User login

A novel physical rehabilitation program for patients with advanced heart failure that aimed to improve their ability to exercise before focusing on endurance was successful in a randomized trial in ways that seem to have eluded some earlier exercise-training studies in the setting of HF.

The often-frail patients following the training regimen, initiated before discharge from hospitalization for acute decompensation, worked on capabilities such as mobility, balance, and strength deemed necessary if exercises meant to build exercise capacity were to succeed.

A huge percentage stayed with the 12-week program, which featured personalized, one-on-one training from a physical therapist. The patients benefited, with improvements in balance, walking ability, and strength, which were followed by significant gains in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and measures of physical functioning, frailty, and quality of life. The patients then continued elements of the program at home out to 6 months.

At that time, death and rehospitalizations did not differ between those assigned to the regimen and similar patients who had not participated in the program, although the trial wasn’t powered for clinical events.

The rehab strategy seemed to work across a wide range of patient subgroups. In particular, there was evidence that the benefits were more pronounced in patients with HF and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) than in those with HF and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), observed Dalane W. Kitzman, MD, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Dr. Kitzman presented results from the REHAB-HF (Rehabilitation Therapy in Older Acute Heart Failure Patients) trial at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and is lead author on its same-day publication in the New England Journal of Medicine.

An earlier pilot program unexpectedly showed that such patients recently hospitalized with HF “have significant impairments in mobility and balance,” he explained. If so, “it would be hazardous to subject them to traditional endurance training, such as walking-based treadmill or even bicycle.”

The unusual program, said Dr. Kitzman, looks to those issues before engaging the patients in endurance exercise by addressing mobility, balance, and basic strength – enough to repeatedly stand up from a sitting position, for example. “If you’re not able to stand with confidence, then you’re not able to walk on a treadmill.”

This model of exercise rehab “is used in geriatrics research, and enables them to safely increase endurance. It’s well known from geriatric studies that if you go directly to endurance in these, frail, older patients, you have little improvement and often have injuries and falls,” he added.

Guidance from telemedicine?

The functional outcomes examined in REHAB-HF “are the ones that matter to patients the most,” observed Eileen M. Handberg, PhD, of Shands Hospital at the University of Florida, Gainesville, at a presentation on the trial for the media.

“This is about being able to get out of a chair without assistance, not falling, walking farther, and feeling better as opposed to the more traditional outcome measure that has been used in cardiac rehab trials, which has been the exercise treadmill test – which most patients don’t have the capacity to do very well anyway,” said Dr. Handberg, who is not a part of REHAB-HF.

“This opens up rehab, potentially, to the more sick, who also need a better quality of life,” she said.

However, many patients invited to participate in the trial could not because they lived too far from the program, Dr. Handberg observed. “It would be nice to see if the lessons from COVID-19 might apply to this population” by making participation possible remotely, “perhaps using family members as rehab assistance,” she said.

“I was really very impressed that you had 83% adherence to a home exercise 6 months down the road, which far eclipses what we had in HF-ACTION,” said Vera Bittner, MD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, as the invited discussant following Dr. Kitzman’s formal presentation of the trial. “And it certainly eclipses what we see in the typical cardiac rehab program.”

Both Dr. Bittner and Dr. Kitzman participated in HF-ACTION, a randomized exercise-training trial for patients with chronic, stable HFrEF who were all-around less sick than those in REHAB-HF.

Four functional domains

Historically, HF exercise or rehab trials have excluded patients hospitalized with acute decompensation, and third-party reimbursement often has not covered such programs because of a lack of supporting evidence and a supposed potential for harm, Dr. Kitzman said.

Entry to REHAB-HF required the patients to be fit enough to walk 4 meters, with or without a walker or other assistant device, and to have been in the hospital for at least 24 hours with a primary diagnosis of acute decompensated HF.

The intervention relied on exercises aimed at improving the four functional domains of strength, balance, mobility, and – when those three were sufficiently developed – endurance, Dr. Kitzman and associates wrote in their published report.

“The intervention was initiated in the hospital when feasible and was subsequently transitioned to an outpatient facility as soon as possible after discharge,” they wrote. Afterward, “a key goal of the intervention during the first 3 months [the outpatient phase] was to prepare the patient to transition to the independent maintenance phase (months 4-6).”

