User login

› Consider novel oral anticoagualants (NOACs) for patients who have normal renal function, are comlpiant with medication regimens, and have no history of peptic ulcer or gastrointestinal bleeding. B

› Avoid overlapping warfarin with rivaroxaban or apixaban when transitioning a patient from one anticoagulant to the other, as both agents prolong prothrombin time. B

› When initiating a NOAC, it is not necessary to overlap with a parenteral anticoagulant. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 Sally J is a 72-year-old Caucasian woman who comes to your clinic after being diagnosed with atrial fibrillation (AF). The patient has a 10-year history of type 2 diabetes; she also has a history of hypertension and chronic kidney disease (CKD), with a baseline creatinine clearance of approximately 40 mL/min. Ms. J tells you she knows people who take warfarin and really dislike it. She asks for your opinion of the new anticoagulants she’s seen advertised on TV, and wonders whether one of them would be right for her.

CASE 2 Bobby W, a 35-year-old African American man, was recently diagnosed with deep vein thrombosis (DVT). This was his second clot in 5 years, and occurred after a long flight home from Europe. The patient explains that he leads a very active lifestyle and doesn’t have the time to come in for the monthly international normalized ratio (INR) checks that warfarin requires. What would you recommend for these patients?

Troubled by warfarin’s narrow therapeutic index, numerous medication and dietary interactions, and need for frequent monitoring, patients requiring long-term oral anticoagulation therapy have been seeking alternatives for years. Finally, they have a choice. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved 3 oral anticoagulants—dabigatran (Pradaxa), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and apixaban (Eliquis)—in less than 4 years. Known as novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs), they are the first such drugs to enter the market in more than 50 years.1,2

While warfarin inhibits a wide range of clotting factors (including II, VII, IX, and X), NOACs work further down the clotting cascade (TABLE 1).1,3-7 Dabigatran, a direct thrombin inhibitor, only inhibits factor IIa.3,5 Rivaroxaban and apixaban directly inhibit factor Xa and indirectly inhibit factor IIa.3,6,7

There are notable advantages to these newer agents, but some disadvantages that must be considered, as well. Appropriate patient selection, guided by a thorough understanding of the benefits and risks of NOACs, is key.

Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation

All 3 NOACs are approved for stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF). The approvals are based on a small number of well-designed trials: RE-LY (dabigatran), ROCKET-AF (rivaroxaban), and ARISTOTLE (apixaban).8-10 Compared with warfarin, dabigatran is the only oral anticoagulant with a lower rate of both hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke.8 Both rivaroxaban and apixaban were found to decrease overall stroke risk relative to warfarin, but the difference was driven by a lower risk for hemorrhagic, not ischemic, stroke.9,10

In these trials, overall rates of major bleeding were similar to that of warfarin.8-10 Patients taking warfarin generally experienced higher rates of intracranial hemorrhage but lower rates of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding than those on NOACs. Relative to warfarin, apixaban was the only NOAC that did not have a higher rate of GI bleeding and the only one with a lower rate of major bleeding.8-10 In addition, apixaban remains the only NOAC found to have a statistically significant decrease in all-cause mortality compared with warfarin.10 Although dabigatran and rivaroxaban were associated with a strong trend towards decreased mortality, both studies were underpowered for this secondary outcome.8,9

Adding NOACs to stroke guidelines. The role of NOACs in the prevention of stroke in patients with nonvalvular AF is beginning to be reflected in newer guidelines. The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP)’s 2012 guidelines recommend dabigatran over warfarin (grade 2B—weak recommendation; moderate quality evidence) unless the patient is well controlled on warfarin.11 The European Society of Cardiology (ESC)’s 2012 guidelines recommend dabigatran, apixaban, and rivaroxaban as broadly preferable to warfarin, while noting that experience with these agents is limited and appropriate patient selection is important.12

Anticoagulation to treat—and prevent—VTE

The standard of care for acute venous thromboembolism (VTE) is to initiate warfarin along with a parenteral anticoagulant, such as unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), or fondaparinux.13 Due to warfarin’s slow onset to peak effect, a parenteral anticoagulant is overlapped for ≥5 days—until warfarin reaches a therapeutic level and can be continued as monotherapy.13 But many patients find subcutaneous delivery of LMWH disagreeable and costly and frequent INR monitoring inconvenient, so the new agents offer notable advantages.

In well-designed studies, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban have all been shown to be noninferior to warfarin in the initial treatment of acute DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE).14-17 All 3 agents were also shown to have lower rates of major bleeding than warfarin. Rivaroxaban and apixaban were also superior to warfarin with regard to bleeding events, and dabigatran was noninferior to warfarin for this outcome.14-17

NOACs help prevent recurrence

All 3 NOACs have been studied for long-term prevention of recurrent VTE after 3 to 18 months of anticoagulation, as well. Dabigatran was found in the RE-MEDY trial to be noninferior to warfarin for the risk of recurrent VTE, and to have lower rates of bleeding.18 In separate trials, all 3 agents were superior to placebo in preventing recurrent VTE. Rates of long-term major bleeding were significantly higher than placebo with rivaroxaban and dabigatran, but not with apixaban.15,18,19

Rivaroxaban is the only NOAC to be FDA approved for the treatment of acute DVT and PE, and the ACCP’s 2012 guidelines list it as a viable alternative to parenteral anticoagulation when initiating treatment for acute VTE.6,13 When treating VTE long term, the guidelines continue to recommend warfarin or LMWH rather than dabigatran or rivaroxaban.13 Recommendations may change in coming years, as physicians gain more experience with NOACs and more clinical trials are published.16-19

Starting or converting to NOAC therapy

In patients who have not been on anticoagulant therapy, any NOAC can be initiated immediately, with no need for parenteral, or “bridge” therapy. This is because of the rapid onset of action of the NOACs.12

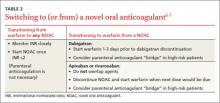

To transition a patient from warfarin to a NOAC, it is necessary to discontinue warfarin therapy completely and closely monitor INR, then initiate NOAC therapy when INR≤2. No parenteral anticoagulation is necessary (TABLE 2).5-7

If it is necessary to transition a patient from a NOAC to warfarin, the protocol depends on the agent. Because dabigatran has no significant impact on prolongation of prothrombin time (PT), it can be overlapped with warfarin. Rivaroxaban and apixaban have a significant impact on PT prolongation, however, and overlapping either agent with warfarin is not recommended.4 Keep in mind that the recommended dosages for the NOACs are not standardized, and can differ drastically depending on the indication for use as well as on patient-specific factors, including renal function, body weight, and age.

Laboratory monitoring is not required

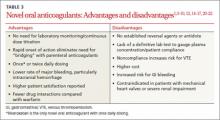

While warfarin has a great deal of interpatient variability and requires frequent lab monitoring, an oft-cited advantage of the NOACs is that they do not require regular monitoring. However, that also has a downside (TABLE 3).1,3-10,12,14-17,20-22 Monitoring INR in patients on warfarin allows physicians to assess patient compliance. And, if a patient on warfarin requires an invasive procedure, coagulation status and bleeding risk can easily be determined. That is not the case with the NOACs.

