain many of the 12-month outcomes for all the participants enrolled in that study.

Mitchell Wallin: The funding for some of our nonprofit partners, including the Paralyzed Veterans Association (PVA) and the NMSS, has suffered as well and so a lot of their funding programs have closed or been cut back during the pandemic. Despite that, we still have been able to use televideo technology for our clinical and educational programs with our network.

Jodie Haselkorn: MSCoE also does health services and epidemiological studies in addition to clinical trials and that work has continued. Quite a few of the studies that had human subjects in them were completed in terms of data collection, and so those are being analyzed. There will be a drop in funded studies, publications and posters as the pandemic continues and for a recovery period. We have a robust baseline for research productivity and a talented team. We’ll be able to track drop off and recovery over time.

Rebecca Spain: There’s going to be long-term consequences that we don’t see right now, especially for young researchers who have missed getting pilot data which would have led to additional small grants and then later large grants. There’s going to be an education gap that’s going on with all of the kids who are not able to go to school properly. It’s part of that whole swath of lost time and lost opportunity that we will have to deal with.

However, there are going to be some positive changes. We’re now busy designing clinical trials that can be done virtually to minimize any contact with the health facility, and then looking at things like shifting to research ideas that are more focused around health services.

Jodie Haselkorn: Given the current impacts of the pandemic on delivery of health care there is a strong interest in looking at how we can deliver health care in ways that accommodates the consumers and the providers perspectives. In the future we see marked impacts in our abilities to deliver care to Veterans with MS.

As a final thought, I wanted to put in a plug for this talented team. One of our pandemic resolutions was to innovatively find new possibilities and avoid negative focus on small changes. We are fortunate that all our staff have remained healthy and been supportive and compassionate with each other throughout this period. We have met our goals and are still moving forward.

MSCoE has benefited from the supportive leadership of Sharyl Martini, MD, PhD, and Glenn Graham, MD, PhD, in VA Specialty Care Neurology and leadership and space from VA Puget Sound, VA Portland Health Care System, the Washington DC VA Medical Center and VA Maryland Health Care System in Baltimore.

We also have a national advisory system that is actively involved, sets high standards and performs a rigorous annual review. We have rich inputs from the VA National Regional Programs and Veterans. Additionally, we have had the leadership and opportunities to collaborate with outside organizations including, the Consortium of MS Centers, the NMSS, and the PVA. We have been fortunate.

The following is a lightly edited transcript of a teleconference recorded in February 2021.

How has COVID impacted Veterans with multiple sclerosis?

Mitchell Wallin, MD, MPH: There has been a lot of concern in the multiple sclerosis (MS) patient community about getting infected with COVID-19 and what to do about it. Now that there are vaccines, the concern is whether and how to take a vaccine. At least here, in the Washington DC/Baltimore area where I practice, we have seen many veterans being hospitalized with COVID-19, some with multiple sclerosis (MS), and some who have died of COVID-19. So, there has been a lot of fear, especially in veterans that are older with comorbid diseases.

Rebecca Spain, MD, MSPH: There also has been an impact on our ability to provide care to our veterans with MS. There are challenges having them come into the office or providing virtual care. There are additional challenges and concerns this year about making changes in MS medications because we can’t see patients in person to or understand their needs or current status of their MS. So, providing care has been a challenge this year as well.

There has also been an impact on our day to day lives, like there has been for all of us, from the lockdown particularly not being able to exercise and socialize as much. There have been physical and social and emotional tolls that this disease has taken on veterans with MS.

Jodie Haselkorn, MD, MPH: The survivors of COVID-19, that are transferred to an inpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation program unit to address impairments related to the cardiopulmonary, immobility, psychological impacts and other medical complications are highly motivated to work with the team to achieve a safe discharge. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Rehabilitation Services has much to offer them.

Heidi Maloni, PhD, NP: Veterans with MS are not at greater risk because they are diagnosed with MS. But, their comorbidities such as hypertension, obesity, or factors such as older age and increased disability can increase the risk of COVID-19 infection and poorer outcomes if infected. might place them at greater risk.

Veterans have asked “Am I at greater risk? Do I need to do something more to protect myself?” I have had innumerable veterans call and ask whether I can write them letters for their employer to ensure that they work at home longer rather than go into the workplace because they’re very nervous and don’t feel confident that masking and distancing is really going to be protective.

Mitchell Wallin: We are analyzing some of our data in the VA health care system related to COVID-19 infections in the MS population. We can’t say for sure what are numbers are, but our rates of infection and hospitalization are higher than the general population and we will soon have a report. We have a majority male population, which is different from the general MS population, which is predominantly female. The proportion of minority patients in VA mirrors those of the US population. These demographic factors along with a high level of comorbid disease put veterans at high risk for acquiring COVID-19. So, in some ways it’s hard to compare when you look at reports from other countries or the US National MS-COVID-19 Registry, which captures a population that is predominantly female. In the VA, our age range spans from the 20s to almost 100 years. We must understand our population to prevent COVID-19 and better care for the most vulnerable.

Rebecca Spain: Heidi, my understanding, although the numbers are small, that for the most part, Veterans with MS who are older are at higher risk of complications and death, which is also true of the general population. But that there is an additional risk for people with MS who have higher disability levels. My understanding from reading the literature, was that people with MS needing or requiring a cane to walk or greater assistance for mobility were at a higher risk for COVID-19 complications, including mortality. I have been particularly encouraged that in many places this special population of people with MS are getting vaccinated sooner.

Heidi Maloni: I completely agree, you said it very clearly, Becca. Their disability level puts them at risk

Rebecca Spain: Disability is a comorbidity.

