User login

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) is a rare debilitating disorder characterized by dermal plaques, joint contractures, and fibrosis of the skin with possible involvement of muscles and internal organs.1-3 Originally identified in 1997 as nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy to describe its characteristic cutaneous thickening and hardening, the name was changed to NSF to more accurately reflect the noncutaneous manifestations present in other organ tissues.2,4,5 Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis occurs in patients with a history of renal insufficiency and exposure to gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) used in magnetic resonance angiography and magnetic resonance imaging. There is no predilection for age, sex, or ethnicity.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis may develop over a period of days to several weeks. However, there have been cases of NSF developing 10 years after gadolinium exposure.2 In most cases, patients have a history of severe chronic renal disease requiring hemodialysis. There have been a few reported cases of NSF occurring in patients with resolved acute kidney injury or resolved acute on chronic renal disease.1,6-10 We present a case of NSF occurring in a patient with resolved transient renal insufficiency and no history of chronic renal disease.

Case Report

A 68-year-old woman presented with new dark, painless, pink plaques on the right thigh and calf. The patient stated the condition started and got worse after she was hospitalized 12 years prior for lower extremity cellulitis, sepsis, and acute renal failure. The patient developed complications during that hospital stay and underwent a renal biopsy and renal artery embolization requiring use of a GBCA. After the procedure, she noticed skin hardening in the extremities and decreased mobility in both legs while she was still in the hospital. It was thought that the lower leg changes were due to cellulitis. Therefore, when the renal issues resolved, she was discharged. Her skin and joint changes remained stable until 6 years later when she noticed new pink plaques appearing. Her medical history was positive for breast cancer, which was surgically and medically treated 16 years prior to presentation.

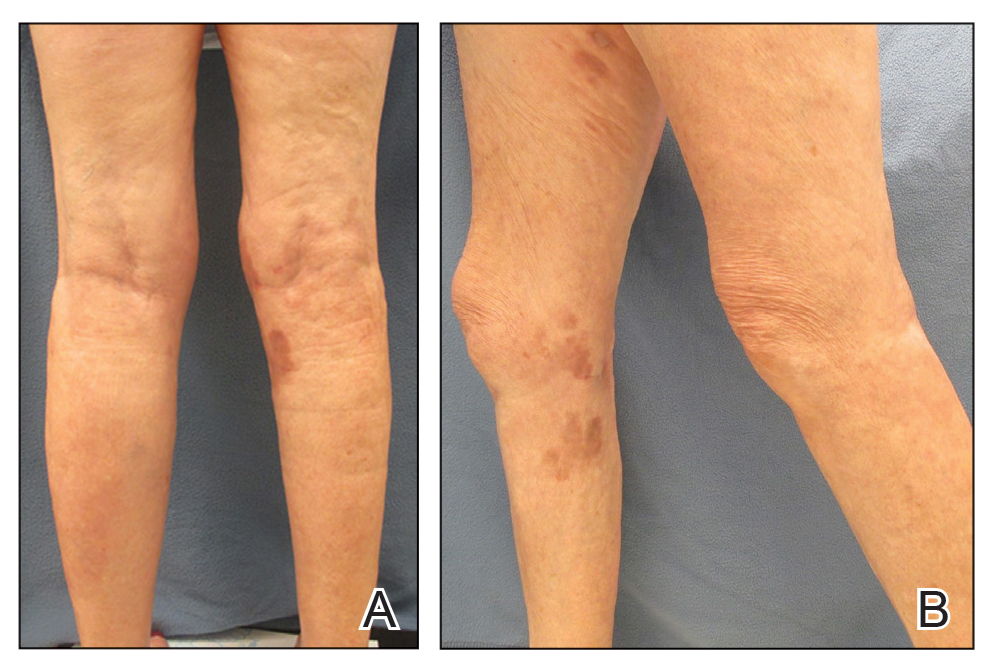

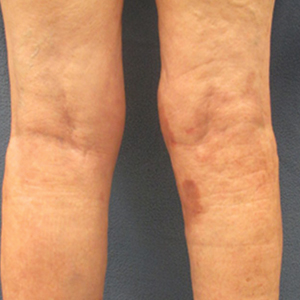

On presentation, physical examination revealed dark pink, hyperpigmented plaques on the right leg and a firm hypopigmented broad linear plaque on the right forearm. Palpation of the legs revealed thickened sclerotic plaques from the thighs down to the ankles (Figure 1). The plaques were not tender to palpation. She did have a decreased range of motion with eversion and inversion of the feet and ankles.

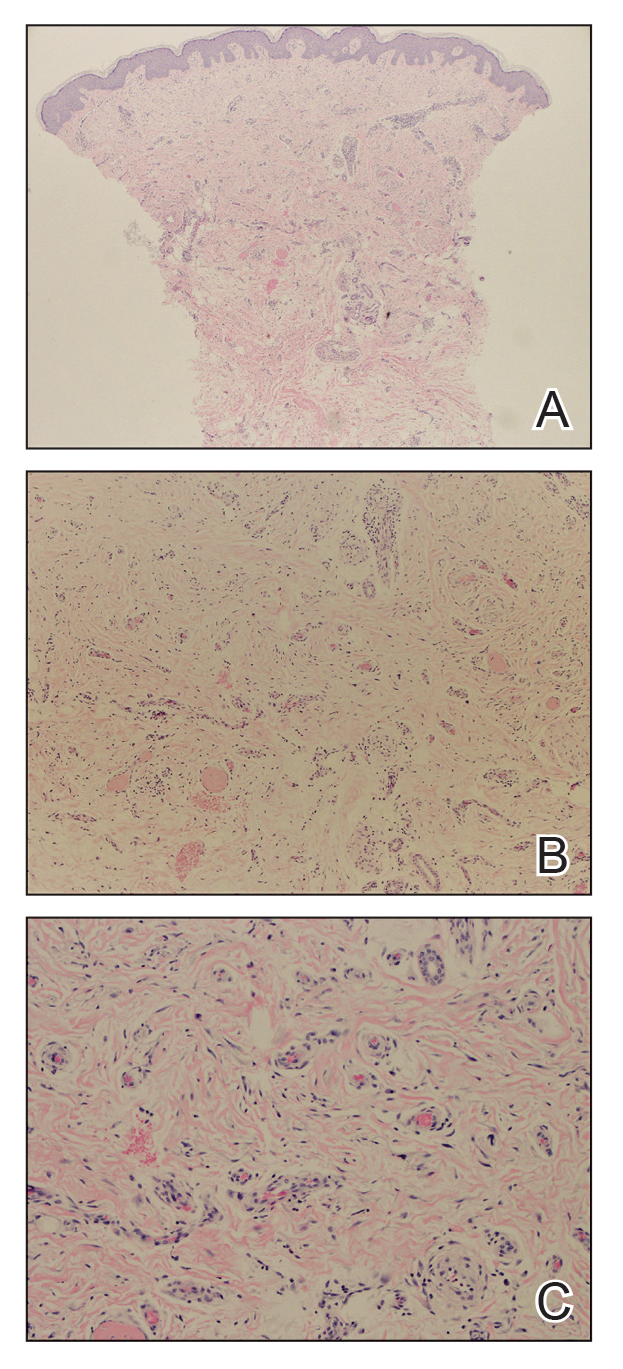

Biopsies from the right medial leg and right volar forearm showed increased bland dermal spindle cellularity associated with numerous round to ovoid osteoid aggregates encircling elastic fibers and surrounded by osteoblasts (Figure 2). CD34 immunohistochemistry showed general retention of staining within the dermal fibroblast population, and elastin stain showed general retention of elastic fiber bundles and thickening.

Laboratory workup included a complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid-stimulating hormone level, and serum protein electrophoresis; results were all within reference range. The patient also had a urine element profile from an outside provider 1 month after presenting to our office that showed an elevated urine gadolinium level of 4.146 μg/g (reference range, 0–0.019 μg/g). The patient’s skin lesions have remained stable, and she is now working with physical therapy to help with her range of motion.

Comment

Gadolinium Causing Fibrosis—The incidence of NSF varies according to the severity of renal impairment, dosage level of GBCA used, and the history of GBCA use. In patients with normal renal function, gadolinium is excreted within 90 minutes. In patients with severe renal disease, the half-life can increase to up to 34.3 hours.11 Reduced renal clearance and increased half-life of gadolinium lead to prolonged excretion, causing the GBCA to become unstable and dissociate into its constituents, leading to tissue deposition of Gd3+ cations. This dissociation is thought to be due to differences in the stability of the various chelation complexes among the different formulations of GBCAs.12 The mechanism by which the dissociated gadolinium causes the fibrosis in the skin or other organs of the body is still unknown. Furthermore, even patients with normal renal function who undergo repeated administration of GBCA have been found to have higher levels of Gd3+ in their tissues, even in the absence of symptoms.13