While some routine laboratory tests may be elevated in a patient taking a NOAC, the degree of elevation does not correlate well with anticoagulant concentration. And, because each NOAC has a different mechanism of action, different measures will be elevated in a patient taking dabigatran vs apixaban or rivaroxaban.4

Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) is the most readily available lab test to assess the presence or absence of dabigatran.4 A normal aPTT indicates that there is little to no dabigatran present.4 But, while an elevated aPTT suggests the presence of dabigatran, it provides little information about how much.4

PT is a useful test to assess coagulation status in patients on either rivaroxaban or apixaban. A normal PT suggests that minimal amounts (or none) of the NOAC are present in the plasma.4 (A direct thrombin inhibitor assay, calibrated to more accurately assess dabigatran concentration, is being developed for clinical use, but is currently available only for research purposes in the United States; a chromogenic antifactor Xa test specific to apixaban and rivaroxaban is also being developed, but is not yet commercially available.4)

What to do when NOAC reversal is required

Patients often need to stop taking an oral anticoagulation in the days leading up to a planned invasive procedure. In an individual with normal renal function who will undergo a procedure with a standard bleeding risk, a NOAC would generally need to be withheld for one to 2 days prior to surgery, given the relatively short half-life. If a patient has acute renal failure or CKD, however, dabigatran may need to be withheld for a prolonged period (3-6 days) in order to safely proceed to surgery.4,23 NOACs may also need to be withheld for 2 to 6 days prior to any surgery with a high risk for bleeding.4

When speed is of the essence

There is no known antidote to aid in the reversal of dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban.4 Because of their relatively short half-lives, withholding the medication and providing supportive care is generally sufficient to ensure adequate hemostasis in cases of mild to moderate bleeding.4 If a patient presents with acute ingestion or an overdose, activated charcoal should be administered if the ingestion has occurred within the past 3 hours.4,24 The lack of a clear-cut reversal strategy can be extremely problematic in cases of trauma or life-threatening bleeding, however. (Fresh frozen plasma has not been shown to be effective at reversing NOACs’ effects.4)

In instances of severe bleeding or the need for urgent surgery, a more aggressive approach may be needed. Hemodialysis can be used to assist in the removal of dabigatran, but not rivaroxaban or apixaban.4 However, evidence suggests that the most effective therapy for patients who need rapid reversal of any NOAC is to administer 75 to 80 units/kg of activated prothrombin complex concentrate (aPCC).4,25-27 Recombinant factor VIIa has shown some promise in reversing the anticoagulant effects of these novel agents, but evidence is insufficient to recommend it as first-line therapy at this time.26, 27

Patients are more satisfied

The most obvious advantage of the NOACs as a group compared with warfarin is the lack of need for laboratory monitoring or continuous dose titration. Reliably stable pharmacokinetics make once or twice daily dosing possible. A rapid onset of action negates the need for bridging therapy with parenteral anticoagulants in patients at high risk of thrombosis. This may improve compliance, as many patients are averse to the use of subcutaneous injections or need extensive education before they can safely self-inject. The incidence of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia may also be decreased if unfractionated heparin and LMWH are used less frequently.

NOACs also appear to improve patient satisfaction.20-22 In one study that included patients with AF on dabigatran or warfarin, satisfaction was higher in those taking dabigatran, particularly among those who did not experience significant GI adverse effects.20 Another study showed improved patient satisfaction with rivaroxaban compared with LMWH following lower extremity joint replacement, which led to significantly higher rates of compliance.22

… but problems and pitfalls remain

In addition to the lack of a readily available and clinically validated reversal agent, the absence of a lab test that reliably measures the concentration of NOACs makes it difficult to determine whether patients are following their prescribed regimen.3,4

Medication compliance must be assessed when considering a transition from warfarin to a NOAC. Switching patients with poor INR control on warfarin to a NOAC should be done only after determining that the poor control is not the result of nonadherence. Because of the NOACs’ shorter half-life, patients who don’t take them regularly may be at higher risk for thromboembolic events.1,12

Cost is a serious consideration. While there are some costs associated with the monitoring warfarin requires, the medication itself has been generic for several decades and can be found on many “$4 lists” at pharmacies nationwide. In contrast, all 3 NOACs are available only as branded drugs, and can cost a patient with limited drug coverage anywhere from $250 to $350 per month28—a serious concern, given that the likelihood of noncompliance increases as out-of-pocket costs rise. This was highlighted in a recent study that found patients were twice as likely to discontinue their cholesterol-lowering medication if 100% of the cost was out of pocket, compared with patients who had no prescription copay.29 From the perspective of the US health care system, however, NOACs have been found to be cost effective compared with warfarin, mostly due to the lack of laboratory monitoring.30-32

Adverse effects. The risk of GI bleeds has been shown to be higher in patients taking rivaroxaban and dabigatran vs warfarin.8,9 Dabigatran has also been associated with a significant risk for dyspepsia.5,8,14 In clinical trials, the reported rate for dyspepsia in patients taking dabigatran was 3% to 11%; subsequent investigations have found the incidence to be far higher (33%).8,14,33

Drug interactions. Warfarin has a large number of drug interactions, of course, but because of its long history, these interactions are well established. NOACs also have a number of drug interactions, but the true clinical impact has not yet been established. All 3 agents are substrates for the P-glycoprotein (P-gp) transport system, so any known inhibitors or inducers of the P-gp system should be used cautiously in patients on NOACs.1,3-7,12 Rivaroxaban and apixaban are also substrates for the CYP3A4 hepatic enzyme system, so any drugs known to inhibit or induce this system require caution, as well.1,3-7,12

Who should not take a NOAC?

NOACs should not be prescribed for patients with mechanical heart valves.34 Dabigatran is the only NOAC to have been studied in this patient population, and the phase II trial was stopped prematurely due to increased risk for both bleeding and stroke in patients on dabigatran compared with warfarin.34

Renal impairment must be considered, as well. Do a baseline assessment of renal function in all patients before transitioning them to a NOAC, and periodic reassessment during therapy. While this is important for patients on rivaroxaban and apixaban, it is essential for those on dabigatran, as 80% of the drug is excreted by the kidneys.1,5,12 NOACs have not been adequately assessed in patients with severe renal dysfunction and should be avoided in this patient population. Caution should be exercised in patients with moderate renal dysfunction, as well.5-10,14-19 Apixaban appears to be the safest NOAC for patients with moderate renal dysfunction, as it has the least renal clearance.1,12

Who should take a NOAC?

No well-established criteria for patient selection for NOACs exist, yet appropriate patient selection is crucial. Evidence suggests that NOAC therapy is best suited to those who:

• are relatively young (<65 years)

• have normal renal function

• have poorly controlled INR with warfarin that is unrelated to noncompliance

• are unable to have regular INR monitoring.

Patients best suited for continued use of warfarin would be those whose INR is well controlled, those who have higher goal INR ranges (eg, because of the presence of mechanical heart valves), patients with significant renal dysfunction, and individuals with a history of peptic ulcer disease or GI bleeding. Warfarin may also be the best option for patients with a history of noncompliance and for uninsured or underinsured patients.

