User login

In college, while most of her fellow students were staying up late and sleeping in, Alice Marshbanks, MD, FHM, was an early riser. Now she regularly works from 4 p.m. to 2 a.m., and she sleeps in most mornings. "I’m sleeping later and living more of a teenage lifestyle," she jokes. "I’m actually getting younger."

Dr. Marshbanks might be an anomaly among established hospitalists. A physician since 1989 and a hospitalist since 1995, she actually prefers working the swing shift, and she says she’s the only one in her group at WakeMed Hospital in Raleigh, N.C., who does. Although Dr. Marshbanks is not a true nocturnist—she doesn’t work the typical 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. graveyard shift—her contracted position provides valuable transition coverage for night admissions, which have increased as the HM program at WakeMed has grown.

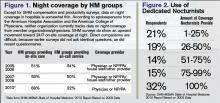

Surveys indicate that HM groups continue to move toward in-house coverage models to provide 24/7 hospitalist responsiveness. In the 2011 SHM-MGMA State of Hospital Medicine report, which will be released next month, 81% of responding nonteaching hospitalist practices reported providing on-site care at night. That’s up from 68% of responding HM practices that reported furnishing that service in the 2010 report. Only 53% of HM groups reported providing on-site night hospitalists in the 2007-2008 State of Hospital Medicine survey, which was produced solely by SHM.

Kenneth R. Epstein, MD, MBA, FACP, FHM, chief medical officer for Hospitalist Consultants Inc., headquartered in Traverse City, Mich., has observed this trend first-hand. In academic hospitals, due to new Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and Resident Review Committee (RRC) regulations, "the only safety valve to handle admissions after the house staff numbers are capped is the hospitalist."

The need for such a safety valve will increase again this summer, as new ACGME duty-hour regulations on resident hours and supervision kick in.

Nonteaching hospitals are not exempt from these pressures. To deal with increasing demands for night coverage, HM groups across the country are using a variety of practice models, such as hiring dedicated nocturnists or moonlighters to cover nights, rotating shifts among team members, or using midlevel providers (physician assistants or nurse practitioners) as night staffers. On-call or in-house coverage models are determined by a variety of factors, including the size of the HM group, patient volume and acuity, and staff availability. Sustainability continues to be a challenge for most groups; however, the in-house coverage model seems to increase nursing and ED satisfaction, most experts say, and is an added value for hospital administration, although financial returns vary.

Continuity of care is at the heart of the night-coverage issue. Some experts worry that patient outcomes will suffer if there isn’t an in-house presence, but studies looking at this issue have been inconclusive, asserts Patti VanDort, RN, MSN, NEA-BC, vice president of nursing and chief nursing officer at Holland Hospital in southwestern Michigan.

"You’ve got to have the same level and quality of care during nights and weekends that you have during the weekdays," she says. "It’s got to be the same for all."

That said, some hospitals don’t have the volume to justify in-house night staffing. Hospitalists and program directors have described the ways in which they handle night staffing, balancing demand, program size, and physician satisfaction.

Tailored to Fit

"Hospitalist programs have different scale and scope depending on the needs of the institution," says Michael R. Humphrey, MD, vice president and chief clinical officer for Emergency and Ambulatory Services at St. Rita’s Medical Center in Lima, Ohio. A 365-bed community hospital, St. Rita’s employs nocturnists as part of its 24-hour hospitalist program. Dr. Humphrey still works as an ED physician and reports that the hospitalists are invaluable for admitting, providing cross-cover, covering the ICU, and handling code blue and rapid responses. "As a Level II trauma center, we can’t have ED physicians leave the department to run upstairs and do codes," he says. "They typically don’t get back within five minutes."

Holland Hospital, a 213-bed facility, provides around-the-clock hospitalist coverage in its eight-bed ICU, according to VanDort. That change was precipitated by the nursing staff’s decision to pursue Magnet Status, which was awarded in 2007 by the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC). For inpatient coverage, the hospital-owned HM group Lakeshore Health Partners, headed by Bart D. Sak, MD, MA, FHM, maintains six FTE hospitalists on a rotating block schedule. Each night, one physician works from 4 p.m. until midnight, overlapping with a nonphysician provider (NPP), a member of the hospitalist group, who works a 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. shift.

"We have two providers in-house when admissions from the ED are heating up, and then we have an NPP in-house to cover the one to three additional admissions that may come in after midnight and to field floor calls," Dr. Sak says.

The physician who worked until midnight is on call for backup support and might come back to the hospital if things get too intense in the pre-dawn hours. "This arrangement works quite well for a program of our size," Dr. Sak says. "It takes a team-oriented approach and experienced NPPs who can work independently."