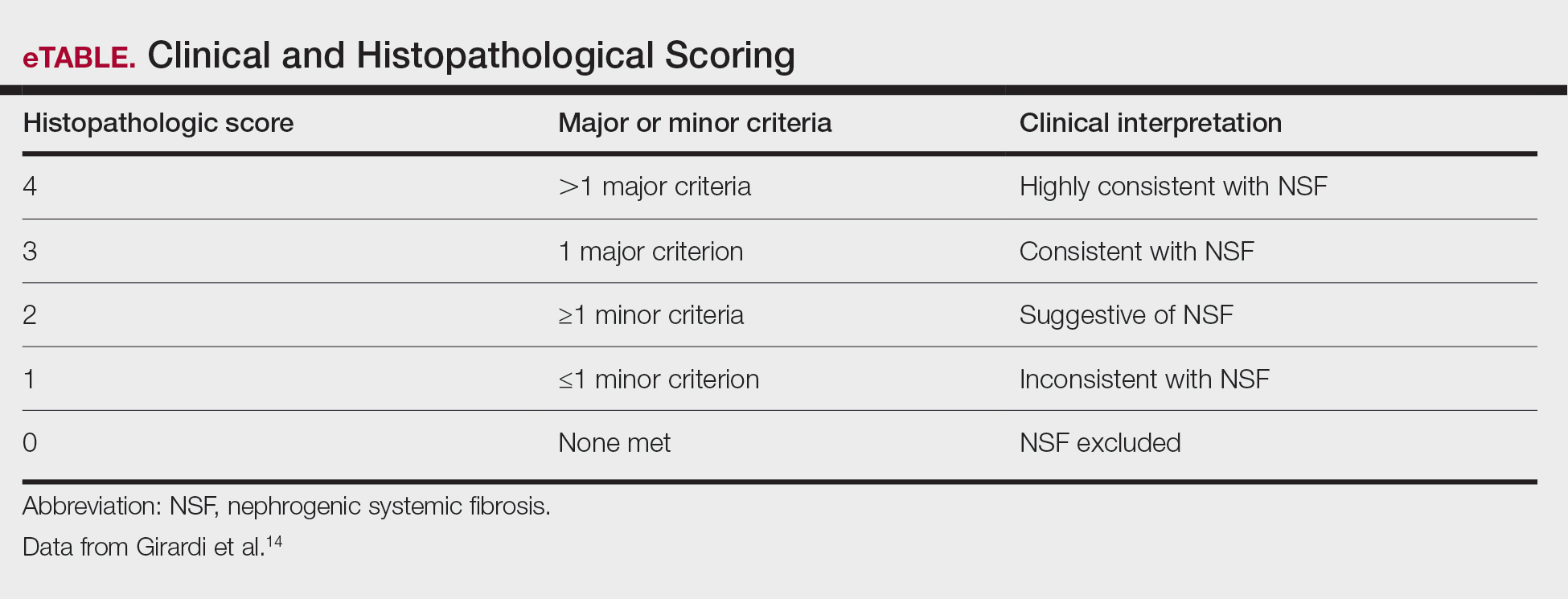

Diagnosing NSF—In 2011, Girardi et al14 created a clinical and histopathological scoring system to help diagnose NSF. Clinical findings can be broken down into major criteria and minor criteria. Major criteria consist of patterned plaques, joint contractures, cobblestoning, marked induration, or peau d’orange change. Minor criteria consist of puckering, linear banding, superficial plaques or patches, dermal papules, and scleral plaques. Histopathologic findings include increased dermal cellularity (score +1), CD34+ cells with tram tracking (score +1), thickened or thin collagen bundles (score +1), preserved elastic fibers (score −1), septal involvement (score +1), and osseous metaplasia (score +3)(eTable).14

Differential Diagnosis—The differential diagnosis of NSF includes scleromyxedema, scleroderma, eosinophilic fasciitis, eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome, lipodermatosclerosis, morphea, and chronic graft-vs-host disease. Histopathologic examination of scleromyxedema can look identical to NSF. Therefore, a review of the patient’s medical history, prior hospitalizations, and prior gadolinium exposure is important. Appropriate laboratory workups should be ordered to rule out the other differential diagnoses.

NSF and Kidney Injury—A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms NSF with kidney injury revealed 7 cases of NSF occurring in patients who either had resolved acute kidney injury or resolved acute on chronic kidney disease.1,6-10 Of those cases, 3 reported NSF occurring in patients with completely resolved acute kidney injury.6,7,10 One of those cases involved a 65-year-old man who developed acute renal failure due to acute tubular necrosis.7 He had no history of renal disease prior to hospitalization. His skin lesions continued to improve as his renal function normalized back to baseline after discharge.7 The second case involved a 42-year-old man who had repeated exposure to GBCAs during a brief period of acute kidney injury.6 Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis developed after his renal function normalized. The authors did not mention if there was clinical improvement.6 The third case involved a 22-year-old man who developed acute renal failure after ingestion of hair dye. He did not have a history of chronic renal disease, and as he recovered from the acute kidney injury, almost all of the skin lesions cleared after 1 year.10

Our patient did not have a history of chronic renal disease when she presented to the hospital for sepsis and acute tubular necrosis. Unlike 2 of the prior cases, she did not notice improvement of the skin lesions as the renal function returned to baseline. She continued to experience changes in the skin, even up to 5 years after, and then stabilized. Throughout that time, her renal function was normal. Interestingly, despite having a normal creatinine level, the patient had an elevated gadolinium level on the urine gadolinium test, which typically is not a standard test for NSF. However, the elevated value does shed light on the persistence of gadolinium in the patient despite her exposure having been more than 10 years earlier.

Treatment of NSF—There is no gold standard treatment of NSF, and reversing the fibrosis has proven to be difficult. Avoidance of GBCAs in acute kidney injury or chronic severe renal disease, as recommended by the US Food and Drug Administration, is key to preventing this debilitating disease.15 Restoration of renal function is essential for excreting the gadolinium and improvement in NSF.12 Physical and occupational therapy can improve joint mobility. Therapies such as extracorporeal photopheresis, sodium thiosulfate, pentoxifylline, glucocorticoids, plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclophosphamide, imatinib mesylate, intralesional interferon alfa, topical calcipotriene, corticosteroids, and UVA1 light therapy have been used with varying results.12 It has been suggested that renal transplantation can stop the progression of NSF. However, in the cases we reviewed, renal transplantation would not have benefited those patients because their renal function normalized.6,7,10 Additionally, even though our patient’s renal function normalized after discharge from the hospital, she continued to see more skin lesions developing, likely due to the accumulated gadolinium that was already in her tissue. The possibility of chelation therapy to remove the gadolinium has been proposed. In 1 case study involving deferoxamine injected intramuscularly in a patient with NSF, the urine excretion of gadolinium increased almost 2-fold, but there was no change in the serum concentration level of gadolinium or improvement in the patient’s clinical symptoms.16 We anticipate that our patient’s symptoms will slowly improve, as her body is still excreting the gadolinium. Our patient also was added to the International NSF Registry that was created by Dr. Shawn E. Cowper at the Yale School of Medicine (New Haven, Connecticut).

Conclusion

We report a rare case of NSF occurring in a patient with resolved acute kidney injury and no history of chronic renal disease. Our patient initially did not improve after her renal function normalized, as she continued to develop lesions 10 years after the exposure. Her elevated urine gadolinium excretion level also sheds light on the persistence of gadolinium in her body despite her normal renal function 10 years after her exposure. Although her clinical symptoms have stabilized, our case reiterates the complex pathology of this entity and challenge regarding treatment options. Physicians should be aware that NSF can still occur in healthy patients with no chronic renal disease who have had an episode of acute renal insufficiency along with exposure to a GBCA.

- Cowper SE, Su LD, Bhawan J, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:383-393.

- Grobner T. Gadolinium—a specific trigger for the development of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1104-1108.

- Larson KN, Gagnon AL, Darling MD, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis manifesting a decade after exposure to gadolinium. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1117-1120.

- Mendoza FA, Artlett CM, Sandorfi N, et al. Description of 12 cases of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:238-249.

- Ting WW, Stone MS, Madison KC, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy with systemic involvement. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:903-906.

- Lu CF, Hsiao CH, Tjiu JW. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis developed after recovery from acute renal failure: gadolinium as a possible aetiological factor. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:339-340.

- Cassis TB, Jackson JM, Sonnier GB, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy in a patient with acute renal failure never requiring dialysis. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:56-59.

- Swartz RD, Crofford LJ, Phan SH, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: a novel cutaneous fibrosing disorder in patients with renal failure. Am J Med. 2003;114:563-572.

- Mackay-Wiggan JM, Cohen DJ, Hardy MA, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (scleromyxedema-like illness of renal disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:55-60.

- Reddy IS, Somani VK, Swarnalata G, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis following hair-dye ingestion induced acute renal failure. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;76:400-403.

- Marckmann P, Skov L, Rossen K, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: suspected causative role of gadodiamide used for contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2359-2362.

- Cheong BYC, Muthupillai R. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a concise review for cardiologists. Texas Heart Inst J. 2010;37:508-515.

- Rogosnitzky M, Branch S. Gadolinium-based contrast agent toxicity: a review of known and proposed mechanisms. BioMetals. 2016;29:365-376.

- Girardi M, Kay J, Elston DM, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: clinicopathological definition and workup recommendations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1095-1106.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: new warnings for using gadolinium-based contrast agents in patients with kidney dysfunction. Updated February 6, 2018. Accessed November 22, 2021. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm223966.htm

- Leung N, Pittelkow MR, Lee CU, et al. Chelation of gadolinium with deferoxamine in a patient with nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. NDT Plus. 2009;2:309-311.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) is a rare debilitating disorder characterized by dermal plaques, joint contractures, and fibrosis of the skin with possible involvement of muscles and internal organs.1-3 Originally identified in 1997 as nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy to describe its characteristic cutaneous thickening and hardening, the name was changed to NSF to more accurately reflect the noncutaneous manifestations present in other organ tissues.2,4,5 Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis occurs in patients with a history of renal insufficiency and exposure to gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) used in magnetic resonance angiography and magnetic resonance imaging. There is no predilection for age, sex, or ethnicity.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis may develop over a period of days to several weeks. However, there have been cases of NSF developing 10 years after gadolinium exposure.2 In most cases, patients have a history of severe chronic renal disease requiring hemodialysis. There have been a few reported cases of NSF occurring in patients with resolved acute kidney injury or resolved acute on chronic renal disease.1,6-10 We present a case of NSF occurring in a patient with resolved transient renal insufficiency and no history of chronic renal disease.

Case Report

A 68-year-old woman presented with new dark, painless, pink plaques on the right thigh and calf. The patient stated the condition started and got worse after she was hospitalized 12 years prior for lower extremity cellulitis, sepsis, and acute renal failure. The patient developed complications during that hospital stay and underwent a renal biopsy and renal artery embolization requiring use of a GBCA. After the procedure, she noticed skin hardening in the extremities and decreased mobility in both legs while she was still in the hospital. It was thought that the lower leg changes were due to cellulitis. Therefore, when the renal issues resolved, she was discharged. Her skin and joint changes remained stable until 6 years later when she noticed new pink plaques appearing. Her medical history was positive for breast cancer, which was surgically and medically treated 16 years prior to presentation.

On presentation, physical examination revealed dark pink, hyperpigmented plaques on the right leg and a firm hypopigmented broad linear plaque on the right forearm. Palpation of the legs revealed thickened sclerotic plaques from the thighs down to the ankles (Figure 1). The plaques were not tender to palpation. She did have a decreased range of motion with eversion and inversion of the feet and ankles.

Biopsies from the right medial leg and right volar forearm showed increased bland dermal spindle cellularity associated with numerous round to ovoid osteoid aggregates encircling elastic fibers and surrounded by osteoblasts (Figure 2). CD34 immunohistochemistry showed general retention of staining within the dermal fibroblast population, and elastin stain showed general retention of elastic fiber bundles and thickening.

Laboratory workup included a complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid-stimulating hormone level, and serum protein electrophoresis; results were all within reference range. The patient also had a urine element profile from an outside provider 1 month after presenting to our office that showed an elevated urine gadolinium level of 4.146 μg/g (reference range, 0–0.019 μg/g). The patient’s skin lesions have remained stable, and she is now working with physical therapy to help with her range of motion.

Comment

Gadolinium Causing Fibrosis—The incidence of NSF varies according to the severity of renal impairment, dosage level of GBCA used, and the history of GBCA use. In patients with normal renal function, gadolinium is excreted within 90 minutes. In patients with severe renal disease, the half-life can increase to up to 34.3 hours.11 Reduced renal clearance and increased half-life of gadolinium lead to prolonged excretion, causing the GBCA to become unstable and dissociate into its constituents, leading to tissue deposition of Gd3+ cations. This dissociation is thought to be due to differences in the stability of the various chelation complexes among the different formulations of GBCAs.12 The mechanism by which the dissociated gadolinium causes the fibrosis in the skin or other organs of the body is still unknown. Furthermore, even patients with normal renal function who undergo repeated administration of GBCA have been found to have higher levels of Gd3+ in their tissues, even in the absence of symptoms.13

Diagnosing NSF—In 2011, Girardi et al14 created a clinical and histopathological scoring system to help diagnose NSF. Clinical findings can be broken down into major criteria and minor criteria. Major criteria consist of patterned plaques, joint contractures, cobblestoning, marked induration, or peau d’orange change. Minor criteria consist of puckering, linear banding, superficial plaques or patches, dermal papules, and scleral plaques. Histopathologic findings include increased dermal cellularity (score +1), CD34+ cells with tram tracking (score +1), thickened or thin collagen bundles (score +1), preserved elastic fibers (score −1), septal involvement (score +1), and osseous metaplasia (score +3)(eTable).14

Differential Diagnosis—The differential diagnosis of NSF includes scleromyxedema, scleroderma, eosinophilic fasciitis, eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome, lipodermatosclerosis, morphea, and chronic graft-vs-host disease. Histopathologic examination of scleromyxedema can look identical to NSF. Therefore, a review of the patient’s medical history, prior hospitalizations, and prior gadolinium exposure is important. Appropriate laboratory workups should be ordered to rule out the other differential diagnoses.

NSF and Kidney Injury—A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms NSF with kidney injury revealed 7 cases of NSF occurring in patients who either had resolved acute kidney injury or resolved acute on chronic kidney disease.1,6-10 Of those cases, 3 reported NSF occurring in patients with completely resolved acute kidney injury.6,7,10 One of those cases involved a 65-year-old man who developed acute renal failure due to acute tubular necrosis.7 He had no history of renal disease prior to hospitalization. His skin lesions continued to improve as his renal function normalized back to baseline after discharge.7 The second case involved a 42-year-old man who had repeated exposure to GBCAs during a brief period of acute kidney injury.6 Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis developed after his renal function normalized. The authors did not mention if there was clinical improvement.6 The third case involved a 22-year-old man who developed acute renal failure after ingestion of hair dye. He did not have a history of chronic renal disease, and as he recovered from the acute kidney injury, almost all of the skin lesions cleared after 1 year.10

Our patient did not have a history of chronic renal disease when she presented to the hospital for sepsis and acute tubular necrosis. Unlike 2 of the prior cases, she did not notice improvement of the skin lesions as the renal function returned to baseline. She continued to experience changes in the skin, even up to 5 years after, and then stabilized. Throughout that time, her renal function was normal. Interestingly, despite having a normal creatinine level, the patient had an elevated gadolinium level on the urine gadolinium test, which typically is not a standard test for NSF. However, the elevated value does shed light on the persistence of gadolinium in the patient despite her exposure having been more than 10 years earlier.

Treatment of NSF—There is no gold standard treatment of NSF, and reversing the fibrosis has proven to be difficult. Avoidance of GBCAs in acute kidney injury or chronic severe renal disease, as recommended by the US Food and Drug Administration, is key to preventing this debilitating disease.15 Restoration of renal function is essential for excreting the gadolinium and improvement in NSF.12 Physical and occupational therapy can improve joint mobility. Therapies such as extracorporeal photopheresis, sodium thiosulfate, pentoxifylline, glucocorticoids, plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclophosphamide, imatinib mesylate, intralesional interferon alfa, topical calcipotriene, corticosteroids, and UVA1 light therapy have been used with varying results.12 It has been suggested that renal transplantation can stop the progression of NSF. However, in the cases we reviewed, renal transplantation would not have benefited those patients because their renal function normalized.6,7,10 Additionally, even though our patient’s renal function normalized after discharge from the hospital, she continued to see more skin lesions developing, likely due to the accumulated gadolinium that was already in her tissue. The possibility of chelation therapy to remove the gadolinium has been proposed. In 1 case study involving deferoxamine injected intramuscularly in a patient with NSF, the urine excretion of gadolinium increased almost 2-fold, but there was no change in the serum concentration level of gadolinium or improvement in the patient’s clinical symptoms.16 We anticipate that our patient’s symptoms will slowly improve, as her body is still excreting the gadolinium. Our patient also was added to the International NSF Registry that was created by Dr. Shawn E. Cowper at the Yale School of Medicine (New Haven, Connecticut).

Conclusion

We report a rare case of NSF occurring in a patient with resolved acute kidney injury and no history of chronic renal disease. Our patient initially did not improve after her renal function normalized, as she continued to develop lesions 10 years after the exposure. Her elevated urine gadolinium excretion level also sheds light on the persistence of gadolinium in her body despite her normal renal function 10 years after her exposure. Although her clinical symptoms have stabilized, our case reiterates the complex pathology of this entity and challenge regarding treatment options. Physicians should be aware that NSF can still occur in healthy patients with no chronic renal disease who have had an episode of acute renal insufficiency along with exposure to a GBCA.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) is a rare debilitating disorder characterized by dermal plaques, joint contractures, and fibrosis of the skin with possible involvement of muscles and internal organs.1-3 Originally identified in 1997 as nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy to describe its characteristic cutaneous thickening and hardening, the name was changed to NSF to more accurately reflect the noncutaneous manifestations present in other organ tissues.2,4,5 Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis occurs in patients with a history of renal insufficiency and exposure to gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) used in magnetic resonance angiography and magnetic resonance imaging. There is no predilection for age, sex, or ethnicity.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis may develop over a period of days to several weeks. However, there have been cases of NSF developing 10 years after gadolinium exposure.2 In most cases, patients have a history of severe chronic renal disease requiring hemodialysis. There have been a few reported cases of NSF occurring in patients with resolved acute kidney injury or resolved acute on chronic renal disease.1,6-10 We present a case of NSF occurring in a patient with resolved transient renal insufficiency and no history of chronic renal disease.

Case Report

A 68-year-old woman presented with new dark, painless, pink plaques on the right thigh and calf. The patient stated the condition started and got worse after she was hospitalized 12 years prior for lower extremity cellulitis, sepsis, and acute renal failure. The patient developed complications during that hospital stay and underwent a renal biopsy and renal artery embolization requiring use of a GBCA. After the procedure, she noticed skin hardening in the extremities and decreased mobility in both legs while she was still in the hospital. It was thought that the lower leg changes were due to cellulitis. Therefore, when the renal issues resolved, she was discharged. Her skin and joint changes remained stable until 6 years later when she noticed new pink plaques appearing. Her medical history was positive for breast cancer, which was surgically and medically treated 16 years prior to presentation.

On presentation, physical examination revealed dark pink, hyperpigmented plaques on the right leg and a firm hypopigmented broad linear plaque on the right forearm. Palpation of the legs revealed thickened sclerotic plaques from the thighs down to the ankles (Figure 1). The plaques were not tender to palpation. She did have a decreased range of motion with eversion and inversion of the feet and ankles.

Biopsies from the right medial leg and right volar forearm showed increased bland dermal spindle cellularity associated with numerous round to ovoid osteoid aggregates encircling elastic fibers and surrounded by osteoblasts (Figure 2). CD34 immunohistochemistry showed general retention of staining within the dermal fibroblast population, and elastin stain showed general retention of elastic fiber bundles and thickening.

Laboratory workup included a complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid-stimulating hormone level, and serum protein electrophoresis; results were all within reference range. The patient also had a urine element profile from an outside provider 1 month after presenting to our office that showed an elevated urine gadolinium level of 4.146 μg/g (reference range, 0–0.019 μg/g). The patient’s skin lesions have remained stable, and she is now working with physical therapy to help with her range of motion.

Comment

Gadolinium Causing Fibrosis—The incidence of NSF varies according to the severity of renal impairment, dosage level of GBCA used, and the history of GBCA use. In patients with normal renal function, gadolinium is excreted within 90 minutes. In patients with severe renal disease, the half-life can increase to up to 34.3 hours.11 Reduced renal clearance and increased half-life of gadolinium lead to prolonged excretion, causing the GBCA to become unstable and dissociate into its constituents, leading to tissue deposition of Gd3+ cations. This dissociation is thought to be due to differences in the stability of the various chelation complexes among the different formulations of GBCAs.12 The mechanism by which the dissociated gadolinium causes the fibrosis in the skin or other organs of the body is still unknown. Furthermore, even patients with normal renal function who undergo repeated administration of GBCA have been found to have higher levels of Gd3+ in their tissues, even in the absence of symptoms.13

Diagnosing NSF—In 2011, Girardi et al14 created a clinical and histopathological scoring system to help diagnose NSF. Clinical findings can be broken down into major criteria and minor criteria. Major criteria consist of patterned plaques, joint contractures, cobblestoning, marked induration, or peau d’orange change. Minor criteria consist of puckering, linear banding, superficial plaques or patches, dermal papules, and scleral plaques. Histopathologic findings include increased dermal cellularity (score +1), CD34+ cells with tram tracking (score +1), thickened or thin collagen bundles (score +1), preserved elastic fibers (score −1), septal involvement (score +1), and osseous metaplasia (score +3)(eTable).14

Differential Diagnosis—The differential diagnosis of NSF includes scleromyxedema, scleroderma, eosinophilic fasciitis, eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome, lipodermatosclerosis, morphea, and chronic graft-vs-host disease. Histopathologic examination of scleromyxedema can look identical to NSF. Therefore, a review of the patient’s medical history, prior hospitalizations, and prior gadolinium exposure is important. Appropriate laboratory workups should be ordered to rule out the other differential diagnoses.

NSF and Kidney Injury—A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms NSF with kidney injury revealed 7 cases of NSF occurring in patients who either had resolved acute kidney injury or resolved acute on chronic kidney disease.1,6-10 Of those cases, 3 reported NSF occurring in patients with completely resolved acute kidney injury.6,7,10 One of those cases involved a 65-year-old man who developed acute renal failure due to acute tubular necrosis.7 He had no history of renal disease prior to hospitalization. His skin lesions continued to improve as his renal function normalized back to baseline after discharge.7 The second case involved a 42-year-old man who had repeated exposure to GBCAs during a brief period of acute kidney injury.6 Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis developed after his renal function normalized. The authors did not mention if there was clinical improvement.6 The third case involved a 22-year-old man who developed acute renal failure after ingestion of hair dye. He did not have a history of chronic renal disease, and as he recovered from the acute kidney injury, almost all of the skin lesions cleared after 1 year.10

Our patient did not have a history of chronic renal disease when she presented to the hospital for sepsis and acute tubular necrosis. Unlike 2 of the prior cases, she did not notice improvement of the skin lesions as the renal function returned to baseline. She continued to experience changes in the skin, even up to 5 years after, and then stabilized. Throughout that time, her renal function was normal. Interestingly, despite having a normal creatinine level, the patient had an elevated gadolinium level on the urine gadolinium test, which typically is not a standard test for NSF. However, the elevated value does shed light on the persistence of gadolinium in the patient despite her exposure having been more than 10 years earlier.

Treatment of NSF—There is no gold standard treatment of NSF, and reversing the fibrosis has proven to be difficult. Avoidance of GBCAs in acute kidney injury or chronic severe renal disease, as recommended by the US Food and Drug Administration, is key to preventing this debilitating disease.15 Restoration of renal function is essential for excreting the gadolinium and improvement in NSF.12 Physical and occupational therapy can improve joint mobility. Therapies such as extracorporeal photopheresis, sodium thiosulfate, pentoxifylline, glucocorticoids, plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclophosphamide, imatinib mesylate, intralesional interferon alfa, topical calcipotriene, corticosteroids, and UVA1 light therapy have been used with varying results.12 It has been suggested that renal transplantation can stop the progression of NSF. However, in the cases we reviewed, renal transplantation would not have benefited those patients because their renal function normalized.6,7,10 Additionally, even though our patient’s renal function normalized after discharge from the hospital, she continued to see more skin lesions developing, likely due to the accumulated gadolinium that was already in her tissue. The possibility of chelation therapy to remove the gadolinium has been proposed. In 1 case study involving deferoxamine injected intramuscularly in a patient with NSF, the urine excretion of gadolinium increased almost 2-fold, but there was no change in the serum concentration level of gadolinium or improvement in the patient’s clinical symptoms.16 We anticipate that our patient’s symptoms will slowly improve, as her body is still excreting the gadolinium. Our patient also was added to the International NSF Registry that was created by Dr. Shawn E. Cowper at the Yale School of Medicine (New Haven, Connecticut).

Conclusion

We report a rare case of NSF occurring in a patient with resolved acute kidney injury and no history of chronic renal disease. Our patient initially did not improve after her renal function normalized, as she continued to develop lesions 10 years after the exposure. Her elevated urine gadolinium excretion level also sheds light on the persistence of gadolinium in her body despite her normal renal function 10 years after her exposure. Although her clinical symptoms have stabilized, our case reiterates the complex pathology of this entity and challenge regarding treatment options. Physicians should be aware that NSF can still occur in healthy patients with no chronic renal disease who have had an episode of acute renal insufficiency along with exposure to a GBCA.

- Cowper SE, Su LD, Bhawan J, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:383-393.

- Grobner T. Gadolinium—a specific trigger for the development of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1104-1108.

- Larson KN, Gagnon AL, Darling MD, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis manifesting a decade after exposure to gadolinium. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1117-1120.

- Mendoza FA, Artlett CM, Sandorfi N, et al. Description of 12 cases of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:238-249.

- Ting WW, Stone MS, Madison KC, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy with systemic involvement. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:903-906.

- Lu CF, Hsiao CH, Tjiu JW. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis developed after recovery from acute renal failure: gadolinium as a possible aetiological factor. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:339-340.

- Cassis TB, Jackson JM, Sonnier GB, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy in a patient with acute renal failure never requiring dialysis. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:56-59.

- Swartz RD, Crofford LJ, Phan SH, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: a novel cutaneous fibrosing disorder in patients with renal failure. Am J Med. 2003;114:563-572.

- Mackay-Wiggan JM, Cohen DJ, Hardy MA, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (scleromyxedema-like illness of renal disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:55-60.

- Reddy IS, Somani VK, Swarnalata G, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis following hair-dye ingestion induced acute renal failure. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;76:400-403.

- Marckmann P, Skov L, Rossen K, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: suspected causative role of gadodiamide used for contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2359-2362.

- Cheong BYC, Muthupillai R. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a concise review for cardiologists. Texas Heart Inst J. 2010;37:508-515.

- Rogosnitzky M, Branch S. Gadolinium-based contrast agent toxicity: a review of known and proposed mechanisms. BioMetals. 2016;29:365-376.

- Girardi M, Kay J, Elston DM, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: clinicopathological definition and workup recommendations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1095-1106.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: new warnings for using gadolinium-based contrast agents in patients with kidney dysfunction. Updated February 6, 2018. Accessed November 22, 2021. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm223966.htm

- Leung N, Pittelkow MR, Lee CU, et al. Chelation of gadolinium with deferoxamine in a patient with nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. NDT Plus. 2009;2:309-311.

- Cowper SE, Su LD, Bhawan J, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:383-393.

- Grobner T. Gadolinium—a specific trigger for the development of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1104-1108.

- Larson KN, Gagnon AL, Darling MD, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis manifesting a decade after exposure to gadolinium. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1117-1120.

- Mendoza FA, Artlett CM, Sandorfi N, et al. Description of 12 cases of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:238-249.

- Ting WW, Stone MS, Madison KC, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy with systemic involvement. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:903-906.

- Lu CF, Hsiao CH, Tjiu JW. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis developed after recovery from acute renal failure: gadolinium as a possible aetiological factor. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:339-340.

- Cassis TB, Jackson JM, Sonnier GB, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy in a patient with acute renal failure never requiring dialysis. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:56-59.

- Swartz RD, Crofford LJ, Phan SH, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: a novel cutaneous fibrosing disorder in patients with renal failure. Am J Med. 2003;114:563-572.

- Mackay-Wiggan JM, Cohen DJ, Hardy MA, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (scleromyxedema-like illness of renal disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:55-60.

- Reddy IS, Somani VK, Swarnalata G, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis following hair-dye ingestion induced acute renal failure. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;76:400-403.

- Marckmann P, Skov L, Rossen K, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: suspected causative role of gadodiamide used for contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2359-2362.

- Cheong BYC, Muthupillai R. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a concise review for cardiologists. Texas Heart Inst J. 2010;37:508-515.

- Rogosnitzky M, Branch S. Gadolinium-based contrast agent toxicity: a review of known and proposed mechanisms. BioMetals. 2016;29:365-376.

- Girardi M, Kay J, Elston DM, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: clinicopathological definition and workup recommendations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1095-1106.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: new warnings for using gadolinium-based contrast agents in patients with kidney dysfunction. Updated February 6, 2018. Accessed November 22, 2021. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm223966.htm

- Leung N, Pittelkow MR, Lee CU, et al. Chelation of gadolinium with deferoxamine in a patient with nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. NDT Plus. 2009;2:309-311.

Practice Points

- Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis may occur in patients with a history of renal insufficiency and exposure to gadolinium-based contrast agents.

- Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis may develop over a period of days to several years after exposure.

- Symptoms of this rare disease can progress and get worse even after renal function normalizes.