CASE 1 Warfarin and any of the NOACs were all feasible options for Ms. J, but apixaban was deemed to be the safest because of her moderate renal dysfunction. However, after she was told that apixaban has little “real world” clinical data, no effective antidote if bleeding were to occur, and a much higher cost than warfarin, she opted for warfarin therapy, despite the laboratory monitoring required.

CASE 2 Mr. W was excited to learn that there were new alternatives to warfarin; he had taken warfarin for 6 months after his last DVT and had a hard time coming in for INR checks. The patient reported that he had no history of bleeding and was compliant with medications. Rivaroxaban was the best option for Mr. W, as it is the only NOAC with FDA approval for the treatment of acute VTE.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeremy Vandiver, PharmD, BCPS, Swedish Medical Center, Room 3260, 501 East Hampden Avenue, Englewood, CO 80013; jvandiver@uwyo.edu

1. Wittkowsky AK. Novel oral anticoagulants and their role in clinical practice. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:1175-1191.

2. Gums JG. Place of dabigatran in contemporary pharmacotherapy. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:335-337.

3. Ageno W, Gallus AS, Wittkowsky A, et al. Oral anticoagulant therapy: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e44S-e88S.

4. Siegal DM, Crowther MA. Acute management of bleeding in patients on novel oral anticoagulants. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:489-496.

5. Pradaxa [package insert]. Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2010.

6. Xarelto [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2011.

7. Eliquis [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2012.

8. Connolly SJ, Zekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139-1151.

9. Patel MR, Mahaffery KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883-891.

10. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJV, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:981-992.

11. You JJ, Singer DE, Howard P, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e531S-e575S.

12. Camm AJ, Lip GYH, De Caterina R, et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2719-2747.

13. Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e419S-e494S.

14. Schulman S, Kearon C, Kakkar AK, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2342-2352.

15. Bauersachs R, Berkowitz SD, Brenner B, et al. Rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2499-2510.

16. Büller HR, Prins MH, Lensin AW, et al. Oral rivaroxaban for the treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1287-1297.

17. Agnelli A, Buller HR, Cohen A, et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:799-808.

18. Schulman S, Kearon C, Kakkar AK, et al. Extended use of dabigatran, warfarin, or placebo in venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:709-718.

19. Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, et al. Apixaban for extended treatment of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:699-708.

20. Michel J, Mundell D, Boga T, et al. Dabigatran for anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation–Early clinical experience in a hospital population and comparison to trial data. Heart Lung Circ. 2013;22:50-55.

21. Kendoff D, Perka C, Fritsche HM, et al. Oral thromboprophylaxis following total hip or knee replacement: review and multicentre experience with dabigatran etexilate. Open Orthop J. 2011;5:395-399.

22. Rogers BA, Phillip S, Foote J, et al. Is there adequate provision of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis following hip arthroplasty? An audit and international survey. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92:668-672.

23. Healey JS, Eikelboom J, Douketis J, at al. Periprocedural bleeding and thromboembolic events with dabigatran compared with warfarin: results from the randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulation therapy (RE-LY) randomized trial. Circulation. 2012;126:343-348.

24. van Ryn J, Stangier J, Haertter S, et al. Dabigatran etexilate: a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor: interpretation of coagulation assays and reversal of anticoagulant activity. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:1116-1127.

25. Eerenberg ES, Kamphuisen PW, Sijpkens MK, et al. Reversal of rivaroxaban and dabigatran by prothrombin complex concentrate: a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy subjects. Circulation. 2011;124:1573-1579.

26. Marlu R, Hodaj E, Paris A, et al. Effect of nonspecific reversal agents on anticoagulant activity of dabigatran and rivaroxaban. A randomised crossover ex vivo study in healthy volunteers. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108:217-224.

27. Escolar G, Fernandez-Gallego V, Arellano-Rodrigo E, et al. Reversal of apixaban induced alterations of hemostasis by different coagulation factor concentrates: studies in vitro with circulating human blood. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e78696.

28. Drug pricing information. Costco Pharmacy Web site. Available at: http://www2.costco.com/Pharmacy/DrugInformation.aspx?p=1. Accessed December 9, 2013.

29. Schneeweiss S, Patrick AR, Maclure M, et al. Adherence to statin therapy under drug cost sharing in patients with and without myocardial infarction: a population-based natural experiment. Circulation. 2007;115:2128-2135.

30. McKeage K. Dabigatran etexilate: a pharmacoeconomic review of its use in the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. Pharmacoeconomics. 2012;30:841-55.

31. Lee S, Anglade MW, Pham D, et al. Cost–Effectiveness of rivaroxaban compared to warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:845-851.

32. Kamel H, Easton JD, Johnston SC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of apixaban vs warfarin for secondary stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Neurology. 2012;79:1428-1434.

33. Schulman S, Shortt B, Robinson M, et al. Adherence to anticoagulant treatment with dabigatran in a real-world setting. J Thromb Haemost. 2013; 11:1295-1299

34. Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, Brueckmann M, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with mechanical heart valves. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1206-1214.

› Consider novel oral anticoagualants (NOACs) for patients who have normal renal function, are comlpiant with medication regimens, and have no history of peptic ulcer or gastrointestinal bleeding. B

› Avoid overlapping warfarin with rivaroxaban or apixaban when transitioning a patient from one anticoagulant to the other, as both agents prolong prothrombin time. B

› When initiating a NOAC, it is not necessary to overlap with a parenteral anticoagulant. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 Sally J is a 72-year-old Caucasian woman who comes to your clinic after being diagnosed with atrial fibrillation (AF). The patient has a 10-year history of type 2 diabetes; she also has a history of hypertension and chronic kidney disease (CKD), with a baseline creatinine clearance of approximately 40 mL/min. Ms. J tells you she knows people who take warfarin and really dislike it. She asks for your opinion of the new anticoagulants she’s seen advertised on TV, and wonders whether one of them would be right for her.

CASE 2 Bobby W, a 35-year-old African American man, was recently diagnosed with deep vein thrombosis (DVT). This was his second clot in 5 years, and occurred after a long flight home from Europe. The patient explains that he leads a very active lifestyle and doesn’t have the time to come in for the monthly international normalized ratio (INR) checks that warfarin requires. What would you recommend for these patients?

Troubled by warfarin’s narrow therapeutic index, numerous medication and dietary interactions, and need for frequent monitoring, patients requiring long-term oral anticoagulation therapy have been seeking alternatives for years. Finally, they have a choice. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved 3 oral anticoagulants—dabigatran (Pradaxa), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and apixaban (Eliquis)—in less than 4 years. Known as novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs), they are the first such drugs to enter the market in more than 50 years.1,2

While warfarin inhibits a wide range of clotting factors (including II, VII, IX, and X), NOACs work further down the clotting cascade (TABLE 1).1,3-7 Dabigatran, a direct thrombin inhibitor, only inhibits factor IIa.3,5 Rivaroxaban and apixaban directly inhibit factor Xa and indirectly inhibit factor IIa.3,6,7

There are notable advantages to these newer agents, but some disadvantages that must be considered, as well. Appropriate patient selection, guided by a thorough understanding of the benefits and risks of NOACs, is key.

Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation

All 3 NOACs are approved for stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF). The approvals are based on a small number of well-designed trials: RE-LY (dabigatran), ROCKET-AF (rivaroxaban), and ARISTOTLE (apixaban).8-10 Compared with warfarin, dabigatran is the only oral anticoagulant with a lower rate of both hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke.8 Both rivaroxaban and apixaban were found to decrease overall stroke risk relative to warfarin, but the difference was driven by a lower risk for hemorrhagic, not ischemic, stroke.9,10

In these trials, overall rates of major bleeding were similar to that of warfarin.8-10 Patients taking warfarin generally experienced higher rates of intracranial hemorrhage but lower rates of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding than those on NOACs. Relative to warfarin, apixaban was the only NOAC that did not have a higher rate of GI bleeding and the only one with a lower rate of major bleeding.8-10 In addition, apixaban remains the only NOAC found to have a statistically significant decrease in all-cause mortality compared with warfarin.10 Although dabigatran and rivaroxaban were associated with a strong trend towards decreased mortality, both studies were underpowered for this secondary outcome.8,9

Adding NOACs to stroke guidelines. The role of NOACs in the prevention of stroke in patients with nonvalvular AF is beginning to be reflected in newer guidelines. The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP)’s 2012 guidelines recommend dabigatran over warfarin (grade 2B—weak recommendation; moderate quality evidence) unless the patient is well controlled on warfarin.11 The European Society of Cardiology (ESC)’s 2012 guidelines recommend dabigatran, apixaban, and rivaroxaban as broadly preferable to warfarin, while noting that experience with these agents is limited and appropriate patient selection is important.12

Anticoagulation to treat—and prevent—VTE

The standard of care for acute venous thromboembolism (VTE) is to initiate warfarin along with a parenteral anticoagulant, such as unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), or fondaparinux.13 Due to warfarin’s slow onset to peak effect, a parenteral anticoagulant is overlapped for ≥5 days—until warfarin reaches a therapeutic level and can be continued as monotherapy.13 But many patients find subcutaneous delivery of LMWH disagreeable and costly and frequent INR monitoring inconvenient, so the new agents offer notable advantages.

In well-designed studies, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban have all been shown to be noninferior to warfarin in the initial treatment of acute DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE).14-17 All 3 agents were also shown to have lower rates of major bleeding than warfarin. Rivaroxaban and apixaban were also superior to warfarin with regard to bleeding events, and dabigatran was noninferior to warfarin for this outcome.14-17

NOACs help prevent recurrence

All 3 NOACs have been studied for long-term prevention of recurrent VTE after 3 to 18 months of anticoagulation, as well. Dabigatran was found in the RE-MEDY trial to be noninferior to warfarin for the risk of recurrent VTE, and to have lower rates of bleeding.18 In separate trials, all 3 agents were superior to placebo in preventing recurrent VTE. Rates of long-term major bleeding were significantly higher than placebo with rivaroxaban and dabigatran, but not with apixaban.15,18,19

Rivaroxaban is the only NOAC to be FDA approved for the treatment of acute DVT and PE, and the ACCP’s 2012 guidelines list it as a viable alternative to parenteral anticoagulation when initiating treatment for acute VTE.6,13 When treating VTE long term, the guidelines continue to recommend warfarin or LMWH rather than dabigatran or rivaroxaban.13 Recommendations may change in coming years, as physicians gain more experience with NOACs and more clinical trials are published.16-19

Starting or converting to NOAC therapy

In patients who have not been on anticoagulant therapy, any NOAC can be initiated immediately, with no need for parenteral, or “bridge” therapy. This is because of the rapid onset of action of the NOACs.12

To transition a patient from warfarin to a NOAC, it is necessary to discontinue warfarin therapy completely and closely monitor INR, then initiate NOAC therapy when INR≤2. No parenteral anticoagulation is necessary (TABLE 2).5-7

If it is necessary to transition a patient from a NOAC to warfarin, the protocol depends on the agent. Because dabigatran has no significant impact on prolongation of prothrombin time (PT), it can be overlapped with warfarin. Rivaroxaban and apixaban have a significant impact on PT prolongation, however, and overlapping either agent with warfarin is not recommended.4 Keep in mind that the recommended dosages for the NOACs are not standardized, and can differ drastically depending on the indication for use as well as on patient-specific factors, including renal function, body weight, and age.

Laboratory monitoring is not required

While warfarin has a great deal of interpatient variability and requires frequent lab monitoring, an oft-cited advantage of the NOACs is that they do not require regular monitoring. However, that also has a downside (TABLE 3).1,3-10,12,14-17,20-22 Monitoring INR in patients on warfarin allows physicians to assess patient compliance. And, if a patient on warfarin requires an invasive procedure, coagulation status and bleeding risk can easily be determined. That is not the case with the NOACs.

While some routine laboratory tests may be elevated in a patient taking a NOAC, the degree of elevation does not correlate well with anticoagulant concentration. And, because each NOAC has a different mechanism of action, different measures will be elevated in a patient taking dabigatran vs apixaban or rivaroxaban.4

Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) is the most readily available lab test to assess the presence or absence of dabigatran.4 A normal aPTT indicates that there is little to no dabigatran present.4 But, while an elevated aPTT suggests the presence of dabigatran, it provides little information about how much.4

PT is a useful test to assess coagulation status in patients on either rivaroxaban or apixaban. A normal PT suggests that minimal amounts (or none) of the NOAC are present in the plasma.4 (A direct thrombin inhibitor assay, calibrated to more accurately assess dabigatran concentration, is being developed for clinical use, but is currently available only for research purposes in the United States; a chromogenic antifactor Xa test specific to apixaban and rivaroxaban is also being developed, but is not yet commercially available.4)

What to do when NOAC reversal is required

Patients often need to stop taking an oral anticoagulation in the days leading up to a planned invasive procedure. In an individual with normal renal function who will undergo a procedure with a standard bleeding risk, a NOAC would generally need to be withheld for one to 2 days prior to surgery, given the relatively short half-life. If a patient has acute renal failure or CKD, however, dabigatran may need to be withheld for a prolonged period (3-6 days) in order to safely proceed to surgery.4,23 NOACs may also need to be withheld for 2 to 6 days prior to any surgery with a high risk for bleeding.4

When speed is of the essence

There is no known antidote to aid in the reversal of dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban.4 Because of their relatively short half-lives, withholding the medication and providing supportive care is generally sufficient to ensure adequate hemostasis in cases of mild to moderate bleeding.4 If a patient presents with acute ingestion or an overdose, activated charcoal should be administered if the ingestion has occurred within the past 3 hours.4,24 The lack of a clear-cut reversal strategy can be extremely problematic in cases of trauma or life-threatening bleeding, however. (Fresh frozen plasma has not been shown to be effective at reversing NOACs’ effects.4)

In instances of severe bleeding or the need for urgent surgery, a more aggressive approach may be needed. Hemodialysis can be used to assist in the removal of dabigatran, but not rivaroxaban or apixaban.4 However, evidence suggests that the most effective therapy for patients who need rapid reversal of any NOAC is to administer 75 to 80 units/kg of activated prothrombin complex concentrate (aPCC).4,25-27 Recombinant factor VIIa has shown some promise in reversing the anticoagulant effects of these novel agents, but evidence is insufficient to recommend it as first-line therapy at this time.26, 27

Patients are more satisfied

The most obvious advantage of the NOACs as a group compared with warfarin is the lack of need for laboratory monitoring or continuous dose titration. Reliably stable pharmacokinetics make once or twice daily dosing possible. A rapid onset of action negates the need for bridging therapy with parenteral anticoagulants in patients at high risk of thrombosis. This may improve compliance, as many patients are averse to the use of subcutaneous injections or need extensive education before they can safely self-inject. The incidence of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia may also be decreased if unfractionated heparin and LMWH are used less frequently.