The Holland approach simply wouldn’t work at Kaiser Permanente’s East Bay site in Oakland, Calif., where Tom Baudendistel, MD, FACP, is part of a 50-member hospitalist group and director of the internal-medicine residency program. "Between codes, cross-cover, ICU, and floor admissions, there is simply too much acuity and volume," he says.

The peak hours for East Bay admissions are mid-afternoon to midnight. Two overnight hospitalist shifts (one from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., another from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m.) are supplemented with two swing shifts (one from 2 to 10 p.m., another from 4 p.m. to midnight). Four full-time nocturnists cover 10 of the 14 overnight shifts per week, which allows for vacation and some protected administrative time. The balance of the overnight shifts are covered by the rest of the hospitalist group, which has 50 members.

The contracted nocturnists are incentivized with additional compensation at the end of the year, when the chief of hospitalists allocates bonuses. They also work fewer shifts a month than the other members of the group. "One thing our group agrees on is that the night docs should get a little more," Dr. Baudendistel says. "It’s a very fair tradeoff for everyone."

A Mile in Their Shoes

Medical directors must balance a variety of factors when scheduling around-the-clock coverage. From day one, the hospitalist program at Albany Memorial Hospital in New York, where John Krisa, MD, is medical director, has been an in-house 24/7 program. Dr. Krisa’s group uses per diem physicians or fellows on their days off to cover most of the nights. The other hospitalists on the team do not escape occasional night duty, and they cover what is left after plugging in the moonlighters. This leaves from zero to five nights per month for each full-time hospitalist. Even the medical director covers night shifts, something Dr. Krisa thinks is valuable to his leadership.

"You, as the leader, still have to walk a mile in that other person’s shoes," he says. "There are different challenges associated with both day and night shifts, so you have to appreciate what your colleagues are going through on the other shifts."

Hospitalist Consultants’ Dr. Epstein agrees with that concept.

"Whenever medical directors have personal experience of how the system is working, they are better able to recommend and make changes," he says.

It’s also valuable, Dr. Krisa explains, for the group leader to interact with ED staff and hear their concerns. Working night shifts helps avoid the night team versus day team schisms, which can lead to group disunity, he says.

Different Skill Set, Different Mindset?

The fact of the matter, though, is that pulling night shifts does not appeal to most established hospitalists. Sleep researchers have found that humans’ body clocks prefer office hours. Even if night-shift hours are consistent, those who work nights never really catch up on the sleep they need during the daytime.

Even so, some physicians embrace the graveyard shift. Working the night swing shift agrees with Dr. Marshbanks’ schedule. The hours are consistent, she works fewer shifts to qualify for FTE pay, and her shift is time-limited, as opposed to work-limited. She’s also filling a niche that others in her group eschew. "It’s a shift that most people with children don’t like because the hours are very disruptive to family life," she says.

The workload at night is different. Instead of the routine rounding typical in day shifts, her work is more urgent. She does more admissions because she works the busiest ED hours, covers acute-stroke codes, and provides cross-cover. And, she says, night staff tends to be "a solid group, so we interact more on a regular basis, since there are fewer of us."

The nocturnists at St. Rita’s Hospital are not held to the same meeting schedule as their daytime hospitalist colleagues, but they’re expected to read meeting minutes and to be responsible for any changes in guidelines or operational information, Dr. Humphrey says. Also stipulated in their hospitalist contracts is the requirement that they maintain competency in procedures, such as central-line placement and airway management.

What’s Better for Patients?

Experts have raised concerns that patient care can be compromised during off-hours, when staffing levels are reduced.1 The Leapfrog Group’s ICU Physician Safety (IPS) Standard argues for high-intensity ICU staffing to reduce patient mortality.2 A number of investigators have tried to determine whether patients admitted off-hours (weekends, nights, holidays) fare worse than those admitted during weekdays. Peter Cram, MD, MBA, acting director of the division of general internal medicine and associate professor of medicine at the Carver College of Medicine at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, found in a 2004 study that patients admitted to hospitals on weekends experienced slightly higher risk-adjusted mortality than did patients admitted on weekdays.3

But here’s the problem with studies such as this, says Dr. Cram: "Patients admitted on evenings and weekends are not the same as those admitted 9 to 5 on weekdays."

During weekdays, admissions combine patients with emergent issues and those scheduled for elective procedures. On weekends, "you get only emergencies—you don’t have low-risk patients," he points out. "So, even with optimal 24/7 staffing, you would still expect those patients coming in at night, and on holidays, to have worse outcomes because they are coming in with more acute problems. It remains an open question whether 24/7 staffing will improve off-hours outcomes." More research, Dr. Cram adds, is needed to establish whether full in-house staffing is the best solution.

Dr. Epstein has compared on-call versus in-house night staffing. In a 2007 study, he found no difference when using indicators such as length of stay, readmission rates, and patient satisfaction.4 However, he noticed positives from in-house coverage. "Although there are no data supporting the value of hospitalists on these parameters, having a nocturnist in-house increases nursing satisfaction, because they are responsive to pages when there is a question about a patient," he says. "It’s also a service to hospital medical staff, because they can handle rapid responses and codes."

There is some evidence that working nights can be deleterious to physicians’ and nurses’ health. One study found that interns were more likely to be involved in collisions after leaving extended night shifts; another found an increased risk of needle-stick injury at the end of a long night shift; and data from the long-running Nurses’ Health Study indicate that long-term night work can result in increased risk of colorectal and breast cancers.5,6,7,8 The increased risks of cancer could be related to lack of exposure to light at night and the body’s decreased production of melatonin, although this remains a topic of ongoing research.

"No Easy Answers"

VanDort, the nursing director, is "passionate" about having 24/7 coverage and reports that her nursing staff is happy with the hybrid model currently used at Holland Hospital. "I do envision a day when we’ll have physicians here around the clock," she says. "Patients are sick during the middle of the night, so you can’t staff your system one way during the daytime hours and your nighttime differently. It’s not fair to those patients."

Dr. Cram, who is a hospitalist, outcomes researcher, and division director, says that in an ideal world, it would make more business sense to have the hospital operating at full capacity around the clock, seven days a week. "But we don’t live in that world," he admits. "It is hard to find ways to achieve ’round-the-clock staffing at the levels we’d like."

He also concludes that there are "no easy answers" to the night-coverage conundrum. "But it might be prudent to think about incentives," he says. "Perhaps we should pay more for staffing weekends, evenings, and holidays, or we could reduce the annual number of shifts we expect our nocturnists to do, relative to those physicians who staff days."

Dr. Krisa says he, too, is biased toward an in-house coverage model, especially when programs reach a critical volume. "There is no substitute for the immediate ability to evaluate a sick patient," he explains. "My feeling is that an in-house, 24/7 presence will become the standard." TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

References

- Wong HJ, Morra D. Excellent hospital care for all: open and operating 24/7. J Gen Intern Med. 2011.

- Pronovost PJ, Angus DC, Dorman T, Robinson KA, Dremsizov TT, Young TL. Physician staffing patterns and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: a systemic review. JAMA. 2002;288(17):2151-2162.

- Cram P, Hillis SL, Barnett M, Rosenthal GE. Effects of weekend admission and hospital teaching status on in-hospital mortality. Am J Med. 2004;117(3):151-157.

- Epstein KR, Juarez E, Loya K, Gorman MJ, Singer A. The effect of 24-7 hospitalist coverage on clinical metrics. Presented May 2007, annual meeting, Society of Hospital Medicine, Dallas.

- Barger LK, Cade BE, Ayas NT, et al. Extended work shifts and the risk of motor vehicle crashes among interns. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:125-134.

- Ayas NT, Barger LK, Cade BE, et al. Extended work duration and the risk of self-reported percutaneous injuries in interns. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1055-1062.

- Schernhammer ES, Laden F, Speizer FE, et al. Night-shift work and risk of colorectal cancer in the nurses’ health study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(11):825-828.

- Schernhammer ES, Laden F, Speizer FE, et al. Rotating night shifts and risk of breast cancer in women partici-pating in the nurses’ health study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(20):1563-1568.

In college, while most of her fellow students were staying up late and sleeping in, Alice Marshbanks, MD, FHM, was an early riser. Now she regularly works from 4 p.m. to 2 a.m., and she sleeps in most mornings. "I’m sleeping later and living more of a teenage lifestyle," she jokes. "I’m actually getting younger."

Dr. Marshbanks might be an anomaly among established hospitalists. A physician since 1989 and a hospitalist since 1995, she actually prefers working the swing shift, and she says she’s the only one in her group at WakeMed Hospital in Raleigh, N.C., who does. Although Dr. Marshbanks is not a true nocturnist—she doesn’t work the typical 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. graveyard shift—her contracted position provides valuable transition coverage for night admissions, which have increased as the HM program at WakeMed has grown.

Surveys indicate that HM groups continue to move toward in-house coverage models to provide 24/7 hospitalist responsiveness. In the 2011 SHM-MGMA State of Hospital Medicine report, which will be released next month, 81% of responding nonteaching hospitalist practices reported providing on-site care at night. That’s up from 68% of responding HM practices that reported furnishing that service in the 2010 report. Only 53% of HM groups reported providing on-site night hospitalists in the 2007-2008 State of Hospital Medicine survey, which was produced solely by SHM.

Kenneth R. Epstein, MD, MBA, FACP, FHM, chief medical officer for Hospitalist Consultants Inc., headquartered in Traverse City, Mich., has observed this trend first-hand. In academic hospitals, due to new Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and Resident Review Committee (RRC) regulations, "the only safety valve to handle admissions after the house staff numbers are capped is the hospitalist."

The need for such a safety valve will increase again this summer, as new ACGME duty-hour regulations on resident hours and supervision kick in.

Nonteaching hospitals are not exempt from these pressures. To deal with increasing demands for night coverage, HM groups across the country are using a variety of practice models, such as hiring dedicated nocturnists or moonlighters to cover nights, rotating shifts among team members, or using midlevel providers (physician assistants or nurse practitioners) as night staffers. On-call or in-house coverage models are determined by a variety of factors, including the size of the HM group, patient volume and acuity, and staff availability. Sustainability continues to be a challenge for most groups; however, the in-house coverage model seems to increase nursing and ED satisfaction, most experts say, and is an added value for hospital administration, although financial returns vary.

Continuity of care is at the heart of the night-coverage issue. Some experts worry that patient outcomes will suffer if there isn’t an in-house presence, but studies looking at this issue have been inconclusive, asserts Patti VanDort, RN, MSN, NEA-BC, vice president of nursing and chief nursing officer at Holland Hospital in southwestern Michigan.

"You’ve got to have the same level and quality of care during nights and weekends that you have during the weekdays," she says. "It’s got to be the same for all."

That said, some hospitals don’t have the volume to justify in-house night staffing. Hospitalists and program directors have described the ways in which they handle night staffing, balancing demand, program size, and physician satisfaction.

Tailored to Fit

"Hospitalist programs have different scale and scope depending on the needs of the institution," says Michael R. Humphrey, MD, vice president and chief clinical officer for Emergency and Ambulatory Services at St. Rita’s Medical Center in Lima, Ohio. A 365-bed community hospital, St. Rita’s employs nocturnists as part of its 24-hour hospitalist program. Dr. Humphrey still works as an ED physician and reports that the hospitalists are invaluable for admitting, providing cross-cover, covering the ICU, and handling code blue and rapid responses. "As a Level II trauma center, we can’t have ED physicians leave the department to run upstairs and do codes," he says. "They typically don’t get back within five minutes."

Holland Hospital, a 213-bed facility, provides around-the-clock hospitalist coverage in its eight-bed ICU, according to VanDort. That change was precipitated by the nursing staff’s decision to pursue Magnet Status, which was awarded in 2007 by the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC). For inpatient coverage, the hospital-owned HM group Lakeshore Health Partners, headed by Bart D. Sak, MD, MA, FHM, maintains six FTE hospitalists on a rotating block schedule. Each night, one physician works from 4 p.m. until midnight, overlapping with a nonphysician provider (NPP), a member of the hospitalist group, who works a 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. shift.

"We have two providers in-house when admissions from the ED are heating up, and then we have an NPP in-house to cover the one to three additional admissions that may come in after midnight and to field floor calls," Dr. Sak says.

The physician who worked until midnight is on call for backup support and might come back to the hospital if things get too intense in the pre-dawn hours. "This arrangement works quite well for a program of our size," Dr. Sak says. "It takes a team-oriented approach and experienced NPPs who can work independently."

The Holland approach simply wouldn’t work at Kaiser Permanente’s East Bay site in Oakland, Calif., where Tom Baudendistel, MD, FACP, is part of a 50-member hospitalist group and director of the internal-medicine residency program. "Between codes, cross-cover, ICU, and floor admissions, there is simply too much acuity and volume," he says.

The peak hours for East Bay admissions are mid-afternoon to midnight. Two overnight hospitalist shifts (one from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., another from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m.) are supplemented with two swing shifts (one from 2 to 10 p.m., another from 4 p.m. to midnight). Four full-time nocturnists cover 10 of the 14 overnight shifts per week, which allows for vacation and some protected administrative time. The balance of the overnight shifts are covered by the rest of the hospitalist group, which has 50 members.

The contracted nocturnists are incentivized with additional compensation at the end of the year, when the chief of hospitalists allocates bonuses. They also work fewer shifts a month than the other members of the group. "One thing our group agrees on is that the night docs should get a little more," Dr. Baudendistel says. "It’s a very fair tradeoff for everyone."

A Mile in Their Shoes

Medical directors must balance a variety of factors when scheduling around-the-clock coverage. From day one, the hospitalist program at Albany Memorial Hospital in New York, where John Krisa, MD, is medical director, has been an in-house 24/7 program. Dr. Krisa’s group uses per diem physicians or fellows on their days off to cover most of the nights. The other hospitalists on the team do not escape occasional night duty, and they cover what is left after plugging in the moonlighters. This leaves from zero to five nights per month for each full-time hospitalist. Even the medical director covers night shifts, something Dr. Krisa thinks is valuable to his leadership.

"You, as the leader, still have to walk a mile in that other person’s shoes," he says. "There are different challenges associated with both day and night shifts, so you have to appreciate what your colleagues are going through on the other shifts."