Heidi Maloni: Yes. Just sitting in a wheelchair and not being able to get a full breath or having problems with respiratory effort really does put you at risk for doing well if you were to have COVID-19.

Are there other ancillary impacts from COVID-19 for patients with MS?

Jodie Haselkorn: Individuals who are hospitalized with COVID-19 miss social touch and social support from family and friends. They miss familiar conversations, a hug and having someone hold their hand. The acute phase of the infection limits professional face-to-face interaction with patients due to time and protective garments. There are reports of negative consequences with isolation and social reintegration of the COVID-19 survivors is necessary and a necessary part of rehabilitation.

Mitchell Wallin: For certain procedures (eg, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) or consultations, we need to bring people into the medical center. Many clinical encounters, however, can be done through telemedicine and both the VA and the US Department of Defense systems were set up to execute this type of visit. We had been doing telemedicine for a long time before the pandemic and we were in a better position than a lot of other health systems to shift to a virtual format with COVID-19. We had to ramp up a little bit and get our tools working a little more effectively for all clinics, but I think we were prepared to broadly execute telemedicine clinics for the pandemic.

Jodie Haselkorn: I agree that the he VA infrastructure was ahead of most other health system in terms of readiness for telehealth and maintaining access to care. Not all health care providers (HCPs) were using it, but the system was there, and included a telehealth coordinator in all of the facilities who could gear health care professionals up quickly. Additionally, a system was in place to provide veterans and caregivers with telehealth home equipment and provide training. Another thing that really helped was the MISSION Act. Veterans who have difficulty travelling for an appointment may have the ability to seek care outside of the VA within their own community. They may be able to go into a local facility to get laboratory or radiologic studies done or continue rehabilitation closer to home.

VA MS Registry Data

Rebecca Spain: Mitch, there are many interesting things we can learn about the interplay between COVID-19 and MS using registries such as how it affects people based on rural vs metropolitan living, whether people are living in single family homes or not as a proxy marker for social support, and so on.

Mitchell Wallin: We have both an MS registry to track and follow patients through our clinical network and a specific COVID-19 registry as well in VA. We have identified the MS cases infected with CoVID-19 and are putting them together.

Jodie Haselkorn: There are a number of efforts in mental health that are moving forward to examine depression and in anxiety during COVID-19. Individuals with MS have increased rates of depression and anxiety above that of the general population during usual times. The literature reports an increase in anxiety and depression in general population associated with the pandemic and veterans with MS seem to be reporting these symptoms more frequently as well. We will be able to track use the registry to assess the impacts of COVID-19 on depression and anxiety in Veterans with MS.

Providing MS Care During COVID-19

Jodie Haselkorn: The transition to telehealth in COVID-19 has been surprisingly seamless with some additional training for veterans and HCPs. I initially experienced an inefficiency in my clinic visit productivity. It took me longer to see a veteran because I wasn’t doing telehealth in our clinic with support staff and residents, my examination had to change, my documentation template needed to be restructured, and the coding was different. Sometimes I saw a veteran in clinic the and my next appointment required me to move back to my office in another building for a telehealth appointment. Teaching virtual trainees who also participated in the clinic encounters had its own challenges and rewards. My ‘motor routine’ was disrupted.

Rebecca Spain: There’s a real learning curve for telehealth in terms of how comfortable you feel with the data you get by telephone or video and how reliable that is. There are issues based on technology factors—like the patient’s bandwidth—because determining how smooth their motions are is challenging if you have a jerky, intermittent signal. I learned quickly to always do the physical examination first because I might lose video connection partway through and have to switch to a phone visit!

It’s still an open question, how much are we missing by using a video and not in-person visits. And what are the long-term health outcomes and implications of that? That is something that needs to be studied in neurology where we pride ourselves on the physical examination. When move to a virtual physical examination, is there cost? There are incredible gains using telehealth in terms of convenience and access to care, which may outweigh some of the drawbacks in particular cases.

There are also pandemic challenge in terms of clinic workflow. At VA Portland Health Care System in Oregon, I have 3 clinics for Friday morning: telephone, virtual, and face-to-face clinics. It’s a real struggle for the schedulers. And because of that transition to new system workflows to accommodate this, some patient visits have been dropped, lost, or scheduled incorrectly.

Heidi Maloni: As the nurse in this group, I agree with everything that Becca and Jodie have said about telehealth. But, I have found some benefits, and one of them is a greater intimacy with my patients. What do I mean by that? For instance, if a patient has taken me to their kitchen and opened their cupboard to show me the breakfast cereal, I’m also observing that there’s nothing else in that cupboard other than cereal. I’m also putting some things together about health and wellness. Or, for the first time, I might meet their significant other who can’t come to clinic because they’re working, but they are at home with the patient. And then having that 3-way conversation with the patient and the significant other, that’s kind of opened up my sense of who that person is.

You are right about the neurological examination. It’s challenging to make exacting assessments. When gathering household objects, ice bags and pronged forks to assess sensation, you remember that this exam is subjective and there is meaning in this remote evaluation. But all in all, I have been blessed with telehealth. Patients don’t mind it at all. They’re completely open to the idea. They like the telehealth for the contact they are able to have with their HCP.

Jodie Haselkorn: As you were saying that, Heidi, I thought, I’ve been inside my veterans’ bathrooms virtually and have seen all of their equipment that they have at home. In a face-to-face clinic visit, you don’t have an opportunity to see all their canes and walkers, braces, and other assistive technology. Some of it’s stashed in a closet, some of it under the bed. In a virtual visit, I get to understand why some is not used, what veterans prefer, and see their own innovations for mobility and self-care.

Mitchell Wallin: There’s a typical ritual that patients talk about when they go to a clinic. They check in, sit down, and wait for the nurse to give them their vital signs and set them up in the room. And then they meet with their HCP, and finally they complete the tasks on the checklist. And part of that may mean scheduling an MRI or going to the lab. But some of these handoffs don’t happen as well on telehealth. Maybe we haven’t integrated these segments of a clinical visit into telehealth platforms. But it could be developed, and there could be new neurologic tools to improve the interview and physical examination. Twenty years ago, you couldn’t deposit a check on your phone; but now you can do everything on your phone you could do in a physical bank. With some creativity, we can improve parts of the neurological exam that are currently difficult to assess remotely.

Jodie Haselkorn: I have not used peripherals in video telehealth to home and I would need to become accustomed to their use with current technology and train patients and caregivers. I would like telehealth peripherals such as a stethoscope to listen to the abdomen of a veteran with neurogenic bowel or a user-friendly ultrasound probe to measure postvoid residual urine in an individual with symptoms of neurogenic bladder, in addition to devices that measure walking speed and pulmonary function. I look forward to the development, use, and the incorporation peripherals that will enable a more extensive virtual exam within the home.

What are the MS Centers of Excellence working on now?

Jodie Haselkorn: We are working to understand the healthcare needs of veterans with MS by evaluating not only care for MS within the VA, but also the types and quantity of MS specialty care VA that is being received in the community during the pandemic. Dr. Wallin is also using the registry to lead a telehealth study to capture the variety of different codes that VA health professionals in MS have used to document workload by telehealth, and face-to-face, and telephone encounters.

Rebecca Spain: The MS Center of Excellence (MSCoE) is coming out with note templates to be available for HCPs, which we can refine as we get experience. This is s one way we can promote high standards in MS care by making these ancillary tools more productive.

Jodie Haselkorn: We are looking at different ways to achieve a high-quality virtual examination using standardized examination strategies and patient and caregiver information to prepare for a specialty MS visit.

Rebecca Spain: I would like to, in more of a research setting, study health outcomes using telehealth vs in person and start tracking that long term.

Mitchell Wallin: We can probably do more in terms of standardization, such as the routine patient reported surveys and implementing the new Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers’ International MRI criteria. The COVID pandemic has affected everything in medical care. But we want to have a regular standardized outcome to assess, and if we can start to do some of the standard data collection through telemedicine, it becomes part of our regular clinic data.

Heidi Maloni: We need better technology. You can do electrocardiograms on your watch. Could we do Dinamaps? Could we figure out strength? That’s a wish list.

Jodie Haselkorn: Since the MSCoE is a national program, we were set up to do what we needed to do for education. We were able to continue on with all of our HCP webinars, including the series with the National MS Society (NMSS). We also have a Specialty Care Access Network-Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (SCAN-ECHO) series with the Northwest ECHO VA program and collaborated with the Can Do MS program on patient education as well. We’ve sent out 2 printed newsletters for veterans. The training of HCPs for the future has continued as well. All of our postdoctoral fellows who have finished their programs on time and moved on to either clinical practice or received career development grants to continue their VA careers, a new fellow has joined, and our other fellows are continuing as planned.

The loss that we sustained was in-person meetings. We held MSCoE Regional Program meetings in the East and West that combined education and administrative goals. Both of these were well attended and successful. There was a lot of virtual education available from multiple sources. It was challenging this year was to anticipate what education programming people wanted from MSCoE. Interestingly, a lot of our regional HCPs did not want much more COVID-19 education. They wanted other education and we were able to meet those needs.

Did the pandemic impact the VA MS registry?

Mitchell Wallin: Like any electronic product, the VA MS Surveillance Registry must be maintained, and we have tried to encourage people to use it. Our biggest concern was to identify cases of MS that got infected with COVID-19 and to put those people into the registry. In some cases, Veterans with MS were in locations without a MS clinic. So, we’ve spent a lot more time identifying those cases and adjudicating them to make sure their infection and MS were documented correctly.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the VA healthcare system has been taxed like others and so HCPs have been a lot busier than normal, forcing new workflows. It has been a hard year that way because a lot of health care providers have been doing many other jobs to help maintain patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Heidi Maloni: The impact of COVID-19 has been positive for the registry because we’ve had more opportunities to populate it.

Jodie Haselkorn: Dr. Wallin and the COVID-19 Registry group began building the combined registry at the onset of the pandemic. We have developed the capacity to identify COVID-19 infections in veterans who have MS and receive care in the VA. We entered these cases in the MS Surveillance Registry and have developed a linkage with the COVID-19 national VA registry. We are in the middle of the grunt work part case entry, but it is a rich resource.

How has the pandemic impacted MS research?

Rebecca Spain: COVID-19 has put a big damper on clinical research progress, including some of our MSCoE studies. It has been difficult to have subjects come in for clinical visits. It’s been difficult to get approval for new studies. It’s shifted timelines dramatically, and then that always increases budgets in a time when there’s not a lot of extra money. So, for clinical research, it’s been a real struggle and a strain and an ever-moving target. For laboratory research most, if not all, centers that have laboratory research at some point were closed and have only slowly reopened. Some still haven’t reopened to any kind of research or laboratory. So, it’s been tough, I think, on research in general.

Heidi Maloni: I would say the word is devastating. The pandemic essentially put a stop to in-person research studies. Our hospital was in research phase I, meaning human subjects can only participate in a research study if they are an inpatient or outpatient with an established clinic visit (clinics open to 25% occupancy) or involved in a study requiring safety monitoring, This plan limits risk of COVID-19 exposure.

Rebecca Spain: There is risk for a higher dropout rate of subjects from studies meaning there’s less chance of success for finding answers if enough people don’t stay in. At a certain point, you have to say, “Is this going to be a successful study?”