NOACs also appear to improve patient satisfaction.20-22 In one study that included patients with AF on dabigatran or warfarin, satisfaction was higher in those taking dabigatran, particularly among those who did not experience significant GI adverse effects.20 Another study showed improved patient satisfaction with rivaroxaban compared with LMWH following lower extremity joint replacement, which led to significantly higher rates of compliance.22

… but problems and pitfalls remain

In addition to the lack of a readily available and clinically validated reversal agent, the absence of a lab test that reliably measures the concentration of NOACs makes it difficult to determine whether patients are following their prescribed regimen.3,4

Medication compliance must be assessed when considering a transition from warfarin to a NOAC. Switching patients with poor INR control on warfarin to a NOAC should be done only after determining that the poor control is not the result of nonadherence. Because of the NOACs’ shorter half-life, patients who don’t take them regularly may be at higher risk for thromboembolic events.1,12

Cost is a serious consideration. While there are some costs associated with the monitoring warfarin requires, the medication itself has been generic for several decades and can be found on many “$4 lists” at pharmacies nationwide. In contrast, all 3 NOACs are available only as branded drugs, and can cost a patient with limited drug coverage anywhere from $250 to $350 per month28—a serious concern, given that the likelihood of noncompliance increases as out-of-pocket costs rise. This was highlighted in a recent study that found patients were twice as likely to discontinue their cholesterol-lowering medication if 100% of the cost was out of pocket, compared with patients who had no prescription copay.29 From the perspective of the US health care system, however, NOACs have been found to be cost effective compared with warfarin, mostly due to the lack of laboratory monitoring.30-32

Adverse effects. The risk of GI bleeds has been shown to be higher in patients taking rivaroxaban and dabigatran vs warfarin.8,9 Dabigatran has also been associated with a significant risk for dyspepsia.5,8,14 In clinical trials, the reported rate for dyspepsia in patients taking dabigatran was 3% to 11%; subsequent investigations have found the incidence to be far higher (33%).8,14,33

Drug interactions. Warfarin has a large number of drug interactions, of course, but because of its long history, these interactions are well established. NOACs also have a number of drug interactions, but the true clinical impact has not yet been established. All 3 agents are substrates for the P-glycoprotein (P-gp) transport system, so any known inhibitors or inducers of the P-gp system should be used cautiously in patients on NOACs.1,3-7,12 Rivaroxaban and apixaban are also substrates for the CYP3A4 hepatic enzyme system, so any drugs known to inhibit or induce this system require caution, as well.1,3-7,12

Who should not take a NOAC?

NOACs should not be prescribed for patients with mechanical heart valves.34 Dabigatran is the only NOAC to have been studied in this patient population, and the phase II trial was stopped prematurely due to increased risk for both bleeding and stroke in patients on dabigatran compared with warfarin.34

Renal impairment must be considered, as well. Do a baseline assessment of renal function in all patients before transitioning them to a NOAC, and periodic reassessment during therapy. While this is important for patients on rivaroxaban and apixaban, it is essential for those on dabigatran, as 80% of the drug is excreted by the kidneys.1,5,12 NOACs have not been adequately assessed in patients with severe renal dysfunction and should be avoided in this patient population. Caution should be exercised in patients with moderate renal dysfunction, as well.5-10,14-19 Apixaban appears to be the safest NOAC for patients with moderate renal dysfunction, as it has the least renal clearance.1,12

Who should take a NOAC?

No well-established criteria for patient selection for NOACs exist, yet appropriate patient selection is crucial. Evidence suggests that NOAC therapy is best suited to those who:

• are relatively young (<65 years)

• have normal renal function

• have poorly controlled INR with warfarin that is unrelated to noncompliance

• are unable to have regular INR monitoring.

Patients best suited for continued use of warfarin would be those whose INR is well controlled, those who have higher goal INR ranges (eg, because of the presence of mechanical heart valves), patients with significant renal dysfunction, and individuals with a history of peptic ulcer disease or GI bleeding. Warfarin may also be the best option for patients with a history of noncompliance and for uninsured or underinsured patients.

CASE 1 Warfarin and any of the NOACs were all feasible options for Ms. J, but apixaban was deemed to be the safest because of her moderate renal dysfunction. However, after she was told that apixaban has little “real world” clinical data, no effective antidote if bleeding were to occur, and a much higher cost than warfarin, she opted for warfarin therapy, despite the laboratory monitoring required.

CASE 2 Mr. W was excited to learn that there were new alternatives to warfarin; he had taken warfarin for 6 months after his last DVT and had a hard time coming in for INR checks. The patient reported that he had no history of bleeding and was compliant with medications. Rivaroxaban was the best option for Mr. W, as it is the only NOAC with FDA approval for the treatment of acute VTE.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeremy Vandiver, PharmD, BCPS, Swedish Medical Center, Room 3260, 501 East Hampden Avenue, Englewood, CO 80013; jvandiver@uwyo.edu

› Consider novel oral anticoagualants (NOACs) for patients who have normal renal function, are comlpiant with medication regimens, and have no history of peptic ulcer or gastrointestinal bleeding. B

› Avoid overlapping warfarin with rivaroxaban or apixaban when transitioning a patient from one anticoagulant to the other, as both agents prolong prothrombin time. B

› When initiating a NOAC, it is not necessary to overlap with a parenteral anticoagulant. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 Sally J is a 72-year-old Caucasian woman who comes to your clinic after being diagnosed with atrial fibrillation (AF). The patient has a 10-year history of type 2 diabetes; she also has a history of hypertension and chronic kidney disease (CKD), with a baseline creatinine clearance of approximately 40 mL/min. Ms. J tells you she knows people who take warfarin and really dislike it. She asks for your opinion of the new anticoagulants she’s seen advertised on TV, and wonders whether one of them would be right for her.

CASE 2 Bobby W, a 35-year-old African American man, was recently diagnosed with deep vein thrombosis (DVT). This was his second clot in 5 years, and occurred after a long flight home from Europe. The patient explains that he leads a very active lifestyle and doesn’t have the time to come in for the monthly international normalized ratio (INR) checks that warfarin requires. What would you recommend for these patients?

Troubled by warfarin’s narrow therapeutic index, numerous medication and dietary interactions, and need for frequent monitoring, patients requiring long-term oral anticoagulation therapy have been seeking alternatives for years. Finally, they have a choice. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved 3 oral anticoagulants—dabigatran (Pradaxa), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and apixaban (Eliquis)—in less than 4 years. Known as novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs), they are the first such drugs to enter the market in more than 50 years.1,2

While warfarin inhibits a wide range of clotting factors (including II, VII, IX, and X), NOACs work further down the clotting cascade (TABLE 1).1,3-7 Dabigatran, a direct thrombin inhibitor, only inhibits factor IIa.3,5 Rivaroxaban and apixaban directly inhibit factor Xa and indirectly inhibit factor IIa.3,6,7

There are notable advantages to these newer agents, but some disadvantages that must be considered, as well. Appropriate patient selection, guided by a thorough understanding of the benefits and risks of NOACs, is key.

Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation

All 3 NOACs are approved for stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF). The approvals are based on a small number of well-designed trials: RE-LY (dabigatran), ROCKET-AF (rivaroxaban), and ARISTOTLE (apixaban).8-10 Compared with warfarin, dabigatran is the only oral anticoagulant with a lower rate of both hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke.8 Both rivaroxaban and apixaban were found to decrease overall stroke risk relative to warfarin, but the difference was driven by a lower risk for hemorrhagic, not ischemic, stroke.9,10

In these trials, overall rates of major bleeding were similar to that of warfarin.8-10 Patients taking warfarin generally experienced higher rates of intracranial hemorrhage but lower rates of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding than those on NOACs. Relative to warfarin, apixaban was the only NOAC that did not have a higher rate of GI bleeding and the only one with a lower rate of major bleeding.8-10 In addition, apixaban remains the only NOAC found to have a statistically significant decrease in all-cause mortality compared with warfarin.10 Although dabigatran and rivaroxaban were associated with a strong trend towards decreased mortality, both studies were underpowered for this secondary outcome.8,9

Adding NOACs to stroke guidelines. The role of NOACs in the prevention of stroke in patients with nonvalvular AF is beginning to be reflected in newer guidelines. The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP)’s 2012 guidelines recommend dabigatran over warfarin (grade 2B—weak recommendation; moderate quality evidence) unless the patient is well controlled on warfarin.11 The European Society of Cardiology (ESC)’s 2012 guidelines recommend dabigatran, apixaban, and rivaroxaban as broadly preferable to warfarin, while noting that experience with these agents is limited and appropriate patient selection is important.12

Anticoagulation to treat—and prevent—VTE

The standard of care for acute venous thromboembolism (VTE) is to initiate warfarin along with a parenteral anticoagulant, such as unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), or fondaparinux.13 Due to warfarin’s slow onset to peak effect, a parenteral anticoagulant is overlapped for ≥5 days—until warfarin reaches a therapeutic level and can be continued as monotherapy.13 But many patients find subcutaneous delivery of LMWH disagreeable and costly and frequent INR monitoring inconvenient, so the new agents offer notable advantages.

In well-designed studies, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban have all been shown to be noninferior to warfarin in the initial treatment of acute DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE).14-17 All 3 agents were also shown to have lower rates of major bleeding than warfarin. Rivaroxaban and apixaban were also superior to warfarin with regard to bleeding events, and dabigatran was noninferior to warfarin for this outcome.14-17

NOACs help prevent recurrence

All 3 NOACs have been studied for long-term prevention of recurrent VTE after 3 to 18 months of anticoagulation, as well. Dabigatran was found in the RE-MEDY trial to be noninferior to warfarin for the risk of recurrent VTE, and to have lower rates of bleeding.18 In separate trials, all 3 agents were superior to placebo in preventing recurrent VTE. Rates of long-term major bleeding were significantly higher than placebo with rivaroxaban and dabigatran, but not with apixaban.15,18,19

Rivaroxaban is the only NOAC to be FDA approved for the treatment of acute DVT and PE, and the ACCP’s 2012 guidelines list it as a viable alternative to parenteral anticoagulation when initiating treatment for acute VTE.6,13 When treating VTE long term, the guidelines continue to recommend warfarin or LMWH rather than dabigatran or rivaroxaban.13 Recommendations may change in coming years, as physicians gain more experience with NOACs and more clinical trials are published.16-19

Starting or converting to NOAC therapy

In patients who have not been on anticoagulant therapy, any NOAC can be initiated immediately, with no need for parenteral, or “bridge” therapy. This is because of the rapid onset of action of the NOACs.12

To transition a patient from warfarin to a NOAC, it is necessary to discontinue warfarin therapy completely and closely monitor INR, then initiate NOAC therapy when INR≤2. No parenteral anticoagulation is necessary (TABLE 2).5-7

If it is necessary to transition a patient from a NOAC to warfarin, the protocol depends on the agent. Because dabigatran has no significant impact on prolongation of prothrombin time (PT), it can be overlapped with warfarin. Rivaroxaban and apixaban have a significant impact on PT prolongation, however, and overlapping either agent with warfarin is not recommended.4 Keep in mind that the recommended dosages for the NOACs are not standardized, and can differ drastically depending on the indication for use as well as on patient-specific factors, including renal function, body weight, and age.

Laboratory monitoring is not required

While warfarin has a great deal of interpatient variability and requires frequent lab monitoring, an oft-cited advantage of the NOACs is that they do not require regular monitoring. However, that also has a downside (TABLE 3).1,3-10,12,14-17,20-22 Monitoring INR in patients on warfarin allows physicians to assess patient compliance. And, if a patient on warfarin requires an invasive procedure, coagulation status and bleeding risk can easily be determined. That is not the case with the NOACs.

While some routine laboratory tests may be elevated in a patient taking a NOAC, the degree of elevation does not correlate well with anticoagulant concentration. And, because each NOAC has a different mechanism of action, different measures will be elevated in a patient taking dabigatran vs apixaban or rivaroxaban.4

Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) is the most readily available lab test to assess the presence or absence of dabigatran.4 A normal aPTT indicates that there is little to no dabigatran present.4 But, while an elevated aPTT suggests the presence of dabigatran, it provides little information about how much.4

PT is a useful test to assess coagulation status in patients on either rivaroxaban or apixaban. A normal PT suggests that minimal amounts (or none) of the NOAC are present in the plasma.4 (A direct thrombin inhibitor assay, calibrated to more accurately assess dabigatran concentration, is being developed for clinical use, but is currently available only for research purposes in the United States; a chromogenic antifactor Xa test specific to apixaban and rivaroxaban is also being developed, but is not yet commercially available.4)

What to do when NOAC reversal is required

Patients often need to stop taking an oral anticoagulation in the days leading up to a planned invasive procedure. In an individual with normal renal function who will undergo a procedure with a standard bleeding risk, a NOAC would generally need to be withheld for one to 2 days prior to surgery, given the relatively short half-life. If a patient has acute renal failure or CKD, however, dabigatran may need to be withheld for a prolonged period (3-6 days) in order to safely proceed to surgery.4,23 NOACs may also need to be withheld for 2 to 6 days prior to any surgery with a high risk for bleeding.4

When speed is of the essence

There is no known antidote to aid in the reversal of dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban.4 Because of their relatively short half-lives, withholding the medication and providing supportive care is generally sufficient to ensure adequate hemostasis in cases of mild to moderate bleeding.4 If a patient presents with acute ingestion or an overdose, activated charcoal should be administered if the ingestion has occurred within the past 3 hours.4,24 The lack of a clear-cut reversal strategy can be extremely problematic in cases of trauma or life-threatening bleeding, however. (Fresh frozen plasma has not been shown to be effective at reversing NOACs’ effects.4)

In instances of severe bleeding or the need for urgent surgery, a more aggressive approach may be needed. Hemodialysis can be used to assist in the removal of dabigatran, but not rivaroxaban or apixaban.4 However, evidence suggests that the most effective therapy for patients who need rapid reversal of any NOAC is to administer 75 to 80 units/kg of activated prothrombin complex concentrate (aPCC).4,25-27 Recombinant factor VIIa has shown some promise in reversing the anticoagulant effects of these novel agents, but evidence is insufficient to recommend it as first-line therapy at this time.26, 27

Patients are more satisfied

The most obvious advantage of the NOACs as a group compared with warfarin is the lack of need for laboratory monitoring or continuous dose titration. Reliably stable pharmacokinetics make once or twice daily dosing possible. A rapid onset of action negates the need for bridging therapy with parenteral anticoagulants in patients at high risk of thrombosis. This may improve compliance, as many patients are averse to the use of subcutaneous injections or need extensive education before they can safely self-inject. The incidence of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia may also be decreased if unfractionated heparin and LMWH are used less frequently.

NOACs also appear to improve patient satisfaction.20-22 In one study that included patients with AF on dabigatran or warfarin, satisfaction was higher in those taking dabigatran, particularly among those who did not experience significant GI adverse effects.20 Another study showed improved patient satisfaction with rivaroxaban compared with LMWH following lower extremity joint replacement, which led to significantly higher rates of compliance.22

… but problems and pitfalls remain

In addition to the lack of a readily available and clinically validated reversal agent, the absence of a lab test that reliably measures the concentration of NOACs makes it difficult to determine whether patients are following their prescribed regimen.3,4

Medication compliance must be assessed when considering a transition from warfarin to a NOAC. Switching patients with poor INR control on warfarin to a NOAC should be done only after determining that the poor control is not the result of nonadherence. Because of the NOACs’ shorter half-life, patients who don’t take them regularly may be at higher risk for thromboembolic events.1,12

Cost is a serious consideration. While there are some costs associated with the monitoring warfarin requires, the medication itself has been generic for several decades and can be found on many “$4 lists” at pharmacies nationwide. In contrast, all 3 NOACs are available only as branded drugs, and can cost a patient with limited drug coverage anywhere from $250 to $350 per month28—a serious concern, given that the likelihood of noncompliance increases as out-of-pocket costs rise. This was highlighted in a recent study that found patients were twice as likely to discontinue their cholesterol-lowering medication if 100% of the cost was out of pocket, compared with patients who had no prescription copay.29 From the perspective of the US health care system, however, NOACs have been found to be cost effective compared with warfarin, mostly due to the lack of laboratory monitoring.30-32

Adverse effects. The risk of GI bleeds has been shown to be higher in patients taking rivaroxaban and dabigatran vs warfarin.8,9 Dabigatran has also been associated with a significant risk for dyspepsia.5,8,14 In clinical trials, the reported rate for dyspepsia in patients taking dabigatran was 3% to 11%; subsequent investigations have found the incidence to be far higher (33%).8,14,33

Drug interactions. Warfarin has a large number of drug interactions, of course, but because of its long history, these interactions are well established. NOACs also have a number of drug interactions, but the true clinical impact has not yet been established. All 3 agents are substrates for the P-glycoprotein (P-gp) transport system, so any known inhibitors or inducers of the P-gp system should be used cautiously in patients on NOACs.1,3-7,12 Rivaroxaban and apixaban are also substrates for the CYP3A4 hepatic enzyme system, so any drugs known to inhibit or induce this system require caution, as well.1,3-7,12

Who should not take a NOAC?

NOACs should not be prescribed for patients with mechanical heart valves.34 Dabigatran is the only NOAC to have been studied in this patient population, and the phase II trial was stopped prematurely due to increased risk for both bleeding and stroke in patients on dabigatran compared with warfarin.34

Renal impairment must be considered, as well. Do a baseline assessment of renal function in all patients before transitioning them to a NOAC, and periodic reassessment during therapy. While this is important for patients on rivaroxaban and apixaban, it is essential for those on dabigatran, as 80% of the drug is excreted by the kidneys.1,5,12 NOACs have not been adequately assessed in patients with severe renal dysfunction and should be avoided in this patient population. Caution should be exercised in patients with moderate renal dysfunction, as well.5-10,14-19 Apixaban appears to be the safest NOAC for patients with moderate renal dysfunction, as it has the least renal clearance.1,12

Who should take a NOAC?

No well-established criteria for patient selection for NOACs exist, yet appropriate patient selection is crucial. Evidence suggests that NOAC therapy is best suited to those who:

• are relatively young (<65 years)

• have normal renal function

• have poorly controlled INR with warfarin that is unrelated to noncompliance

• are unable to have regular INR monitoring.

Patients best suited for continued use of warfarin would be those whose INR is well controlled, those who have higher goal INR ranges (eg, because of the presence of mechanical heart valves), patients with significant renal dysfunction, and individuals with a history of peptic ulcer disease or GI bleeding. Warfarin may also be the best option for patients with a history of noncompliance and for uninsured or underinsured patients.

CASE 1 Warfarin and any of the NOACs were all feasible options for Ms. J, but apixaban was deemed to be the safest because of her moderate renal dysfunction. However, after she was told that apixaban has little “real world” clinical data, no effective antidote if bleeding were to occur, and a much higher cost than warfarin, she opted for warfarin therapy, despite the laboratory monitoring required.

CASE 2 Mr. W was excited to learn that there were new alternatives to warfarin; he had taken warfarin for 6 months after his last DVT and had a hard time coming in for INR checks. The patient reported that he had no history of bleeding and was compliant with medications. Rivaroxaban was the best option for Mr. W, as it is the only NOAC with FDA approval for the treatment of acute VTE.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeremy Vandiver, PharmD, BCPS, Swedish Medical Center, Room 3260, 501 East Hampden Avenue, Englewood, CO 80013; jvandiver@uwyo.edu

1. Wittkowsky AK. Novel oral anticoagulants and their role in clinical practice. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:1175-1191.

2. Gums JG. Place of dabigatran in contemporary pharmacotherapy. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:335-337.

3. Ageno W, Gallus AS, Wittkowsky A, et al. Oral anticoagulant therapy: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e44S-e88S.

4. Siegal DM, Crowther MA. Acute management of bleeding in patients on novel oral anticoagulants. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:489-496.

5. Pradaxa [package insert]. Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2010.

6. Xarelto [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2011.

7. Eliquis [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2012.

8. Connolly SJ, Zekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139-1151.

9. Patel MR, Mahaffery KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883-891.

10. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJV, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:981-992.

11. You JJ, Singer DE, Howard P, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e531S-e575S.

12. Camm AJ, Lip GYH, De Caterina R, et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2719-2747.

13. Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e419S-e494S.

14. Schulman S, Kearon C, Kakkar AK, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2342-2352.

15. Bauersachs R, Berkowitz SD, Brenner B, et al. Rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2499-2510.

16. Büller HR, Prins MH, Lensin AW, et al. Oral rivaroxaban for the treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1287-1297.

