User login

Investigators based in France and the United States analyzed data for almost 800 patients with DSM-IV–diagnosed PD.

Results showed that having a “general psychopathology factor,” defined as the shared effects of all comorbid conditions, or PD liability, significantly and independently predicted 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD symptoms.

Having a lower physical health-related quality of life (QOL), a greater number of stressful life events, and not seeking treatment at baseline were also significant and independent predictors.

“This integrative model could help clinicians to identify individuals at high risk of recurrence or persistence of panic disorder and provide content for future research,” Valentin Scheer, MD, MPH, a resident in psychiatry at AP-HP, Assistance Publique, Hôpitaux de Paris, and colleagues wrote.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Integration needed

PD is a disabling disorder with a “chronic course” – and a recurrence rate ranging from 25% to 50%, the investigators noted.

“Because of the heterogeneous course of PD, there is a need to develop a comprehensive predictive model of recurrence or persistence,” they wrote. This could “help practitioners adapt therapeutic strategies and develop prevention strategies in high-risk individuals.”

Most previous studies that have investigated risk factors for PD recurrence and persistence have relied on clinical samples, often with limited sample sizes.

Moreover, each risk factor, when considered individually, accounts for only a “small proportion” of the variance in risk, the researchers noted. The co-occurrence of these risk factors “suggests the need to combine them into a broad multivariable model.”

However, currently proposed integrative models do not identify independent predictors or mitigate the influence of confounding variables. To fill this gap, the investigators conducted a study using structural equation modeling “to take into account multiple correlations across predictors.”

They drew on data from 775 participants (mean age, 40 years) in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). For the current analysis, they examined two waves of NESARC (2001-2002 and 2004-2005) to “build a comprehensive model” of the 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD.

The researchers used a “latent variable approach” that simultaneously examined the effect of the following five groups of potential predictors of recurrence or persistence: PD severity, severity of comorbidity, family history of psychiatric disorders, sociodemographic characteristics, and treatment-seeking behavior.

They also distinguished between risk factors responsible for recurrence and those responsible for persistence.

Psychiatric diagnoses were determined on the basis of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV. Participants also completed Version 2 of the Short Form 12-Item Health Survey, which assesses both mental and physical QOL over the previous 4 weeks.

Early treatment needed

Among participants with a 12-month diagnosis of PD at wave 1, 13% had persistent PD and 27.6% had recurrent PD during the 3-year period. The mean duration of illness was 9.5 years.

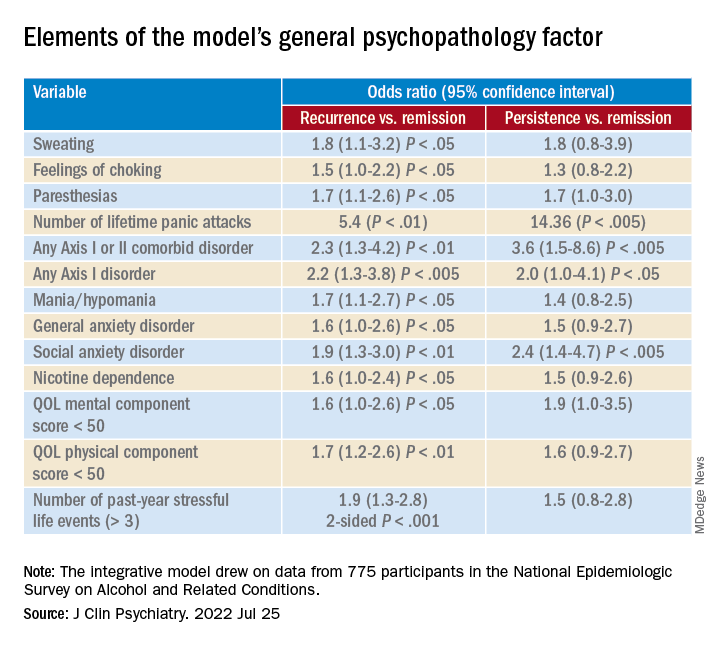

A greater number of lifetime panic attacks, the presence of any Axis I or II comorbid disorder, and any Axis I disorder, especially social anxiety disorder, were significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence and for persistence.

Sweating, choking, paresthesias, the comorbid disorders of mania/hypomania and general anxiety disorder, nicotine dependence, lower mental and physical QOL scores, and exposure to a greater number of stressful life events in the previous year were all significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence.