The study’s control patients “received frequent calls from study staff to try to approximate the increased attention received by the intervention group,” Dr. Kitzman said in an interview. “They were allowed to receive all usual care as ordered by their treating physicians. This included, if ordered, standard physical therapy or cardiac rehabilitation” in 43% of the control cohort. Of the trial’s 349 patients, those assigned to the intervention scored significantly higher on the three-component Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) at 12 weeks than those assigned to a usual care approach that included, for some, more conventional cardiac rehabilitation (8.3 vs. 6.9; P < .001).

The SPPB, validated in trials as a proxy for clinical outcomes includes tests of balance while standing, gait speed during a 4-minute walk, and strength. The latter is the test that measures time needed to rise from a chair five times.

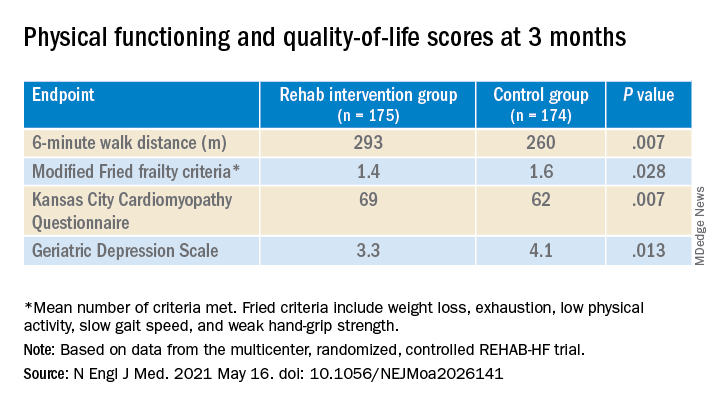

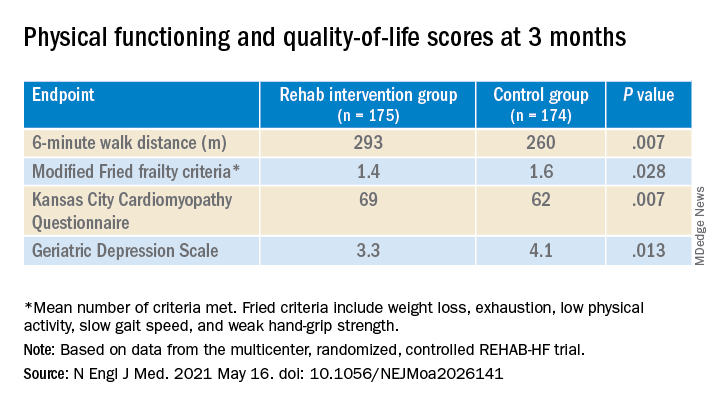

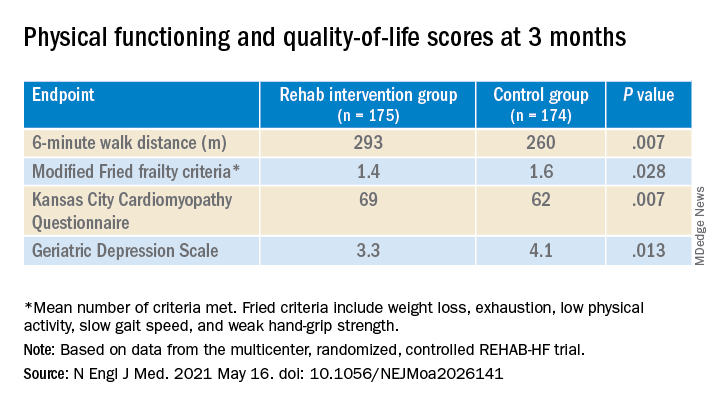

They also showed consistent gains in other measures of physical functioning and quality of life by 12 weeks months.

The observed SPPB treatment effect is “impressive” and “compares very favorably with previously reported estimates,” observed an accompanying editorial from Stefan D. Anker, MD, PhD, of the German Center for Cardiovascular Research and Charité Universitätsmedizin, Berlin, and Andrew J.S. Coats, DM, of the University of Warwick, Coventry, England.

“Similarly, the between-group differences seen in 6-minute walk distance (34 m) and gait speed (0.12 m/s) are clinically meaningful and sizable.”

They propose that some of the substantial quality-of-life benefit in the intervention group “may be due to better physical performance, and that part may be due to improvements in psychosocial factors and mood. It appears that exercise also resulted in patients becoming happier, or at least less depressed, as evidenced by the positive results on the Geriatric Depression Scale.”

Similar results across most subgroups

In subgroup analyses, the intervention was successful against the standard-care approach in both men and women at all ages and regardless of ejection fraction; symptom status; and whether the patient had diabetes, ischemic heart disease, or atrial fibrillation, or was obese.

Clinical outcomes were not significantly different at 6 months. The rate of death from any cause was 13% for the intervention group and 10% for the control group. There were 194 and 213 hospitalizations from any cause, respectively.

Not included in the trial’s current publication but soon to be published, Dr. Kitzman said when interviewed, is a comparison of outcomes in patients with HFpEF and HFrEF. “We found at baseline that those with HFpEF had worse impairment in physical function, quality of life, and frailty. After the intervention, there appeared to be consistently larger improvements in all outcomes, including SPPB, 6-minute walk, qualify of life, and frailty, in HFpEF versus HFrEF.”

The signals of potential benefit in HFpEF extended to clinical endpoints, he said. In contrast to similar rates of all-cause rehospitalization in HFrEF, “in patients with HFpEF, rehospitalizations were 17% lower in the intervention group, compared to the control group.” Still, he noted, the interaction P value wasn’t significant.

However, Dr. Kitzman added, mortality in the intervention group, compared with the control group, was reduced by 35% among patients with HFpEF, “but was 250% higher in HFrEF,” with a significant interaction P value.

He was careful to note that, as a phase 2 trial, REHAB-HF was underpowered for clinical events, “and even the results in the HFpEF group should not be seen as adequate evidence to change clinical care.” They were from an exploratory analysis that included relatively few events.

“Because definitive demonstration of improvement in clinical events is critical for altering clinical care guidelines and for third-party payer reimbursement decisions, we believe that a subsequent phase 3 trial is needed and are currently planning toward that,” Dr. Kitzman said.

The study was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Kermit Glenn Phillips II Chair in Cardiovascular Medicine, and the Oristano Family Fund at Wake Forest. Dr. Kitzman disclosed receiving consulting fees or honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bayer Healthcare, Boehringer Ingelheim, CinRx, Corviamedical, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck; and having an unspecified relationship with Gilead. Dr. Handberg disclosed receiving grants from Aastom Biosciences, Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Amorcyte, AstraZeneca, Biocardia, Boehringer Ingelheim, Capricor, Cytori Therapeutics, Department of Defense, Direct Flow Medical, Everyfit, Gilead, Ionis, Medtronic, Merck, Mesoblast, Relypsa, and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Bittner discloses receiving consulting fees or honoraria from Pfizer and Sanofi; receiving research grants from Amgen and The Medicines Company; and having unspecified relationships with AstraZeneca, DalCor, Esperion, and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Anker reported receiving grants and personal fees from Abbott Vascular and Vifor; personal fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Servier, Cardiac Dimensions, Thermo Fisher Scientific, AstraZeneca, Occlutech, Actimed, and Respicardia. Dr. Coats disclosed receiving personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Menarini, Novartis, Nutricia, Servier, Vifor, Abbott, Actimed, Arena, Cardiac Dimensions, Corvia, CVRx, Enopace, ESN Cleer, Faraday, WL Gore, Impulse Dynamics, and Respicardia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A novel physical rehabilitation program for patients with advanced heart failure that aimed to improve their ability to exercise before focusing on endurance was successful in a randomized trial in ways that seem to have eluded some earlier exercise-training studies in the setting of HF.

The often-frail patients following the training regimen, initiated before discharge from hospitalization for acute decompensation, worked on capabilities such as mobility, balance, and strength deemed necessary if exercises meant to build exercise capacity were to succeed.

A huge percentage stayed with the 12-week program, which featured personalized, one-on-one training from a physical therapist. The patients benefited, with improvements in balance, walking ability, and strength, which were followed by significant gains in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and measures of physical functioning, frailty, and quality of life. The patients then continued elements of the program at home out to 6 months.

At that time, death and rehospitalizations did not differ between those assigned to the regimen and similar patients who had not participated in the program, although the trial wasn’t powered for clinical events.

The rehab strategy seemed to work across a wide range of patient subgroups. In particular, there was evidence that the benefits were more pronounced in patients with HF and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) than in those with HF and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), observed Dalane W. Kitzman, MD, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Dr. Kitzman presented results from the REHAB-HF (Rehabilitation Therapy in Older Acute Heart Failure Patients) trial at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and is lead author on its same-day publication in the New England Journal of Medicine.

An earlier pilot program unexpectedly showed that such patients recently hospitalized with HF “have significant impairments in mobility and balance,” he explained. If so, “it would be hazardous to subject them to traditional endurance training, such as walking-based treadmill or even bicycle.”

The unusual program, said Dr. Kitzman, looks to those issues before engaging the patients in endurance exercise by addressing mobility, balance, and basic strength – enough to repeatedly stand up from a sitting position, for example. “If you’re not able to stand with confidence, then you’re not able to walk on a treadmill.”

This model of exercise rehab “is used in geriatrics research, and enables them to safely increase endurance. It’s well known from geriatric studies that if you go directly to endurance in these, frail, older patients, you have little improvement and often have injuries and falls,” he added.

Guidance from telemedicine?

The functional outcomes examined in REHAB-HF “are the ones that matter to patients the most,” observed Eileen M. Handberg, PhD, of Shands Hospital at the University of Florida, Gainesville, at a presentation on the trial for the media.

“This is about being able to get out of a chair without assistance, not falling, walking farther, and feeling better as opposed to the more traditional outcome measure that has been used in cardiac rehab trials, which has been the exercise treadmill test – which most patients don’t have the capacity to do very well anyway,” said Dr. Handberg, who is not a part of REHAB-HF.

“This opens up rehab, potentially, to the more sick, who also need a better quality of life,” she said.

However, many patients invited to participate in the trial could not because they lived too far from the program, Dr. Handberg observed. “It would be nice to see if the lessons from COVID-19 might apply to this population” by making participation possible remotely, “perhaps using family members as rehab assistance,” she said.

“I was really very impressed that you had 83% adherence to a home exercise 6 months down the road, which far eclipses what we had in HF-ACTION,” said Vera Bittner, MD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, as the invited discussant following Dr. Kitzman’s formal presentation of the trial. “And it certainly eclipses what we see in the typical cardiac rehab program.”

Both Dr. Bittner and Dr. Kitzman participated in HF-ACTION, a randomized exercise-training trial for patients with chronic, stable HFrEF who were all-around less sick than those in REHAB-HF.

Four functional domains

Historically, HF exercise or rehab trials have excluded patients hospitalized with acute decompensation, and third-party reimbursement often has not covered such programs because of a lack of supporting evidence and a supposed potential for harm, Dr. Kitzman said.

Entry to REHAB-HF required the patients to be fit enough to walk 4 meters, with or without a walker or other assistant device, and to have been in the hospital for at least 24 hours with a primary diagnosis of acute decompensated HF.

The intervention relied on exercises aimed at improving the four functional domains of strength, balance, mobility, and – when those three were sufficiently developed – endurance, Dr. Kitzman and associates wrote in their published report.

“The intervention was initiated in the hospital when feasible and was subsequently transitioned to an outpatient facility as soon as possible after discharge,” they wrote. Afterward, “a key goal of the intervention during the first 3 months [the outpatient phase] was to prepare the patient to transition to the independent maintenance phase (months 4-6).”

The study’s control patients “received frequent calls from study staff to try to approximate the increased attention received by the intervention group,” Dr. Kitzman said in an interview. “They were allowed to receive all usual care as ordered by their treating physicians. This included, if ordered, standard physical therapy or cardiac rehabilitation” in 43% of the control cohort. Of the trial’s 349 patients, those assigned to the intervention scored significantly higher on the three-component Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) at 12 weeks than those assigned to a usual care approach that included, for some, more conventional cardiac rehabilitation (8.3 vs. 6.9; P < .001).

The SPPB, validated in trials as a proxy for clinical outcomes includes tests of balance while standing, gait speed during a 4-minute walk, and strength. The latter is the test that measures time needed to rise from a chair five times.

They also showed consistent gains in other measures of physical functioning and quality of life by 12 weeks months.

The observed SPPB treatment effect is “impressive” and “compares very favorably with previously reported estimates,” observed an accompanying editorial from Stefan D. Anker, MD, PhD, of the German Center for Cardiovascular Research and Charité Universitätsmedizin, Berlin, and Andrew J.S. Coats, DM, of the University of Warwick, Coventry, England.

“Similarly, the between-group differences seen in 6-minute walk distance (34 m) and gait speed (0.12 m/s) are clinically meaningful and sizable.”

They propose that some of the substantial quality-of-life benefit in the intervention group “may be due to better physical performance, and that part may be due to improvements in psychosocial factors and mood. It appears that exercise also resulted in patients becoming happier, or at least less depressed, as evidenced by the positive results on the Geriatric Depression Scale.”

Similar results across most subgroups

In subgroup analyses, the intervention was successful against the standard-care approach in both men and women at all ages and regardless of ejection fraction; symptom status; and whether the patient had diabetes, ischemic heart disease, or atrial fibrillation, or was obese.

Clinical outcomes were not significantly different at 6 months. The rate of death from any cause was 13% for the intervention group and 10% for the control group. There were 194 and 213 hospitalizations from any cause, respectively.

Not included in the trial’s current publication but soon to be published, Dr. Kitzman said when interviewed, is a comparison of outcomes in patients with HFpEF and HFrEF. “We found at baseline that those with HFpEF had worse impairment in physical function, quality of life, and frailty. After the intervention, there appeared to be consistently larger improvements in all outcomes, including SPPB, 6-minute walk, qualify of life, and frailty, in HFpEF versus HFrEF.”

The signals of potential benefit in HFpEF extended to clinical endpoints, he said. In contrast to similar rates of all-cause rehospitalization in HFrEF, “in patients with HFpEF, rehospitalizations were 17% lower in the intervention group, compared to the control group.” Still, he noted, the interaction P value wasn’t significant.

However, Dr. Kitzman added, mortality in the intervention group, compared with the control group, was reduced by 35% among patients with HFpEF, “but was 250% higher in HFrEF,” with a significant interaction P value.

He was careful to note that, as a phase 2 trial, REHAB-HF was underpowered for clinical events, “and even the results in the HFpEF group should not be seen as adequate evidence to change clinical care.” They were from an exploratory analysis that included relatively few events.

“Because definitive demonstration of improvement in clinical events is critical for altering clinical care guidelines and for third-party payer reimbursement decisions, we believe that a subsequent phase 3 trial is needed and are currently planning toward that,” Dr. Kitzman said.

The study was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Kermit Glenn Phillips II Chair in Cardiovascular Medicine, and the Oristano Family Fund at Wake Forest. Dr. Kitzman disclosed receiving consulting fees or honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bayer Healthcare, Boehringer Ingelheim, CinRx, Corviamedical, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck; and having an unspecified relationship with Gilead. Dr. Handberg disclosed receiving grants from Aastom Biosciences, Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Amorcyte, AstraZeneca, Biocardia, Boehringer Ingelheim, Capricor, Cytori Therapeutics, Department of Defense, Direct Flow Medical, Everyfit, Gilead, Ionis, Medtronic, Merck, Mesoblast, Relypsa, and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Bittner discloses receiving consulting fees or honoraria from Pfizer and Sanofi; receiving research grants from Amgen and The Medicines Company; and having unspecified relationships with AstraZeneca, DalCor, Esperion, and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Anker reported receiving grants and personal fees from Abbott Vascular and Vifor; personal fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Servier, Cardiac Dimensions, Thermo Fisher Scientific, AstraZeneca, Occlutech, Actimed, and Respicardia. Dr. Coats disclosed receiving personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Menarini, Novartis, Nutricia, Servier, Vifor, Abbott, Actimed, Arena, Cardiac Dimensions, Corvia, CVRx, Enopace, ESN Cleer, Faraday, WL Gore, Impulse Dynamics, and Respicardia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A novel physical rehabilitation program for patients with advanced heart failure that aimed to improve their ability to exercise before focusing on endurance was successful in a randomized trial in ways that seem to have eluded some earlier exercise-training studies in the setting of HF.

The often-frail patients following the training regimen, initiated before discharge from hospitalization for acute decompensation, worked on capabilities such as mobility, balance, and strength deemed necessary if exercises meant to build exercise capacity were to succeed.

A huge percentage stayed with the 12-week program, which featured personalized, one-on-one training from a physical therapist. The patients benefited, with improvements in balance, walking ability, and strength, which were followed by significant gains in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and measures of physical functioning, frailty, and quality of life. The patients then continued elements of the program at home out to 6 months.

At that time, death and rehospitalizations did not differ between those assigned to the regimen and similar patients who had not participated in the program, although the trial wasn’t powered for clinical events.

The rehab strategy seemed to work across a wide range of patient subgroups. In particular, there was evidence that the benefits were more pronounced in patients with HF and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) than in those with HF and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), observed Dalane W. Kitzman, MD, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Dr. Kitzman presented results from the REHAB-HF (Rehabilitation Therapy in Older Acute Heart Failure Patients) trial at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and is lead author on its same-day publication in the New England Journal of Medicine.

An earlier pilot program unexpectedly showed that such patients recently hospitalized with HF “have significant impairments in mobility and balance,” he explained. If so, “it would be hazardous to subject them to traditional endurance training, such as walking-based treadmill or even bicycle.”

The unusual program, said Dr. Kitzman, looks to those issues before engaging the patients in endurance exercise by addressing mobility, balance, and basic strength – enough to repeatedly stand up from a sitting position, for example. “If you’re not able to stand with confidence, then you’re not able to walk on a treadmill.”

This model of exercise rehab “is used in geriatrics research, and enables them to safely increase endurance. It’s well known from geriatric studies that if you go directly to endurance in these, frail, older patients, you have little improvement and often have injuries and falls,” he added.

Guidance from telemedicine?

The functional outcomes examined in REHAB-HF “are the ones that matter to patients the most,” observed Eileen M. Handberg, PhD, of Shands Hospital at the University of Florida, Gainesville, at a presentation on the trial for the media.

“This is about being able to get out of a chair without assistance, not falling, walking farther, and feeling better as opposed to the more traditional outcome measure that has been used in cardiac rehab trials, which has been the exercise treadmill test – which most patients don’t have the capacity to do very well anyway,” said Dr. Handberg, who is not a part of REHAB-HF.

“This opens up rehab, potentially, to the more sick, who also need a better quality of life,” she said.

However, many patients invited to participate in the trial could not because they lived too far from the program, Dr. Handberg observed. “It would be nice to see if the lessons from COVID-19 might apply to this population” by making participation possible remotely, “perhaps using family members as rehab assistance,” she said.

“I was really very impressed that you had 83% adherence to a home exercise 6 months down the road, which far eclipses what we had in HF-ACTION,” said Vera Bittner, MD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, as the invited discussant following Dr. Kitzman’s formal presentation of the trial. “And it certainly eclipses what we see in the typical cardiac rehab program.”

Both Dr. Bittner and Dr. Kitzman participated in HF-ACTION, a randomized exercise-training trial for patients with chronic, stable HFrEF who were all-around less sick than those in REHAB-HF.

Four functional domains

Historically, HF exercise or rehab trials have excluded patients hospitalized with acute decompensation, and third-party reimbursement often has not covered such programs because of a lack of supporting evidence and a supposed potential for harm, Dr. Kitzman said.

Entry to REHAB-HF required the patients to be fit enough to walk 4 meters, with or without a walker or other assistant device, and to have been in the hospital for at least 24 hours with a primary diagnosis of acute decompensated HF.

The intervention relied on exercises aimed at improving the four functional domains of strength, balance, mobility, and – when those three were sufficiently developed – endurance, Dr. Kitzman and associates wrote in their published report.

“The intervention was initiated in the hospital when feasible and was subsequently transitioned to an outpatient facility as soon as possible after discharge,” they wrote. Afterward, “a key goal of the intervention during the first 3 months [the outpatient phase] was to prepare the patient to transition to the independent maintenance phase (months 4-6).”

The study’s control patients “received frequent calls from study staff to try to approximate the increased attention received by the intervention group,” Dr. Kitzman said in an interview. “They were allowed to receive all usual care as ordered by their treating physicians. This included, if ordered, standard physical therapy or cardiac rehabilitation” in 43% of the control cohort. Of the trial’s 349 patients, those assigned to the intervention scored significantly higher on the three-component Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) at 12 weeks than those assigned to a usual care approach that included, for some, more conventional cardiac rehabilitation (8.3 vs. 6.9; P < .001).