Jodie Haselkorn: Dr. Spain has done an amazing job leading a multisite, international clinical trial funded by the VA and the NMSS and kept it afloat, despite challenges. The pandemic has had impacts, but the study continues to move towards completion. I’ve appreciated the efforts of the Research Service at VA Puget Sound to ensure that we could safely obtain many of the 12-month outcomes for all the participants enrolled in that study.

Mitchell Wallin: The funding for some of our nonprofit partners, including the Paralyzed Veterans Association (PVA) and the NMSS, has suffered as well and so a lot of their funding programs have closed or been cut back during the pandemic. Despite that, we still have been able to use televideo technology for our clinical and educational programs with our network.

Jodie Haselkorn: MSCoE also does health services and epidemiological studies in addition to clinical trials and that work has continued. Quite a few of the studies that had human subjects in them were completed in terms of data collection, and so those are being analyzed. There will be a drop in funded studies, publications and posters as the pandemic continues and for a recovery period. We have a robust baseline for research productivity and a talented team. We’ll be able to track drop off and recovery over time.

Rebecca Spain: There’s going to be long-term consequences that we don’t see right now, especially for young researchers who have missed getting pilot data which would have led to additional small grants and then later large grants. There’s going to be an education gap that’s going on with all of the kids who are not able to go to school properly. It’s part of that whole swath of lost time and lost opportunity that we will have to deal with.

However, there are going to be some positive changes. We’re now busy designing clinical trials that can be done virtually to minimize any contact with the health facility, and then looking at things like shifting to research ideas that are more focused around health services.

Jodie Haselkorn: Given the current impacts of the pandemic on delivery of health care there is a strong interest in looking at how we can deliver health care in ways that accommodates the consumers and the providers perspectives. In the future we see marked impacts in our abilities to deliver care to Veterans with MS.

As a final thought, I wanted to put in a plug for this talented team. One of our pandemic resolutions was to innovatively find new possibilities and avoid negative focus on small changes. We are fortunate that all our staff have remained healthy and been supportive and compassionate with each other throughout this period. We have met our goals and are still moving forward.

MSCoE has benefited from the supportive leadership of Sharyl Martini, MD, PhD, and Glenn Graham, MD, PhD, in VA Specialty Care Neurology and leadership and space from VA Puget Sound, VA Portland Health Care System, the Washington DC VA Medical Center and VA Maryland Health Care System in Baltimore.

We also have a national advisory system that is actively involved, sets high standards and performs a rigorous annual review. We have rich inputs from the VA National Regional Programs and Veterans. Additionally, we have had the leadership and opportunities to collaborate with outside organizations including, the Consortium of MS Centers, the NMSS, and the PVA. We have been fortunate.

The following is a lightly edited transcript of a teleconference recorded in February 2021.

How has COVID impacted Veterans with multiple sclerosis?

Mitchell Wallin, MD, MPH: There has been a lot of concern in the multiple sclerosis (MS) patient community about getting infected with COVID-19 and what to do about it. Now that there are vaccines, the concern is whether and how to take a vaccine. At least here, in the Washington DC/Baltimore area where I practice, we have seen many veterans being hospitalized with COVID-19, some with multiple sclerosis (MS), and some who have died of COVID-19. So, there has been a lot of fear, especially in veterans that are older with comorbid diseases.

Rebecca Spain, MD, MSPH: There also has been an impact on our ability to provide care to our veterans with MS. There are challenges having them come into the office or providing virtual care. There are additional challenges and concerns this year about making changes in MS medications because we can’t see patients in person to or understand their needs or current status of their MS. So, providing care has been a challenge this year as well.

There has also been an impact on our day to day lives, like there has been for all of us, from the lockdown particularly not being able to exercise and socialize as much. There have been physical and social and emotional tolls that this disease has taken on veterans with MS.

Jodie Haselkorn, MD, MPH: The survivors of COVID-19, that are transferred to an inpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation program unit to address impairments related to the cardiopulmonary, immobility, psychological impacts and other medical complications are highly motivated to work with the team to achieve a safe discharge. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Rehabilitation Services has much to offer them.

Heidi Maloni, PhD, NP: Veterans with MS are not at greater risk because they are diagnosed with MS. But, their comorbidities such as hypertension, obesity, or factors such as older age and increased disability can increase the risk of COVID-19 infection and poorer outcomes if infected. might place them at greater risk.

Veterans have asked “Am I at greater risk? Do I need to do something more to protect myself?” I have had innumerable veterans call and ask whether I can write them letters for their employer to ensure that they work at home longer rather than go into the workplace because they’re very nervous and don’t feel confident that masking and distancing is really going to be protective.

Mitchell Wallin: We are analyzing some of our data in the VA health care system related to COVID-19 infections in the MS population. We can’t say for sure what are numbers are, but our rates of infection and hospitalization are higher than the general population and we will soon have a report. We have a majority male population, which is different from the general MS population, which is predominantly female. The proportion of minority patients in VA mirrors those of the US population. These demographic factors along with a high level of comorbid disease put veterans at high risk for acquiring COVID-19. So, in some ways it’s hard to compare when you look at reports from other countries or the US National MS-COVID-19 Registry, which captures a population that is predominantly female. In the VA, our age range spans from the 20s to almost 100 years. We must understand our population to prevent COVID-19 and better care for the most vulnerable.

Rebecca Spain: Heidi, my understanding, although the numbers are small, that for the most part, Veterans with MS who are older are at higher risk of complications and death, which is also true of the general population. But that there is an additional risk for people with MS who have higher disability levels. My understanding from reading the literature, was that people with MS needing or requiring a cane to walk or greater assistance for mobility were at a higher risk for COVID-19 complications, including mortality. I have been particularly encouraged that in many places this special population of people with MS are getting vaccinated sooner.

Heidi Maloni: I completely agree, you said it very clearly, Becca. Their disability level puts them at risk

Rebecca Spain: Disability is a comorbidity.

Heidi Maloni: Yes. Just sitting in a wheelchair and not being able to get a full breath or having problems with respiratory effort really does put you at risk for doing well if you were to have COVID-19.

Are there other ancillary impacts from COVID-19 for patients with MS?

Jodie Haselkorn: Individuals who are hospitalized with COVID-19 miss social touch and social support from family and friends. They miss familiar conversations, a hug and having someone hold their hand. The acute phase of the infection limits professional face-to-face interaction with patients due to time and protective garments. There are reports of negative consequences with isolation and social reintegration of the COVID-19 survivors is necessary and a necessary part of rehabilitation.

Mitchell Wallin: For certain procedures (eg, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) or consultations, we need to bring people into the medical center. Many clinical encounters, however, can be done through telemedicine and both the VA and the US Department of Defense systems were set up to execute this type of visit. We had been doing telemedicine for a long time before the pandemic and we were in a better position than a lot of other health systems to shift to a virtual format with COVID-19. We had to ramp up a little bit and get our tools working a little more effectively for all clinics, but I think we were prepared to broadly execute telemedicine clinics for the pandemic.

Jodie Haselkorn: I agree that the he VA infrastructure was ahead of most other health system in terms of readiness for telehealth and maintaining access to care. Not all health care providers (HCPs) were using it, but the system was there, and included a telehealth coordinator in all of the facilities who could gear health care professionals up quickly. Additionally, a system was in place to provide veterans and caregivers with telehealth home equipment and provide training. Another thing that really helped was the MISSION Act. Veterans who have difficulty travelling for an appointment may have the ability to seek care outside of the VA within their own community. They may be able to go into a local facility to get laboratory or radiologic studies done or continue rehabilitation closer to home.

VA MS Registry Data

Rebecca Spain: Mitch, there are many interesting things we can learn about the interplay between COVID-19 and MS using registries such as how it affects people based on rural vs metropolitan living, whether people are living in single family homes or not as a proxy marker for social support, and so on.

Mitchell Wallin: We have both an MS registry to track and follow patients through our clinical network and a specific COVID-19 registry as well in VA. We have identified the MS cases infected with CoVID-19 and are putting them together.

Jodie Haselkorn: There are a number of efforts in mental health that are moving forward to examine depression and in anxiety during COVID-19. Individuals with MS have increased rates of depression and anxiety above that of the general population during usual times. The literature reports an increase in anxiety and depression in general population associated with the pandemic and veterans with MS seem to be reporting these symptoms more frequently as well. We will be able to track use the registry to assess the impacts of COVID-19 on depression and anxiety in Veterans with MS.

Providing MS Care During COVID-19

Jodie Haselkorn: The transition to telehealth in COVID-19 has been surprisingly seamless with some additional training for veterans and HCPs. I initially experienced an inefficiency in my clinic visit productivity. It took me longer to see a veteran because I wasn’t doing telehealth in our clinic with support staff and residents, my examination had to change, my documentation template needed to be restructured, and the coding was different. Sometimes I saw a veteran in clinic the and my next appointment required me to move back to my office in another building for a telehealth appointment. Teaching virtual trainees who also participated in the clinic encounters had its own challenges and rewards. My ‘motor routine’ was disrupted.

Rebecca Spain: There’s a real learning curve for telehealth in terms of how comfortable you feel with the data you get by telephone or video and how reliable that is. There are issues based on technology factors—like the patient’s bandwidth—because determining how smooth their motions are is challenging if you have a jerky, intermittent signal. I learned quickly to always do the physical examination first because I might lose video connection partway through and have to switch to a phone visit!

It’s still an open question, how much are we missing by using a video and not in-person visits. And what are the long-term health outcomes and implications of that? That is something that needs to be studied in neurology where we pride ourselves on the physical examination. When move to a virtual physical examination, is there cost? There are incredible gains using telehealth in terms of convenience and access to care, which may outweigh some of the drawbacks in particular cases.

There are also pandemic challenge in terms of clinic workflow. At VA Portland Health Care System in Oregon, I have 3 clinics for Friday morning: telephone, virtual, and face-to-face clinics. It’s a real struggle for the schedulers. And because of that transition to new system workflows to accommodate this, some patient visits have been dropped, lost, or scheduled incorrectly.

Heidi Maloni: As the nurse in this group, I agree with everything that Becca and Jodie have said about telehealth. But, I have found some benefits, and one of them is a greater intimacy with my patients. What do I mean by that? For instance, if a patient has taken me to their kitchen and opened their cupboard to show me the breakfast cereal, I’m also observing that there’s nothing else in that cupboard other than cereal. I’m also putting some things together about health and wellness. Or, for the first time, I might meet their significant other who can’t come to clinic because they’re working, but they are at home with the patient. And then having that 3-way conversation with the patient and the significant other, that’s kind of opened up my sense of who that person is.

You are right about the neurological examination. It’s challenging to make exacting assessments. When gathering household objects, ice bags and pronged forks to assess sensation, you remember that this exam is subjective and there is meaning in this remote evaluation. But all in all, I have been blessed with telehealth. Patients don’t mind it at all. They’re completely open to the idea. They like the telehealth for the contact they are able to have with their HCP.