Only variables shown with a P value were statistically significant, “with the a priori fixed at .05,” the researchers noted.

A combination of psychopathology factors, such as the shared effect of all comorbid psychiatric conditions, PD liability, lower physical health-related QOL, more life stressors during the past year, and not seeking treatment at baseline “significantly and independently” predicted recurrence or persistence of symptoms between the two waves (all Ps < .05), the investigators reported.

One study limitation cited was that several psychiatric disorders known to be associated with PD recurrence or persistence, such as borderline personality disorder, were not examined. Additionally, the study used a 3-year follow-up period – and the results might have differed for other follow-up time frames, the researchers noted.

Nevertheless, the findings constitute a “comprehensive model” to predict recurrence and persistence of PD, they wrote. Moreover, early treatment-seeking behavior “should be promoted, as it may reduce the risk of recurrence.”

Not much new?

Commenting on the study, Peter Roy-Byrne, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Washington, Seattle, noted, “there is not much that is new here.”

Dr. Roy-Byrne, who was not involved with the study, said that a “general theme for years has been that more severe illness, whether you measure it by greater number of other Axis I disorders or symptom severity or a general psychopathology factor, usually predicts worse outcome – here codified as persistence and recurrence.”

Greater stress and reluctance to seek treatment may also predict worse outcomes, he noted.

In addition, the study “did not examine another very important factor: the degree of social connection/social support that someone has,” Dr. Roy-Byrne said. However, “perhaps some of this was contained in specific life events.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators based in France and the United States analyzed data for almost 800 patients with DSM-IV–diagnosed PD.

Results showed that having a “general psychopathology factor,” defined as the shared effects of all comorbid conditions, or PD liability, significantly and independently predicted 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD symptoms.

Having a lower physical health-related quality of life (QOL), a greater number of stressful life events, and not seeking treatment at baseline were also significant and independent predictors.

“This integrative model could help clinicians to identify individuals at high risk of recurrence or persistence of panic disorder and provide content for future research,” Valentin Scheer, MD, MPH, a resident in psychiatry at AP-HP, Assistance Publique, Hôpitaux de Paris, and colleagues wrote.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Integration needed

PD is a disabling disorder with a “chronic course” – and a recurrence rate ranging from 25% to 50%, the investigators noted.

“Because of the heterogeneous course of PD, there is a need to develop a comprehensive predictive model of recurrence or persistence,” they wrote. This could “help practitioners adapt therapeutic strategies and develop prevention strategies in high-risk individuals.”

Most previous studies that have investigated risk factors for PD recurrence and persistence have relied on clinical samples, often with limited sample sizes.

Moreover, each risk factor, when considered individually, accounts for only a “small proportion” of the variance in risk, the researchers noted. The co-occurrence of these risk factors “suggests the need to combine them into a broad multivariable model.”

However, currently proposed integrative models do not identify independent predictors or mitigate the influence of confounding variables. To fill this gap, the investigators conducted a study using structural equation modeling “to take into account multiple correlations across predictors.”

They drew on data from 775 participants (mean age, 40 years) in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). For the current analysis, they examined two waves of NESARC (2001-2002 and 2004-2005) to “build a comprehensive model” of the 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD.

The researchers used a “latent variable approach” that simultaneously examined the effect of the following five groups of potential predictors of recurrence or persistence: PD severity, severity of comorbidity, family history of psychiatric disorders, sociodemographic characteristics, and treatment-seeking behavior.

They also distinguished between risk factors responsible for recurrence and those responsible for persistence.

Psychiatric diagnoses were determined on the basis of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV. Participants also completed Version 2 of the Short Form 12-Item Health Survey, which assesses both mental and physical QOL over the previous 4 weeks.

Early treatment needed

Among participants with a 12-month diagnosis of PD at wave 1, 13% had persistent PD and 27.6% had recurrent PD during the 3-year period. The mean duration of illness was 9.5 years.