The SPPB, validated in trials as a proxy for clinical outcomes includes tests of balance while standing, gait speed during a 4-minute walk, and strength. The latter is the test that measures time needed to rise from a chair five times.

They also showed consistent gains in other measures of physical functioning and quality of life by 12 weeks months.

The observed SPPB treatment effect is “impressive” and “compares very favorably with previously reported estimates,” observed an accompanying editorial from Stefan D. Anker, MD, PhD, of the German Center for Cardiovascular Research and Charité Universitätsmedizin, Berlin, and Andrew J.S. Coats, DM, of the University of Warwick, Coventry, England.

“Similarly, the between-group differences seen in 6-minute walk distance (34 m) and gait speed (0.12 m/s) are clinically meaningful and sizable.”

They propose that some of the substantial quality-of-life benefit in the intervention group “may be due to better physical performance, and that part may be due to improvements in psychosocial factors and mood. It appears that exercise also resulted in patients becoming happier, or at least less depressed, as evidenced by the positive results on the Geriatric Depression Scale.”

Similar results across most subgroups

In subgroup analyses, the intervention was successful against the standard-care approach in both men and women at all ages and regardless of ejection fraction; symptom status; and whether the patient had diabetes, ischemic heart disease, or atrial fibrillation, or was obese.

Clinical outcomes were not significantly different at 6 months. The rate of death from any cause was 13% for the intervention group and 10% for the control group. There were 194 and 213 hospitalizations from any cause, respectively.

Not included in the trial’s current publication but soon to be published, Dr. Kitzman said when interviewed, is a comparison of outcomes in patients with HFpEF and HFrEF. “We found at baseline that those with HFpEF had worse impairment in physical function, quality of life, and frailty. After the intervention, there appeared to be consistently larger improvements in all outcomes, including SPPB, 6-minute walk, qualify of life, and frailty, in HFpEF versus HFrEF.”

The signals of potential benefit in HFpEF extended to clinical endpoints, he said. In contrast to similar rates of all-cause rehospitalization in HFrEF, “in patients with HFpEF, rehospitalizations were 17% lower in the intervention group, compared to the control group.” Still, he noted, the interaction P value wasn’t significant.

However, Dr. Kitzman added, mortality in the intervention group, compared with the control group, was reduced by 35% among patients with HFpEF, “but was 250% higher in HFrEF,” with a significant interaction P value.

He was careful to note that, as a phase 2 trial, REHAB-HF was underpowered for clinical events, “and even the results in the HFpEF group should not be seen as adequate evidence to change clinical care.” They were from an exploratory analysis that included relatively few events.

“Because definitive demonstration of improvement in clinical events is critical for altering clinical care guidelines and for third-party payer reimbursement decisions, we believe that a subsequent phase 3 trial is needed and are currently planning toward that,” Dr. Kitzman said.

The study was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Kermit Glenn Phillips II Chair in Cardiovascular Medicine, and the Oristano Family Fund at Wake Forest. Dr. Kitzman disclosed receiving consulting fees or honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bayer Healthcare, Boehringer Ingelheim, CinRx, Corviamedical, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck; and having an unspecified relationship with Gilead. Dr. Handberg disclosed receiving grants from Aastom Biosciences, Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Amorcyte, AstraZeneca, Biocardia, Boehringer Ingelheim, Capricor, Cytori Therapeutics, Department of Defense, Direct Flow Medical, Everyfit, Gilead, Ionis, Medtronic, Merck, Mesoblast, Relypsa, and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Bittner discloses receiving consulting fees or honoraria from Pfizer and Sanofi; receiving research grants from Amgen and The Medicines Company; and having unspecified relationships with AstraZeneca, DalCor, Esperion, and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Anker reported receiving grants and personal fees from Abbott Vascular and Vifor; personal fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Servier, Cardiac Dimensions, Thermo Fisher Scientific, AstraZeneca, Occlutech, Actimed, and Respicardia. Dr. Coats disclosed receiving personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Menarini, Novartis, Nutricia, Servier, Vifor, Abbott, Actimed, Arena, Cardiac Dimensions, Corvia, CVRx, Enopace, ESN Cleer, Faraday, WL Gore, Impulse Dynamics, and Respicardia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.