Jodie Haselkorn: As you were saying that, Heidi, I thought, I’ve been inside my veterans’ bathrooms virtually and have seen all of their equipment that they have at home. In a face-to-face clinic visit, you don’t have an opportunity to see all their canes and walkers, braces, and other assistive technology. Some of it’s stashed in a closet, some of it under the bed. In a virtual visit, I get to understand why some is not used, what veterans prefer, and see their own innovations for mobility and self-care.

Mitchell Wallin: There’s a typical ritual that patients talk about when they go to a clinic. They check in, sit down, and wait for the nurse to give them their vital signs and set them up in the room. And then they meet with their HCP, and finally they complete the tasks on the checklist. And part of that may mean scheduling an MRI or going to the lab. But some of these handoffs don’t happen as well on telehealth. Maybe we haven’t integrated these segments of a clinical visit into telehealth platforms. But it could be developed, and there could be new neurologic tools to improve the interview and physical examination. Twenty years ago, you couldn’t deposit a check on your phone; but now you can do everything on your phone you could do in a physical bank. With some creativity, we can improve parts of the neurological exam that are currently difficult to assess remotely.

Jodie Haselkorn: I have not used peripherals in video telehealth to home and I would need to become accustomed to their use with current technology and train patients and caregivers. I would like telehealth peripherals such as a stethoscope to listen to the abdomen of a veteran with neurogenic bowel or a user-friendly ultrasound probe to measure postvoid residual urine in an individual with symptoms of neurogenic bladder, in addition to devices that measure walking speed and pulmonary function. I look forward to the development, use, and the incorporation peripherals that will enable a more extensive virtual exam within the home.

What are the MS Centers of Excellence working on now?

Jodie Haselkorn: We are working to understand the healthcare needs of veterans with MS by evaluating not only care for MS within the VA, but also the types and quantity of MS specialty care VA that is being received in the community during the pandemic. Dr. Wallin is also using the registry to lead a telehealth study to capture the variety of different codes that VA health professionals in MS have used to document workload by telehealth, and face-to-face, and telephone encounters.

Rebecca Spain: The MS Center of Excellence (MSCoE) is coming out with note templates to be available for HCPs, which we can refine as we get experience. This is s one way we can promote high standards in MS care by making these ancillary tools more productive.

Jodie Haselkorn: We are looking at different ways to achieve a high-quality virtual examination using standardized examination strategies and patient and caregiver information to prepare for a specialty MS visit.

Rebecca Spain: I would like to, in more of a research setting, study health outcomes using telehealth vs in person and start tracking that long term.

Mitchell Wallin: We can probably do more in terms of standardization, such as the routine patient reported surveys and implementing the new Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers’ International MRI criteria. The COVID pandemic has affected everything in medical care. But we want to have a regular standardized outcome to assess, and if we can start to do some of the standard data collection through telemedicine, it becomes part of our regular clinic data.

Heidi Maloni: We need better technology. You can do electrocardiograms on your watch. Could we do Dinamaps? Could we figure out strength? That’s a wish list.

Jodie Haselkorn: Since the MSCoE is a national program, we were set up to do what we needed to do for education. We were able to continue on with all of our HCP webinars, including the series with the National MS Society (NMSS). We also have a Specialty Care Access Network-Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (SCAN-ECHO) series with the Northwest ECHO VA program and collaborated with the Can Do MS program on patient education as well. We’ve sent out 2 printed newsletters for veterans. The training of HCPs for the future has continued as well. All of our postdoctoral fellows who have finished their programs on time and moved on to either clinical practice or received career development grants to continue their VA careers, a new fellow has joined, and our other fellows are continuing as planned.

The loss that we sustained was in-person meetings. We held MSCoE Regional Program meetings in the East and West that combined education and administrative goals. Both of these were well attended and successful. There was a lot of virtual education available from multiple sources. It was challenging this year was to anticipate what education programming people wanted from MSCoE. Interestingly, a lot of our regional HCPs did not want much more COVID-19 education. They wanted other education and we were able to meet those needs.

Did the pandemic impact the VA MS registry?

Mitchell Wallin: Like any electronic product, the VA MS Surveillance Registry must be maintained, and we have tried to encourage people to use it. Our biggest concern was to identify cases of MS that got infected with COVID-19 and to put those people into the registry. In some cases, Veterans with MS were in locations without a MS clinic. So, we’ve spent a lot more time identifying those cases and adjudicating them to make sure their infection and MS were documented correctly.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the VA healthcare system has been taxed like others and so HCPs have been a lot busier than normal, forcing new workflows. It has been a hard year that way because a lot of health care providers have been doing many other jobs to help maintain patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Heidi Maloni: The impact of COVID-19 has been positive for the registry because we’ve had more opportunities to populate it.

Jodie Haselkorn: Dr. Wallin and the COVID-19 Registry group began building the combined registry at the onset of the pandemic. We have developed the capacity to identify COVID-19 infections in veterans who have MS and receive care in the VA. We entered these cases in the MS Surveillance Registry and have developed a linkage with the COVID-19 national VA registry. We are in the middle of the grunt work part case entry, but it is a rich resource.

How has the pandemic impacted MS research?

Rebecca Spain: COVID-19 has put a big damper on clinical research progress, including some of our MSCoE studies. It has been difficult to have subjects come in for clinical visits. It’s been difficult to get approval for new studies. It’s shifted timelines dramatically, and then that always increases budgets in a time when there’s not a lot of extra money. So, for clinical research, it’s been a real struggle and a strain and an ever-moving target. For laboratory research most, if not all, centers that have laboratory research at some point were closed and have only slowly reopened. Some still haven’t reopened to any kind of research or laboratory. So, it’s been tough, I think, on research in general.

Heidi Maloni: I would say the word is devastating. The pandemic essentially put a stop to in-person research studies. Our hospital was in research phase I, meaning human subjects can only participate in a research study if they are an inpatient or outpatient with an established clinic visit (clinics open to 25% occupancy) or involved in a study requiring safety monitoring, This plan limits risk of COVID-19 exposure.

Rebecca Spain: There is risk for a higher dropout rate of subjects from studies meaning there’s less chance of success for finding answers if enough people don’t stay in. At a certain point, you have to say, “Is this going to be a successful study?”

Jodie Haselkorn: Dr. Spain has done an amazing job leading a multisite, international clinical trial funded by the VA and the NMSS and kept it afloat, despite challenges. The pandemic has had impacts, but the study continues to move towards completion. I’ve appreciated the efforts of the Research Service at VA Puget Sound to ensure that we could safely obtain many of the 12-month outcomes for all the participants enrolled in that study.

Mitchell Wallin: The funding for some of our nonprofit partners, including the Paralyzed Veterans Association (PVA) and the NMSS, has suffered as well and so a lot of their funding programs have closed or been cut back during the pandemic. Despite that, we still have been able to use televideo technology for our clinical and educational programs with our network.

Jodie Haselkorn: MSCoE also does health services and epidemiological studies in addition to clinical trials and that work has continued. Quite a few of the studies that had human subjects in them were completed in terms of data collection, and so those are being analyzed. There will be a drop in funded studies, publications and posters as the pandemic continues and for a recovery period. We have a robust baseline for research productivity and a talented team. We’ll be able to track drop off and recovery over time.

Rebecca Spain: There’s going to be long-term consequences that we don’t see right now, especially for young researchers who have missed getting pilot data which would have led to additional small grants and then later large grants. There’s going to be an education gap that’s going on with all of the kids who are not able to go to school properly. It’s part of that whole swath of lost time and lost opportunity that we will have to deal with.

However, there are going to be some positive changes. We’re now busy designing clinical trials that can be done virtually to minimize any contact with the health facility, and then looking at things like shifting to research ideas that are more focused around health services.

Jodie Haselkorn: Given the current impacts of the pandemic on delivery of health care there is a strong interest in looking at how we can deliver health care in ways that accommodates the consumers and the providers perspectives. In the future we see marked impacts in our abilities to deliver care to Veterans with MS.

As a final thought, I wanted to put in a plug for this talented team. One of our pandemic resolutions was to innovatively find new possibilities and avoid negative focus on small changes. We are fortunate that all our staff have remained healthy and been supportive and compassionate with each other throughout this period. We have met our goals and are still moving forward.

MSCoE has benefited from the supportive leadership of Sharyl Martini, MD, PhD, and Glenn Graham, MD, PhD, in VA Specialty Care Neurology and leadership and space from VA Puget Sound, VA Portland Health Care System, the Washington DC VA Medical Center and VA Maryland Health Care System in Baltimore.

We also have a national advisory system that is actively involved, sets high standards and performs a rigorous annual review. We have rich inputs from the VA National Regional Programs and Veterans. Additionally, we have had the leadership and opportunities to collaborate with outside organizations including, the Consortium of MS Centers, the NMSS, and the PVA. We have been fortunate.

The Multiple Sclerosis Centers of Excellence: A Model of Excellence in the VA (FULL)

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has established a number of centers of excellence (CoEs), including centers focused on posttraumatic stress disorder, suicide prevention, epilepsy, and, most recently, the Senator Elizabeth Dole CoE for Veteran and Caregiver Research. Some VA CoE serve as centralized locations for specialty care. For example, the VA Epilepsy CoE is a network of 16 facilities that provide comprehensive epilepsy care for veterans with seizure disorders, including expert and presurgical evaluations and inpatient monitoring.

In contrast, other CoEs, including the multiple sclerosis (MS) CoE, achieve their missions by serving as a resource center to a network of regional and supporting various programs to optimize the care of veterans across the nation within their home US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center (VAMC). The MSCoE are charged, through VHA Directive 1011.06, with establishing at least 1 VA MS Regional Program in each of the 21 Veteran Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) across the country and integrating these and affiliated MS Support Programs into the MS National Network. Currently, there are 29 MS regional programs and 49 MS support programs across the US.1

Established in 2003, the MSCoE is dedicated to furthering the understanding of MS, its impact on veterans, and effective treatments to help manage the disease and its symptoms. In 2002, 2 coordinating centers were selected based on a competitive review process. The MSCoE-East is located at the Baltimore, Maryland and Washington, DC VAMC and serves VISNs 1 to 10. The MSCoE-West serves VISNs 11 to 23 and is jointly-based at VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle, Washington and VA Portland Health Care System in Portland, Oregon. The MSCoEs were made permanent by The Veteran’ Benefits, Healthcare and Information Technology Act of 2006 (38 USC §7330). By partnering with veterans, caregivers, health care professionals, and other affiliates, the MSCoE endeavor to optimize health, activities, participation and quality of life for veterans with MS.

Core Functions

The MSCoE has a 3-part mission. First, the MSCoE seeks to expand care coordination between VAMCs by developing a national network of VA MSCoE Regional and Support Programs. Second, the MSCoE provides resources to VA health care providers (HCPs) through a collaborative approach to clinical care, education, research, and informatics. Third, the MSCoE improves the quality and consistency of health care services delivered to veterans diagnosed with MS nationwide. To meet its objectives, the MSCoE activities are organized around 4 functional cores: clinical care, research, education and training, and informatics and telemedicine.

Clinical Care

The MSCoE delivers high-quality clinical care by identifying veterans with MS who use VA services, understanding their needs, and facilitating appropriate interventions. Veterans with MS are a special cohort for many reasons including that about 70% are male. Men and women veterans not only have different genetics, but also may have different environmental exposures and other risk factors for MS. Since 1998, the VHA has evaluated > 50,000 veterans with MS. Over the past decade, between 18,000 and 20,000 veterans with MS have accessed care within the VHA annually.

The MSCoE advocates for appropriate and safe use of currently available MS disease modifying therapies through collaborations with the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Service (PBM). The MSCoE partners with PBM to develop and disseminate Criteria For Use, safety, and economic monitoring of the impacts of the MS therapies. The MSCoE also provide national consultation services for complex MS cases, clinical education to VA HCPs, and mentors fellows, residents, and medical students.

The VA provides numerous resources that are not readily available in other health care systems and facilitate the care for patients with chronic diseases, including providing low or no co-pays to patients for MS disease modifying agents and other MS related medications, access to medically necessary adaptive equipment at no charge, the Home Improvement and Structural Alteration (HISA) grant for assistance with safe home ingress and egress, respite care, access to a homemaker/home health aide, and caregiver support programs. Eligible veterans also can access additional resources such as adaptive housing and an automobile grant. The VA also provides substantial hands-on assistance to veterans who are homeless. The clinical team and a veteran with MS can leverage VA resources through the National MS Society (NMSS) Navigator Program as well as other community resources.2

The VHA encourages physical activity and wellness through sports and leisure. Veterans with MS can participate in sports programs and special events, including the National Veterans Wheelchair Games, the National Disabled Veterans Winter Sports Clinic, the National Disabled Veterans TEE (Training, Exposure and Experience) golf tournament, the National Veterans Summer Sports Clinic, the National Veterans Golden Age Games, and the National Veterans Creative Sports Festival. HCPs or veterans who are not sure how to access any of these programs can contact the MSCoE or their local VA social workers.

Research

The primary goal of the MSCoE research core is to conduct clinical, health services, epidemiologic, and basic science research relevant to veterans with MS. The MSCoE serves to enhance collaboration among VAMCs, increase the participation of veterans in research, and provide research mentorship for the next generation of VA MS scientists. MSCoE research is carried out by investigators at the MSCoE and the MS Regional Programs, often in collaboration with investigators at academic institutions. This research is supported by competitive grant awards from a variety of funding agencies including the VA Research and Development Service (R&D) and the NMSS. Results from about 40 research grants in Fiscal Year 2019 were disseminated through 34 peer-reviewed publications, 30 posters, presentations, abstracts, and clinical practice guidelines.

There are many examples of recent high impact MS research performed by MSCoE investigators. For example, MSCoE researchers noted an increase in the estimated prevalence of MS to 1 million individuals in the US, about twice the previously estimated prevalence.3-5 In addition, a multicenter study highlighted the prevalence of MS misdiagnosis and common confounders for MS.6 Other research includes pilot clinical trials evaluating lipoic acid as a potential disease modifying therapy in people with secondary progressive MS and the impact of a multicomponent walking aid selection, fitting, and training program for preventing falls in people with MS.7,8 Clinical trial also are investigating telehealth counseling to improve physical activity in MS and a systematic review of rehabilitation interventions in MS.9,10

Education and Training

A unified program of education is essential to effective management of MS nationally. The primary goal of the education and training core is to provide a national program of MS education for HCPs, veterans, and caregivers to improve knowledge, enhance access to resources, and promote effective management strategies. The MSCoE collaborate with the Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA), the Consortium of MS Centers (CMSC), the NMSS, and other national service organizations to increase educational opportunities, share knowledge, and expand participation.

The MSCoE education and training core produces a range of products both veterans, HCPs, and others affected by MS. The MSCoE sends a biannual patient newsletter to > 20,000 veterans and a monthly email to > 1,000 VA HCPs. Specific opportunities for HCP education include accredited multidisciplinary MS webinars, sponsored symposia and workshops at the CMSC and PVA Summit annual meetings, and presentations at other university and professional conferences. Enduring educational opportunities for veterans, caregivers, and HCPs can also be found by visiting www.va.gov/ms.

The MSCoE coordinate postdoctoral fellowship training programs to develop expertise in MS health care for the future. It offers VA physician fellowships for neurologists in Baltimore and Portland and for physiatrists in Seattle as well as NMSS fellowships for education and research. In 2019, MSCoE had 6 MD Fellows and 1 PhD Fellow.

Clinical Informatics and Telehealth

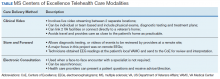

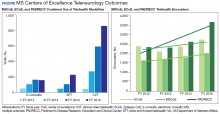

The primary goal of the informatics and telemedicine core is to employ state-of-the-art informatics, telemedicine technology, and the MSCoE website, to improve MS health care delivery. The VA has a integrated electronic health record and various data repositories are stored in the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). MSCoE utilizes the CDW to maintain a national MS administrative data repository to understand the VHA care provided to veterans with MS. Data from the CDW have also served as an important resource to facilitate a wide range of veteran-focused MS research. This research has addressed clinical conditions like pain and obesity; health behaviors like smoking, alcohol use, and exercise as well as issues related to care delivery such as specialty care access, medication adherence, and appointment attendance.11-19

Monitoring the health of veterans with MS in the VA requires additional data not available in the CDW. To this end, we have developed the MS Surveillance Registry (MSSR), funded and maintained by the VA Office of Information Technology as part of their Veteran Integrated Registry Platform (VIRP). The purpose of the MSSR is to understand the unique characteristics and treatment patterns of veterans with MS in order to optimize their VHA care. HCPs input MS-specific clinical data on their patients into the MSSR, either through the MS Assessment Tool (MSAT) in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) or through a secure online portal. Other data from existing databases from the CDW is also automatically fed into the MSSR. The MSSR continues to be developed and populated to serve as a resource for the future.