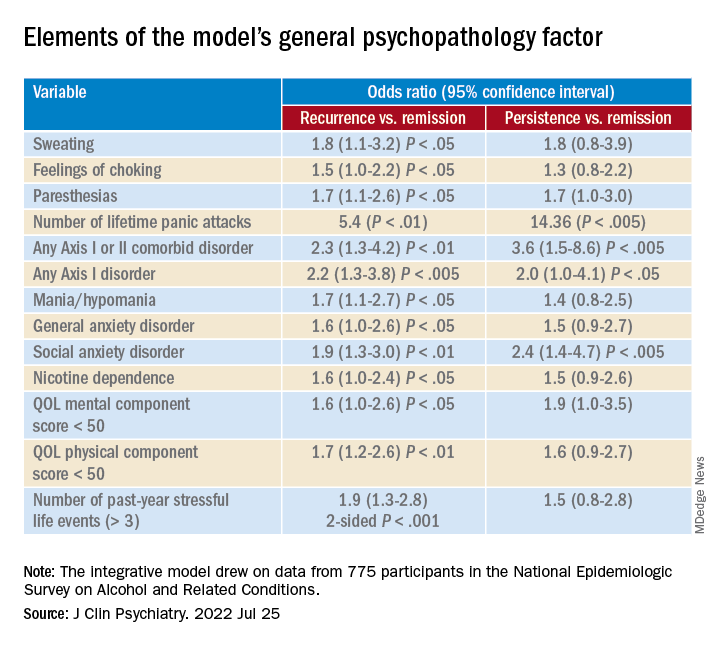

A greater number of lifetime panic attacks, the presence of any Axis I or II comorbid disorder, and any Axis I disorder, especially social anxiety disorder, were significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence and for persistence.

Sweating, choking, paresthesias, the comorbid disorders of mania/hypomania and general anxiety disorder, nicotine dependence, lower mental and physical QOL scores, and exposure to a greater number of stressful life events in the previous year were all significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence.

Only variables shown with a P value were statistically significant, “with the a priori fixed at .05,” the researchers noted.

A combination of psychopathology factors, such as the shared effect of all comorbid psychiatric conditions, PD liability, lower physical health-related QOL, more life stressors during the past year, and not seeking treatment at baseline “significantly and independently” predicted recurrence or persistence of symptoms between the two waves (all Ps < .05), the investigators reported.

One study limitation cited was that several psychiatric disorders known to be associated with PD recurrence or persistence, such as borderline personality disorder, were not examined. Additionally, the study used a 3-year follow-up period – and the results might have differed for other follow-up time frames, the researchers noted.

Nevertheless, the findings constitute a “comprehensive model” to predict recurrence and persistence of PD, they wrote. Moreover, early treatment-seeking behavior “should be promoted, as it may reduce the risk of recurrence.”

Not much new?

Commenting on the study, Peter Roy-Byrne, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Washington, Seattle, noted, “there is not much that is new here.”

Dr. Roy-Byrne, who was not involved with the study, said that a “general theme for years has been that more severe illness, whether you measure it by greater number of other Axis I disorders or symptom severity or a general psychopathology factor, usually predicts worse outcome – here codified as persistence and recurrence.”

Greater stress and reluctance to seek treatment may also predict worse outcomes, he noted.

In addition, the study “did not examine another very important factor: the degree of social connection/social support that someone has,” Dr. Roy-Byrne said. However, “perhaps some of this was contained in specific life events.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators based in France and the United States analyzed data for almost 800 patients with DSM-IV–diagnosed PD.

Results showed that having a “general psychopathology factor,” defined as the shared effects of all comorbid conditions, or PD liability, significantly and independently predicted 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD symptoms.

Having a lower physical health-related quality of life (QOL), a greater number of stressful life events, and not seeking treatment at baseline were also significant and independent predictors.

“This integrative model could help clinicians to identify individuals at high risk of recurrence or persistence of panic disorder and provide content for future research,” Valentin Scheer, MD, MPH, a resident in psychiatry at AP-HP, Assistance Publique, Hôpitaux de Paris, and colleagues wrote.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Integration needed

PD is a disabling disorder with a “chronic course” – and a recurrence rate ranging from 25% to 50%, the investigators noted.

“Because of the heterogeneous course of PD, there is a need to develop a comprehensive predictive model of recurrence or persistence,” they wrote. This could “help practitioners adapt therapeutic strategies and develop prevention strategies in high-risk individuals.”

Most previous studies that have investigated risk factors for PD recurrence and persistence have relied on clinical samples, often with limited sample sizes.

Moreover, each risk factor, when considered individually, accounts for only a “small proportion” of the variance in risk, the researchers noted. The co-occurrence of these risk factors “suggests the need to combine them into a broad multivariable model.”

However, currently proposed integrative models do not identify independent predictors or mitigate the influence of confounding variables. To fill this gap, the investigators conducted a study using structural equation modeling “to take into account multiple correlations across predictors.”