17. Agnelli A, Buller HR, Cohen A, et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:799-808.

18. Schulman S, Kearon C, Kakkar AK, et al. Extended use of dabigatran, warfarin, or placebo in venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:709-718.

19. Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, et al. Apixaban for extended treatment of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:699-708.

20. Michel J, Mundell D, Boga T, et al. Dabigatran for anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation–Early clinical experience in a hospital population and comparison to trial data. Heart Lung Circ. 2013;22:50-55.

21. Kendoff D, Perka C, Fritsche HM, et al. Oral thromboprophylaxis following total hip or knee replacement: review and multicentre experience with dabigatran etexilate. Open Orthop J. 2011;5:395-399.

22. Rogers BA, Phillip S, Foote J, et al. Is there adequate provision of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis following hip arthroplasty? An audit and international survey. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92:668-672.

23. Healey JS, Eikelboom J, Douketis J, at al. Periprocedural bleeding and thromboembolic events with dabigatran compared with warfarin: results from the randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulation therapy (RE-LY) randomized trial. Circulation. 2012;126:343-348.

24. van Ryn J, Stangier J, Haertter S, et al. Dabigatran etexilate: a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor: interpretation of coagulation assays and reversal of anticoagulant activity. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:1116-1127.

25. Eerenberg ES, Kamphuisen PW, Sijpkens MK, et al. Reversal of rivaroxaban and dabigatran by prothrombin complex concentrate: a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy subjects. Circulation. 2011;124:1573-1579.

26. Marlu R, Hodaj E, Paris A, et al. Effect of nonspecific reversal agents on anticoagulant activity of dabigatran and rivaroxaban. A randomised crossover ex vivo study in healthy volunteers. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108:217-224.

27. Escolar G, Fernandez-Gallego V, Arellano-Rodrigo E, et al. Reversal of apixaban induced alterations of hemostasis by different coagulation factor concentrates: studies in vitro with circulating human blood. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e78696.

28. Drug pricing information. Costco Pharmacy Web site. Available at: http://www2.costco.com/Pharmacy/DrugInformation.aspx?p=1. Accessed December 9, 2013.

29. Schneeweiss S, Patrick AR, Maclure M, et al. Adherence to statin therapy under drug cost sharing in patients with and without myocardial infarction: a population-based natural experiment. Circulation. 2007;115:2128-2135.

30. McKeage K. Dabigatran etexilate: a pharmacoeconomic review of its use in the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. Pharmacoeconomics. 2012;30:841-55.

31. Lee S, Anglade MW, Pham D, et al. Cost–Effectiveness of rivaroxaban compared to warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:845-851.

32. Kamel H, Easton JD, Johnston SC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of apixaban vs warfarin for secondary stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Neurology. 2012;79:1428-1434.

33. Schulman S, Shortt B, Robinson M, et al. Adherence to anticoagulant treatment with dabigatran in a real-world setting. J Thromb Haemost. 2013; 11:1295-1299

34. Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, Brueckmann M, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with mechanical heart valves. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1206-1214.

1. Wittkowsky AK. Novel oral anticoagulants and their role in clinical practice. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:1175-1191.

2. Gums JG. Place of dabigatran in contemporary pharmacotherapy. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:335-337.

3. Ageno W, Gallus AS, Wittkowsky A, et al. Oral anticoagulant therapy: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e44S-e88S.

4. Siegal DM, Crowther MA. Acute management of bleeding in patients on novel oral anticoagulants. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:489-496.

5. Pradaxa [package insert]. Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2010.

6. Xarelto [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2011.

7. Eliquis [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2012.

8. Connolly SJ, Zekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139-1151.

9. Patel MR, Mahaffery KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883-891.

10. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJV, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:981-992.

11. You JJ, Singer DE, Howard P, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e531S-e575S.

12. Camm AJ, Lip GYH, De Caterina R, et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2719-2747.

13. Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e419S-e494S.

14. Schulman S, Kearon C, Kakkar AK, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2342-2352.

15. Bauersachs R, Berkowitz SD, Brenner B, et al. Rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2499-2510.

16. Büller HR, Prins MH, Lensin AW, et al. Oral rivaroxaban for the treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1287-1297.

17. Agnelli A, Buller HR, Cohen A, et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:799-808.

18. Schulman S, Kearon C, Kakkar AK, et al. Extended use of dabigatran, warfarin, or placebo in venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:709-718.

19. Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, et al. Apixaban for extended treatment of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:699-708.

20. Michel J, Mundell D, Boga T, et al. Dabigatran for anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation–Early clinical experience in a hospital population and comparison to trial data. Heart Lung Circ. 2013;22:50-55.

21. Kendoff D, Perka C, Fritsche HM, et al. Oral thromboprophylaxis following total hip or knee replacement: review and multicentre experience with dabigatran etexilate. Open Orthop J. 2011;5:395-399.

22. Rogers BA, Phillip S, Foote J, et al. Is there adequate provision of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis following hip arthroplasty? An audit and international survey. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92:668-672.

23. Healey JS, Eikelboom J, Douketis J, at al. Periprocedural bleeding and thromboembolic events with dabigatran compared with warfarin: results from the randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulation therapy (RE-LY) randomized trial. Circulation. 2012;126:343-348.

24. van Ryn J, Stangier J, Haertter S, et al. Dabigatran etexilate: a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor: interpretation of coagulation assays and reversal of anticoagulant activity. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:1116-1127.

25. Eerenberg ES, Kamphuisen PW, Sijpkens MK, et al. Reversal of rivaroxaban and dabigatran by prothrombin complex concentrate: a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy subjects. Circulation. 2011;124:1573-1579.

26. Marlu R, Hodaj E, Paris A, et al. Effect of nonspecific reversal agents on anticoagulant activity of dabigatran and rivaroxaban. A randomised crossover ex vivo study in healthy volunteers. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108:217-224.

27. Escolar G, Fernandez-Gallego V, Arellano-Rodrigo E, et al. Reversal of apixaban induced alterations of hemostasis by different coagulation factor concentrates: studies in vitro with circulating human blood. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e78696.

28. Drug pricing information. Costco Pharmacy Web site. Available at: http://www2.costco.com/Pharmacy/DrugInformation.aspx?p=1. Accessed December 9, 2013.

29. Schneeweiss S, Patrick AR, Maclure M, et al. Adherence to statin therapy under drug cost sharing in patients with and without myocardial infarction: a population-based natural experiment. Circulation. 2007;115:2128-2135.

30. McKeage K. Dabigatran etexilate: a pharmacoeconomic review of its use in the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. Pharmacoeconomics. 2012;30:841-55.

31. Lee S, Anglade MW, Pham D, et al. Cost–Effectiveness of rivaroxaban compared to warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:845-851.

32. Kamel H, Easton JD, Johnston SC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of apixaban vs warfarin for secondary stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Neurology. 2012;79:1428-1434.

33. Schulman S, Shortt B, Robinson M, et al. Adherence to anticoagulant treatment with dabigatran in a real-world setting. J Thromb Haemost. 2013; 11:1295-1299

34. Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, Brueckmann M, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with mechanical heart valves. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1206-1214.