Hospitalist Consultants’ Dr. Epstein agrees with that concept.

"Whenever medical directors have personal experience of how the system is working, they are better able to recommend and make changes," he says.

It’s also valuable, Dr. Krisa explains, for the group leader to interact with ED staff and hear their concerns. Working night shifts helps avoid the night team versus day team schisms, which can lead to group disunity, he says.

Different Skill Set, Different Mindset?

The fact of the matter, though, is that pulling night shifts does not appeal to most established hospitalists. Sleep researchers have found that humans’ body clocks prefer office hours. Even if night-shift hours are consistent, those who work nights never really catch up on the sleep they need during the daytime.

Even so, some physicians embrace the graveyard shift. Working the night swing shift agrees with Dr. Marshbanks’ schedule. The hours are consistent, she works fewer shifts to qualify for FTE pay, and her shift is time-limited, as opposed to work-limited. She’s also filling a niche that others in her group eschew. "It’s a shift that most people with children don’t like because the hours are very disruptive to family life," she says.

The workload at night is different. Instead of the routine rounding typical in day shifts, her work is more urgent. She does more admissions because she works the busiest ED hours, covers acute-stroke codes, and provides cross-cover. And, she says, night staff tends to be "a solid group, so we interact more on a regular basis, since there are fewer of us."

The nocturnists at St. Rita’s Hospital are not held to the same meeting schedule as their daytime hospitalist colleagues, but they’re expected to read meeting minutes and to be responsible for any changes in guidelines or operational information, Dr. Humphrey says. Also stipulated in their hospitalist contracts is the requirement that they maintain competency in procedures, such as central-line placement and airway management.

What’s Better for Patients?

Experts have raised concerns that patient care can be compromised during off-hours, when staffing levels are reduced.1 The Leapfrog Group’s ICU Physician Safety (IPS) Standard argues for high-intensity ICU staffing to reduce patient mortality.2 A number of investigators have tried to determine whether patients admitted off-hours (weekends, nights, holidays) fare worse than those admitted during weekdays. Peter Cram, MD, MBA, acting director of the division of general internal medicine and associate professor of medicine at the Carver College of Medicine at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, found in a 2004 study that patients admitted to hospitals on weekends experienced slightly higher risk-adjusted mortality than did patients admitted on weekdays.3

But here’s the problem with studies such as this, says Dr. Cram: "Patients admitted on evenings and weekends are not the same as those admitted 9 to 5 on weekdays."

During weekdays, admissions combine patients with emergent issues and those scheduled for elective procedures. On weekends, "you get only emergencies—you don’t have low-risk patients," he points out. "So, even with optimal 24/7 staffing, you would still expect those patients coming in at night, and on holidays, to have worse outcomes because they are coming in with more acute problems. It remains an open question whether 24/7 staffing will improve off-hours outcomes." More research, Dr. Cram adds, is needed to establish whether full in-house staffing is the best solution.

Dr. Epstein has compared on-call versus in-house night staffing. In a 2007 study, he found no difference when using indicators such as length of stay, readmission rates, and patient satisfaction.4 However, he noticed positives from in-house coverage. "Although there are no data supporting the value of hospitalists on these parameters, having a nocturnist in-house increases nursing satisfaction, because they are responsive to pages when there is a question about a patient," he says. "It’s also a service to hospital medical staff, because they can handle rapid responses and codes."

There is some evidence that working nights can be deleterious to physicians’ and nurses’ health. One study found that interns were more likely to be involved in collisions after leaving extended night shifts; another found an increased risk of needle-stick injury at the end of a long night shift; and data from the long-running Nurses’ Health Study indicate that long-term night work can result in increased risk of colorectal and breast cancers.5,6,7,8 The increased risks of cancer could be related to lack of exposure to light at night and the body’s decreased production of melatonin, although this remains a topic of ongoing research.

"No Easy Answers"

VanDort, the nursing director, is "passionate" about having 24/7 coverage and reports that her nursing staff is happy with the hybrid model currently used at Holland Hospital. "I do envision a day when we’ll have physicians here around the clock," she says. "Patients are sick during the middle of the night, so you can’t staff your system one way during the daytime hours and your nighttime differently. It’s not fair to those patients."

Dr. Cram, who is a hospitalist, outcomes researcher, and division director, says that in an ideal world, it would make more business sense to have the hospital operating at full capacity around the clock, seven days a week. "But we don’t live in that world," he admits. "It is hard to find ways to achieve ’round-the-clock staffing at the levels we’d like."

He also concludes that there are "no easy answers" to the night-coverage conundrum. "But it might be prudent to think about incentives," he says. "Perhaps we should pay more for staffing weekends, evenings, and holidays, or we could reduce the annual number of shifts we expect our nocturnists to do, relative to those physicians who staff days."

Dr. Krisa says he, too, is biased toward an in-house coverage model, especially when programs reach a critical volume. "There is no substitute for the immediate ability to evaluate a sick patient," he explains. "My feeling is that an in-house, 24/7 presence will become the standard." TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

References

- Wong HJ, Morra D. Excellent hospital care for all: open and operating 24/7. J Gen Intern Med. 2011.

- Pronovost PJ, Angus DC, Dorman T, Robinson KA, Dremsizov TT, Young TL. Physician staffing patterns and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: a systemic review. JAMA. 2002;288(17):2151-2162.

- Cram P, Hillis SL, Barnett M, Rosenthal GE. Effects of weekend admission and hospital teaching status on in-hospital mortality. Am J Med. 2004;117(3):151-157.

- Epstein KR, Juarez E, Loya K, Gorman MJ, Singer A. The effect of 24-7 hospitalist coverage on clinical metrics. Presented May 2007, annual meeting, Society of Hospital Medicine, Dallas.

- Barger LK, Cade BE, Ayas NT, et al. Extended work shifts and the risk of motor vehicle crashes among interns. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:125-134.

- Ayas NT, Barger LK, Cade BE, et al. Extended work duration and the risk of self-reported percutaneous injuries in interns. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1055-1062.

- Schernhammer ES, Laden F, Speizer FE, et al. Night-shift work and risk of colorectal cancer in the nurses’ health study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(11):825-828.

- Schernhammer ES, Laden F, Speizer FE, et al. Rotating night shifts and risk of breast cancer in women partici-pating in the nurses’ health study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(20):1563-1568.

In college, while most of her fellow students were staying up late and sleeping in, Alice Marshbanks, MD, FHM, was an early riser. Now she regularly works from 4 p.m. to 2 a.m., and she sleeps in most mornings. "I’m sleeping later and living more of a teenage lifestyle," she jokes. "I’m actually getting younger."

Dr. Marshbanks might be an anomaly among established hospitalists. A physician since 1989 and a hospitalist since 1995, she actually prefers working the swing shift, and she says she’s the only one in her group at WakeMed Hospital in Raleigh, N.C., who does. Although Dr. Marshbanks is not a true nocturnist—she doesn’t work the typical 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. graveyard shift—her contracted position provides valuable transition coverage for night admissions, which have increased as the HM program at WakeMed has grown.

Surveys indicate that HM groups continue to move toward in-house coverage models to provide 24/7 hospitalist responsiveness. In the 2011 SHM-MGMA State of Hospital Medicine report, which will be released next month, 81% of responding nonteaching hospitalist practices reported providing on-site care at night. That’s up from 68% of responding HM practices that reported furnishing that service in the 2010 report. Only 53% of HM groups reported providing on-site night hospitalists in the 2007-2008 State of Hospital Medicine survey, which was produced solely by SHM.

Kenneth R. Epstein, MD, MBA, FACP, FHM, chief medical officer for Hospitalist Consultants Inc., headquartered in Traverse City, Mich., has observed this trend first-hand. In academic hospitals, due to new Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and Resident Review Committee (RRC) regulations, "the only safety valve to handle admissions after the house staff numbers are capped is the hospitalist."

The need for such a safety valve will increase again this summer, as new ACGME duty-hour regulations on resident hours and supervision kick in.

Nonteaching hospitals are not exempt from these pressures. To deal with increasing demands for night coverage, HM groups across the country are using a variety of practice models, such as hiring dedicated nocturnists or moonlighters to cover nights, rotating shifts among team members, or using midlevel providers (physician assistants or nurse practitioners) as night staffers. On-call or in-house coverage models are determined by a variety of factors, including the size of the HM group, patient volume and acuity, and staff availability. Sustainability continues to be a challenge for most groups; however, the in-house coverage model seems to increase nursing and ED satisfaction, most experts say, and is an added value for hospital administration, although financial returns vary.

Continuity of care is at the heart of the night-coverage issue. Some experts worry that patient outcomes will suffer if there isn’t an in-house presence, but studies looking at this issue have been inconclusive, asserts Patti VanDort, RN, MSN, NEA-BC, vice president of nursing and chief nursing officer at Holland Hospital in southwestern Michigan.

"You’ve got to have the same level and quality of care during nights and weekends that you have during the weekdays," she says. "It’s got to be the same for all."

That said, some hospitals don’t have the volume to justify in-house night staffing. Hospitalists and program directors have described the ways in which they handle night staffing, balancing demand, program size, and physician satisfaction.

Tailored to Fit

"Hospitalist programs have different scale and scope depending on the needs of the institution," says Michael R. Humphrey, MD, vice president and chief clinical officer for Emergency and Ambulatory Services at St. Rita’s Medical Center in Lima, Ohio. A 365-bed community hospital, St. Rita’s employs nocturnists as part of its 24-hour hospitalist program. Dr. Humphrey still works as an ED physician and reports that the hospitalists are invaluable for admitting, providing cross-cover, covering the ICU, and handling code blue and rapid responses. "As a Level II trauma center, we can’t have ED physicians leave the department to run upstairs and do codes," he says. "They typically don’t get back within five minutes."

Holland Hospital, a 213-bed facility, provides around-the-clock hospitalist coverage in its eight-bed ICU, according to VanDort. That change was precipitated by the nursing staff’s decision to pursue Magnet Status, which was awarded in 2007 by the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC). For inpatient coverage, the hospital-owned HM group Lakeshore Health Partners, headed by Bart D. Sak, MD, MA, FHM, maintains six FTE hospitalists on a rotating block schedule. Each night, one physician works from 4 p.m. until midnight, overlapping with a nonphysician provider (NPP), a member of the hospitalist group, who works a 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. shift.

"We have two providers in-house when admissions from the ED are heating up, and then we have an NPP in-house to cover the one to three additional admissions that may come in after midnight and to field floor calls," Dr. Sak says.

The physician who worked until midnight is on call for backup support and might come back to the hospital if things get too intense in the pre-dawn hours. "This arrangement works quite well for a program of our size," Dr. Sak says. "It takes a team-oriented approach and experienced NPPs who can work independently."

The Holland approach simply wouldn’t work at Kaiser Permanente’s East Bay site in Oakland, Calif., where Tom Baudendistel, MD, FACP, is part of a 50-member hospitalist group and director of the internal-medicine residency program. "Between codes, cross-cover, ICU, and floor admissions, there is simply too much acuity and volume," he says.

The peak hours for East Bay admissions are mid-afternoon to midnight. Two overnight hospitalist shifts (one from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., another from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m.) are supplemented with two swing shifts (one from 2 to 10 p.m., another from 4 p.m. to midnight). Four full-time nocturnists cover 10 of the 14 overnight shifts per week, which allows for vacation and some protected administrative time. The balance of the overnight shifts are covered by the rest of the hospitalist group, which has 50 members.

The contracted nocturnists are incentivized with additional compensation at the end of the year, when the chief of hospitalists allocates bonuses. They also work fewer shifts a month than the other members of the group. "One thing our group agrees on is that the night docs should get a little more," Dr. Baudendistel says. "It’s a very fair tradeoff for everyone."

A Mile in Their Shoes

Medical directors must balance a variety of factors when scheduling around-the-clock coverage. From day one, the hospitalist program at Albany Memorial Hospital in New York, where John Krisa, MD, is medical director, has been an in-house 24/7 program. Dr. Krisa’s group uses per diem physicians or fellows on their days off to cover most of the nights. The other hospitalists on the team do not escape occasional night duty, and they cover what is left after plugging in the moonlighters. This leaves from zero to five nights per month for each full-time hospitalist. Even the medical director covers night shifts, something Dr. Krisa thinks is valuable to his leadership.

"You, as the leader, still have to walk a mile in that other person’s shoes," he says. "There are different challenges associated with both day and night shifts, so you have to appreciate what your colleagues are going through on the other shifts."

Hospitalist Consultants’ Dr. Epstein agrees with that concept.

"Whenever medical directors have personal experience of how the system is working, they are better able to recommend and make changes," he says.

It’s also valuable, Dr. Krisa explains, for the group leader to interact with ED staff and hear their concerns. Working night shifts helps avoid the night team versus day team schisms, which can lead to group disunity, he says.

Different Skill Set, Different Mindset?

The fact of the matter, though, is that pulling night shifts does not appeal to most established hospitalists. Sleep researchers have found that humans’ body clocks prefer office hours. Even if night-shift hours are consistent, those who work nights never really catch up on the sleep they need during the daytime.

Even so, some physicians embrace the graveyard shift. Working the night swing shift agrees with Dr. Marshbanks’ schedule. The hours are consistent, she works fewer shifts to qualify for FTE pay, and her shift is time-limited, as opposed to work-limited. She’s also filling a niche that others in her group eschew. "It’s a shift that most people with children don’t like because the hours are very disruptive to family life," she says.

The workload at night is different. Instead of the routine rounding typical in day shifts, her work is more urgent. She does more admissions because she works the busiest ED hours, covers acute-stroke codes, and provides cross-cover. And, she says, night staff tends to be "a solid group, so we interact more on a regular basis, since there are fewer of us."

The nocturnists at St. Rita’s Hospital are not held to the same meeting schedule as their daytime hospitalist colleagues, but they’re expected to read meeting minutes and to be responsible for any changes in guidelines or operational information, Dr. Humphrey says. Also stipulated in their hospitalist contracts is the requirement that they maintain competency in procedures, such as central-line placement and airway management.

What’s Better for Patients?

Experts have raised concerns that patient care can be compromised during off-hours, when staffing levels are reduced.1 The Leapfrog Group’s ICU Physician Safety (IPS) Standard argues for high-intensity ICU staffing to reduce patient mortality.2 A number of investigators have tried to determine whether patients admitted off-hours (weekends, nights, holidays) fare worse than those admitted during weekdays. Peter Cram, MD, MBA, acting director of the division of general internal medicine and associate professor of medicine at the Carver College of Medicine at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, found in a 2004 study that patients admitted to hospitals on weekends experienced slightly higher risk-adjusted mortality than did patients admitted on weekdays.3

But here’s the problem with studies such as this, says Dr. Cram: "Patients admitted on evenings and weekends are not the same as those admitted 9 to 5 on weekdays."

During weekdays, admissions combine patients with emergent issues and those scheduled for elective procedures. On weekends, "you get only emergencies—you don’t have low-risk patients," he points out. "So, even with optimal 24/7 staffing, you would still expect those patients coming in at night, and on holidays, to have worse outcomes because they are coming in with more acute problems. It remains an open question whether 24/7 staffing will improve off-hours outcomes." More research, Dr. Cram adds, is needed to establish whether full in-house staffing is the best solution.

Dr. Epstein has compared on-call versus in-house night staffing. In a 2007 study, he found no difference when using indicators such as length of stay, readmission rates, and patient satisfaction.4 However, he noticed positives from in-house coverage. "Although there are no data supporting the value of hospitalists on these parameters, having a nocturnist in-house increases nursing satisfaction, because they are responsive to pages when there is a question about a patient," he says. "It’s also a service to hospital medical staff, because they can handle rapid responses and codes."

There is some evidence that working nights can be deleterious to physicians’ and nurses’ health. One study found that interns were more likely to be involved in collisions after leaving extended night shifts; another found an increased risk of needle-stick injury at the end of a long night shift; and data from the long-running Nurses’ Health Study indicate that long-term night work can result in increased risk of colorectal and breast cancers.5,6,7,8 The increased risks of cancer could be related to lack of exposure to light at night and the body’s decreased production of melatonin, although this remains a topic of ongoing research.

"No Easy Answers"

VanDort, the nursing director, is "passionate" about having 24/7 coverage and reports that her nursing staff is happy with the hybrid model currently used at Holland Hospital. "I do envision a day when we’ll have physicians here around the clock," she says. "Patients are sick during the middle of the night, so you can’t staff your system one way during the daytime hours and your nighttime differently. It’s not fair to those patients."

Dr. Cram, who is a hospitalist, outcomes researcher, and division director, says that in an ideal world, it would make more business sense to have the hospital operating at full capacity around the clock, seven days a week. "But we don’t live in that world," he admits. "It is hard to find ways to achieve ’round-the-clock staffing at the levels we’d like."

He also concludes that there are "no easy answers" to the night-coverage conundrum. "But it might be prudent to think about incentives," he says. "Perhaps we should pay more for staffing weekends, evenings, and holidays, or we could reduce the annual number of shifts we expect our nocturnists to do, relative to those physicians who staff days."

Dr. Krisa says he, too, is biased toward an in-house coverage model, especially when programs reach a critical volume. "There is no substitute for the immediate ability to evaluate a sick patient," he explains. "My feeling is that an in-house, 24/7 presence will become the standard." TH

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

References

- Wong HJ, Morra D. Excellent hospital care for all: open and operating 24/7. J Gen Intern Med. 2011.

- Pronovost PJ, Angus DC, Dorman T, Robinson KA, Dremsizov TT, Young TL. Physician staffing patterns and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: a systemic review. JAMA. 2002;288(17):2151-2162.

- Cram P, Hillis SL, Barnett M, Rosenthal GE. Effects of weekend admission and hospital teaching status on in-hospital mortality. Am J Med. 2004;117(3):151-157.

- Epstein KR, Juarez E, Loya K, Gorman MJ, Singer A. The effect of 24-7 hospitalist coverage on clinical metrics. Presented May 2007, annual meeting, Society of Hospital Medicine, Dallas.

- Barger LK, Cade BE, Ayas NT, et al. Extended work shifts and the risk of motor vehicle crashes among interns. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:125-134.

- Ayas NT, Barger LK, Cade BE, et al. Extended work duration and the risk of self-reported percutaneous injuries in interns. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1055-1062.

- Schernhammer ES, Laden F, Speizer FE, et al. Night-shift work and risk of colorectal cancer in the nurses’ health study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(11):825-828.

- Schernhammer ES, Laden F, Speizer FE, et al. Rotating night shifts and risk of breast cancer in women partici-pating in the nurses’ health study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(20):1563-1568.