They drew on data from 775 participants (mean age, 40 years) in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). For the current analysis, they examined two waves of NESARC (2001-2002 and 2004-2005) to “build a comprehensive model” of the 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD.

The researchers used a “latent variable approach” that simultaneously examined the effect of the following five groups of potential predictors of recurrence or persistence: PD severity, severity of comorbidity, family history of psychiatric disorders, sociodemographic characteristics, and treatment-seeking behavior.

They also distinguished between risk factors responsible for recurrence and those responsible for persistence.

Psychiatric diagnoses were determined on the basis of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV. Participants also completed Version 2 of the Short Form 12-Item Health Survey, which assesses both mental and physical QOL over the previous 4 weeks.

Early treatment needed

Among participants with a 12-month diagnosis of PD at wave 1, 13% had persistent PD and 27.6% had recurrent PD during the 3-year period. The mean duration of illness was 9.5 years.

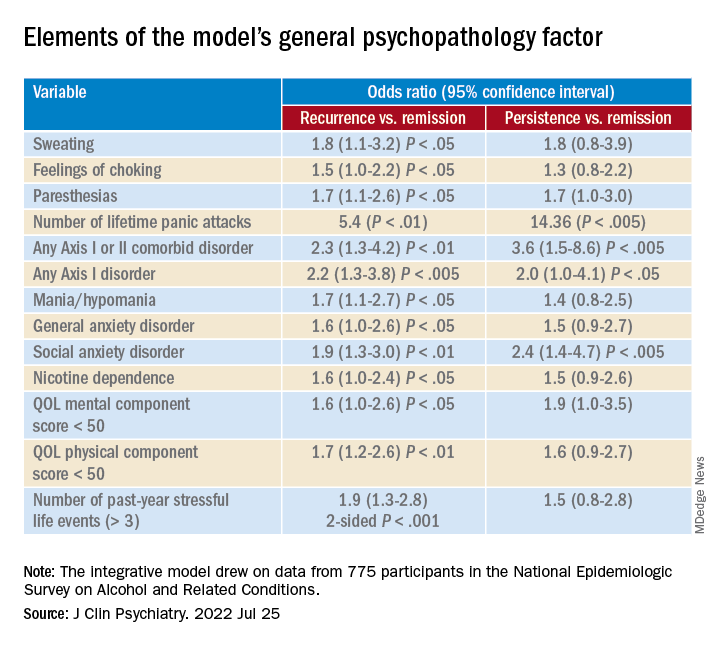

A greater number of lifetime panic attacks, the presence of any Axis I or II comorbid disorder, and any Axis I disorder, especially social anxiety disorder, were significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence and for persistence.

Sweating, choking, paresthesias, the comorbid disorders of mania/hypomania and general anxiety disorder, nicotine dependence, lower mental and physical QOL scores, and exposure to a greater number of stressful life events in the previous year were all significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence.

Only variables shown with a P value were statistically significant, “with the a priori fixed at .05,” the researchers noted.

A combination of psychopathology factors, such as the shared effect of all comorbid psychiatric conditions, PD liability, lower physical health-related QOL, more life stressors during the past year, and not seeking treatment at baseline “significantly and independently” predicted recurrence or persistence of symptoms between the two waves (all Ps < .05), the investigators reported.

One study limitation cited was that several psychiatric disorders known to be associated with PD recurrence or persistence, such as borderline personality disorder, were not examined. Additionally, the study used a 3-year follow-up period – and the results might have differed for other follow-up time frames, the researchers noted.

Nevertheless, the findings constitute a “comprehensive model” to predict recurrence and persistence of PD, they wrote. Moreover, early treatment-seeking behavior “should be promoted, as it may reduce the risk of recurrence.”

Not much new?

Commenting on the study, Peter Roy-Byrne, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Washington, Seattle, noted, “there is not much that is new here.”

Dr. Roy-Byrne, who was not involved with the study, said that a “general theme for years has been that more severe illness, whether you measure it by greater number of other Axis I disorders or symptom severity or a general psychopathology factor, usually predicts worse outcome – here codified as persistence and recurrence.”

Greater stress and reluctance to seek treatment may also predict worse outcomes, he noted.

In addition, the study “did not examine another very important factor: the degree of social connection/social support that someone has,” Dr. Roy-Byrne said. However, “perhaps some of this was contained in specific life events.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY